Chen Man-sheng (陳曼生) from the Ch'ing dynasty is celebrated for his poetry, calligraphy, painting and seal. The teapots and desk objects he made in I-hsing purple clay are fine, elegant, and devoid of any speck of vulgarity. Connoisseurs view them as the rarest treasures. We present an I-hsing clay water vessel by Chen Man-sheng that imitated the form of the T'ang dynasty headwall of the well engraved by Monk Ch'eng-kuan (澄觀). This is a record of the Buddhist soul of an eminent monk, and an advocacy of the spiritual refinement practiced by the literati of the classical world.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

Over 1,210 years ago, in the 6th year of the Yüan-ho reign of the T’ang dynasty, corresponding to 811 AD, Monk Ch’eng-kuan (澄觀法師) excavated a well at Ling-ling Temple outside the West Gate of Li-yang County in Kiangsu province. He had some inscriptions and a gāthā verse by Kuo T’ung (郭通), a distinguished gentleman from an earlier age, engraved on the headwall of the well, which later came to be known as the “Ch’eng-kuan Well.” In the fifth year of the Yüan-yu reign of the Sung dynasty, or 1090 AD, Pao-en Temple was built outside the East Gate of Li-yang County. Ch’ing dynasty gazettes mentioned that the well was located in this temple, giving rise to the view that there may be two Ch’eng-kuan wells. Whether Monk Ch’eng-kuan actually carved two wells, or whether the original well was later moved to Pao-en Temple, has long been a matter of debate. During the Chia-ch’ing reign of the Ch’ing dynasty, when Chen Man-sheng (陳曼生) served as the district magistrate of Li-yang, he saw the Ch’eng-kuan Well at Pao-en Temple. Hence in ping-tzu (丙子) year, the 21st year of the Chia-ch’ing reign, or 1816 AD, he made an I-hsing tzu-sha (purple-clay) water vessel, modelling it after the well of which Ch’eng-kuan engraved the headwall.

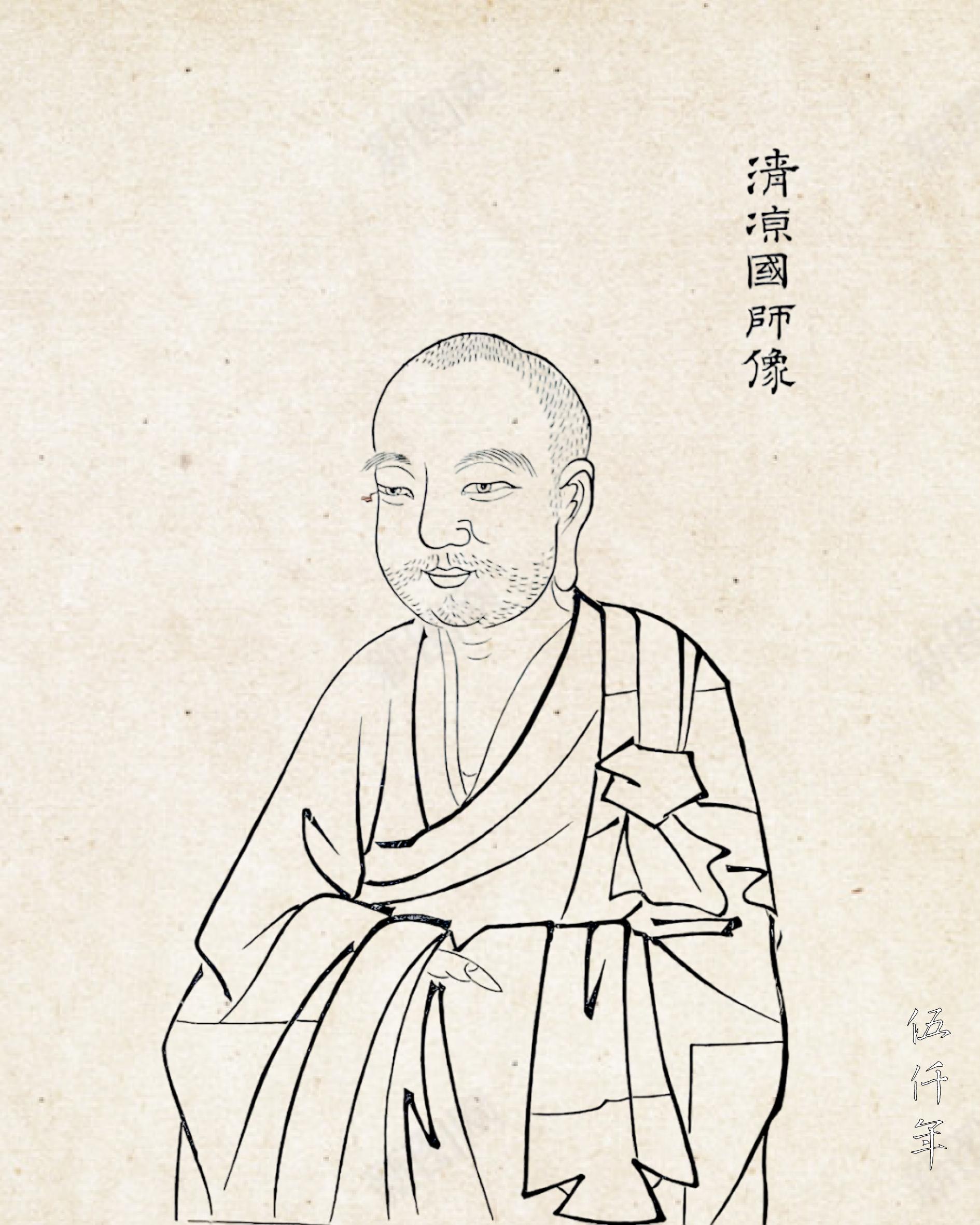

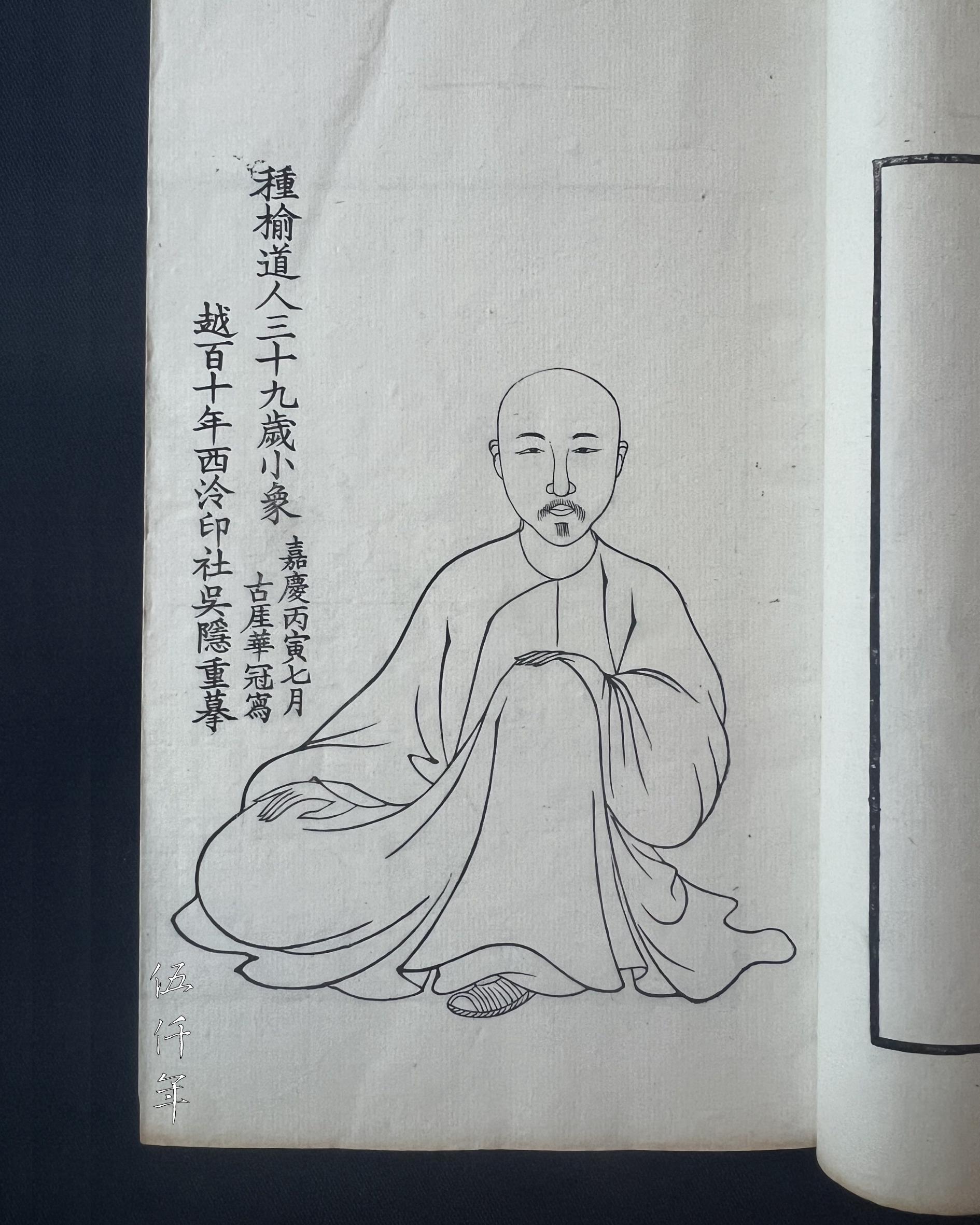

Portrait of Monk Ch’eng-kuan, also known as Ch’ing-liang

Monk Ch’eng-kuan, also known as the State Preceptor Ch’ing-liang (清涼), bore the surname Hsia-hou (夏侯), and the tzu he used was Ta-hsiu (大休). He was a native of Hui-chi in Yüeh-chou in the T’ang dynasty. He was born in the 26th year of the K’ai-yüan reign, corresponding to 738 AD, and died in the 3rd year of the K’ai-ch’eng reign, corresponding to 838 AD.

An extract from the text of Stele of Imperial Eulogy for the State Preceptor Ch’ing-liang reads:

“…Having finished his words, he passed away. Ch’eng-kuan and his students lived through nine reigns, and he served as teacher to seven emperors. He was one hundred and one years old, his monastic life spanned eighty-eight years. He was nine feet four inches tall, his hands hung below his knees, his eyes shone at night, and in daytime he did not blink. He was very talented, and his voice resonated like a bell. Emperor Wen-tsung recognized the reverence his ancestors held for Ch’eng-kuan, so upon his death, the emperor mourned him by suspending his duties in court for three days. Officials and commoners alike wore white mourning garments, and his body was enshrined in a stupa at Mount Chung-nan. Not long after, a monk from India arrived at the palace and recounted that he had seen two emissaries flying in the air in Tsung-ling Mountain. Stopping them with a mantra, he asked who they were. They replied: ‘We are divine attendants from the Hall of Mañjuśrī in Northern India. We are traveling east to fetch a tooth relic from the Huayan Bodhisattva (Ch’eng-kuan). It will be returned to our land for enshrinement, and we bear an instruction to open the stupa.’ Indeed, after further investigation, one tooth was found missing and only thirty-nine remained. When his body was cremated, his sarira was luminous and translucent, his tongue had the colour of a red lotus. He was bestowed the same posthumous title that of State Preceptor Ch’ing-liang.”

Monk Ch’eng-kuan served as teacher to seven emperors, namely, Tai-tsung (代宗), Te-tsung (德宗), Shun-tsung (順宗), Hsieh-tsung (憲宗), Mu-tsung (穆宗), Ching-tsung (敬宗), and Wen-tsung (文宗). This was the highest honour attainable by a subject. When Ch’eng-kuan died, Emperor Wen-tsung suspended court affairs for three days, while officials and commoners alike donned white mourning garments, akin to the mourning protocol applicable to the death of an emperor. This is a testimony to his great prestige.

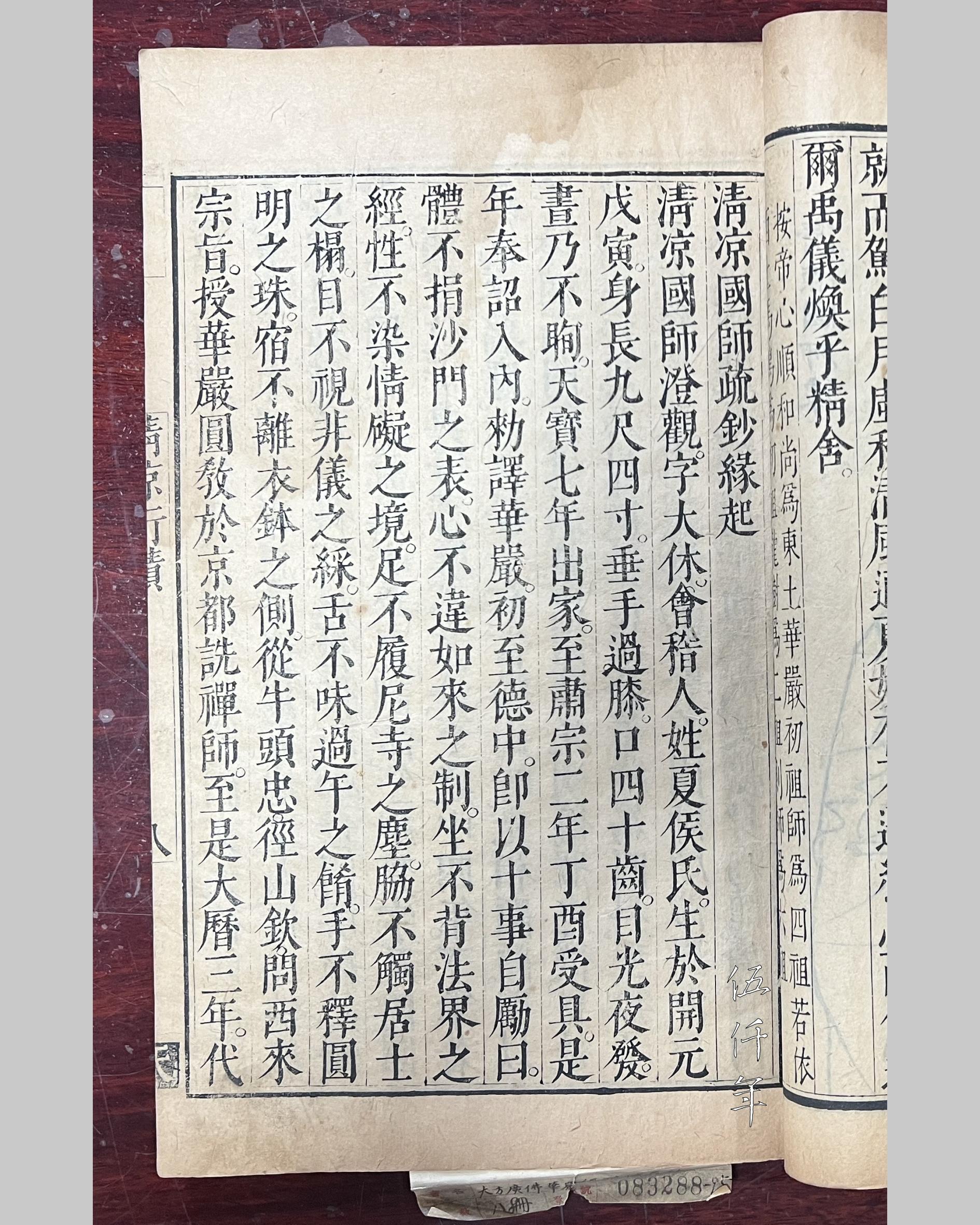

First page of The Genesis of Commentaries by the National Preceptor Ch’ing-liang

The Genesis of Commentaries by the National Preceptor Ch’ing-liang records his personal precepts, the lineage of his teachers and his scholarly works. Here is an excerpt:

“He was nine feet four inches tall, his hands are hung below his knees, he had forty teeth, his eyes shone at night, and in daytime he did not blink. He became a monk in the 7th year of the T’ien-pao reign, and received full ordination in dingyou (丁酉) year, the 2nd year of the Su-tsung reign. In the same year, he was summoned by imperial decree to the palace and commanded to translate the Avataṃsaka Sutra, also known as Hua-yen Ching (華嚴經). In the early days of the Te-tsung reign, he set forth these ten vows to discipline himself:

Body does not abandon the deportment of a monk.

Mind does not transgress the rules of Tathāgata.

Meditation does not contradict Dharma sutras.

Nature is not tainted by attachments.

Feet does not step on the ground of nunnery.

Ribs do not touch the couch of a lay person.

Eyes do not see in contravention of decorum.

Tongue does not taste food after noon.

Hands do not let go of prayer beads.

Sleep next to robe and alms bowl.

He studied under Monk Chung (忠) and Monk Ching-shan (徑山) from the Buddhist Sect of Niu-t’ou (牛頭), enquiring after the principles of Buddhism. He received Avataṃsaka teaching, also known as Hua-yen teaching, from the Zen Monk Shen (詵) in the capital. This took place in the 3rd year of the Ta-li reign. Emperor Tai-tsung later summoned him to the palace, where he discoursed on the translations of the Tripiṭaka. He was bestowed the honorific title Jun-wen Ta-te (潤文大德). Afterwards, he retired to the Great Hua-yen Temple in Wu-t’ai Mountain. He was well-read, particularly well-versed in the Confucian Classics, different schools of philosophy, the philological traditions of China, Buddhist scriptures, Sanskrit script, traditional Indian philosophy and their five branches of knowledge, and other Buddhist works. There was nothing he did not master. In the 4th year of the Chien-chung reign, he began writing his commentaries … and the work was completed in four years.”

The phrase “He studied under Monk Chung and Monk Ching-shan from the Buddhist Sect of Niu-t’ou” means that Monk Ch’eng-kuan studied under the sixth patriarch Hui-chung (慧忠) of the Buddhist Sect of Niu-t’ou, who was born in 683 AD and died in 769 AD. Ch’eng-kuan also studied Avataṃsaka Sutra under the Zen Monk Shen, also known as Fa-shen (法詵), or Monk Ta-shen (大詵和尚), who was born in 718 AD and died in 778 AD. The phrase “the work was completed in four years” refers to his work Commentaries on the Avataṃsaka Sutra (華嚴經疏鈔).

Ch’eng-kuan was the fourth patriarch of the Hua-yen school, he mastered the teachings of various Buddhist sects and produced an extensive body of writings. His ten vows came to be known as the Ten Vows of Ch’ing-liang, which to this day continue to inspire and guide many Buddhist practitioners.

Headwall of well with engravings by Monk Ch’eng-kuan now preserved in Li-yang

Front cover of the 1896 edition of Li-yang County Gazette

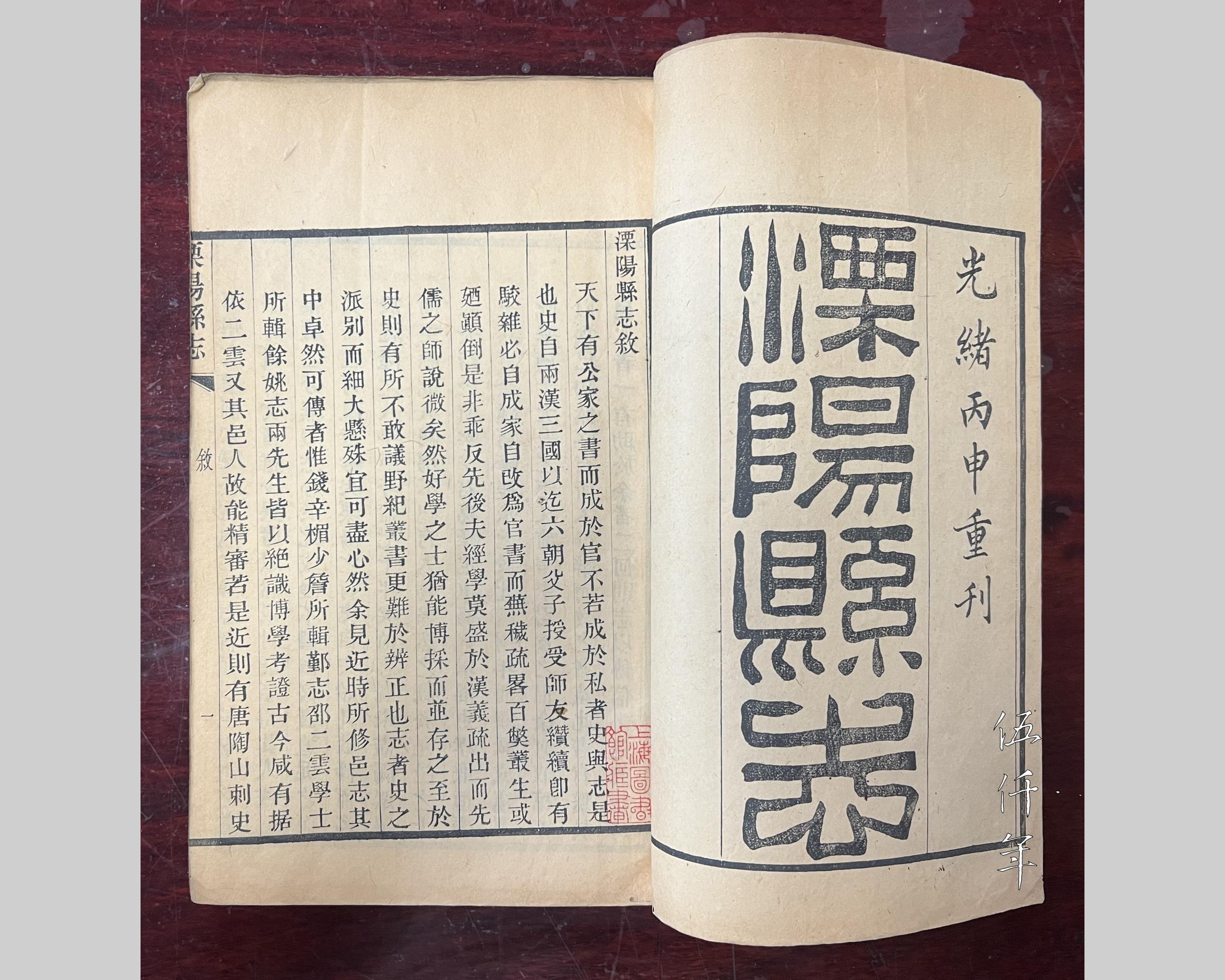

Title page of Li-yang County Gazette

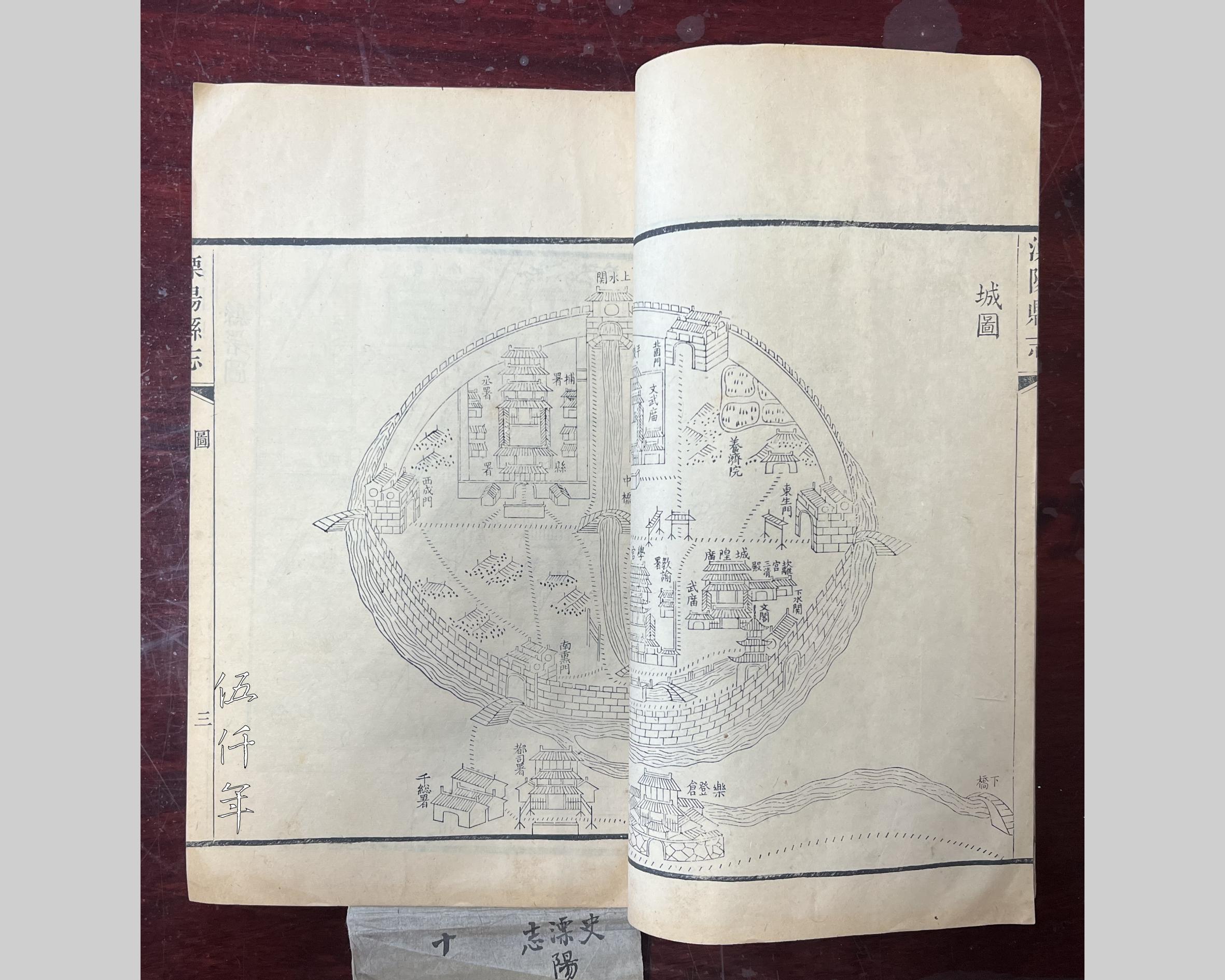

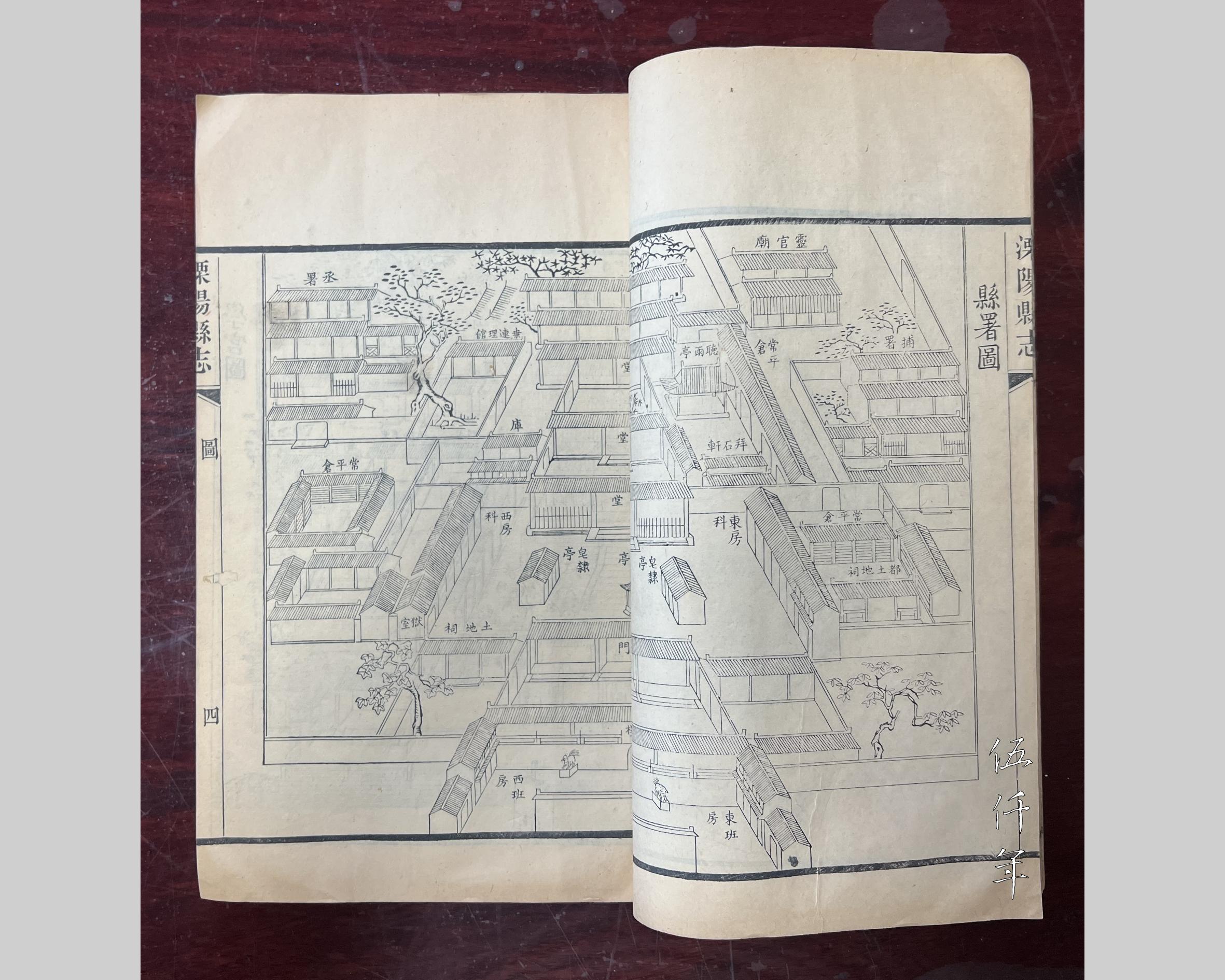

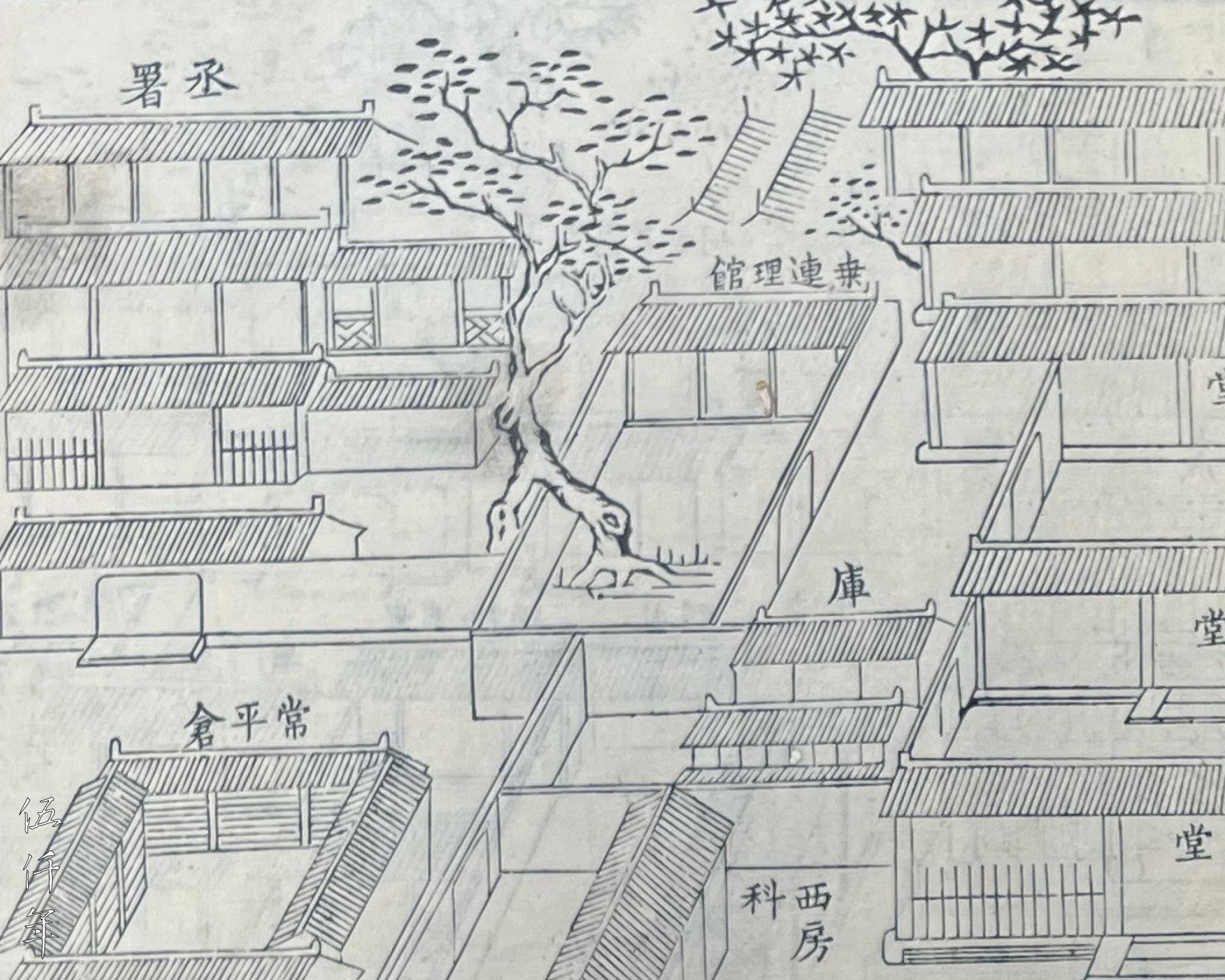

Illustration of Li-yang townscape in Li-yang County Gazette

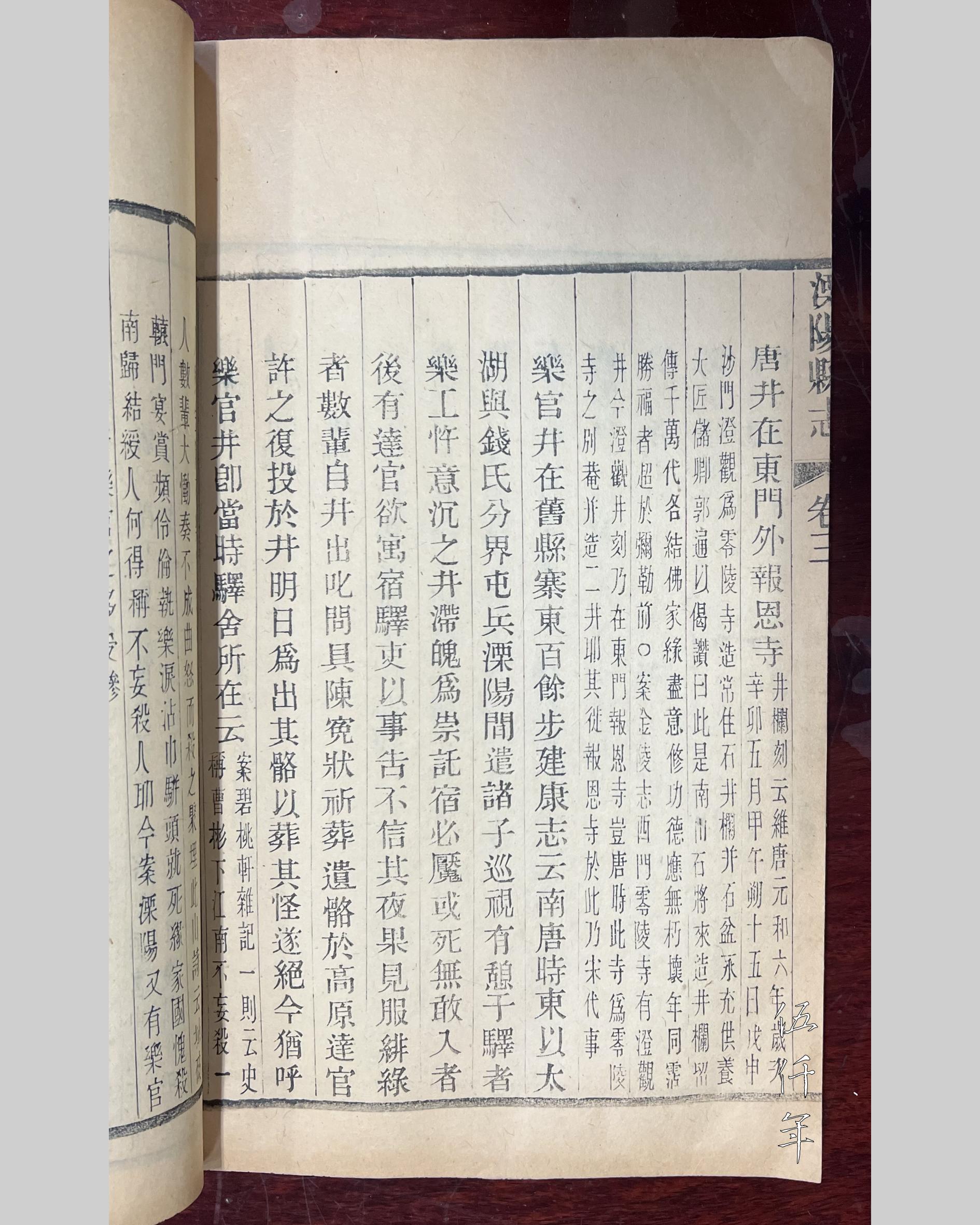

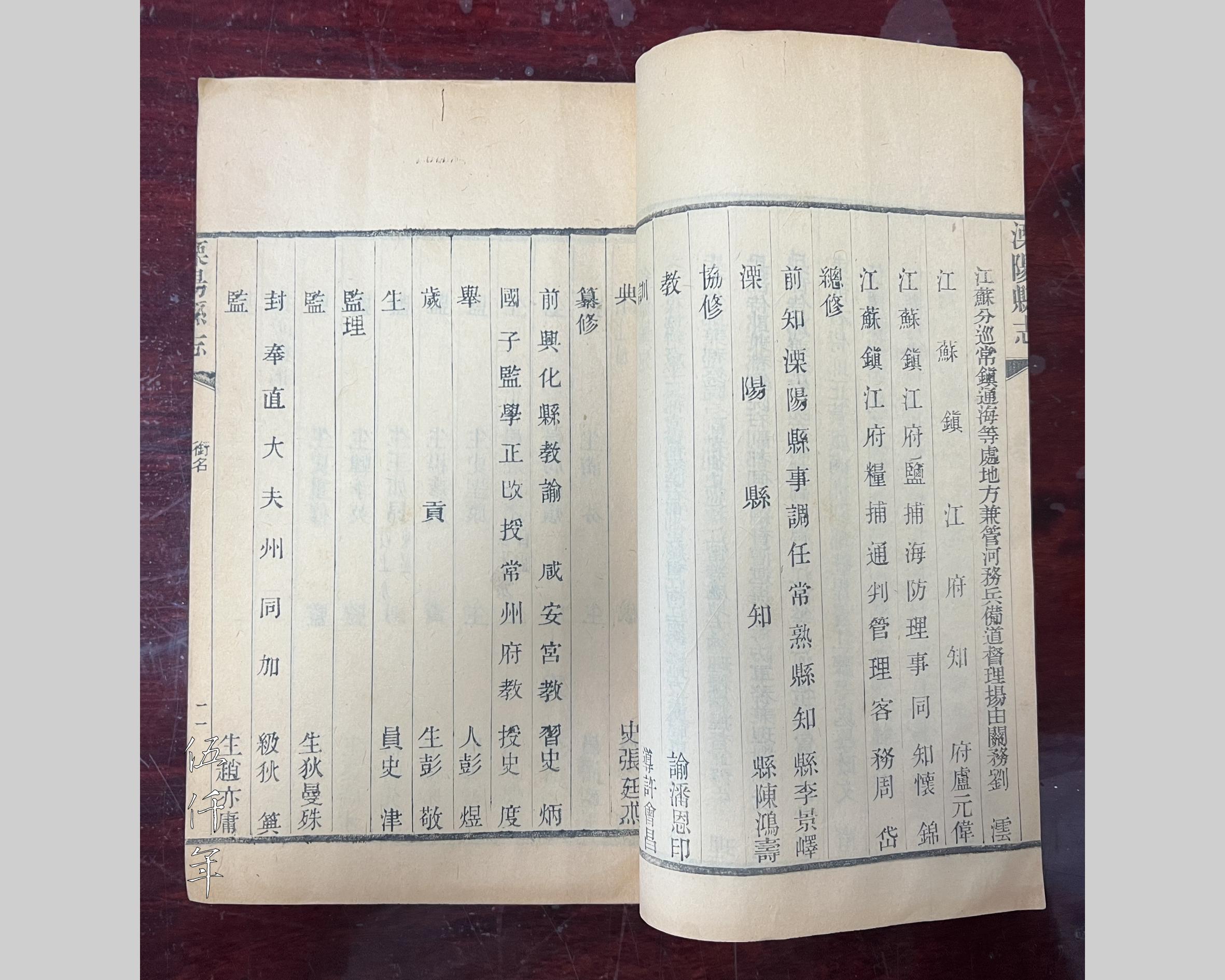

First inside page of Li-yang County Gazette

The headwall of the well inscribed by Ch’eng-kuan is recorded in detail in the Li-yang County Gazette, published in ping-shen (丙申) year of the Kuang-hsü reign. It says:

“The T’ang dynasty well is located at Pao-en Temple outside the East Gate. The headwall of the well was engraved with these words:

‘In hsin-mao (辛卯) year, the 6th year of the Yüan-ho reign of the T’ang dynasty, in chia-wu-shou (甲午朔) month of May, on wu-shen (戊申) day of the fifteenth, Monk Ch’eng-kuan commissioned the erection of the stone headwall and base for the well in Ling-ling Temple, to be used forevermore by the public.

The Chief Minister for the Palace Buildings Kuo T’ung (郭通), offered a gāthā verse:

Stone from Mount Nan

To build this headwall.

Countless generations

Buddhist karma tied.

Toil on for merit,

It will not decay.

Blessings now shared,

Surpass that of Buddha.

According to Chin-ling Gazette, Ch’eng-kuan Well was located in Ling-ling Temple outside the West Gate. However, the engraved Ch’eng-kuan Well is now at Pao-en Temple. Could it be that some time in the T’ang dynasty, this temple was a separate retreat or branch under the administration of Ling-ling Temple, and that two wells were thus constructed? The relocation of Pao-en Temple occurred in the Sung dynasty.”

Whether Ch’eng-kuan engraved one well or two wells is not conclusively determined by the gazettes. If he did in fact engrave two wells, the inscriptions would likely differ, and should it not bear the name of the separate retreat or branch?

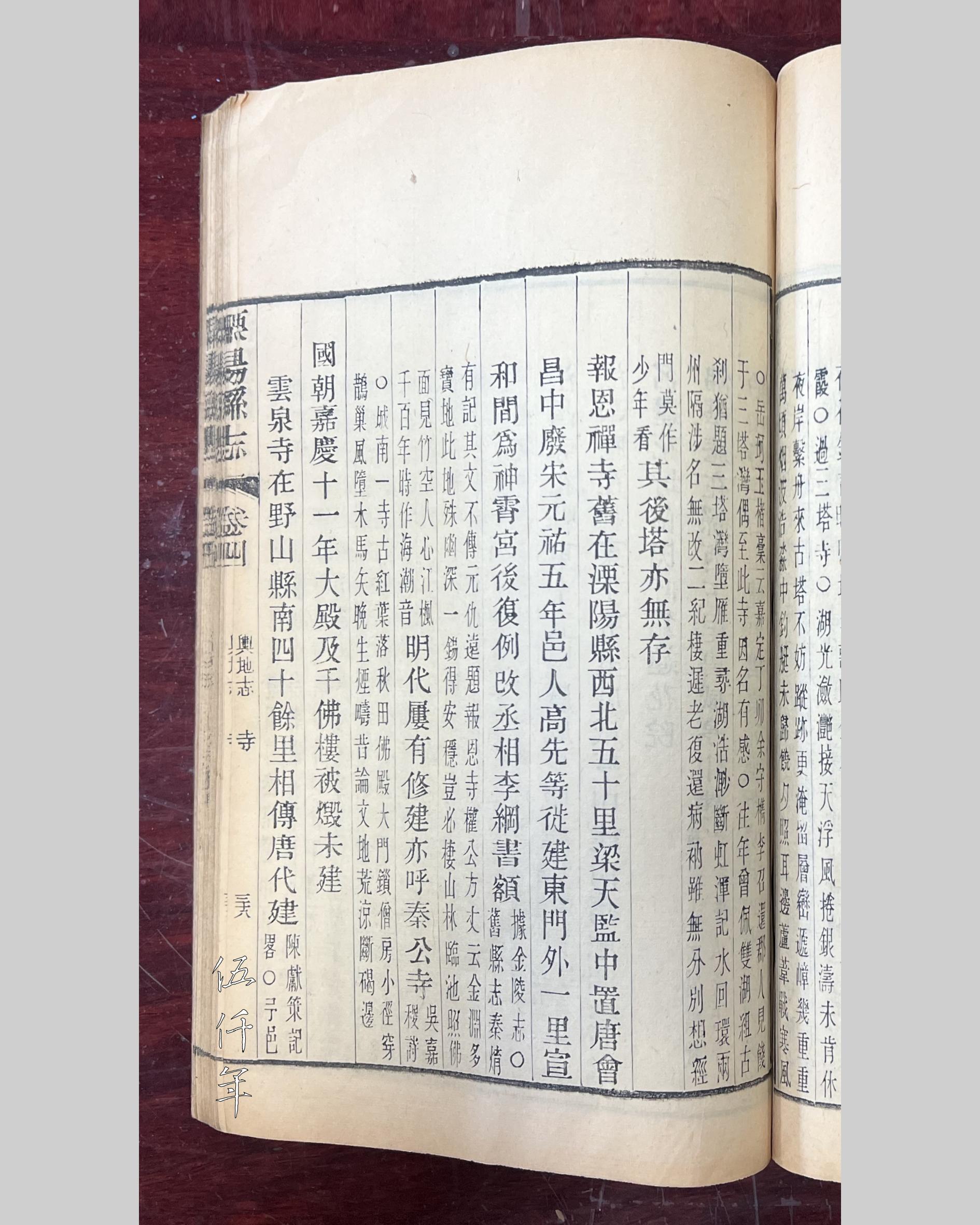

Second inside page of Li-yang County Gazette

The Li-yang County Gazette also records:

“Pao-en Temple was originally fifty miles northwest of Li-yang County. It was built in the middle of the T’ien-chien reign in the Liang dynasty, and abandoned in the middle of the Hui-ch’ang reign in the T’ang dynasty. In the 5th year of the Yüan-yu reign in the Sung dynasty, a local resident Kao Hsien (高先) and others relocated and rebuilt Pao-en Temple one mile outside the East Gate. During the Hsüan-ho reign, it became Shen-hsiao Abbey, and later the horizontal plaque of the building was substituted by one written by Chancellor Li Kang (李綱). The temple underwent several repairs during the Ming dynasty and was also called Ch’in-kung Temple.”

During the T’ang dynasty, Ling-ling Temple was located at the West Gate of Li-yang County, while the original site of Pao-en Temple was fifty miles northwest of Li-yang County. If it had served as a separate retreat or branch of the temple, it would be easy to access.

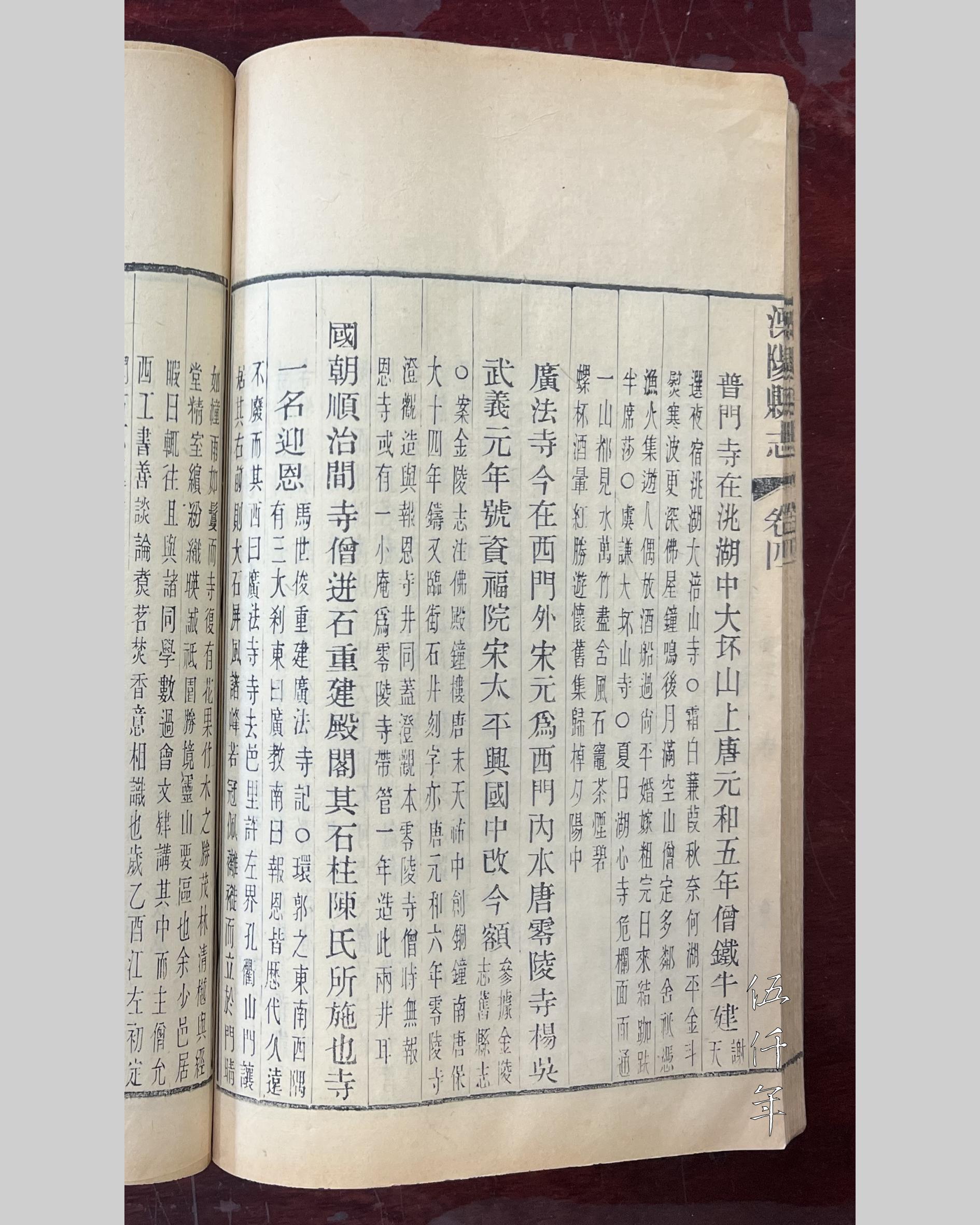

Third inside page of Li-yang County Gazette

The Li-yang County Gazette further records:

“According to the old Chin-ling Gazette, Kuang-fa Temple is now outside the West Gate, during the Sung and Yüan dynasties, it was inside the West Gate. Originally, it was named Ling-ling Temple in the T’ang dynasty. In the 1st year of the Wu-i reign of the Yang-wu dynasty, it was named Tzu-fu Yüan. In the middle of the T’ai-p’ing-hsing-kuo reign in the Sung dynasty, it changed the horizontal plaque of the building to this name.

In the footnotes of Chin-ling Gazette, the Buddha hall and bell tower were built in the middle of the T’ien-yu reign in late T’ang, the bronze bell was casted in the 14th year of the Pao-ta reign in Southern T’ang, and the street-facing engraved stone well was made in the 6th year of the Yüan-ho reign of the T’ang dynasty by Ch’eng-kuan of Ling-ling Temple, identical to the well at Pao-en Temple. Ch’eng-kuan was originally a monk at Ling-ling Temple, at that time there was no Pao-en Temple, perhaps there was only a small hermitage under the supervision of Ling-ling Temple, which was the reason he constructed two wells in the same year.”

Name list of compilers and assistant compilers of Li-yang County Gazette

The theory of Ch’eng-kuan building two wells became even plainer. However in A Supplement to Li-yang County Gazette, under the entry: “The stone well by Monk Ch’eng-kuan of the Yüan-ho reign is in Pao-en Temple outside the East Gate”, A Stone Well Song by Shih Ping (史炳) was reproduced. The opening lines read:

There lived a curious T’ang monk Ch’eng-kuan,

Who built a heavenly pagoda in old Ssu-chou.

To and fro he visited Ling-ling Temple at Li-yang

And carved a gāthā verse deep into the well.

Which year did the well move to Pao-en Temple?

One big and one small their sizes so vary.

The shafts are different and didn’t quite fit,

Yet a hundred men carried it from the west.

The song notes a hundred men were allocated to move the well, though it is unclear when it happened. Shih Ping was a native of Li-yang. As he collaborated with Chen Man-sheng to compile the Li-yang County Gazette, he would have been well-acquainted with local history. The account that the Ch’eng-kuan Well was originally located in Ling-ling Temple, and then it was moved to Pao-en Temple, is supported by this anecdotal poem.

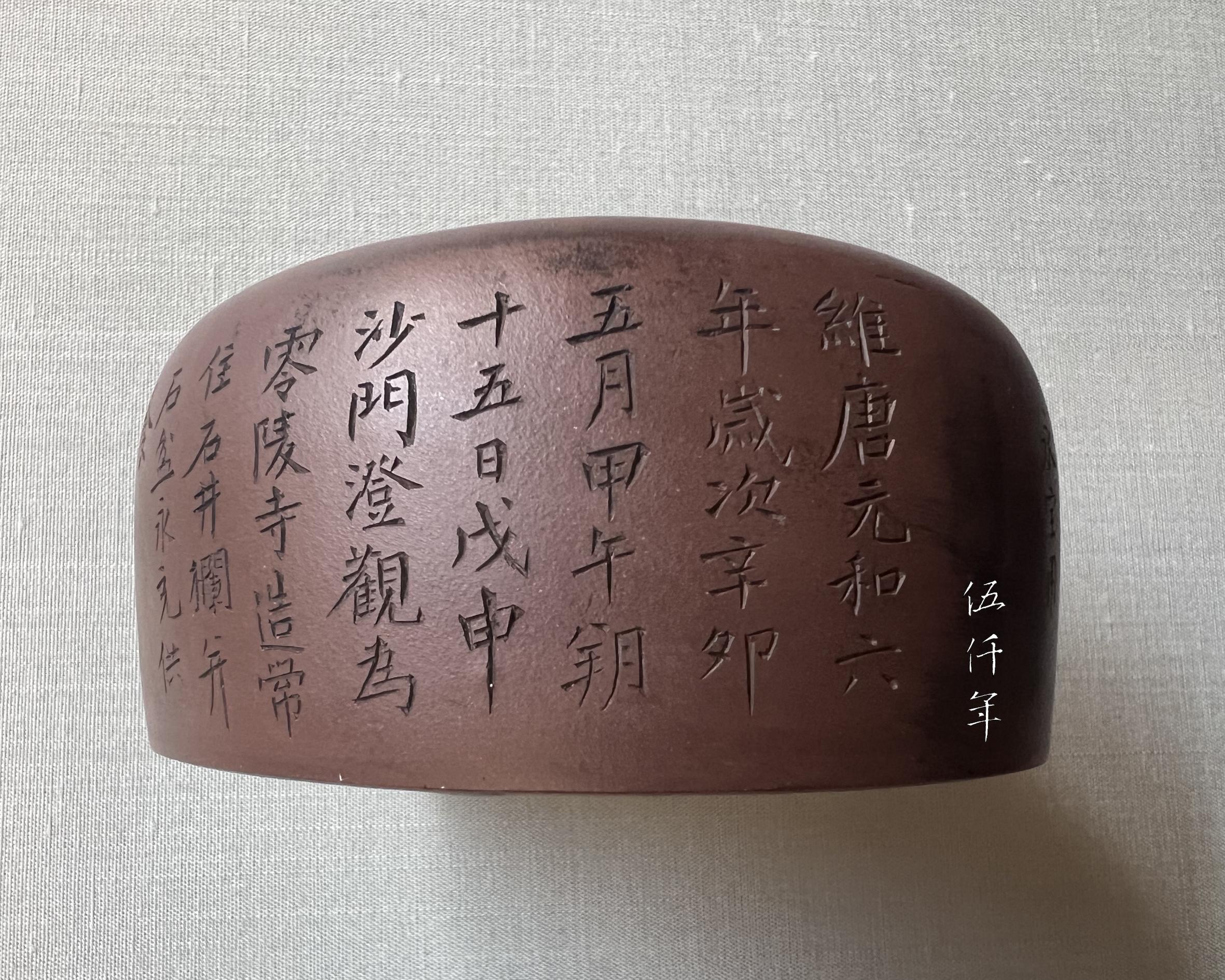

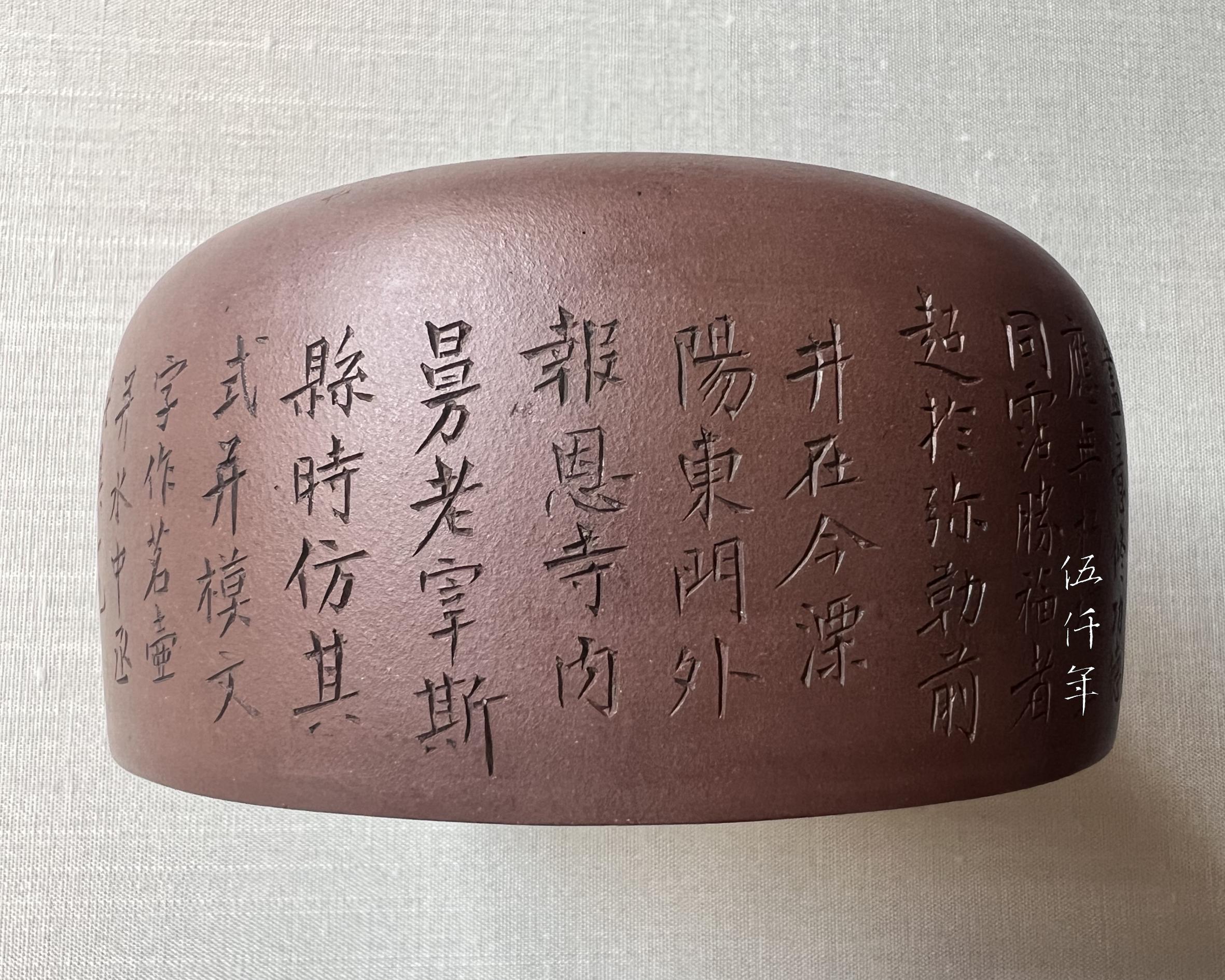

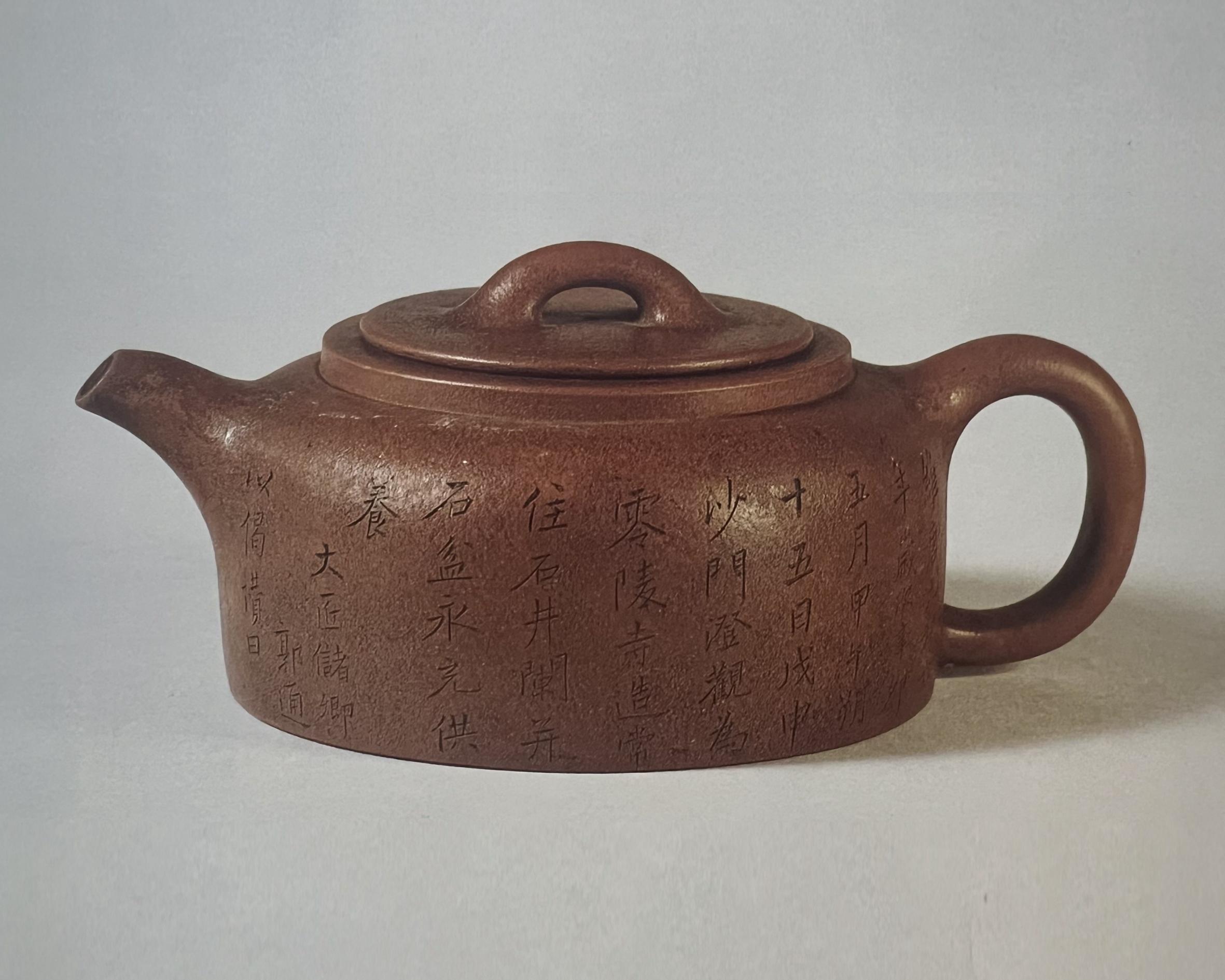

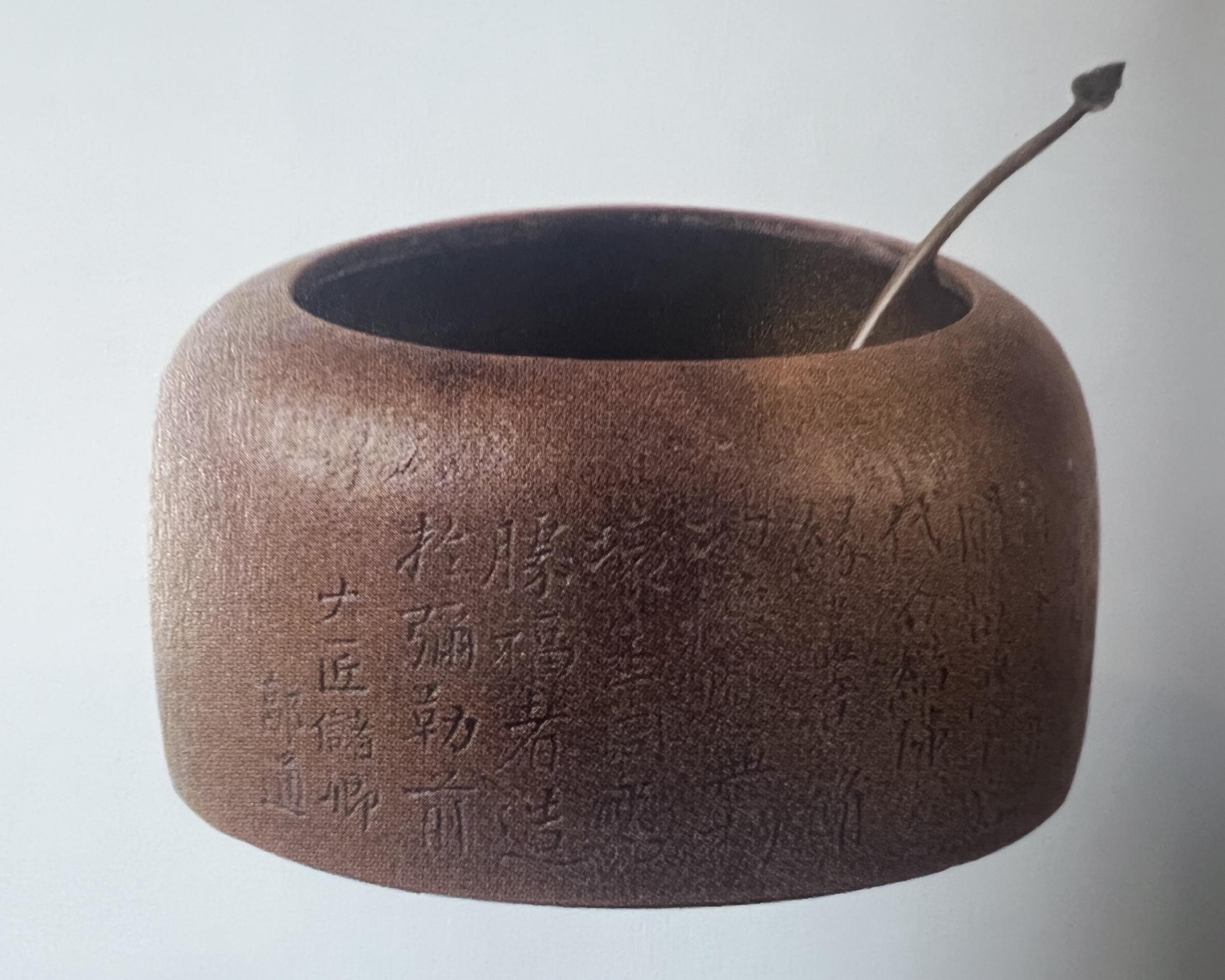

First side view of I-hsing clay water vessel resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in the Studio of Prunus Ode Collection

Second side view of I-hsing clay water vessel resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in the Studio of Prunus Ode Collection

Third side view of I-hsing clay water vessel resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in the Studio of Prunus Ode Collection

Fourth side view of I-hsing clay water vessel resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in the Studio of Prunus Ode Collection

In my collection, there is an I-hsing purple clay water vessel designed by Chen Man-sheng that was modelled after the T’ang dynasty Ch’eng-kuan Well. It was crafted by Yang P’eng-nien (楊彭年), with an inscription engraved by Kao Jih-chun (高日濬). It was dedicated to Chu Wei-hsieh (朱為燮). I have cherished it as the rarest treasure for a few decades. The water vessel resembling the T’ang dynasty well is a sacred artefact of an illustrious monk, a precious gem in a scholar’s studio, a masterpiece of purple-clay ware, and the only extant water vessel by Chen Man-sheng.

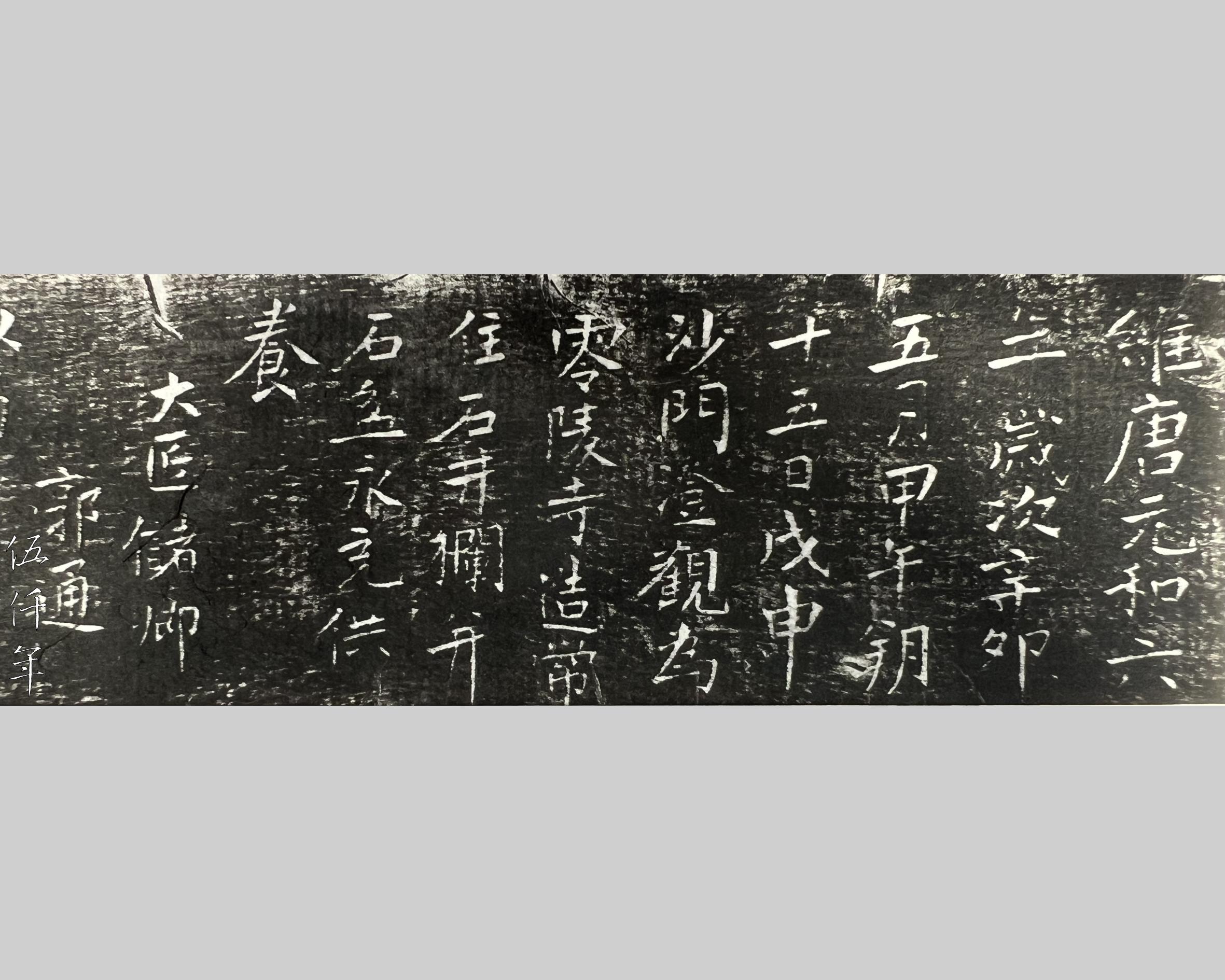

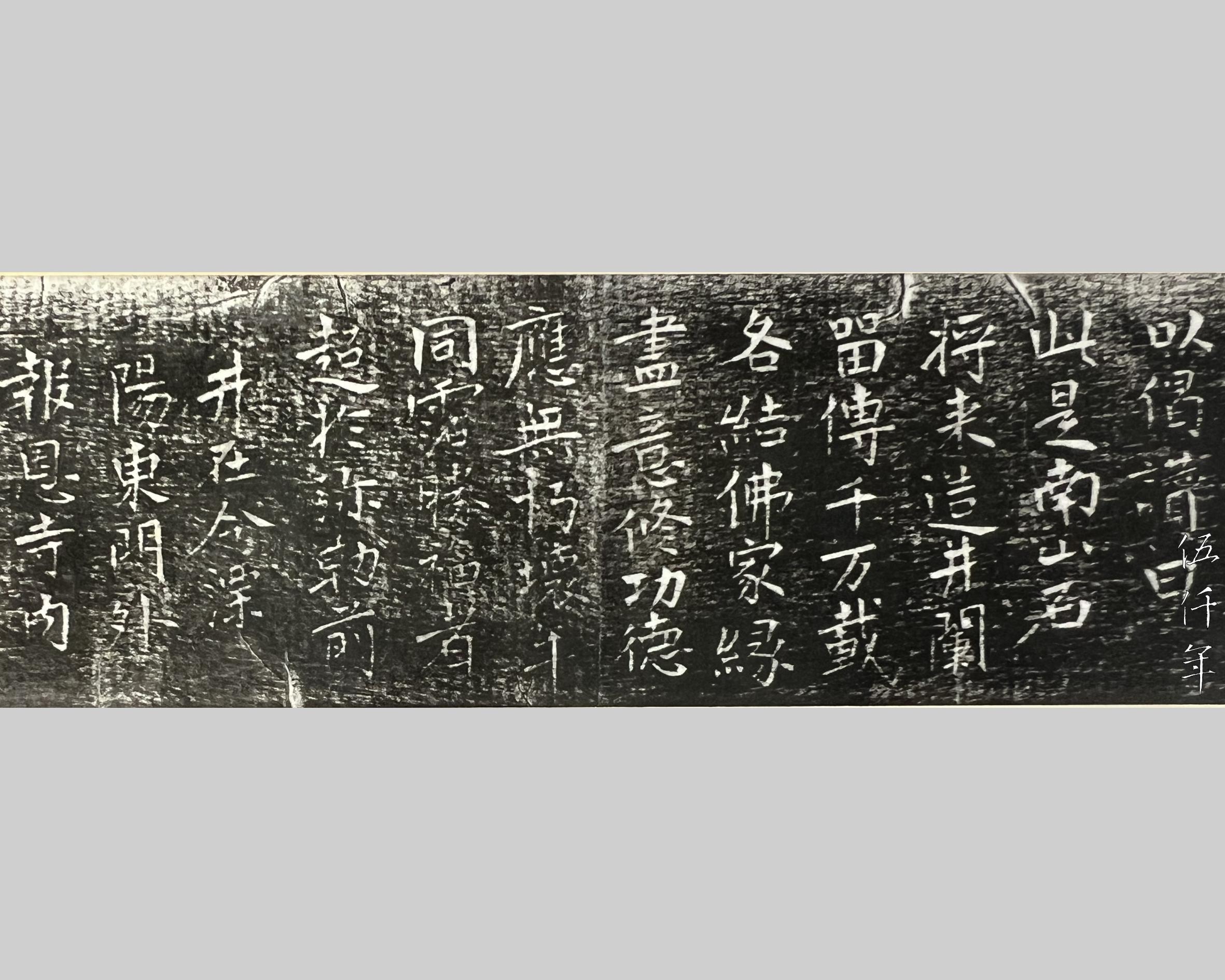

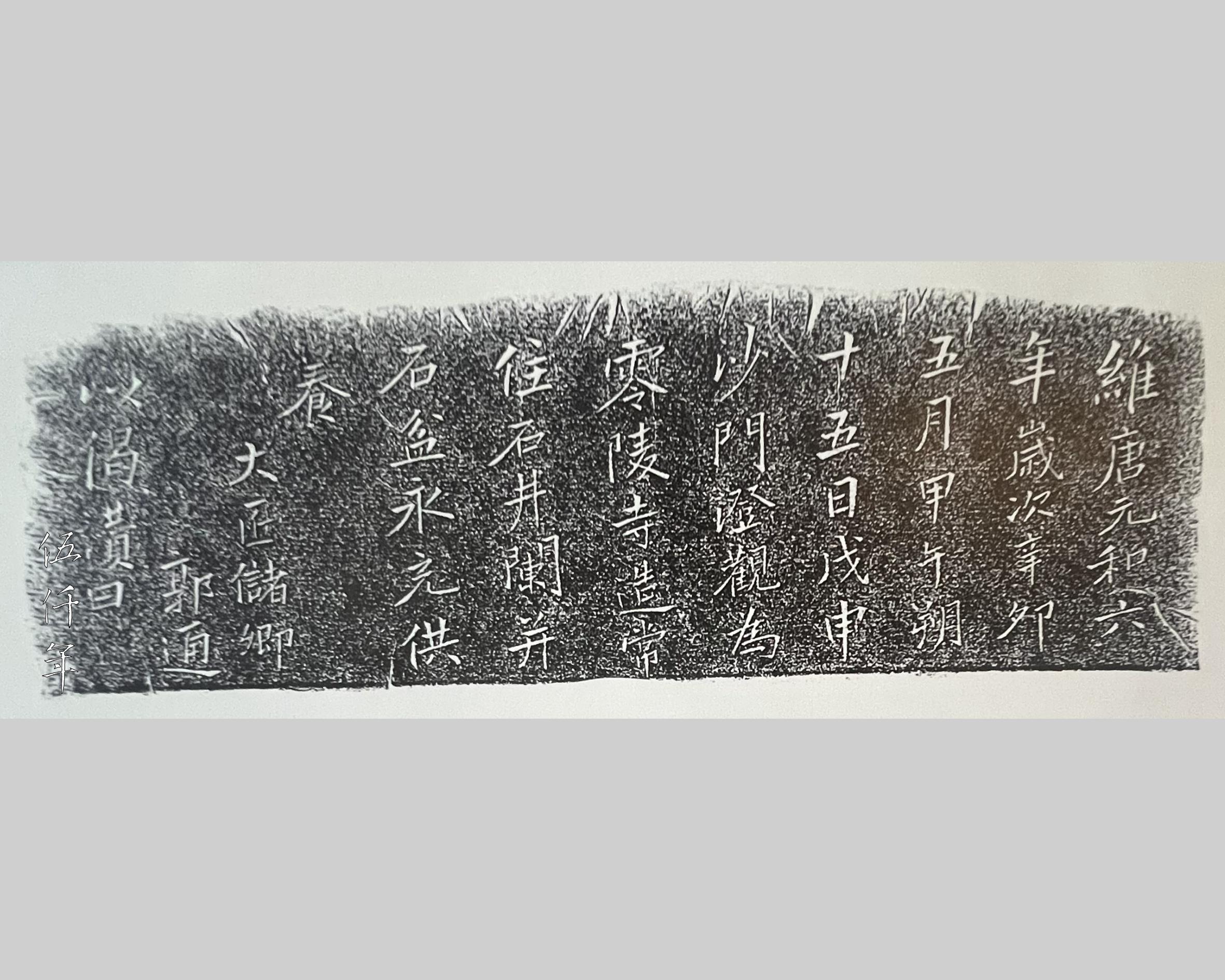

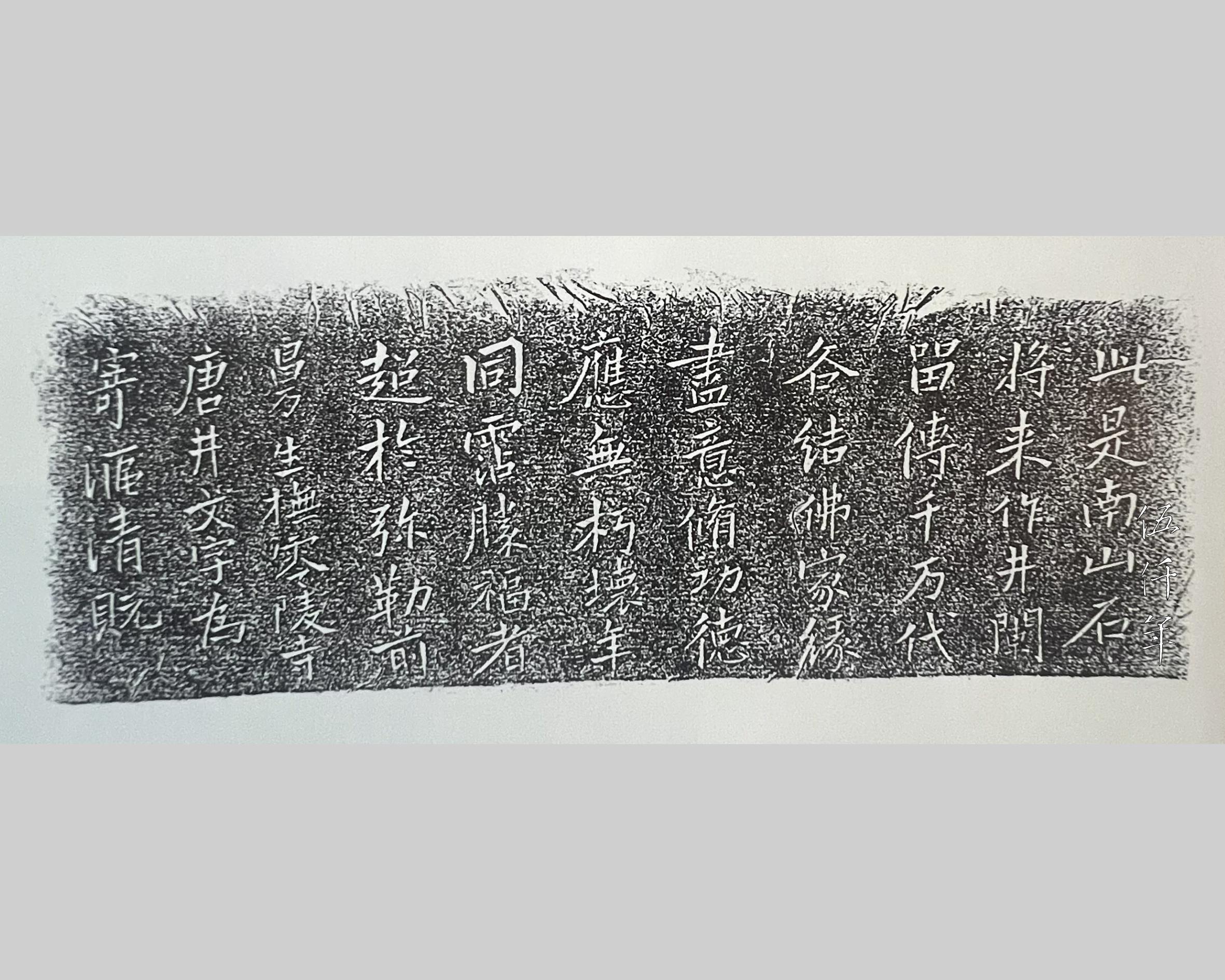

The inscription on the water vessel reads:

“In hsin-mao (辛卯) year, the 6th year of the Yüan-ho reign (811 AD) of the T’ang dynasty, in chia-wu-shou (甲午朔) month of May, on wu-shen (戊申) day of the fifteenth, Monk Ch’eng-kuan commissioned the erection of the stone headwall and base for the well in Ling-ling Temple, to be used forevermore by the public.

The Chief Minister for the Palace Buildings Kuo T’ung offered a gāthā verse:

Stone from Mount Nan,

To build this headwall.

Countless generations,

Buddhist karma tied.

Toil on for merit,

It will not decay.

Blessings now shared,

Surpass that of Buddha.

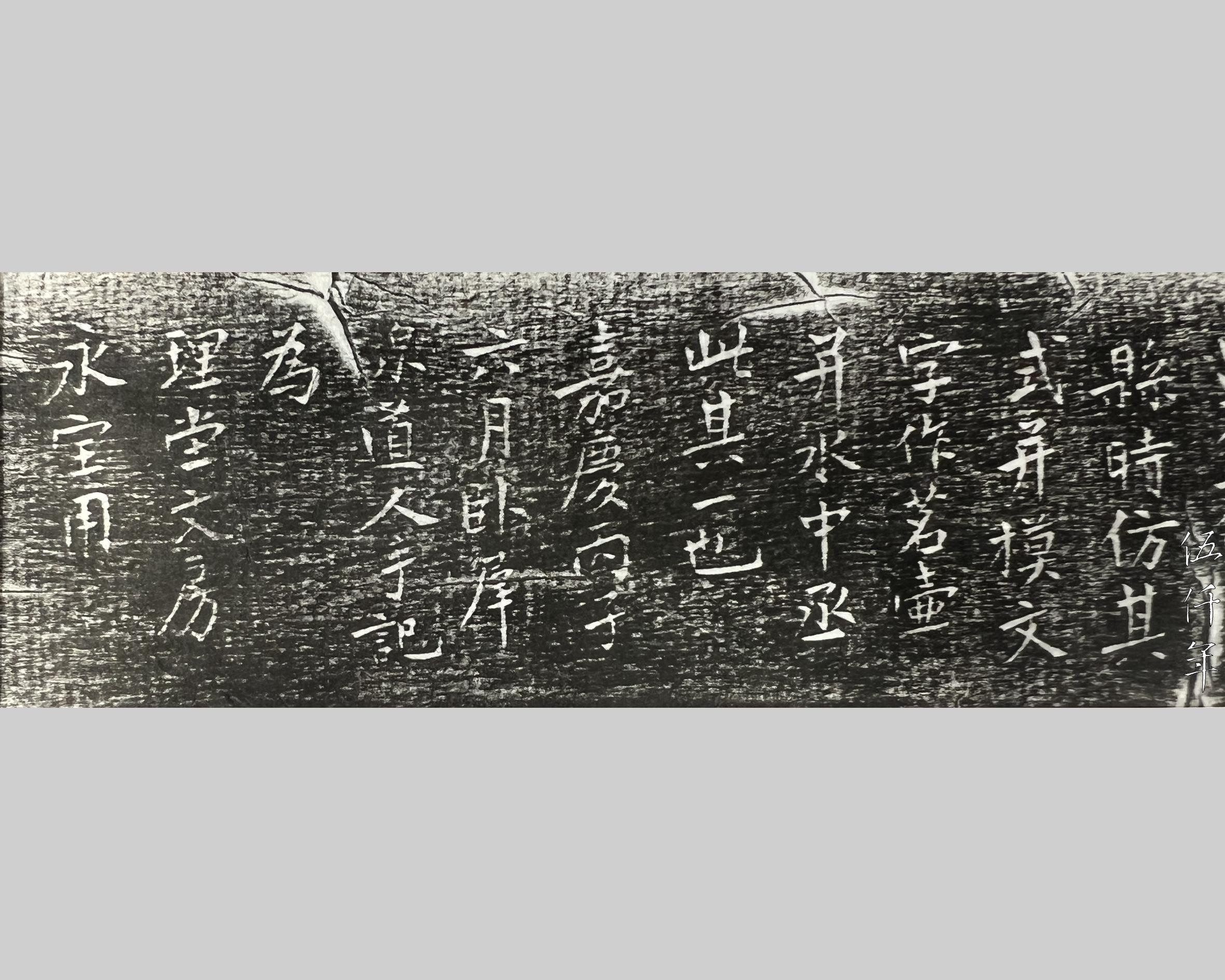

The well is now located within Pao-en Temple outside the East Gate of Li-yang. When dear old Man-sheng became magistrate of this county, he copied its form and words to make teapots and water vessels, this is one such item.

In June of ping-tzu (丙子) year, the 6th year of the Chia-ch’ing reign, Hsi-ch’üan Tao-jen (犀泉道人) recorded this by hand. This is a desk object, an everlasting treasure, made for Li-t’ang (理堂).”

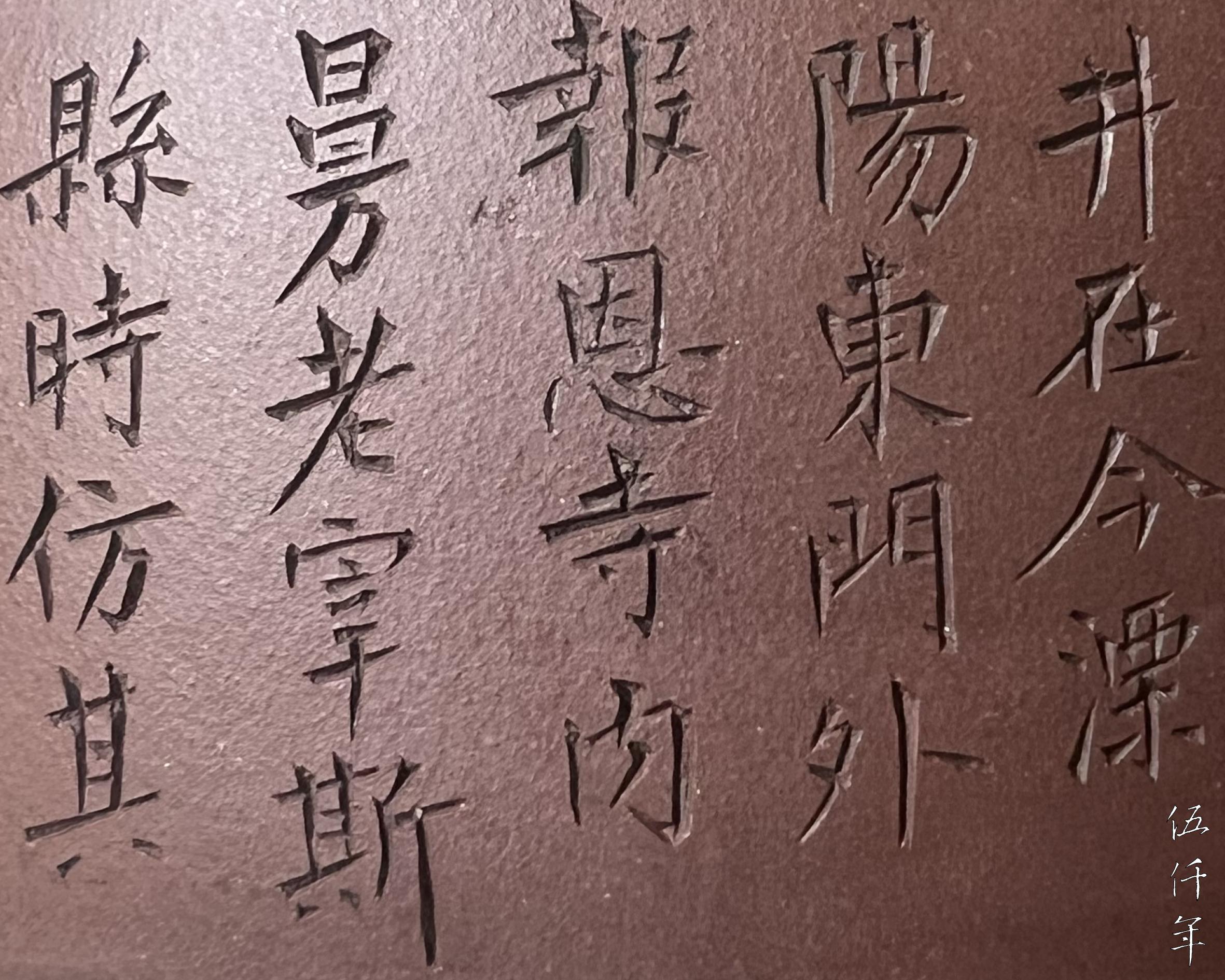

First view of calligraphic engraving on I-hsing clay water vessel resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in the Studio of Prunus Ode Collection

Second view of calligraphic engraving on I-hsing clay water vessel resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in the Studio of Prunus Ode Collection

Third view of calligraphic engraving on I-hsing clay water vessel resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in the Studio of Prunus Ode Collection

First Ink rubbing of calligraphic engraving on I-hsing clay water vessel resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in the Studio of Prunus Ode Collection

Second ink rubbing of calligraphic engraving on I-hsing clay water vessel resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in the Studio of Prunus Ode Collection

Third ink rubbing of calligraphic engraving on I-hsing clay water vessel resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in the Studio of Prunus Ode Collection

Chief Minister for the Palace Buildings was an honorific title bestowed to Kuo T’ung. He was the grandfather of the preeminent Grand Councilor Kuo Tzu-i (郭子儀 697 AD to 781 AD) who revived the fortune of the T’ang dynasty. He was a native of Hua-chou in Shan-hsi province. Kuo T’ung served as assistant magistrate of Mei-yüan County in Shan-hsi province. He was posthumously honoured as minister of war. This poem engraved on the headwall of the well was compiled into the Complete T’ang Poems, Supplement, Volume 22. In the sixth year of the Yüan-ho reign, when Ch’eng-kuan commissioned the construction of the well, Kuo Tzu-i had been dead for exactly thirty years. The carving of the Buddhist verse composed by his grandfather Kuo T’ung on the headwall of the well demonstrated that Kuo Tzu-i’s posthumous fame was still undiminished.

The water vessel was made in ping-tzu year of the Chia-ch’ing reign, which is the 21st year of Chia-ch’ing reign, corresponding to 1816. At the time Chen Man-sheng was the district magistrate of Li-yang.

The engraving on the water vessel was signed by Hsi-ch’üan (犀泉), the tzu of Kao Jih-chun (高日濬), whose studio name was Fu-hsiang Lou (浮香樓). He was the brother of Chen Man-sheng’s wife, and a native of Ch’ien-t’ang in Chekiang province. He was coached by Chen Man-sheng in seal engraving, and achieved clarity, strength and refinement in his works.

The water vessel was a gift dedicated to Li-t’ang (理堂), the tzu of Chu Wei-hsieh (朱為燮). He attained the title of supplementary student and was a native of P’ing-hu in Chekiang province. He was the younger brother of Chu Wei-pi (朱為弼), and the two brothers were cousins of Chen Man-sheng. Chu Wei-hsieh often exchanged poems with Kuo Ling (郭麐), T’u Cho (屠倬), and Chen Man-sheng. He was skilled in the calligraphy style of flying-white (飛白). His literary work is titled Collected Poems of Ch’uan-shih Studio (傳石齋詩集).

Top view of I-hsing clay water vessel resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in the Studio of Prunus Ode Collection

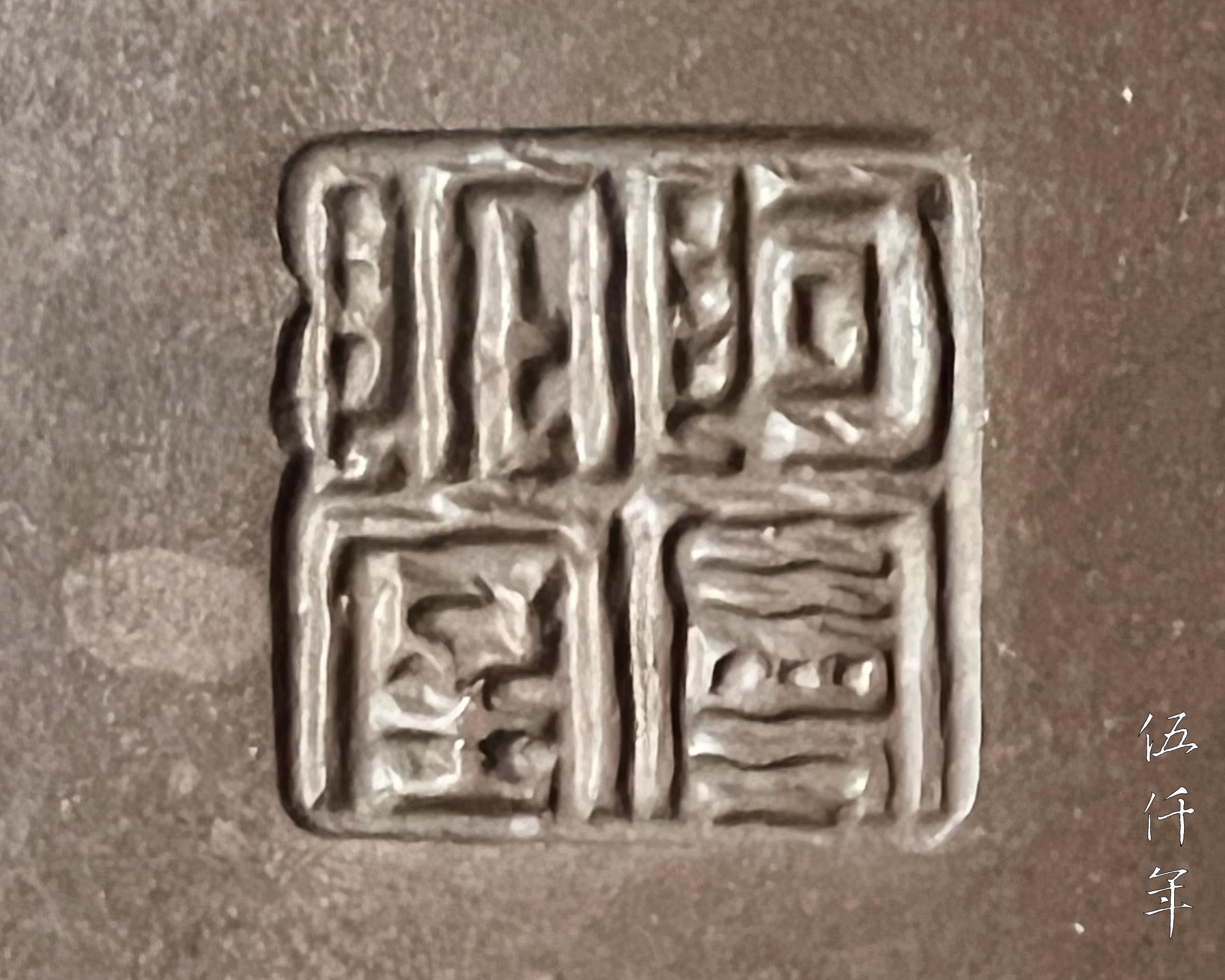

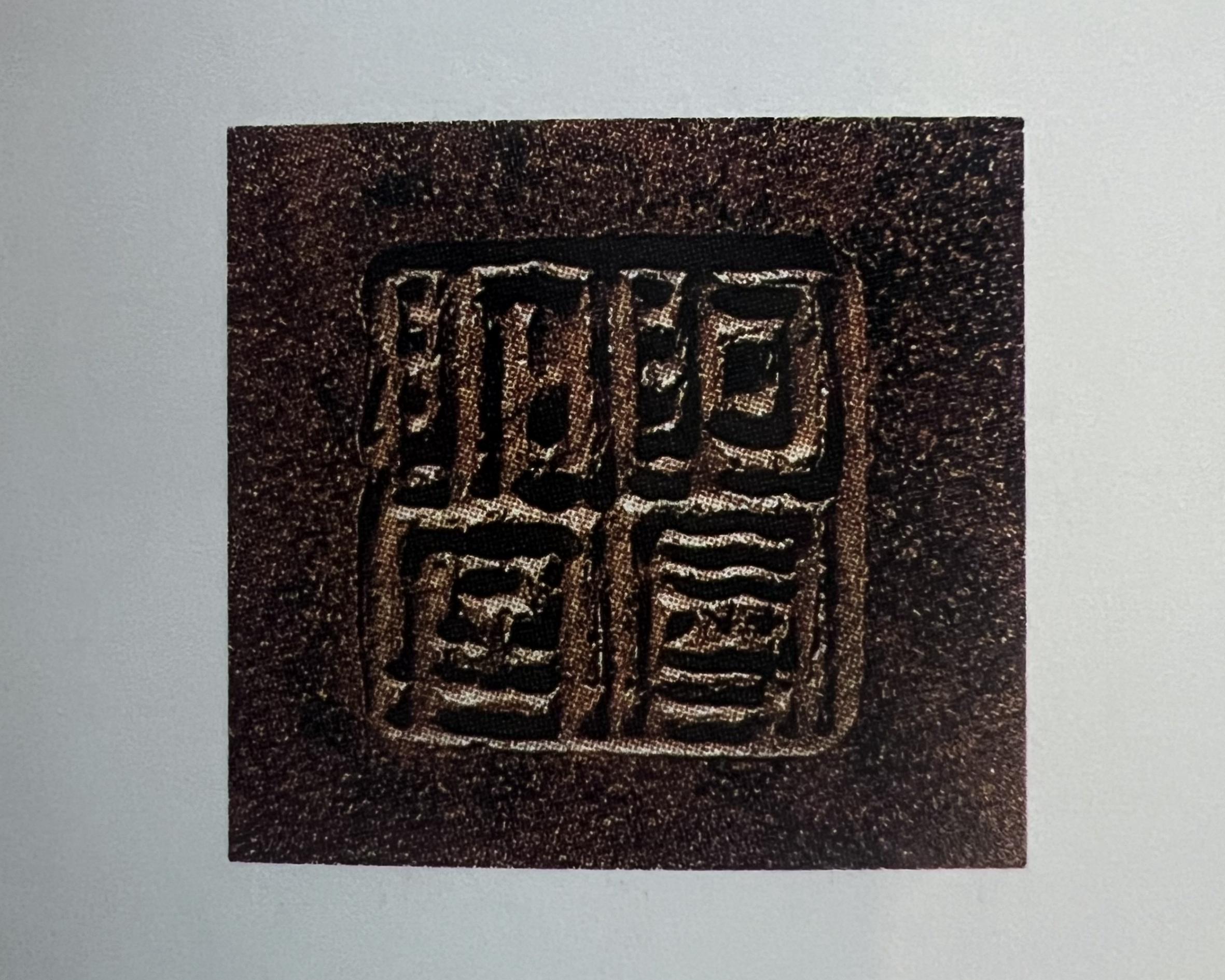

Base of I-hsing clay water vessel resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in the Studio of Prunus Ode Collection, seal of A-man-tuo Shih (阿曼陀室) in center

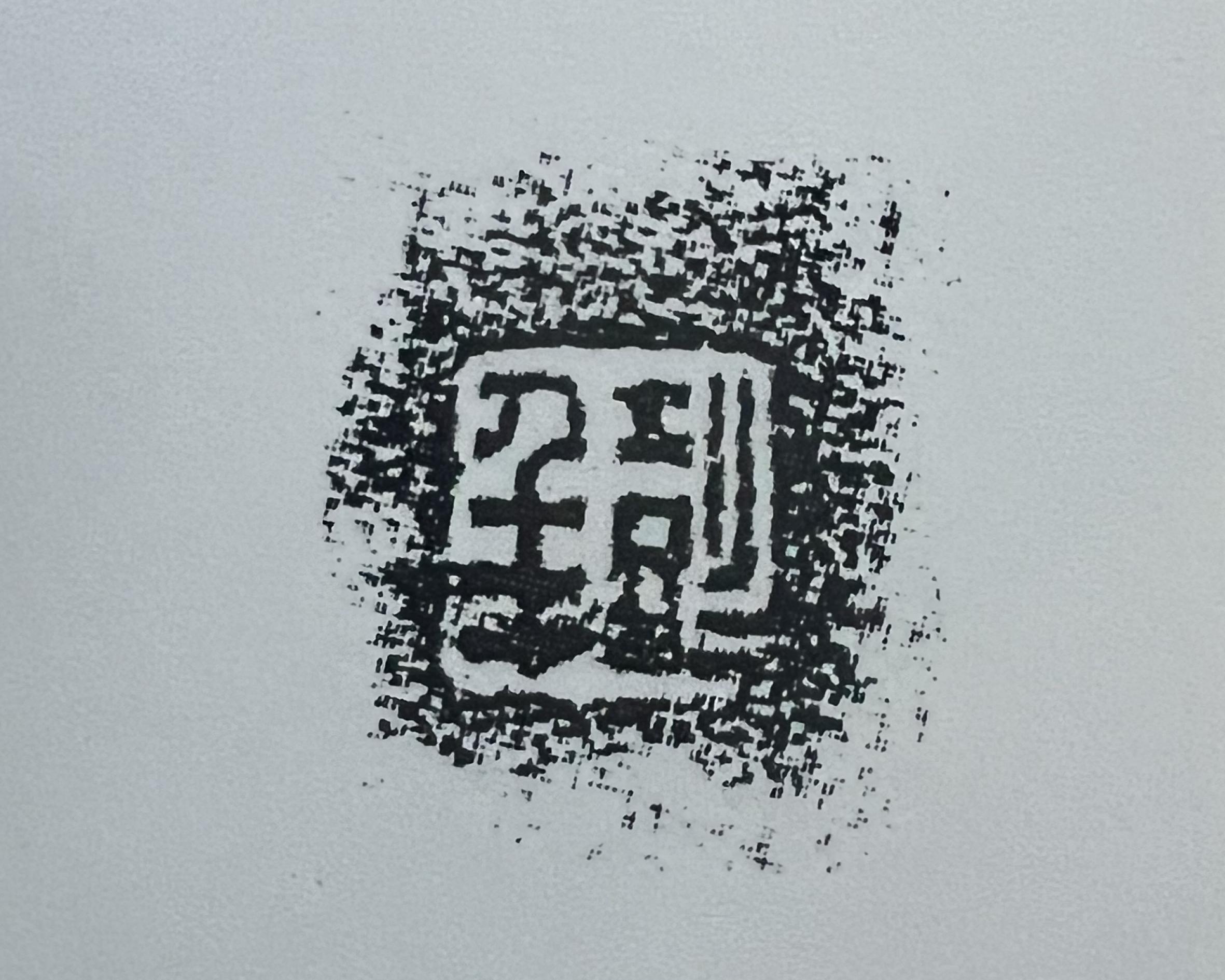

Detail of A-man-tuo Shih (阿曼陀室)seal at the base of the I-hsing clay water vessel resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in the Studio of Prunus Ode Collection

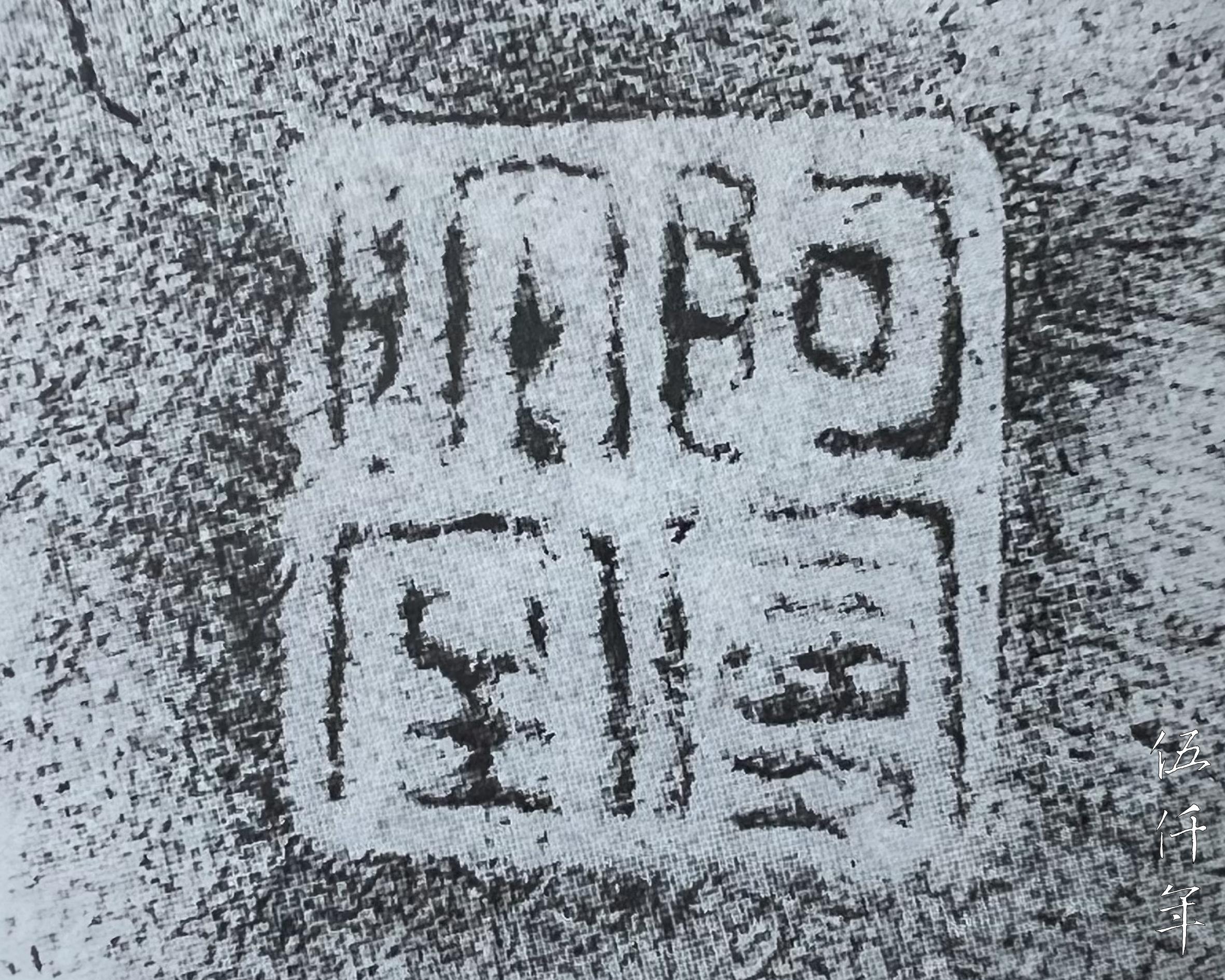

Ink rubbing of A-man-tuo Shih seal at the base of the I-hsing clay water vessel resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in the Studio of Prunus Ode collection

At the base of the water vessel, there is the seal imprint “A-man-t’o Shi (阿曼陀室)”. This is a classic mark that verifies the I-hsing ware of Chen Man-sheng. The water vessel would have been made by Yang P’eng-nien (楊彭年).

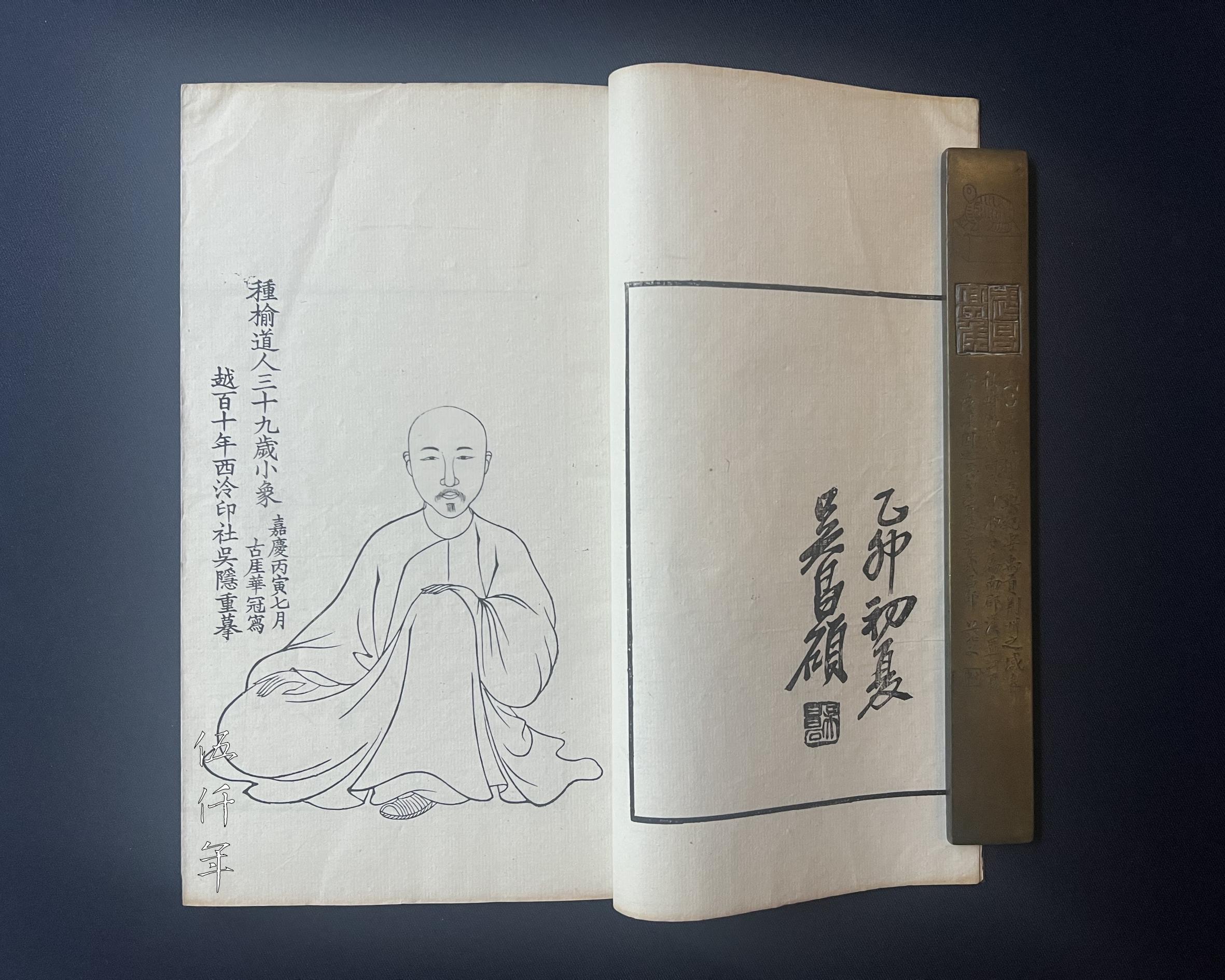

Portrait of Chen Man-sheng

Drawing of Li-yang magistrate’s compound as illustrated in Li-yang County Gazette. Chen Man-sheng’s studio by the name of Sang-lien-li Kuan (桑連理館) is clearly depicted

Closeup view of Chen Man-sheng’s studio Sang-lien-li Kuan

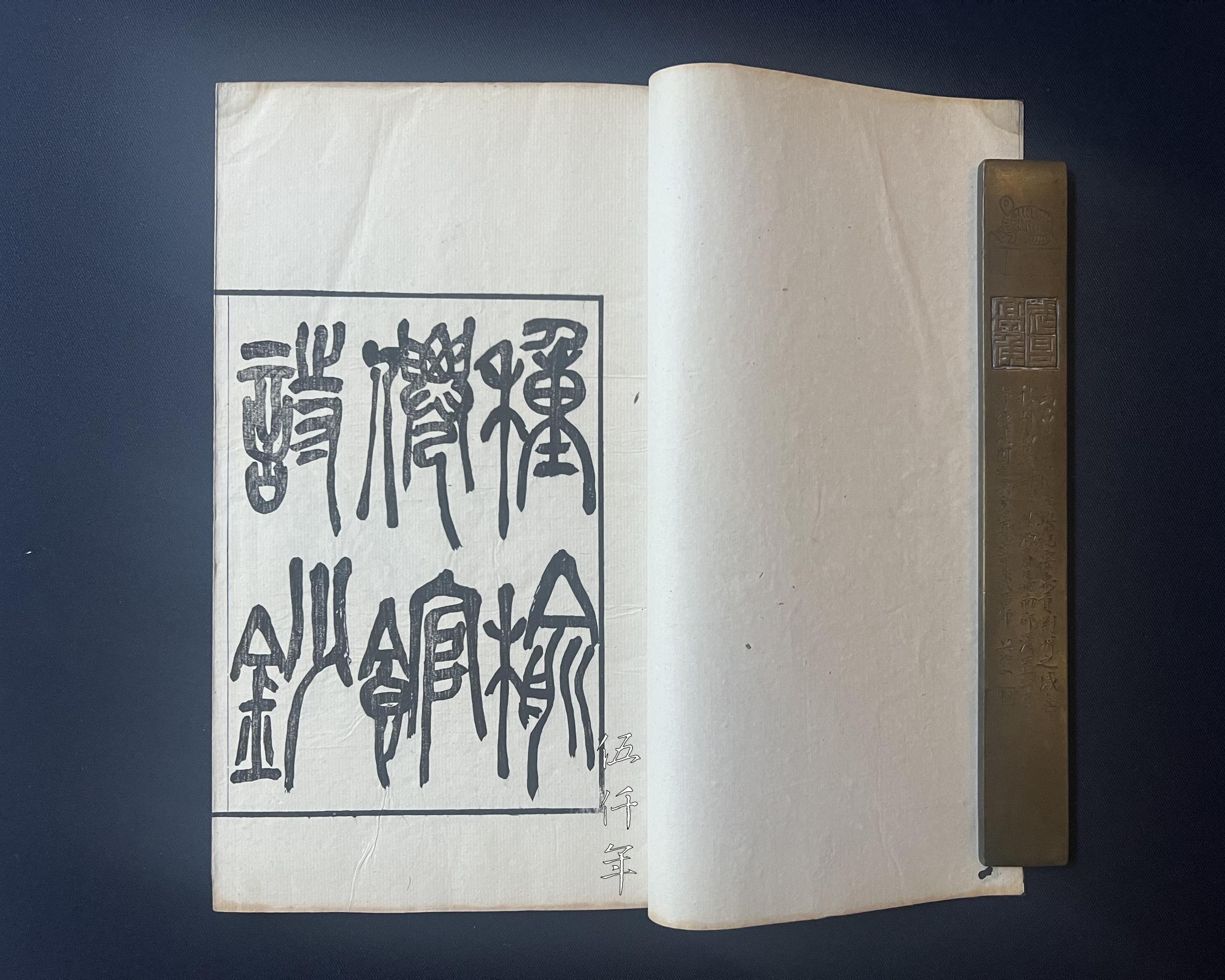

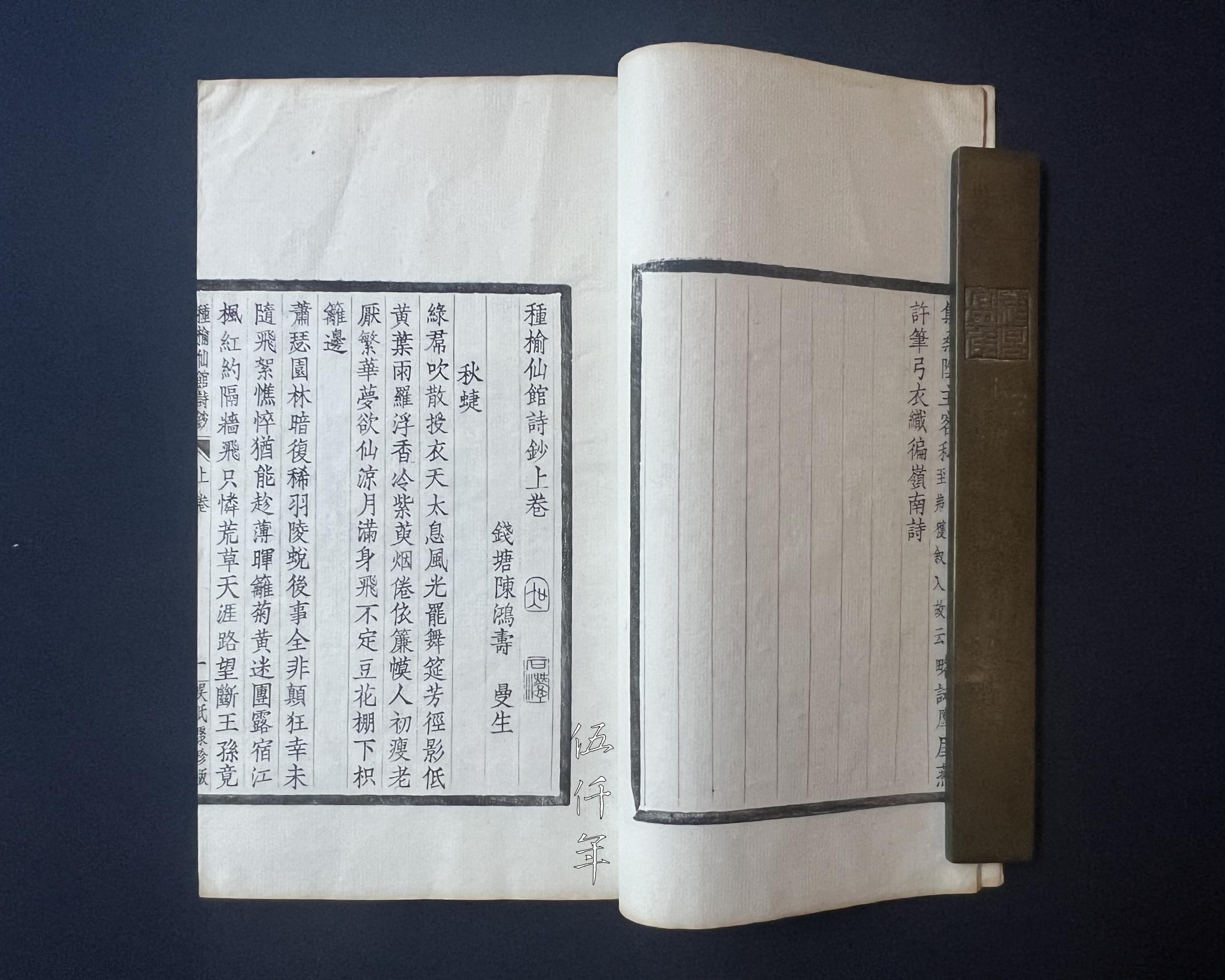

Chen Man-sheng whose original name was Hung-shou (鴻壽), was born in 1768 and died in 1822. His tzu was Tzu-kung (子恭), and his hao were Man-sheng (曼生), Man-shou (曼壽), and Chung-yü Tao-jen (種榆道人). His studio names were A-man-t’o Shi (阿曼陀室), Sang-lien-li Kuan (雙連理館), Chung-yü Hsien-kuan (種榆仙館), and Man-t’o-lo Kuan(曼陀羅館). He was a native of Ch’ien-t’ang in Chekiang province, and served as district magistrate of Li-yang and associate administrator of coastal defense in Chiang-nan. He was proficient in poetry, calligraphy, painting, and especially renowned for seal carving, being one of the Eight Masters of the Hsi-ling School. He was fond of designing I-hsing teapots and known for his “eighteen Man-sheng designs”, though in fact he designed many more. They were crafted with great precision by the master potter Yang P’eng-nien, and they became known as “Man-sheng teapots”. His poetry was titled the Collected Poems of Chung-yü Hsien-kuan (種榆仙館詩鈔).

Title page of Collected Poems of Chung-yü Hsien-kuan by Chen Man-sheng

Portrait of Chen Man-sheng in Collected Poems of Chung-yü Hsien-kuan

Inside page of Collected Poems of Chung-yü Hsien-kuan

Chen Man-sheng, Yang P’eng-nien, and Kao Jih-chun jointly created the water vessel as a gift to Chu Wei-hsieh. The three of them, Chen, Kao and Chu, were not only bonded by close family ties, but also shared a deep friendship through literature and art.

I-hsing clay water vessel by Chu Chien, imitating Chen Man-sheng’s water vessel that resembles T’ang dynasty well, formerly in the Collection of T’ang Yün

Bottom of I-hsing clay water vessel by Chu Chien, imitating Chen Man-sheng’s water vessel that resembles T’ang dynasty well. Seal of “Imitated and made by Shih-mei” in the center, formerly in the Collection of T’ang Yün

The renowned painter T’ang Yün (唐雲) once owned a water vessel modelled on the T’ang well. It was 3.8 cm in height, slightly smaller than the water vessel by Chen Man-sheng, and it had the seal imprint “Imitated and made by Shih-mei (石楳)”. Hence it is certain that the late Ch’ing teapot master Chu Shih-mei (朱石楳), original name Chu Chien (朱堅), had seen and examined Chen Man-sheng’s water vessel modelled on the T’ang well. He must have been overwhelmed with admiration to make his own copy. The Nanjing Museum has a Chen Man-sheng teapot modelled on the T’ang well and a water vessel modelled on the T’ang well made under the name of Yang P’eng-nien himself.

I-hsing clay teapot resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in Nanjing Museum

Base of I-hsing clay teapot resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in Nanjing Museum, seal of A-man-tuo Shi (阿曼陀室) in center

Seal of “P’eng-nien” on handle of I-hsing clay teapot resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in Nanjing Museum

First ink rubbing of I-hsing clay teapot resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in Nanjing Museum

Second ink rubbing of I-hsing clay teapot resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in Nanjing Museum

I-hsing clay water vessel resembling T’ang dynasty well by Yang P’eng-nien in Nanjing Museum

The Shanghai Museum has two Chen Man-sheng teapots modelled on the T’ang well. These examples confirm the inscription engraved by Kao Jih-chun: “When dear old Man-sheng became magistrate of this county, he copied its form and words to make teapots and water vessels, this is one such item.”

Chen Man-sheng produced two types of objects, teapots and water vessels, to resemble the T’ang well, and they were produced in limited numbers. However, after more than two centuries, very few examples have survived. I have not seen another water vessel modelled on the T’ang well made under the name of Chen Man-sheng, this can be considered the only piece extant.

Contemplating these two lines in Kuo T’ung’s verse: “Countless generations, Buddhist karma tied,” Ch’eng-kuan had hoped to use the enduring stone well to attain this timeless enterprise. He could not have imagined that twelve hundred and more years later, though the well still stands in Li-yang, it has become a relic in a public park, and that Buddhism has diminished so much in the country, it is comparable to the devastation under Emperor T’ai-wu of the Wei dynasty, Emperor Wu of the Northern Chou dynasty and Emperor Wu-tsung of the T’ang dynasty. Over two hundred years ago, Chen Man-sheng recreated Ch’eng-kuan’s well in the form of a water vessel in I-hsing clay, and it has fortuitously survived the ravages of time. How extraordinary has been my blessings? To find this pearl in a pile of ashes, in a life as ephemeral as a flickering light. Days and nights, in its company, trekking along the incised lines and shadows left by the carving blade, to be touched and illuminated by the compassionate heart of Buddha.

Detail of calligraphy engraving on I-hsing clay water vessel resembling T’ang dynasty well by Chen Man-sheng in the Studio of Prunus Ode Collection

Related Contents:

Innovator of Classical Sensibility: Chen Man-sheng (陳曼生) and His Waning Moon Pewter Teapot