It is an accepted verdict in recent years that species are extinct because of humans. Many movements such as those against the hunting of rare species, against the trading of ivories and rhinoceros horns, against the wearing of furs, against the experimentation on animals, have thus proliferated in scores of countries. In particular, science has proven that many species have emotions, responsivenesses and sentiences similar to humans. The title of Mother of the Animal Protection Movement in China fittingly belongs to Ms. Lü Pi-ch’eng of the early Republic period. She was not just a tz’u poetress who wove enchanting sentences, she was also a zealous social activist. She used both Chinese and English languages to propagate the notion against the killing of animals in China and abroad, citing Buddhism and Confucianism for its intellectual foundation. On 24 January this year, it will be the 80th death anniversary of Lü Pi-ch’eng. At the Chinese-Heritage Virtual Museum, we exhibit some of her works to elucidate her compassionate ambition, and to evoke that all sentient beings are gifted with feelings, that mountains, forests, rivers and streams are equally their abodes.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

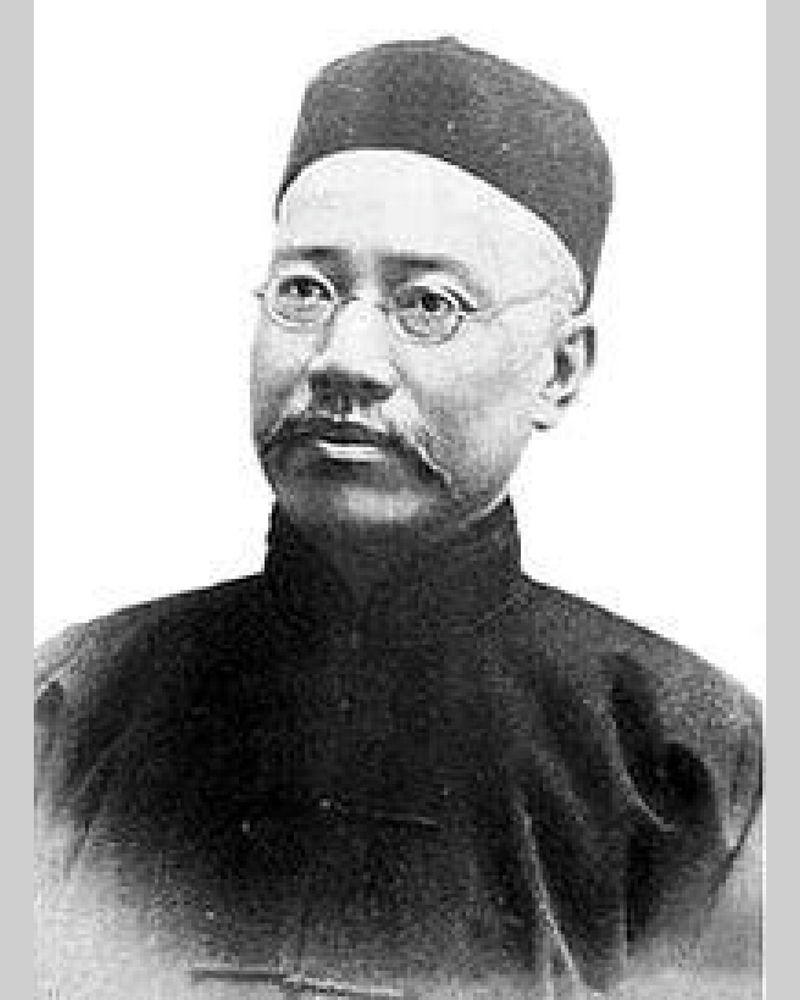

Portrait of Lü Pi-ch’eng in Vienna, 1929

Lü Pi-ch’eng (呂碧城) was born in the 9th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1883) and passed away on 24 January in the 32nd year of the Republic (1943). This year is her 80th death anniversary.

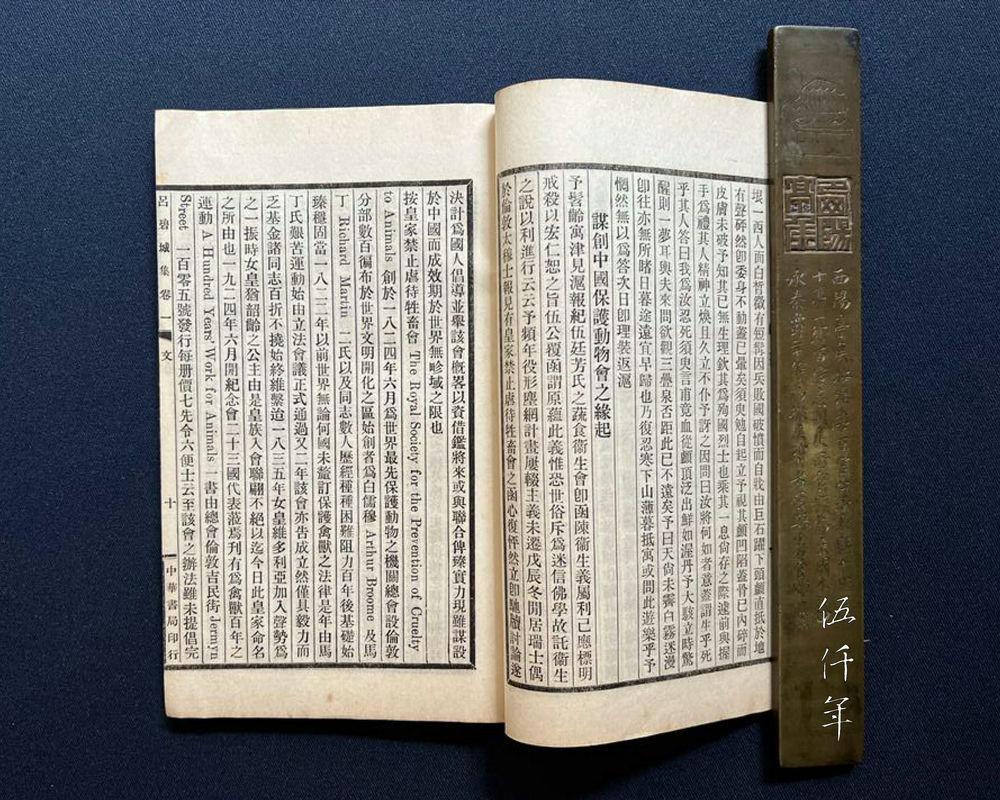

The article Proposition to Form an Animal Protection Society in China was published in Volume One of The Collected Works of Lü Pi-ch’eng in 1929

In the 17th year of the Republic (1928), Lü Pi-ch’eng at the age of forty six, propositioned to form an animal protection society in China. She wrote an article to broach this. Its first paragraph reads:

“In my youthful years while living in Tientsin, I read about the Vegetarian Hygiene Society formed by Wu Tingfang in a Shanghai newspaper. I immediately wrote to assert that hygiene was by nature self-serving, one should declare that abstinence from killing animals was to propagate the principles of benevolence and leniency. Mr. Wu replied in his letter:

‘This was the original idea. However, there was concern that common folks would denounce this as Buddhist superstition. Therefore hygiene was used as a pretext to facilitate its advocacy.’

I have been embroiled in the trials and tribulations of life for years. A number of times, my plans were put to an end. Yet my ideal has never budged. In the winter of wu-ch’en year (1928), during my idle sojourn in Switzerland, I came across a letter from The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in The Times Newspaper. My heart fluttered with excitement and I immediately wrote them a letter for discussion. Subsequently I was resolved to propagate my idealism to our countrymen, and to give a basic description of the Society as reference. Perhaps there will be future collaboration between Chinese and British organizations to build greater clout. Although the current plan is to set up an organization in China, the aspiration is to attain global influence without national constraints.”

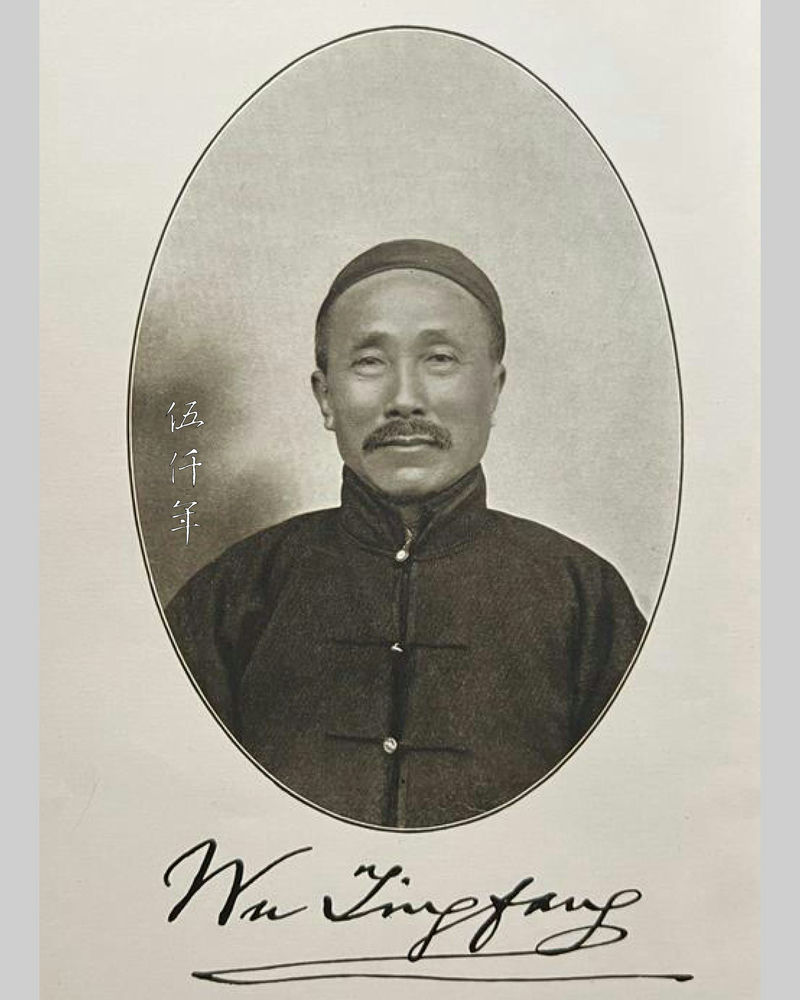

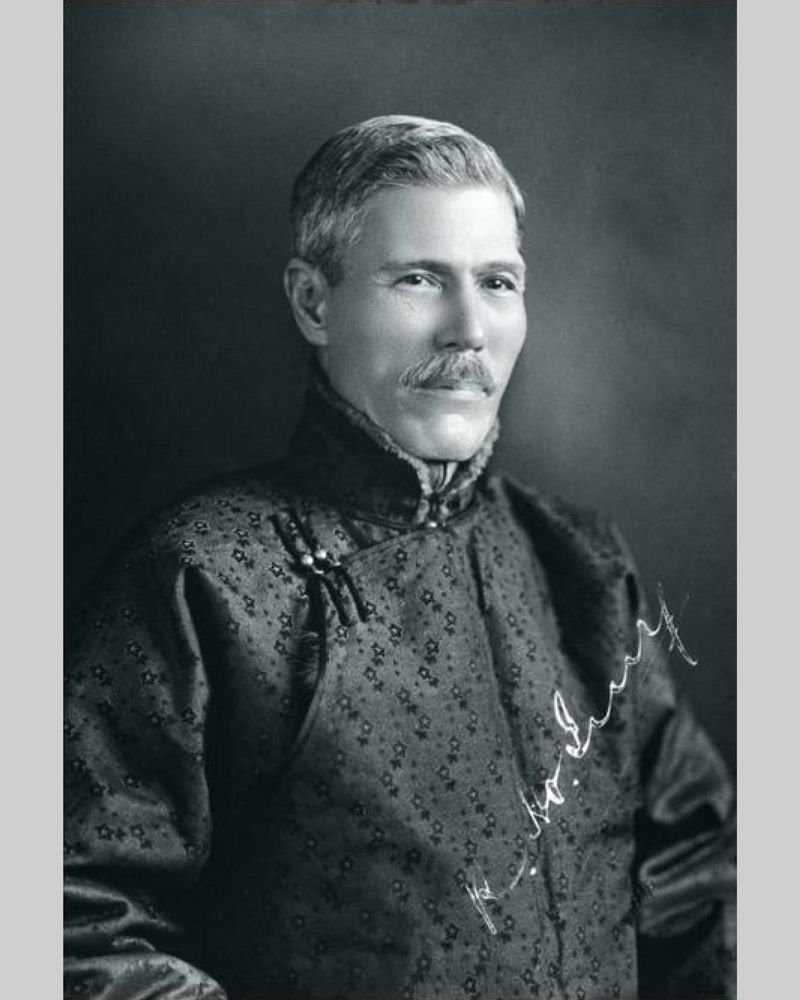

Portrait of Wu Tingfang

Wu Tingfang, ambassador to the United States, was a vegetarian for many years. In the 3rd year of the Republic (1914), he published America through the Spectacles of an Oriental Diplomat in New York. In the chapter Dinners, Banquets, Etc., Wu recounted that he introduced vegetarianism to Chinese and Occidentals he encountered, which was inspired by the book The Aristocracy of Health written by Mary Foote Henderson in 1904. As Lü Pi-ch’eng recalled writing a letter to Wu Tingfang when she was young, assuming Wu had formed the Vegetarian Hygiene Society in 1904, Lü was just twenty two. One realized that her compassionate nature was formed early in life, it did not sprout from her Buddhist faith later on during middle age.

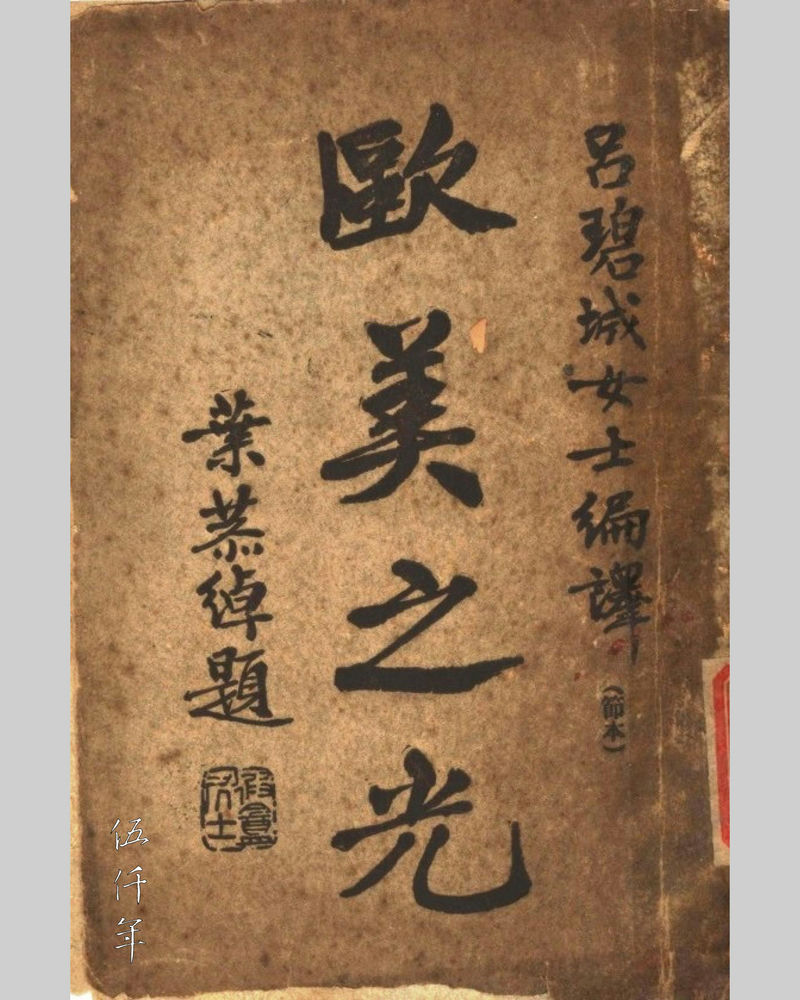

Front cover of The Light of Europe and America by Lü Pi-ch’eng

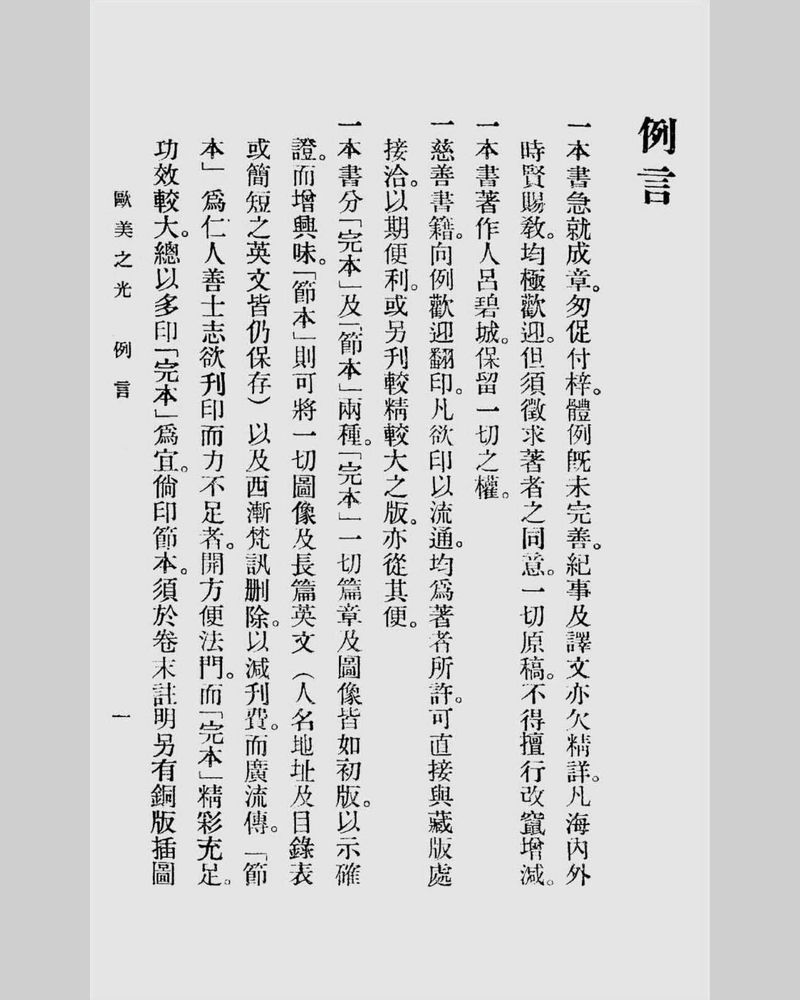

In August the 20th year of the Republic (1931), Lü Pi-ch’eng published The Light of Europe and America in Shanghai. It chronicled news about the vegetarian movement, the anti-vivisection movement, the animal protection movement and the Buddhist movement in Europe and America. In the beginning of the book, Lü wrote a list of Introductory Remarks. One of the Remarks reads:

“It is customary for charitable books to welcome reprints. Whenever there is intention to reprint the book for wider circulation, it is permitted by the author at all time. The person can contact the storage of the printing plates for less effort, or print it in finer details and larger format, whatever are the wishes.”

A list of six introductory remarks in The Light of Europe and America

Lü Pi-ch’eng regarded The Light of Europe and America to be a charitable act. Not only did she relinquish her copyright, she was also happy to assist in the printing process. The objective was to proliferate compassion and to convert the ethos of society. Lü was well aware in order to save the lives of sentient beings, it relied particularly on the incessant implementation of knowledge with action.

Further reading the Introductory Remarks, another Remark reads:

“Vast quantities of books and magazines on animal protection are published in Europe and America. This book on animal protection resembles the first shot of an arrow in East Asia. Although the first edition is not substantial, it can somehow be a trailblazer. The compassionate and the good can follow to undertake selected translations. Promotion will lead to realization, and resonance will be found with international civilization. We will not let other countries disdain and view us as unprogressive. Such are my sincere hopes.”

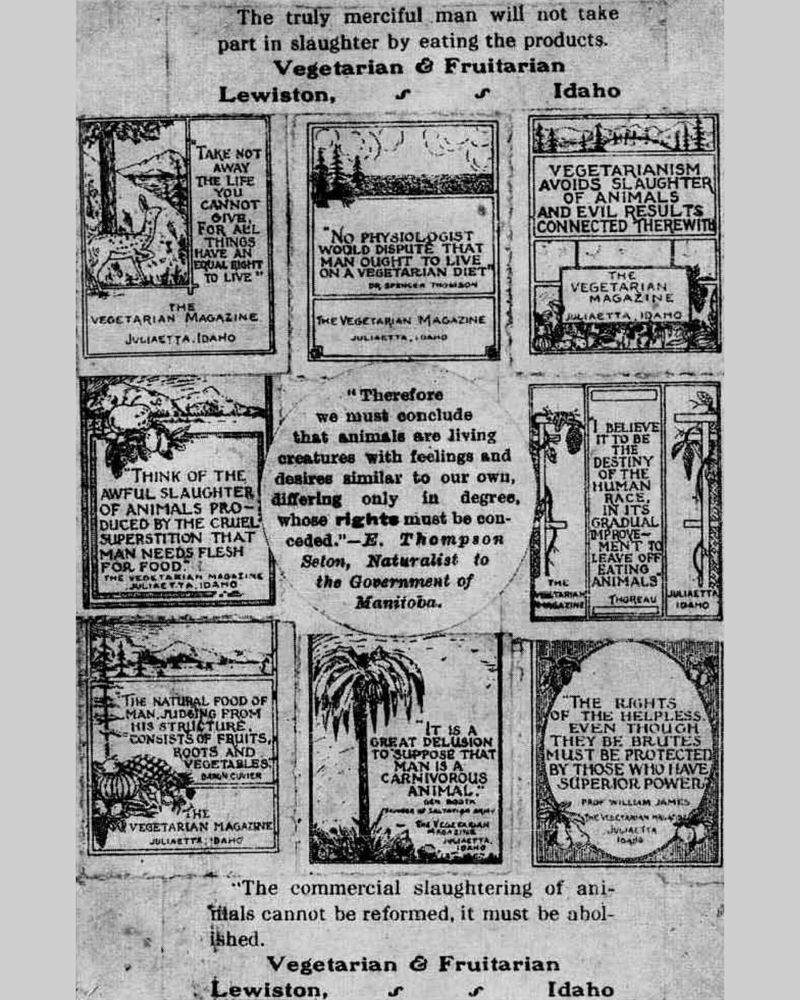

Pamphlets with slogans distributed by the American Vegetarian and Fruitarian Society and the Vegetarian Magazine

Lü Pi-ch’eng wished that The Light of Europe and America would be the first shot of an arrow in East Asia, a trailblazer in China. At that time, few Chinese held the notion of animal protection. The tortures and slaughters of animals could be observed everywhere. Even today, a hundred years down the road, they resemble destructive and unstoppable torrents. In the West, animal protection organizations were consecutively formed in the 19th century. To cite an example, The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was formed in 1824 in London, an occurrence two centuries ago! In the Classic of Poetry compiled by Confucius, there is a well known line : “The stone from another mountain can be used to make abrasive tool.” Lü Pi-cheng did not gloss over the use of Western humanitarianism to induce Chinese compassion. The Light of Europe and America introduced Western organizations dedicated to vegetarianism, anti-vivisection and animal protection for Chinese to refer and emulate. She also translated slogans from the American Vegetarian and Fruitarian Society and the Vegetarian Magazine; an appeal by German, Austrian, Swiss medical opponents to vivisection; speeches and articles by distinguished men and women in the West against the killings of animals. They were intended to arouse Chinese conscience.

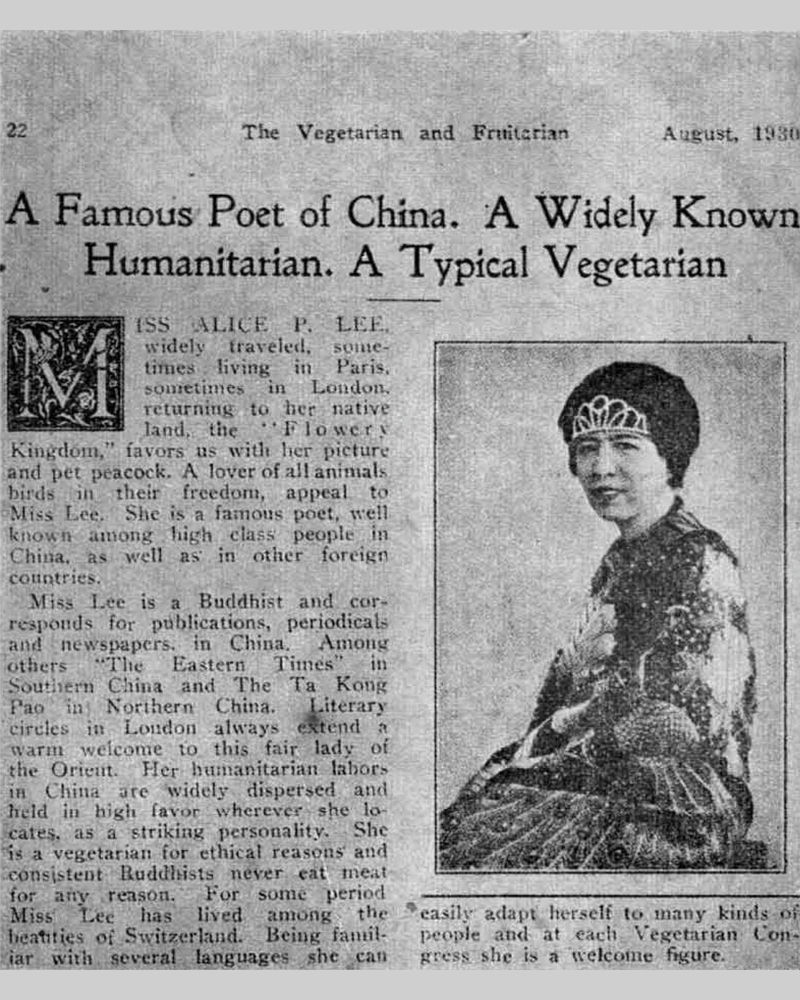

Article on Lü Pi-ch’eng in the August 1930 issue of the Vegetarian Magazine

What were the qualifications of Lü Pi-ch’eng to write this book? Apart from her proficiency in English, she lived in Europe for a long time, she was familiar with the realm of animal protection, and in particular she fraternized with the officers of such organizations. It was September in the 9th year of the Republic (1920) when Lü Pi-ch’eng first travelled abroad. She was thirty eight years old and went to the United States to study at Columbia University. She returned to China in the 11th year of the Republic (1922). Four years later, in September the 15th year of the Republic (1926), she travelled to the United States again, aged forty four. In April the following year, she visited Europe to tour France, Switzerland, Italy, Austria, Britain and Germany. From the 17th year of the Republic (1928) onwards, she settled in Switzerland. In winter the 22nd year of the Republic (1933), she returned to China at the age of fifty one. Five years later, in the 27th year of the Republic (1938), she went back to Switzerland, aged fifty six. After war broke out in Europe, she left for Hong Kong in the 29th year of the Republic (1940), where she spent her final days. Altogether Lü Pi-ch’eng lived abroad for a total of thirteen years.

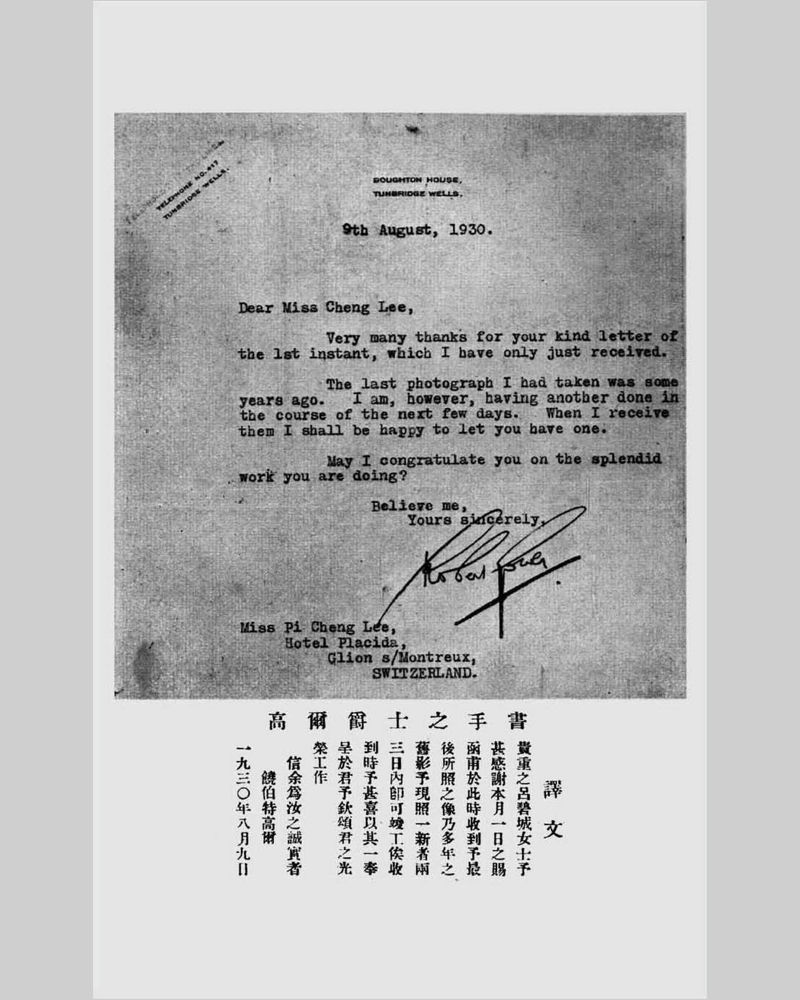

Letter to Lü Pi-ch’eng from Sir Robert Gower, British Member of Parliament and activist of animal welfare

During her sojourn in Europe, she corresponded with The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, The Abattoir Association of Chicago, World League Against Vivisection and for the Protection of Animals, The Vegetarian Society in Britain, The National Vegetarian Society in the United States, Nederlandsche Vereeniging tot Bescherming van Dieren in the Netherlands.

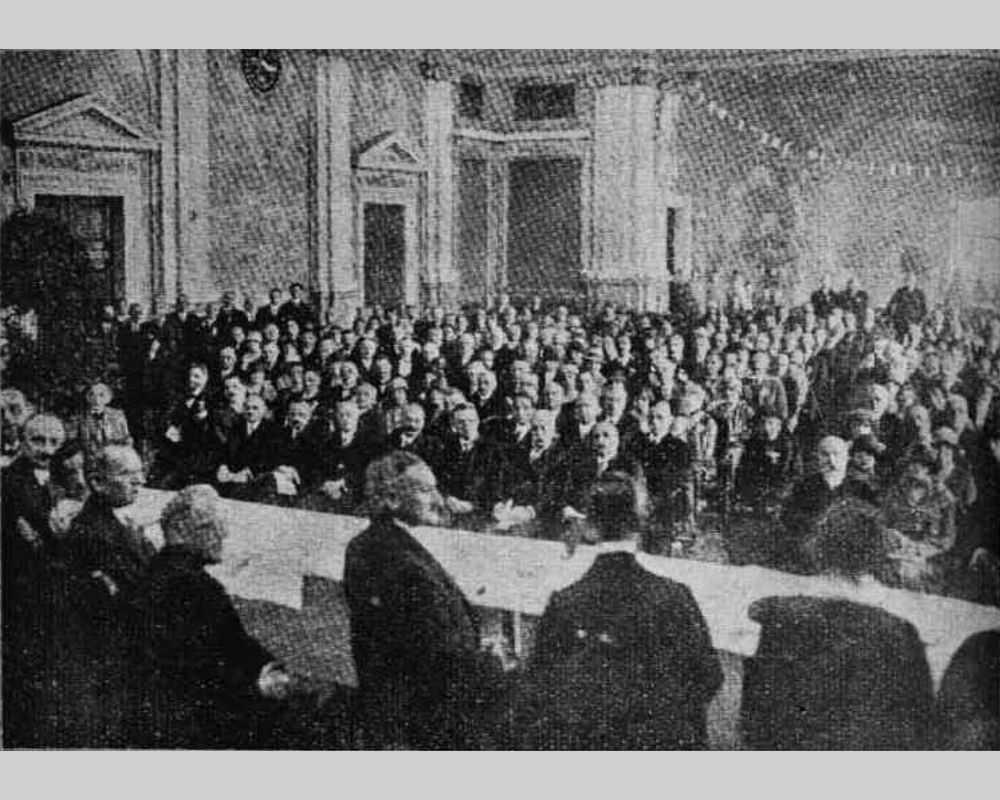

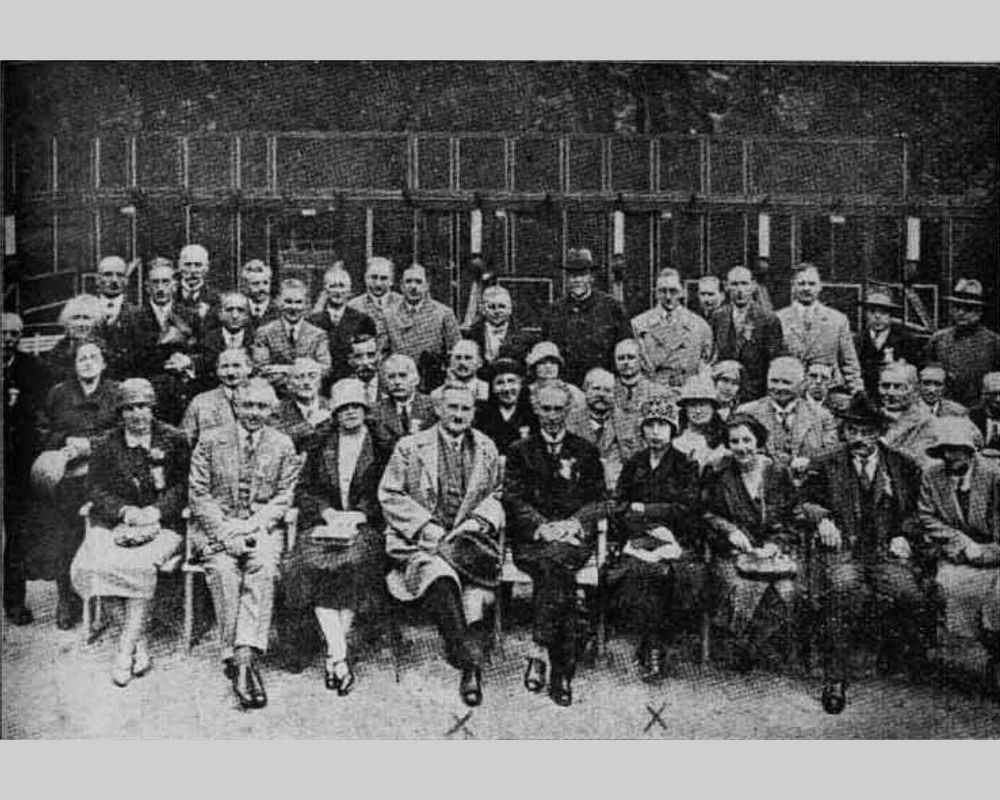

International conference organized by the Internationaler Tierschutz Kongress in Vienna, 1929

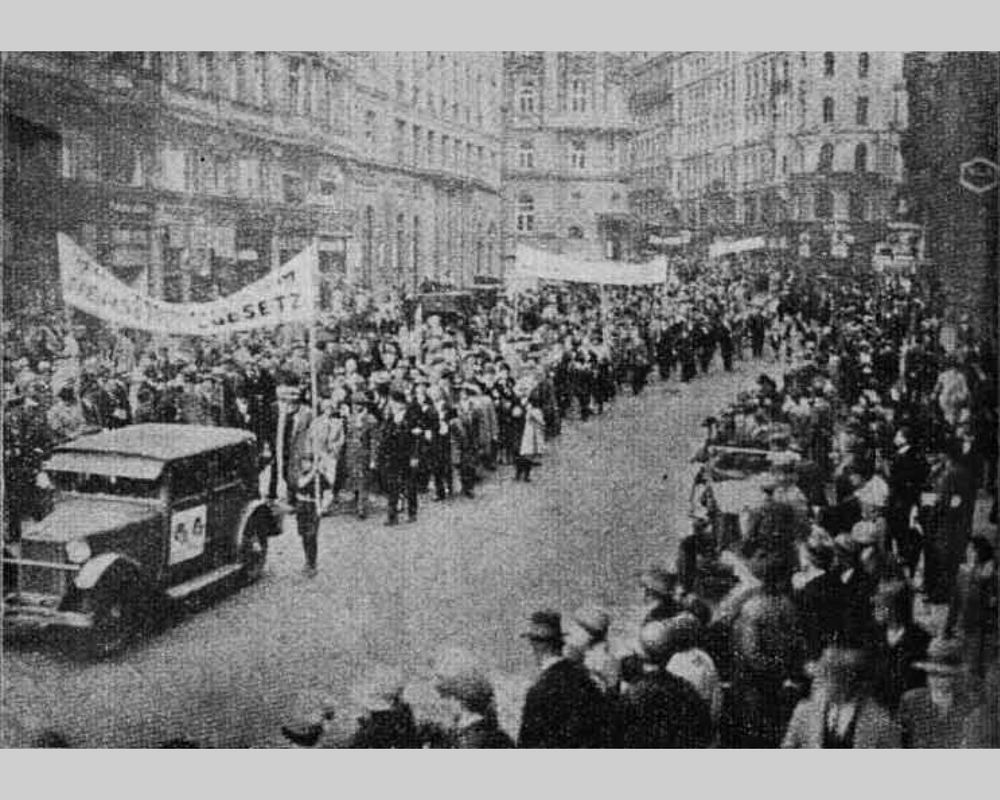

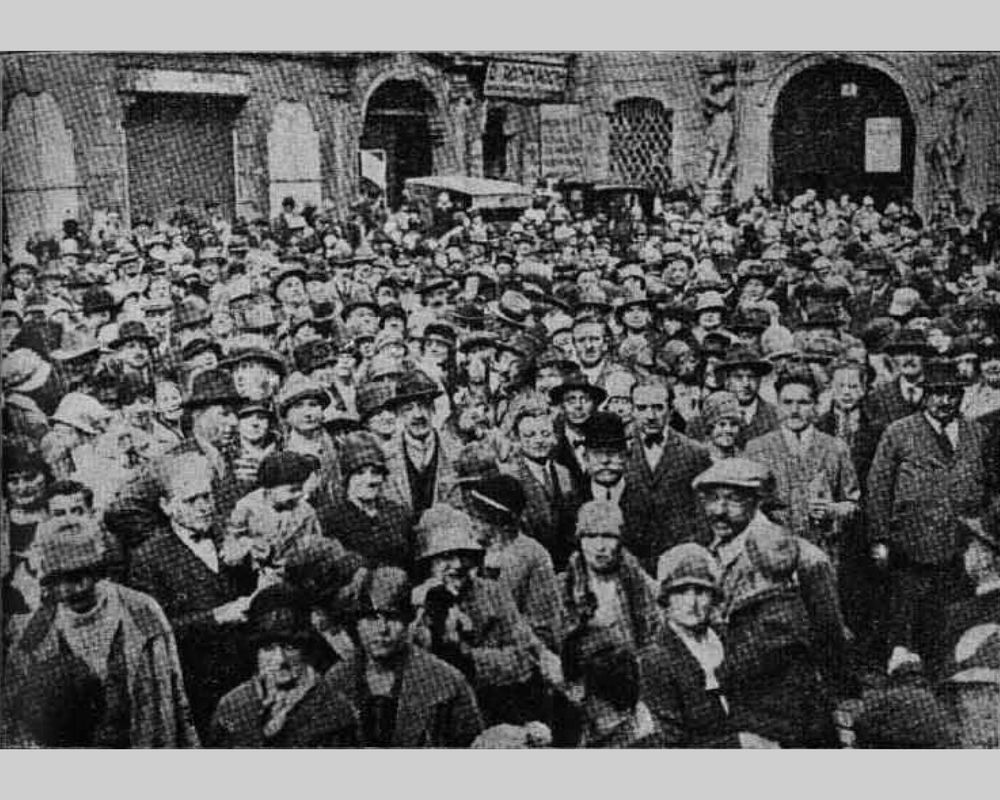

Street rally organized by the Internationaler Tierschutz Kongress in Vienna, 1929

On 13 May in the 18th year of the Republic (1929), the Internationaler Tierschutz Kongress invited Lü Pi-ch’eng to speak at their international conference in Vienna. There were ten speakers, Lü was placed fourth, but when the third speaker could not attend, she was placed third. She represented China and spoke in English. The speech was simultaneously translated into German and French. The title of the speech was: There Should be No Slaughter.

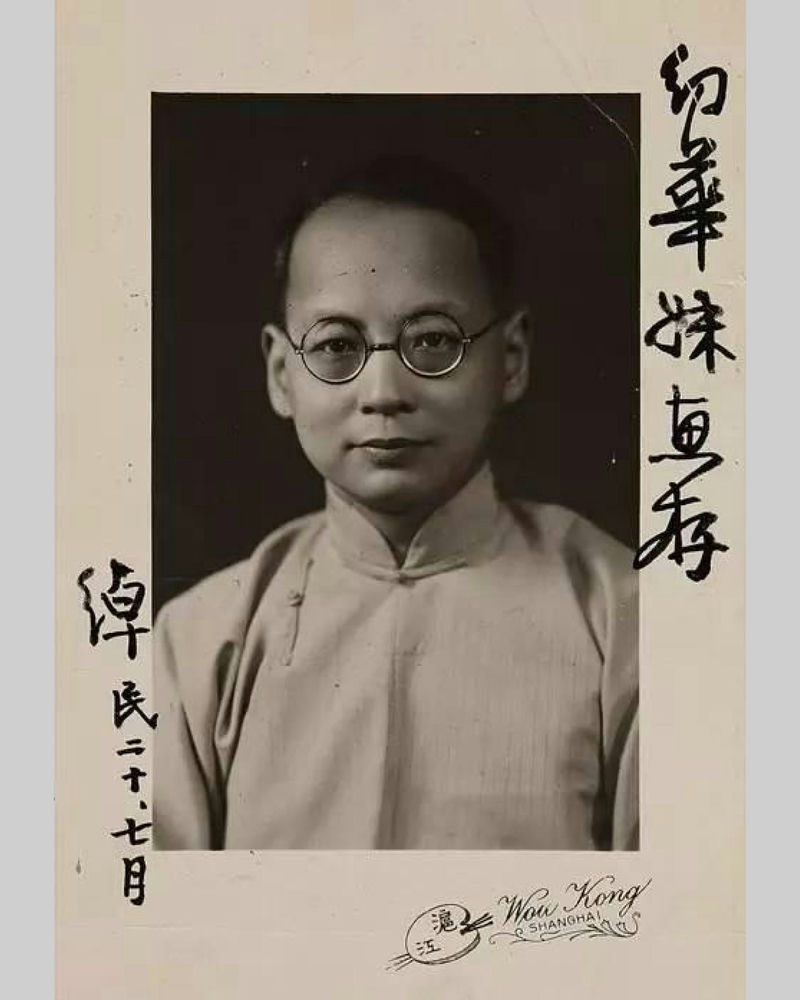

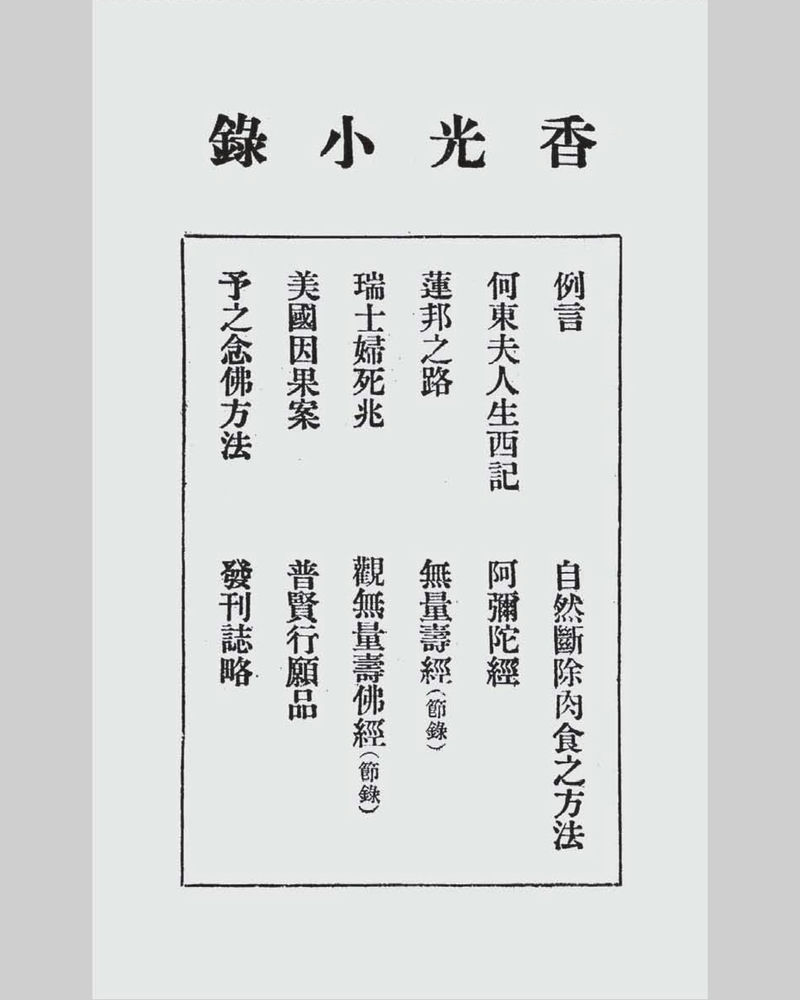

In Europe and America, Lü Pi-ch’eng used a number of English names. They were: Pi Cheng Lee, Alice Pi Cheng Lee and Upasika Chihmann. For Lü to intentionally translate her surname as Lee and not the conventional Wade-Giles translation of Lü, not just because Lee is a common English surname and name, one may conjecture that the meaning of the word Lee, which is “shelter from the wind”, appears to be far more philosophical and poetic. Upasika is a Sanskrit word, it means a female lay devotee of the Gautama Buddha. Chihmann is the phonetic translation of her Buddhist name Chih-man (智曼). When she published Hsiang-kuang hsiao-lu (香光小錄) in the 27th year of the Republic (1928), the name she used was Buddhisattva Precepts Upasika Chih-man Lü Pi-ch’eng (菩薩戒優婆夷智曼呂碧城).

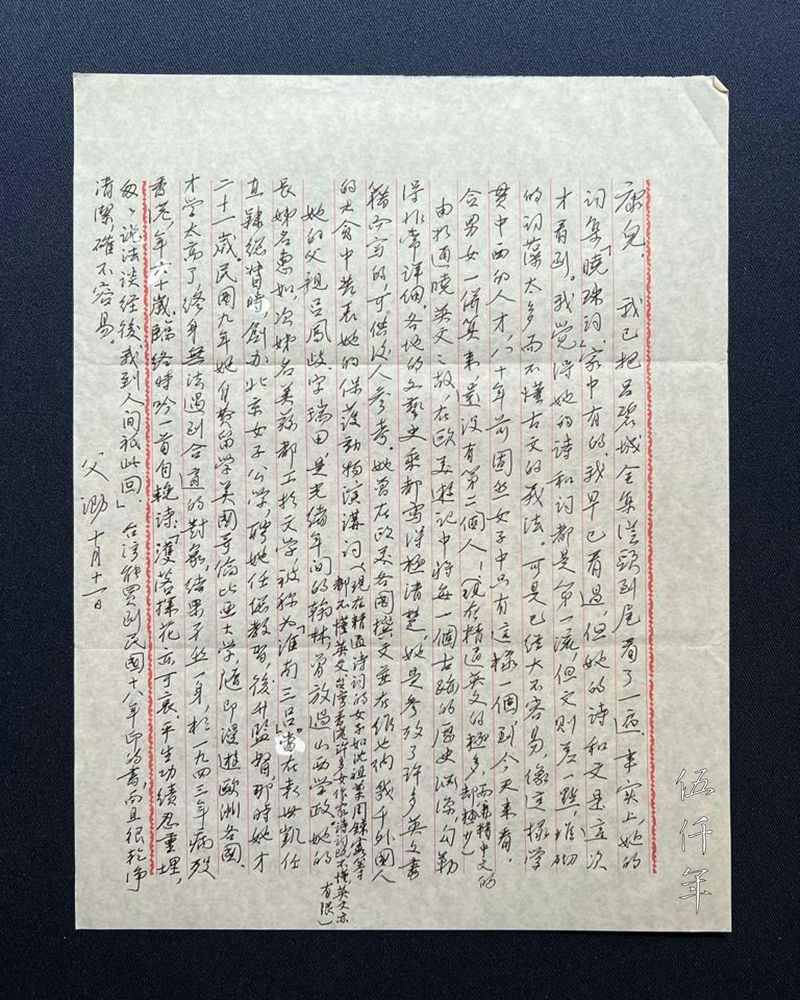

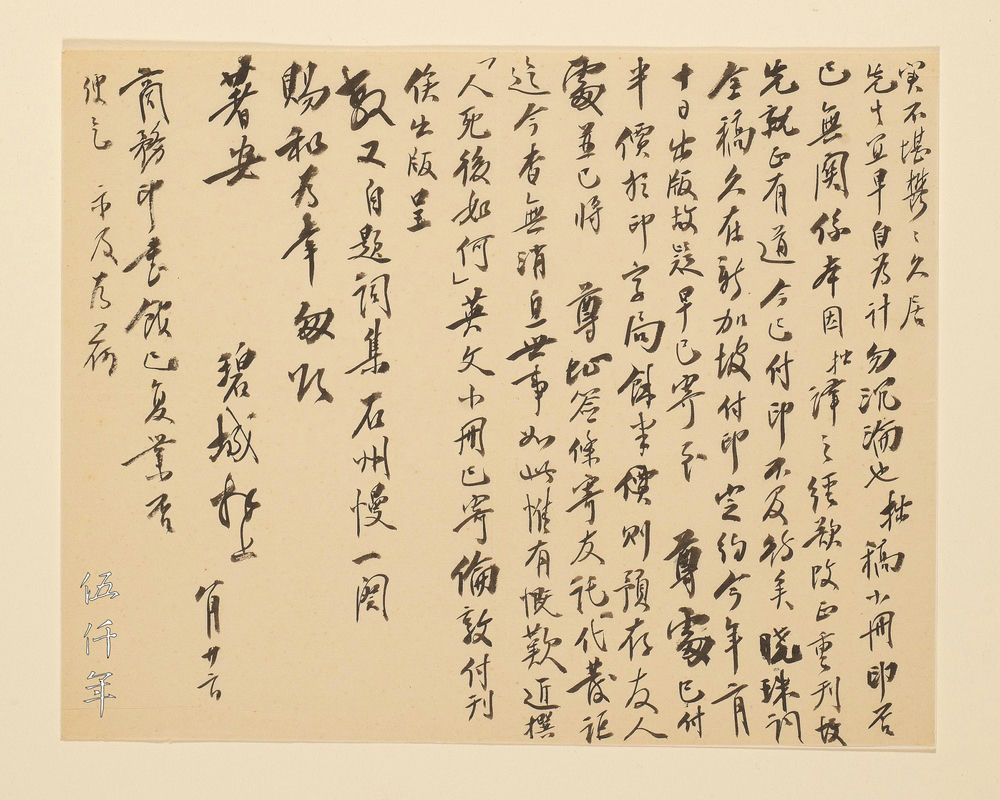

Letter by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng to son discussing Lü Pi-ch’eng

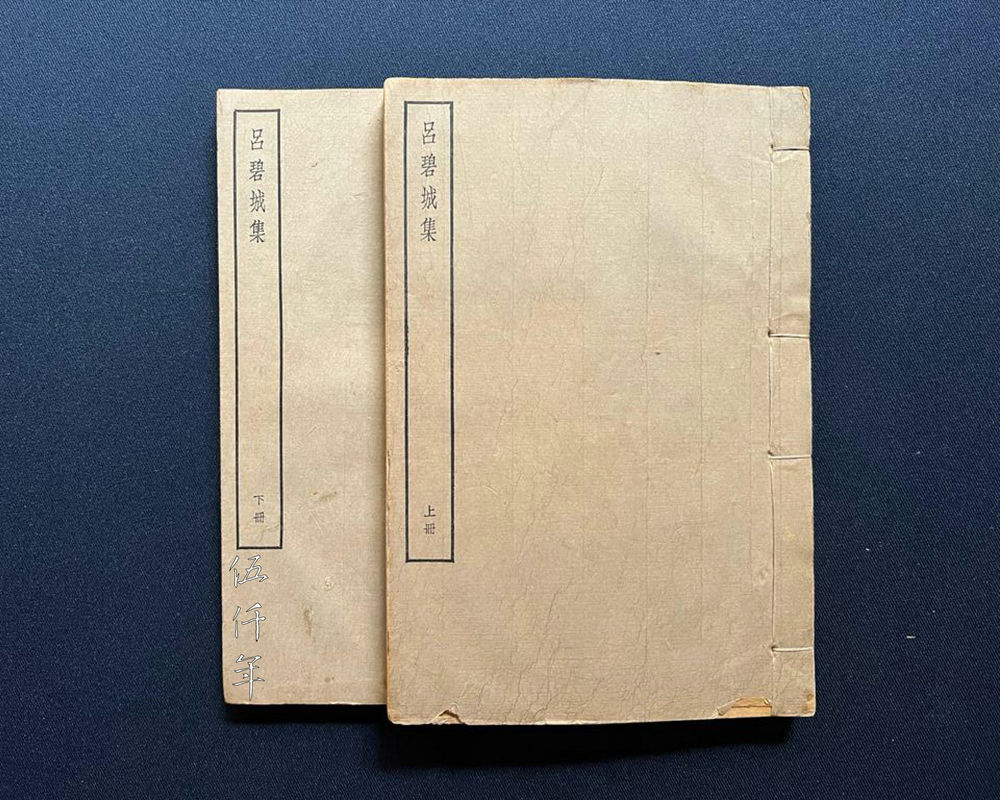

Lü Pi-ch’eng excelled in tz’u lyrics. Her talent was recognized by the eminent scholars Fan Tseng-hsiang (樊增祥 1846-1931) and I Shun-ting (易順鼎 1858-1920). Over twenty years ago, I acquired a set of The Collected Works of Lü Pi-ch’eng published by Chung Hwa Book Company in the 18th year of the Republic (1929) from the antiquarian bookshop Pai-ch’eng T’ang. I posted it to my father, Mr. Soong Hsün-leng (宋訓倫) as a pleasurable read. He wrote a letter in reply:

“Son Kong:

I have finished reading once The Collected Works of Lü Pi-ch’eng from beginning to end. In fact, there is a copy of her anthology of tz’u lyrics, Hsiao-chu tz’u (曉珠詞), in our house. I read it long time ago. But this was the first time I came across her poetry and essays. I feel her poetry and tz’u lyrics are of the highest standard, though her essays pale by comparison. There are too many stacks of embellished words, nor did she understand the rules of classical essays. Nevertheless, this is already so difficult to achieve. A talent like her whose learnings encompass Chinese and English, was indeed the only female eighty years ago. Looking at the world today, even combining all the males and females together, there is no one to be found! (There are many who are proficient in English, but those who are simultaneously proficient in Chinese are truly rare.)

As she knew English, in her travel writings of Europe and America, the story and origin of each historic site were described in detail, the literary annals of each place were clearly elucidated. She consulted many books in English before writing, and they could be references for future generations. She wrote articles when travelling through different European countries and she gave a speech on animal protection in front of a few thousand people in Vienna. (The contemporary female tz’u poets such as Shen Tsu-fen 沈祖棻 1909-1977, Chou Lien-hsia 周鍊霞 1909-2000 and others do not know English. Many other female writers in Taiwan and Hong Kong do not know classical poetry nor tz’u, and their proficiencies in English are also limited.)

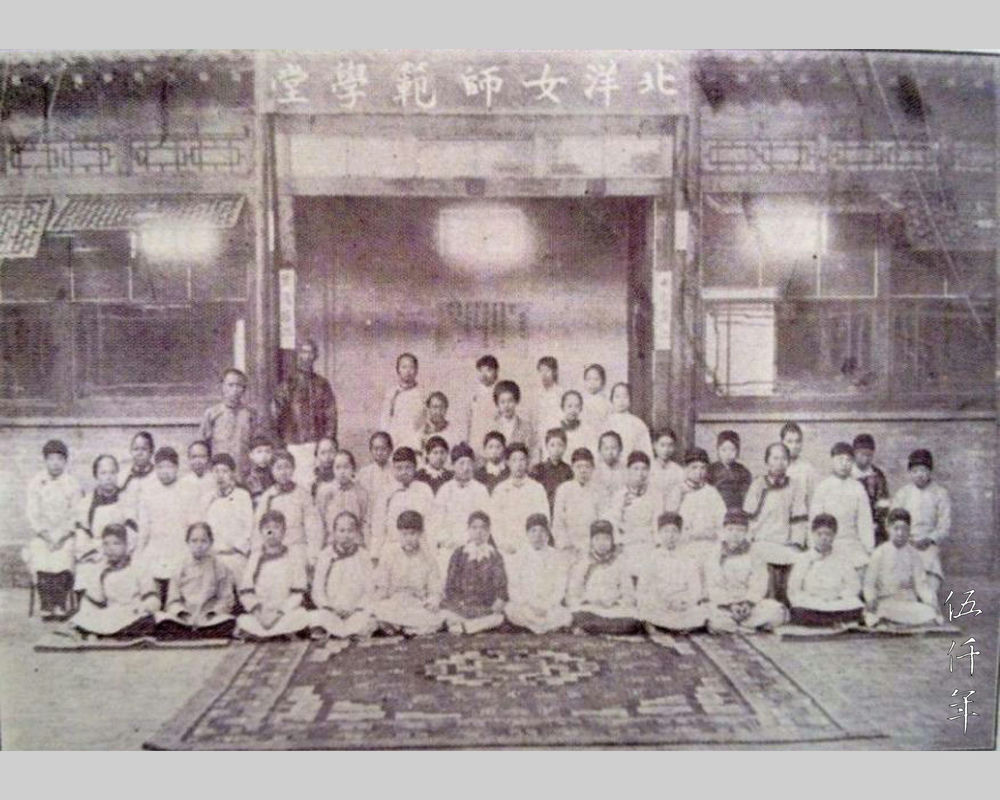

A 1912 group portrait of students at the P’ei-yang Women’s Normal School where Lü Pi-ch’eng was headmistress

Her father Lü Feng-ch’i (呂鳳岐), tzu Jui-t’ien, was a Hanlin Academician during the Kuang-hsü reign. He was once appointed Provincial Education Commissioner of Shansi Province. Her eldest sister was Hui-ju (惠如), the second eldest sister was Mei-sun (美蓀), both excelled in literature. They are called The Three Lü of Huai-nan. When Yüan Shih-k’ai (袁世凱 1859-1916) was Viceroy of Chihli, he founded the Pei-yang Women’s Normal School, and invited her to be the head teacher, and later promoted to be the headmistress. She was only twenty one years old at the time. In the 9th year of the Republic (1918), she went abroad to study at Columbia University at her own expense. Soon afterwards, she toured numerous countries in Europe. Her talent and erudition were just too outstanding, she could not meet a suitable partner in her lifetime, by the end she remained alone, and died in Hong Kong in 1943, aged sixty. She recited a piece of elegy for herself before passing away. It reads:

Do condole the third daughter

For her downfall and downcast,

Take heart to dig and bury,

Attainments a lifetime earned,

How hasty are these preachings

Of Dharma and of Sutra,

This mortal world I come to visit

Just once and not another time.

In Taiwan, it is certainly not easy to acquire a book printed in the 18th year of the Republic (1929) that is clean and fine.

Written by Father,

11 October.”

Volume One and Two of The Collected Works of Lü Pi-ch’eng published by Chung Hua Book Company in 1929

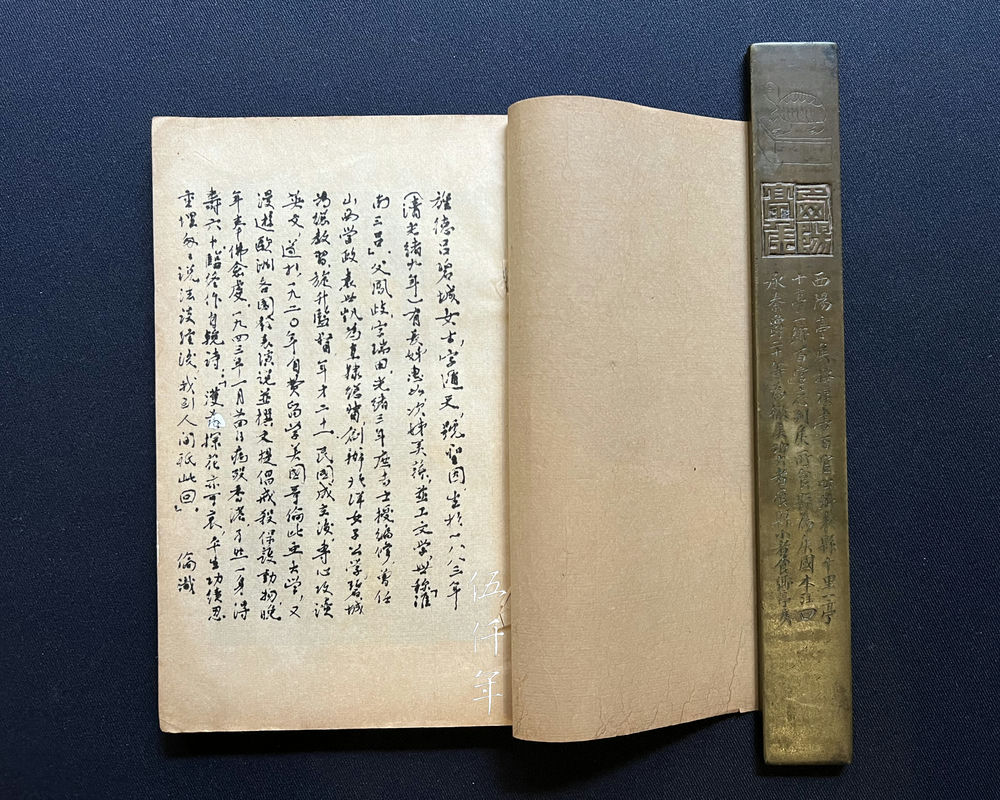

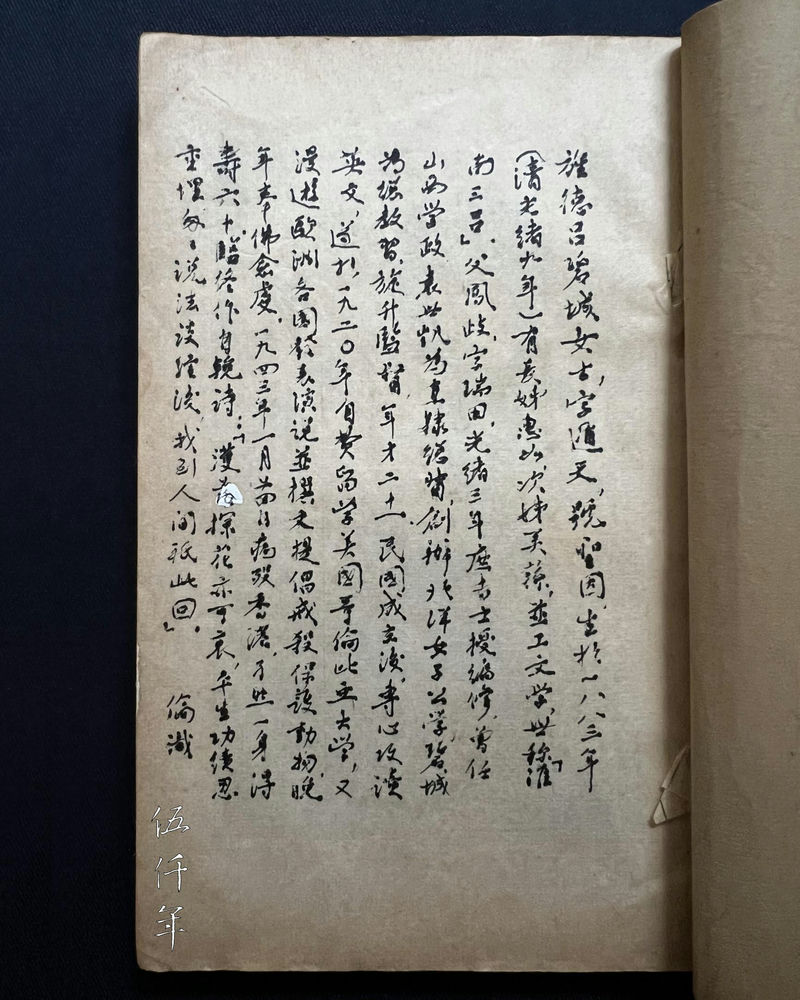

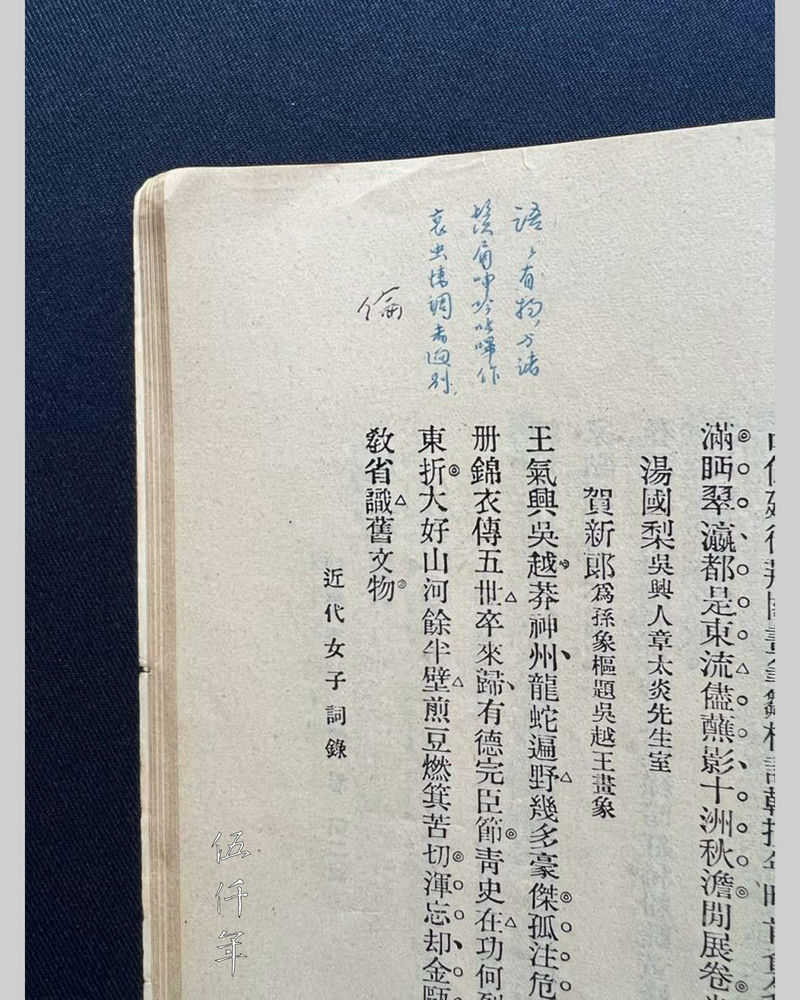

Inscription by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng on the inside page of The Collected Works of Lü Pi-ch’eng

Detail of inscription by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng on the inside page of The Collected Works of Lü Pi-ch’eng

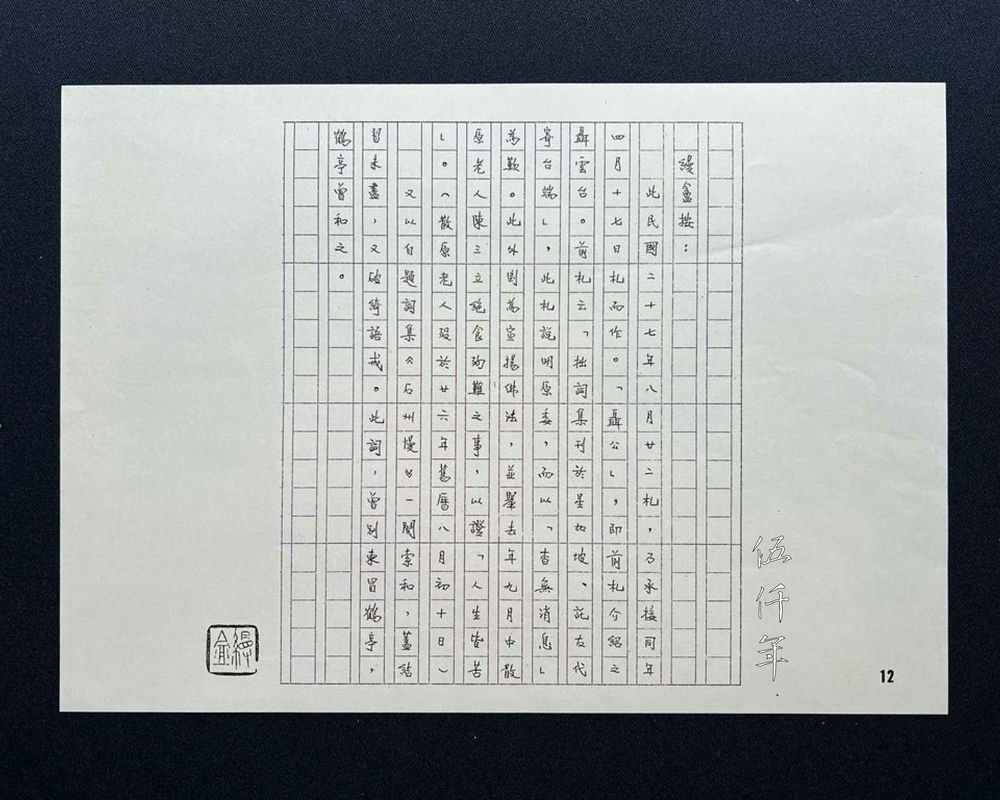

Mr. Soong Hsün-leng subsequently wrote a long inscription on the inside page of The Collected Works of Lü Pi-ch’eng published in the 18th year of the Republic by Chung Hwa Book Company. The text is similar to that of the letter. It reads:

“Ms. Lü Pi-ch’eng from Ching-te, Anhwei Province, tzu Tun-fu, hao Sheng-yin, born in 1883 (the 9th year of the Kuang-hsü reign). Her eldest sister was Hui-ju, her second eldest sister was Mei-sun, they all excelled in literature, thus known as The Three Lü of Hui-nan. Her father Feng-ch’i was appointed Hanlin Bachelor in the 3rd year of the Kuang-hsü reign, and later Junior Compiler. He was once appointed Provincial Education Commissioner of Shansi Province. When Yüan Shih-k’ai was Viceroy of Chihli, he founded the Pei-yang Women’s Normal School, and invited her to be the head teacher, and later promoted to be headmistress. She was only twenty one years old at the time. After the founding of the Republic of China, Lü Pi-ch’eng focused on English studies, hence in 1920, she went abroad to the United States to attend Columbia University at her own expense. Furthermore, she toured numerous countries in Europe. She gave speeches and published essays on the abstinence from slaughtering animals. In later life, she became ever more devoted to Buddhism. On 24 January 1943 she passed away alone in Hong Kong, aged sixty. Before her death, she wrote a piece of elegy for herself. It reads:

“Do condole the third daughter,

For her downfall and downcast,

Take heart to dig and bury,

Attainments a lifetime earned,

How hasty are these preachings,

Of Dharma and of Sutra,

This mortal world I come to visit,

Just once and not another time.

Acknowledged by Leng.”

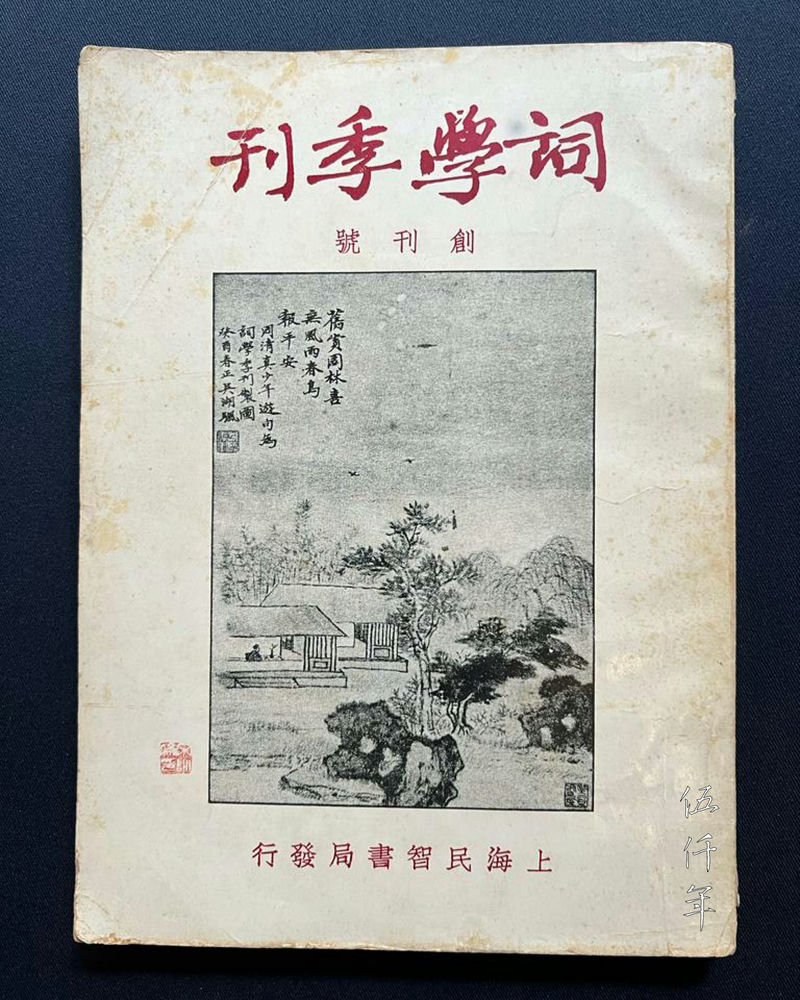

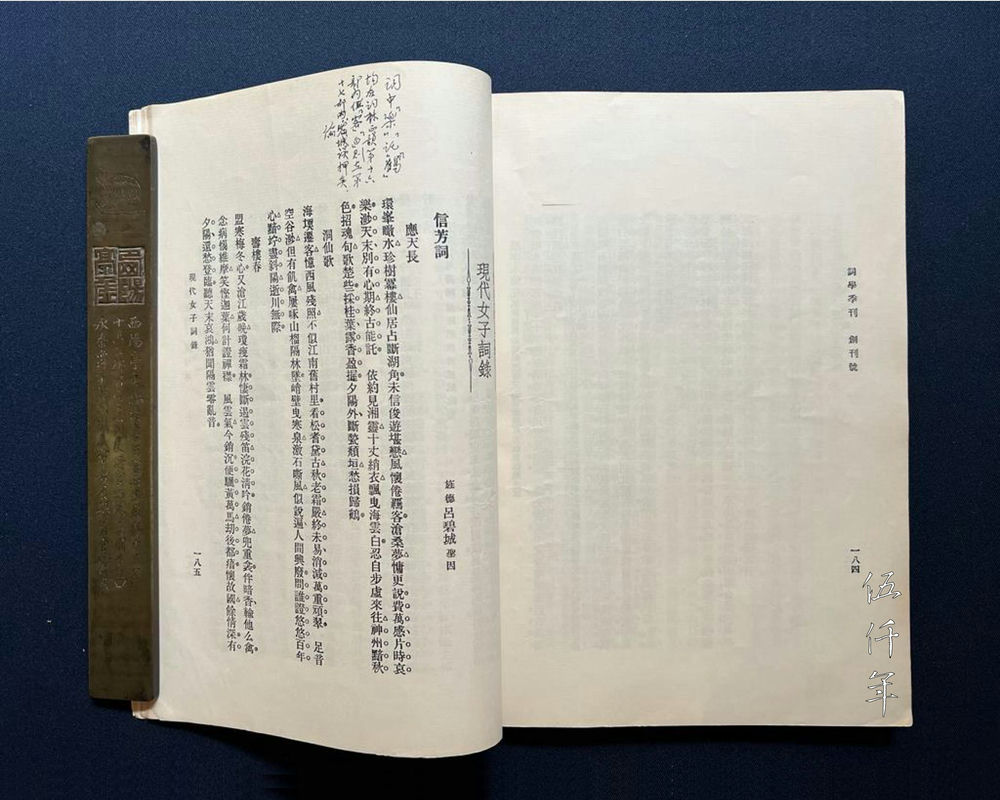

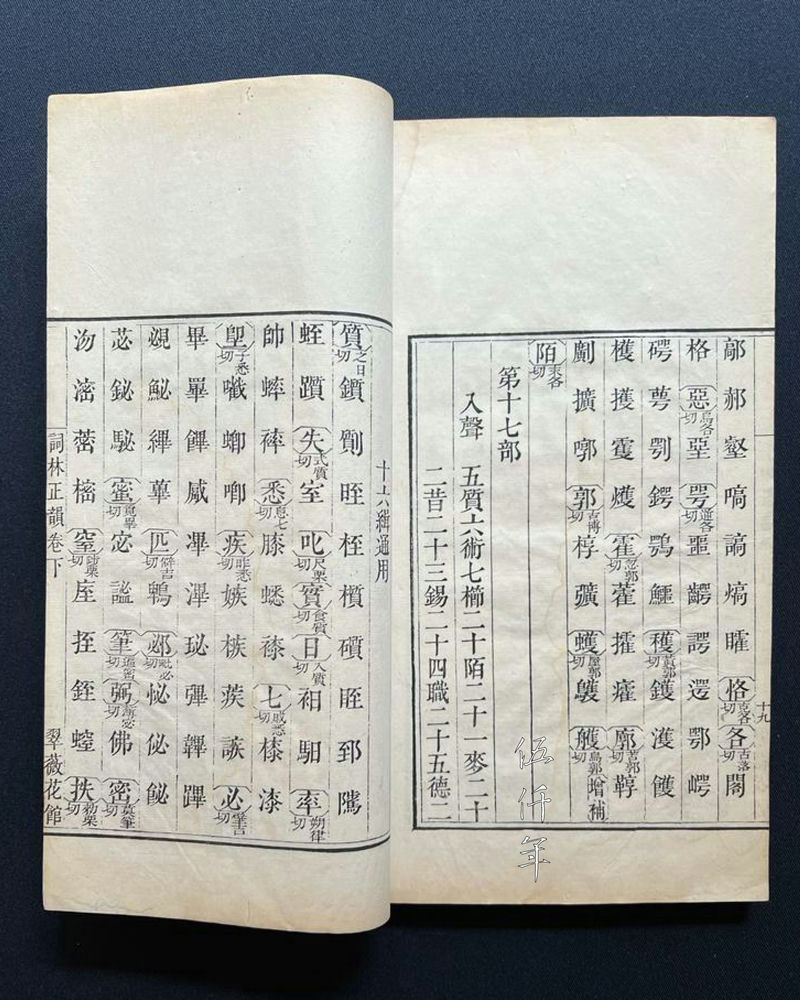

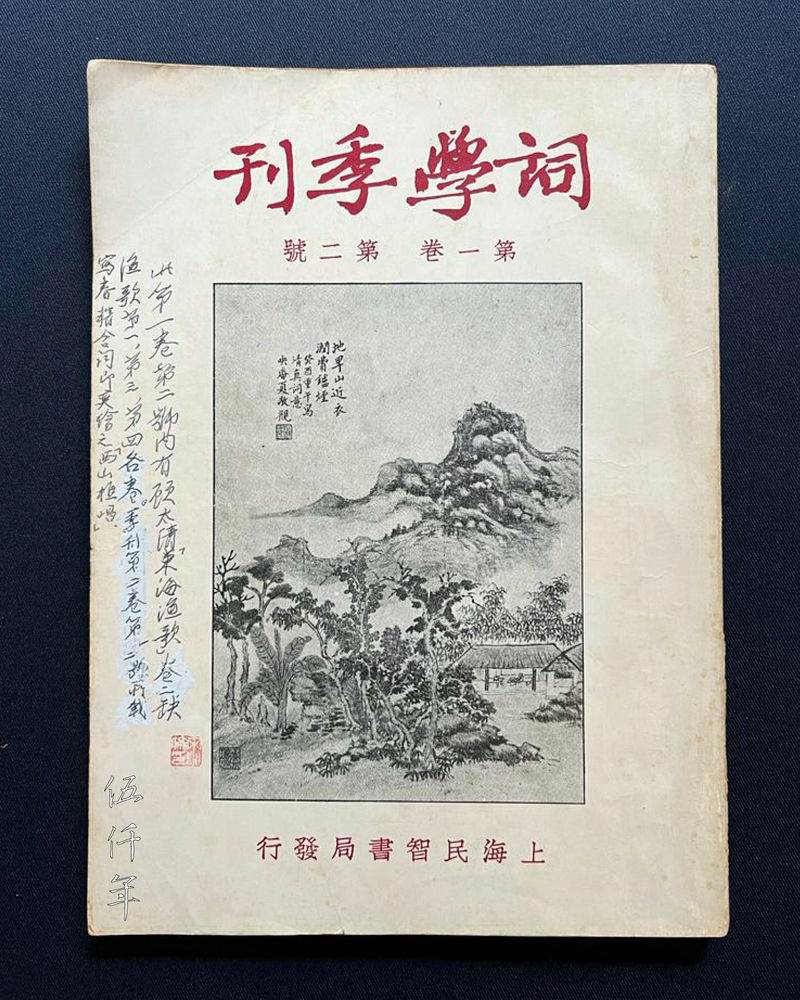

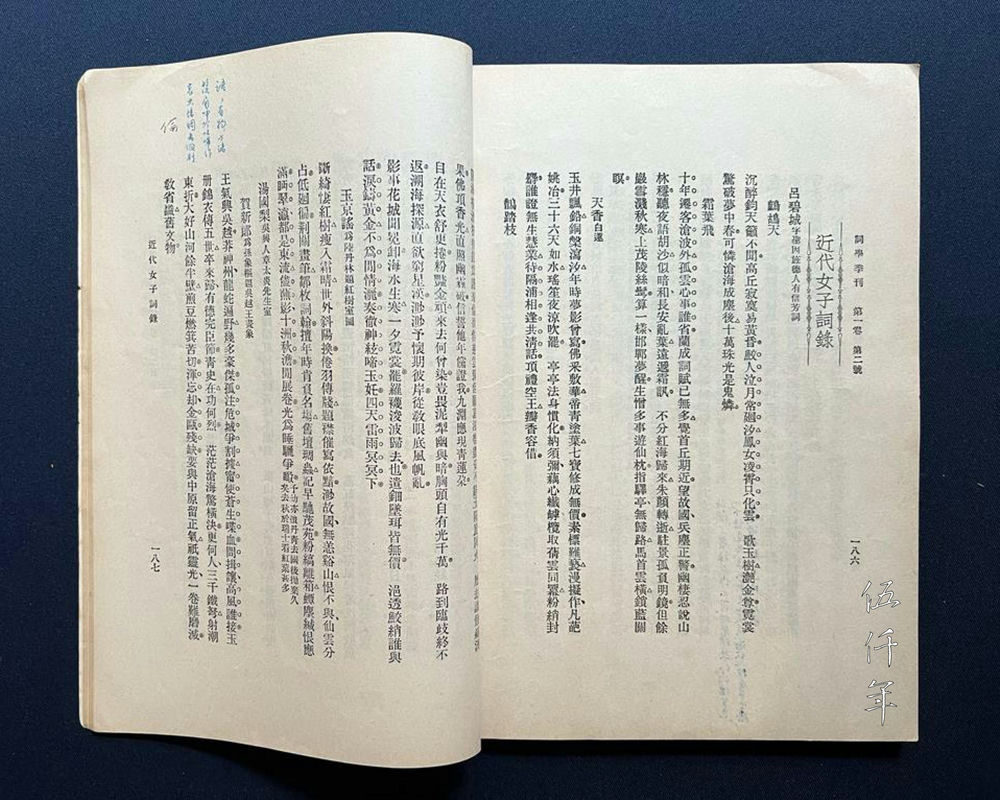

Front cover of the first issue of the Seasonal Magazine of Tz’u Studies

To the tune Ying t’ien-ch’ang by Lü Pi-ch’eng published in the chapter An Anthology of Tz’u by Modern Women in the Seasonal Magazine of Tz’u Studies

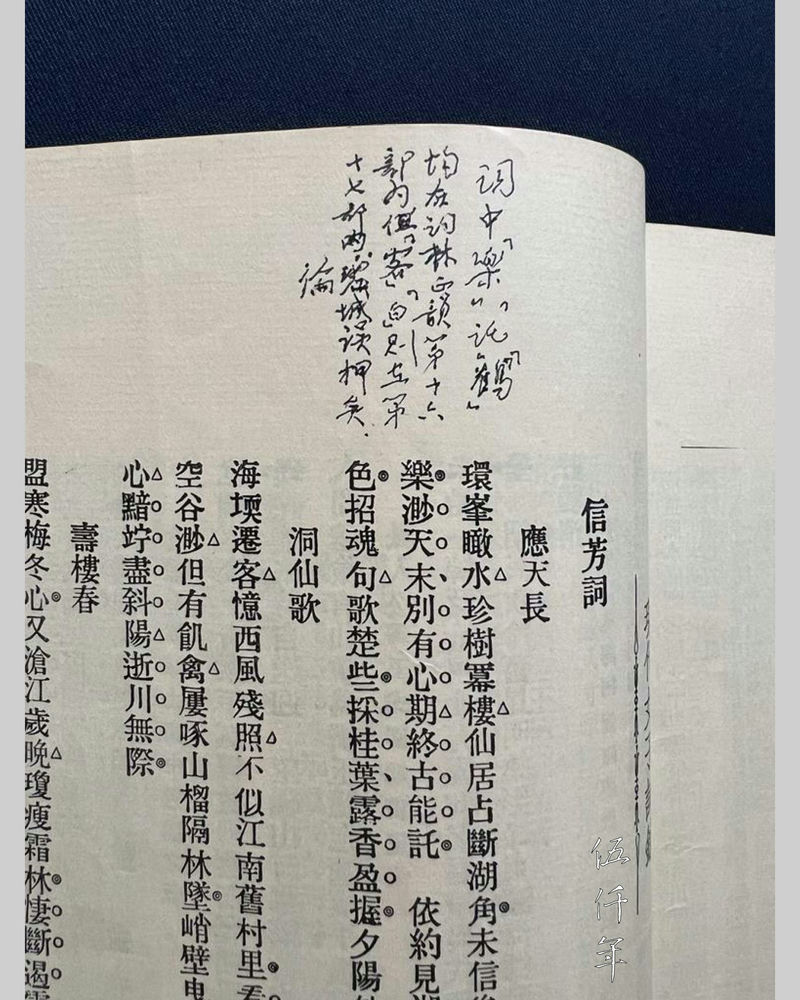

Inscription by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng above the lyric To the tune Ying t’ien-ch’ang

In our house, there is a copy of the first issue of Tz’u-hsüeh chi-k’an (Seasonal Magazine of Tz’u Studies 詞學季刊), edited by Lung Yü-sheng (龍榆生 1902-1966) and published in the 24th year of the Republic (1935). In the section An Anthology of Tz’u by Modern Women (現代女子詞錄), there is a tz’u lyric To the tune Ying t’ien-ch’ang (應天長) by Lü Pi-ch’eng. Mr. Soong Hsün-leng inscribed the upper margin of the page:

“The characters in this tz’u: le (樂), t’o (託), ho (鶴), were all recorded in Chapter Sixteen of Tz’u-lin cheng-yün (The Correct Rhyme of Tz’u 詞林正韻), but the other characters in this tz’u: k’ei (客), pai (白) were recorded in Chapter Seventeen instead. Pi-ch’eng had rhymed incorrectly. Leng.”

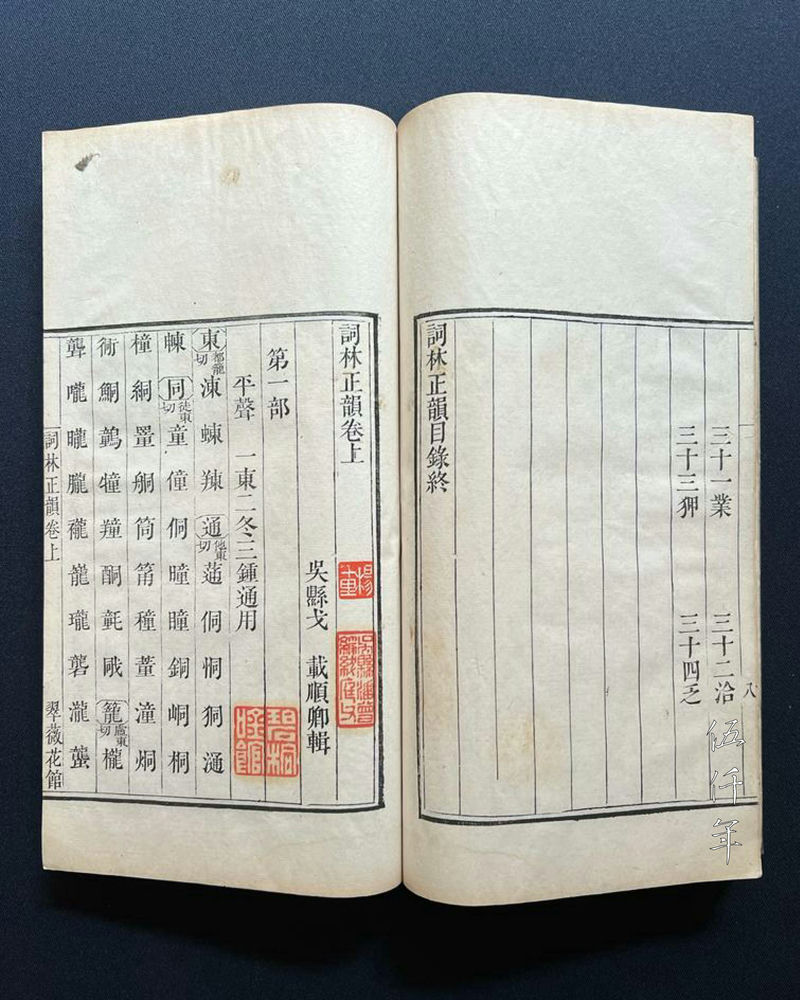

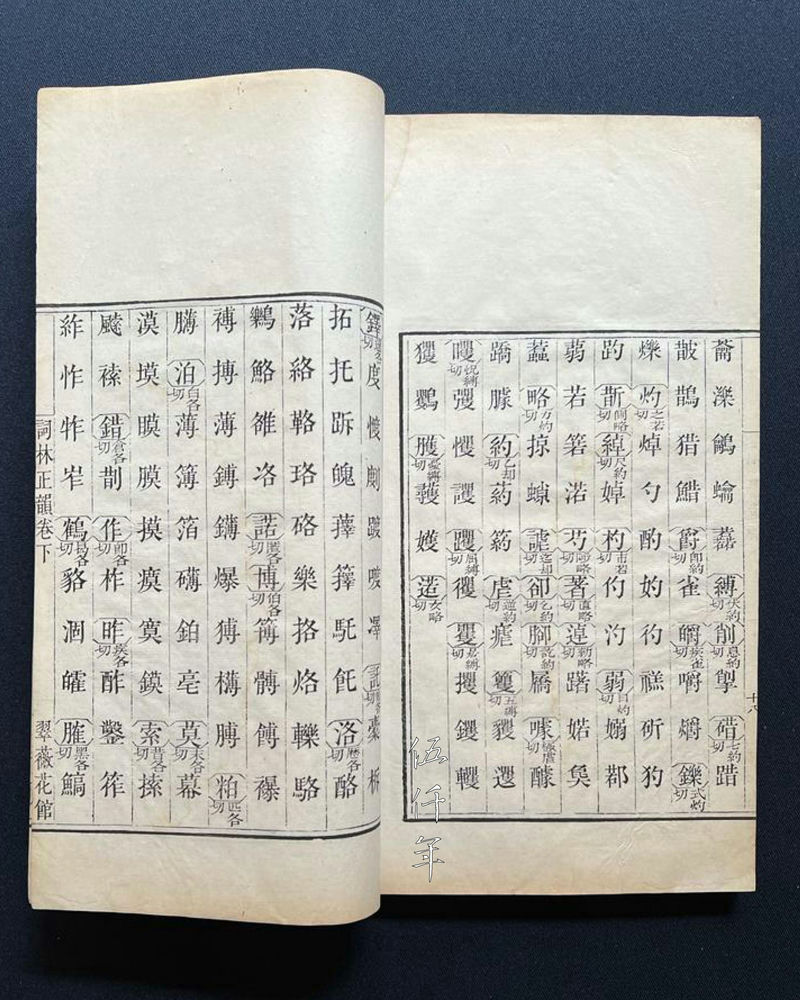

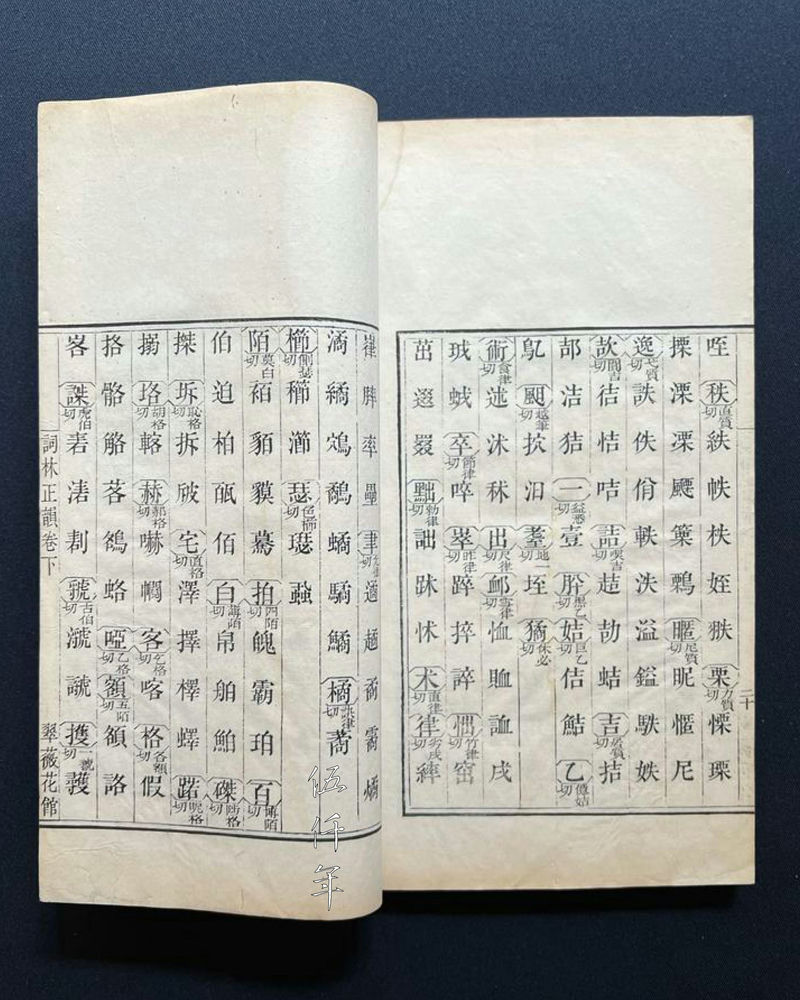

Inside page of The Correct Rhyme of Tz’u compiled by Ko Shun-ch’ing (戈順卿)

First page of Chapter Sixteen of The Correct Rhyme of Tz’u

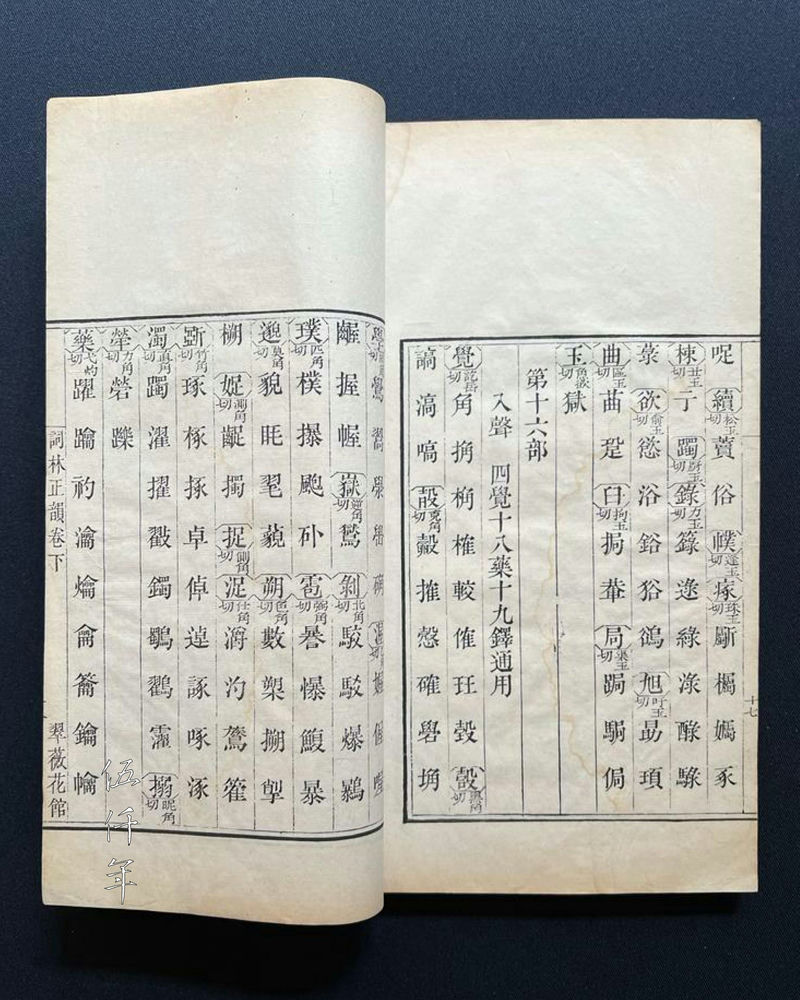

Fourth page of Chapter Sixteen with the characters t’o (託), le (樂), ho (鶴)

First page of Chapter Seventeen of The Correct Rhyme of Tz’u

Fourth page of Chapter Seventeen with the characters pai (白), k’ei (客)

In No. Two Vol. One of Tz’u-hsüeh chi-k’an, the section An Anthology of Tz’u by Modern Women published a tz’u lyric To the tune Ho hsin-lang (賀新郎) by Lü Pi-ch’eng. On the upper margin, Mr. Soong Hsün-leng inscribed:

“Each word has meaning. Comparing this with the other male poets who groan for effect, act like a pitiful worm to make melancholic tune, this is diametrically opposite. Leng.”

Front cover of the No. Two Vol. One of Tz’u-hsüeh chi-k’an

To the tune Ho hsin-lang by Lü Pi-ch’eng published in the chapter An Anthology of Tz’u by Modern Women in the Seasonal Magazine of Tz’u Studies

Inscription by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng above the lyric To the tune Ho hsin-lang

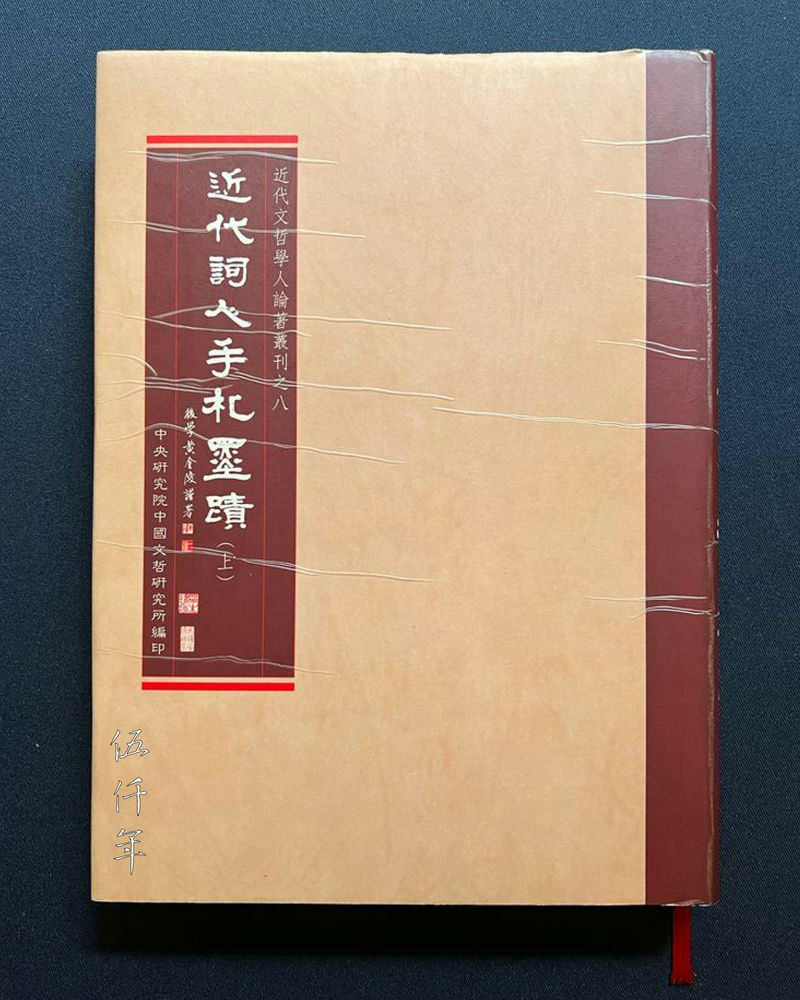

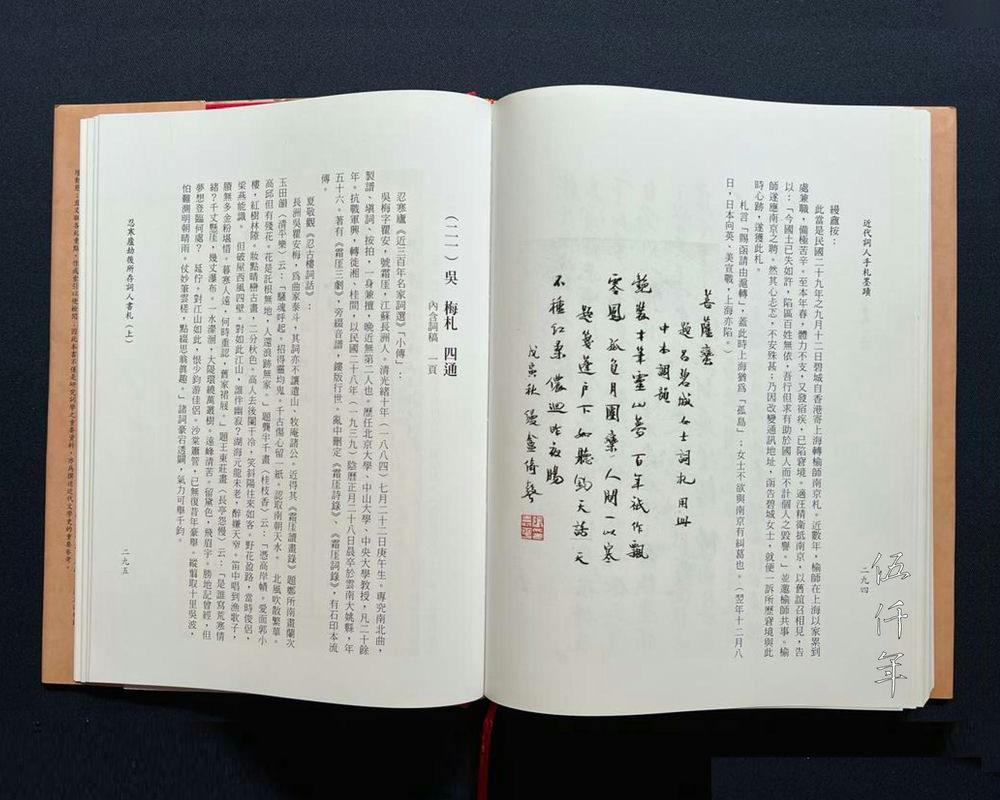

My late friend Prof. Chang Shou-ping (張壽平) was one of the two finest disciples of Mr. Lung Yü-sheng. He collected well over one hundred letters written to Mr. Lung. They were compiled into Treasured Letters by Modern Tz’u Poets which was published by the Institute of Chinese Literature and Philosophy, Academia Sinica, in the 94th year of the Republic (2005). I managed to acquire three letters by Lü Pi-ch’eng.

Front cover of Treasured Letters by Modern Tz’u Poets, compiled by Prof. Chang Shou-ping

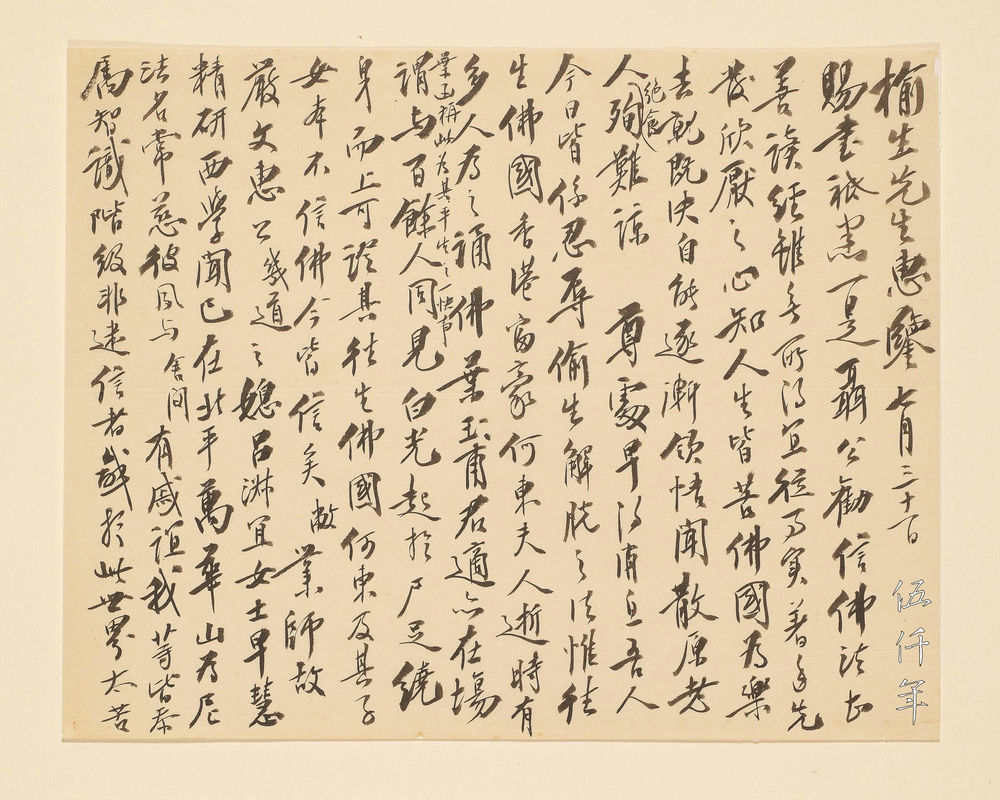

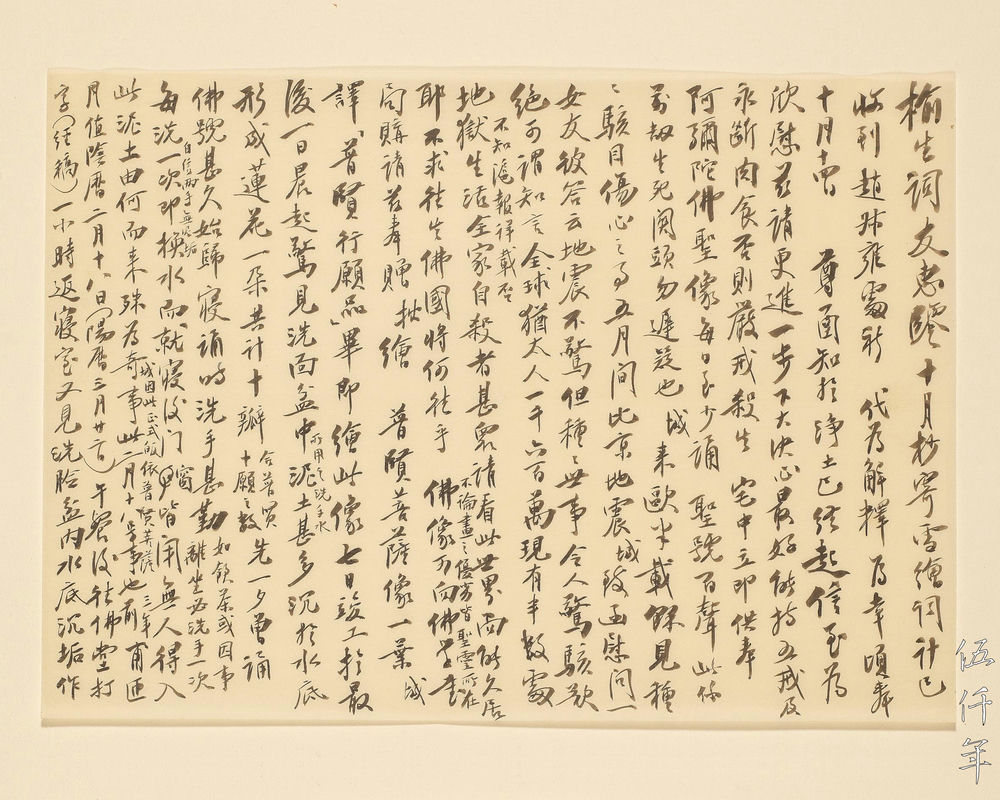

First page of first letter by Lü Pi-ch’eng to Lung Yü-sheng

Second page of first letter by Lü Pi-ch’eng to Lung Yü-sheng

Commentary by Prof. Chang Shou-ping on first letter by Lü Pi-ch’eng

The first letter was written on 22 August in the 27th year of the Republic (1938). The letter reads:

“Dear Mr. Yü-sheng:

I have respectfully read your letter of 31 July. It is a good thing for Mr. Nieh to encourage Buddhist faith. Although nothing has been learned by studying the Sutra, it is fitting to start from practical steps.

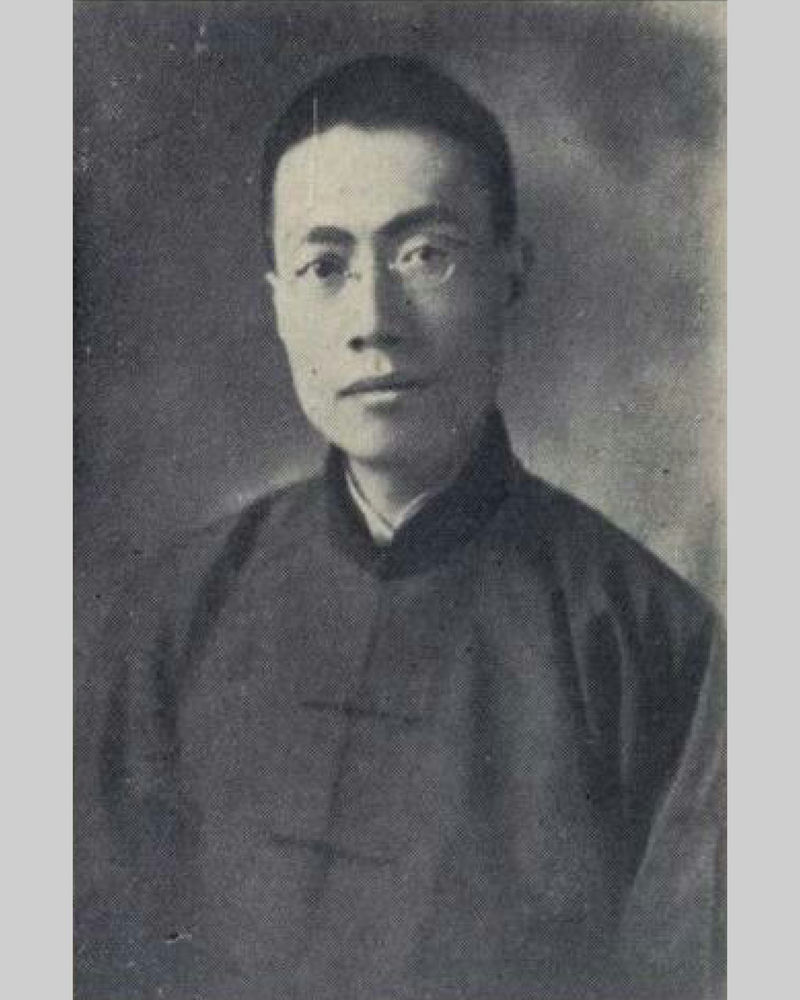

Portrait of Nieh Yün-t’ai

Note: Mr. Nieh was Nieh Yün-t’ai (聶雲台 1880-1953), original name Ch’i-chieh, Buddhist name Hui-chieh, native of Heng-shan, Hunan Province. He attained the hsiu-ts’ai degree (cultivated talent) in the 19th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1893). Later on he became a merchant. In his old age, he became a Buddhist, and called himself Chü-shih (Upasaka). He wrote The Way to Preserve Wealth.

To begin, nurture your heart that feels glad to be weary of the world. For life is inundated with sufferings, while happiness resides in Pure Land. Once this choice is made, one will gradually understand. I heard the Old Man San-yüan (散原老人) went on a hunger strike and died, I trust you have received news earlier.

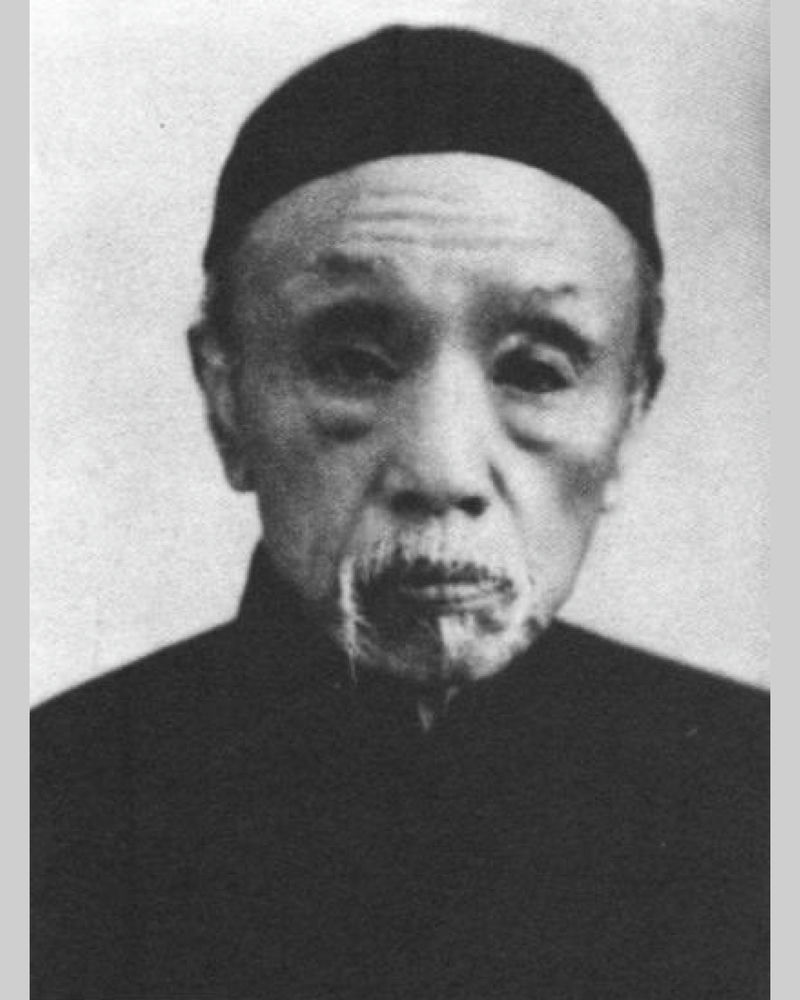

Portrait of Ch’en San-li

Note: Old Man San-yüan was Ch’en San-li (陳三立 1853-1937), hao San-yüan, native of I-ning, Kiangsi Province. His father was Ch’en Pao-chen (陳寶箴 1831-1900), governor of Hunan Province, an important political reformer. San-yüan was one of the leading poets of his time. When Japan invaded China and occupied Peking, he went on a hunger strike for five days and died.

Today we are all enduring humiliation to beg for life. The way to extricate this is to be reborn in Pure Land. When Mrs. Ho Tung (何東夫人), wife of the Hong Kong tycoon passed away, many people prayed for her.

Portrait of Sir Ho Tung

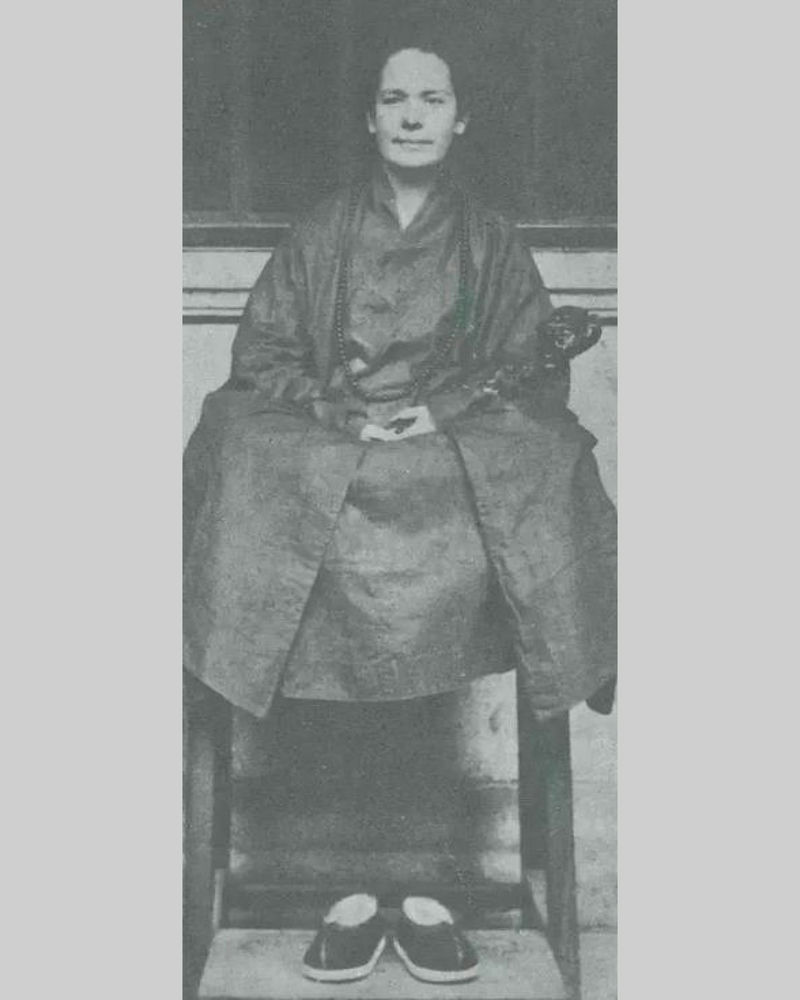

Portrait of Chang Lien-chüeh

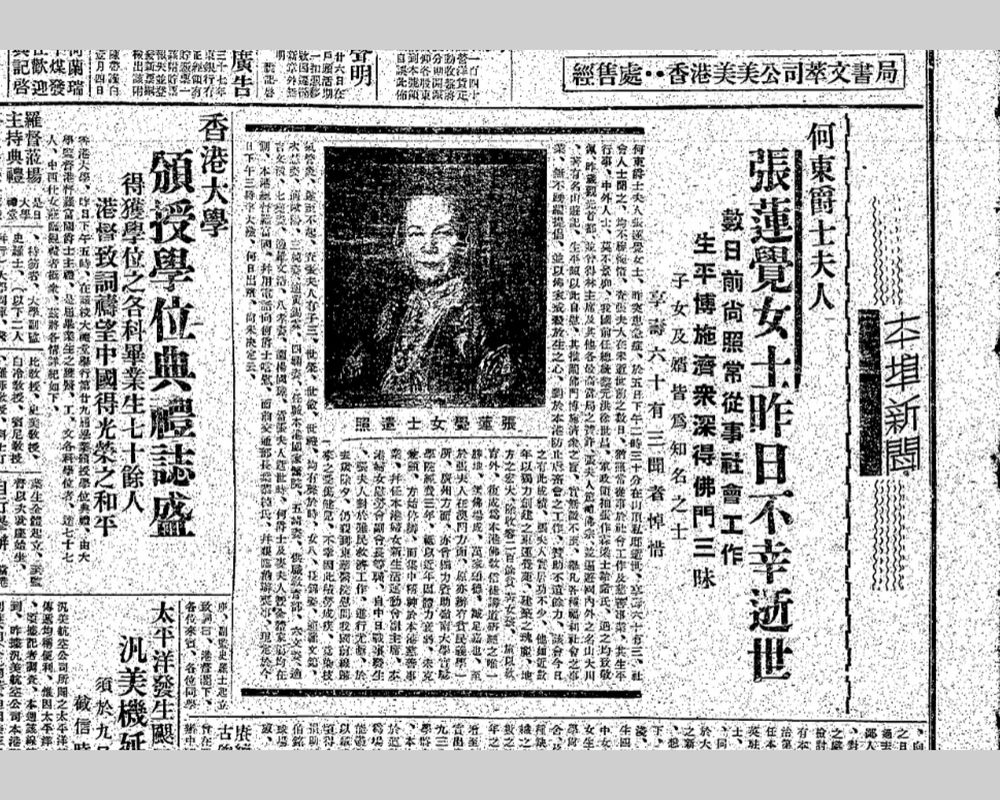

News coverage of the death of Chang Lien-chüeh in the 6 January 1938 copy of The K’ung Sheung Daily News in Hong Kong

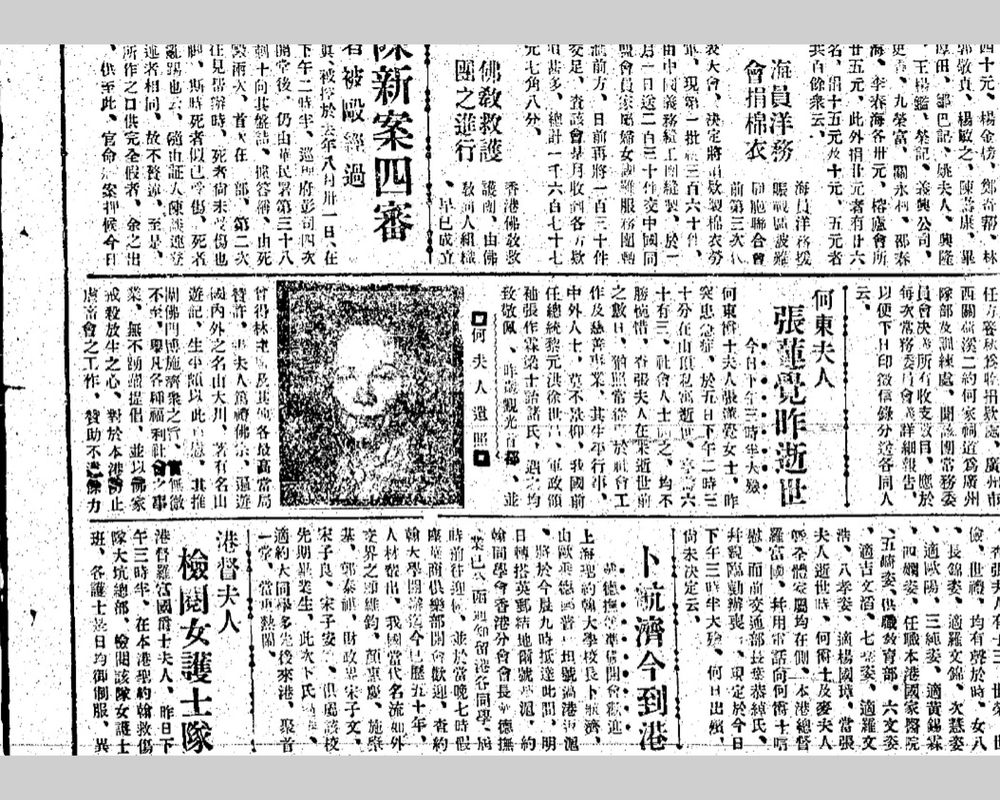

News coverage of the death of Chang Lien-chüeh in the 6 January 1938 copy of The Chinese Mail in Hong Kong

Note: The name of Mrs. Ho Tung was Chang Lien-chüeh (張蓮覺 1875-1938), who used the title Chü-shih (Upasika). She was a native of Hsin-an, Kwangtung Province.

Mr. Yeh Yü-fu (葉玉甫) was present at the scene. (Mr. Yeh claimed in his letter that this was one of the happiest moments in his life.) He said he was accompanied by over one hundred people, together they saw a white light emerging from the feet of the corpse, it swirled round the body and rose. This was evidence of her going to Pure Land.

Portrait of Yeh Kung-ch’o

Note: Yeh Yü-fu, was also known as Yeh Kung-ch’o (葉恭綽 1881-1968), tzu Yü-fu, Yü-hu, hao Hsia-an, native of Fan-yü, Kwangtung Province. In the 9th year of the Republic (1920), he was appointed minister of the Ministry of Transportation, in the 12th year of the Republic (1923), he was appointed minister of the Ministry of Finance. He was a Buddhist and used the title Chü-shih (Upasaka).

Index of Hsiang-kuang hsiao-lu

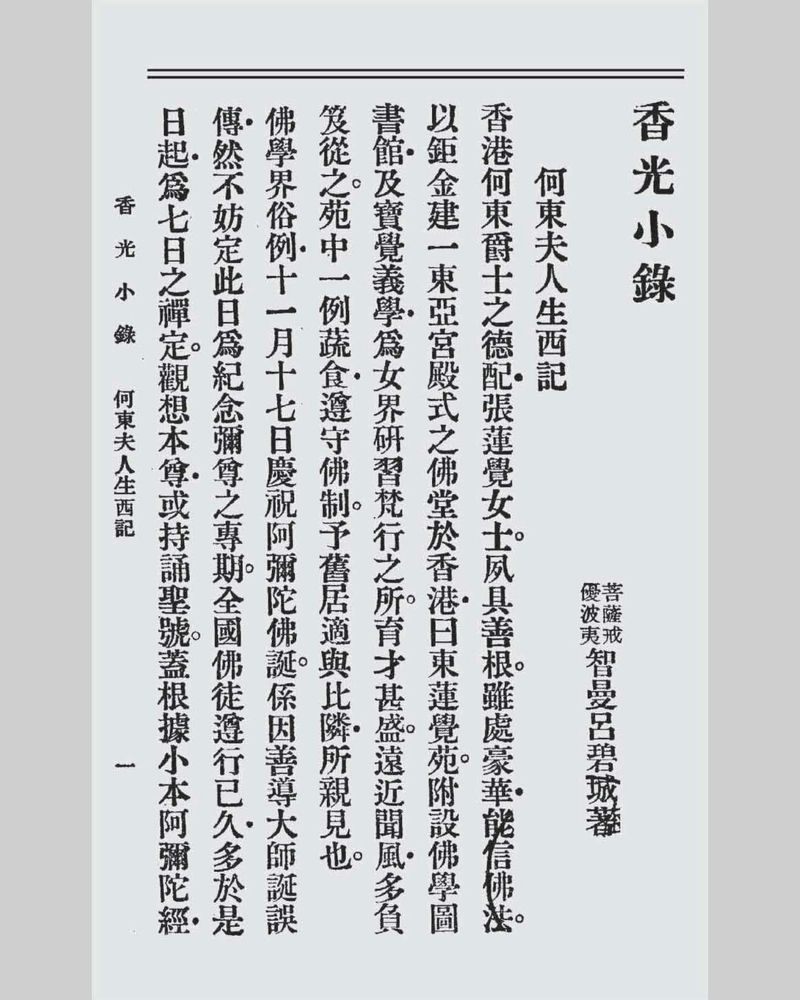

First chapter of Hsiang-kuang hsiao-lu, The Rebirth of Mrs. Ho Tung

In the 27th year of the Republic (1938), Lü Pi-ch’eng published Hsiang-kuang hsiao-lu (香光小錄). The first chapter is titled The Rebirth of Mrs. Ho Tung, and describes in considerable detail the death of Chang Lien-chüeh Chü-shih. It says:

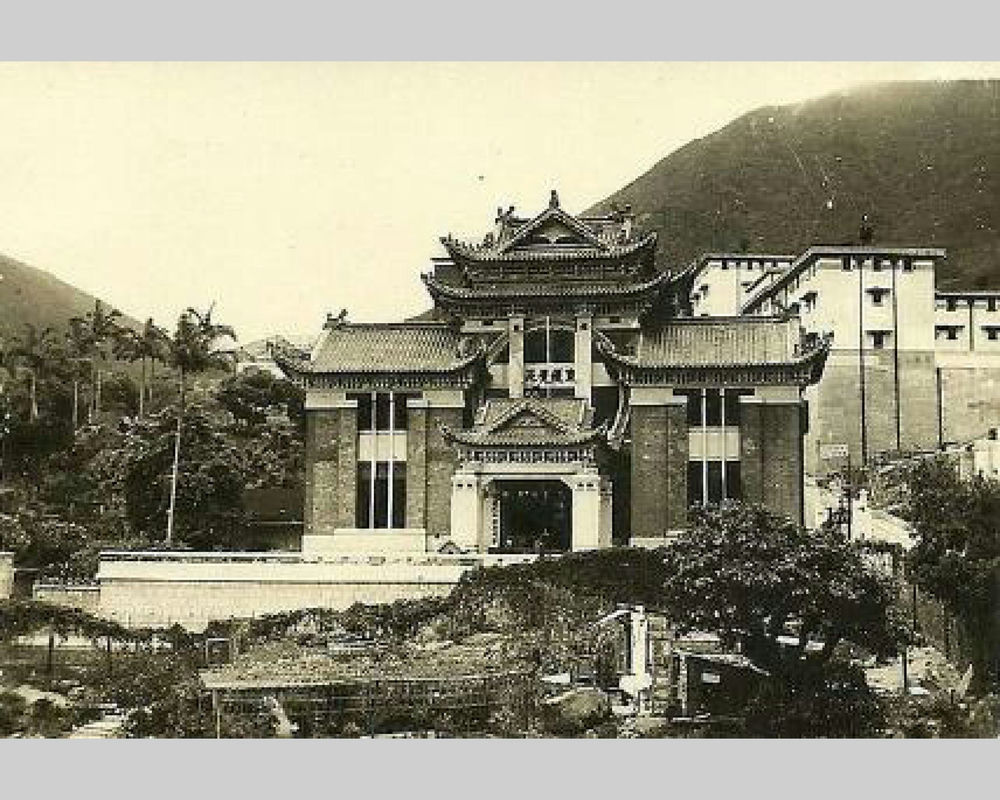

“The wife of Sir Ho Tung in Hong Kong, Mrs. Chang Lien-chüeh, was always kind hearted. Although she was surrounded by luxury, she was a believer in Buddhism. She spent a huge amount to build an East Asian palace style Buddhist temple in Hong Kong, called Tung-lien-chüeh Yüan (東蓮覺苑)…………When she was dying, everyone recited the name of Amitabha Bodhisattva to receive her. Very soon, a red light arose from the soles of her feet, then it changed into a white light. It swirled around the body and moved upwards. This was described in the letter by Mr. Yeh Kung-ch’o, and he claimed this was witnessed by well over one hundred people. I also wrote to one of the supervisors of Tung-lien-chüeh Yüan, Ms. Lin Leng-chen (林楞真), to enquire about the happenings on the day. She too confirmed that she saw this with her own eyes. She further commented that when the corpse was placed in the coffin, the colour on the cheeks turned radiant and the face carried a smile. The arms and legs were soft, the head became cold later. These are evidences of her going to Pure Land”.

Tung-lien-chüeh Yüan, Buddhist temple founded by Chang Lien-chüeh

At first, Ho Tung and his children did not believe in Buddhism. Now, they are all believers. The daughter-in-law of my late teacher Mr. Yen Wen-hui (嚴文惠公), Lü Shu-i (呂淑宜), is clever as a child and diligently studies Western scholarship. I heard she has now become a nun at Wan-hua Mountain in Peking. Her Buddhist name is Ch’ang-tz’u. We have always been relatives.

Portrait of Yen Fu

Note: Yen Wen-hui, original name Yen Fu (嚴復 1854-1921), tzu Chi-tao, native of Hou-kuan, Fukien Province. He was a master of translation in late Ch’ing. His translation works include Evolution and Ethics, The Wealth of Nations, and others.

We can all claim to belong to the category of intellectuals, and not believers of superstition. I feel this world is so inundated with sufferings, to dwell in dejection for too long can be unbearable. Sir, it is pertinent to plan early, do not resign. It is no longer relevant whether I print my little booklet. Originally, I wish to revise and reprint my translation of the Sutra, hence I seek your guidance beforehand. Now it is already printed, it is too late. The complete manuscript of Hsiao-chu tz’u (曉珠詞) has been in Singapore for a long time. The printing contract stipulated that it should be published on 10 February this year, hence I assumed it was mailed to you. I have already paid half of the cost to the printer, the remaining half is entrusted to a friend. I have provided your mailing address for my friend to post you, yet there is no news. The affairs of the world are such, one can only sigh. Lately, I wrote a small English booklet called What Happens After Death? I have sent the manuscript to London for printing, and I am waiting to receive a few copies. I have composed a tz’u lyric To the tune of Shih-chou-man (石州慢) as an epigraph for my anthology of tz’u lyrics. I hereby present it to you to beg for a response tz’u lyric. I have written hastily, and wish you well in your literary endeavors.

Respectfully yours,

Pi-ch’eng,

22 August.

Has The Commercial Press reopened for business? I will appreciate if you can kindly tell me.”

Five letters by Lü Pi-ch’eng were published in Treasured Letters by Modern Tz’u Poets

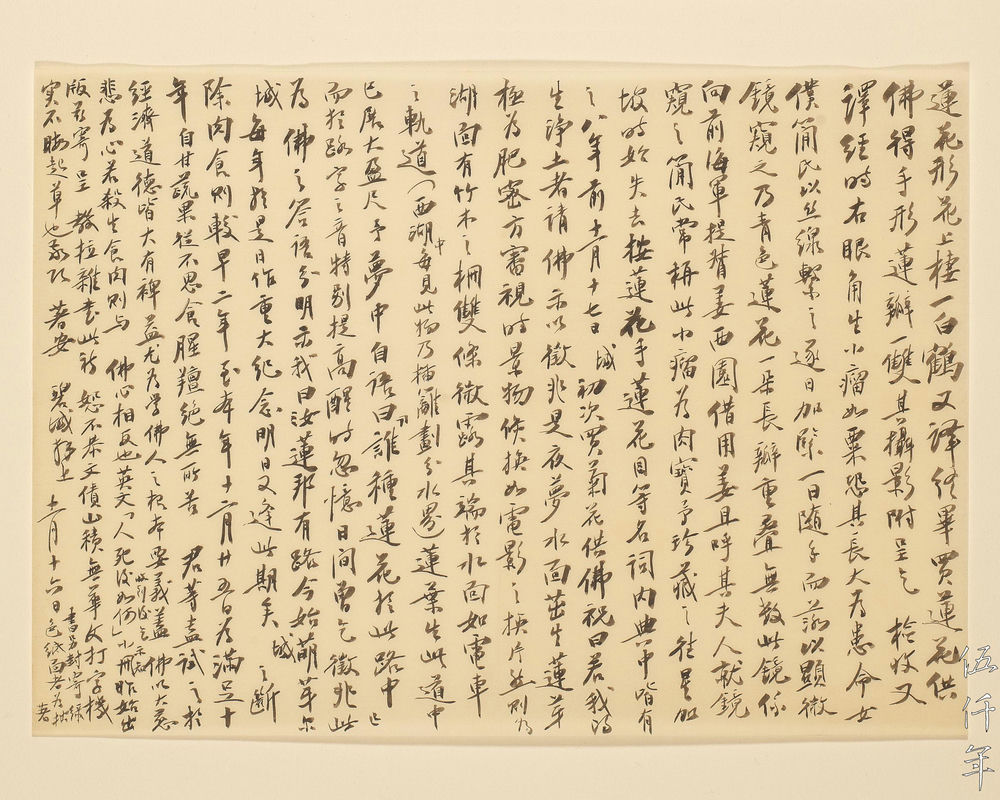

First page of second letter by Lü Pi-ch’eng to Lung Yü-sheng

Second page of second letter by Lü Pi-ch’eng to Lung Yü-sheng

Commentary by Prof. Chang Shou-ping on second letter by Lü Pi-ch’eng

The second letter was written on 16 November in the 27th year of the Republic (1938). It reads:

“Dear Yü-sheng my tz’u companion:

In October, I copied and sent you Hsüeh-hui tz’u (雪繪詞). I guess you have received it. It would be most welcome if you could explain to Chao Shu-yung (趙叔雍) on my behalf.

Portrait of Chao Tsun-yüeh

Note: Chao Shu-yung (趙叔雍 1898-1965), original name Tsun-yüeh, was a tz’u poet.

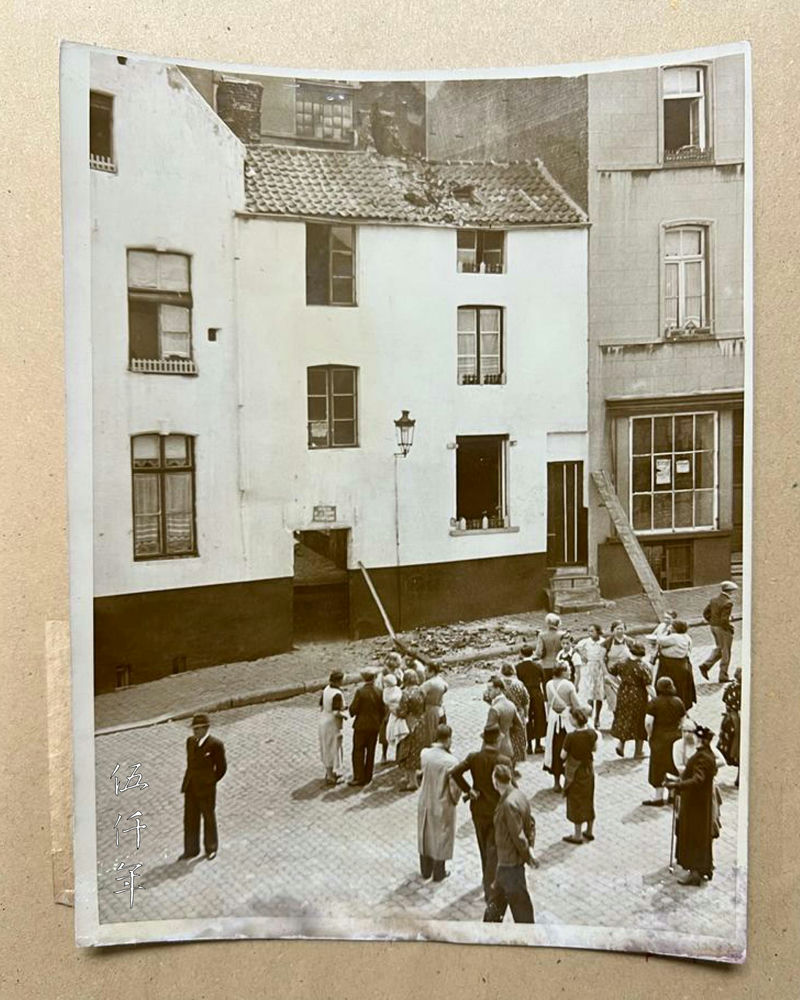

I have just received your letter dated 14 October and learned that you are beginning to have faith in Pure Land. I am most happy. I invite you to take an additional step and make a firm resolution. It is best to observe The Five Precepts and to cease eating meat forever. If not, just strictly guard against any killing. In your house, worship the sacred image of Amitabha Bodhisattva. Everyday you should at least chant His sacred name a hundred times. This is the moment of life and death in the eye of infinite calamity. Do not hesitate. I have arrived in Europe for over half a year, and witnessed all sorts of frightening and heart breaking happenings. In May, an earthquake took place in the capital of Belgium. I wrote a letter to a female friend who lived there to console her. She replied: It is not earthquake that is frightening, rather the assortment of happenings in the affairs of men that are horrifying to the extreme. These can be regarded as farsighted words.

Buildings in Belgium after earthquake on 11 June 1938

Note: At noon on 11 June 1938, Belgium was hit by an earthquake with a Richter magnitude of 5.0. Newspapers at that time reported it to be the largest earthquake in forty five years.

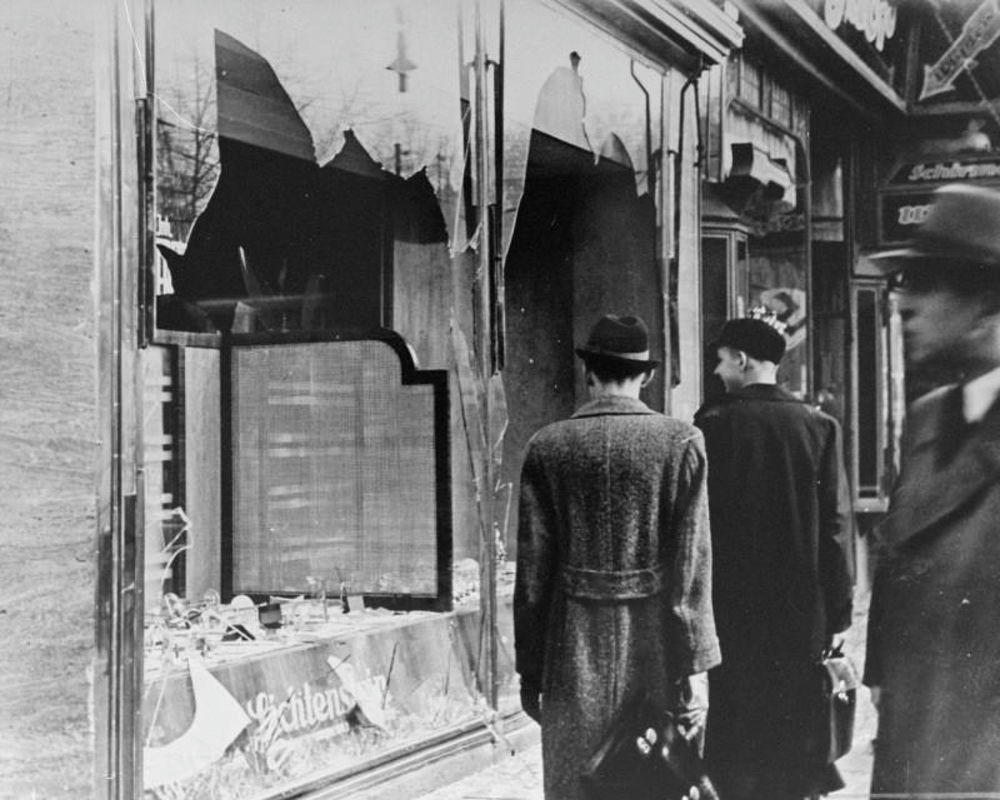

There are sixteen million Jews in the world, and half of them now live under the conditions of inferno. Many families committed suicides in pacts. (Have newspapers in Shanghai reported this in detail?)

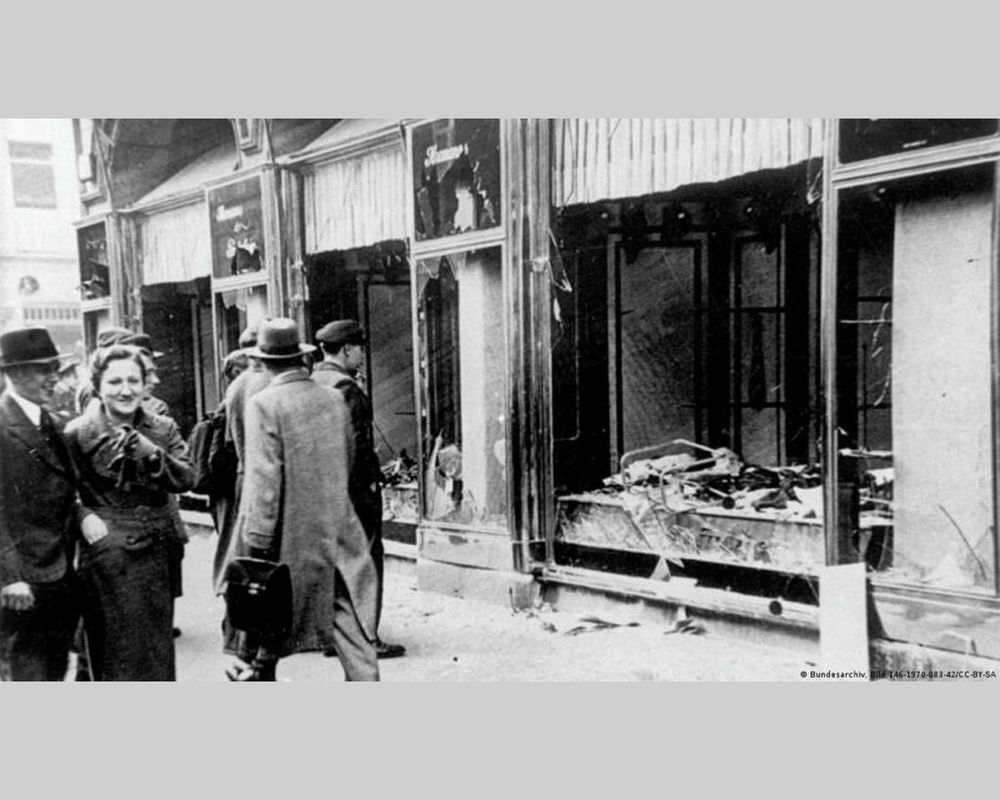

Scene after German Nazi members attacked Jewish properties across Germany and Austria on 9 and 10 November 1938

Scene after German Nazi members attacked Jewish properties across Germany and Austria on 9 and 10 November 1938

Scene after German Nazi members attacked Jewish properties across Germany and Austria on 9 and 10 November 1938

Jews were rounded up by German Nazi members on 9 and 10 November 1938

Note: This is the only letter by a Chinese I have seen that discussed the German massacre of Jews. Between 9 and 10 September 1938, German Nazi and Schutzstaffel members attacked Jewish properties across Germany and Austria, paving the road to the holocaust. This is known as the Night of Broken Glass. Six days after the incident, Lü Pi-ch’eng wrote this letter to Lung Yü-sheng.

Please look at this world, can we live here for long? If we do not seek Pure Land, where can we go? The image of Bodhisattva can be bought from Buddhist bookshops. (It does not matter whether the picture is fine or crude, it is where the sacred spirit resides.) Here is a gift of an image of Samantabhadra Bodhisattva I have painted on a sheet of paper.

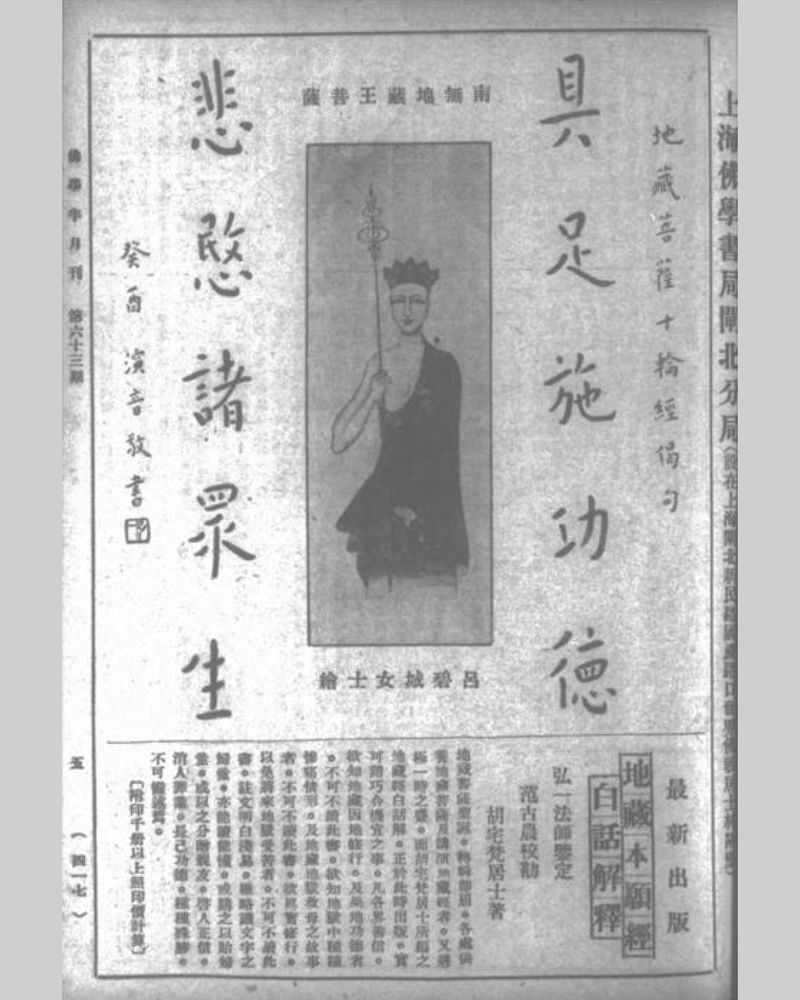

Painting of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva by Lü Pi-ch’eng published in the 63rd issue of the Biannual Journal of Buddhist Studies, 1933

Note: Lü Pi-ch’eng was also a painter of mostly Buddhist subjects. I once saw the image of a painting of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva by Lü in the 63rd issue of the Biannual Journal of Buddhist Studies (佛學半月刊), published in the 22nd year of the Republic (1933).

This was painted after I finished translating The Two Buddhist Books in Mahayana. It took me seven days.

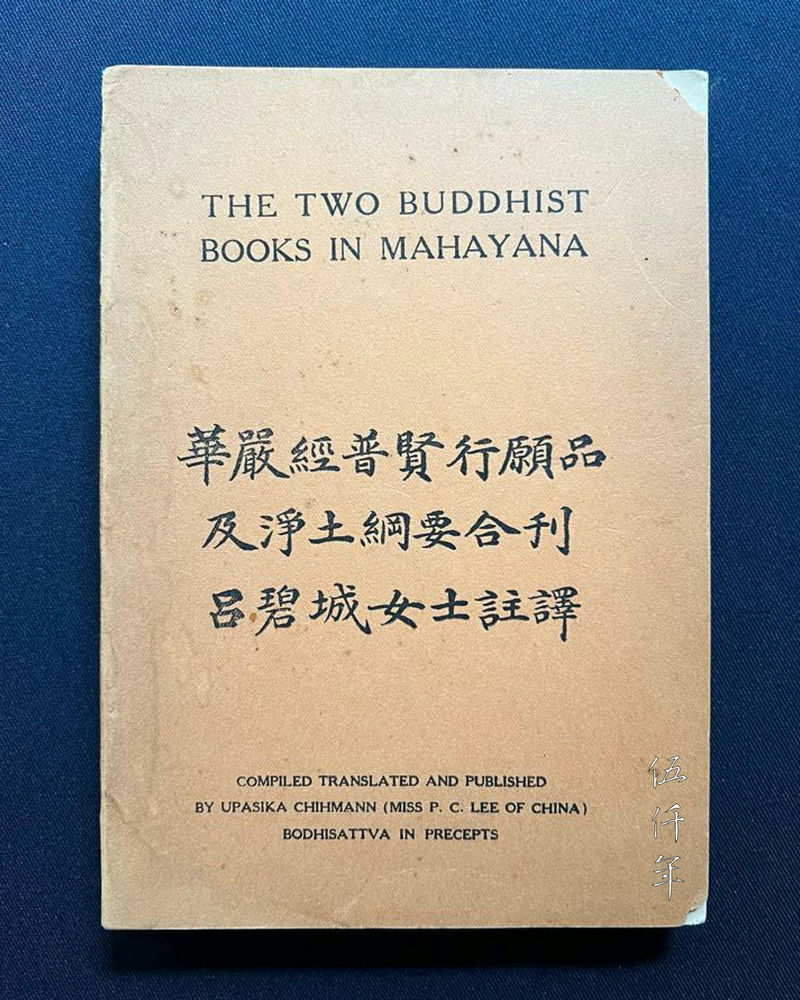

The Two Buddhist Books in Mahayana by Lü Pi-ch’eng published in 1935

Note: Lü Pi-ch’eng finished translating The Two Buddhist Books in Mahayana in October the 23rd year of the Republic (1934). It was privately printed in the following year.

In the morning of the last day of painting Samantabhadra Bodhisattva, I was astonished to see a lot of sand in the water of my wash basin. The sand rested at the bottom of the basin and it formed a lotus flower with ten petals. (The number of petals corresponded with The Ten Great Vows of Samantabhadra Bodhisattva.) The night before, I chanted the name of Bodhisattva for a long time before going to bed. When I was chanting, I diligently washed my hands. (Every time I drank tea or left my seat, I washed my hands once). Every time I washed I used fresh water. (I trusted there was no dirt on my hands.) The windows and doors were all closed when I went to bed, no one could enter. Where did the sand come from? It was a extraordinary occurrence. (This is the reason I converted to Samantabhadra Bodhisattva). This happened on 18 February. Three years ago on 18 February of the Chinese Agricultural Calendar (the equivalent of 22 March of the Gregorian Calendar), I went to the room of worship after lunch to type the Sutra translation for an hour, when I returned to the bedroom, I saw sand in the water at the bottom of the basin forming the shape of a lotus flower, with a white crane perching on it.

Note: This happened in the 24th year of the Republic (1935).

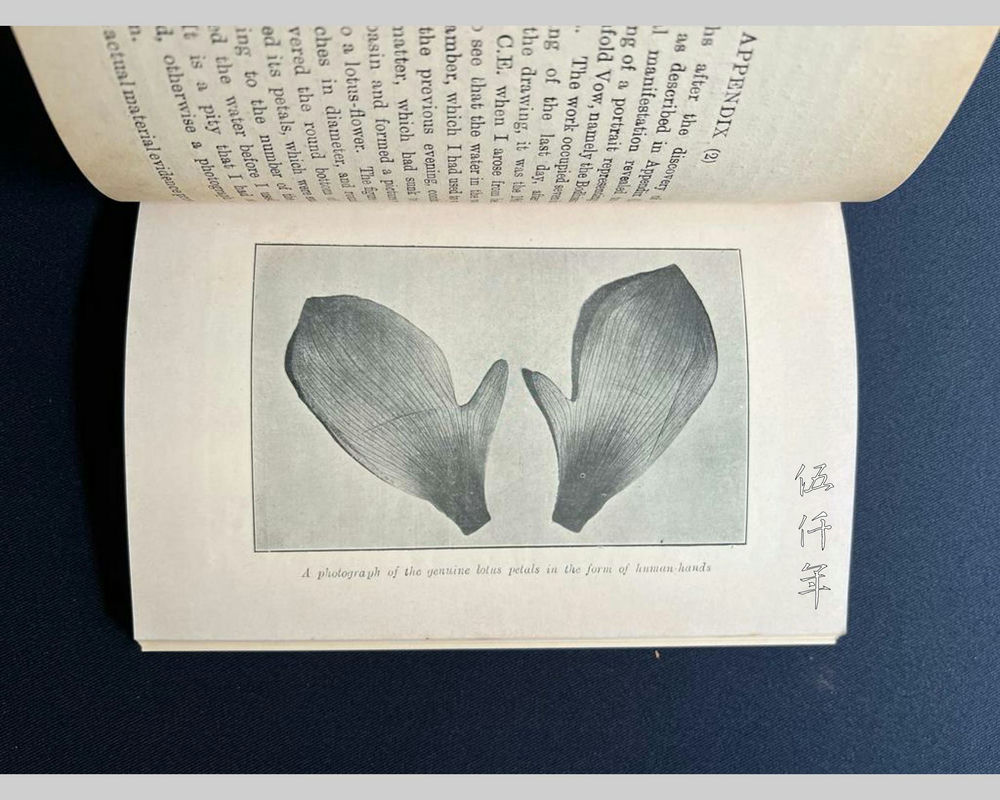

After I completed the translation, I bought some lotus flowers as offerings to Bodhisattva, and there was a pair of hand shaped lotus petals. Please accept the photograph I have attached with this letter.

A pair of hand shaped lotus petals illustrated in Appendix 2 of The Two Buddhist Books in Mahayana

Note: In Appendix 1 of The Two Buddhist Books in Mahayana, there was a detailed description of the pair of hand shaped lotus petals that Lü came across in the 23rd year of the Republic (1934). In Appendix 2 there was also a detailed description of sand inexplicably found in her wash basin forming a ten petal lotus flower. A photograph of the pair of hand shaped lotus petals was illustrated in Appendix 2.

While translating the Sutra, at one corner of my right eye, grew a small lump the size of a corn. I was worried it might become a malignant tumor. I asked my maid with the surname Chien to tie a silk thread and tighten it daily, until one day it easily fell off. I used a microscope to examine it, and saw a cyan coloured lotus flower with innumerable long overlapping petals. This microscope was borrowed from the former provincial naval commander Chiang Hsi-yüan (姜西園). He even called his wife to look at it through the microscope. My maid Chien frequently called the lump ‘treasured flesh’. I carefully kept it, but eventually lost it on my way to Singapore. The terms ‘lotus hand’, ‘lotus eye’ and others are all documented in Buddhist literature. Eight years ago on 17 November, I bought some chrysanthemum flowers to worship Bodhisattva for the first time. I prayed: ‘If I am going to be reborn in Pure Land, I beseech Bodhisattva to give me a sign.’ That night in my dream, lotus buds were sprouting from the water surface. They were thick and dense. As I inspected them, the scene changed quickly like that in a movie. In the river, there were lattices made of bamboo and wood. Two rows surfaced slightly, the top protruding from the water like the tracks of trams. (I see this in West Lake every time. It is used to define river boundaries.) The leaves of the lotuses within the tracks were opened up, each as large as one foot. In my dream I said to myself: ‘Who planted the lotus flowers in this road?’ The pronunciation of the word ‘road’ was particular loud. When I woke up, I remembered that I begged for a sign during daytime. This was the reply of Bodhisattva. Clearly he told me: ‘There is a road for you to reach Lotus Land. It sprouts only today.’ Every year on this day, I prepare a major celebration. Tomorrow will be this day again. I halted eating meat two years earlier. By 25 December this year, it will be exactly ten years. I am content with vegetables and fruits. I never think of eating meat. I never feel any deprivation. Sir, why don’t you try it? It is greatly beneficial to the economy and our morality. This is in particular the fundamental tenet for the followers of Buddhism. For the intention of Bodhisattva is to attain the great compassionate heart. Killing for meat is against the heart of Bodhisattva. The English booklet What Happens After Death? was published yesterday. I am mailing you for comment. (Please tell me when you receive it.) I have written eclectically. Please forgive such disrespect. My writing obligations have accumulated like a mountain. There is no Chinese typewriter, so in reality I don’t have spare time to draft. I courteously wish you well in your literary endeavors.

Respectfully yours,

Pi-ch’eng,

16 November.

My book is enclosed in a green envelope.”

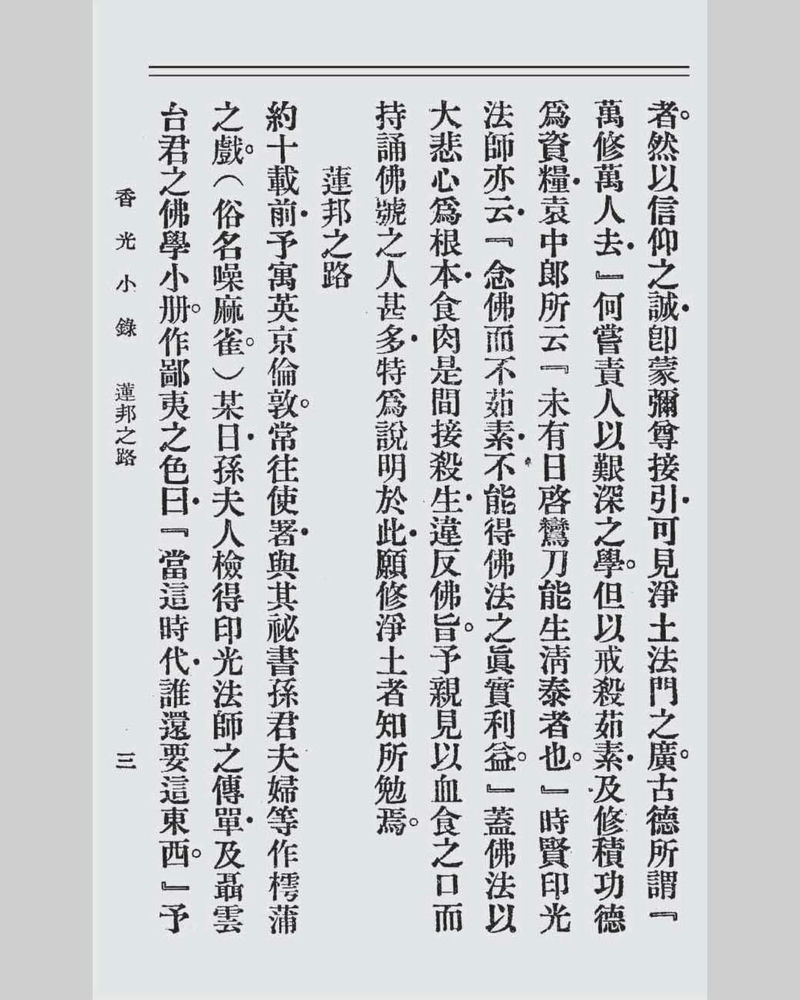

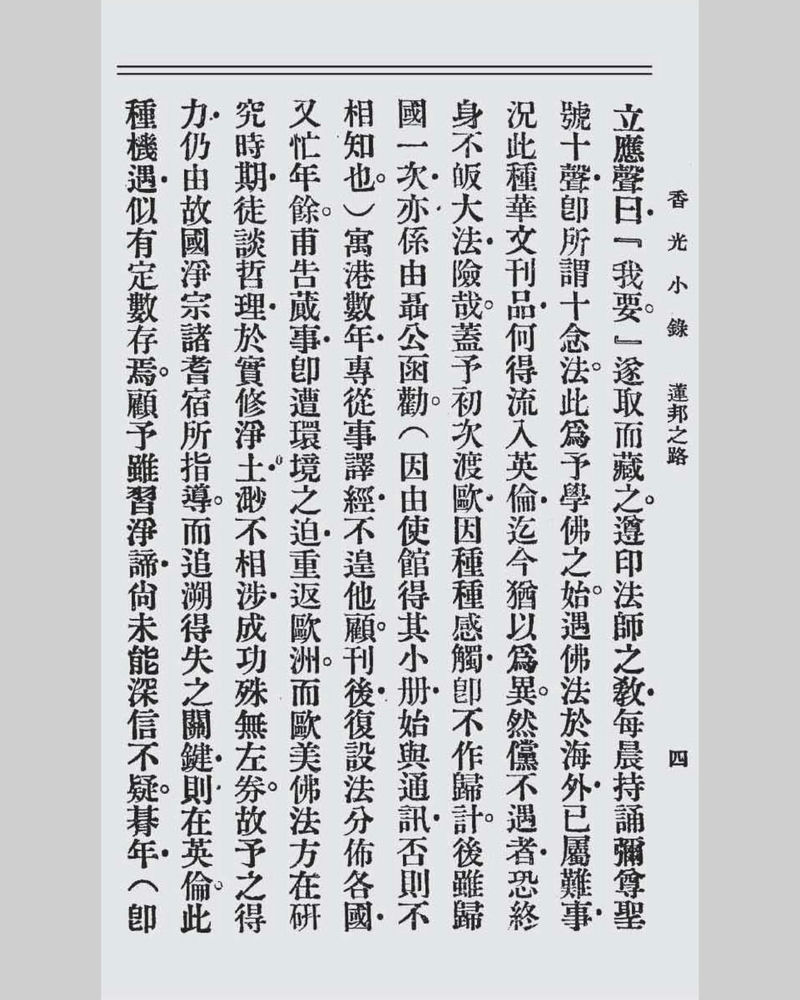

First page of The Road to Lotus Land in Hsiang-kuang hsiao-lu

Second page of The Road to Lotus Land in Hsiang-kuang hsiao-lu

Lü Pi-ch’eng became a fervent follower of Buddhism because of the dream on 17 November. This is documented in Chapter 2, The Road to Lotus Land, of Hsiang-kuang hsiao-lu. The passage reads:

“On the anniversary (1930), the Chinese Agricultural Calendar date of 17 November, commonly referred to as Amitabha Birthday, I bought three chrysanthemum flowers as offerings in front of the image of Bodhisattva. I prayed: ‘If I am going to be reborn in Pure Land, I sincerely beg Bodhisattva to give a sign.’ That night in my sleep, there were initially many disorderly dreams. During these disorderly dreams, the scene suddenly changed as if in a movie. The picture cleared. There was a wide stretch of water. Lush matters were seen on the water surface. To examine closer, they were all lotus buds densely packed. Suddenly the scene changed again. There were fences or lattices in the water. ( This should be called tuan 籪, it is used to define water boundaries. They can be found in West Lake in Hang-chou City.) They ran in parallel, the tops slightly protruding, like the tracks of trams. The lotus leaves were wide open in the middle of the tracks. In my dream I murmured: ‘Who planted these lotuses in the middle of the road?’ The pronunciation of the character ‘road’ was particularly loud and accentuated. Then I was awakened, abruptly recalling the prayer in daytime. This was no less than Bodhisattva telling me: ‘There is a road for you to reach Lotus Land. It sprouts only today.’ The structure of this dream is ingenious. Lotus is a plant grown in water, while road is built with soil and stone. By logic lotus cannot be planted in a road. However, the road in my dream was located in water, using fences or lattices to divide the water to form a road. Hence lotuses can be grown there. Not only are the vistas of the dream ingenious, the meanings are fitting, and it was an answer I received on the day. My faith in Pure Land since the day has been unwavering.

At the end of The Two Buddhist Books in Mahayana by Lü Pi-ch’eng, the story of this dream was recounted in the Appendix. However, the date of the dream was recorded as 17 November 1931. In Hsiang-kuang hsiao-lu, it was recorded as 17 November 1930. In this letter it stated: “Eight years ago, 17 November”. This can help to clarify the date as 17 November 1931.

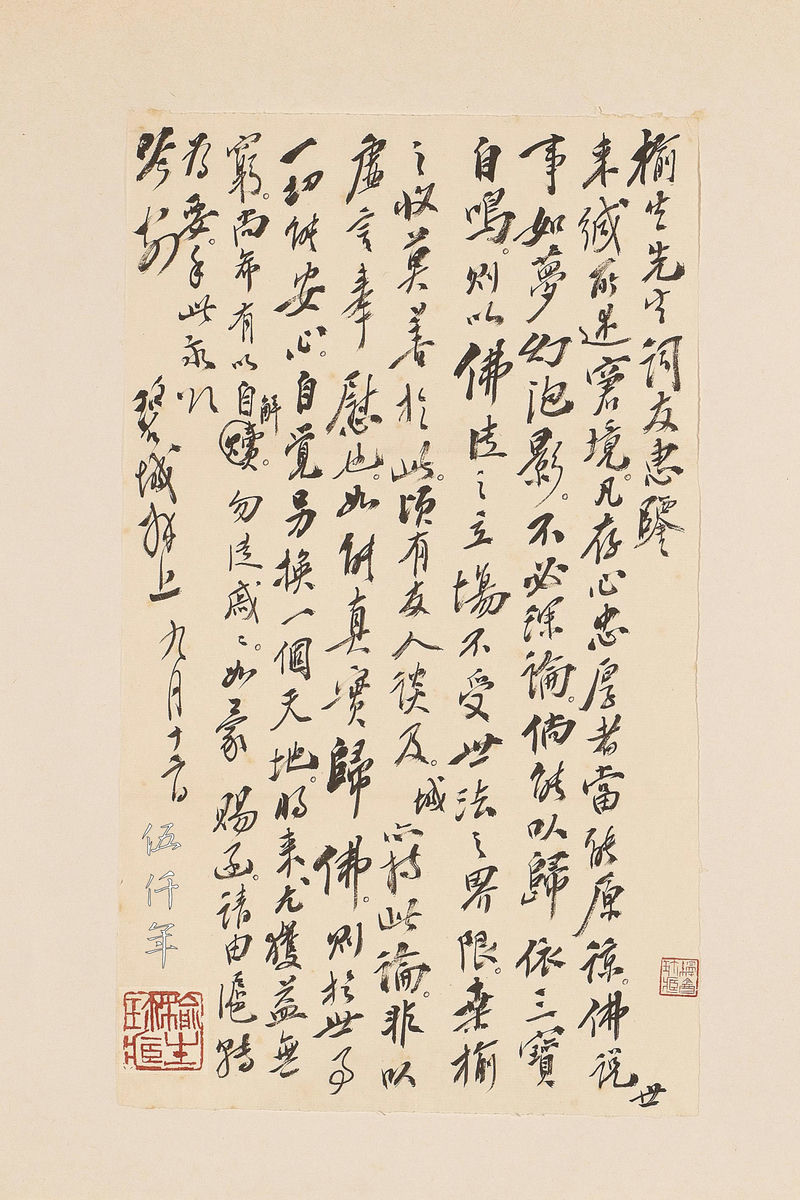

Third letter by Lü Pi-ch’eng to Lung Yü-sheng

The third letter was written on 12 September in the 29th year of the Republic (1940). It reads:

“Dear Mr. Yü-sheng my tz’u companion:

For the awkward situation you mentioned in your letter, those who are kind and sincere will be forgiving. Bodhisattva said that human affairs were like dream, illusion, bubble and shadow. Hence we do not need to discuss them in great detail. If you profess your devotion to Buddhism, the standpoints of Buddhism are beyond the limitations of human standpoints. What you have lost, you have gained in other way, and nothing can be better than this. A friend talked about this only recently and I myself hold this view too. I have not tried to console you with empty words. If you can truly become a follower of Buddhism, you can find peace in human affairs, as if you have moved into another world. You can attain infinite benefits in the future. I hope you can resolve it yourself, and do not yield to futile melancholy. If you grant me a letter in return, please send it through Shanghai, it is important. Handwritten, courteously wishing you well in your poetic endeavors.

Respectfully yours,

Pi-ch’eng,

12 September.”

Seal impressions: “Treasured and collected by Yü-sheng” and “Treasured and collected by Man-an”.

Commentary by Prof. Chang Shou-ping on third letter by Lü Pi-ch’eng

Commentaries by Prof. Chang Shou-ping also published in Treasured Letters by Modern Tz’u Poets

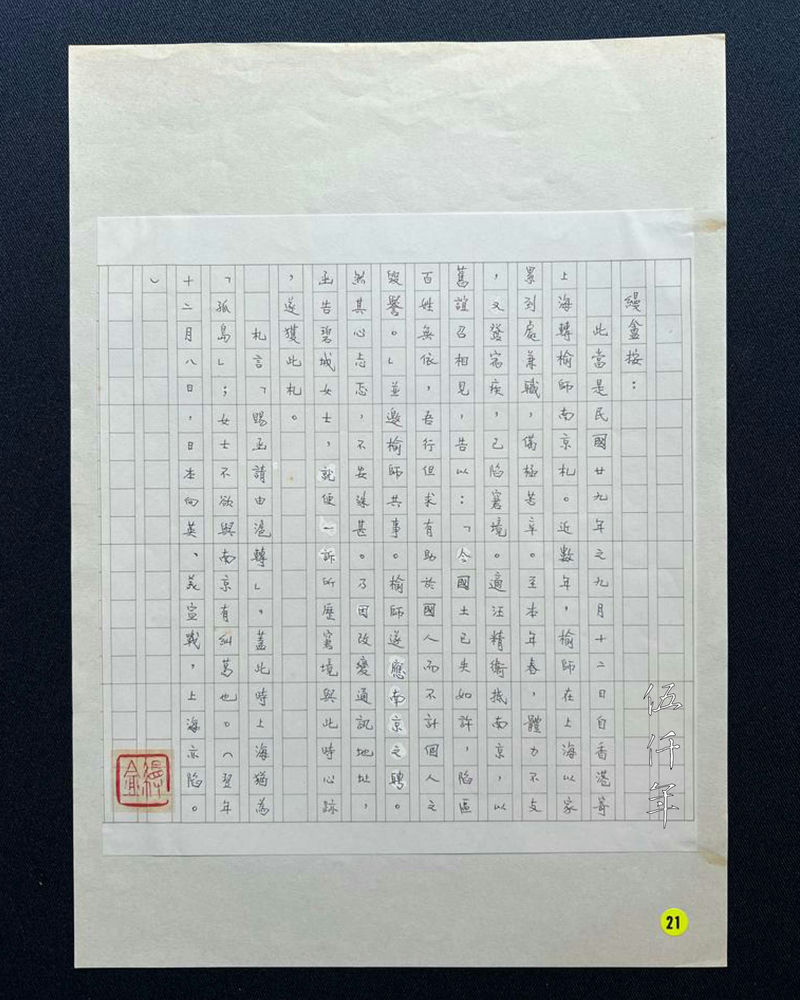

Man-an was the pseudonym or hao of Prof. Chang Shou-ping. On page 294 in Treasured Letters by Modern Tz’u Poets, Prof. Chang Shou-ping annotated this letter. He says:

“This should be a letter sent by Pi-ch’eng to my teacher Yü-sheng from Hong Kong, written on 12 September in the 29th year of the Republic (1940). It was first mailed to Shanghai and then redirected to Nanking. In the few years before 1940, my teacher undertook part time jobs wherever they were available in Shanghai, to cover the burdensome costs of living. It was most gruelling. By spring that year, he was physically exhausted. His old illness recurred and he was in dire situation. Wang Ching-wei (汪精衛) arrived in Nanking, he asked to see him for old time’s sake. Wang said to him:

‘So much territory of our country has now been lost. In the occupied territories, our countrymen have no one to depend on. Our actions only seek to assist our countrymen, and not to appraise our own fallen reputation.’

Wang invited my teacher Yü-sheng to work with him. My teacher thus accepted the appointment of the Japanese puppet government in Nanking. Yet he was perturbed and very worried. He wrote to Pi-ch’eng to inform her of the change of mailing address, and told her along the way his awkward situation and thoughts. Hence she replied with this letter.

In this letter, Lü wrote: ‘If you grant me a letter in return, please send it through Shanghai, it is important.’ At the time, Shanghai was still under the governance of the concession powers. She did not want to have anything to do with the puppet government in Nanking. (On 8 December in the following year, Japan declared war on Britain and America, Shanghai then fell.)”

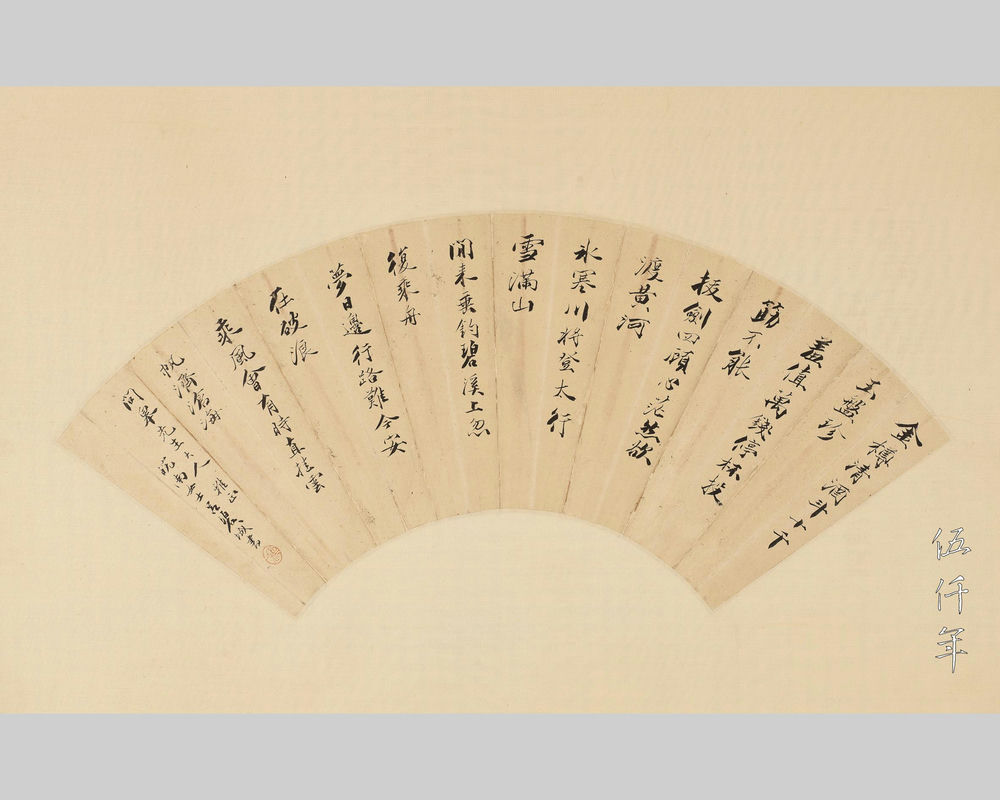

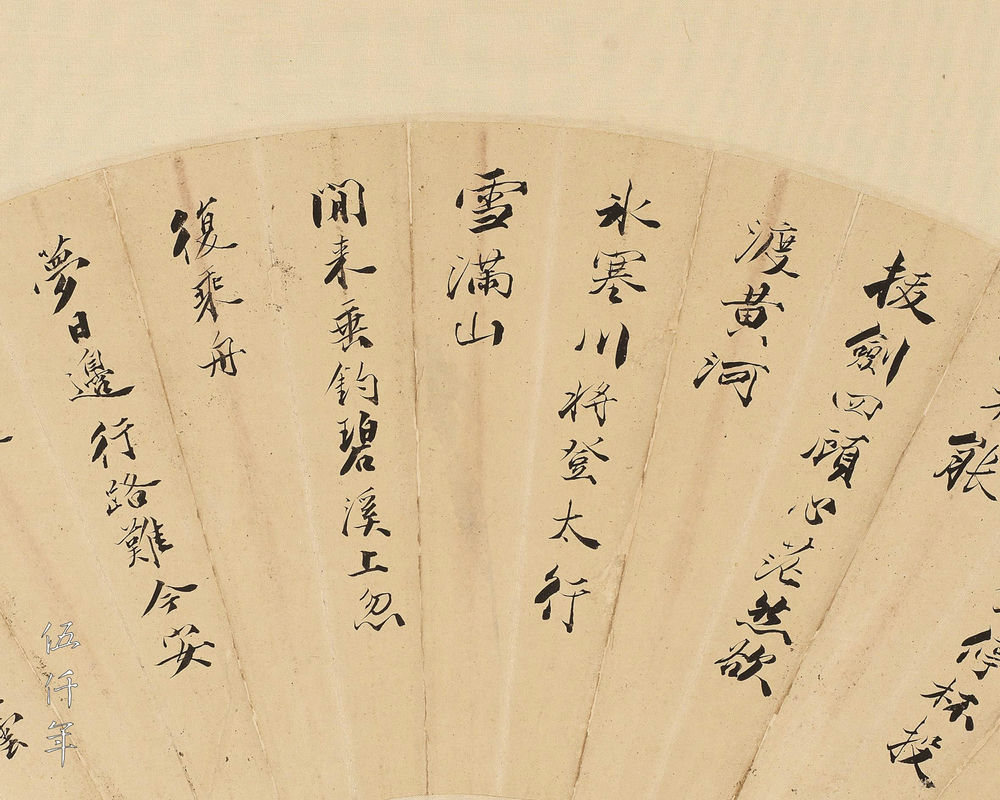

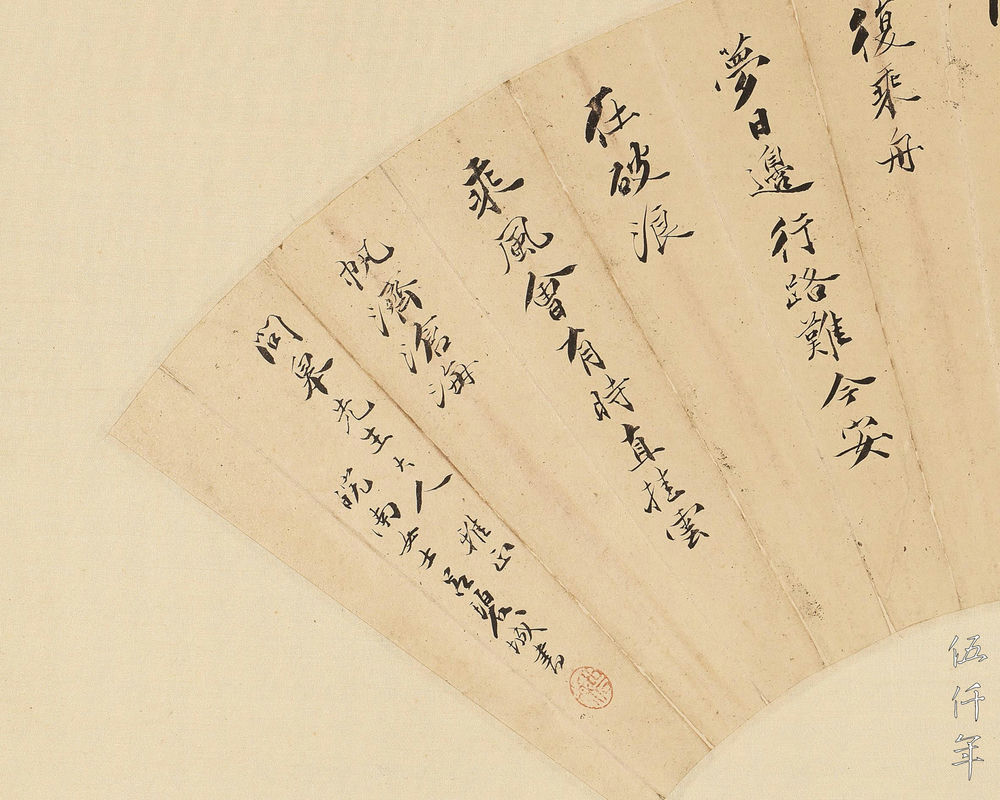

Calligraphy of the poem The Hard Road by Li Po on fan leaf by Lü Pi-ch’eng

First detail of calligraphy of the poem The Hard Road by Li Po on fan leaf by Lü Pi-ch’eng

Second detail of calligraphy of the poem The Hard Road by Li Po on fan leaf by Lü Pi-ch’eng

In my humble studio, there is a piece of calligraphy on a fan leaf by Lü Pi-ch’eng. She copied a poem, The Hard Road, by Li Po (701-762 A.D.). It reads:

Pure wine costs, for the golden cup, ten thousand coppers a flagon,

And a jade plate of dainty food calls for a million coins.

I fling aside my food-sticks and cup, I cannot eat nor drink…….

I pull out my dagger, I peer four ways in vain.

I would cross the Yellow River, but ice chokes the ferry;

I would climb the Taihang Mountains, but the sky is blind with snow;

I would sit and poise a fishing pole, lazy by a brook-

But I suddenly dream of riding a boat, sailing for the sun…… Journeying is hard,

Journeying is hard.

There are many turnings-

Which am I to follow?……

I will mount a long wind some day and break the heavy waves

And set my cloudy sail straight and bridge the deep, deep sea.

For the refined rectification of Mr. Wen-kao.

Wan-nan Nü-shih (皖南女士) Lü Pi-ch’eng.”

Seal impression: “Pi-ch’eng”.

The above is a translation by Robert Kotewall and Norman L. Smith from the Penguin Book of Chinese Verse, published in 1962.

Lü Pi-ch’eng, first row fourth from the right, at the Internationaler Tierschutz Kongress in Vienna 1929

Outside the Internationaler Tierschutz Kongress in Vienna 1929

On 13 May 1929, Lü Pi-ch’eng gave a speech at the international conference in Vienna which was organized by the Internationaler Tierschutz Kongress. The title of the speech was: There Should be No Slaughter. Part of it reads:

“The way China protects animals may perhaps be of interest to the world. To trace this belief, it started very early and was formed by three sources. The first is Buddhism. The second is Confucianism. The third is the ancient legal system. The aim of Buddhism is to prohibit all killings. The instruction of Confucianism is to refrain from cruelty and killings. There is a saying: ‘Having seen them alive, he cannot bear to see them die; having heard their dying cries, he cannot bear to eat their flesh.’ As for the ancient legal system, the rules are distributed in the System of Rites of the Chou dynasty nearly three thousand years ago. There are sayings: ‘The emperor does not kill a cow for no reason, the high official does not kill a sheep for no reason, the commoner does not kill a pig for no reason. They are only killed for sacrifices, banquets and festivities when there are no other alternative. For daily food, it should be only vegetables, rice and flour.’

Since the great revolution of China in 1911, reforms and developments have been the main preoccupations. The civilization inherited from ancient China is subsequently nearly wiped out. However, I recently read in a Chinese newspaper that European merchants applied to the Tientsin municipal government for a license to annually export nine million pounds of beef and ten thousand cows. It was rejected by the government, explaining that cows were used for farming alone in China, they should not be slaughtered. This ancient rule has now been revived.

Since we have been discussing in great detail the many ways to protect animals, yet by the end, we still accept that they are to be killed. How can we explain this point? Prohibiting the torture of animals is only part of my aspiration, it does not fully realize my belief. No matter how remote is the day of accomplishing my aspiration, even if it takes a thousand years, I vow to begin this movement today. For humans to kill animals, it is totally based on the strong assaulting the weak. I believe it is a huge disgrace to world civilization. Before President Abraham Lincoln started the war to free the enslaved black people, their status was no better than animals. Those trading enslaved black people did not think their conduct was absurd or wrong. This is exactly similar to our killings of animals now, mistakenly thinking that this is natural. I dare say that world peace will never be kept by international treaties or arrangements, it is maintained by the human heart. This human heart is nurtured by the spirits of justice, righteousness and compassion. For these spirits, the further away from selfishness the higher their values. To promote them from humans to animals, their values are even higher. If the primeval character of humans can be dissolved in these spirits, then an aura of peace will fill the earth, this will be the day when world peace truly becomes established. The abstinence from killing animals is not just my personal notion, it represents all the peace lovers and vegetarians of China.”

Reading this speech a hundred years later, it can awaken the astray and heal the deaf. Lü Pi-ch’eng synthesized knowledge and action to propagate abstinence from killing animals in China and abroad. At that time, not only was there no other Chinese female engaged in this international endeavor, Chinese males also willingly submit to her authority. Her ambition was certainly more than the artistry of tz’u lyrics. For this reason I used the title Lü Pi-ch’eng, Mother of the Animal Protection Movement in China. I only wish that this biographical account has not failed to elucidate the ambition and travail of her life.

Portrait of Lü Pi-ch’eng in Shanghai

Related Contents:

The 80th Death Anniversary of the Republican Tz’u Poetress Lü Pi-ch’eng (呂碧城), by P’an Hui-lien