In 1861, President Lincoln appointed Anson Burlingame the United States Minister to China. In 1867, the Tsungli Yamen (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) of the Ch'ing Court in turn appointed him Envoy to the Treaty Nations. Burlingame’s extraordinary career has become a fabled story in diplomacy. During his posting in China, Burlingame acted to uphold fair play, he safeguarded the interests of China, and won the appreciation and trust of the Ch'ing government. In 1868, China and the United States signed the Additional Articles to the Treaty between China and the United States, of the 18th of June 1858. It offered remedial measures to the unequal treaty articles of 1858. This treaty is also known as the Burlingame Treaty, and with other treaties signed in late Ch’ing, are now in safekeeping at the National Palace Museum of the Republic of China. Seventy years after Burlingame’s appointment as Envoy to the Treaty Nations, in the 26th year of the Republic (1937), the Sino Japanese war broke out. Within a few year, the United States became an ally of the Republic of China. Friendship between the two nations indeed originated with Anson Burlingame.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

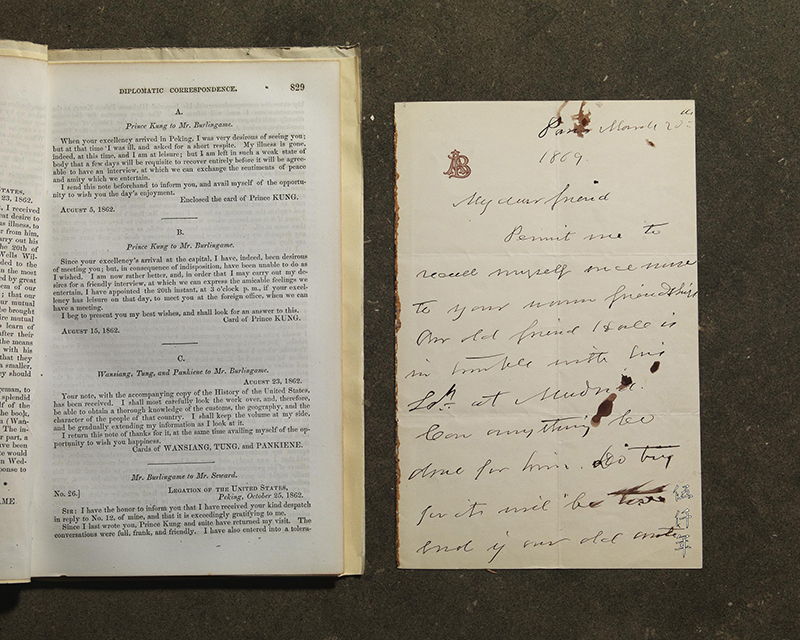

Letter by Anson Burlingame

On 27th October ting-mao year of the Chinese calender, in the 6th year of the T’ung-chih reign, the equivalent of 22nd November 1867 according to the Gregorian calender, Prince Kung, I-hsin, of the Tsungli Yamen sent a letter to the embassies of the treaty nations, informing them that the former United States minister, Anson Burlingame, had been appointed by the Imperial Court to be the first Chinese envoy to the treaty nations.

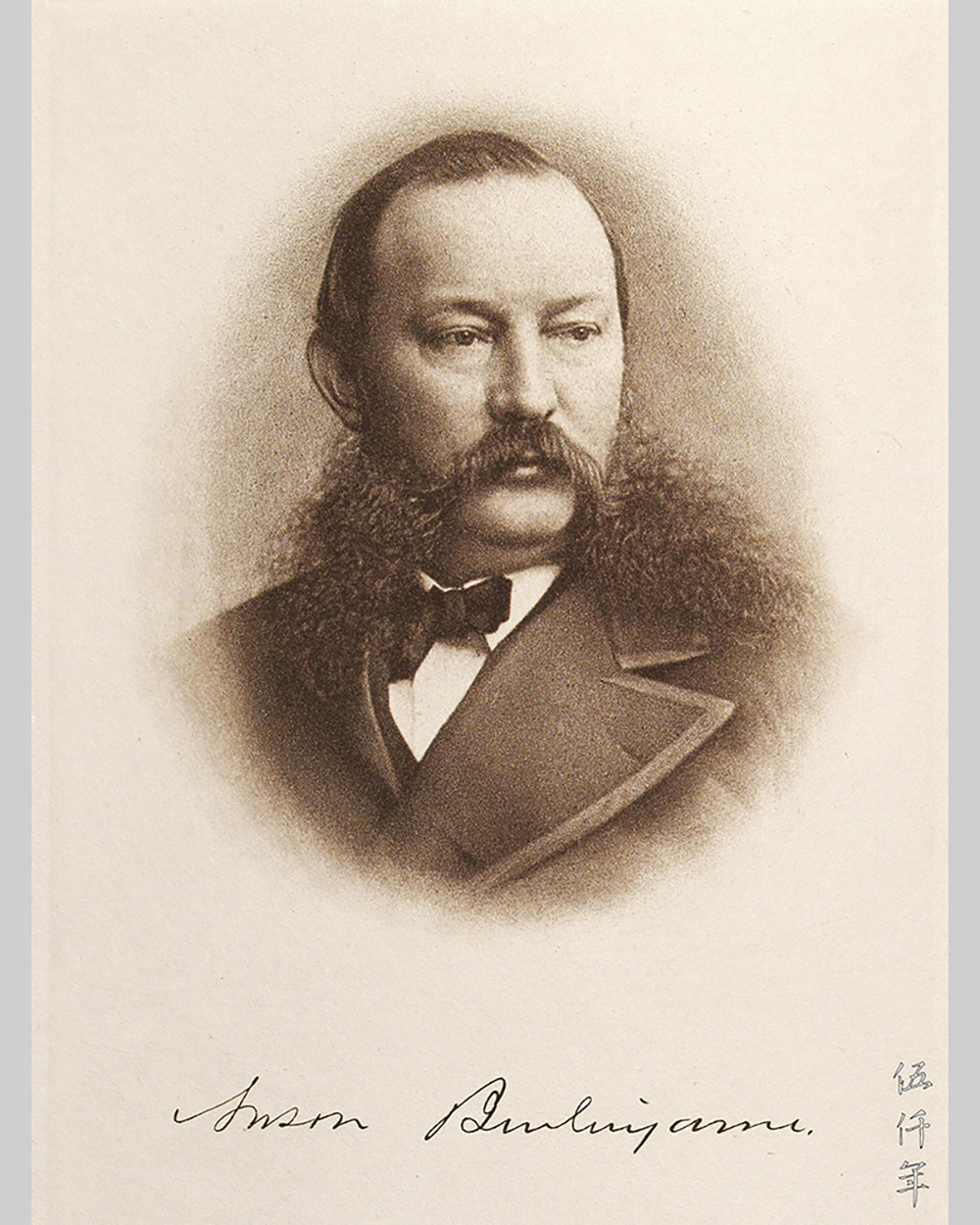

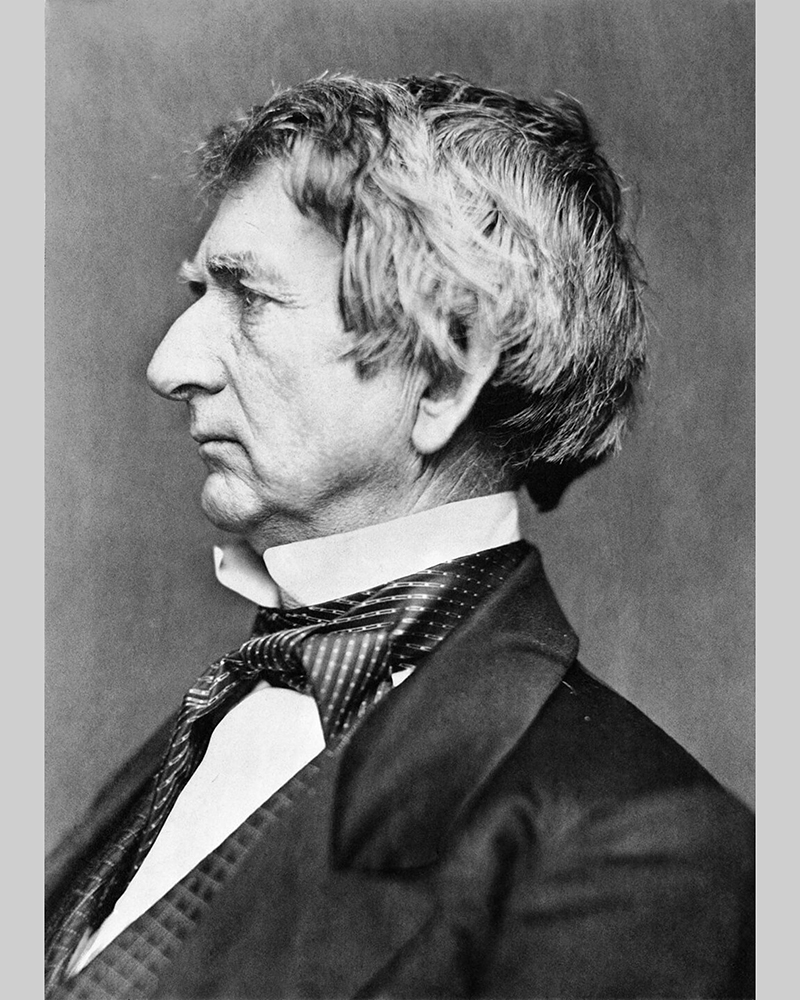

Portrait of Anson Burlingame

The Ch’ing court had never appointed an envoy before. The Tsungli Yamen, known as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in modern terminology, was only established on 1st February in the 11th year of the Hsien-feng reign, the equivalent of 11th March 1861 of the Gregorian calender. It originated from China’s defeat in the Second Opium War in the 8th year of the Hsien-feng reign (1858), concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Tientsin. In the Treaty, it was stipulated that Britain and France were entitled to set up embassies in Peking. By September, the 10th year of the Hsien-feng reign, October 1860 of the Gregorian calender, British and French forces sacked Peking, the Convension of Peking was signed separately between China and Britain, China and France, China and Russia. The Ch’ing government was coerced to implement the treaties, Tsungli Yamen was established in the aftermath. In the 88th year of the Republic of China (1999), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of China applied the date of 11th March, the founding of the Tsungli Yamen, to be the anniversary date of the Ministry.

Tsungli Yamen in Peking, 1878. Photograph courtesy University of Bristol Library

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of China. Photograph courtesy Mr. Ch’iu Te-hsiang

The appointment of Anson Burlingame as envoy of China, was intended to establish an embassy in Washington on his return, to visit European treaty nations and non-treaty nations afterwards, as to explain the difficulties and position of China to the heads of these nations. To be appointed envoy to such a group of nations, was akin to a minister to both the United States and Europe, an unprecedented and unrepeatable position. In a few years, the appointments of ministers became an established custom in the foreign dealings of the Ch’ing court.

Why was it difficult to find a suitable envoy out of the four hundred million Chinese in the Ch’ing dynasty? While instead an American, Anson Burlingame, was particularly favoured?

In the 6th year of the T’ung-chih reign (1867), gazing across the empire, no one in the scholar-official class was knowledgeable in western language, for foreign language was not part of the syllabus in public examination. As virtuous and capable as Kuo Sung-tao (郭嵩燾 1818-1891), when he was appointed minister to Britain in the 1st year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1878), he was handicapped by foreign language, and relied on the English secretary at the embassy, Sir Halliday Macartney, for external translations. By the 4th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1878), when Tseng Chi-tse (曾紀澤 1839-1890) was appointed minister to Britain and France, he was already acquainted with English, but not in a position of fluency.

Group photograph of teachers outside Tungwen College

Tungwen College was established in Peking to train and provide translators for diplomatic service during the reign of Chien-lung emperor, Russian was taught at the time. By the reigns of Tao-kuang and Hsien-feng emperors, there was hardly any student left, it existed in name only. In the 1st year of the T’ung-chih reign (1862), Tungwen College began to teach English, and in the following year, it added classes in French and Russian. To start education courses in haste could hardly resolve pressing needs, besides, the translators from Tungwen College could not be made into suitable candidates for ministers immediately. They were incomparable to the metropolitan graduates of chin-shih in learnings and discernments, who also accumulated wide experiences in officialdom.

Putting aside the language barrier, it was important to possess insights into western nations. In the 6th year of the T’ung-chih reign (1867), searching the four seas for someone in the scholar-official class familiar with the politics, society and people of western nations, was remote and unattainable. The pioneer of western education, Yung Wing (容閎 1828-1912), returned to China in the 5th year of the Hsien-feng reign (1855), almost the only American university graduate in the whole country. At the end of the 2nd year of the T’ung-chih reign (1863), he was recommended to Tseng Kuo-fan (曾國藩 1811-1872), and assigned to purchase machinery from America for the Kiang Nan Arsenal. The distinguished diplomats familiar with western nations who came after, such as Wu Ting-fang (伍廷芳), was born in the 22nd year of the Tao-kuang reign (1842), Hsü Ching-cheng (許景澄), was born in the 25th year of the Tao-kuang reign (1845),, Tcheng Ki-tong (陳季同), was born in the 1st year of the Hsien-feng reign (1851). They were all talented men from another generation.

Portrait of Anson Burlingame

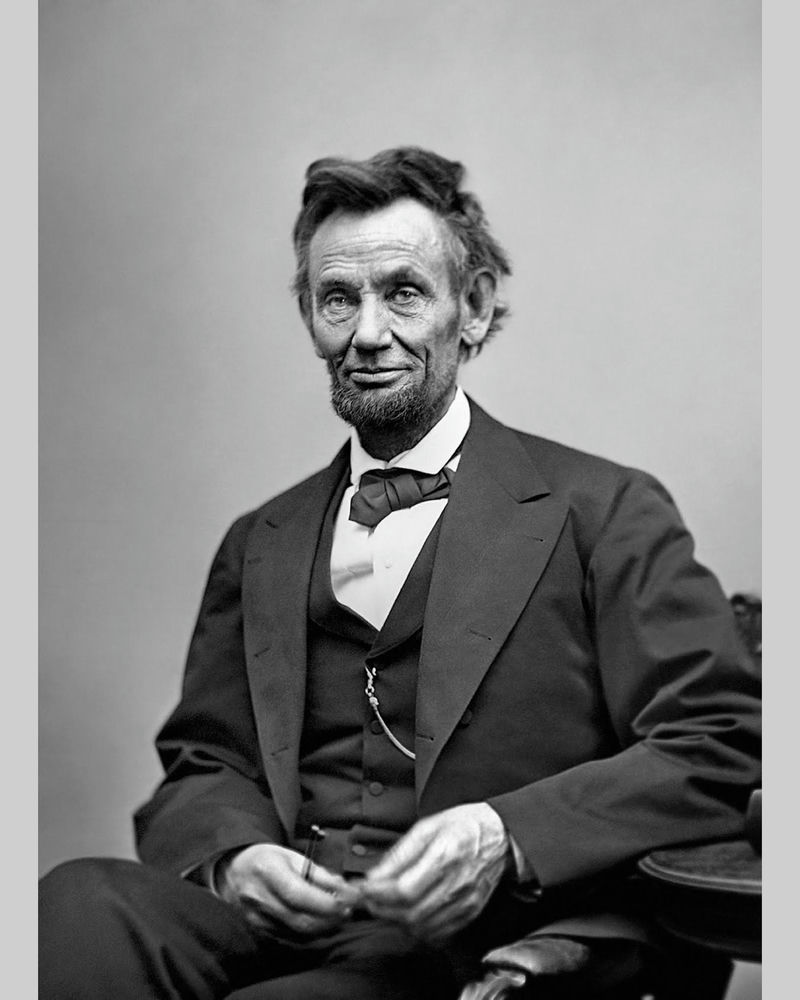

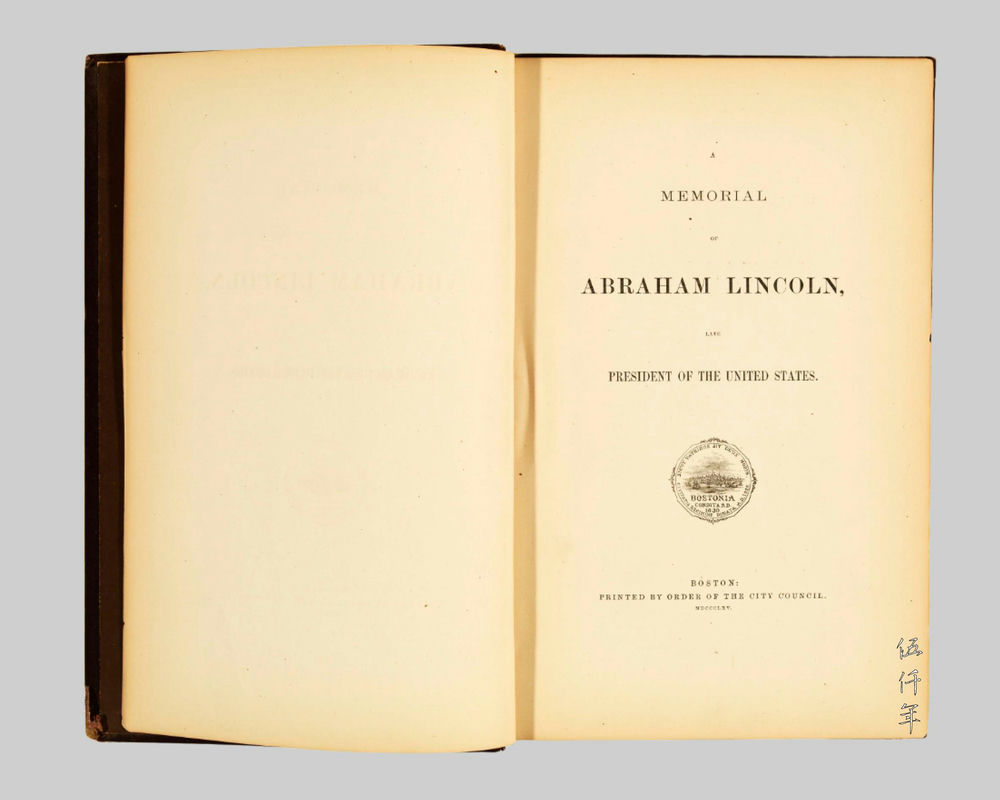

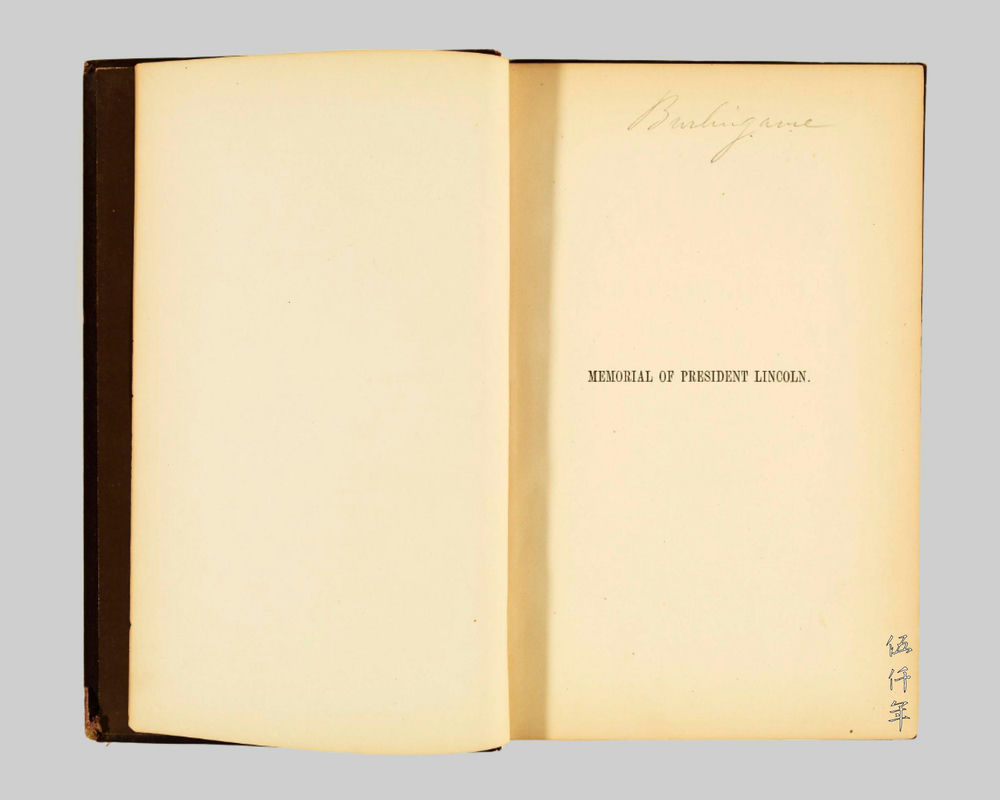

Anson Burlingame (1820-1870) was born in New York, citizen of the United States. His father Joel was a devout Methodist and school teacher. In 1841 he graduated from the Branch University of Michigan, and in 1846 he graduated from Harvard Law School. He practiced law in Massachusetts, and between 1853 to 1854, he was member of the Massachusetts State Senate. From 1855 to 1861, he was elected to three terms as congressman of the House of Representatives. He was best known for his anti slavery position, and an ally of President Abraham Lincoln. He failed in his re-election bid in 1860, and as consolation prize, President Lincoln appointed him minister to Austria in 1861. However because of his previous support of Kossuth and Sardinian independence, the Austrian court objected to his appointment. On 14th June 1861, he was then appointed minister to China. In October Burlingame arrived at the American legation in Macao, the only access to Peking was by river, and the Peiho River was frozen through winter. Not until 20th July 1862 did he finally reach Peking. Before his appointment to China, Burlingame was already a well known political figure in America. His friendship with President Lincoln, in both official and private capacity, was not peripheral. When President Lincoln was assassinated on 15th April 1865, Burlingame was of course sorrowful. There is a copy of the Memorial of President Lincoln signed by Anson Burlingame in my collection. It is a testimony to the relationship that initiated Burlingame’s mission to China.

Portrait of President Abraham Lincoln

Memorial of President Lincoln , former property of Anson Burlingame

Memorial of President Lincoln, signed by Anson Burlingame

In the six years as minister to China, Burlingame frequently acted to safeguard the rights and interests of China. His thoughts were clarified and presented in the 20th June 1863 letter to William H. Seward, Secretary of State. It partially reads:

“In despatch No. 18, of June 2, 1862, I had the honor to write, ‘if the treaty powers could agree among themselves to the neutrality of China, and together secure order in the treaty ports, and give their moral support to that party in China, in favor of order, the interests of humanity would be subserved.’

Upon my arrival at Peking, I at once elaborated my views, and found, upon comparing them with those held by the representatives of England and Russia, that they were in accord with theirs. After mature deliberation, we determined to consult and co-operate upon all questions………

Portrait of William H. Seward

The policy upon which we are agreed is briefly this: that while we claim our treaty right to buy and sell, and hire, in the treaty ports, subject, in respect to our rights of property and person, to the jurisdiction of our own governments, we will not ask for, nor take concessions of, territory in the treaty ports, or in any way interfere with the jurisdiction of the Chinese government over its own people, nor ever menace the territorial integrity of the Chinese empire………”

At a time when the powers were pillaging land and extorting compensations, the high-minded position of Burlingame was like a coal delivery in snow, the Ch’ing court was surprisingly taken with heart felt appreciation. In November 1867, after two terms as minister to China, Burlingame was prepared to return, Tsungli Yamen propositioned him to become China’s envoy. According to contemporary description, Burlingame was modest and sincere, a most courteous man, possessing an outlook that cemented easy friendship with the Chinese scholar officials.

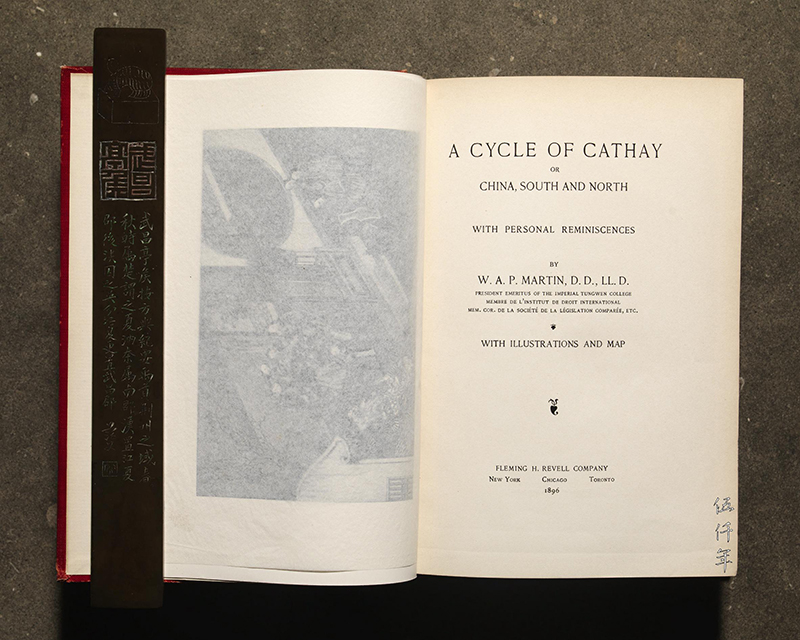

A Cycle of Cathay by W. A. P. Martin

The American missionary and scholar W. A. P. Martin wrote A Cycle of Cathay, which was published in 1896. There is a detailed description:

“Mr. Burlingame, having filled two terms as minister, was about to return to the United States to resume his place in the political movements of the day. Packed for the voyage, he called at the Yamen to take leave of Prince Kung and his colleagues, the prince inviting me to act as interpreter. After professions of regret, which were profuse and sincere on both sides, Mr. Burlingame offered to serve them by correcting misapprehensions.

‘There is a great deal to be done in that line,’ said the prince. ‘Are you going through Europe?’

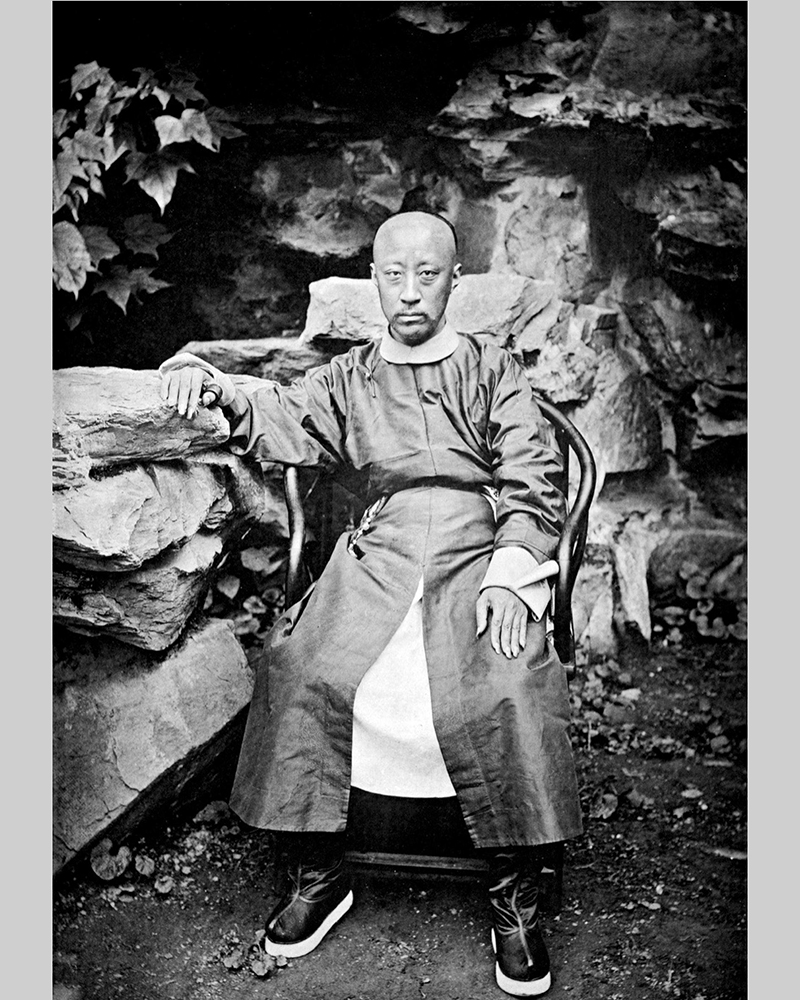

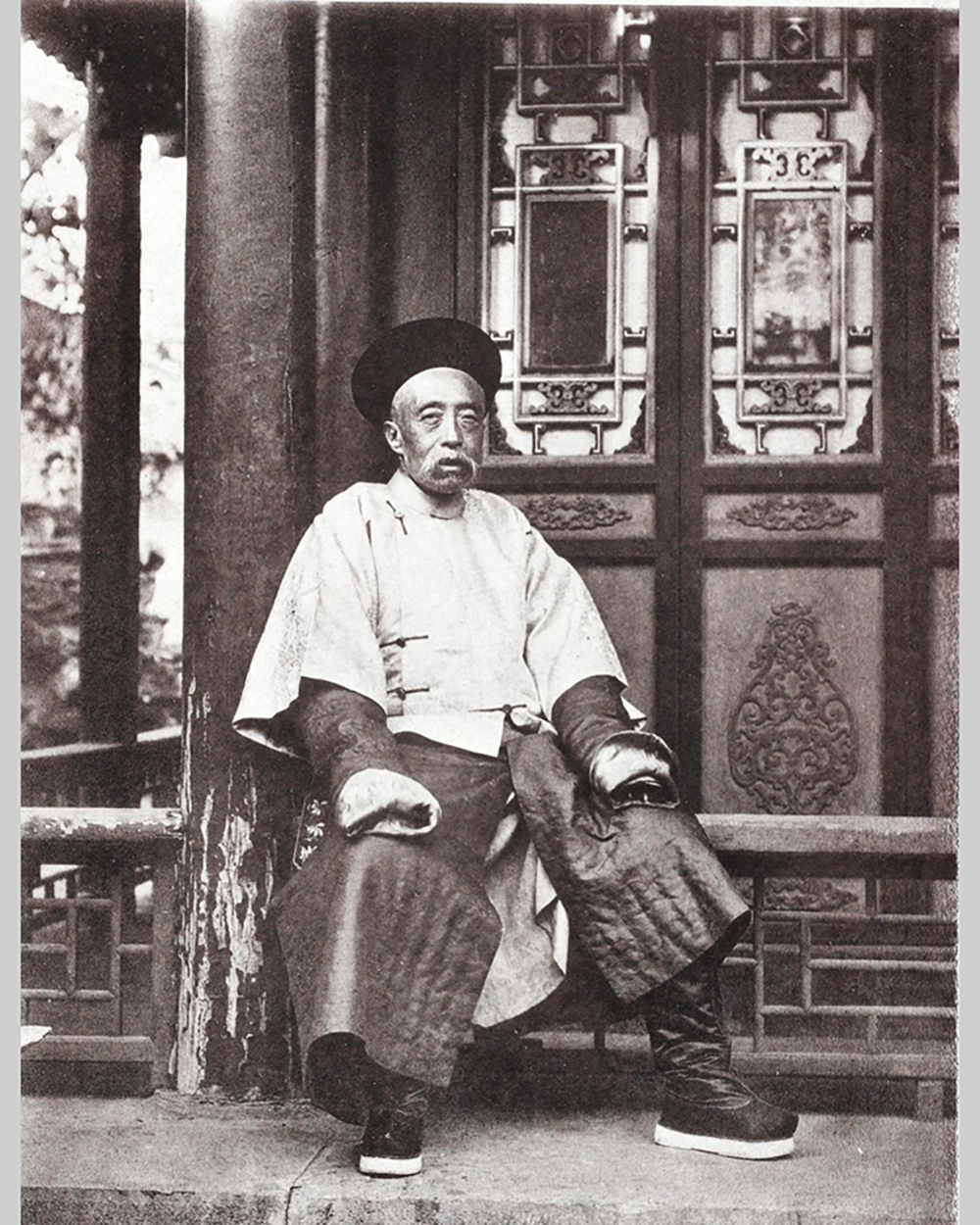

Portrait of Prince Kung, I-hsin

Mr. Burlingame answering in the affirmative, the prince requested his good offices at the courts of Paris and London, especially the latter. Wensiang, always the chief spokesman, enlarged on the nature of the representations to be made, and added: ‘In short, you will be our minister.’

‘If it were possible,’ interposed the prince, ‘for one minister to serve two countries, we should be glad to have you for our envoy.’

This remark, uttered half in jest, was the germ of the Burlingame mission. It struck Burlingame as opening a pleasing vista of possibilities. To a temperament like his the prospect of being the first to introduce the old empire of the East to the courts of the Western world was irresistibly fascinating. It might delay, but might it not help, his political career?”

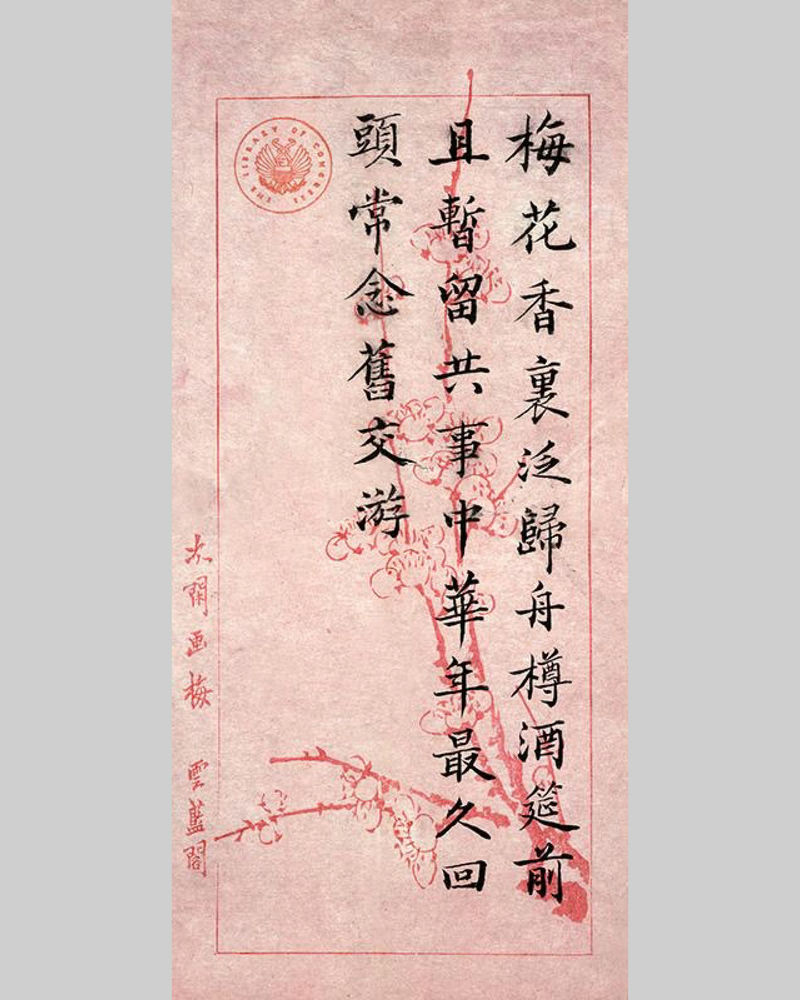

Poem gifted to Anson Burlingame before departing China. Author unknown. Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

In late November 1867, Burlingame arrived at Tientsin, and from there travelled onwards to Shanghai to collect members of the Mission. Those in the Mission were: Chih Kang (志剛), Reserve Customs Circuit; Sun Ch’iao-Ku (孫家谷), Bureau Director at the Ministry of Rites; John McLeavy Brown, British First Secretary, Emile de Champs, French Second Secretary; Te Tsai-ch’u (德在初), T’a Mu-an (塔木菴), T’ing Fu-ch’en (廷輔臣), K’ang Yen-nung (亢硯農), Feng K’uei-chiu (鳳夔九), Lien Ch’un-ch’ing (聯春卿), Kuei Tung-ch’ing (桂冬卿), Chuang Sung-ju (莊松如), etc. Burlingame stayed in Shanghai for nearly a month, together with members of the Mission, they boarded a vessel to America. After one month voyage, in April 1868, they arrived at San Francisco.

Group portrait of members of the Mission of China, published in the Harper’s Weekly, 13 June 1868. Anson Burlingame in the middle of the back row

While in Shanghai, Burlingame wrote to William H Seward, Secretary of State. It partially reads:

“You will have learned from my telegram from Peking of my appointment by the Chinese government as ‘envoy’ to the treaty powers, and of my acceptance of the same. The facts in relation to the appointment are as follows: I was on the point of proceeding to the treaty ports of China to ascertain what changes our citizens desired to have made in the treaties, provided a revision should be determined upon, after which it it was my intention to resign and go home. The knowledge of this intention coming to the Chinese, Prince Kung gave a farewell dinner, at which great regret was expressed at my resolution to leave China, and urgent requests made that I would, like Sir Frederick Bruce, state China’s difficulties, and inform the treaty powers of their sincere desire to be friendly and progressive. This I cheerfully promised to do. During the conversation Wensiang, a leading man of the empire, said, ‘why will you not represent us officially?’ I repulsed the suggestion playfully, and the conversation passed to other topics.

Portrait of Wensiang

Subsequently I was informed that the Chinese were most serious, and a request was made through Mr. Brown, Chinese secretary of the British legation, that I should delay my departure for a few days, until a proposition could be submitted to me. I had no further conversation with them until the proposition was made in form, requesting me to act for them as ambassador to all the treaty ports. I had in the interim thought anxiously upon the subject, and, after consultation with my friends, determined, in the interests of our country and civilization, to accept.”

Members of the Mission of China visiting Niagara Falls, New York. Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

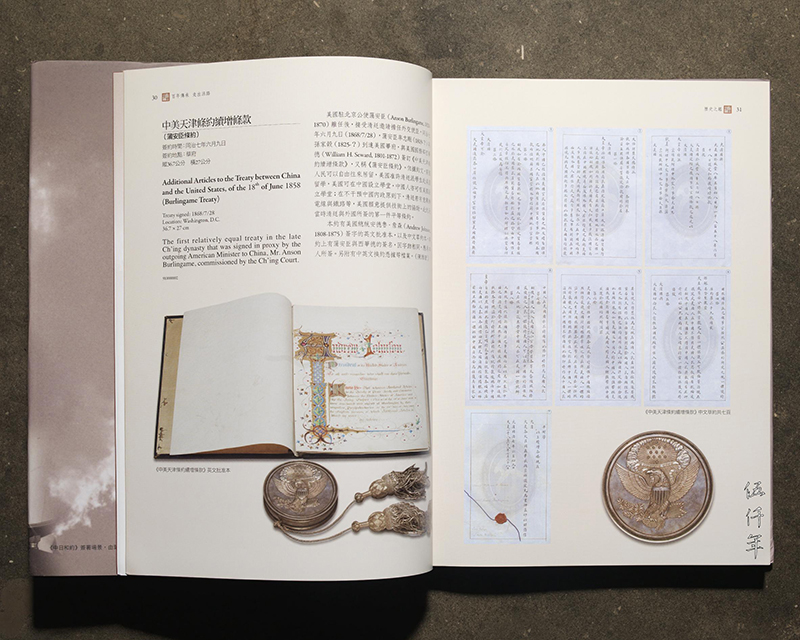

Burlingame was a polished orator. After returning to America, he was able to employ his talent of public speaking in many states, advancing the cause of Chinese diplomacy. On 6th June 1868, the Chinese Mission was received by President Andrew Johnson at the White House. On 28th July, Burlingame on behalf of China, and William H. Seward on behalf of the United States, signed the Additional Articles to the Treaty between China and the United States, of the 18th of June 1858. This treaty is also known as Burlingame Seward Treaty, or Burlingame Treaty, as evidence of his great contribution to this equal treaty. The Treaty between China and the United States, of the 18th of June 1858, referred to the Treaty of Tientsin, the unequal treaty signed after China’s defeat in the Second Opium War. The Additional Articles were remedial measures, ratified in Peking on 23rd November 1869. The principles of the Additional Articles were: 1. Emphasis on China’s territory and jurisdiction, that they should not be interfered. 2. Recognized China’s control over trade and navigation. 3. Recognized China’s right to appoint consuls to American ports. 4. Ensured religious freedom in the two countries. 5. Ensured unrestricted migration between the two countries. 6. Ensured the rights of travel and residence in the two countries. 7. Ensured the right to open schools for own citizens in other country. 8. Ensured the right of China’s emperor to govern without interference. This Treaty is now in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Republic of China. In the 100th year of the Republic of China (2011), Ambassador Shen Lyu-shun and Director Feng Ming-chu edited and compiled the catalogue for A Century of Resilient Tradition, Exhibition of the Republic of China’s Diplomatic Archives. The Burlingame Treaty is illustrated on Page 30.

Catalogue of A Century of Resilient Tradition, Exhibition of the Republic of China’s Diplomatic Archives

Additional Articles to the Treaty between China and the United States, of the 18th of June 1858

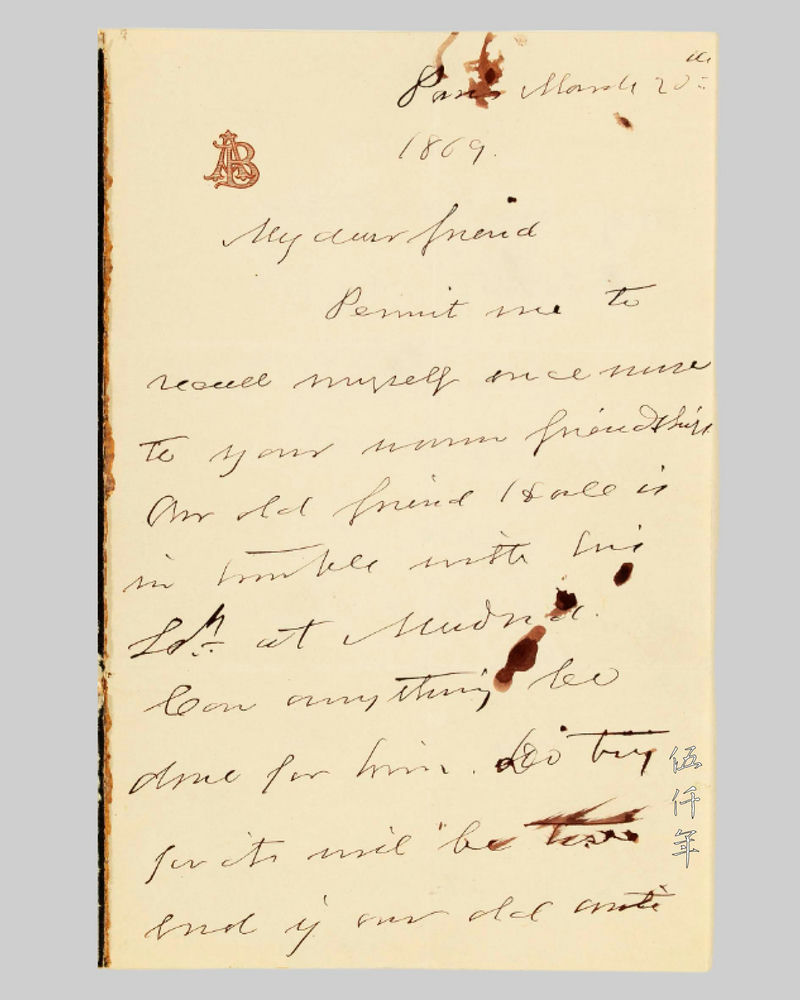

In October 1868, the Chinese Mission arrived in London. On 20th November the Mission was received by Queen Victoria. In January 1869, the Mission reached Paris and stayed till September. In my modest collection, there is a letter by Burlingame dated 20th March from Paris. It reads:

“Paris March 20th

1869

My dear friend,

Permit me to

recall myself once more

to your warm friendship.

Our old friend Hall is

In trouble with

his Lordship at Madrid.

Can anything be

done for him? Do try

for it will be the

end if our old mate

slavery chief should

come to grief through

any misadventures.

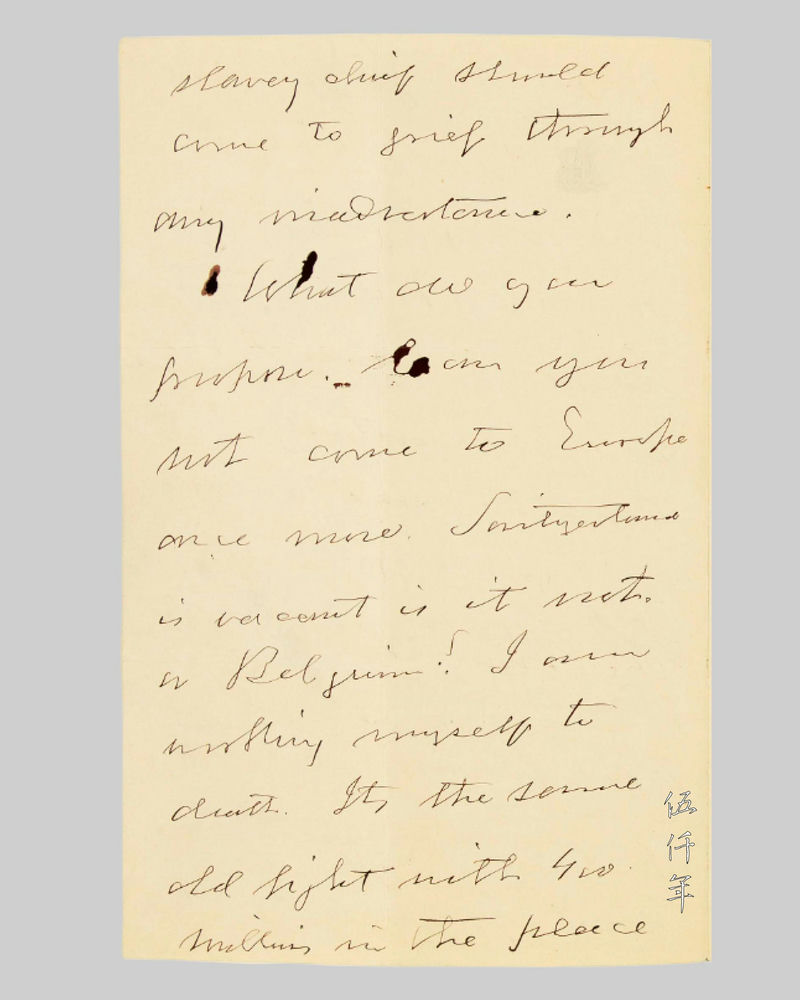

What do you

propose? Can you

not come to Europe

once more? Switzerland

is vacant is it not,

or Belgium? I am

working myself to

death. It’s the same old fight with 400

millions in the place

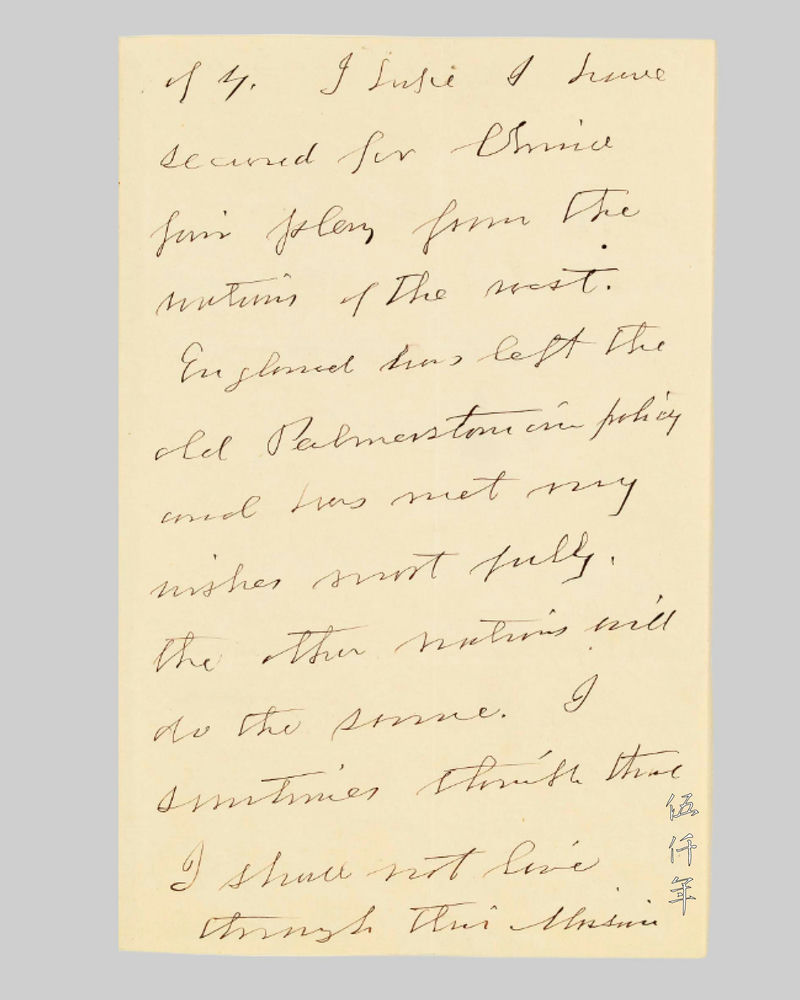

of 4. I hope I have

secured for China

fair play from the nations of the west.

England has left the

old Palmerstonian policy

and has met my

wishes most fully.

The other nations will

do the same. I

sometimes think that

I shall not live

through this mission.

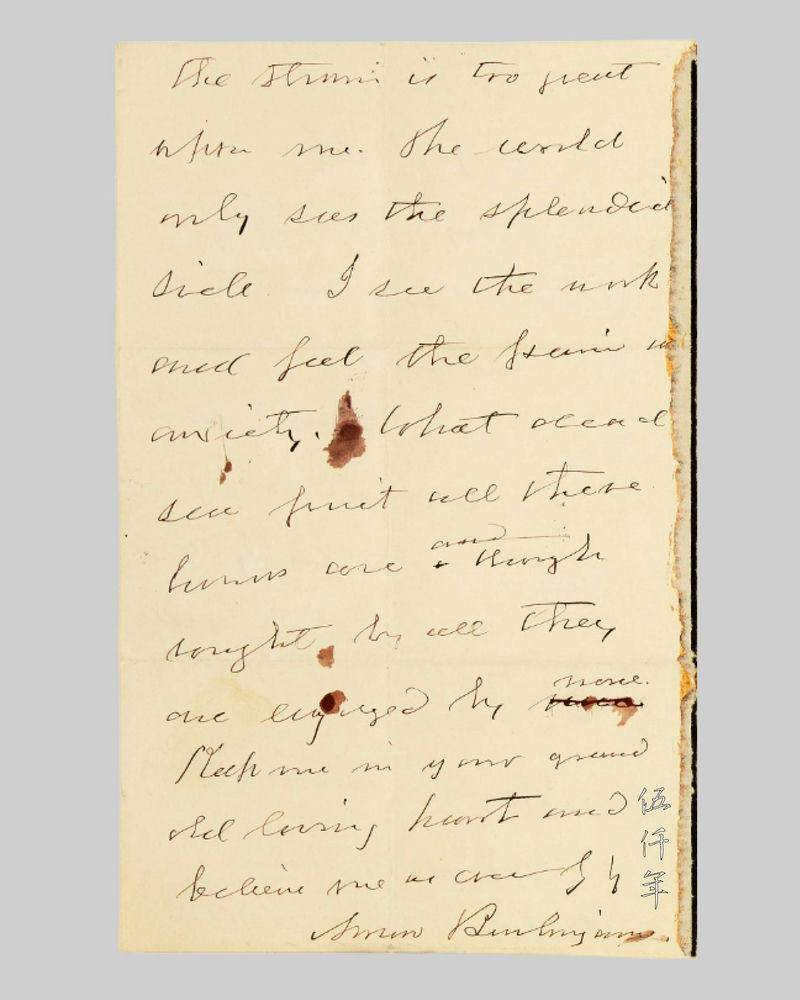

The stress is too great

upon me. The world

only sees the splendid

side. I see the work

and feel the pain and

anxiety. What dead

sea fruit all these

honors are, and though

sought by all they

are enjoyed by none.

Keep me in your grand

old loving heart and

believe me sincerely yours,

Anson Burlingame.”

First page of letter by Anson Burlingame

Second page of letter by Anson Burlingame

Third page of letter by Anson Burlingame

Fourth page of letter by Anson Burlingame

A man from another race, who willingly, for the well being of four hundred million Chinese, persisted to life’s last stretch! In the letter, Burlingame wrote: I sometimes think that I shall not live through this mission. It was indeed a sad prophecy!

The Chinese Mission continued onwards to Sweden, Denmark, Holland, Germany and Russia. On 16th February 1870, the Mission was received by Czar Alexander II. February in Saint Petersburg was particularly cold, one week later, on 23rd, Burlingame died of pneumonia. Accumulative fatigue and apprehensions over China’s affairs, Burlingame passed away in the line of duty. If this tragedy did not befall, perhaps China could have successfully exploited a diplomatic path in dealing with the Foreign Powers.

I shall finally share three books that relate to Anson Burlingame.

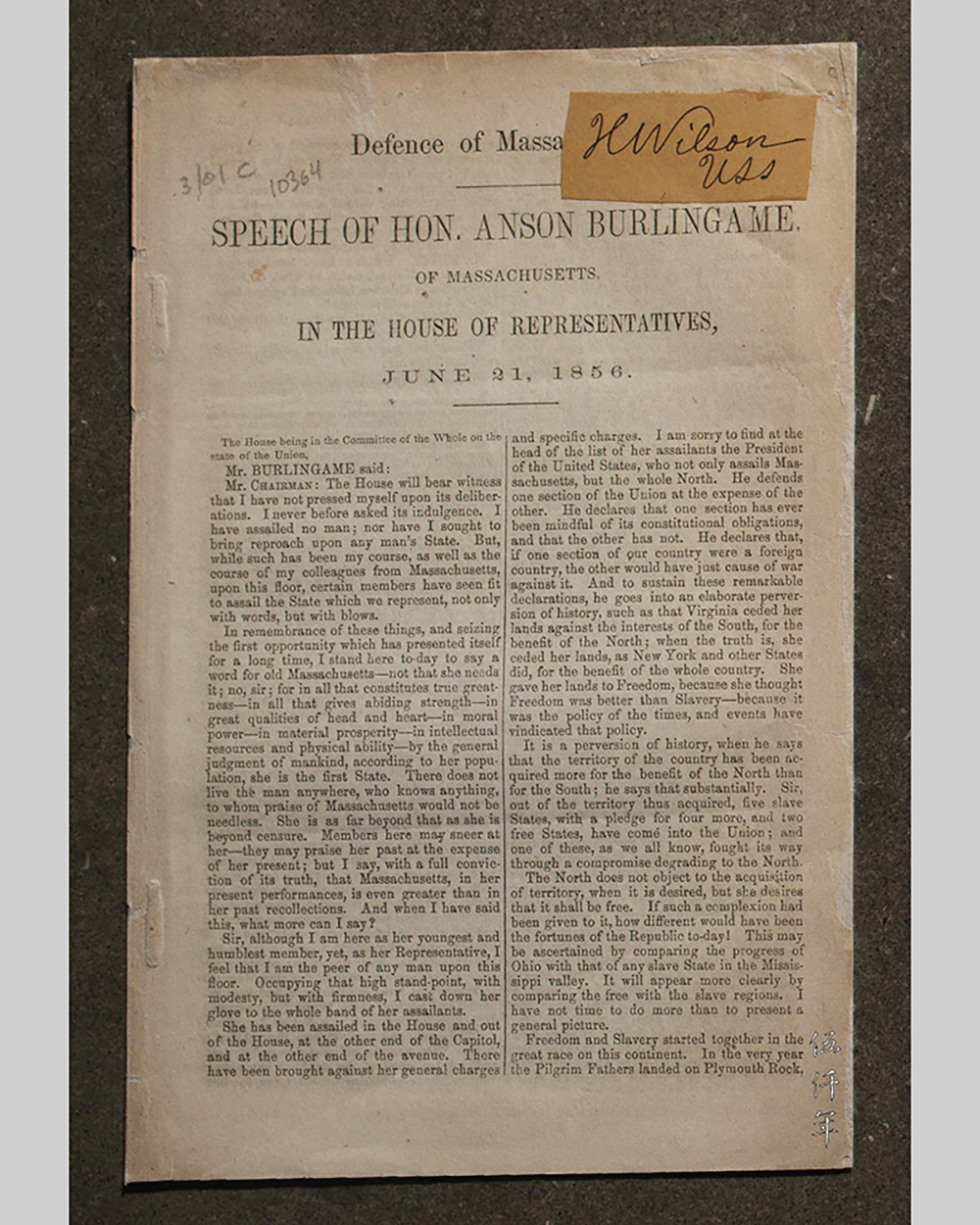

Defense of Massachusetts, Speech of Hon. Anson Burlingame of Massachusetts. June 21, 1856 signed by Senator Henry Wilson

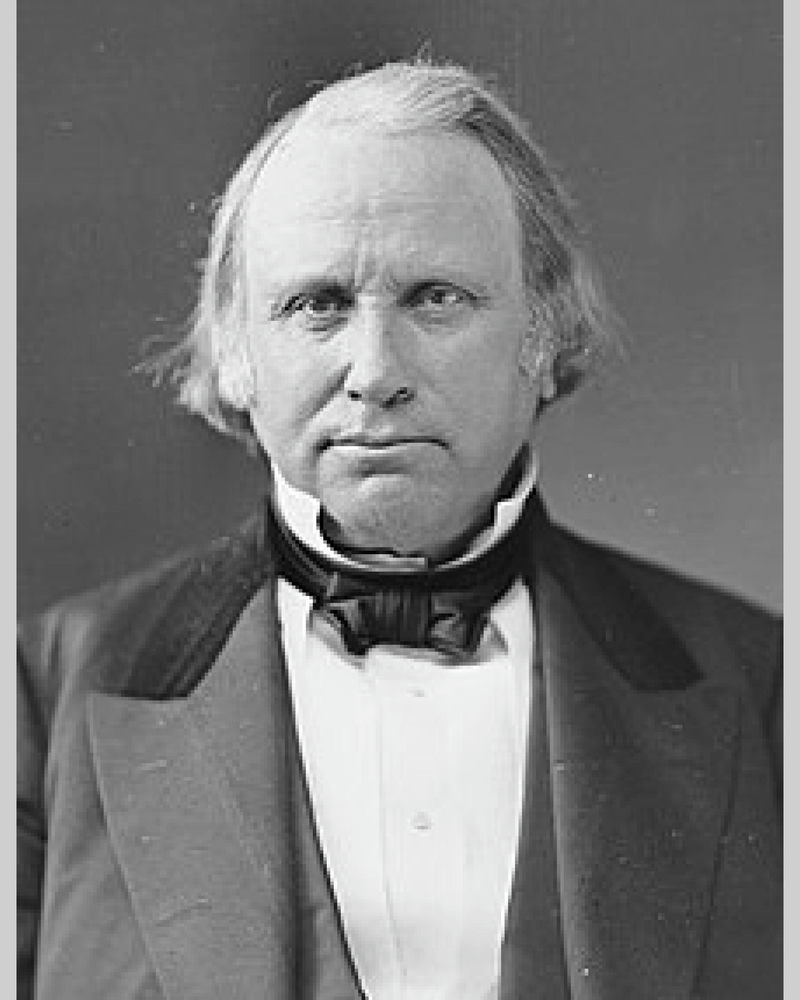

Portrait of Henry Wilson

Defense of Massachusetts, Speech of Hon. Anson Burlingame of Massachusetts. June 21, 1856. This is perhaps the best known speech by Burlingame as a congressman, supporting the anti slavery platform of the north and his friend Senator Charles Sumner, who was gravely assaulted by the southern Congressman Preston Brooks. This special copy was owned and signed by Senator Henry Wilson, political ally of both Sumner and Burlingame, Henry Wilson became Vice-President of the United States in 1873.

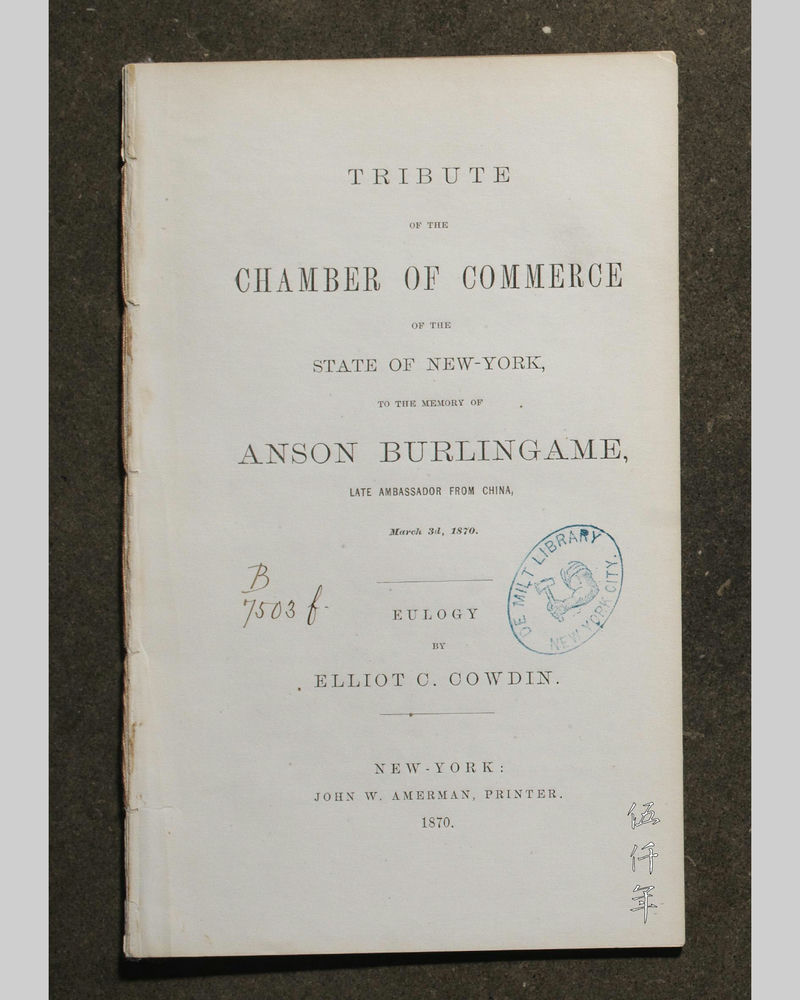

Front cover of Tribute of the Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York, in the Memory of Anson Burlingame, Late Ambassador from China, March 3rd 1870

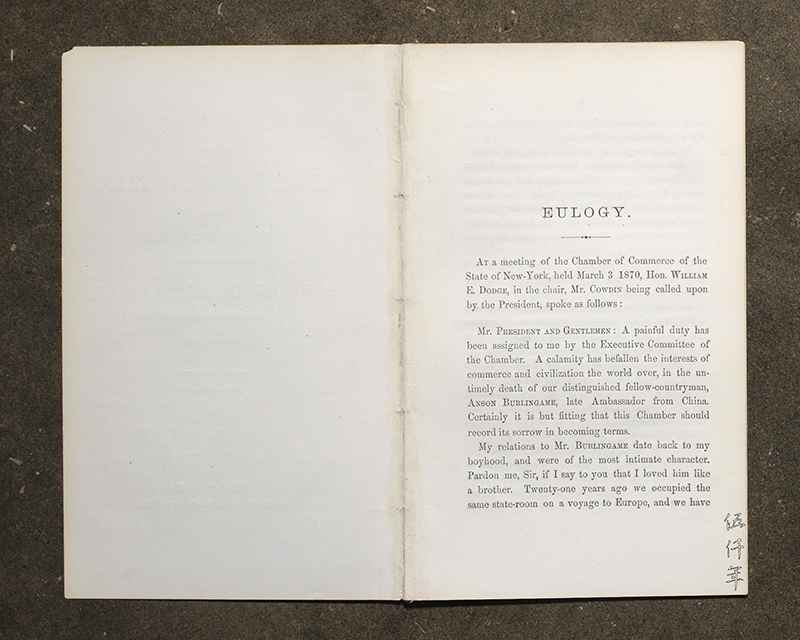

Ambassador from China, March 3rd 1870 Inner page of Tribute of the Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York, in the Memory of Anson Burlingame, Late Ambassador from China, March 3rd 1870

On 3rd March 1870, a memorial was held by the Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York. The eulogy was given by Elliot C. Cowdin, an old friend of Burlingame, and printed into a booklet. The eulogy was an affectionate portrait of the character of Burlingame.

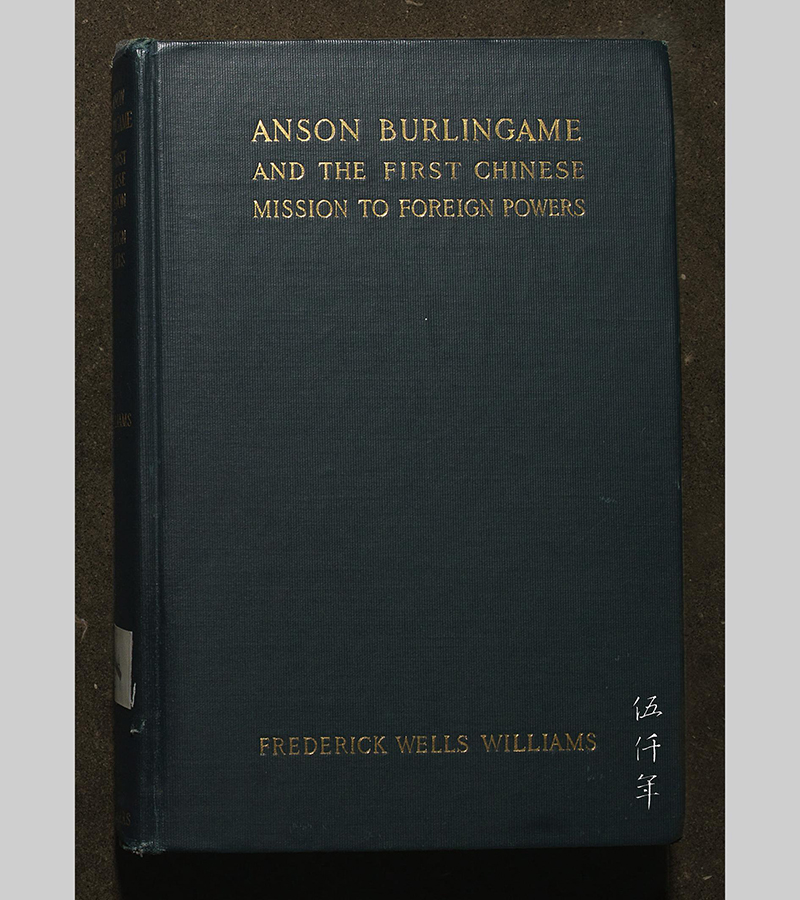

Front cover of Anson Burlingame and the First Chinese Mission to Foreign Powers by Frederick Wells Williams

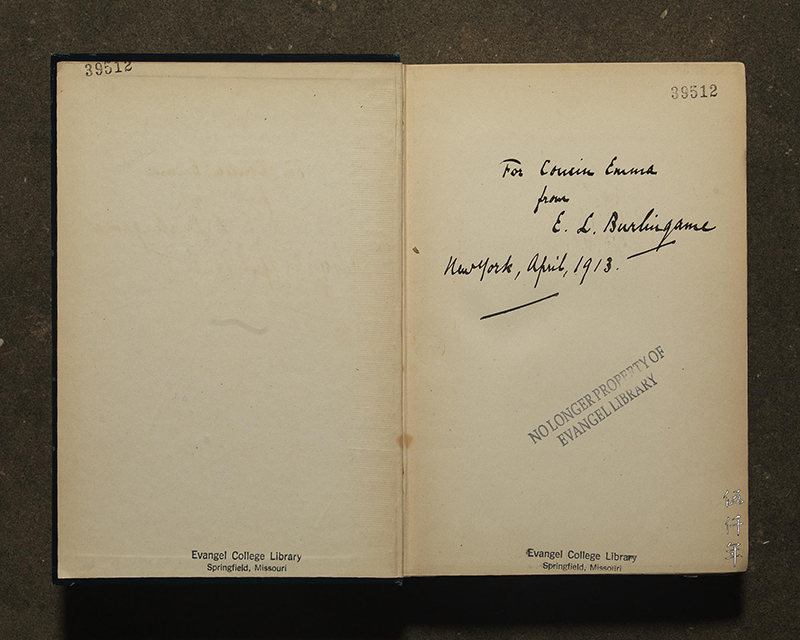

Inside page of Anson Burlingame and the First Chinese Mission to Foreign Powers by Frederick Wells Williams, signed by Edward Burlingame

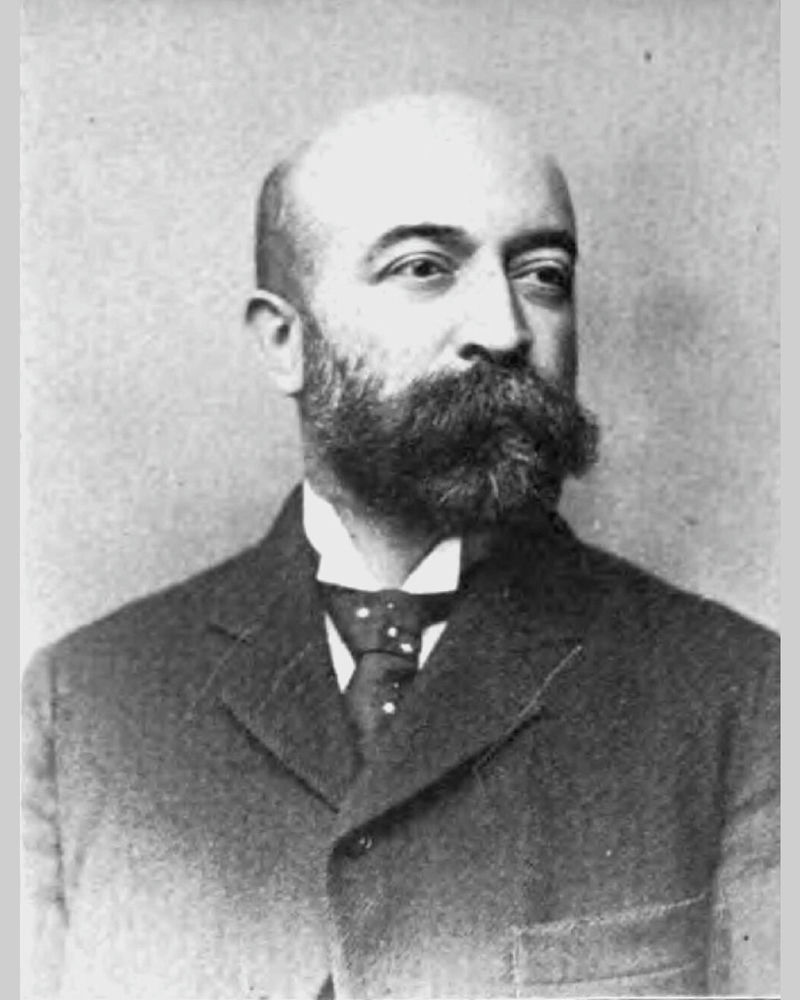

Portrait of Edward L. Burlingame

When Anson Burlingame was minister to China, his son Edward Livermore Burlingame (1848-1922) was his private secretary. After returning to America, he worked as editor of newspaper and magazine. In April 1913, Edward inscribed the only biography of his father: Anson Burlingame and the First Chinese Mission to Foreign Powers, as a gift to his younger cousin Emma Burlingame (born 1874). The author is Frederick Wells Williams (1857-1928), American Sinologist, son of Samuel Wells Williams (1812-1884), also a famous Sinologist. When Burlingame was minister to China between the years 1861 and 1867, Samuel Wells Williams was the chargé d’affaires in Peking. Frederick and Edward must be well acquainted with each other.

Burlingame is faraway in history, but an association piece of paper, or an association copy of a book, is ample to summon the past for reflection.

Initials logo of Anson Burlingame on top left of letter sheet