In the 43rd year of the Republic (1954), the shipping magnate Mr. C. Y. Tung (董浩雲 1912-1982) planned to produce a movie about the voyages of Cheng Ho (鄭和 1371-1433?, or Chen Ho) to the Western Seas. He engaged the distinguished dramatist Mr. Yao K’o (姚克 1905-1991) to write an outline of the screenplay. It was first published in the 189th issue of the Maritime Digest, a bi-monthly magazine edited by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng, on 30 June in the 49th year of the Republic (1960), under the title Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen Ho. We hereby reproduce the full article for posterity.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

Portrait of Mr. Yao K’o

Chen Ho (鄭和 also spelled Cheng Ho) commanded seven voyages to the Western Seas. They lasted twenty eight years and passed through more than forty countries. He visited Aden (亞丁) at the mouth of the Red Sea (紅海), Malinde (also known as Malindi), Magedoxu (also known as Mogadishu), Brawa (also known as Barawa), and Rasa of East Africa, Djofar in the Arabian Sea (阿拉伯海), and Mecca (默伽) in the Red Sea, becoming the first Chinese to reach the east coast of Africa south of the equator. At that time, he was seventy-four years ahead of the discovery of the New World by Christopher Columbus and seventy-nine years ahead of the discovery of the sea routes to Europe, Africa, and Asia by the Portuguese. He was indeed the most outstanding and advanced navigator in the world. I have been commissioned by Hong Kong Maritime Film Services Ltd. to compile and write the film story and script for Eunuch San-pao (a colloquial title of Chen Ho). This film story is now to be published in Maritime Digest, a bi-monthly magazine, with the hope that the world’s greatest Chinese navigator and his remarkable achievements can be better recognized by people around the world through the artistic power of modern movie.

In making the movie, if the film script follows the sequences of historical incidents, it may drag on for too long. Furthermore, earlier and later incidents will become autonomous parts with no connection. The script will not only be tedious and fractured, it will also miss out on overall dramatic effect. Hence a narrative that assimilates different historical incidents is adopted, whereby the most significant events that occurred during the seven voyages are combined together. Using the conflicts between Chen Ho and his generals as warp, the facts of history as weft, coherence can be sought amongst snippets, plausibility can be asserted with fiction. It is hoped that the whole movie will be imbued with dramatic tension without violating historical truth.

Yao K’o

Front cover of Maritime Digest, Issue Number 189 dated 49th year of the Republic

Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen Ho by Mr. Yao K’o published in Issue 189 of Maritime Digest

ONE

In the third year of the Yung-le (永樂) reign (1405) in the Ming Dynasty, a view of Lung-wan (龍灣), also known as Hsia-kuan (下關) in Nanking (南京): A forest of masts that belonged to the Pao Ships (also known as Treasure Ships) stood in front of the shipyard, banners and flags blocked the sky, and behind them the overlapping ridges of Shih-tzu Mountain (獅子山), Mu-fu Mountain (幕府山) and Tzu-chin Mountain (紫金山) constituted a magnificent sight. A young man of about twenty years old, Fei Hsin (費信), reined in his horse on Shih-ch’eng Bridge (石城橋) , stopped and gazed afar, with an expression of wonder and amazement. He then galloped off the bridge towards Lung-chiang Pass (龍江關).

The security was tight at the checkpoint. Labourers who loaded cargo onto the ships had to show their waist badges and to turn in their number tags before they could enter. Fei Hsin dismounted from his horse and presented a document with the words: “Requisition by T’ang Ching (唐敬), the Right Guard Commander of the Navy, for Fei Hsin, a trainee interpreter from the Bureau of Translators (四夷館) in T’ai-ts’ang (太倉), to come and serve as interpreter for the Navy." The company commander quickly took the document and handed it inside.

T’ang Ching was on board the vessel Ch’ang-ning (長寧), watching the generals conduct naval exercise in the middle of the river when a messenger presented him with the document. He quickly ordered Fei Hsin to board the ship. As soon as the naval exercise ended, the messenger brought Fei Hsin into the cabin. Fei Hsin was in fact T’ang Ching’s nephew, and after greeting each other with a few words of family conversation, T’ang Ching introduced him to the generals. The first was Wang Heng (王衡), the second was a big man with dark face and curly beard named Hu Fu (胡復), the third was Lin Ch’üan (林全), and the fourth was P’eng I-sheng (彭以勝). When Hu Fu heard from T’ang Ch’ing that Fei Hsin was going to be an interpreter on the capital ship of Chen Ho’s fleet, he said aloud: "Brother, keep your nephew with the Guard so that he won’t be bullied under the tent of that castrated horse!"

T’ang Ch’ing knew that Hu Fu was rash and spoke recklessly, so he quickly stopped him. However, the other three generals were also dissatisfied. For one Chen Ho was a eunuch, the other he was a Muslim, so they all felt he did not deserve to be the Chief Envoy. T’ang Ching told them Chen Ho had fought many battles and was said to be brave and astute, they should not dismiss him.

Upon hearing these words, P’eng I-sheng was hotheaded and announced: “When we go to the Western Seas this time, as long as I can have a good fight, I don’t care if he’s a eunuch or a Muslim. Otherwise, I’ll wreak havoc!”

As the generals were giving a dinner to welcome Fei Hsin, Chen Ho and his deputy Wang Ching-hung (王景弘) were at an audience with Emperor Yung-le in the Hall of Practicing Moral Cultivation (謹身殿). Yung-le gave them the instructions left by Emperor T’ai-tsu (太祖), the founding Emperor of the Ming Dynasty, instructing them not to resort to fighting lightly, but to use peaceful and friendly means so that foreign nations could look up to them. After listening to the instructions, Chen Ho summoned the generals onto the deck of the capital ship Ch’ing-ho (清和) the following day, to proclaim aloud the text of the Imperial Instructions and Prohibitions of Emperor T’ai-tsu. At the same time, he also issued an order to all officers and soldiers that whenever they visited a country, they must be polite, patient, respect the laws and customs of that country. When they went ashore, they should not carry weapons, get drunk, visit prostitutes, harass women, nor insult the local people.

This address greatly disappointed the generals. They all wanted to go on expeditions to conquer foreign lands, to establish some feats in war, to earn promotions to high ranks, and to have their wives and children taken care of. Now they were not even allowed to carry weapons ashore, so what hope was left? When Chen Ho entered the cabin, the generals began to discuss among themselves. The more hot-blooded could not contain themselves, and pushed T’ang Ching and Lin Tzu-hsüan (林子宣), the Chin-wu (金吾) Left Guard Commander, to represent them and convey their opinions to the Chief Envoy and the Deputy Envoy.

Wang Ching-hung had already noticed the dissatisfied expressions of the generals. Once he entered the cabin, he suggested to Chen Ho that he should not rigidly follow the imperial edict, and he must be flexible. Chen Ho believed that since he had received the edict, he must act accordingly and should not change it on his own. Now T’ang Ching and Lin Tz’u-hsüan entered the cabin and asked to see him. T’ang Ching had been an envoy to Chen-la (真臘 now Cambodia) and was very familiar with the customs of foreigners. He said that foreigners all carried short knives and would draw them at the first sign of disagreement. If the troops were not allowed to carry weapons when they went ashore, how could they defend themselves in case of trouble? However, Chen Ho was very firm and refused to compromise. T’ang Ching could only leave disgruntled. Wang Ching-hung privately advised him not to be discouraged, when peaceful means failed in the future, Chen Ho would naturally use military force.

At this time, the central command ordered all generals to return to their respective vessels and be prepared to set sail. The generals hung their heads down in frustration and dared not voice their anger. Before leaving, T’ang Ching instructed Fei Hsin to be cautious. Fei Hsin respectfully assured him.

Many civil and military officers came to the pier of Lung-chiang Pass (龍江關) to see them off. Chen Ho and Wang Ching-hung went ashore to thank them in return. The chief-minister of The Court of State Ceremonial (鴻臚寺) awarded them three cups of imperial wine by order. Chen and Wang then re-boarded the ship, after they made ritual offerings to the large admiral’s flag, the central command played ceremonial music to raise the flags, and all the ships fired their cannons in unison, shaking heaven and earth. The officer of meteorology (陰陽官) reported that the auspicious time had arrived, and Chen Ho ordered the ships to set sail. The central command raised the flag signal from the watchtower. The sixty-two giant ships lined up neatly on the river and sailed downstream in majestic formation.

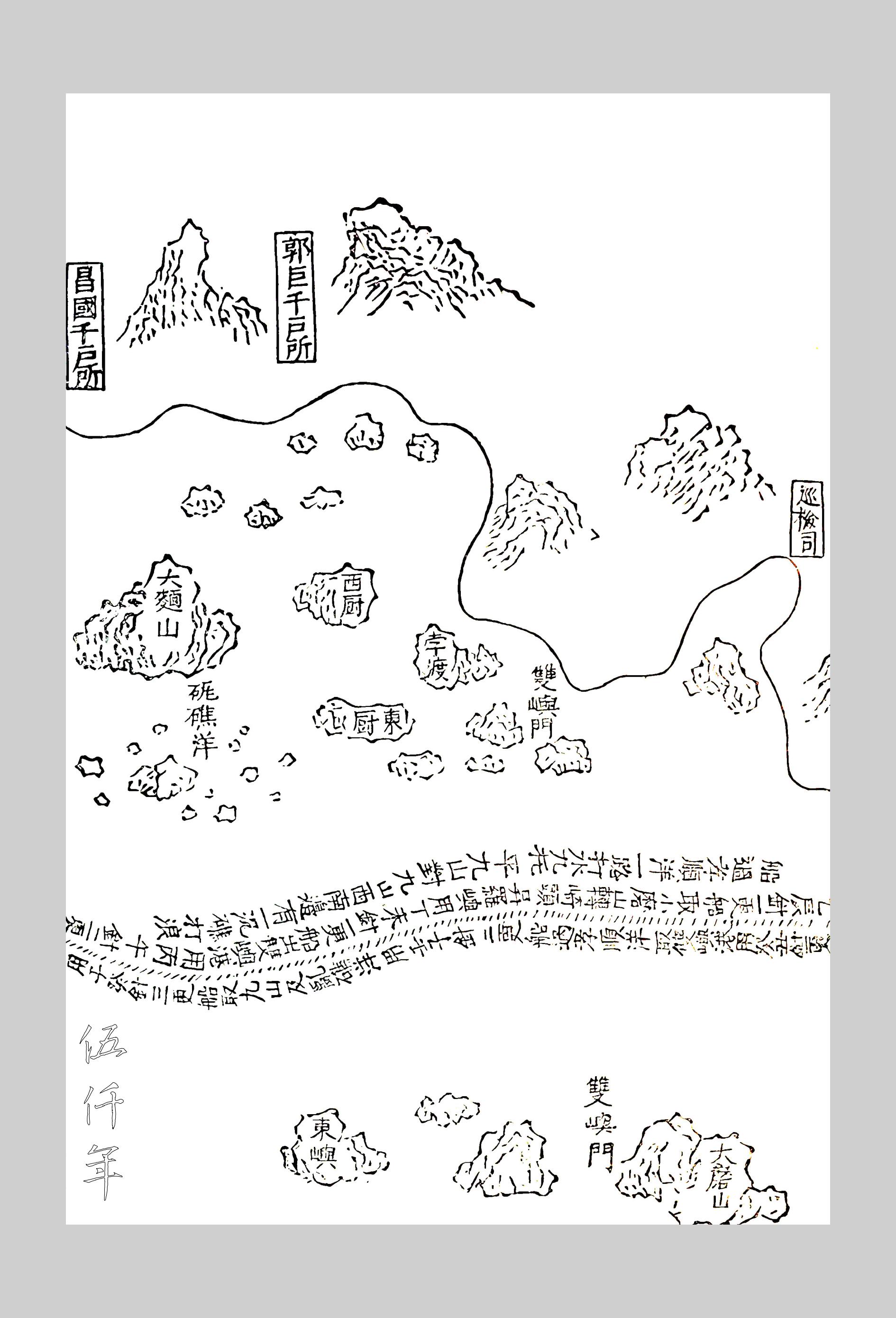

Fei Hsin did not feel lonely on the ship Ch’ing-ho. His fellow interpreters included Ma Huan (馬歡), Kung Chen (鞏珍), and Kuo Ch’ung-li (郭崇禮). There was also the chief imam Hassan (哈三) who was proficient in Arabic, and the Buddhist monk Lao-hui (釋勞慧) who was proficient in Sanskrit. Among the palace officers (内監) were Li Hsing (李興), Yang Min (楊敏), Li K’ai (李愷), Hung Pao (洪保), Chou Man (周滿), K’ung Ho-pu-hua (孔和不花), T’ang Kuan-pao (唐觀保), Chu Liang (朱良), Chang Ta (張達), Yang Chen (楊真), Wu Chung (吳忠) and others. The military officers included the commanders of the Imperial Bodyguard (錦衣衛) Li Shih (李實), Ho Tsung-i (何宗義), battalion commanders (正千戶) Lu T’ung (陸通), Ma Kuei (馬貴), Chang T’ung (張通), Liu Hai (劉海) and others. In addition to boatmen and sailors, there were scribes and accountants, doctors, meteorologists, craftsmen of all trades, and even an engraver of calligraphy. This was Fei Hsin’s first voyage, and he found everything fascinating. He watched as the helmsman navigated according to the nautical map, using a compass by day and observing the stars at night. The cartographers measured the depths of the sea with a lead weight at each location and added remarks and drawings on the maps, noting the shallow beaches and reefs. The commanders recorded the sailing logs in detail. In addition, there were the keepers of the carrier pigeons on whom the exchange of messages between ships depended. Fei Hsin observed throngs of naval activities. At the beginning of the fifteenth century, a fleet this massive together with such advanced navigation technology was unparalleled in the world. It is therefore worthwhile to describe Fei Hsin’s observations.

The fleet sailed across the boundless sea and sky, braving wind and waves. The arrow on the nautical chart pointed from Lung-wan (龍灣) to the Liu River (瀏河) where the fleet sailed into the sea. Then the fleet headed southward to Ch’ang-le Port (長樂港) in Fukien Province (福建) before turning southwest along the coastline, sailing straight for Hsin-chou Port (新洲港 present day Quy Nhon 歸仁 in South Vietnam) in the kingdom of Champa (占城國 now South Vietnam).

TWO

Ch’ang-ning (長寧) was the flagship of the vanguard, sailing a long way ahead of the fleet. The naval signal flag indicated that they were approaching Champa. T’ang Ching led the four generals Wang, Hu, Lin, and P’eng on two double sided eight oar vessels to enter the harbour, and notified the king of Champa, Ba-dich-lai (占巴的賴). When the king heard of the arrival of the Celestial Envoy, he quickly mounted an elephant and personally went to the harbour to welcome them. He was accompanied by more than 500 guards who struck the welcome drums and blew into coconut flutes, while his subordinates rode on horses. Chen Ho went ashore, read aloud the imperial edict, and presented the imperial gifts. The king and his people cheered and welcomed Chen Ho and his men to rest in the capital city.

That day, the king held a banquet in the palace to entertain the Celestial Envoy and his generals. Wine was placed in jars, and everyone drank from the jars using thin bamboo pipes that were three to four feet long. There was music and dancing at the banquet, and the scene was very lively. At the banquet, the king expressed his gratitude for the Chinese emperor's decree to Annam (安南) not to invade his borders, but he said that Annam outwardly pretended to obey but acted to the contrary. Chen Ho promised to send an envoy to Annam to convey the message of stopping the hostilities.

In the afternoon, twenty more Chinese ships arrived at Hsin-chou Port. T’ang Ching and the other generals went to the port to greet them. It turned out it was Wen Liang-fu (聞良輔) passing by on his homeward voyage after his mission to Calicut (古里). As soon as Wen Liang-fu came ashore, he went to pay respects to Chen Ho. Ch’ien Pin (錢斌), a battalion commander under Wen Liang-fu, was originally a close friend of T’ang Ching, Wang Heng, and Hu Fu. When he met T’ang Ching, he told them that when he and his brother were passing by Java (爪哇) with their troops, they landed at a market, and by coincidence got caught in a battle between the kings of East and West Java. One hundred and seventy Chinese soldiers were accidentally killed by the subordinates of the king of West Java, and his brother was shot by an arrow and died. When the generals heard this, they were very angry and wanted nothing but to flatten Java. Ch’ien Pin begged T’ang Ching to let him stay on board, when the fleet arrived in Java he could serve as a guide to avenge his brother’s death. T’ang Ching readily agreed.

Next morning, Chen Ho dispatched Li Hsing and Yang Min to be his envoys, together with the troops and the translator Fei Hsin, they first went to Annam (安南) to persuade the king there to withdraw his troops. Then they went to Siam (暹羅 Thailand) to inform the king there not to invade Melaka (滿刺加 Malacca, Malaya). Kung Chen was sent after Hung Pao and Chou Man, while Kuo Ch’ung-li followed T’ang Kuan-pao and Chu Liang, traveling by separate vessels to Po-ni (渤泥國 Borneo), Luzon 呂宋國 (Philippines) and Sulu (蘇祿國 Sulu Archipelago). Chen Ho instructed Fei Hsin, Kung Chen, and Kuo Ch’ung-li to record their voyages in detail for assessment. He himself and Wang Ching-hung then led a large formation towards Java (爪哇). Wang Ching-hung told T’ang Ching privately that this might be the opportunity to gain outstanding military victories. T’ang Ching passed on this information to the other generals, who were all overjoyed and eagerly awaited for battle.

This time the fleet separated into four directions, which could be clearly seen on the map. Four arrows extended from Hsin-chou Port, one to Annam and Siam, one to Luzon and Sulu, one to Po-ni, and one to Java.

As said, Fei Hsin accompanied the two envoys Li Hsing and Yang Min to the capital of Annam. King Hu K’uei (Hồ Quý Ly 胡奎) welcomed them with courtesy but denied that there had been any aggression towards Champa. The envoys warned him not to use force again. Despite his reluctance, Hu K’uei still hosted a banquet and provided dancers and singers for entertainment. Fei Hsin chronicled the proceedings in detail for Chen Ho to read.

Kung Chen followed Hung Pao and Chou Man to Luzon. The king had sent envoys to China to pay tribute in the fifth year of the Hung-wu (洪武) reign (1372). He was therefore most hospitable to the envoys. In addition to banquets, he invited the envoys to watch cockfighting and traditional dances, they also exchanged goods. Kung Chen recorded everything in detail.

Kuo Ch’ung-li accompanied the two envoys T’ang Kuan-pao and Chu Liang to Po-ni. King Maharajah Karna (麻那惹加那) treated them with great hospitality. The banquet was accompanied by drums, flutes, beating of bowls, singing and dancing. Kuo Ch’ung-li recorded everything in detail.

Chen Ho’s fleet passed by Gresik (革爾昔), reached Tuban (杜板) in Java, and arrived at Surabaya (蘇魯馬益). The harbour water was shallow, the troops switched to smaller boats to disembark at Changkir (章姑). They walked through the forest for a day and a half before arriving at the capital city Madjapahit (滿者伯夷).

The generals thought that this time Chen Ho would lead a great avenging army to punish the king of West Java and sought justice for the one hundred and seventy troops who had been killed. To their surprise, Chen Ho only ordered them to set up camp outside the city and not to leave the campsite without permission, except for gathering firewood and fetching water. Chen Ho and Wang Ching-hung only brought five hundred officers and soldiers into the city with various gifts from the Emperor, leaving their weapons in the camp. The generals watched on, they were greatly disappointed, wondering what Chen Ho was up to. Ch’ien Pin and Hu Fu couldn't bear it anymore, shouting that they would charge into the city and fight. T’ang Ching tried his best to restrain them, telling them to wait for Chen Ho’s orders, they calmed down only reluctantly.

That evening, the king of West Java invited the generals to a banquet. Hu Fu and others wanted to conceal weapons under their clothings, but T’ang Ching saw through their intentions and ordered them to leave the weapons in the camp, telling them not to violate their orders intentionally. During the banquet, Chen Ho mentioned the massacre of Chinese soldiers by Javanese soldiers. The king of West Java said: “One hundred and twelve years ago, your country sent Shih Pi (史弼), Yehemise (亦黑迷失) and Kao Hsing (高興) with an army of twenty thousand and a fleet of a thousand ships to invade our country. They killed an unknowable number of our soldiers and civilians, reaching tens of thousands. Now your country only lost over a hundred people. What’s the deal?” Wang Ching-hung, T’ang Ching, and the other generals were all outraged by the king’s unreasonable remarks. However Chen Ho still kept a pleasant countenance and explained to the king that the invasion of Java at that time was carried out by the Mongols who had invaded China, it was not the intention of the Chinese themselves. Now that China had expelled the Mongols beyond the Great Wall and made peace with other countries, the king could not blame the Chinese for what the Mongols did. Although Chen Ho’s words were extremely tactful, the king remained obstinate and refused to admit his fault. The banquet unpleasantly broke up.

As they were leaving the city, Ch’ien Pin caught sight of a squad of Javanese soldiers stationed outside the city gate. He recognized the leader as the one who had shot his brother and was even wearing his brother’s sword. He went forward to confront the foreign general and to engage him in a fierce fight, but the foreign general drew his sword and stabbed Ch’ien Pin’s arm. Hu Fu roared at him and grabbed a spear from a foreign soldier and thrusted it at the foreign general. Unexpectedly, another Javanese general jumped out from the side and used an Eight Demon Treasure Sabre (八魔寶刀) to break the spear. Wang Heng feared for Hu Fu’s safety and pulled him back. The foreign general chased after them but was blocked by Lin Ch’üan. Lin Ch’üan was agile and highly skilled in the technique of disarming an opponent with bare hands. The foreign general underestimated Lin Ch’üan as he had no weapon. He attacked Lin Ch’üan all over with the Eight Demon Treasure Sabre, but Lin Ch’üan jumped and dodged so the attacks missed every time. After several rounds, Lin Ch’üan saw an opening and used the “eagle assaulting fish” (蒼鷹攖魚) movement to snatch the sabre. He followed through with a double turn and threw the foreign general out to about ten feet away. The Chinese and Javanese soldiers watching on both sides were astounded by his skill.

On hearing the commotion from behind, Chen Ho hurried over to investigate. He saw the foreign general fell to the ground, while Lin Ch’üan proudly held the Eight Demon Treasure Sabre. Chen Ho quickly helped the foreign general stood up and instructed Lin Ch’ üan to return the sabre. Lin Ch’ üan dared not disobey and had to return the Eight Demon Treasure Sabre to the foreign general. Seeing Chen Ho’s handling of the situation, the other generals were all indignant. Hu Fu shouted, “This is so humiliating! I don’t want to live in disgrace anymore!” and proceeded to bang his head towards the city wall. Fortunately, Wang Heng and the others managed to stop him before he hurt himself. Tang Ch’ing couldn’t help but report the incident to Chen Ho, explaining that the foreign general should not have deliberately worn the treasured sword of Ch’ien Pin’s deceased brother. When Ch’ien Pin saw it, he naturally wanted to fight him. Chen Ho did not express an opinion on T’ang Ching’s protest but told him to pass the order to return to the ship quickly and not to linger. Anyone who disobeyed would be court-martialed!

T’ang Ching suppressed his anger and instructed the generals to return to the ship. Ch’ien Pin was injured and couldn’t help but wailed as he was not allowed to seek revenge even though he saw the murderer right in front of him. The generals all protested to T’ang Ching, some said that it would be better for everyone to die in Java rather than to see the country suffer such humiliation and disgrace in the Western Seas. Lin Tzu-hsüan, the Chin-wu Left Guard Commander, coaxed everyone not to disobey order, explaining that the Chief Envoy must have a reason with this approach. He suggested that they should wait till the following day to see how he dealt with the king of West Java, then they could make better sense of it. After hearing this, everyone returned to the ship, still indignant.

That night, Chen Ho and Wang Ching-hung summoned the vanguard (T’ang Ching), the rearguard (Lin Tzu-hsüan 林子宣), the left flank (Ha-chih 哈只), and the right flank (Li Shih 李實) to a meeting in the main cabin of the flagship Ch’ing-ho. T’ang Ching and Ha-chih both opined that the king of West Java was arrogant and unreasonable, and advocated the use of force to punish him. Wang Ching-hung also felt that it was necessary to maintain China’s prestige in this way. Chen Ho explained to them the difficulties of being a great nation. If one wished for all foreigners to proffer sincere and wholehearted respect, a great nation should not flaunt her military might, sometimes she should even bow low to claim modesty. To reach greatness, one had “to become the lowest valley in the world” (為天下谷). With the exception of Li Shih, everyone disagreed. Wang Ching-hung also argued with Chen Ho, criticizing him for being too weak and disregarding the country’s stature, and causing the soldiers to lose heart. Chen Ho reminded him not to forget the Emperor’s words. If the king of West Java remained obstinate on their return from the Western Seas, it would not be too late to report to the Emperor and launch a military campaign to punish him. After hearing this, Wang Ching-hung had no choice but to be quiet. To avoid further deterioration of the situation, Chen Ho asked Hassan, the chief imam, to deliver a letter to the king of West Java, hoping that he would not stubbornly cling to prejudice and instead prioritize diplomatic relations. After Hassan’s departure, Chen Ho ordered the troops to break camp in the early morning of the following day, returning to Tuban. Although the generals were not convinced in their hearts, they could only nod in agreement and leave.

After the meeting, the generals gathered on the ship Ch’ang-ning to discuss with T’ang Ching in private. They were furious about Chen Ho’s weakness. Hu Fu was the first to shout: “I’m mutinying!” T’ang Ching quickly called out to stop him. Ch’ien Pin knelt in front of T’ang Ching and asked him to plead with Chen Ho on his behalf, to allow him to go ashore alone for revenge. Lin Ch’üan, P’eng I-sheng, and others announced that they were willing to go with Ch’ien Pin, even to die. Lin Tzu-hsüan tried to persuade them not to go deep into danger and risked their lives in vain. After discussing for hours, they agreed to appeal to Chen Ho with their request in the following morning before they set sail.

Next morning, the generals gathered on the deck of the flagship Ch’ing-ho, nominated T’ang Ching and Lin Tzu-hsüan to represent them and appealed to Chen Ho in the cabin. After hearing out T’ang and Lin, Chen Ho’s face turned grave and he said: “Ch’ien Pin wants personal revenge, but we are sent to the West by imperial decree for the sake of diplomatic relations for our country. We cannot sacrifice our country’s diplomatic relations for the sake of one man’s personal revenge. You must persuade the other generals to return to their ships and prepare to depart. As for dealing with the king of West Java, we can only wait for the Emperor’s decision and cannot start a conflict without authorization.” T’ang and Lin saw that Chen Ho was unshakeable and knew that more talks would be futile. They left the cabin and tried to persuade the other generals to be patient. Wang Ching-hung also came out of the cabin and said to the generals: “You should all return to your ships first. The Chief Envoy is sent by imperial decree, even I cannot defy him. If Chen Ho continues to show weakness and disregard our country’s dignity, I will definitely report the situation to the Emperor when we return home and make an indictment.”

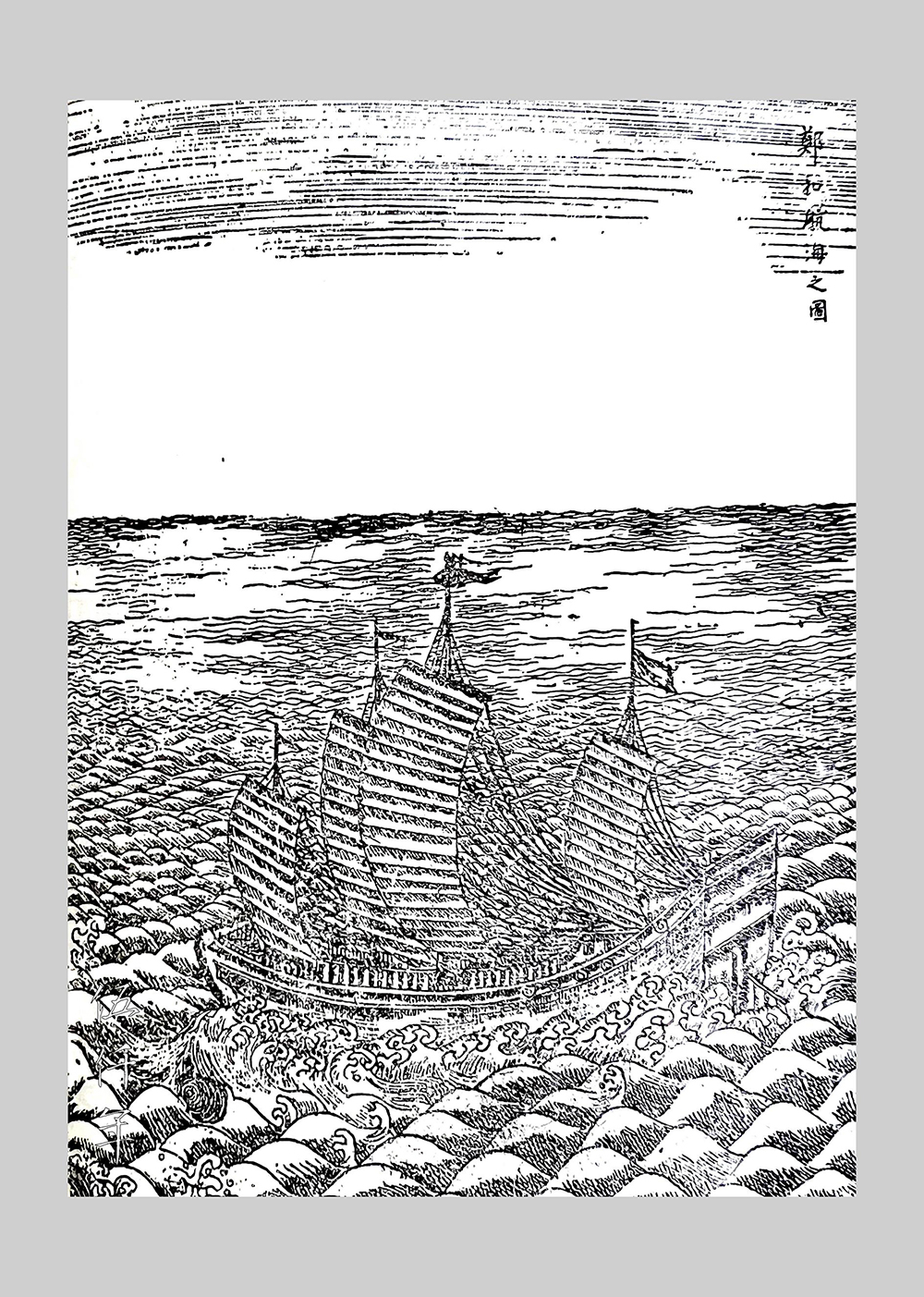

The fleet commanded by Cheng Ho consisted of over 27,000 technicians, officers and servicemen. It comprised of over sixty giant ships. If the small and medium-sized ships in the fleet are included, the number of ships will exceed two hundred. The largest ship is forty four chang (丈) and four ch’ih (尺) in length, and eighteen chang (丈) in width. Each ship was given a name, such as Ch’ing-ho, Hui-k’ang, Ch’ang-ning, An-chi, etc. The largest ship was crewed by one thousand servicemen, the average ship was crewed by four to five hundred servicemen. They were called Pao Ships (寶船). One shipyard was located at Liu River (瀏河) in T’ai-ch’ang (太昌), another at Hsia-kuan (下關) in Nanking (南京). At the foot of Chung-shan (鍾山) in Nanking, there were plantations for lacquer trees, tung oil trees and palm trees. They were used for extracting lacquer and tung oil, as well as making ropes, which were all necessary in shipbuilding.

THREE

On the nautical map, the arrow extended northwest from Tuban, pointing directly to P’eng-chia-men (彭家門) in Old Port (舊港 Palembang in Sumatra).

The story of the chieftain of Old Port, Ch’eng Tsu-i (程祖義), was that he was originally a notorious Chinese pirate. During the Hung-wu period, he was hunted down by the government and had to flee overseas with his family and followers. He used Old Port as his hideout to raid passing merchant ships and to terrorize the Chinese immigrants in the area, becoming the local tyrant. He often sent scouts to gather information on passing merchant ships, so when Chen Ho set out from Tuban, Ch’eng Tsu-i already had news. He knew that Chen Ho’s fleet was powerful and difficult to match in strength, so he had to outwit them. Hence he pretended to be loyal and obedient, he personally led his son Shih-liang (士良) and dozens of small boats to greet Chen Ho’s fleet in the open sea.

When the vanguard Ch’ang-ning encountered the welcoming boats, it was quickly reported to T’ang Ching and he ordered a rope ladder lowered to Ch’eng Tsu-i’s boat to bring him aboard. Although T’ang Ching had been to Champa as envoy before, he had never been to Old Port and did not know that Ch’eng Tsu-i was a notorious pirate. Seeing Ch’eng Tsu-i’s respectful demeanor, he believed him to be a loyal overseas Chinese and valued him highly. Ch’eng Tsu-i knew about the massacre of troops by the king of West Java, so he pretended to be filled with indignation and offered to lead the overseas Chinese to assist the army in its crusade against the king. Hu Fu, Ch’ien Pin, and other generals were so impressed by his loyalty and righteousness, they regarded him as a comrade in arms and were particularly friendly.

Not long after, the fleet led by Chen Ho arrived. The large ships were anchored at P’eng-chia-men, there they switched to small boats to enter Old Port. Ch’eng Tsu-i came to meet Chen Ho and Wang Ching-hung. Chen Ho asked him: “Last year, Commander Sun Hsüan (孫鉉) brought the son of the chieftain of Old Port, Liang Tao-ming (梁道明), back to the capital to pay respect to the Emperor. Who is Liang Tao-ming?” Ch’eng Tsu-i grabbed the opportunity to slander Liang Tao-ming, saying that he was a fugitive who deceived the court and should be escorted back, he should be executed to eliminate a menace to the local population. Chen Ho saw that Ch’eng Tsu-i looked shifty and cunning, definitely not a decent man, so he pretended to go along, and soothed him with kind words. At that moment, Liang Tao-ming, Shih Chin-ch’ing (施進卿), his daughter Shih Erh-chieh (施二姐) and son-in-law Ch’iu Yen-ch’eng (邱彥誠) came to seek an audience. Chen Ho gave the appearance of ordering his men to arrest them. Ch’eng Ts’ui-i thought that Chen Ho had fallen into his trap and thanked him before leaving.

After inquiring from Liang and Shih, Chen Ho then realized that Ch’eng Ts’ui-i was a pirate. He decided not to pursue the matter further, considering Ch’eng had been living as a fugitive abroad. Next day, Ch’eng Ts’ui-i came to pay his respects again. Chen Ho sternly admonished him: “Do not plunder merchant ships anymore, or terrorize the local people. From now on, you should reform your ways and be a good person. Otherwise, I will have to exterminate you and rid the area of harm!” Ch’eng Ts’ui-i came in high spirits, but got reprimanded instead, although he repeatedly muttered in concord, his heart was filled with murderous intent. T’ang Ching and the other generals saw the way Chen Ho treated loyal overseas Chinese, they couldn’t help feel indignant.

Chen Ho was in a hurry to embark on his expedition to various countries in the Western Seas, so he only stayed at Old Port for two days before sailing straight to Chiu-chou Mountain (九洲山, also known as Pulo Sembilan along the coast of Sumatra). Chiu-chou Mountain bordered Melaka and produced incense woods such as agarwood and yellow sandalwood. The troops explored the mountain and discovered six trees with a diameter of 8 to 9 feet and a height of 86 to 97 feet, with black flowers and fine veins. Their fragrance was pure and intense, making this a rare harvest.

After harvesting the incense wood, the fleet went straight to Melaka. T’ang Ching’s vanguard entered the port and saw some large Chinese ships that were already berthed there. It turned out that the vessels which had gone separately to Po-ni, Luzon, Sulu, and Siam had arrived first. When Chen Ho’s fleet arrived at the port, the king of Melaka, Parameswara (拜里迷蘇刺) personally led his wife and court officers to the port to greet them. After Chen Ho read aloud the imperial edict, he awarded the king with two silver seals, coronet, belt, robe, brocade, and a yellow canopy. He also awarded a piece of imperial writing that was to be engraved on a stele, and an imperial poem for decoration. The stele was to be installed in the western mountain of the country. The king expressed his gratitude and also thanked Chen Ho for sending envoys to Siam to warn off the king of Siam so that there was no longer any fear of invasion at the borders. After seeing the king, the envoys from different ships came to greet each other. Fei Hsin, Kung Chen, and Kuo Ch’ung-li presented the logbooks of their voyages. Chen Ho was pleased that all three envoys had completed their missions successfully. That night, the king held a grand banquet to entertain Chen Ho and his generals, and provided singers and dancers to accompany the drinking. The host and guests all enjoyed a rapturous time.

Next morning, the king accompanied Chen Ho, Wang Ching-hung, and the other generals on a seaside tour. Chen Ho saw that the location of Melaka was at a crucial junction between the Eastern and Western Seas, and suggested building a warehouse locally to store money and grain. When ships from various countries arrived, they could collect their cargo, prepare for shipment, wait for favourable southern winds and depart by mid-May to return to China. This would make trade much more convenient for long-distance voyages. The king eagerly welcomed Chen Ho’s proposal. Chen Ho ordered his troops to go up the mountains to cut wood and start building the fence. The fence was sturdy like a city wall, with four gates, watchtowers, an inner fence. The warehouse was like a small city, with storage rooms for goods. The troops had a lot of manpower, they worked together efficiently and in an orderly manner, cutting wood, transporting logs, building the fence and laying the roof. When the king visited Chen Ho again next morning, the magnificent warehouse had appeared overnight. He was so astounded that he was speechless, and suspected it was made with the help of God. Being both Muslim, the king and Chen Ho had a particularly friendly relationship. Chen Ho noticed the king’s amazement and took the opportunity to invite him to visit China, and the king readily accepted. They agreed that when Chen Ho returned from the Western Seas, the king would travel on a Pao Ship to China to pay tribute.

FOUR

The Pao Ships set sail from Melaka and arrived at the country of Sumatra. Envoys were sent with imperial edicts to the countries of Aru (阿魯國), Battak (那孤兒國), and Lide (黎代國). Before Chen Ho’s visit, the king of Sumatra, Zainal Abidin (宰奴里阿必丁), had already sent envoys with tribute to China in the company of Yin Ch’ing (尹慶), so he showed great respect to the envoy from the Celestial Empire. After reading the imperial edicts and giving gifts, Chen Ho asked the king if there was any aggressive action from Battak. The king replied that there was now peace with Battak, but Sekandar (蘇幹刺) the son of Yü-weng (漁翁), his godfather, had gathered his followers in the mountain and often led raids and caused trouble. Chen Ho suggested sending Lin Tzu-hsüan up the mountain to convince Sekandar, and the king was delighted. Lin Tze-hsüan followed his orders and went up the mountain with a letter from Chen Ho, but Sekandar refused to accept the mediation and tore up the letter. The king and the generals all advocated war, but Chen Ho went against their majority opinion and still wished to resolve the conflict peacefully. Unexpectedly that night, when the king was hosting a banquet for Chen Ho, he received a report from his scouts that Sekandar and his henchmen were coming down from the mountains, seemingly with the intention of mounting a sneak attack on the palace. The king was greatly alarmed and was prepared to go into battle against the enemy in person. Chen Ho advised the king not to panic and to continue with the banquet as normal while setting up an ambush of elite soldiers in key positions to trap Sekandar and capture him alive. When T’ang Ching and other generals heard that there was a battle to be fought, they were eager to exercise their skills and volunteered to help the king. However Chen Ho did not permit them to participate. He said, “This is the king’s internal affairs, we are foreign guests, we should not interfere. We can only boost the king’s morale but cannot take action.” The king followed Chen Ho’s advice and ordered his men to prepare the ambush while continuing with the banquet. When Sekandar heard from his spy that the king and Chen Ho were still feasting and had not prepared any defenses, he signaled his men to advance. When they were close to the wall, he heard battle cries everywhere. He realized that it would not end well and wanted to retreat as quickly as possible, but he was already surrounded by the king’s ambushers and he was captured alive.

The king captured Sekandar and handed him over to Chen Ho to take back as a captive to present to the empire. This was an expression of the king’s friendship and respect for China, and Chen Ho naturally could not refuse.

Based on Cheng Ho’s naval knowledge and experience, a set of charts titled Maps of the Sea Voyages (航海地圖) were produced, consisting of twenty maps on forty pages. The fleet started from Hsia-kuan (下關) in Nanking and left Yangtze River for the sea. Be there shallow water and submerged reefs along the route, they were all meticulously chronicled. This set of charts were reproduced in Wu-pei chih (A Record of Military Matters 武備志) by Mao Yüan-i (茅元儀) who commented: “Roads, villages and national boundaries were recorded in detail and there was no inaccuracy in this set of charts. They were intended to enlighten future generations and to register military triumphs.” Indeed before the time of Cheng Ho, there was certainly no such complete naval records in China. As for the West, there was hardly any naval record that could match Maps of the Sea Voyages (航海地圖) and A Compilation About the Compass (鍼位編), both written by Cheng Ho.

FIVE

Chen Ho bade the king farewell and set sail for the Western Seas. The arrow on the nautical map pointed to Beruwala Harbour (别羅里港) in the Lion Country (獅子國, now known as Ceylon 錫蘭). The large Pao Ships dropped anchors there, and the troops disembarked and walked to the foot of the mountain by the sea. They saw a two-foot-long footprint on the smooth rock, said to be the footprint of Buddha, and in which there was a shallow pool of water that the locals used to dip their hands to wash their faces and eyes. To the left of the Buddha’s footprint was a great temple, the world-famous Upulwan Devalaya Temple (立佛立寺). Emperor Yung-le had specially ordered Chen Ho to give alms here with valuable supplies, so Chen Ho came to the temple first to pay his respects. The monk Sheng-hui (釋勝慧) entered the temple to explain the purpose of their visit, and the foreign abbot hastily led the other monks out of the main gate to welcome the Celestial Envoy. After Chen Ho, Wang Ching-hung and others met with the monks, they went to the main hall and offered incense on behalf of the Emperor. In the hall was a reclining statue of Buddha, the throne was made of fragrant sandalwood and inlaid with all kinds of precious stones. It was truly magnificent. There were also relics of Buddha’s teeth and sarira. It was said that Buddha passed away here. After offering incense, Chen Ho ordered his attendants to lift up and to carry forward the emperor’s gift of alms, which included 1,000 pieces of gold, 5,000 pieces of silver, 50 bolts of various coloured silk fabrics, four pairs of woven gold silk treasure banners, five antique bronze incense burners, five pairs of gold-inlaid bronze flower vases, three pairs of gold-inlaid brass candlesticks, five gold-inlaid lamps, five gold-inlaid red lacquer incense boxes, five pairs of gold lotus flowers, 2,500 catties of incense oil, ten pairs of wax candles, and ten bundles of sandalwood incense sticks. The foreign monks were amazed and delighted with the gifts, and urged Chen Ho and his men to stay and have a vegetarian meal in the scripture tower. The monk Sheng-hui spoke to the monks in Tamil about their mission and the state of Buddhism in China, and the monks found the stories truly extraordinary. Chen Ho had originally planned to visit King Alagakkonara (雅烈苦奈兒) in the palace after lunch, but the monks told him quietly: “I just received a confidential report that the king has heard about the treasures on board the ships and covets them. He has mobilized all the calvary to attack and plunder. The king’s elephantry is especially ferocious and invincible. The Celestial Envoy should return to the ship soon not to risk being harmed. Let me try to persuade him to change his mind. It will not be too late to meet the king on your return journey.” Chen Ho took the monk’s advice and immediately led the troops back to the ship. As they were about to up-anchor, they saw a cloud of dust rising in the distance. The foreign king did indeed arrive at the bank with his army and elephant try, but the Pao Ships had long left the shore and sailed away with the wind, disappearing in the far horizon. The foreign king could only gaze at the sea and sigh.

SIX

Heading northwest from Beruwala Harbour, the fleet passed through the country of Quilon (小葛蘭國 also known as Kollam in India), arriving at the country of Cochin (柯枝國 also known as Kochi). The king of Cochin, Keyili (可亦里), had paid tribute in the third year of the Yung-le reign and sought a name for a large mountain in his country. This time, Chen Ho was specially ordered to confer on the king an imperial seal and to designate the large mountain as Chen-kuo Mountain (鎮國山). A stele with inscription was also bestowed and erected in the mountain.

After sailing north for three days, the Pao Ships arrived at Calicut (古里國 also known as Kozhikode), the largest country in the Western Seas. In the third year of the Yung-le reign (1405), the ruler of Calicut, Saamoothiri (沙米的喜) had sent envoys with tribute to the Chinese court in the company of Yin Ch’ing (尹慶). On this occasion, Chen Ho was ordered to confer on him the title of King of Calicut, as well as awarding him with seal, silk fabrics, and other gifts. In addition, a pavilion housing a stele was built in the country and on the stele was inscribed: “Your Majesty has traveled over 100,000 li (over 30,000 miles) from your kingdom to China. However, just like our country, you have abundant resources here and the people live happy and peaceful lives. A monument is erected here to proclaim this to the world. This stone inscription shall remain for posterity.” The king expressed his gratitude for the grace of the Celestial Empire and held a banquet in honour of Chen Ho and his generals.

From Calicut, the fleet split up, with one team heading to Lamuri (南巫裡 also known as Malabar, a region on the west coast of the Indian peninsula) and Hormuz (忽魯謨斯 also known as Ormuz, a region at the mouth of the Persian Gulf), led by Lin Tze-hsüan. Another team crossed the ocean and went to Mogedoxu (also known as Mogadishu 木骨都束), Brawa (不刺哇), Djobo (竹步), and Malinde (麻林) in Africa, led by T’ang Ching. Chen Ho led a large team straight to Djofar (祖法兒) and Aden (阿丹/亞丁), and then to Mecca (天方) for pilgrimage. The three teams agreed to meet on their return at the port of Beruwala before advancing further east.

Lin Tze-hsüan led his team through Lamuri and arrived in the country of Hormuz. That country had always been engaged in trade with China by land and sea and the king knew well that China was the largest country in the east. Therefore, he treated Lin Tze-hsüan and his team with great respect. The trading conducted by the Pao Ships in this place was huge in amount, and they obtained rare birds and animals as well as remarkable treasures.

The team led by Chen Ho went through Djofar and arrived first in the country of Aden, which was the most famous distribution hub for pearls and precious stones. The Pao Ships conducted a lot of trades and received in exchange all kinds of exotic articles, such as large pearls, huge cat’s eye stones, and branch coral of over two feet tall. The king treated the envoys from the Celestial Empire with great hospitality. Apart from personally leading his ministers to welcome them at the seaside, he also entertained them with sumptuous banquets and musical performances by female musicians. Additionally, he had a golden crown made, studded with various pearls and precious gems, as a gift for the Emperor of China.

The Pao Ships departed from Aden and arrived at the Islamic holy site of Mecca. Chen Ho, representing the Chinese emperor, presented many valuable gifts to the king of Tianfang (天方), who in turn presented precious treasures and hosted a grand banquet for the envoy. Next day, Chen Ho and the chief imam Hassan led the generals to Paradise Mosque (天堂禮拜寺) for pilgrimage, which is considered the most important act for Muslims. Chen Ho, Hassan, Ma Huan, and others were all Muslims and naturally felt excited. After the pilgrimage, Chen Ho led the team to the famous trading city of Jeddah (報達城) for sightseeing and trading. Jeddah was a large well-known city, and Chen Ho and his team had a fruitful trip there.

Among the three teams of Pao Ships, the one led by T’ang Ching had the most difficult journey. Their voyage took twenty days before finally reaching Mogedoxu. The country was barren, with no plants or trees, the fields were infertile yielding very little harvest. There was severe drought with no rain. Although the chieftain was very hospitable, no one was interested in this barren land. Moving south to Brawa, the land was vast but saline, with no cultivated fields. The locals only fished for a living and their culture was underdeveloped. Further south, Djobo and Malinde were similar to Brawa. Trade with these four countries was very limited; the only gain was purchasing items rarely seen in other countries such as lions, leopards, zebras, rhinoceroses, ostriches, giraffes, ambergris and others. T’ang Ching originally intended to explore further south, but he realized that the shipping schedule was nearing its end so he had to sail back to Beruwala to rendezvous with the other two teams.

(This passage is a narration. When filming, places with good scenery should be chosen and captured as flashes to avoid dragging on.)

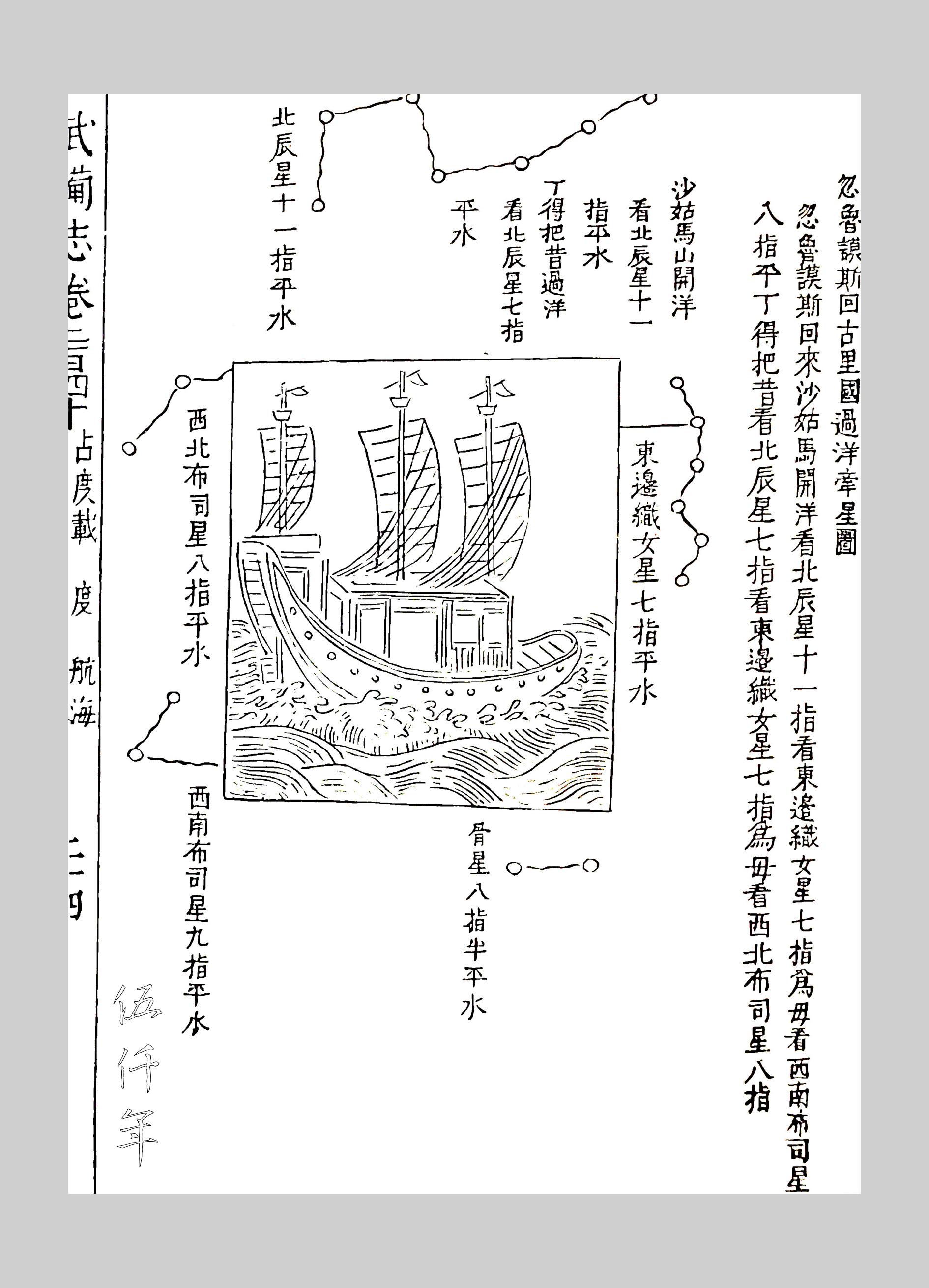

In daytime, Cheng Ho used the hands on the compass to position and direct, at night, he used the stars for orientations. In A Record of Military Affairs (武備志) by Mao Yüan-i, the Navigational Star Chart by Cheng Ho was reproduced. Traveling from one place to another, such a chart is used to gauge the stars as to determine the ship’s position. Illustrated here is a chart used for traveling from Hormuz to Kozhikode. Hormuz is at the mouth of Persian Bay, also known as Ormuz. Kozhikode is also known as Calicut in India. Cheng Ho did indeed master the knowledge of astronomy and geography that were imperative to marine navigation.

SEVEN

T’ang Ching led his team back east and arrived at Beruwala Harbour, only to find no Chinese ships in the harbour. He hurried to the Upulwan Devalaya Temple to ask the abbot and found that the other two teams had not yet arrived. When the king heard about the arrival of the Pao Ships, he quickly led his people to the harbour to welcome them. T’ang Ching saw that the king’s attitude was amiable without ill-intent, so he cautiously approached him. However, the abbot warned him about the king’s deceit and to be careful. The king invited T’ang Ching and his generals to a banquet. T’ang Ching brought carrier pigeons as a precaution and ordered his troops to guard the ships well to prevent any surprise attacks. If there was any alarm, he would first release the homing pigeons to return, and they would raise anchor to leave shore and prepare for battle.

When T’ang Ching and his men arrived at the capital Kandy (堪地), he saw that the elephantry guarding the city gates was proficient and skilled. He thought to himself that if they were to engage in battle, he would need to come up with a winning strategy to defeat the elephantry.

During the banquet, the king enquired in detail about the destinations and missions of the separate fleets. T’ang Ching knew that the king had ulterior motives, so he deliberately exaggerated the quantity of treasures on Chen Ho’s fleet. The king, after hearing this, realized that most of the treasures and exotic goods were on Chen Ho’s fleet. He did not want to make a move on T’ang Ching to avoid alerting Chen Ho and driving him away. T’ang Ching saw through the king’s thinking and only then began to drink with ease. The host and guests all enjoyed a merry time. On his way from Kandy to Beruwala, T’ang Ching had witnessed a tamed elephant carrying logs who suddenly turned wild and ran towards the forest, disobeying its trainer’s commands. The trainer calmly used wet firewood to block its path, and when the elephant saw the smoke rising, it dared not rush forward and hesitated, eventually returning to the lumberyard, driven by the trainer. T’ang Ching was overjoyed to witness this, as he realized that in future battles against the elephantry, he could use fire to attack and win, without further worry.

As T’ang Ching contemplated, Chen Ho’s fleet was in a perilous situation, being caught in a hurricane and hit by giant waves like mountains. Chen Ho and the other officers were at their wits’ end. The Muslim imam Hassan ignored the danger to his life and struggled to the deck to pray to God. The huge waves crashed onto the deck and nearly washed him into the sea, but he held on tightly to the rope and continued to pray. Chen Ho, Ma Huan, and the other Muslim officers stumbled to the deck, and all prayed with him. Meanwhile, the helmsmen and sailors were also battling the wind and waves with all their might. After half a day of labour, the fleet finally broke out of the hurricane’s range, and the wind and waves gradually subsided as the sky cleared up. Upon inspection of each vessel, there was only minor damage, and no sailor was lost. Soon after, they spotted Lin Tz’u-hsüan fleet in the distance. Chen Ho quickly sent a homing pigeon with a message, and Lin Tze-hsüan reciprocated with another pigeon. The two fleets met and sailed together towards the port of Beruwala.

Next day at dawn, the fleet entered Beruwala Harbour. T’ang Ching had already rowed over on a fast boat to greet them. He boarded the ship Ch’ing-ho, reporting to Chen Ho about the situation. Chen Ho was delighted to hear that the King of Lion Country had changed his attitude, but T’ang Ching warned him not to trust him easily and advised him to be always careful. Chen Ho cautioned him to prioritize peace and treat others with sincerity, without being too suspicious. T’ang Ching was unhappy and left.

Shortly after, the king arrived on an elephant to greet Chen Ho and his party, and they departed to the capital city for a banquet. Chen Ho also presented gifts from the Chinese emperor. The guests and host enjoyed themselves until sunset before the banquet ended. T’ang Ching secretly surveyed the city’s layout and architecture, which appeared strong, but there were far fewer soldiers guarding the city than usual, which seemed suspicious. On their return from the capital city to Beruwala Harbour, as the sky darkened, Chen Ho, his generals and two thousand soldiers came to a gorge. They suddenly discovered that the mouth of the gorge had been blocked by logs. Chen Ho realized that they had fallen into an enemy trap. He quickly led his generals to the top of the mountain, they looked out, and saw enemy troops carrying torches, heading straight towards the beach like a dragon. Fortunately, T’ang Ching was vigilant and had instructed his men to bring signal cannons with them. From the mountaintop, they fired the signal cannons to warn the crew on the ships to be on high alert. Upon hearing the cannon fire, the crew on the vessels immediately raised anchor and sailed away from the shore. When the enemy troops reached the beach, they boarded their warships and attempted to attack the Chinese ships, but they were met with arrows and stones that came like locusts from the ships, and could not get close.

When Chen Ho saw that the giant fleet had been prepared, he knew it would be extremely difficult for the enemy vessels to win. He ordered T’ang Ching to lead his officers and one thousand soldiers to capture the capital. Chen Ho himself led another one thousand soldiers to defend the mountaintop and used signal cannons to command the sailors on the ships from afar. The enemy soldiers saw that the mountaintop was occupied and tried to charge up the mountain several times but were repelled by the Chinese soldiers rolling logs and stones down on them so they could not rush up.

T’ang Ching led his troops and horses quietly and quickly, entered the capital by climbing the back wall, and captured alive the sentries guarding the gate. The Chinese soldiers then poured in. The king had dispatched all his soldiers and generals to rob the Pao Ships, while he stayed in the palace to wait for the good news. Unexpectedly, T’ang Ching launched a surprise attack on the capital, sneaked into the palace by climbing the wall, and caught the king off guard. The king was captured alive. The Chinese soldiers took control of the capital.

The foreign soldiers at the harbour tried to ram their warships into the Chinese fleet many times but failed to make headway. Chen Ho noticed that the enemy had been in action for four hours, and their vigour was exhausted. He swiftly issued order by signal cannon to the troops on the ships to counterattack. The foreign soldiers lost ground, abandoned their boats and retreated to the shore. They were confident that their elephantry was invincible and unperturbed by the landing of the Chinese soldiers. However, T’ang Ching had already taught the ship’s troops the technique of fire attack. They had brought fire and wet firewood with them, which they ignited on the beach. The sea breeze blew the smoke and fire towards the elephantry of the enemy. The elephants could not stand their ground and turned around to flee. The Chinese soldiers took advantage of the situation and fired rockets at the elephants, causing many foreign soldiers to be trampled to death by the panicked animals.

The foreign soldiers fled in disarray towards the capital, and dawn was about to break. T’ang Ching looked out from the city walls, even though the foreign soldiers had been defeated, there were still thirty to forty thousand of them. If they continued to fight to the end, both sides would suffer heavy casualties. He suddenly came up with a plan. He untied the king, helped him sit on the throne, and spoke to him eloquently: “Our troops have landed and fought mightily. Your army has retreated in defeat. China has no intention to invade your country. If your majesty can personally go up to the city tower and order your soldiers to lay down their weapons, our imperial envoy will forgive the past and establish diplomatic relations with your country. Your majesty can also protect your country and your throne.” The king agreed to this proposal, immediately went up to the city tower, and ordered the foreign generals to lay down their weapons and not to fight anymore. T’ang Ching also fired a signal cannon to inform Chen Ho and his troops that the battle had ended. Chen Ho led his men into the city, met the king, and learned that T’ang Ching had turned hostility into the beginning of friendship by using diplomacy. Chen Ho was very pleased and praised T’ang Ching highly. The king saw that Chen Ho was willing to let bygones be bygones, he deeply regretted his actions and was willing to establish diplomatic relations with China. Chen Ho took the opportunity to invite him to visit China for sightseeing, and he accepted the invitation eagerly, immediately packing his belongings and joined Chen Ho on the voyage.

All the generals deserved credit for meritorious service this time, but T’ang Ching’s contribution was the greatest. Victory was achieved by the generals without shedding blood, and everyone rejoiced.

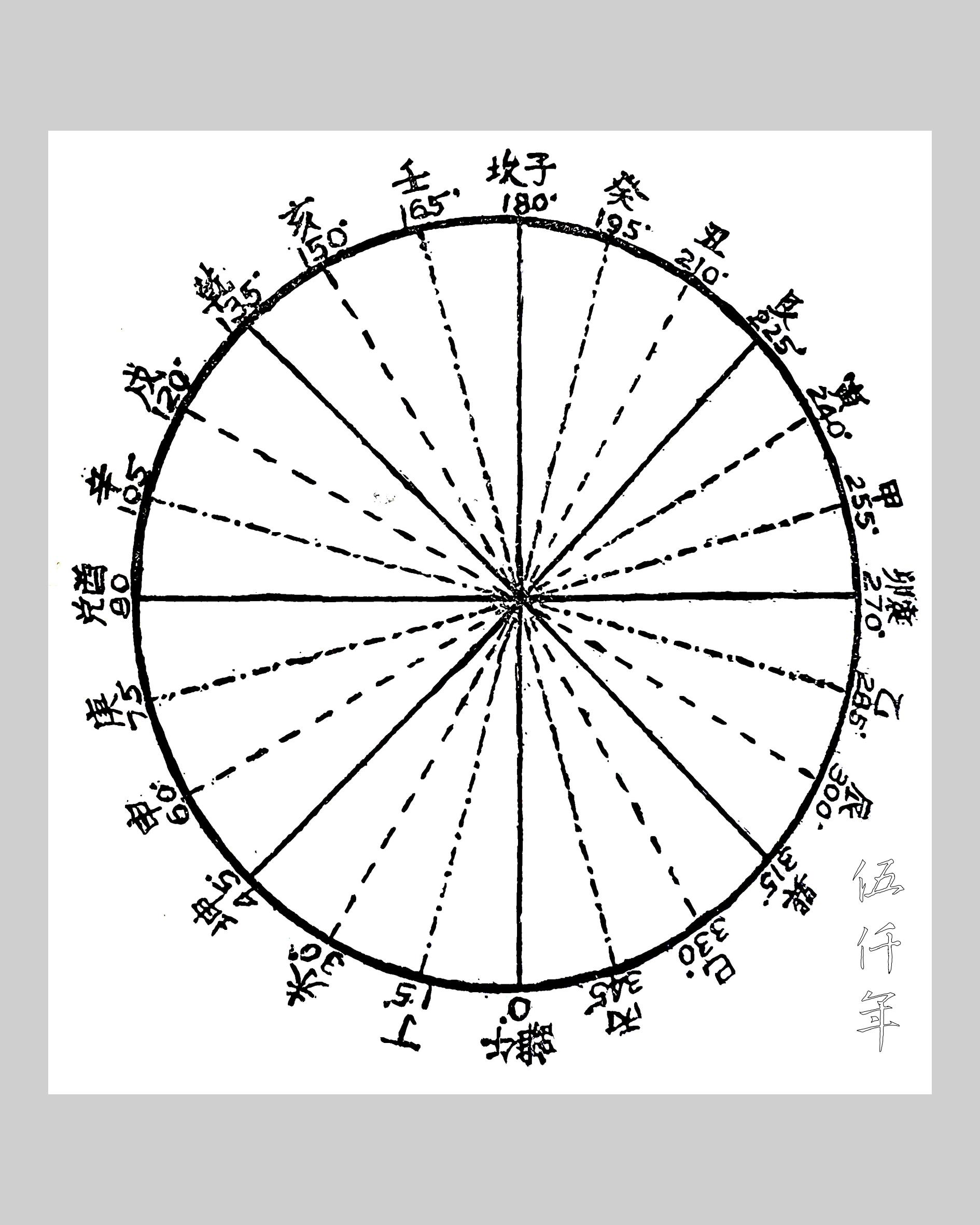

This is a diagram of the compass used by Cheng Ho. During daytime, the hands of the compass direct the course of navigation. An example, it was so written on the Maps of the Sea Voyages: “Voyaging from Sumatra, the hands are to be set on the markings of ch’ou (丑) and ken (艮), i (乙) and ch’en (辰). Between three and five in the morning, the ship will smoothly arrive at Chi-shui Bay (急水灣), water is shallow at Pa-lu-t’ou (巴碌頭), use the markings of ch’en (辰) and hsün (?).” Cheng Ho wrote A Compilation About the Compass (鍼位編) which is now lost. Compass was originally invented by the Chinese, references about the compass in European and Arab manuscripts did not appear any earlier than 1200 AD. Chinese reference about the compass appeared in P’ing-chou k’ei-t’an (萍洲可談) by Chu Yü (朱彧) in the first year of Hsüan-ho (宣和 1119 AD) during the reign of Hui-tsung Emperor (宋徽宗) of the Sung Dynasty.

EIGHT

The Pao Ships departed from Beruwala Harbour and passed by Melaka. Each vessel took stock of its goods, money, and food, sailing southeast to Old Port (淡港/舊港 also known as Palembang) in Selat Banka 彭家們 ( also known as Bangka Strait). There, the chieftains Ch’eng Tz’u-i (程祖義), Liang Tao-ming (梁道明), and Shih Chin-ch’ing (施進卿) were already at the port to welcome them. It turned out some time earlier they had sent their sons and nephews to China to pay tributes. Chen Ho met with them separately and pacified them with kind words. While no one was paying attention, Shih Erh-chieh (施二姐) pulled Fei Hsin to the stern of the ship and quietly told him: “Ch’eng Ts’ui-i has gathered pirates from various places, they seem to have a plot. Please tell the Imperial Envoy to be careful.” Fei Hsin instructed her to keep an eye on things and report any suspicious activities. Shih Erh-chieh then departed with a courteous farewell.

Fei Hsin knew that T’ang Ching was biased in favour of Cheng Ts’ui-i. He did not dare tell him what Shih Erh-chieh had said but quietly reported to Chen Ho. Chen Ho ordered T’ang Ching to closely monitor Cheng Ts’ui-i’s activities. However, T’ang Ching refused to believe it and advised Chen Ho: “Do not easily believe baseless rumors, even though Ch’eng Tz’u-i was a former pirate, he had sent his son back to China to offer tribute. If the court showed leniency and offered kind words to pacify him, he would not remain stubborn”. Chen Ho laughed and said, “Before, I advocated peace with Java, but you advocated military action. Now that I want to eliminate a major threat in the region, you advocate conciliation! Very well, I will listen to you and send you to conciliate with Cheng Tz’u-i. How about that?” T’ang Ching readily took on the task and went to the old port Palembang to meet Ch’eng Tz’u-i.

After hearing out T’ang Ching, Ch’eng Tsu-i thought that Chen Ho had fallen for his treacherous plan. He pretended to show his loyalty and willingness to follow the envoy back to the capital, leaving his son Shih-liang (士良) a hostage in Nanking, if he ever committed piracy again, the court could execute his son. T’ang Ching then asked: “If you are so loyal, what is the meaning of gathering the pirates from all over?” Ch’eng Tz’u-i quickly countered: “I gathered them to show the military might of the court and to inspire fear in their hearts, so that they would turn over a new leaf and become good citizens. Commander T’ang, please do not believe any rumours and misunderstand my heartfelt intentions.” T’ang Ching saw that he was very sincere and could not help being convinced. Ch’eng Tsu-i used the opportunity to ask T’ang Ching to help invite Chen Ho, Wang Ching-hung, and other commanders to a banquet at the Old Port the following evening, so that he could persuade all the pirates to surrender to the Imperial Envoy. When T’ang Ching heard this, he was overjoyed and immediately went back to Selat Banka to report to Chen Ho.

Shih Chin-ch’ing heard about the news of Ch’eng Tsu-i’s invitation to Chen Ho and his generals to a banquet. He knew there was a ploy, he and his daughter, Shih Erh-chieh, tried every possible way to find out what conspiracy the pirates were plotting, but to no avail.

On the morning of the banquet, the king of West Java sent a messenger to confer with Chen Ho. The king of West Java had recently sent his emissary to Siam and the vessel was seized by Ch’eng Tsu-i during the voyage. Knowing that Ch’eng Tsu-i had already pledged loyalty to Chen Ho, the king of West Java asked for the release of his emissary. Chen Ho was furious on hearing this, but he did not show any sign, in case Ch’eng Tsu-i became suspicious.

That afternoon, Shih Chin-ch’ing brought his daughter Shih Erh-chieh to see Chen Ho. According to the information they gathered, the followers of Ch’eng Tsu-i had been busy since early morning, as if they were up to something. They asked Chen Ho to keep an eye on them. When Shih and his daughter were on their way back, they caught a glimpse of Ch’eng Tsu-i and the pirate leaders sitting on a boat at Old Port having a secret meeting in a sneaky manner. Shih Erh-chieh was a proficient swimmer, so she dived over to the boat to eavesdrop on what they were saying.

That afternoon, Ch’eng Tsu-i and the pirate gang finished their secret meeting. They went directly to the ship Ch’ing-ho to personally invite Chen Ho, Wang Ching-hung, and the other generals to a banquet at the Old Port. They further arranged for the gang members to deliver food and liquor to each ship to reward the soldiers. Although Chen Ho knew there was a ploy, he believed he must take a risk according to the saying: “How can you find the tiger cub if you don’t enter the tiger’s den?” So he led the generals to disembark from the vessel. Just as they were about to transfer to Ch’eng Tsu-i’s boat to go to the Old Port, suddenly, a person emerged from the water and shouted, “Imperial Envoy, don't fall for Ch’eng Tsu-i’s trap!” Chen Ho took a closer look and saw it was Shih Erh-chieh.

Soaking wet and clinging to the rope ladder, Shih Erh-chieh climbed aboard and reported in detail to Chen Ho about Ch’eng Tsu-i’s conspiracy that she had overheard. With his plot exposed, Ch’eng Tsu-i took advantage of the moment when no one was paying attention and slipped away in his small boat. By the time Chen Ho realized what had happened, Ch’eng had gone far away. It was already dusk, and Selat Bangka was gradually shrouded in thickening fog, making it impossible to see the opposite shore. Fearing an ambush by pirate ships in the fog, Chen Ho quickly ordered the fleet to move quietly out of the strait.

Sure enough, Ch’eng Tsu-i and the pirate leaders came in the fog to attack the fleet, but to their surprise, the Pao Ships were already anchored outside the strait. Once Chen Ho reckoned that the pirate ships were in the sea, he lined up the fleet’s giant rudders to block the strait. When the pirate ships closed in, the troops used strong crossbows to shoot fire arrows or cannon stones at the pirate ships. Many pirate ships were burned or sunk as they were unable to escape from the strait. When the fog cleared at dawn, Chen Ho ordered the troops to launch fast boats into the water to hunt down the pirate ships. Ch’eng Tsu-i knew he was trapped, he could only abandon his boat and fled to the shore with the pirate leaders. T’ang Ching and the other generals immediately led their troops ashore to capture them.

Ch’eng Tsu-i regularly terrorized the local population, his oppression was deeply resented by overseas Chinese. Shih Chin-ch’ing rallied the local population to help the troops in the siege. They tracked down Ch’eng Tsu-i and the pirate leaders in the mountains and captured them alive. No one managed to escape.

After the great victory, Chen Ho rescued the emissary of the king of West Java from Ch’eng Tsu-i’s stronghold. He sent Ch’ien Pin to escort the emissary and the messenger back to Java. Ch’eng Tsu-i and the pirate leaders were all escorted to the ship Ch’ing-ho and confined on board, awaiting punishment upon their return to China. The locals of Old Port thanked Chen Ho for eliminating the scourge of their area and hosted a feast with lamb and fine wine for Chen Ho, his generals, and the entire army. That night, the soldiers and the civilians drank heartily, enjoying themselves to the full before dispersing.

When Chen Ho set sail to return to China, thousands of overseas Chinese came to the port to see him off. At that moment, a boat sailed into the harbour, and it turned out to be Ch’ien Pin accompanying the king of West Java. Ch’ien Pin, wearing a long sword, reported to Chen Ho that the king of West Java thanked the imperial envoy and was ready to join the ship to visit China to pay tribute. Chen Ho was overjoyed and hurriedly welcomed the king of West Java aboard his own vessel. The king of West Java was once extremely arrogant, but now he was full of smiles and apologized to Chen Ho repeatedly.

Amid the sound of cannons, the giant ships left the port and set sail for home. Onshore, firecrackers crackled as overseas Chinese raced their small boats to escort them part of the way. Chen Ho leaned against the railing and smiled at the king of West Java and T’ang Ching, saying: "This is not a scene that can be attained from invasion and conquest!"

The Pao Ships sailed further and further away, contrasting with the white clouds in the sky. A great mission in history was finally accomplished.

Front cover of Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen Ho by Mr. Yao K’o, printed in book form by the Production Committee of Central Pictures Corporation in Taiwan

First page of Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen Ho by Mr. Yao K’o, printed in book form by the Production Committee of Central Pictures Corporation in Taiwan

Inside page of Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen Ho by Mr. Yao K’o, printed in book form by the Production Committee of Central Pictures Corporation in Taiwan

Related Contents:

Movie Scenario of Admiral Chen Ho(鄭和) and Mr. C. Y. Tung(董浩雲)