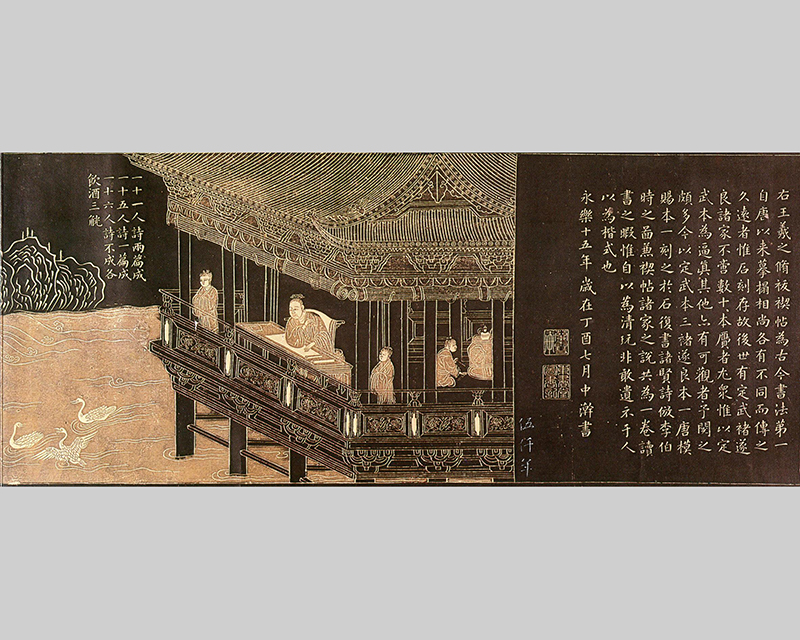

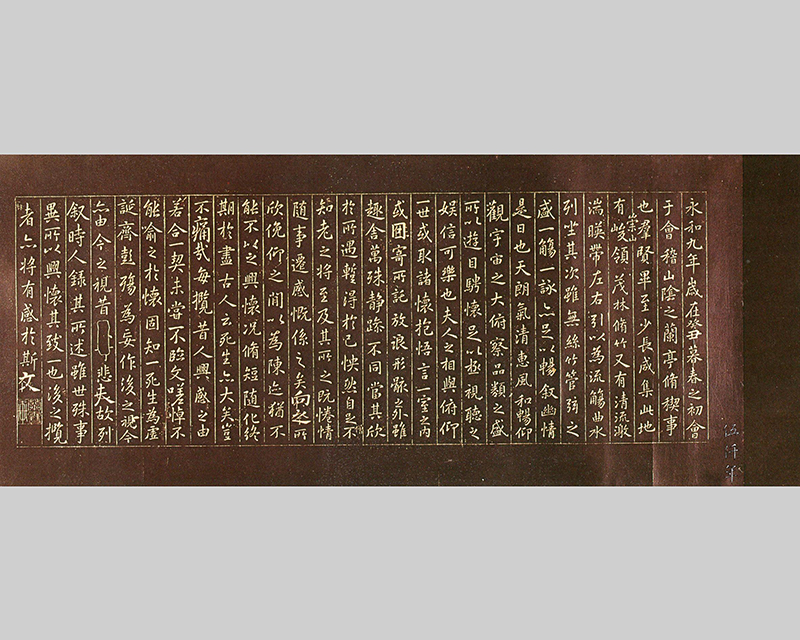

On 3rd March in the 9th year of the Yung-ho reign of the Eastern Chin dynasty (353), kuei-ch’ou year, Wang Hsi-chih (王義之) and his friends gathered at Lan-t’ing in Shan-yin to perform the custom of Hsiu-hsi. The place is now known as Shao-hsing of Chekiang province. The calligraphy of the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Lan-t’ing Gathering by Wang Hsi-chih is revered by calligraphers throughout history as the benchmark of calligraphy, generations ever since have been in awe.

One thousand five hundred and sixty years afterwards, it was the second year of the founding of the Republic of China (1913). Everything under the sun was anew, all kinds of matters afresh. Liang Ch’i-chao emulated the refinement of the ancients, he invited over forty like-minded friends to a Hsiu-hsi gathering in the Garden of Myriad Lives in Peking, and each was given a group photograph later on. After a hundred years of vicissitudes, this photograph now presented is likely to be the sole surviving copy.

Liang Ch’i-chao is a model of an intellectual trying to save the country from calamity. In wu-hsü year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1898), he was a planner of the Hundred Days’ Reform. After it was crushed, he fled to Japan. He tried to help the country through his writings, and they were celebrated all over. After the founding of the Republic of China in 1912, he was appointed finance minister in 1916. When Yüan Shih-Kai sought to become emperor in 1916, he plotted his overthrow. During the Paris Peace Conference (1919), he was in France as external observer, reporting back to China the progress of the negotiations, and facilitating the rejection of the Treaty. Intellectuals in the past, could yet secure access to save the country. Intellectuals today, even though they feel compelled to save the country, contrarily, cannot even spot such access.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

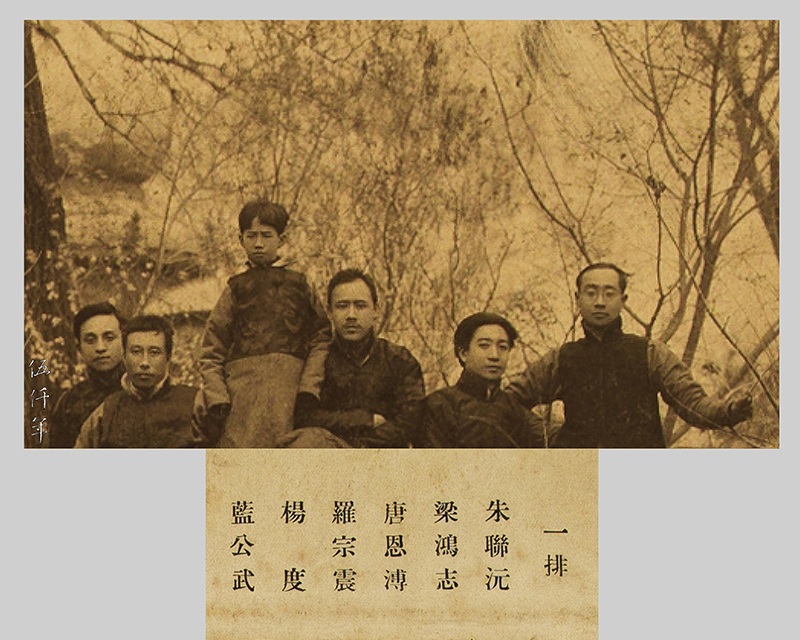

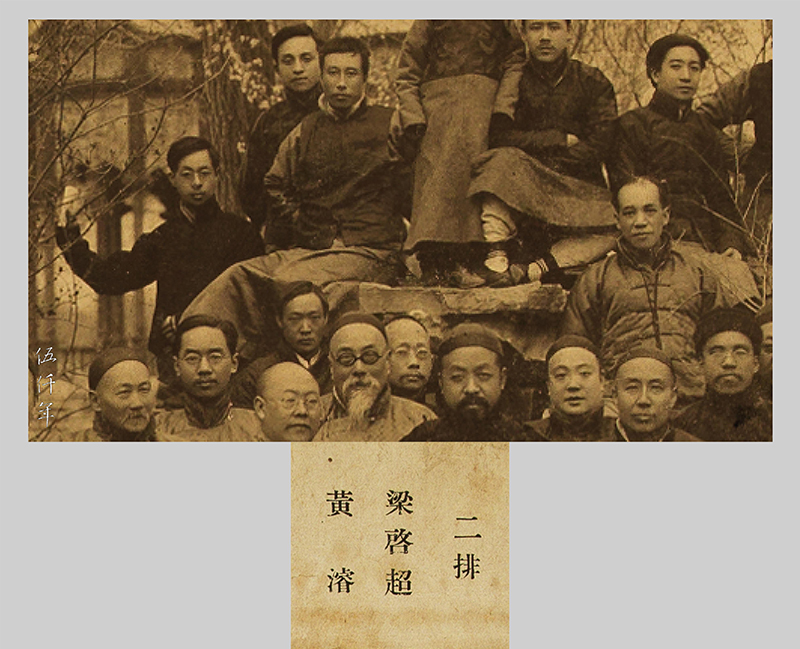

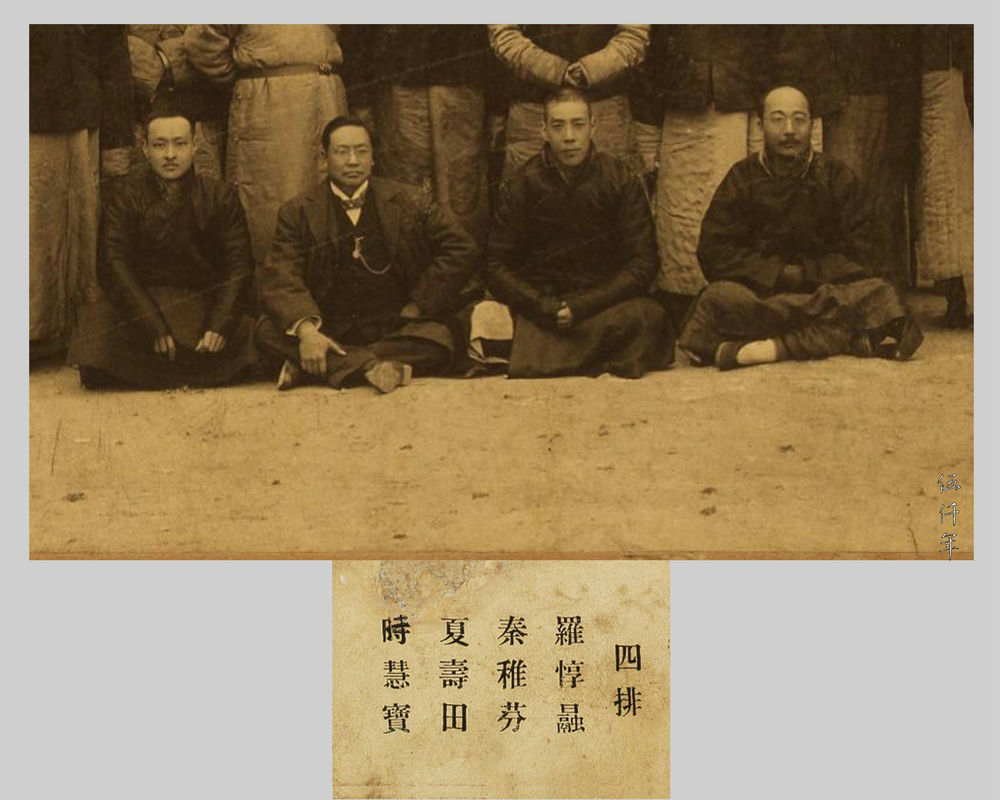

Group portrait of Hsiu-hsi gathering in the Garden of Myriad Lives. Studio of Delicate Fragrance Collection

The date 3rd of March (Chinese Agricultural Calender) in the 2nd year of the Republic (1913), kuei-ch’ou (癸丑) year, was exactly the 26th kuei-ch’ou year of the sexagenary cycle, or one thousand five hundred and sixty years, after the legendary literary gathering organized by Wang Hsi-chih (王羲之 303-361) to enact the custom of Hsiu-hsi (脩禊) in Lan-t’ing (蘭亭), which took place on the 3rd of March kuei-ch’ou year, in the 9th year of the Yung-ho reign of the Eastern Chin dynasty (353). To commemorate this historical anniversary, on 3rd March 1913, Liang Ch’i-ch’ao (梁啟超) invited over forty eminent literary friends to celebrate the custom of Hsiu-hsi in the Garden of Myriad Lives (Garden of Wan-sheng 萬生園) in Peking. They recited poetry in gaiety and leisure, recollected the past and reflected on the present, and indeed contrived a most refined occasion at the time. The Anthology of Hsiu-hsi in Kuei-ch’ou Year was published by Liang in a limited number for distribution to friends and relatives. This book is now rare to come by.

Portrait of Liang Ch’i-chao

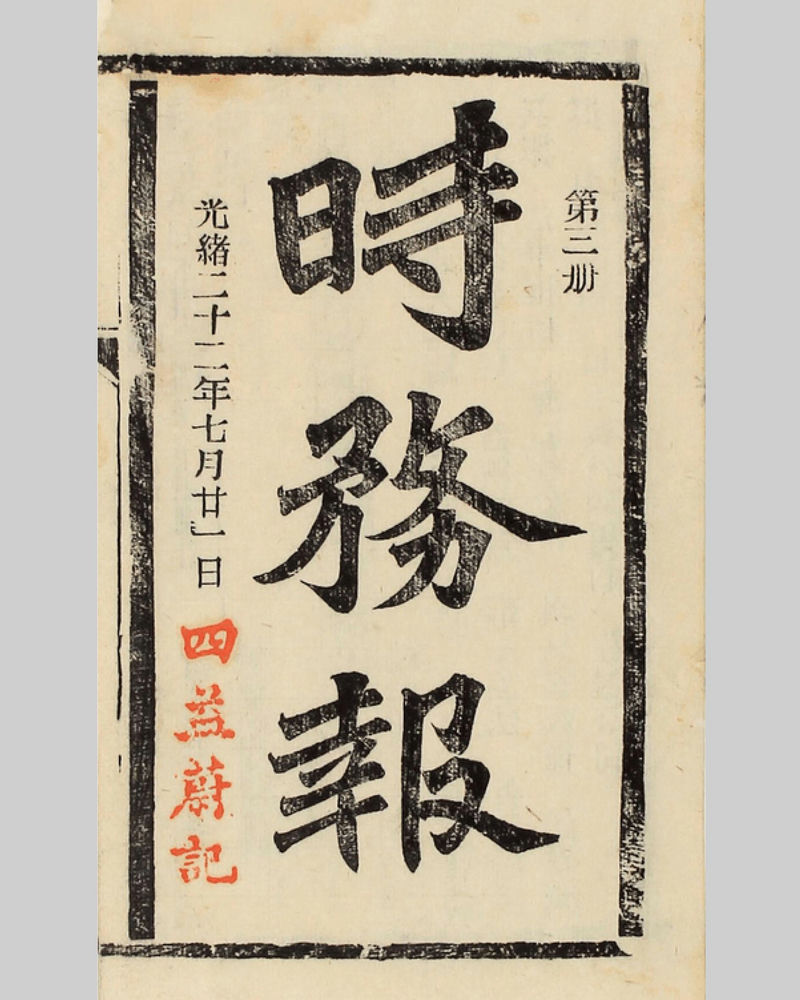

Liang Ch’i-chao (1873-1929), tzu Cho-ju (卓如), Jen-fu (任甫), hao Jen-kung (任公), Yin-ping-tzu (飲冰子), Yin-ping Shih Chu-jen (飲冰室主人), native of Hsin-hui (新會), Kwangtung province. He attained the chü-jen degree in the 15th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1889). In the 21st year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1895), K’ang Yu-wei (康有為 1858-1927) led Liang to instigate the Kung-ch’e Shang-shu (公車上書) petition to the Emperor requesting political reform, signed by over 1200 chü-jen who arrived in the capital from all parts of the country, to take part in the state examination for the chin-shih degree. Liang became editor-in-chief of Ch’iang-hsüeh Pao Newspaper (強學報) , and founded Shih-wu Pao Newspaper (事務報) with Huang Tsun-hsien (黃遵憲 1848-1905) and Wang K’ang-nien (汪康年 1860-1911). In the 23rd year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1897), he was appointed head of Chinese department at Shih-wu Hsueh-t’ang (時務學堂) in Changsha, Hunan province.

Liang Ch’i-chao founded Shih-wu Pao Newspaper (事務報)

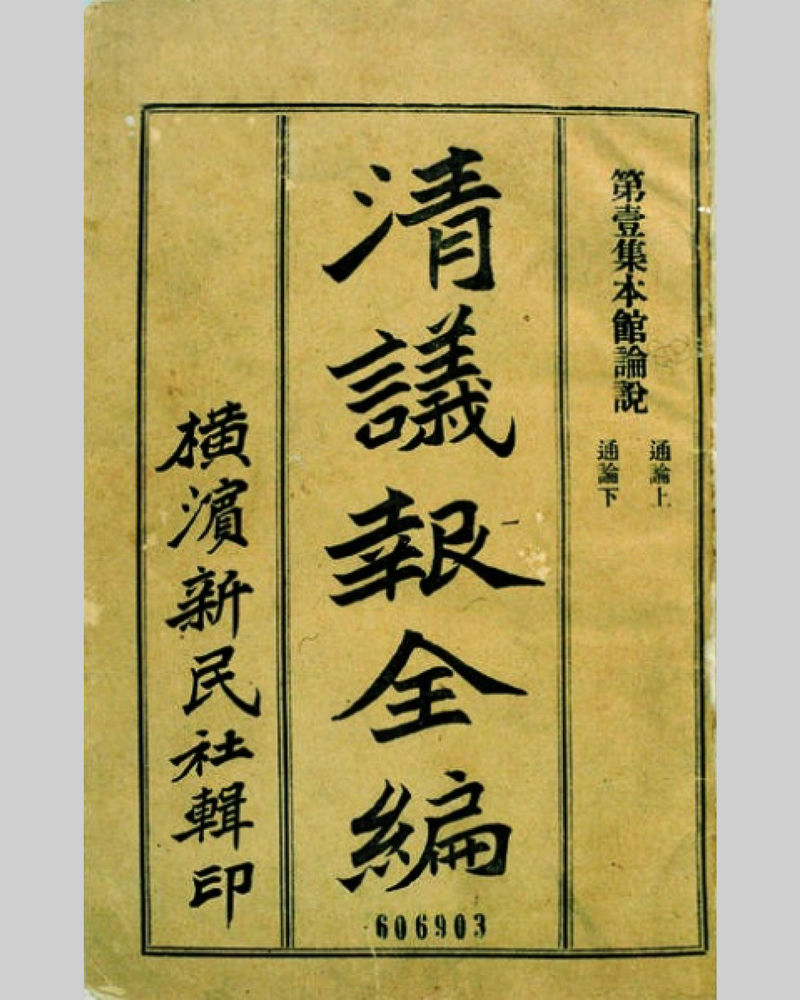

In the 24th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1898), during the Hundred Days’ Reform, Kuang-hsü emperor bestowed him the official rank of sixth pin, and made him in charge of the Translation Bureau. After the Empress Dowager Tz’u-Hsi engineered a coup d’etat and ordered the execution of his comrades known as the Six Gentlemen of Wu-hsü, Liang fled to Japan, and founded Ch’ing-i Pao Newspaper (清議報). He made an investigatory trip to Australia, and founded Hsin-min Ts’ung-pao Newspaper (新民叢報). He made further investigatory trips to the United States and Taiwan.

Liang Ch’i-chao founded Ch’ing-i Pao Newspaper (清議報)

Liang Ch’i-chao founded Hsin-min Ts’ung-pao Newspaper (新民叢報)

In the first year of the Republic of China (1912), he returned to China, and founded Yung-yen Magazine (庸言). He was successively appointed attorney general, and president of the Board of Commissioners of Currency. In the 4th year of the Republic (1915), he opposed Yüan Shih-k’ai’s bid to be emperor. In the 5th year of the Republic (1916), he founded Ch’en-chung Pao Newspaper (晨鐘報) with Lin Ch’ang-min (林長民 1876-1925), and was appointed finance minister. In the 8th year of the Republic (1919), he visited Europe and attended the Paris Peace Conference as external observer. In the 14th year of the Republic (1925), he was professor of Chinese Studies at Tsing Hua University, and president of Peking Library (Ching-shih Library). His works include Travelogue of the New Continent (Hsin ta-lu yu-chi), An Intimate Record of European Travel (Ou-yu hsin-ying lu), Outline of Ch’ing Scholarship (Ch’ing-tai hsüeh-shu kai-lun), History of Chinese Scholarship in the Last Three Hundred Years (Chung-kuo chin san-pai nien hsüeh-shu shih), etc. His writings were compiled into The Complete Works of Yin-ping Shih (Yin-ping Shih Ho-chi).

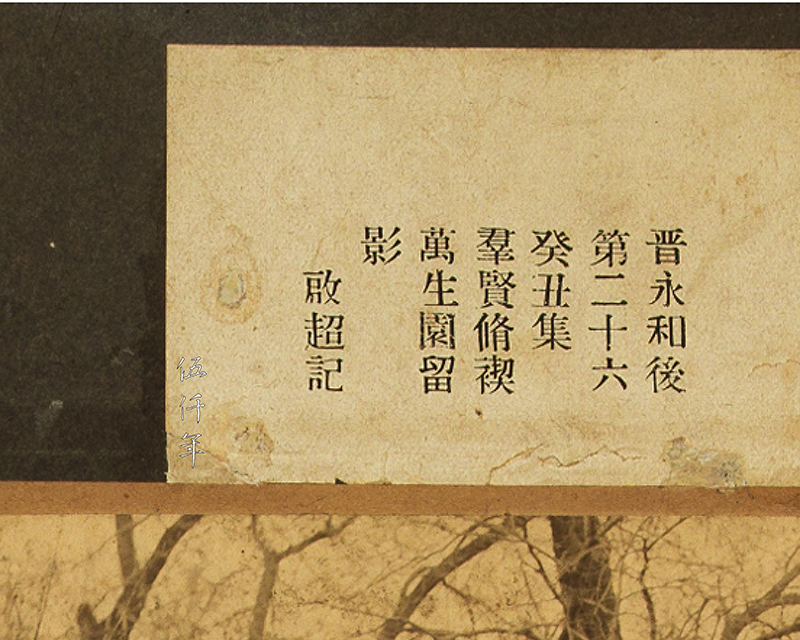

On the day of 3rd March 1913, during the Hsiu-hsi gathering in the Garden of Myriad Lives, a group portrait was taken, and each participant was given a copy for remembrance. On the upper left of the cardboard frame, some words by Liang were printed: “In the 26th kuei-ch’ou year after the Yung-ho reign of the Chin dynasty, a group of exemplary men attended the commemoration of Hsiu-hsi in the Garden of Myriad Lives. Ch’i-chao thus recorded.” This treasured photograph in the Studio of Delicate Fragrance was in the former collection of Mr. T’ang T’ien-ju (En-p’u). He attended the Hsiu-hsi gathering in the Garden of Myriad Lives and his family kept it for over a century in Hong Kong. Hence it was fortunate enough not to be ravaged by the turmoils in mainland China, and certainly as rare as a unicorn from the depth of time. Beside the group portrait, the names of the participants were printed.

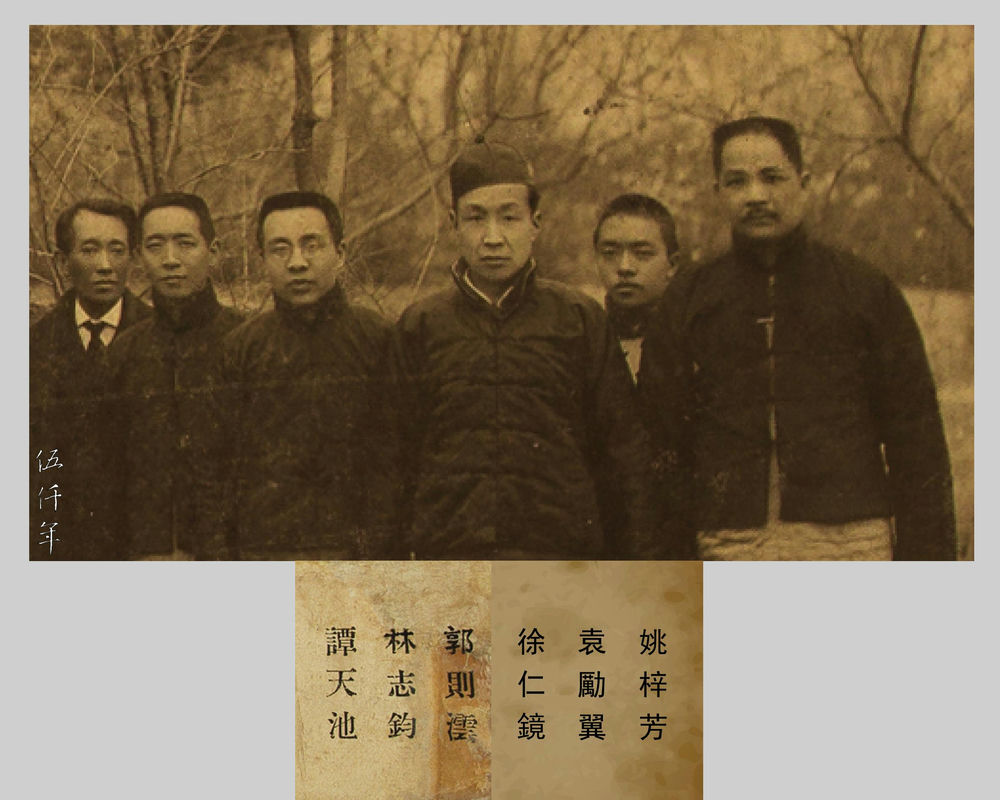

Detail 1 of group portrait, six invitees are in the first row

There are six in the first row, they are: Chu Lien-yüan (朱聯沅), Liang Hung-chih (梁鴻志), T’ang En-p’u (唐恩溥), Lo Tsung-chen (羅宗震), Yang Tu (楊度) and Lan Kung-wu (藍公武).

Detail 2 of group portrait, two invitees are in the second row. On the right is Liang Ch'i-chao

There are two in the second row, they are: Liang Ch’i-chao (梁啟超) and Huang Chün (黃濬).

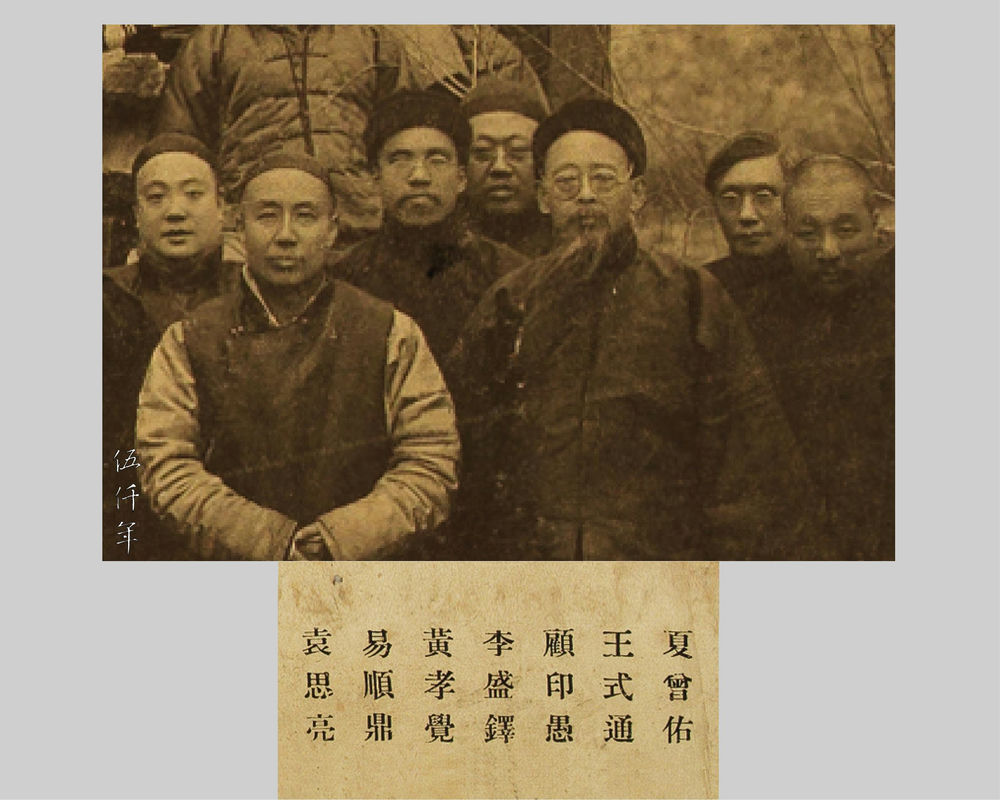

Detail 3 of group portrait, twenty four invitees are in the third row. Here are six of them

Detail 4 of group portrait, twenty four invitees are in the third row. Here are seven of them, second from left is I Shun-ting

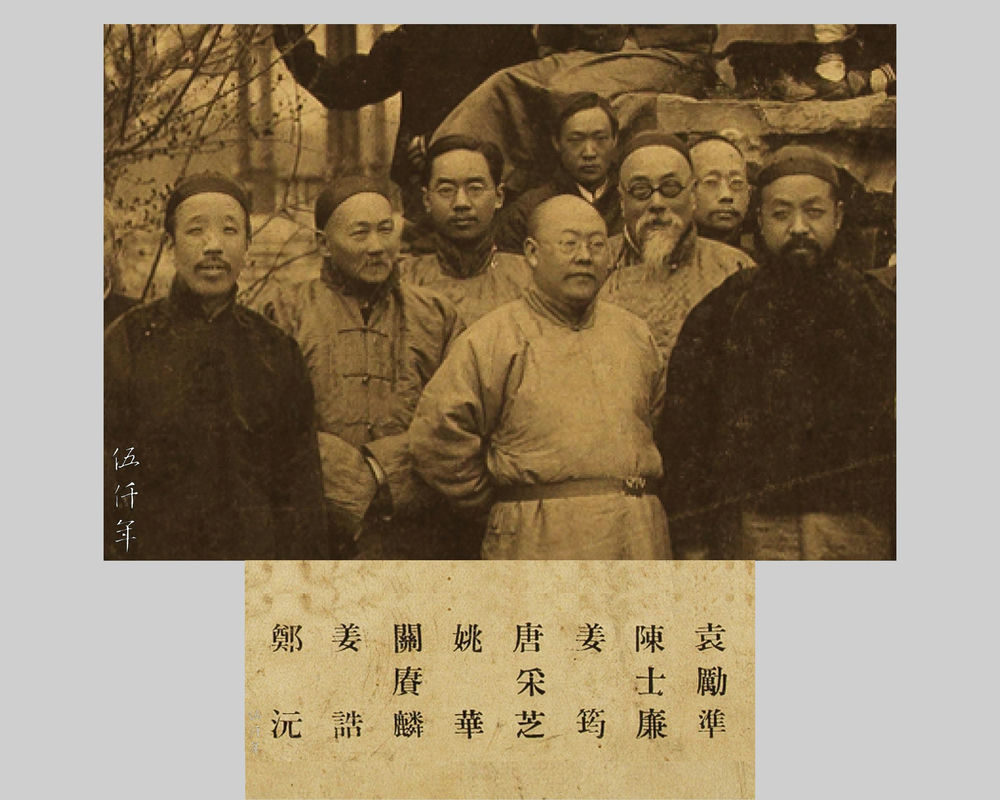

Detail 5 of group portrait, twenty four invitees are in the third row. Here are eight of them

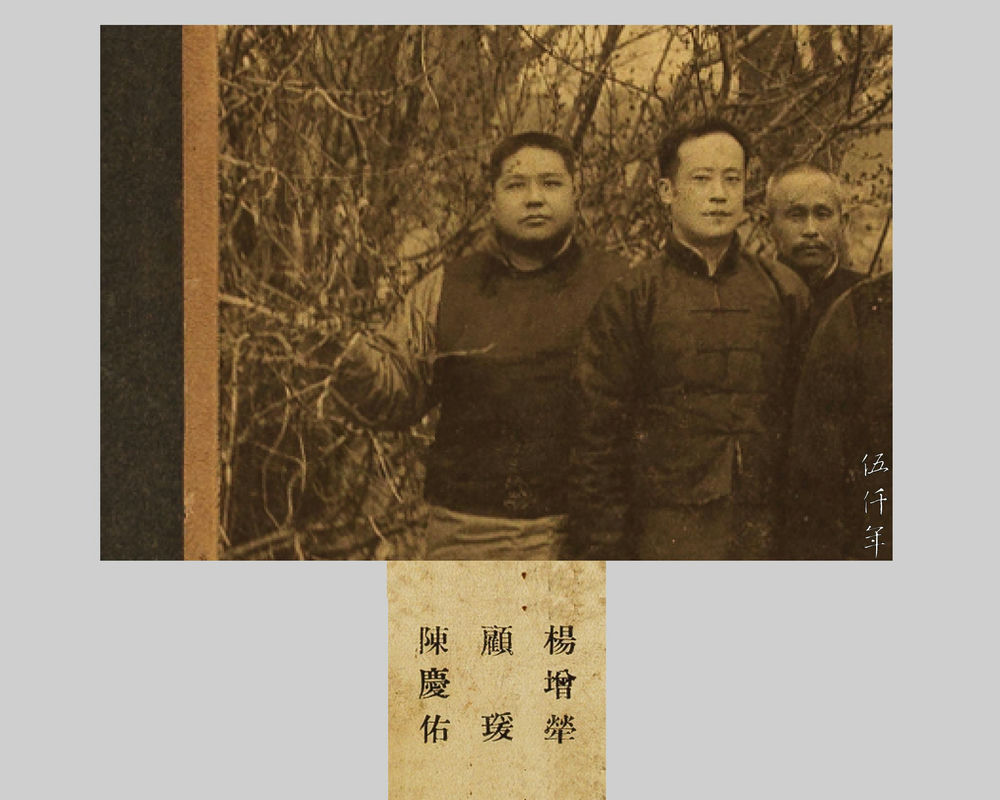

Detail 6 of group portrait, twenty four invitees are in the third row. Here are three of them

There are twenty four in the third row, they are: Yao Tzu-fang (姚梓芳), Yüan Li-I (袁勵翼), Hsü Jen-ching (徐仁鏡), Kuo Tse-yün (郭則澐), Lin Chih-chün (林志鈞), T’an T’ien-ch’ih (譚天池), Hsia Tseng-yu (夏曾佑), Wang Shih-t’ung (王式通), Ku Yin-yü (顧印愚), Li Sheng-to (李盛鐸), Huang Hsiao-chüeh (黃孝覺), I Shun-ting (易順鼎), Yüan Ssu-liang (袁思亮), Yüan Li-chun (袁勵準), Ch’en Shih-lien (陳士廉), Chiang Yün (姜筠), T’ang Ts’ai-chih (唐采芝), Yao Hua (姚華), Kuan Keng-lin (關賡麟), Chiang Kao (姜誥), Cheng Yüan (鄭沅), Yang Tseng-lo (楊增犖), Ku Yüan (顧瑗) and Ch’en Ch’ing-yu (陳慶佑).

Detail 7 of group portrait, four invitees are in the fourth row

There are four in the fourth row, they are: Lo Tun-jung( 羅惇曧), Ch’in Chih-fen (秦稚芬), Hsia Shou-t’ien (夏壽田) and Shih Hui-pao (時慧寶).

Thirty six literary friends were in the group portrait of the Hsiu-hsi gathering in the Garden of Myriad Lives. Another two, Jan Meng-jen (饒孟仁) and Ch’en Mao-ting (陳懋鼎), attended the gathering but were not accounted in the photograph for some reason. Yen Fu (嚴復), Ch’en Pao-ch’en (陳寶琛), Ch’en Yen (陳衍) and Chou Hung-yeh (周宏業) were invited but could not attend, but they all submitted response poems later on. In the Hsiu-hsi gathering at Lan-t’ing in the Chin dynasty, there were forty two attendants, Liang Ch’i-chao in admiration of the Lan-t’ing legacy, possibly likewise invited forty one friends, making up a total of forty two attendants.

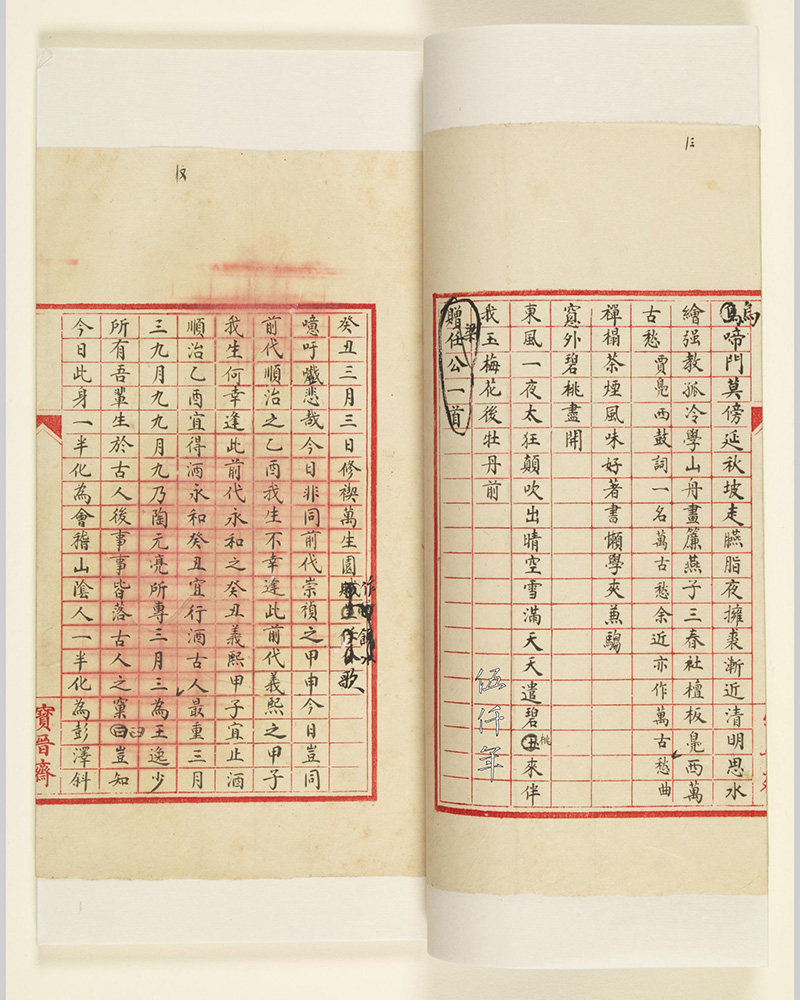

Manuscript of A Lyric to Commemorate Hsiu-hsi on 3rd March Kuei-ch'ou Year in the Garden of Myriad Lives by I Shun-ting. Studio of Delicate Fragrance Collection

In the Studio of Delicate Fragrance, there is an incomplete lyric manuscript by I Shun-ting (易順鼎) titled A Lyric to Commemorate Hsiu-hsi on 3rd March Kuei-ch’ou Year in the Garden of Myriad Lives. He composed this poem after the commemoration and it was compiled into his poetry anthology Ch’in-chih Lou shih-chi (琴志樓詩集). A few selected lines read:

“Master Liang,

Why call on me to be here?

Words in millions are in your books,

More than that of Hsi Tsao-ch’ih (習鑿齒?-383)!

Sixteen years of exile in another land,

Near akin to Chin Chung-erh (晉重耳 697-628 BC)!

Learning of yours so aplenty

Thirteen Classics can be swayed,

Twenty Four Histories can be prised.

This talent is way above and beyond-

A span of five thousand years,

A criss-cross of ninety thousand miles!”

Liang Ch’i-chao was already renowned across the whole country by the 21st year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1895), this lyric by I Shun-ting further affirmed his illustrious reputation in literati circle.

Detail 1 of ink rubbing of calligraphy by Wang Hsi-chih engraved on stone in the 15th year of the Yung-le reign, Ming dynasty

Detail 2 of ink rubbing of calligraphy by Wang Hsi-chih engraved on stone in the 15th year of the Yung-le reign, Ming dynasty

Hsiu-hsi is an ancient custom, every March according to the Chinese Agricultural Calender, it is advisable to bathe by the bank to cleanse ominous omens. Wang Hsi-chih wrote in the Lan-t’ing Preface: “In the beginning of late Spring, we gathered at Lan-t’ing in Shan-yin (山陰), Hui-chi (會稽), to perform the custom of Hsiu-hsi.” We can apprehend that the custom of Hsiu-hsi has been handed down from immemorial.

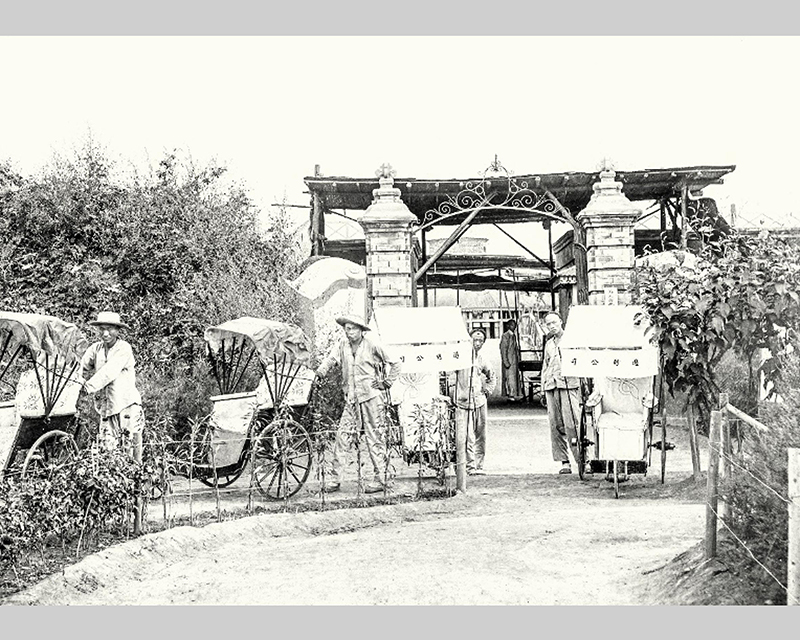

Entrance of the Garden of Myriad Lives

The Garden of Myriad Lives in Peking was known as The Garden of San-pei-tzu (三貝子) in early Ch’ing. It was rebuilt in ting-wei (丁未) year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1907), to become the first zoo in China, also named The Garden of Myriad Animals. In the 17th year of the Republic (1928), this name was changed to Agricultural Experiment Place of the Agriculture, Industry and Commerce Department. In the book Ch’ing-pai lei-ch’ao (清稗類鈔) by Hsü Chung-k’ei (徐仲可), published in the 6th year of the Republic (1917), there is a detailed description of the Garden of Myriad Lives:

“On both sides of the road are willows and elms, in the far distance are scenic hills. Dresses flutter like shadows, horse whips for carriages appear like thin threads, as if in the vista of a painting. Low walls were built around the boundaries of the four sides of the Garden, the perimeter runs into scores of miles. There are scores of acres of flower beds and scores of acres of paddy fields. Pavilions, terraces, towers and airy halls, rivulets, streams, woods and rock formations, they also occupy innumerable acres.”

Inside the Garden, there were lions, bears, leopards, wolves, zebras, sika deers, buffaloes, goats, elephants, many species of birds, and many species of plants. The Garden of Myriad Lives was a preserved site of the last dynasty, it was meant to be a microcosm of the universe, containing everything such as animals, birds, humans, plants, rivers and hills, towers and halls. The mournful sentiment to the passing of time, the solicitude for sentient beings, are ample to arouse poetic inspirations, the Garden was indeed an ideal place for a Hsiu-hsi gathering.

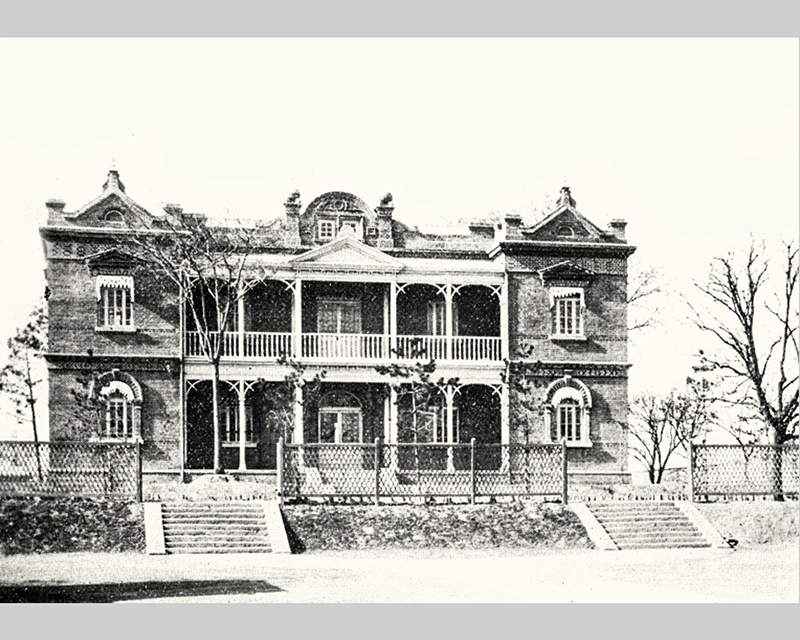

Fountain in the Garden of Myriad Lives

Rickshaws in the Garden of Myriad Lives

Laboratory building in the Garden of Myriad Lives

Bridge in the Garden of Myriad Lives

In The Extended Chronology of the Life of Mr. Liang Jen-kung (Ch’i-Chao), compiled by Ting Wen-chiang (丁文江) (1887-1936), a letter written by Liang to his eldest daughter Ling-hsien (令嫻) was recorded, dated 12th April in the 2nd year of the Republic (1913). It reads:

“I am mailing you a copy of my poem for the commemoration of Hsiu-hsi. After the declaration of the Republic, it is my first attempt to write a poem. On the day of the gathering, many composed poems, mine is intended to be the last in the volume. I have nearly invited all the eminent literati from the southern and central parts of the country to compose poems, it is the finest story since the Lan-t’ing gathering. Sixty years from now, people in this world will no longer know that there are once these two words: kuei-ch’ou. Hence the lines in the final part of my poem that identify with Lan-t’ing, are laden with lamentations.”

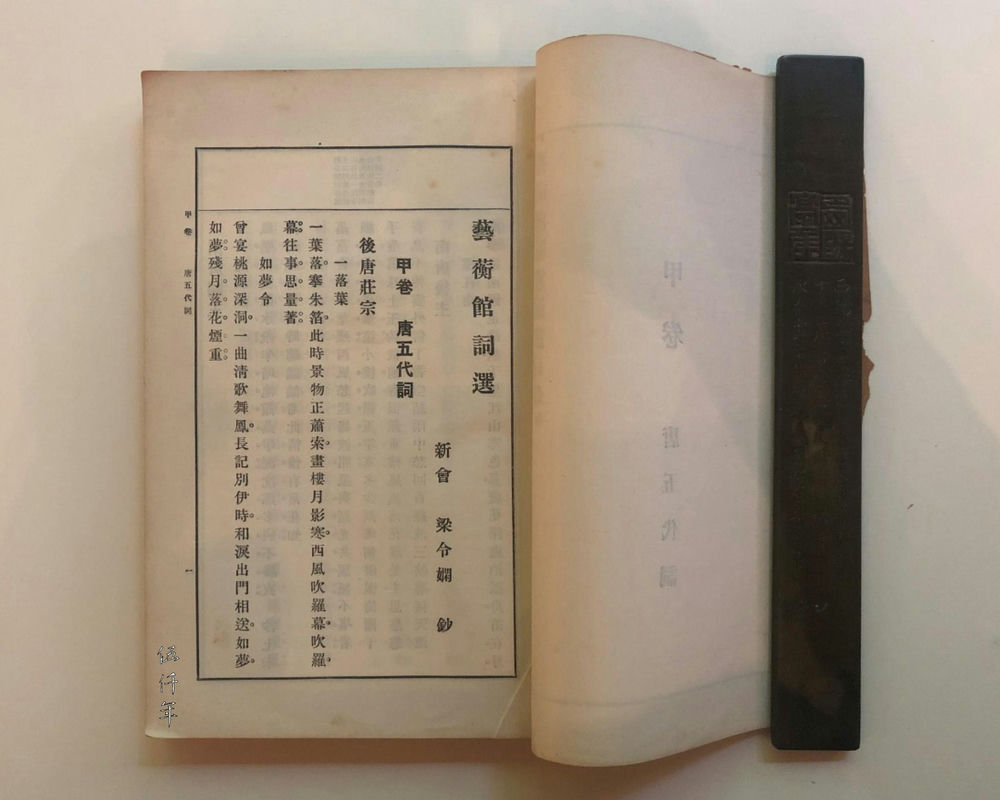

I-heng Kuan tz'u-hsüan by Liang Ling-hsien. Studio of Delicate Fragrance Collection

This poem is recorded in The Complete Works of Yin-ping Shih. It inherited the bygone refinement of Lan-t’ing, and poignant sentiments for his own time were particularly earnest.

After the fall of the Ch’ing dynasty and the founding of the Republic, Liang Ch’i-chao returned to Tientsin from Japan in November in the 1st year of the Republic (1912). Since the debacle of the Hundred Days’ Reform, he had left China for fifteen years, now the world was greatly altered, people and affairs were different, only his lofty ambition was left undiminished. In late December in the same year, he founded the magazine Yung-yen in Tientsin. In February in the 2nd year of the Republic (1913), he joined the Democracy Party, he was aged forty one, aspiring to great accomplishments. Among the eminent personages who attended the Hsiu-hsi gathering in the Garden of Myriad Lives, there were no shortages of political allies nor literary companions of Liang Ch’i-chao, these two identities also frequently overlapped. Apart from a few loyalists of the Ch’ing dynasty, most of them joined the Republican government, they followed the Confucian tradition of past dynasties: to attain official position through distinguished learning, to prioritize the redemption of the world through ability and brilliance, and the least pertinent is to offer writings for posterity. This was the reason the political world of the early Republican era was filled with men of abilities. Observing the system of officialdom today, contrary to the past, it is difficult to captivate men of integrity and learning, since these are not the criteria of political appointnents, villains and rogues filled the government, controlling power and interests, and the fate of the country sinks into oblivion. Today’s world pale to the past, what is to be said? Idle talk of recollection, only my disconsolation is heartfelt.

Upper left corner of cardboard frame of group portrait, with printed writing by Liang Ch'i-chao

Related Contents: