Yüan K'ei-wen (袁克文), the second son of Yuan Shih-k'ai (袁世凱) who briefly became emperor in the early Republican era, was indeed a man of letters. However his fame was in part derived from his father’s eminence. He led a bohemian life, with fifteen to sixteen wives and concubines. Amongst them Mei-yün (眉雲) was particularly well known. Perhaps a man laden with passion is also a man of casual passion. The historian Mr. Liu Ching-yün extensively researched the life of Mei-yün. The misfortunes of vulnerable women in earlier times are still not eradicated today. If women’s rights are genuinely implemented far and wide, great happiness can be brought to the world, creating the foundation for Universal Harmony.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

An inscribed photograph of Yüan K’ei-wen taken in the 18th year of the Republic (1929)

In his article The Modern Ts’ao Tzu-chien (曹子建 192-232 AD)-Yüan Han-yün (袁寒雲 1896-1931, original name K’ei-wen 克文), the gourmet T’ang Lu-sun (唐魯孫 1907-1985) wrote of the charming and talented second young master of the Yüan family:

“He successively married fifteen or sixteen concubines including Wen-hsüeh (溫雪), Mei-yün (眉雲), Wu-ch’en (無塵), Ch’i-ch’iung (棲瓊), Hsiao-t’ao-hung (小桃紅), Hsüeh-li-ch'ing (雪裡青), Ch'in-yün-lou (琴韻樓), Su T’ai-ch’un (蘇台春), Hsiao-ying-ying (小鶯鶯), Hua Hsiao-lan (花小蘭), Kao Ch’i-yün (高齊雲), Yu P’ei-wen (于佩文) and T’ang Chih-chün (唐志君)”.

Cheng I-mei (鄭逸梅 1895-1992) also wrote in his lengthy article The Imperial Second Son-The Life of Yuan Han-yün (K’ei-wen) (皇二子袁寒雲的一生) that Yüan enjoyed womanizing:

“He married many concubines in the Tientsin and Shanghai areas, such as Wu-ch’en (無塵), Wen-hsüeh (溫雪), Ch’i-ch’iung (棲瓊), Mei-yün (眉雲), Hsiao-t’ao-hung (小桃紅), Hsüeh-li-ch’ing (雪裡青), Su T’ai-ch'un (蘇台春), Ch'in-yün-lou (琴韻樓), Kao Ch’i-yün (高齊雲), Hsiao-ying-ying (小鶯鶯), Hua Hsiao-lan (花小蘭), T’ang Chih-chün (唐志君), Yu P’ei-wen (于佩文), and so on.”

It was especially noted:

“Amongst the concubines, Ch’i-ch’iung (棲瓊) was very much liked by Madame Mei-chen (梅真夫人), Yüan’s principal wife, who spent three thousand taels of gold from her private savings to buy her freedom and often went to the movies with her. The Han-yün Diaries (寒雲日記) mentioned this repeatedly. Another concubine, Mei-yün (眉雲), passed away in Tientsin in the winter of the 18th year of the Republic (1929). K’ei-wen mourned her with a pair of calligraphy couplets and she was the only concubine allowed to enter the grounds of the family shrine.”

Now it is to be noted that T’ang Lu-sun and Cheng I-mei were friends with Yüan K’ei-wen, and Kao Po-yu (高伯雨 1906-1992), the expert in anecdotes and historical stories, particularly regarded Cheng a closer friend to K’ei-wen. In the afterword of The Secret World of Hsin-ping (辛丙秘苑) published in 1975 by Hong Kong Dawa Culture and Communications Ltd. (香港大華出版社), he said that Cheng was:

“K’ei-wen’s old friend, and during K’ei-wen’s last four years in Shanghai, they saw each other frequently.”

Closer examination of Cheng I-mei’s paragraph show up some problems. Firstly, the order of the concubines’ relationships with K’ei-wen is somewhat confusing. Perhaps this can be acceptable. Fortunately, in Volume 1 Issue 26 of The Red Rose (紅玫瑰) (published on New Year Day according to the Chinese Agricultural Calendar of 1925, which is the equivalent of 24 January 1925), there is a column titled Literary Conversation (文壇清話) with Cheng’s own chronicle in his early years:

“Throughout his life, Yüan K’ei-wen was blessed with luck in his encounters with beautiful women. Before Hsiao-ying-ying (小鶯鶯), there was T’ang Chih-chün (唐志君) who many people knew about. But before T’ang Chih-chün there were various concubines Chao-yün (昭雲), Wen-yün (文雲), Wu-ch’en (無塵), Wen-hsüeh (溫雪), Yen-hsüeh (豔雪), Hsiao-lan (笑蘭) who few people knew about.”

Volume 2 Issue 1 of Half-Month Magazine published a photograph of Yüan K’ei-wen and concubine T’ang Chih-chün inscribed to Chou Shou-chüan

The sequence of Yüan K’ei-wen’s concubines before Mei-yün (眉雲) in this list is much more exact. It would appear that Cheng in his later years had a lack of ready information, thus his accounts then could not compare with those he made during earlier times. It is a notable and surprising mistake for him to treat Mei-yün (眉雲) and Ch’i-ch’iung (棲瓊) as two different persons. Nowadays people are not aware of this mistake and assumed this is truthful information. This has led to countless errors. This article is written for the purpose of clarification.

Volume 4 Issue 2 of Half-Month Magazine published A Small Photograph of Ch’i-ch’iung

In Volume 4 Issue 2 of The Half-Month Magazine (半月雜誌), edited by Chou Shou-chüan (周瘦鵑 1895-1968) and published on 26 December 1924, there is a photograph titled: A Small Picture of Ch’i-ch’iung (棲瓊小影) on the front page. It shows the side profile of a young woman with delicate features and a slight smile. In Conversing While Listening to Drums and Drinking Wine (聞鼙對酒譚) by K’ei-wen on his leisure activities in Tientsin, there is an article which reads:

“Ya-yün (雅雲), a native from Ch’ang-shu of Kiangsu Province, belongs to the T’ung-i Troupe (同義班) of Ta-hsing Neighborhood, Nan-shih District. Her father died when she was a child and her mother remarried. She was brought up by the Su (蘇) family who treated her as their own daughter. When she grew older, the Su family fell on hard times and she was sold to a brothel in Wu-hsi. Ya-yün was very clever, she was taught to sing, her voice always meandered to touch the heart. She was also proficient in string instruments. A man from Anhui called Wang Wu (汪五) paid a ransom to release her and took her with him to Shanghai. Ya-yün observed that he was narrow-minded and shallow and did not wish to follow him for long. She was later lured and sold by a woman to Tientsin and fell again into a degenerate environment against her will. She is good looking and tall with long eyebrows as if they were painted. Her character is sincere and trustworthy. She always speaks her mind and does not conceal her feelings. As she is not crafty, even though she has worked for a number of years, she is unable to accumulate wealth like the other courtesans who do so by being calculating.

Since I had been thinking of ending my relationship with Ch’i-hsiang (奇香), it so happened that Ya-yün came along with my young friend Ch’in (琴) to the guesthouse for chit-chat. I was impressed the moment I saw her, and she also kept looking back at me, so I invited her to stay for a drink. When night fell, she left to return, and we stayed together. From then on, she came every day to make me laugh. Recently I returned to Hopeh Province, she visited me without intermission. My wife Mei-chen (梅真) just loved her too for she is natural and genuine, deserving sympathy and kindness. .…..

My teacher Ti-shan (Fang Ti-shan 方地山, original name Fang Erh-ch’ien 方爾謙 1873-1936) really like her simple unaffected nature and said that of all the courtesans he saw in the last five years, only Ya-yün could move him. He therefore picked the two characters ya (雅) and yün (雲) to compose a pair of calligraphy couplets as a gift for me. It reads:

White wine gush into three Han goblets (三雅),

Sing aloud to halt the coloured Imperial clouds (五雲).

Mei-chen and myself together composed a song titled A Cloud Fragment on Wu-shan Mountain (巫山一段雲) dedicated to Ya-yün. The lyrics are:

Dim light unveils the eyebrow curves,

Fragrance breezes the temple hair sweeps,

A slight frown a slight peek bid goodnight,

Reserved words brim with girlish charm.

Against the pillow a gold necklace rests,

Kingfisher hairpins piled on pulled over quilt.

Warm breeze and soft cotton stroke the maid,

Her turns and twists almost to steal my soul.

The lyrics were set to music and Ya-yün was taught to sing the song. Stroking the strings and clapping in rhythm, a clear evening spent in the company of wine. Remnants of snow embraced the balustrades, lingering cold separated by the windows, incense in the burner fizzling out, the jade wine cups filled again and again, eight to nine family members gathered in one room, and Ya-yün amid all reciprocated the joy of each other’s company. My teacher Ti-shan had earlier written me a pair of calligraphy couplets with these words:

Major Court Hymns is now long gone,

A solitary cloud has nowhere to rest.

The third word “cloud” (yün 雲) in the second line happens to be the same character yün (雲) as in the name of Ya-yün (雅雲). This is a curious coincidence, though a beautiful story too.”

At this point, the editor Chou Shou-chüan inserted an explanatory note:

“Ya-yün’s given name is Ch’i-ch’iung (棲瓊), and her image can be seen on the copperplate picture in the front page.”

This was her first public appearance. Note that “My teacher Ti-shan” refers to the pre-eminent modern master of the art of calligraphy couplets, Fang Erh-ch’ien (方爾謙 tzu Ti-shan 地山) who was both Yüan K’ei-wen’s teacher and a relative by marriage as his fourth daughter Fang Ken (方根 tzu Ch’u-kuan 初觀) was married to Yüan’s eldest son Chia-ku (家嘏 tzu Po-ch’ung 伯崇).

Portrait of Mei-chen, wife of Yüan K'ei-wen, puublished in Yü-hsi Hsin-pao Newspaper in 1920

In Volume 4 Issue 5 of The Half-Month Magazine published on 23 February in the following year, the sequel to Conversing While Listening to Drums and Drinking Wine chronicled that Ya-yün had left the brothel by then. Three thousand taels of gold was paid as ransom money with the help of K’ei-wen’s wife Liu Jan (劉姌 also known as Mei-chen 梅真) who sold her jewelry pieces. This is consistent with Cheng I-mei’s account and is likely to be the source of his information. The article also reveals that Ya-yün’s alias Ch'i Ch'iung was given by Fang Erh-ch’ien:

“After Ya-yün returned with me to Hopeh Province, we saw each other day and night, unwilling to part. She declined invitations from guests and did not respond to calls. Whenever she returned to see me, we would smoke opium together, she would prepare and serve meals, just like a family. I was unable to send her away, nor could I bear to reject her. With my insubstantial income I could not afford to keep her, nor repay the debt she owed. I could only sigh before her. My wife Mei-chen also loved her and sympathized with her situation. She suspected that she had the intention to stay with us permanently, so she probed her with questions. The words from Ya-yün were sincere and resolute, my wife subsequently sold her jewelry which were worth three thousand taels of gold, and secretly arranged the ransom to release her from the brothel. However, I was still unaware of this. One evening while I was reading in bed, Ya-yün suddenly appeared laughing and said to me:

‘I will be staying here for a long time.’

I thought she was joking and poked fun at her. She then spoke seriously:

‘Madam has provided the funds to pay off my debts, I will always belong to your family, why do you laugh?’

I was surprised to hear this and called for Mei-chen to ask her, who then confirmed that was indeed the case. I was moved to tears and could not find words to express myself. My teacher Ti-shan was also someone who appreciated Ya-yün. He said that she possessed the quality of exceptional artlessness and was happy that she followed me. He gave her the tzu name of Ch’i-ch’iung (棲瓊).”

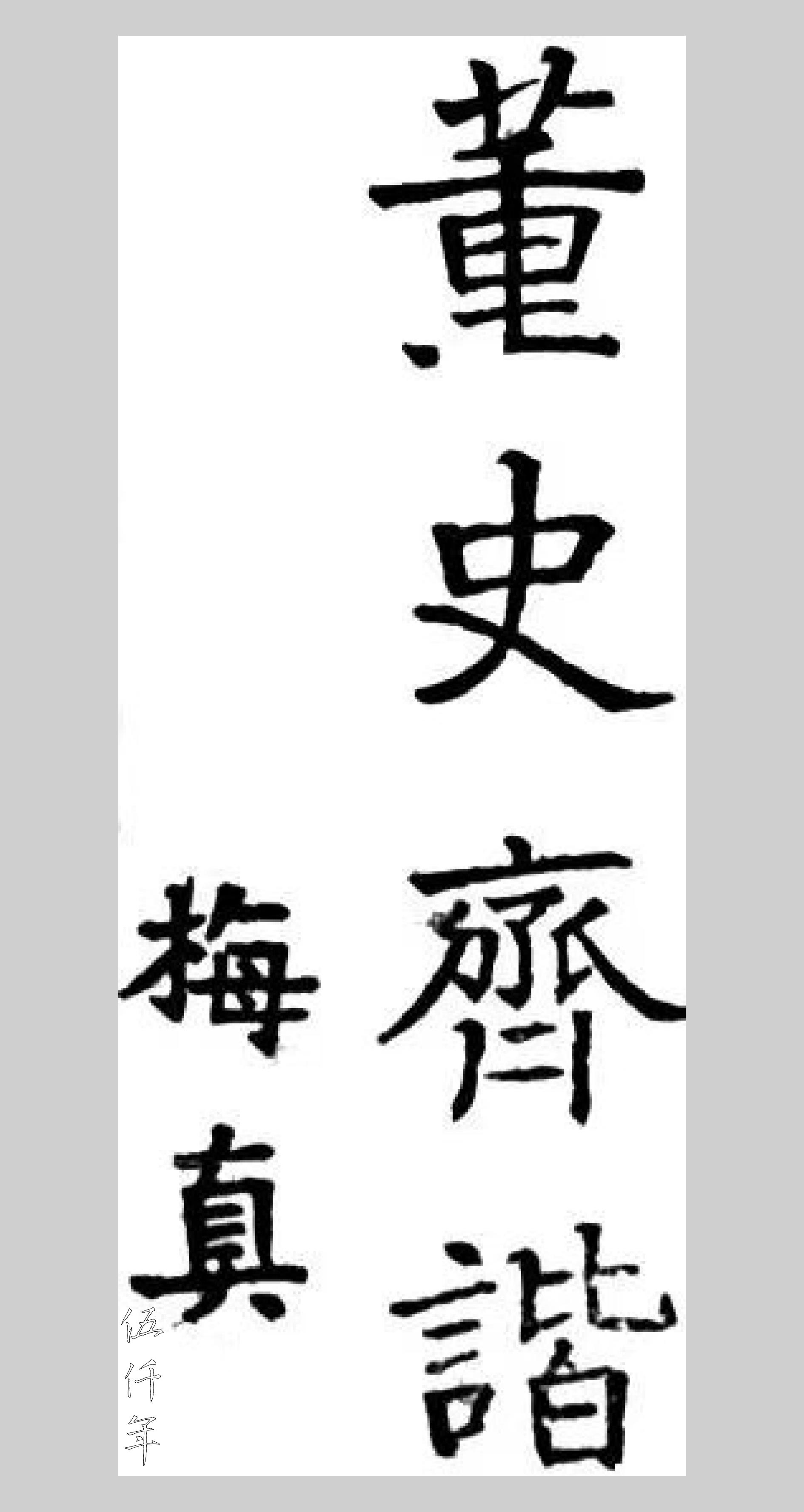

Considering this with the pair of calligraphy couplets published on 6 January 1925 in Ching Pao Newspaper (晶報) by Fang Erh-ch’ien titled A Congratulatory Message on the Joy of Han-yün, Mei-chen, and Ch’i-ch’iung Living Together (寒雲梅真與棲瓊同室之喜集成語賀之). The words of the pair of calligraphy couplets are:

Spirits brace in the boudoir,

Never tire in each other’s eyes

Gentlefolk grow old together,

Living and sharing in full candour.

These lines are a fitting description of the arrangement at the time. It is not difficult to work out the time when Yüan K’ei-wen met Ch’i-ch’iung, paid for her release and took her as a concubine. These all happened between the end of 1924 and early 1925.

Ching Pao Newspaper published a piece of calligraphy by Madame Mei-chen, original wife of Yüan K’ei-wen on 3 May in the 8th year of the Republic (1919)

In the first article in Conversing While Listening to Drums and Drinking Wine (聞鼙對酒譚), Yuan K’ei-wen emphasized:

“During the last ten years I acquired a reputation of fickleness with women. Altogether nine women followed me in succession, only two of them, Wu- ch’en (無塵) and Ch’i-ch’iung (棲瓊), were allowed to pay their respects at the ancestral shrine and were appointed minor wives…… I love Ch’i-ch’iung not only because her appearance and manners are close to Wu-ch’en, her gentle, respectful, soft and obliging demeanor is also similar.”

This illustrates that she was highly cherished at the time.

In late February 1925, while Yüan K’ei-wen was traveling from Tientsin to Peking, he wrote a five-character regulated poem for his newly-wedded minor wife, titled Presented to Mei-yün in the Car en Route to the Capital on 3 February, Spring in I-ch’ou Year (乙丑春二月三日入都車中示眉雲):

Crossing scores of cities the pheasant flies,

Capital’s splendour is reckoned nearby.

Mountain range blends the sluggish clouds,

Sparse smoke cordons the trees on slope.

So pleased a lady is traveling in this car,

Beside an itinerant with no fixed abode.

A scoop of water on a clear spring day,

Anxiously listening to the sunset flute.

The above poem is from Han-yün’s Poetic Papers (寒雲詩箋) in Volume 4 Issue 8 of The Half-Month Magazine published on 7 April 1925.

In April 1925, the novelist Pao T'ien-hsiao (包天笑 1876-1973) happened to be traveling to Peking. He commented on his encounter with Ya-yün (雅雲 also known as Ch’i-ch’iung 棲瓊) on the 14 April entry in Ch'uan-ying Lou Diaries (釧影樓日記):

“That evening, P’ei-feng (培風) hosted a banquet at Chung-hsin T’ang (忠信堂). Among the guests were Lu Hsiao-chia (盧小嘉) and others. Halfway through, I went to another banquet hosted by Fei Kung (飛公) at Ta-lu-ch’un (大陸春). Yüan K’ei-wen who had just arrived from Tientsin was also present. K’ei-wen was staying at the Sian Hotel, and after dinner, I went to Sian and saw K’ei-wen’s concubine named Ya-yün who appeared lively and unrestrained. She is probably difficult to handle. (K’ei-wen changed her name from Ya-yün to Ch'i-ch’iung 棲瓊).”

In Pictorial Shanghai (上海畫報) published on 6 July 1925, a photograph titled Portrait of Yüan Han-yün (K’ei-wen) and Yüan Su Ch’i-ch’iung (袁寒雲、袁蘇棲瓊合影) was published. The photograph was trimmed into a heart shape. Around it an artist added the drawing of a Cupid holding an arrow with both hands to congratulate the newlyweds.

Issue 11 of Pictorial Shanghai published a photograph titled: Joint Portrait of Yüan Han-yün and Yüan Su Ch’i-ch’iung

A careful reader may question whether the author made a mistake by quoting the poem Presented to Mei-yün in the Car en Route to the Capital on 3 February, Spring in I-ch’ou Year since the new concubine Yüan K’ei-wen married was Ya-yün (tzu Ch’i-Ch’iung 棲瓊). How did the name become Mei-yün (眉雲)? Let us look at Issue 135 of Pictorial Shanghai published on 27 July 1926, where there is photograph with an inscription by Yuan K’ei-wen with the words: Image of Mei-yün at the Age of Twenty One.

Issue 135 of Pictorial Shanghai published a photograph of Mei-yün inscribed by Yüan K’ei-wen

The same photograph was published on 27 October in the same year in The Pei-Yang Pictorial News (北洋畫報). The plate is finer and the details clearer. The female figure in the photograph is obviously the same person as in the previous two photographs.

Reading A Brief Biography of Madame Mei-yün (眉雲夫人小史) by T’ien-chien (天健) (published in Hsi Pao Newspaper 錫報 on 23 and 24 January in 1927), more can be learned about this lady’s life story. Some incidents match those as described by Yüan K’ei-wen, while others differ quite a bit, especially the part when she escaped from the house of Wang Wu (汪五) . It is as theatrical as a scene from some drama series. Part of the article reads:

“……So who is Mei-yün really? She is Sai Chin-hua (賽金花), a courtesan from our city. Her original surname is Tsou (鄒), name San-pao (三寶), born in Hua-shu (華墅). She entered the brothel at the age of twelve. In February of the year she turned seventeen, a merchant with a big belly named Wang Wu (汪五), who was twenty seven years old, the same age when Su Lao-ch’üan (蘇老泉) started studying, travelled to Wu-hsi for pleasure. He saw Sai Chin-hua at a drinking establishment, fell in love with her at first sight, and wanted to keep her as his mistress. Subsequently she was taken by the philistine. It was rumored that he paid two to three thousand taels of gold. After acquiring her, Wang took Chin-hua with him to Shanghai and lodged at the Great Eastern Hotel (大東旅社). Wang is a native of Anhui Province and runs a pawnshop. He is suspicious by nature and unkind. Chin-hua suffered much unhappiness. She once invited her brother-in-law Hsü Meng-yüan (徐孟淵) and her fifth elder sister to her lodging for chit-chat. This happened to be seen by Wang who became suspicious. When they quarreled, he threatened her with a pistol. Chin-hua could only blame herself for not finding the right man. She recognized that she was instead living with a brutal man. How could she stay for long? She secretly plotted with Wang’s chauffeur Chang Te-kuei (張得貴). A plan was hatched. Chang would take her to his aunt’s house the next morning to hide. He would return pretending to know nothing. He would then go to her brother-in-law’s house on behalf of Wang to search for her. After searching for her in Wu-hsi, he reported back hastily just to comply with his duty. Meantime, Wang also gave up the search. It turned out that Sai Chin-hua was married to Wang for only twelve days. Alas! Chin-hua can be regarded as someone good at escape.

After a month, Chin-hua was taken to Tientsin by Chang and his aunt, where she joined the Chung-hua Troupe (中華班) and changed her name to Ya-yün (雅雲). However, she was unable to advance her career and ended up owing one thousand and four hundred taels of gold. By then she had even used up the eight hundred taels of gold netted from selling a pair of diamond earrings she took when she fled from Wang Wu. After a year in Tientsin, Chin-hua was already eighteen years old. It was in this helpless period when Mr. Yüan K’ei-wen met her. He paid about seven to eight thousand taels of gold to release her and gave her the name Mei-yün (眉雲). Thus Madame Mei-yün’s name became famous at that time. By then she was already twenty-one years old. Mr. Yüan K’ei-wen only has Mei-yün as his single favoured concubine. Mei-yün circulates between his mother and his wife and is quite adored. I heard that Mr. Yüan has a new granddaughter. He will take Mei-yün back to Tientsin on the 16 of this month, and in February next year, she may return to Shanghai. As people hear her name but do not know her origin, I recount the short story of Mei-yün.”

Portrait of Yüan K’ei-wen and concubine Mei-yün taken in the 16th year of the Republic (1927)

Mr. Yüan K’ei-wen said that she was from Ch’ang-shu (常熟), which should be corrected to Hua-shu (華墅) in Wu-hsi (無錫), now part of Chiang-yin City (江陰市). He also said that she was abducted and sold in Tientsin: “She was later lured and sold by a woman in Tientsin”, while T’ien-chien (天健) provided a far more thrilling escape drama for the readers. Which version is true? Which version is false? Personally, I think the version of her active escape is more credible. As for the amount Yüan K’ei-wen paid to release her, it is reasonable to assume the sum to be three thousand taels of gold, “seven to eight thousand taels of gold” seems to be somewhat exaggerated. The key is T’ien-chien said Mei-yün was once called Ya-yün, which indirectly confirms that she and Ch’i-ch’iung were the same person. Furthermore, the phrase “from our city” (吾邑) in the first line of the text suggests that the author may be Ho T’ien-chien (賀天健 1891-1977), a Wu-hsi painter who often wrote for newspapers.

Hsi Pao Newspaper was founded by Chiang Che-ching (蔣哲卿) in October 1912. It was turned over to Wu Kuan-li (吳觀蠡) in 1917. The latter managed it well and the business thrived. With a firm base in Wu-hsi, it continued to extend its reach to various cities downstream of the Yangtze River. By 1927, the newspaper had successfully expanded its business to Shanghai by attracting writers from Shanghai to report on Wu-hsi, at the same time, with many Wu-hsi writers reporting on the anecdotes of celebrities connected to Shanghai.

In addition, there was another general newspaper in Wu-hsi called New Wu-hsi Newspaper (新無錫), which was second only to Hsi Pao Newspaper in terms of popularity. On page 4 of the 21 December 1926 publication, the newspaper revealed:

“K’ei-wen’s new favourite, named Mei-yün, is the younger sister of Hsin-cha-hua (新茶花). Her former tzu was Pai-yü-t'ung (White Jade Youngster 白玉童). At first she was fair and plump, but now she has slimmed down using a water diet and is slender and graceful with harmonious proportions.”

Following this track, a report can be found in the same newspaper on 30 September 1922, under the Flower and Moon Pavilion (花月樓) column:

“The courtesan Little A-yuan (小阿媛) has just come of age and knows of romance. Those who visit her boudoir view her as a most understanding woman. As the three words ‘Little A-yuan’ were considered quite elegant and pure, she was given the name Pai-yü-t'un (White Jade Youngster) by the madam.”

Indeed at the time, she was 17 years old in nominal age on the verge of adulthood.

Once it is known that Mei-yün was Ch’i-ch’iung, one can find many positive interactions between Yüan K’ei-wen and Mei-yün from reading The Han-yün Diaries. It is known that K’ei-wen wrote diaries for seven years, from chia-tzu year (甲子 1924) to keng-wu year (庚午 1930), a volume for each year. However only the two diaries from ping-yin year (丙寅 1926) and ting-mao year (丁卯 1927) have survived.

In the diary of ping-yin year (丙寅 1926), written according to the Chinese Lunar Calendar, the 14 January entry reads: “After Ch’i-ch’iung came from Peking”. K’ei-wen often took her out to watch movies, shopped in the markets, visited his teacher and friends, and when Yuan’s mother fell ill, she even prayed for her recovery as described in the 9 April entry: “Concubine Ch’iung (瓊姬) prayed for mother’s recovery at T’ien-hou Temple (天后宮) and got a most propitious divination”.

She also kept in touch with her own family, for example, the 22 April entry: “The birth mother of Concubine Ch’iung, Mrs. Yu Kung (俞貢)” sent a letter from her home at Lo-po Bridge (羅蔔橋) in Hua-shu and K’ei-wen replied on her behalf. The 1 August entry: “Old Man Su (蘇叟) came to visit his daughter from Hua-shu”. The 3 August entry: “Sent off Old Man Su on his return journey to the south this morning”. The Old Man with the surname Su was Ch’i-ch’iung’s stepfather. The diary of pin-yin year ends on 22 September. As for my impression of the last few months, K’ei-wen seemed to be engrossed in collecting coins and stamps, their contents far exceed those of domestic pleasures.

In the diary of ting-mao year (1927), the name Mei-yün was used to replace the earlier name Ch’i-ch’iung. The name Mei-yün appeared more frequently at the beginning of the year, for example, 7 January of Chinese Lunar Calendar reads: “Sent a letter home on behalf of Mei-yün.” The 10 January entry: “This morning I left with Liu-liang (六良) for Chi-nan (濟南), Mei-yün bid farewell at the station.” “Arrived in Chi-nan in the evening, stayed at Chin-shui Hotel (金水旅館) for two nights, sent letter to Mei-yün.” The 15 January entry: “Received a letter from Mei-yün and replied to it.” The 21 January entry: “Mei-yün asked for a pair of calligraphy couplets.” The 7 February entry: “Composed lyric To the tune Yeh-fei-chiao (夜飛鵲) to be sent to Mei-yün.” The 9 February entry: “Sick while away from home, overwhelmed with worries, thinking of Mei-yün, composed lyric To the tune Pu-sa-man (菩薩蠻) to be sent to her.” In March, there was a sudden delay in mail delivery. The 8 March entry: “Received a letter from Mei-yün that was sent on 20, saying: ‘There should have been three letters but none arrived. Strange!”’ The 9 March entry: “Replied to Mei-yün’s letter, told Chu-ch’en (鑄臣) to mail it from Ch’ing-tao.” The 14 March entry: “Received a letter from Mei-yün, replied.” The 19 March entry: “Sent a poem Embracing the Quilt (擁衾) to Mei-yün.” The 22 March entry: “Received a letter from Mei Yun, replied.”

During this period, Yüan K’ei-wen came to Shanghai. He had affairs with Sheng-wan (聖婉) and Yu P’ei-wen 于佩文. He had a particularly close relationship with the latter, not long after, he was besotted enough to make her his concubine. She then became the last concubine of K’ei-wen.

This is why in the diary of ting-mao year, after writing the entry: “Received a letter from Mei-yün”, he did not respond with the phrase “Replied to it”. Instead there is a gap of many days before the entry: “Sent letter to Mei-yün.” Of course, he still kept in touch with her, for example on 23 June: “Painted pine and prunus on a chü-t’ou for Mei-yün, instructed T’ieh-chih (鐵芝) to make the engravings”. Chü-t’ou means a folding fan. T’ieh-chih’s surname was Chin (金), he was an expert seal engraver and a disciple of Yüan K’ei-wen. The 4 July entry: “Sent Lao Fan (老範) north”. The 26 June entry: “Lao Fan came back from Tientsin with letters and clothes of Mei-yün”. Lao Fan was probably Yüan’s servant. The 18 August entry: “Sent letter to Mei-yün, and entrusted Hung-hsiang (鴻翔) to bring the poem Night Sitting (夜坐)”. The 28 August entry: “Received letter from Mei-yün”.

For the diary of ting-mao year, even though the entries end on 5 October, they are filled with intimate interactions between Yüan K’ei-wen and Yu P’ei-wen (于佩文). One truly experiences “seeing the new love laugh, but not hearing the old love cry,” and cannot help but sigh for the sad fate of Mei-yün.

Portrait of Yüan K'ei-wen and concubine Mei-yün published in Issue 198 of Pictorial Shanghai in 1926

The missing parts of the diary can be supplemented by newspaper reporting during that time. Towards the end of 1926, K’ei-wen and Mei-yün travelled south, and a birthday party was held for Mei-yün at the Far Eastern Hotel (上海遠東飯店) in Shanghai where they stayed. On 30 December 1926 in Hsiao-jih Pao Newspaper (小日報), Shu-liu (漱六 original name Chang Ch’un-fan 張春帆) wrote a piece titled Madame Mei-yün’s Birthday (眉雲夫人生辰):

“Yesterday (28), the reporter was invited by K’ei-wen to feast at the Far Eastern Hotel, and arrived in time to see the brilliant double decorative candles and the scarlet birthday banner hanging high on the wall. The occasion was his wife Mei-yün's birthday. There were many male guests in the room, as well as more than ten female guests. There was Ta-ku singing (大鼓), Su-t'an singing (蘇灘), magic tricks and games for the entertainment of the guests.”

Also on 4 January 1927 in Issue 189 of Pictorial Shanghai (上海畫報), Pu Lin-wu (步林屋) wrote a piece titled Mei-yün’s Birthday:

“The birthday of brother K’ei-wen’s minor wife Mei-yün’s was on November 24. His students and disciples pooled funds for the banquet to celebrate. I composed a poem on the spot:

Immortal peach offered in spring boudoir,

Lotus flower belongs to winter days too.

Fine curtains shade the disciples’ seats,

Princely mansion with vermilion gate.

Graceful talents kindred friends,

Music to render this splendid night.

Likewise I have come to pay my homage,

Poem now done and the drinking goes on.”

Note that 24 November 1926 of the Chinese Lunar Calendar corresponds to 28 December of the Gregorian Calendar.

By chance, I came across a short piece published on 6 March 1928 in a minor Shanghai newspaper called Da Pao (大報) founded by Hsu Lang-hsi (徐朗西) and Pu Lin-wu (步林屋). It was titled To Leave the Hall (下堂) by Lin-wu Shan-jen (林屋山人 also known as Pu Chang-wu 步章五) which includes a poem as preface and annotations at the end:

“Brother Pao-ts’un (抱存 another tzu of Yüan K’ei-wen) told me at a banquet that his concubine Ch’i-ch’iung had been given the ‘hsia-t’ang’ notice, literary meaning ‘to leave the hall’, sent away to be separated. I therefore assembled a few lines to form a poem:

Drink up for the sake of here and now,

Fallen petals like water soon turns to nowt.

When a radiant tree is thought to be daily seen,

a day will be ushered into the parting of old.

When Brother Pao-ts’un sent away Concubine T’ang, I also composed a poem. Each line is composed of seven characters. The beginning lines are:

The peacock lingers,

Orioles fly in disarray,

Inside the bridal chamber,

Petals fall as red candles dim.

The last lines are:

Try garner those lyrics

On old rope and new silk,

Let others read them

From back to forth.

Now that my brother lives in Shanghai, there will be new silk sheets- some current and some future. I wonder whether hearing of these past events makes one question what love is.”

This shows that by early 1928, the relationship between Yüan K’ei-wen and Mei-yün had become irreparable. “Concubine T’ang” refers to T’ang Chih-chün. The phrase “what love is” seems to indicate that the writer Mr. Pu also had reservations about the fickle behaviour of Yüan K’ei-wen (tzu Pao Ts’un) in love relationships.

Issue 38 of Lien-i-chih-yu Magazine (聯益之友) published a pair of calligraphy couplets by Yüan K’ei-wen

At this point in writing, please allow me to reproduce another article titled The Story of Romance between Yün and Ying (雲鶯豔史), written by Kuo Yu-ching (郭宇鏡), published in Ching Pao Newspaper (晶報) on 12 April 1931, with the editor’s note omitted. Yuan’s heartlessness can be seen here:

“I have been busy in politics for decades. In the beginning I had some dealings with Hsiang-ch’eng (項城 hao of Yüan Shih-k’ai, father of K’ei-wen). Later I became friendly with K’ei-wen (Han-yün) and his brothers. So regarding the separation between K’ei-wen and Hsiao-ying-ying (小鶯鶯), I was in the midst of it and knew the situation well.

Initially, K’ei-wen was quite sincere in his affection towards Ying-ying. Ying-ying had gone through the trials and tribulations of life, and intended to settle down like a tired bird after a long flight. She certainly knew that K’ei-wen was not prosperous in his financial affairs, but considered that he was from a prestigious family and that as a beauty who found a worthy gentleman to spend her life with, she was content. However, she was aware of his fickleness, discarding the original spouses like pairs of old shoes, so she did not drop her guard. She thus required K’ei-wen to give her the status as what is commonly called “liang-t’ou-ta” (two main heads 兩頭大), equal status as the principal wife. K’ei-wen agreed, and they had an official wedding ceremony at Peking Hotel (北京飯店). The marriage contract was done on dragon and phoenix wedding stationery, handwritten by K’ei-wen himself.

Prior to the wedding, K’ei-wen’s original wife, Madame Mei-chen (梅真夫人), was already well acquainted with Ying-ying. She even personally delivered the wedding costume to Peking for the traditional wedding ceremony. Afterwards, K’ei-wen paid his respects to Ying-ying’s parents, addressed himself as the son-in-law, performed the kowtow ceremony, and the red wedding invitation also stated the same. At that time they lived at Peking Hotel, with all the expenses borne by Ying-ying. When Madame Mei-chen learned about this, she was rather unhappy about it. This caused her to distance herself from Ying-ying. K’ei-wen stayed in a room in Peking and was with Ying-ying’s family for about six months. At the time he depended on the complimentary income of five hundred and eighty dollars per month paid by Chung-yüan Coal Mining Company (中原煤礦公司). Later the payment was stopped with the outbreak of war, and Ying-ying had to shoulder all expenses.

In the 13th year of the Republic (1924), the Second Chihli-Fengtien War (第二次直奉戰爭) broke out between Chang Tso-lin (張作霖 1875-1928) and Wu P’ei-fu (吳佩孚 1874-1939). There was rumour that Tuan Ch’i-jui (段祺瑞 1865-1936) would resume power. K’ei-wen believed that he would be able to benefit from his old friendship with the Tuan (段) family. Ying-ying encouraged him so K’ei-wen travelled to Tientsin first. However after he arrived in Tientsin, the Peking-Mukden Railway service was halted. He stayed in Tientsin at the Hsi-lai Hotel (熙來飯店). At that time, I also happened to be staying there.

At first, K’ei-wen still spoke on the phone with Ying-ying five or six times a day, saying that as soon as the Railway managed to restart, he would return to Peking. As the prospect of travel was grim, he invited me to join him on a tour of local beauties. I introduced Ch’i-hsian-hsü (奇香許) to him, she is now the wife of Ku Tzu-i (顧子儀), and is under arrest in Tientsin in connection with the case of customs funds. K’ei-wen started dating her, later he ended the relationship because of her body odour. It happened that Brother Ch’in (琴) whom I know, visited Hsi-lai Hotel day and night. K’ei-wen asked him to select another one on his behalf. Hence Brother Ch'in introduced Mei-yün. Her face was thin and elegant. In order to keep her man, once she got K’ei-wen, she served him most attentively.

At the time, Madame Mei-chen also visited Hsi-lai Hotel every day. From then on, K’ei-wen gradually forgot about Ying-ying. At first, he planned to return to Peking together with me once the Railway restarted. However, when I was about to leave, Madame Mei-chen detained him with the reason that her mother was ill, so he did not depart. When I was about to leave, he still asked me to call Ying-ying after I arrived in Peking, to tell her that he would soon return. He adamantly requested me to keep his affair in Tientsin strictly confidential. It happened that Ying-ying’s elder sister Hsiao-hsiang (小香) came to Tientsin with her customer Sun Ti-san (孫棣三) and found out about Mei-yün. She then told her sister upon return. Ying-ying was recently pregnant and angry at K’ei-wen’s fickleness. She sent a letter and severely scolded him. She accused him of breaching their agreement. K’ei-wen ignored her and did not reply. I was in Peking for over two months. When I returned to Tientsin, I enquired about him from mutual friends and was told that he had taken Mei-yün back home. Mei-chen had funded several thousand taels of gold and Mei-yün was now installed as his concubine.

Soon after, K’ei-wen sent his old servant Meng-san (孟三) to Peking to collect his belongings from Ying-ying, such as his collection of antique coins. They were all packed and taken in a sac. Meng-san spoke to Ying-ying insolently, friends at the time such as Li Tsu-tsai (李組材), Kuo Pao-shu (郭寶書) and others were all dissatisfied with K’ei-wen’s behaviour. Ying-ying calculated that she had spent nearly eight thousand taels of gold for K’ei-wen. Many counselled that she should take the case to court. She appointed T'ang Yen (唐演) as her lawyer. Ying-ying later gave birth to a daughter, who is now known as San-mao (三毛). As time went by, her anger subsided somewhat and the lawsuit eventually died down, but the wedding certificates and invitations are still with the lawyer T’ang Yen till today.”

Portrait of Yüan K’ei-wen

This article appeared shortly after Yuan K’ei-wen’s death. Hsiao-ying-ying’s real name was Chu Yüeh-chen (朱月真). Among Yuan K’ei-wen’s concubines her ranking was somewhere between T'ang Chih-chün and Mei-yün. The name of her daughter San-mao is Yuan Chia-hua (袁家華). The sentence “K’ei-wen sent his old servant Meng-san to Peking” matches the entry in the ting-mao diary: “Sent Lao Fan (老範) north”. Most likely Lao Fan was also later assigned to collect everything entrusted in Mei-yün’s residence in Tientsin to bring back to Shanghai. Frankly, there is no difference by nature in the misfortunes of T’ang Chih-chün, Hsiao-ying-ying and Mei-yün. It can also be seen that the concluding remark in Yuan K’ei-wen’s essay in Conversing While Listening to Drums and Drinking Wine, that: “The other concubines were either unwilling to remain as mere concubines, or unwilling to live a simple life, or were too unrestrained to observe discipline or too spoiled to be respectful, and therefore we could not remain happy together forever”, should not be taken seriously at all.

Finally, let us take a look at the final days of Mei-yün. On 21 February 1929, in Volume 6 Issue 283 of The Pei-Yang Pictorial News, a poem composed of five-character lines by K’ei-wen was published. It was titled Mei-yün is Seriously Ill So I Dragged Myself from My Sickbed to See Her (眉雲疾甚病中強起視之):

Fifty days since we last saw each other,

We meet again but I can’t tell it’s you.

Your bare bones have crumbled even more,

Nothing can be said apart from muted sobs.

My limpid spirit recalls days from the past,

Tears and mucus empty out my night.

Sighs are woven through dawn and dusk,

How so the year comes and swiftly leaves."

Chin Pao Newspaper published a photograph of Mei-yün at the age of twenty one on 16 October in the 15th year of the Republic (1926)

From the contents of the poem, it appears that Mei-yün was on the verge of dying. However, the editor's note states:

“K’ei-wen sent this manuscript before the Spring Festival, but due to the holidays the publication was delayed until now, and Madame Mei-yün had already passed away. Now with the publication of this manuscript, perhaps it will stir K’ei-wen’s remembrance of his bygone love?”

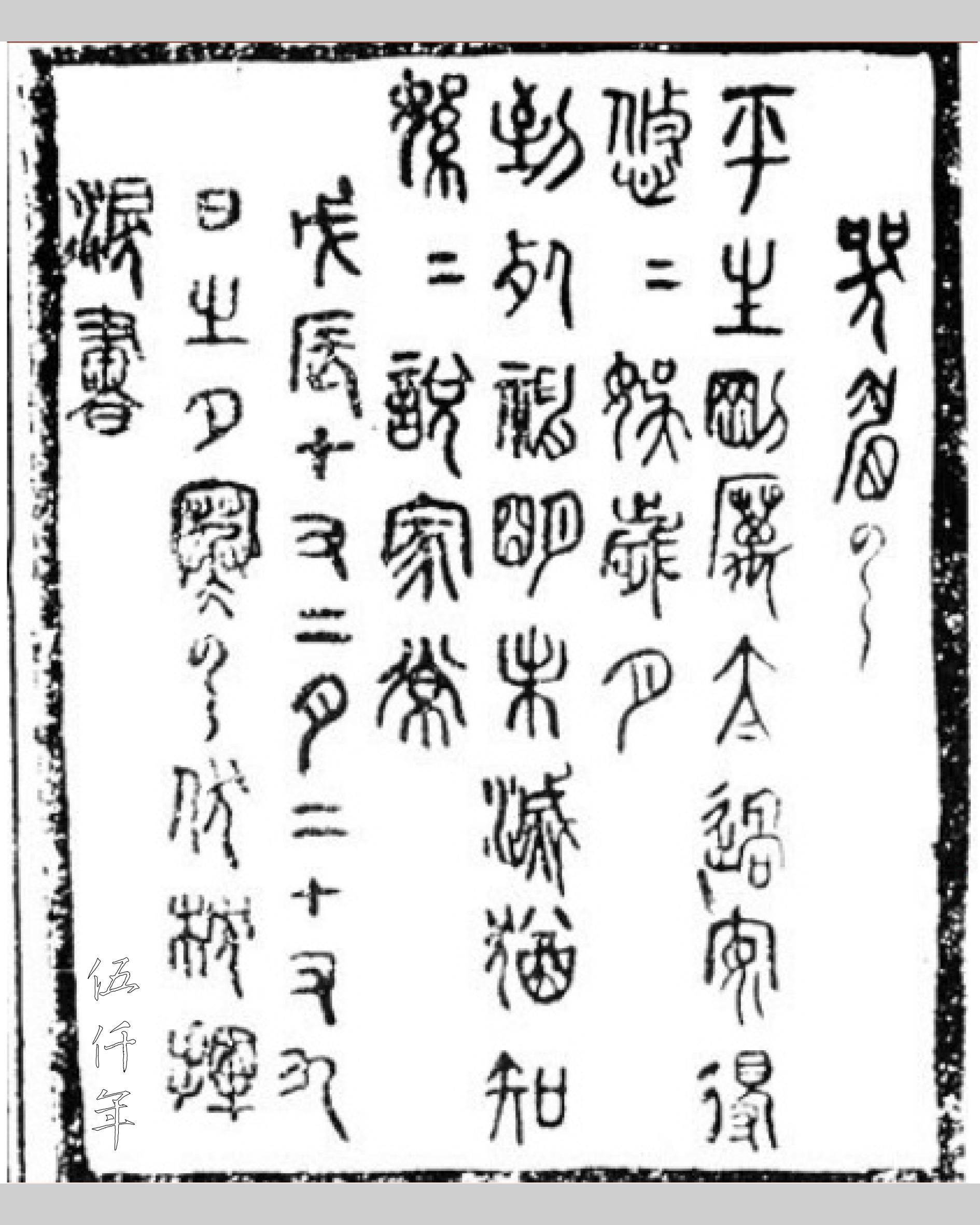

The Shanghai tabloid Ching Pao Newspaper was the first to publish an obituary. On 18 February 1929, it published an obituary written by Pao-feng (寶鳳 original name Yu Ta-hsiung余大雄) titled The Passing of Yuan Han-yün’s Wife:

“Yesterday, I received a letter by Mr. Yüan Han-yün (K’ei-wen) that was sent from Tientsin. A piece of paper with a pair of calligraphy couplets was enclosed. The title is Mourning Mei-yün. It reads:

I have been too tough and fierce in life,

How can I earn the ease of mellow years?

Her spirit did not extinguish before death,

She still made small talk on domestic life.

In the evening on 29 December of wu-ch’en year (戊辰1928), K’ei-wen prostrated on the pillow and wrote in tears.

Editor’s note: Madame Mei-yün was the beloved concubine of Young Master K’ei-wen, and her stories have been published many times in this paper. Although the Young Master subsequently took Madame P’ei-wen (佩文夫人) as his wife, his love for Mei-yün was as before. The Young Master had concubines in his life such as Su T’ai-ch’un (蘇台春), T’ang Chih-chün (唐志君), Hsiao-ying -ying (小鶯鶯) and others, a total of nine persons. All had been sent away one after the other. The only one to whom he was steadfast and who was allowed to enter the grounds of the ancestral shrine was Mei-yün. Madam was from Wu-hsi, the Young Master married her three years ago in Tientsin, and she served him to Shanghai. She loved to read this newspaper and used to urge him to write articles. It is indeed sorrowful.”

Chin Pao Newspaper published a piece of calligraphy couplets Mourning Mei-yün on 18 February in the 18th year of the Republic (1929)

Mei-yün died on 29 December of the Chinese Lunar Calendar in wu-ch’en year (戊辰 1928), corresponding to 8 February 1929 of the Gregorian calendar, only a year from being sent away to be separated. According to the first line of K’ei-wen’s poem “Fifty days since we last saw each other”, the two had met once towards the end of 1928. As for the statement in Yu Ta-hsiung’s article that Yuan K’ei-wen’s concubines were “a total of nine persons”, this is consistent with Yuan K’ei-wen’s article Conversing While Listening to Drums and Drinking Wine that “nine women followed me in succession.” However, the statement “the only one who was allowed to enter the grounds of the ancestral shrine was Mei-yün” seems to have omitted Wu Ch’en (無塵), based on Yüan K’ei-wen’s own words. Moreover wasn’t Hsiao-ying-ying (小鶯鶯) also officially married to Young Master Yüan and whose parents had met Yüan?

After Mei-yün died, Han-yün wrote two tz’u lyrics. They are:

To the tune Man-t’ing-fang (滿庭芳): Mourning Mei-yün. It was published in Volume 6 Issue 284 of The Pei-Yang Pictorial News in 1929:

I just bumped into

Early Spring.

Grief of death,

Hitherto strikes.

Ornate pavilion

Is now empty,

Calling your soul.

Latticed window

Wherein light glows,

Long to see

Furrowed eyebrows

Of yours.

To recall too

Your solicitude

Not too far.

Grief settling

In the infinitude

Of dusk.

On the road

We once travelled,

Fragrance fades,

Dreams end.

Is there somewhere

To run after

Idle trivia?

Still ever wearily,

I recollect

The rainy nights

Under a silken quilt.

Brocade drapes,

To linger

From dawn to dusk.

Laden helplessly

Over and over

With small talk.

So much to share,

But who will hear?

Albeit fortunes

Of next incarnation

Is unknown.

Just let me look after

The tenderness left

From evening dream.

Where we gaze at each other

A cosmic distance

Of Heaven and earth.

Desolate trees

Cover over

Your new grave.

To the tune Hao-nü-erh (好女兒): Inscribed on Mei-yün’s Posthumous Portrait. It was published in Volume 6 Issue 289 of The Pei-Yang Pictorial News in 1929:

For four years

We lean upon

Each other.

A couple of times

We ended up

Estranged.

Now seems

A silent parting

Forevermore.

I grieve the nights,

With dreams

All too short.

This damned life

Full of heartaches.

When will it be

For your soul

To come home?

All now left is to

Call for you

Call for you.

Bear I may see

Once more

Your old waistline.

Remember

The river shore,

That far corner,

Where we once met.

The idle garden,

In broad daylight.

That little pavilion,

In miserable rain.

And trees featured

By the rays

Of the setting sun.

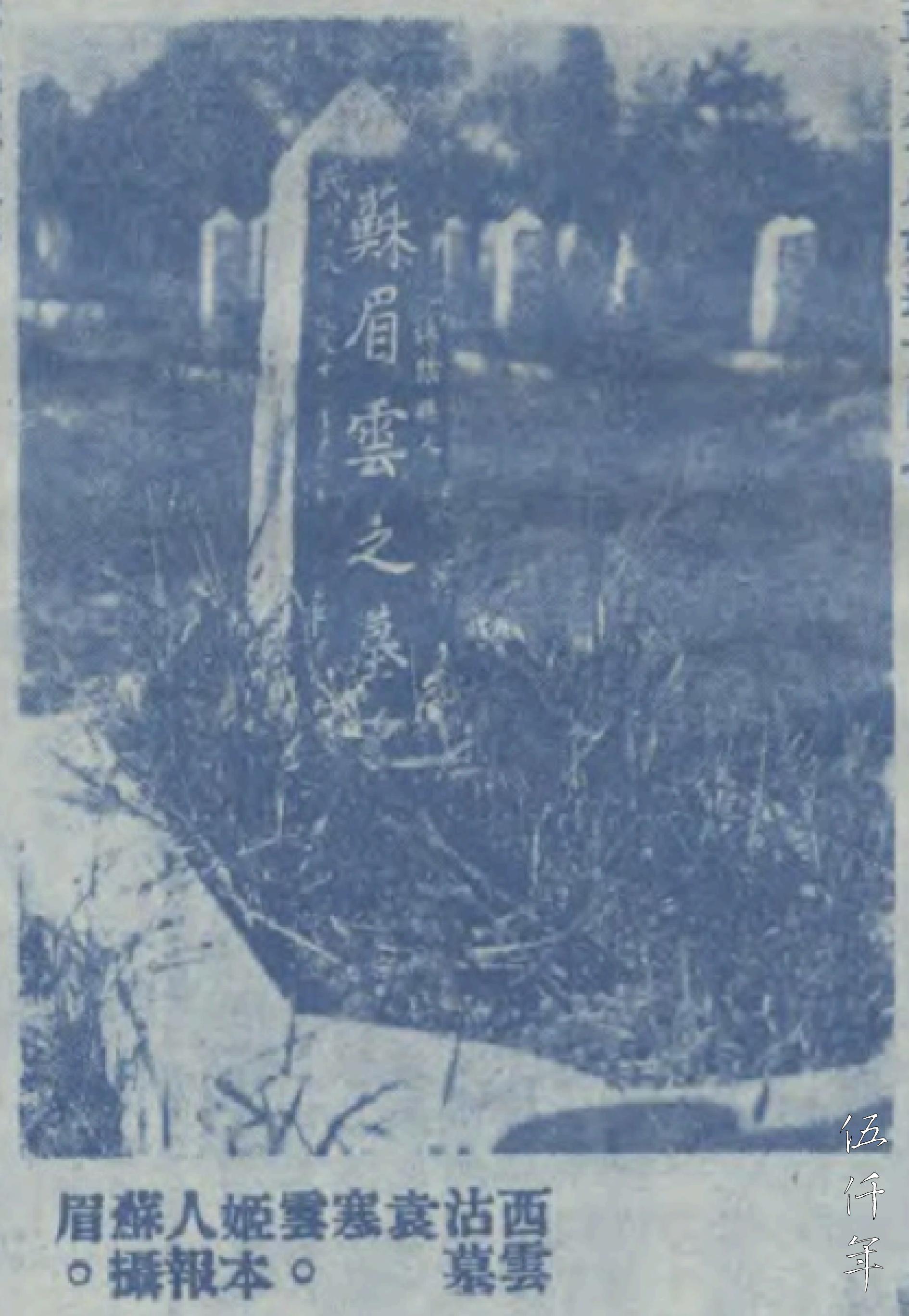

On 22 March 1931, Yüan K’ei-wen died from scarlet fever at the age of only forty one. On 3 November that year, in Volume 14 Issue 698 of The Pei Yang Pictorial News, a photograph was published titled Tomb of Yüan Han-yün’s Concubine-Su Mei-yün in West Tientsin. On the left is a pair of calligraphy couplets by K’ei-wen. It reads:

Past regrets and new thrills all come in view,

Gentlemen and ladies all adrift in the world.

At the bottom is an inscription by Fang Erh-ch’ien: “This is a commemorative couplet written for Mei-yün’s home return”. As the words printed in the newspaper are illegible, it is no longer possible to verify

Photograph of the tomb of Mei-yün, concubine of Yüan K’ei-wen, in West Tientsin

Related Contents:

A Folding Fan Gift by Ming-shih (名士)Yüan K’ei-wen to Seal Engraver Shou Hsi