Tung Tso-pin (董作賓) was a distinguished scholar of oracle bone studies in the last century. His calligraphy that used oracle bone script was a novelty at the time. Now they are cherished and collected. He also liked to use oracle bone script for his seal carvings, after the artistic school of late Ch'ing and early Republic that favoured deploying different calligraphic expressions into the carving of seals. He was thus able to achieve a unique outlook for his seal carvings. Tung Tso-pin's devotion to oracle bone script started from his participation in the excavation of the Yin Dynasty Ruins. Therefore as we display a piece of oracle bone script seal by Tung, we also show a family letter he wrote during the excavation of the Yin Dynasty Ruins, to reveal the origin of his interest, and to augment additional appeal to our visitors.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

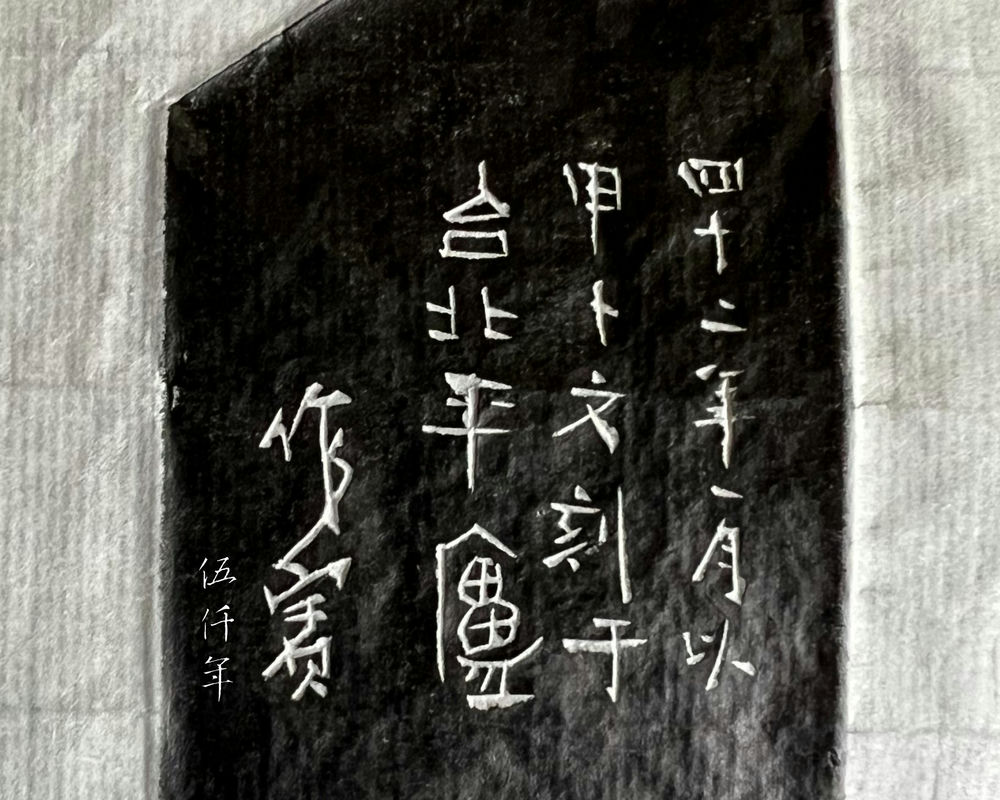

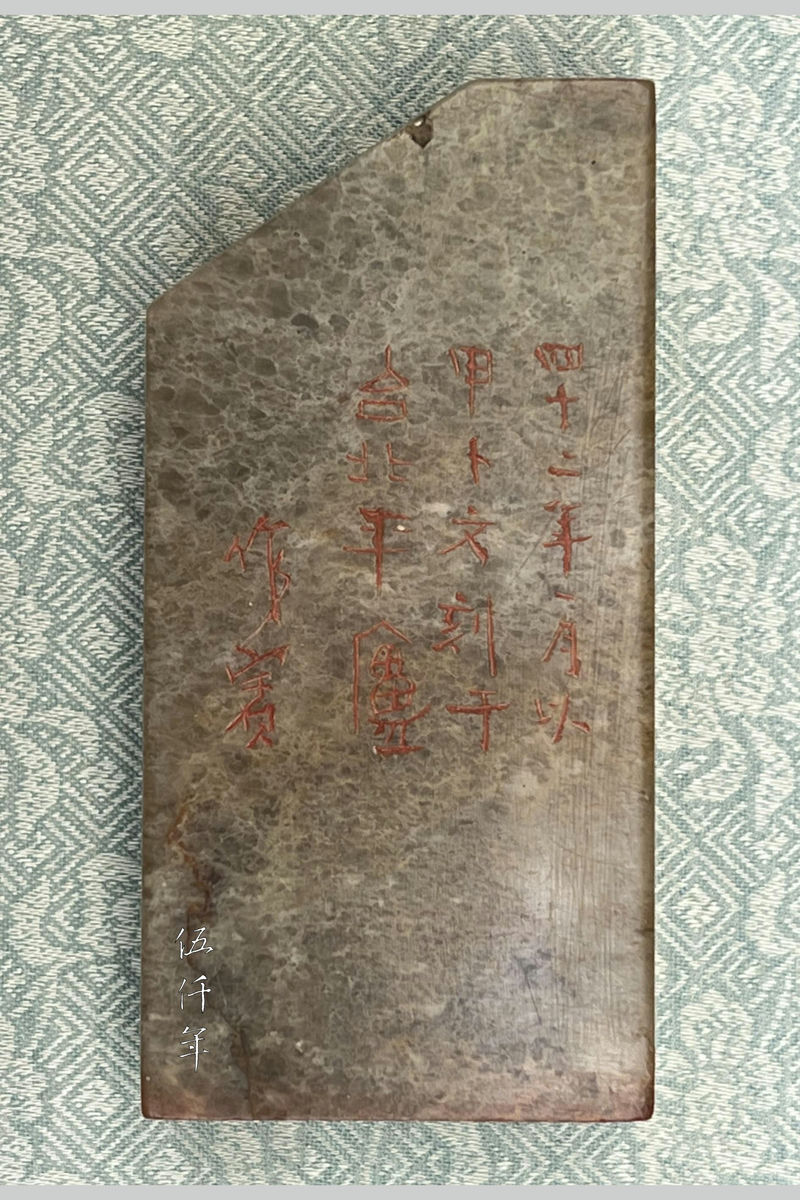

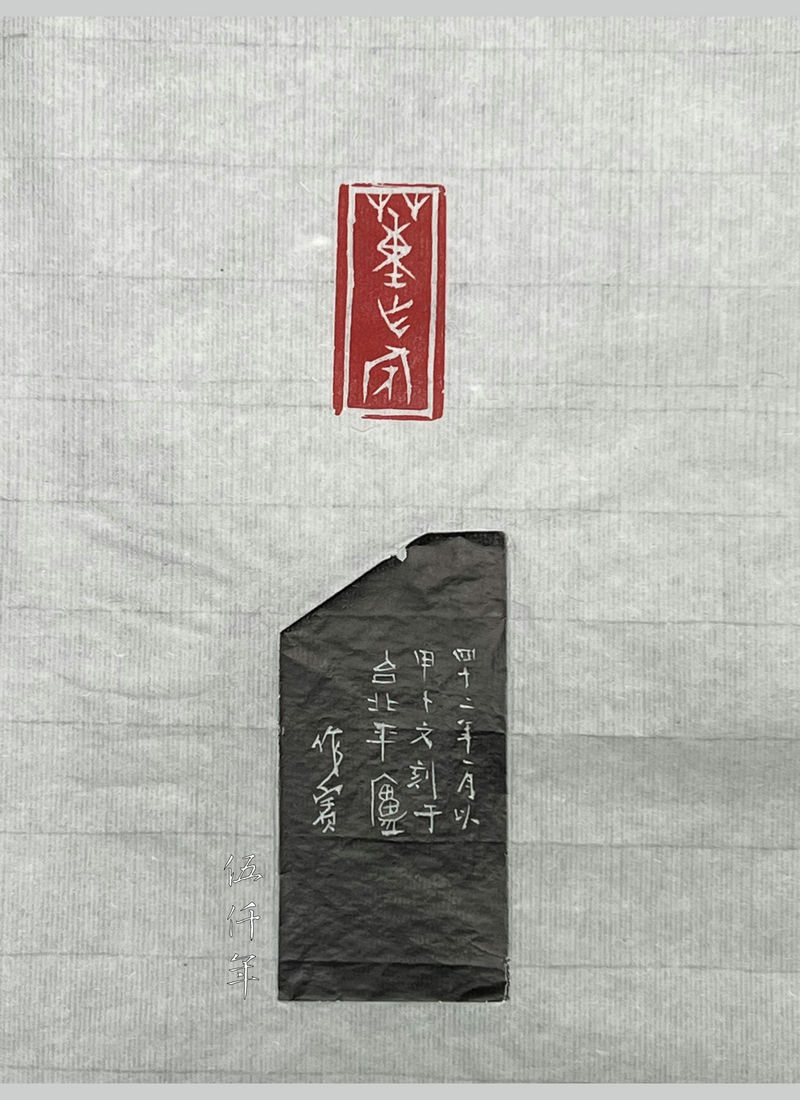

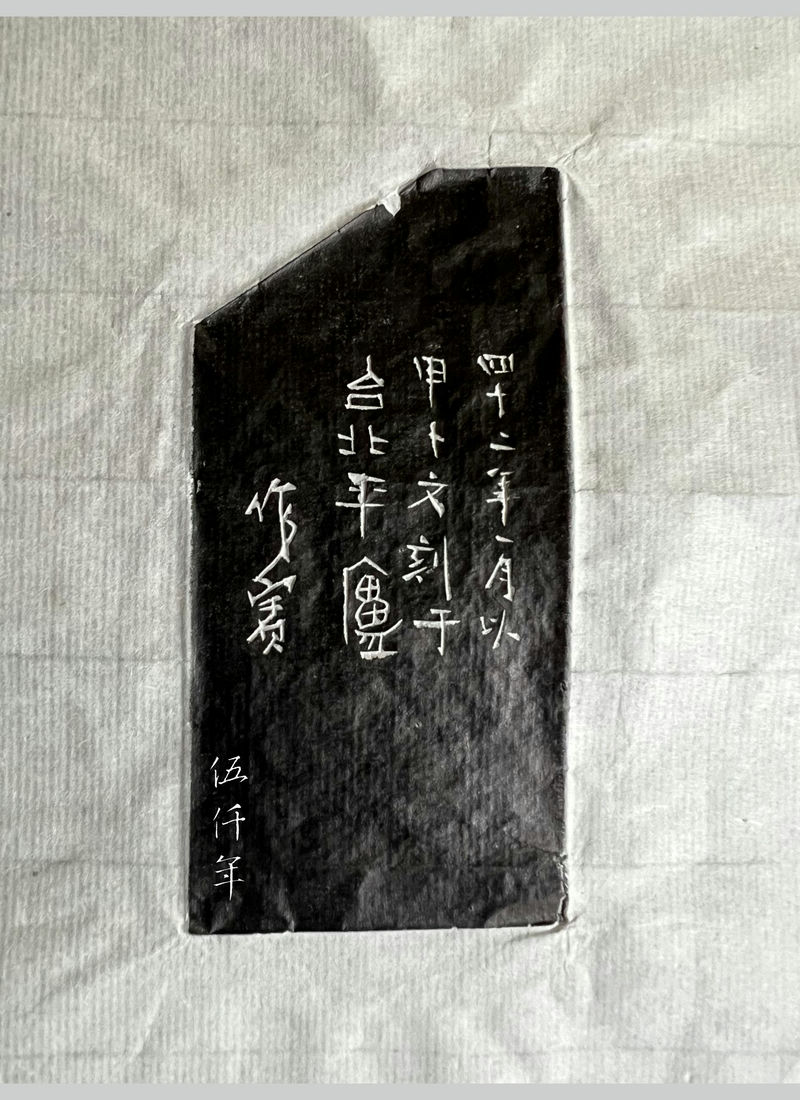

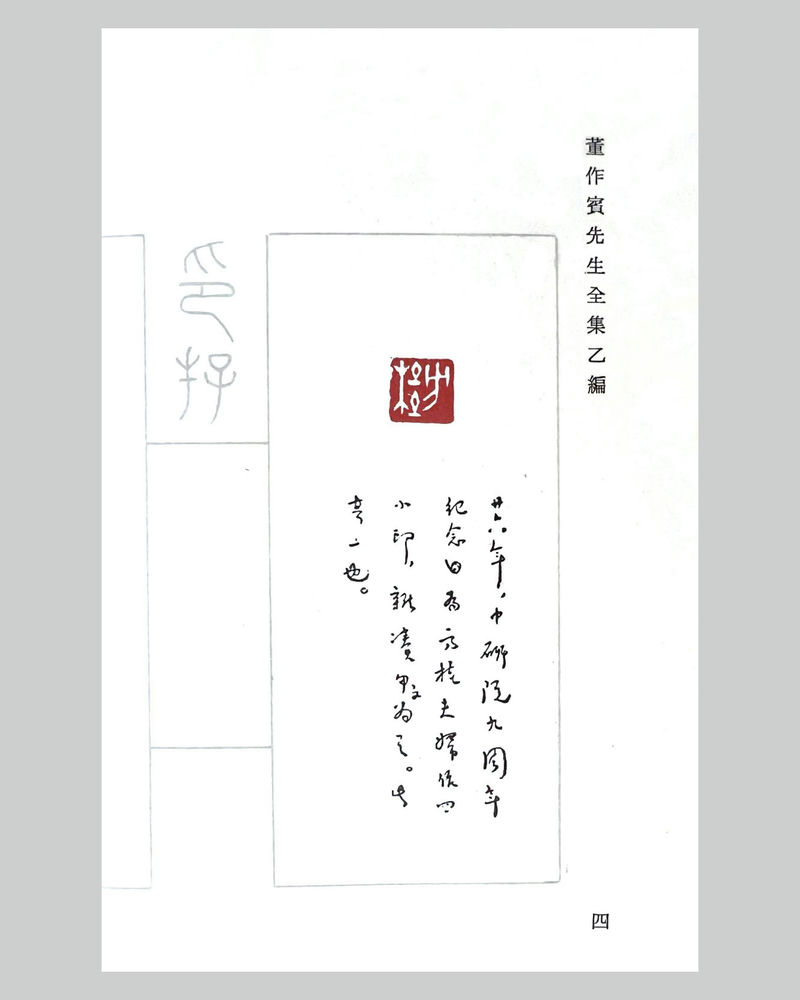

Side inscription ink rubbing of the oracle bone script seal by Tung Ts’o-pin

In the 52nd year of the Republic of China (1963), Tung Tso-pin passed away in Taipei. It has been one sexagenary cycle since then. When it comes to archaeologists or etymologists of the 20th century, Tung Tso-pin’s name is always included. However, as time passes, people have become less familiar with the value of his academic achievements.

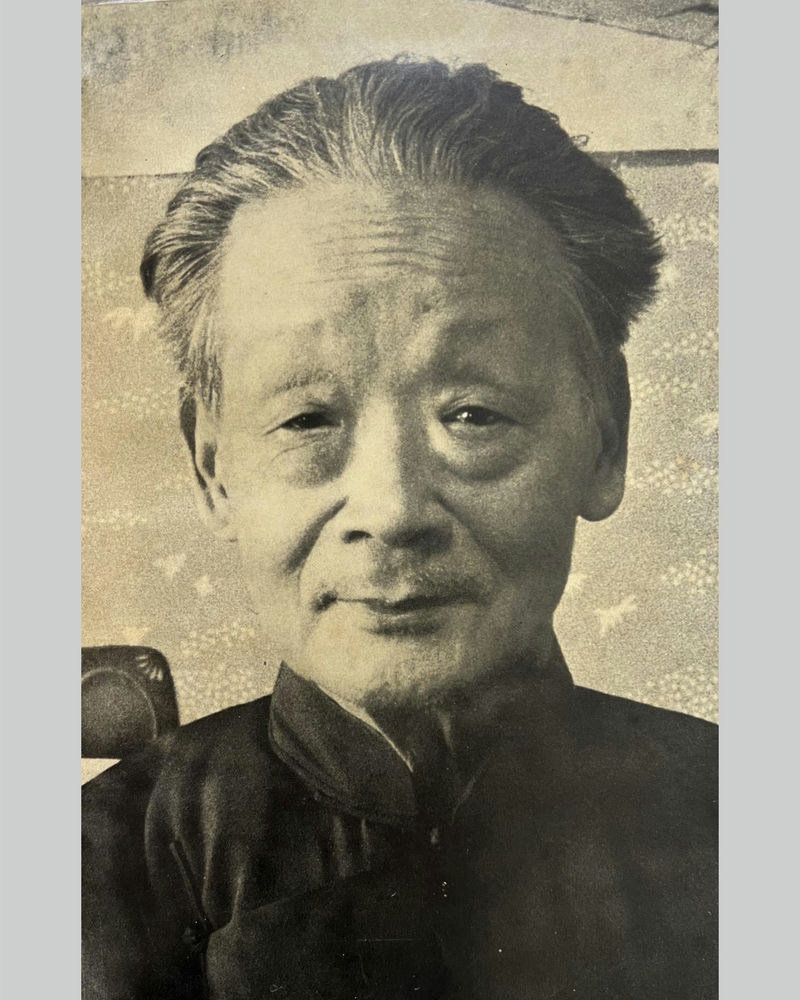

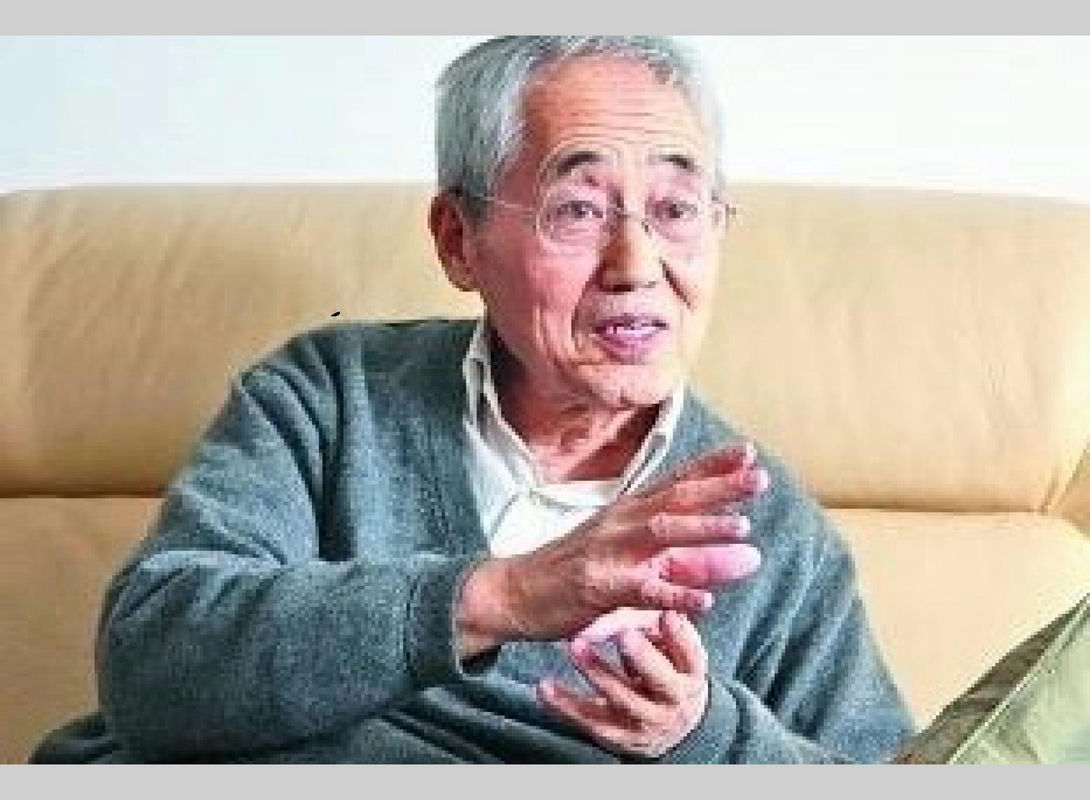

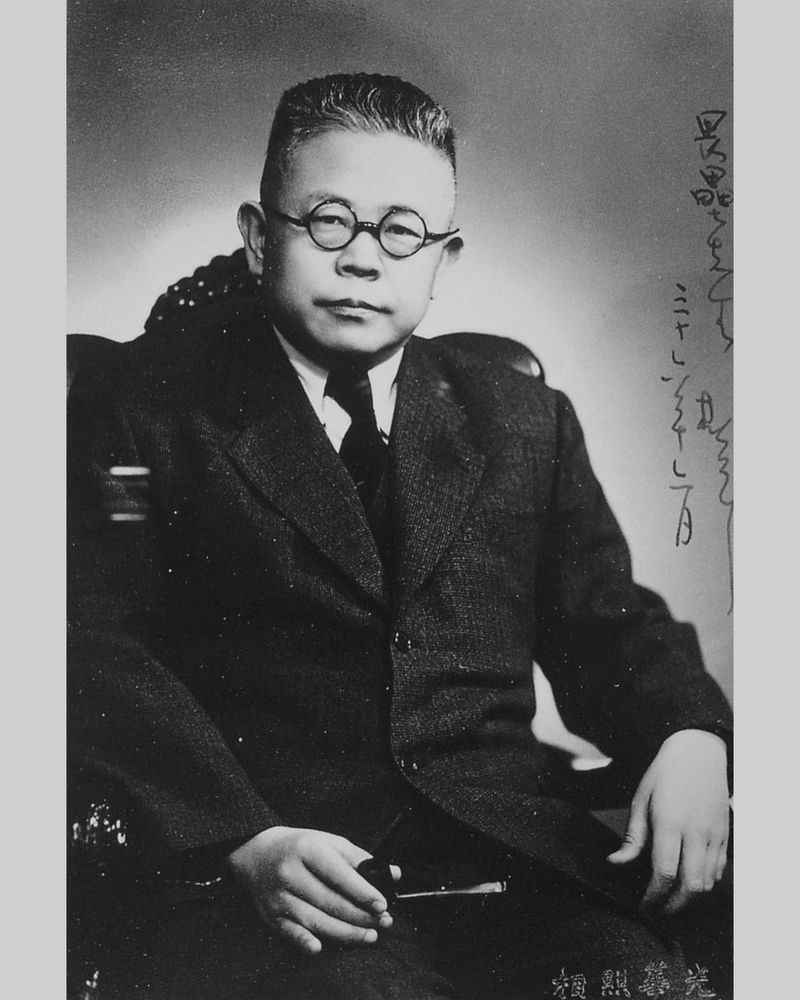

Portrait of Tung Tso-pin

If one reads the commemorative article Mr. Tung Tso-pin of Nan-yang and Modern Archaeolog (南陽董作賓先生與近代考古學) written by Li Chi (李濟) in March of the 53rd year of the Republic of China (1964), one can get a general idea of Tung’s contributions. Extracts from the article read:

“My first impression of him was that he was quick to accept modern academic perspectives, and the academic questions he raised fully met the requirements of modern scholarship. For example, the report he completed on the first trial excavation of the Yin Dynasty Ruins (殷墟) and the transcripts and notes on the newly acquired oracle inscriptions not only possessed extremely concise reporting style (the entire text can be said to have no superfluous words), but the final question he raised was:

‘Are the oracle bone scripts we see today only divination texts from the period of Wu-i (武乙 1147-1112 BC) to Ti-i (帝乙 1101-1076 BC), and there are no relics from earlier than Shang dynasty? (商朝, Shang dynasty is also known as Yin dynasty) If there is none, then outside of the Yin Dynasty Ruins (殷墟), could there exist similar divination texts in other capitals that were destroyed by floods and forced to relocate?’

He laid the theoretical foundation for our continual excavation of the Yin Dynasty Ruins. ...

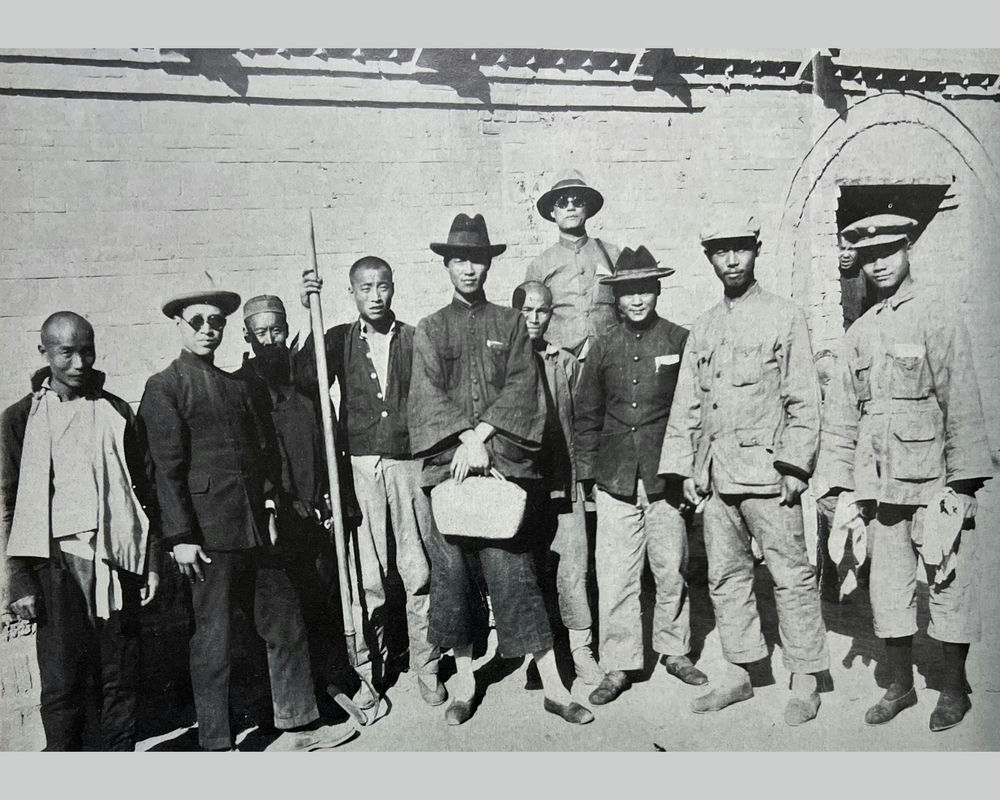

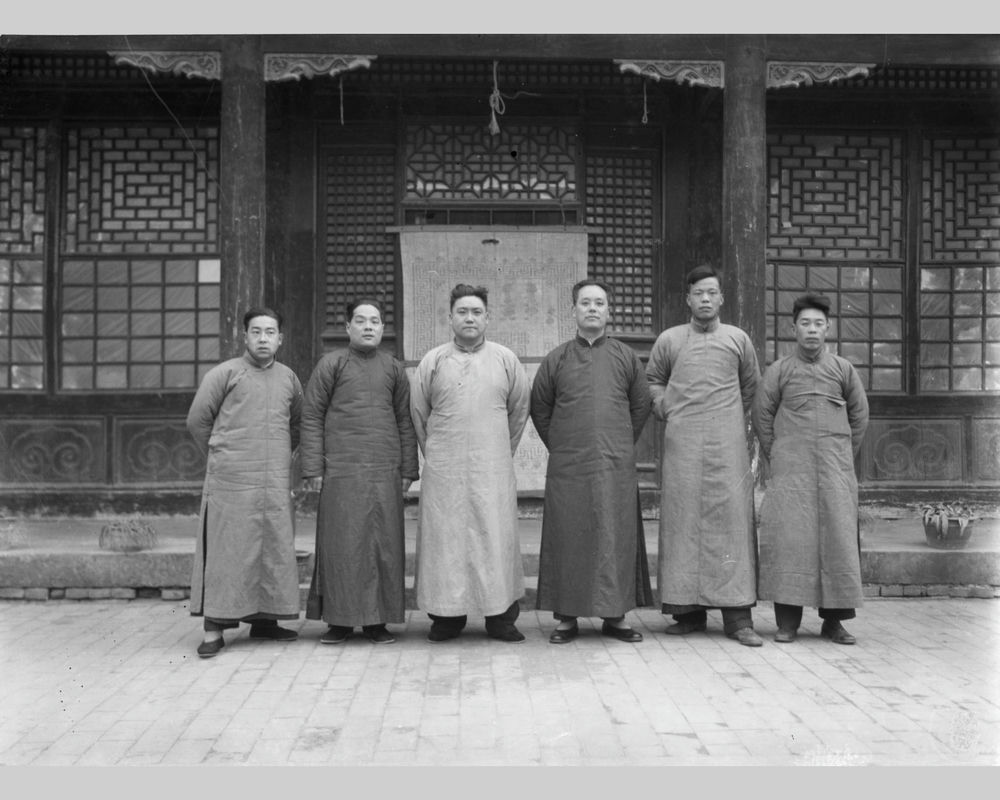

Group portrait of the archaeological team taken on 12 October 1928, one day before the first excavation of the Yin Dynasty Ruins. Tung Tso-pin standing third from the right. Photograph courtesy Academia Sinica

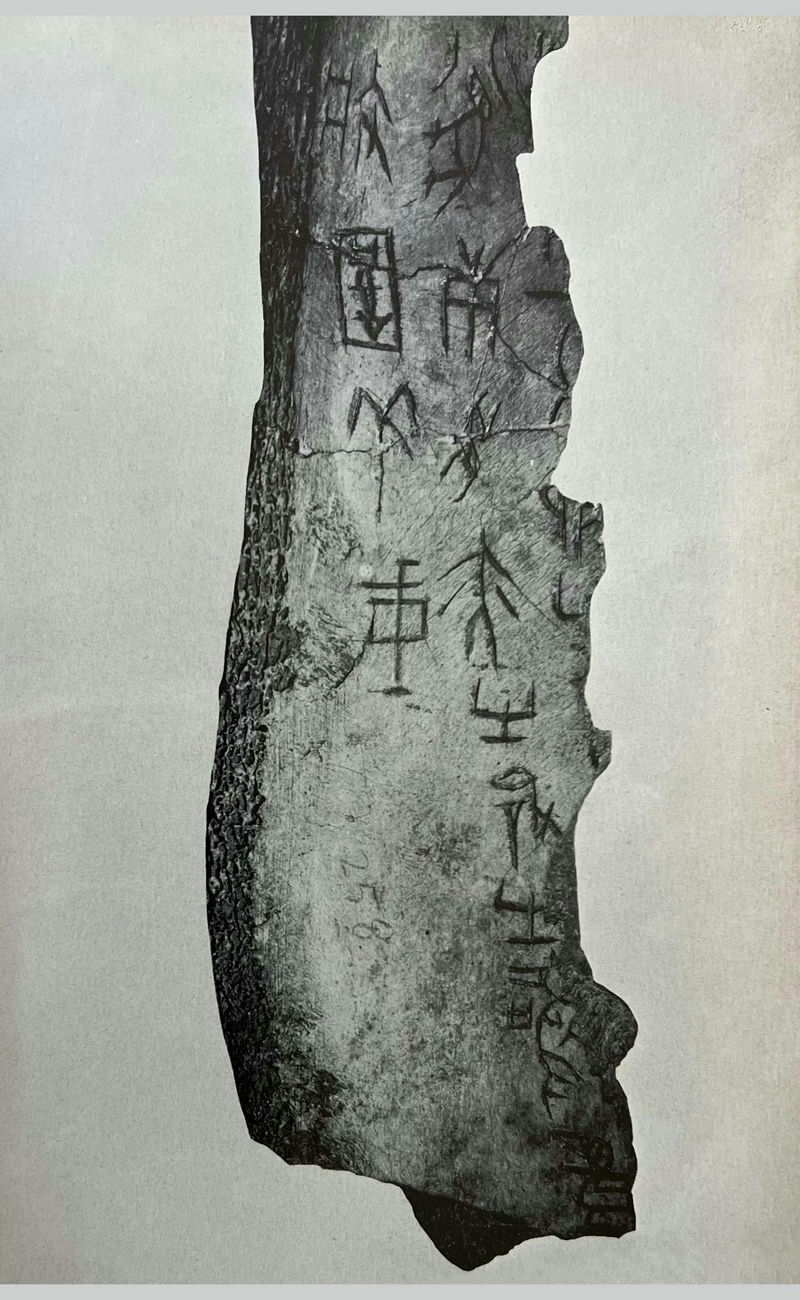

During this period, he also conducted another very meaningful experimental work. He took photo enlargements of those intersections of inscriptions that could be clearly seen under a magnifying glass, to examine the order of the strokes of the inscription. From this kind of examination, he discovered the order of strokes in each inscription-some followed a fixed habit, some varied with the times, some started with vertical strokes, followed by horizontal strokes, while others started with horizontal strokes followed by vertical ones. These changes in habits can help us determine the age of the inscriptions. He also put a lot of effort into dealing with the many fake oracle bone inscriptions on the market. He patiently made friends with an artist in Anyang (安陽) who specialized in carving fake oracle bone inscriptions, which gave him a lot of insight into identifying fake inscriptions. ...

Oracle bone with large characters from the period of Wu-ting (武丁 ?-1192 BC). Photograph courtesy The Complete Works of Tung Tso-pin, published in 1977

Photographic enlargement of the character i (亦) from the oracle bone above. Photograph courtesy The Complete Works of Tung Tso-pin, published in 1977

If the Sino-Japanese War had not occurred, the development of field archaeology may have taken a different direction. The outbreak of war changed the situation, but the foundation of modern archaeology established before the war had already been stabilized.

In the 34th year of the Republic (1945), which was the year when the war was about to end, he personally transcribed and published the Yin Dynasty Calendar of Historical Events (殷曆譜) litho-printed at Li Village (李莊).

The statement of Mr. Meng-chen (孟真, Meng-chen is the courtesy name of Fu Ssu-nien) that ‘Each step forward in the study of oracle bone inscriptions is a step advanced by Yen-t’ang (彥堂,Yen-t’ang is the courtesy name of Tung Tso-pin),’ can be said to represent the general opinion at that time from colleagues in the archaeology team at the Institute of History and Philology of the Academia Sinica.

After the war, most of his energy was focused on advancing the study of calendrical systems and compiling a comprehensive Chinese almanac. This development of his central interest can be traced back to his work of textual research and interpretation of ancient texts on the Four Large Plates of Tortoiseshell (大龜四版, excavated at the Yin Dynasty Ruins in 1929).

However, Mr. Tung’s academic contributions after the war could have been several times greater, according to his standards before and during the war. But his work environment had changed, including both the intellectual and material aspects. ... After arrival in Taiwan, the educational and academic communities were all part of the refugee class, with a deep sense of uncertainty and insecurity about the future. Most of those from the Academia Sinica were taken in by the National Taiwan University. As it is an educational institution, receiving a salary there required teaching a certain number of courses and naturally the time left for research was cut to the minimum. During this period, Mr. Tung’s energy was largely spent on having to maintain a bare minimal standard of living. His founding of Ta-lu Magazine (Continental Magazine 大陸雜誌), employment at the University of Hong Kong, and his teaching in Taiwan were not truly the work that he wanted to do.

Mr. Tung Yen-t’ang was fifty-five years old when he came to Taiwan. Although he wrote several popular articles to promote his past academic achievements and completed The Comprehensive Chinese Calendar of Historical Events (中國年曆總譜) at the University of Hong Kong, strictly speaking, none of these were the best work that he was capable of. Based on his academic background and talent, he could have built a more solid foundation for the study of Chinese etymology. He had the aspiration to do so, but the environment prevented him from achieving this aspiration and forced him to waste his energy on many unrelated areas. This was his loss, his friends’ loss, China’s loss, and even the loss of the worldwide academic community.

I am not able to speak any further as I think of this.”

After mainland China fell to the communists, Chinese culture scattered across the seas, and scholarly aspirations were thwarted. Li Chi’s words were almost choked with sobs.

Portrait of Tung Tso-pin. Photograph courtesy The Complete Works of Tung Tso-pin, published in 1977

Tung Tso-pin was born on 24 February (Chinese calendar) in the 21st year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1895). He passed away on 23 November in the 52nd year of the Republic (1963). Originally named Tso-jen (作仁), tzu Yen-t’ang (彥堂), studio name P’ing Lu (平廬). He was a native of Nan-yang, Honan Province. At the age of six, he became a student of Ch’en Wen-tou (陳文斗) who gave him the name Tso-pin (作賓). At the age of fourteen, he began selling his own works of calligraphy couplets and engraved seals.

In the 5th year of the Republic (1916), he graduated from the County Teacher-Training Center and in the 7th year of the Republic (1918), he entered the Honan Scholar-Training Academy. In the 11th year of the Republic (1922), he entered Peking University as a non-degree student. In the 16th year of the Republic (1927), he was appointed associate professor at National Sun Yat-sen University, in the following year, he became an editor at the Institute of History and Philology of the Academia Sinica established by Fu Ssu-nien. In the same year he supervised the 1st excavation of the Yin Dynasty Ruins, then he was in charge of the 5th excavation of the Yin Dynasty Ruins in the 20th year of the Republic (1931), the 7th excavation in the 21st year of the Republic (1932), and the 9th excavation in the 23rd year of the Republic (1934). In the 36th year of the Republic (1947), he became a visiting professor of Chinese archaeology at the University of Chicago. In the following year, he was appointed an academician of the first session of the Academia Sinica. In the 38th year of the Republic (1949) after mainland China fell to communist rule, he moved to Taiwan with the government and became a professor at the Faculty of Arts in the National Taiwan University. In the following year, he founded Ta-lu Magazine (Continental Magazine). In the 40th year of the Republic (1951), he became the director of the Institute of History and Philology at the Academia Sinica, and in the 44th year of the Republic (1955), he became a research fellow at the Institute of Oriental Studies at the University of Hong Kong. In the 47th year of the Republic (1958), he became the head of the Oracle Bone Inscription Research Room (甲骨學研究室) at the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica. His works include Studies on the Dating of Oracle Bone Inscriptions (甲骨文斷代研究例), Yin Dynasty Calendar of Historical Events (殷曆譜), First Compilation of Inscriptions from Yin Dynasty Ruins (殷墟文字甲編), Second Compilation of Inscriptions from Yin Dynasty Ruins (殷墟文字乙編) in three volumes, Fifty Years of Oracle Bone Studies (甲骨學五十年) and The Comprehensive Chinese Calendar of Historical Events (中國年曆總譜).

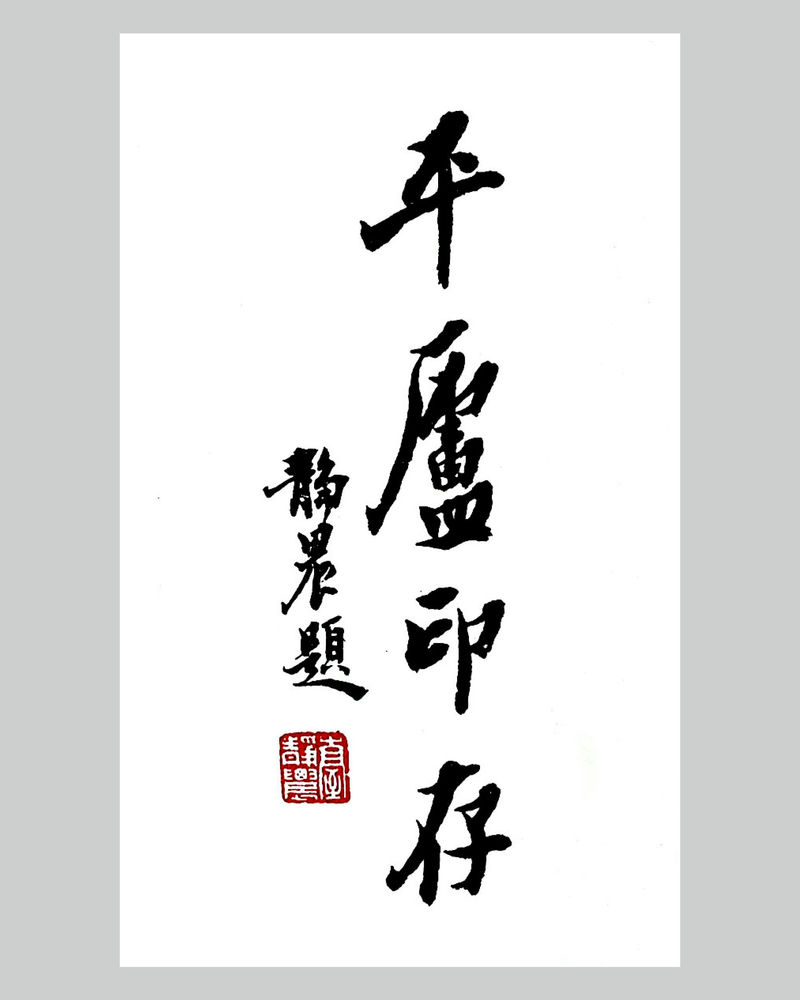

Calligraphy of the book title P’ing Lu yin-ts’un by Tai Ching-nung. Photograph courtesy The Complete Works of Tung Tso-pin, published in 1977

At the age of fourteen in the 34th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1908), Tung Tso-pin helped his father in business by charging for his own seal carvings in the market. Later, he only occasionally practiced seal carving and few were made. His seal impressions were compiled in P’ing Lu yin-ts’un (平廬印存), which recorded eighty five seals engraved between the 26th year of the Republic (1937) to the 43rd year of the Republic (1954), including fourteen seals for personal use, four seals given to his wife Hsiung Hai-p’ing (熊海平), one seal given to his son Tung Min (董敏), and the rest engraved as gifts for friends. The preface of P’ing Lu yin-ts’un states that the impressions of seals engraved between the 23rd year of the Republic (1934) and the 25th year of the Republic (1936), were compiled in Hsi-hsiang yin-p’u (西廂印譜). Unfortunately, this volume has been lost. The seal impressions in P’ing Lu yin-ts’un are not accompanied by any ink rubbings of their side inscriptions. There are many handwritten notes printed below the seal impressions. From this we know that Tung Tso-pin did not engrave any inscription or name on the sides of the seals. Hence the seals are dispersed without trace and rarely preserved.

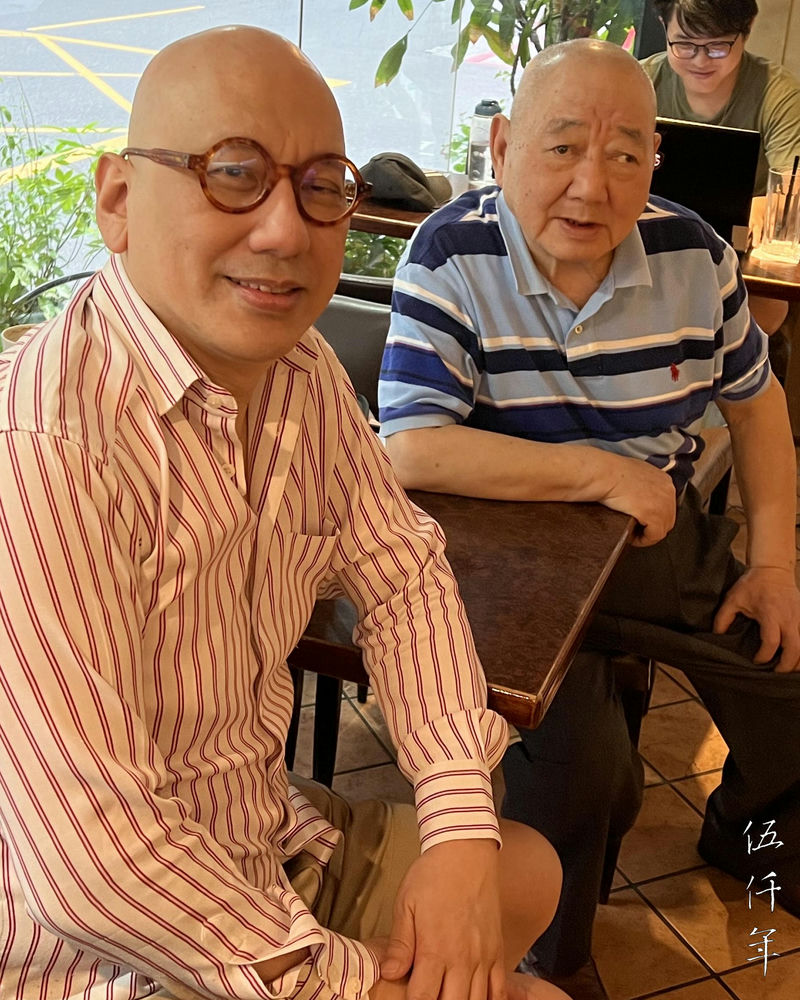

Photograph of Mr. Tang Hung-chien (right) and the author (left) taken in Taipei

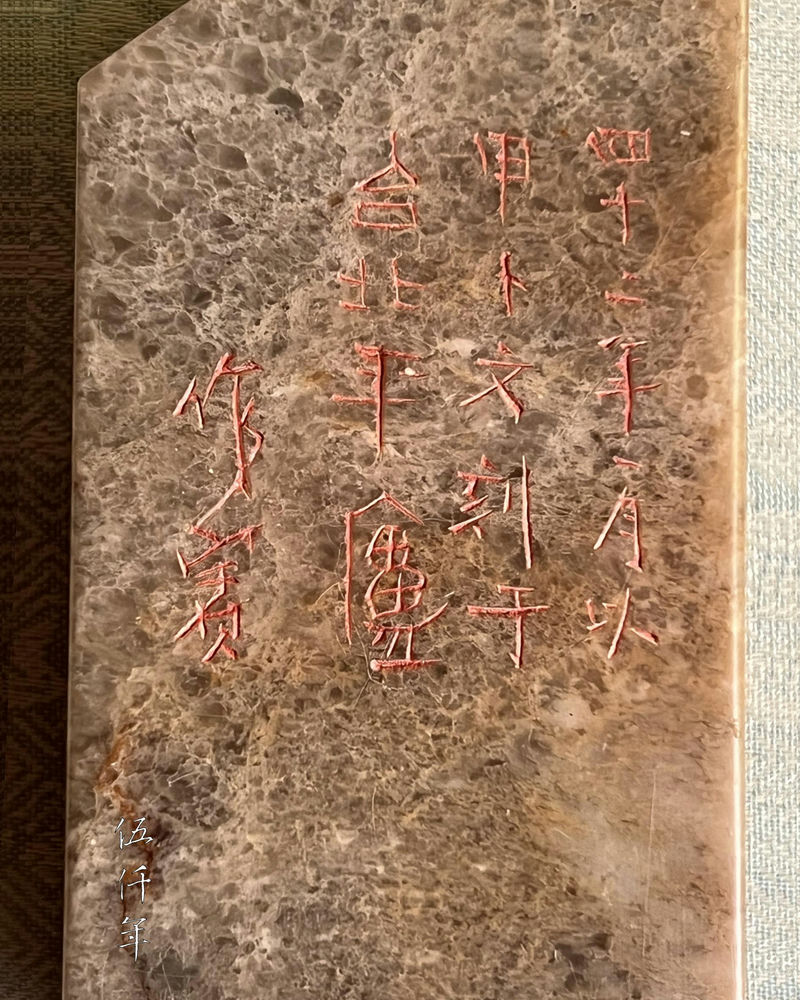

Side inscription of the oracle bone script seal by Tung Tso-pin

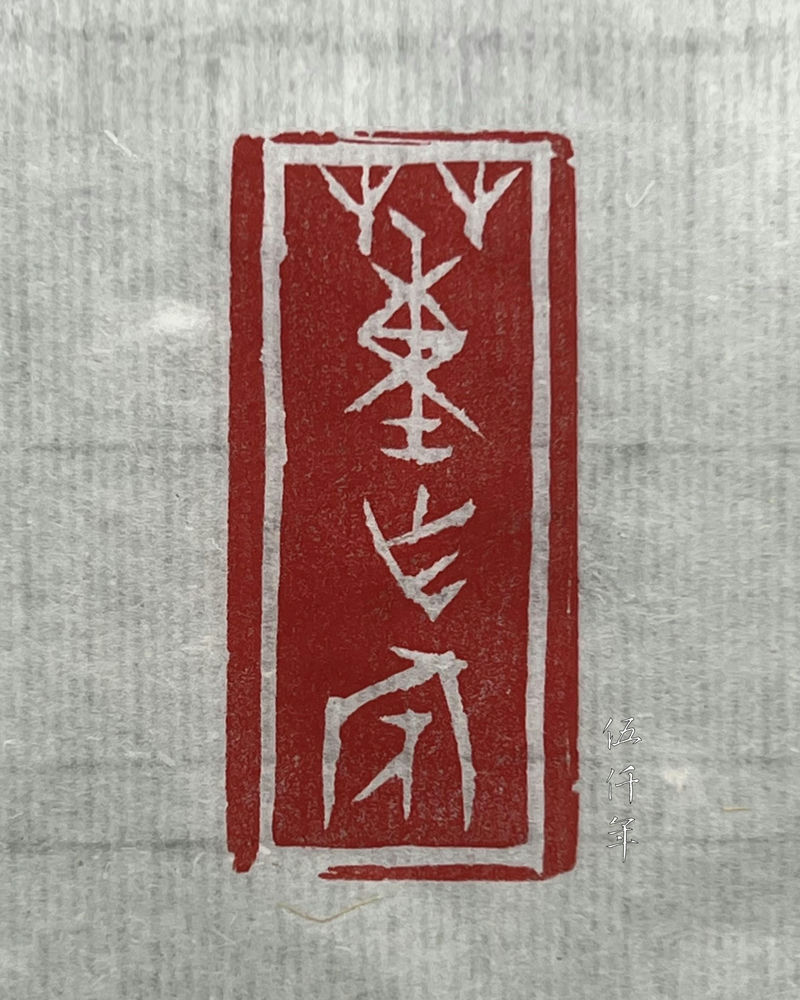

Seal face of the oracle bone script seal engraved with the words Tung Tso-pin

I have particularly cherished a seal carved by Tung Tso-pin. It was generously gifted to me by Mr. Tang Hung-chien (唐鴻漸先生). His great kindness and deep friendship is forever engraved in my heart. This seal is not only unrecorded in P’ing Lu yin-ts’un, it is also the only known seal Tung Tso-pin engraved with signature and inscription.

Seal impression and side inscription ink rubbing of the oracle bone script seal by Tung Tso-pin

Seal impression of the oracle bone script seal by Tung Tso-pin

The seal reads:

"Tung Tso-pin"

Detail of the side inscription of the oracle bone script seal by Tung Tso-pin

Side inscription ink rubbing of the oracle bone script seal by Tung Tso-pin

The side inscription reads:

"In the first month of the 42nd year [of the Republic of China] (1953)

carved in oracle bone script at P’ing Lu, Taipei.

Tso-pin."

The first seal impression of Fang Kuei in P’ing Lu yin-ts’un

This seal was carved in January of the 42nd year of the Republic (1953), when Tung Tso-pin was serving as the director of the Institute of History and Philology at the Academia Sinica. The earliest seal he carved in oracle bone script is the seal with the characters Fang Kuei (方桂), which is the first seal impression seen in P’ing Lu yin-ts’un. It was dated 26th year of the Republic (1937). The notes under the seal impression reads:

“In the 26th year [of the Republic of China] (1937), on the 9th anniversary of the Academia Sinica, I carved four small seals for Fang Gui and his wife. I used various characters in the oracle bone script, this is one of them.”

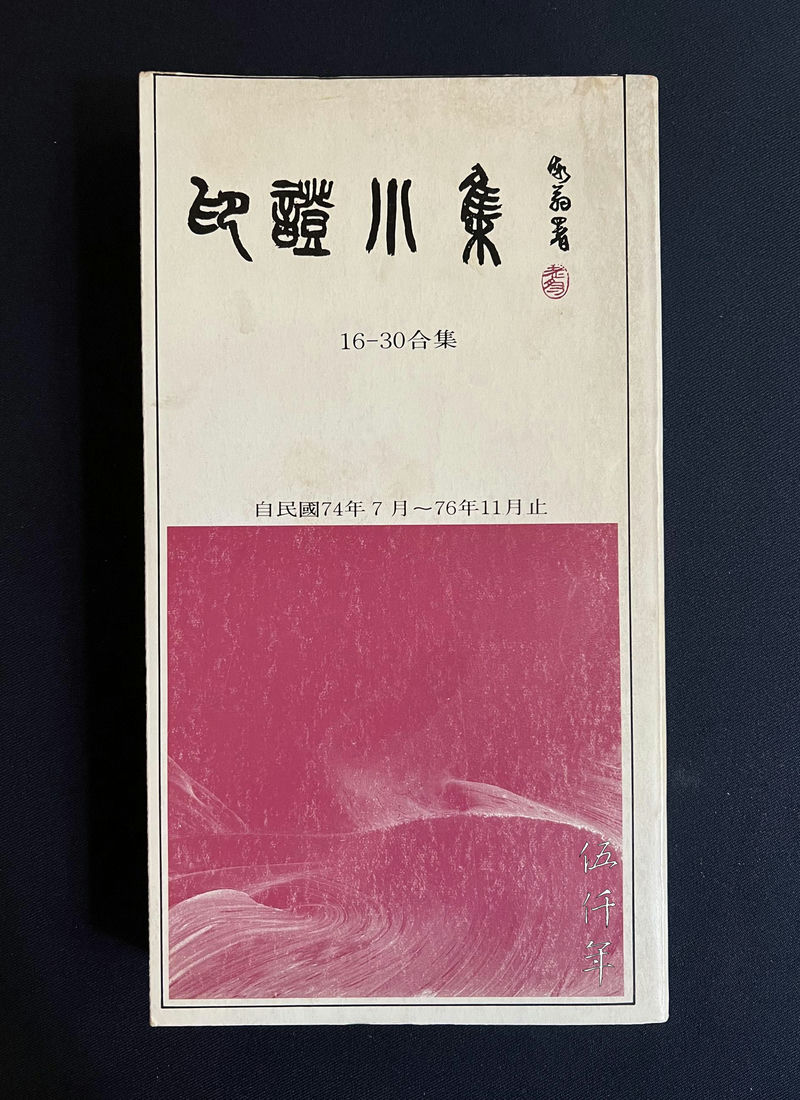

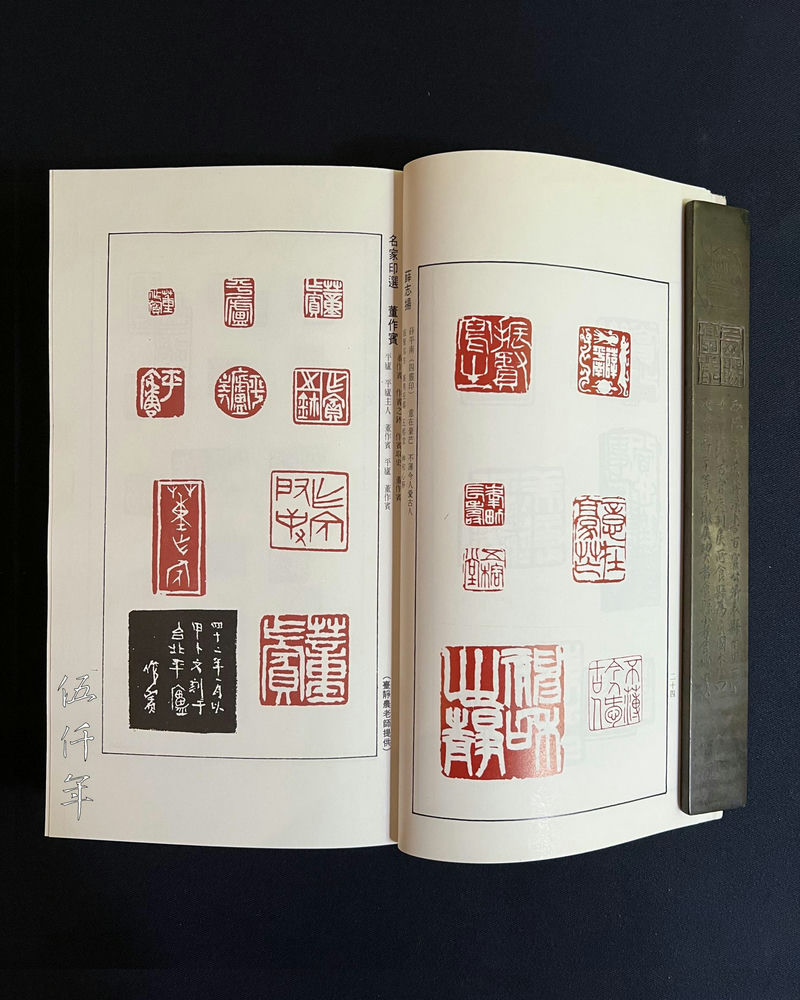

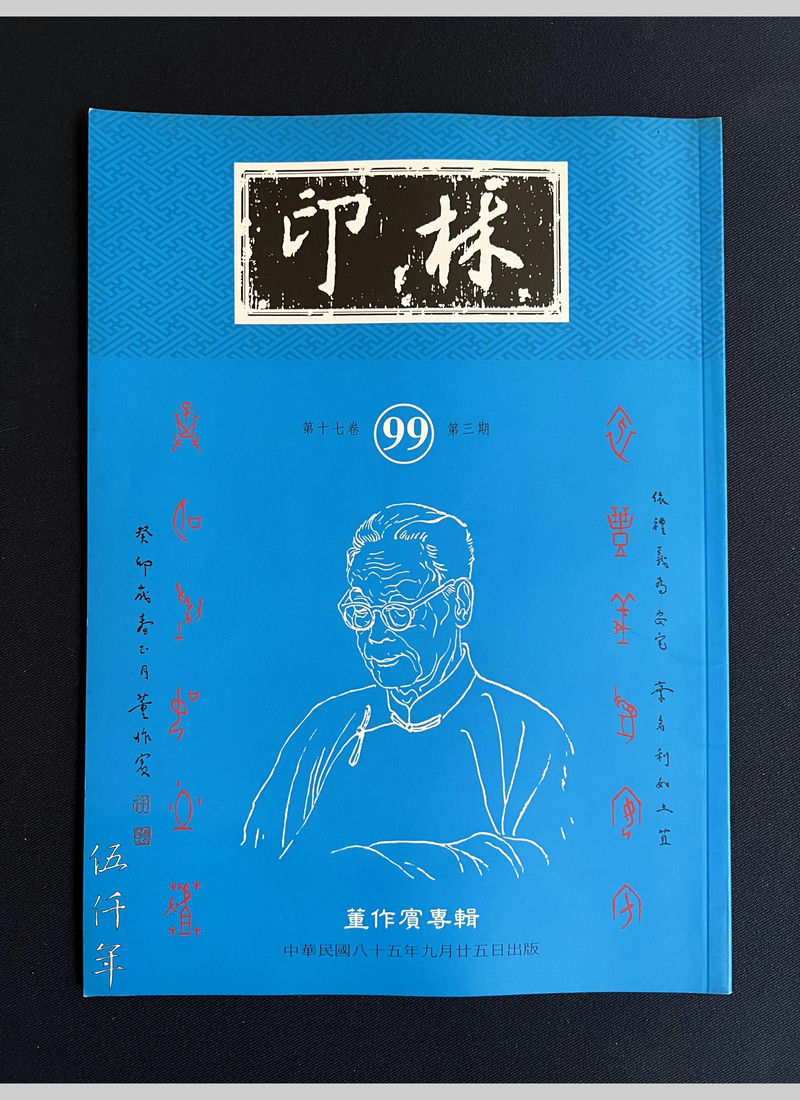

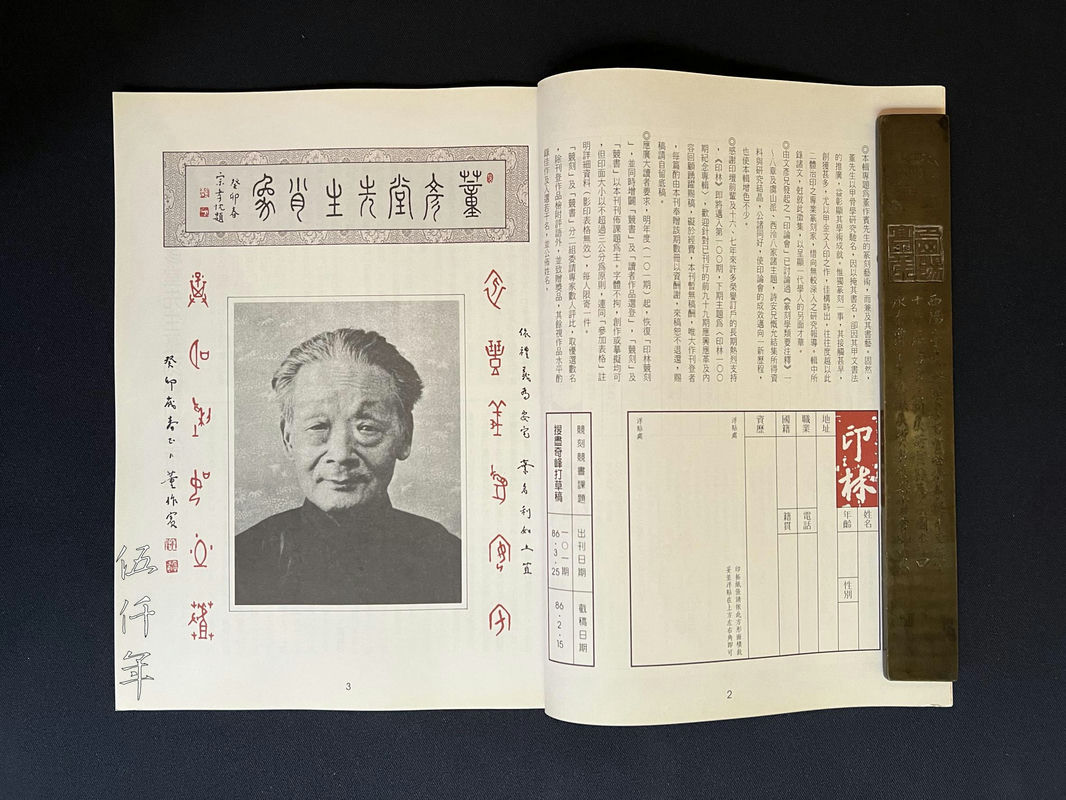

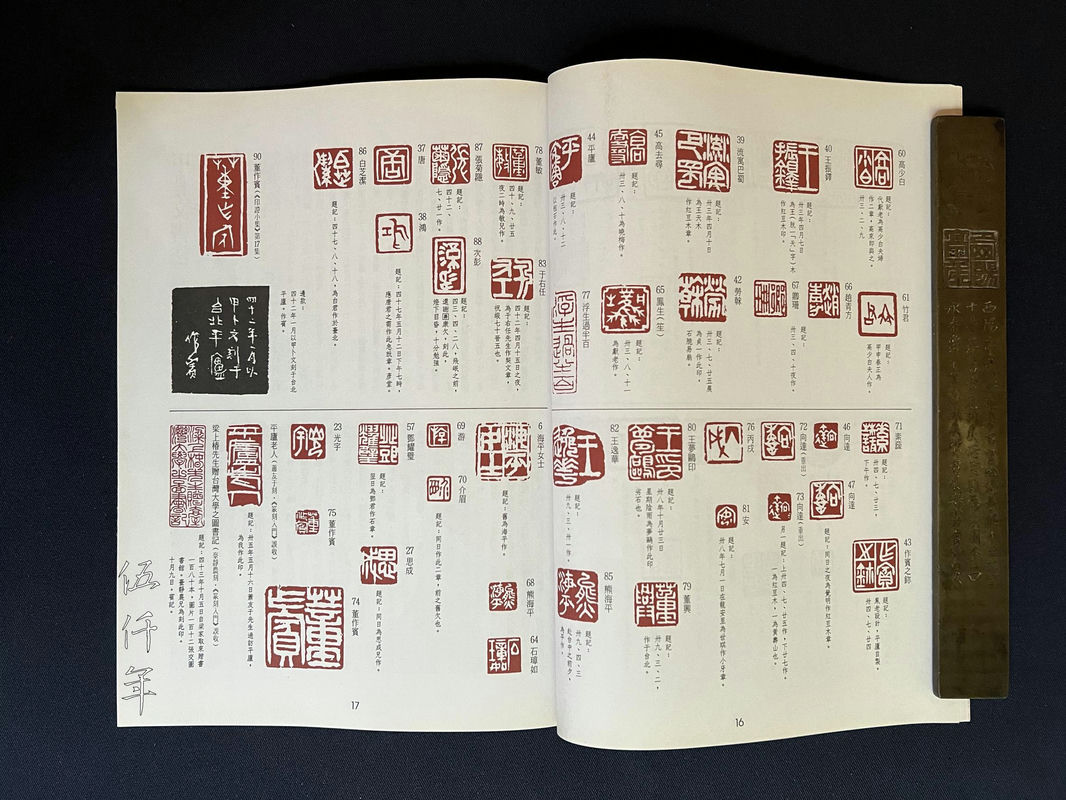

This oracle bone script seal carved by Tung Tso-pin has been published in the 17th Volume of Yin-cheng hsiao-chi Magazine (印證小集), issued in September of the 74th year of the Republic (1985). It is illustrated in the article A Compilation of Seals by Tung Tso-pin (董作賓印集), the seal impressions were provided by T’ai Ching-nung (臺靜農). This oracle bone script seal has also been published in Volume 17, Issue 3, Special Issue on Tung Tso-pin (董作賓專輯) of Yin-lin Magazine (印林), issued in September of the 85th year of the Republic (1996).

Front cover of the bound volume of Yin-cheng hsiao-chi Magazine between July 1985 to November 1987

The oracle bone script seal was published in the Tung Tso-pin Special Feature in the September 1985 issue of Yin-cheng hsiao-chi Magazine

Front cover of the September 1996 issue of Yin-lin Magazine

Inside page of the September 1996 issue of Yin-lin Magazine

The oracle bone script seal was published in the Tung Tso-pin Special Feature in the September 1996 issue of Yin-lin Magazine

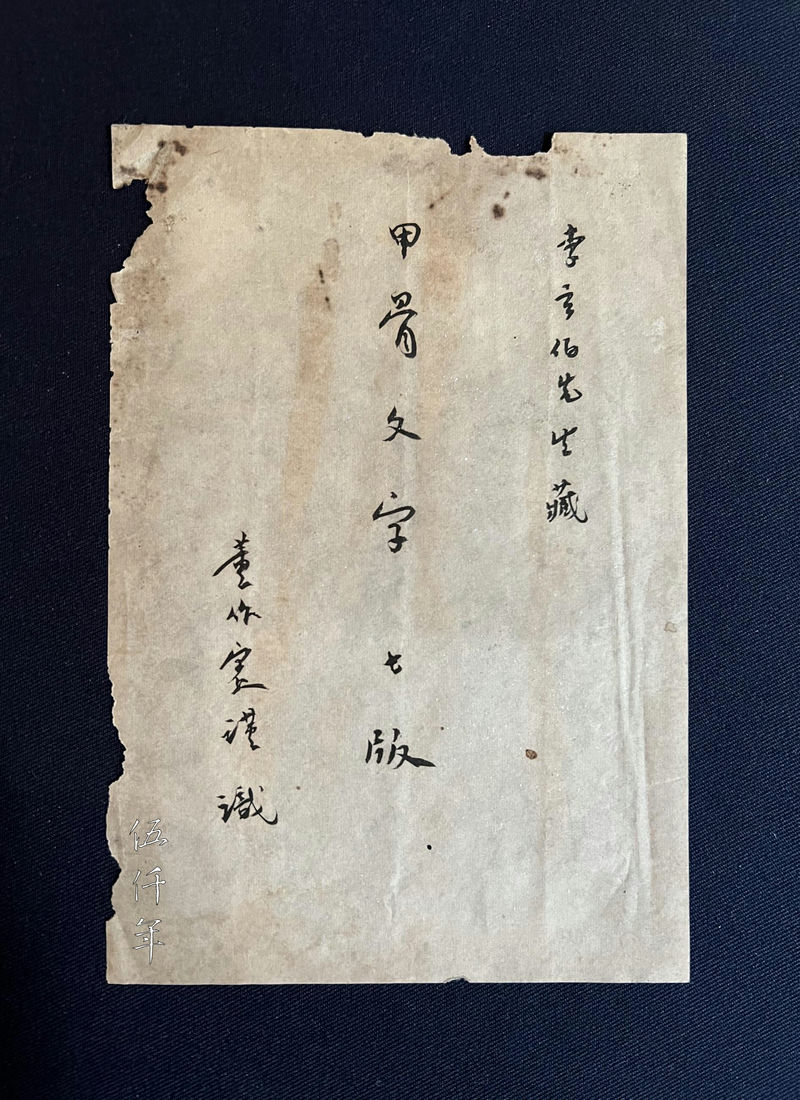

In my collection there is also a piece of calligraphy on a small sheet of paper by Tung Tso-pin to be used for a book title with accompanying envelope. It provides a glimpse of the transplant of oracle bone scholarship to Taiwan.

The calligraphy on the small sheet of paper reads:

“Epigraphs on Oracle Bones

In the Collection of Mr. Li Hsüan-po (李玄伯先生)

Seventh Edition

Respectfully inscribed by Tung Tso-pin”

Book title written by Tung Tso-pin

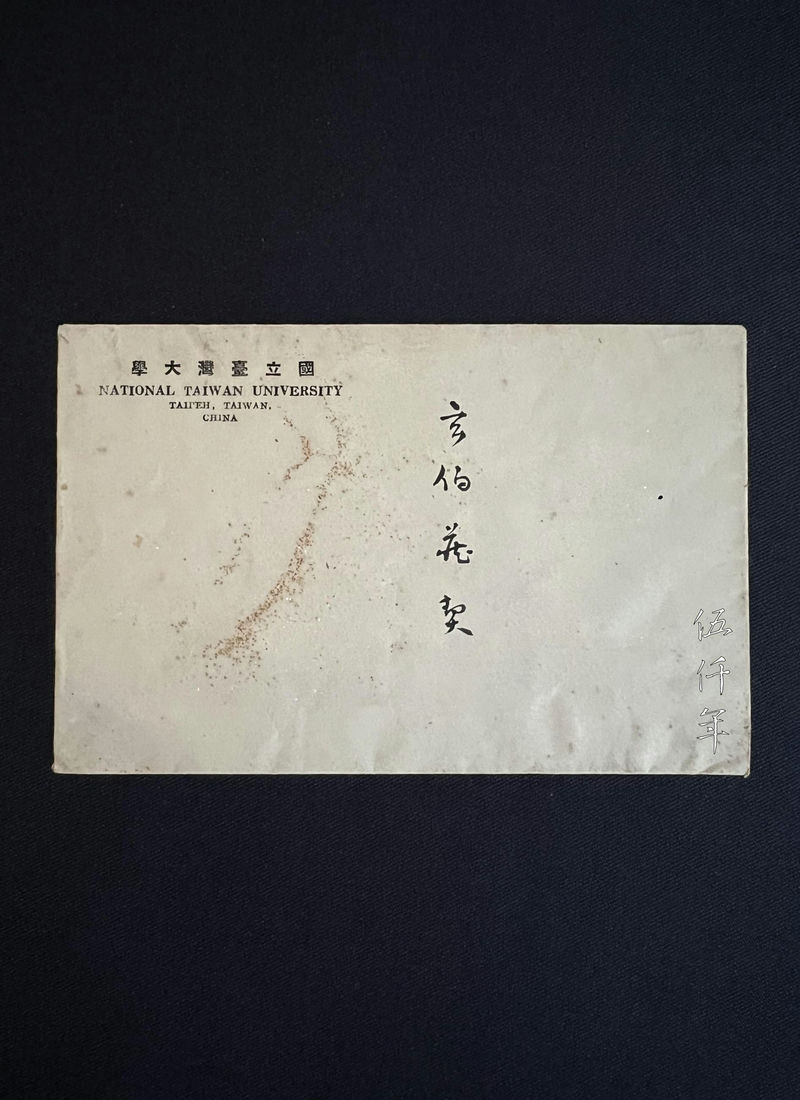

Calligraphy on the envelope reads:

“Epigraphs Collected by Hsüan-po”

Calligraphy on envelope by Tung Tso-pin

In the upper left corner of the envelope are the printed words: National Taiwan University, indicating that it was written in the 38th year of the Republic (1949) when Tung Tso-pin first arrived in Taiwan to teach at the Faculty of Arts at the National Taiwan University.

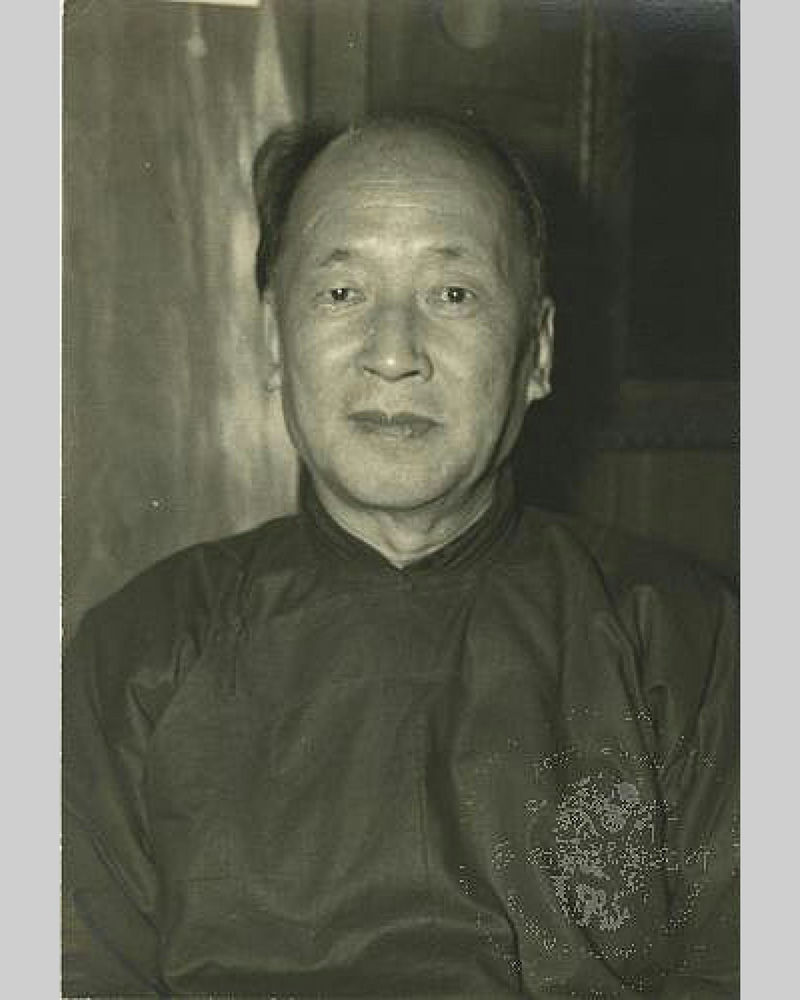

Portrait of Li Hsüan-po

Li Hsüan-po (李玄伯 1895-1974), original name Tsung-tung (宗侗), was a native of Kao-yang, Hopeh Province. His grandfather, Li Hung-tsao (李鴻藻), served successively as minister of the Five Ministries, his father, Li K’un-ying (李焜瀛), was assistant minister of the Ministry of Revenue, and his uncle, Li Shih-tseng (李石曾), was a pioneer revolutionary. Li Hsüan-po had been to France with his uncle and graduated from the University of Paris. In the 13th year of the Republic (1924), he taught at the National Peking University. He later served successively as the director of the National Registration Bureau of the Ministry of Finance, the supervisor of the Kailuan Mining Administration, the secretary-general of the National Palace Museum, and member of the Peking Branch of the Central Political Council. In the 38th year of the Republic (1949), after mainland China fell to the communists, he followed the government to Taiwan and became a professor of history at the National Taiwan University. He wrote New Studies on Ancient Chinese Society (中國古代社會新研), The Historiography of Chinese History (中國史學史), Profiles of History (歷史的剖面), and other works. The inscription by Tung Tso-pin for a forthcoming book by Li Hsüan-po was written at a time when they were both teaching at the National Taiwan University.

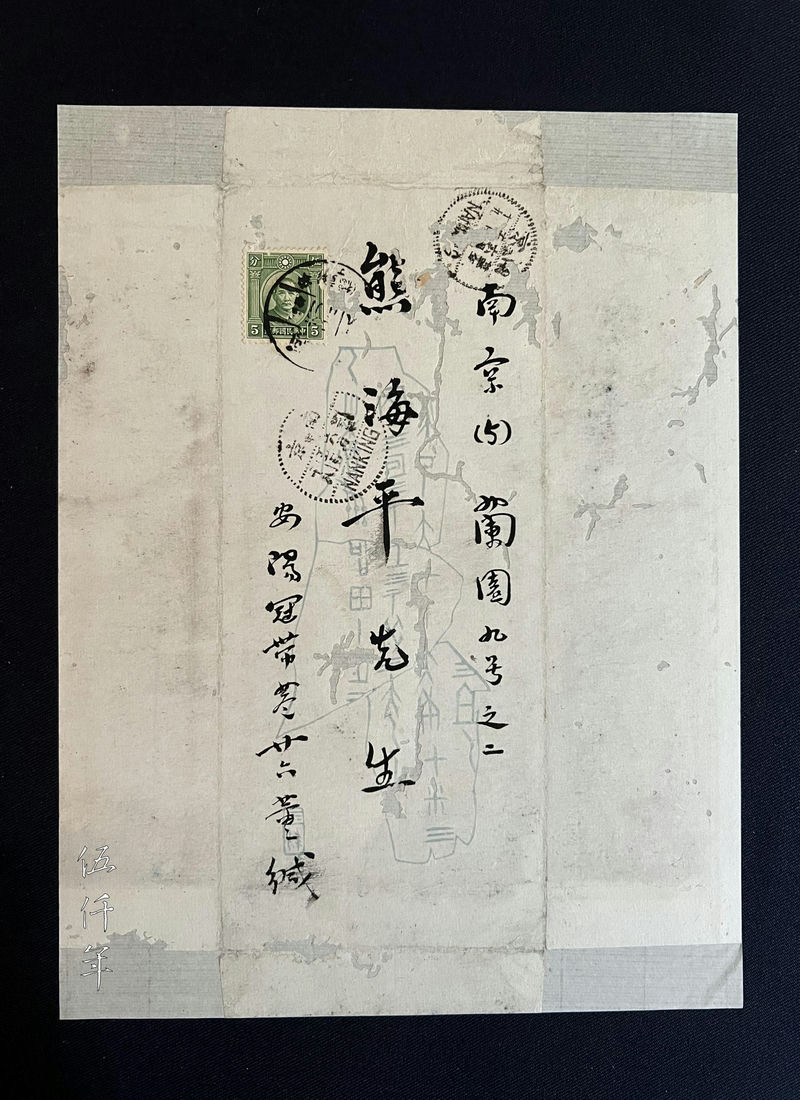

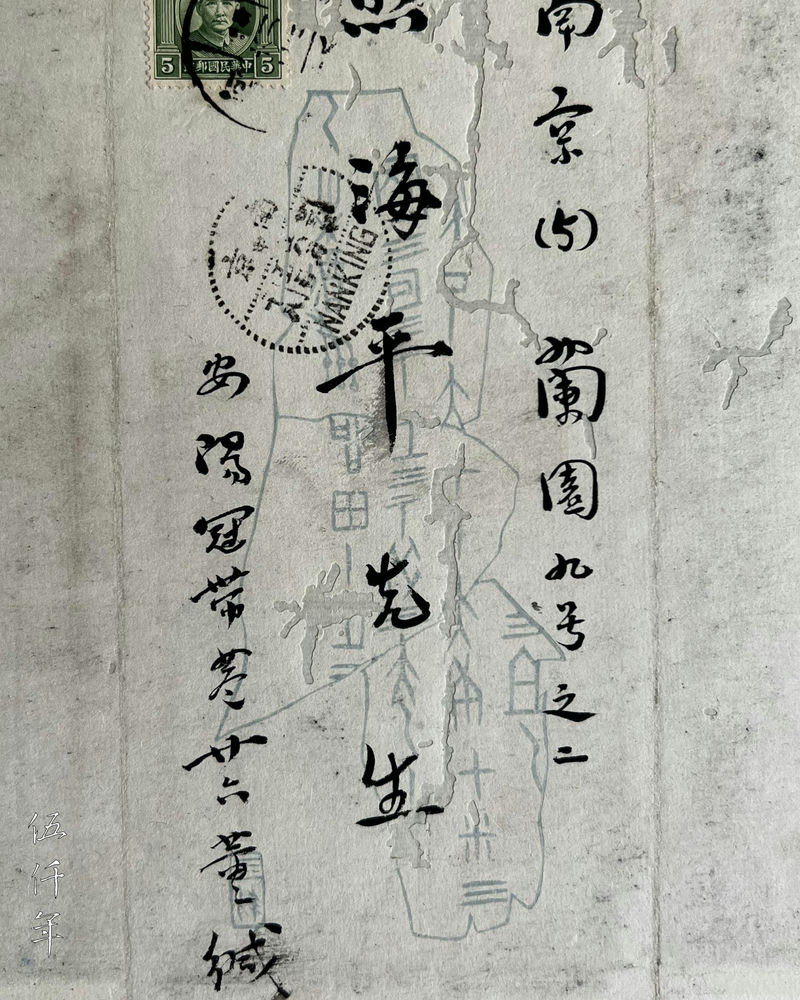

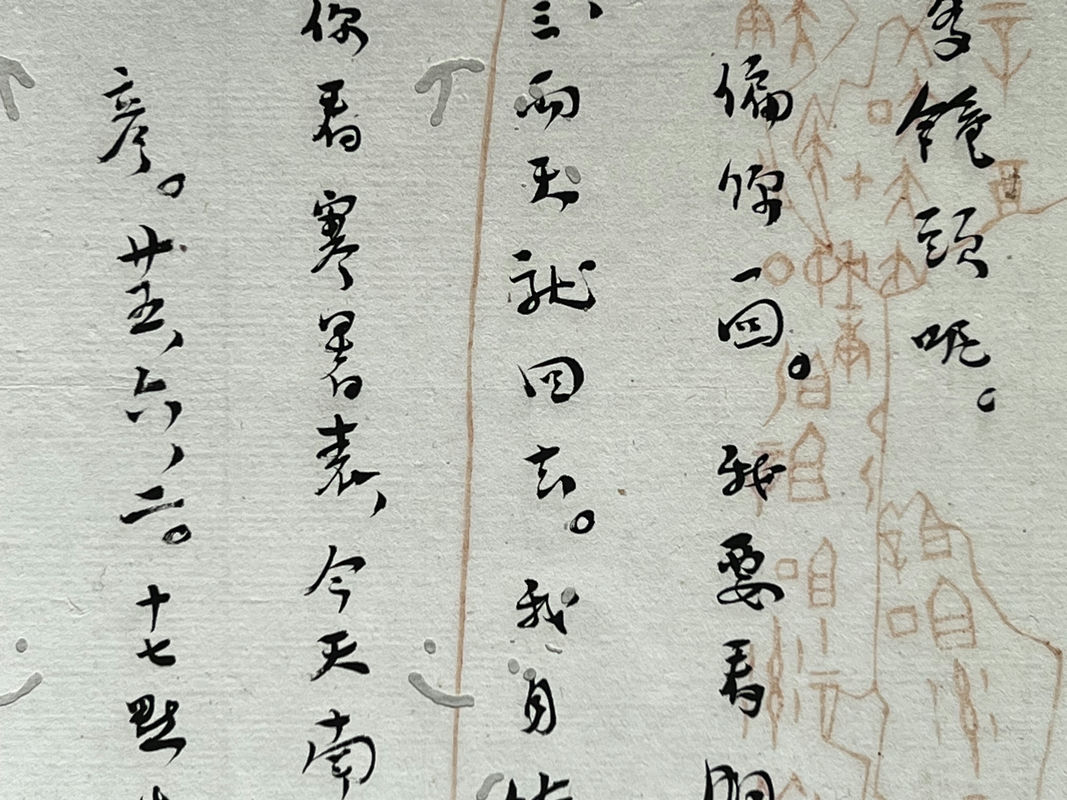

When Tung Tso-pin was twelve in the 32nd year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1906), his mother fell seriously ill, and he obeyed his father’s orders to marry a girl with the surname Ch’ien (錢氏) for the purpose of bringing good luck. In December of the 23rd year of the Republic (1934), at the age of 40, Tung Tso-pin divorced her, and in the following winter, he married his student Hsiung Hai-p’ing (熊海平) in Nanking. I have in my collection a letter written by Tung Tso-pin to his second wife Hsiung Hai-p’ing dated 2 June of the 25th year of the Republic (1936), when they had been married for six months. Tung Tso-pin went to the Yin Dynasty Ruins in Anyang to work on the excavation, while his wife stayed in Nanking, so the letter talked mostly about the excavation work, but it also revealed his yearning and deep affection between the lines.

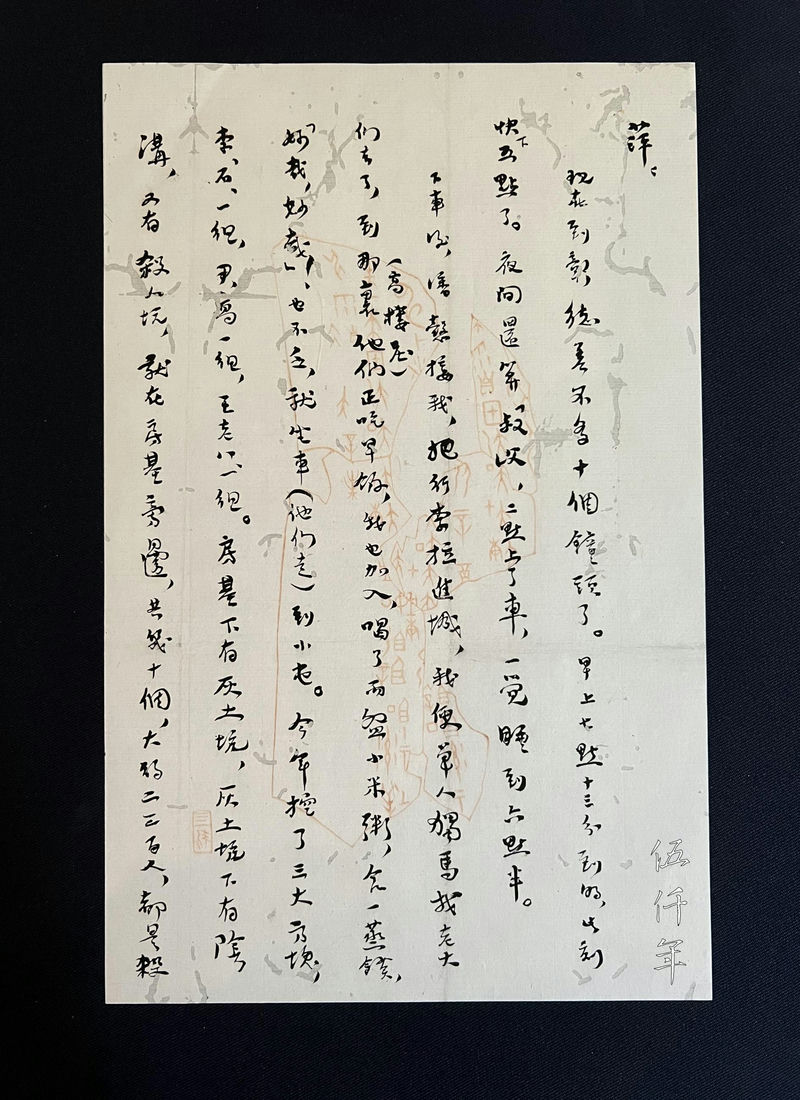

First page of letter by Tung Tso-pin to wife Hsiung Hai-p’ing

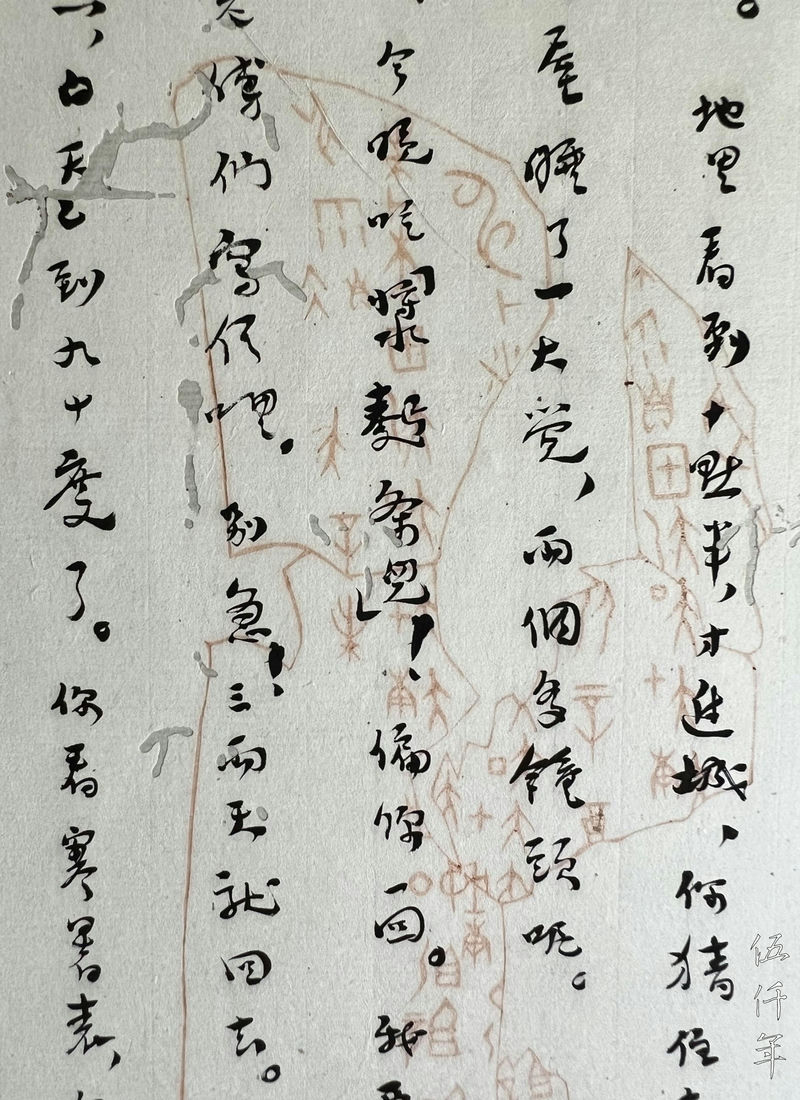

Second page of letter by Tung Tso-pin to wife Hsiung Hai-p’ing

Image of oracle bone printed on letter sheet

Envelope of letter inscribed by Tung Tso-pin

Image of oracle bone printed on envelope

The letter reads:

“Ping-ping:

It has been almost ten hours since I arrived in Chang-te. I arrived at 7:13 in the morning, and now it's almost 5 o’clock. Last night was almost comfortable, from boarding at 2 o’clock, I sept till 6:30 in the morning.

After getting off the train, Pan Ch’üeh (潘愨) came to pick me up and helped bring my luggage into the city. Then I went alone to find the supervisors. When I arrived (at Kao-lou Chuang高樓庄), they were having breakfast. I joined them and had two bowls of millet porridge and a steamed bun. Delicious! Delicious! I was not tired. I took a car (they walked) to Hsiao-t’un (小屯). This year three large blocks were dug up: Li (李) and Shi (石) in one team, Yin (尹) and Kao (高) on another, and Wang Lao-pa (王老八) in one team.”

The ground before the 13th excavation of the Yin Dynasty Ruins in March 1936. Photograph courtesy Academia Sinica

Group portrait of the archaeological team taken before the 13th excavation of the Yin Dynasty Ruins in March 1936. Photograph courtesy Academia Sinica

Note: Tung Tso-pin’s letter: “This year three large blocks were dug up” referred to the 13th excavation of the Yin Dynasty Ruins, which began on 18 March in the 25th year of the Republic (1936) and ended on 24 June in the same year. “Li and Shi team” referred to Li Ching-tan (李景聃 1900-1946) and Shi Chang-ju (石璋如 1902-2004). “Yin and Gao team” referred to Yin Huan-chang (尹煥章 1909-1969) and Kao Ch’ü-hsün (高去尋 1910-1991). “Wang Lao-pa” referred to Wang Hsiang (王湘 1912-2010), nicknamed Lao-pa (老八).

Group portrait of Pan Ch’üeh (first left), Yin Huan-chang (second left), Li Ching-tan (third left), Kuo Pao-chün (third right), Kao Ch’ ü-hsün (second right) and Shi Chang-ju (first right). Photograph courtesy Academia Sinica

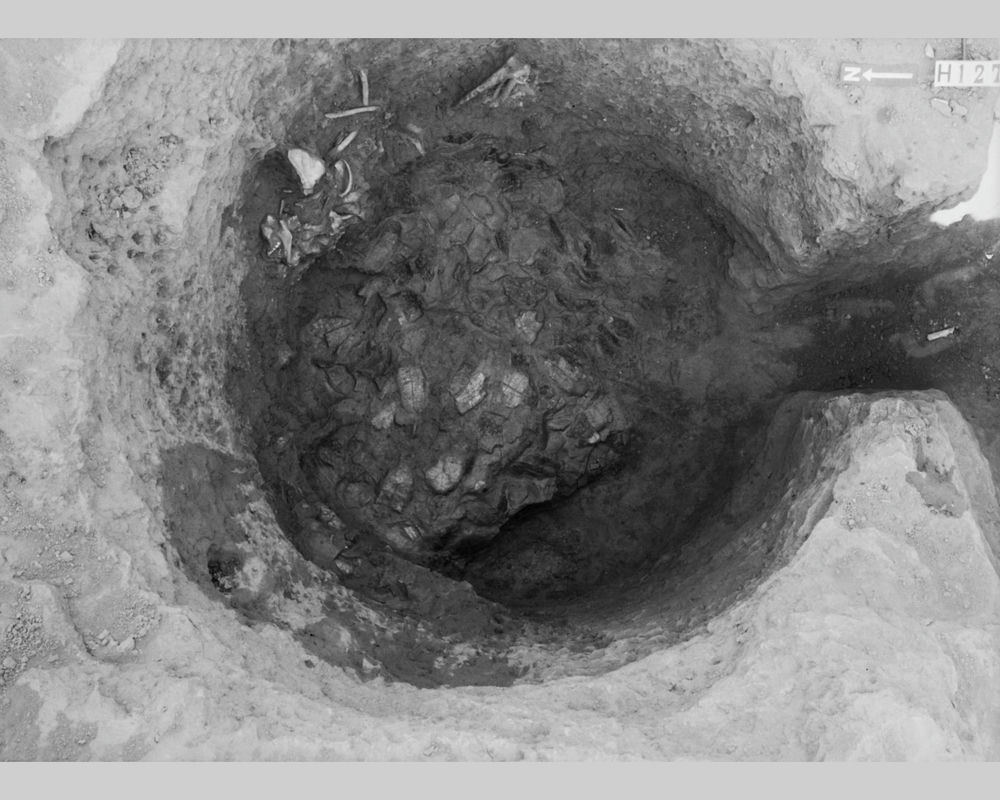

There are pits with grey soil under the house foundation. Under the pits with grey soil are ditches. There are dozens of execution pits right next to the house foundation. There are around two to three hundred victims of decapitation. (Don’t be scared!) The bodies are separated from the heads, but are still together in the same pit, which is quite different from the situation in the Northwest Hill (西北岡). There are also several hundred oracle bones that are not particularly remarkable here. In the future, they will be taken to Nanking together with those from K’ai-feng.

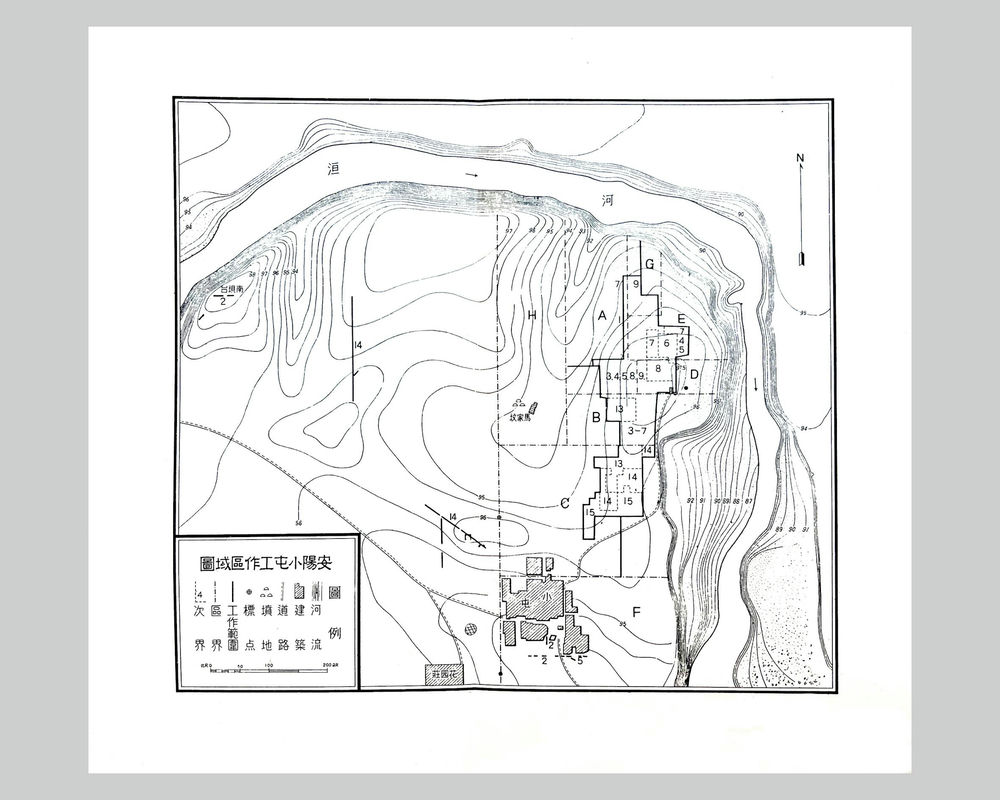

Excavation map of Yin Dynasty Ruins. Photograph courtesy The Complete Works of Tung Tso-pin, published in 1977

Excavation map of Hsiao-t’un Village in Anyang. Photograph courtesy The Complete Works of Tung Tso-ping, published inn1977

The YH127 oracle bone pit during the 13th excavation of the Yin Dynasty Ruins. Photograph courtesy Academia Sinica

Note: The location of the site of the 13th excavation of the Yin Dynasty Ruins was in the B and C areas north of Hsiao-t’un Village (小屯村), with an excavation area of approximately 4,700 square meters and a total area of approximately 10,000 square meters. A pit was excavated every 160 square meters, and total of 52 pits were excavated. Important findings include 127 pits with grey soil, 182 early and late period tombs, 3 intact small rammed-earth walls, wagon pits, headless prone burials, water ditches from the Black Pottery and Gray Pottery eras, an intact tortoiseshell pit with approximately 300 intact tortoiseshell divination pieces and over 10,000 fragmented pieces. The wealth of oracle bones discovered made it into the largest discovery in the years of excavation, and mostly were made on 12 June from the YH127 pit. Hence this later discovery was not mentioned in Tung Tso-pin’s letter of 2 June.

I explored the site until 10:30 before entering the city. Guess where I stayed? Haha, I've already taken a long nap in this house for over two hours.

Young sister, dinner tonight will be Chiang-mien-t’iao-erh (漿麵條兒 noodles mixed with sauce)! Let me tempt you for a while. I’m going to see friends and then tonight I still have to write a letter to Old Fu and others. Don’t be impatient! I'll be back in two or three days. My health is as usual so don't worry. It’s hot here, 90 degrees during the day. Check the thermometer, what’s the temperature in Nanking today?

I will say this in the Peking dialect: How are you? Yen, 25th year, 2 June, 17:15”.

Portrait of Fu Ssu-nien

Portrait of Li Chi

Note: Tung Tso-pin’s letter mentioned: “I still have to write a letter to Old Fu and others”. “Old Fu” likely referred to Fu Ssu-nien who was at the time the director of the Institute of History and Philology at the Academia Sinica. The Institute was responsible for fifteen excavations at the Yin Dynasty Ruins. The "others" may include Li Chi, who in the 18th year of the Republic (1929) became the division head of the Archaeology Division at the Institute of History and Philology of the Academia Sinica and supervised many excavations at the Yin Dynasty Ruins.

Afterwards, Fu Ssu-nien, Li Chi and Tung Tso-pin were all appointed as the first panel of academicians of the Academia Sinica in the 37th year of the Republic (1948). In the 38th year of the Republic (1949), after mainland China fell to communist rule, the central government moved to Taiwan. Starting from the 43rd year of the Republic (1954), the various research institutes of the Academia Sinica gradually re-established in Taiwan. In the 38th year of the Republic (1949), Fu Ssu-nien became the president of National Taiwan University. From the 40th year of the Republic (1950) to the 44th year of the Republic (1955), Tung Tso-pin served as the acting director of the Institute of History and Philology at the Academia Sinica. In the 38th year of the Republic (1949), Li Chi became the first department head of the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology at National Taiwan University, and from the 44th year of the Republic (1955) to the 61st year of the Republic (1972), he served as the director of the Institute of History and Philology at the Academia Sinica. A flood of distinguished scholars came to Taiwan from the mainland at the time.

Tung Tso-pin's letter is only two pages long but is deeply meaningful. The letter discussed the personnel involved with the 13th excavation of the Yin Dynasty Ruins in Anyang, Honan Province. The sender’s address on the envelope reads: “No. 26 Kuan-tai Lane, Anyang (安陽冠帶巷廿六)” , indicating that it was written during the excavation of the Yin Dynasty Ruins, making it exceptionally precious. The Yin Dynasty Ruins is the location of the capital city of Shang dynasty. The excavation of the site marked the beginning of archaeological research in China, and laid the foundation for the study of oracle bone inscriptions. Tung Tso-pin's personal involvement in the excavation turned him into the renowned expert in the field of oracle bone studies. As we examine his oracle bone script seal and read his letter from the Yin Dynasty Ruins, our thoughts are let loose to roam the fathomless past, musing over the rise and fall of dynasties, transient as morning dew.

Second page detail of letter by Tung Tso-pin to wife Hsiung Hai-p’ing