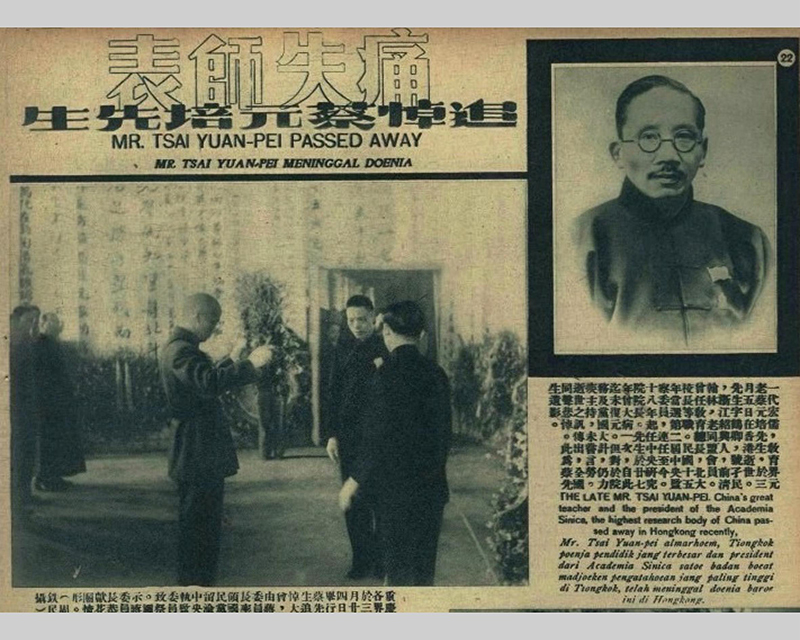

Mr. Ts'ai Yüan-p'ei (蔡元培先生), the pre-eminent Chinese educationist, passed away on 5th March 1940 in Hong Kong, and was buried at the Hong Kong Aberdeen Chinese Permanent Cemetery. In view of his life long advocation of academic freedom and anti-communism platform, some communist agitator (s) from mainland China visited Hong Kong on 14th November 2019 to vandalize the tomb of Mr Ts'ai Yüan-p'ei. The author of this article, Ms P'an Hui-lien, inspected the tomb shortly after, and wrote this long essay about the human stories and evolution of the tomb in a span of nearly eighty years, in remembrance of a great Confucian scholar.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

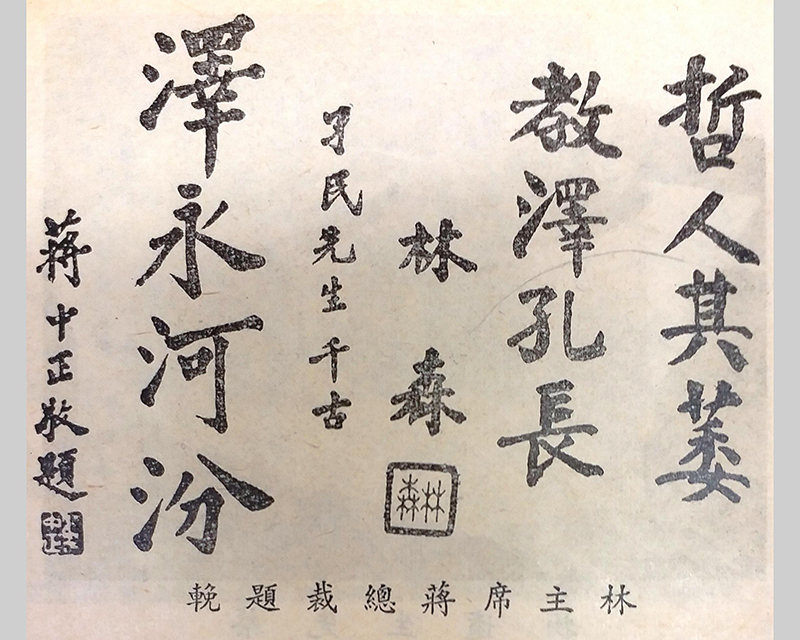

Epitaphs for T’sai Yüan-p’ei written by Lin Sen, Chairman of the National Government of the Republic of China, and Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek in 1940

A Hong Kong tomb for a noble soul;

Spring tribute, Autumn homage,

to Ts’ai Ch’ieh-min.

Whose hands are these?

So heartless, this desecration of the tomb?

Defacing his name, ravaging the epitaph;

such insult to our forefather!

By a Hong Kong netizen

Eighty one years ago, on 5th March 1940, the great educationist Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei (tzu Ch’ieh-min), who advocated “Intellectual Freedom, Tolerance and Inclusiveness”, passed away in Hong Kong at the age of seventy two. At that time, China was in the middle of the Japanese invasion, Ts’ai was hence buried at the Hong Kong Aberdeen Chinese Permanent Cemetery 1. His family had originally planned to bury him in his hometown, Shan-yin 2 of Chekiang province when the war ended. No one could foretell the drastic turn of political events, civil war followed Japan’s defeat, and the body of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei has since been permanently laid to rest in Hong Kong.

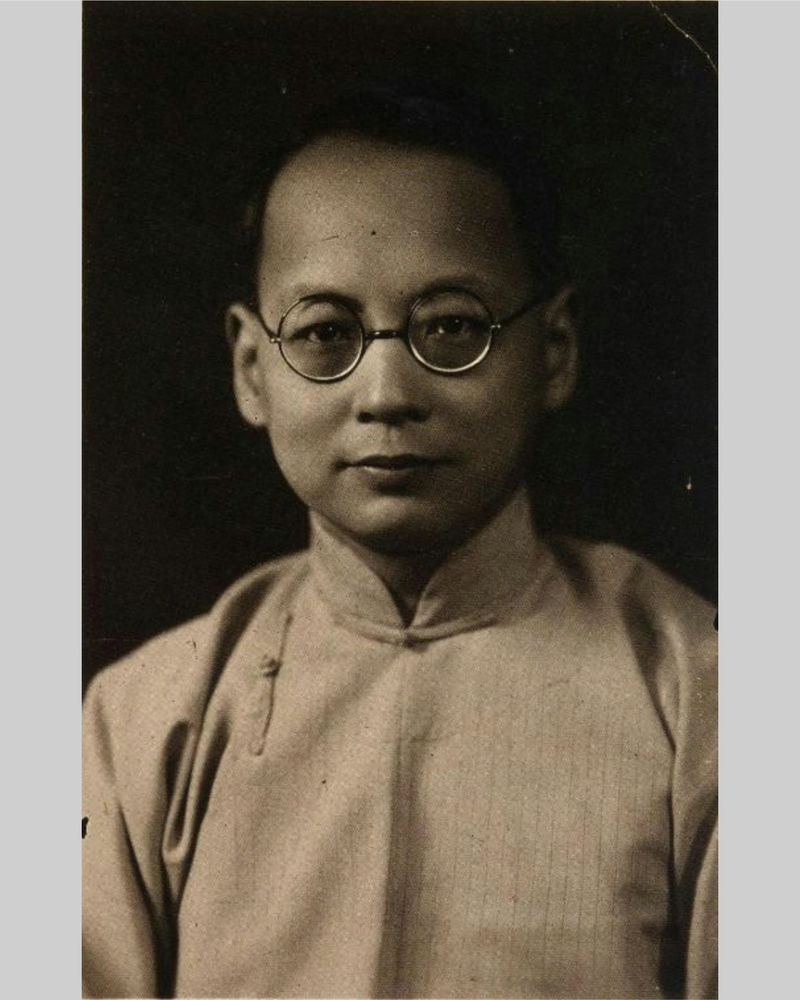

Portrait of T’sai Yüan-p’ei

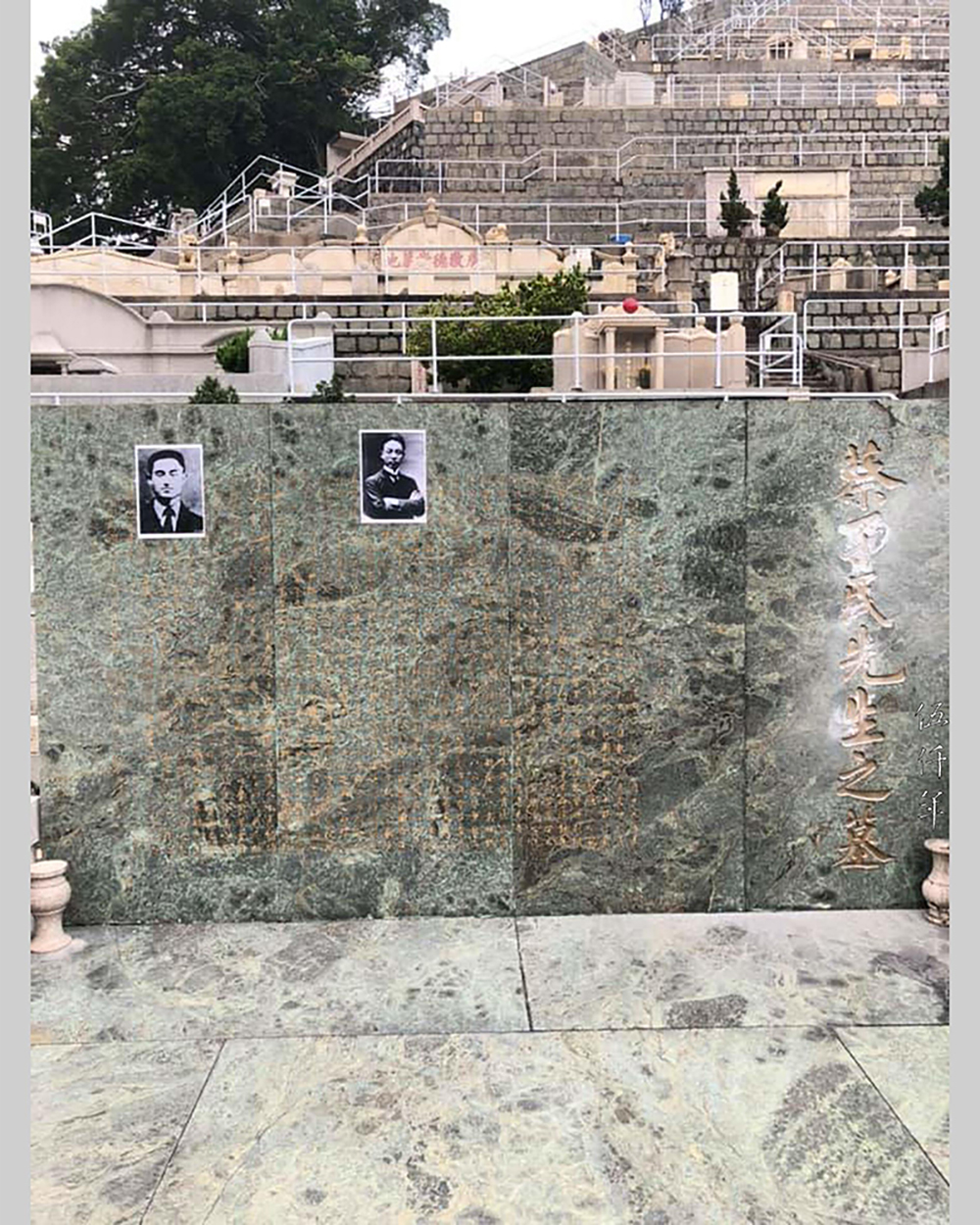

After many years of war and social unrest, rebuilding and renovation, the Ts’ai tomb that was located unperturbed at the Aberdeen hilltop, was suddenly thrust into unannounced calamity in the year 2019. During the centenary of the May Fourth Movement, of which Ts’ai was intimately involved, there was a left wing netizen extremist from mainland China, probably unhappy with the months of anti-government protests in Hong Kong, and recalled the anti-communist stand of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, came to Hong Kong on 14th November 2019, to desecrate the tombstone of Ts’ai. The upper five of the seven Chinese characters on the tombstone: Ts’ai Ch’ieh-min hsien-sheng chih mu (蔡孑民先生之墓 The Tomb of Mr. Ts’ai Ch’ieh-min) were “sandblasted for a while” 3 and photographs of two early communist members, Wang Shou-hua and Chao Shih-yen, were pasted onto the tombstone.

View of T’sai Yüan-p’ei tomb in Hong Kong Aberdeen Chinese Permanent Cemetery after vandalization on 14th November 2019

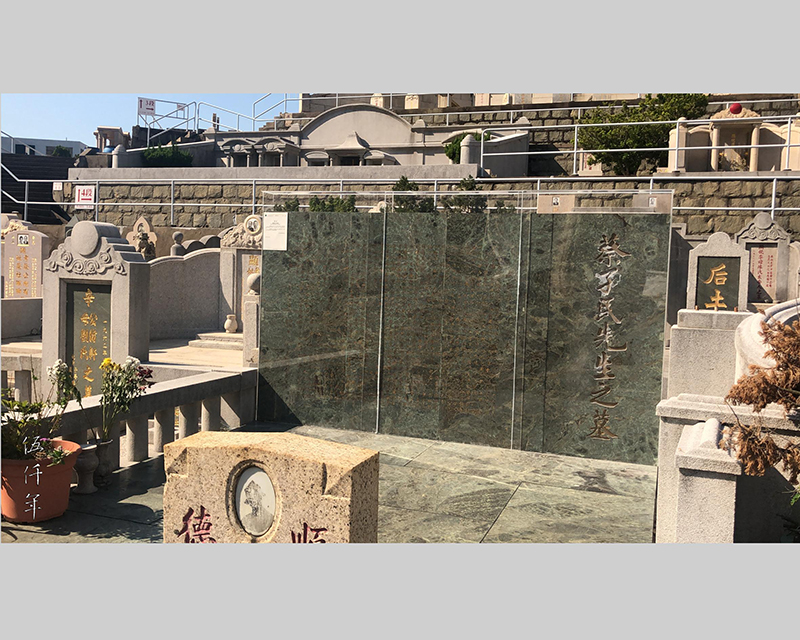

View of T’sai Yüan-p’ei tomb in Hong Kong Aberdeen Chinese Permanent Cemetery after vandalization, temporary acrylic protective panels were installed. Photograph taken on 21st November 2019

This mainland netizen claimed that he was in “utter despair and devoid of tears”, and on the day of vandalism, declared on the internet that it was his handiwork. In the past, he had posted articles criticizing Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei for being a member of Kuomintang, that in 1927, when Kuomintang purged the communists from the party, Ts’ai was “an anti-communist murderer” who persecuted the communists. Wang Shou-hua and Chao Shih-yen both died in that year.

This incident attracted broad attention in Hong Kong and overseas. Peking University Hong Kong Alumni Association posted an article condemning the vandalism two days afterwards, and claimed that the relatives of Ts’ai had asked the Association to act on their behalf, to report this matter to the Hong Kong police, to hope for cooperation between the police from the two territories, to investigate as soon as possible, and to ensure that the perpetrator would receive due punishment. However there has been no further news regarding this case.

The management of the cemetery soon took down the two photographs, and added some acrylic panels to protect the tombstone. The few large damaged Chinese characters were seen to be repaired a year later.

Detail of vandalized tombstone. Photograph taken on 21st November 2019

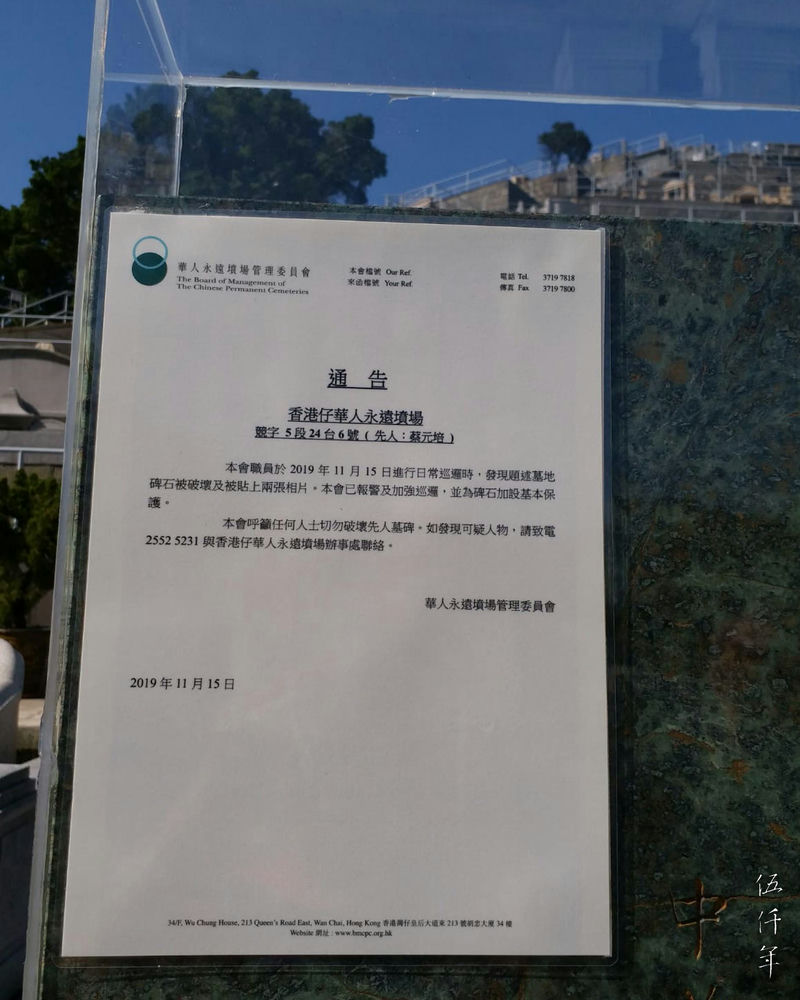

Official notice from cemetery management pasted on temporary acrylic protective panel. Photograph taken on 21st November 2019

This incident heightened the author’s acute interest in the history of the Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei tombstone. After sustained investigations, it was discovered that the origin of the tombstone was rather mysterious. Many stories related to the Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei tombstone were incorrect, yet they spreaded ever more.

Family and friends paid final respect to T’sai Yüan-p’ei on 10th March 1940. Photograph courtesy Tung-fang hua-k’an Magazine

Family and friends started procession to memorial ceremony at South China Athletic Association Stadium on 10th March 1940. Photograph courtesy Tung-fang hua-k’an Magazine

The son T’sai Wu-chi holding the spirit tablet for the procession on 10th March 1940. Photograph courtesy Tung-fang hua-k’an Magazine

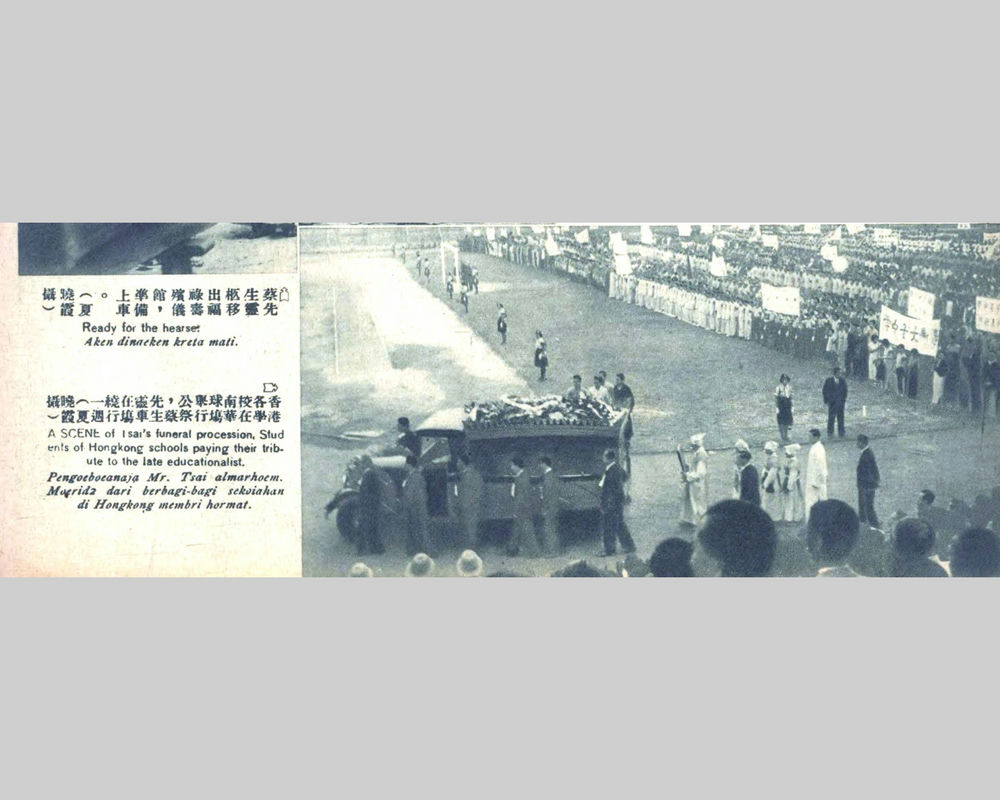

From the information we know, five days after the death of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, on 10th March 1940, there was a solemn public memorial ceremony in the South China Athletic Association Stadium on Caroline Hill Road for all sectors of society, and over 10,000 people participated. Those shops, institutions and schools that flew the Republic of China flag all lowered the flags to half-mast. The coffin of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei was carried to the hearse by a selected group of pallbearers, fourteen alumni of Peking University 4. In the afternoon on that day, the coffin arrived at Tung Wah Coffin Home in Pokfulam, Western District. The whole journey was chronicled in detail by many Chinese newspapers. But when did the coffin move to Aberdeen Chinese Permanent Cemetery from Tung Wah Coffin Home? How was the burial ceremony? Who wrote the seven Chinese characters Ts’ai Ch’ieh-min hsien-sheng chih mu (蔡孑民先生之墓 The Tomb of Mr. Ts’ai Ch’ieh-min) on the tombstone? When the tomb was renovated in 1978, an epitaph was added, and who composed it? Who wrote the calligraphy? In truth, for a long time, detailed record was absent.

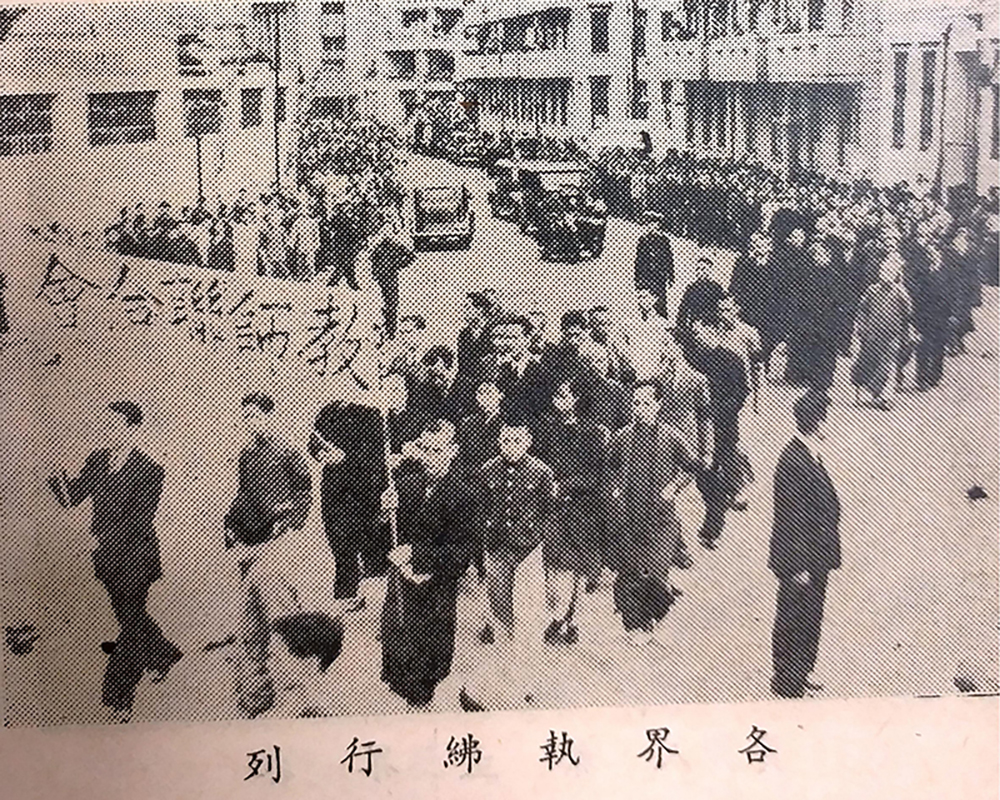

Representatives of different sectors of Hong Kong society walked in procession to the memorial ceremony at South China Athletic Association Stadium on 10th March 1940. Photograph courtesy Tung-fang hua-k’an Magazine

Representatives of different sectors of Hong Kong society stood on ceremony inside South China Athletic Association Stadium on 10th March 1940. Photograph courtesy Tung-fang hua-k’an Magazine

Representatives of different sectors of Hong Kong society watched the hearse passing by inside South China Athletic Association Stadium on 10th March 1940. Photograph courtesy Tung-fang hua-k’an Magazine

According to accounts in the Hong Kong Kung Sheung Daily News and Ta Kung Pao on 8th October 1940, after completing the numerous memorial ceremonies, members of the funeral committee convened a final meeting on 7th October. But the meeting only recorded that a sum of one hundred thousand dollars had been raised for a memorial foundation to cover the education costs of Ts’ai’s children, there was no news regarding the burial. Examining the diary of one of the members of the funeral committee, Ch’en Chün-pao, there was coverage on the memorial ceremony, but nothing on the burial.

In the next year, on 19th March 1941, the Alumni Association of the National Peking University in Hong Kong 5, which had been most active in assisting the funerary affairs of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, convened an annual meeting chaired by Yeh Kung-ch’o6 who reported on the activities of the past year. According to contemporary newspapers, there was no mention of the burial. Examining the Chronological Record of Yeh Kung-ch’o7 there was nothing regarding the burial neither.

Until 11th January 1958, on the 90th birthday anniversary of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, the Central Daily News in Taiwan published two letters 8 concerning the tomb of Ts’ai. For the first time, there was written record regarding the tomb of Ts’ai. In one of the two letters, written after the Second World War and at the end of 1946, the private secretary of Ts’ai in his later years, Yü T’ien-min 9, entrusted the Cantonese educationist Huang Lin-shu10 to inspect the condition of the Ts’ai tomb in Aberdeen Chinese Permanent Cemetery, whilst on a business trip to Hong Kong. He received a letter from Huang after inspection, and on 9th January 1947, he in turn wrote to tell Ti Ying, his classmate from Peking University. The second letter was Huang Lin-shu’s original reply letter to Yu T’ien-min.

In Huang Lin-shu’s letter of 1946, he wrote: ”After the winter solstice of December, I made a special trip to pay tribute, and laid a wreath. Yeh wrote seven characters for the tombstone, the red color was bright and fresh, the stone was intact, and a shepherd boy helped me to clear the dust. I loitered there for a long time, unable to part. Because I was directed by the gravekeeper, despite the thousands of tombs, there was no mistake. ………. In the future when I visit Hong Kong, and if time allows, I will certainly come to pay tribute again.” In the letter by Yu T’ien-Min to Ti Ying, it said: ”This is indeed a piece of great news to relieve the apprehension of those concerned, I wish to inform you in particular, as we are unable to visit Hong Kong to pay our tributes, we can accept this as solace.”These two letters were likely handed to the Central Daily News for publication by Yu T’ien-min. This could be regarded as the earliest written record related to memorial activity at the Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei tomb.

In the letter, he mentioned: “Yeh wrote seven characters for the tombstone.” This referred to the seven characters engraved on the tombstone: “Ts’ai Ch'ieh-min hsien-sheng chih mu”. These were written by Yeh Kung-ch’o. Since the calligraphic style of Yeh Kung-ch’o was relatively easy to recognize, it had been long rumored in the cultural world that the seven Chinese characters on the tombstone were written by him. However the earliest written record that elucidated Yeh as the calligrapher, was not until 1985, in the Biography of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, written by a Shanghai scholar T’ang Chen-ch’ang. T’ang had interviewed the descendants of T’sai, most likely he obtained this information from them.

Portrait of Yeh Kung-ch’o

In the beginning of 1963, a close friend of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, Wang Yün-wu 11wrote an article: Ts’ai Ch’ieh-min hsien-sheng yü wo (Mr. Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei and Myself)12 in the monthly magazine Ch’uan-chi wen-hsüeh. In the last paragraph, it was revealed for the first time that it was him who assisted Ts’ai’s burial: “Regarding my handling of the funeral arrangements, the coffin was temporarily housed at Tung Wah Coffin Home, to be buried at the Aberdeen Chinese Permanent Cemetery.” Nevertheless, he did not disclose details of the burial.

Portraits of T’sai Yüan-p’ei (left) and Wang Yün-wu (right). Photograph courtesy Tung-fang hua-k’an of March 1940

The author was later informed by the management of the Cemetery, that the tombstone of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei was first erected in October 1940, which meant that the coffin of Ts’ai was housed at Tung Wah Coffin Home for seven months before being buried. Why should the burial be handled so discreetly? Why was the original tombstone so simple? Why was it not quite 1.52 meters (5 feet) tall, and only engraved with seven characters?

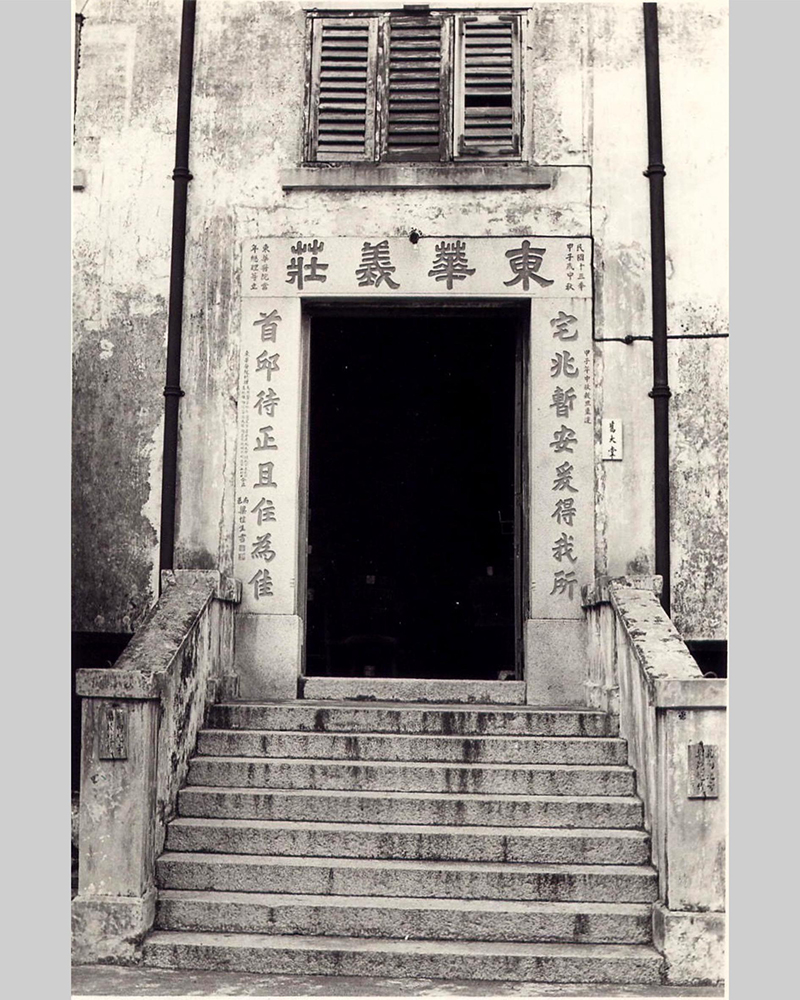

The coffin of T’sai Yüan-p’ei was housed at Tung Wah Coffin House before burial

The author reckoned that it had to do with the encroaching war approaching Hong Kong. It was likely that family members and friends of Ts'ai did not want outsiders to know where he was buried, to evade disturbance and vandalism. After the death of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei’s first wife Wang Chao in 1900 , she was buried at Pa-chia Ts’un in Hei-lung T’an, Shensi province. On 27th January 1937, the tomb was unexpectedly raided. This was reported in the Central Daily News on 7th February 1937. Antecedent could not be forgotten, the family members of Ts’ai inevitably worried that such incident might reoccur. Furthermore, to bury in Hong Kong was originally a temporal measure, such arrangement need not be extravagant nor expensive.

On Christmas Day 1941, the Japanese army occupied Hong Kong. The widow of Ts’ai, Chou Chün 13, and the three children (Ts’ui-ang, Huai-ssu, Ying-to), went through many dangers and obstacles. They changed their names and identities in 1943, mixed together with other refugees to board a ship to Shanghai, and lived incognito until the end of war. When peace came, on 10th May 1947, the Nationalist government decreed and prepared a state funeral for Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei. But the civil war continued, and the plan for a state funeral was called off. In 1949, the government in mainland China changed flag. Chou Chun and four children stayed in the mainland, only the son Ts’ai Pai-ling lived overseas in France. Not until the reform and opening up of mainland China in 1981, did the descendant of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, the son Ts’ai Huai-ssu came to Hong Kong for the first time to pay his tribute at the tomb.

A group portrait of members of the Alumni Association of National Peking University in Hong Kong, taken on 17th December 1957, the anniversary celebration of National Peking University.

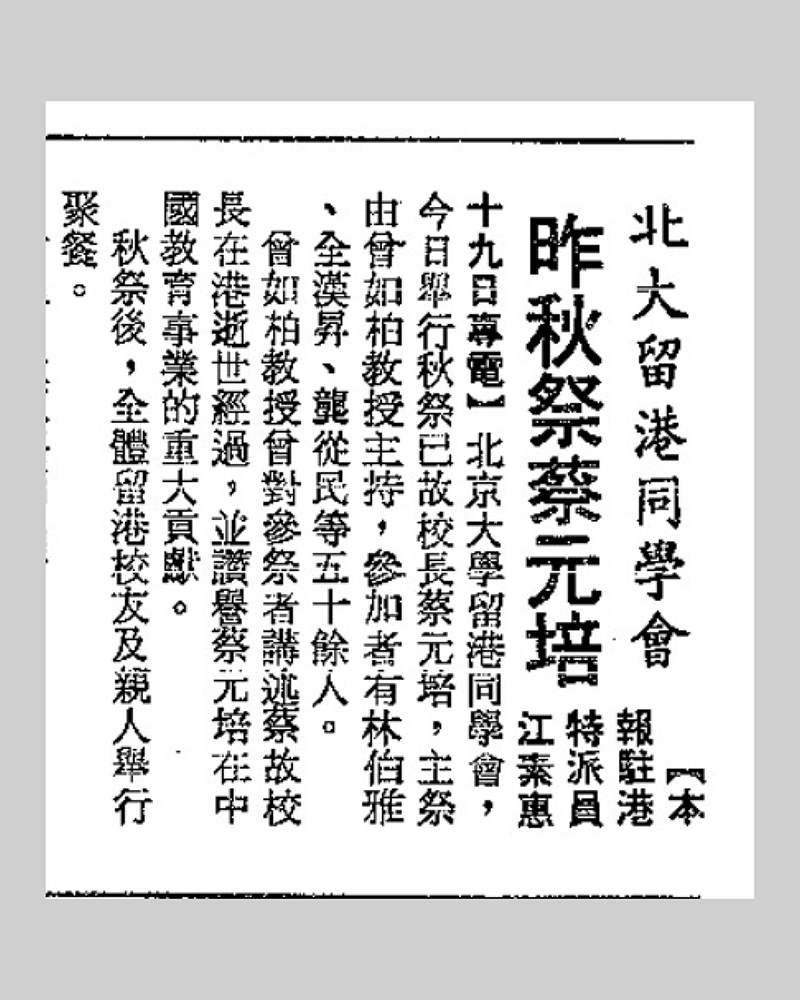

Notwithstanding, the Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei tomb in Hong Kong has not been neglected since 1949. Every year, the Alumni Association of the National Peking University would hold a memorial ceremony at the tomb in Spring and Autumn. From 1950 to 1970, the Overseas Chinese Daily News in Hong Kong virtually covered this activity every year. In the 1962 edition of the Alumni Association journal, there was a group photograph taken at the tomb, with articles and poems by alumni to record the memorial ceremony.

One of the alumni of National Peking University who participated in the Spring memorial ceremony on 12th April 1959, Yü Yu-sun 14, wrote an article after the event, titled Yeh Ts’ai Ch’ieh-min hsien-sheng mu (Paying Tribute at the Tomb of Mr. Ts’ai Ch’ieh-min), which was published in the Hong Kong monthly magazine Tzu-yu jen (Free Man)15 It was a detailed account of the Spring memorial ceremony.

The article recounted that those who participated in the memorial ceremony every year in the last twenty years, were members of Academia Sinica and alumni of the National Peking University. In April 1940, they initiated the memorial ceremony for Mr. Ts’ai at Mei-shu Hsiao Street in Chungking. Since then it became a tradition, every year both parties jointly organized the memorial ceremony. According to Chinese traditional customs, in the first three years, the memorial ceremony took place on the date of his death. After the first three years, the date of the ceremony was changed to his birthday, 11th November. The memorial ceremony was a public event, all were welcomed to participate. There were two parts, one was an address about the life of Mr. Ts’ai, the other was an academic oration. The speaker of the academic oration was invited by Academia Sinica, the content printed for remembrance.

An admission advertisement of Yüan-p’ei College

After 1949, there were approximately two hundred graduates of National Peking University in Hong Kong, many of them were involved in cultural and educational work. Soon after the death of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, on 14th March 1940, the Alumni Association of the National Peking University in Hong Kong had resolved to establish Yuan-p’ei College, in remembrance of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei. However the plan did not materialize until the winter of 1959, when the Association at long last established a four-year institution of higher education, named Yuan-p’ei College. The first chairman of the board of trustees was T’an Chen-ou, the president was Ts’ui Lung-wen, both members of the Alumni Association of the National Peking University. The College was first located at Great South Street, Sham Shui Po, not long after, moved to No. 992 Canton Road, then to No. 27 Shandong Street. The assumption is the College continued till mid 1970’s before closing.

In these years, the name of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei and the well-being of his descendants in mainland China were all suppressed and harassed by the Communist Party to different extends. While in Hong Kong, the Alumni Association of the National Peking University, the teachers and students of Yuan-p’ei College, took action every year without interruption, to pay tribute to Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, and organized those from the cultural world, to participate in the Spring and Autumn memorial ceremonies at the tomb.

At that time, there was no internet, the flow of information was not as convenient as now. The mindfulness of the Hong Kong government and of the average citizen on history and culture was not as amplified as around 1997. Only the alumni of Peking University and a handful of academia and those interested in culture were knowledgeable about the tomb of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei. Hence some people were misled to think that the Ts’ai tomb was not looked after nor memorialized.

In late 60’s, the Alumni Association of National Peking University held a spring memorial ceremony at the tomb. Photograph courtesy Ms. Hsiang Ying-jen

This writer had the opportunity to interview the scholar Lu Wei-luan 16, who spent thirty years researching the migrant cultural figures in Hong Kong. She recalled that when she first studied at New Asia College in the early 60s, she did not know that Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei was buried in Hong Kong. Only in 1966, when she started to teach at a secondary school, was she then told by the scholar Zuô Shun-sheng, that the tomb of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei was in Aberdeen Chinese Permanent Cemetery. She went to find it, on one hand, because of her admiration for Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, on the other hand, in her teachings she would mention the May Fourth Movement, and felt that if her students could visit the tomb of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, it could help them better understand this segment of history.

Although at the time she was unclear the exact location of the Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei tomb, the cemetery was not too far from her residence. In her youth she enjoyed hiking, and with zealful enthusiasm, she searched the cemetery row by row. She could not remember whether she located the tomb on the second or the third visit, she only recollected that the first visit was a failure. After she found it, many times she took those students interested in literature and history to the tomb. Some of the earnest students became familiar with the route, and organized tomb visits on their own, so that other students could also better understand Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei and the May Fourth Movement. She was much gratified.

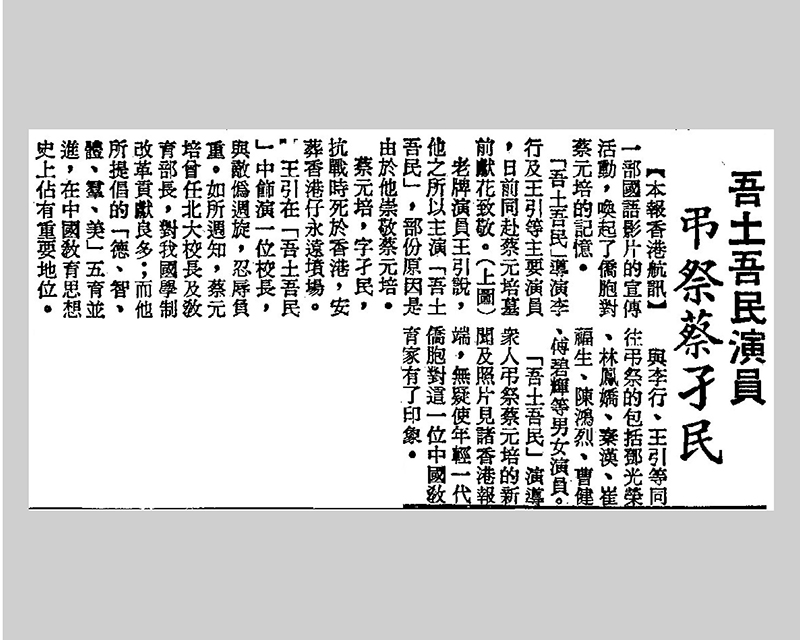

News coverage on 2nd April 1975 by United Daily News Taiwan, of the actors, actresses and director of the movie My Country and My People (吾土吾民) who paid respect at the tomb.

In the 1970s, there appeared two groups of unusual visitors who came to pay tribute, and a great change also transpired. At the end of March 1975, the Taiwan film My Country and My People, an investment of the Ma Film Company in Hong Kong, was to be released in Hong Kong cinemas. The movie director Li Hsing-ho and the nine main actors and actresses: Wang Yin, Teng Kuang-jung, Ch’in Han, Lin Feng-chiao, Ts’ui Fu-sheng and others, when on their visit to Hong Kong to promote the film, visited the tomb of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei to lay a wreath.

The movie was about the Sino-Japanese War, Wang Yin played the role of a secondary school headmaster, together with teachers and students, they bore the burden to deal with the Japanese enemy. The film company contended that the visit to the tomb was not just an activity to coordinate with film promotion, but intended to raise the awareness of the young generation to acknowledge and remember Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei.

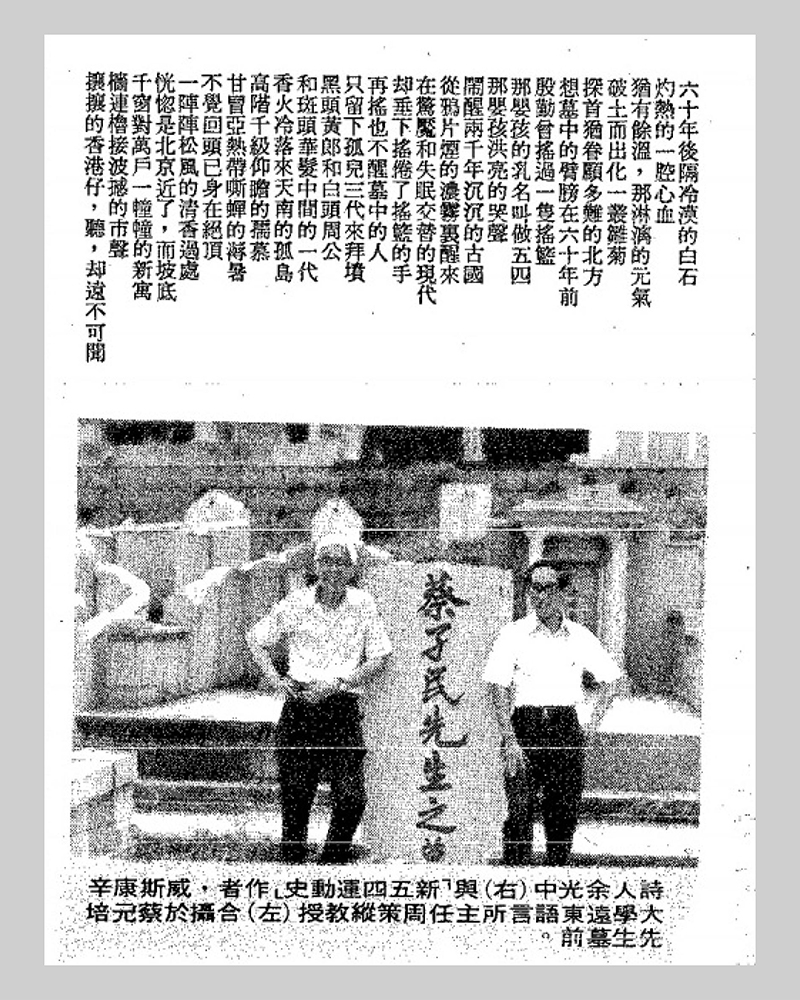

In June 1977, Yü Kuang-chung visited the tomb. Photograph courtesy Hong Kong Commercial Press

On 4th May 1978, Yü Kuang-chung published a poem in remembrance of T’sai Yüan-p’ei in Ming Pao Magazine, accompanied by a photograph taken at the tomb. Chou Tsung-ts’e (left) and Yü Kuang-chung (right)

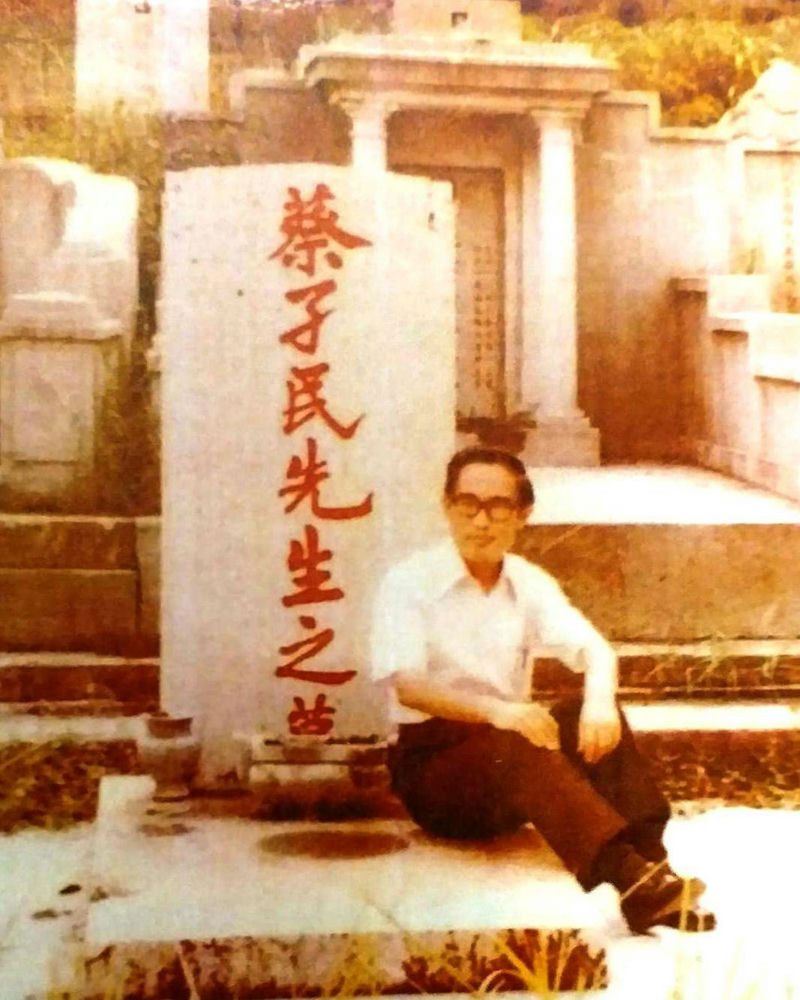

Moreover, in the middle of 1977, Professor Chou Tsung-ts’e 17, an authority of the May Fourth Movement who resided and taught in America, visited Hong Kong. On 25th June, he invited two poets who were teaching at the Chinese University, Yü Kuang-chung 18 and Huang Kuo-pin 19, to pay tribute together at the tomb of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei. According to the short essay published by Yü Kuang-chung one year later, before embarking on their trip, Huang Kuo-pin telephoned the Aberdeen Chinese Permanent Cemetery to make enquiries. Remarking on the man who picked up the phone: ”the gravekeeper clearly did not know who was Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, and after some questioning, he hesitantly said: Perhaps you are looking for the tomb of Teacher Ts’ai. That I know, I can lead you there.” He further wrote: “Above and below the hill path, tombstones were upright and sideway, if it were not for the solicitous guidance of the gravekeeper, it would truly be: Treading the Mang mountain thirty miles across, one still cannot tell where the burial is. The plan of the Ts’ai tomb was narrow, the construction scanty, the height of the tombstone was lower than a human figure. Apart from the seven red characters: Ts’ai Ch’ieh-min hsien-sheng chih mu, there was no date of the construction of the tomb, no name of the person who wrote the characters. Comparing to the surrounding tombstones with eminent names, grand columns and pavilions, it looked very desolate.” It seemed that they were unaware of the perseverance and deed of the old alumni of National Peking University in Hong Kong.

After their gathering, each wrote poetry for commemoration. Of the three, Huang Kuo-pin was the first to publish his poem. He wrote a modern poem Yu Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei mu (遊蔡元培之墓 A Walk at the Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei Tomb), it was compiled into his anthology Ti-chieh (地劫), and was published in October that year. Chou Tsung-ts’e wrote a modern poem Wan-shih: Ts’ai Ch’ieh-Min hsien-sheng chih mu (頑石-蔡孑民先生之墓 Resolute Rock-The Tomb of Mr. Ts’ai Ch’ieh-min) and a classical poem: Hsiang-kang fang Ts’ai Ch’ieh-min hsien-sheng chih mu (香港訪蔡孑民先生之墓 Visiting the Tomb of Mr. Ts’ai Ch’ieh-Min in Hong Kong). They were published on two separate pages accompanied by four photographs of the tomb visit, in the November 1977 issue of Ming Pao Monthly. Yü Kuang-chung was the last to publish his poem. Ten months after the visit, on 5th April 1978 Ch’ing-ming Festival, he finished composing the modern poem Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei mu-ch’ien (蔡元培墓前 In front of the Tomb of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei). He published it in the May 1978 issue of Ming Pao Monthly, as well as in the 4th of May Literary Supplement of China Times Newspaper in Taiwan.

On 7th May 1978, after the renovation of the tomb, the Alumni Association of the National Peking University held a spring memorial ceremony.

A few days later, on 7th May 1978, the Alumni Association of the National Peking University organized a magnificent spring memorial ceremony at the tomb of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, taking into consideration that the enlargement and renovation of the tomb was just completed, and appeared anew! The Alumni Association invited nearly a hundred cultural and academic personages in Hong Kong to participate in the ceremony, presided by Li Huang, the former professor of Peking University. The chairman of the Alumni Association Lin Po-ya recited the epitaph. Huang Lin-shu, aged eighty five, gave a speech, praising both the erudition and virtues of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, and deemed him worthy to be a role model for future generations.

In recent years, a number of media reports claimed that because of the remembrance poems composed by Chou Tsung-ts’e and Yü Kuang-chung after visiting the Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei tomb, the cultural world was drawn to attention by reading their lamentations that the tomb was crude and hard to find, hence expedited the joint efforts of the Alumni Associations of National Peking University in Hong Kong and Taiwan to renovate the tomb. However, this was a different view to that of the Alumni Associations.

News coverage of the spring memorial ceremony on 7th May 1978.

One of the participants of the 7th May 1978 memorial ceremony was Professor Chin Yao-chi 20, in his interview by the author, he said that he was at the time president of New Asia College of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. After the ceremony, he recorded the day’s activities and his thoughts in a Chinese article: The Academic World Symbolized by Mr. Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei - Thoughts on the Completion of Mr. Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei New Tombstone. It recounted the story he learned from the Alumni Association of the National Peking University, that they had observed way back in 1968, on the 100th birthday anniversary of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, the tomb was dilapidated and there was proposal for renovation. Chin believed that tomb renovation was a major undertaking, ample time was necessary for planning, it was impossible to conceive this by the end of 1977, and finished construction in April 1978.

According to the book I-tai jen-shih-Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei ch’uan (Teacher of a Generation-Biography of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei)21, the alumni of National Peking University decided to renovate the tomb in 1976. The author reckoned that be it 1968 or 1976, either way, it was impossible that the alumni only decided to renovate the tomb after the visit by Chou Tsing-ts’e, Yü Kuang-Chung and Huang Kuo-pin in 1977.

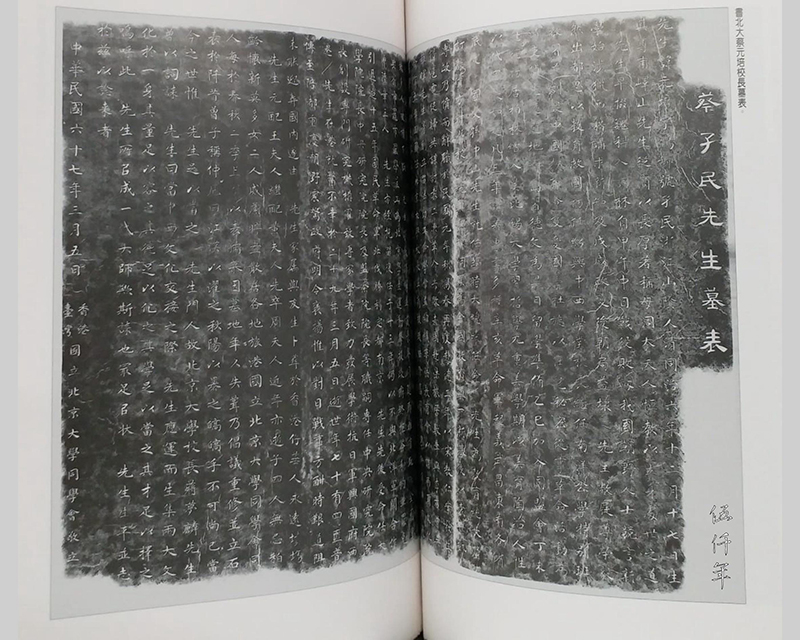

The new tomb is five times wider than the old one, the floor is covered by marble. The original short white stone tablet was discarded, the new stone tablet used four rectangular pieces of green granite from Hua-lien, Taiwan. The total width is approximately 300 centimeters (ten feet), the height is 167 centimeters, the depth is 15 centimeters. Apart from retaining the calligraphy of the seven characters on the original stone, a thousand word epitaph has been engraved on the green granite to recount the life story of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, infilled with gold coloring. The renovation of the tomb cost a hundred thousand Hong Kong dollars. The Alumni Association of the National Peking University did not disclose the designer of the tomb. Who composed the epitaph? Who wrote the calligraphy? Reports in newspapers in the following day did not reveal such information.

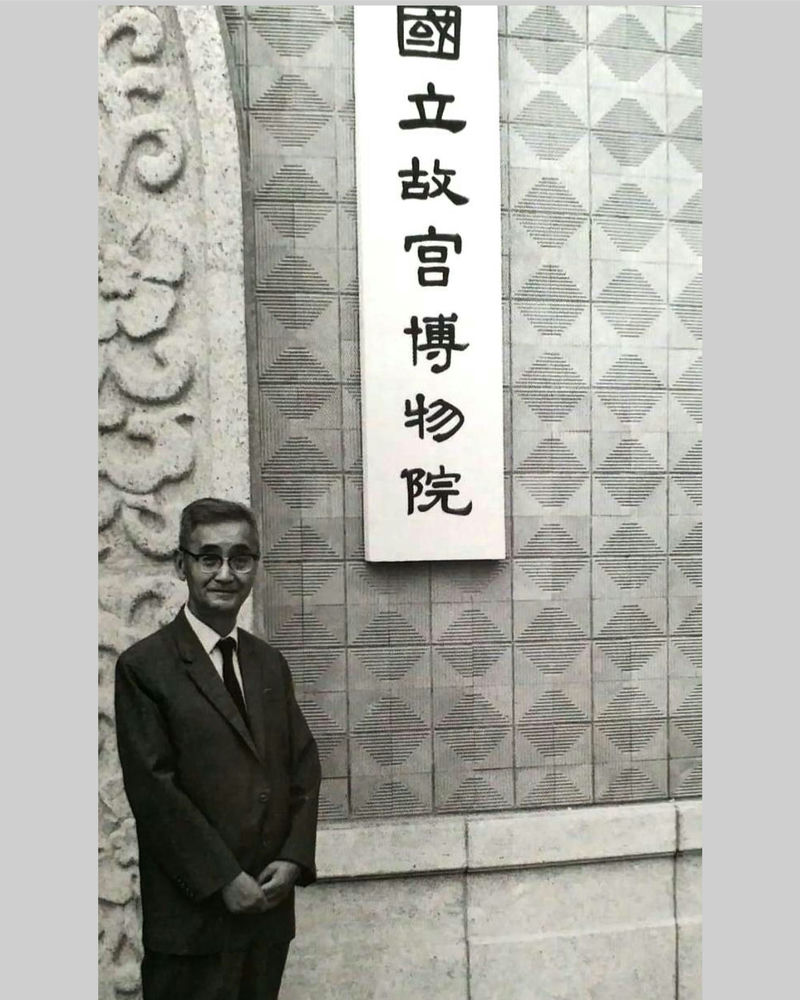

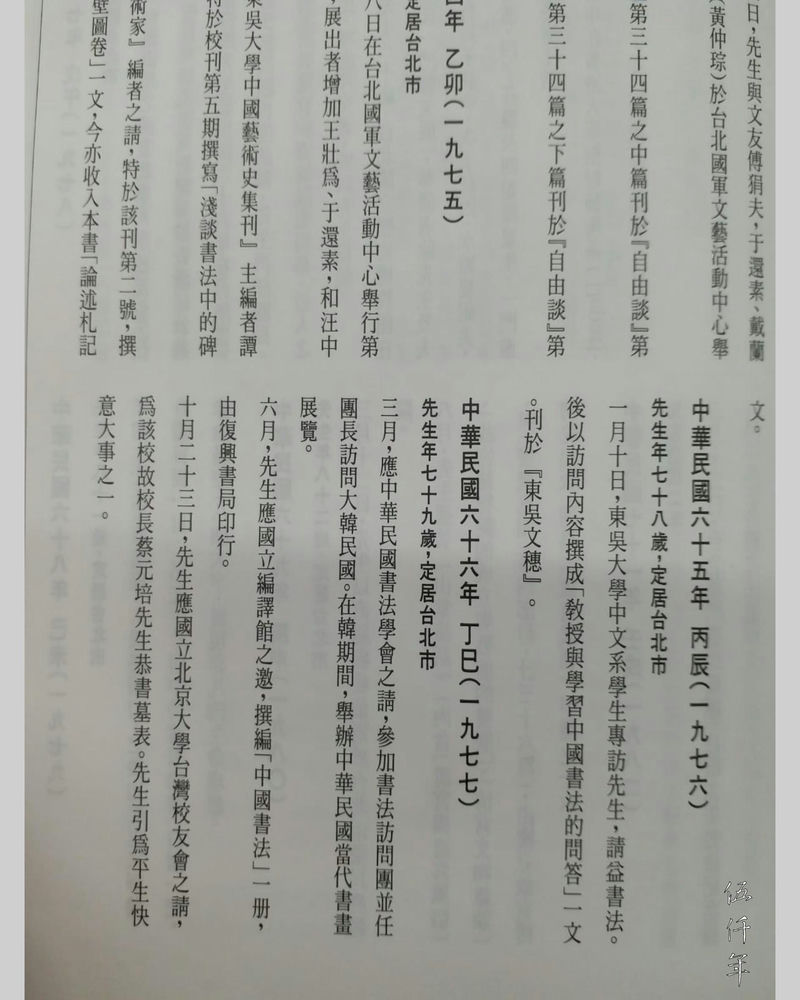

For some inexplicable reason, from mid 1980s, there were rumors in mainland China that the epitaph was calligraphed by Professor T’ai Ching-nung from National Taiwan University. According to the article written by Professor Chin Yao-chi, the epitaph was calligraphed by the deputy director of the National Palace Museum in Taipei, Chuang Yen 22, also a well known calligrapher. The writer telephoned the son of Chuang Yen, Chuang Ling in Taipei to ascertain, and confirmed that his father Chuang Yen did accept the invitation from the alumni of National Peking University, and calligraphed the epitaph in October 1977 for the newly renovated tomb of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei. The composition of the epitaph was provided by the Alumni Association of the National Peking University. In the diary of Chuang Yen, there was an account of this calligraphic work, and he regarded this as one of his joyful and important high points in life. After Chuang Yen passed away in 1980, his family compiled his biography, diary and calligraphic works into a book titled The National Palace Museum, Calligraphy, Chuang Yen, published in 1999. There was an account of this calligraphy, illustrated with a photograph of the ink rubbing of this epitaph.

Deputy Director Chuang Yen of the National Palace Museum in front of the museum signage calligraphed by himself

Inner page of The National Palace Museum, Calligraphy, Chuan Yen that chronicled his writing of the epitaph

Inner page of The National Palace Museum, Calligraphy, Chuan Yen that illustrated the ink rubbing of the tombstone

The author was also informed by Professor Ho Kuang-yen 23 of New Asia Institute of Advanced Chinese Studies, that the epitaph was composed by Professor Wang Chao-sheng 24, a member of the Alumni Association of the National Peking University, and this was disclosed by Wang himself. After Wang Chao-sheng retired from the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 1971, he went to teach at the Research Institute of Chinese Literature and History of Chu Hai College, where Ho Kuang-yen was also teaching, and became close friends. Professor Ho Kuang-yen recounted that a number of colleagues at the Institute also knew Wang composed the epitaph, as he was unskilled in calligraphy, the alumni of National Peking University separately sought another person to execute the calligraphy. The writer searched the writings of Wang Chao-sheng, and in his Huai-ping shih hsü-chi (懷冰室續集) published in 1984, there was the full text with punctuation marks of Ts’ai Ch’ieh-min hsien-sheng mu-piao (蔡孑民先生墓表 The Epitaph of Mr. Ts’ai Ch’ieh-min). However the epitaph engraved on the tombstone did not use punctuation marks. The tombstone was dated 5th March 1978, the 38th death anniversary of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei.

Portrait of Wang Chao-sheng

The full text of the epitaph has been copied here, based on the engraved words on the tombstone. The punctuation marks and the three annotations have been added by the writer.

“Mr. Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, tzu Ho-ch’ing, hao Ch’ieh-min, native of Shan-yin, Chekiang province. He was born on 17th December, the 6th year of the T’ung-chih reign (1867). His father Mr. I-Shan 25 was a merchant, known as a careful and generous man. His mother Ms. Chou constantly guided him on ways of conducting himself. When young, he attained high ranking in public examination and entered the Imperial Academy. Since China’s defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War, our countrymen competed to discuss New Learning, he began to study Western books cursorily, and sought new knowledge. After the Hundred Days’ Reform, court affairs got worse. Mr. Ts’ai did not care for prestige nor eminence, he left the capital, and thought of employing education to save the country. In the beginning, he took the office of headmaster of Shao-hsing chung-hsi hsüeh-t’ang, then he was lecturer of special class at Nanyang University. At the same time, he founded Chinese Education Association and Patriotic Study Society. He then participated in revolutionary activities in Shanghai, which was detected by Ch’ing officials, and fled to Ch’ing-tao, to study German in preparation to further his education abroad. He joined Tongmenghui in i-ssu year (1905), and travelled to Germany in ting-wei year (1907). Initially he lived in Berlin, then attended Leipzig University, with particular interest in the study of aesthetics. He wished for art to cultivate life, in place of religions. He followed this course for three years, and translated many books of special topics. After the uprising of the Revolutionary Army in Wu-ch’ang in hsin-hai year (1911), provinces in the east and south succumbed. The founder of the Republic, Dr. Sun Yat-sen was appointed provisional president, Mr. Ts’ai was appointed minister of education, devising education policies and syllabuses for schools, and building a new education foundation for the whole country. Later on, when Yüan Shih-k’ai turned dictatorial, he resigned in anguish. In the Autumn of the first year of the Republic (1912), he left for Germany with his family. In the 2nd year of the Republic (1913), after the assasination of Sung Chiao-jen, he was prompted by a telegraph from Shanghai to return to China to plan the Constitutional Protection Movement. When the Second Revolution failed, he left China and lived in France for a few years. Together with Li Shih-tseng and Wu Chih-hui, he founded the Work-Study Program in France for Chinese students, and established the Chinese French Cooperation Society to seek cultural cooperation between the two countries. In the 5th year of the Republic (1916), he returned to China to take up the posting of president of Peking University. Innovative university policies were introduced, old habits were dispelled, and academic freedom was advocated. From then, traditional learning and new knowledge were both sanctioned and embraced, the two gradually flourished. The academic atmosphere of the whole country was greatly altered. In the 8th year of the Republic (1919), the May Fourth Movement took place, students in Peking rallied and protested against the Treaty of Versailles. They punished the traitors severely, and many were subsequently jailed. Mr. Ts’ai posted bail for their release, released a statement, and immediately left Peking. Strikes by merchants, students and workers took place in many important provinces and cities, to render support for the students in Peking. The government eventually refused to endorse the Treaty of Versailles, the trio Ts’ao Ju-lin, Lu Tsung-yü and Chang Tsung-hsiang were impeached, Mr. Ts’ai was retained and reinstated as president of Peking University. In the 13th year of the Republic (1924)26, he nevertheless resigned for not collaborating with the northern warlords. By the 15th year of the Republic (1926), the National Revolutionary Army was victorious in the Northern Expedition, and Nanking was pronounced the capital of the Republic. Mr. Ts’ai was consecutively appointed president of the University Yuan of the Republic of China, president of Academia Sinica, president of the Control Yuan. When he was president of Academia Sinica, specialized research departments were established, specialists and scholars were procured, commitment to the advancement of scholarship was pledged. The army against Japanese invasion arose, the capital of the Nationalist Government moved westward. Mr. Ts’ai was undergoing medical treatment in Hong Kong, unfortunately he passed away on 5th March 1940, aged seventy four. The sad news travelled back to Chung-ch’ing, the provisional capital, the government and the people were shocked, and the government issued a decree to commend Mr. Ts’ai. However, in the middle of the war against Japanese invasion, circumstance was difficult and roads were blocked, it was not possible to transport the coffin back to inland China for burial. Hence the family, friends and students buried the coffin of Mr. Ts’ai at the Aberdeen Chinese Permanent Cemetery. The first wife of Mr. Ts’ai was of the maiden surname Wang, the second wife with the maiden surname Huang passed away early, the third wife with the maiden surname Chou also passed away early. The four sons are: Wu-chi, Pai-ling, Huai-ssu, Ying-to, the two daughters are: Wei-lien27, Tsui-ang, and they live dispersed in different places. The Alumni Association of the National Peking University pay tribute at the tomb every year in Spring and Autumn, to express their veneration. The tomb had deteriorated with age, so there was proposal to renovate the tomb and build a tombstone by the path. In history, Tzeng-tzu said of Confucius: “ Cleansed by the Yang-tzu and Han Rivers, basked by the Autumn sun, such unsurpassed radiance.” In our time, only Mr. Ts’ai was worthy of this. Chiang Mon-lin, a student of Mr. Ts’ai and the former president of Peking University, wrote in a eulogy: “Mr. Ts’ai was born for the encounter between Eastern and Western cultures, he himself cumulated the two great cultures, his breadth was sufficient to contain them, his virtues were adequate to synthesize them, his erudition was profuse to sustain them, his endowment was ample to espouse them.” Alas! For this reason Mr. Ts’ai was a master of his era. This eulogy is reiterated for being the most descriptive of his life, to apprise those to come!

5th March, the 67th year of the Republic (1978), Respectfully erected by the Alumni Associations of National Peking University in Hong Kong and Taiwan”

Into the 1980s, through the impetus of cultural enthusiasts, there was a surge of interest regarding the tomb of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei. In January 1987, Wu Ta-yu, president of Academia Sinica in Taipei, came to Hong Kong to take part in activities at the Chinese University. On 9th January, Hsü Tung-pin and Lin Tse-jen from the Alumni Association of National Peking University, accompanied Wu to the tomb to pay tribute. Wu considered the epitaph a meaningful collectible, and asked the Alumni Association to assist in making an ink rubbing, which was later delivered to the Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei Room at Academia Sinica for its permanent collection. Wu remarked to journalists: When Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei was president of Academia Sinica, he was a primary school student. Later he enrolled as a student of Peking University, and became a junior member of Academia Sinica. It was a matter of moral duty to pay tribute at the tomb 28.

Apart from Wu Ta-yu, the World Chih-te Clan Association and the Ts’ai Clan Association organized a party of two hundred people on 7th November to visit the tomb, to commemorate the 120th birthday anniversary of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei. The eulogy was read by the distinguished geomancist Ts’ai Po-li 29.

On 25th October 1988, the 120th birth anniversary year of T’sai Yüan-p’ei, mainland China approved his children to participate in the memorial ceremony in Hong Kong. His children (third left and fourth left), the others are alumni. Photograph courtesy Ms. Hsiao Ying-jen

In October 1988, the cultural and educational circles in Hong Kong organized numerous activities, to commemorate the 120th birthday anniversary of Ts’ai yüan-p’ei, including exhibition of his life story, lectures, memorial ceremony at the tomb, etc. The two children of Ts’ai in the mainland: Ts’ai Huai-ssu and Ts’ai Ts’ui-ang, as well as Ting Shih-sun, then president of Peking University, came to Hong Kong to attend the activities.

Ts’ai Ts’ui-ang was interviewed by the author, she minced no words that after 1949, the name of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei and the family members were unjustly treated. Only until the 80s, with the opening up of mainland China, was the reputation of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei reclaimed. Since then, now and again, there are proposals to relocate the tomb to mainland China, but Ts’ai Tsui-ang made it clear then, that she and her family believed it to be unnecessary.

News coverage on 20th October 1986 by China Times in Taiwan, of the Autumn memorial ceremony organized by the Alumni Association of the National Peking University in Hong Kong

In time the alumni of Peking University dwindled with age, and some immigrated overseas. After 1987, there was no more news in Hong Kong newspapers regarding the Alumni Association. Whilst another new organization related to Peking University, Peking University Hong Kong Alumni Association, was established in January 1989 in Hong Kong. This is mainly for alumni of Peking University who graduated after 1949. According to the introduction on its website, every year before or after Ch’ing-ming Festival, a trip to the tomb is organized.

Despite the fact that descendants of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei have no intention to relocate the tomb, murmurings of relocation was uninterrupted. The former chief editor of New Evening Newspaper, Lo Fu 30, is one of the active advocates of relocation. From 1985, he repeatedly wrote articles to advocate relocating the Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei tomb to the grounds of Peking University, and to build a larger tomb. He has never received official response from mainland government.

In his article About the Tomb of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei 31, Lo Fu indicated: The well known translator Professor Wu Ning-k’un was visiting the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 1994, after learning that the tomb of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei was in Hong Kong, he considered the vistas bleak, and wrote a letter to Peking University, with lines “I sincerely beseech my alma mater to welcome back the soul of Mr. Ts’ai Ch’ieh-min, to be buried in the grounds of Peking University, for generations of students to pay tribute. If there is shortage of funding, alumni can be asked to contribute, I myself should certainly be the first……” In this instance, the president’s office of Peking University responded with a letter.

Lo Fu read a copy of the letter, in his article About the Tomb of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, he quoted part of the content: “The current grounds of Peking University was the grounds of the former Yenching University, in 1952 after adjustments of the higher education institutions, Peking University was relocated from the beach to the current address. The main quarter of the University was designated Cultural Heritage Protection Area under Beijing City Government in March 1994, in the Cultural Heritage Protection Area, the original layout must be preserved, any renovation or new built projects, must adhere to the regulations of Cultural Heritage Protection and be approved before proceeding, the University does not have authority for construction. For the quarter not designated as Cultural Heritage Protection Area, such as student dormitory, canteen, sports centre, the spaces in between buildings are very narrow, and noises are loud, they are not appropriate locations for the burial of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei.”

This reply from the Peking University was indeed most plain, but the hometown of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, Shao-hsing of Chekiang province, was actively cajoling to undertake a spectacular burial. The voices for and against the northern relocation of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei tomb was still unending. The granddaughter of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei , Ts’ai Lei-k’ei, who is a lecturer at Peking University, again made it clear on her tomb sweeping trip to Hong Kong in November 2011: “In that turbulent era, wherever my grandfather was buried, he was buried for peace of mind. My grandmother lived in Shanghai and she was buried in Shanghai. We hope that he can have a serene environment, we do not want great disturbance to the tomb. Relocating the tomb is a disturbance. On the other hand, relocating the tomb will spend human resource, material resource and monetary resource. For my grandfather, this is not the style of his action and conduct. For us descendants, it is possible that we do not need this change.”32

On 7th September 1935, T’sai Yüan-p’ei spoke at the founding meeting of the academic senate of Academia Sinica

In 2018, on the 150th birthday anniversary of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, Ts’ai Lei-k’ei spoke to journalists in front of the tomb: “ My grandfather was steeped in classical studies, and he was erudite in new learnings. Today when we recall his achievements and his spirit, the intention is to carry forward his purposes, to strive for the prosperity and vigour of the Chinese race.” From the media reportings of her visit to Hong Kong this time, the relocation of the tomb was not a talking point anymore, in the reported conversations of the son and granddaughter there was no mention of it neither.

Although the dispute has settled, calamity suddenly swooped in! The Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei tomb was located in a peaceful corner of Hong Kong, yet it still encountered a “minor purge”. If it were relocated to the mainland, in the ten years catastrophe of the Cultural Revolution, it would certainly have been “eradicated”. It is unbearable to ponder.

Remembering Chung Jung-kuang 33, the first Chinese president of Lingnan University in Kuang-chou, after he passed away in Hong Kong in 1942, he was buried at the Aberdeen Chinese Permanent Cemetery. However, the alumni of Lingnan University followed the instructions of his will, and relocated his coffin to the grounds of Lingnan University in Kuang-chou. Eventually, Lingnan University disappeared, the Chung tomb likewise could not be retained, during the Cultural Revolution, it was greatly damaged, the corpse and tombstone could no longer be found.

In comparison, the Ts’ai tomb that has “stubbornly hold onto” Hong Kong, is looked after by the alumni of Peking University and those with cultural interests. It not only evaded political calamities, it also acquired a new appearance, and became a deeply meaningful cultural icon. Hong Kong is fortuitous to bury this loyal skeleton, is it not fortuitous for Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei to be buried in this “safe haven” of Hong Kong?

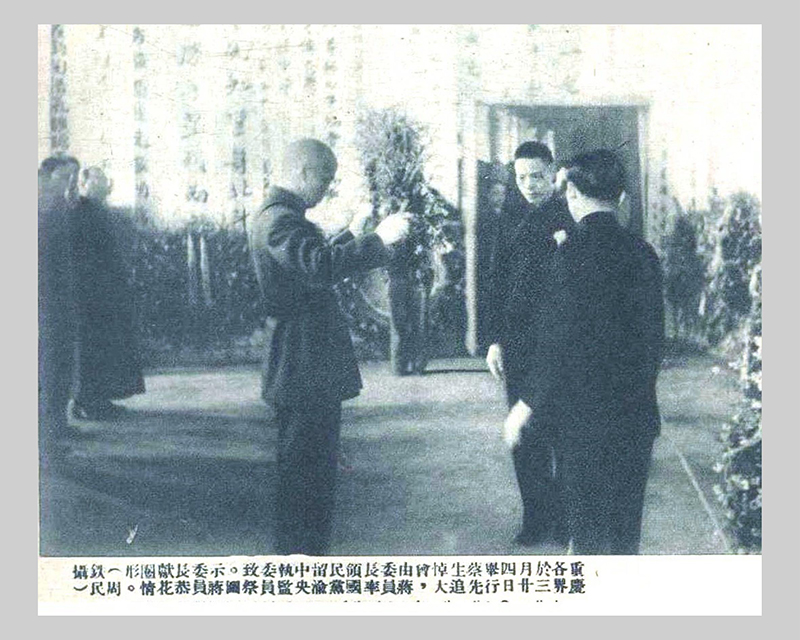

On 24th March 1940, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek was the guest of honour at the memorial ceremony in Chung-ch’ing. Photograph courtesy Chung-hua t’u-hua Magazine

In the April 1940 issue of Chung-hua tz’u-hua Magazine, there is an English coverage of the memorial ceremony

1. Aberdeen Chinese Permanent Cemetery is located on the hill side in the south western corner of Hong Kong Island. It is surrounded by hills on three sides, facing the sea on the other side. In 1913 the land was assigned by the government to Hong Kong Chinese to develop a cemetery for Chinese. It began operation in 1915, and is also named Aberdeen Chinese Cemetery, or Aberdeen Cemetery.

2. Shan-yin county of Chekiang province was first established in the Ch’in dynasty (221-206 BC.) It was located in the north of Hui-chi Shan (mountain), hence the name with the word Shan. Since late Ch’ing, the county had been rezoned under different administration district. It is now under the administration of the city of Shao-hsing, and Shan-yin no longer exists.

3. “Utter despair and devoid of tears” is the original phrase used by the mainland netizen.

4. According to the 11th March 1940 edition of Hong Kong Ta-kung Pao, the fourteen pallbearers were: Lo Ming-yu, Ch’en Liang-yu, Hu Ch’un-ping, Su I, Chin Ch’eng-fu, Wu Fan-huan, Lo Shao-chai, Yü T’ien-min, Ch’en Cheng, Li Shao-ch’ing, Tseng Ju-pai, Chung Yen-lin, Fu K’ung-lin and Huang T’ieh-cheng.

5. The Alumni Association of the National Peking University in Hong Kong was established in 1940, also known as the Hong Kong Alumni Association of the National Peking University.

6. Yeh Kung-ch’o (1881-1968), tzu Yü-fu, Yü-hu, hao Hsia-an, native of P’an-yü, Kwangtung province. He graduated from the former incarnation of Peking University, the Imperial University of Peking. He later studied in Japan. In the early years of the Republic, he was appointed minister of transportation. He was a well known politician, calligrapher, painter and collector.

7. Hsia-an hui-kao (遐菴彙稿), with supplement of the Chronological Record of Yeh Kung-ch’o. Published by Wen Hai Press Company of Taipei in 1968.

8. Texts of these two letters were compiled into The Complete Works of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, published by the Commercial Press of Taipei in 1968.

9. Yü T’ien-min (1891-1969), native of Lin-hsiang, Hunan province. He graduated from the Law Department of Peking University in 1910, in the following year, he enrolled at the Research Institute of the Tokyo Imperial University in Japan, and studied law there for six years. After returning to China, he assisted Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei in administration affairs. He was editor of the Three Principles of the People Series and professor at New Asia College. In 1950 he left for Taiwan, he was appointed division head of the criminal division of the Ministry of Justice, chief secretary of National Chengchi University, member of legal affairs committee of the Examination Yuan. He published A Summary of International Law (國際公法要義).

10. Huang Lin-shu (1893-1997), original name Lin-hsiang, tzu Lin-shu, hao Lu-yüan, native of Lung-ch’uan, Kwangtung province. He graduated from the Economics Department of Tokyo Central University, and taught at a secondary school after returning to China. Between 1930s and 1940s, he was consecutively appointed committee member of the Kwangtung provincial government, director of Construction Department and director of Education Department. He founded eight provincial schools, Hong Kong Tak Ming Secondary School, Kuang-chou Chu Hai Secondary School, etc. In 1947, he was the first president of Kuang-chou Chu Hai University. In 1948, after the implementation of the Constitution of the Republic of China, he was the first term legislator of the Legislative Yuan. Later he was appointed the first term committee member of the Examination Yuan, and he continued in this posting till the fourth term. In 1949, he left mainland China to Hong Kong, Chu Hai University also moved to Hong Kong, due to regulatory restrictions regarding education in Hong Kong, Chu Hai University changed its name to Ch’u Hai College. He continued his executive role at Chu Hai College. He was chairman of the Hong Kong Chinese Culture Association, and founded the Hong Kong Chung-shan Library. His works include A Revised Study of the Great Wall of the Ch’in Emperor (秦皇長城修正稿).

11. Wang Yün-wu (1888-1979), native of Hsiang-shan, Kwangtung province, but born in Shanghai. He was self educated, in 1920s and 1930s he worked at the Commercial Press. After the Sino-Japanese War, he was appointed economic minister and finance minister. In 1949, he left for Taiwan, and was appointed committee member of the Design Council of the Executive Yuan, vice president of the Examination Yuan and vice president of the Executive Yuan.

12. The February 1963 issue of Ch’uan-chi wen-hsueh (傳記文學)

13. Chou Chün (1890-1975), also named Chou Yang-hao, the third wife of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei.

14. Yü Yu-sun (1890-1965), native of Fu-ling, Szechuan province. He graduated from the Philosophy Department of Peking University, then studied at the Tokyo Imperial University in Japan. He was professor at the Peking Kuo-min University, Szechuan University, Chungking University, as well as dean of general affairs at Chungking University. In 1949, he left mainland China for Taiwan, and was appointed professor at the National Taiwan University, director of the History Department, and in charge of the Modern Chinese History and American History Center. He published An Outline of the General History of China (中國通史綱要).

15. The 18th April 1959 edition of Free Man (自由人) in Hong Kong.

16. Lu Wei-luan (1939 b.), pseudonym Hsiao-ssu, native of P’an-yü, Kwangtung Province. She was brought up in Hong Kong, a well known prose writer and educationist. She graduated from the Chinese Department of New Asia College, Chinese University of Hong Kong, and attained the master degree in Chinese philosophy. She is the former director of Research Center for Literature at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She retired in 2002, and was granted Life Time Achievement Award by the Hong Kong Arts Developement Council. Her works include A Stroll in Hong Kong Literature (香港文學散步).

17. Chou Ts’e-tsung (1916-2007), native of Ch’i-yang, Hunan province. Well known historian, redologist and poet. He was director and professor at the Center for East Asian Studies of the University of Wisconsin, he was consecutively professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, National Singapore University, guest professor at Stanford University and visiting professor at the Institute of Chinese Literature and Philosophy of Academia Sinica. His 1960 Harvard University Press publication of The May Fourth Movement: Intellectual Revolution in Modern China is the first in depth study of the May Fourth Movement in the English language.

18. Yü Kuang-chung (1928-2017), native of Ch’ üan-chou, Fukien province, but born in Nanking. He studied at the University of Nanking and the University of Hsia-men. In 1950 he left with his parents to Taiwan, and graduated from the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures of the National Taiwan University, and became active in the literary circle of Taiwan. In 1958 he furthered his studies in the United States, and attained the master degree from the University of Iowa. He taught at National Taiwan Normal University, National Taiwan University, National Chengchi University, Western Michigan University, Chinese University of Hong Kong. In 1985, he moved from Hong Kong to Kaohsiung, Taiwan. He was appointed president at the College of Liberal Arts of National Sun Yat-sen University. In 2003 he was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Letters by the Chinese University of Hong Kong. His works include poetry, prose, criticisms and translations that amount to scores.

19. Huang Kuo-pin (1946 b.), well known poet and scholar in Hong Kong. In 1971 he graduated from the School of English of the University of Hong Kong. In 1992 he attained the doctorate degree from the Department of East Asian Studies of the University of Toronto. He taught at the School of English and the Department of Comparative Literature of the University of Hong Kong, Department of Translation of Lingnan University, and Department of Languages, Literatures and Linguistics of York University, Canada. Before his retirement, he was appointed professor at the Department of Translation, Chinese University of Hong Kong. He now mostly lives in Canada. His works include poetry, criticisms and translations that amount to scores.

20. Chin Yao-chi (1935 b.), native of T’ien-t’ai, Chekiang province. He graduated from the National Taiwan University, attained his master degree at the National Chengchi University, and the doctorate degree at the University of Pittsburgh. He is the former president of New Asia College, Chinese University of Hong Kong, and president of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He retired in 2004. His article on the new tombstone of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei was published in the 11th June 1978 edition of China Times, and compiled into his works The Concept of University (大學之理念,published by China Times) Publishing Company in Taipei in 1983.

21. Teacher of a Generation-Biography of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei by Huang Chao-heng, published by Modern China Publishing in 1982 in Taiwan.

22. Chuang Yen (1899-1980), tzu Shang-yen, hao Mu-ling, native of Wu-Chin, Kiangsu province. In 1924 he graduated from the Philosophy Department of Peking University, and enrolled in the Research Center of Chinese Studies at Peking University. He was recommended to join the Ch’ing Palace Reparations Committee ( the former incarnation of the Palace Museum) as clerical staff, in charge of cataloguing the cultural artefacts in the Palace. In 1925, he was officially employed in the antiquities department of the Palace Museum. In 1928, he was recommended to study archaeology at the Tokyo Imperial University. In 1930 he was recruited by the National Peking University and returned to China, to join archaeological work in Hopeh. In 1935 he was promoted to section chief of the first section of the antiquities department at the Palace Museum. In 1935 he escorted the cultural artefacts from the Palace to traveling exhibitions in Europe and America. In 1937, after the out break of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, he again escorted the cultural artefacts retreating inland with the government. In December 1948, he escorted the cultural artefacts from the Nanking Branch of the Palace Museum to Taiwan. In 1964, he was promoted to deputy director of the National Palace Museum. After retirement in 1969, he joined the College of Arts of the Chinese Culture University as director. He was a specialist in antiquities, calligraphy and painting, an educationist in the arts, and a calligrapher himself who specialized in slender-gold-style.

23. Ho Kuang-yen (1940 b.), tzu Shuo-t’ang, hao Hung-chai, native of Ho-Shan, Kwangtung province, but born in Hong Kong. He attained his doctorate degree at New Asia College, and had been a professor at the Centre for Chinese Literature and History of Chu Hai College, Department of Chinese Language and Literature of Hong Kong Shue Yan University, director of the Graduate Institute of Asian Humanities of Huafan University in Taiwan. He is currently professor at New Asia Institute of Advanced Chinese Studies. His works include A study of Li Ch’ing-chao (李清照研究), A Study of the Life and Works of Ch’en Chen-sun (陳振孫之生平及其著述研究), Proof Reading and Commentary of An Anthology of Delightful Sung Tz’u (宋詞賞心錄校評).

24. Wang Shao-sheng (1904-1998), tzu Huai-ping, native of Feng-shun, Kwangtung province. In 1936 he enrolled in the Chinese Department of Peking Normal University, and graduated from the Chinese Department of the National Peking University. He taught consecutively at the National Sun Yat-sen University, Lingnan University, Kwangchou University, Kuo Min University. In 1949 he left for Hong Kong, and taught at Kwang Ta College, Kwang Ch’iao College, Chung Chi College of Chinese University of Hong Kong. In September 1971 he was professor at the Research Institute of Chinese Literature and History of Ch’u Hai College, and became director there in 1979. He also taught at Hong Kong Baptist College, New Asia Institute of Advanced Chinese Studies, and retired in 1989. He was a classicist and excelled in poetry, tz’u poetry and rhythmical prose. His works include Overview of Chinese Studies (國學概要), Essays of Huai-ping (懷冰隨筆), Collected Works of Huai-ping Shih (懷冰室集).

25. According to the Chronological Record of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei written by Ts’ai himself, and published in the 4th issue 1987 of the seasonal magazine Archive and History in Shanghai, the name of his father was Yao-shan (曜山), not I-shan (嶧山) as written in the epitaph.

26. The dating of 13th year of the Republic in the epitaph was erroneous. According to the many researches on the life of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, it should be 12th year of the Republic, 1923 of the Gregorian calendar. In July 1923 Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei left China with his family, and returned from Europe in 1926. Refer to the Chronological Record of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei compiled by Wang Shih-ju, published by Peking University Publishing in 1998.

27. Ts’ai Wei-lien (1904-1939) was the daughter of the second wife of Ts’ai Yüan-p’ei, Huang Chung-yü. She was a painter and taught at Hang-chou National Art Academy. In 1938 she moved to K’un-Ming with the husband and five children. In May 1939, she died at childbirth.

28. 10th January 1987 edition of China Times Newspaper.

29. 8th November 1987 edition of Overseas Chinese Daily News.

30. Lo Fu (1921-2014), original name Lo Ch’eng-hsün, native of Kuei-lin, member of the Communist Party. Since 1941, he worked at Ta Kung Pao Newspaper in Kuei-lin, Chung-ch’ing and Hong Kong. He was sent to work at Hong Kong Ta Kung Pao in 1948, as editor and deputy editor-in-chief. In 1950, Ta Kung Pao founded another newspaper, New Evening Newspaper. He was also in charge of political propaganda in Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan. In 1982, he was arrested in Peking for “espionage”, confined for ten years, and released in 1993. He returned to Hong Kong and in 1997 immigrated to the United States, after five years, he settled in Hong Kong.

31. Wen-wan pin-fen (文宛繽紛) by Lo Fu, published by Cosmos Books in 2007 in Hong Kong.

32. The 10th December 2011 edition of Yang-ch’eng Evening News in Kwang-chou.

33. Chung Jung-kuang (1866-1942), native of Hsiang-shan, Kwangtung province. His original name was Chung Hsing-k’ei. After being converted to Christianity, he changed his name to Jung-kuang. He took the civil service examination and attained the chü-jen ranking. In 1899 he was the head teacher of Chinese at the Mansfield College in Kwang-chou and began to learn English. He joined the revolutionary organizations Hsin-chung Hui and Tung-meng Hui. He also co-founded Po-wen Pao Newspaper and K’ei Pao Newspaper. In the early years of the Republic, he was director of education at the Kwangtung Government Office and counselor of Kwangtung Government. In 1927, he was the first Chinese president of Lingnan University, and in a period of ten years, realized many notable accomplishments. After retirement, he was appointed councilor of the National Political Council. He passed away in Hong Kong in 1942.

On 11th January 1968, the president of Academia Sinica Wang Shih-chieh and family members of T’sai Yüan-p’ei officially unveiled the T’sai Yüan-p’ei statue at Academia Sinica. 11th January is also the birthday of T’sai Yüan-p’ei