Prof. Pierre Ryckmans (1935-2014), nom de plume Simon Leys, was an internationally renowned Sinologist, writer and literary critique. He was a native of Brussels, Belgium. During the Cultural Revolution in mainland China, he published Les Habits Neufs du President Mao (The Chairman’s New Clothes- Mao and the Cultural Revolution) in 1971, Ombres Chinoises (Chinese Shadows) in 1974, and Images Brisees (Broken Images) in 1976, becoming a pioneering western scholar to reveal the true nature of the Cultural Revolution. In 1997, he published The Analects of Confucius, universally regarded as a masterpiece of translation in Chinese Classics.

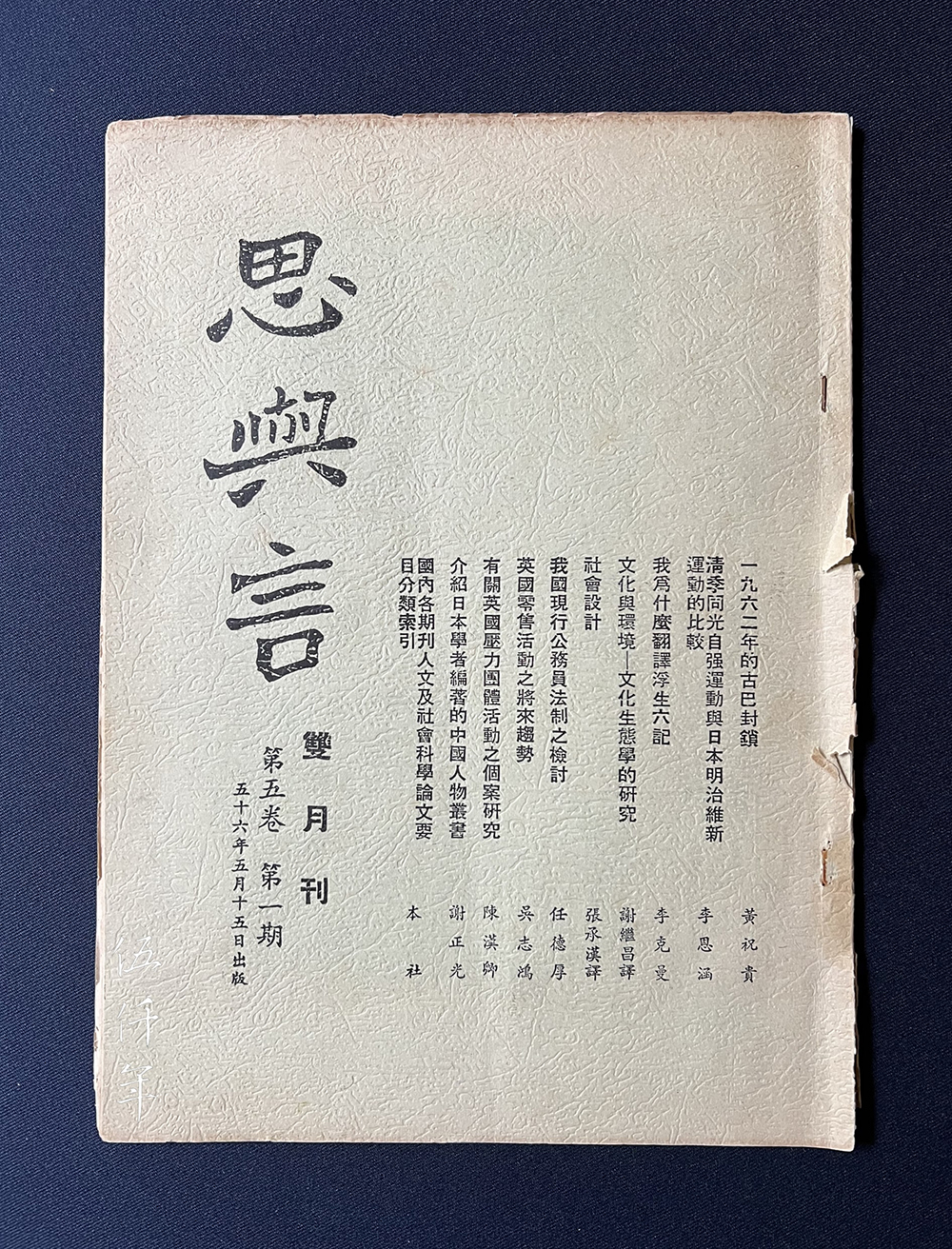

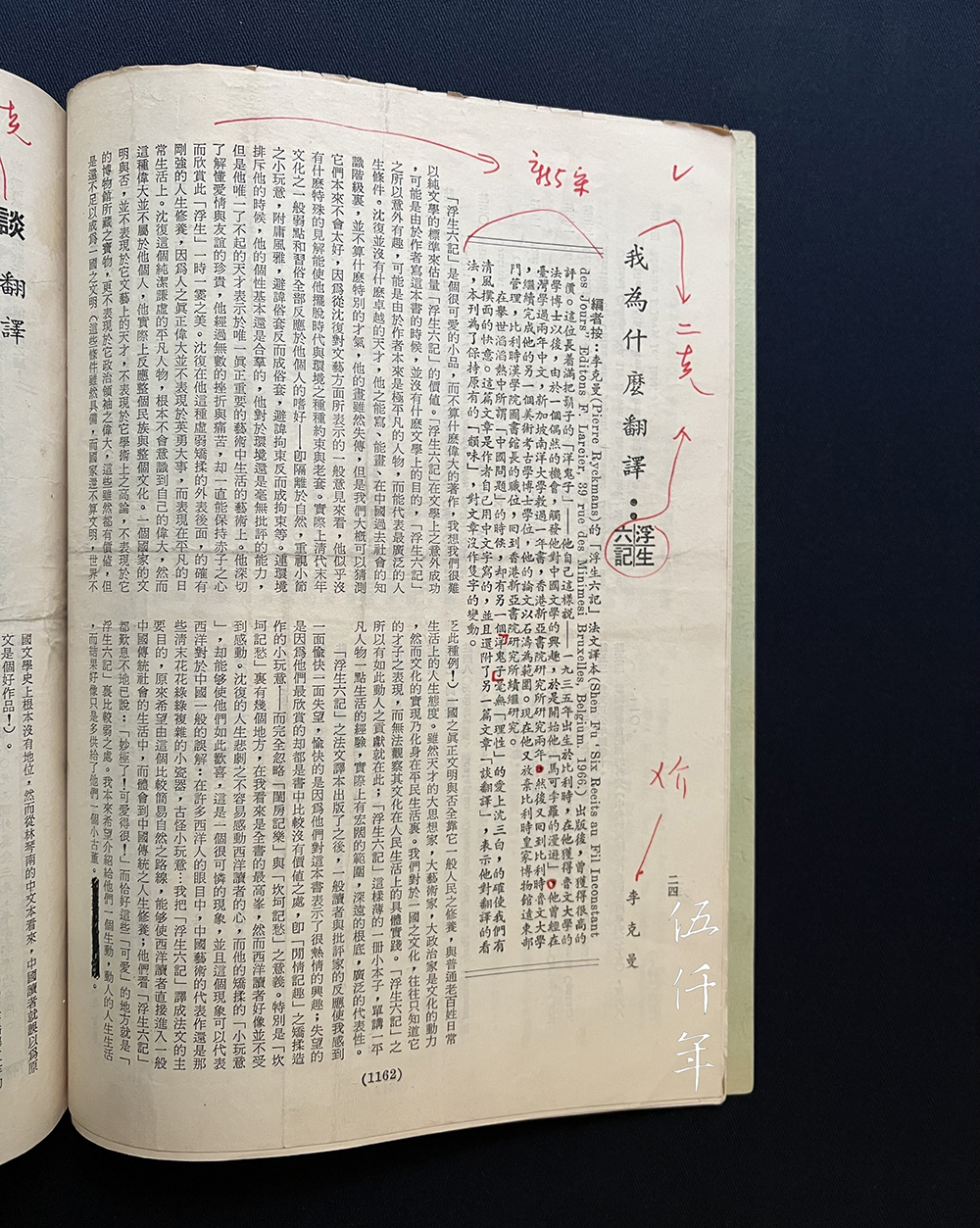

Upon the tenth death anniversary of Prof. Pierre Ryckmans, Dr. Annie Luman Ren (任路漫), the accomplished student of Prof. John Minford, translated into English Why I Translated Six Chapters of a Floating Life (我為什麼翻譯浮生六記) and On the Experience of Literary Translation (談翻譯), two articles written in Chinese by Prof. Ryckmans nearly sixty years ago. They were both originally published in the bi-monthly magazine Thought and Words (思與言) 1st Issue 5th Volume, dated 15 May in the 56th year of the Republic (1967). Besides, these two pieces of translations by Dr. Ren won the 2023 CSAA/AALITRA Chinese-English Translation Award. The Chinese-Heritage Virtual Museum is delighted to present the two little known articles by Prof. Ryckmans, and the incisive translations by Dr. Ren.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

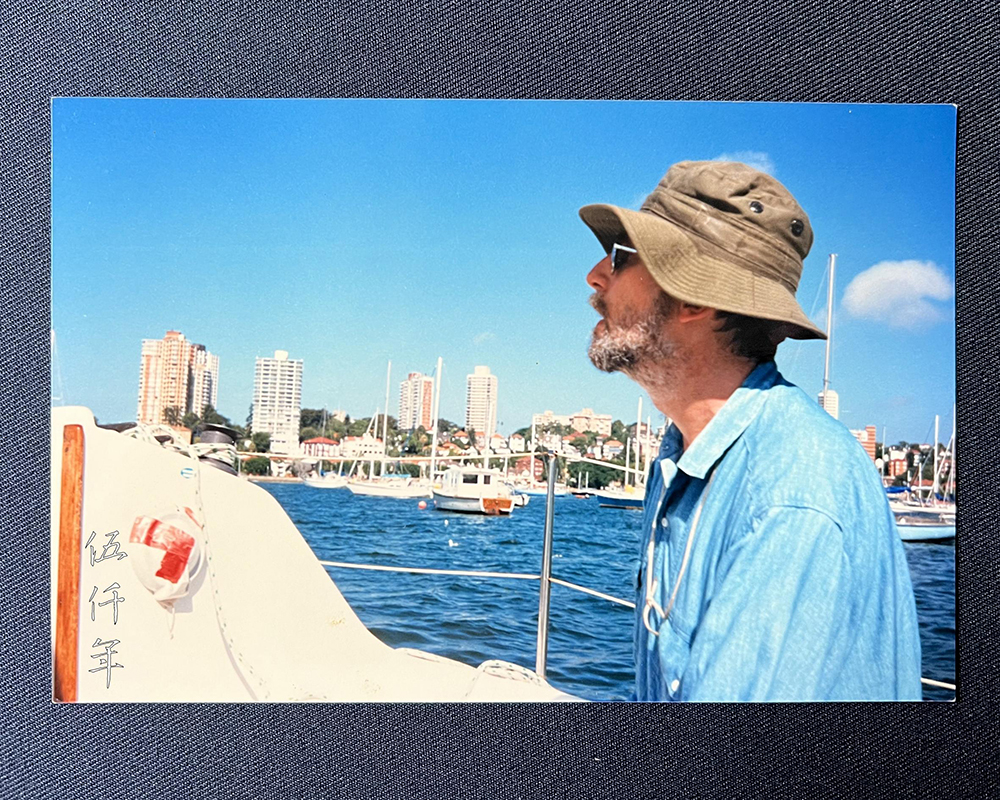

Portrait of Prof. Pierre Ryckmans. Photograph courtesy Mrs. Hanfang Ryckmans

Introduction

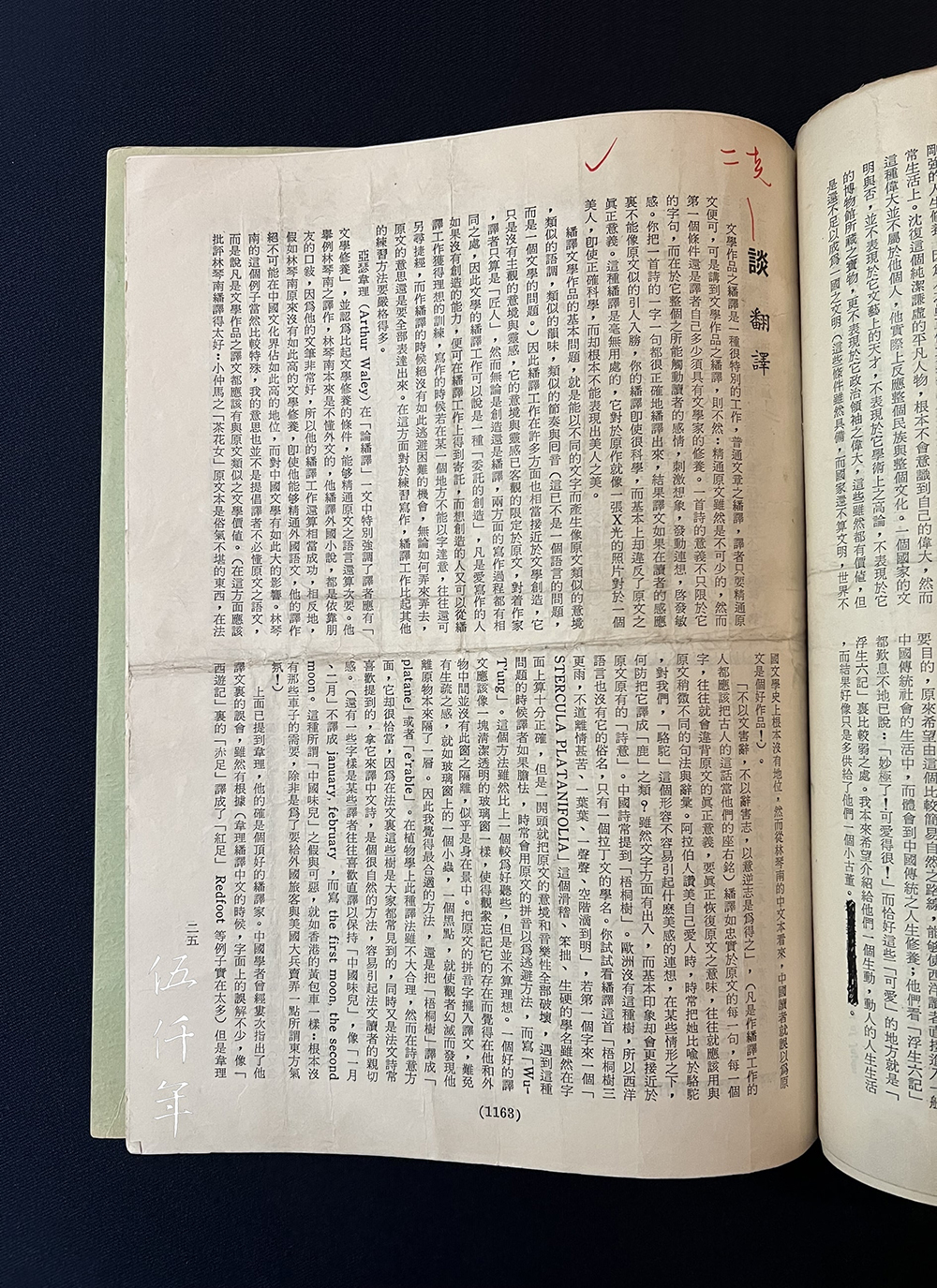

The two essays translated below have a special interest for three reasons. Firstly, they were written by Ryckmans, then a young man in his early thirties, in Chinese, after having studied the language for just a decade. The essays appeared in 1967 in the May issue of the journal Thought and Words (思與言). This journal was established by a group of publicly-minded scholars in Taiwan in 1963, two years after the prominent liberal publication Free China (自由中國) was forced to shut down. The journal, which published on a wide range of subjects including history, sociology, philosophy, and anthropology, was seen as a breath of fresh air in the otherwise stifling intellectual environment in Taiwan. In the editorial note that preceded the two essays, the editors specifically noted that to preserve the original flavour (韻味) of Ryckmans’ writing, they made no editorial changes to his Chinese submission. It may be of interest to the general reader who can read the original to sample Ryckmans’ style of writing in Chinese. Secondly, the topic of the two essays will appeal to those who are interested in translation and Chinese literature.

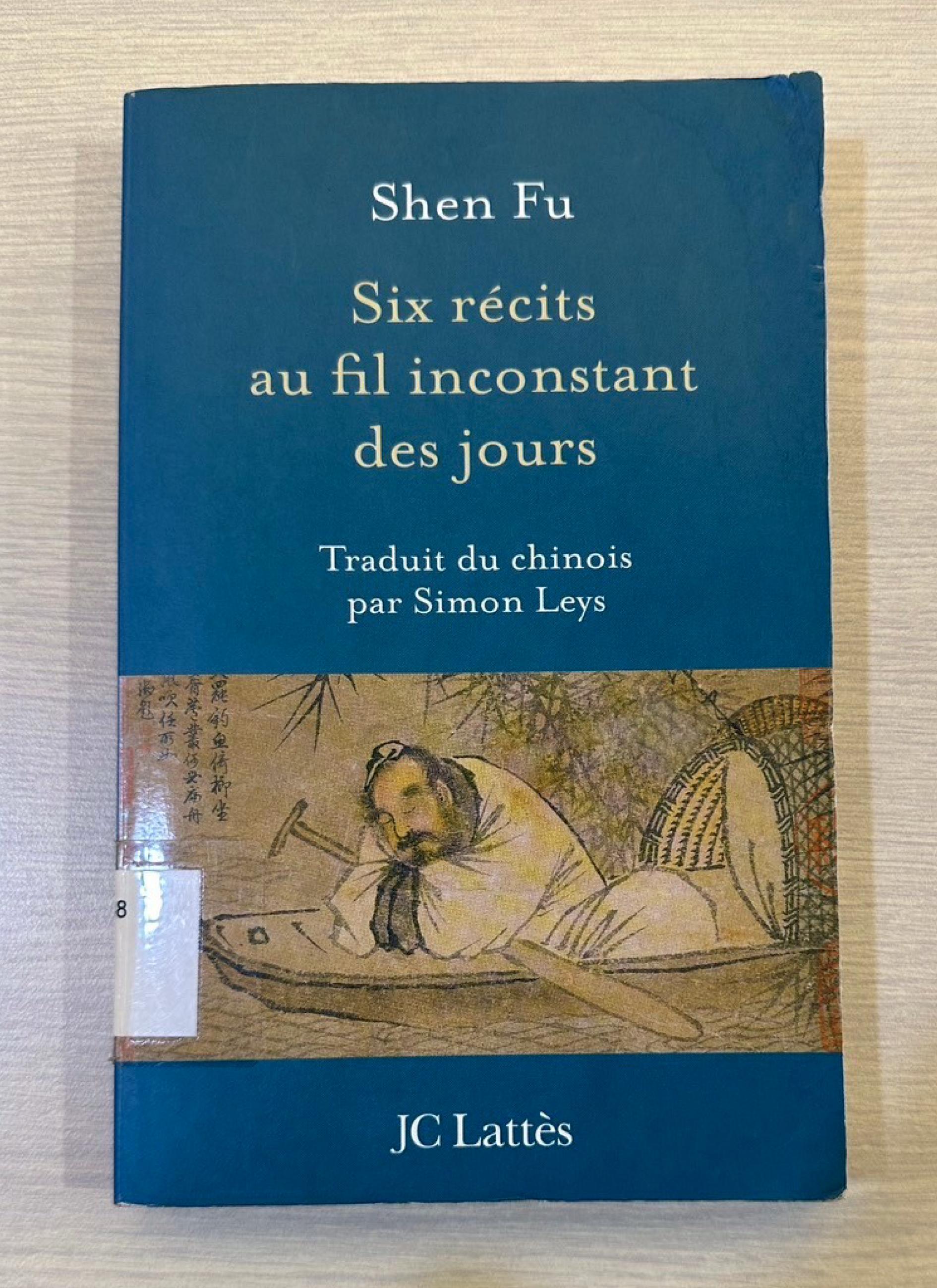

The first essay entitled Why I Translated Six Chapters of a Floating Life was written a year after the publication of Ryckmans’ French translation (using his pen-name or nom-de-guerre Simon Leys) of Shen Fu’s (沈復) nineteenth-century autobiographical memoir Fu sheng liu ji (浮生六記), Six Chapters of a Floating Life, which he entitled in French Six Récits au fil inconstant des jours. In this essay, Ryckmans shared his thoughts on the book and the reasons why he had chosen to translate it. He also expressed his disappointment at the way French readers tended to adore Shen Fu’s idle pursuits while overlooking the emotional depth of the book. This, in Ryckmans’ view, reflected the general misunderstanding of Westerners towards China and their obsession with oriental trivia. Given that Ryckmans rarely discusses this book later in his career (there’s almost nothing written on the subject by him in English) and since it is the first translation from Chinese he ever undertook, the essay provides new insight into Ryckmans as a literary critic and attests to his life-long devotion to Chinese literature and art.

The second essay On the Experience of Literary Translation dwells on a more familiar subject since Ryckmans articulated his views on literary translation on many occasions. Nonetheless, given that this essay was written earlier in his career, it shows the continuity in his thinking as well as in his practice of translation.

Lastly, despite being written some fifty years ago, the two essays have not lost their relevance today. In their preface to the two essays, the Chinese editors remarked how refreshing it was, at a time when the world’s attention was focussed on “The China Problem”, to find a bearded “foreign devil” (洋鬼子 Ryckmans used the term to describe himself) who had “irrationally” (不理性 the term used by the editors) fallen in love with Shen Fu and had devoted himself to introducing this book to the Western audience.

Now, once again, we find ourselves living in a world that is obsessed with “the China Problem”, a world in which governments tend to view any research related to the country’s culture (unless it’s about Chinese interference) as “not in the national interest”. It is my sincere hope, that by making these essays available to the English reader, more people will become “irrationally” inspired by Ryckmans. As for Ryckmans’s views on literary translation – how translations cannot be “produced upon request”, since the translator must first empathise with the author’s feelings, ideas, and attitude towards life–this is no doubt a sober reminder in our current paradigm shift brought on by AI tools such as ChatGPT.1

I wish to thank Mrs Hanfang Ryckmans who kindly showed me the two essays during a workshop commemorating Pierre Ryckmans and his legacy organised by Dr Claire Roberts at The Australian National University in December 2022. I am also grateful to Dr Mark Strange and Yayun Zhu for their helpful comments on my first draft and to Professor John Minford for his careful edits and anecdotal commentaries.

Front cover of Thought and Words Magazine, published on 15 May 1967 in Taiwan. Photograph courtesy Mrs. Hanfang Ryckmans

Why I Translated Six Chapters of a Floating Life by Prof. Ryckmans published in Thought and Words Magazine. Photograph courtesy Mrs. Hanfang Ryckmans

Essay One: Why I Translated Six Chapters of a Floating Life

Six Chapters of a Floating Life is a delightful vignette. It can hardly be considered a literary masterpiece and it is difficult for us to evaluate its significance from a purely literary perspective. Indeed, the unexpected success of this book lies paradoxically in the fact that its author had no intention of writing a work of literature in the first place. And its surprising appeal derives from the fact that its author, Shen Fu, was very much an ordinary person, one who could represent the broadest range of life experiences.

Shen Fu had no extraordinary talents. He could write and paint, but this was hardly exceptional among the educated class of China’s past. Though none of his paintings have survived, we can probably guess that they were not particularly good to begin with — judging from his rather trite views on literature and art, Shen Fu seems to have had little originality to set him apart from the constraints and clichés of his time. In fact, the general cultural weaknesses and conventions of the late Qing (1644-1912) are fully reflected in Shen Fu’s personal taste and preferences: his detachment from nature, his obsession with trifling things, and his pretentious pursuit of “elegance”. He is conventional in his very denial of conventions, artificial in his rejection of artifice. Even when treated poorly and ostracised by those around him, Shen Fu remained largely a conformist, incapable of viewing his surroundings critically. His only remarkable talent manifested itself in the one thing that truly matters: the art of living. He understood the value of love and friendship; and despite experiencing countless hardships and sorrows in his life, he held onto a child-like heart, and appreciated the fleeting beauty of each passing day, of what he called this “floating life”.

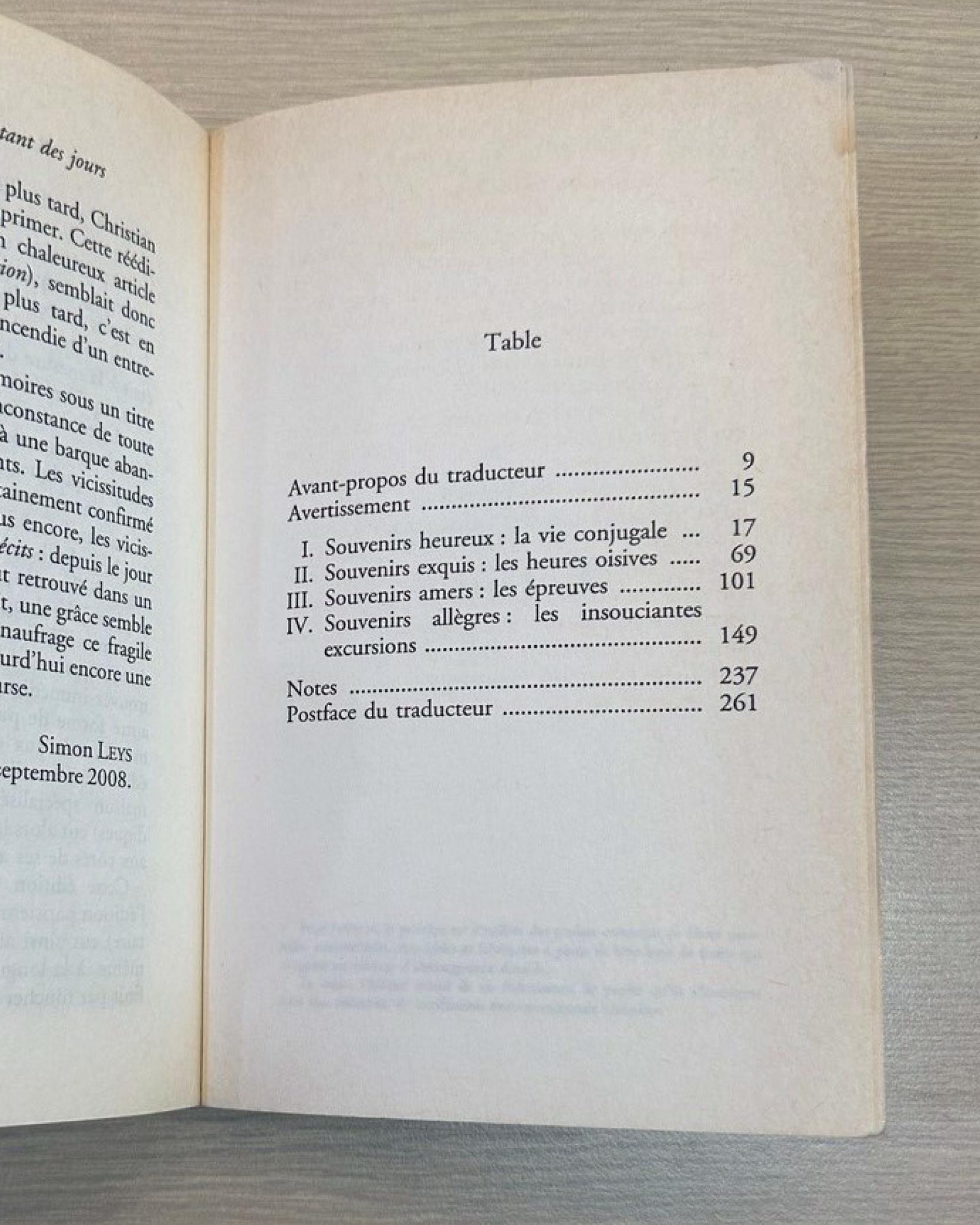

Front cover of Six Récits au fil inconstant des jours (Six Chapters of a Floating Life), translated by Prof. Ryckmans

Indeed, beneath Shen Fu’s feeble and pretentious surface lay an unwavering commitment to living a cultivated and artistic life. After all, true greatness is not reflected in heroic deeds but in the minutiae of everyday life. Shen Fu was just an ordinary person, and he was far too ingenuous to recognise his own greatness. Moreover, this greatness did not belong to him personally, it reflected the greatness of an entire people and culture.

A nation’s civilisation cannot be measured by its achievement in literature and art, or by its scholarly excellence, or by the number of treasures stored in its museums. Even more certainly it cannot be measured by the greatness of its political leaders. These are useful indicators, but they are not enough to constitute the civilisation of a nation (there are countries in the world that possess all the above and yet still cannot be considered civilised). The true measure of a nation’s civilisation lies in the cultivation of its people and their attitude towards life. Great thinkers, artists, and politicians are the driving force behind a culture, but culture itself is embodied in the lives of ordinary people. Generally, we have no way of observing the specific ways in which a culture manifests itself through the lives of its people, and our understanding of a culture is usually limited to the achievements of its greatest minds. Here lies the greatest contribution of Six Chapters of a Floating Life and why it is so inspiring: this little booklet only recounts the lived experiences of an ordinary person in late imperial China, but it is rooted in a profound cultural tradition and is far reaching in its portrayal of a broad range of human experiences.

Table of Six Récits au fil inconstant des jours (Six Chapters of a Floating Life), translated by Prof. Ryckmans

Since my French translation Six récits au fil inconstant des jours has been published, the reactions from readers and critics have been gratifying and at the same time disappointing. I am gratified by their enthusiasm for this book, but disappointed because what they appreciated most were, in my view, the relatively insignificant parts, such as Shen Fu’s trifling pursuits in the chapter which I called Idle Hours (Les heures oisives). Meanwhile, they completely overlooked the importance of chapters like Married Life (La vie conjugale) and Tribulations (Les épreuves). The latter, in particular, was for me the high point of the entire book, and yet, Western readers seem entirely unmoved by it. Indeed, it is regrettable that the tragedy of Shen Fu’s life has not touched the hearts of his Western readers, while his frivolous pleasures have elicited such delight. This reflects a general misunderstanding of China on the part of Western readers. In their eyes, Chinese art is still characterised by chintzy ceramics and exotic trinkets from the late Qing.

My intention in translating Six Chapters of a Floating Life was to enable Western readers to experience more readily daily life in traditional Chinese society and to appreciate the cultivation of its people and their art of living. After reading my translation, many readers have exclaimed, “Marvellous! How charming!” without realising that these “charming” moments are precisely the shortcomings of the book. I had originally hoped to introduce Western readers to a lively and moving part of human life. In the end, though, I seem to have given them just another curio.

On the Experience of Literary Translation by Prof. Ryckmans published in Thought and Words Magazine. Photograph courtesy Mrs. Hanfang Ryckmans

Essay 2: On the Experience of Literary Translation

Literary translation is a unique sort of work. To translate a text of a general or practical nature, the translator simply has to be proficient in the language of the original. But the same cannot be said about literary translation. Although proficiency in the source language is certainly required, it is imperative for the literary translator to have the skill and sensibility of a writer in the target language.

The meaning of a poem extends beyond its words, it relies on its overall emotional impact on the reader, as well as its ability to stir the imagination, to inspire associations and to heighten the reader’s sensibility. Even when the translator has rendered every word in a poem with a degree of technical sophistication, if the end result does not move the reader in a way similar to the original, then the translator will have failed to convey the poem’s true meaning. A translation of this kind is useless — it is akin to examining the X-ray of a beautiful woman. The image may be scientifically accurate, but it fails to capture the woman’s actual beauty.

Literary translation is fundamentally about echoing the mood, tone, sentiment, and cadence of the original in a different language. This is no longer a linguistic endeavour, but a literary one. In many ways, literary translation is in fact closely related to literary creation, except that there is no room for the translator’s own artistic conception and ingenuity. In this sense, the translator is indeed a mere “craftsman” in relation to the author who is the true creator of the text. Nonetheless, translators and authors share a similar creative process, and literary translation can be seen as a form of “commissioned creation”. Those who love writing but lack creativity can find fulfilment in literary translation, while those who aspire to write creatively themselves can acquire an ideal training through translation. When writing, if there comes a point where meaning cannot be expressed by words, there are usually other ways around it. But there can be no shortcuts in translation. Regardless of how one tries, the words of the original text must be fully expressed. In this regard, translation is much more demanding than other kinds of writing.

Portrait of Arthur Waley

In his Notes on Translation, Arthur Waley emphasised the primary importance of the translator’s literary cultivation in the target language. It is more important than the translator’s proficiency in the language of the source text. He used Lin Shu’s nineteenth-century translations of European fiction as an example. Lin Shu did not know any foreign languages, and he translated European novels relying entirely on oral accounts given to him by his friends. But because he was such an excellent writer of literary Chinese, Lin Shu’s translations were very successful. Conversely, had Lin Shu not been such a great stylist, even if he had understood foreign languages, his translations would not have been so highly regarded by his Chinese readers, and would not have had such a significant influence on the later development of Chinese literature.

Portrait of Lin Shu

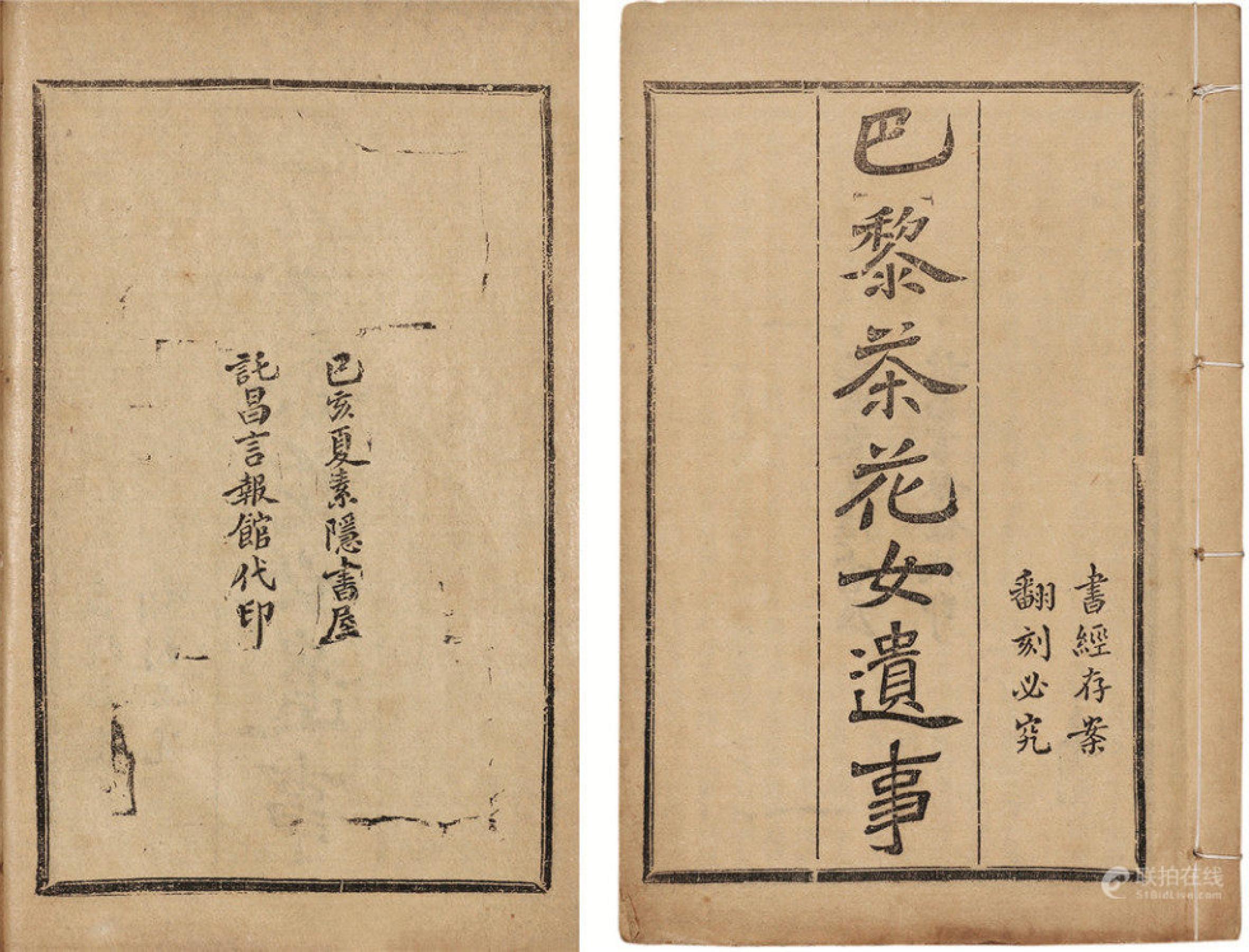

Lin Shu’s, of course, is a most unusual case. Here, I am not advocating that translators should be without any understanding of the language they are translating from. My point is this, that literary translations should strive to attain the same literary value as their originals. (In this regard, one could even criticise certain of Lin Shu’s translations for being too good: Alexandre Dumas fils’ La Dame aux Camélias is no more than a work of lowbrow fiction, and has no serious place in French literary history. But from reading Lin Shu’s translation, Chinese readers may have come to consider it highbrow!)

Title page of Lin Shu’s translation of La Dame aux Camélias

When asked how to best understand the poems in the ancient collection the Book of Odes, the philosopher Mencius said, “Do not dwell on individual words so as to detract from their broader meaning; do not dwell on their meaning so as to obscure their deeper poetic intent. Only through one’s own feeling and experience can a poem’s true intent be grasped.” I think every translator should have this as their motto. Indeed, a faithful word-for-word translation often deviates from the true meaning of the text. Sometimes, to convey the essence of the original, it may even be necessary to alter its syntax and vocabulary slightly. For instance, when Arabs praise their loved ones, they often compare them to camels. But for us, the word “camel” does not evoke any associations of beauty. In certain situations, why not translate it into “swan” or something with a similar effect? This may be different from the original text, but in terms of its overall effect, it actually brings readers closer to the “poetry” of the original.2

Chinese poetry frequently mentions the Wu-Tong, a tree commonly found in East Asia. There is no equivalent in Europe, so there is no common name for it, only a botanical one in Latin. Imagine starting the translation of a Chinese poem with the words “STERCULA PLATANIFOLIA”… It may be technically accurate, but this clumsy, ridiculous-sounding name undoubtedly destroys the lyrical beauty of the original. When faced with problems such as this, a timid translator might resort to transliteration. But although Wu-Tong may sound a bit better than “STERCULA PLATANIFOLIA”, it still falls short of the ideal.

A good translation is like a clean, transparent glass window. Viewers should be able to forget the barrier separating them from the scenery they are enjoying. Placing a transliterated word into a translation inevitably introduces a sense of something foreign, like a small insect or a black dot on an otherwise clear glass window. It creates a barrier. Viewers are jolted from their illusion when they become aware of a barrier such as this. For this reason, I believe it is appropriate to translate Wu-Tong into platane or érable (maple). Botanically speaking these are both inaccurate, but on a poetic level, they are quite suitable. Maple trees are commonly found in France and French poetry frequently mentions l'érable. Using it as a substitute for Wu-Tong when translating Chinese poetry will make the translation more natural-sounding and evoke a sense of familiarity for French readers. (Some translators prefer translating certain words literally to maintain a so-called ‘Chinese flavour’. Instead of translating the months into ‘January’ and ‘February’ they prefer ‘the first moon’ and ‘the second moon’. This attempt to create a faux ‘Chinese flavour’ is detestable. It’s like Hong Kong’s yellow rickshaws, which simply provide foreign tourists and American soldiers with a false sense of ‘the Orient’!)

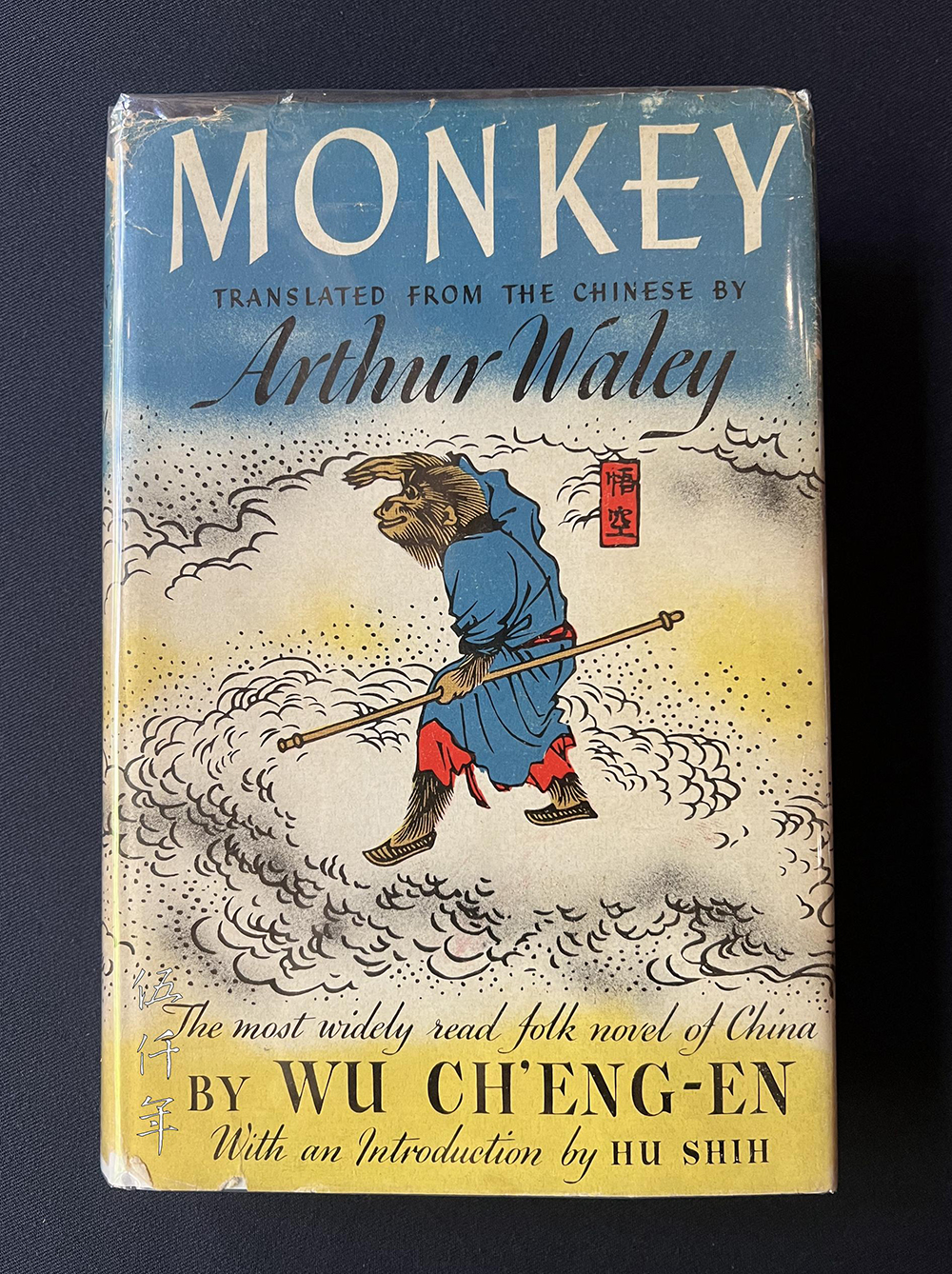

Front cover of Arthur Waley’s translation of Monkey by Wu Ch’eng-en

I have already mentioned Waley. He is indeed a most excellent translator. Chinese scholars have frequently pointed out his mistakes and misinterpretations. They do so with good reason, for there are countless cases of literal misunderstanding in Waley’s translation (one example would be how he mistook ‘barefoot’ 赤足 for ‘red foot’ in his translation of Monkey). Nonetheless, given Waley’s superb literary skill and sensibility, even though there were the occasional misunderstandings in his reading of Chinese poetry, he was still able to convey the overall feeling and cadence of the original to his readers using the most natural-sounding English. Had he been translating a scientific or academic work, these textual discrepancies would have undermined the value of his translation. However, since he was translating literary texts and his goal was to introduce Chinese literature to English readers, Waley’s endeavours can be considered to have been highly successful. Thanks to his excellent command of English, his translations reached beyond the limited circle of experts and attracted a wider literary and cultural interest. His translations made Chinese literature easily accessible to ordinary readers and provided Western writers with new sources of inspiration. The great twentieth-century poet T. S. Eliot once praised Waley’s translations saying, “We modern English writers all owe a debt to Waley.” This is sufficient proof of Waley’s contribution to the literary world. (There may be other translations that are more accurate than Waley’s, but if these translations cannot achieve the same degree of literary excellence, then they will never be as influential.)

When performing on the stage, good actors forget their own identity and temporarily merge with the character they play. In my opinion, translators should undergo the same process with regard to the author of their text. At the very least, they should empathise with the author’s feelings, ideas, and attitude towards life. That is why translations cannot be “produced upon request”. By this I mean that translators should themselves choose the works they want to translate based on their own preferences, rather than being assigned a translation task by some cultural institution or publisher. Translators should be driven by a strong urge to translate a particular work, regardless of its usefulness or whether it will be published or capture the reader’s interest. Their impulse must be similar to the creative impulse of a writer. Translators should feel, “I must translate this work, just for the hell of it!”3

Regardless of its success, translating a literary work enables the translator to develop a deeper appreciation of the original. While translating, the translator can participate in the author's creative journey and grasp the raison d'être behind every turn of phrase. The translator seems to detect places where the author has taken special pride, and is particularly inspired by them. All the characters, events, scenes, and objects depicted by the author dissolve within the translator's sensibility, so much so that the translator may be under the illusion that everything has originated within their own personal experience. Only when this state of mind, this mental ‘realm’, has been attained can the true essence and nature of literary translation be realised. Then, spurred on by the impulse of the original text, the translator may sometimes end up writing with a brilliance never achieved before, may be enabled by the brilliance of the writer to enter realms never before imagined, like the proverbial fly galloping a thousand leagues seated on the horse’s tail. Such is the intoxicating experience of true literary translation!

1 John Minford recalls sitting next to Ryckmans at a conference on translation theory organised by John Frodsham and André Lefevere at The Australian National University in the late 1970s. Ryckmans had been completely silent throughout (he was extremely bored by translation theory). Towards the end of the conference, Frodsham begged him to say something. Ryckmans rose reluctantly to his feet and simply said: “You must love what you translate.” These simple words summarise Ryckmans’s lifelong approach and devotion to translation.

2 In their translation of The Story of the Stone (紅樓夢, Dream of Red Mansions), David Hawkes and John Minford tend to render the colour “red” (紅) into either “gold” or “green”. In his introduction to the first volume of The Story of the Stone, Hawkes notes that “red as a symbol–sometimes of spring, sometimes of youth, sometimes of good fortune or prosperity – recurs again and again throughout the novel. Unfortunately–apart from the rosy cheeks and vermeil lip of youth–redness has no such connotations in English and I have found that the Chinese reds have tended to turn into English golds or greens (‘spring the green spring’ and ‘golden girls and boys’ and so forth). ” (Introduction, p.45)

3 This is my borrowing of David Hawkes answer when asked why he decided to translate The Story of the Stone (紅樓夢).

Drawing room in the house of Prof. Ryckmans with his portrait painting. Photograph courtesy Mrs. Hanfang Ryckmans

Related Contents:

A Chinese Newspaper Clipping from the Library of Prof. Pierre Ryckmans