Although Lu Hsiao-man (陸小曼 1903-1965) and Lin Hui-yin (林徽音 1904-1955), two talented women in the early Republican period, are popularly recognized, very few know of Lü Pi-ch'eng (呂碧城 1883-1943) nor Chou Lien-hsia (周鍊霞 1909-2000), tz'u poetresses in the same period. There are two reasons.

The husbands of the former two were renowned in literary and artistic circles. Their lives were conveniently used and magnified in movies, becoming commonplace romance stories. Even so, the painting of Lu Hsiao-man, the architecture of Lin Hui-yin, have still not received their due attention. As for the tz'u lyrics of Lü Pi-ch'eng and Chou Lien-hsia, they have few devotees at a time when Chinese Classical Culture is near to obliteration. Those who have heard their names, do not necessarily understand tz'u Iyrics. Furthermore, Lü Pi-ch'eng was unmarried and Chou Lien-hsia had a failed marriage. These are not attractive scenarios for a film director.

Lü Pi-ch'eng passed away on 24 January 1943. In January this coming year, it will be her 80th death anniversary. The historian Ms. P'an Hui-lien (潘惠蓮) wrote this article to describe current studies on Lü Pi-ch'eng, and to demonstrate that the journey of Classical Chinese Culture may not be so solitary.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

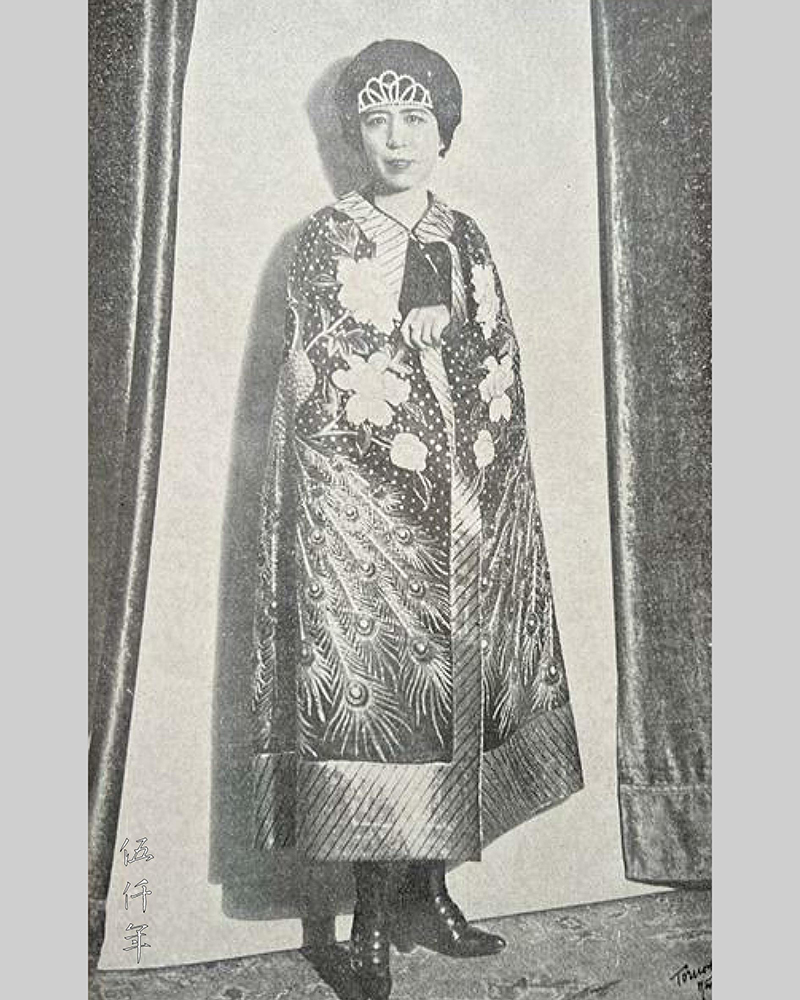

Portrait of Lü Pi-ch’eng in New York

To the tune Hsi ch’iu-hua (惜秋華)

After ten years,

Once more I return.

Places from the past,

Mournful as a dream.

Here a fairy crane

Comes swooping down.

Grief seeps slowly

Into the setting sun.

Faint memories of old,

Garden pond and house.

Autumn wind,

Human tragedies;

Hasten to disperse

Ancient scores and lyrics.

Recall our poetry games

With titles and rhymes.

So astounding your talent,

Fresh as from yesterday.

This is part of a tz’u lyric written by Lü Pi-ch’eng (呂碧城) in memory of her friend Fei Shu-wei (費樹蔚). She recalled they met and became close friends ten years ago, and her recollection was fresh as from yesterday. The first time this author wrote about Lü Pi-ch’eng has also been ten years in a flash. It was 2013, her 70th death anniversary. At that time, there was plenty of false information about Lü Pi-ch’eng on the internet. I searched her footprints in Hong Kong, and wrote to correct the misguided rumours.

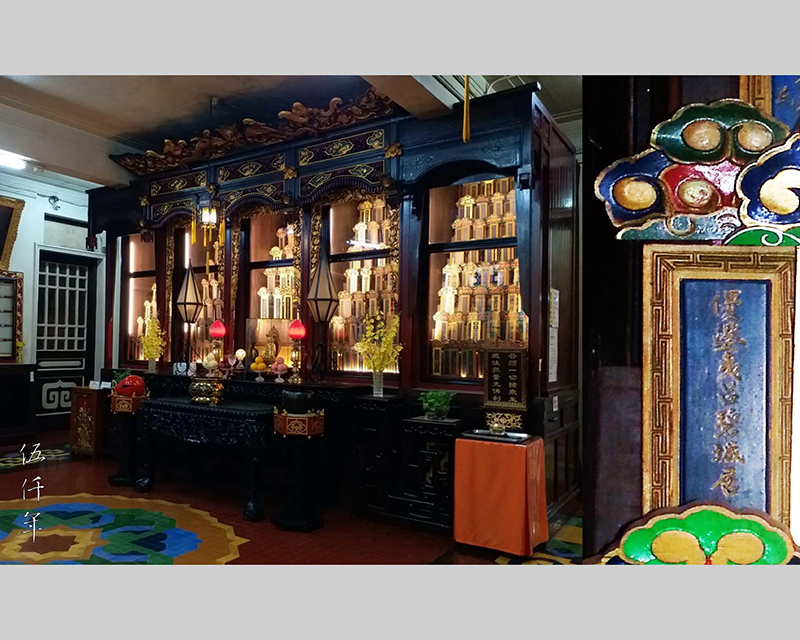

In the following ten years, studies on Lü Pi-ch’eng and public awareness of her have greatly advanced. Tung-lien-chüeh Yüan, the Buddhist temple where she stayed in her final years, is gradually opening up. Remembering ten years ago when I enquired at the Temple about Lü Pi-ch’eng, I was unexpectedly snubbed! Fortunately, the owner of the Temple Mr. Ho Hung-i (何鴻毅) is an open minded gentleman. I explained to him in an email the importance of studying Lü Pi-ch’eng. Shortly I was given a tour of the library at the temple to view the publications of Lü Pi-ch’eng, and saw her memorial tablet placed on the ancestral altar. On the tablet, there are eight Chinese characters: Yu-p’o-i Lü-Pi-ch’eng Chü-shih (Upasika Lü Pi-ch’eng). Yu-p’o-i is a word in Sanskrit, it means a female who adheres to Buddhism at home. Its Chinese translation is Chü-shih.

The spirit tablet of Lü Pi-ch’eng in Tung-lien-chüeh Yüan in Hong Kong

Afterwards, to promote better understanding, Tung-lien-chüeh Yüan regularly introduces the history of the Temple to the public and organizes tour groups to visit. In 2019, the Temple published Tung-lien-chüeh Yüan, The Buddhist Legend of Hong Kong. In the book, there was an account of Lü Pi-ch’eng in reference to my article.

Furthermore, the Hong Kong scholar Ms. Huang Hsiao-jung (黃小蓉), currently a lecturer at the Department of Chinese Language and Literature of The Chinese University of Hong Kong, published an article in 2015, titled The Synthesis of Literature and Buddhism: a Study on the Thoughts of Lü Pi-ch’eng in Her Later Life in Hong Kong. The article explores the deeds and thoughts of Lü Pi-ch’eng after 1935 when she was living in Hong Kong. It capsulizes her journey from the thrill of literary creations to the devotion to Buddhist studies. Special importance was paid to the period in Hong Kong before she passed away, and her thoughts prior to her death were analyzed.

In the studies by Ms. Huang Hsiao-yung, she pointed out that:

“Lü Pi-ch’eng composed fifty two tz’u lyrics in Hong Kong, one sixth of her total tz’u output. It is particularly worthy to note the tz’u lyric titled To the tune Che-ku tien (鷓鴣天) written in March 1937. Lü Pi-ch’eng revealed that she composed the last two lines of this lyric in a dream, and she completed this tz’u soon after waking up.

To the tune Che-ku t’ien (鷓鴣天)

Heart etched by myriad wounds,

As such life is cast.

Ask the Sorceress to no avail,

Sorrows of the past.

Floating clouds on summer days,

Motion and change.

Shadows press on mountain peak,

So hard to level.

Meditate on pattra,

Observe the sutras.

Let go of karma,

Into the cosmic void.

I have long disowned ancient ethics,

For the sake of vengeance.

Idle by me the Lung-ch’üan sword,

Whistling through the nights.

The last two lines bear a likeness to two similar lines in another tz’u lyric titled To the tune Che-ku tien by Ch’iu Chin (秋瑾). They are:

Tell me not that heroes aren’t from women stock,

On the wall nightly whistles the Lung-chüan sword.

Ch’iu Chin lived in late Ch’ing, a time of internal dissension and foreign aggression. She launched herself into the revolutionary cause. Her tz’u lamented the ruin of the country, and expressed the lofty aspiration of martyrdom. ‘The whistle of the Lung-chüan sword’ is indeed the cry when brandishing a sword for national revenge by a tz’u poet. While the lines by Lü Pi-ch’eng are:

I have long disowned ancient ethics,

For the sake of vengeance.

Idle by me the Lung-ch’üan sword,

Whistling through the nights.

In this tz’u lyric, Lü recalled the martyrdom of Ch’iu Chin, and conveyed her determination to ‘meditate on pattra, observe the Sutras’ in the midst of Japanese invasion and national calamity. Lü Pi-ch’eng knew Ch’iu Chin in Tientsin when they were young. At that time, Ch’iu Chin tried to persuade Lü to go to Japan and join the revolutionary movement. However Lü ‘held the view of cosmopolitanism. She was sympathetic to political reform and did not wish to segregate Manchus from ethnic Chinese.’ She eventually pledged to write for her friend’s cause from afar. Both aspired to relieve the sufferings of the world, but their methods were different. Lü Pi-ch’eng in later life still held the same youthful belief of saving the world through her writings. The difference was in her early years, she wrote for the cause of women’s rights and tried to pioneer public awareness, in her later years, she translated Buddhist Sutras and tried to preach Buddhism………Lü Pi-ch’eng dedicated herself to the study of Buddhism, she even used tz’u lyrics to propagate and annotate Buddhist teachings. This indicated that Lü did not study Buddhism for her personal practice nor to escape from worldly chaos, rather it was motivated by the wish to save all sentient beings, and embodied the spirit of practicing religion in the real world. This also indicated her later life characteristic of synthesizing literature and Buddhism in her literary endeavors.”

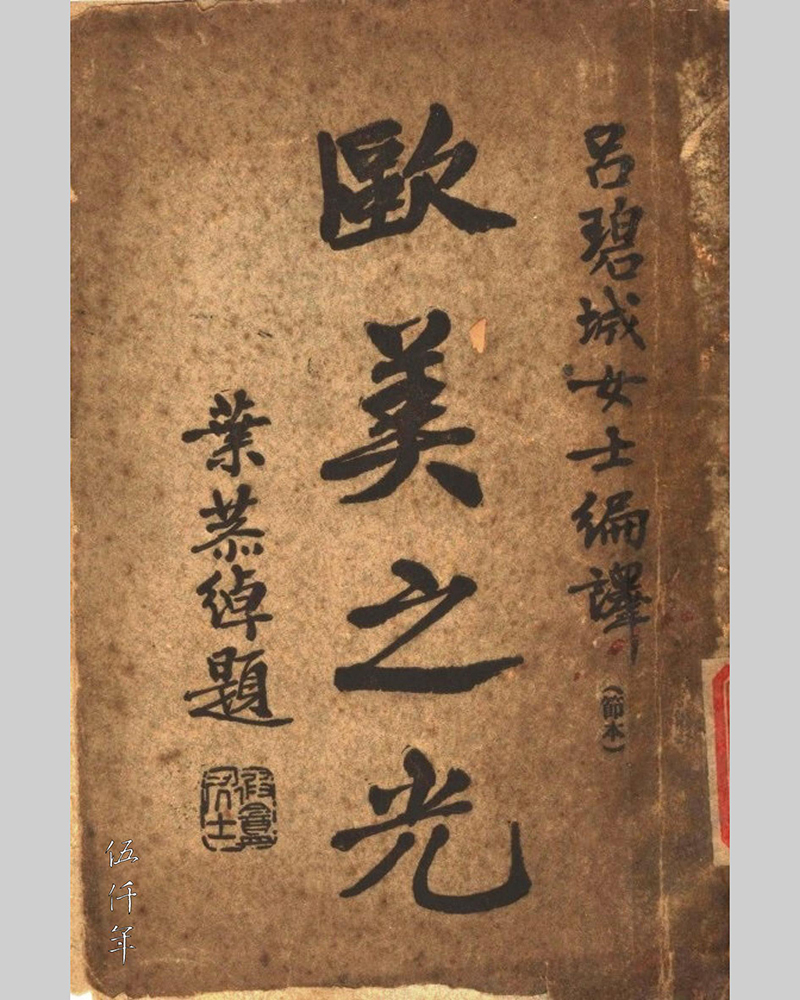

A researcher at the Academia Historica of the Republic of China, Ms. Lai Shu-ch’ing (賴淑卿), published a lengthy article in the March 2010 issue of the Academia Historica Journal, titled Introducing the Western Animal Protection Movement by Lü Pi-ch’eng, a Study of The Light of Europe and America. This was written from the perspective of animal protection. Ms. Lai pointed out:

“By participating in the American and European Animal Protection Movement, Lü Pi-ch’eng played the part of a cultural propagator. Regardless be it prose, poetry, tz’u lyric, movement against the killing of animals, promoting vegetarianism, translating Buddhist Sutras, they were all part of the spiritual journey of awareness and advancement, embarked upon by Lü Pi-ch’eng to understand human civilization. Consequently she also became a bridge between the Eastern and Western movements.”

The Light of Europe and America by Lü Pi-ch’eng

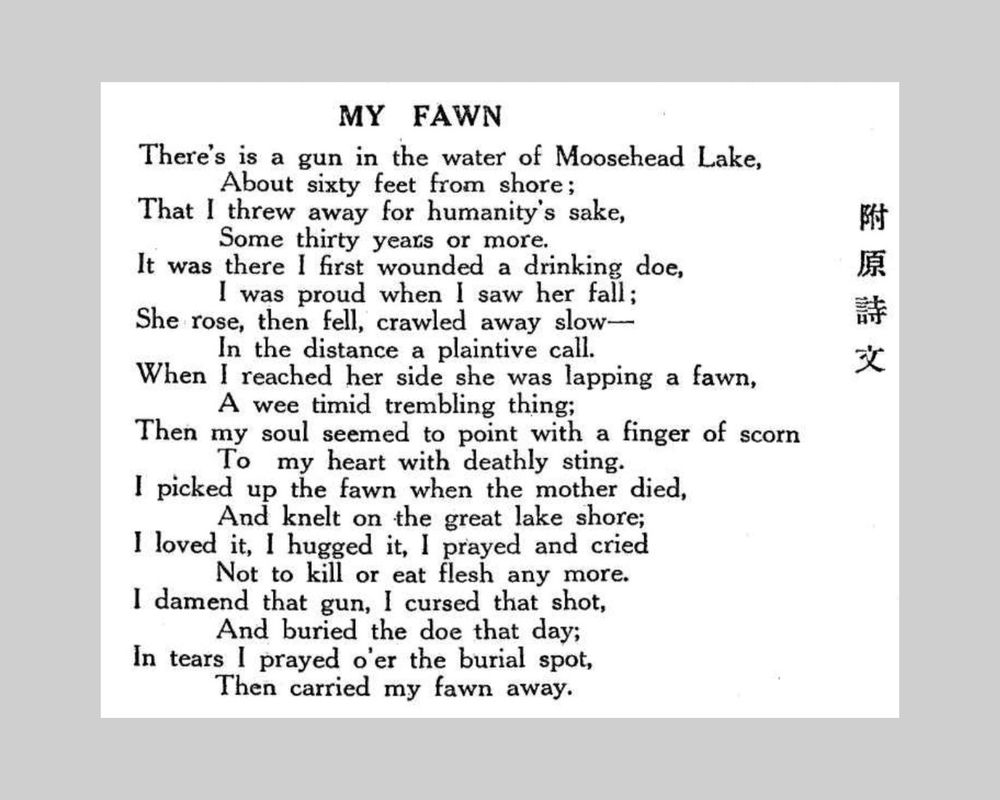

In her article, Ms. Lai mentioned that Lü translated a poem My Fawn by James J. McDonough into a Chinese classical poem with five character stanza. The poem is a criticism of the practice of blood sports.

Most recent publications only carried the Chinese translation of the poem. It is rare to see the original English poem. It is hereby reproduced.

My Fawn by James J. McDonough

In mainland China, the Shanghai Branch of Chung Hwa Book Co. published The Collected Works of Lü Pi-ch’eng in 2018. In collaboration with China’s Buddhist Academy of Mt. Putuo, a symposium on Lü Pi-cheng studies was held. Mr. Li Pao-min (李保民), a long time scholar of Lü Pi-ch’eng studies, and Ms. Grace S. Fong (方秀潔), a Canadian scholar of Chinese ancestry, were both invited.

In addition, Mr. Li Kuei-chih (李桂枝), pseudonym Tuan-mu Tz’u-hsiang (端木賜香) from Hunan Province, published In Search of the Real Lü Pi-ch’eng in 2020. The book used a wide array of sources, and approached the life of Lü with a new twist, while raising a number of queries and critiques. He claimed Lü was the first generation of wealthy women during the transitional period of China. Not only did she realize financial freedom and individual freedom, more so she attained personality freedom with a combination of her own global view, life view and value system. She almost achieved the rights of women in contemporary society.

As for my own search for the footprints of Lü Pi-ch’eng in Hong Kong, there are also some small progresses. I have found her home address in Hong Kong before leaving for Europe in 1937, and news of her arrival in Singapore. From her correspondences, it can be ascertained that she lived in Hong Kong from 1935 to 1937. She lived consecutively in two houses at No. 27 and No. 12 Shan Kwong Road, Happy Valley. In Autumn 1937, before she left Hong Kong, she sold the western villa at No. 12 and lived on the 4th Floor of P’u-t’i Ch’ang in Happy Valley, a Buddhist establishment. She then dispersed her belongings to friends. In November, she boarded an ocean liner to Singapore, her last long distance travel abroad. But where was P’u-t’i Ch’ang? No one knew. It was only known to be an establishment that promoted Pure Land Buddhism, and that it was managed by Master Chüeh-i (覺一), Master Fa-k’ei (筏可) and Master P’u-jen (普仁).

No. 37 Leighton Hill Road where Hsiang-hai P’u-t’i Ch’ang was formerly located

Eventually, I managed to discover the exact location of P’u-t’i Ch’ang in the 12 May 1935 copy of The K’ung Sheung Daily News. The address was No. 37 Leighton Hill Road in Happy Valley. This location is now known as Sheung Lan Mansion at No. 37 Leighton Road. It was a four storey building to the north of Shan Kwong Road, and its full name was Hsiang-hai P’u-t’i Ch’ang. Lü Pi-ch’eng could walk for twenty minutes from her No. 12 Shan Kwong Road property to reach P’u-t’i Ch’ang. It was officially opened on 26 August 1934, the Buddhist alter was located on the fourth floor, and free education was also offered there. After the war, the place became the campus of Sheung Lan Middle School in 1946. The founder of the school was Tseng Pi-shan (曾璧山 1895-1986), also a well known Buddhist female Chü-shih (Upasika).

In November 1937, Lü Pi-ch’eng bid farewell to P’u-t’i Ch’ang, and boarded an ocean liner from Kowloon to Singapore. She arrived in Singapore three days later. The local Nanyang Business Daily reported that she arrived to the port at seven in the morning on 22 November. The chairwoman of the Chinese Buddhist Association, Ms. Huang Tien-hsien (黃典閑 ?-1944) and others, greeted her in person. The newspaper reported that Lü was dressed in a suit, she was reluctant to meet the press, especially photojournalist. Huang Tien-hsien invited Lü to stay at a villa near Hung-ch’iao-t’ou. Lü revealed that she had been ill for a month, during this time she lost twenty five pounds, and her doctor advised her to rest. She would stay briefly in Penang before continuing onward to Europe.

Yet Europe was soon engulfed in war. After staying in Switzerland for three years, Lü Pi-ch’eng decided to go home. In the Autumn of 1940, she arrived in Hong Kong. Because of intense fightings in the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, she cancelled her plan to return to Shanghai. She sought refuge at Tung-lien-chüeh Yüan to translate the Sutras. She passed away on 24 January 1943 during the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, at the age of sixty. According to her will, her property was used for the promotion of Buddhism, her ashes was mixed with flour to make little pellets and thrown into the sea.

This year is the 80th Death Anniversary of Lü Pi-ch’eng. With the advancement of technology, the proliferation of the internet, it is much easier to search for information about Lü Pi-ch’eng. Regrettably, in the past ten years, many books and articles have appeared in the market and the internet that try to attract readers by sensationalism, endlessly hyping up fictional romances, or nonsensically claiming that Lü Pi-ch’eng, Chang Ai-ling (張愛玲), Hsiao Hung (蕭紅) and Shih P’ing-mei (石評梅) are the Four Talented Women of Early Republic. Even worse, photographs without credit nor verification are passed off as those of Lü, alleging them to be genuine, or computer techniques are used to create new images by pasting her face to other bodies in ch’i-p’ao (旗袍 Chinese dress for ladies), to be used for book covers. They spread through the internet, without concern for fact nor truth.

To transform human hearts towards goodness, how colossal is the task! Lü Pi-ch’eng once expressed her aspiration to preach Buddhism in a tz’u lyric. It reads:

Cloud of Mercy

Shield the sentient souls.

The Way is thus,

Birds, fish, animals and insects.

All born to bear

This sense of adrift.

Grasp the oars,

Ready to cross.

Together we land,

The shore beyond.

May the religious faith pursued by Lü Pi-ch’eng continue to radiate.

Portrait of Lü Pi-ch’eng in Switzerland

A Short Biography of Lü Pi-ch’eng (1883-1943)

Her original name was Hsien-hsi, later changed to Pi-ch’eng, also known as Lan-ch’ing, tzu Tun-fu, hao Ming-yin, later changed to Sheng-yin. In later life her hao was Pao-lien Chü-shih, her Buddhist name was Chih-man.

1883. She was born in T’ai-yüan, Shansi Province, but native of Ching-te, Anhwei Province. Her father attained the chin-shih degree in the Kuang-hsü reign and was appointed Provincial Education Commissioner of Shansi Province. She was born intelligent, gaining a reputation for her talent even as a child. Unfortunately, when she was thirteen, her father passed away. As there was no son, the family estate was seized by relatives. She had to move to Tientsin with the mother to seek refuge with an Uncle who held an official position.

1904. She was appointed editor of Ta-kung Pao Newspaper (大公報). She published a number of impassioned editorials, poems and tz’u lyrics. She advocated “Schools for women, education for women, rights for women as the foundation of a self strengthening country.” A large number of distinguished men and women fraternized with her, including Ch’iu Chin, who used the sobriquet Pi-ch’eng, a female revolutionary in Peking. Later that year, she was appointed head teacher of the P’ei-yang Women’s Normal School.

1912. She was appointed advisor to the President’s Office of Yüan Shih-kai, her position referred by some as secretary. She prepared herself to go abroad.

1918. She was ill and went to Hong Kong to recuperate.

1919. In September she arrived in the United States to attend Columbia University, studyingy art and literature. During this time, she was hired as a special correspondent for Shih Pao Newspaper (時報) in Shanghai, supplying her countrymen at home with news and stories of the United States.

1922. She returned to Shanghai and published Hsin-fang chi (信芳集) and translated A Brief History of the Founding of the United States (美利堅建國史綱).

1926. In Autumn she went abroad for the second time. She travelled to the United States and Europe.

1929. When she was staying in London, she diligently studied Buddhism. She began the life of vegetarianism, and supplied information regarding the protection of animals in different countries to her countrymen at home. Her work coincided with the movement against the killing of animals initiated by Master Hung-i (弘一大師), Feng Tzu-k’ai (豐子愷) and others. She tried to instigate the mood to protect life in Chinese society and to eliminate war as a consequence. In mid May, she accepted an invitation to speak for the Internationaler Tierschutz Kongress and attended their international conference in Vienna. The title of her speech was There Should be No Slaughter. She advocated the founding of an animal protection society in China and that on 4 October every year, it should be designated Animal Festival.

1933. She returned to Shanghai to focus on the translations of Buddhist Sutras and the publications of her own literary works.

1935. She relocated to Hong Kong and used it as a base for Buddhist studies. In the following three years, she visited friends in Canton, Shanghai and Nanking.

1937. After the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression broke out, she travelled abroad for the third time in November. She lived in Switzerland and continued to propagate Buddhism. Two years later, Europe was engulfed in war. She then decided to return.

1940. In Autumn she arrived in Hong Kong. She resided at Tung-lien-chüeh Yüan on Shan-kuang Road in Happy Valley to translate Buddhist Sutras.

1943. She passed away on 24 January, aged sixty. Her will was to distribute her property to promote Buddhism, and her ashes to be mixed with flour to make small pellets, to be thrown into the sea.

Portrait of Lü Pi-ch’eng in Vienna

Related Contents:

Lü Pi-ch’eng (呂碧城), Mother of the Animal Protection Movement in China