On 2 January in the 48th year of the Republic (1959), Mr. P’u Ju gave his second Hong Kong lecture at the New Asia College which was founded by Mr. Ch’ien Mu. The College was located at Farm Road, To Kwa Wan in Kowloon at the time. On that day, Mr. Ch’ien Mu hosted the event. As they were both pre-eminent classicists, they would have a strong rapport. The text of the lecture consists of only one thousand eight hundred and more words, yet his argumentations and thoughts are precise and truthful. They are certainly cardinal teachings that should be passed on to future generations.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

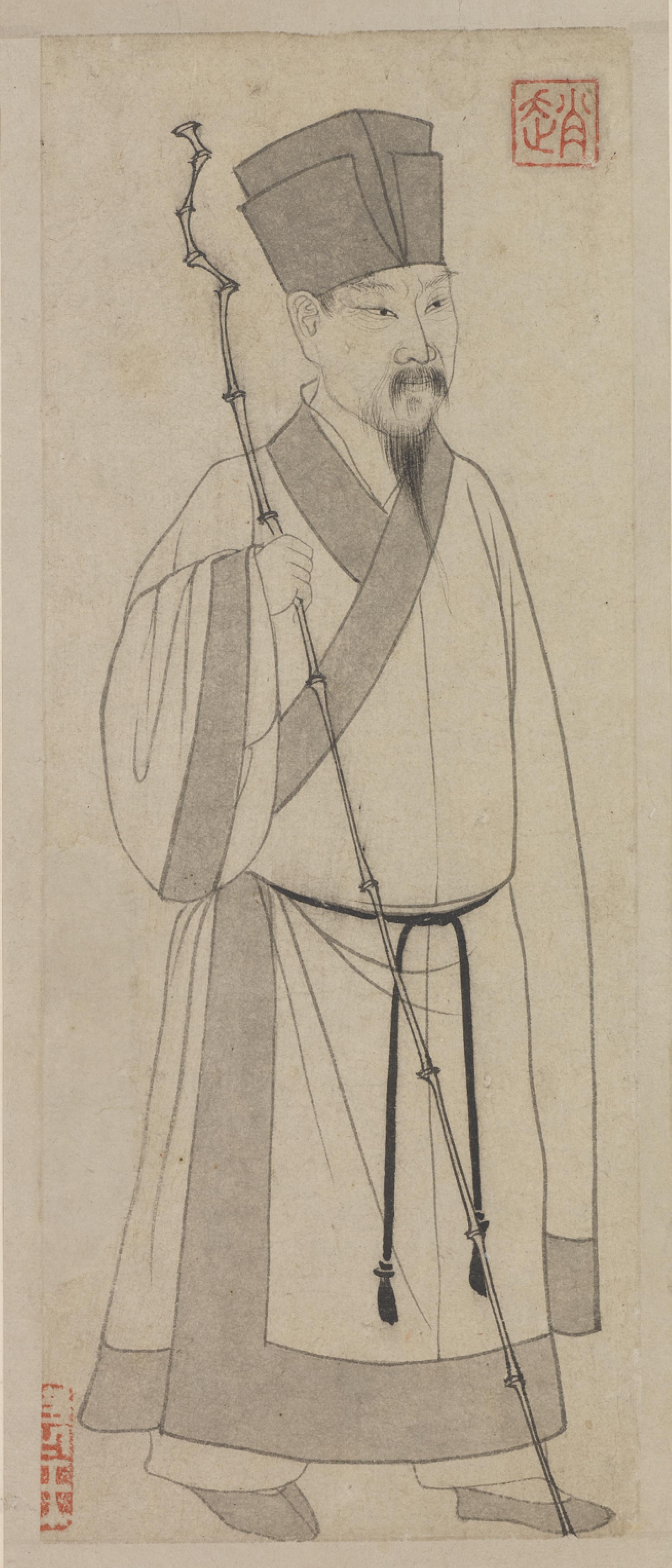

Portrait of Mr. P’u Ju

On 2 January in the 48th year of the Republic of China (1959), Mr. P’u Ju (溥儒 1896-1963), also known as Mr. P’u Hsin-yü (溥心畬), at the invitation of New Asia College in Hong Kong, delivered a lecture titled Calligraphy and Painting. The complete text of the speech was published in Wah Kiu Yat Po Newspaper (華僑日報) on 3, 4 and 5 January consecutively.

Portrait of Mr. Ch’ien Mu

Before the lecture, President Ch’ien Mu (錢穆 1895-1990) of New Asia College delivered the opening introduction by saying:

“Guests and students:

Today New Asia College is honoured to invite Mr. P’u, the distinguished master of Chinese art, to give this lecture. His name is known to all of you, and you have seen some of his masterpieces. Personally I am a novice of painting, but I would like to take this opportunity to share a few thoughts. Culture represents a nation, and the value of a nation lies in her culture. We all know the important role of art in culture. Today different races use art to achieve a deeper understanding of each other. As you know, Chinese culture holds an exalted position in the world. Western people did not understand Chinese art in the past. Now even though their understanding may not be deep, they have learnt to appreciate it. Chinese culture is rooted in the humanist spirit. A piece of art expresses the moral character and the individuality of the artist. These qualities also represent the nature of Chinese culture. Not only is Mr. P’u highly accomplished in the arts, he is also a man of high moral cultivation. Today our meeting with Mr. P’u is equivalent to encountering and appreciating a sublime work of art, for he represents the humanistic spirit of China."

Lecture text of Calligraphy and Painting by Mr. P’u Ju published in Wah Kiu Yat Po Newspaper in Hong Kong on 3 January 1959

Lecture text of Calligraphy and Painting by Mr. P’u Ju published in Wah Kiu Yat Po Newspaper in Hong Kong on 4 January 1959

Lecture text of Calligraphy and Painting by Mr. P’u Ju published in Wah Kiu Yat Po Newspaper in Hong Kong on 5 January 1959

The full text of Mr. Pu’s lecture is as follows:

“Guests, Mr. Ch’ien:

You have kindly invited me to come, and I am delighted to meet everyone here today. My learning is shallow, I can only talk briefly about what I know. I hope Mr. Ch’ien will correct me.

I want to talk about calligraphy and painting today. Calligraphy and painting are derived from literature. Things have origins and conclusions, beginnings and ends. The root of literature is ultimately set in moral conduct, how to be upright in the mind and sincere in the heart. We should not refrain from discussing this even if it sounds old fashioned. Today, fathers are not like fathers, sons are not like sons. This is because people have neglected proper conduct. Therefore, for someone who is engaged in artistic work, the person must possess high moral character. If not, there is nothing to talk about.

The artistic expressions of our country’s calligraphy and painting have continuously evolved throughout history, but their principles are constant. The principles of calligraphy, the principles of painting, have always remained the same. As the ancients used to say: ‘The use of brush never change in history.'

When I was a child, my teachers did not allow me to paint. During my studies abroad, I learned science subjects such as astronomy and biology, far from the realm of art. It was not until I returned to China at the age of twenty-eight that I began to study painting on my own. Sometimes I sketched at home, other times I journeyed through mountains and rivers. Afterwards, I would absorb the real landscapes to heart and create paintings by imagination. To paint, one must not only travel and explore, one must also be imaginative. This applies not just to painting but also to literature.

Su Shih (蘇軾 1037-1101, also known as Su Tung-p’o 蘇東坡) said: ‘The six common types of domestic animals have fixed forms, mountains and rivers have no fixed form but they have fixed principles.’ At that time, I thought what Su Shih said was so true. For example, mountains, rocks, mist, waves have no fixed form but follow clear principles. When I was learning to paint, I had no painting teacher nor companion. My learning depended entirely on deliberating and imitating the works of the ancients, and just studying by myself. Each valuable experience was hard-won by going through endless travails and difficulties. It was quite unlike today’s students who benefit from the guidances of teachers and elders, acquiring knowledge easily.

Portrait of Su Shih. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

On the matter of holding the brush, there is no fixed form either. Su Shih said: ‘Hold the brush with no fixed form, just follow natural inclination.’ Therefore, there is no need to be rigid and inflexible while holding the brush. One should ensure that the fingers are firm, avoid erratic movement, use the strength from wrist or elbow, apply the brush steadily and not senselessly. Of course, one must pay attention to centering the tip of the brush in the middle of the stroke. What we call ‘centered tip’ (中鋒) means that the force comes from the center. When lifting the brush, it should be like lifting an object, hold the central balance point so that the brush is steady. Wield the brush like a meat cutting knife, only the middle of the blade can cut through and cut well. What we call ‘concealed tip’ (藏鋒) means concealing the tip of the brush in the middle without exposing it. This is used in writing seal script and clerical script. One should learn to write calligraphy before practicing painting. Otherwise, the painting is superficial, decorative, with little substance.

Portrait of Mr. P’u Ju painting with a brush

The reason the ancients achieved greatness is due to sincerity. When the ancients embarked upon an undertaking, they devoted the totality of their lifelong dedication. If we want to achieve greatness in art, we also need to concentrate on sincerity.

By writing calligraphy well, one can then paint well. The two are connected. If one cannot write calligraphy well, naturally one cannot paint well.

Top of Form

Bottom of Form

To reach peak artistry, one must first attain moral cultivation of the character. To attain moral cultivation of the character, it is necessary to read and study extensively. By acquiring a scholarly aura, one will then possess rectitude and proper demeanor. What we call proper demeanor is earned through self-cultivation, it is something beyond the physical facial features, as in the saying: ‘With poetry and books in the belly, an air of refinement naturally emanates.’ As for those with no learning and cultivation, there is nothing to be done. When a person gains moral cultivation and refinement of the character through reading and studying, everything can be well executed. For example, even though Tseng Kuo-fan (曾國藩 1811-1872) and Wang Shou-jen (王守仁 1472-1529) were literati, because of their fine scholarships, they were also distinguished military leaders.

When I am in Taiwan, many people ask me to authenticate calligraphy and paintings. In fact, once it is clearly explained, anyone can undertake authentication. All that is needed is to study plenty of genuine works, and fakes can be identified at a glance.

There were many sculptures in the Northern Dynasties, and there were many painted images in the Southern Dynasties. Before Buddhism came to China, painting served practical purposes. Beginning with Wang Wei (王維 692-761), painting became an expression of artistic impulse. Yet intellectual thought is still incorporated. As for the casual undertaking of calligraphy and paintings for recreation purpose, this came about after the T’ang dynasty.

Handscroll painting of Snow Scene Along the Shore by Wang Wei of the T’ang dynasty. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

Hanging scroll of Boats and Pavilions by Li Ssu-hsün of the T’ang dynasty. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

In painting, the terms ‘Southern School’ and ‘Northern School’ are used. This is actually incorrect. Painting should not be divided into schools. These terms were derived from Zen Buddhism. People at the time were fond of fashionable terms, hence the terms of Southern School and Northern School came into being. For instance, when we say Wang Wei (王維) belonged to the Southern School and Li Ssu-hsün (李思訓 651-716) belonged to the Northern School, they do not make sense at all.

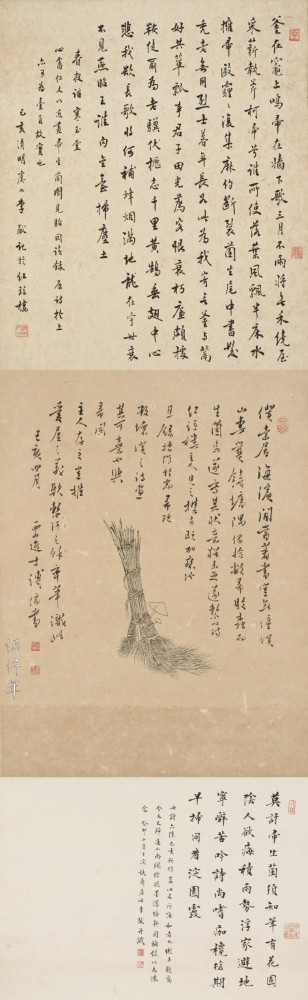

Hanging scroll of Broom with Fungus by Mr. P’u Ju, with upper and lower colophons by Mr. Li Yu (李猷 1915-1997). Photograph courtesy Mr. Tung Liang-yen

From ancient time to modern time, it has always been customary to inscribe colophons and poetry on calligraphy and paintings. In a humble alley in Taiwan, I once painted an old broken broom. I inscribed a lengthy classical poem that attributed meaning to the broken broom.

Many friends saw the painting. They were happy to inscribe a few lines of colophons. Over time, the broken broom becomes quite interesting. A painting without word is as bland as a silent movie. By inscribing poetry, one’s thoughts and yearnings can be expressed, emotions of the artist can be conveyed. It will be excessive to expect that everyone can write fine poetry and essays, but people should at least be proficient. Even for engineers and scientists, I hope they can write better so that they too can captivate their readers. Hence let me persuade those who are learning to paint, invest time to learn to write poetry. While mastery is difficult, competence is certainly attainable.

As for the use of ink, the ancients said: ‘Treasure ink like gold.’ This does not mean ink is too precious to use, rather, ink is to be used with extra care. Regarding painting, if one is truly talking about art, it is not about colour. That is why the ancients used water and ink for their paintings. The finest colours still cannot capture the true luster of sceneries and objects. So it is better to use ink, akin to a beautiful woman who reveals her attraction even without makeup.

Regarding the application of colour, this is not something that can happen instantly. It takes at least ten or twenty layers of gradual shading from light to dark to achieve good colouring. Only then can colour possess depth and be emotionally moving.

In summary, to learn painting, one must first read and study, one must first practice self-cultivation. After acquiring the moral foundation of humanity, then one can start to learn painting. This is what I mean by ‘origins’ in the sentence I put forward at the beginning: ‘things have origins and conclusions’. One must first look after the ‘origins’.”

Exterior view of New Asia College campus at Farm Road, To Kwa Wan in Kowloon around late 50s and early 60s. Photograph courtesy oldhkphoto.com

Mr. Ch’ien Mu concluded the lecture with these remarks:

“Mr. P’u provided many valuable insights in his talk today. Nowadays, Chinese people face an obstacle, and that is what he sees: A person who learns to paint should first study the Confucian Classics, the works of Neo-Confucianists, then move on to literature, and finally delves into painting. This ideal is too lofty. Although we know this path, it is indeed hard to reach. Conversely, people from the Western world advocate art for art’s sake, using an objective approach that everyone can follow, without first emphasizing ideology or pursuing such theory.

Mr. P’u is the foremost master of Chinese art. Although he lives in a humble alley, he is completely at ease. Just now, he talked about painting a broom. This is not just about a painting, it is a philosophy of life, a state of mind. It also encapsulates his moral character and self-cultivation. Therefore, when we look at paintings by other artists, we find them savourless, we can no longer appreciate paintings by professional artists.

After hearing what Mr. P’u said just now, at the very least, everyone knows of the highest state in life, to first become an erudite person, before becoming a specialist. Chinese culture is inward leaning, Western culture is outward leaning. Chinese people wishes to reach the highest state in life, each of you should certainly acknowledge this and strive in this direction. It is not difficult to achieve, as Mencius said, everyone can learn and everyone can succeed. Mr. P’u has spoken a lot about principles that start from small to large, from shallow to deep. Everyone should bear them in mind.”

Detail of Broom and Fungus by Mr. P’u Ju. Photograph courtesy Mr. Tung Liang-yen

Related Contents:

Virtual Homage at the Tomb of Mr. P'u Ju (溥儒)

The Former Prince P'u Ju (溥儒), by the late Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

Chinese Literature, Calligraphy and Painting; Text of 1st Hong Kong Lecture by Mr. P'u Ju (溥儒)

On the Common Origin of Calligraphy and Painting, Text of 3rd Hong Kong Lecture by Mr. P’u Ju (溥儒)