On 3 January 1959, Mr. P’u Ju (溥儒) gave the 3rd Hong Kong Lecture at the University of Hong Kong, titled Calligraphy and Painting Share Common Origins. The contents of this lecture are extensions of the 1st Lecture: Chinese Literature, Calligraphy and Painting delivered on 22 December 1958; and the 2nd Lecture: Calligraphy and Painting delivered on 2 January 1959. However the 3rd Lecture further expounded the use of brush. Although there are only three speeches, the values and viewpoints of Mr. P’u are worthwhile inspirations for posterity.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

On 3 January in the 48th year of the Republic of China (1959), Mr. P’u Ju (溥儒) delivered the 3rd Hong Kong lecture in the Chemistry Building auditorium at the University of Hong Kong. The title of the lecture is: On the Common Origin of Calligraphy and Painting. The complete text of the speech was published in Wah Kiu Yat Po Newspaper (華僑日報) in eight separate installments on 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19 January 1959. The text reads:

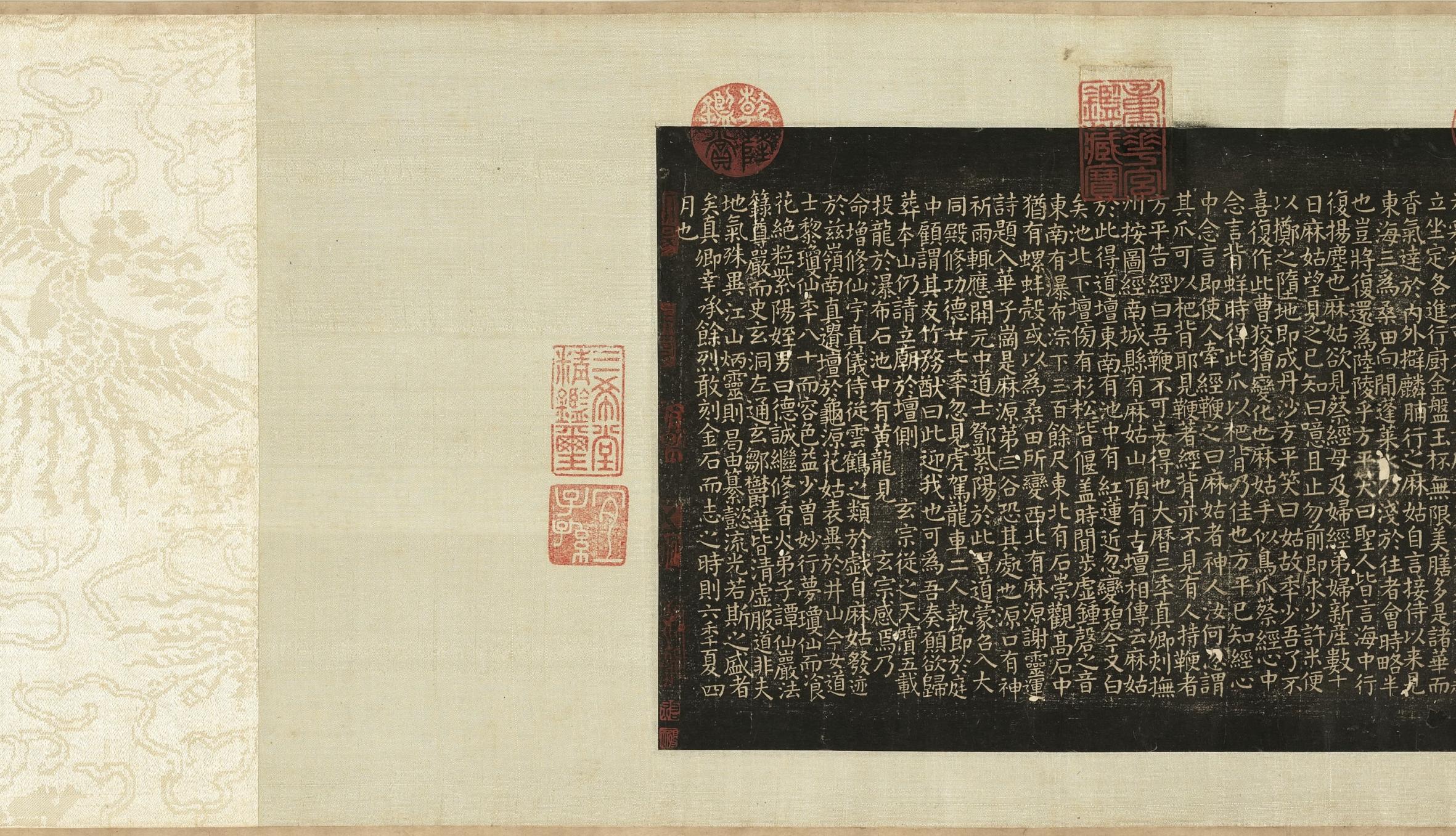

Lecture text installment of On the Common Origin of Calligraphy and Painting by Mr. P’u Ju published in Wah Kiu Yat Po Newspaper in Hong Kong on 12 January 1959

Lecture text installment of On the Common Origin of Calligraphy and Painting by Mr. P’u Ju published in Wah Kiu Yat Po Newspaper in Hong Kong on 12 January 1959.

Lecture text installment of On the Common Origin of Calligraphy and Painting by Mr. P’u Ju published in Wah Kiu Yat Po Newspaper in Hong Kong on 19 January 1959

“Last time I told you in order to paint, one should start learning propriety, become upright, cultivate integrity; study the Classics, poetry, literature, calligraphy; after which one proceeds to paint. If the priorities are reversed, the painting will certainly be inferior. Painting is an expression of one’s moral character, integrity and demeanor. If the individual lacks merit, how can the painting possess any merit?

As for the boundaries of art, there are slight differences between ancient and modern times. The ancients practiced the Six Arts of rites, music, archery, chariotry, calligraphy and mathematics. Nowadays, when people talk about rites, they refer to specific ceremonies like coming-of-age, wedding, funeral, and those that cater for the elders. Such rites serve to constrain individuals from crossing certain boundaries, they are often stricter than legal rules. Within the realm of art, the disciplines of music, archery, chariotry, calligraphy, and mathematics were considered to be crafts by some ancients, now they are regarded as art. An example is sculpture. Yet for rites, the foremost of the Six Arts, it is no longer regarded as important nowadays. This is so distant from the teachings of ancient sages.

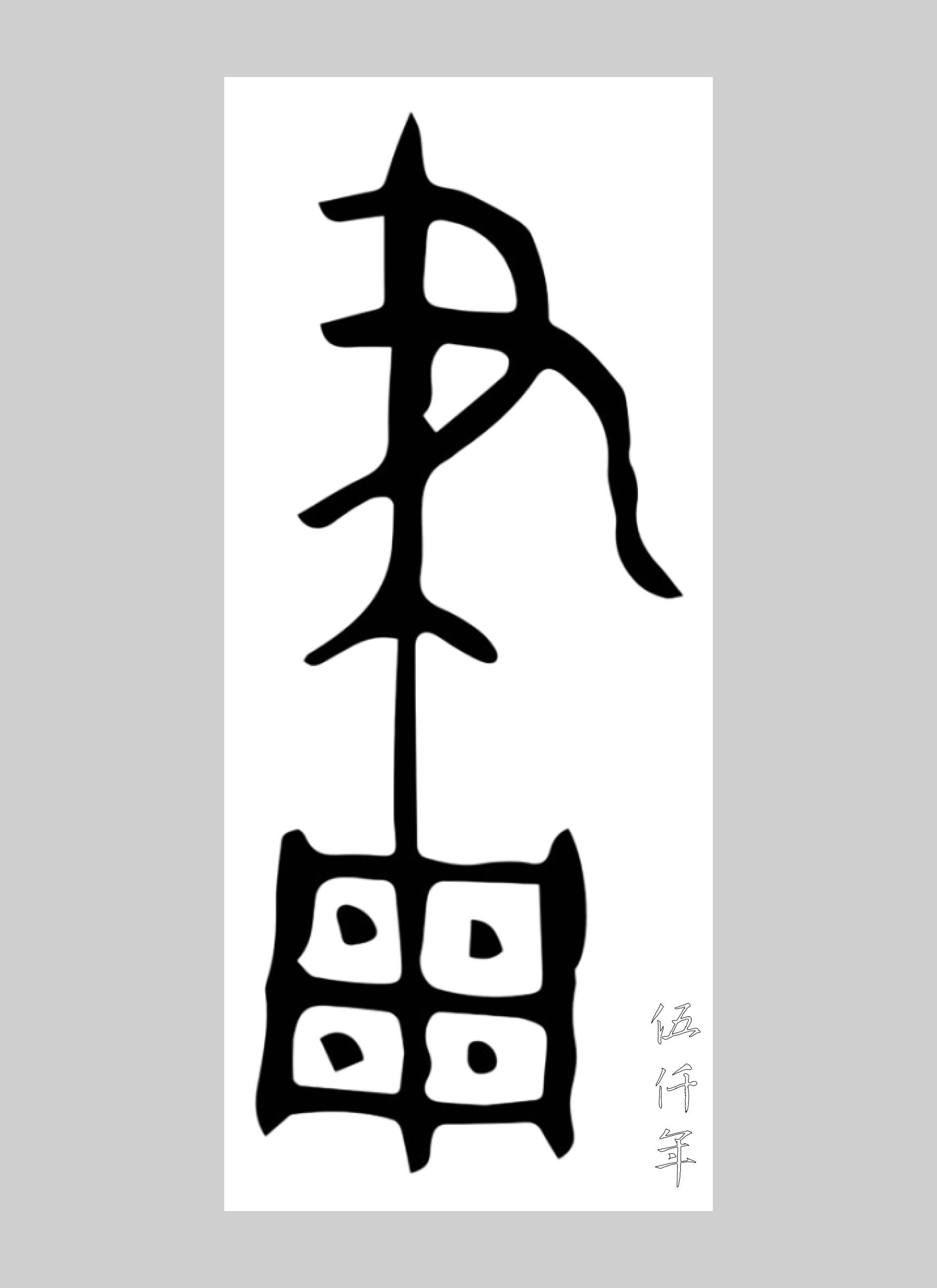

The origin of writing began with pictographs. In truth they are drawings. In Shuo-wen (說文), the character “brush (筆)” looks like a hand holding a brush .

The character “brush” according to oracle bone script

The character “draw or paint (畫)” implies the demarcation of plots of farmland. Since ancient people placed great importance on farmland, demarcating the fields is symbolized by the character of draw or paint.

The character “draw or paint” according to archaic bronze script

The Six Writings (六書 which consists of pictograph 象形, simple ideograph 指事, compound ideograph 會意, phono-semantic compound 形聲, phonetic loan 假借, derivative cognate 轉注) probably start with pictograph. It can be said that in the beginning drawing and writing were inseparable from each other.

Taotie mythical creature depicted on archaic bronze vessel of Shang dynasty. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

Detail of taotie mythical creature depicted on archaic bronze vessel of Shang dynasty. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

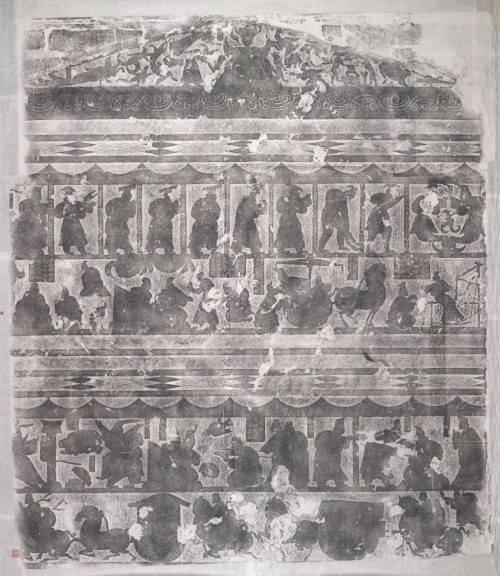

Ink rubbing of relief carvings in Wu Liang Shrine of Han dynasty. Photograph courtesy Academia Sinica

The ancients painted with practical purposes in mind. It was intended to be meaningful. The saying: “Pictures on the left, history books on the right,” suggests that pictures are to coexist with history. The taotie mythical creature on archaic bronze vessels from the Hsia, Shang and Chou dynasties evoke a sense of dietary restraint for those who look at it. The relief carvings in Wu Liang Shrine (武梁祠) of Han dynasty depict stories of virtuous individuals, giving praise to the loyal and the righteous. For example, the story of Confucius meeting Lao-tzu was explicitly portrayed in painting. During the Six Dynasties, there was the Sutra of Measurements (量度經) which chronicled the questions and responses between disciples and Buddha on matters after Nirvana. It also includes measurements of various body parts of Tathagata, such as the head, hands, torso and feet. Later, when people write stories about the images of Buddha, most base their writings on this Sutra. It was only during the High T’ang period that landscape painting became fashionable. Attention was then paid to the different seasons of spring, summer, autumn, winter, and different scenes such as snowing. Painting is no longer undertaken for practical purpose, it is intended to express sentiments.

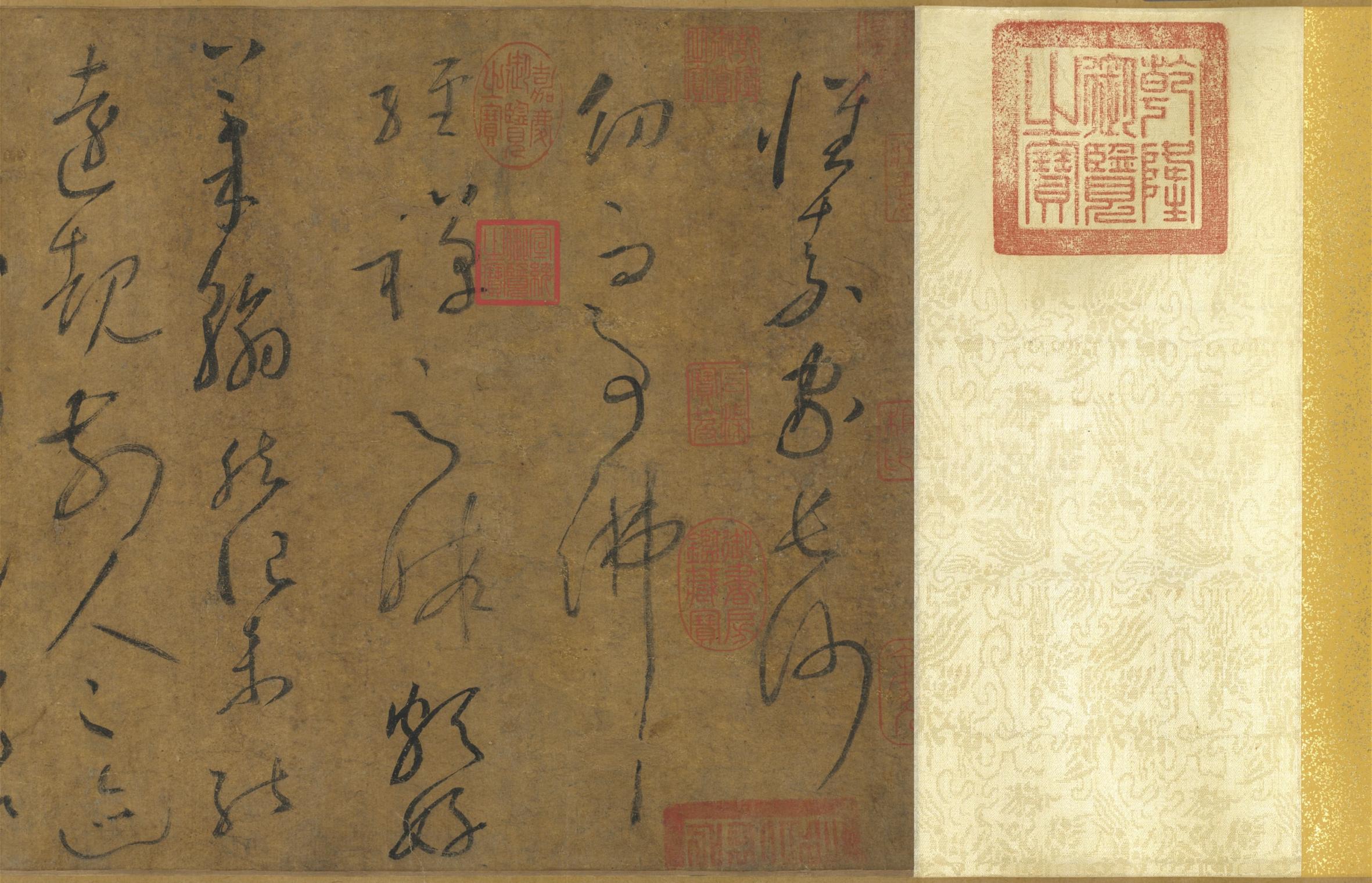

First section of Tz’u-hsü Scroll (Autobiography) by Huai Su from the T’ang dynasty. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

Second section of Tz’u-hsü Scroll (Autobiography) by Huai Su from the T’ang dynasty. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

As for calligraphy, the cursive script of Huai Su (懷素 737-799) from the T’ang dynasty is said to have been inspired by observing the subtle flow and whirling waves of moving clouds, from these he understood brushwork. Shu-p’u (A Narrative on Calligraphy 書譜) says: “Delicate as new moon emerging from distant sky, dispersed as numerous stars in Milky Way.” Is this not painting too?

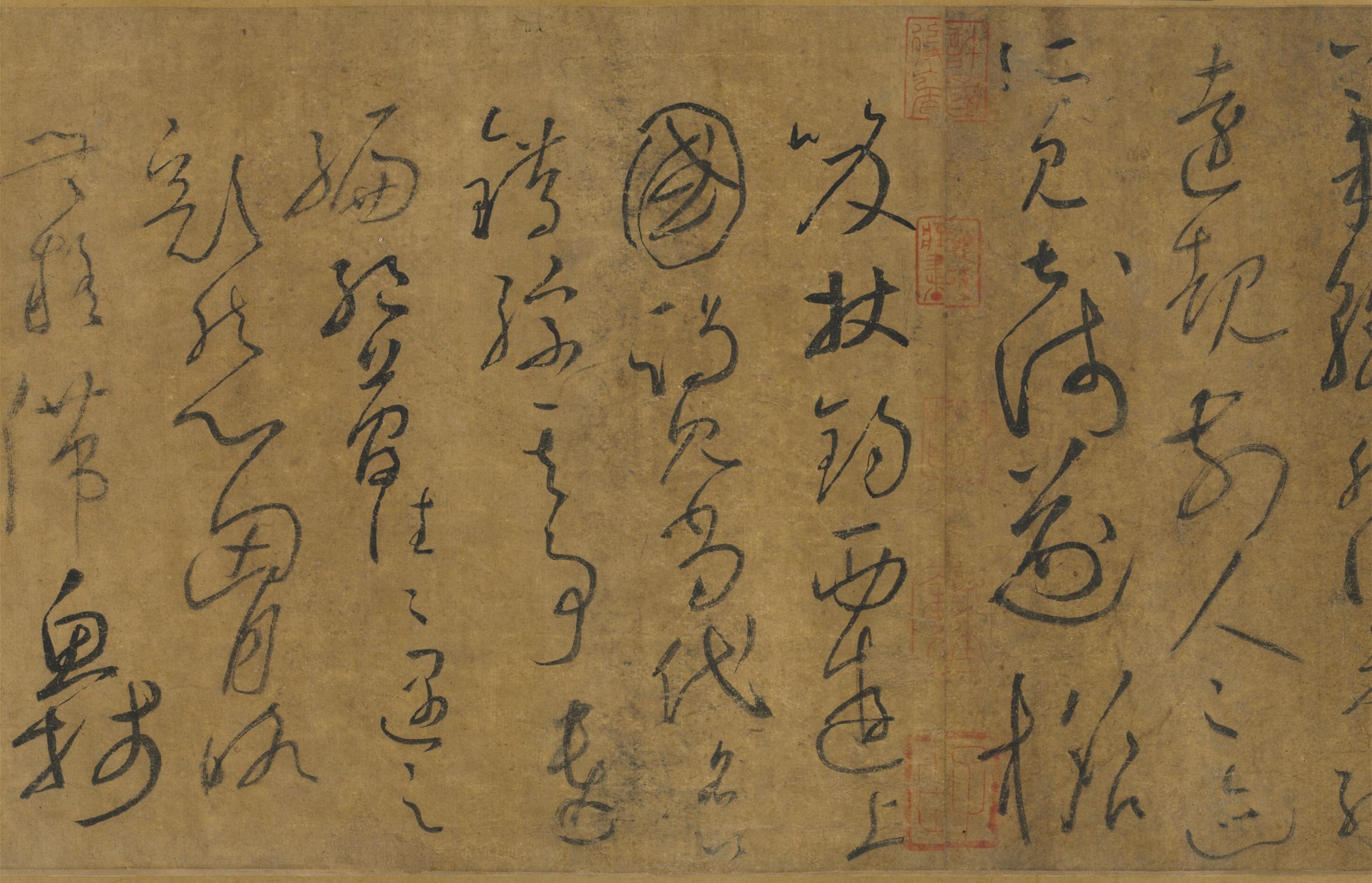

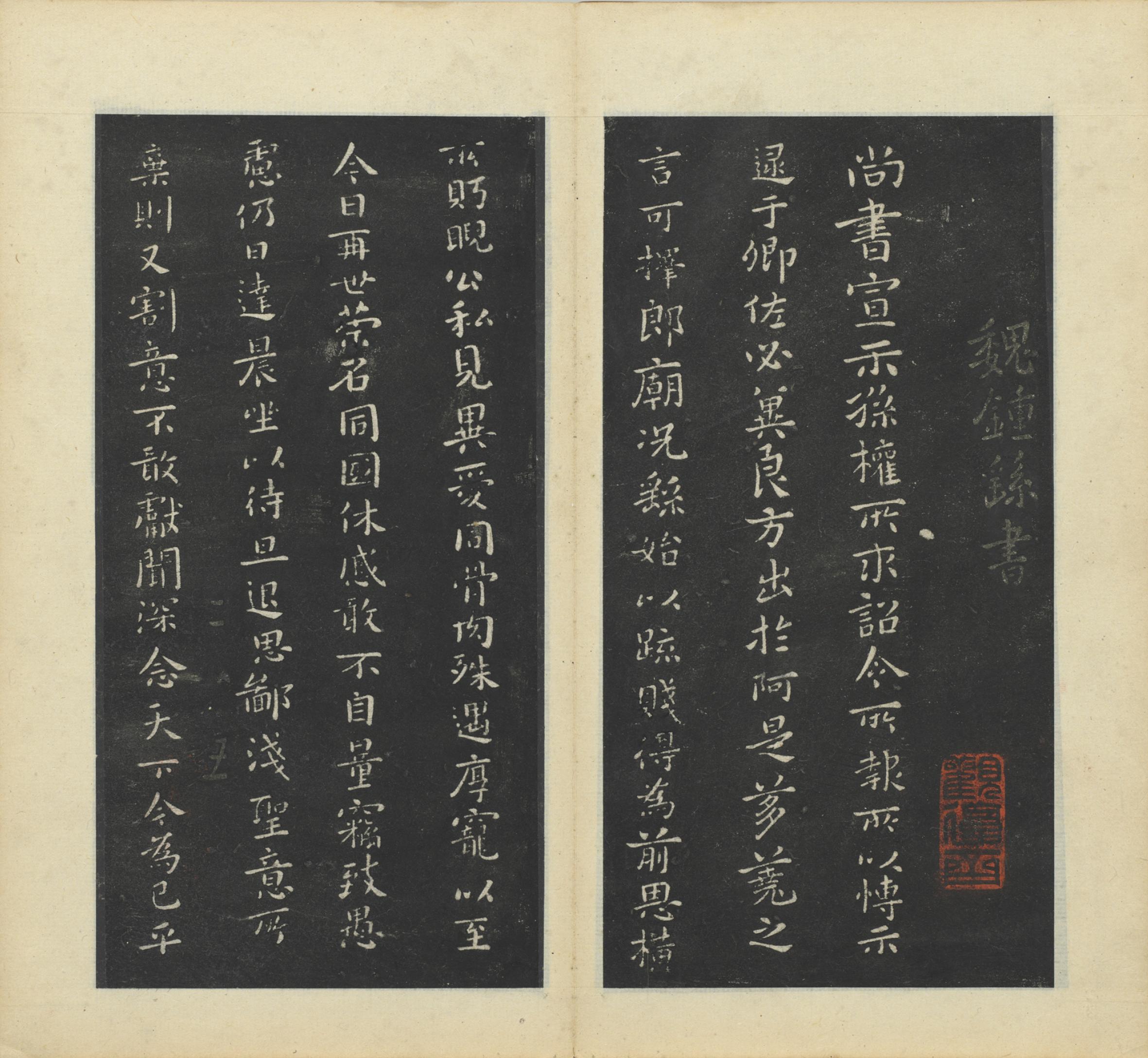

Ink rubbing of Hsüan-shih-piao regular script calligraphy carved on stele by Chung Yao from the Wei dynasty. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

Painting and calligraphy are alike, vigour in brushwork is of key importance. The ancients began calligraphic practice with seal script and clerical script, then they moved on to regular script and cursive script. Chung Yao (鍾繇 151-230) is known for his extraordinary mastery of clerical script, while Wang Hsi-chih (王羲之 303-361) and Wang Hsien-chih (王獻之 344-386) also wrote clerical script, though their works in this genre are no longer extant. It is not that they did not write these scripts, only they have ceased to exist. Writing seal script helps us learn to balance brushstrokes, so that each stroke remains consistent from start to finish. This requires vigour in brushwork. Clerical script trains the skill of ts’ang-feng (藏鋒 concealing brushwork created by brush tip). In clerical script, lifting the brush and dotting the brush require ts’ang-feng (concealing brushwork created by brush tip) and then turning back the brush tip. Clerical script cannot be undertaken without using ts’ang-feng. To describe calligraphy that is archaic, rustic, composed and natural, there is the illustrative phrase: “House leakage marks (to describe natural drips)”, or the expressive terms: “breaking hair clip (to describe uneven edges), drawing sand with awl (to describe subdued lines), stamping seal in paste (also describes subdued lines).” Seal script and clerical script can offer training towards this objective.

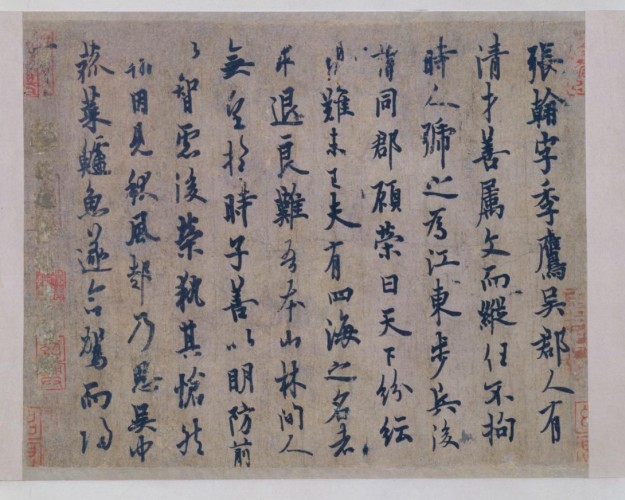

A section of Chang-han Scroll by Ou-yang Hsün from the T’ang dyasty. Photograph courtesy Peking Palace Museum

Someone once used this phrase to describe how to paint well: “All those who are distinguished in calligraphy and painting can revolve their arms naturally.” This is about wielding the brush. Ou-yang Hsün (歐陽詢 557-641) said: “Move the arm while the fingers are oblivious”. This is about the ability to control the brush and to control it effectively. If the brush is not well-controlled, how can one write? Brush can be applied using ts’ai-feng (側鋒 using the side of brush), if one does not understand this, if one cannot apply hsüan-wan (懸腕 suspend the wrist in mid-air while holding the brush), if one does not understand tun (頓 pausing the brush) and ts’o (挫 lifting and turning the brush after pausing), then one is incapable of painting.

Brushwork in calligraphy can display infinite variations even for characters with only a few strokes. Our ancestors described calligraphy as “dragons soaring and tigers leaping”. Such is its agility and dynamic transformation. Painting also emphasizes variations. For instance, when painting bamboo, the stem should be robust and upright, the leaves should be lively, capturing graceful movement in the wind. There should be the presence of both brush and ink. Ink means well-balanced lightness and depth, brush means techniques in usage. Brush and ink are to complement each other. This is achieved through variations in the use of brush.

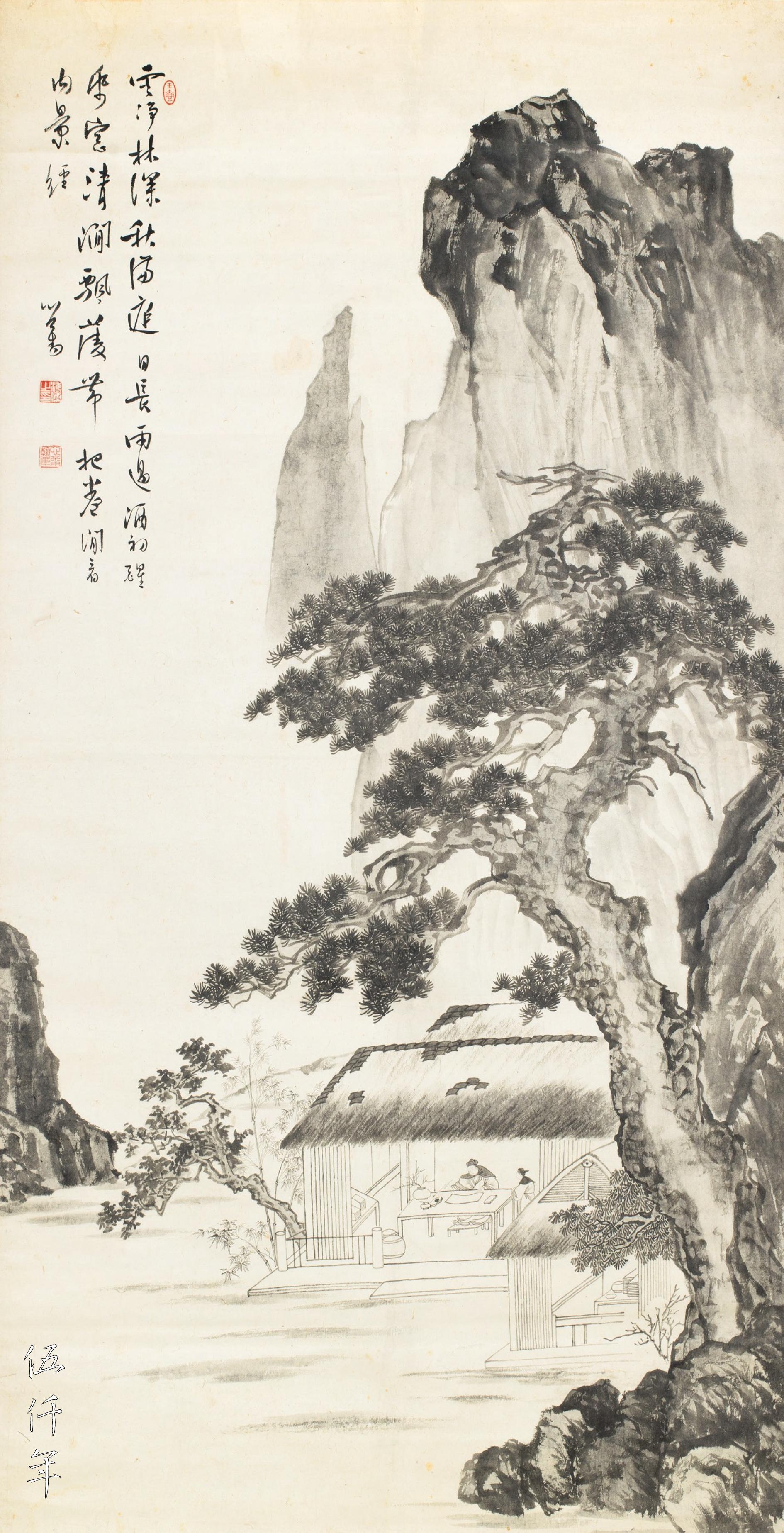

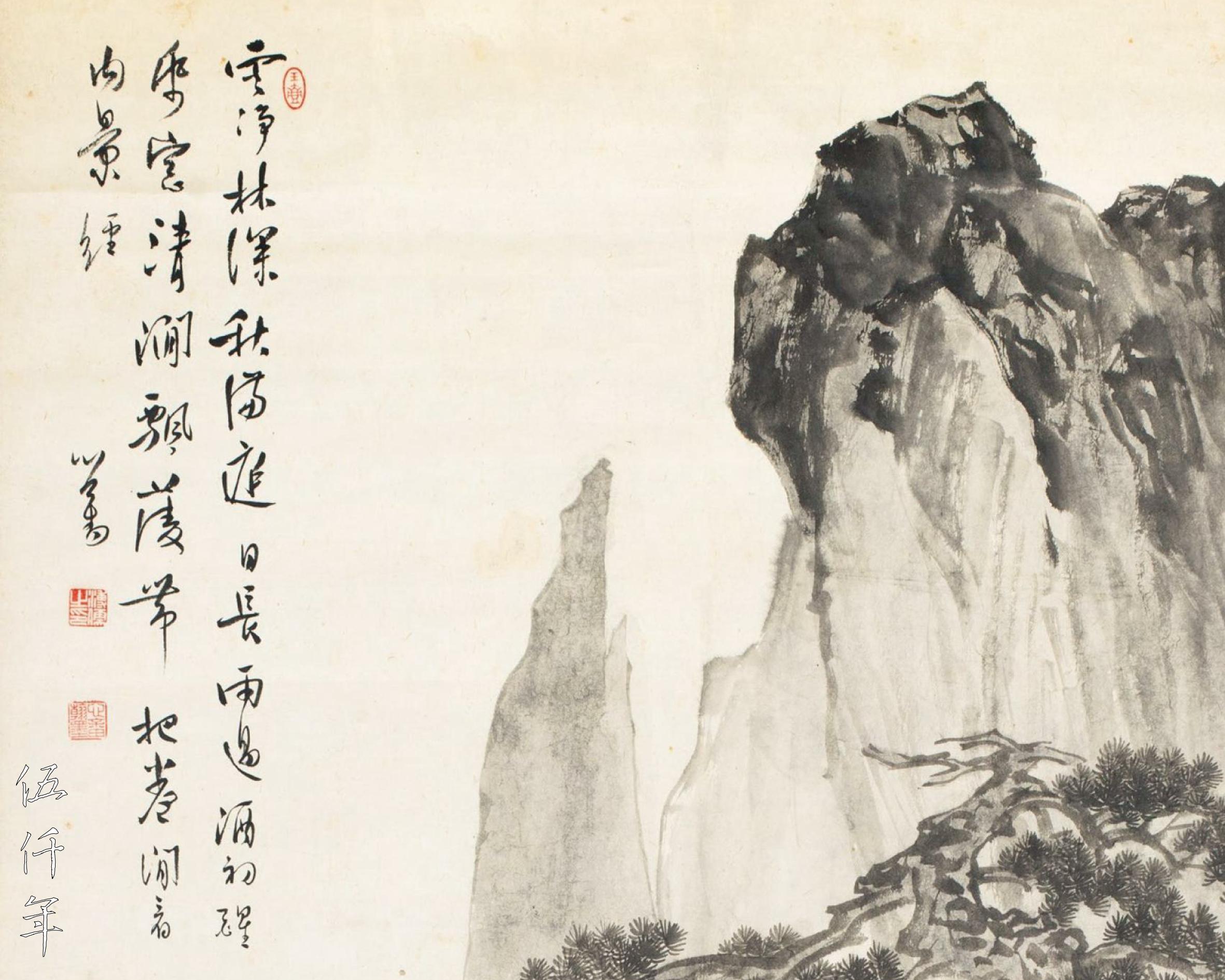

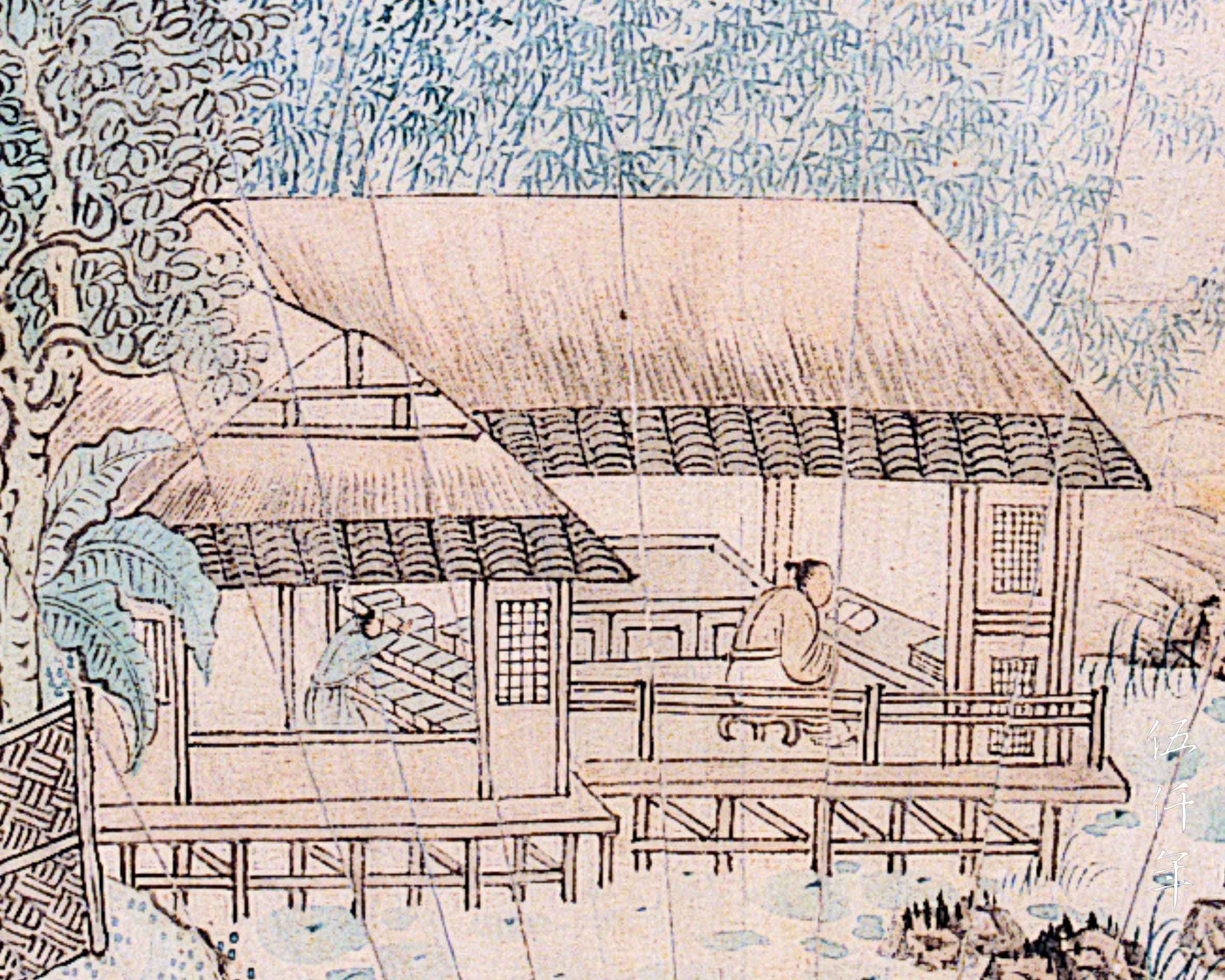

Hanging scroll of Reading the Taoist Text of Huang-t’ing-ching by P’u Ju. Photograph courtesy Private Collection

First detail of Reading the Taoist Text of Huang-t’ing-ching by P’u Ju. Photograph courtesy Private Collection

Second detail of Reading the Taoist Text of Huang-t’ing-ching by P’u Ju. Photograph courtesy Private Collection

Third detail of Reading the Taoist Text of Huang-t’ing-ching by P’u Ju. Photograph courtesy Private Collection

Recalling my own journey of learning to paint, I did not learn from a teacher. In the past, my family had many old masterpieces, spanning all the dynasties from Chin, T’ang, Song to Yüan. I copied these authentic works, studied them, then observed real landscapes and objects. I started to learn painting from the prime of my life. As I did not have a teacher, whenever I had problems and difficulties, they took a long time to resolve. I had to think through them myself and slowly came to my own realizations. At first I did not paint well. I thought to myself why I could not paint well? In the example of painting pine trees, my early attempts were messy. I compared my work with others and those by ancient masters. Then I tried again. After a while, I looked at my own paintings again and found that those in monochrome ink were good, but not those in coloured ink. It should not be the case. Why were those in coloured ink not beautiful? Is it not so that the ancient masters used plenty of coloured ink? Why do their works look beautiful and not mine? So I took out the paintings by ancient masters for comparison and finally understood. It turned out the reason mine were not beautiful was because my colours were either too pale or too heavy. Colours should be gradually applied in layers from light to dark. If dark colour is applied outright, it will not be beautiful. Colour should be evenly applied. How can this be achieved? More water and less colour makes it even, while less water and more colour makes it uneven. They were all learned by trial and error. This is akin to scientific experiments, the underlying principles are slowly discovered. In summary, one must think. Thinking can attain understanding and thinking can prevent the violation of principles. Mencius said: “By thinking, it gets the right view of things; by neglecting to think, it fails to do this.” The Sage also said: “Careful reflection on it, the clear discrimination of it, and the earnest practice of it.” So I often tell students that those who are careless will find it difficult to learn. Being careless means neglecting to think, and neglecting to think means failing to learn. Learning to paint requires thoughtfulness and attention to detail.

Some students of painting asked me: “How can one be thoughtful and pay attention to detail?” I cited one example. When painting landscape, bamboo or prunus, one must immerse oneself in the landscape, bamboo or prunus. One must remain in that environment and not leave. When painting forest in autumn, imagine yourself to be in a forest in autumn. When painting river in spring, imagine enjoying yourself in the midst of streams and mountains in spring. When painting a cold night, imagine yourself feeling shivery. It is similar to acting. If you are acting the role of Chu-ko Liang (諸葛亮 181-234) in opera, you lose yourself and think you are Chu-ko Liang, this is the way to make the performance convincing! Ancient artists created works like Picture of the North Wind (北風圖) where the viewer could feel the chill, and Picture of the Milky Way (雲漢圖) where the viewer could feel the heat. When the painting is well conceived and truthful, it is moving.

Painting of Chang Seng-yao on the horizontal beam in the Summer Palace in Peking

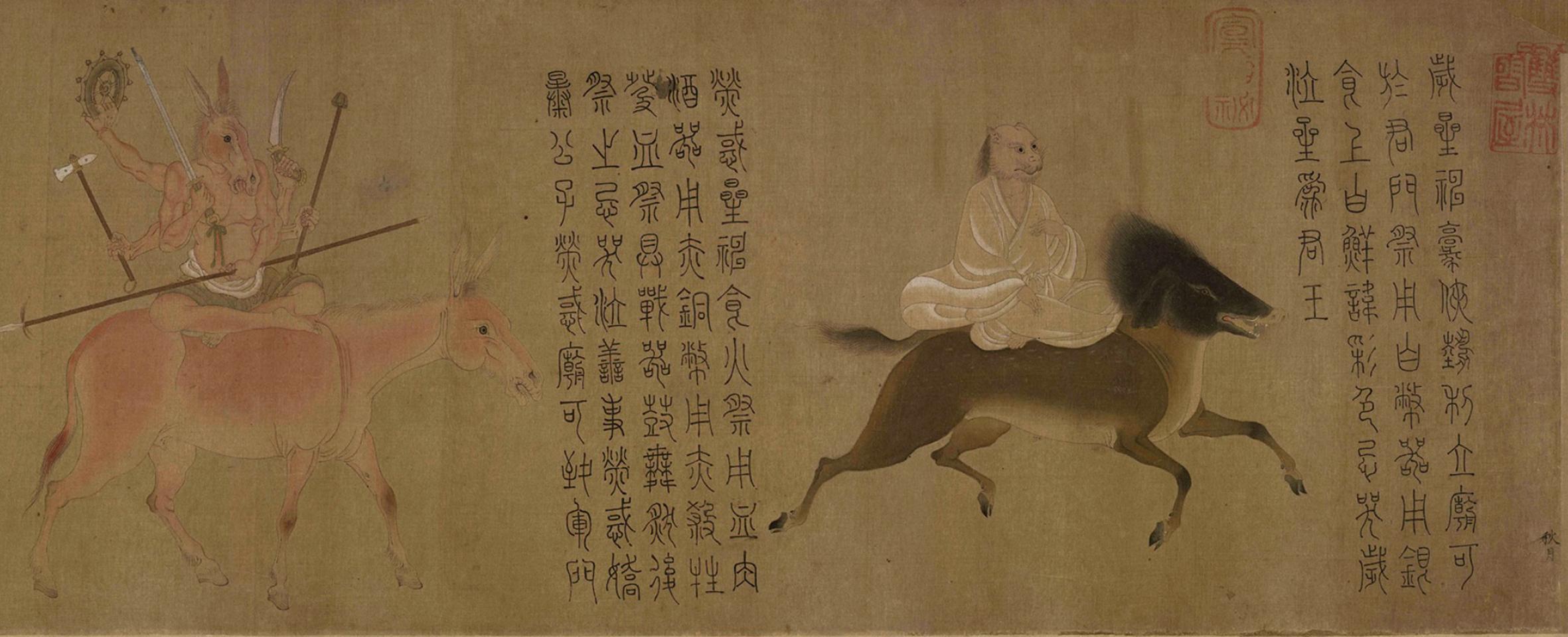

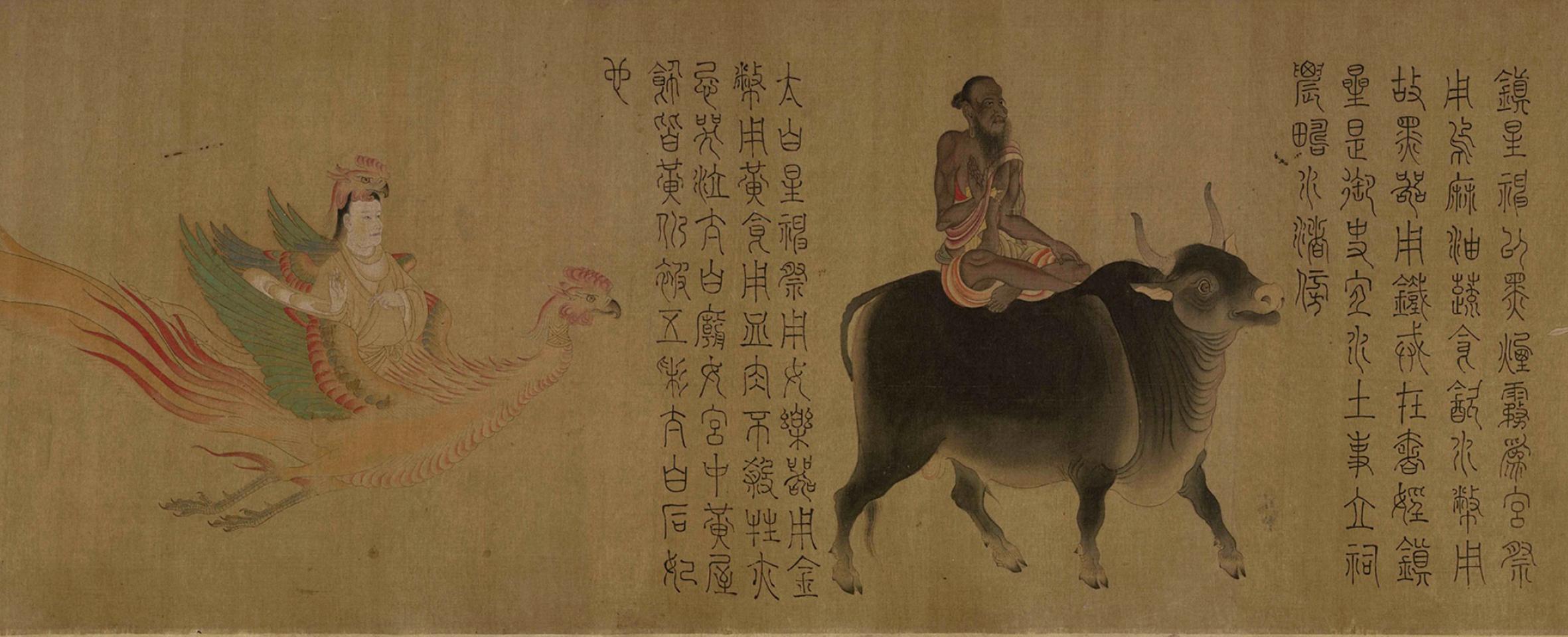

First section of hand scroll by Chang Seng-yao from the Southern dynasty. Photograph courtesy Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Second section of hand scroll by Chang Seng-yao from the Southern dynasty. Photograph courtesy Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

According to art history, Chang Seng-yao (張僧繇 479-?) once painted a crane on temple wall, even real birds stopped going into the temple to deface the wall. This demonstrated that his crane was so realistic even birds were convinced they were real. The ancients always painted real objects and conveyed real forms. They were able to relay realistic portrayals with various brush techniques. These techniques were derived from calligraphy, employing the same principles as the Eight Techniques of Calligraphy.

Portrait of Emperor Hui-tsung from the Sung dynasty. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

Painting of Bird and Pine by Emperor Hui-tsung. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

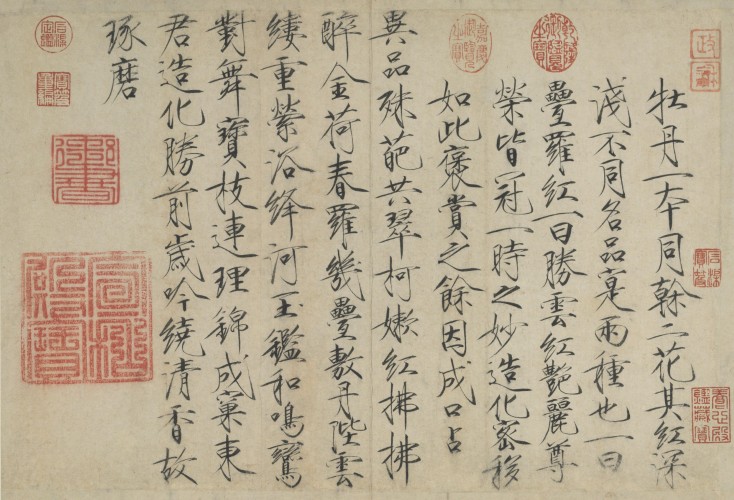

Peony Poem by Emperor Hui-tsung. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

If a work bears resemblance but has no brush technique, it is like a picture by a child. Emperor Hui-tsung (宋徽宗 1082-1135) of the Sung dynasty excelled in painting because his portrayal was realistic. His calligraphy was also exceptional, it was derived from the Foreword of Shih-tsung Poem Stele (石淙詩序碑) by Hsüeh Yao (薛曜 642-704) in the T’ang dynasty. Since Emperor Hui-tsung was brilliant in calligraphy, his brushwork was vigorous, hence he could produce splendid paintings. Many later artists diverged from this principle! Brush technique and realistic portrayal gradually separated from each other into two facets. One facet is realistic portrayal that neglected brush technique, the other facet is brush technique that neglected realistic portrayal. When realistic portrayal is lost, painting becomes more and more illusory. Therefore, brush technique should still be complemented by realistic portrayal.

Portrait of Emperor T’ai-tsung from the T’ang dynasty. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

A Sung dynasty ink rubbing of Chiang-shu Scroll carved on stele by Emperor Hui-tsung. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

Regarding the forms of calligraphy, it is infinite. Each era is different and has its own style. Only the usage of brush remains constant throughout the ages. Lifting (起), landing (伏), pausing (頓), lifting and turning (挫), rotating (轉), squaring (折) are all brush techniques. An analogy of things unchanged are the head, torso and limbs of a human, which remain the same from ancient to modern times. An analogy of things changed are clothing styles, from ancient costumes, to modern Chinese costumes, to western costumes, and there are all kinds of costumes. Brush techniques are like human body, brushwork is like costumes. If attention is on the likeness of costumes and not the likeness of body, how can there be true likeness? Emperor T’ai-tsung (唐太宗 598-649) of the T’ang dynasty said that when learning painting, he only paid attention to brush techniques and not painterly forms. By using the brush correctly, painterly forms will naturally emerge. Otherwise, even though painterly forms are produced, improper use of the brush results in form without structure, which is just as futile.

In the realm of painting, the use of brush refers to the vigour of brushwork which should be strong and firm, yet flexible and graceful. Only then can the subject be brought to life. For example, when painting flowers, brushwork should be dynamic to capture the vibrancy of the dew-laden blossoms. When painting birds, they should resemble birds singing. No matter whether one is painting bird, bamboo nodes, withered grass, they all require brushwork that is strong as iron to achieve good result. Therefore, it is essential to use calligraphic training to cultivate the vigour in brushwork.

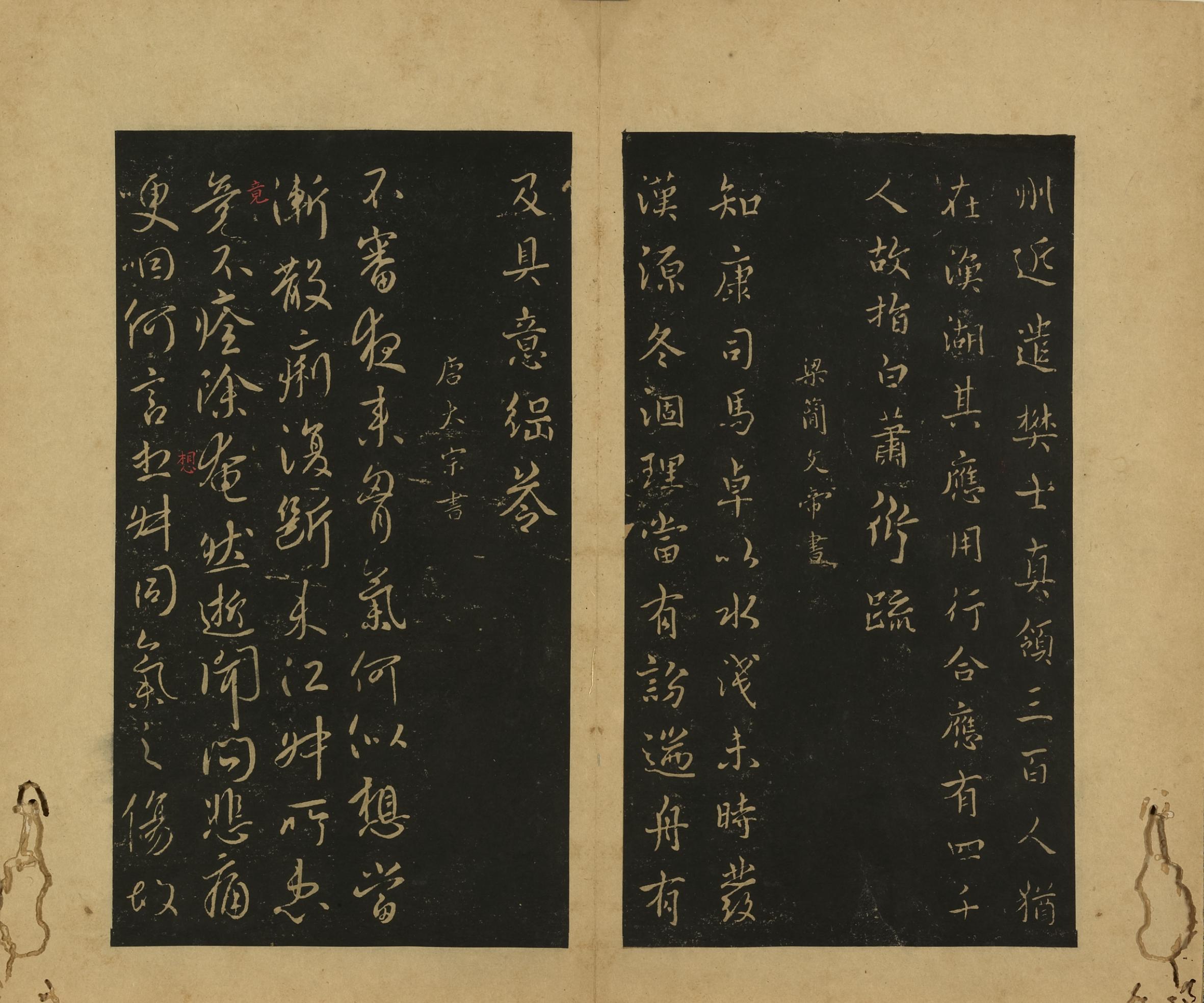

First section of T’ang dynasty ink rubbing of Ma-ku-hsien-t’an-chi regular script calligraphy carved on stele by Yen Chen-ch’ing. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

Second section of T’ang dynasty ink rubbing of Ma-ku-hsien-t’an-chi regular script calligraphy carved on stele by Yen Chen-ch’ing. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

Finally, I still wish to emphasize in order to paint, one must first cultivate integrity, then study and lastly practice calligraphy. The worthiness of a painting rests on the moral character of the artist. If the moral character of the artist is virtuous, the painting will be cherished for this alone, even when artistic merit is negligible. How much more will it be treasured if it is artistically superior too! It will certainly be passed down for posterity. Yen Chen-ch’ing (顏真卿 709-785) was a distinguished calligrapher known for loyalty and steadfastness. Hence he is exalted by later generations. For our ancestors, painting served to regulate the world. For people nowadays, painting is used to express sentiments which is the equivalent of conveying aspirations through poetry. Without learning, one is incapable of articulating these sentiments.

Taking one step back, with respect to studying and writing, excellence is not guaranteed even if one spends two or three decades on them. For composing poetry or practicing calligraphy, three or five years of training might not yield visible results. Only in painting, one can create a look-alike image with relatively little effort. Later generations choose the easy path over the difficult path. It is wrong not to start with the basics. If the ingredient of cultivation is not present in painting, there is not much difference from drawing with an expansion ruler. What is the value in this? Therefore, one starts with study, self-cultivation, and the development of moral character, then implement the common origin of calligraphy and painting. The use of the brush is all the same, one should not abandon the fundamental and seek the lowest measure.”

After Mr. P’u finished his lecture, Professor Frederick Seguier Drake (林仰山), head of the Chinese Department at the University of Hong Kong, concluded:

“Mr. P’u has covered a lot about the philosophy of calligraphy and painting today, and I have gained a little insight. Painting is an expression of the heart, looking at a painting is to look into the heart. I believe in this. The only way to cultivate moral character is to study. It is normal for foreigners not to believe this. They will say: 'How can it be that if one does not study one cannot paint?'

But Chinese painters all know in order to paint one must cultivate moral character. I believe in this. The paintings of the Six Dynasties and T’ang dynasty emphasize realism, from the few surviving masterpieces, their realistic portrayals are most convincing. When painting, one must be inside the scene. As Wang Shou-jen (王守仁 1472-1529) said: 'The universe is inside my heart'. Only then the universe can be expressed and revealed. Why is a painting precious? It is because painting, through the conduit of human thought, blends scenery and heart, and manifests it. This makes it precious.

I remember a painter from the Chia-ch’ing reign in the Ch’ing dynasty said that painting bamboo was not about painting bamboo, it was painting the heart. I also believe in this. As for brush techniques, I know very little of them. However, I believe there must be brush techniques in painting brushwork, and brush techniques come from the practice of calligraphy. Skill must be acquired before it can be expressed.”

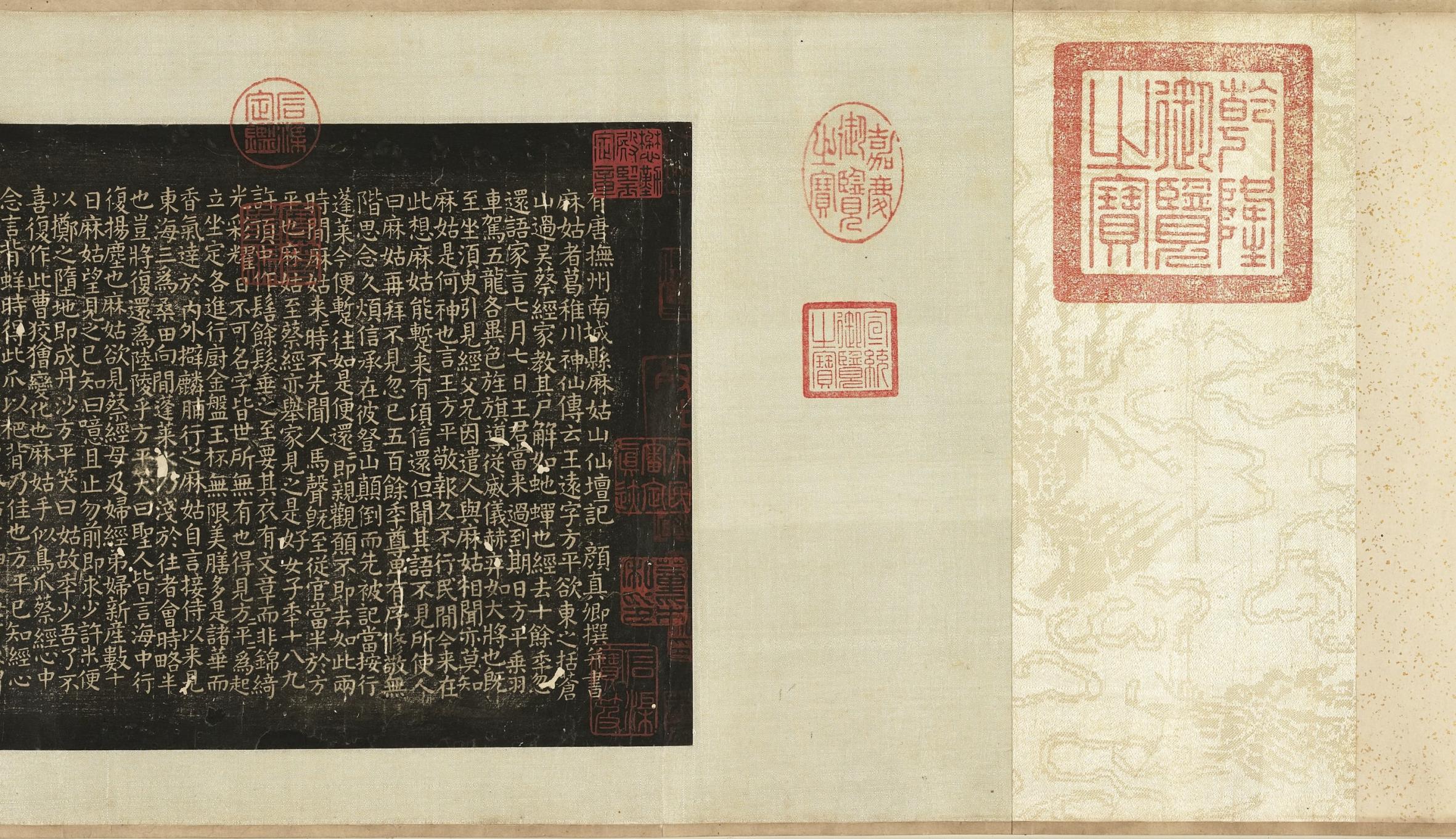

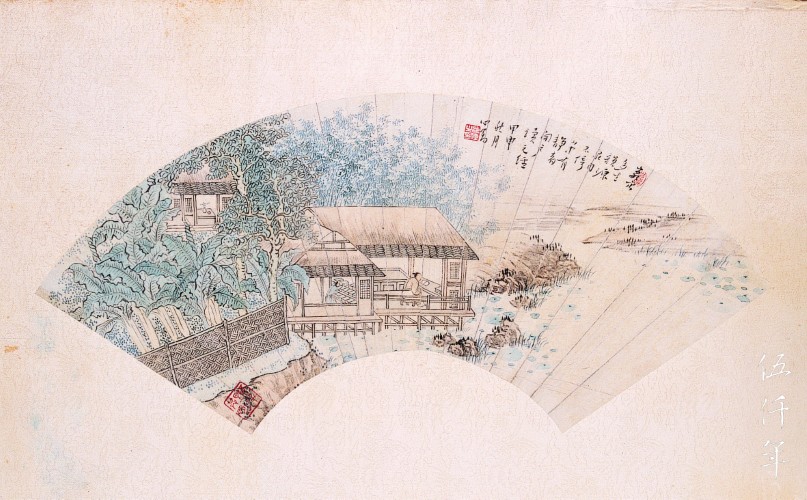

Fan painting of Reading the History Book of Yüan-ching by P’u Ju. Photograph courtesy Private Collection

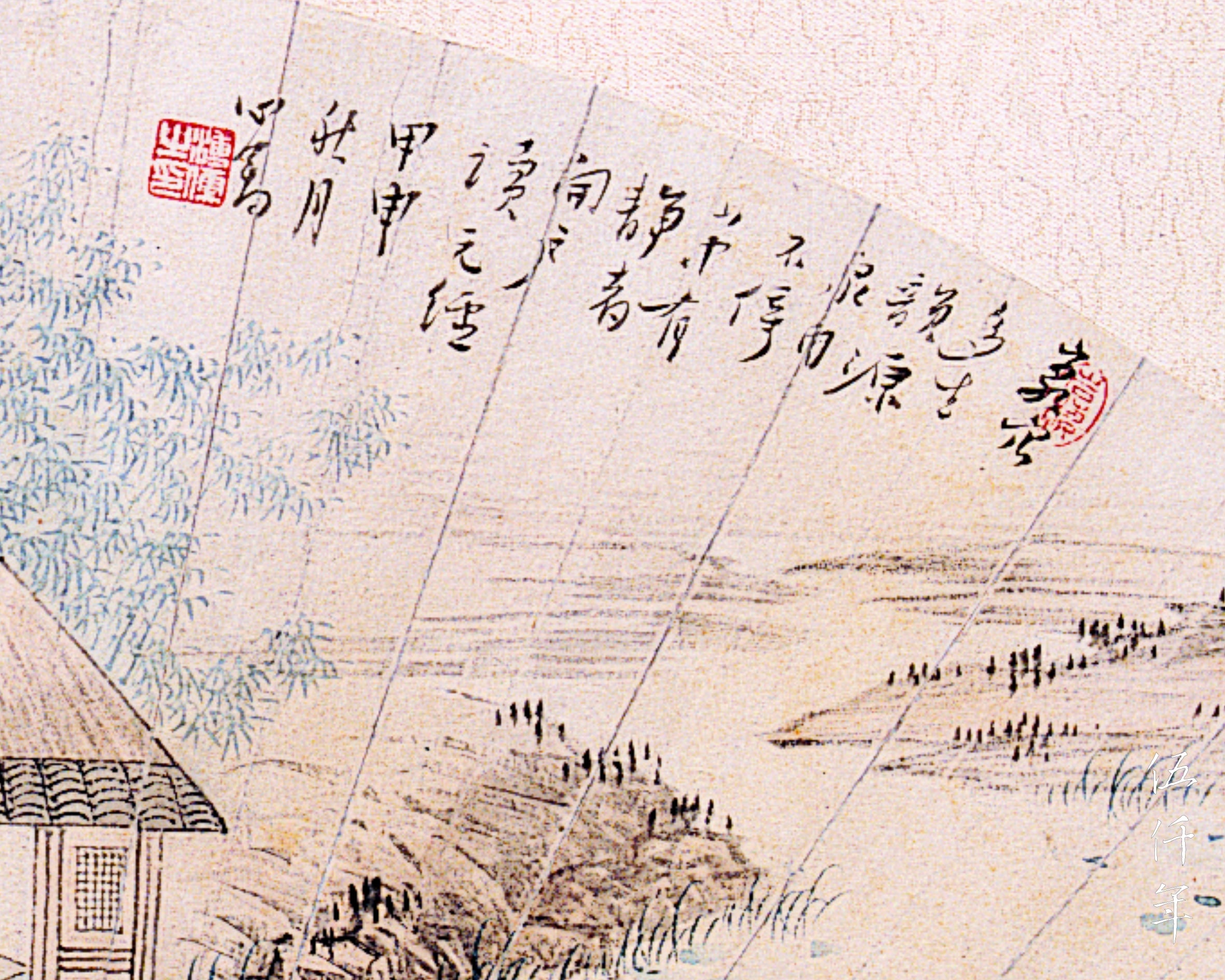

First detail of Reading the History Book of Yüan-ching by P’u Ju. Photograph courtesy Private Collection

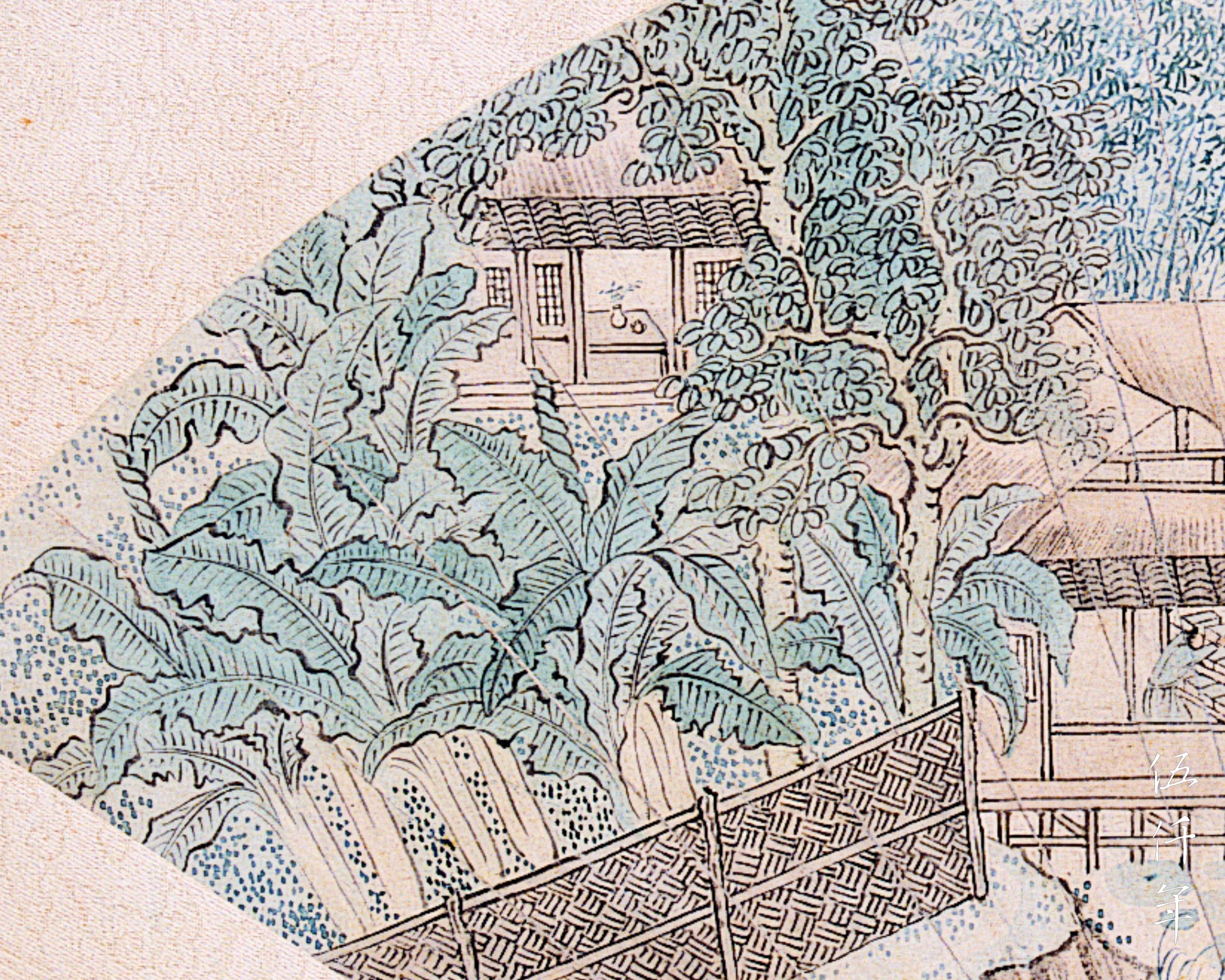

Second detail of Reading the History Book of Yüan-ching by P’u Ju. Photograph courtesy Private Collection

Third detail of Reading the History Book of Yüan-ching by P’u Ju. Photograph courtesy Private Collection

Related Contents:

Virtual Homage at the Tomb of Mr. P'u Ju (溥儒)

The Former Prince P'u Ju (溥儒), by the late Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

Chinese Literature, Calligraphy and Painting; Text of 1st Hong Kong Lecture by Mr. P'u Ju (溥儒)

Calligraphy and Painting, Text of 2nd Hong Kong Lecture by Mr. P’u Ju (溥儒)