In the 43rd year of the Republic (1954), the shipping magnate Mr. C. Y. Tung (董浩雲) planned to produce a movie about the voyages of Cheng Ho (鄭和 1371-1433? or Chen Ho) to the Western Seas. He first engaged the distinguished dramatist Mr. Yao K’o (姚克) to write an outline of the screenplay titled Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen Ho. It was first published in the Maritime Digest, a bi-monthly magazine, on 30 June in the 49th year of the Republic (1960).

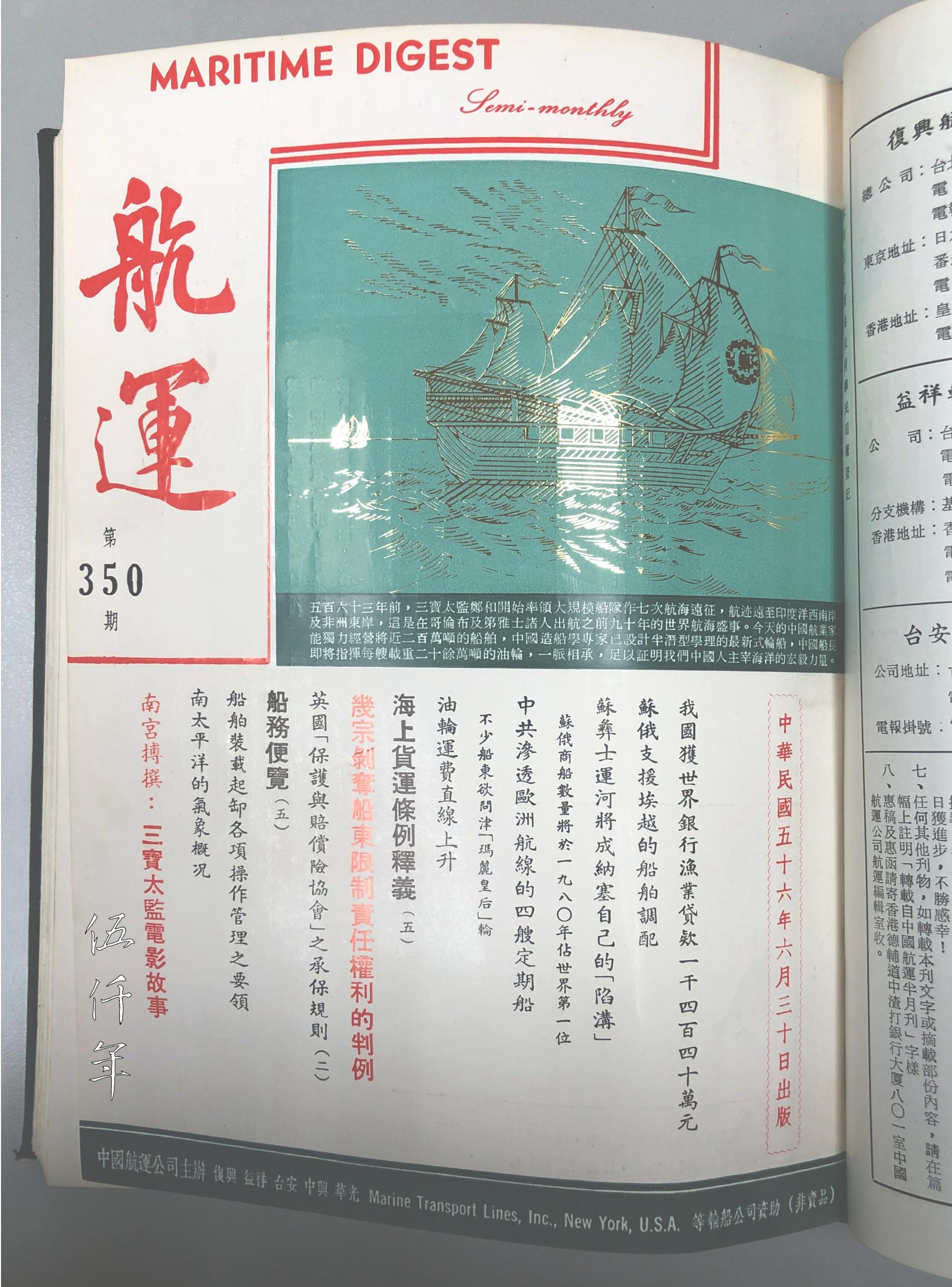

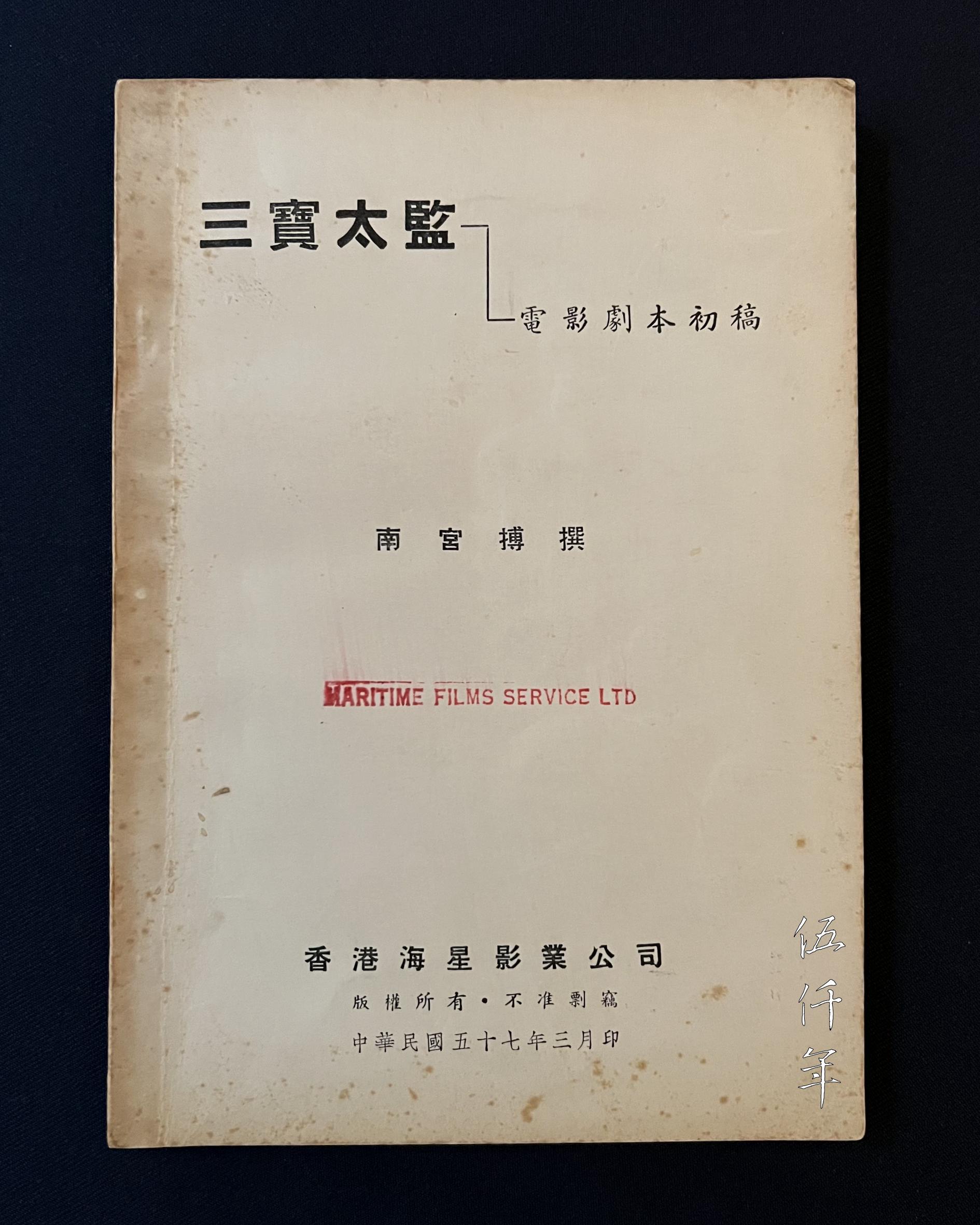

Later on, Mr. Tung engaged the renowned novelist Mr. Ma Pin (馬彬), nom de plume Nan Kung Po (南宮搏 1924-1983), to write another screenplay. His outline of the screenplay used the earlier title Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen Ho. It was published in the bi-monthly Maritime Digest on 30 June in the 56th year of the Republic (1967). The Maritime Digest then reprinted the writing as a booklet in August the same year, supplemented with a translation by Mr. Sherman Wang for better promotion overseas.

In March the following year, Nan Kung Po completed the screenplay. In order to provide easy reading for the directors of Maritime Film Services Ltd. in Hong Kong, the completed screenplay was printed as a book in very small batch. The one presented at the Chinese-Heritage Virtual Museum may be the only extant copy. As far as the outline of the screenplay Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen Ho by Nan Kung Po is concerned, it has not been read for nearly sixty years and is now known by very few. We hereby publish it for our fellow enthusiasts.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

Portrait of Mr. Ma Pin (nom de plume Nan Kung Po 南宮搏)

The writings and demeanour of Ma Pin (馬彬), nom de plume Nan Kung Po (南宮搏), are admired by all. Now he has accepted an invitation from Maritime Digest, the bi-monthly magazine, to write the Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen Ho (三寶太監電影故事), based on his earlier novel The Eunuch San-pao (三寶太監) ten years ago. The story on one hand engages the factual history of Chen Ho (鄭和), on the other hand interweaves some deeply moving fictional tales that are both melancholic and romantic. This is similar to the cinematic approach employed by foreign biographical movies. If this story is to be developed into a movie screenplay in the future, it will definitely achieve immense dramatic effect and create intense international interest about Chen Ho, the man and his deeds. Apart from publishing the original writing in the bi-monthly Maritime Digest Issue Number 350 on 30 June in the 56th year of the Republic (1967), it is now printed in book in with a translation by Sherman Wang (王慎名). This provides easy reading for those from the movie industry.

Soong Hsün-leng

August 1967

Front cover of Maritime Digest Issue Number 350 dated 30 June in the 56th year of the Republic (1967)

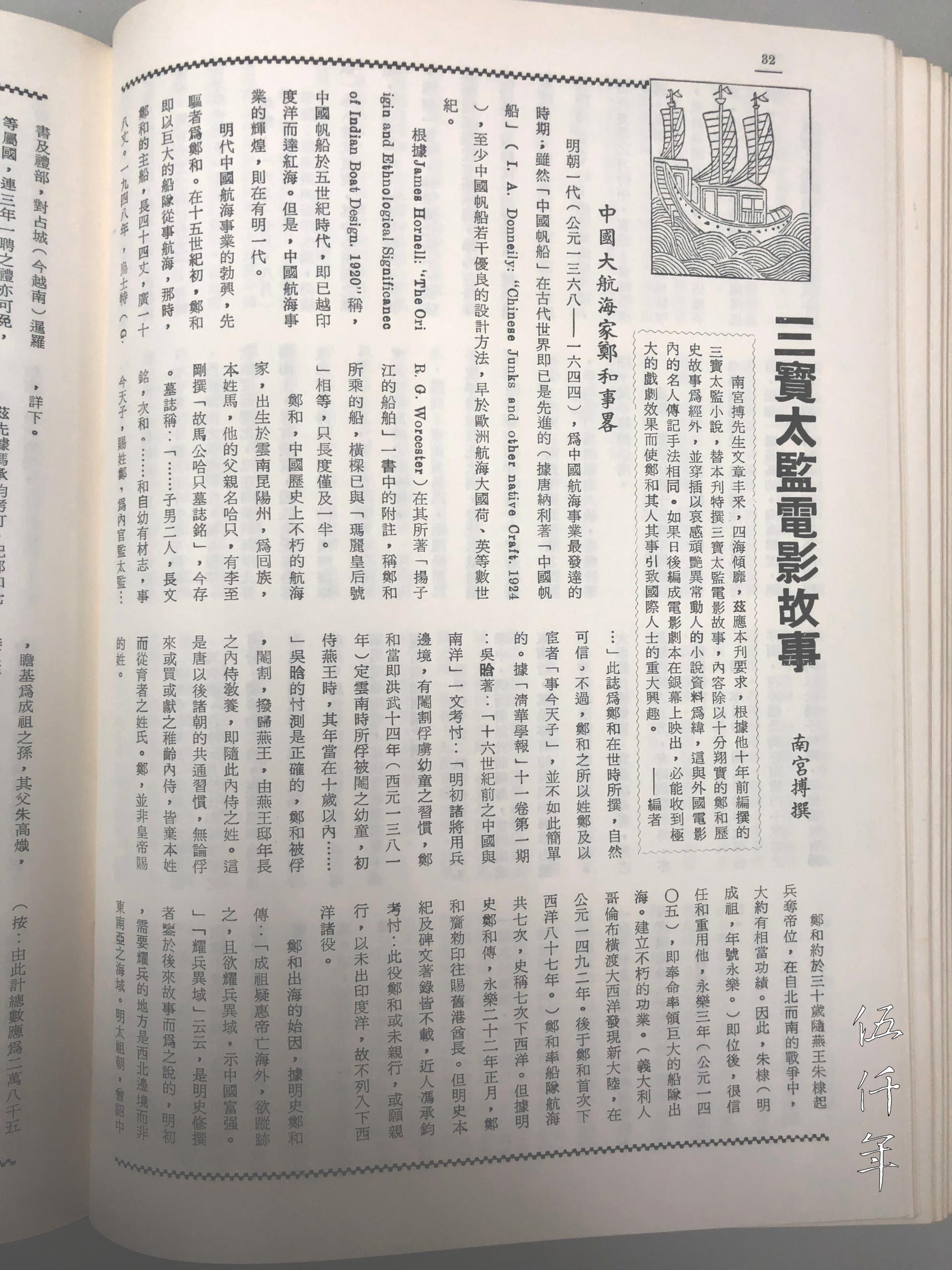

Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen (Cheng) Ho by Mr. Ma Pin (nom de plume Nan Kung Po 南宮搏) published in Maritime Digest Issue Number 350, dated 30 June in the 56th year of the Republic (1967)

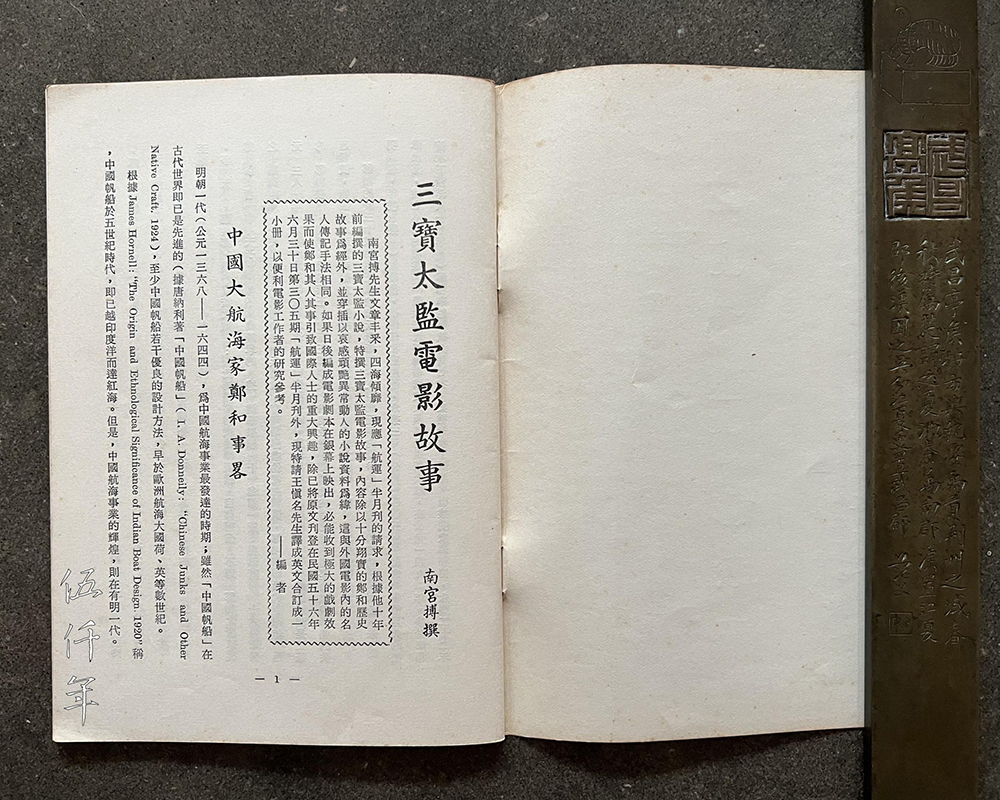

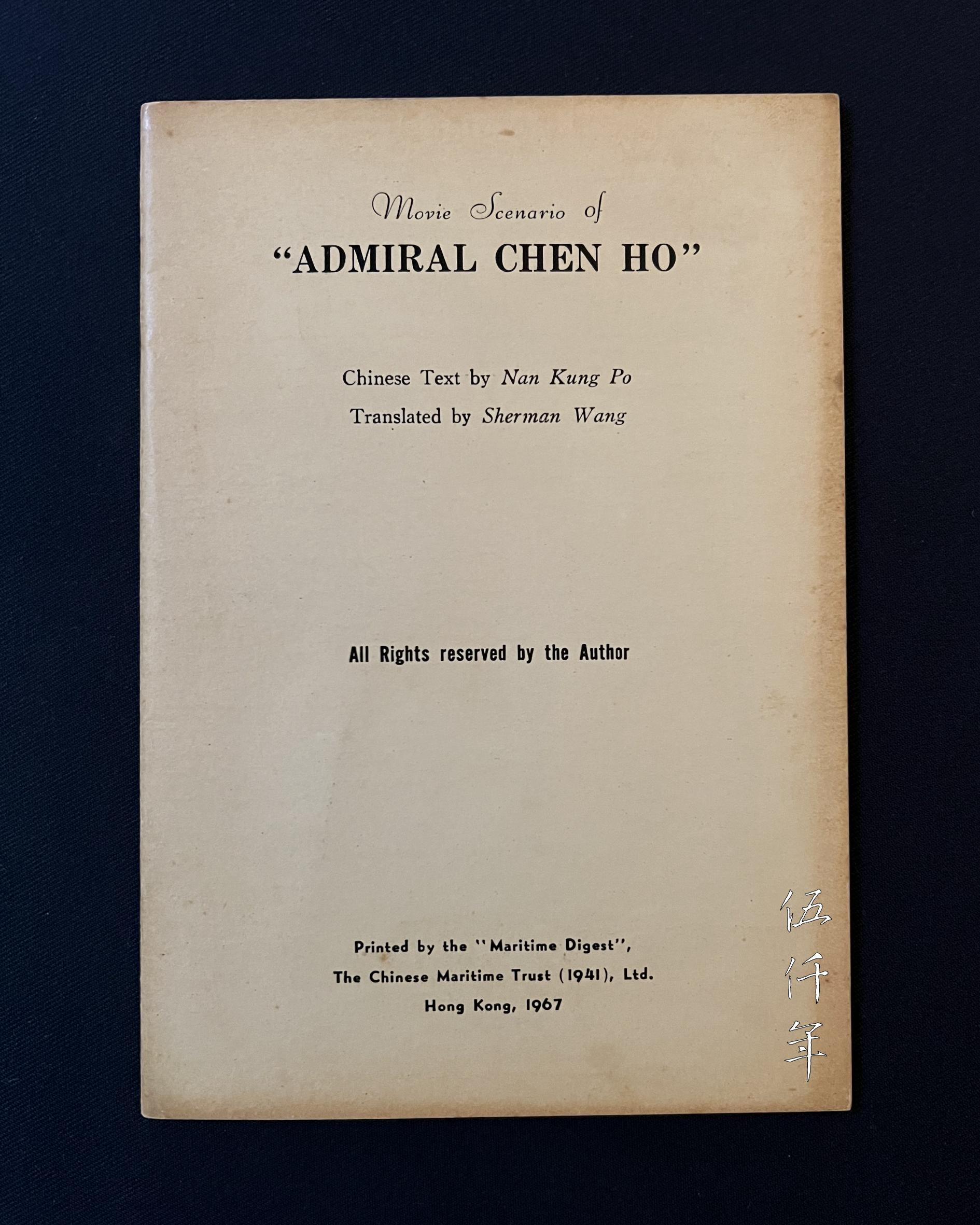

Front cover of Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen (Cheng) Ho by Mr. Ma Pin (nom de plume Nan Kung Po 南宮搏)

Inside page of Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen (Cheng) Ho by Mr. Ma Pin (nom de plume Nan Kung Po 南宮搏)

Back cover in English of Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen (Cheng) Ho by Mr. Ma Pin (nom de plume Nan Kung Po 南宮搏), translated by Mr. Sherman Wang (王慎名)

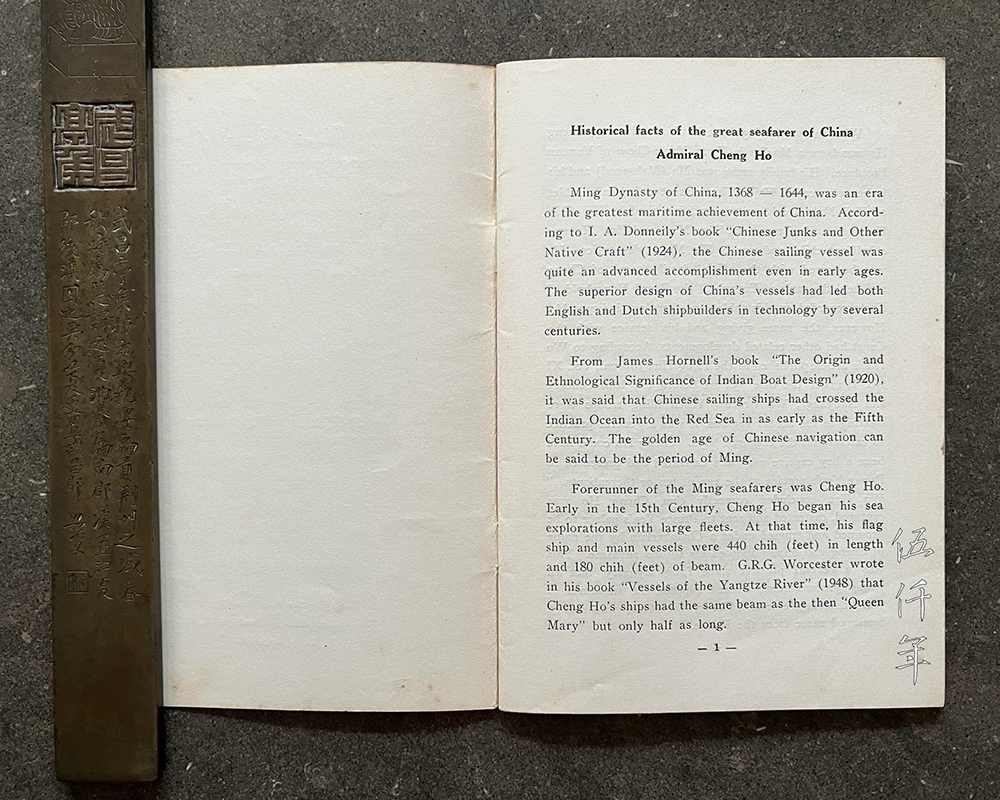

Inside page in English of Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen (Cheng) Ho by Mr. Ma Pin (nom de plume Nan Kung Po 南宮搏) , translated by Mr. Sherman Wang (王慎名)

Historical facts of the great seafarer of China Admiral Chen (Cheng) Ho

Ming Dynasty of China, 1368-1644, was an era of the greatest maritime achievement of China. According to I. A. Donnelly’s book Chinese Junks and Other Native Craft (1924), the Chinese sailing vessel was quite an advanced accomplishment even in early ages. The superior design of China’s vessels had led both English and Dutch shipbuilders in technology by several centuries.

From James Hornell’s book The Origins and Ethnological Significance of Indian Boat Design (1920), it was said that Chinese sailing ships had crossed the Indian Ocean into the Red Sea in as early as the Fifth Century. The golden age of Chinese navigation can be said to be the period of Ming.

Forerunner of the Ming seafarers was Cheng Ho. Early in the 15th Century, Cheng Ho began his sea explorations with large fleets. At that time, his flagship and main vessels were 440 chih (feet) in length and 180 chih (feet) of beam. G.R.G. Worcester wrote in his book The Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze (1948) that Cheng Ho’s ships had the same beam as the then “Queen Mary” but only half as long.

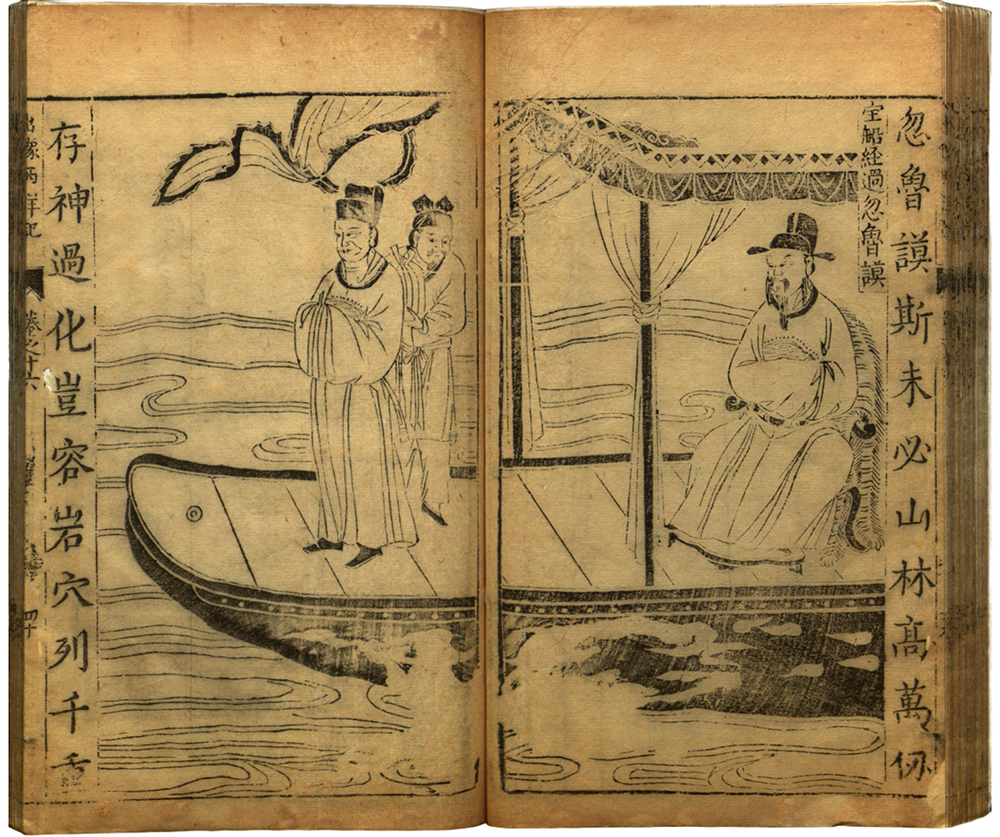

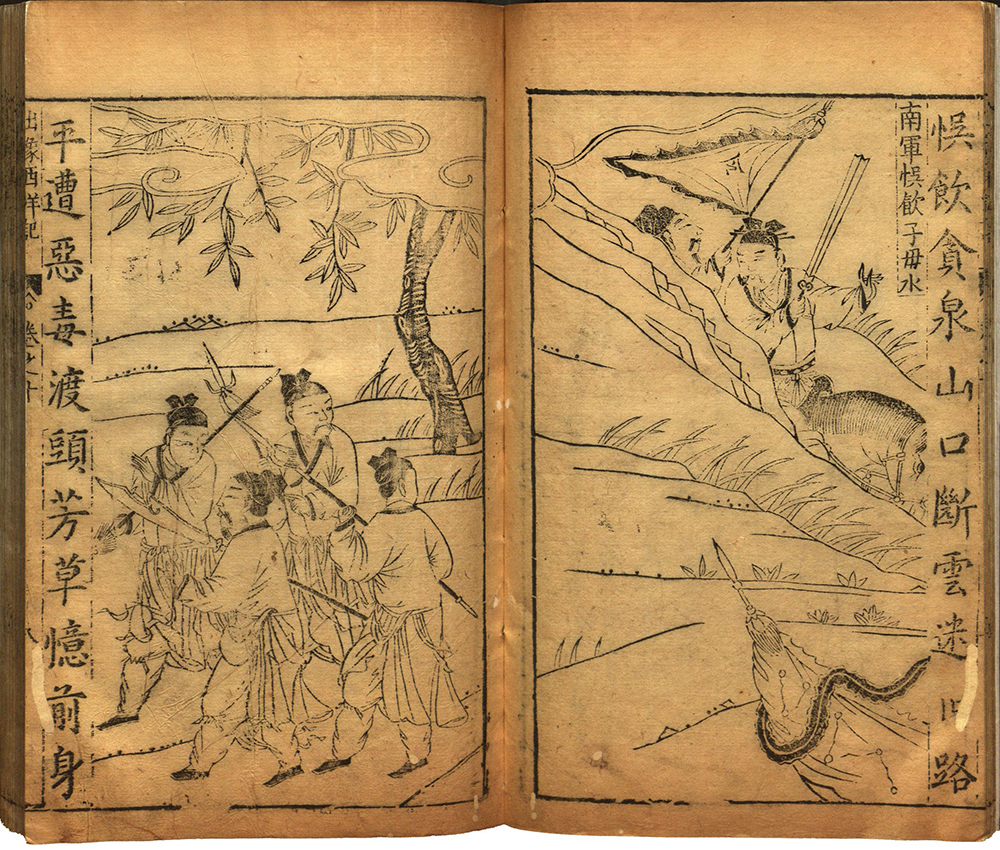

An illustration in Chronicle of Eunuch San-pao’s Voyages to the Western Seas by Lo Mao-teng. Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

With an everlasting fame in Chinese history, Cheng Ho was born a Muslim in Kwun Yang Chow of Yunnan Province. His family name was Ma (Mahmood) and his father was called Haji. This was recorded in a tablet at Haji Ma’s tomb written and inscribed by Li Chih Kang: “…had two sons, Wen Ming and Ho. Ho was a brilliant child, and was in His Majesty’s service. He was bestowed with the official family name of Cheng and held the rank of Eunuch of the Royal Household.” Facts recorded on this tablet are therefore indisputable.

However, the name giving and his service with the Court had other related developments. According to Wu Han’s article published in the Tsing Hua Journal, Vol. XI No. 1, under the title China before the 16th Century and Nanyang, Wu wrote: “When Ming troops were fighting in the border regions, it was a general practice to castrate all the captured boys. Cheng Ho could have been a boy captive who was castrated and presented to Prince Yen’s service at the age of ten or thereabouts.” Wu Han concluded correctly that Cheng Ho was captured, castrated and sent to Prince Yen’s palace to be groomed and trained under a Chamberlain by the name of Cheng and finally adopted his tutor’s surname. This was a general practice since Tang Dynasty that all young grooms being trained adopted the surnames of their tutoring elders. Cheng, therefore, was not a bestowed name from the Prince.

When Cheng Ho was about thirty years old, he followed Prince Yen in his revolution to oust the ruling Emperor. From the north towards the south, Cheng Ho won much honor by his participation in the battles. He won the confidence and trust of Prince Yen who now had become Emperor Yung Lo of Ming. In 1405, he was commissioned to lead a big fleet to sail to the south seas and was credited with many achievements. (Christopher Columbus discovered the Americas in 1492, about 87 years later than Cheng Ho’s first oceanic voyage).

In all, Cheng Ho made seven sea voyages to the western oceans. By the official biography of Cheng Ho, he made yet another voyage to deliver an official great seal to the Sultan of Chiu Kang in 1424; however, this trip was not recorded in other annals or documents. Modern historian Feng Cheng Chun believes that in this expedition, Cheng Ho probably did not go himself personally; and it never reached beyond the Indian Ocean, hence this was not included in the seven voyages to the western oceans.

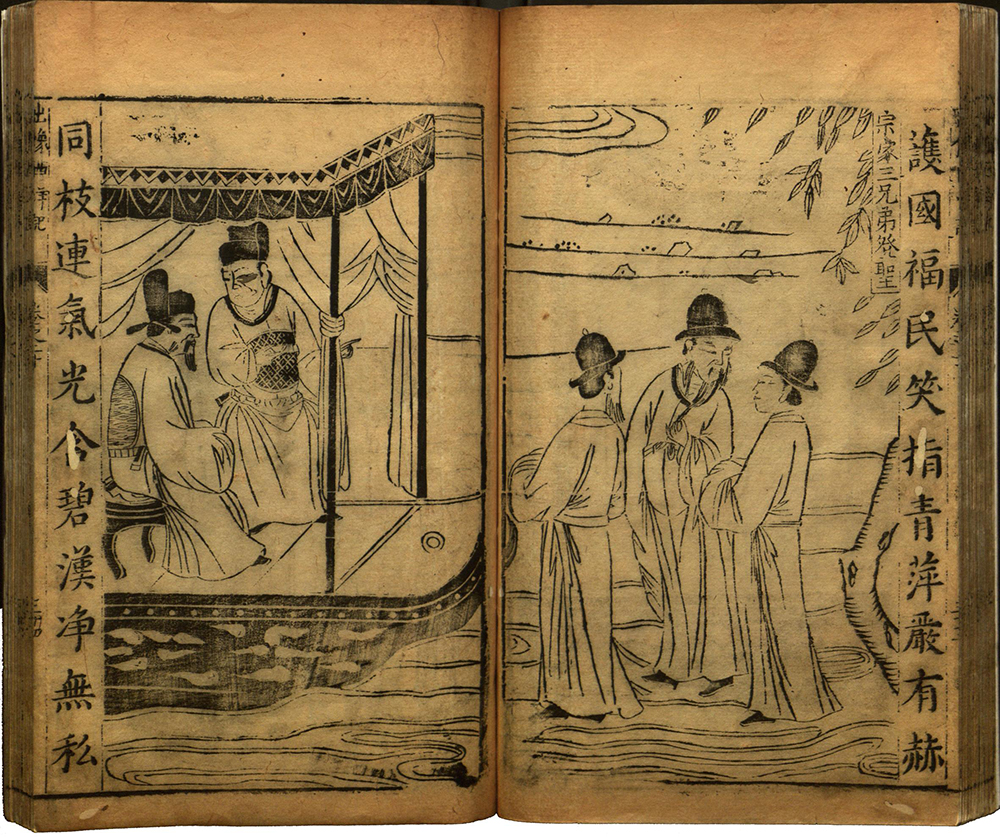

Another illustration in Chronicle of Eunuch San-pao’s Voyages to the Western Seas by Lo Mao-teng. Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

The motives behind the several sea expeditions of Cheng Ho were given in the official biography of our Grand Eunuch as “Emperor Yung Lo strongly suspected that the deposed Emperor Hui Ti had taken refuge somewhere overseas and it was the desire of the new ruler to track him down. Moreover, it was also Yung Lo’s ambition to make a good show abroad of his military might and economic power …… ” Such justifications were only written up to support later events and developments, because during early Ming times, military requirements in north-western territories had high urgency and priority.

During the reign of the first emperor of Ming, cabinet ministers were ordered to waive the usual tri-annual homage visits from Annam and Siam, and replace this tradition by an official courtesy visit upon the succession of every new ruler of these vassal states. This Royal Decree was promulgated in the Seventh Year of Reign and was despatched to every vassal country concerned. This proved that the early Ming Court had no aggressive designs regarding these smaller countries; therefore Cheng Ho’s first sea expedition was not a sabre rattling demonstration. Perhaps, the only purpose was to try and locate the escaped deposed Emperor. After the first voyage, the succeeding ones could have been mainly for the spreading of Chinese culture, assisting the island nations in development, and the teaching of agricultural and manual arts. In defense and reconstruction, Cheng Ho also gave a lot of aid in contributing experience and knowhow to these countries.

According to folklore, Cheng Ho’s first voyage was composed of about 27,800 men. His standard ships were 440 chih (feet) long and 180 chih (feet) wide. There were 62 of these main vessels. The subsequent voyages were composed of slightly different numbers in men and ships, but general technicians and tools were gradually increased. Smaller ships of various sizes also accompanied the armadas.

Another illustration in Chronicle of Eunuch San-pao’s Voyages to the Western Seas by Lo Mao-teng. Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

According to available records (as reported by Feng Cheng Chun’s research), his seven expeditions took place in the following dates:

First Expedition: From the 6th month of 1405 to the 9th month of 1407.

Second Expedition: From the 9th month of 1407 to 1409.

Third Expedition: 1409 to 1411.

Fourth Expedition: From the 11th month of 1412 to the 7th month of 1415.

Fifth Expedition: From the 12th month of 1416 to the 7th month of 1419.

Sixth Expedition: From the 1st month of 1421 to the 8th month of 1422.

Seventh Expedition: From the 12th month of 1430 to the 7th month of 1433.

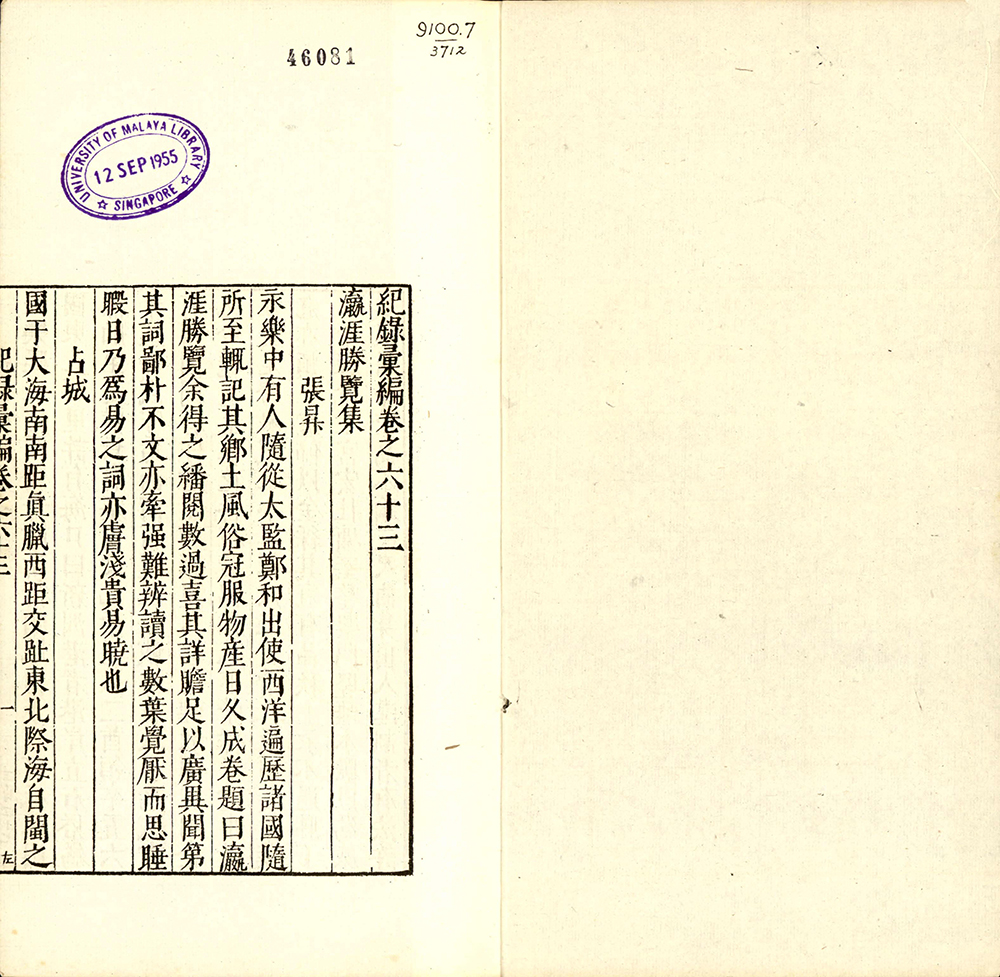

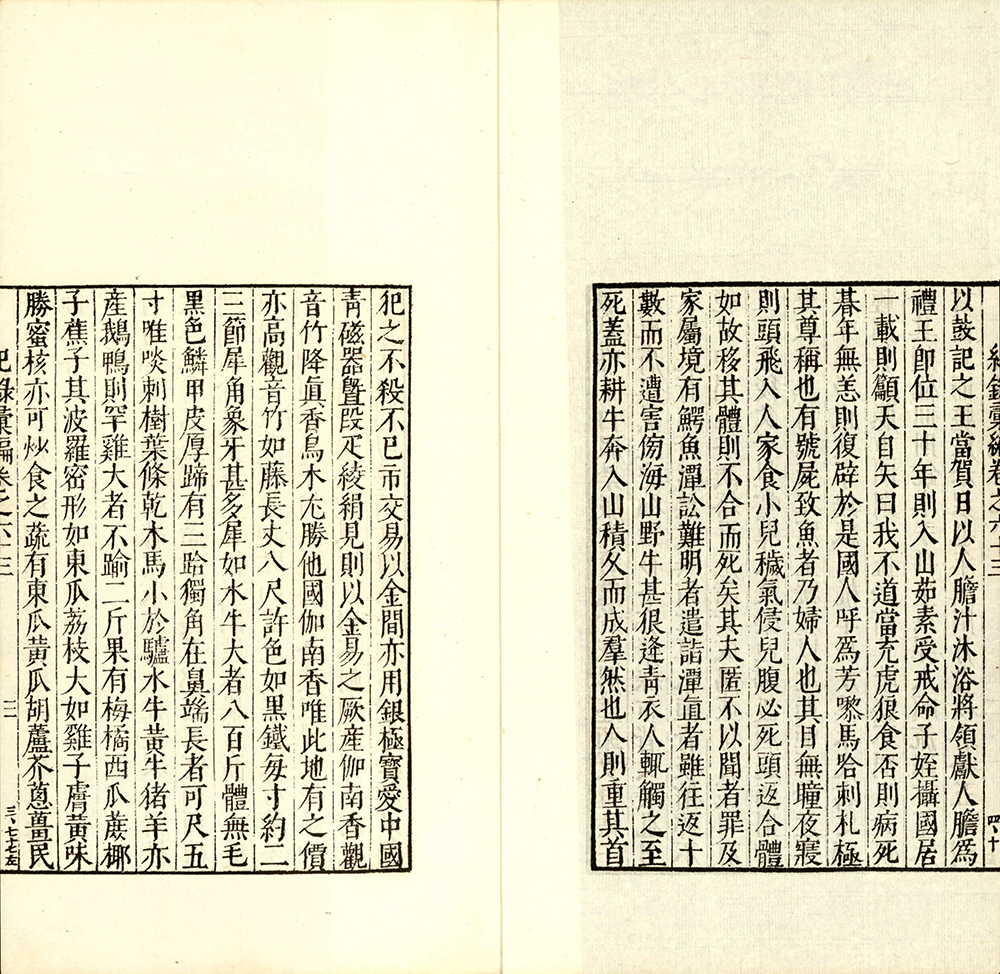

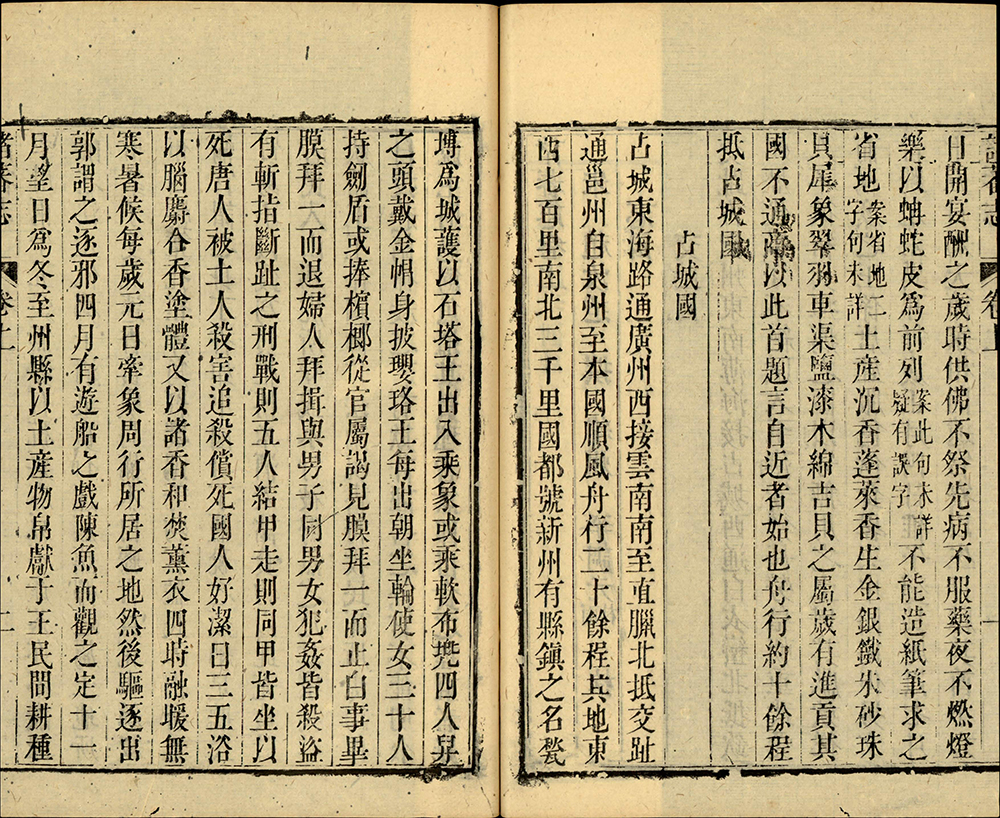

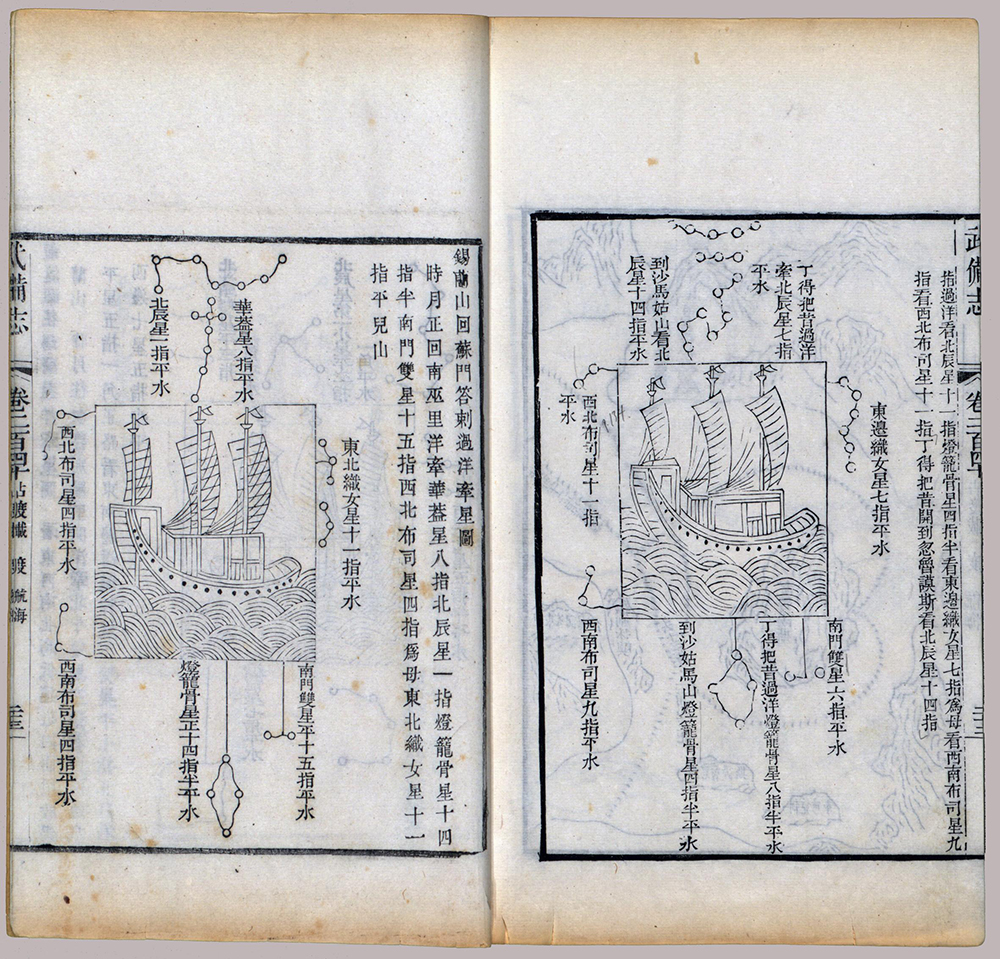

First page of Encyclopedia of the Archipelagoes. Photograph courtesy National University of Singapore Library

Second page of Encyclopedia of the Archipelagoes. Photograph courtesy National University of Singapore Library

Third page of Encyclopedia of the Archipelagoes. Photograph courtesy National University of Singapore Library

According to the Ming Annals, the Encyclopedia of the Archipelagoes reported the composition of the Third Expedition of Cheng Ho as:

63 master vessels with 444 chih (feet) length and 180 chih (feet) width and 370 chih (feet) length and 150 chih (feet) width.

The fleet had a complement of officers, flag or signal officers, combat troops, interpreters, carriers, purchase petty officers, scribes etc. totalling 27,670. There were 868 officers, 26,800 troops, 93 commanders, 2 group commanders, 104 first grade civil administrative officials, 403 second grade civil administrative officials, 1 chief surgeon, 1 soothsayer, 1 announcer, 2 supervisors, 180 medical officers and nurses, 2 assistants, 7 gazetted eunuchs, 5 adjutants, 10 junior adjutants, 53 domestic superintendents.

The great Cheng Ho was nicknamed San Pao and was known as the Grand Eunuch San Pao. He left many relics and records in southeast Asia.

The above historical sketch, augmented by my novel Grand Eunuch San Pao published in the magazine Spring Autumn (Hong kong, 1959) forms the basis of the movie scenario now being presented for commentaries. Historical facts are there, but the construction and plot are partly my own.

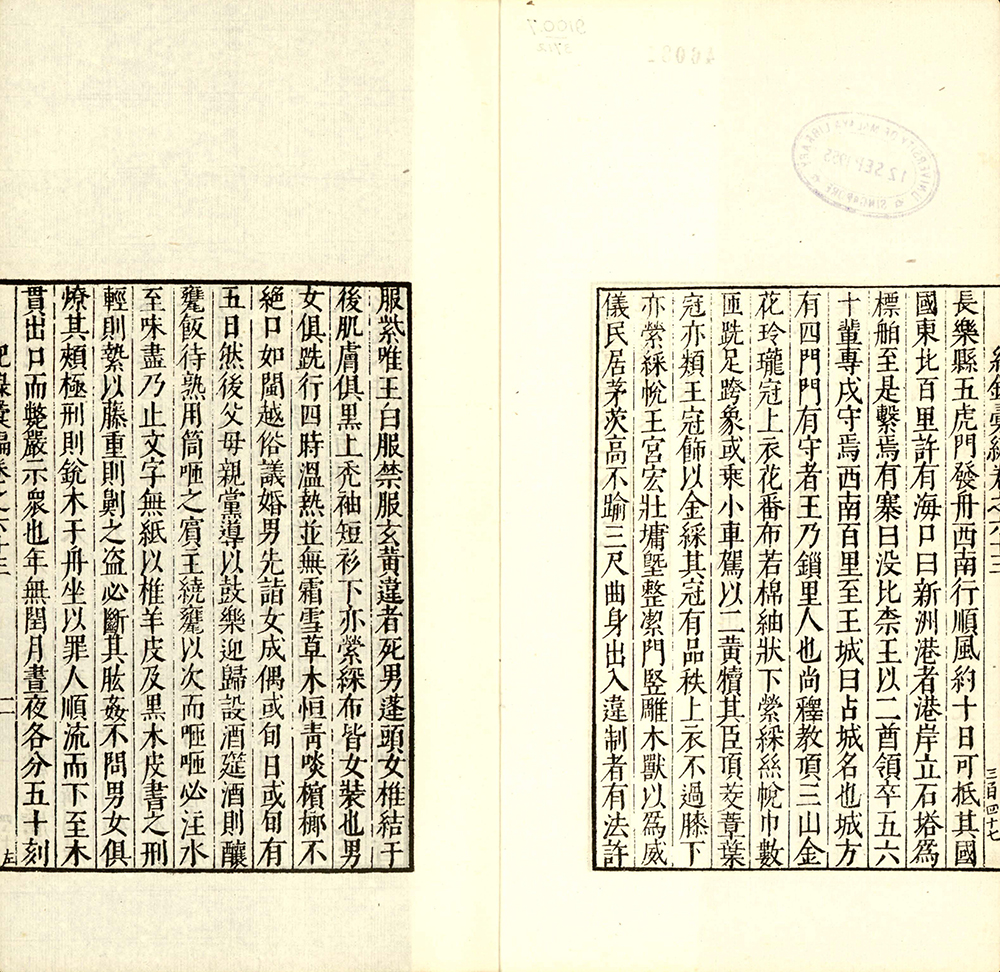

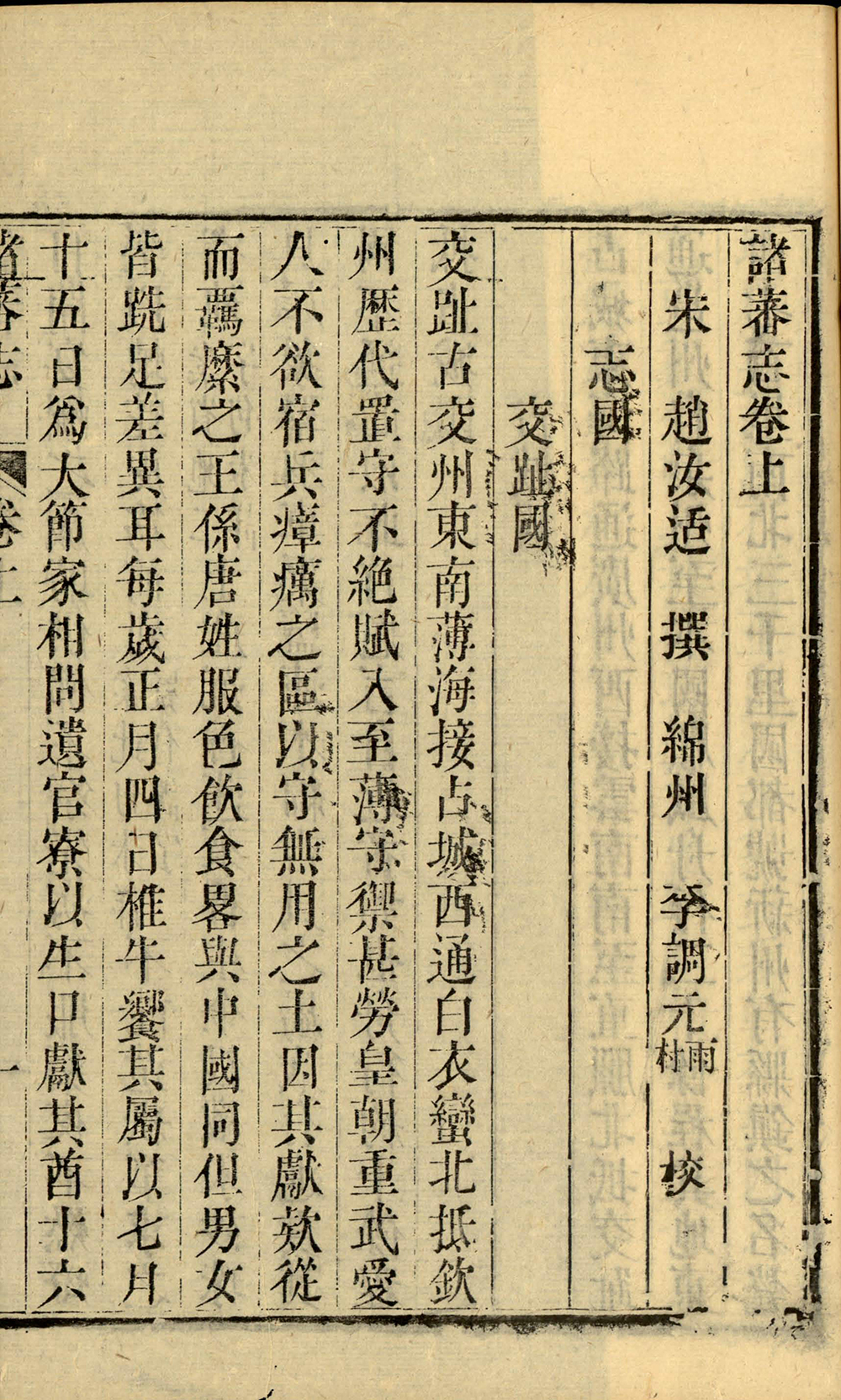

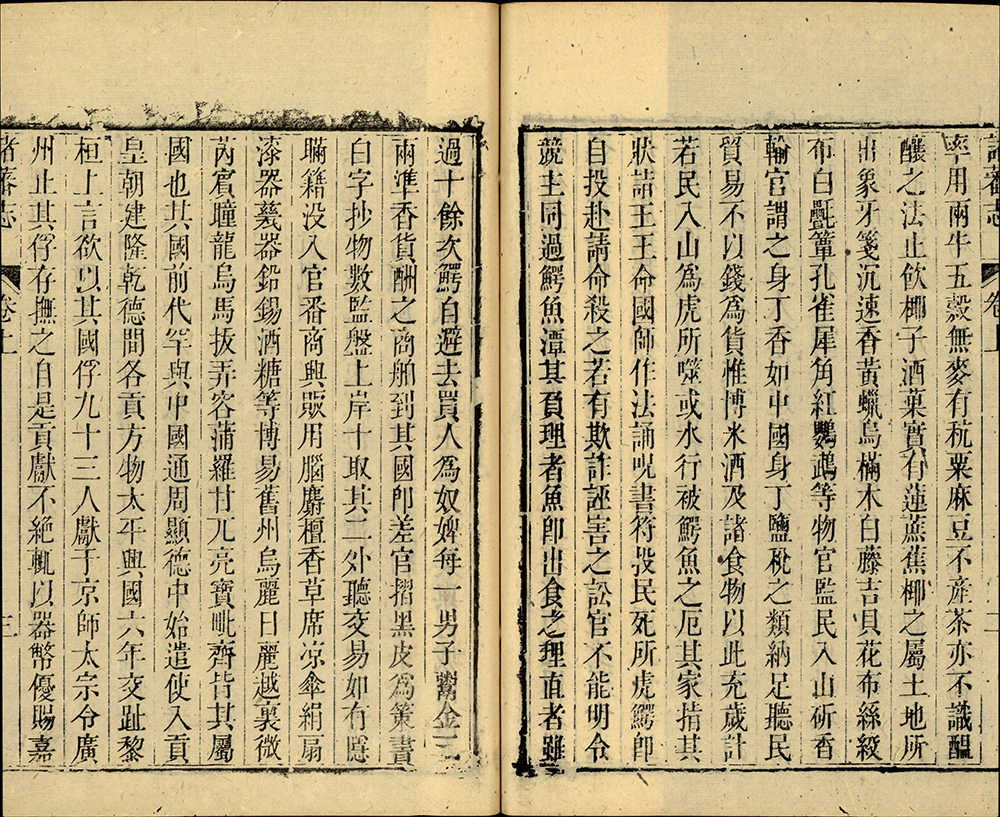

First page of All Tribe Tales. Photograph courtesy National University of Singapore Library

Second page of All Tribe Tales. Photograph courtesy National University of Singapore Library

Third page of All Tribe Tales. Photograph courtesy National University of Singapore Library

The character of Sultana of Tunhindu is a composition personality made up from notes found in the annals of Island Tribes and All Tribe Tales. I have named her Malayar- but she could be entirely fictitious. But according to folklore of Annam and Borneo, it was said that Emperor Chien Wen’s descendents had continued to live in the south seas. Such tales were also found in the writings published in the Chien Lung and Chia Ching periods of the late Ching Dynasty.

Forenote by the author

Nan Kung Po

Translated by Sherman Wang

Movie Scenario of ADMIRAL CHEN (CHENG) HO

Chinese Text by Nan Kung Po. Translated by Sherman Wang.

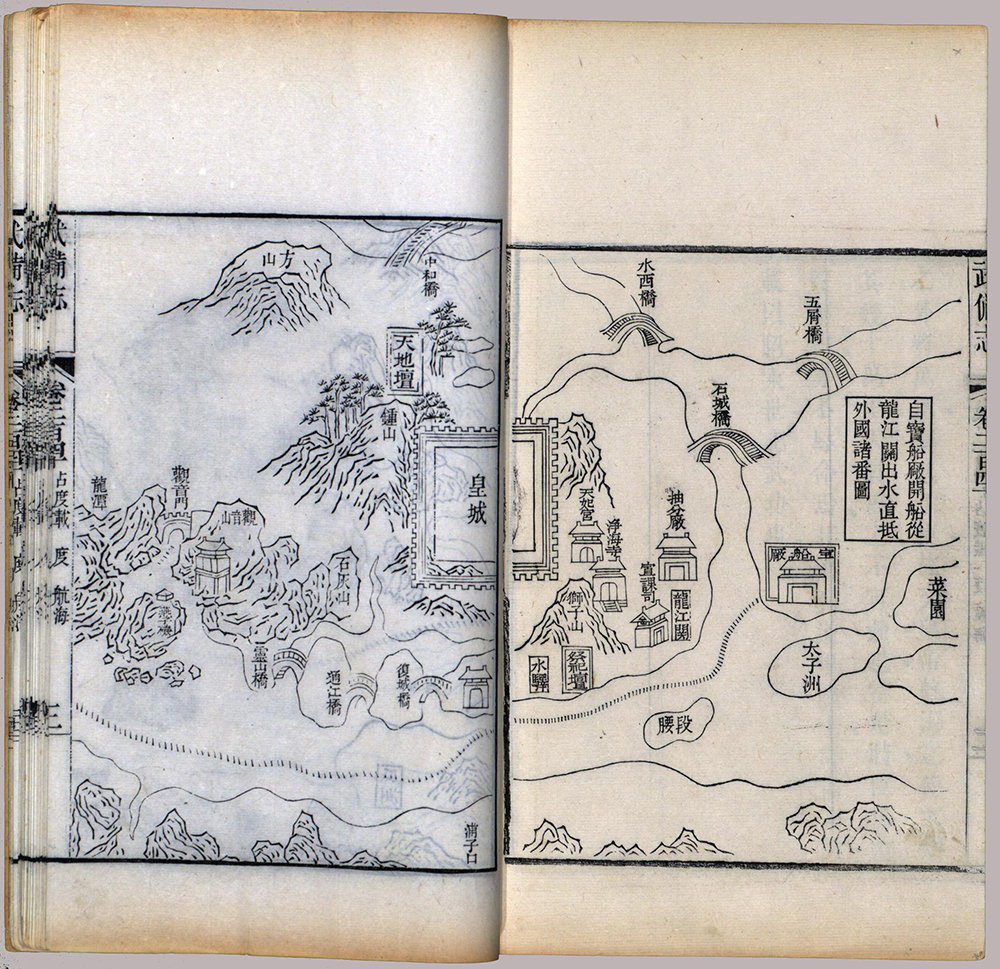

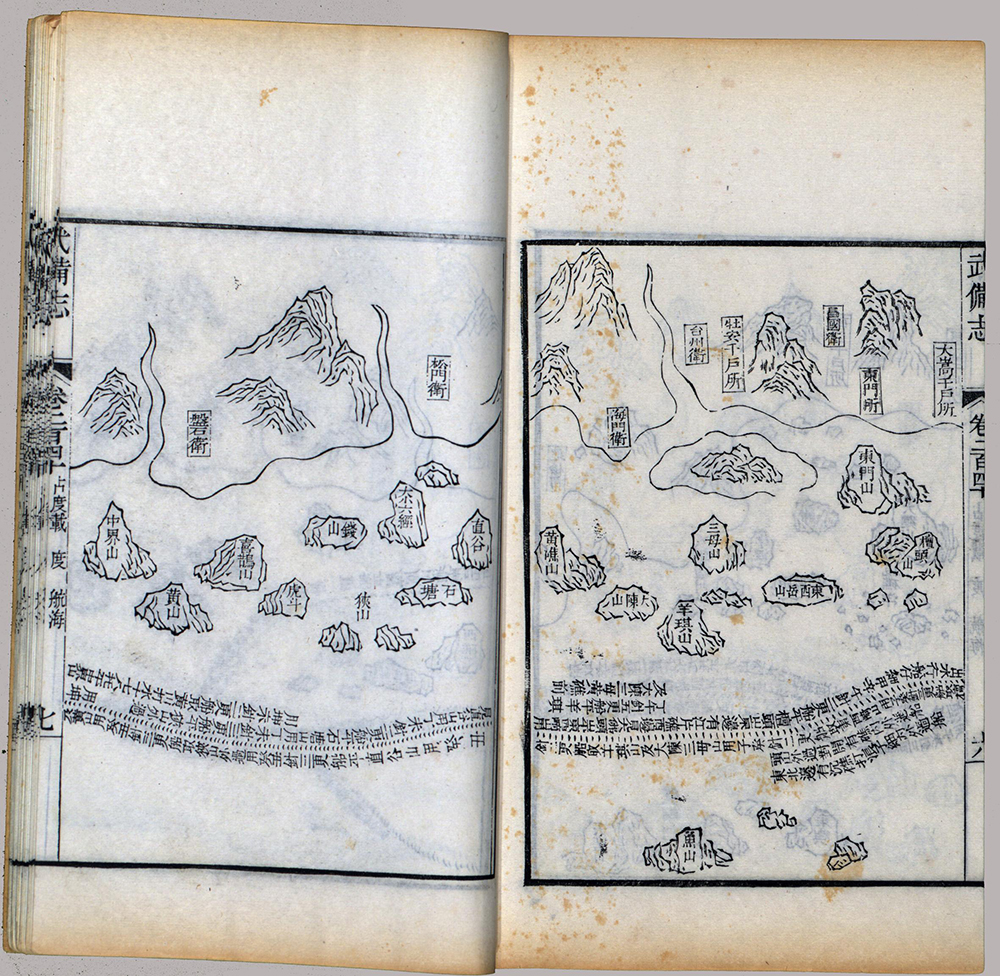

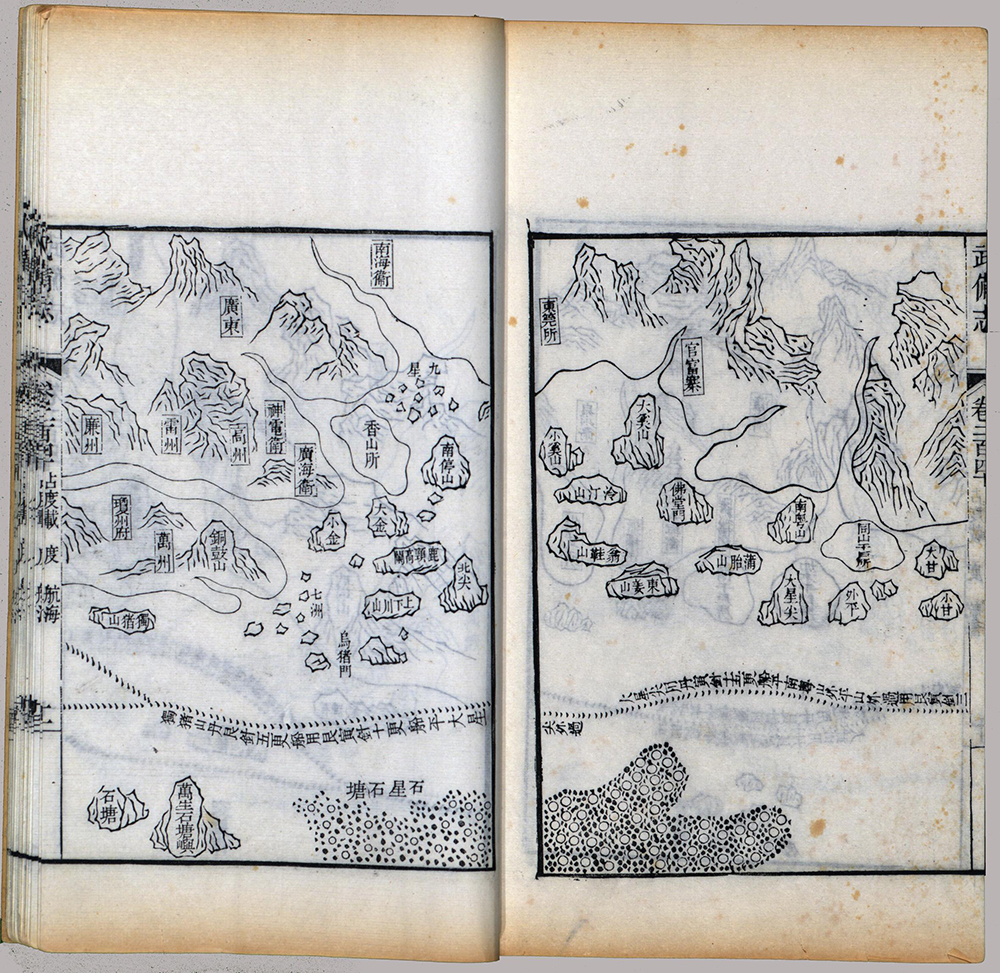

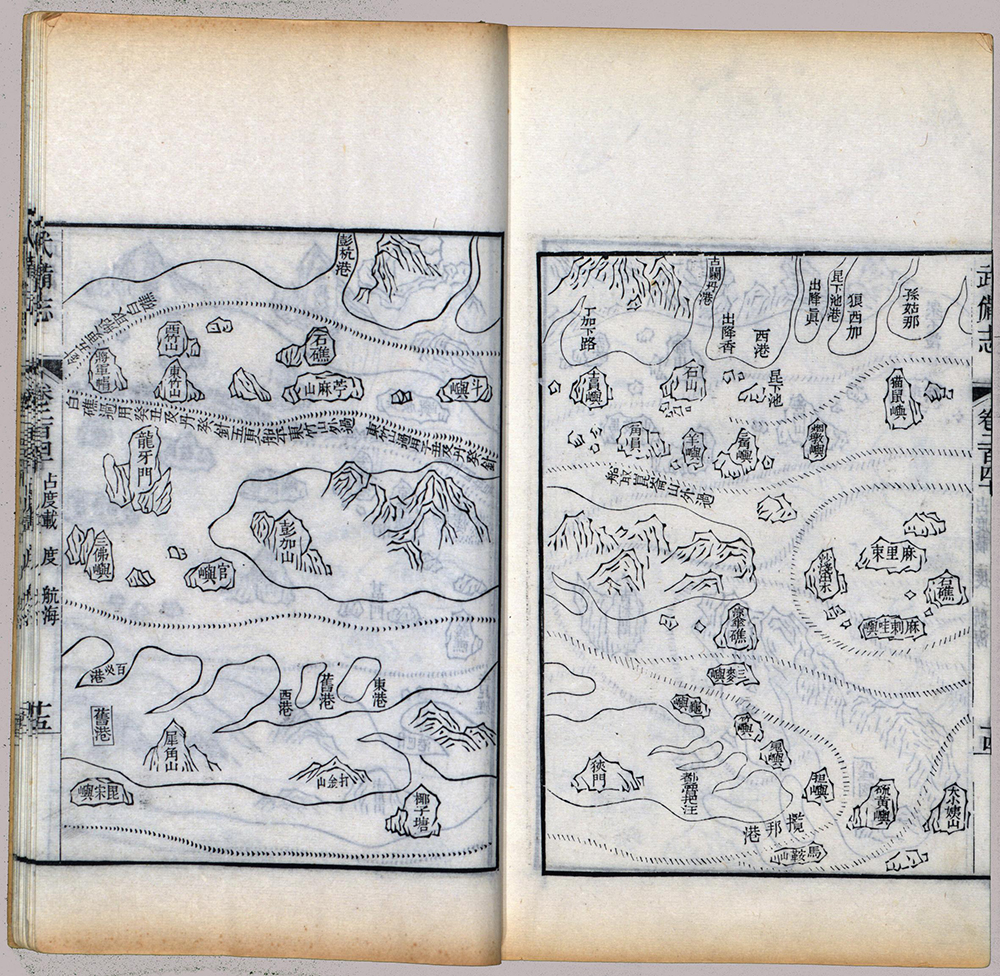

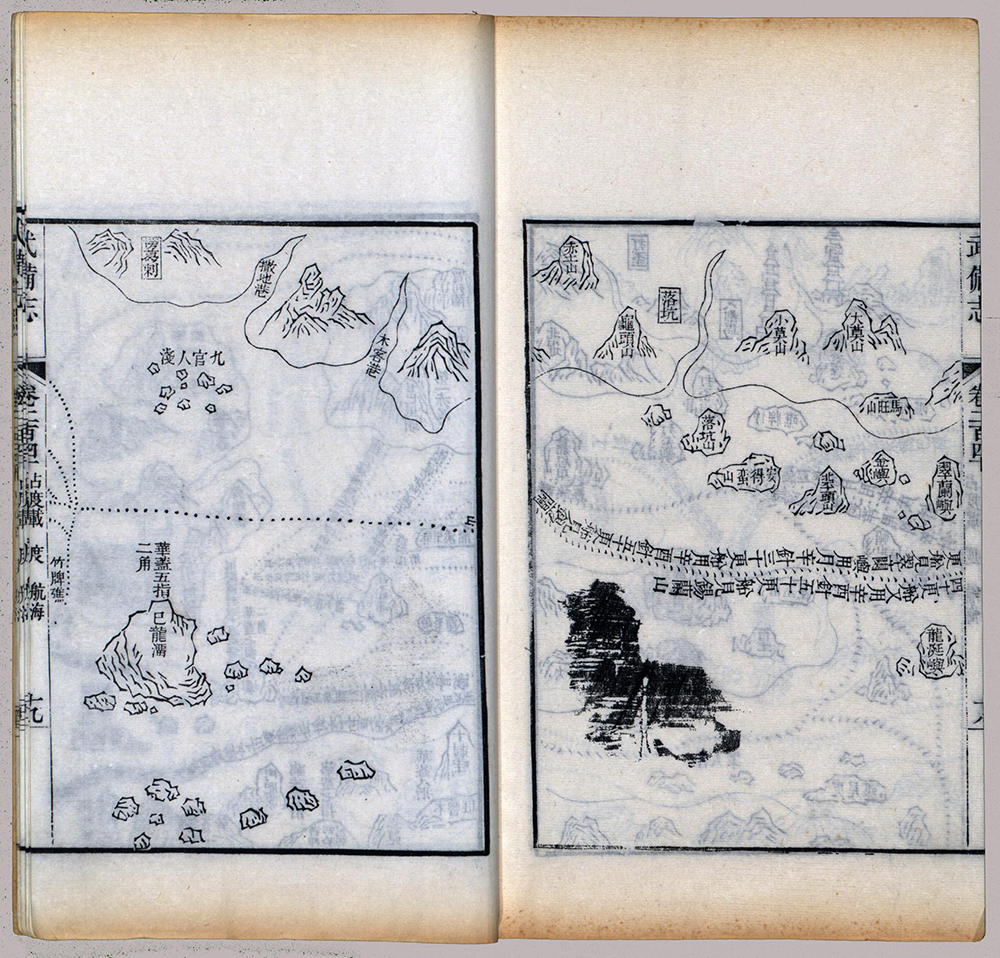

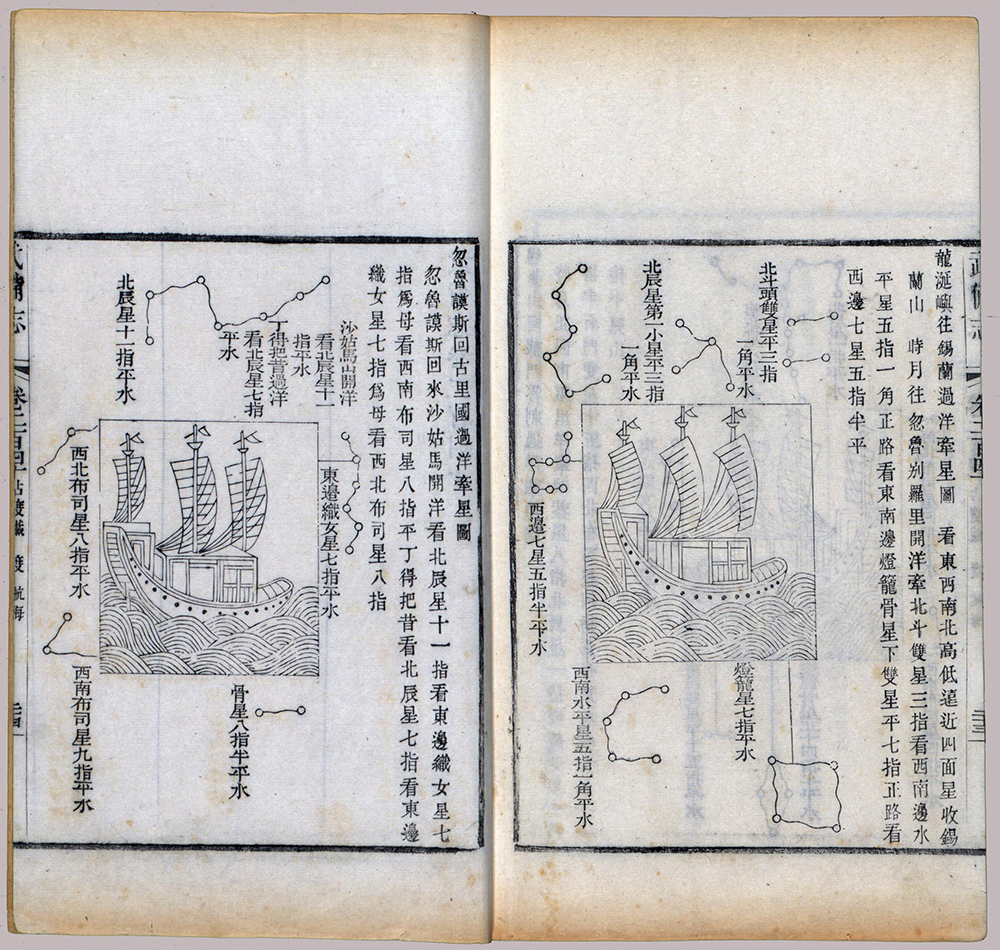

Illustration 1 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 1

The scene is the southern part of China, in a promontory of South Sea, there is a small fishing village.

It is night. A young monk hurriedly runs from the fishing village toward the beach. He is followed by two males and then another female who very lightly follows and is chasing the group. There is a small boat on the beach. Two other men are pushing the boat from the shallows. One of the men turns back and carries this young monk aboard. All of them call the monk “Your Holiness”.

Finally the young girl wades toward the side of the boat and asks to be taken aboard. The monk says no, but the young girl insists and pleads and says she knows the waters and currents of this part of the sea and could be a good pilot. Finally, among distant barkings of village dogs of the night the young girl is also taken aboard.

This little boat is gradually lost in the darkness of the sea. The fishing village, among noises made by men and dogs, is lit and burned.

NARRATOR: This young monk is none other than the escaping emperor of Ming who lost his throne to his uncle. His followers got the intelligence that the conquering soldiers were hard after them and hence advised him to take to the sea for escape. The young girl is a local pearl diver and is an orphan.

Emperor Chien Wen thereupon accepts her and makes her his lady in waiting. But here, Emperor Chien Wen is only known as Abbot Ying Wen. His only followers who were cabinet ministers before, are Chen Chi who is camouflaged in a Taoist robe and is known as Taoist Chi. A former Court Prosecutioner by the name of Yeh Hsi Hsien has now shaved his hair and become a monk by the name of Ying Hsien. The Emperor’s tutor, Yang Chien Neng is also disguised as a monk by the name of Ying Neng.

Beside these, there are thousands of others abroad trying to help the dethroned emperor and trying to stage a comeback from every part of the country for a restoration.

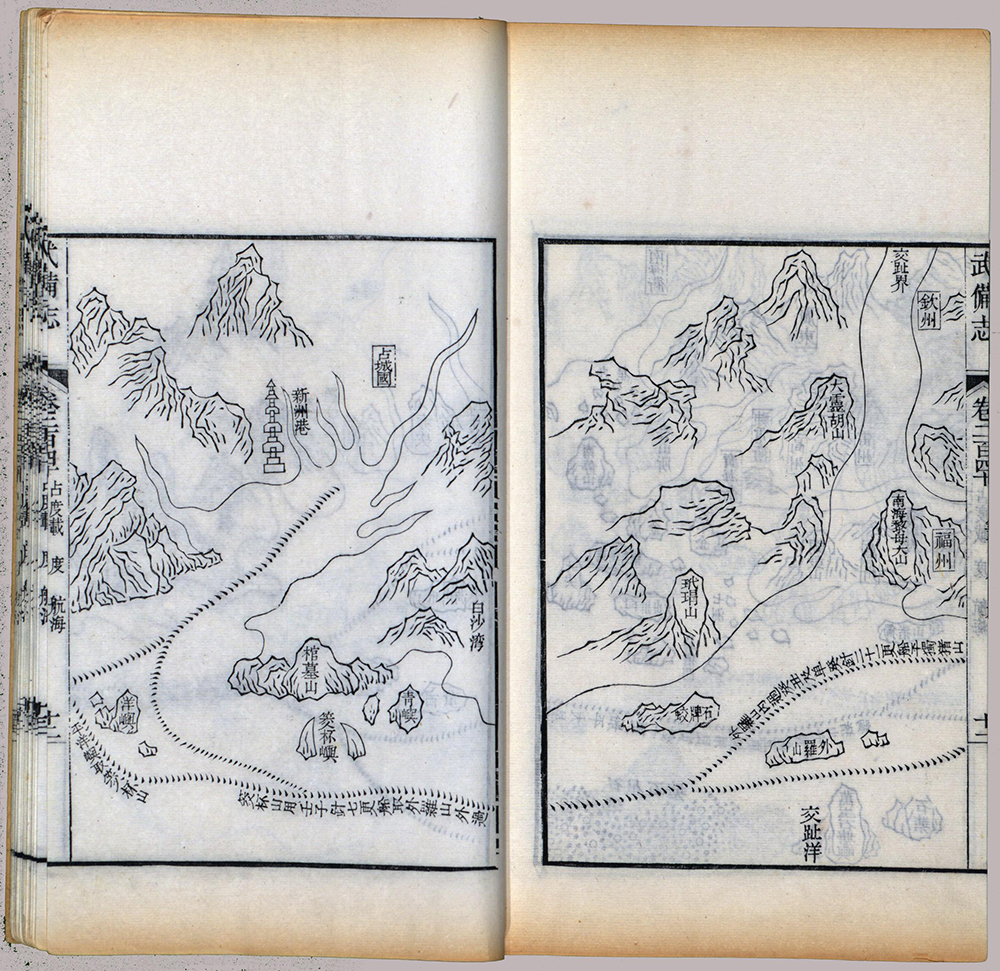

Illustration 2 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 2

Now in Nanking, Emperor Yung Lo calls two of his eunuch chamberlains in audience. Cheng Ho and Wang Ching Hung. Emperor Yung Lo tells them that the deposed Chien Wen is escaping overseas trying to ally with the barbarians on the islands trying for a restoration. Emperor Yung Lo gives secret orders to Cheng Ho to build a giant fleet to go to the seas and try to find and capture the ex-Emperor Chien Wen. At the same time, to reconnaitre and to make contact in the South Seas and westwards with the island countries. This mission is to be called a Pacification Mission.

The Emperor appoints Cheng Ho to be the Royal Pacification Envoy and Wang Chin Hung his deputy.

Scene 3

At Liu’s Harbour, Tai Tsang Hsien, of Kiangsu province.

A huge naval fleet unseen and unheard of in history, at the break of dawn, sails out of the harbour.

Sixty three giant vessels at the first beam of sunrise, take full sail and glide from the East Sea southward.

On board at the mast head of the flag ship of the Chief Royal Pacification Envoy is flown the Royal flag of Ming and horns and drums are in full blast.

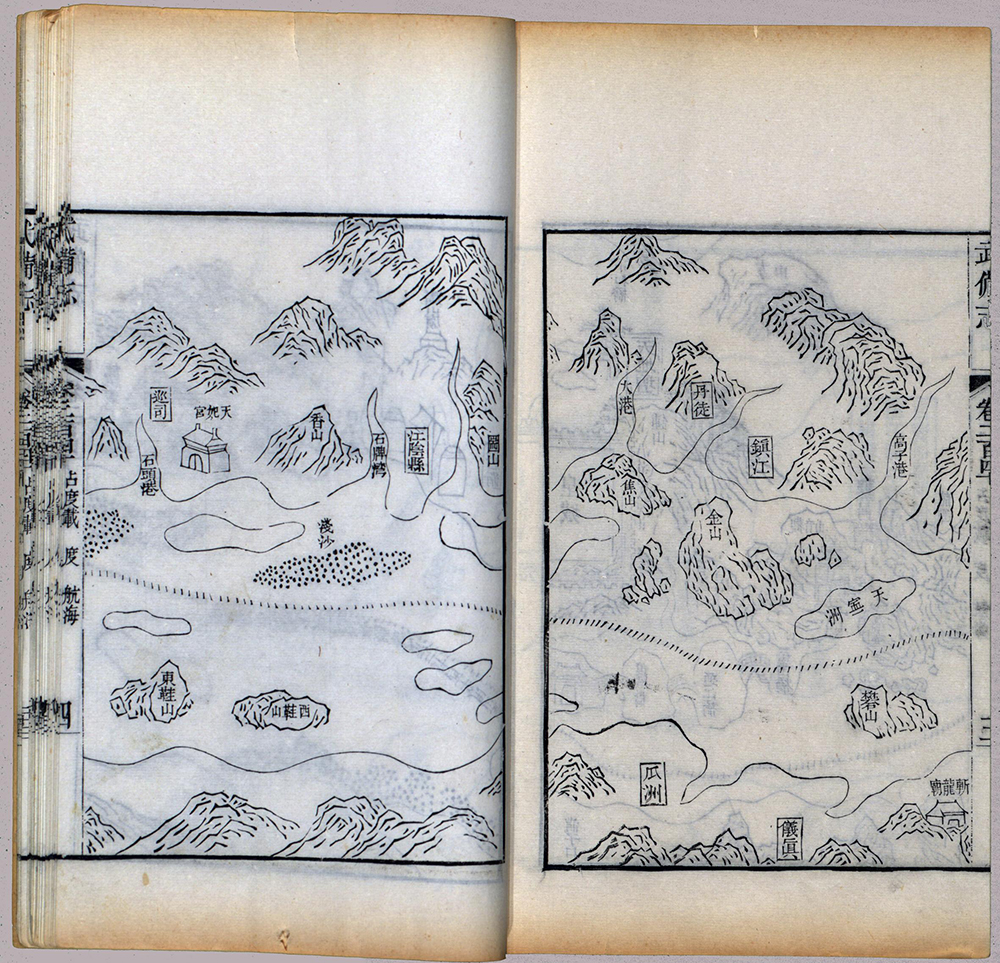

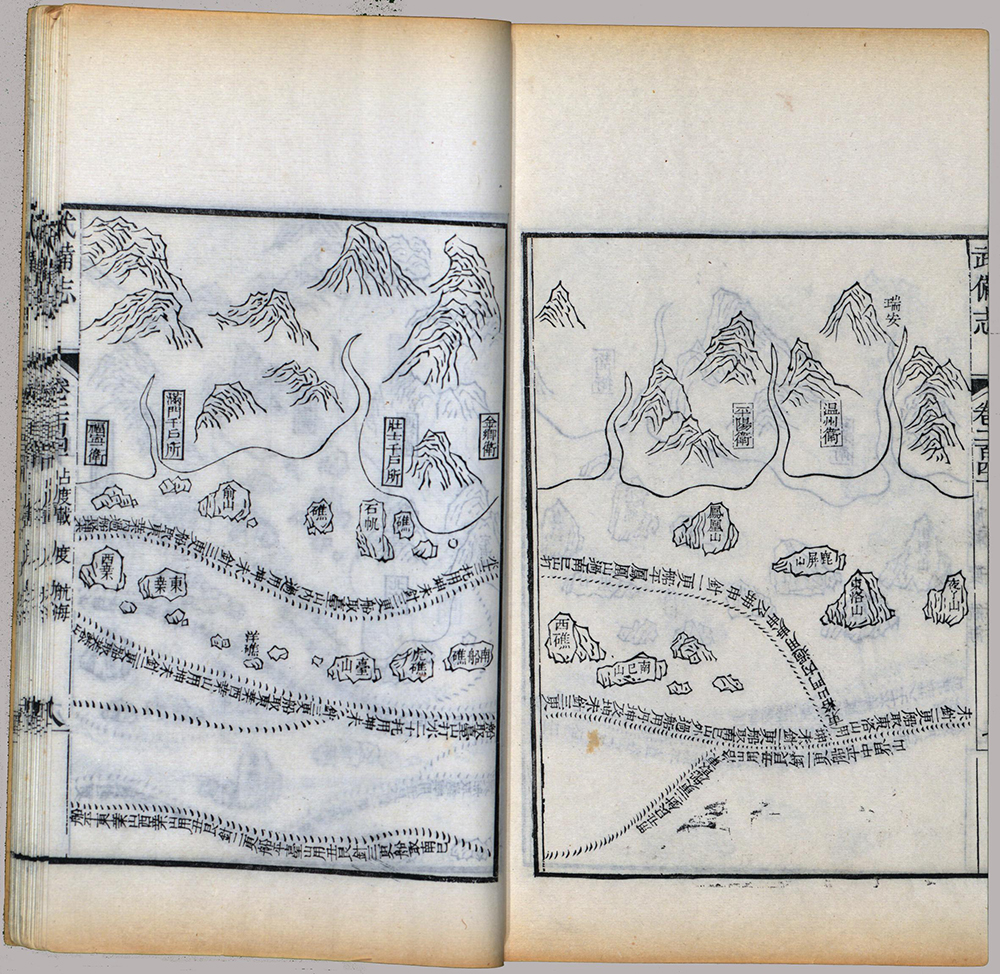

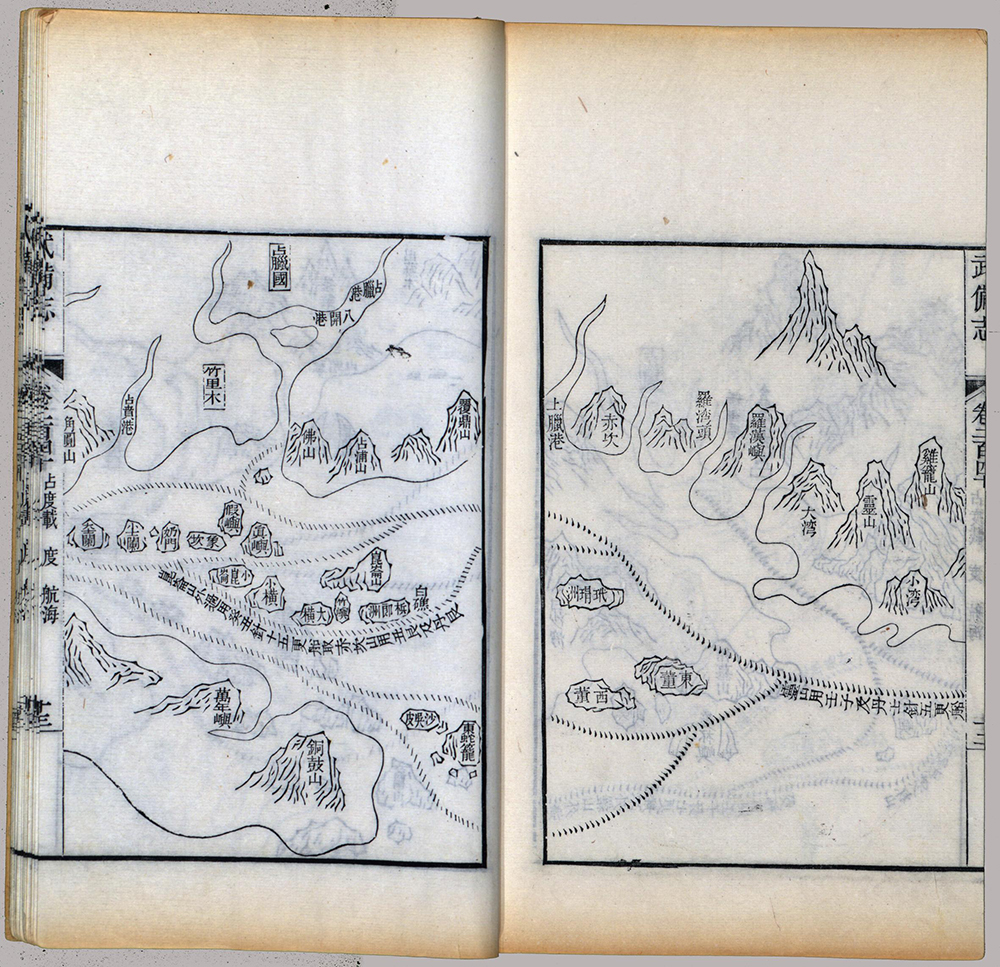

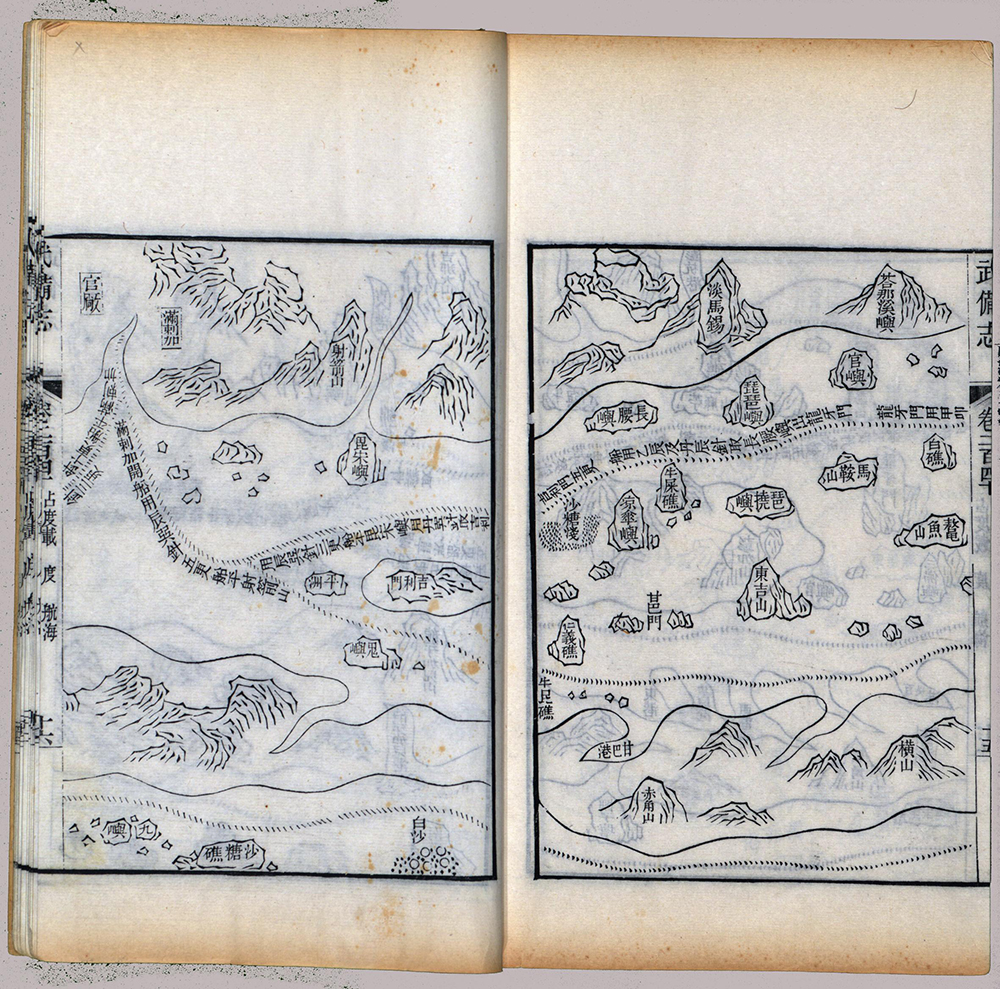

Illustration 3 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 4

The royal fleet is seen sailing in formation on the high seas.

Most of the land based soldiers become sea-sick on account of wind and waves. In ten days, more than three thousand men are bed-ridden.

Chief Envoy Cheng Ho leads his medical officers and goes around to visit the sick. The sea-sick number more and more. Deputy Envoy Wang Ching Hung thinks that to go to the western oceans could not be achieved, therefore he suggests to turn sail and return to land. Chief Envoy Cheng Ho however determinedly and insistently maintains that the mission accomplishes its purpose of a pacification visit to the western countries. He insisted that for those who became seasick, a little experience and time would accustom them to the life on the high seas.

Cheng Ho’s stubbornness shows results. When the giant fleet reaches the Five Tiger Gate of Changlo Hsien of Fukien Province for supplies, there are only and scarcely one hunderd seasick soldiers.

At Five Tiger Gate, the fleet is provisioned and they wait for fair winds to start on their long journey.

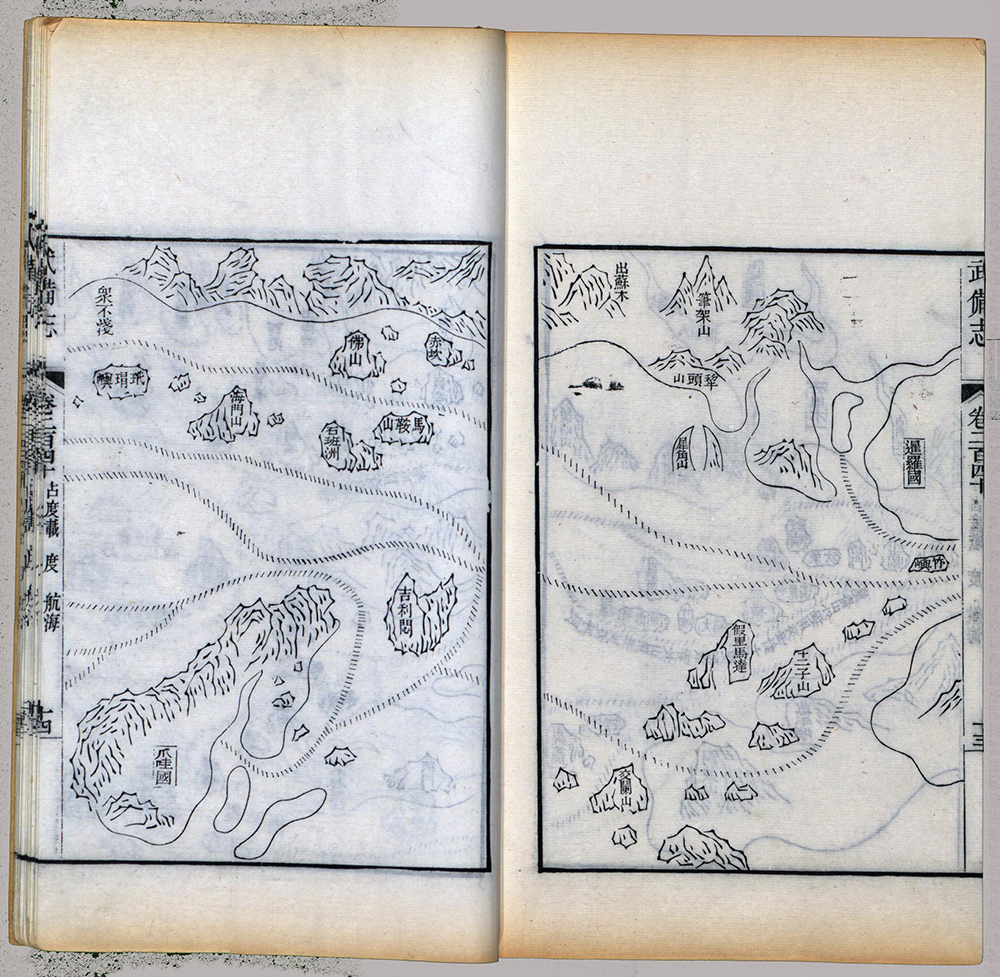

Illustration 4 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 5

The fleet meets with enormous storms on the high seas. The sea, the ocean, is boiling over. The weather-men and old time sailors, already knowing the coming of the storm, have sailed the ships away from the frontal attacks of winds and waves. The winds are so strong that they inflict heavy damages to the vessels, therefore the fleet selects a leeward shore of an island to stay away from the storm. Chief Envoy Cheng Ho as a very brave commander, directs the Fleet from his ship. Two main vessels collide and break up. The Chief Envoy’s launch is also overturned but is salvaged by the sailors.

More than ten other vessels suffer various degrees of damage.

Scene 6

After the storm calmed down the Chief Envoy Cheng Ho orders the fleet to anchor by an uninhabited island for repairs. He commands artisans to repaint the vessels because he wants the fleet to look bright and fresh when he reaches the countries of the western oceans.

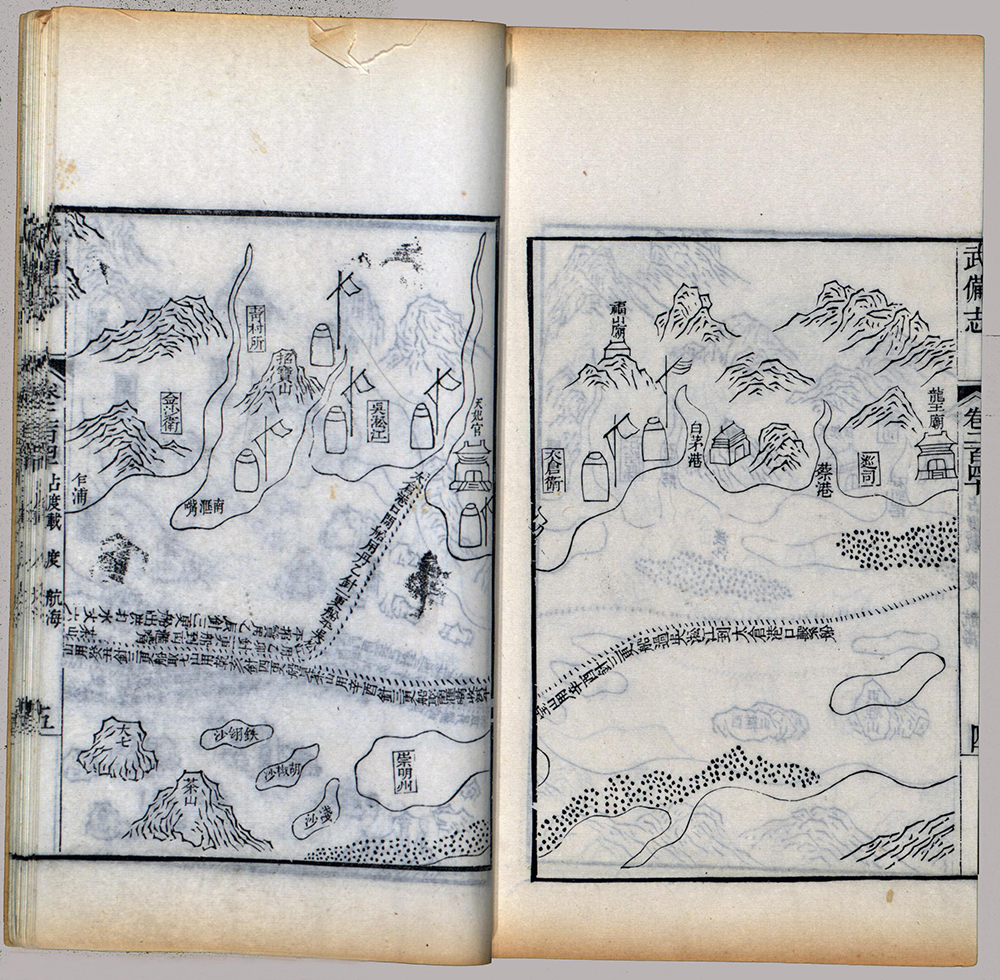

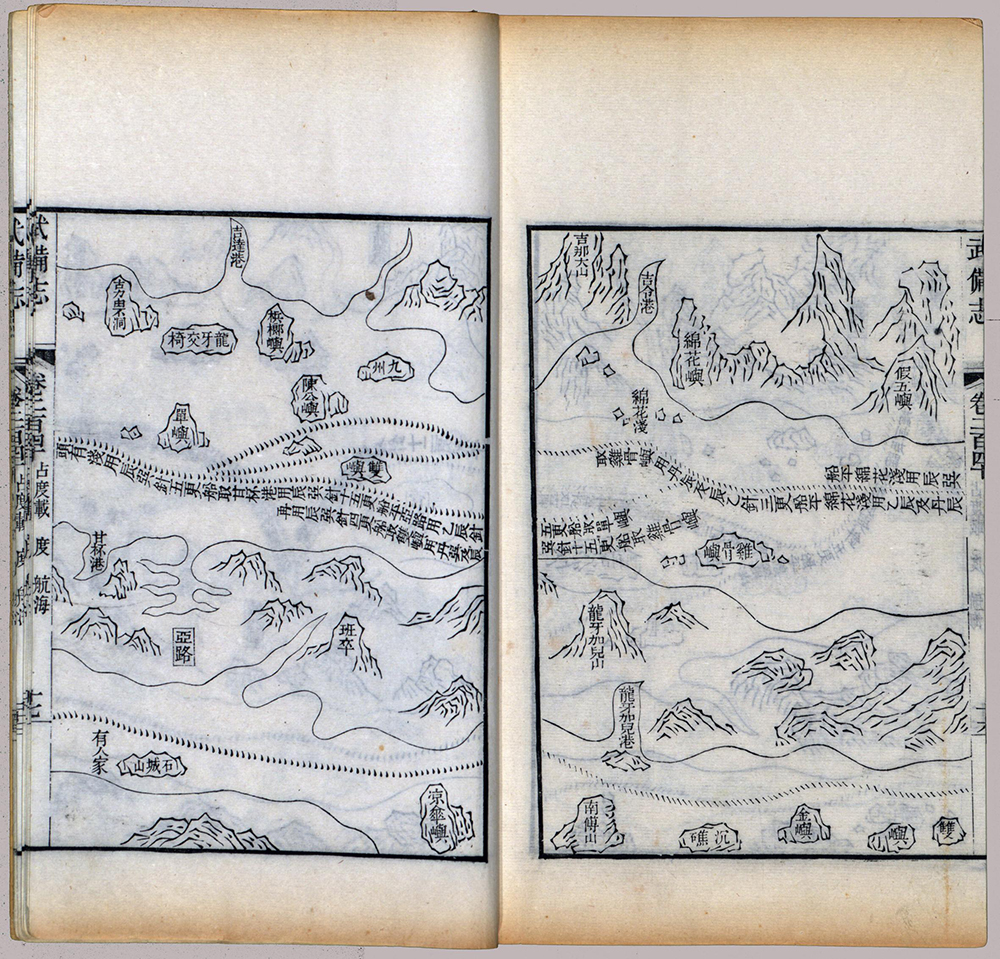

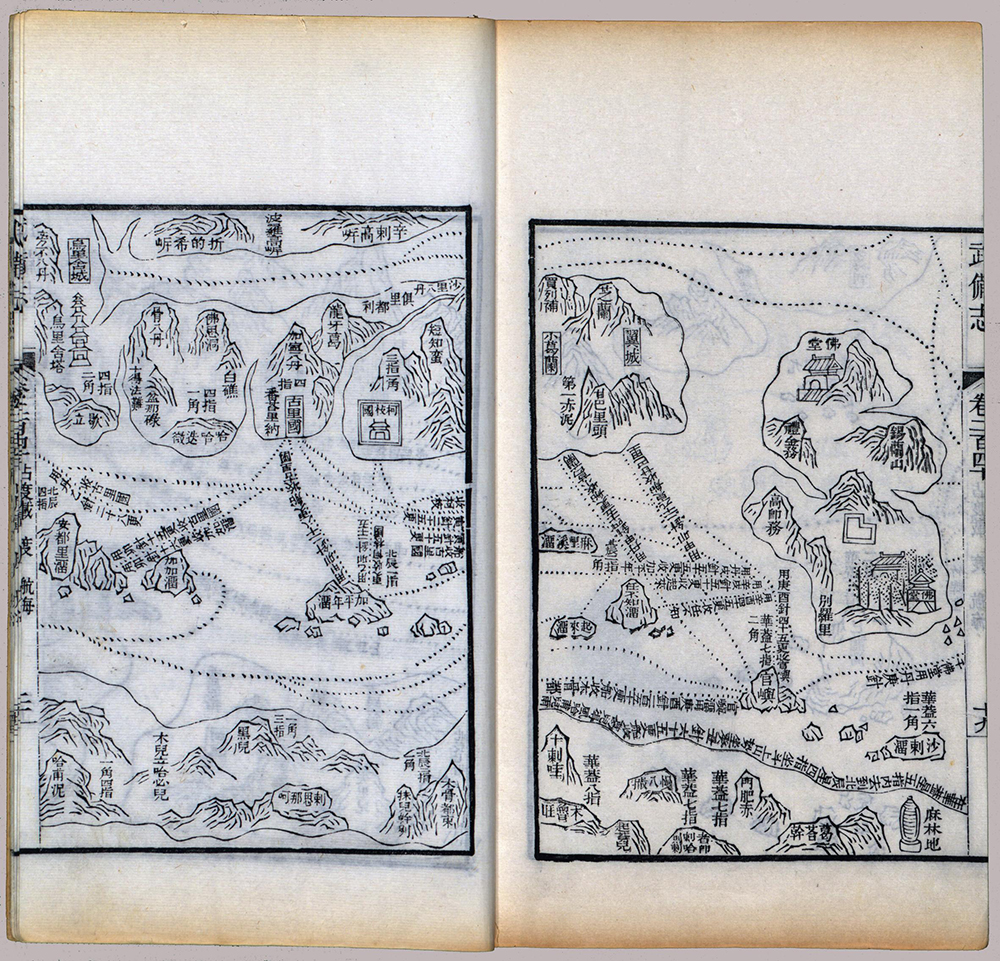

Illustration 5 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 7

Finally the Pacification Fleet arrives at the country of Jianchin and enters the harbour of Sincheow. (Jianchin is in modern Vietnam and northeast of Saigon. Jianchin had contact and traded with China from early times. During the Chin Dynasty it was a district of China. Afterwards, it became an independent country; however, it remained a vassal state of China.)

The army then lands and establishes camp at Sincheow harbour. Chief Envoy Cheng Ho is warmly and courteously received by the Prince of Jianchin, who received Chinese silk and many other utensils from the great country of China.

The Prince of Jianchin welcomes the Royal Envoy and his entourage with a procession of forty elephants marching from the harbour to the capital.

According to ancient lore, Jianchin is a favorite haven of deposed emperors and princes. However, according to the followers of the Royal Envoy, the deposed Emperor they were looking for has left Jianchin already.

Cheng Ho’s diplomacy wins over the Prince of Jianchin who becomes friendly toward China. He promises to send an ambassador with gifts and pay tribute to Emperor Yung Lo of China.

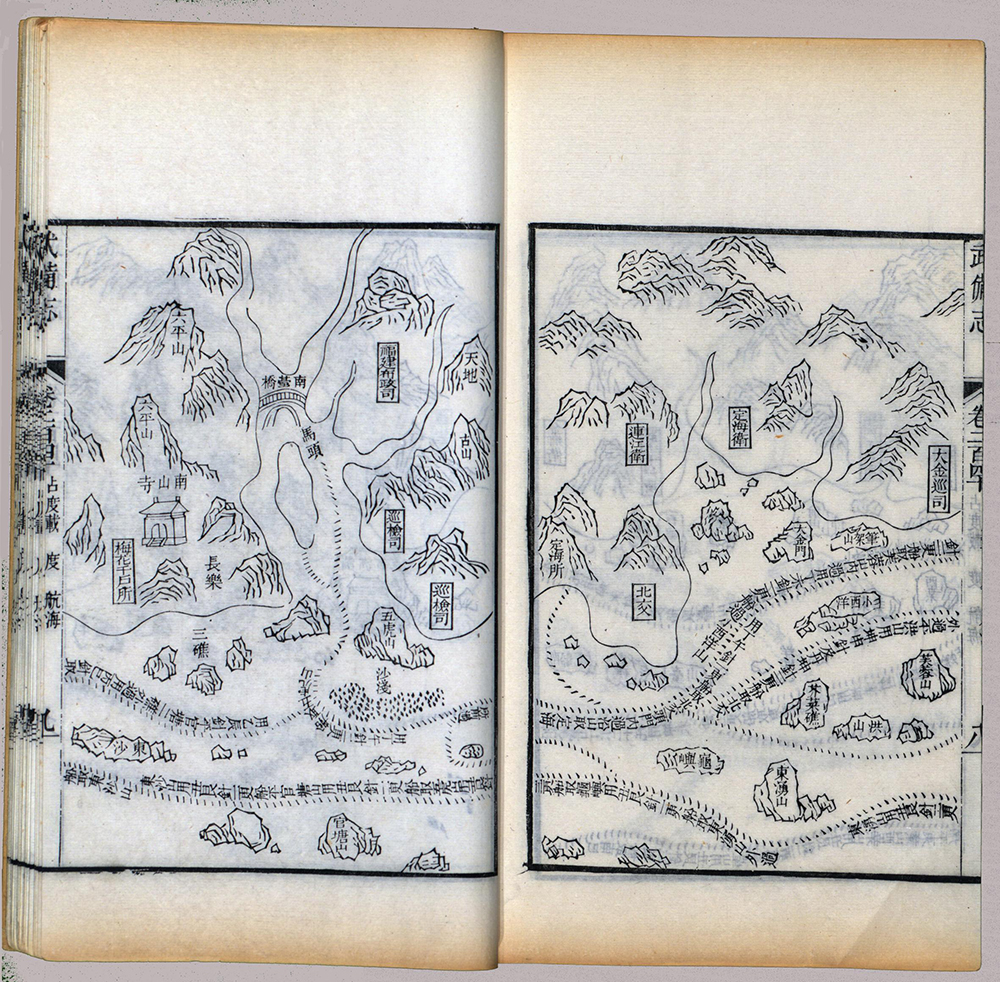

Illustration 6 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 8

The great fleet next arrives at Bintonlon. Again Envoy Cheng Ho and his men are warmly welcomed. In Bintonlon there is supposed to be an evil apparition who is said to disturb the peace and quiet of the Island. Cheng Ho pacifes the people mentally and psychologically and allays their fears. He orders the people of Bintonlon to wear a white turban on their heads thus repelling the apparition. The white turban becomes a tradition and emblem of this country.

Scene 9

The great Ming Armada passes many smaller countries and arrives at the rich and well-known country of Siam.

The Ming Pacification Mission stays at the capital of Siam. Cheng Ho visits and prays at the local temples, and meets with the scholars of the Siamese capital. He presents many books and tablets, pens, and other stationery to the local people; he also gives the Siamese large quantities of medicine to ward off heat prostration and jungle fevers.

In Siam, Cheng Ho enjoys and is entertained with special local dances because during the dynasties of Tang and Sung, these dances were introduced to China and are very very popular.

In Siam, one of the Mission’s men named Hang Ping finally gets news of the exiled Emperor. For the deposed Emperor and his men not long ago have moved south, a nominal area of Siam but in fact they are under several sultanates and are all uncivilized.

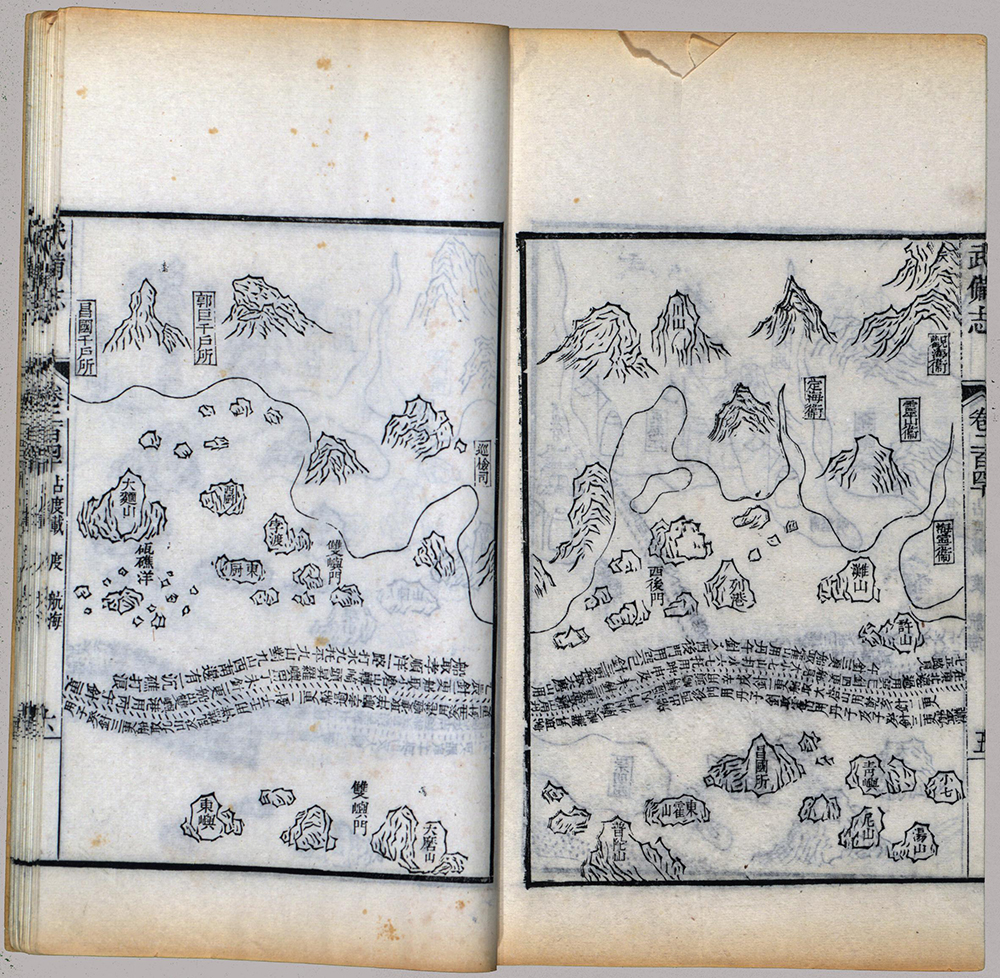

Illustration 7 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 10

To perform his duties, Cheng Ho borrows from the King of Siam twenty elephants and one hundred soldiers as forerunners. He himself, with a major and one interpreter and three hundred soldiers, brings along fifty shot guns and twenty matchlocks. They travel by land. He orders Wang Chung Hung to take the sea route slowly off shore around the Bay of Siam.

The caravan, passing through jungles, meet poisonous snakes, crocodiles and animals, but are safely protected by their superior weapons.

Scene 11

The land caravan passes through a place called Bampu where the sultan orders his men to attack the Royal Envoy and his men. The skirmish ends with the sultan’s defeat and Cheng Ho quickly wards off the attack. However, on the second day, they meet bigger and stronger forces from Bampu, blocking the pass where the caravan must go through. Cheng Ho then sends an interpreter, a Cantonese by the name of Pai Lung Chi to negotiate with the local sultan.

At that time, the sultan of Bampu is gravely ill. The tribe is just about to hold a ritual of blood sacrifice. Pai pretends that the caravan wishes to witness the ritual for the blessing of the sultan. They are allowed to go through; however, only twenty men are allowed to witness the ritual. The blood ritual is conducted by the witch of Bampu who, facing a half nude maiden who is tied to a tree, is to gouge the young maiden’s bleeding heart to feed the sick sultan. This is supposed to be the cure. Royal Envoy Cheng Ho is greatly enraged. Forgetting his own danger, he leaps forward and stops the performance. He also hears the maiden speak to him in Chinese asking for help.

On the other hand, Cheng Ho uses his medicine from China to heal the sultan.

It happens that the maiden is a princess of Tunhindu who has been captured on the high seas by pirates and later by the Bampu tribe. In her childhood, she had a Chinese nurse, therefore she could speak some Chinese.

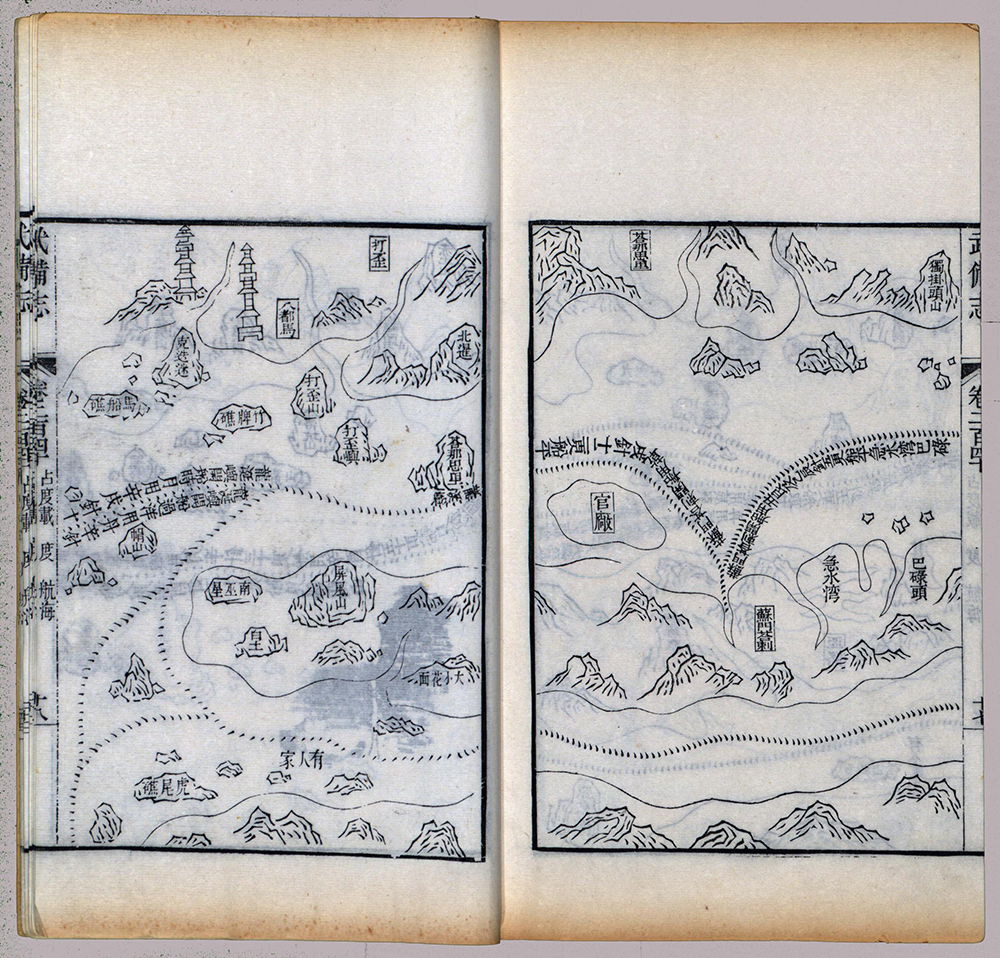

Illustration 8 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 12

Cheng Ho has saved the life of the Bampu Sultan; but, to his disappointment he is not able to get any news of the escaped ex-Emperor. He loses track of the exiles. He therefore accompanies the Princess of Tunhindu and crosses the low lands to reach the harbour and joins his fleet. The Princess of Tunhindu also boards the flagship.

The name of the Tunhindu Princess is Malayar. She is greatly fascinated by Royal Envoy Cheng Ho while they are sailing together on the flagship. Malayar tells Cheng Ho that there are many pirates on the high seas and most of them are led by Chinese.

Scene 13

The great Pacification Fleet now pays a visit to Tunhindu.

By now, Princess Malayar of Tunhindu falls in love with her saviour Cheng Ho and wishes to marry him. She is not aware that there are eunuchs in this world; at the same time, the eunuch Cheng Ho, living on board with the princess, also develops a great liking for the princess. In Tunhindu, he sees Princess Malayar everyday. He develops a great liking for her mentally; but he cannot go any further because of his physical deformity. Yet he cannot reveal the sad truth to Princess Malayar.

He lives in pain because of his love for the princess; finally he makes the excuse that he must resume his travels; however, the princess vows for enternal love. Cheng Ho could not contain himself any longer and finally reveals his own weakness to her; however, the sentimental Princess Malayar still wants to marry him and asks him to return.

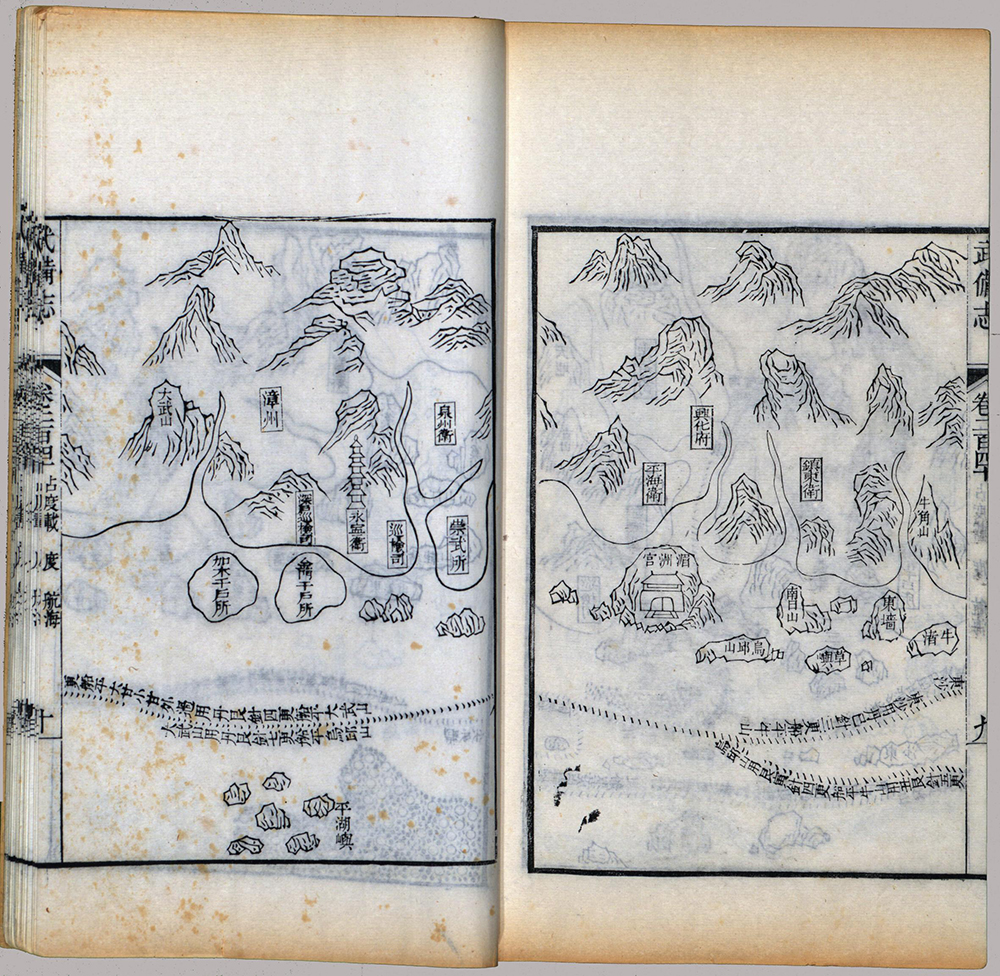

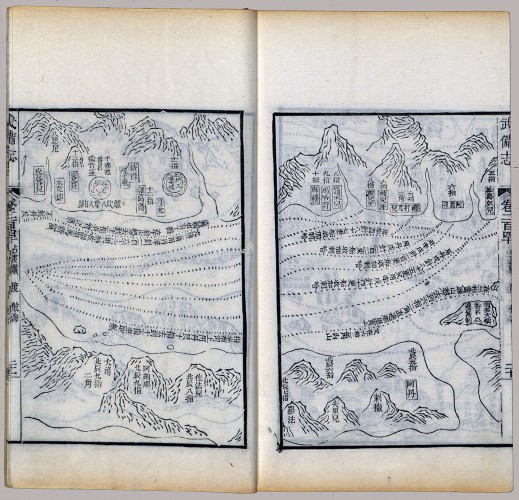

Illustration 9 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 14

The Royal Ming Armada now turns into the region known as Indonesia. They visit Japor, now known as Java. He was told that a Chinese pirate leader, Chen Tsu Yi, had invaded the country of Sambhutsi now known as Chiukang. Pirate Chi’s ships also invaded Japor’s ports and pillaged the ports’ commercial vessels.

The pirate also often raid Chiaoluansan where more than half of the people are Chinese.

Pirate Chen is originally an outlaw of the Pearl River of China. Being chased by government troops he takes to the sea and expands his fleet in four years; he occupies Samphutsi and captures several European vessels; hence he has guns and cannons and commands more than one hundred pirate ships, big and small.

Cheng Ho presents big guns to the Sultan of Jopor to defend his port.

Scene 15

The Royal Envoy Cheng Ho who has never had experience in naval battles, is finally forced to fight pirate Chen on the high seas. Pirate Chen Tsu Yi puts up a ruse and lures Cheng Ho’s fleet into Fresh Water Bay. The pirates had hoped to use land based guns to fire and destroy Cheng Ho’s armada; but in the ensuing battle the Royal Ming Armada wins the battle and captures pirate Chen, as prisoner.

Illustration 10 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 16

In central China Proper, Cheng Ho has completed three voyages to the western oceans. Emperor Yung Lo now pays less attention to the capture of the exiled Chien Wen. Because of Cheng Ho’s three sailings to the oceanic countries, it becomes clear to the Emperor that to develop maritime activities, and to establish contacts with more countries are more important than to capture an exiled king. So he orders Cheng Ho to continue to sail to the western oceans- to sail farther and to new countries. Now Cheng Ho is only taking a vacation in Nanking.

The Ambassador from Tunhindu has now arrived at the Ming capital. The five men mission pays a courtesy call on Cheng Ho first; then, led by Cheng Ho, they are received in audience by the Emperor. The Ambassador reports that Tunhindu Sultan had passed away; and their new supremacy is a woman.

After court, one of the five mission members meets with Cheng Ho and conveys to him the anticipation of Sultana Princess Malayar and her love. He says that Malayar is waiting for Cheng Ho and has not married. He asks Cheng Ho to visit Tunhindu once more no matter what happens. Finally Cheng Ho agrees.

Illustration 11 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 17

Cheng Ho’s mind flashes back to his adventures on the oceans and his love episode with Princess Malayar. He tries to suppress his longings because he is an in-capacitated eunuch; but the appearance and information of the Ambassador rekindle his sentiments. He dreams of an island, and is with Malayar again.

So Cheng Ho begins to study medicine. He befriends religious cults and seeks the secret formula of the Taoist’s medicine called Nine Rejuvenation pills which is said to have miraculous powers of regaining and restoring manhood. He finally finds a famous Taoist disciple called Chuachinchee to concoct the pills for him.

Illustration 12 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 18

The Emperor now orders Cheng Ho to make a fourth voyage to the south seas.

This time, they sail much farther. They cross the Indian Ocean and reach the Arabian Sea, the first time that a Chinese fleet has ever entered the legendary water. Cheng Ho visits Persia, a country destroyed by the Mongolian invasion. The Mongolians destroyed the water reservoir of this ancient and cultural country.

Furumous is a country on the ancient Persian 1and. Cheng Ho makes a short stay there and helps their reconstruction and despatches agricultural experts to aid the natives. Cheng Ho also takes with him the daughter of the Sultan of Furumous by the name of Pinkey who is going to the country of Arabia to be married. Twelve persons accompany her.

The Red Sea, full of mystery and awe, frightens all the men on the Royal Ming Armada. Cheng Ho quietly inquires of Pinkey and learns the reason why the Red Sea is red. So he tells the mythological stories and heavenly fairies to his men to pacify them; and they peacefully and successfully enter the Red Sea, sail along the peninsula of Sinai, pass the Bay of Akaba, visit western Aden, and go directly to Arabia.

In Arabia, Cheng Ho and his mission are given a big welcome and the Sultan gives him six giraffes- which in Chinese history are called kirin.

Cheng Ho wines and dines in Arabia, and enjoys a series of animal dances as well as religious ceremonies.

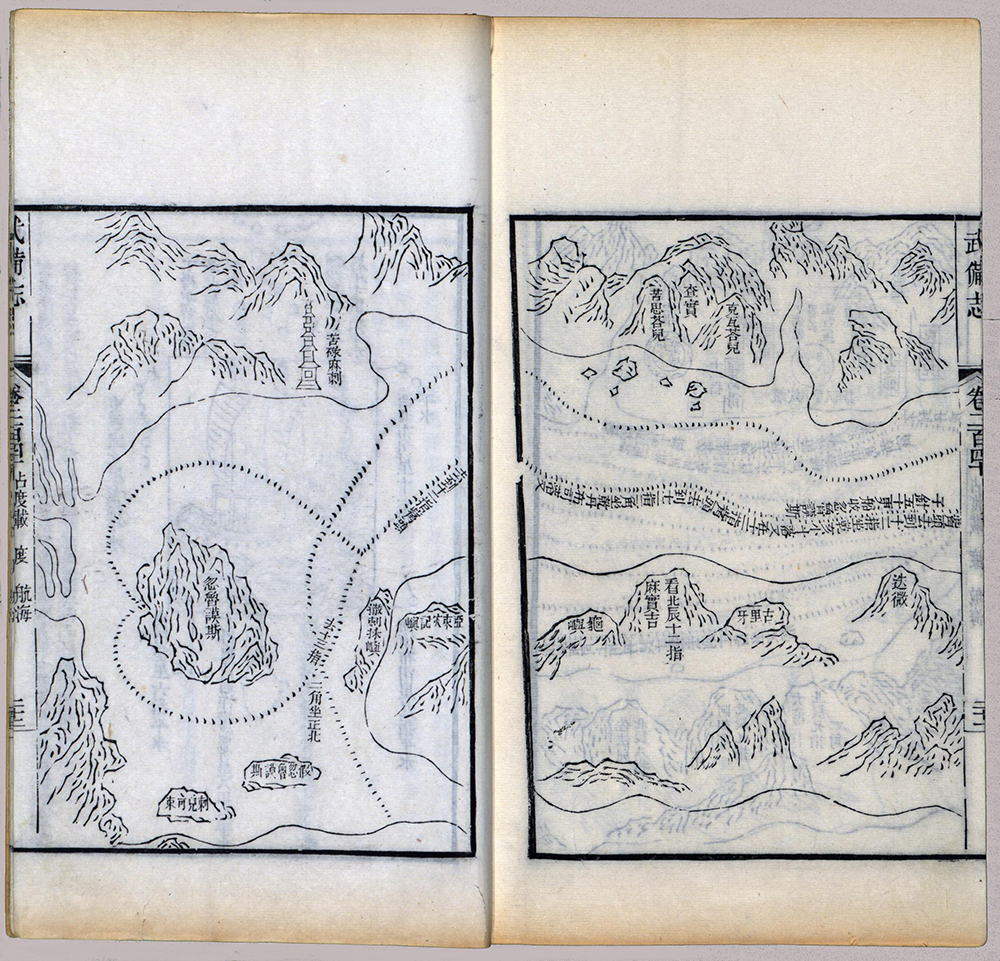

Illustration 13 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 19

On his fifth voyage overseas, Cheng Ho begins to take the Nine Rejuvenation pills. This medicine is potent and stimulates Cheng Ho greatly, and he is almost turned abnormal. He takes this as a good symptom. And once, after three months, Cheng Ho has a bad dream when he is on the South Sea. He sees the Princess Malayar dancing on the lawn in the evening, barefoot. In Tunhindu he had seen Malayar dancing; though it is only a dream, yet he is over-excited by Malayar’s dances. He opens his arms to receive her but is awakened by a big noise. He has fallen from his bed, as his ship has run aground. And Cheng Ho is in high fever. His deputy Wang Ching Hung is trying to save the ship and orders the doctor to cure Cheng Ho from his medical poison. The doctor lets blood from Cheng Ho and gives him herbs.

Illustration 14 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 20

Fog lifts. The flagship is freed and is being repaired. They all anchor in a small harbour for minor repairs. Cheng Ho’s fever also subsides and is fully recovered in seven days. His hope, his dream have also vanished. Cheng Ho is repentant for his own negligence and selfishness. He vows to serve his country better and to devote to cruising to the countries in the western oceans. Twice nearing the shores of Tunhindu, twice he does not enter.

He is suffering but he swallows his own pain.

Scene 21

In Tunhindu, a new alien visitor has appeared. He is none other than the exiled Abbot Ying Wen who was the former Emperor Chien Wen. Although he has friendly support from some island countries but the goodwill visit of Cheng Ho has befriended these countries and destroyed Emperor Chien Wen’s designs. He is now a mere guest. The agricultural assistance given by Cheng Ho to Tunhindu and other administrative skills brought back by Tunhindu’s ambassadors from China make Tunhindu an orderly and wealthy country. At the same time, the Sultana of Tunhindu and Abbot Ying Wen become good friends. But only because he is also a Chinese.

Malayar confides her love for Cheng Ho to the Abbot; she is also sorry that Cheng Ho has not visited again. She knows also Cheng Ho had more than once visited her neighboring countries but did not come near her. Then Abbot Ying Wen explains the system of eunuchs of China to Malayar. Although Ying Wen knows that Cheng Ho is after his head, he does not say anything against Cheng Ho but explains an eunuch’s physical constitution. For this, Sultana Malayar of Tunhindu only weeps.

Illustration 15 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 22

Time and togetherness develop a new sentiment between Malayar and Abbot Ying Wen. She secretly takes Abbot Ying Wen to be the substitute of her long pined Cheng Ho.

The followers of the ex-Emperor advise Ying Wen to marry Malayar so that they could use the power and wealth of Tunhindu to restore the throne.

However, Abbot Ying Wen has lived with an orphan girl Pearline from the South Seas as common law man and wife. After long years of exile, he has no more ambition for restoration and he has no wish to give up Pearline. Of course, Pearline through all these years has known all about Ying Wen and his royalty. She also advises Ying Wen to marry Malayar. She has only hoped that all Ying Wen’s followers could have a peaceful place to live.

Scene 23

Taoist Chi and others help Pearline to be near to the Sultana. After she has become closer to the Sultana and consulting the other followers of Abbot Ying Wen, she tells the truth about Abbot Ying Wen to the Sultana. She also proposes for her master to the Sultana.

Illustration 16 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 24

Under the palm trees, by the seaside, and at the sunset, in a small canoe, love develops by promotion of others on the sidelines between the Sultana and the exiled Emperor.

In the country of Tunhindu, relations between man and woman are natural and devoid of formalities, much unlike those of China Proper. When they are seen together always, the people of Tunhindu take for granted that Abbot Ying Wen is the husband of the Sultana.

The people of Tunhindu know well the custom of Siam and Singa. After a period of serving as a monk, Abbot Ying Wen shall return to civilian life and marry the Sultana.

And now, the Sultana of Tunhindu is with child.

The Sultana tells the news to her people and announces her date of wedding to the Abbot Ying Wen.

Illustration 17 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 25

It might just be a happy coincidence that at this time, the Royal Ming Armada has arrived at Tunhindu. For days, all the people of Tunhindu excitedly prepare a royal welcome. However, for Abbot Ying Wen and his men, this is not good news; this is catastrophe. Abbot Ying Wen’s followers suggest that the Sultana be coerced to lure the Ming vessels to port and kill all the soldiers and take over the ships, and assemble the able-bodied men of all the island countries to fight a war of restoration for him.

But Abbot Ying Wen sternly and decidedly rejects this suggestion. He deems that it is well for the Ming Court to spread its power and fame to far off countries. Although he himself is exiled, he is still a subject of the Ming Court. He shares in the fame and glory of Ming. He also knows that all the people of Tunhindu are pleased with the Ming Court and would not fight the Ming soldiers and sailors even if ordered by the Sultana.

Illustration 18 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 26

The Sultana knows well that Abbot Ying Wen’s men and Royal Pacification Mission’s men could not be brought together. Therefore, before the arrival of the Ming Armada, she talks to Ying Wen and ask the Abbot’s men to go hiding in a western harbour of the country. She is sure she could handle the situation and protect her husband well.

Scene 27

Abbot Ying Wen and his men then move on to the western coast and reach the port where the Sultana has a country house and ships in the harbour.

The followers, however, think that the Sultana is going to be threatened by Cheng Ho and his men and would sacrifice the ex-Emperor. They have hoped that the Sultana would crush Cheng Ho’s armada. When this hope is dashed, they are in panic and think it would not be safe to remain. They then kidnap Abbot Ying Wen, put him on board a ship, and all escape from Tunhindu.

Illustration 19 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 28

At length, after more than ten years, comes the reunion of Cheng Ho and Malayar.

They heartily tell about each other’s past life in the absent years. Cheng Ho tells Malayar everything that has happened to him; and he also explains why he has passed by but not visited Tunhindu in his past few voyages. He has no courage to face Malayar. He bares everything and pleads for Malayar to marry someone else.

The Sultana takes Cheng Ho to walk on the seaside. She tells her story entirely to Cheng Ho.

Cheng Ho is more than surprised at her new love and her pregnancy. But the Sultana maintains that an exiled emperor, away from his own country for so long a time, could do no harm to his country. And she wants Cheng Ho not to go after the deposed emperor.

Cheng Ho, like a cabinet minister of a great country, deliberates only very briefly and forgives Abbot Ying Wen. He vows that he would not reveal that the deposed emperor is now in Tunhindu. He also vows that while he is alive he would not cause the Ming fleet to visit Tunhindu again so that they would not discover the whereabouts of the ex-Emperor Chien Wen.

Illustration 20 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 29

After seven days in Tunhindu, Cheng Ho finally takes leave of Malayar, never to meet again.

They have now become the genuinest of friends. At the parting, the Sultana promises to send tributes every three to five years to China and to exchange information.

Scene 30

Now Cheng Ho is sailing away. The great Ming Armada, under full sail, moves into the horizon. The Sultana stands and watches the sails and masts disappear in the distance. Lonely and forlorn, she returns to her palace.

Now she goes to the west coast herself to bring back her husband.

At the west coast, the house is empty. People are gone; the exiled Emperor and his followers have left and would never return.

Now the forsaken Sultana of Tunhindu is a lonesome and forlorn figure on the sea beach.

Her love whether it is real or whether it is fancy has all become thin air. But she is with child.

Illustration 21 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 31

After seven long long voyages to the south seas and western oceans, covering twenty eight long years, Cheng Ho’s reputation is at its greatest height- the first eunuch who has achieved so much in his royal service. He is now aging and he is now old. He asks for retirement. He has reached the epic of rank among eunuchs. He has excelled everyone of his denomination.

Scene 32

In retirement, Cheng Ho plants many tropical trees in his own garden. In the great hall of his house, there is the model of the great Royal Armada.

He dreams of the sea. He dreams of the Armada. He only regrets that he is aging and becoming useless, and could not cover all the oceans.

Illustration 22 of Chen (Cheng) Ho’s voyages to the Western Seas in Wu-pei-chih (武備誌) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress

Scene 33

A new Sultan has come to the succession and he sends his Ambassador to Ming Court. After the Royal audience, the Tunhindu Ambassador pays a call to an old and invalid Cheng Ho.

Cheng Ho, partly reclining in his sick bed, is fondling a model of a sea going vessel.

The Ambassador thus reports to Cheng Ho. The Sultana Malayar of Tunhindu has passed away and a young Sultan has succeeded her. The late Sultana has left some memento for the great Chamberlain Cheng Ho.

He opens the parcel. He finds just one lock of hair- all snow white- Malayar’s hair. She has her lock of hair cut just before she died to be sent to him. Cheng Ho holds the white lock of hair, close to his face, and glances at the model of the sailing ship. Tears drop over his face and fingers and the white hair. A faint smile breaks through to reveal his peace of mind and peace of heart.

Front cover of First Draft of the Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen (Cheng) Ho by Mr. Ma Pin (Nan Kung Po 南宮搏)

Title page of First Draft of the Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen (Cheng) Ho by Mr. Ma Pin (Nan Kung Po 南宮搏)

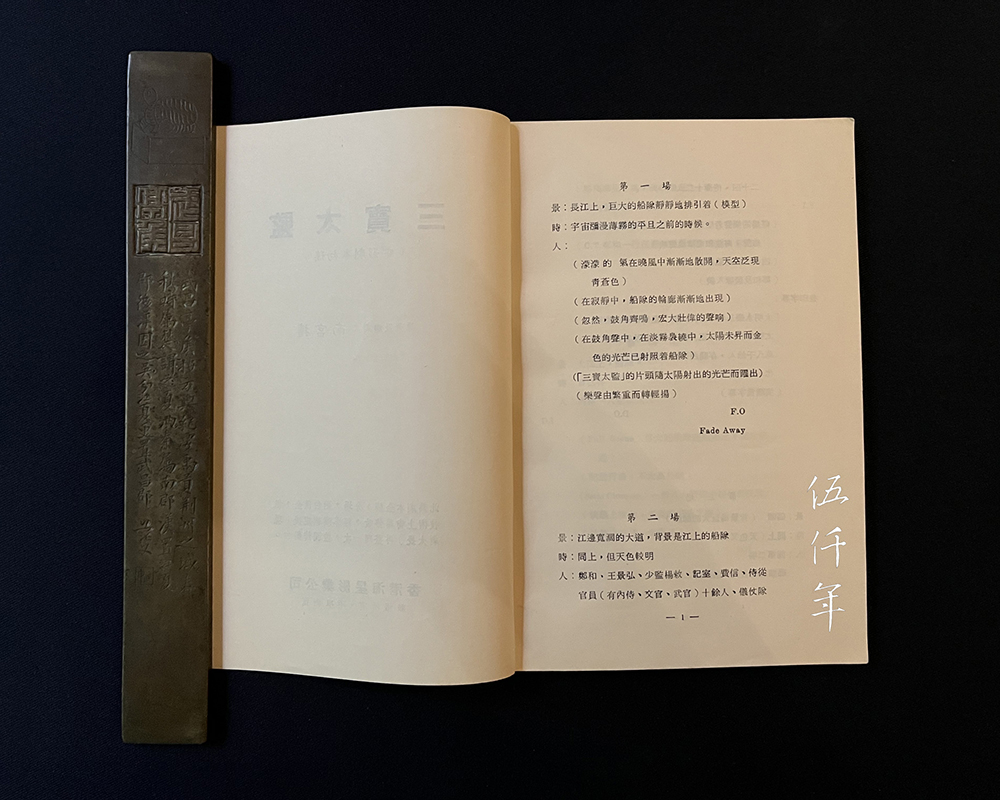

Inside page of First Draft of the Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen (Cheng) Ho by Mr. Ma Pin (Nan Kung Po 南宮搏)

Related Contents:

Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen Ho (鄭和) and Mr. C. Y. Tung (董浩雲)

Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen Ho (鄭和), by the Late Mr. Yao K'o (姚克)