A country’s rise and fall is regular and repetitive. To be born in a time of peace, or a time of annihilation, is divine providence devoid of choice. But to uphold goodness and eradicate evil, to preserve loyalty and crusade integrity, can be ascended.

Huang Tsung-yen (黃宗炎 1616-1686) of the Ming dynasty once raised a righteous army against the invading Manchus, he was defeated and escaped to a monastery. Later he was twice arrested and was almost executed. He died poverty-stricken, yet he never contemplated on surrendering.

Hand carved inkstones by Huang Tsung-yen was mentioned in books but rarely seen. This inkstone in particular has calligraphy engraving by Chiang Shih-chieh (姜實節 1647-1709) on the sides and calligraphy engraving by Mei Ch’ing (梅清 1623-1697) on the box cover. It is a grand artwork that encapsulates the noble spirits of three Ming loyalists. It encourages the thinking men and women of today to break the cycle of rise and fall by moral interventions, to unburden life and death by sanctifying Compassion and Righteousness.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

Portrait of Emperor Ch’ung-chen

In the 17th year of the Ch’ung-chen reign, 1644, the Ming Emperor hanged himself at Mei-shan after the sacking of the capital Peking by the rebel army of Li Tzu-ch’eng (李自成). Ming dynasty nearly ended, but did not. Armies were raised across the land, they fought to the death one after the other, the throne of the emperor was continuously occupied by royalties, and Ming loyalists spread their message far and wide. After the fall of mainland China, in the 15th year of the Yung-li reign, 1661, Koxinga (鄭成功) recovered Taiwan, and carried on the Ming dynasty in a remote corner of China.

In the 37th year of the Yung-li reign, corresponding to the 22nd year of the K’ang-hsi reign, or 1683, Taiwan surrendered to the Ch’ing dynasty. Thirty nine years after the suicide of Emperor Ch’ung-chen (崇禎), Ming dynasty finally came to an end. Ming dynasty did end, in a way not. The rectitude, scholarship, literature and arts of the Ming loyalists dominated the early decades of the Ch’ing dynasty. Whenever later generations refer to any worthy moral conduct, scholarship and arts in early Ch’ing, Ming loyalists are always cited as exemplars.

Portrait of Chang Huang-yen

Failing to recover the occupied land, the Ming loyalists harnessed the name of another prominent loyalist Chang Huang-yen (張煌言) as founder of an underground organization to keep the memory of Ming dynasty alive, known as Heaven and Earth Society. Their goal was to patiently explore future opportunities to bring down the Ch’ing dynasty. When Dr. Sun Yat-sen, Father of the Republic of China, toppled the Ch’ing dynasty in 1912, he relied substantially on the still intact Heaven and Earth Society. His contemporary revolutionary Chang Ping-ling (章炳麟) wrote an introduction to The Works of Chang Huang-yen, his words are:

“I was born two hundred and forty years after Mr. Chang. Those whom Mr. Chang opposed and combatted are now getting weaker, yet the distinction between foreigners and Chinese, the abomination from nine generations, the endearment towards one’s own race, are however blurred in China…. For those who have read Mr. Chang’s writings and still condone growing old with the foreign barbarians, they are certainly inhuman.”

Two scores and two hundred years from then, the Ming loyalists could still instigate the demise of Ch’ing dynasty from the world beyond. Ming dynasty had long ended, yet somehow not.

Inkworks and relics from the Ming loyalists are dearly treasured by later generations, for those with moral integrity are few since time immemorial. While those with moral integrity are hard to find in our contemporary world, they can be found in history. A historic relic, small it may be, carries the loyalist spirit, braving through the turmoils and upheavals of history. Even though the loyalist spirit is encountered in smouldering ashes, later generations can still recognize that there is indeed righteous spirit in the world.

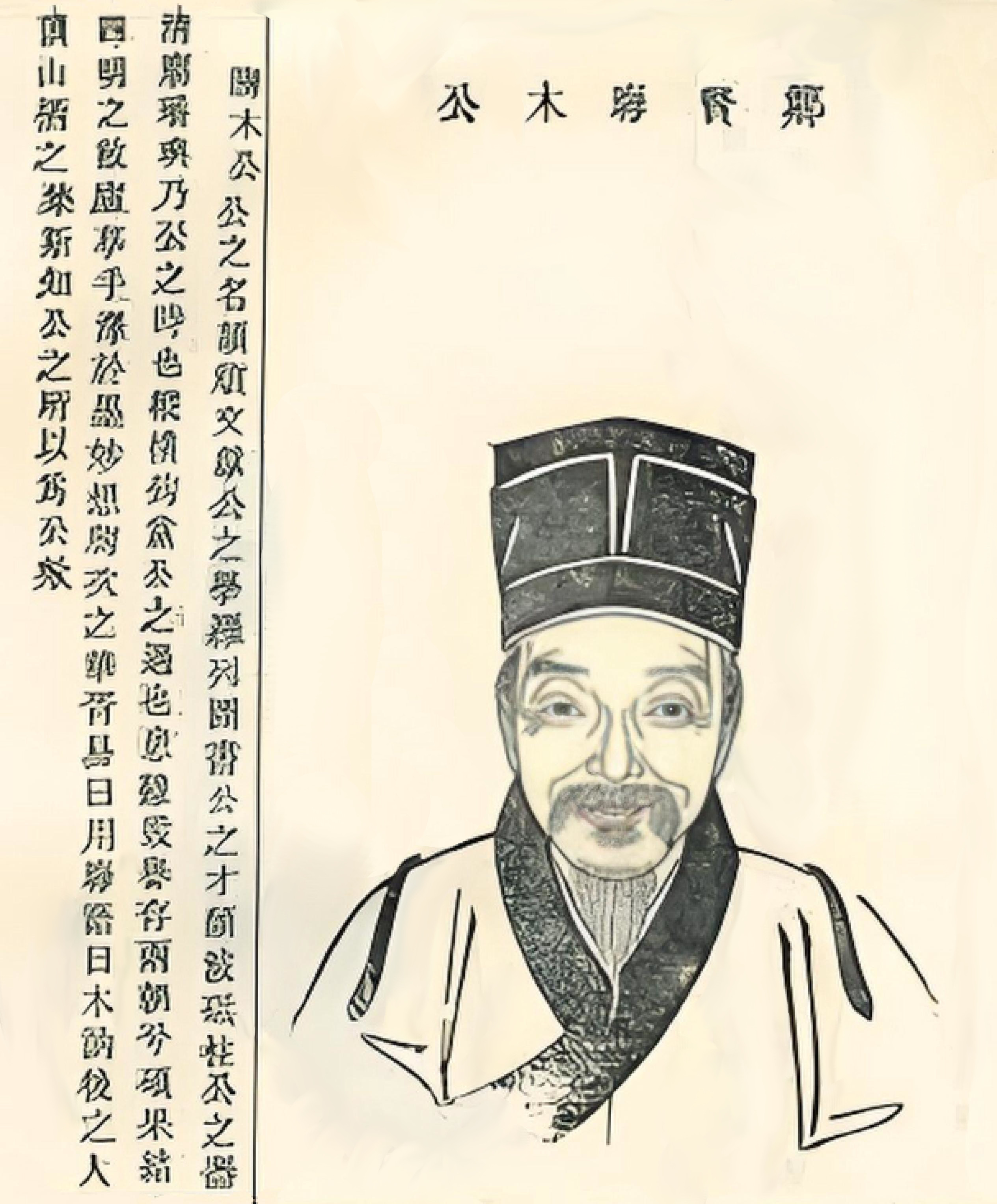

Portrait of Huang Tsung-yen

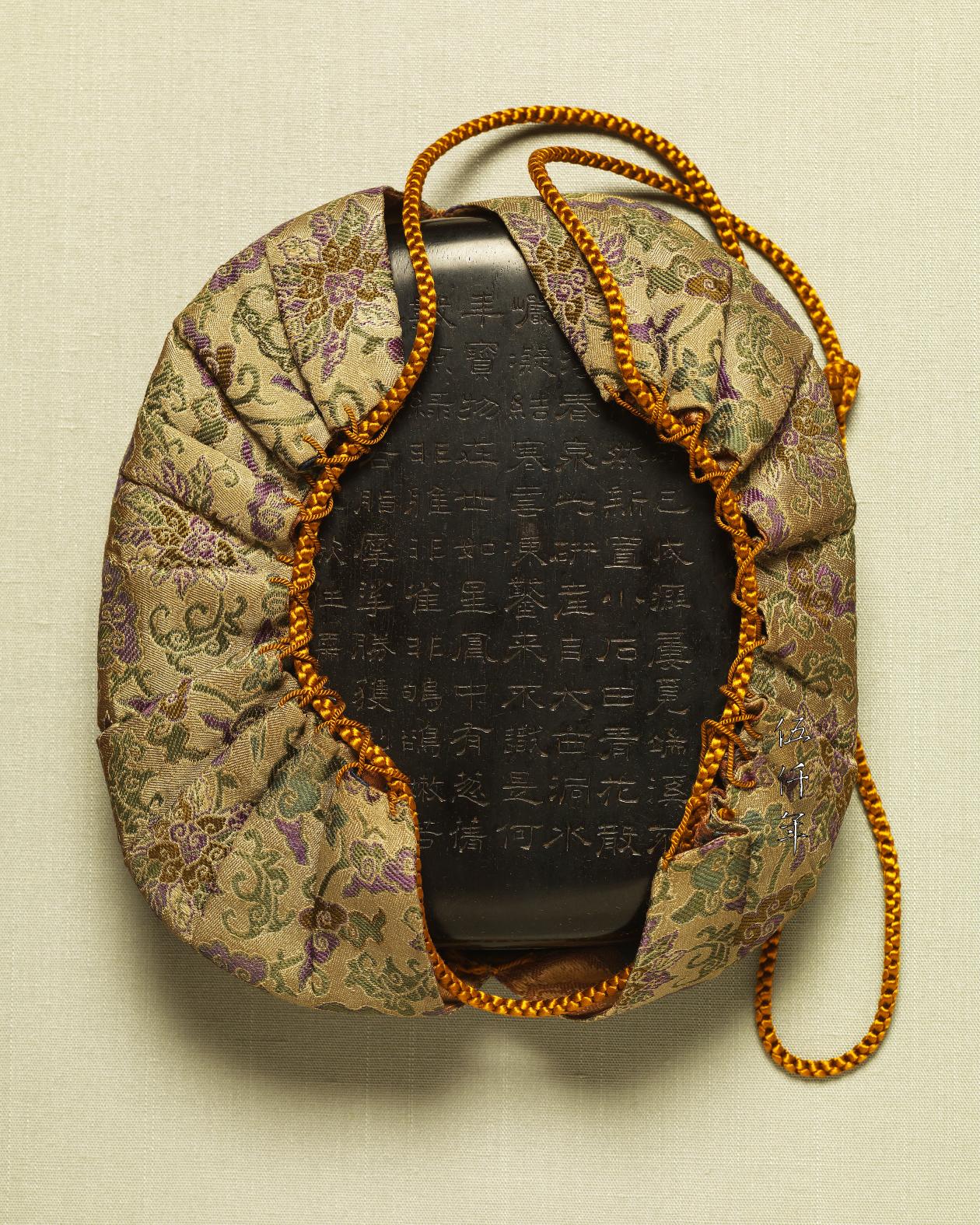

Inkstone carved by Huang Tsung-yen inside a pouch

There is an inkstone carved by the Ming loyalist Huang Tsung-yen (黃宗炎) in my collection, the sides of the inkstone was engraved with a poem by Chiang Shih-chieh (姜實節), and the box cover was engraved with a poem by Mei Ch’ing (梅清). This inkstone encompasses the writings of three late Ming and early Ch’ing artists, a truly inspirational piece.

Front of inkstone and box cover

Back of inkstone and box base

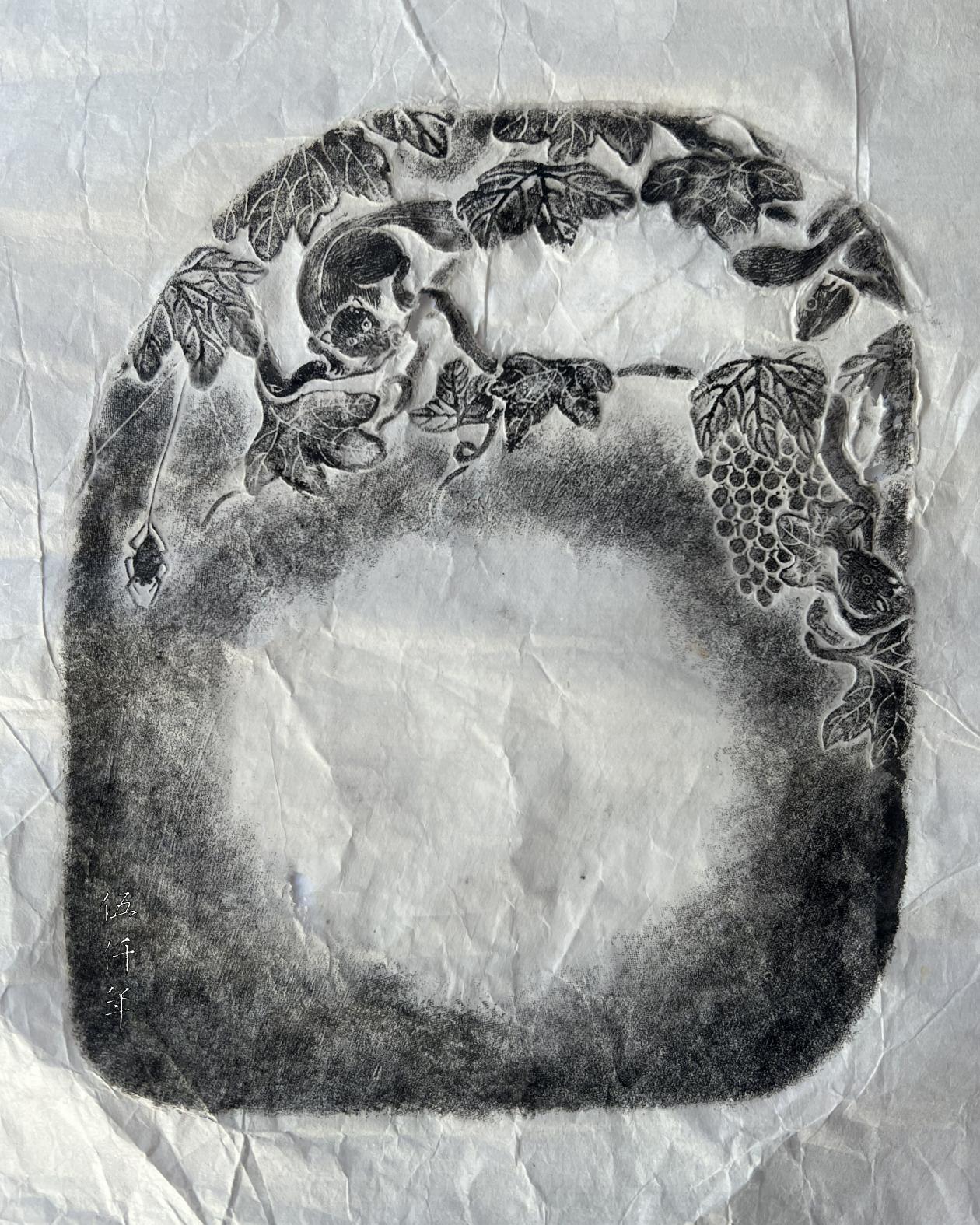

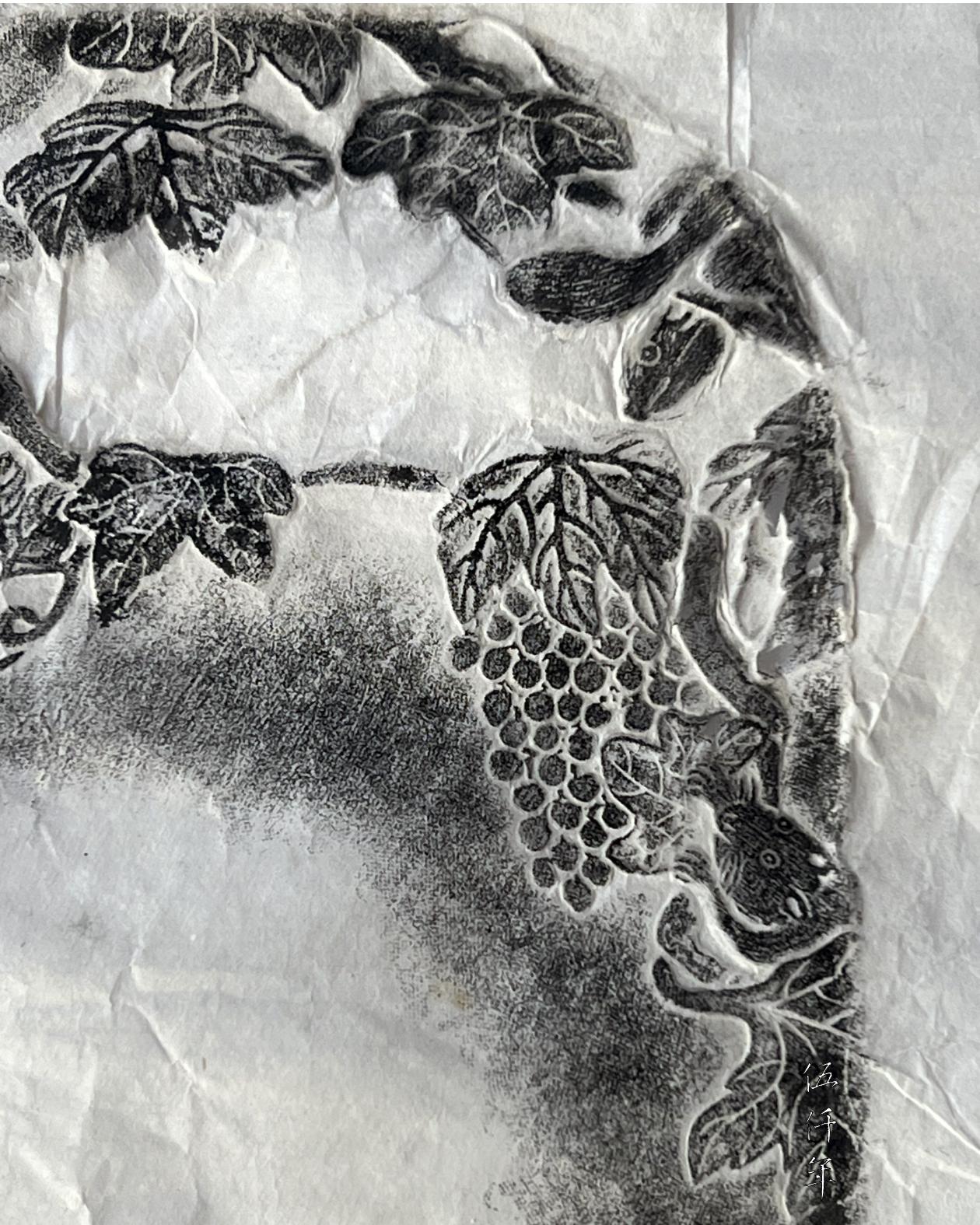

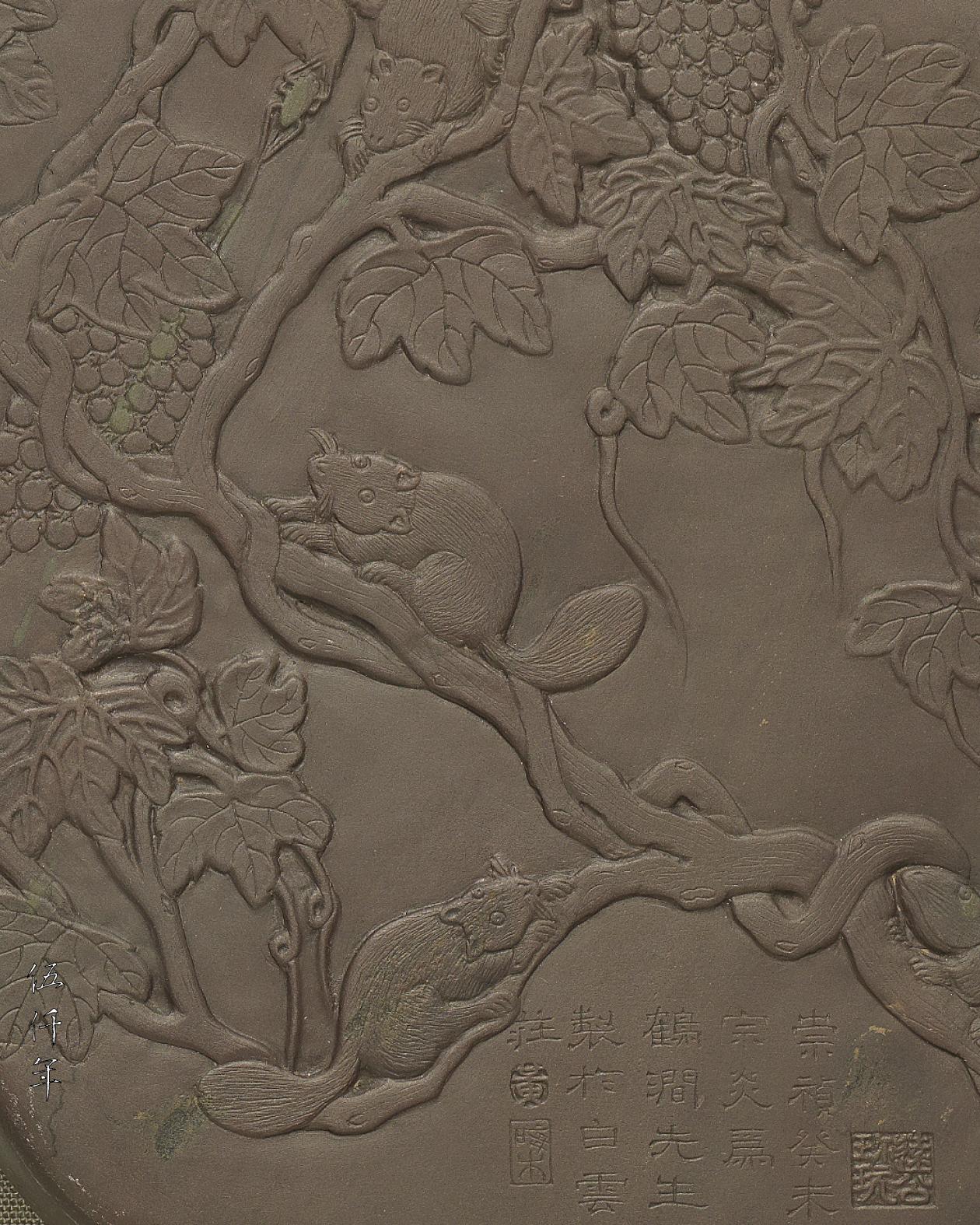

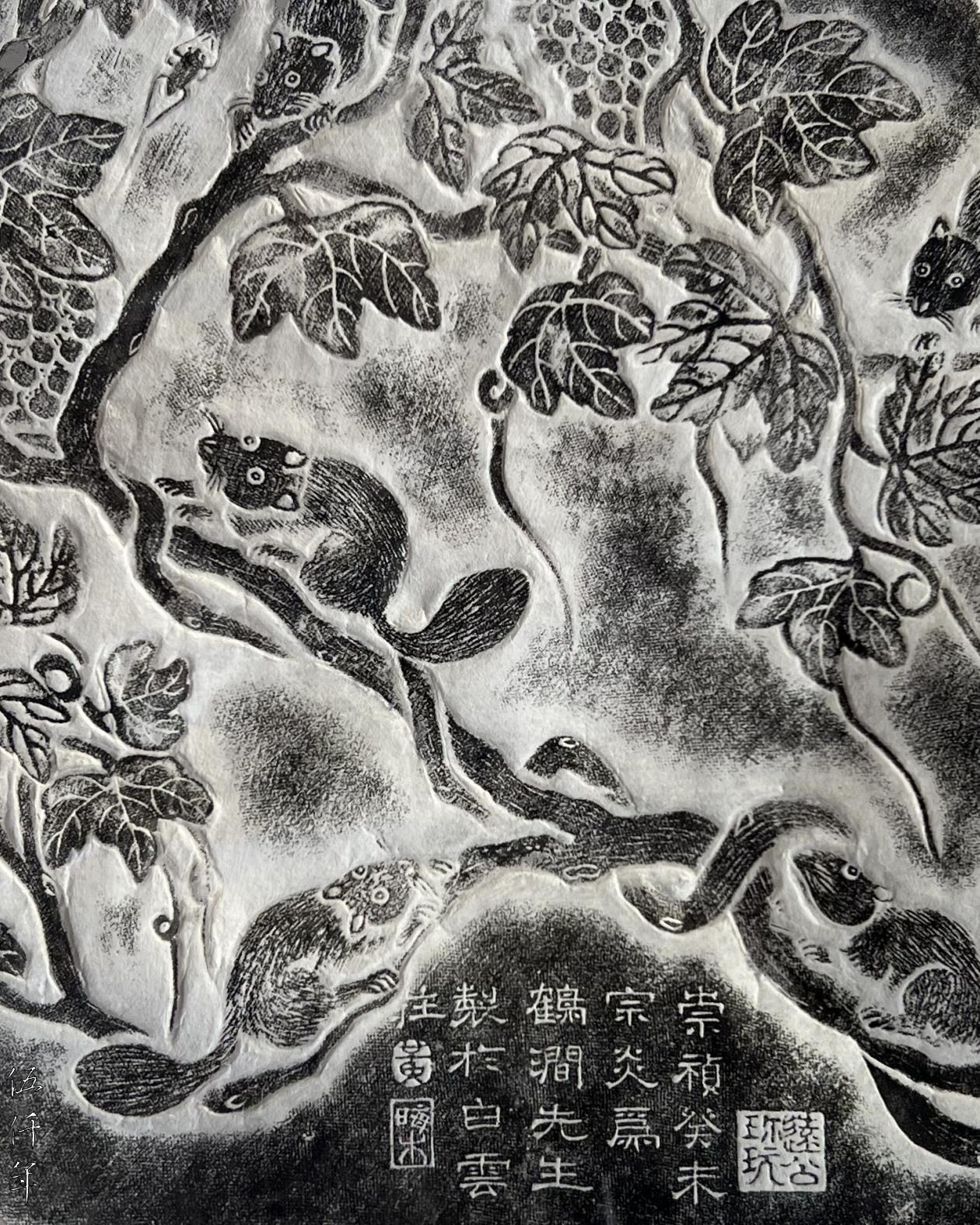

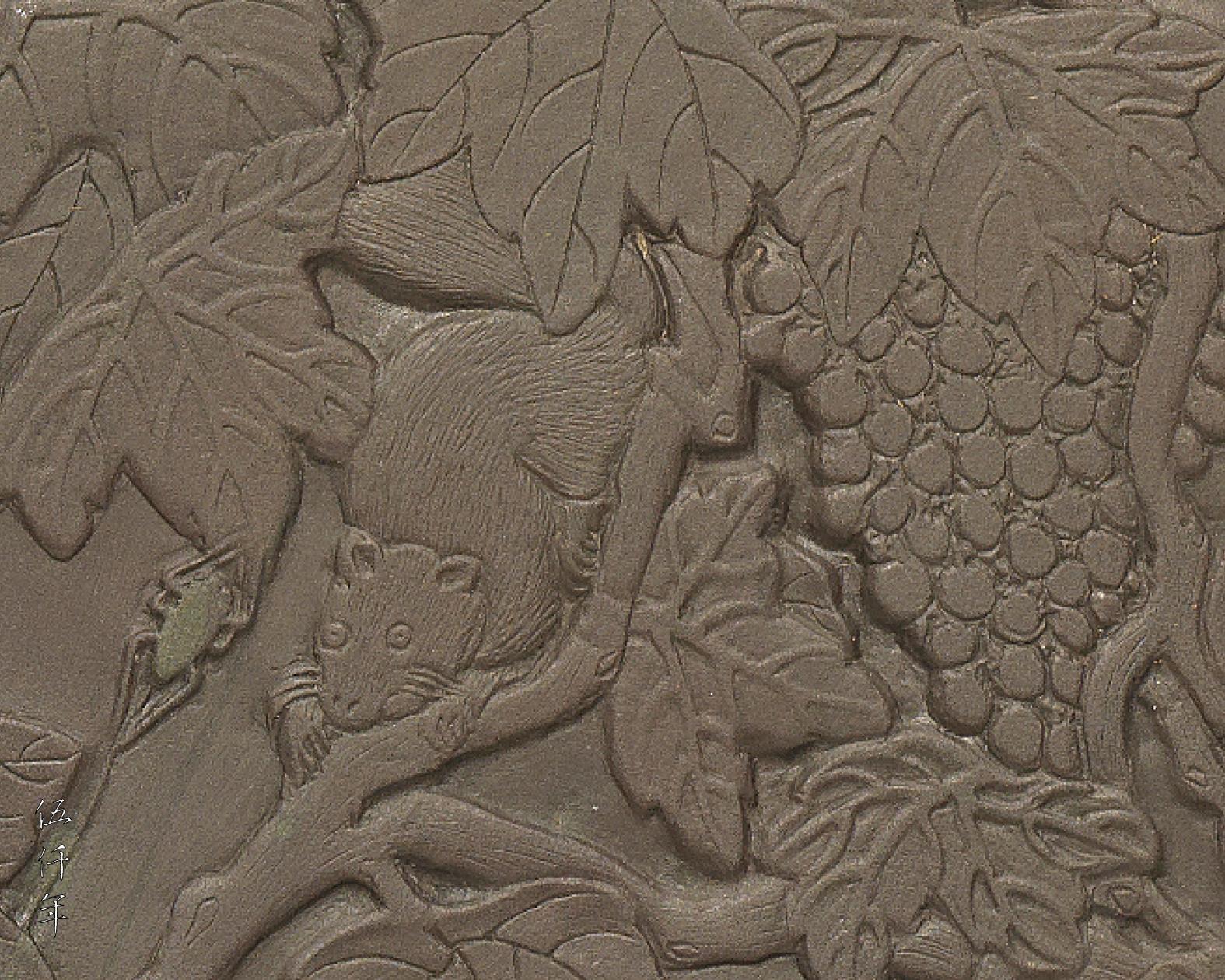

The top of the inkstone, around the water reservoir, was carved with squirrels and grapes. There are three squirrels resting and roving on the branches, and a spider hanging from the tree. The back of the inkstone was fully carved with squirrels and grapes. There are a total of five squirrels resting and roving on the branches, and another hanging spider.

Squirrel and grape is an auspicious symbol popular in the Ming and Ch’ing dynasties, to bless a family with multitudinous children and grandchildren. The body of the spider resembles the word happiness, so a hanging spider signifies “happiness descending from heaven”. Altogether this is an inkstone that symbolizes good fortune.

Front of inkstone carved by Huang Tsung-yen

Ink rubbing of inkstone front carved by Huang Tsung-yen

Top right detail of inkstone front, showing squirrels and grapes around the water reservoir

Ink rubbing of top right detail of inkstone front, showing squirrels and grapes around the water reservoir

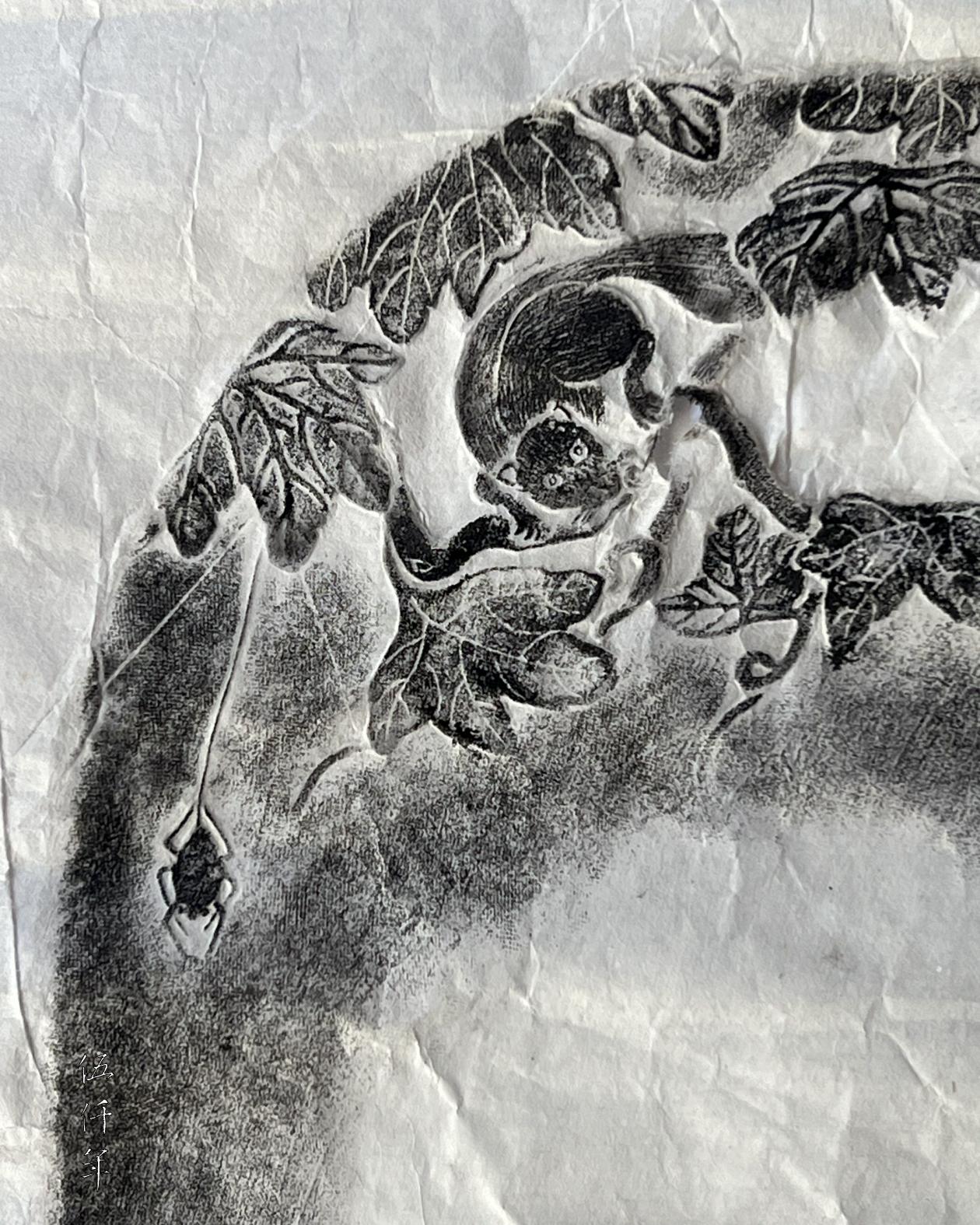

Top left detail of inkstone front, showing squirrel and spider

Ink rubbing of top left detail of inkstone front, showing squirrel and spider

Back of inkstone carved by Huang Tsung-yen

Ink rubbing of back of inkstone carved by Huang Tsung-yen

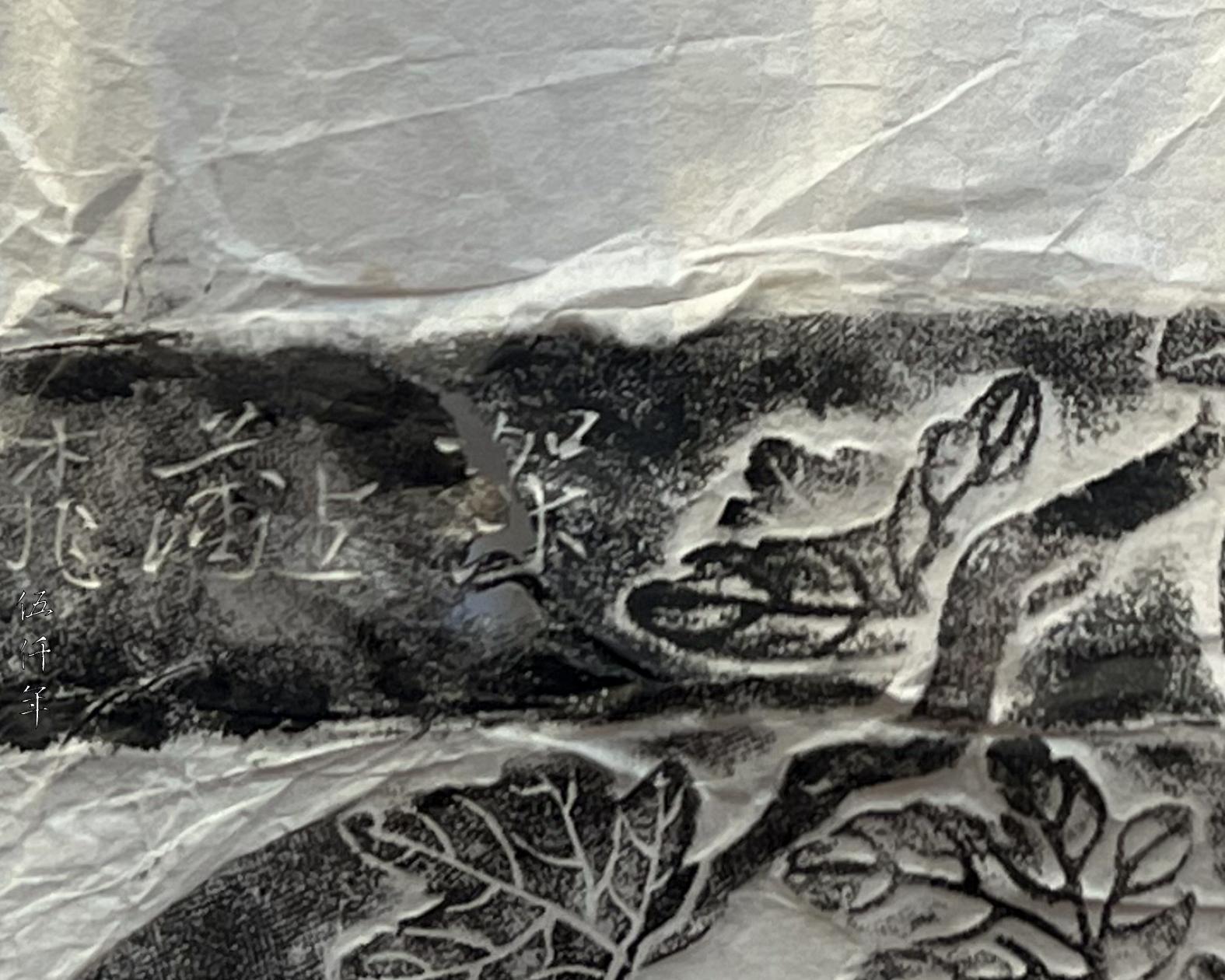

Detail of inkstone back, showing squirrels, grapes and calligraphy inscription

Ink rubbing of detail of inkstone back, showing squirrels, grapes and calligraphy inscription

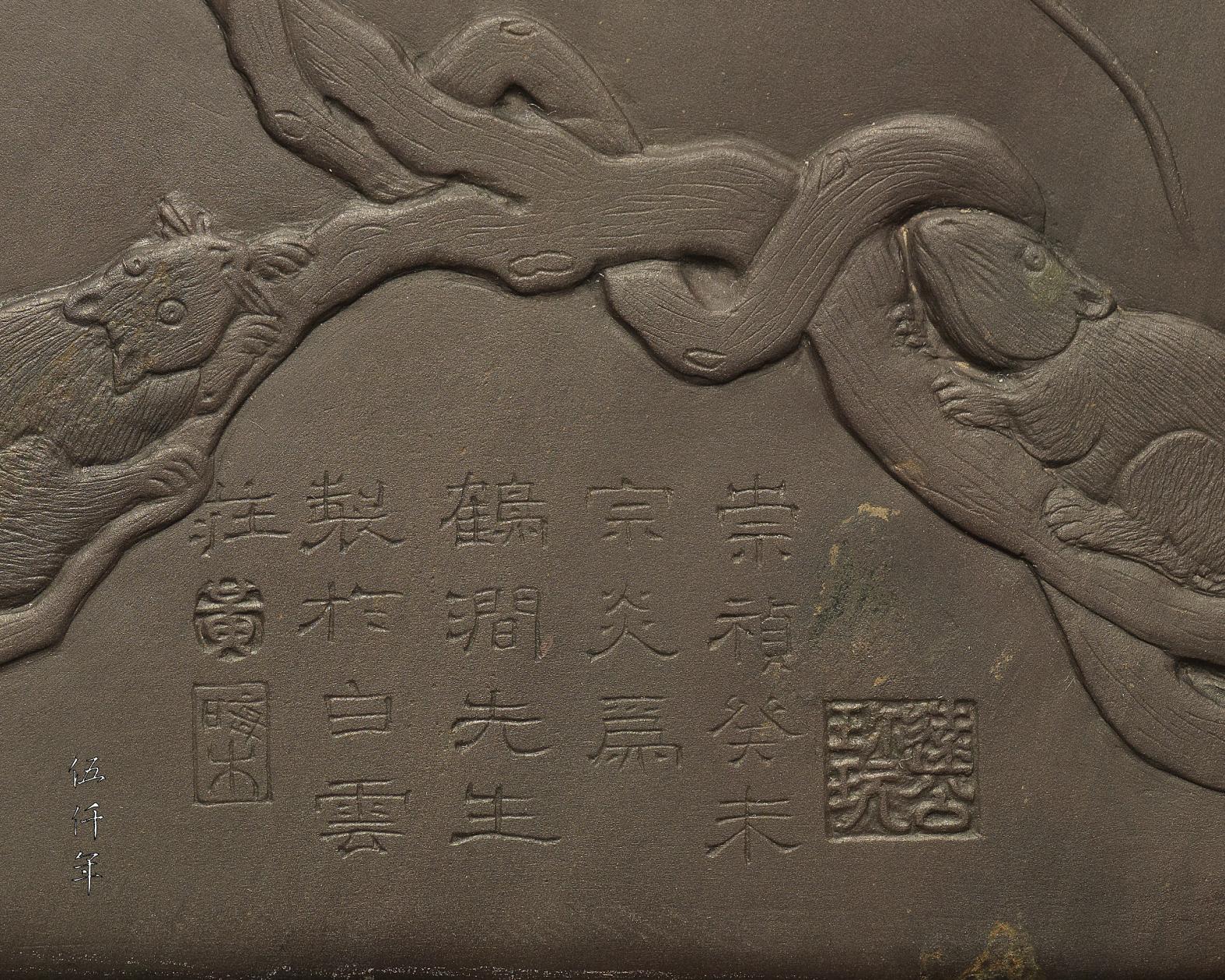

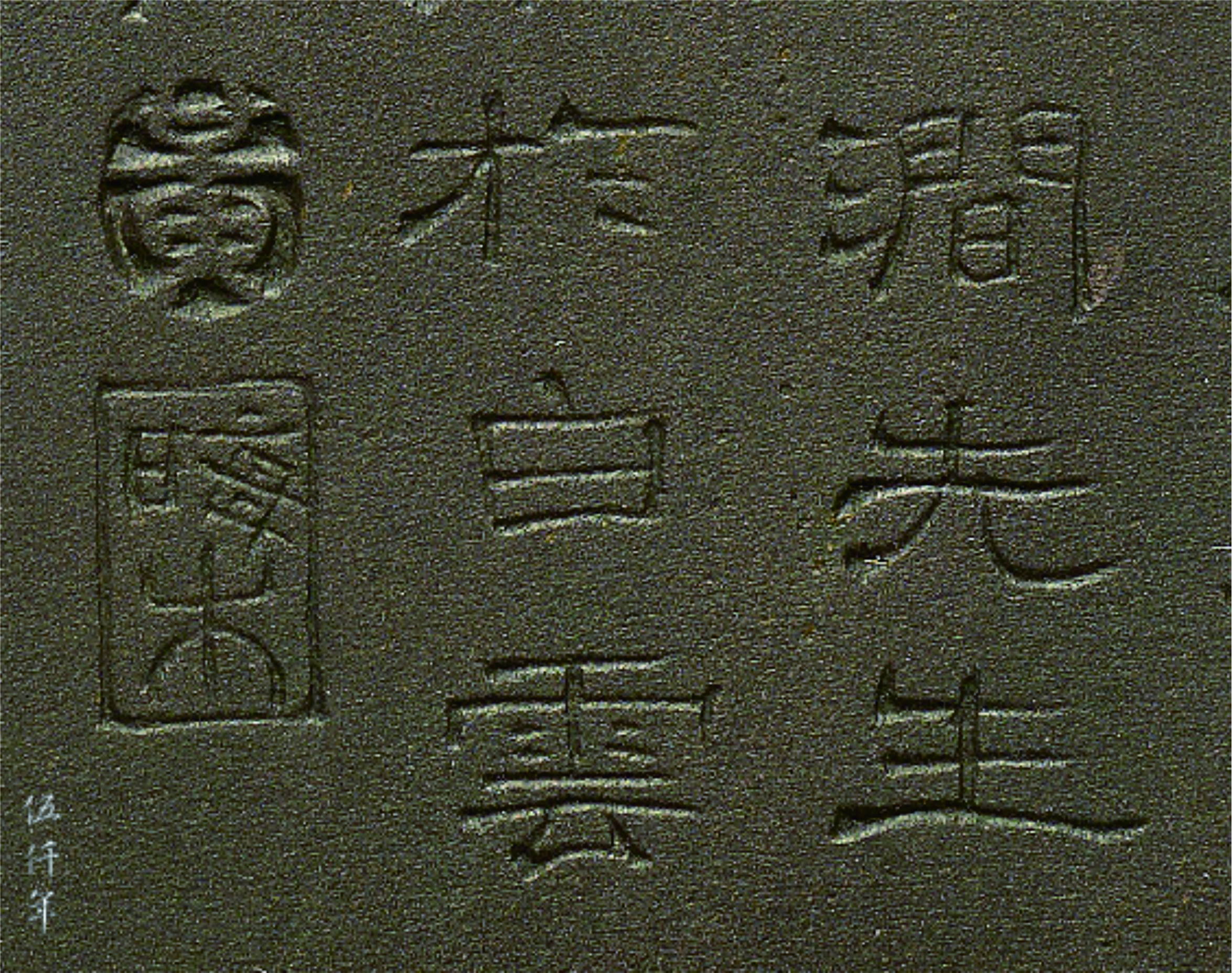

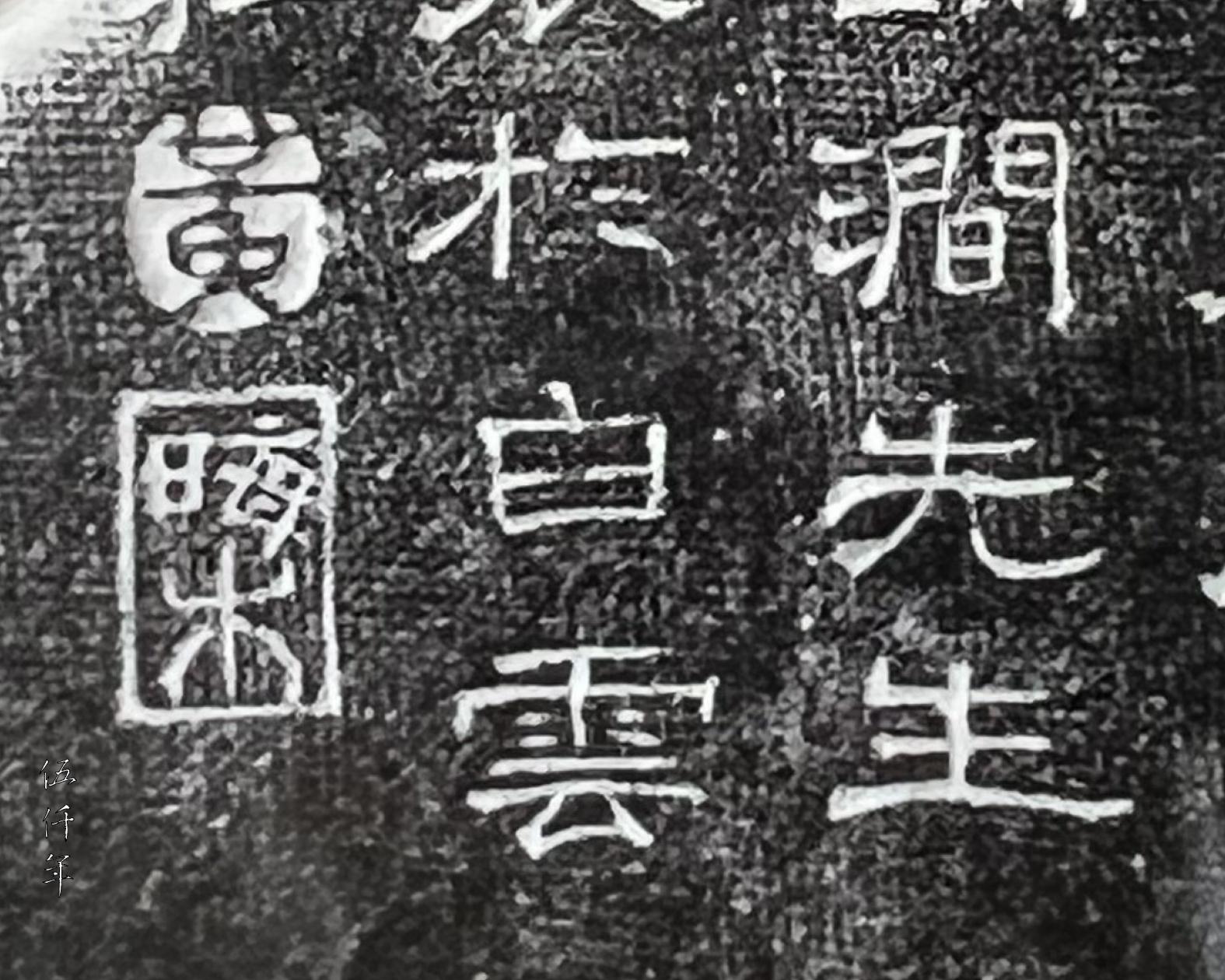

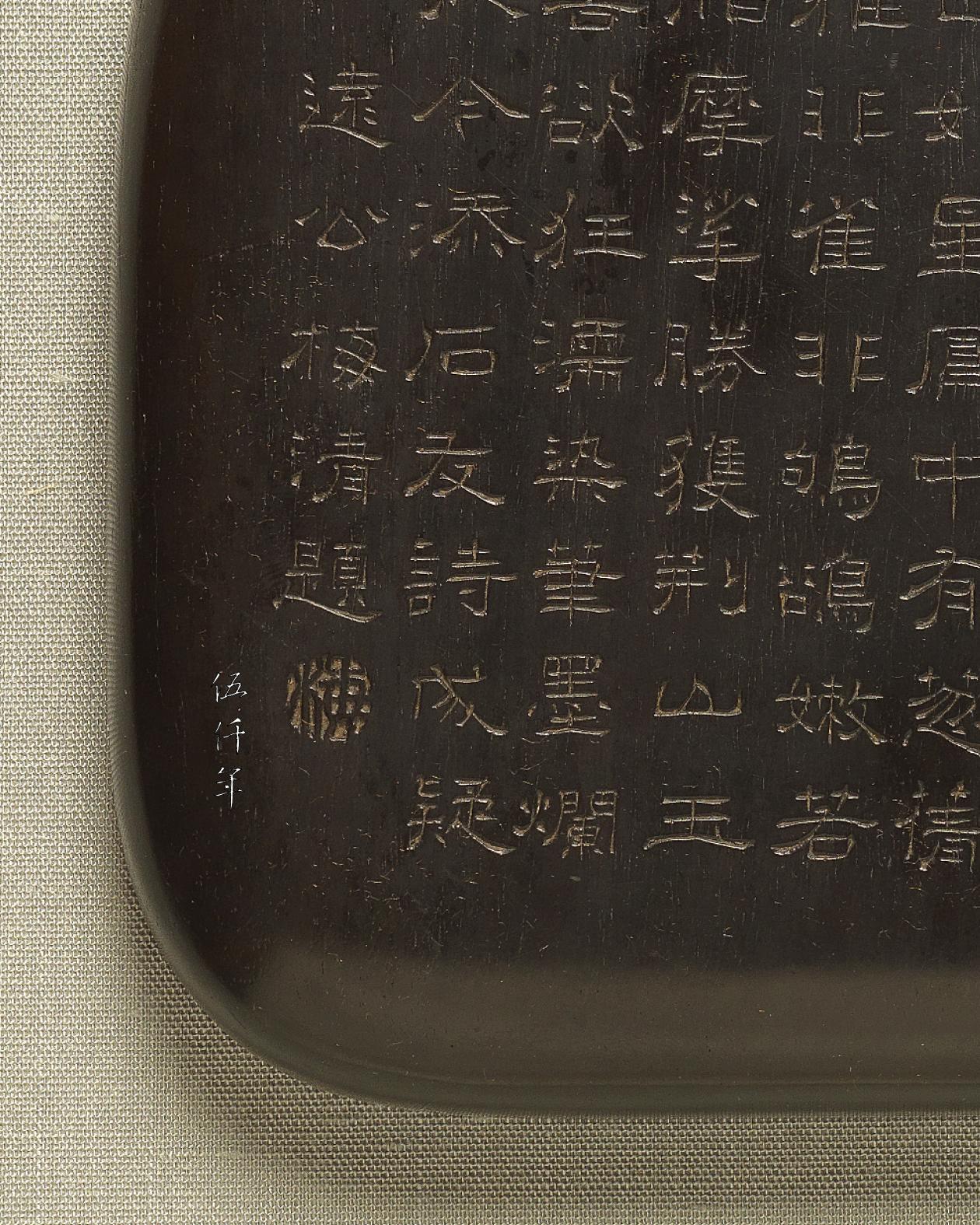

Detail of calligraphy inscription by Huang Tsung-yen

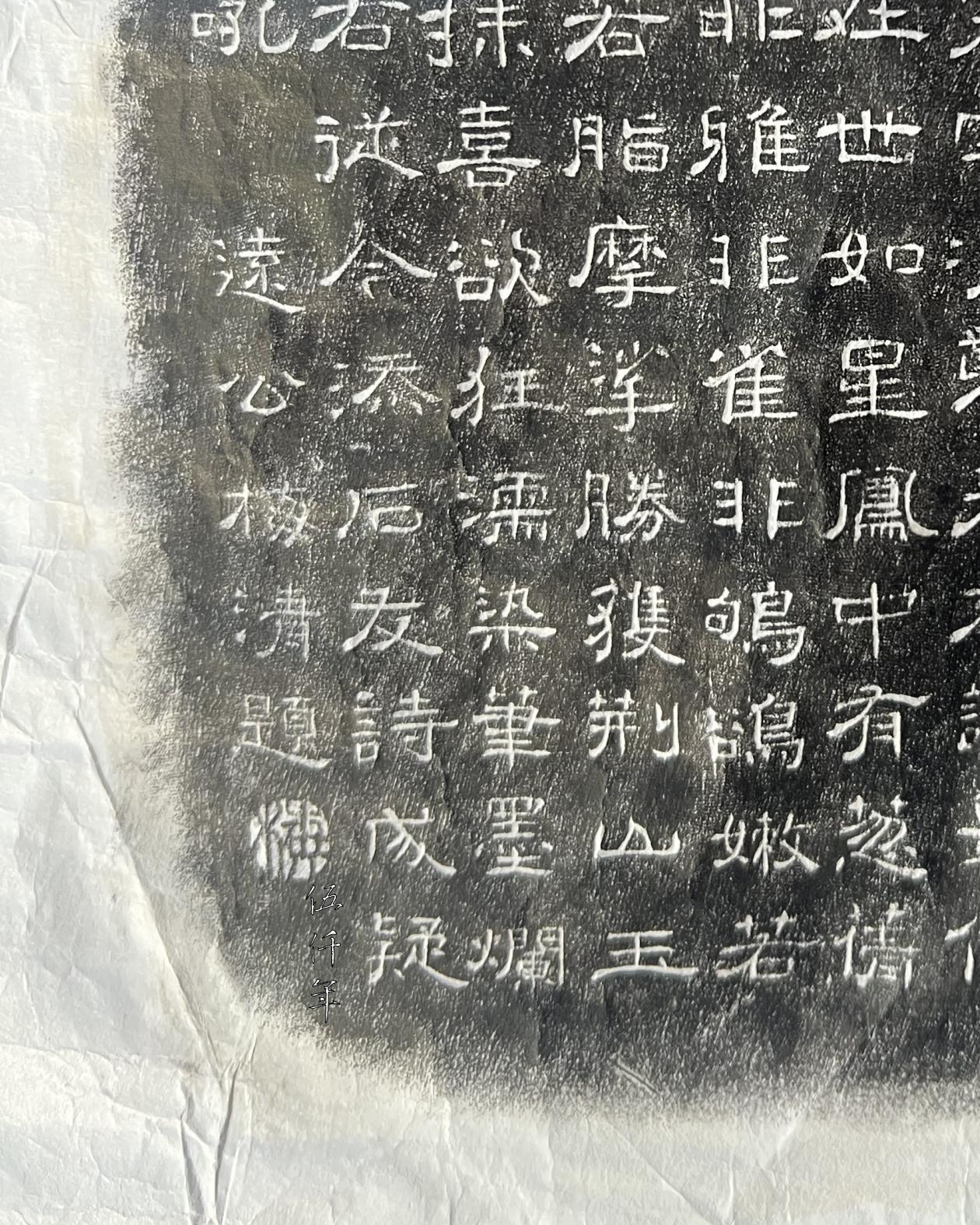

Ink rubbing of detail of calligraphy inscription by Huang Tsung-yen

Detail of calligraphy inscription by Huang Tsung-yen

Ink rubbing of detail of calligraphy inscription by Huang Tsung-yen

Huang Tsung-yen incised a few lines in clerical script at the bottom, the words are:

“In kuei-wei (癸未) year of the Ch’ung-chen reign,

Chung-yen (宗炎) carved this for Mr. Ho-chien (鶴澗)

at White Cloud Manor (白雲莊).”

Two personal seals were incised: “Huang (黃)”, “Hui-mu (晦木)”

One collector’s seal was incised: “Treasure of Yüan-kung (遠公珍玩)”. Yüan-kung (遠公) was the hao of Mei Ch’ing (梅清).

Portait of Huang Tsung-hsi

In late Ming, The Three Huang of Eastern Chekiang Province were renowned throughout the country. They are Huang Tsung-hsi (黃宗羲), hao Li-chou (梨洲), born in 1610 and died in 1695; the younger brother Huang Tsung-yen (黃宗炎), hao Hui-mu (晦木), born in 1616 and died in 1686; and cousin Huang Tsung-hui (黃宗會), hao Tse-wang (澤望), born in 1618 and died in 1663. They were natives of Yü-yao of Chekiang province. Huang Tsun-su (黃尊素), the father of Huang Tsung-hsi and Huang Tsung-yen, attained the chin-shih (進士) degree in the 44th year of the Wan-li reign, 1616. He was known to be a man of integrity, in his position of imperial censor, he impeached the powerful eunuch Wei Chung-hsien (魏忠賢). He was later framed and died in jail. The Three Huang all studied under the eminent Confucian scholar Liu Tsung-chou (劉宗周), born in 1578 and died in 1645, a native of Shan-yin in Chekiang province.

Huang Tsung-yen, tzu Li-hsi (立谿), hao Hui-mu (晦木), changed his hao to Che-ku (鷓鴣) after the fall of Ming dynasty. Che-ku is the name of Chinese francolin, a bird known to habitually fly southward. This is an allusion to his loyalty to the southern court of the Ming emperor. He was popularly called Mr. Che-ku. He attained the hsiu-ts’ai (秀才) degree in the 9th year of the Ch’ung-chen reign, 1636, and was an acknowledged expert on the I-Ching, also known as The Book of Changes. His works include Chou-I hsiang-tz’u in Thirty One Volumes (周易象詞), Hsün-men yü-lun in Two Volumes (尋門餘論), and T’u-shu pien-huo in One Volume (圖書辨惑). Ch’üan Tsu-wang (全祖望) wrote The Obituary of Mr. Che-ku, recording in detail his life story. Some passages are extracted here.

The first passage:

“In the Battle of Hua-chiang, Tsung-yen and his elder brother Tsung-hsi gathered all the male workers in their households, supplied them with spears to form a militia, and the females in the household were tasked to cook. They marched to Hao-pa to greet the Regent. Elder brother Tsung-hsi then travelled south to Hai-ch’ang, while Tsung-yen stayed in K’an-shan to deal with logistics. Their militia was known as the Forever Loyal Militia. After their defeat, Tsung-yen fled into Ssu-ming Mountain along the footpaths and boulders. He joined Minister Feng as his aide-de-camp, and travelled frequently among the garrisons.”

This passage depicts a military campaign directed by Huang Tsung-hsi and Huang Tsung-yen in the 1st year of the Lung-wu reign, or the 2nd year of the Shun-chih reign according to the Ch’ing dynasty, which corresponds to 1645, one year after the suicide of Emperor Ch’ung-chen. The brothers escaped after their defeat by the Ch’ing army. At the time, Huang Tsung-yen was thirty years old by Chinese reckoning.

The second passage:

“In keng-ying (庚寅) year, the Minister’s army was crushed. Tsung-yen was caught. The Minister’s wife was actually Tsung-yen’s mother-in-law, so he hid in her house first but was found. He ended on death row. His elder brother Tsung-hsi travelled to Yin County from the east, plotting to save his life. His old friend Feng Tao-chi (馮道濟), son of Feng Yeh-hsien (馮鄴仙), was indignant and volunteered to take charge. Kao Tan-chung (高旦中) was assigned with planning, while Fang Seng-mu (方僧木) wanted to appeal to the general’s headquarters. Tao-chi said: “Don’t do it, there must be a way to escape death.” On the day of his execution, Tsung-yen was taken out from his cell at nightfall, another death row inmate followed. After reaching the execution ground, the torch was suddenly extinguished, in the dark someone unknown rushed forward and carried Tsung-yen away. When the torch was reignited, they replaced Tsung-yen with another inmate. In the meantime, they had travelled ten miles in the night. They rested for a while, and eventually entered a chamber. It was a chamber in the White Cloud Manor that belonged to Wan T’ai (萬泰), also known as Wan Lü-an from the Ministry of Revenue. The person who carried Tsung-yen was Wan Ssu-ch’eng (萬斯程), son of Wan T’ai. All the Ming loyalists in Yin County gathered to untie Tsung-yen, and drank together to celebrate and reassure his startled soul.”

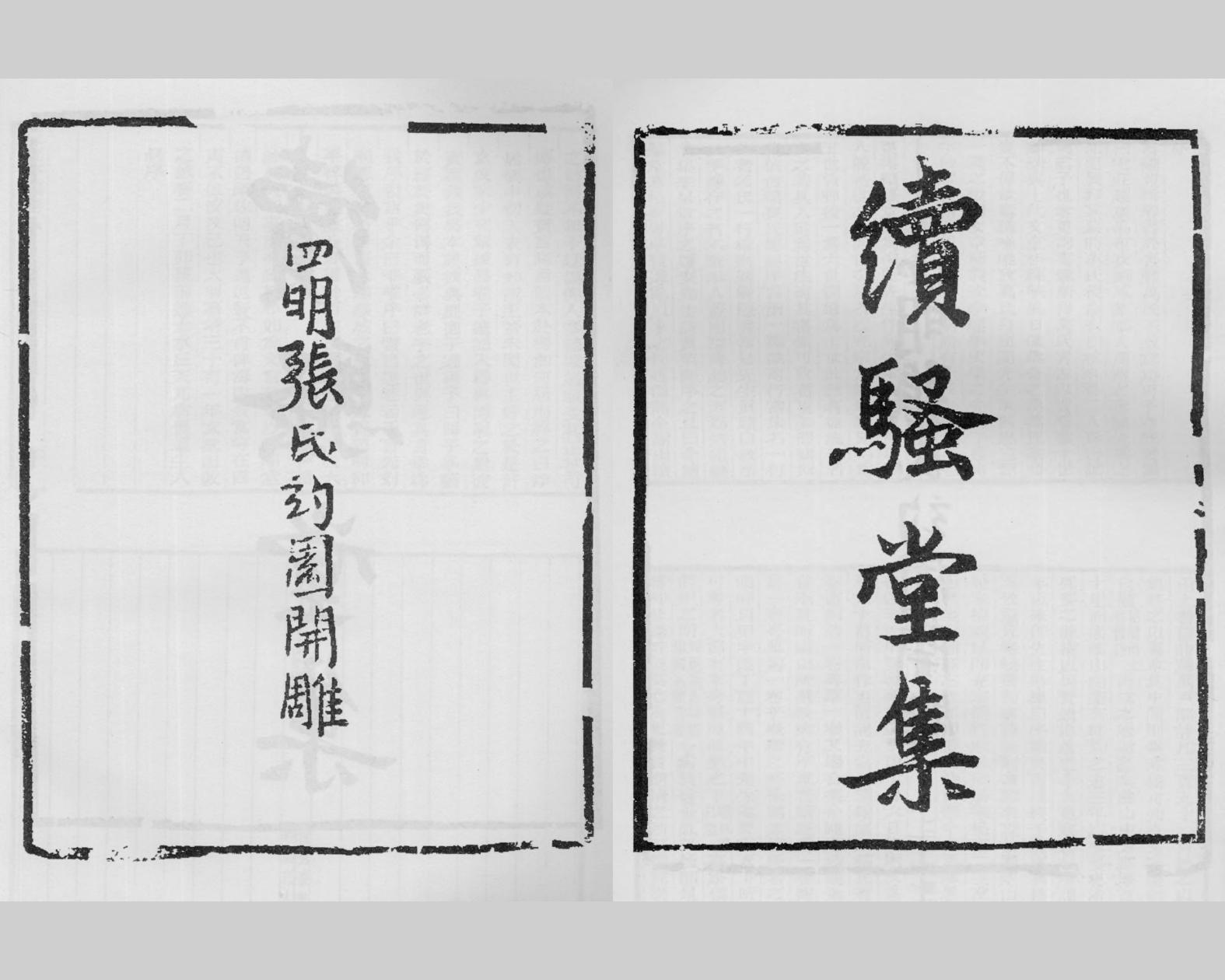

Title page of Hsü-sao T’ang Chi by Wan T’ai

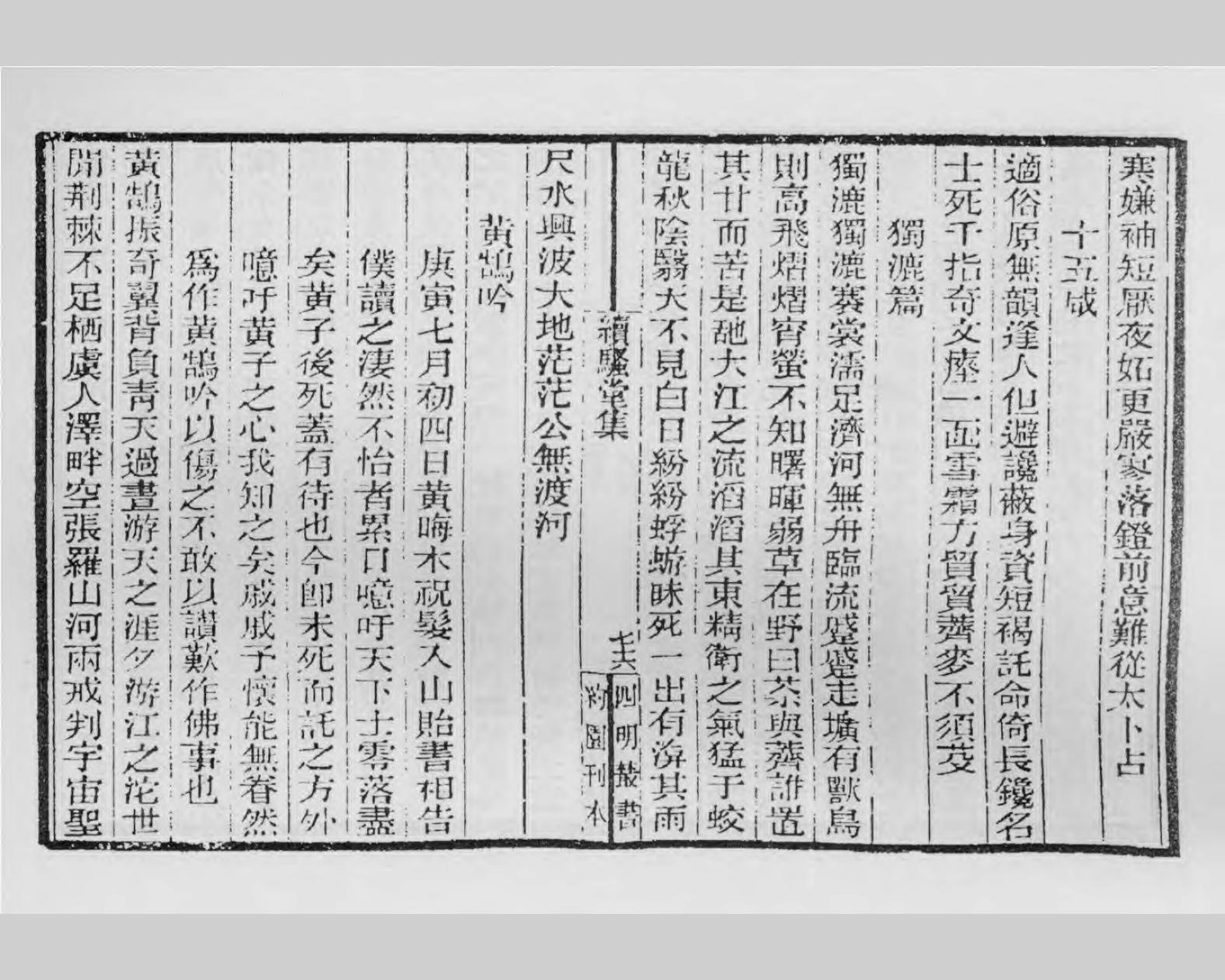

Inside pages of Hsü-sao T’ang Chi by Wan T’ai

Inside pages of Hsü-sao T’ang Chi by Wan T’ai

This passage depicts the demise of the army of Feng Chin-ti (馮京第) in the 4th year of the Yung-li reign, or the 7th year of the Shun-chih reign according to the Ch’ing dynasty, which corresponds to 1650. Huang Tsung-yen was arrested and put on death row at the age of thirty five. His elder brother Huang Tsung-hsi, friends Feng Tao-chi, Kao Tan-chung and Fang Seng-mu plotted a daring scheme to seize Huang Tsung-yen, substituting him with another death row inmate, and escaping into the night. Wan Ssu-chen, son of the Ming loyalist Wan T’ai, carried Huang Tsung-yen on his back, and ran all the way to White Cloud Manor, estate of his father. Wan T’ai, also known as Wan Lü-an (萬履安), was an intimate friend of both Huang Tsung-hsi and Huang Tsung-yen. Prince Lu (魯王) at one time appointed Wan T’ai director of the Ministry of Revenue. Wan T’ai used White Cloud Manor for studying, which was located at Kuan-chiang-an Village in the western side of Ning-po City. Later on Huang Tsung-hsi also used White Cloud Manor for teaching. Wan T’ai had eight sons, Wan Ssu-tung (萬斯同) being one, who was lauded for his work History of the Ming Dynasty. All the sons studied under Huang Tsung-hsi, who chronicled his friendship with Wan T’ai in A Record of Friendships (思舊錄). In Wan Tai’s own anthology Hsü-sao T’ang Chi (續騷堂集), there are nine poems dedicated to Huang Tsung-yen, an indication of the depth of their friendships. One of the poems, also the last poem in the anthology, is titled Huang-hu yin (黃鵠吟), its epigraph says:

“On 4 July in ken-yin (庚寅) year, Huang Tsung-yen set foot into the mountains and became a monk. He wrote to tell me, and I was depressed for days. Alas ! Men of honour have all fallen in this world! Tsung-yen is not dead because he still has expectations. Now even though he is alive, he has offered himself to a monastic life. Alas! This heart of Tsung-yen, I know this heart!”

The year keng-yin is the 4th year of the Yung-li reign, corresponding to the 7th year of the Shun-chih reign, or 1650, six years after the martyrdom of Emperor Ch’ung-chen.

In 1934, the educationist Yang Chü-t’ing located the ruin of White Cloud Manor. The Historic Manuscript Committee of Yin County proceeded to rebuild the White Cloud Manor, completing the building in 1935. This is a photograph of the exterior taken at the time

The last passage:

“In ping-shen (丙申) year, Tsung-yen was captured again. His elder brother Tsung-hsi sighed: “He will certainly die!” His old friends Chu Chan-hou (朱湛侯) and Chu Ya-liu (諸雅六) succeeded in saving him. However Tsung-yen lost everything along the way. Afterwards, he made a living as a medical doctor, traveling between Hai-ch’ang and Shih-men. When this was not enough to make a living, he applied his knowledge of ancient seal script to engrave stone seals. When this was again not enough, he emulated the brushworks of Li Ssu-hsün (李思訓 651-716 AD) and Chao Po-chü (趙伯駒 1120-1182) to paint. When even this was not enough, he carved inkstones. His works were all priced for sale, he was known to have made a living from his artistic endeavours.”

This passage depicts the capture of Huang Tsung-yen in the 10th year of the Yung-li reign, or the 13th year of the Shun-chih reign according to the Ch’ing dynasty, which corresponds to 1656, twelfth year after the suicide of Emperor Ch’ung-chen. He was captured at the age of forty one and bribed his way to freedom. He then became totally impoverished. He made a living first as a medical doctor, then a seal engraver, then a painter, lastly an inkstone carver. This inkstone was carved by Huang Tsung-yen when he was a young man.

The inscription by Huang Tsung-yen at the back of this inkstone is dated kuei-wei (癸未) year, corresponding to the 16th year of the Ch’ung-chen reign, or 1643, one year before the suicide of Emperor Ch’ung-chen. Huang Tsung-yen was twenty eight years old and residing at White Cloud Manor at the time. Seven years later, he fled for his life and sought refuge in the same manor.

Huang Tsung-yen offered this inkstone as a gift to Mr. Ho-chien (鶴澗). Who is Ho-chien? It is hard to identify. Since ancient time, there have been innumerable men and women with the same tzu or hao who live in the same era. We may conjecture, but cannot be certain. Searching through the Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Artists, there are two artists who used the hao of Ho-chien. One is Chiang Shih-chieh (姜實節), one is Chang Hung (張宏). Chiang Shih-chieh was born in 1647, so he could not be considered. Chang Hung was born in 1577 and passed away after 1652. If we calculate Chang Hung’s age at the time of the gift, he would be sixty seven years old, then long an eminent artist.

Chang Hung, tzu Chün-tu (君度), hao Ho-chien, native of Su-chou in Kiangsu province. According to Supplement to A Treasured Catalogue of Paintings (圖繪寶鑑續纂) by Han Ang (韓昂) of Ming dynasty, it says:

“(Chang Hung) was proficient in painting landscape. His brushwork is comparable to that of the ancients. The hills and valleys are different and full of spirit, they are layered like a screen, and painted in the manner of the Yuan masters. The surface of the stone is cracked and three dimensional, the trees defuse the aura of scholarly establishment. For his spontaneous brushwork of portraits, the facial expressions are fitting, when there are many, they are properly dispersed. His work New Year Day in Su-chou was compellingly realistic, no one can rival him.”

According to A Record of Selected Paintings of the Ch’ing Dynasty (國朝畫徵錄) by Chang Keng (張庚), it says:

“(Chang Hung) was accomplished in landscape painting. His work is rustic, robust, graceful and elegant. It is desolate and faraway. Scholars in Su-chou all respect him. I have seen some of his works, such as Fisherman Playing a Lute, Pine and Cypress in Spring, and they are equal to the works of the Yuan masters.”

Ho-chien is perhaps the hao of Chang Hung, and perhaps not. It cannot be verified.

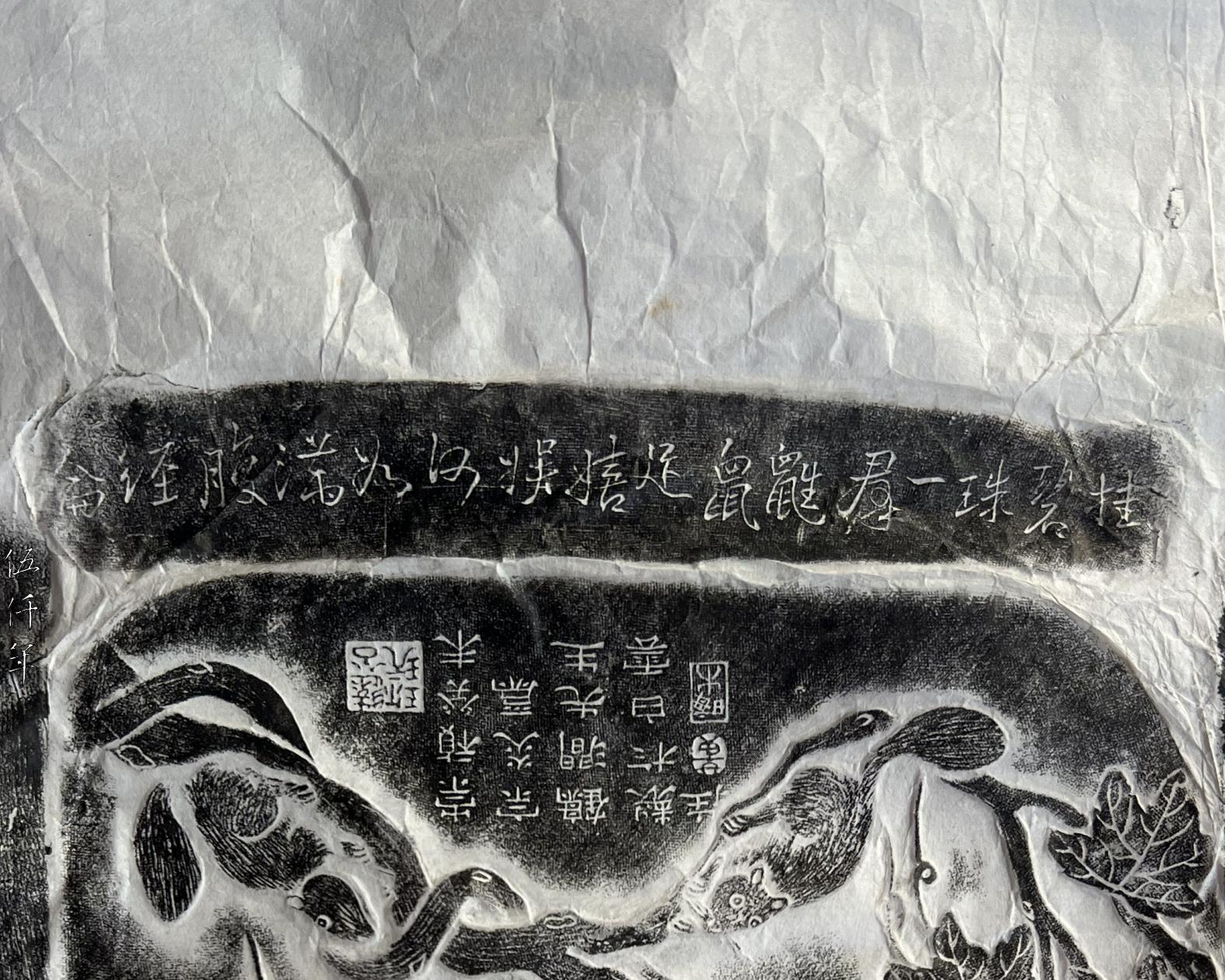

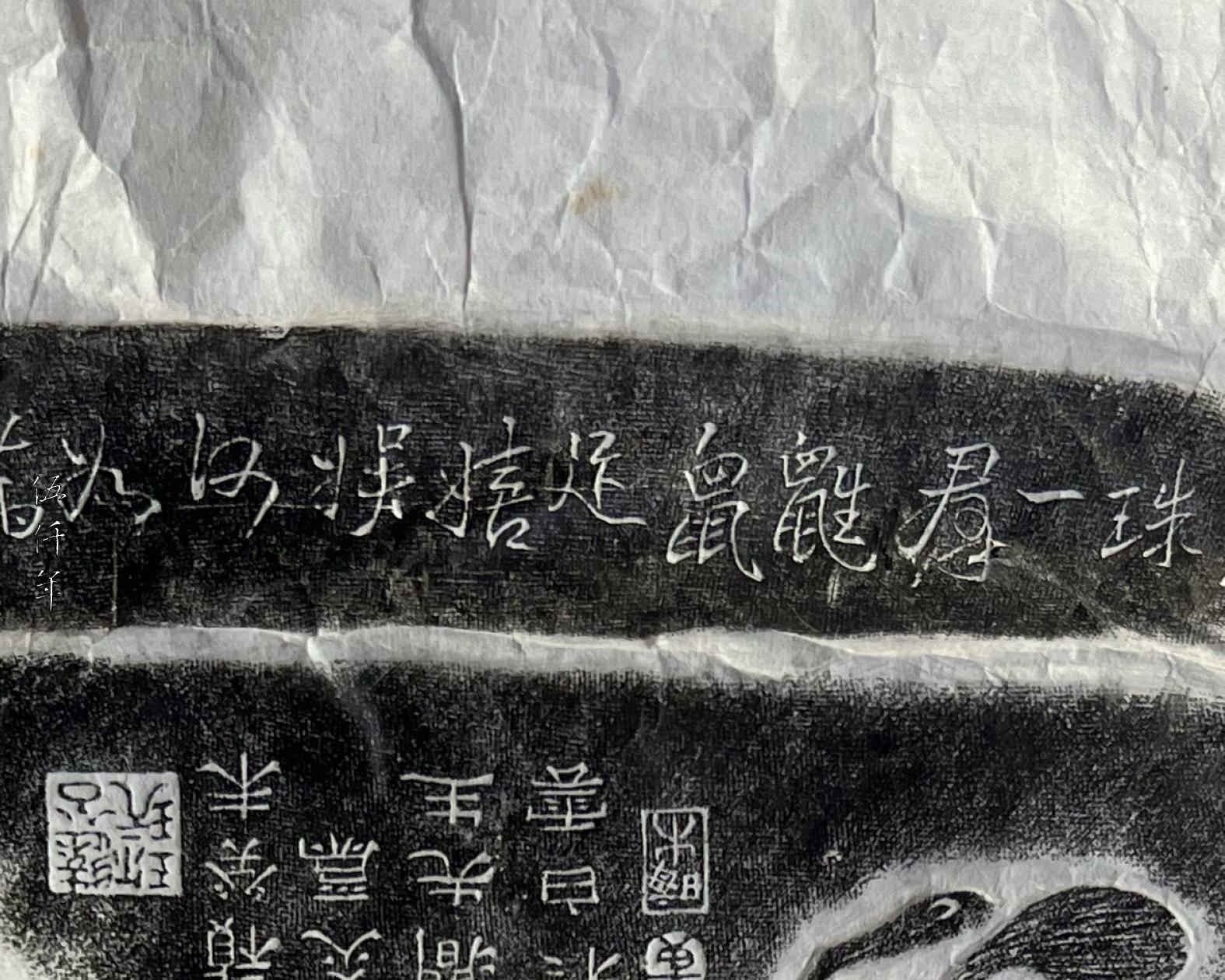

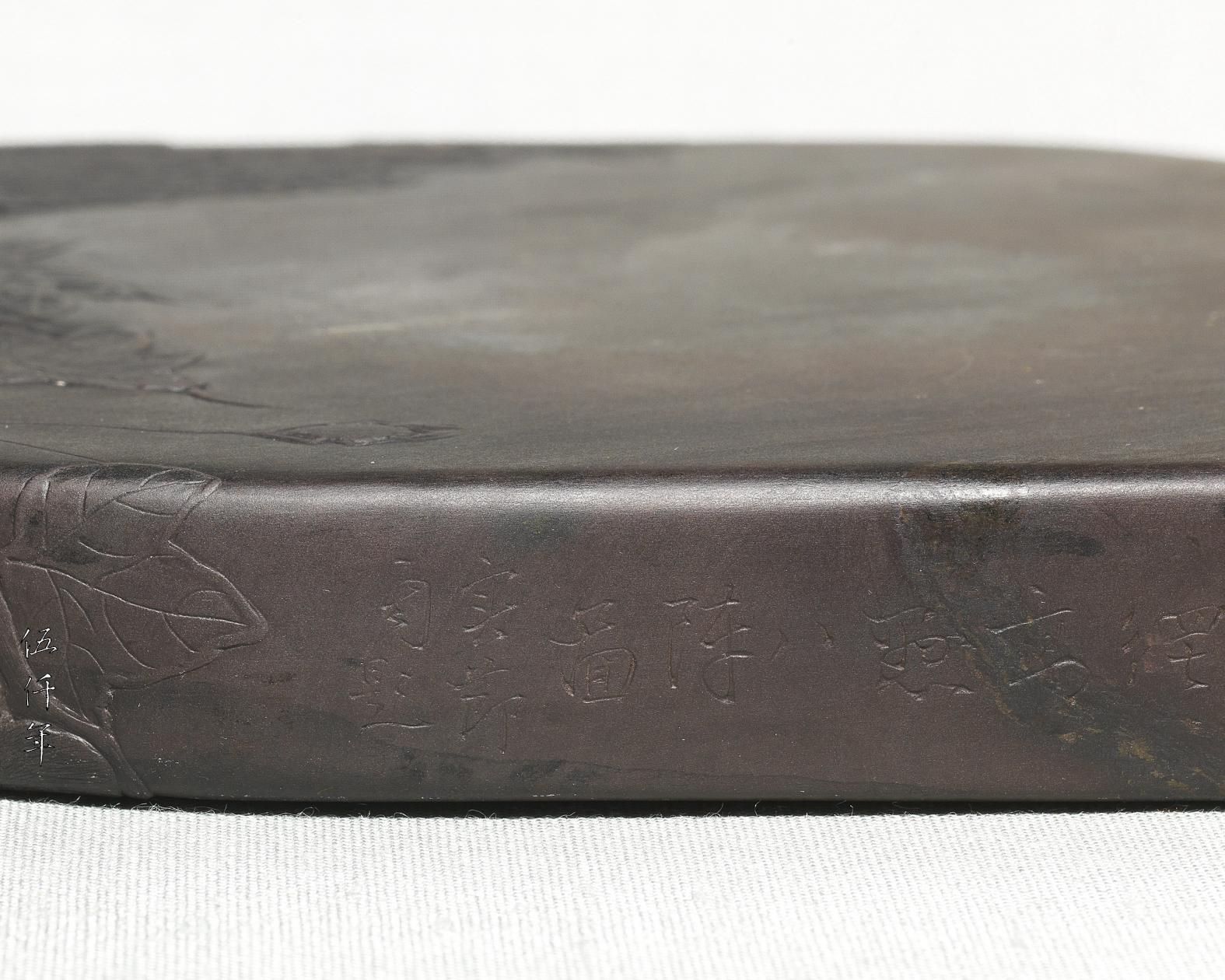

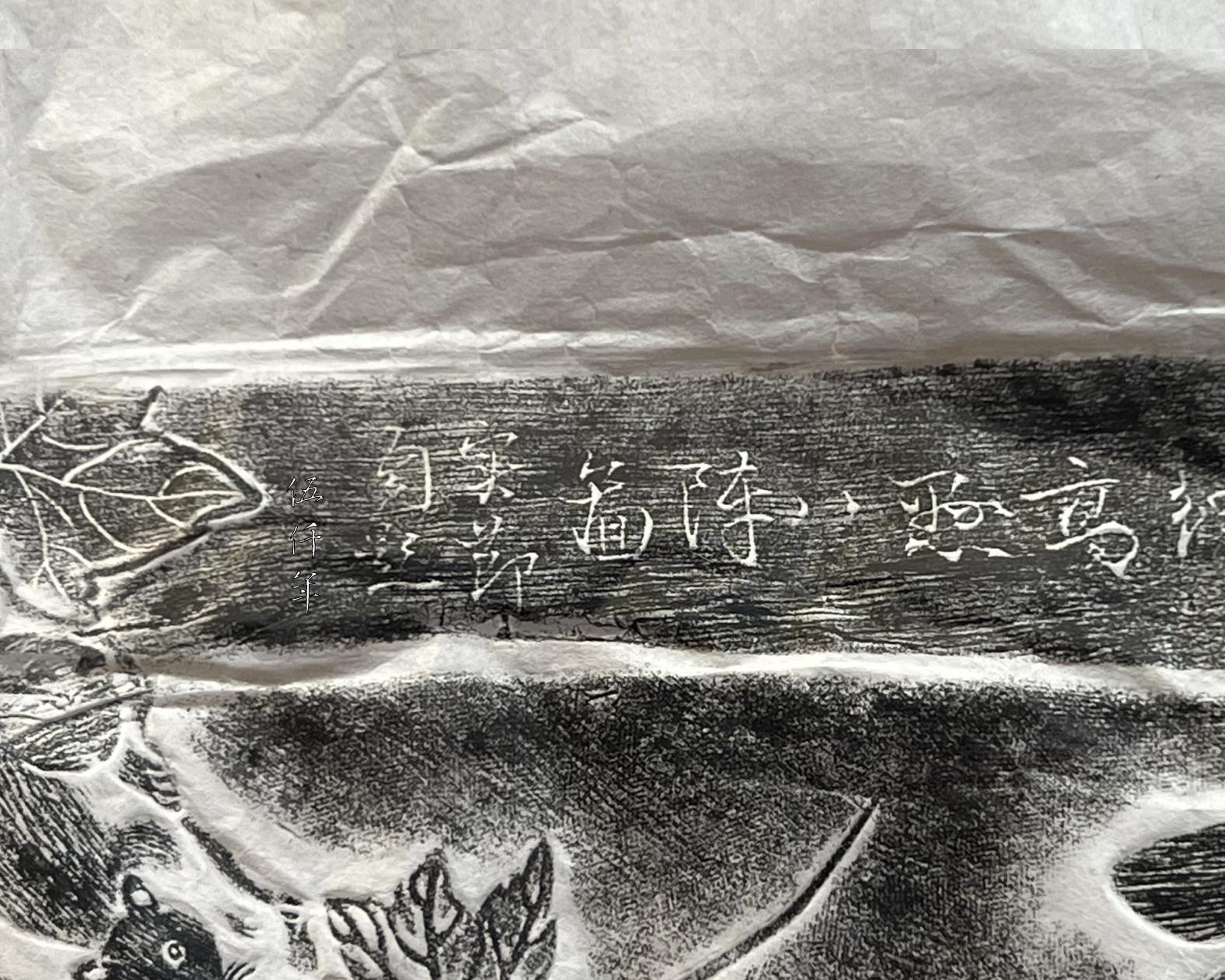

First side of inkstone with poem and calligraphy by Chiang Shih-chieh

Ink rubbing of first side of inkstone

Detail of first side of instone

Ink rubbing of detail of first side of inkstone

Second side of inkstone with poem and calligraphy by Chiang Shih-chieh

Ink rubbing of second side of inkstone

Detail of second side of inkstone

Ink rubbing of detail of second side of inkstone

Third side of inkstone with poem and calligraphy by Chiang Shih-chieh

Ink rubbing of third side of inkstone

Detail of third side of inkstone

Ink rubbing of detail of third side of inkstone

Fourth side of instone showing leaves and branches

Ink rubbing of fourth side of inkstone

Detail of fourth side of inkstone

Inkrubbing of detail of fourth side of inkstone

Chiang Shih-chieh carved a seven character poem in running script around the side walls of the inkstone. The poem reads:

“Grapes hanging like jade beads,

Squirrels in groups scurry pertly.

Why tuck such scholarship away?

Spider’s web holding the Eight Battle Plot.

Inscribed by Shih-chieh.”

Chiang Shih-chieh, born in 1647 and died in 1709, tzu Hsüeh-tsai (學在), hao also Ho-chien (鶴澗), native of Lai-yang in Shantung province, but he lived in Su-chou of Kiangsu province. He was proficient in poetry, calligraphy and painting. His work was titled Fen-yü-ts’ao (焚餘草). His father Chiang Ts’ai (姜埰), a Ming loyalist, was born in 1607 and died in 1673. He attained the chin-shih degree in the 4th year of the Ch’ung-chen reign, 1631. He offended the emperor with his words and was banished to Hsüan-chou in Anhwei province. After the fall of Ming dynasty, he never received an edict from the emperor to permit him to return home. He swore to stay in the land of banishment and ordered his children to bury him in Hsüan-chou. Huang Tsung-hsi greatly endorsed the loyalty and resolve of Chiang Ts’ai, and commented:

“In February of chia-shen (甲申) year (corresponding to the 17th year of the Ch’ung-chen reign, 1644), Chiang Ts’ai was banished to guard Hsüan-chou. In less than a month capital Peking was sacked. He did not wish to ignore the emperor’s command, and despite the disintegration of the Ming dynasty, he refused to return home and was buried by a pavilion named the Pavilion of Respect.

The educated gentleman says: This can be called the utmost Jen (仁 compassion), and the greatest I (義 righteousness). When the country falls and the emperor dies, right and wrong, honour and humiliation, are like dreams of yesterday. Mr. Chiang was stubborn and did not adapt. From the view of ordinary people, all without exception believed he was pedantic. Let us consider this under the concept of I: The court did not issue any edict to retract the penalty of banishment. For an official to initiate his own return, can this be called compliance? Thus, for Chiang Ts’ai to die in the land of banishment, this is the only way. For him to be buried in the land of banishment, maybe it is not mandatory. However, under the concept of I, this is the only way. Those from the past did not act carelessly…..For Mr. Chiang to be buried in Hsüan-ch’eng, he finally completed his mission to guard the city. This is the meaning of ‘greatest I’.”

Chiang Ts’ai was a contemporary of the brothers Huang Tsung-hsi and Huang Tsung-yen, his son Chiang Shih-chieh belonged to the next generation. On the front and back of this inkstone, eight squirrels were altogether carved. Shih-chieh was most likely inspired by the number eight, his last line is: “Spider’s web holding the Eight Battle Plot.” Eight Battle Plot (八陣圖) is of course a reference to the spider’s web, but it also alludes to a famed military formation invented by Chu-ko liang (諸葛亮 181-234 AD). By making such a military and historic reference, Shih-chieh was implicitly advocating the continuation of military struggle against Ch’ing dynasty. It is not known when Shih-chieh made this inscription. One may conjecture that it was made decades after Huang Tsung-yen’s carving of the inkstone in 1643. By then the Ch’ing dynasty was firmly established. Perusing the hao of Ho-chien that was carved on the inkstone, a hao identical to his own, Shih-chieh might be ever more inundated by a deep sense of history and loss when inscribing this poem.

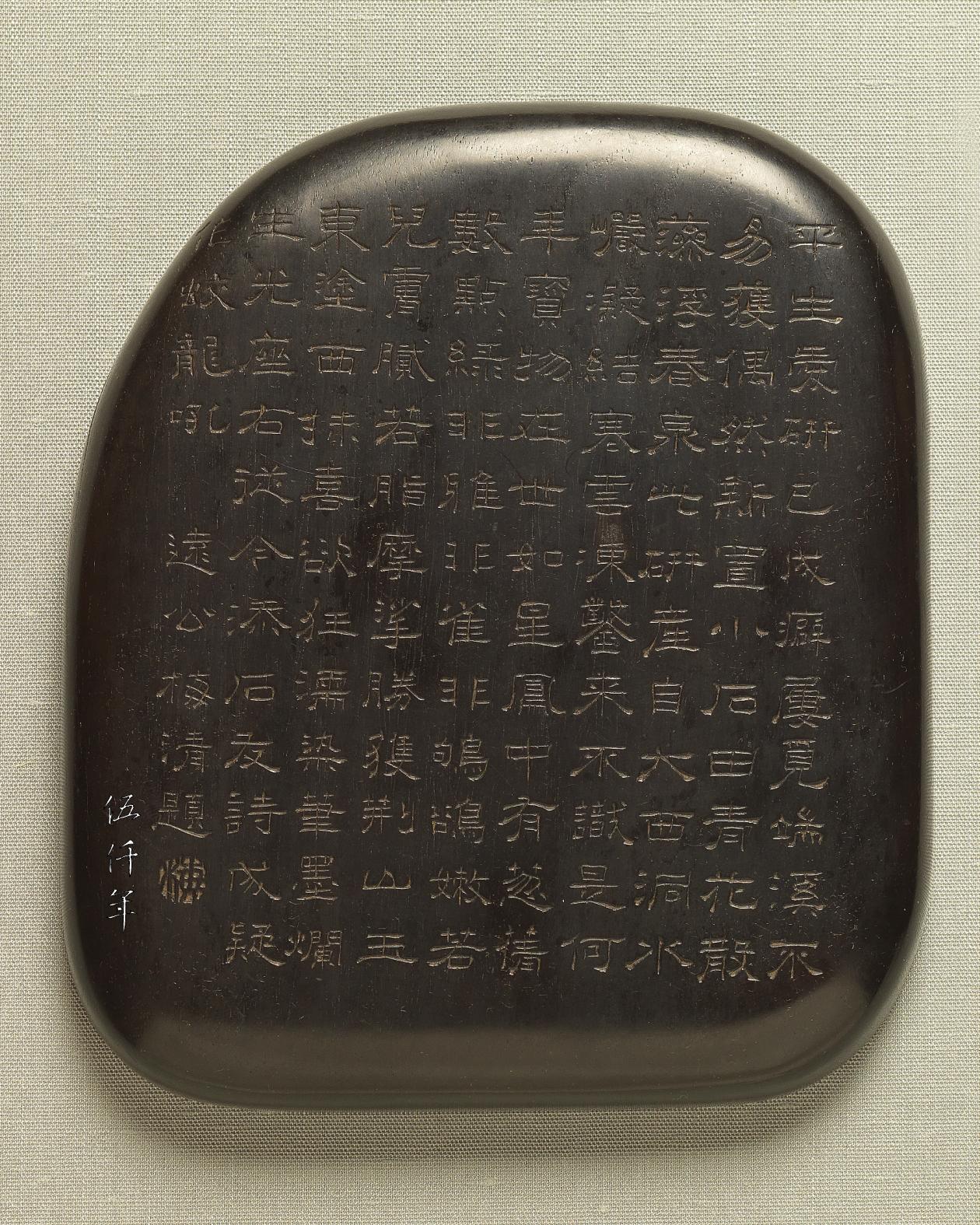

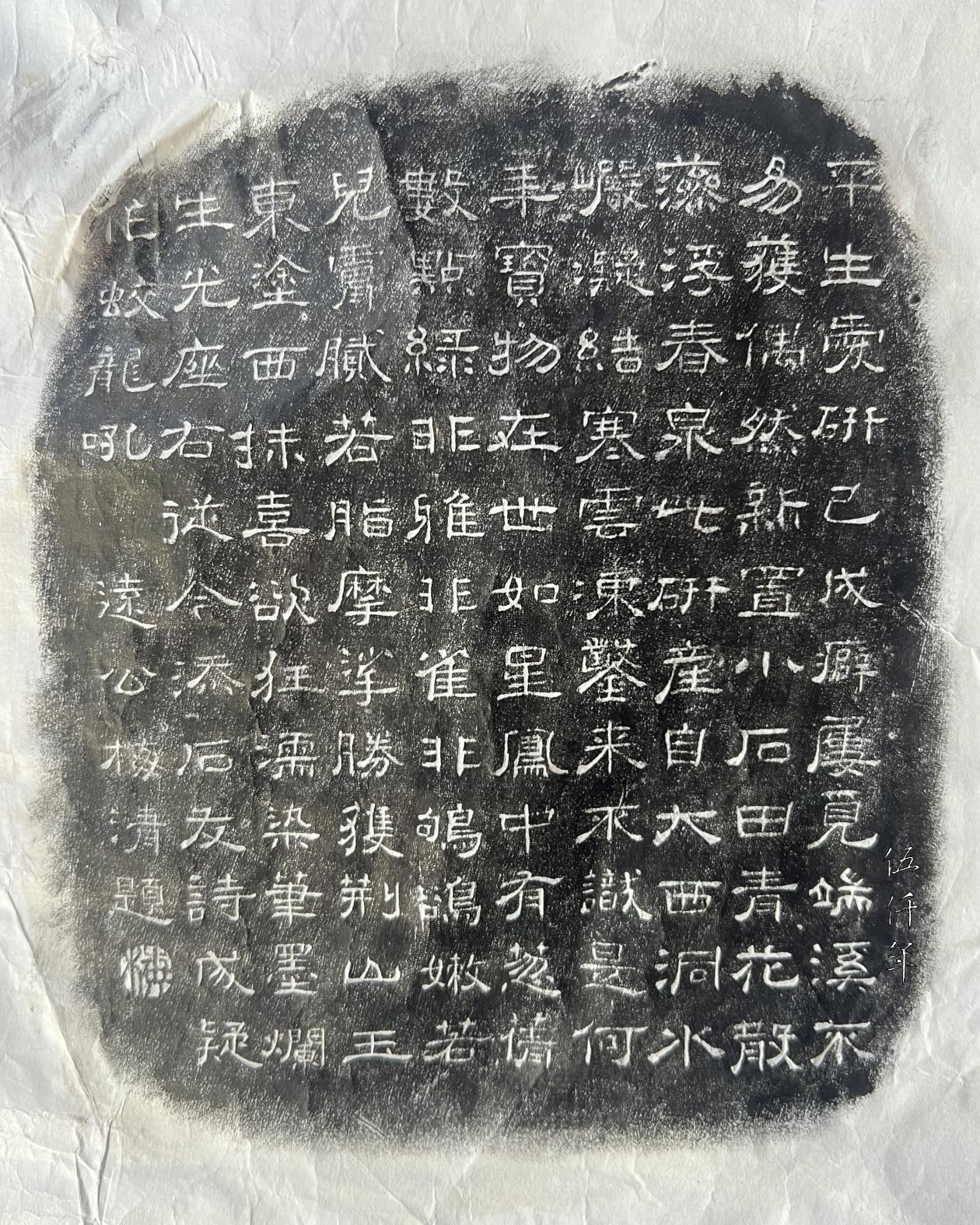

Front of box showing engraved calligraphy by Mei Ch’ing

Inkrubbing of front of box showing engraved calligraphy by Mei Ch’ing

Lower left of box front showing engraved signature of Mei Ch’ing

Inkrubbing of lower left of box front showing engraved signature of Mei Ch’ing

Base of box

When Mei Ch’ing acquired this inkstone, he was ecstatic. He used clerical script calligraphy to write a poem composed of seven word sentences, and engraved it on the box cover. The poem reads:

“An addict of inkstones I have become,

Searching for Tuan stone to no avail.

By chance I acquired a tiny plot of stone,

Green flowers float like springs in spring.

This stone comes from Great Western Cave,

Hill water crammed and frosty cloud chilled.

What distant year was the chiseled stone made?

Material scarce like comet and phoenix.

In the middle some speckles of green,

Not crow, not sparrow, not mynah.

Soft like child skin and rich like fat,

Caressing it to forsake Ching-shan jade.

Writing here sketching there in wild rapture,

Ink soaked brush to shine and glow.

From now a new stone friend by my side,

Poem once done the dragon seems to roar.

Inscribed by Yüan-kung, Mei Ch’ing.”

Personal seal incised: “Mei”

Mei Ch’ing, born in 1623 and died in 1697, tzu Yüan-kung (遠公), hao Ch’ü-shan (瞿山), native of Hsüan-ch’eng in Anhwei province. He excelled in painting. His literary works include Poetry from T’ien-yen Pavilion in Two Volumes, Poetry of Ch’ü-shan, and Poetry of Mei Family. In the Draft History of Ch’ing, his biography reads:

“Mei Ch’ing, tzu Ch’u-shan, native of Hsüan-ch’eng, descendant of Mei Yao-ch’en (梅堯臣) from the Sung dynasty. He was distinct, tall, handsome and open minded. He was self motivated and was known for his erudition and refinement. He attained the chü-jen (舉人) degree in the 11th year of the Shun-chih reign, but he failed to attain any position at the Ministry of Rites. The officials at court fought to befriend him, such as Wang Shih-chen (王士禎), Hsü Yüan-wen (徐元文), who particularly admired him. His style of poetry changed a few times, and he compiled them into Poetry from T’ien-yen Pavilion in Two Volumes. When he reached the age above seventy, he published Poetry from Ch’u-shan. His calligraphy emulated the style of Yen Chen-ching (顏真卿 709-785 AD) and Yang Ning-shih (楊凝式 873-954 AD). His painting is expansive and individualistic. He once painted a picture titled Mount Huang, which was a complete expression of the ever changing sceneries of mountains and clouds. It was very much cherished by his contemporaries.”

This inkstone carved by Huang Tsung-yen bears witness to two generations of literary friendships and devotions in late Ming and early Ch’ing. Huang Tsung-yen presented the inkstone as a gift to his friend, at that time he was residing at White Cloud Manor, property of his intimate friend Wan T’ai. A few years later, he sought refuge at the manor to save his own life. His contemporary Mei Ch’ing and the younger Chiang Shih-chieh, inscribed two poems on the box cover and the inkstone respectively. The poem by Mei Ch’ing is a synopsis of connoisseurship, discussing the material and quality of the inkstone, as well as his personal passion. The poem by Chiang Shih-chieh even adopted the ideological tone of his father Chiang Ts’ai, that of a a Ming loyalist. Although the year Shih-chieh was born, the emperor had already committed suicide three years earlier.

Today, Emperor Ch’ung-chen had passed away for more than three hundred and eighty years. The glory of Ming dynasty has been completely entrusted to the legacy of martyrs and loyalists. Old traces are faraway, human and government affairs have become mostly peripheral, except for the memory of the righteous spirit that once filled their world. Lying in swamps of blood, dwelling in deserted caves, enduring hunger and cold, weeping for the Ming capital, suffering illnesses and handicaps, bearing the ravages of old age, all the scourges of adversity cannot swerve their cause. A chance encounter of an inkstone, unexpectedly reveals that the Ming so dearly guarded by past martyrs and loyalists, has long been transformed into hallowed light that drizzled into the true hearts of men and women.

Top right detail of inkstone front, showing squirrels and grapes around and spider the water reservoir