Summer heat will soon be here. The intensity of the sun scorches the skin. Electricity prices in many countries have continued to rise. Air conditioning can no longer be easily enjoyed at all times by everyone. If women and men today each uses a fan, not only does it help cooling, it especially fits into the urgent cause of protecting the environment. Moreover, the refined lifestyle of our ancestors can return once more to the world. Is it not be a beautiful thing? As we promote the lifestyle of the fan, we hereby present for your perusal a folding fan with calligraphy and painting by Yüan K’ei-wen (袁克文), which was formerly in the collection of the great fan collector Mr. Huang T’ien-ts’ai (黃天才).

Curatorial and Editorial Department

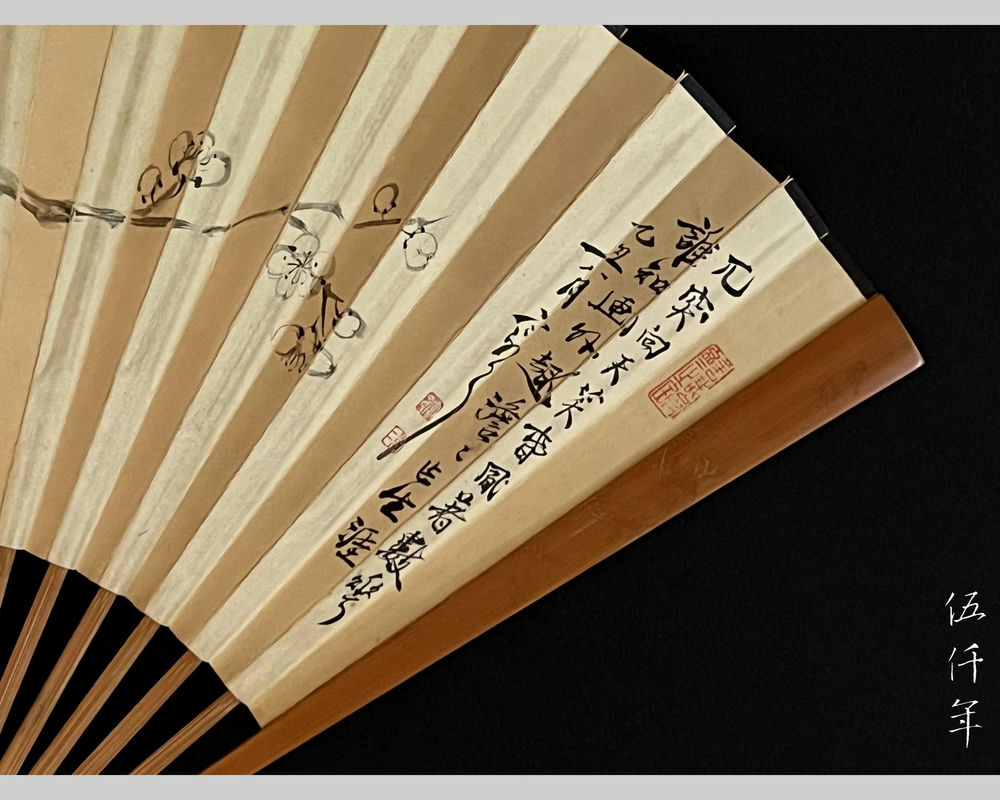

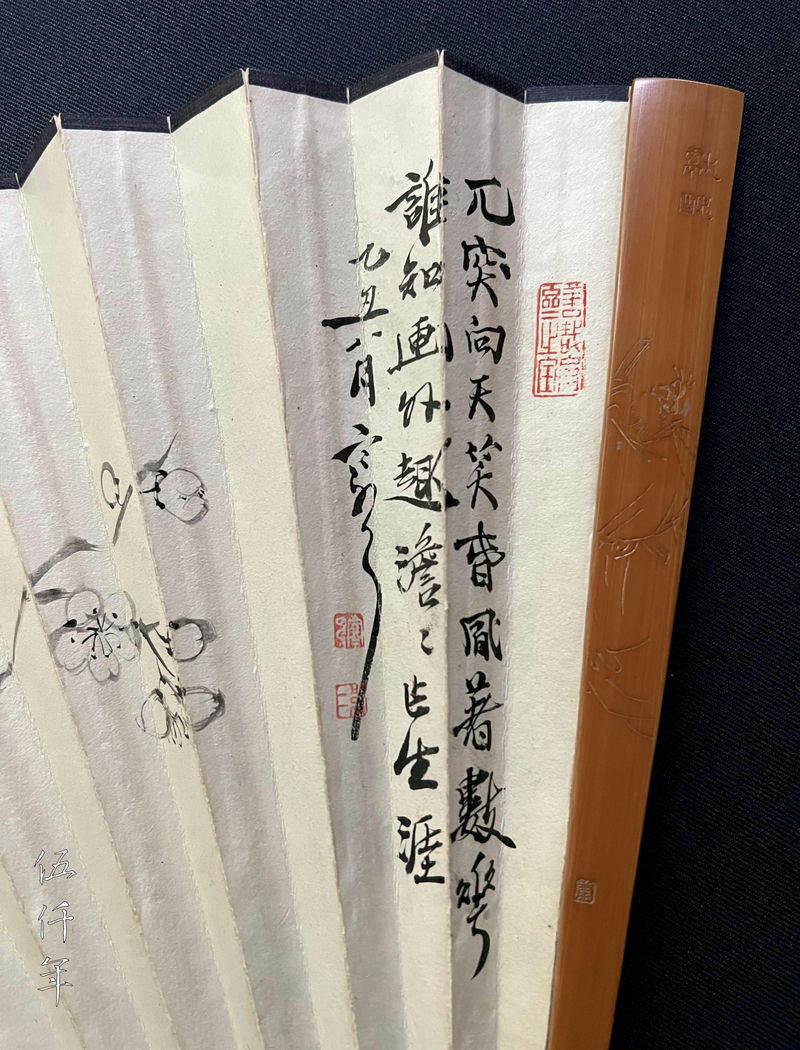

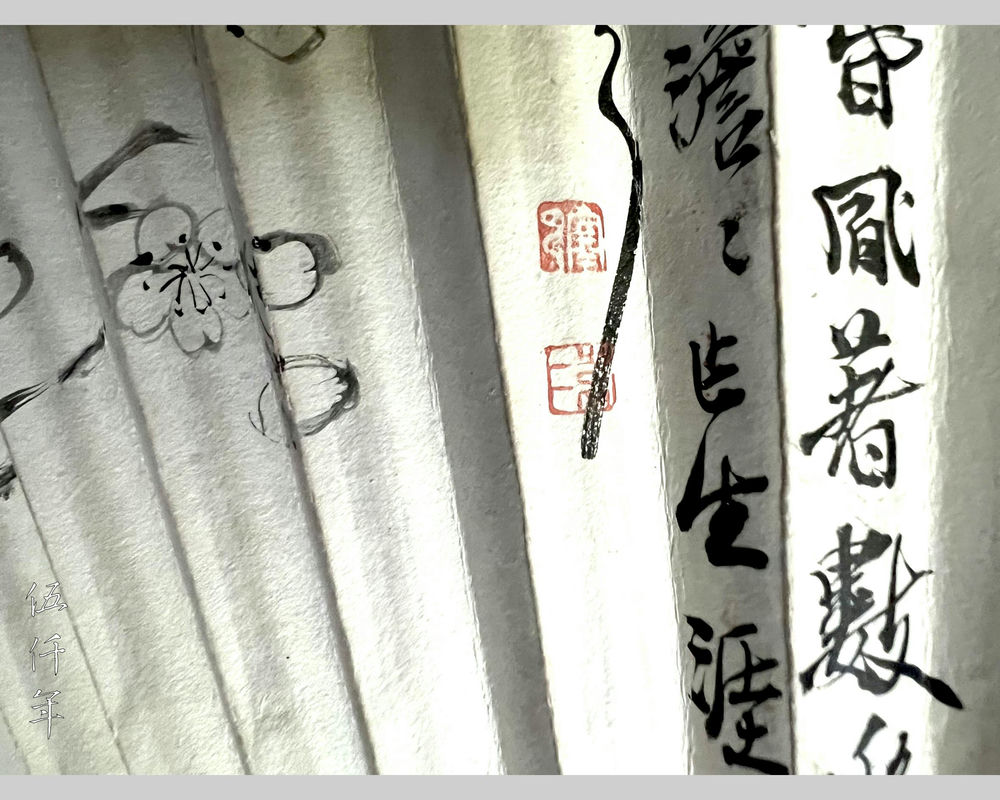

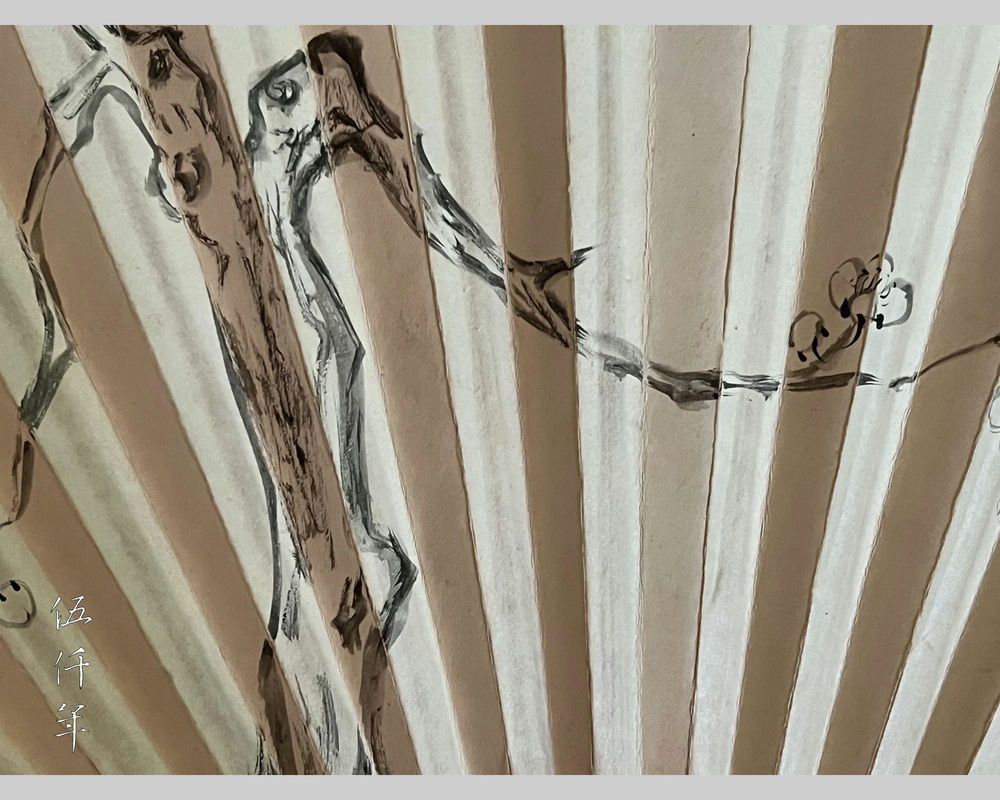

Calligraphic inscription besides the prunus painting on one side of the folding fan by Yüan K’ei-wen

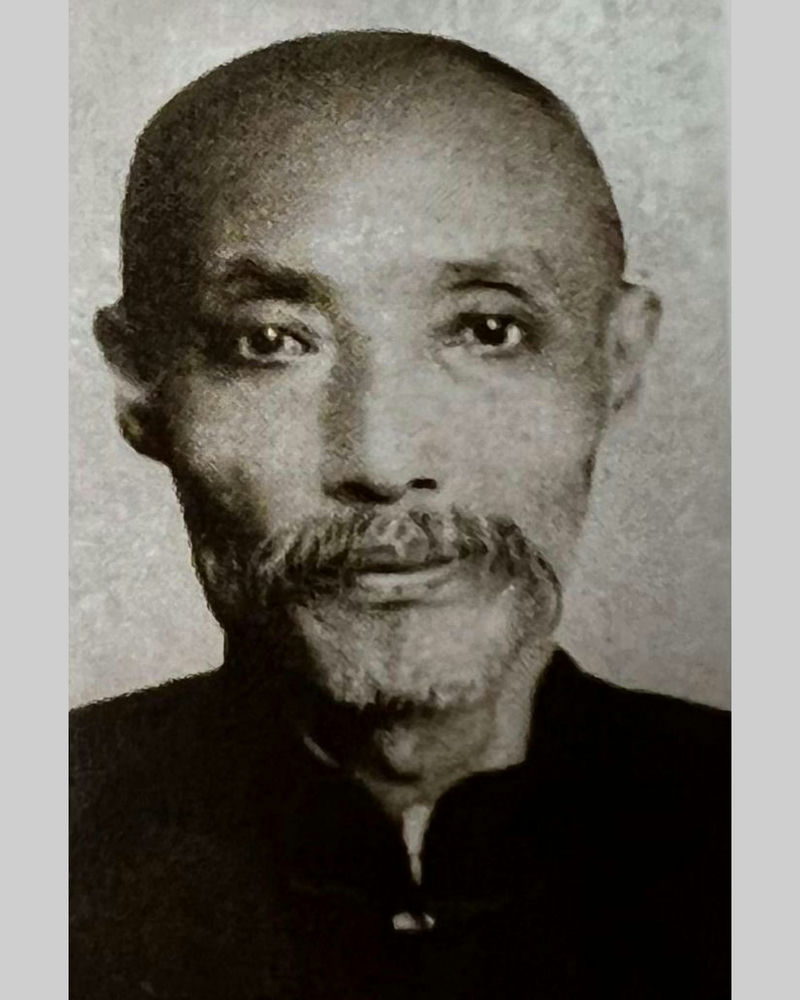

In the early years of the Republic of China, traditional culture inherited from the previous dynasty pervaded the whole country. There were innumerable scholarly, virtuous and talented individuals. Many were publicly admired by society and were bestowed the graceful title of ming-shih (名士). One of the famous ming-shih whose reputation spread from north to south was Yüan K’ei-wen (袁克文).

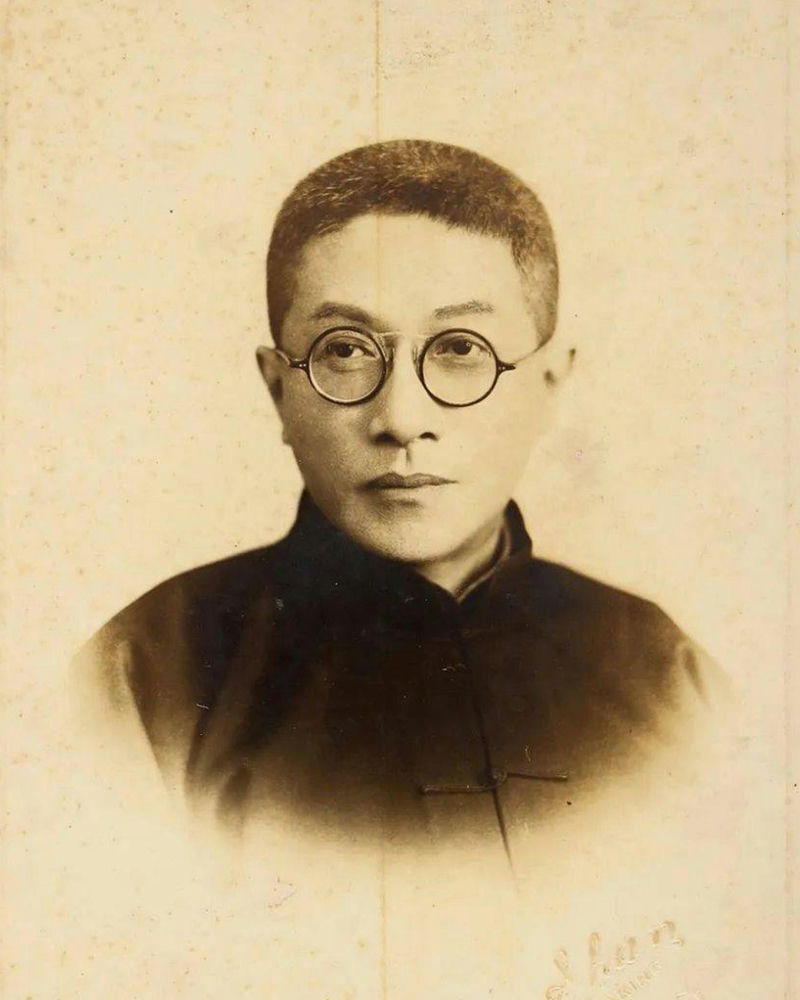

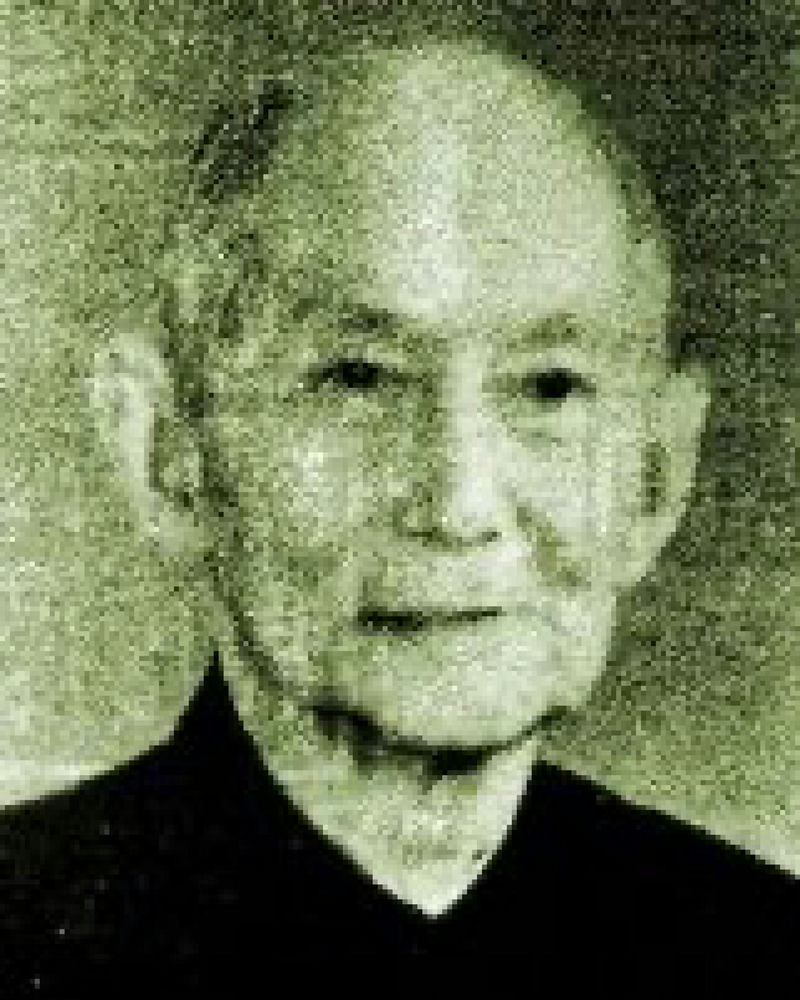

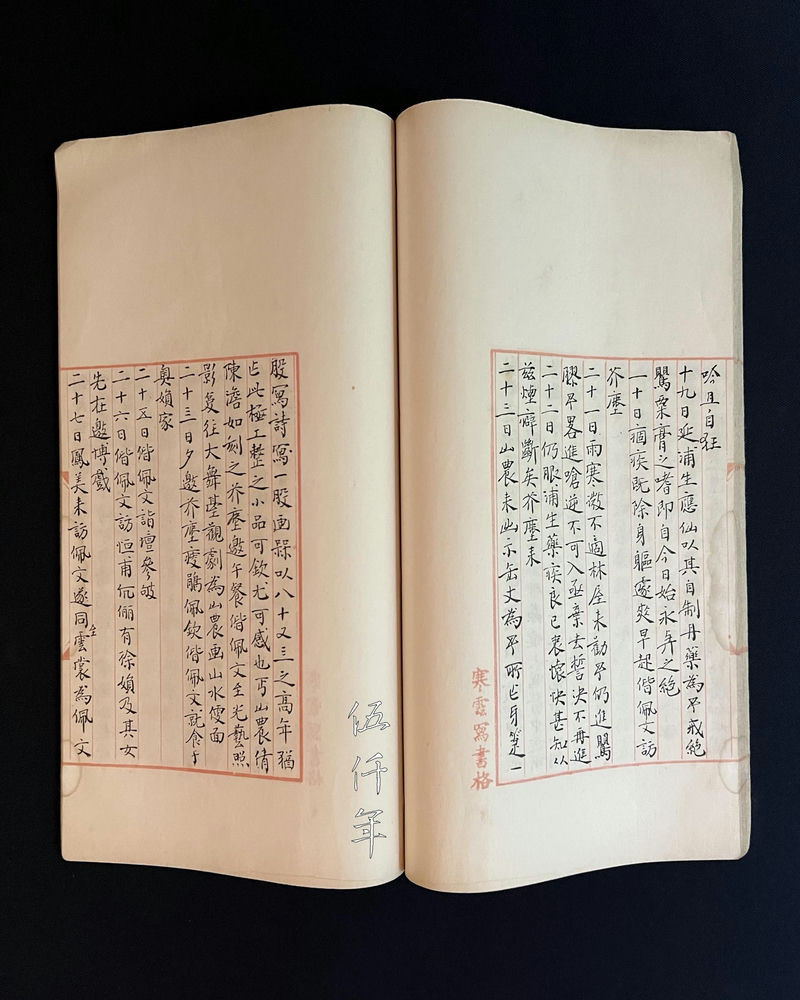

Portrait of Yüan K’ei-wen (袁克文)

The term ming-shih has been used since the Han dynasty, and its usage has a long history. As the original meaning has become vague, it requires some clarification.

K’ung Ying-ta (孔穎達 574-648 AD) of the Tang dynasty wrote in his commentary on The Book of Rites: The Monthly Ordinances (禮記、月令):

“Ming-shih is one whose moral character is upright and outstanding, whose understanding of the Way is profound, who will not be subservient to a monarch and who chooses to live in seclusion rather than hold office.”

Hou Fang-yü (侯方域 1618-1655) of the late Ming lived in a time of crisis and turbulence. He once wrote an essay titled On Factions (朋黨論). He believed in a concept of ming-shih that is more forceful and ambitious, describing such a person as one without office who can help the country in times of need. He wrote:

“There are stubbornly shameless ministers in the court, and then there are ming-shih who hold no official positions but rectify wrongdoings and uphold righteousness. Certainly in the court, when all the ministers who rectify wrongdoings and uphold righteousness have left or died, then those who hold no official positions will grow in resolution and strength with their opposition. This is a matter that concerns the destiny of the country as well as the moral culture of the country. … As for those ming-shih who hold no official positions, they are from all over the country and may not know each other. Some may hear of their reputation and admire them, some may mourn their rectitude and lament them, some may meet them in person and succumb to approbation, some may share the joy of righteousness and will not change course for material wealth and honours, some may share the ambition to cleanse the country with no regret for imprisonment. For their country, there is no position that they are unwilling to give up. For the righteous who are imprisoned, they stand by them without concern for past relationships and favours. They are only committed to preserving the moral code of society that should not be destroyed, to the differentiation of right and wrong that should not be dimmed. Therefore, within a thousand miles there may be one ming-shih, within a hundred miles there may be another ming-shih, they recommend and refer to each other from afar, until their bond of fellowship is unbreakable.”

The ancients had strict criteria for the definition of ming-shih but by the time of the early period of the Republic of China, the definition had become more relaxed. In modern times, anyone who possesses moral integrity, scholarship, literary ability, talent, a good reputation and an unworldly spirit can qualify as a ming-shih.

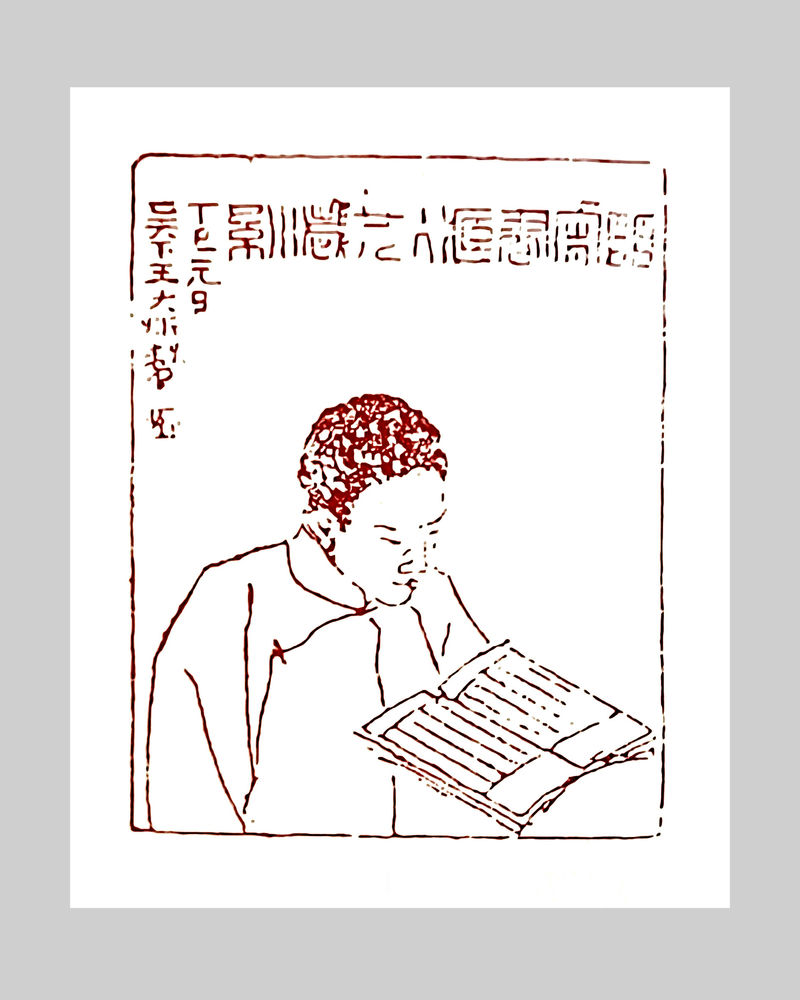

Seal impression of the portrait seal carved by Wang Ta-hsin (王大炘) dedicated to Yüan K’ei-wen

Yüan K’ei-wen (1889-1931), tzu Pao-ts’en (豹岑), Pao-ts’un (抱存), Pao-kung (抱公). He once acquired the painting Cold Clouds on the Shu Road (蜀道寒雲圖) by the Sung dynasty painter Wang Shen (王詵 1036-1093) and thereafter named his hao Han-yün (寒雲). This hao was later widely used. He also used other nom de plume such as Kuei-an (龜庵), San-ch’in-ch’ü Chai (三琴趣齋), Pa-ching Ko (八經閣), Yün-ho Lou (雲合樓), Hou-pai-sung-i-ch’an (後百宋一廛 After-pai-sung-i-ch’an). The great bibliophile of the Ch’ing dynasty Huang P’i-lieh (黃丕烈 1763-1825) had his library named Pai-sung-i-ch’an (百宋一廛), Yüan K’ei-wen therefore named his studio Hou-pai-sung-i-ch’an (後百宋一廛 After-pai-sung-i-ch’an), indicating with pride that his collection of one hundred sets of Sung dynasty books was no less impressive. Yüan K’ei-wen was a native of Hsiang-ch’eng, Honan Province. He was the second son of Yüan Shih-k’ai (袁世凱 1859-1916), his mother’s last name was Chin (金) and from a noble Korean family. His teacher was the “saint of calligraphy couplets” Fang Erh-ch’ien (方爾謙 1872-1936). Yüan K’ei-wen excelled in poetry and lyrics, calligraphy and painting, enjoyed K’un-ch’ü Opera (崑曲), was an expert and discerning collector of rare ancient books, epigraphs, coins and stamps. He wrote many works such as Han-yün’s Book Reflections (Han-yün-shu-ying 寒雲書影), Handwritten Summary of Twenty-nine Sets of Sung dynasty Books Collected by Han-yün (Han-yün-shou-hsieh-so-ts’ang-song-pen-t’i-yao-erh-shih-chiu-chung 寒雲手寫所藏宋本提要二十九種), Calligraphy on Coins (Ch’üan-chien 泉簡), Han-yün’s Diaries for the Years Ping-yin and Ting-mao (Han-yün-ping-yin-ting-mao-jih-chi 寒雲丙寅丁卯日記), Han-yün’s Collection of Poems (Han-yün-chi 寒雲集), T’ing-yün’s Collection of Poems (T’ing-yün-chi 停雲集) and others.

Although Yüan K’ei-wen was the son of Yüan Shih-k’ai, he did not agree with his father’s decision to re-establish a monarchy in the 5th year of the Republic of China (1916). He was widely admired for his untarnished integrity, and held as an example that those with scruples will not be swayed by personal gain.

In November of yi-mao year (乙卯 1915), while Yüan Shih-k’ai was in the heat of promoting the re-establishment of the monarchy, Yüan K’ei-wen published a poem titled Clarity (分明) expressing his stand in the Asiatic Daily (亞細亞日報) in Peking:

Clothed in thin cotton I try to endure,

Rain or clear into the hazy night.

Come back south winter goose and lonely moon,

Darkness is over Peking by eastward gale.

To keep the moment to vie a blink,

Urge on cricket chirps my midnight dreams.

Such pity such wind such rain on high,

Climb not all the way to the palace top.

I have a treasured folding fan with calligraphy and painting that was given as a gift by Yüan K’ei-wen to Shou Hsi (壽璽). It was previously in the collection of my late friend Mr. Huang T’ien-ts’ai (黃天才). Yüan K’ei-wen wrote two poems on one side, and painted a prunus trunk on the other side.

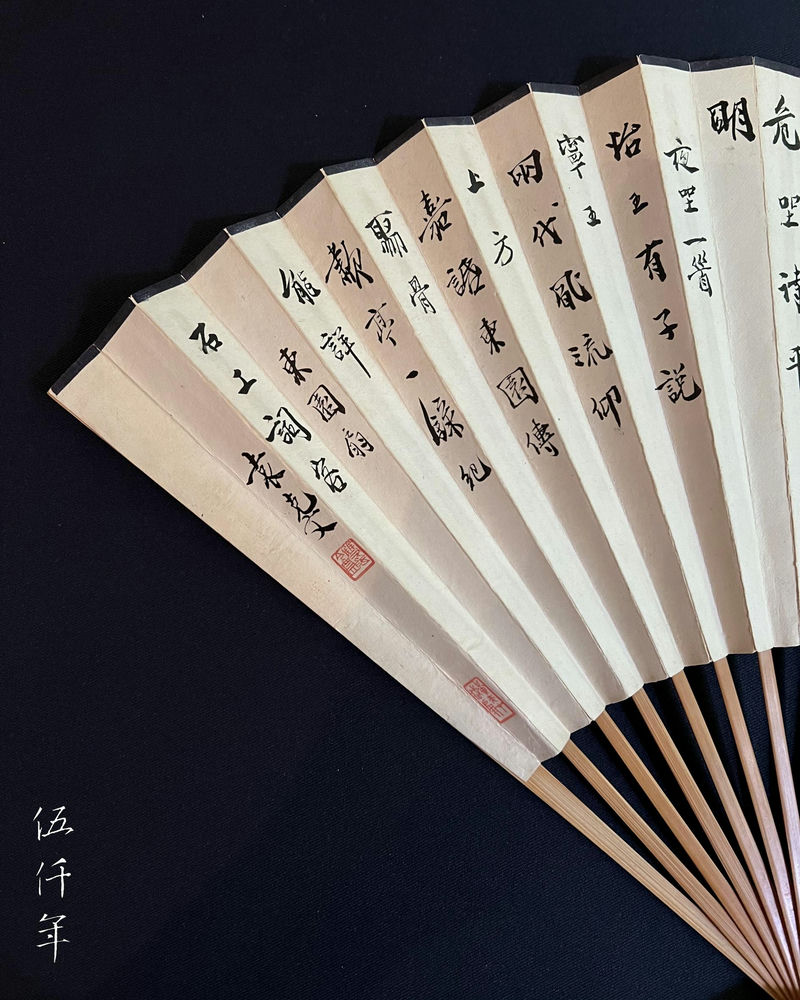

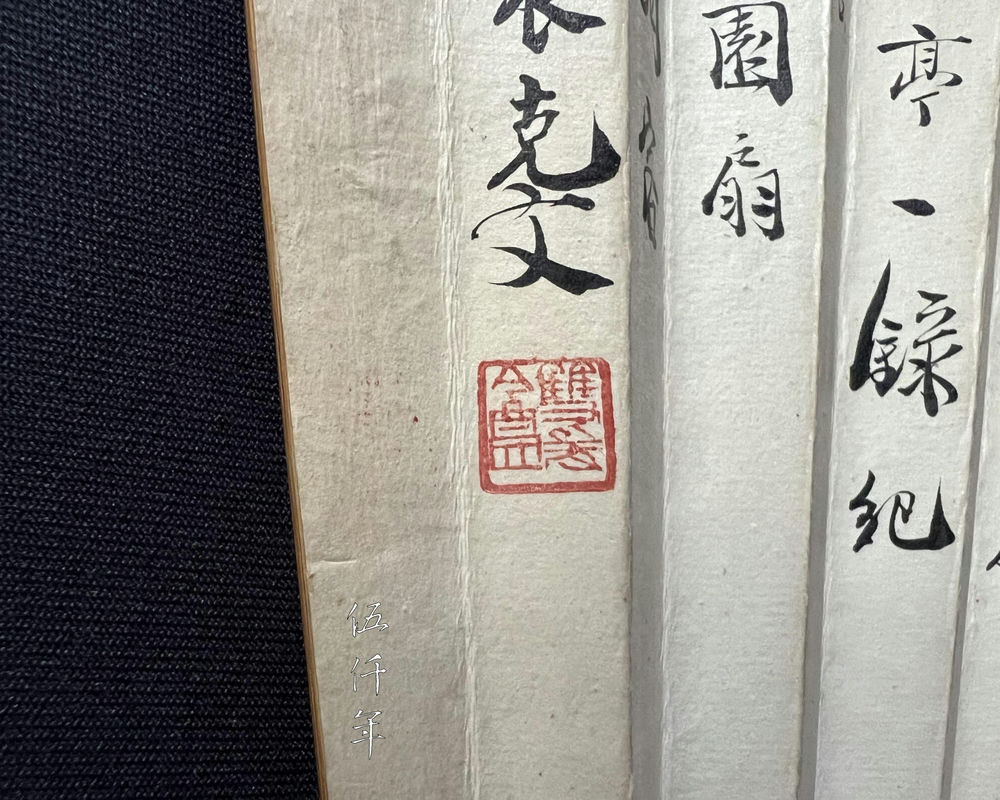

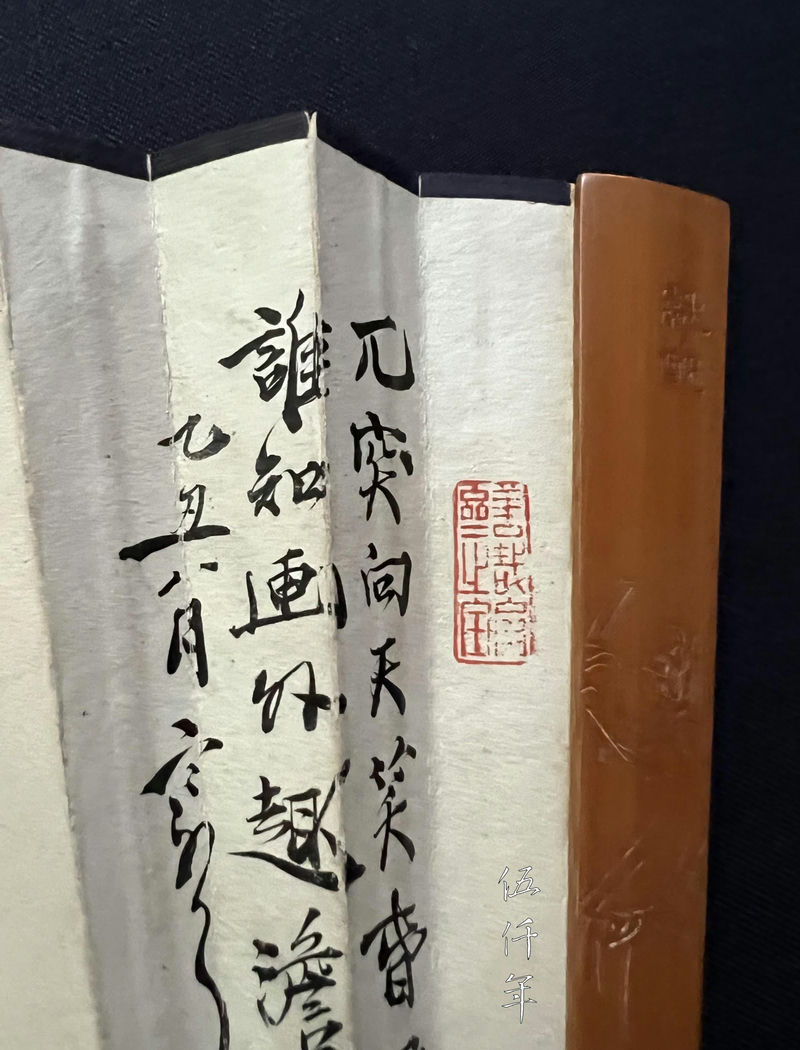

One side of the folding fan with calligraphy of two poems by Yüan K’ei-wen

First poem by Yüan K’ei-wen

Second poem by Yüan K’ei-wen

The fan face with two poems reads:

Rain comes with wind and thunder,

Sounds of ten thousand horses whirl.

Music has just sent off the drunks,

Grass and trees so like an army.

Shrills of solitary crane is heard,

Dim lights flicker with fireflies.

Whistling wind keeps me awake,

Writing poetry upright till dawn.

Sitting at Night

Prince I had a son who spoke of Prince Ning,

Two generations of virtuosities now looked up upon.

Delightful words in East Garden are passed down in a fan,

Details all recorded in Notes of Hsiao-t’ing Pavilion.

For East Garden Fan

Shih-kung the tz’u poet,

Yüan K’ei-wen.

Seal: Shuang-yüan An (雙爰盦)

Seal impression of Shuang-yüan An

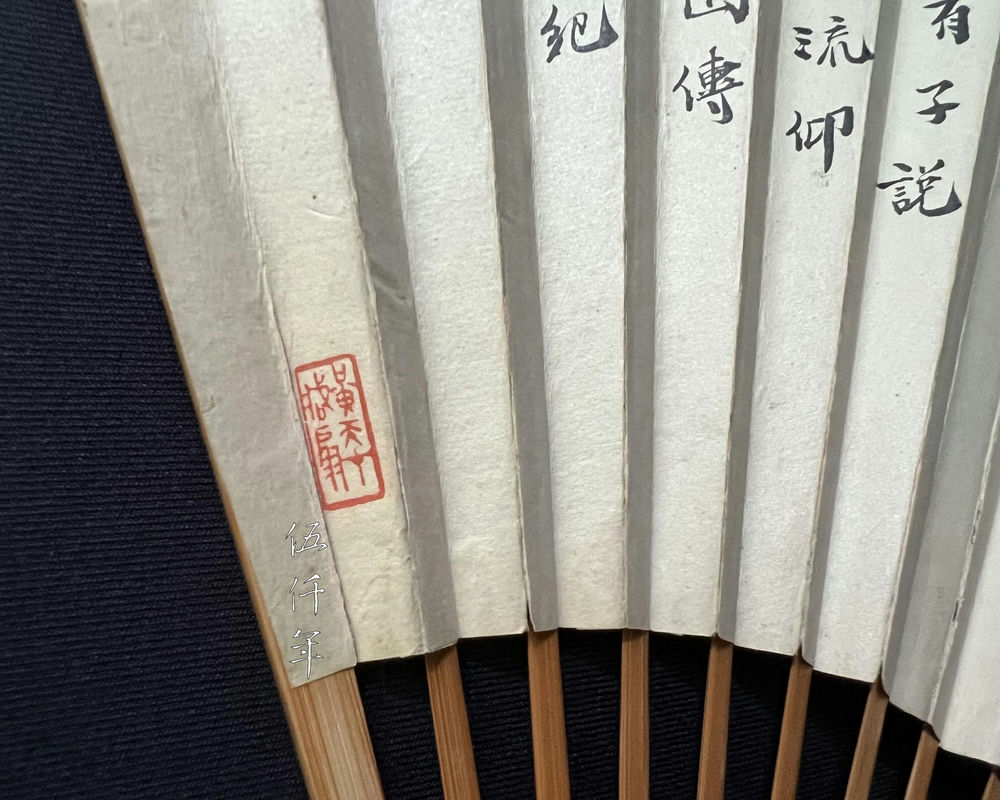

On the upper right corner is the collector’s seal: Treasure of Shan-tsai-shan Chai (善哉扇齋之寶)

On the lower left corner is the collector’s seal: Fan collected by Huang T’ien-ts’ai (黃天才藏扇)

Collector’s seals: On the upper right corner is the seal “Treasure of Shan-tsai-shan Chai (善哉扇齋之寶). On the lower left corner is the seal, “Fan collected by Huang T’ien-ts’ai” (黃天才藏扇).

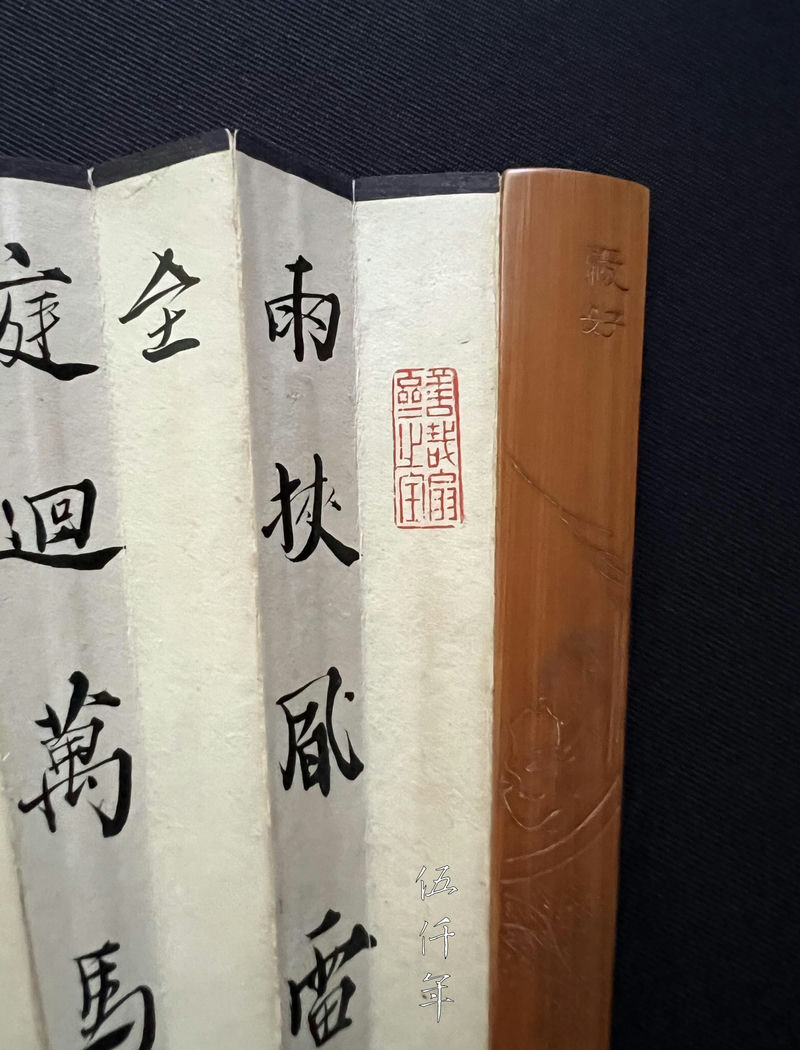

Other side of the folding fan with a painting of prunus by Yüan K’ei-wen

Painting of prunus trunk is accompanied by an inscribed poem

The fan face with a monochrome painting of prunus trunk is accompanied by an inscribed poem. It reads:

Standing tall laughing at heaven,

A few blossoms in spring breeze.

Who knows the joy beyond painting,

Lightly lightly carry this life.

I-ch’ou year (乙丑) August, Han-yün.

Seals: “Han-yün” (寒雲), “Yüan-erh” (袁二).

Seal impressions of “Han-yün” (寒雲) and “Yüan-erh” (袁二).

Collector’s seals: On the upper right corner is the seal “Treasure of Shan-tsai-shan Chai” (善哉扇齋之寶). On the lower left corner is the seal “Fan collected by Huang T’ien-ts’ai” (黃天才藏扇).

On the upper right corner is the seal “Treasure of Shan-tsai-shan Chai” (善哉扇齋之寶)

On the lower left corner is the seal “Fan collected by Huang T’ien-ts’ai” (黃天才藏扇)

The folding fan was made in i-ch’ou year, which is the 14th year of the Republic of China (1925), when Yüan K’ei-wen was thirty seven years old.

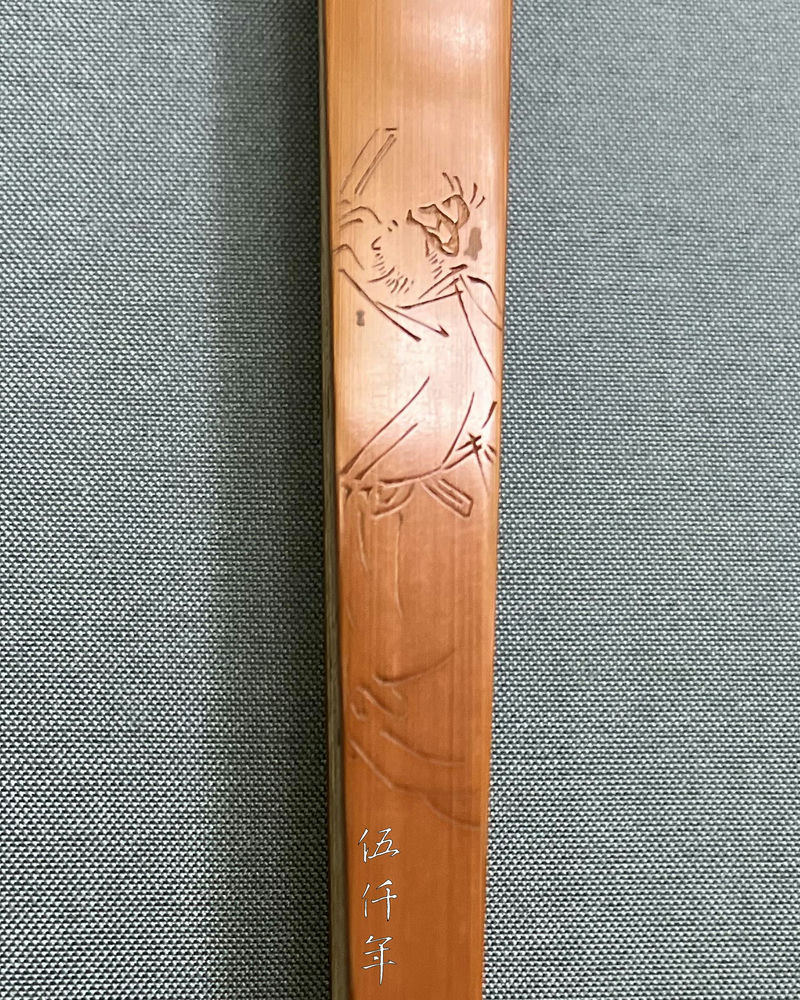

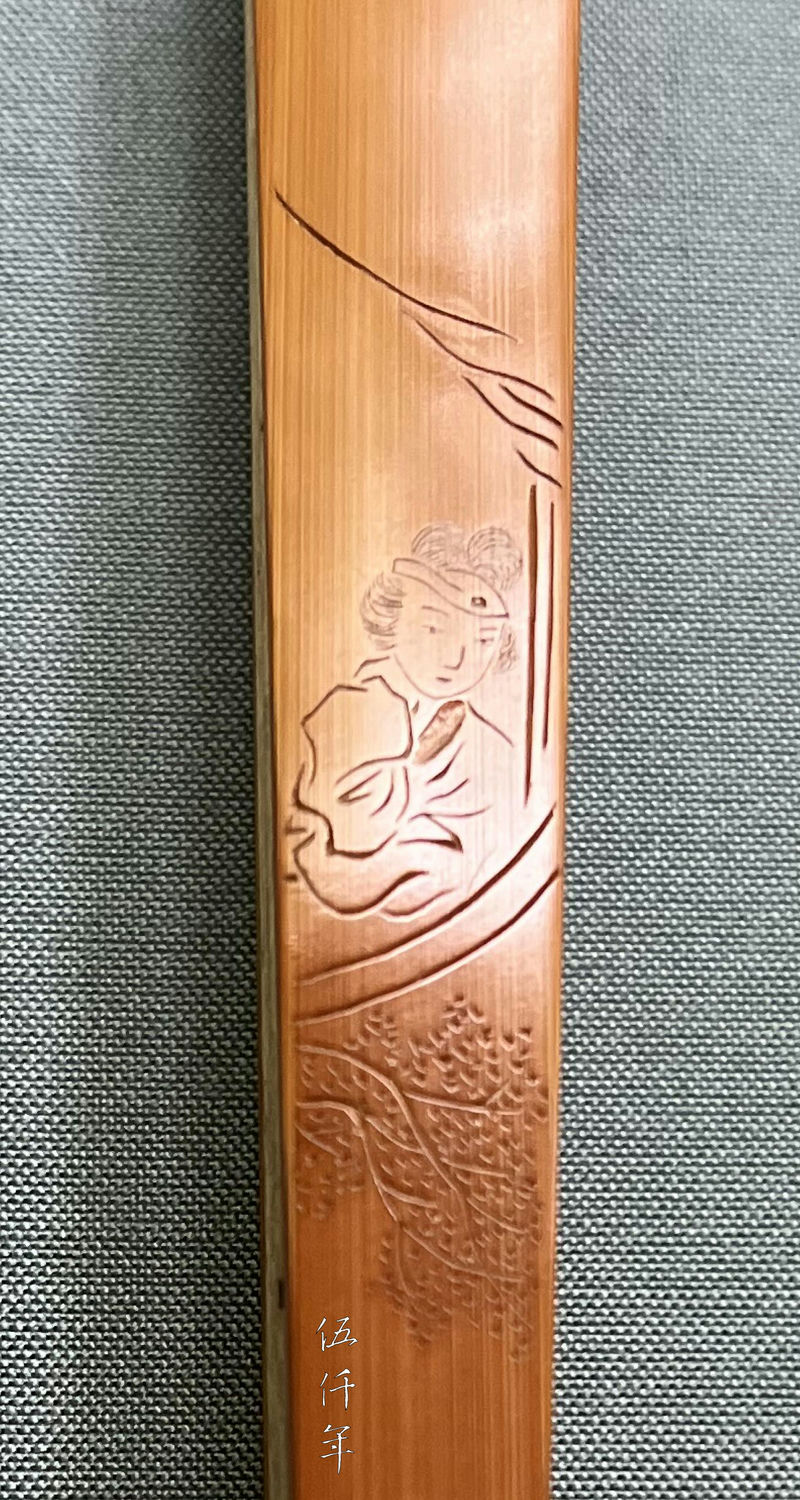

The two words hsien-ch’ou (獻醜) engraved on the upper part of the first bamboo fan guard

Picture of a literatus bowing engraved on the middle part of the first bamboo fan guard

Intaglio seal with the character K’ang (康) engraved on the lower part of the first bamboo fan guard

On one of the bamboo guards of the folding fan is an engraving of a literatus bowing with two words hsien-ch’ou (humbly presenting one's shortcomings 獻醜) in clerical script, and below that, a small intaglio seal: K’ang (康).

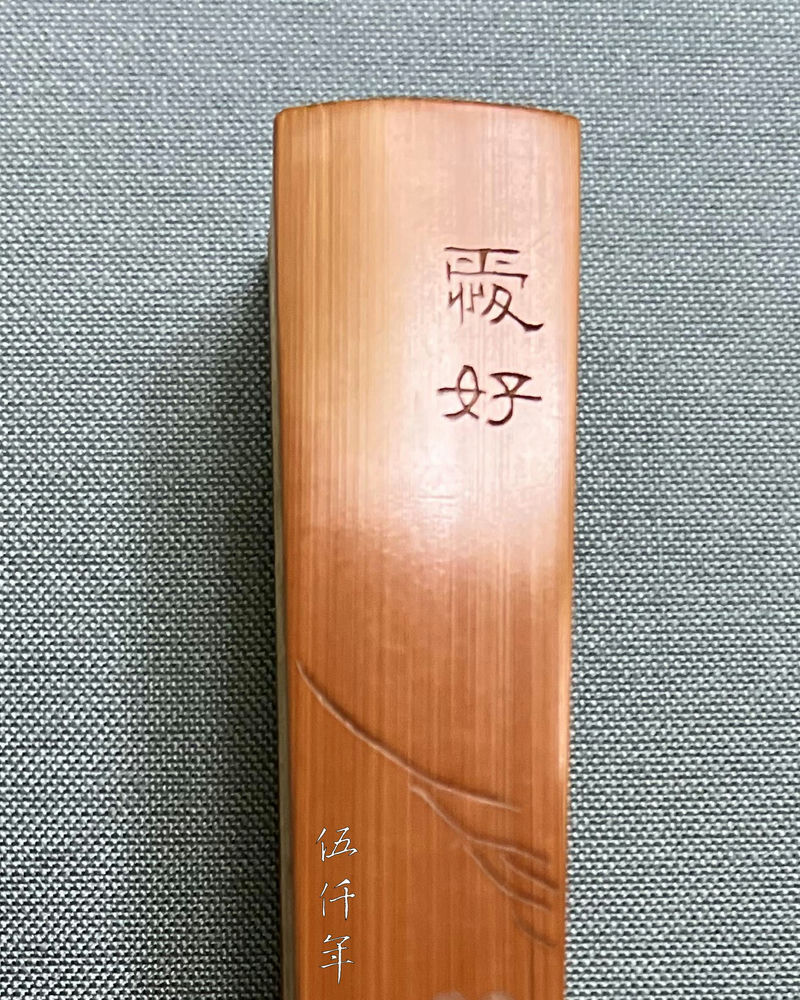

The two words ai-hao (愛好) engraved on the upper part of the second bamboo fan guard

Picture of a lady sitting pensively engraved on the middle part of the second bamboo fan guard

Eight words of dedication engraved on the lower part of the second bamboo fan guard

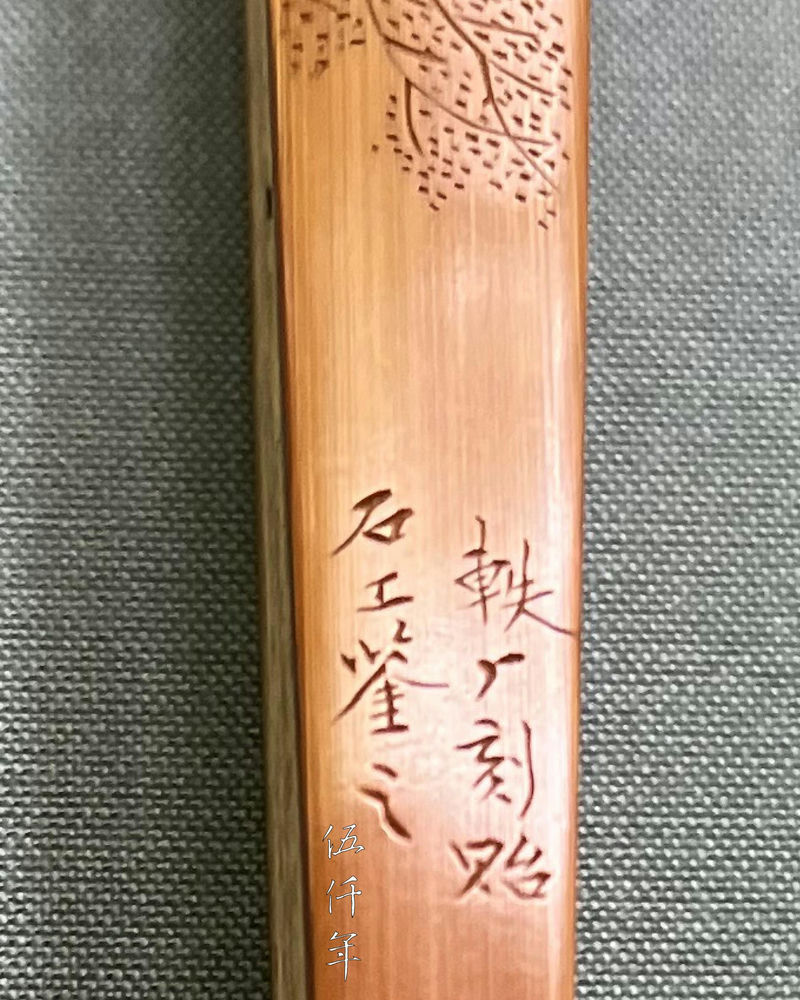

On the other bamboo guard of the folding fan is an engraving of a lady sitting pensively with two words ai-hao (penchant 愛好) in clerical script, and below that, an engraving of eight words that read I-an k’ei-i, Shih-kung chien-chih (I-an carved this as a gift, for the perusal of Shih-kung 軼厂刻貽,石工鑒之).

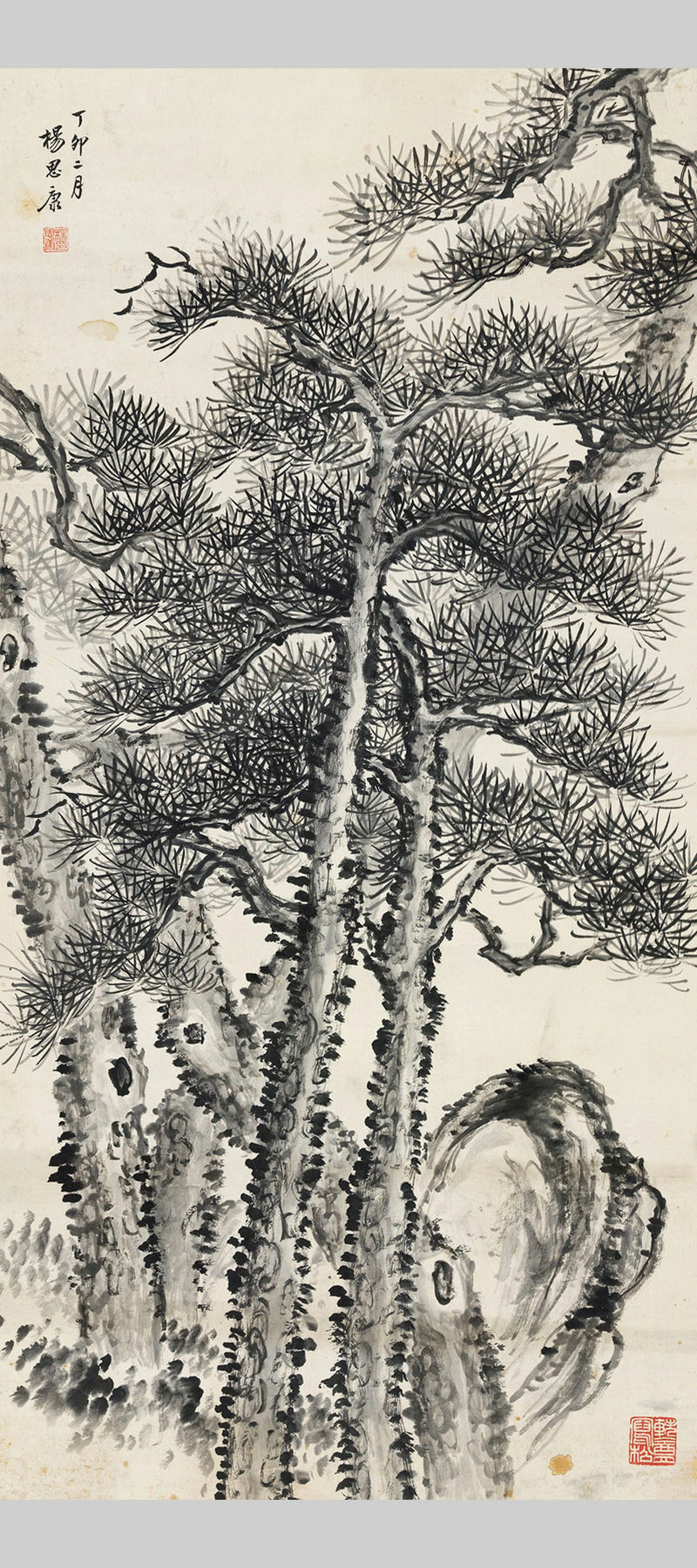

Yang Ssu-k’ang 楊思康 (1898–1943), hao I-an (軼厂), native of Chiang-hsia, Hopeh Province. He was a bamboo engraver. I once saw a painting of a pine tree by Yang, and realized he was skilled in painting and calligraphy as well.

Painting of pine tree by Yang Ssu-k’ang (楊思康) dated February of ting-mao year, the equivalent of the 16th year of the Republic (1927)

Yüan K’ei-wen composed calligraphy and painting on the fan as a gift to Shih-kung. He further commissioned I-an to carve the bamboo guards of the fan. These efforts demonstrated that this gift was meticulously prepared.

Portrait of Shou Hsi (壽璽)

Shih-kung (石公) is Shou Shih-kung (壽石工 1885-1950), original name Hsi (璽), Shu (鉥), tzu Shih-kung (石工), Shih-kung (石公), Shuo-kung (碩公), Wu-hsi (務喜), hao Yin-kai (印丐), Chüeh-an (玨庵), Chüeh-an (玨厂), Chüeh-an (玨闇), Chüeh-kung (玨公), Tsui-kung (悴公), Pei-feng (悲鳳), Yüan-ting (園丁). He was a native of Shao-hsing, Chekiang Province, and lived in Peking, also known as Peiping (北平). He taught at the National Peiping Art Institute (國立北平藝術專門學院) and the National Peiping University Women’s Arts and Science College (國立北平大學女子文理學院). He was skilled in poetry and t’zu lyrics. He excelled in seal engraving and carved tens of thousands of seals. He left behind a number of publications including Tieh-wu Chai Seal Records (蜨蕪齋印稿), Chu-meng Lu Seal Carving Study (鑄夢廬篆刻學), Seal Carving Lecture Notes (篆刻學講義), Chronological Record of Tieh-wu Chai Personal Seals (蜨蕪齋自製印逐年存稿), and Chüeh An Lyrical Poems (玨庵詞) and others.

Group portrait of Mr. Huang T’ien-ts’ai (黃天才 middle) , Mr. Tung Liang-shuo (董良碩 left) and Mr. Soong Shu Kong (宋緒康 right) at the opening ceremony of The Cultural World of a Ci Poet Exhibition in the 96th year of the Republic (2007)

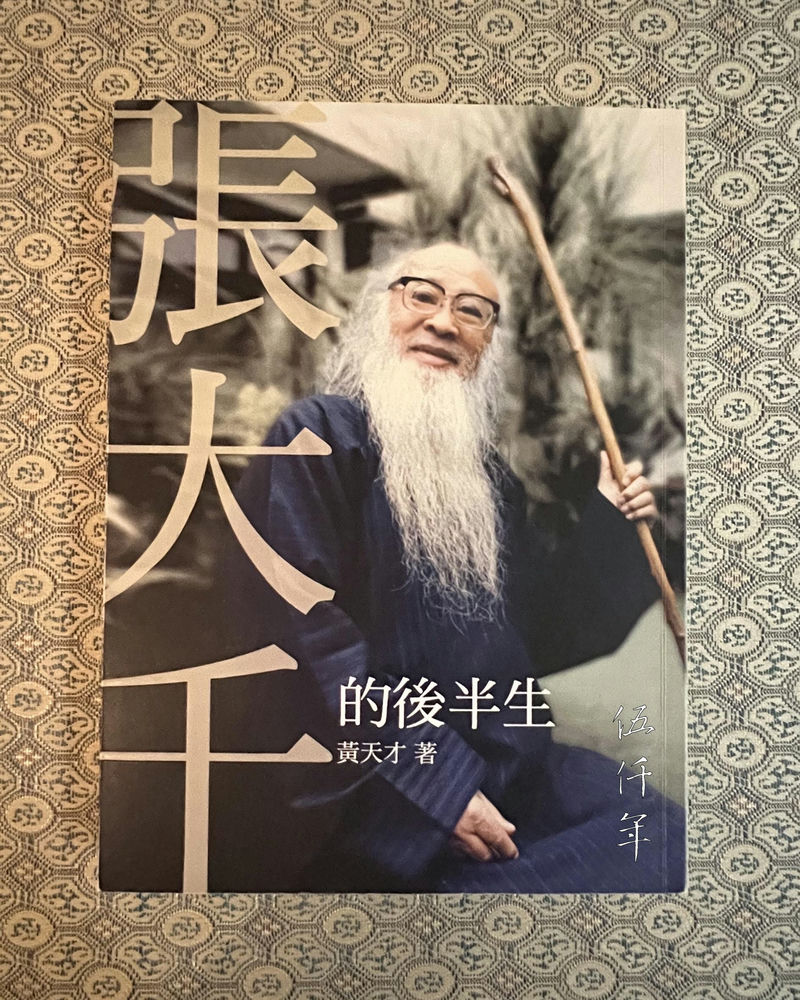

Yüan K’ei-wen’s folding fan of calligraphy and painting was previously in the collection of Mr. Huang T’ien-ts’ai (黃天才 1924-2022). Mr. Huang T’ien-ts’ai’s studio name was Shan-tsai-shan Chai (善哉扇齋). He was a native of Yang-shuo, Kwangsi Province, He graduated from the National Chengchi University (國立政治大學). He arrived in Taiwan before the fall of mainland China to the communists in the 38th year of the Republic (1949). Subsequently he held various positions including special representative to Japan for the Central Daily News (中央日報), president of the Central Daily News, and president and chairman of the Central News Agency (中央通訊社). While he was in Japan, the Chinese communists launched the Cultural Revolution. He recalled that the Red Guards ransacked homes throughout China seizing countless items of calligraphy, paintings and folding fans. The Chinese communists then shipped them in large quantities by container load to sell in Japan in exchange for foreign currency. Mr. Huang cultivated his refined hobby of collecting folding fans in Japan, and eventually became the finest collector of folding fans of his generation. He authored several books including Chang Dai-chien’s Later Life (張大千的後半生), Interviews with News Personalities (新聞人物專訪實錄), People and Events in Sino-Japanese Diplomacy: Huang T’ien-ts’ai’s Interviews in Tokyo (中日外交的人與事: 黃天才東京採訪實錄), Chang Dai-chien, a Genius in Five Hundred Years (五百年來一大千), Chiang Soong Mei-ling: A Legend that Spans Three Centuries (世紀蔣宋美齡: 走過三個世紀的傳奇) and others.

Mr. Huang T’ien-ts’ai giving a speech at the opening ceremony of The Cultural World of a Ci Poet Exhibition in the 96th year of the Republic (2007)

In July of the 96th year of the Republic (2007), I held an exhibition of cultural artefacts titled The Cultural World of a Ci Poet (一個詞人的翰墨因緣) at the National Museum of History (國立歷史博館) in Taipei, and invited Mr. Huang T’ien-ts’ai to deliver a speech at the opening ceremony. In another few years, in June of the 102nd year of the Republic (2013), I held an exhibition of cultural artefacts at the National Museum of History once more, titled Mountains Ablaze-Benevolence and Righteousness, Salvation and Existence 1839-1946. Mr. Huang T’ien-ts’ai again kindly agreed to give a speech. His generosity is dearly remembered.

Front cover of Chang Dai-chien’s Later Life by Mr. Huang T’ien-ts’ai

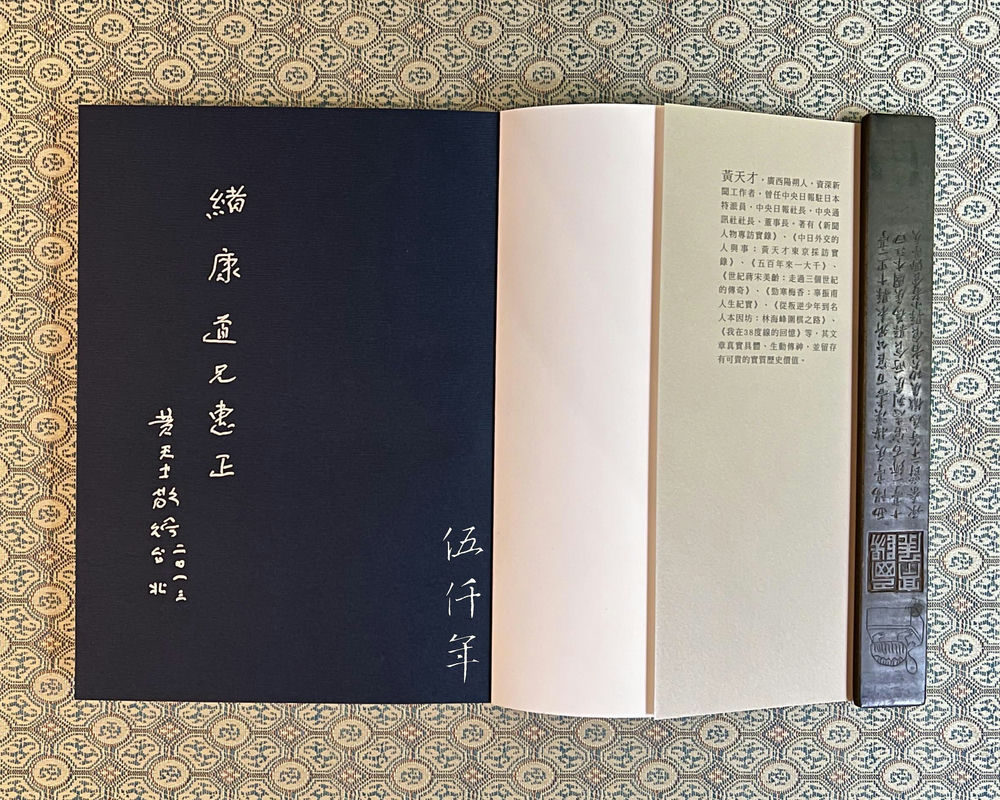

Inside page of Chang Dai-chien’s Later Life by Mr. Huang T’ien-ts’ai with inscription

Inscription by Mr. Huang T’ien-ts’ai dedicated to Mr. Soong Shu Kong

During the early years of the Republic of China, collecting folding fans was a popular hobby. The connoisseur T’ang Lu-sun (唐魯孫 1907-1985) wrote: “Chang Po-chü (張伯駒 1898-1982) of the Yien Yieh Commercial Bank (鹽業銀行) is well-known from north to south for his love of fans. His collection of fans mainly featured calligraphy and paintings by contemporary literati. As he is a devotee of Peking Opera, he has deep friendships with those famous singers who excel in calligraphy and paintings, so he can be said to have collected all of their works.”

Portrait of Chang Po-chü

For a great collector like Chang Po-chü, he was not only devoted to folding fans, he also valued ancient and contemporary creations equally

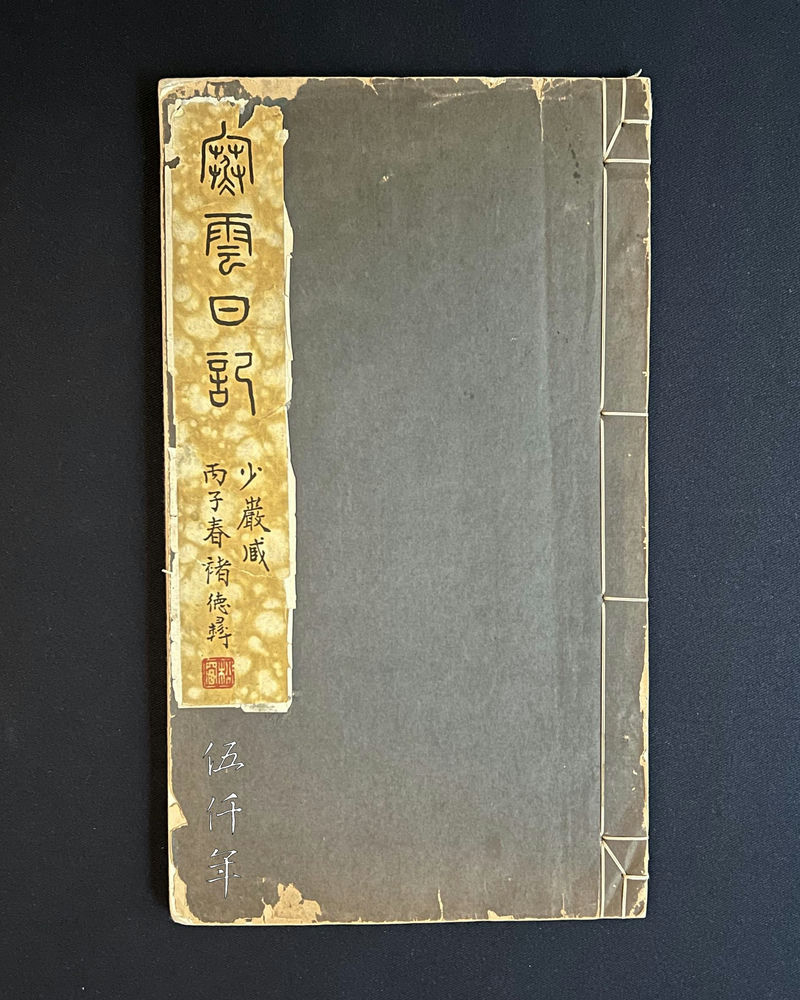

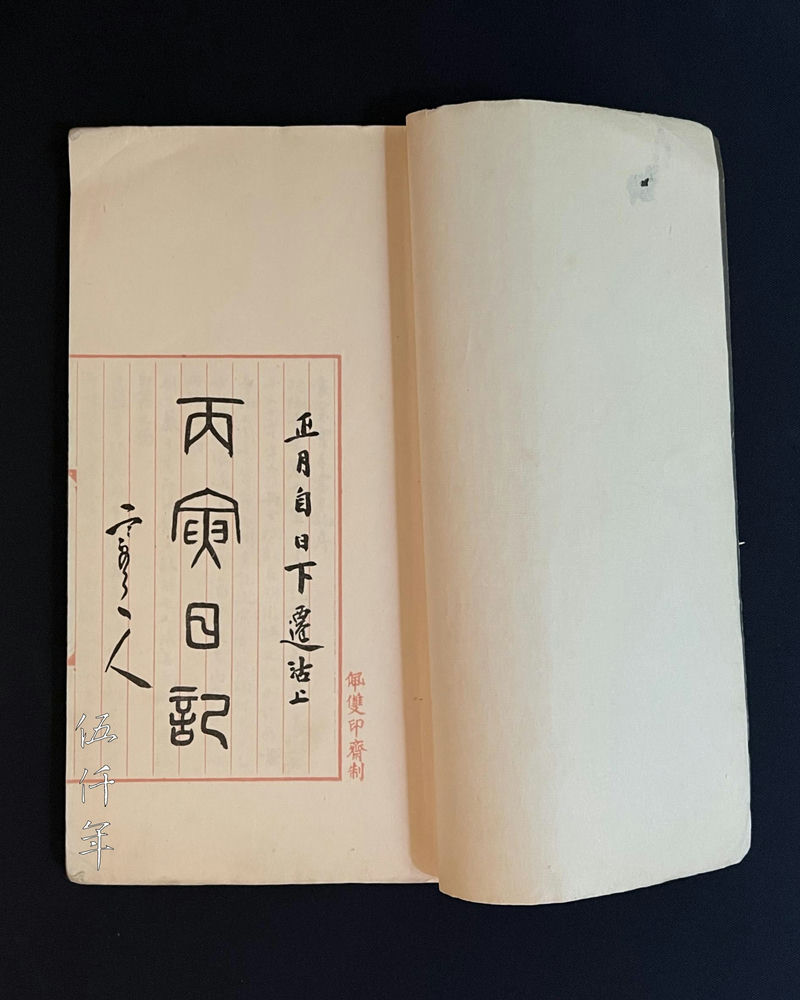

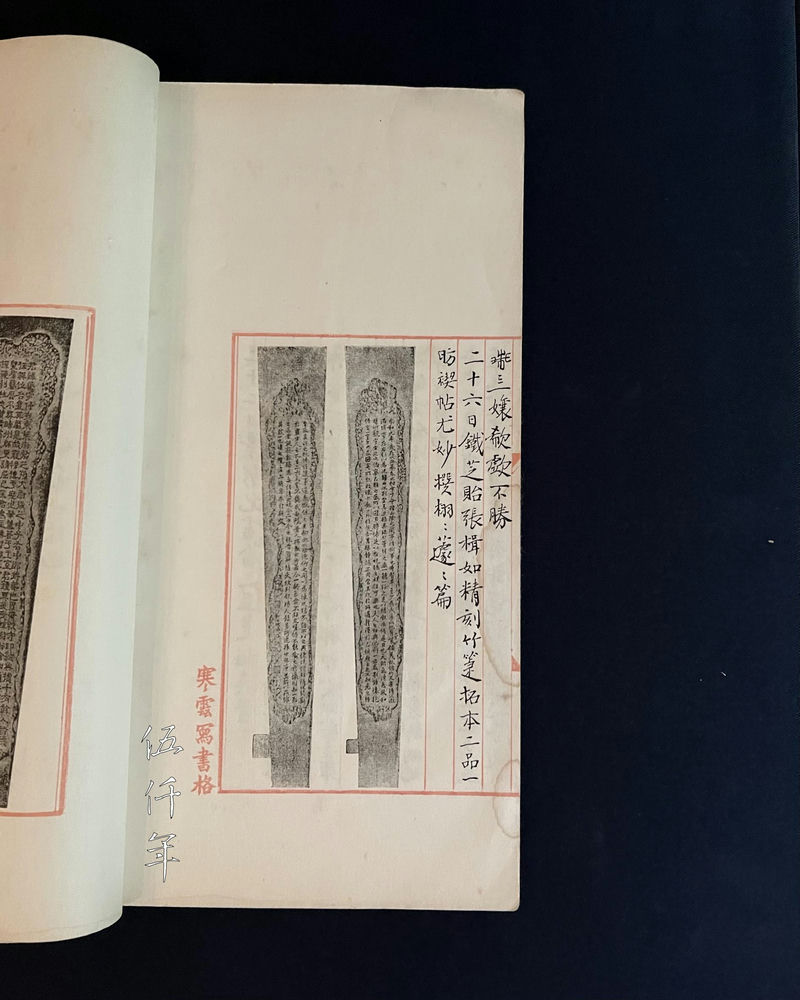

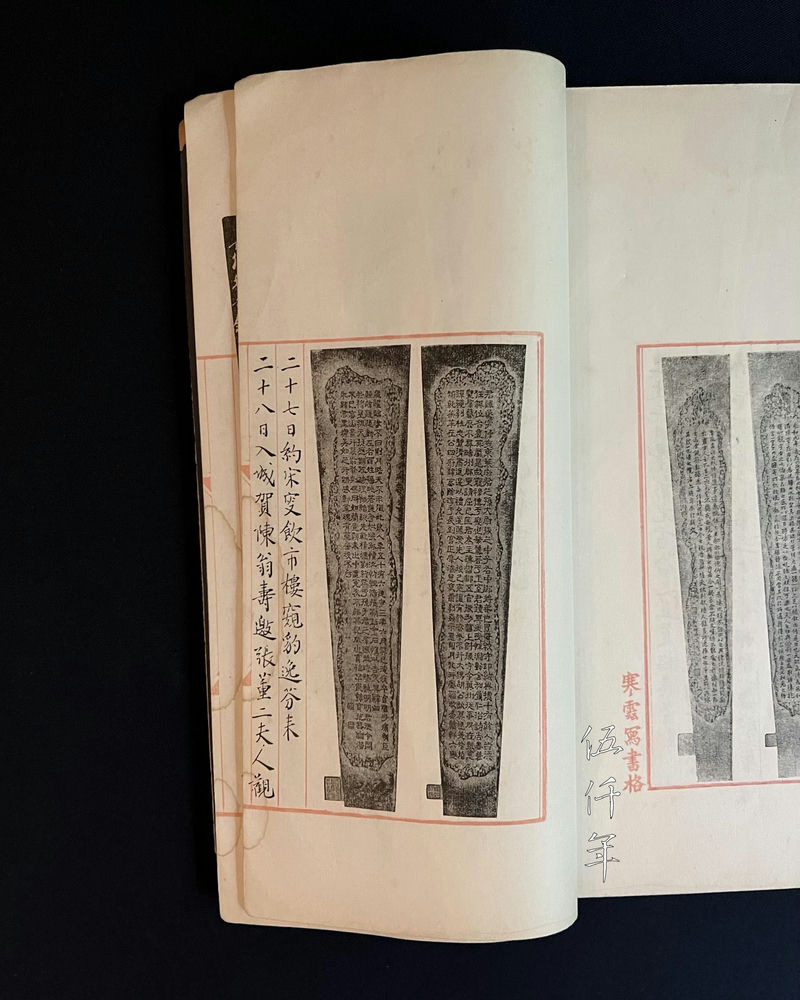

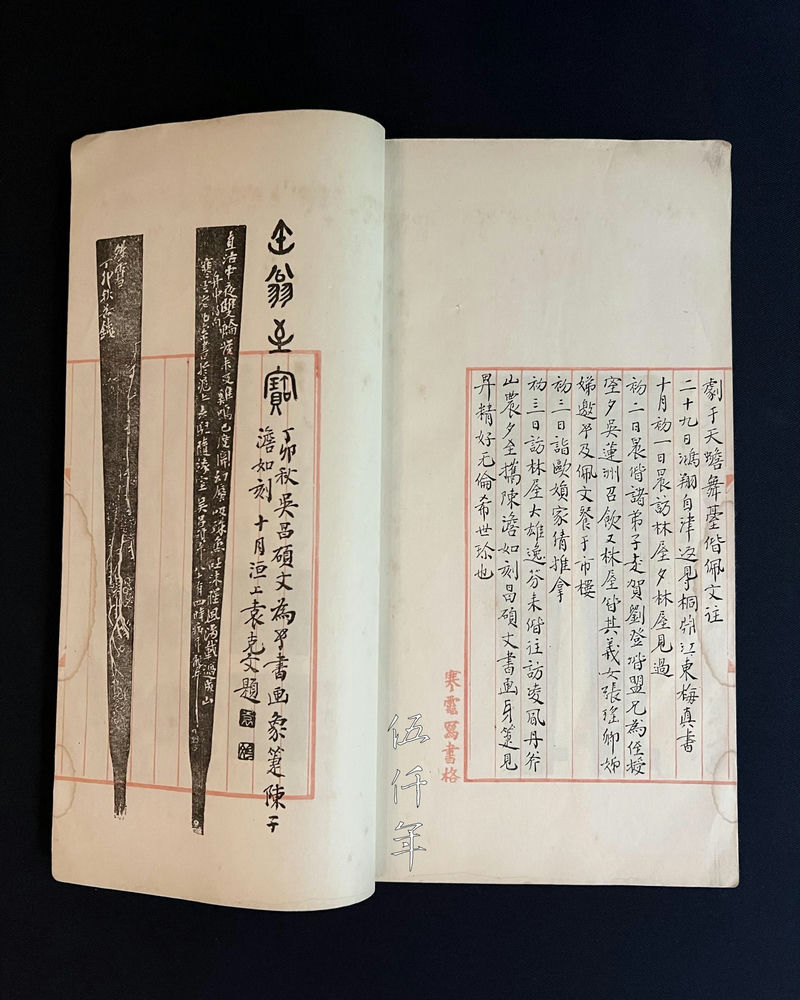

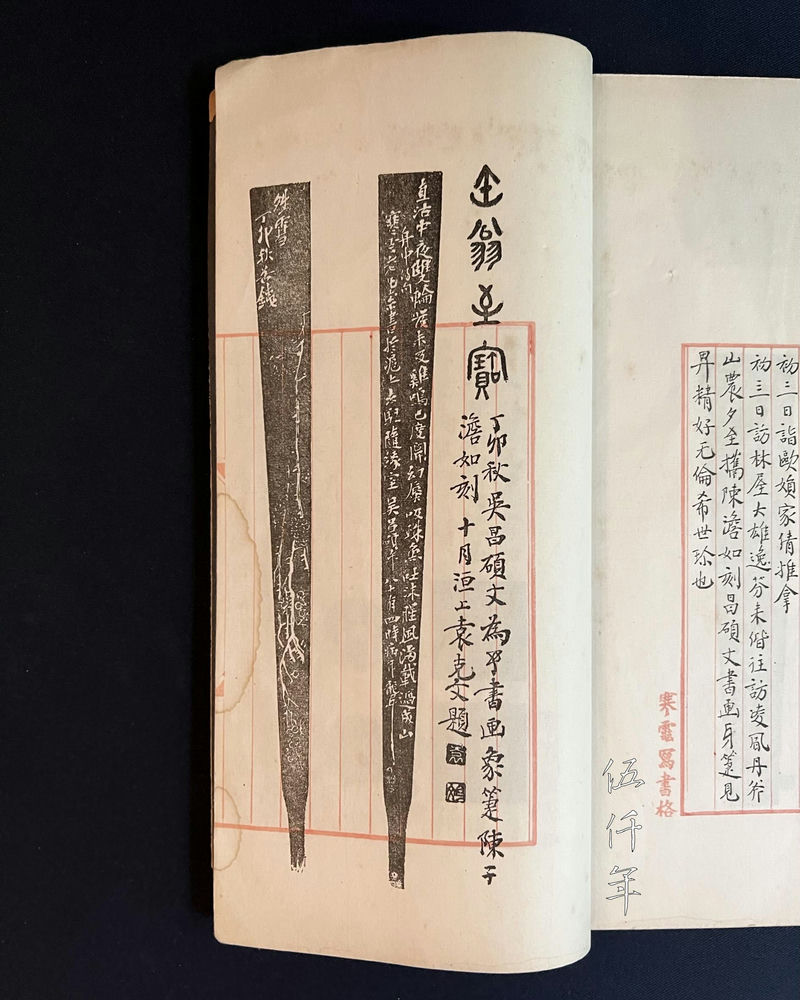

Front cover of Han-yün’s Diaries for the Years Ping-yin and Ting-mao

Title page of Han-yün’s Diaries for the Years Ping-yin and Ting-mao

In Han-yün’s Diaries for the Years Ping-yin and Ting-mao (寒雲丙寅丁卯日記), Yüan K’ei-wen recorded various entries related to the engraving of guards of folding fans, revealing a great passion for this field. The diary entries read:

“23 August, ting-mao year (丁卯 1927)

Shan-nung (山農) sent me a letter showing the art works done by Fou Chang (缶丈) for my ivory fan. For one of the fan guards, there is a piece of calligraphy of a poem, for the other fan guard, there is a painting of prunus. Even at the venerable age of eighty three years old, he is still able to create these exquisite miniature pieces with great skill. It is truly admirable and moving. I beseeched Shan-nung to ask Chen Tan-ju (陳澹如) to engrave them.

Note: Shan-nung (山農) may be Liu Wen-chai (劉文玠 1878-1932), a literatus from Shanghai. Fou Chang (缶丈) was Wu Chang-shuo (吳昌碩 1844-1927), a master of calligraphy, painting, and seal carving. Chen Tan-ju (陳澹如 1884-1953) was a bamboo engraver.

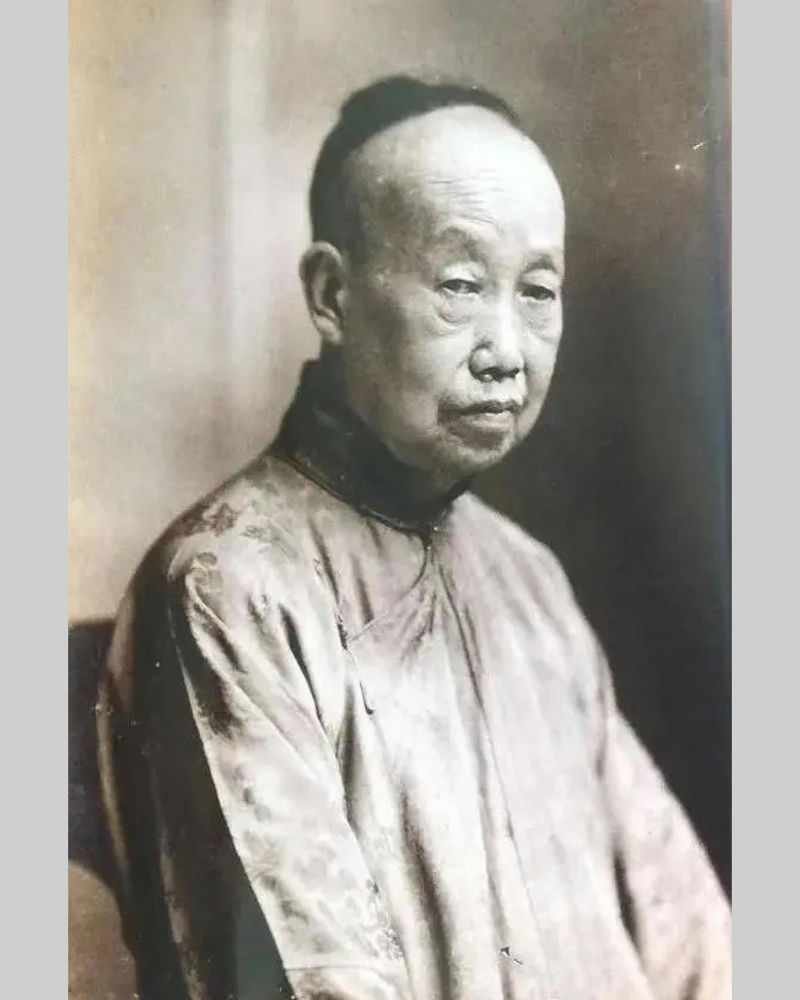

23 August entry in Han-yün’s Diaries for the Years Ping-yin and Ting-mao

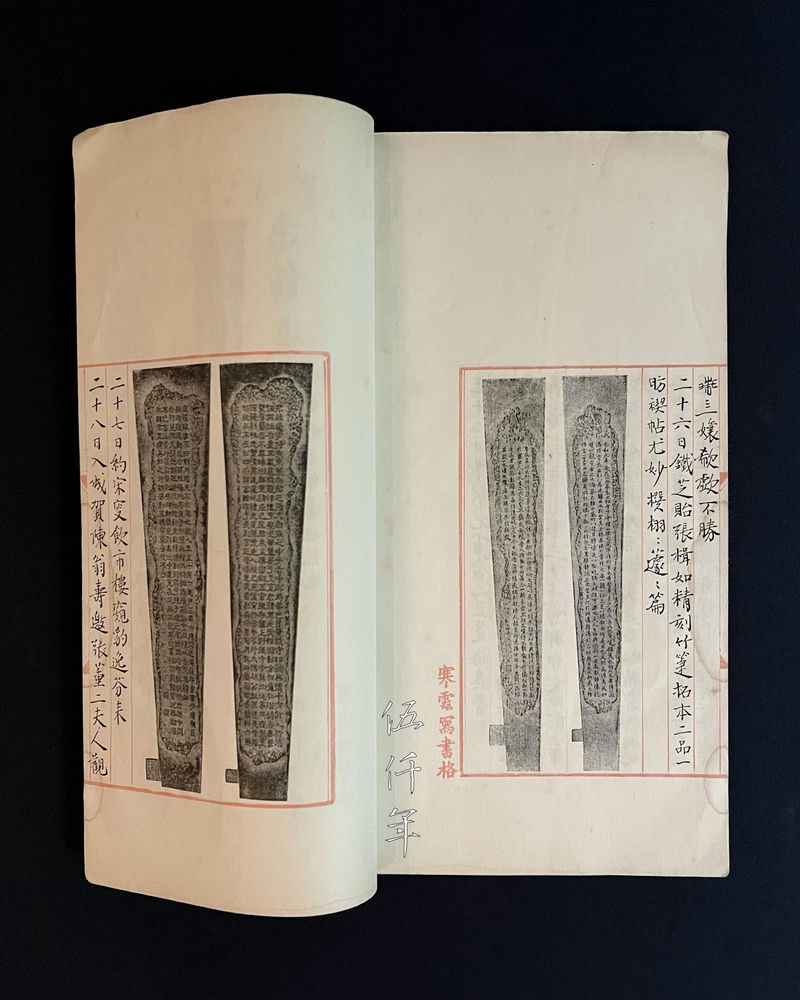

Portrait of Wu Chang-shuo (吳昌碩)

26 September, ting-mao year (丁卯 1927)

Tieh-chih (鐵芝) gifted me two sets of ink rubbings of bamboo fan guards engraved by Chang Chi-ju (張楫如). One set is the engraving of the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion. It is wonderful. The other set is the engraving of the essay Contentment and Pleasure (栩栩蘧蘧篇).

Note: Tieh-chih (鐵芝), his last name was Chin (金). He was skilled in seal carving and bamboo carving. He was a disciple of Yüan K’ei-wen. Chang Chi-ju (張楫如 1870-1925), also known as Hsi-ch’iao (西橋), was a bamboo engraver.

26 September entry in Han-yün’s Diaries for the Years Ping-yin and Ting-mao, with images of ink rubbings of two sets of bamboo fan guards engraved by Chang Chi-ju (張楫如)

Images of ink rubbings of the first set of bamboo fan guards engraved by Chang Chi-ju

Images of ink rubbings of the second set of bamboo fan guards engraved by Chang Chi-ju

Portrait of Chang Chi-ju (張楫如). Photograph courtesy Mr. Kuo

3 October, ting-mao year (丁卯 1927)

Shan-nung (山農) arrived in the evening, bringing the ivory fan of the calligraphy and painting of Wu Chang-shou (吳昌碩) which was engraved by Chen Tan-ju (陳澹如). The craftsmanship is exquisite and unparalleled, a rare treasure in the world.

Note: Chen Tan-ju spent about one month and a half carving the guards of the ivory fan with the calligraphy and painting of Wu Chang-shuo. Yüan K’ei-wen lavished high praises on the artwork. He was a true devotee of the art of engraving.”

3 October entry in Han-yün’s Diaries for the Years Ping-yin and Ting-mao, with images of ink rubbings of a set of bamboo fan guards, the painting and calligraphy by Wu Chang-shuo, the engraving by Chen Tan-ju (陳澹如)

Images of ink rubbings of a set of bamboo fan guards, painting and calligraphy by Wu Chang-shuo, engraving by Chen Tan-ju

Portrait of Ch’en Tan-ju (陳澹如). Photograph courtesy Mr. Kuo Hai

In the 25th year of the Republic (1936), Liu Ping-i (劉秉義) arranged to publish his treasured Han-yün’s Diaries for the Years Ping-yin (1926) and Ting-mao (1927). He wrote in the postscript:

“The author did not cherish his works during his lifetime, and what remains is only one volume of Calligraphy on Coins, and seven volumes of the Diaries. Though he spent time on poetry and drinking, he never missed writing his diaries. I acquired his diaries for the years of ping-yin (1926) and ting-mao (1927). … The two volumes of diaries for chia-tzu (甲子 1924) and i-ch’ou (乙丑 1925) were taken by Mr. Chang of Shenyang and it is not known if they still exist. Fortunately, the two volumes of ping and ting years do exist, and their contents can be studied.”

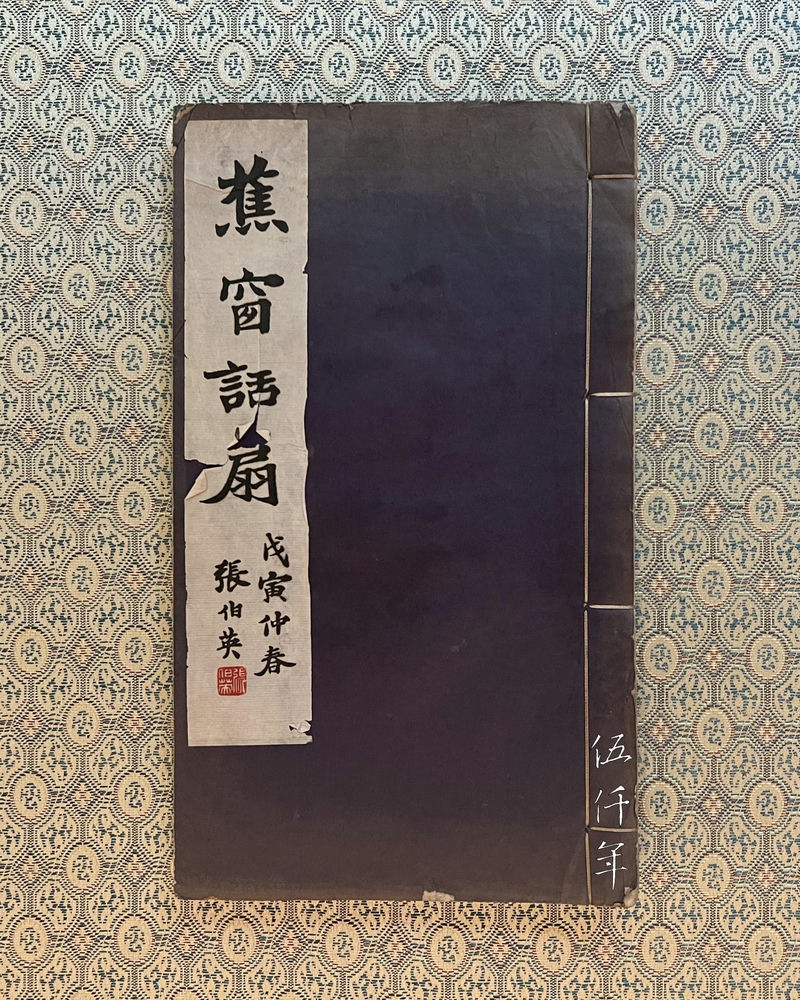

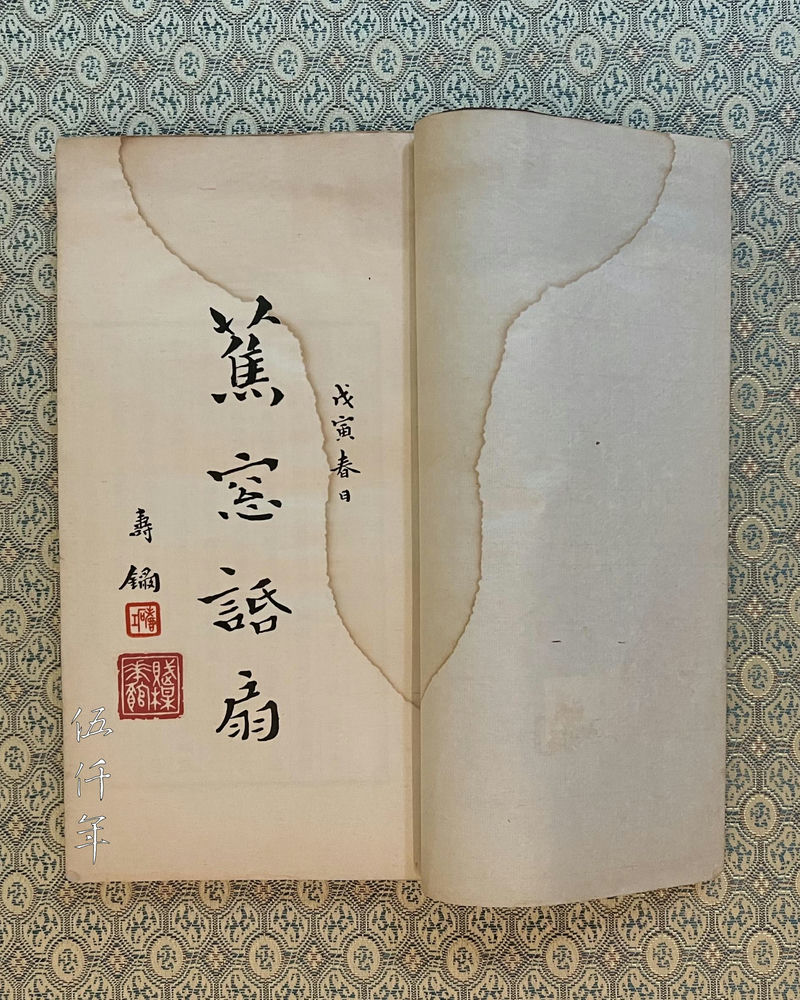

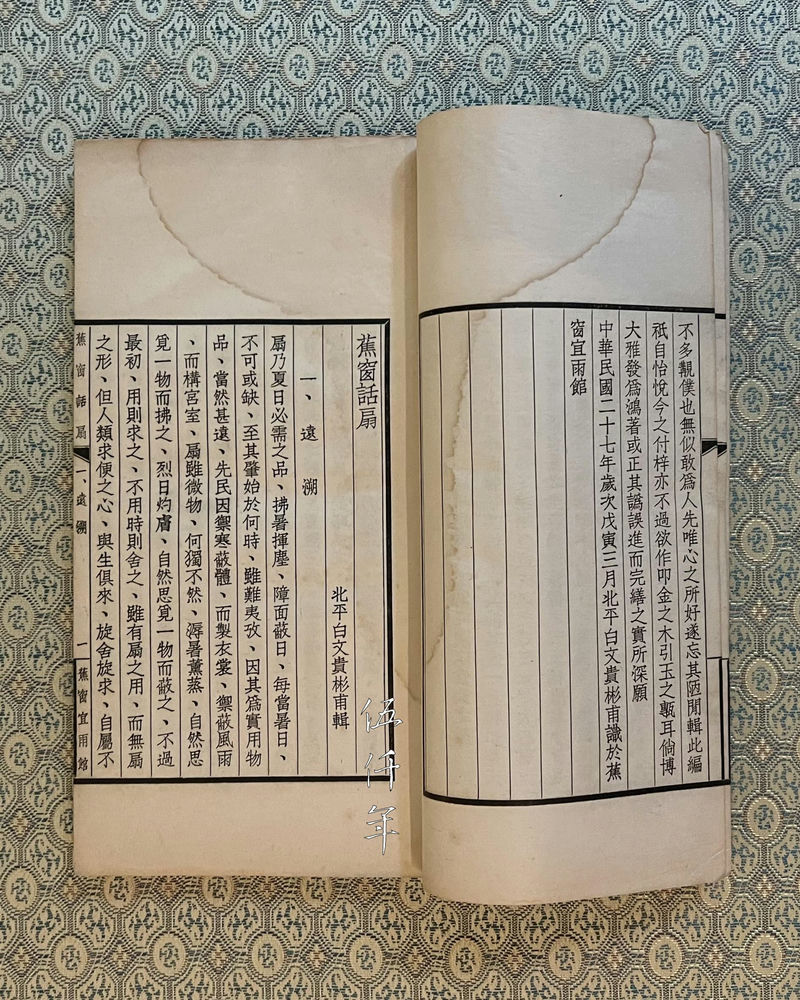

Front cover of Chiao-ch’uang Talks about Fan (蕉窗話扇) by Pai Wen-kuei (白文貴)

Title page of Chiao-ch’uang Talks about Fan (蕉窗話扇) by Pai Wen-kuei (白文貴)

Mr. Chang of Shenyang refers to Chang Hsüeh-liang (張學良), a warlord. If the i-ch’ou year Diaries has not been destroyed, it will probably contain an account of the gift of this fan to Shou Hsi and the commissioning of bamboo fan guards carved by Yang I-an.

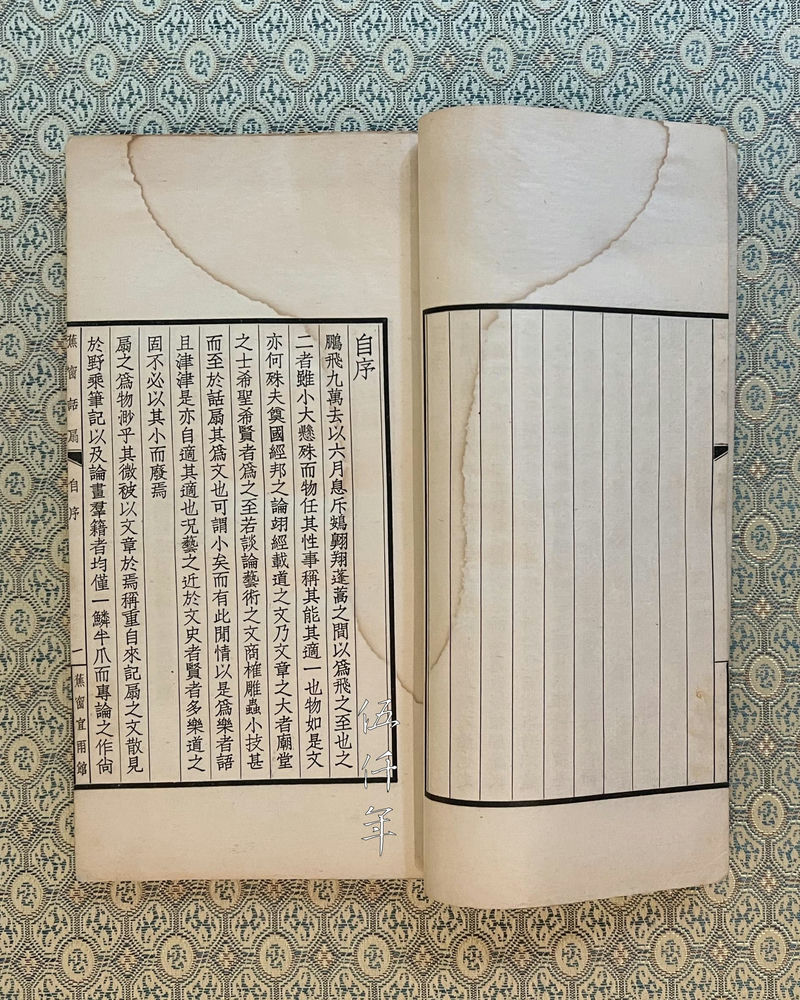

In the 27th year of the Republic (1938), the fan collector Pai Pin-fu (白彬甫) wrote Chiao-ch’uang-hua-shan (Chiao-ch’uang Talks about Fans 蕉窗話扇), the only monograph on Chinese fans from the ancient times to the present. The book contains detailed research and extensive insights. Unfortunately as it was privately printed, there are few copies of it and it is rare to find. Therefore, a few sections of the contents are excerpted here to provide a sampling.

The text reads:

“Ancient people mostly used bones, horns, feathers, and fur to make tools and utensils. This was due to the influence of the nomadic and hunting era, which was relatively recent and their customs were passed down. Hence the earliest fans were made of feathers. In Annotations on the Ancient and Modern (古今注), it is stated: ‘Emperor Shun (舜) wanted to expand his apprehension, and sought virtuous people to assist him, he made the Wu-ming Ceremonial Fan (五明扇).’ It also says: ‘The making of feather fans began with the Yin Emperor Kao-tsung (殷高宗).’ ……

Painting on round silk fans was first recorded in the Three Kingdoms period. Chang Yen-yuan (張彥遠 815-907) of the Tang dynasty wrote in Records of Famous Paintings from the Dynasties (歷代名畫記) : ‘Yang Hsiu (楊修 175-219) and Wei T’ai-tsu (魏太祖 155-220) painted a fan, the accidental dot was mistaken as a fly’. ……

After the Sung dynasty, fan painting and calligraphy began to be applied to round fans, which peaked during the Yüan dynasty. This is in line with the principle of things reversing when they reach their extremes, with the extreme popularity of one thing leading to its decline. Also, folding fans gradually became popular from the Southern Sung dynasty (南宋 1127-1279) … By the time of the Ming dynasty, folding fans were in great demand while round silk fans had no takers.

The folding fan, commonly called che-shan (folded fan 摺扇), was called in ancient times chü-t’ou-shan (gathered head fan 聚頭扇) or chü-ku-shan (gathered bone fan 聚骨扇). It started in the Northern Sung dynasty (北宋 960-1127), but its prototype can be traced back to the Southern Ch’i dynasty (南齊 479-502). Painting and calligraphy on the folding fan was not common during the Northern Sung dynasty, but it gradually took root during the Southern Sung dynasty. …

Although folding fans did not originate from the Yung-le period (永樂 1403-1424), it reached its zenith after the Yung-le period. …

It is difficult to verify the shape of the fan frame during the Northern Sung dynasty, but according to Yun-lu man-ch’ao (雲麓漫鈔): ‘The Sung people used steamed bamboo as the frame of the folding fan, sandwiched between fine silk, while wealthy families used ivory as frame and decorated them with gold and silver.’ From these few words, perhaps the shape of the fan might be similar to the current design. According to Chan ching-feng (詹景鳳 1532-1602), the shape of the folding fan in the Southern Sung dynasty was no different from that of today. …

The fan frames of the Yüan and Ming dynasties have an antique patina and are treasured as such. However, there were no outstanding works of engraving art. In the Ming dynasty, there were quite a few people famous for making bamboo fans. …

Fan frames of bamboo are the best, as they are durable and flexible. Over time, they turn yellow like the color of liquorice, yellow jade, goose fat, cherry jade. They have an antique charm and are beautiful to look at. Moreover, they are suitable for engraving, and the fan stays tightly shut and will not loosen.

I believe that the engraving of guards of folding fans can also be divided into two categories: p’ing-k’ei (flat engraving 平刻) and liu-ch’ing (engraving without removing the bamboo culm sheath 留青). Flat engraving refers to wet sanding the bamboo fan frame, carving words and pictures by relief and intaglio, and can be further divided into deep engraving and shallow engraving. Liu-ch’ing (留青), also known as skin carving (皮雕), is done on special fan frames that do not scrape away the outer skin, adopting relief engraving.

Epigraphic, calligraphic and pictorial images are preferred for the engraving of fan guards. When using the engraving knife, it should be handled with skill and ease, without thick areas and leaving appropriate gaps. As the heart desires, the knife follows, expressing fully the beauty that lies within the artist’s heart. At times, the cutting marks are vivid and clear, but it is best not to polish them, lest they obscure the artistic charm. The more exposed the angles and edges, the more they highlight the skill of the artist. Although the layers may be extremely intricate, yet it should not appear forced or laboured. At times, the engraving may be simple yet it should not appear empty. Although it comes from the hands of a master, it appears as if naturally formed, its charm emanating from the spirit and its lasting appeal stemming from its flavour. This concerns the skill with the knife. As for the miniaturization of inscriptions on bronze ritual and wine vessels, ancient tiles and coins, as well as the copying of old ink rubbings, it is essential to capture the spirit of the original without deviation. This concerns the breadth of learning and refinement. This goes without saying for artists who are experts of calligraphy and painting; occasionally they engrave their old works or compose new ones, further enhancing their artistries. The fusion of engraving, calligraphy, painting, literature and art in one unison, can then be described as reaching the pinnacle of art. Although this is to be sought, it is probably hard to come across. …

Shan-yeh (fan leaf 扇葉) is also called shan-yeh ( fan sheet 扇頁), commonly called shan-mien (fan face 扇面), also known as pien-mien (convenient face 便面), p’ing-mien (screen face 屏面), chieh-t’ou (bamboo head 箑頭), chieh-mien (bamboo face 箑面). These names are used by the literati to avoid clichéd terms. ...

During the Northern Sung dynasty, written records only show the phrase ‘steamed bamboo as the frame of the folding fan, sandwiched between fine silk’. Although it cannot be concluded that all fan leaves that time were made of fine silk, it is likely that silk fabrics were primarily used. …

During the Southern Sung and Chin dynasties, the works of Ma Yüan (馬遠 1160-1225), Ma Lin (馬麟 approximately 1180-1256), Chao Yen (趙彥), Yang Mei-tzu (楊妹子), and others all worked on silk fan faces, indicating a gradual shift from ling-lo (fine silk 綾羅) to chüan (silk 娟). ...

After the Yuan dynasty, most fan leaves were made of paper, some decorated with gold inlay. ...”

First page of Preface by Pai Wen-kuei in Chiao-ch’uang Talks about Fan

Second page of Preface by Pai Wen-kuei in Chiao-ch’uang Talks about Fan

Pai Pin-fu (白彬甫), original name Wen-kuei (文貴), lived in Peiping and had the studio name Chiao-ch’uang-i-yü Kuan (蕉窗宜雨館). He was a professor of military science. Over the course of recent decades, in the face of numerous catastrophes and disasters faced by the country, none of the old family collections remain. As for Pai Pin-fu, his name survives only in obscurity. His work Chiao-ch’uang Talks about Fans (蕉窗話扇) offers valuable scholarship and insights into fan collecting. The title slip on the book cover features a calligraphic inscription by the calligrapher Chang Po-ying (張伯英 1871-1949), and the calligraphy on the title page is by the seal carver Shou Hsi, both eminent artists in Peiping.

During my childhood in Hong Kong, I occasionally saw members of the older generation who were in the habit of carrying folding fans. Now this custom is extinct. In the past, folding fans were a means of mutual exchange and for socialization amongst the literati, and fan faces with calligraphy and paintings were very common. Holding a fan with calligraphy and painting by a distinguished poet, or by a prominent artist, or by an eminent gentleman in politics, immediately manifests the fan owner's own learning, refinement, and status. The small size of the folding fan belied its larger purpose. The rise and fall of folding fans also reflect the stature and decline of traditional culture. Since poetry, literature, calligraphy, and paintings were all appreciated and mastered by the literati, the fashion of the folding fan was thus made possible. This is no longer accomplishable today. A hundred years from then, perusing the folding fan with calligraphy and painting gifted by Yüan K’ei-wen to Shou Hsi, reflecting on the splendour of the early years of the Republic, such sorrow for the passing of an era.

Detail of the prunus painting on one side of the folding fan by Yüan K’ei-wen

Related Contents:

The Life of Mei-yün (眉雲) - Concubine of Yüan K'ei-wen (袁克文), by Liu Ching-yün