To appreciate calligraphy and painting, a state of inner placidity and spiritual purity is desired. Temporal distance from mundane affairs also helps the realization of their artistic pleasures. To appreciate bamboo carving, the heart and mind should only be more unworldly. Carved bamboo objects are customarily placed on the writing desk, brush pots are large, wrist rests, guards of folding fans and miscellaneous writing accoutrements are smaller. Yet they all require meticulous inspections in order to understand the appearance of their carvings, as well as the expressions of the calligraphic and painterly strokes. By observing their poetic spirits, idle pleasure of carefree imagination can be then attained. The wrist rest titled Spring Scenery in Chiang-nan engraved by Chang Hsi-huang (張希黃) of the Ming dynasty, now in the collection of the Chinese-Heritage Virtual Museum, is a rare artwork. We are delighted to present it for the perusal of kindred spirits.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

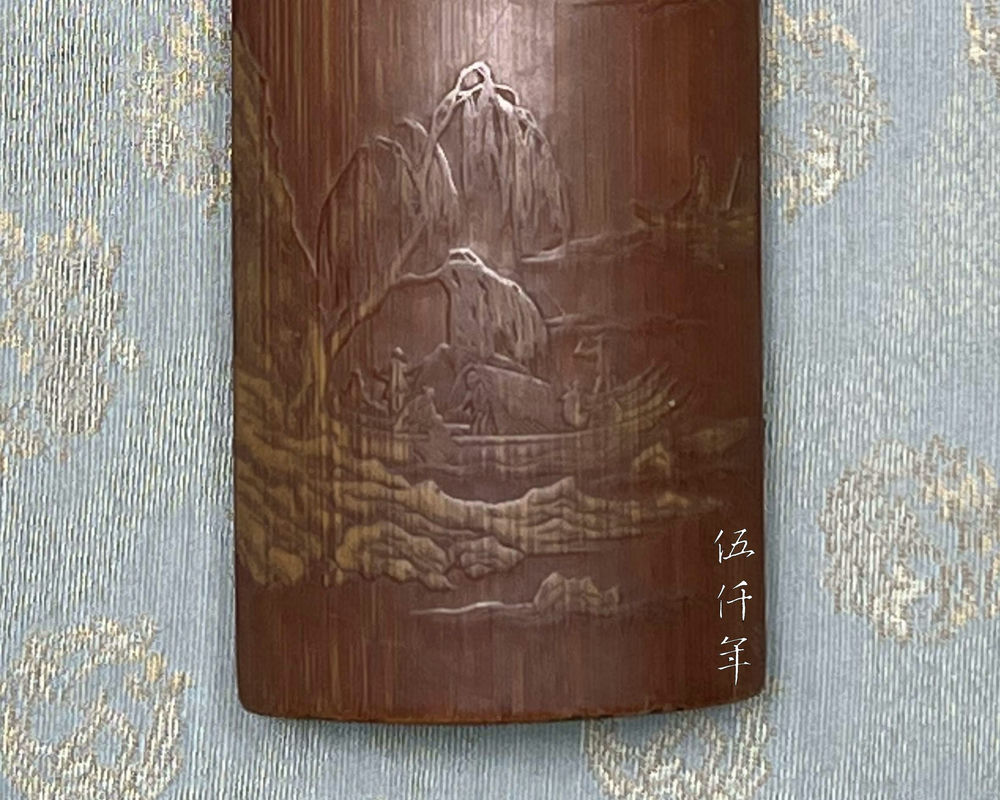

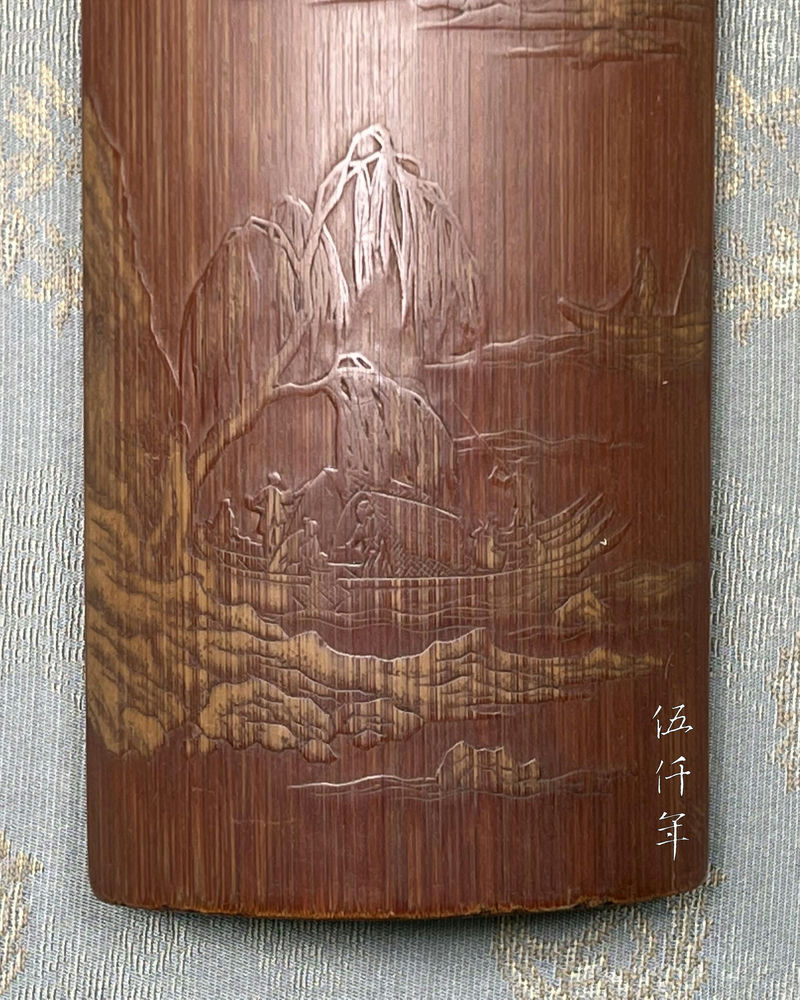

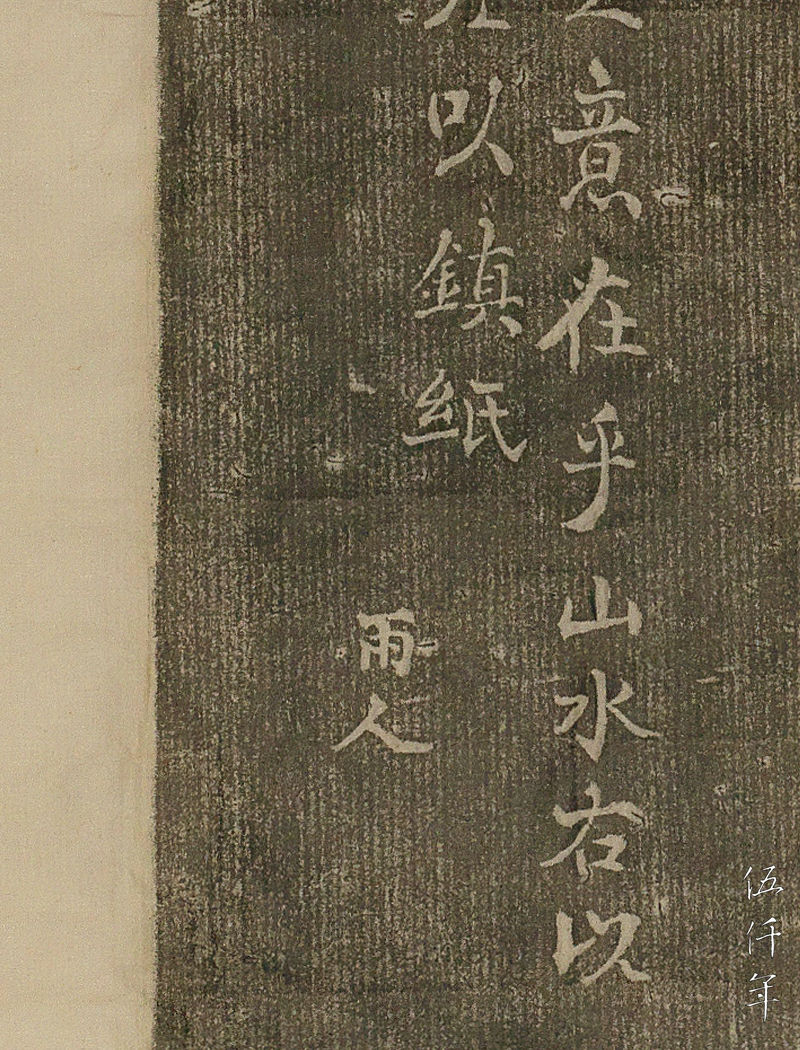

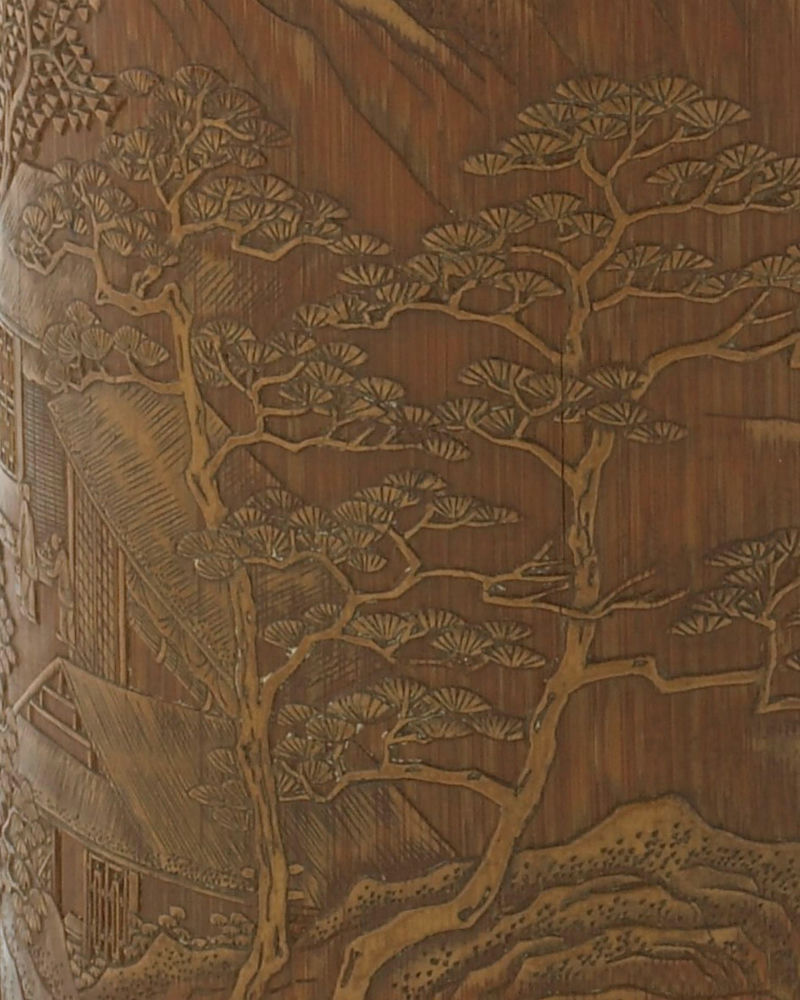

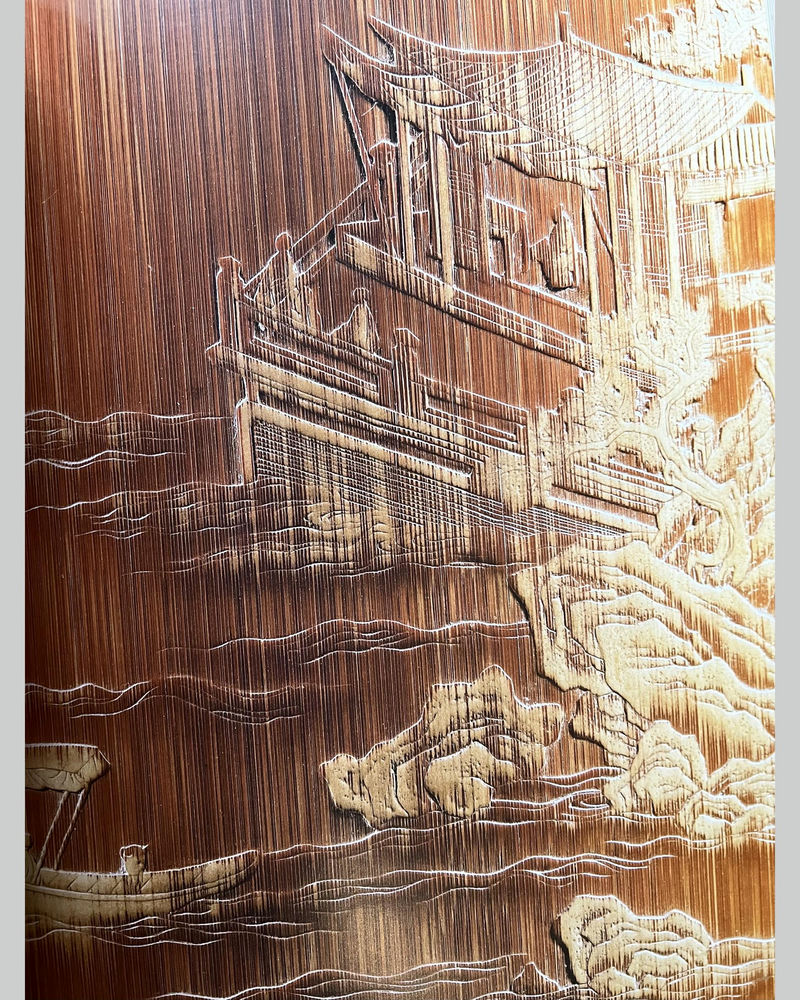

Lower section detail of bamboo wrist rest titled Spring Scenery in Chiang-nan carved by Chang Hsi-huang

Late Ming is now over six sexagenary cycles, a period of more than three hundred and sixty years away. The country has endured the rise and ebb of fortunes as well as countless catastrophes. Much of the splendour of that material world, and the magnificence of its arts, have disappeared. The few pieces that survive the ravages of time are now embraced as the rarest of treasures. It is almost impossible to seek works of art from the late Ming, such as a seal carved by Ho Chen (何震), a teapot made by Shih Ta-pin (時大彬), a piece of bamboo engraved by Chang Hsi-huang (張希黃), in an ephemeral life here today and gone tomorrow, in a life span measured by months and years all too brief. Traces of such works are rarely encountered on these quests. Moreover, forgeries abound, enough to be piled as high as a mountain. Like searching for a pearl in a river of sand, it is dependent on lucky chance and discernment. Any one missing element makes all effort futile. The impediments and difficulties can be imagined.

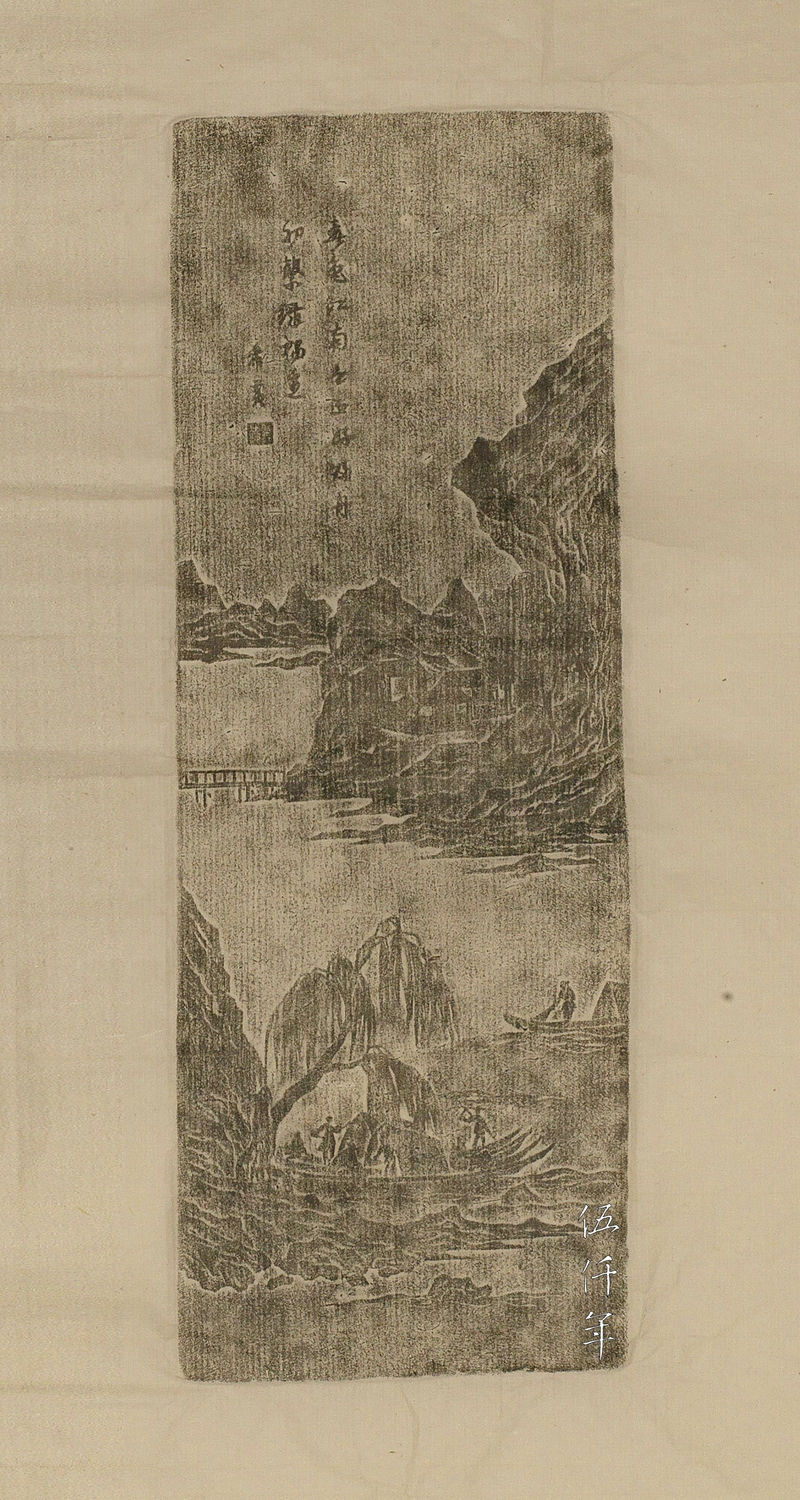

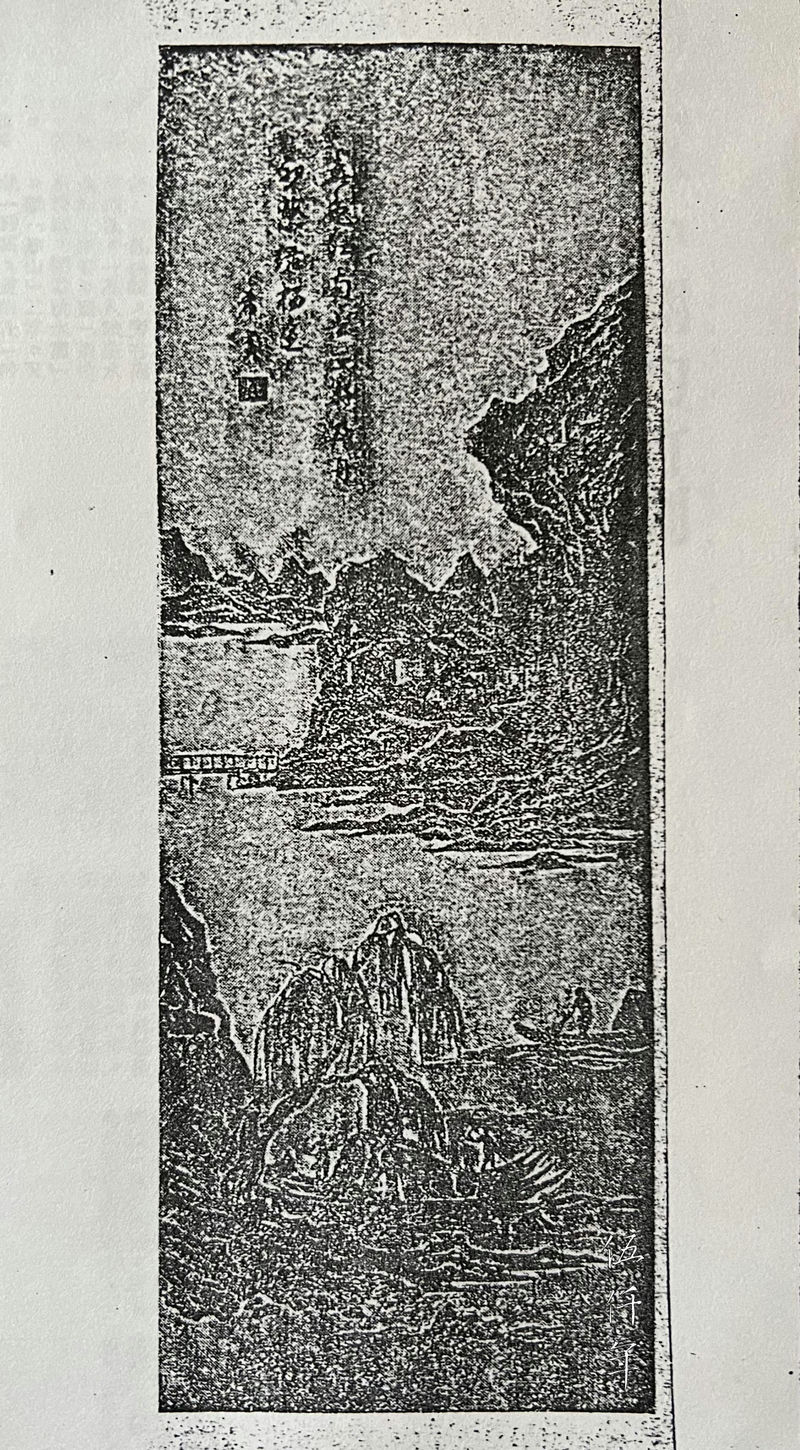

As I greatly enjoy works on bamboo and have taken pleasure in them for many years, I have collected numerous works by eminent bamboo engravers. In the past, several times in the studio of Chin-mei-hua Shih (金梅花室) in Shanghai that belonged to my late friend Mr. Kuo Jo-yü (郭若愚先生), I had examined and admired a bamboo wrist rest engraved by Chang Hsi-huang. The green culm sheath of the bamboo was lightly engraved, the image visually floating on the surface. The carvings are smooth and rounded at the edges, there is no overt mark from the carving knife. It is deceptively like a painting. The engravings of mountain ranges, rhythmic waves, distant village, human figures, rowing boats, draping willows, are so fine in detail as to reveal the cleavages of stone and the ripples of water, so vigorous as to catch a glimpse of the boats almost rolling. There are three rustic dwellings, the windows and doors are well organized, there is a beam bridge, the balustrades and piers are orderly. There are six human figures, one is preparing tea, one is gazing afar, two are inspecting the fishnet, one is rowing, one is fishing, their postures are each different. When the mind roams this landscape, a light breeze gently strokes and birds sing to the ear. The nostalgic dream of Chiang-nan, is carried from so far away by a segment of bamboo.

Bamboo wrist rest titled Spring Scenery in Chiang-nan carved by Chang Hsi-huang

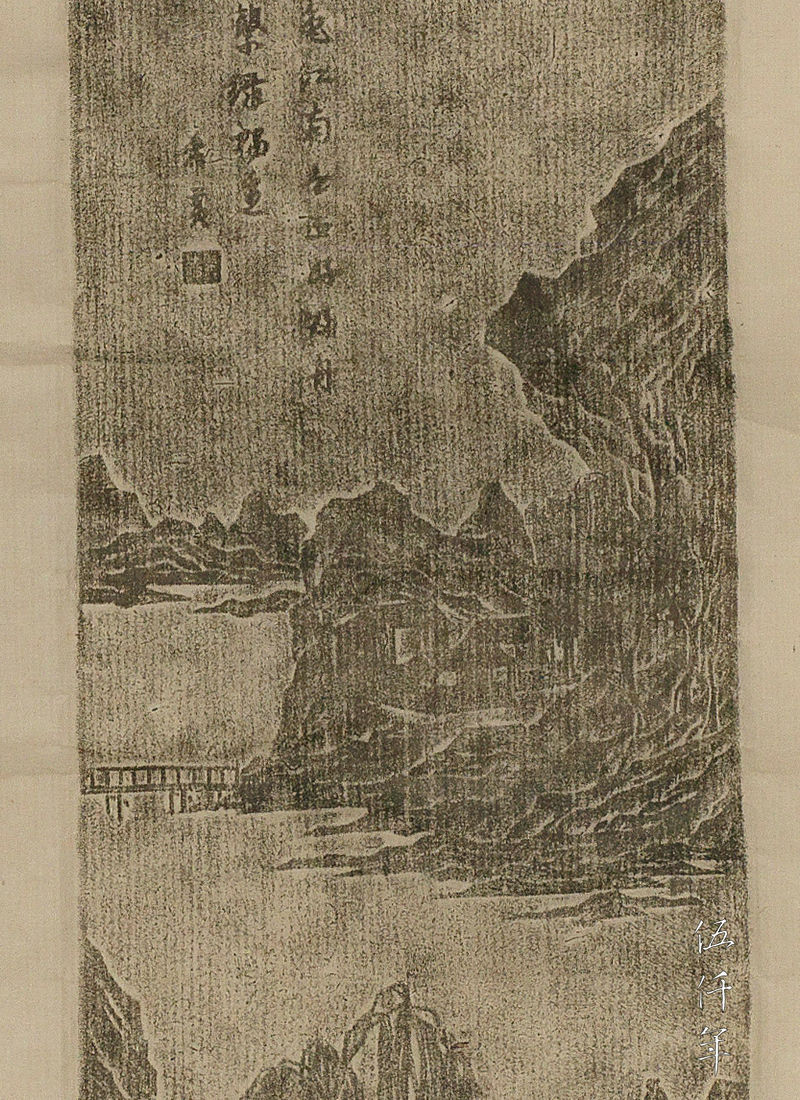

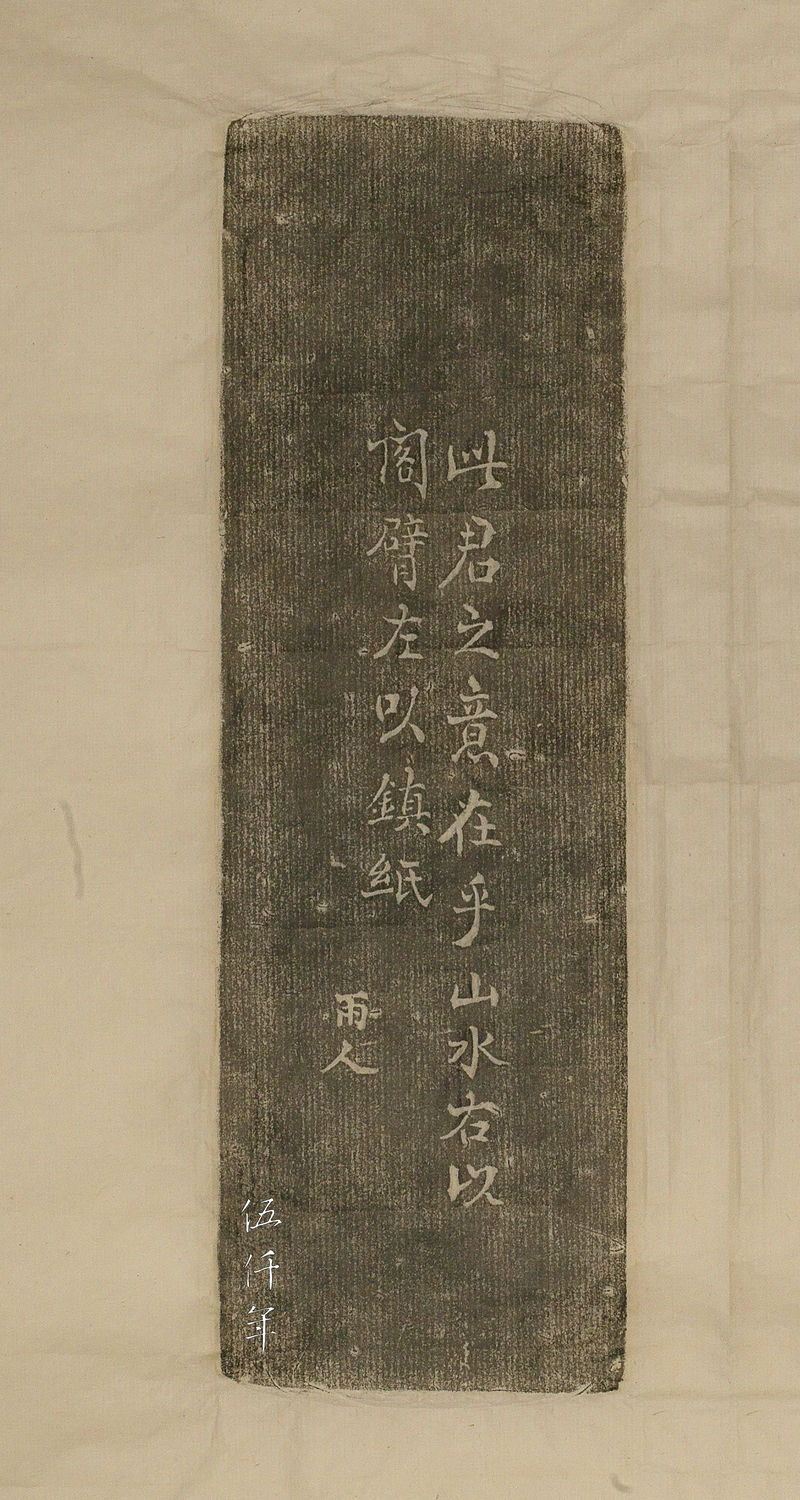

Ink rubbing of bamboo wrist rest titled Spring Scenery in Chiang-nan carved by Chang Hsi-huang

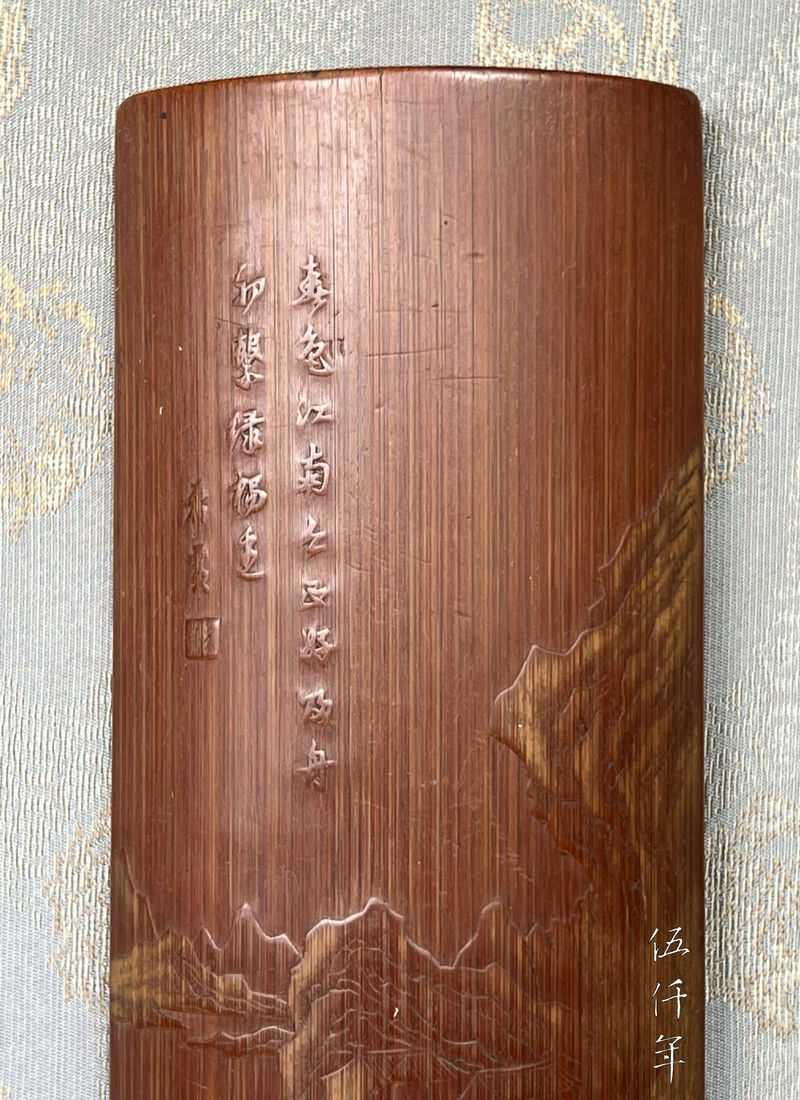

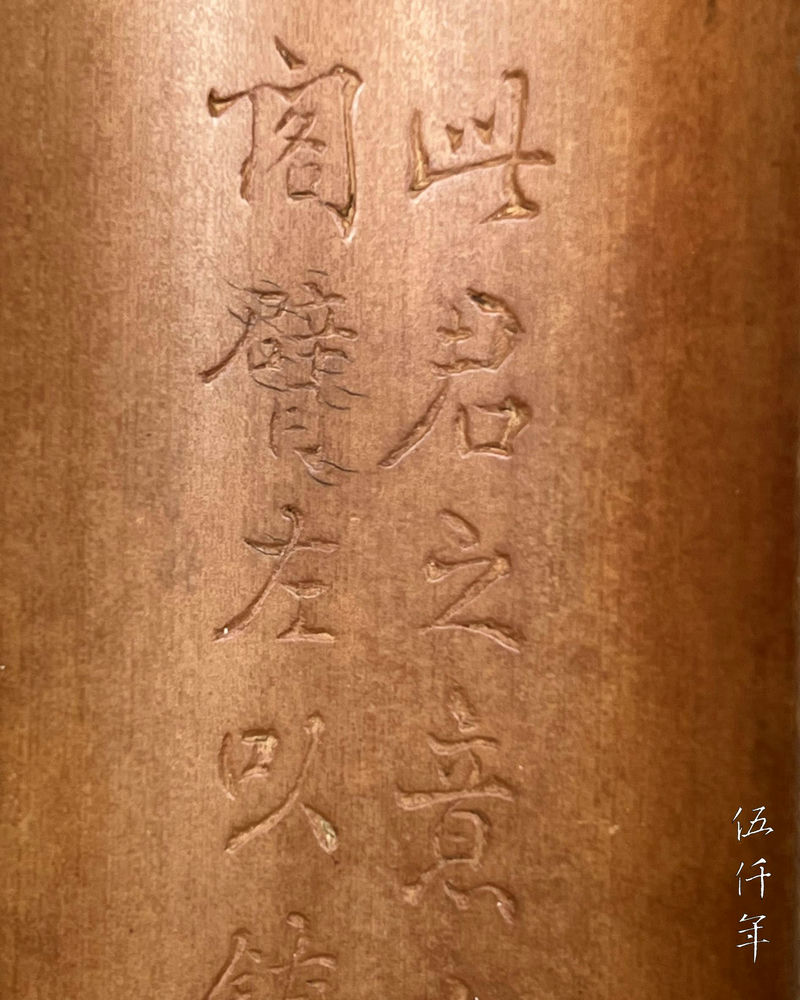

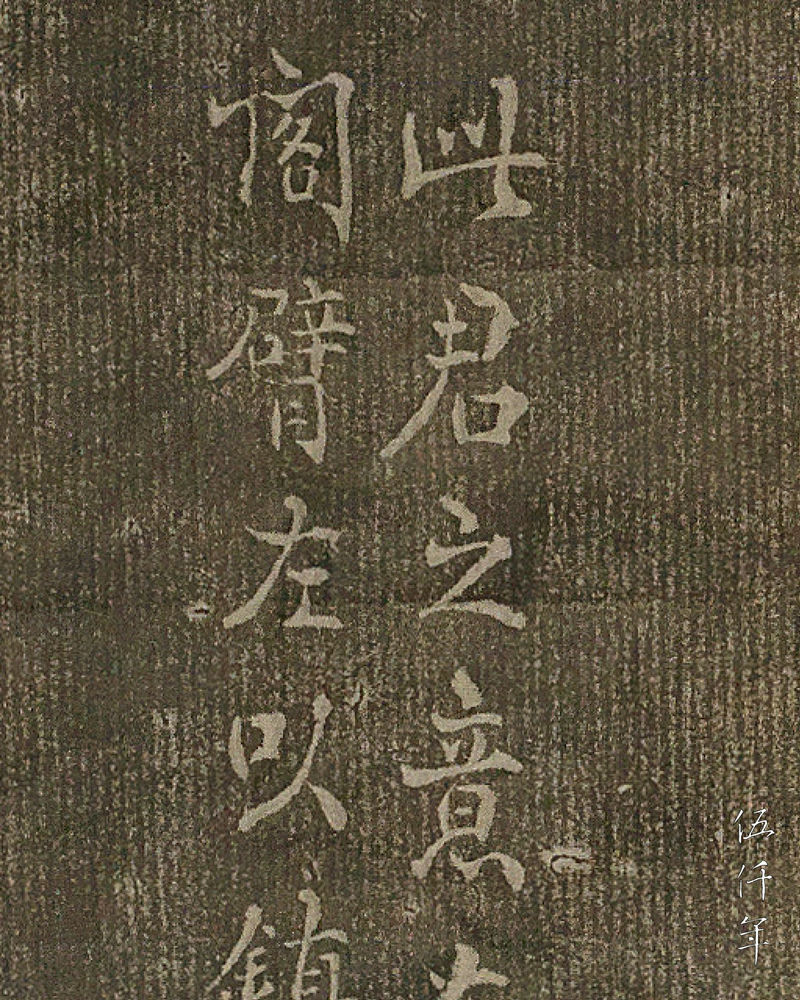

Upper section of bamboo wrist rest titled Spring Scenery in Chiang-nan carved by Chang Hsi-huang

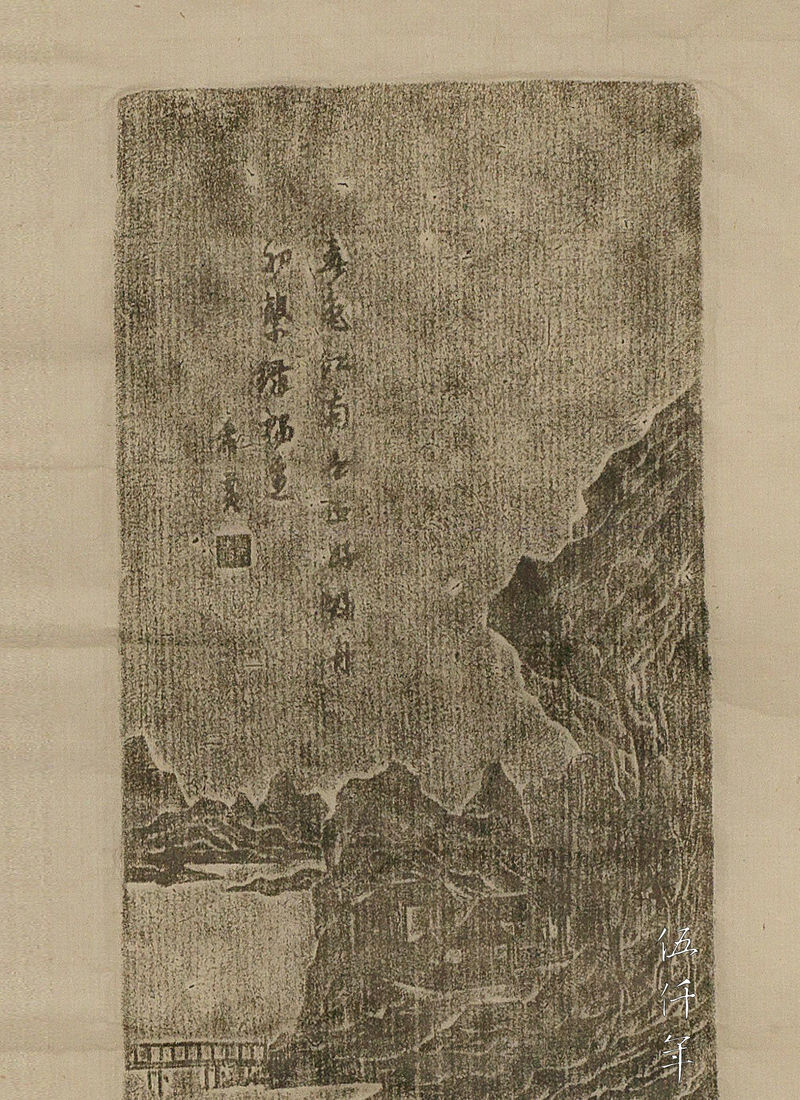

Ink rubbing of upper section of bamboo wrist rest titled Spring Scenery in Chiang-nan carved by Chang Hsi-huang

Middle section of bamboo wrist rest titled Spring Scenery in Chiang-nan carved by Chang Hsi-huang

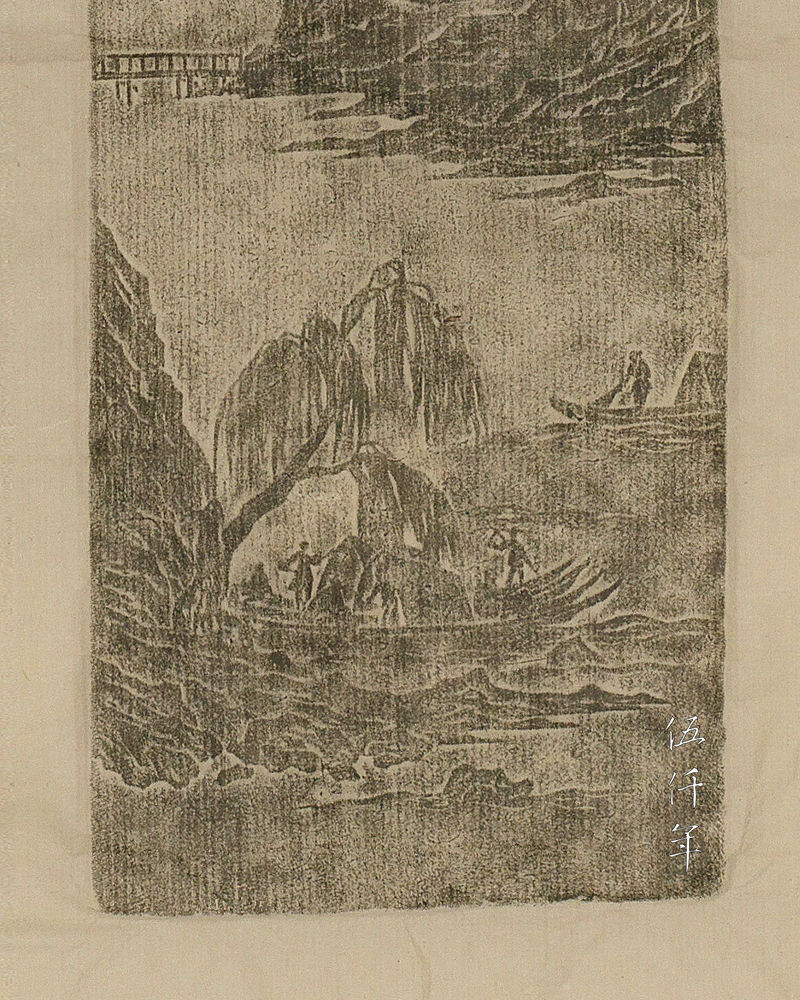

Ink rubbing of middle section of bamboo wrist rest titled Spring Scenery in Chiang-nan carved by Chang Hsi-huang

Lower section of bamboo wrist rest titled Spring Scenery in Chiang-nan carved by Chang Hsi-huang

Ink rubbing of lower section of bamboo wrist rest titled Spring Scenery in Chiang-nan carved by Chang Hsi-huang

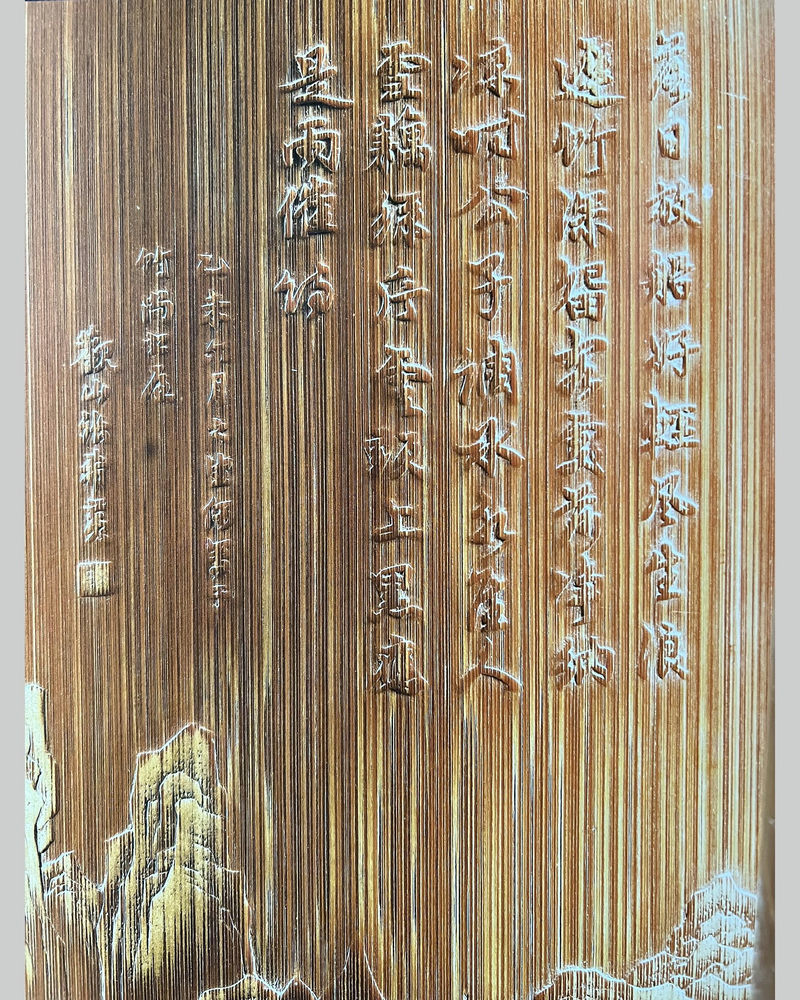

Chang Hsi-huang engraved two lines of running and cursive script on the wrist rest. The words are:

“Spring scenery in Chiang-nan is lovely today,

Homeward boats just tied to green willow side.

Hsi-huang.”

There is a miniature intaglio seal : Hsi-huang

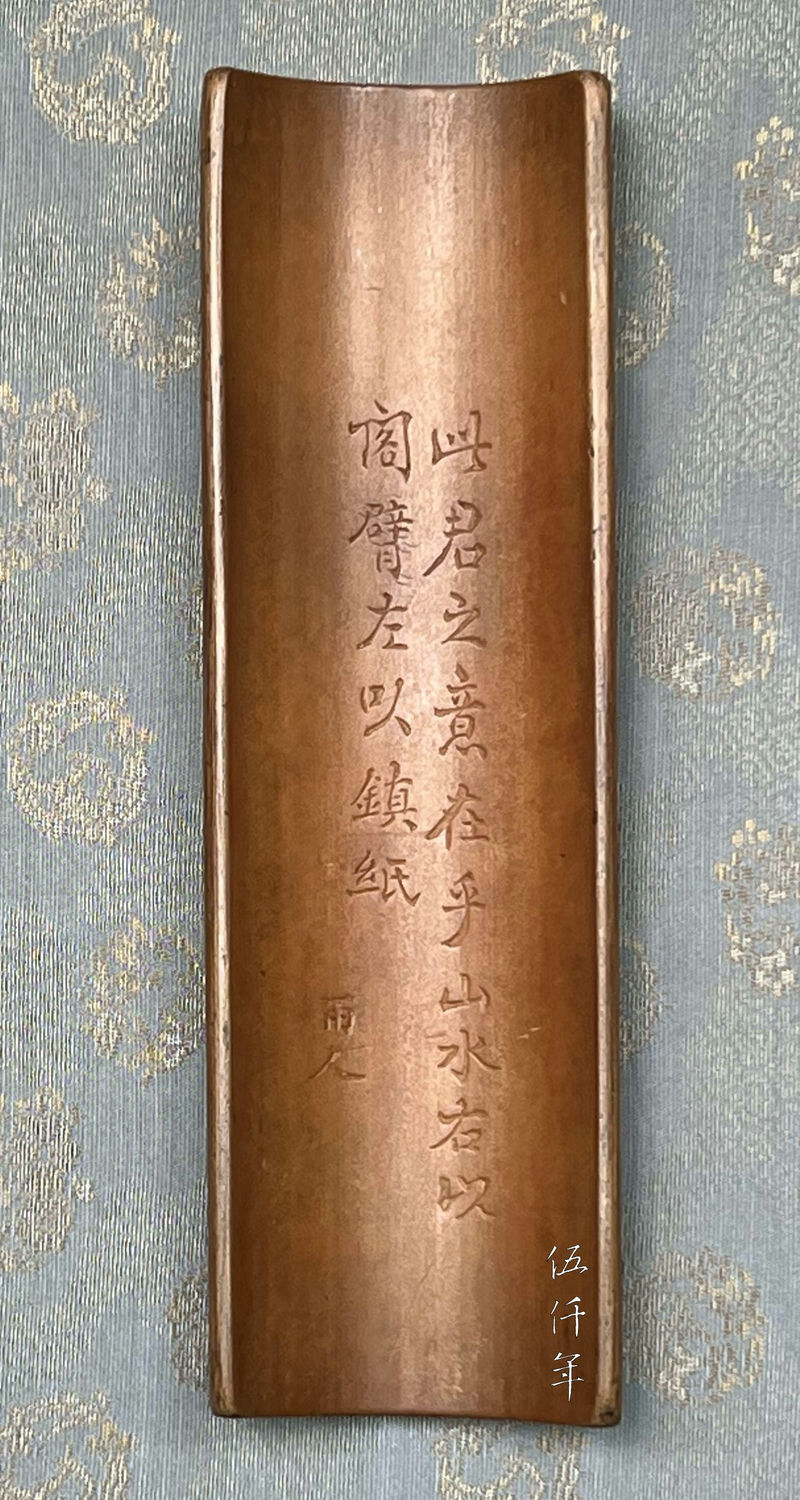

Back of bamboo wrist rest titled Spring Scenery in Chiang-nan carved by Chang Hsi-huang

Inkrubbing of back of bamboo wrist rest titled Spring Scenery in Chiang-nan carved by Chang Hsi-huang

Upper section of back of bamboo wrist rest titled Spring Scenery in Chiang-nan carved by Chang Hsi-huang

Ink rubbing of upper section of back of bamboo wrist rest titled Spring Scenery in Chiang-nan carved by Chang Hsi-huang

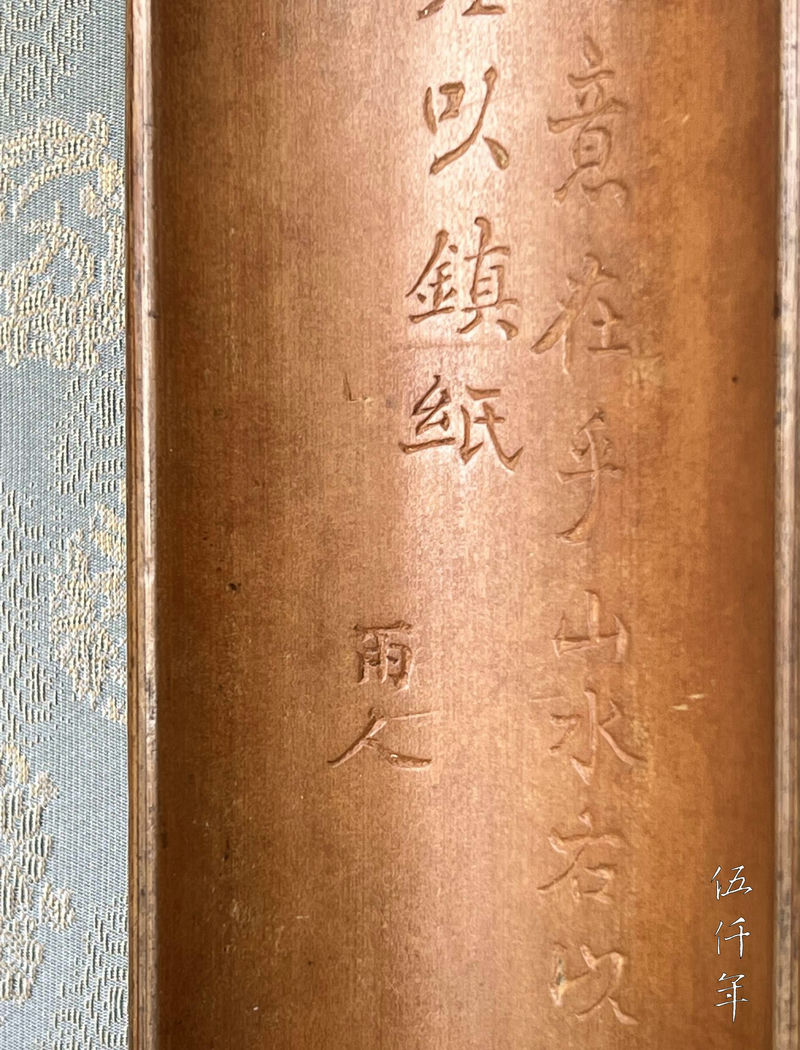

Lower section of back of bamboo wrist rest titled Spring Scenery in Chiang-nan carved by Chang Hsi-huang

Ink rubbing of lower section of back of bamboo wrist rest titled Spring Scenery in Chiang-nan carved by Chang Hsi-huang

At the back of the wrist rest, there are another two lines engraved in regular script by someone else. The words are:

“The intent of this gentleman is the landscape. On the right it is a wrist rest, on the left it is a paperweight.

Yü-jen (雨人).”

Yü-jen. Is this person from the Ming dynasty? Is this person from the Ch’ing dynasty? Gazing into the opaque past, the identity is too hazy to uncover. We only know that once upon a time, the landscape art of Chang Hsi-huang had a true devotee. He wrote and carved these words to express his poetic temperament, he stroked the wrist rest and immersed himself in daydreams, sometimes he used it as a wrist rest to support his brushwork, sometimes he used it as a paperweight to rest on his elegant writing paper.

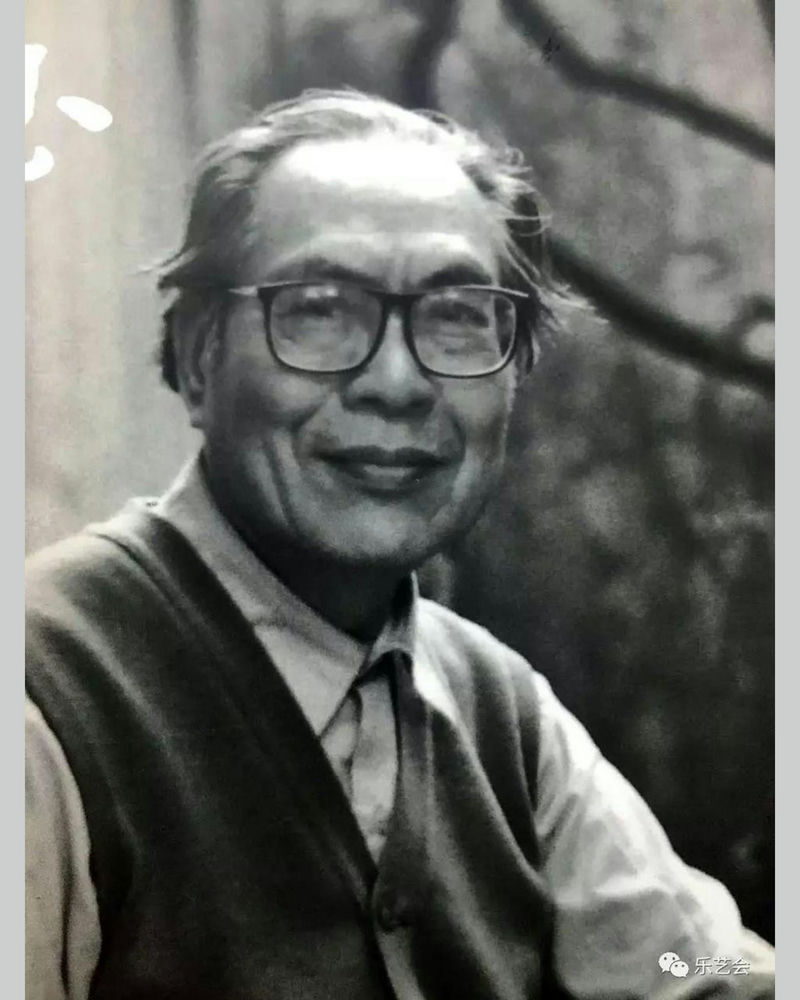

Portrait of Kuo Jo-yü

Mr. Kuo Jo-yü passed away in jen-ch’en year (壬辰 2012). Within a few years, the art collection he built in his lifetime was dispersed. In ping-shen year (丙申 2016), I was fortunate to acquire this wrist rest by Chang Hsi-huang, the very piece that my late friend dearly cherished and held in custody against all odds for sixty years. Through a tortuous path it arrived at my modest studio. I pondered that this piece had passed through numerous collections in the last few hundred years, its encounters impossible to unravel. Among the successive collectors, perhaps there had also been friends who passed it on from one to another.

The art collection of Mr. Kuo Jo-yü was mainly formed before the fall of mainland China to the communists in the 39th year of the Republic (1949) and during the years shortly after. All refined pursuits were no longer tolerated by the time of the successive communist purges. Later during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), his home was ransacked by the Red Guards, and not only was his whole art collection pillaged, but his wife also suffered permanent brain damage from fear and anxiety. After the Cultural Revolution, those antiques, calligraphy, and paintings plundered by the communists that were deemed more recent and of less value were occasionally returned, those from earlier dynasties that were more valuable were confiscated, with some ending up in public museums. Hence the Sung dynasty artworks in the collection of Mr. Kuo Jo-yü were all confiscated into the Shanghai Museum. Whenever he talked about it, each time brought fresh pain.

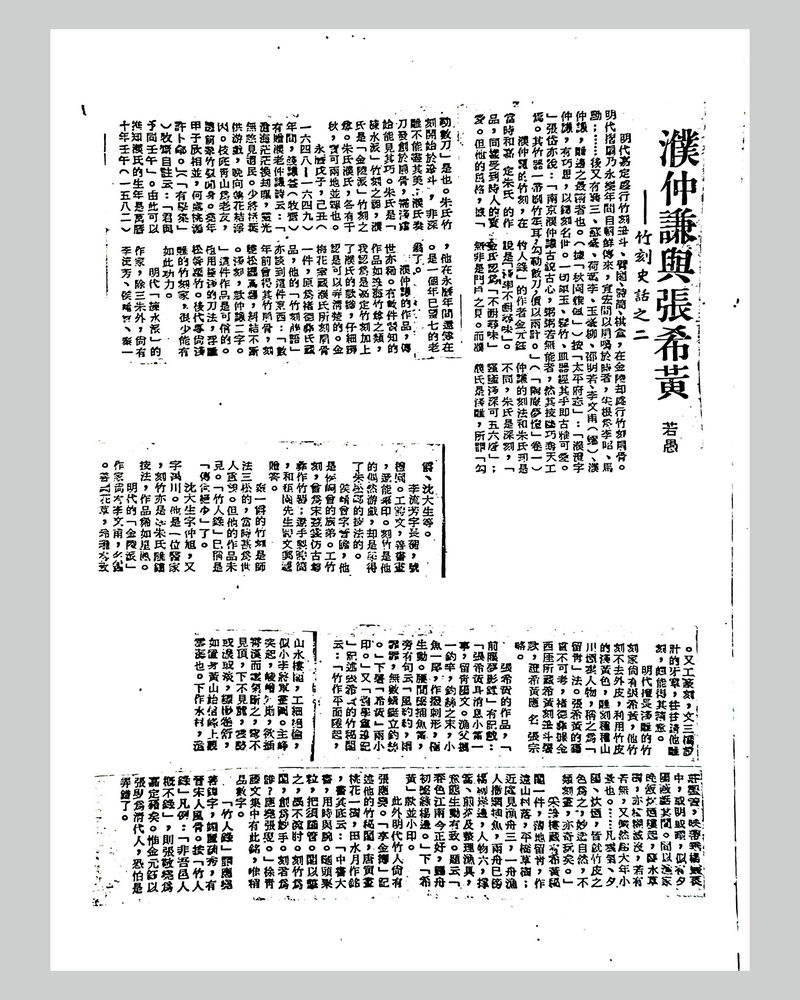

Newspaper clippings of the article P’u Chung-ch’ien and Chang Hsi-huang by Kuo Jo-yü

In early 1950s, Mr. Kuo Jo-yü wrote an article titled P’u Chung-ch’ien and Chang Hsi-huang (濮仲謙與張希黃) for a newspaper. A few selected paragraphs state:

“In the Ming dynasty, there was another bamboo engraver who specialized in shallow carving named Chang Hsi-huang. He did not remove the culm sheath, he used its light yellow colour to carve all sorts of landscapes, clouds and figures. This technique is called liu-ch’ing (留青). It is no longer possible to ascertain which province or town he came from. Che Te-i (褚德彝 1871-1942) cited the names carved on the brush pot by Chang Hsi-huang in the collection of Chin Hsi-ya (金西厓 1890-1979), as proof that the original name of Chang Hsi-huang was Chang Tsung-lüeh (張宗略).

A Record of Memories and Dreams chronicles a small brush pot carved by Chang Hsi-huang

The works of Chang Hsi-huang are documented in A Record of Memories and Dreams (Ch’ien-ch’en meng-ying lu 前塵夢影錄), which says:

“Reportedly Chang Hsi-huang engraved a small brush pot in the style of liu-ch’ing and the words in relief legend. A fisherman held a fishing rod, and at the end of the fishing line, there was a small fish, its tail flapping in the water. It was most animated. A small fishing bucket was tied around the waist. These lines were carved:

A gentle breeze, a misty drizzle, and countless dragonflies perch on the fishing line.

A small seal with the name Hsi-huang was carved underneath.”

In the Notes from the Studio of Ancient Scholarship (Chiu-hsüeh An pi-chi 舊學盦筆記), a bamboo wrist rest by Chang Hsi-huang was also documented. It says:

“The bamboo is elevated on the surface, the work of landscape and the pavilions are extraordinarily fastidious. It resembles a painting by Li Chao-tao (李昭道 675-758 AD). The main peak looms, a towering range that tries to pierce the sky but interrupted by the clouds. Uphill the mountain top cannot be seen, on the descent the foothills cannot be seen. The clouds are sometimes dense and sometimes light, they float and fold, the spectator seems to be on top of the Shih-hsin Peak of Huangshan Mountain surveying the sea of clouds. In the lower part of the composition, there is a village by the water, the cabins and cottages of the fishermen, the draping willows, and clusters of flowering grass, form a continuous vista. The scene alternates between light and dark, as if the setting sun appears and disappears now and then. Sporadically threads of cooking smoke from the fishermen’s dinners rise. The grass and trees by the water are blurred and faded, barely tangible. Then again it resembles a small composition by Chao Ling-jang (趙令穰) of the Sung dynasty…………….Wherever there are clouds, sunset, cooking smoke, they are made according to the colour of the culm sheath. It is ingenious and natural, unlike an engraving. It is a remarkable art object.”

There is a wrist rest engraved by Chang Hsi-huang in the collection of the Studio of Articulate Brush (Ts’ai-pi Lou 采筆樓). It was lightly carved in the technique of liu-ch’ing. The subjects are distant mountains, village, beam bridge, grass, trees, and three fishing boats in the foreground. The fishermen on one boat are casting a fishing net, the other two fishing boats are already moored next to the willow trees by the shore. There are six human figures, rowing, preparing tea, and sorting out fishing gear. Their postures are lively and interesting. The inscription reads:

Spring scenery in Chiang-nan is lovely today,

Homeward boats just tied to green willow side.

There is a signature of Hsi-huang and a small seal of Hsi-huang underneath.”

Mr. Kuo Jo-yü used quite a number of studio names, which appeared in his authoritative book The Art of Seal Engraving in China - Biographies of Selected Artists. Other than Ts’ai-pi Lou (采筆樓) and Chin-mei-hua Shih (金梅花室), there are T’a-yin An (塔印盦), I-yen Shih (伊硯室), Kuei-lai-yen Chai (歸來硯齋), Chou Chai (籀齋), K’uei Chai (夔齋) and Ko-yen Shih (个硯室).

Front cover of Small Talk on Bamboo Carving by Chin Hsi-ya

Inside page of Small Talk on Bamboo Carving with the portrait of Chin Hsi-ya

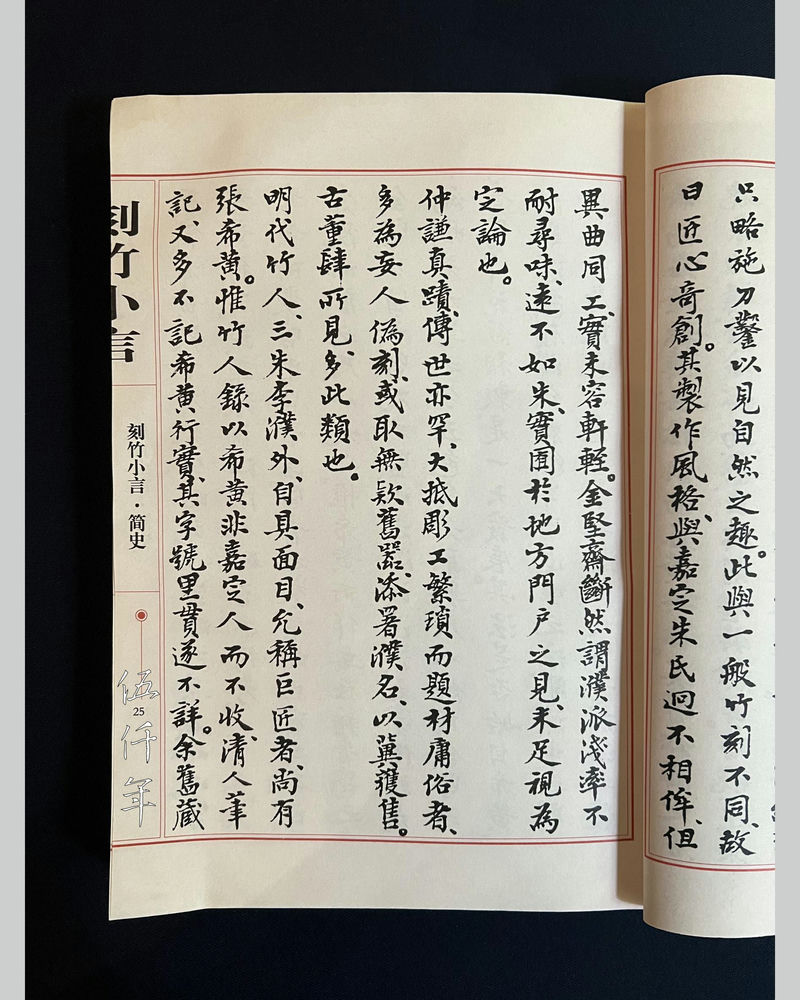

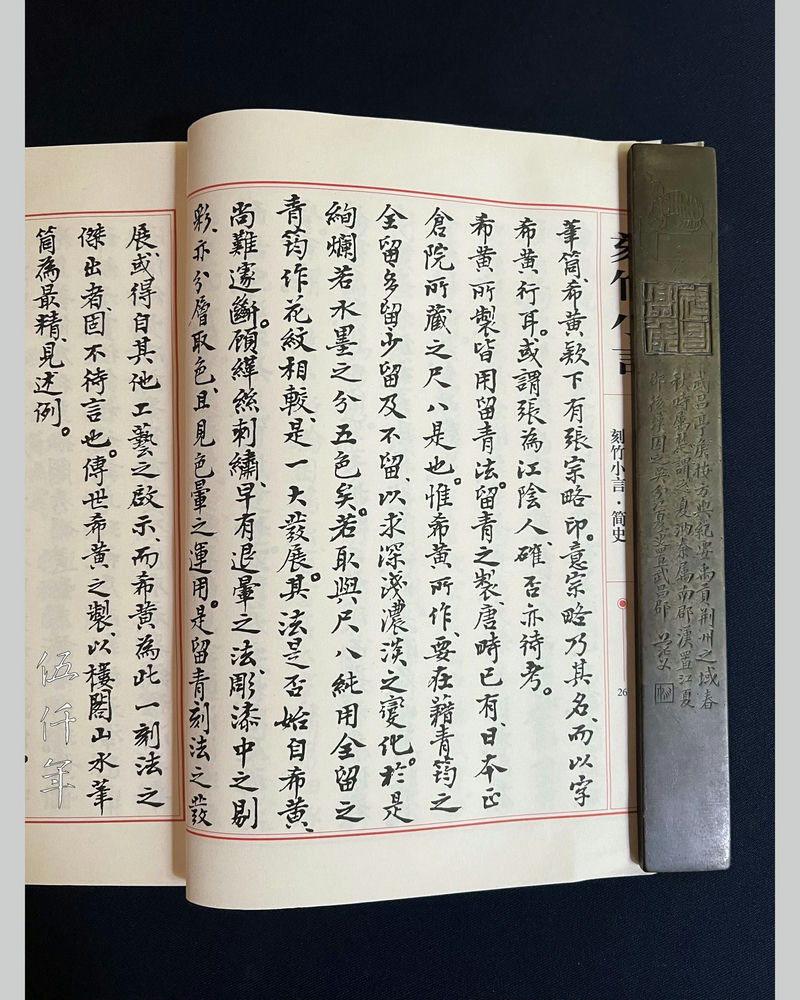

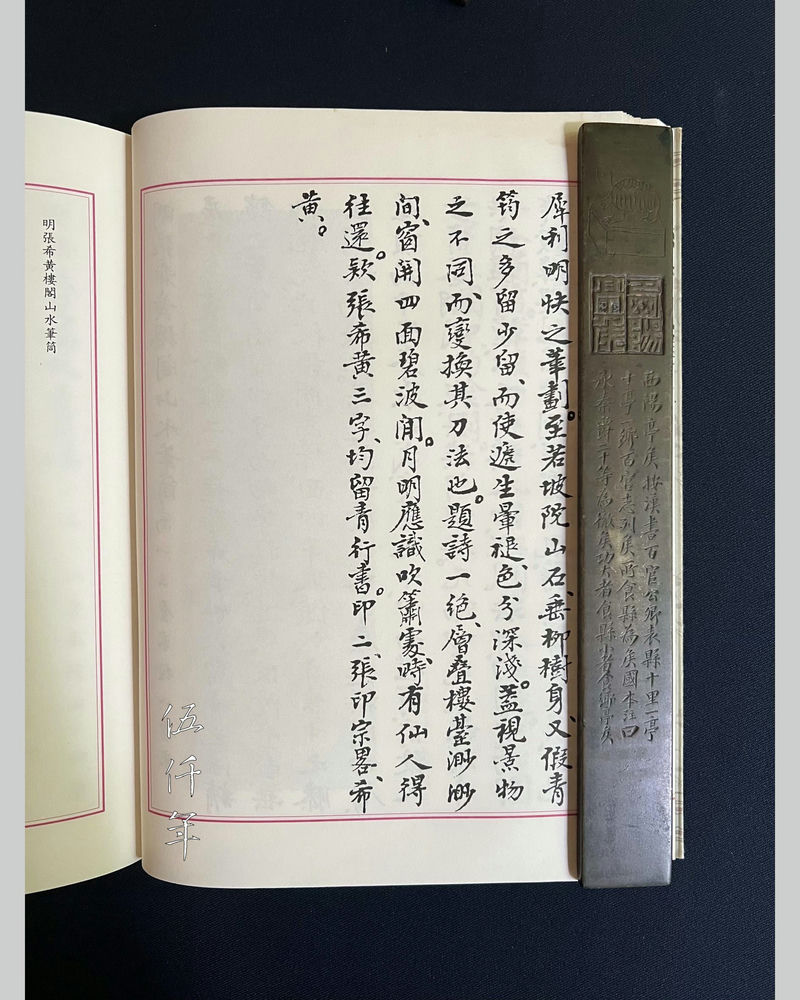

Inside page of Small Talk on Bamboo Carving on the art of Chang Hsi-huang

Inside page of Small Talk on Bamboo Carving on the art of Chang Hsi-huang

The eminent bamboo engraver Chin Hsi-ya wrote in his book Small Talk on Bamboo Carving (K’ei-chu hsiao-yen 刻竹小言):

“Regarding the bamboo engravers of the Ming dynasty, apart from the Three Chu: Chu Ho (朱鶴), Chu Ying (朱纓), Chu Chih-cheng (朱稚徵); Lee Yao (李耀) and P’u Chung-ch’ien (濮仲謙), who established their personal styles and were acknowledged as doyens, there was in addition Chang Hsi-huang. Since Chang Hsi-huang was not a native of Chia-ting, he was excluded from the Record of Bamboo Engravers (Chu-jen lu 竹人錄), nor was he much documented in the literary works of the Ch’ing dynasty. Consequently his deeds, names and provincial origin became obscure. I previously collected a brush pot, beneath the signature of Hsi-huang, there was a seal of Chang Tsung-lüeh. This meant Tsung-lüeh was the original name, while Hsi-huang was the name he favoured for general usage. He has been referred to as a native of Chiang-yin which remains to be confirmed.

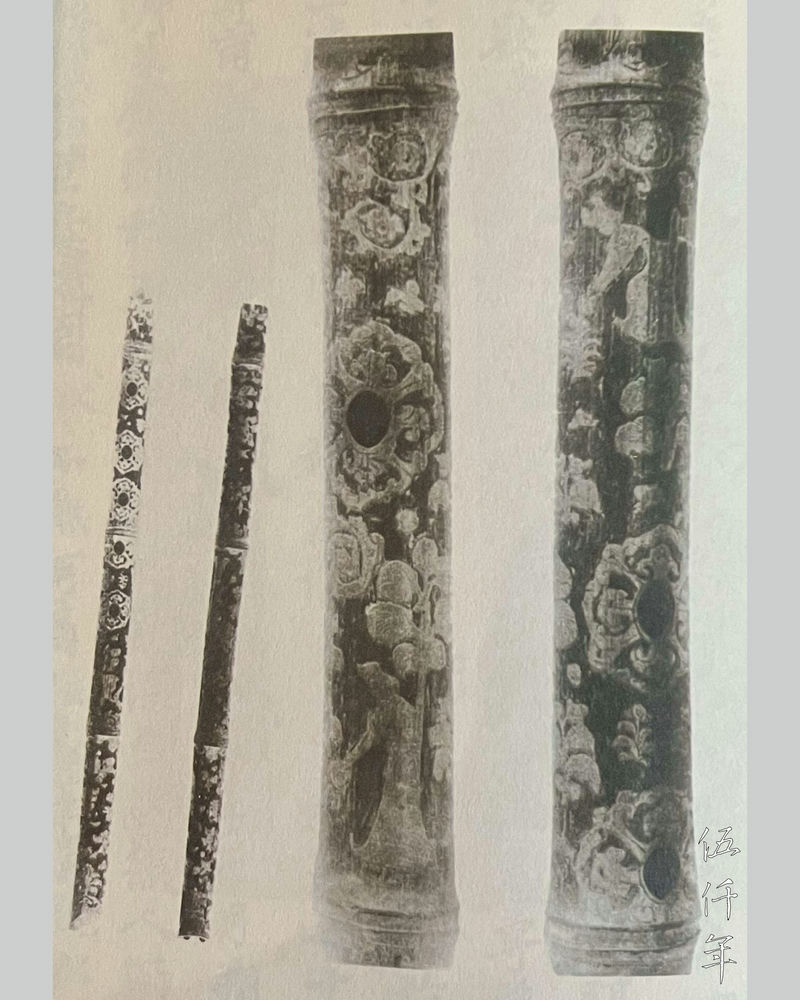

The Tang dynasty bamboo flute ch’ih-pa in the collection of the Shoso-in in Japan

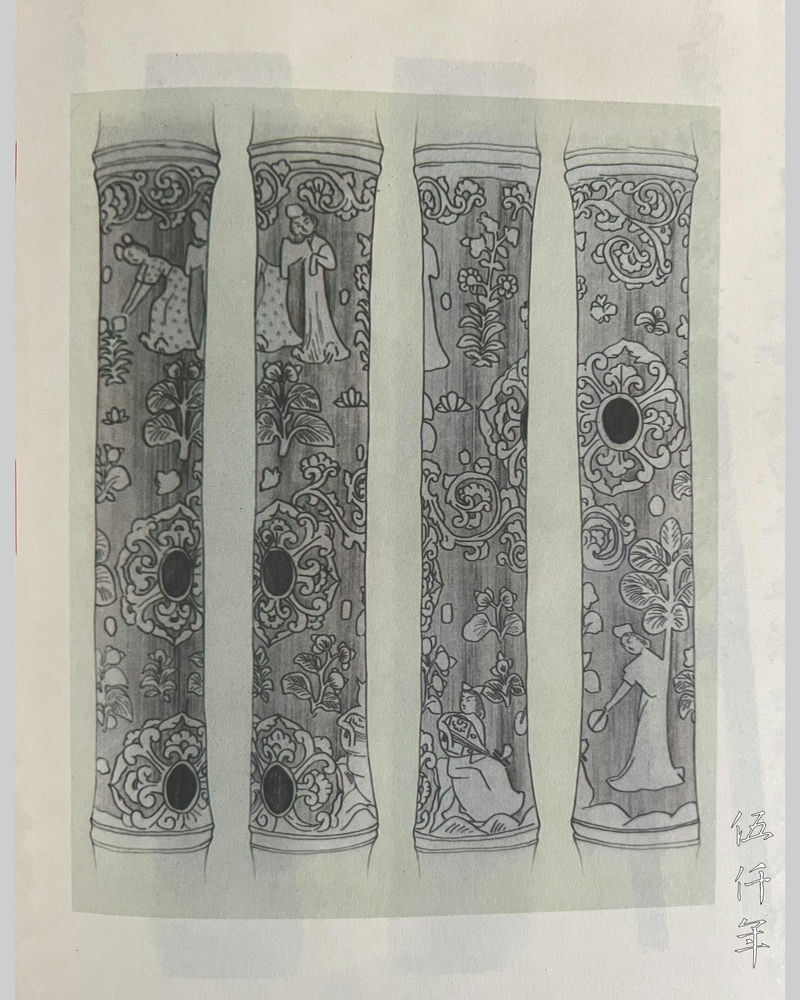

Details showing decorations of human figures, flowers and birds on the Tang dynasty ch’ih-pa in the collection of the Shoso-in

Sketched drawings of the details showing decorations of human figures, flowers and birds on the Tang dynasty ch’in-pa in the collection of the Shoso-in

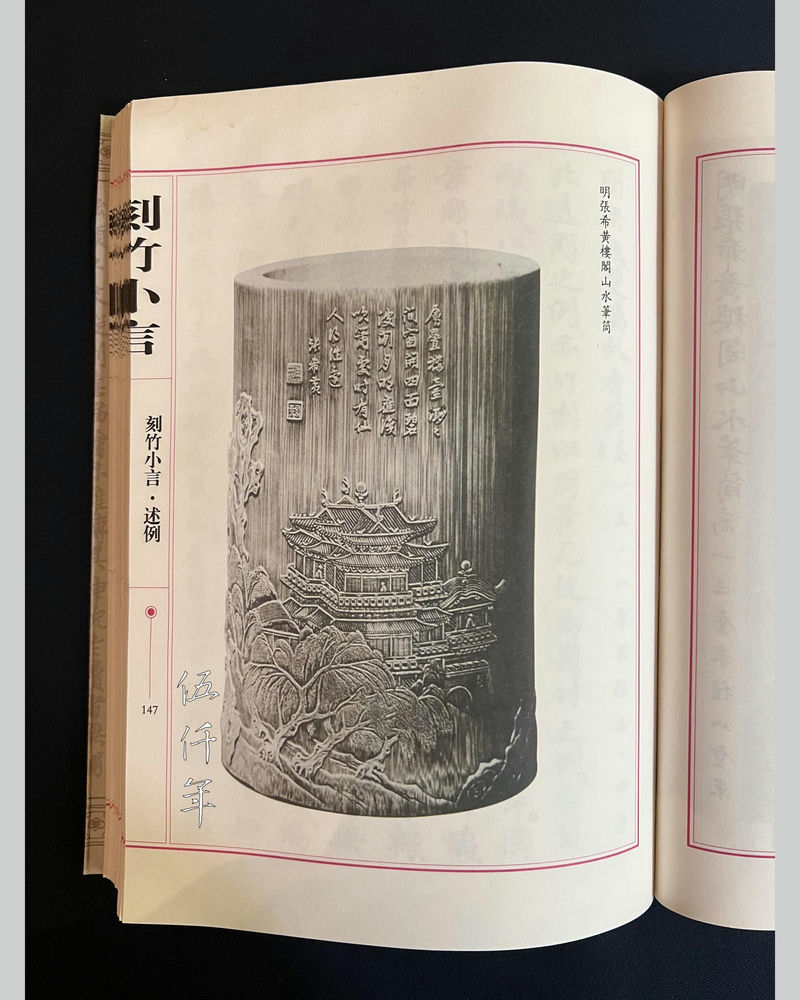

All the works of Chang Hsi-huang were executed using the technique of liu-ch’ing. The technique of liu-ch’ing was already practiced in the Tang dynasty (618-906 AD). An example is the bamboo flute called ch’ih-pa (尺八) in the collection of the Shoso-in in Japan. However, the works of Chang Hsi-huang depended upon the completeness of the culm sheath of bamboo, whether to retain more of it or less, to retain some or none, in order to achieve variations in depth and shallowness, denseness and lightness. Therefore its splendour is like the five colours of inkwork. If we compare the ch’ih-pa which retains all the culm sheath of bamboo for its floral decoration, this represents a tremendous advancement. It is difficult to establish if this technique used by Chang Hsi-huang was invented by him. Regarding the weaving method of k’ei-ssu (緙絲) and the needlework of embroidery (剌繡), the techniques to achieve colour change are long established. In polychrome lacquer work, colours are also drawn on different layers, and good use is made of colour change. Perhaps the development of the engraving technique of liu-ch’ing was inspired by the techniques from different crafts. Needless to say Chang Hsi-huang was a distinguished practitioner of this technique. Among the surviving works by Chang Hsi-huang, the Pavilion and Landscape Brush Pot, which is illustrated in the chapter of Exemplar, is the finest.”

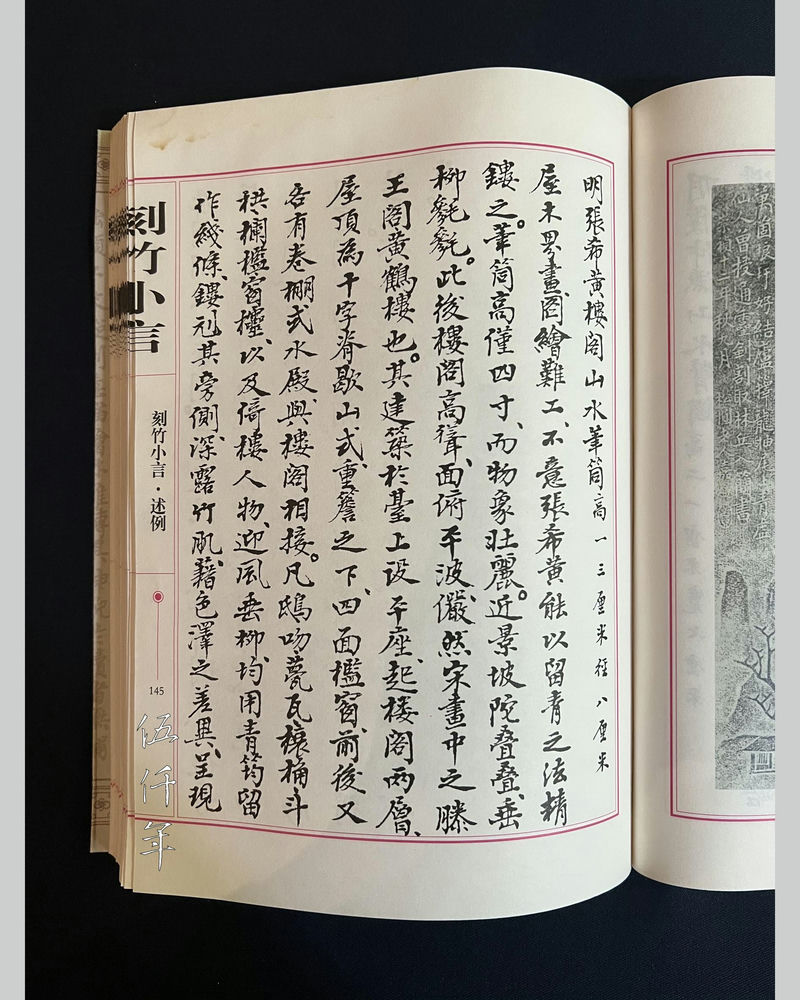

Inside page of Small Talk on Bamboo Carving describing the Pavilion and Landscape Brush Pot in the collection of Chin Hsi-ya

Inside page of Small Talk on Bamboo Carving describing the Pavilion and Landscape Brush Pot in the collection of Chin Hsi-ya

Inside page of Small Talk on Bamboo Carving illustrating the Pavilion and Landscape Brush Pot in the collection of Chin Hsi-ya

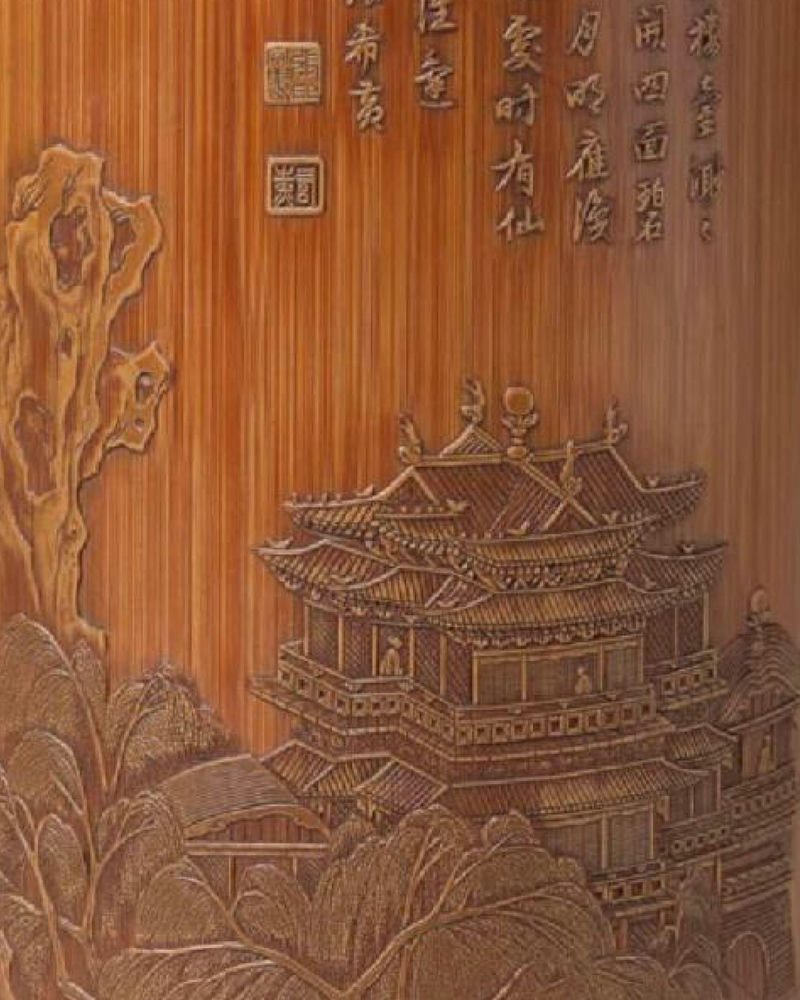

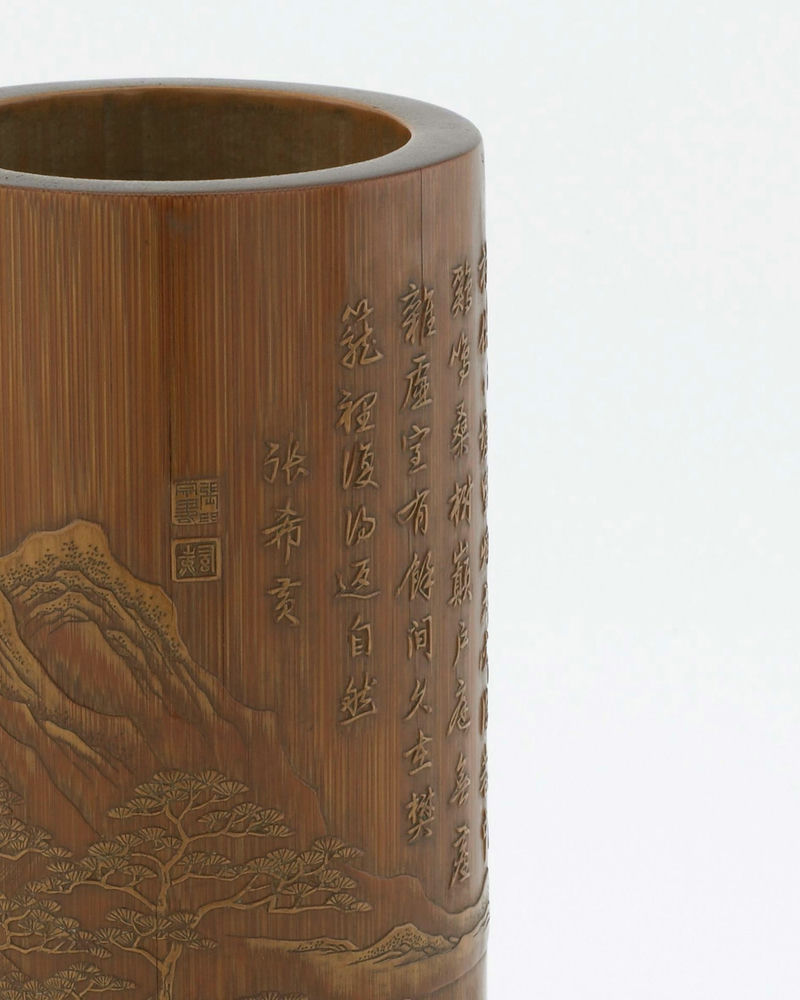

The Pavilion and Landscape Brush Pot that Chin Hsi-ya so deeply appreciated was a piece in his former collection. There is a black and white photograph of it in the chapter of Exemplar in Small Talk on Bamboo Carving. Next to the engraved signature of Hsi-huang, there are two engraved seals, “Seal of Chang Tsung-lüeh” and “Hsi-huang”. Based on this evidence, Chin Hsi-ya concluded that the former was the original name, and the latter his tzu. On 14 December 1976, the Pavilion and Landscape Brush Pot by Chang Hsi-huang was sold at the Sotheby’s sale in London to the Oriental dealer Bluett and Sons, Ltd. In March the following year, it was resold to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The Pavilion and Landscape Brush Pot formerly in the collection of Chin Hsi-ya now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Bostion. Photograph courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Detail of the Pavilion and Landscape Brush Pot formerly in the collection of Chin Hsi-ya now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Bostion. Photograph courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Cultural Revolution launched by the communists lasted ten years and ended in 1976. Artworks ransacked from homes, if not falling within a designated premium grade, were mostly sold overseas for foreign exchange. The Pavilion and Landscape Brush Pot by Chang Hsi-huang was sold at auction in December 1976, whether this coincided with the confiscation of art during the Cultural Revolution, is difficult for outsiders to know for sure. When German Nazis in the past confiscated the art collections of European Jews, or forced them to sell for a pittance, their descendants nowadays can seek redress in the courts, and press their claims on those artworks in American and European Museums. When one day mainland China is finally cleansed, the descendants of those violated collectors who had no recourse to justice, may finally be able to resolve their grievances.

Bamboo brush pot by Chang Hsi-huang engraved with the poem Returning to Live in the Country by T’ao Ch’ien in the National Museum of Asian Art, Washington. Photograph courtesy National Museum of Asian Art, Washington

First detail of bamboo brush pot by Chang Hsi-huang engraved with the poem Returning to Live in the Country by T’ao Ch’ien in the National Museum of Asian Art, Washington. Photograph courtesy National Museum of Asian Art, Washington

Second detail of bamboo brush pot by Chang Hsi-huang engraved with the poem Returning to Live in the Country by T’ao Ch’ien in the National Museum of Asian Art, Washington. Photograph courtesy National Museum of Asian Art, Washington

The surviving works by Chang Hsi-huang are as rare as the morning stars. In the National Museum of Asian Art in Washington, there is a bamboo brush pot by Chang Hsi-huang engraved with the poem Returning to Live in the Country (歸園田居) by T’ao Ch’ien (陶潛 365-427 AD). Next to the engraved signature of Chang Hsi-huang, are two small engraved seals “Seal of Chang Tsung-lüeh” and “Hsi-huang”. The seals are the same as those on the brush pot at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Front of bamboo brush pot by Chang Hsi-huang engraved with the essay Second Ode to the Red Cliffs by Su Shih in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Photograph courtesy Ashmolean Museum

Back of bamboo brush pot by Chang Hsi-huang engraved with the essay Second Ode to the Red Cliffs by Su Shih in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Photograph courtesy Ashmolean Museum

In the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford in Britain, there is a bamboo brush pot by Chang Hsi-huang engraved with the essay Second Ode to the Red Cliffs (後赤壁賦) by Su Shih (蘇軾 1037-1101). There is an engraved inscription: “Fresh Autumn in ting-wei year (丁未), Chang Hsi-huang from O-ch’eng (鄂城).” Underneath are two small engraved seals “Seal of Chang Hsi-huang” and “Hsi-huang”. Ting- wei year can refer to the 35th year of the Wan-li reign (1607) in the Ming dynasty, or the 6th year of the K’ang-hsi reign (1667) in the Ch’ing dynasty. Since Chang Hsi-huang was a bamboo carver from late Ming, this piece should be dated the 35th year of the Wan-li reign (1607). O-ch’eng is a county in Hupeh Province. This would be the hometown of Chang Hsi-huang.

Bamboo wrist rest by Chang Hsi-huang engraved with the poem In the Company of Numerous Gentlemen with Courtesans at Chang-pa Canal One Evening to Cool Off Before Encountering the Rain by Tu Fu in the Shanghai Museum

First detail of bamboo wrist rest by Chang Hsi-huang engraved with the poem In the Company of Numerous Gentlemen with Courtesans at Chang-pa Canal One Evening to Cool Off Before Encountering the Rain by Tu Fu in the Shanghai Museum

Second detail of bamboo wrist rest by Chang Hsi-huang engraved with the poem In the Company of Numerous Gentlemen with Courtesans at Chang-pa Canal One Evening to Cool Off Before Encountering the Rain by Tu Fu in the Shanghai Museum

In the Shanghai Museum, there is a bamboo wrist rest by Chang Hsi-huang engraved with the poem In the Company of Numerous Gentlemen with Courtesans at Chang-pa Canal One Evening to Cool Off Before Encountering the Rain by Tu Fu (杜甫 712-770 AD). There is an engraved inscription: “On 16 June in i-wei year (乙未), I fortuitously engraved this at Chu-shang Shu-wu (竹尚書屋), Chang Hsi-huang from Kuan-shan (觀山).” Underneath there is a small engraved seal with the name “Hsi-huang”. Using the date of the brush pot at the Ashmolean Museum as reference, i-wei year should be the 23rd year of the Wan-li reign (1595). The two pieces were engraved by Chang Hsi-huang twelve years apart. There is a hill named Kuan-shan next to the South River of Ku Ch’eng County of Hupeh Province. Hence his native province was Hupeh.

Front of agarwood wine goblet by Chang Hsi-huang engraved with the theme Ode to the Red Cliffs by Su Shih in the Peking Palace Museum. Photograph courtesy Peking Palace Museum

Back of agarwood wine goblet by Chang Hsi-huang engraved with the theme Ode to the Red Cliffs by Su Shih in the Peking Palace Museum. Photograph courtesy Peking Palace Museum

In the Peking Palace Museum there is an agarwood wine goblet by Chang Hsi-huang engraved with the theme of Ode to the Red Cliffs by Su Shih. There is an engraved inscription: “Su Tung-p’o (Shih) Visiting the Red Cliffs by Boat.” Next to these words is a small oval seal with the characters “Hsi-huang-tzu (希黃子)”. This is the only work by Chang Hsi-huang using the official script calligraphy and the seal of Hsi-huang-tzu. This wine goblet is proof that Chang Hsi-huang also did carvings in wood. One may postulate that he also carved other utensils for daily usages, but with the passing of time very few pieces have survived.

Little is known of the life of Chang Hsi-huang. Books from the past rarely documented him. Surveying his existing pieces, a short profile is drafted in an attempt as supplement:

“Chang Tsung-lüeh, tzu Hsi-huang, hao Hsi-huang-tzu. He lived at Chu-shang Shu-wu, native of O-ch’eng, Hupeh Province. He was skilled in calligraphy, adept at seal engraving, and proficient in landscape painting. Yet these works are all lost. He particularly excelled in the liu-ch’ing technique of bamboo engraving. His surviving works in engraving include wrist rests, brush pots and a wine goblet. He carved mostly landscape. He was an eminent bamboo engraver during the Wan-li period of the Ming dynasty. His style was unique, totally different from other well-known bamboo engravers from Chia-ting in his time.”

For such an illustrious bamboo engraver of his generation, during his life there was scant record, in death there was no biography. It had to do with the carelessness and idleness of his contemporaries, and negligence of later generations. It is regrettable that since ancient times, countless talents who possessed unrivaled virtuosities, had gone unrecorded and their names sunk into oblivion. The sense of loss and disappointment are particularly strong when upon gathering the few remaining works by Chang Hsi-huang four hundred years later, only a few lines can trace and imagine his life.

Signature on bamboo wrist rest titled Spring Scenery in Chiang-nan carved by Chang Hsi-huang