In the past, Confucianists used the Four Cardinal Principles (四維) of Propriety (禮), Righteousness (義), Integrity (廉), and Shame (恥) to govern the country. People nowadays may find this incredible. In the 1st year of the T’ung-chih reign (1862), Wo Jen (倭仁), tutor to the Emperor, compiled the Golden Mirror for Instruction of the Heart to educate T’ung-chih Emperor. Some of his words are:

“Mencius denounced the idea of profit (利) and claimed it was wrong. Instead, Benevolence (仁) and Righteousness (義) are principles to save the world forever…..

Benevolence is derived from the love for others. It can embrace and safeguard the Four Seas. Righteousness is employed to deal with matters. It can manage and govern all human affairs.”

One can tell that Wo Jen used all his powers to resurrect Wang-tao (王道), the Way of the King, or the Way of Benevolence and Righteousness.

Tseng Kuo-fan (曾國藩) greatly respected and admired him. He even emulated Wo Jen‘s diary and praised it in these words: “each sentence is a remedy for self-improvement.”

Yet the one hundred and more volumes of Wo Jen’s diary have long disappeared, with the exception of one surviving volume. Of course one volume is scant, but it is ample to grasp the lost essential knowledge of Confucianism, the rules of admonitions for self-improvement and self-examination, as well as the moral conviction to recast the world in the principles of Benevolence and Righteousness. For contemporary scholars to read the diary, they may be inspired enough to follow suit.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

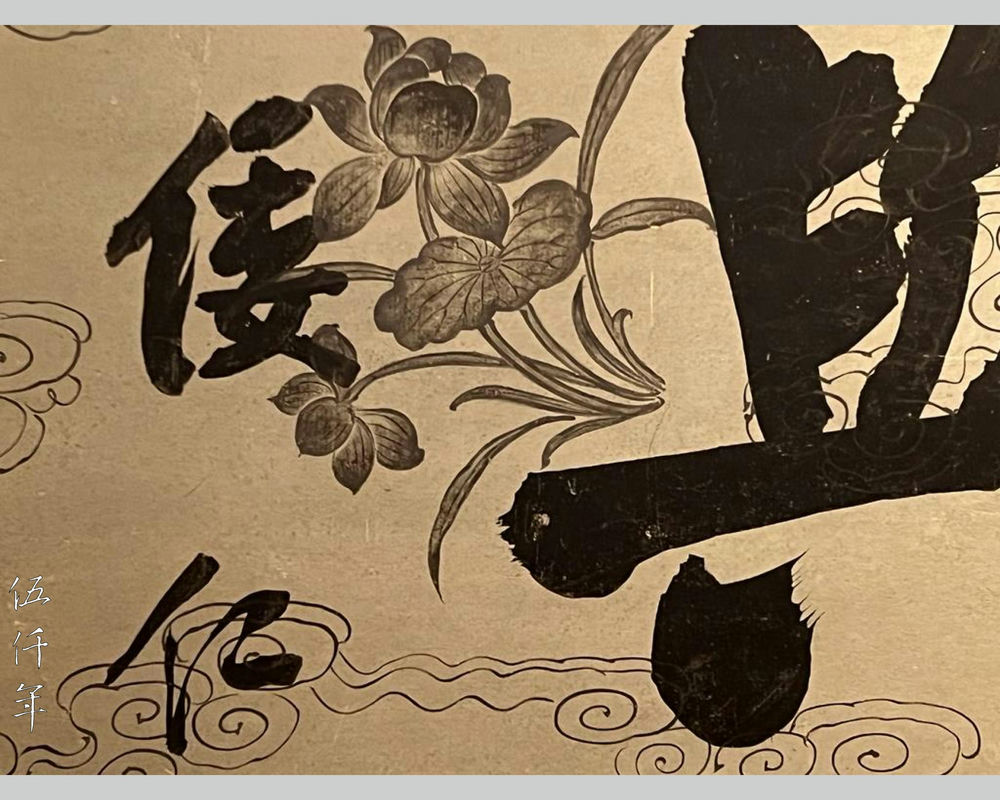

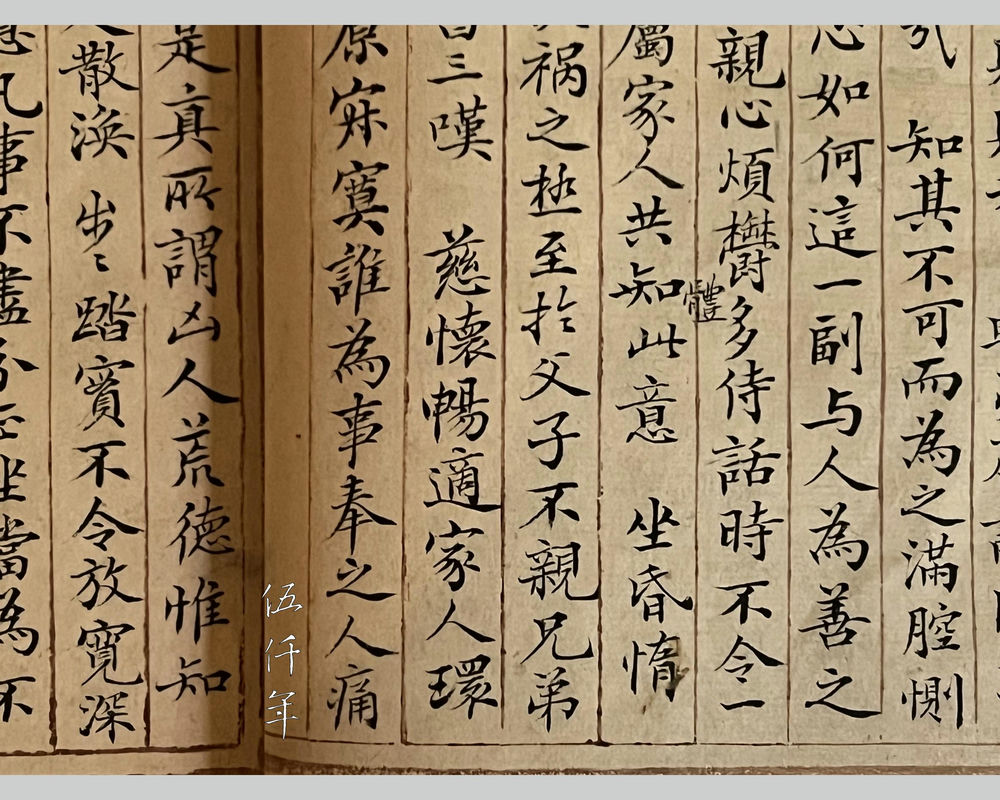

Detail of calligraphy couplet by Wo Jen

In the 12th year of the Republic (1923), my great-grandfather Mr. Soong Tsun-wang (宋尊望), hao Tzu-ho (子鶴), published Wen-miao-hsiang chai shih-ts’ao (Poems from the Studio of Wen-miao-hsiang 聞妙香齋詩草), a work by my second-great-grandfather Mr. Soong P’ei-ch’u (宋培初), tzu Ho-fang (鶴訪). There is a poem with the title Views in the Capital City. It reads:

Wheels and hooves are worn to tire,

Under the southern sky.

At long last I made my way

To the Imperial City this day.

May I boast of the Sixteen Prefectures?

A vista of infinite expanse.

Come ride the waves of giant whales,

Towers of measureless height.

Paintings and calligraphy by eminent men,

To be cherished to be saved.

A brushwork gift by the Grand Secretary,

Fond reminder of friendship bygone.

Vie to tread the bustling street,

Mount a tall horse to dart ahead.

Outside the gate the ancient capital stands,

Raise your whips for a race to serve.

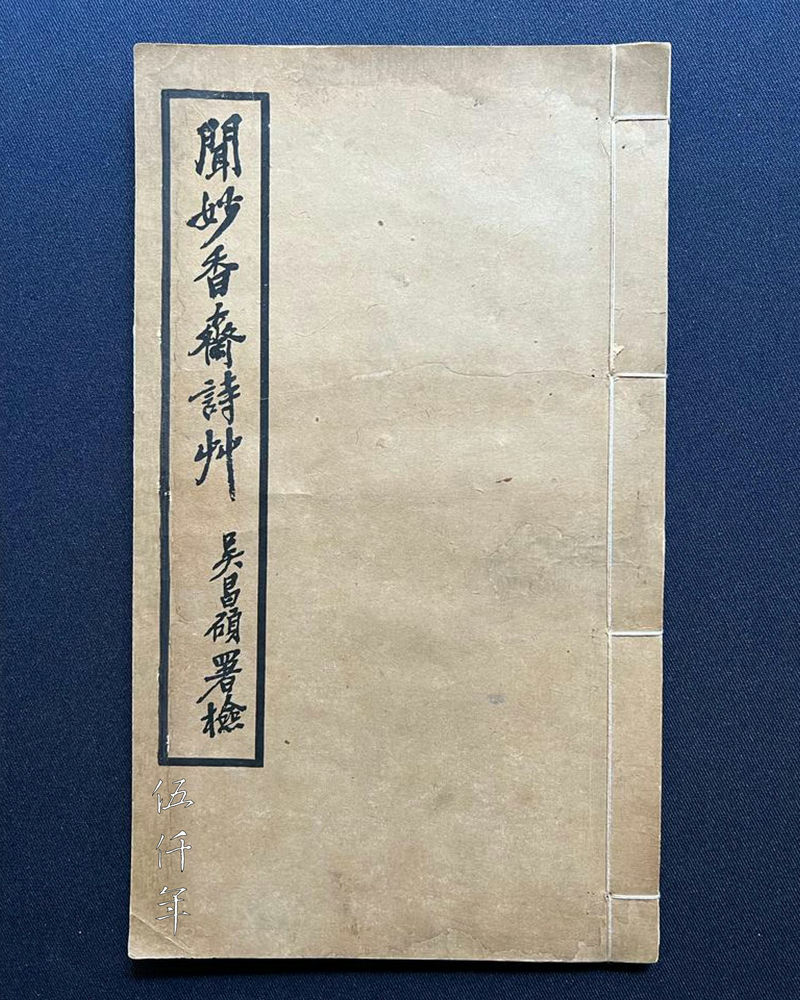

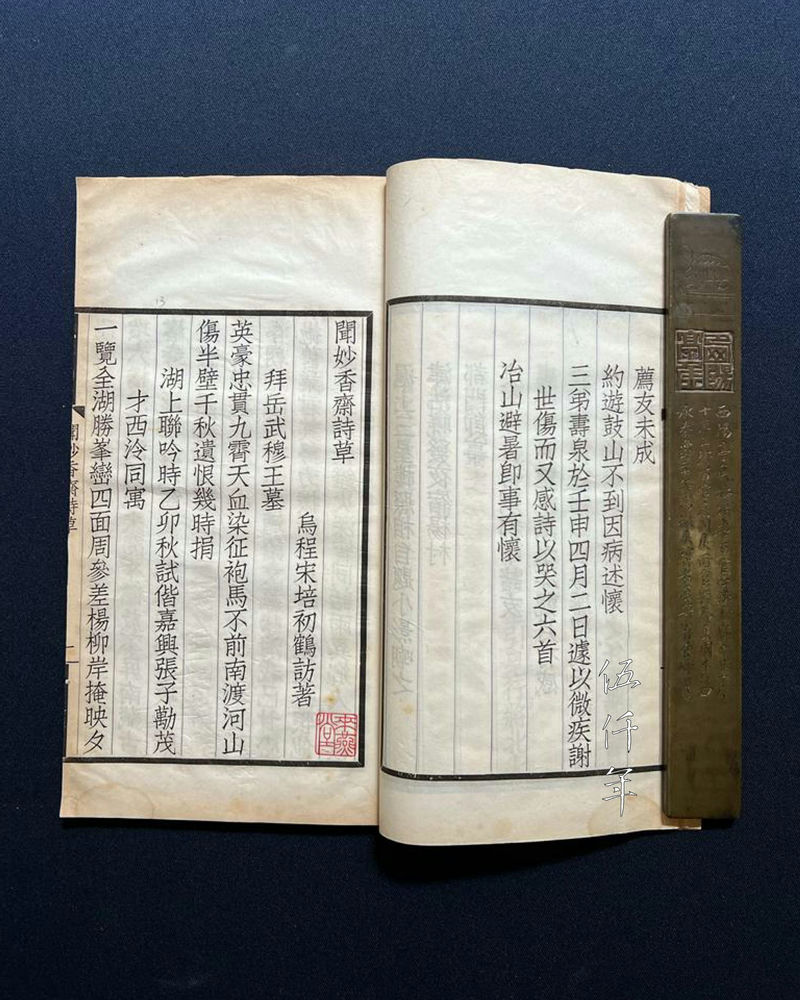

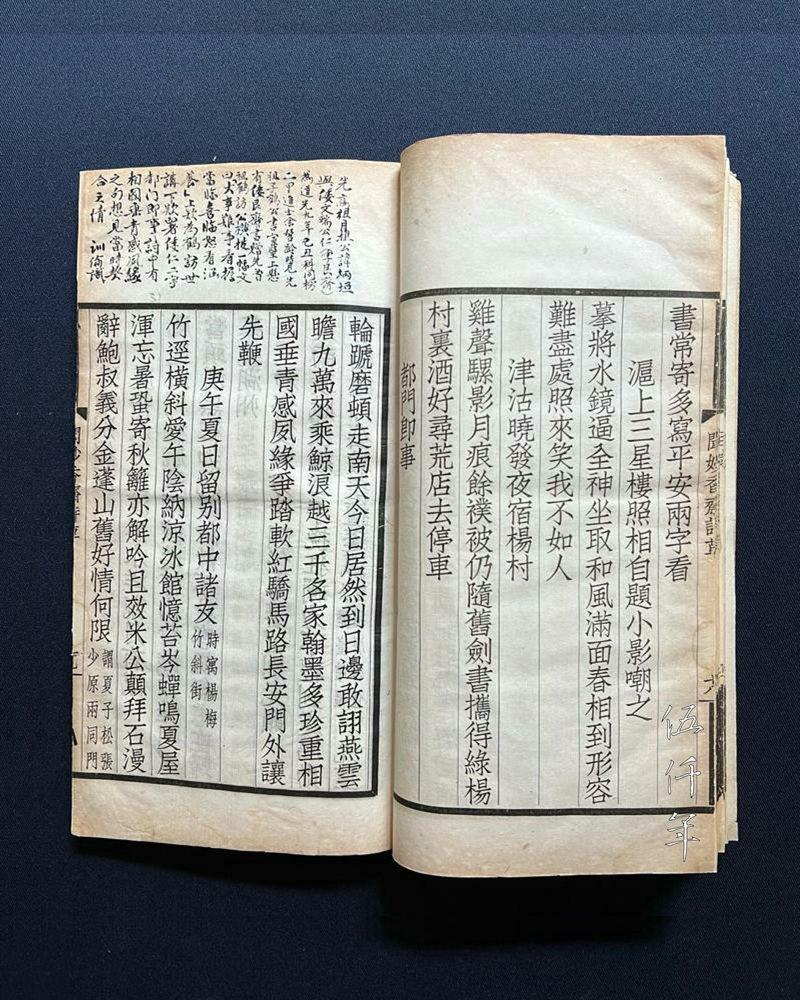

Front cover of Poems from the Studio of Wen-miao-hsiang by Mr. Soong P’ei-ch’u

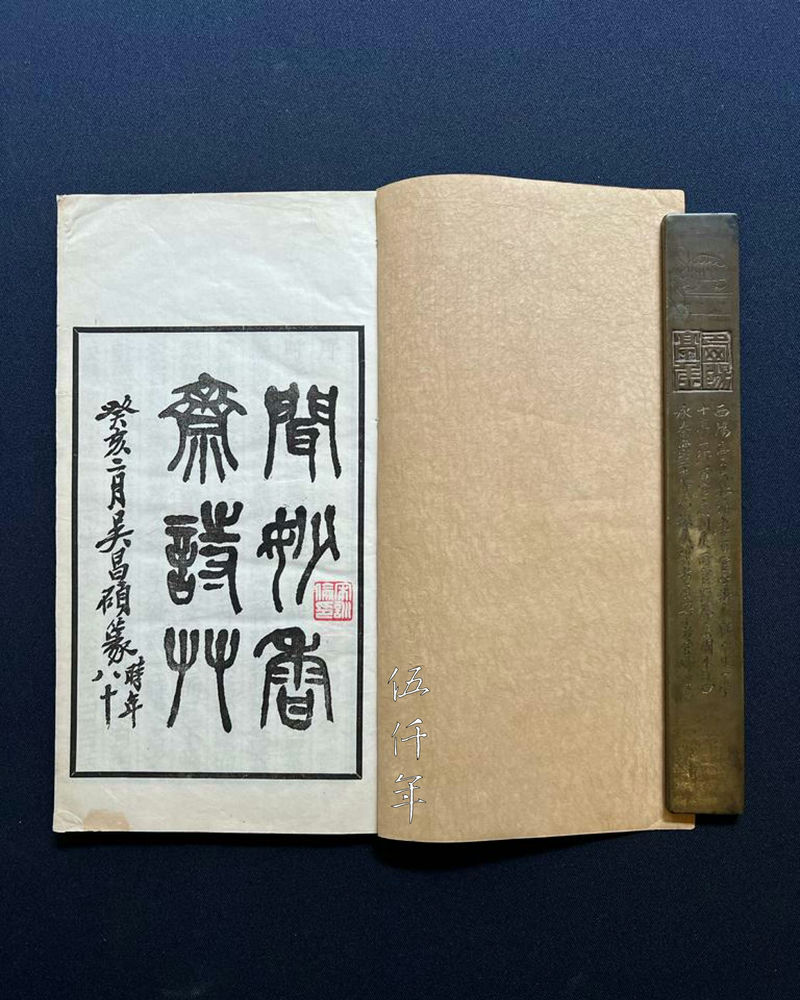

Title page of Poems from the Studio of Wen-miao-hsiang by Mr. Soong P’ei-ch’u

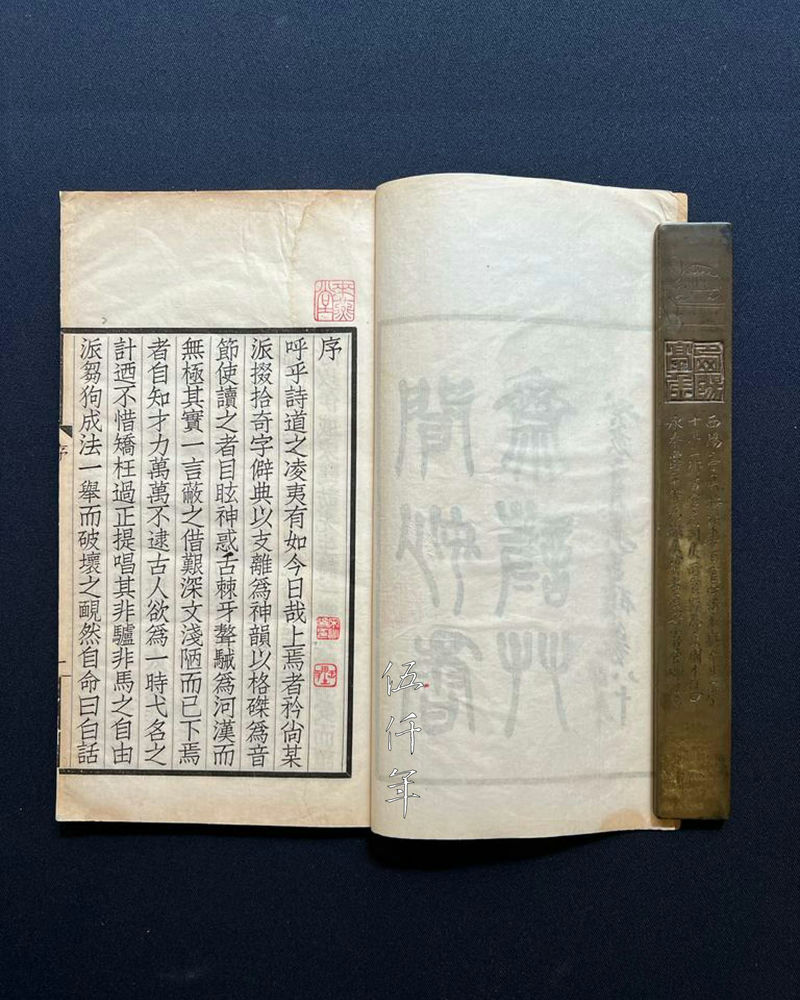

Inside page of Poems from the Studio of Wen-miao-hsiang by Mr. Soong P’ei-ch’u

Inside page of Poems from the Studio of Wen-miao-hsiang by Mr. Soong P’ei-ch’u

Views in the Capital City in Poems from the Studio of Wen-miao-hsiang

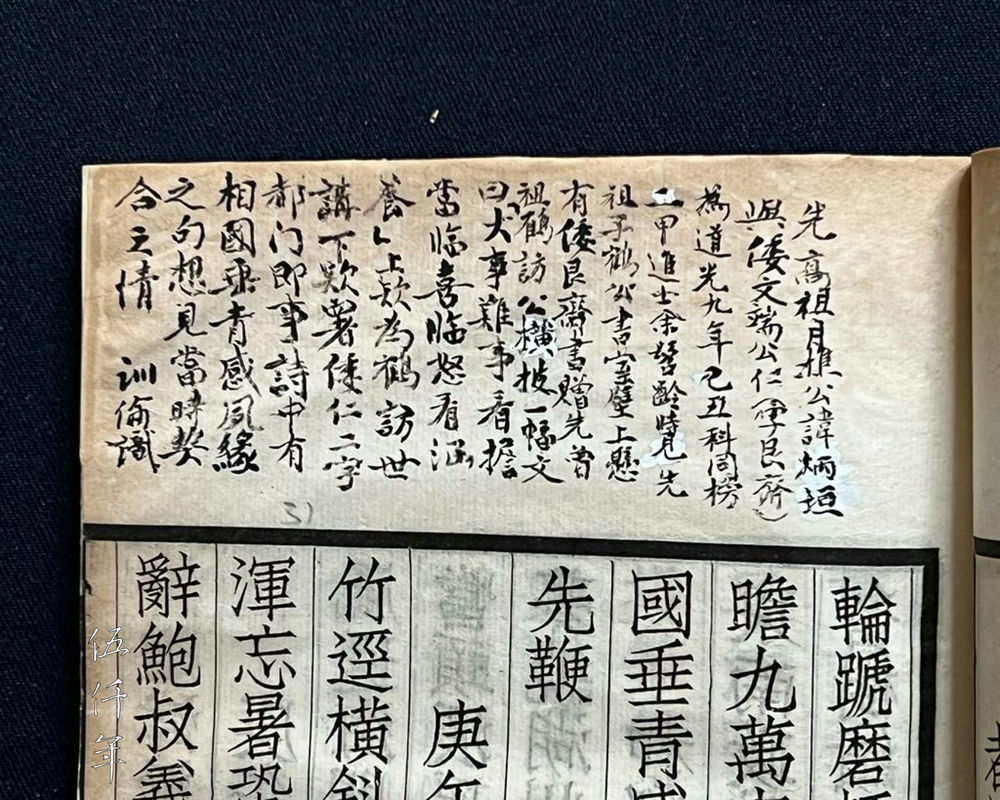

Inscription above Views in the Capital City by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

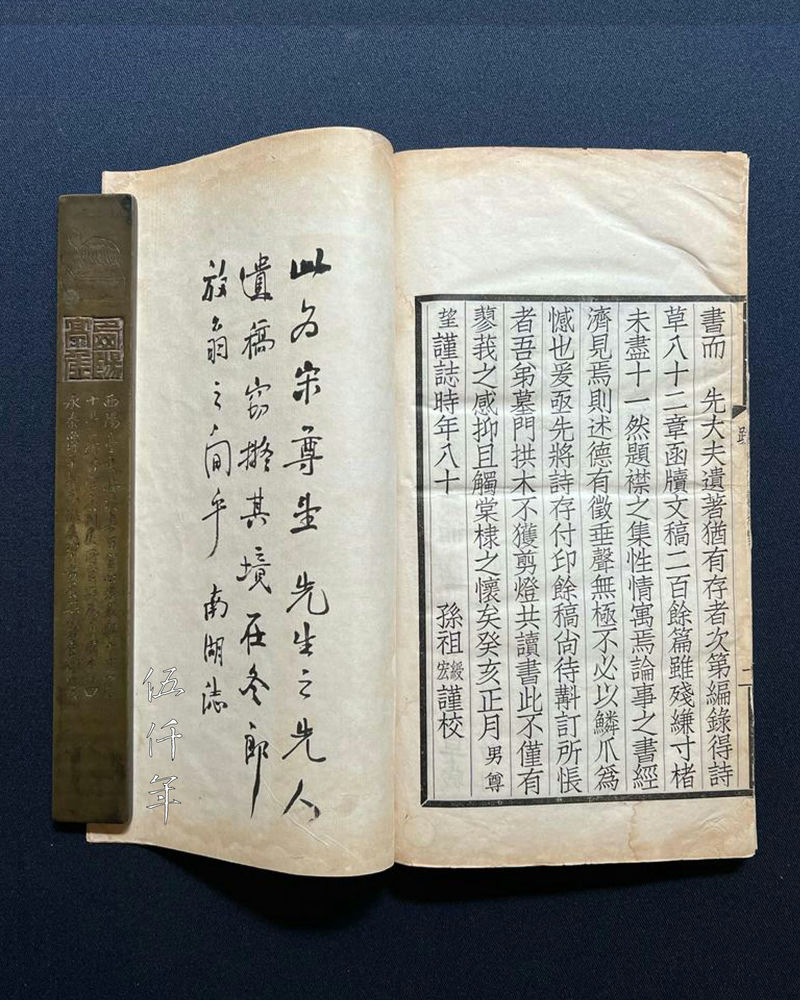

Inscription by Nan-hu on the last page of Poems from the Studio of Wen-miao-hsiang

My father Mr. Soong Hsün-leng (宋訓倫) inscribed these words above the poem:

“My second-great grandfather Mr. Soong Yüeh-ch’iao (宋月樵), his original name Ping-yüan (炳垣), together with Wo Jen (倭仁), attained the Second Class chin-shih degree (metropolitan graduate) at the chi-ch’ou year (己丑) examination in the 9th year of the Tao-kuang reign. When I was young, I saw a horizontal scroll hanging on the wall in the library of my grandfather Mr. Soong Tz’u-ho (宋子鶴). It was a gift from Wo Jen to my great grandfather Mr. Soong Ho-fang (宋鶴訪). The words were:

Grave and difficult tasks count on resilience,

Elation and rage are tackled by cultivation.

On the right, these words were inscribed:

To Ho-fang, son of my friend.

On the left, there was the signature:

Wo Jen.

In the poem Views in the Capital City, there are two lines:

A brushwork gift by the Grand Secretary,

Fond reminder of friendship bygone.

One can envisage their close relationship at that time.

Acknowledged by Hsün-leng.”

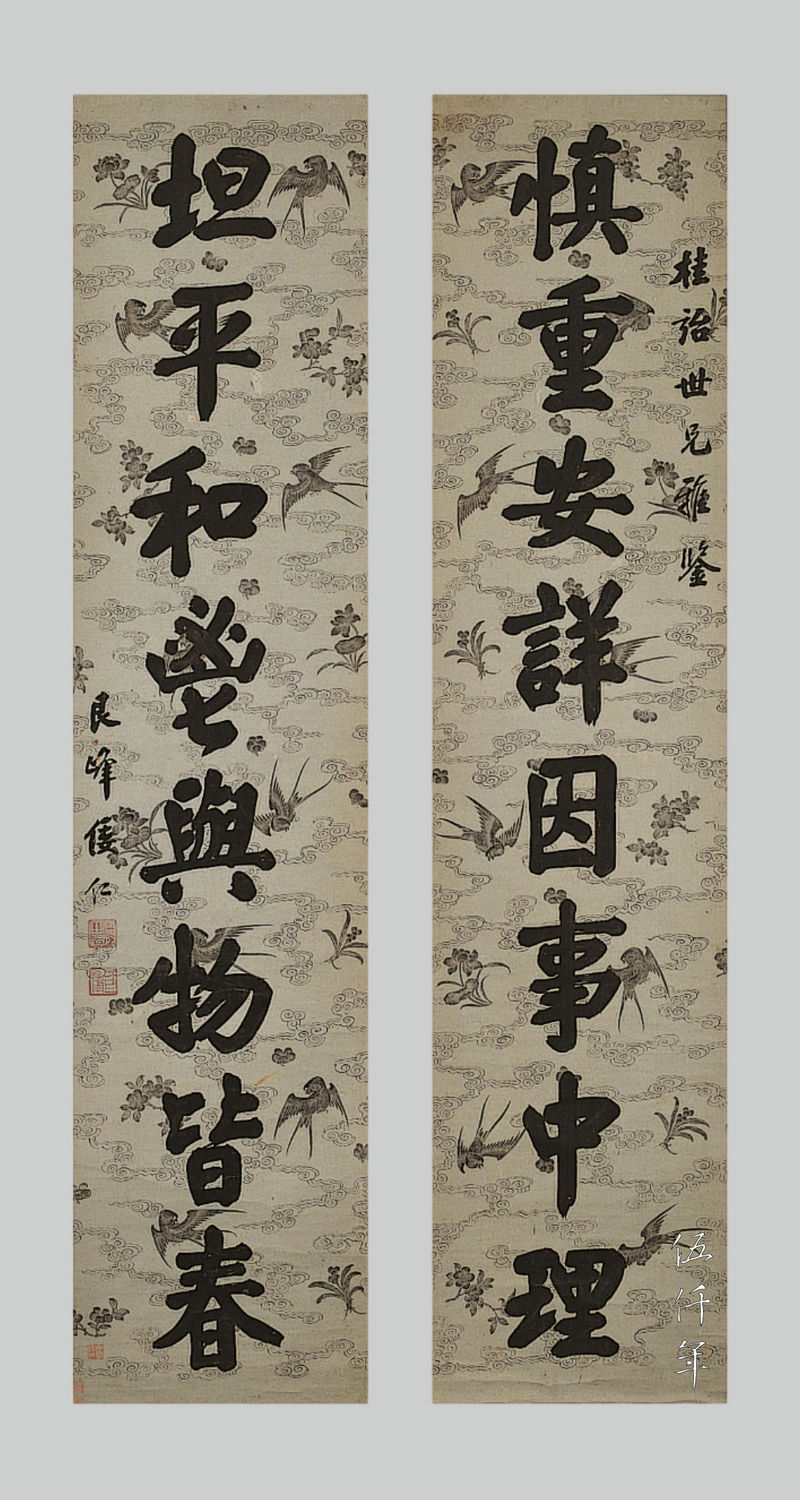

The eminent official and Neo-Confucianist Wo Jen was a friend to two generations of my family. Wo Jen attained the chin-shih degree at the chi-chou year examination in the 9th year of the Tao-kuang reign (1829), he was ranked Second Class Number Thirty Four. My third-great-grandfather Mr. Soong Ping-yüan, also known as Yüeh-ch’iao, attained the chin-shih degree in the same examination, he was ranked Second Class Number One Hundred and Three. According to the poem Views in the Capital City, the horizontal scroll my father saw when he was young was given to Mr. Soong P’ei-ch’u, also known as Ho-fang, when he visited Wo Jen in Peking. After the fall of mainland China to the communists in the 38th year of the Republic (1949), cultural artefacts in our old house were reduced to dust. Around twenty years ago, I acquired a pair of regular script calligraphy couplets by Wo Jen, only to compensate for the lingering pain of the earlier loss. The words are:

Prudence and serenity are apt in matters,

Simplicity and harmony a world in spring.

Inscriptions on the right and left are:

For the refined perusal of my family friend Kuei-i (桂詒),

Ken-feng (艮峰), Wo Jen.

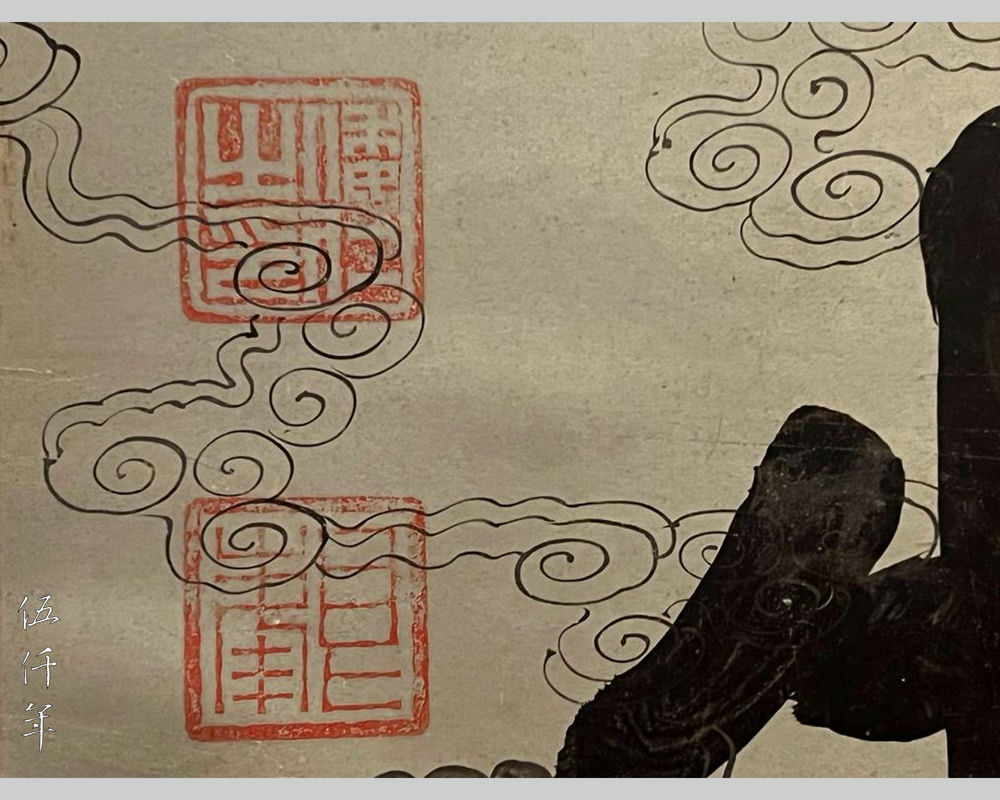

Seal impressions: “The seal of Wo Jen” and “Ken-feng”

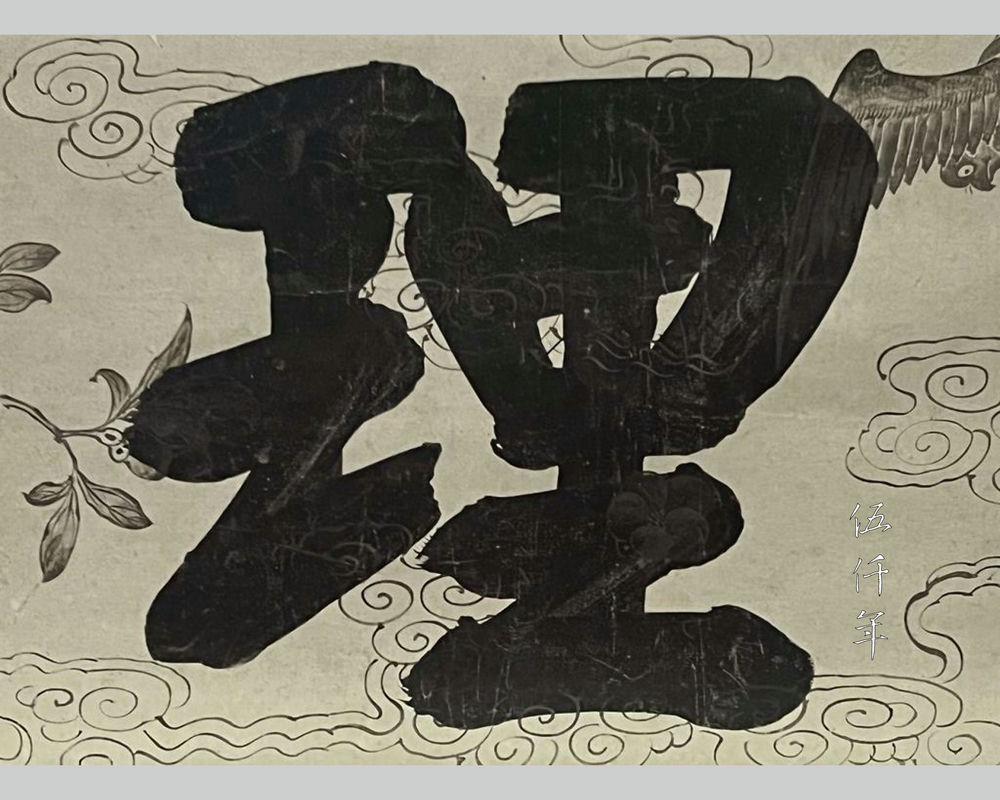

A pair of regular script calligraphy couplets by Wo Jen

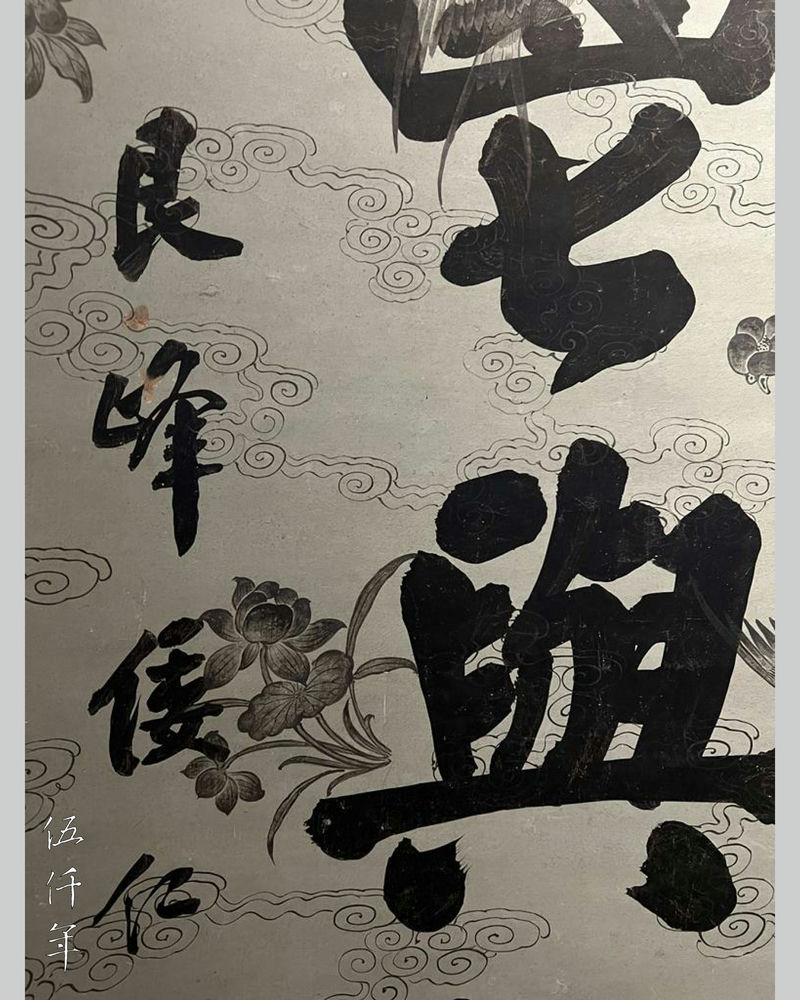

Detail of calligraphy couplet by Wo Jen

Detail of calligraphy couplet by Wo Jen

Detail of calligraphy couplet by Wo Jen

Wo Jen (1804-1871), tzu Ken-feng (艮峰), Ken-chai (艮齋). His original surname was Wu-ch’i-ko-li (烏齊格里), a Mongol of the Plain Red Banner born in Hunan Province. He attained the chin-shih degree in the 9th year of the Tao-kuang reign (1829). In the 13th year (1833) he was promoted to academician expositor-in-waiting of the Hanlin Academy, in the 14th year (1834) he was appointed auxiliary academician of the Hall of Literary Profundity. In the following year, he was associate examining official of the Provincial Examination in Shun-t’ien, Chihli Province. In the 17th year (1837) he was principal examiner of the Provincial Examination in Fukien Province, in the 18th year (1838) he was again auxiliary academician of the Hall of Literary Profundity. In the 22nd year (1842) he was supervisor of the Household Administration of the Heir Apparent, in the 24th year (1844) he was chief minister of the Court of Judicial Review, in the 26th year (1846) he was grand minister examiner of the Han History Examination, in the 27th year (1847) he was examination official of the Military Hall Examination, in the 30th year (1850) he was deputy commander-in-chief and grand minister assistant administrator of Yarkent Khanate.

In the 5th year of the Hsieh-feng reign (1855), he was appointed academician expositor-in-waiting of the Hanlin Academy. In the following year, he was attendant gentleman of the Ministry of Rites in Shen-yang, Liaoning Province. In the 8th year (1858), he was vice commander-in-chief of Shen-yang, Liaoning Province, as well as expectant commander-in-chief of the Mongol White Banner. In the 11th year (1861), he was appointed envoy to Korea.

In the 1st year of the T’ung-chih reign (1862), he was promoted to minister of the Ministry of Works, tutor to the Emperor and chancellor of the Hanlin Academy. In the 2nd year (1863), he was chief superintendent of the Institute for the Veneration of Literature, in the 4th year (1865), he was instructor and grand minister examiner of the Directorate of Education Examination. In the following year, he was grand minister examiner of the Han History Examination. In the 6th year (1867), he was concurrent assistant director of the Hall of Literary Profundity and director-general of the Historiography Institute. In the 9th year (1870), he was principal examiner of the Provincial Examination in Shun-t’ien, Chihli Province. In the 10th year (1871), he was grand academician of the Hall of Literary Glory. In that year Wo Jen passed away. He was posthumously awarded the rank of Grand Guardian and canonized as Wen-tuan (文端).

Portrait of T’ung-chih Emperor

When Wo Jen was appointed tutor to T’ung-chih Emperor (同治皇帝) in 1862, he was already an eminent Neo-Confucianist. His scholarship strove for implementation, he reproached himself for faults, his words and actions were never fatuous, and he faithfully followed the Neo-Confucian School of Ch’eng and Chu (Ch’eng Hao 程顥 1032-1085 and Ch’eng I 程頤 1033-1107 of the Northern Sung dynasty; Chu Hsi 朱熹 1130-1200 of the Southern Sung dynasty). Wo Jen was greatly appreciated by Dowager Empress Tz’u-an (慈安 1837-1881) and Dowager Empress Tz’u-hsi (慈禧 1835-1908). In The Draft History of Ch’ing (清史稿), Wo Jen’s tutorship is described in these words:

“The two Dowager Empresses considered Wo Jen to be sagacious, dignified and vigilant. His scholarship was first-rate and exceptional. He was instructed to be the tutor to Mu-tsung (穆宗 T’ung-chih Emperor). Wo Jen compiled the deeds of the ancient Emperors and the memorials of distinguished officials throughout history. He supplemented them with his commentaries. He presented them to the Emperor, and it was decreed the title Ch’i-hsin chin-chien (Golden Mirror for Instruction of the Heart 啟心金鑑). It was deposited in Hung-te Hall, the Emperor’s study, as teaching material. Wo Jen was always stern and upright. T’ung-chih Emperor was particularly in awe of him.”

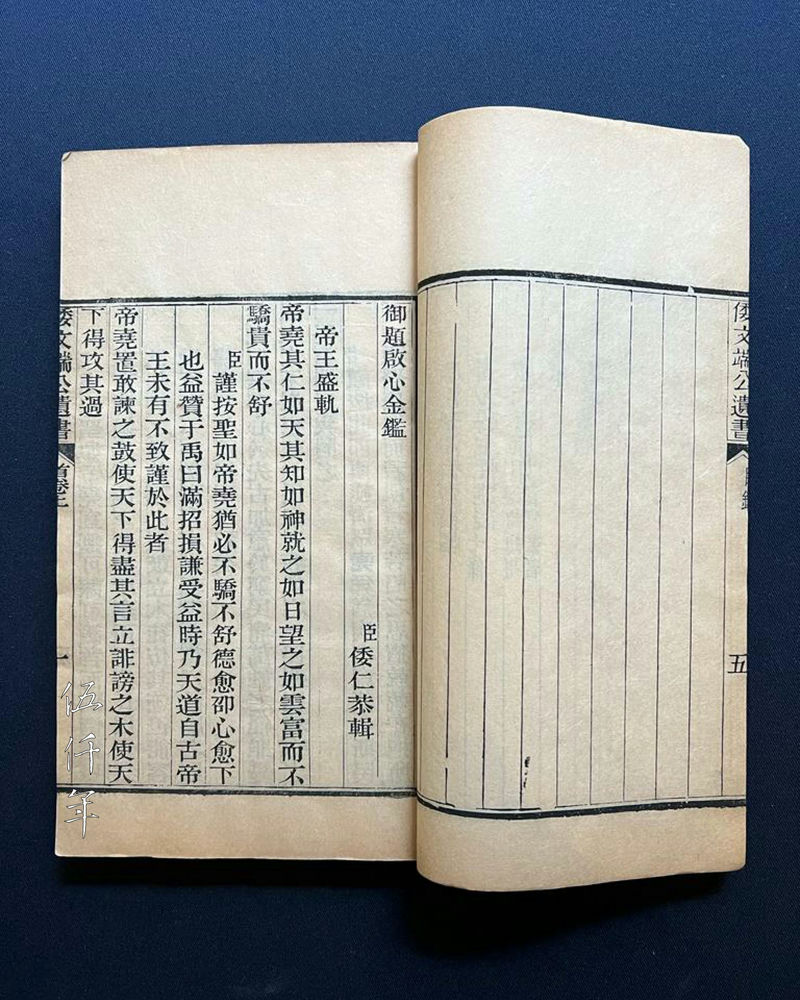

First page of Golden Mirror for Instruction of the Heart by Wo Jen

Concluding paragraph in Golden Mirror for Instruction of the Heart by Wo Jen

After his appointment as tutor to the Emperor, Wo Jen compiled the Golden Mirror for Instruction of the Heart. It expounded the directions of Confucian governance and the principles of self-cultivation for the emperors. The last paragraph of the “Lecture Notes” by Wo Jen is especially instructive for those in government, no matter from which country or race in the world. His words are:

“Mencius denounced the idea of profit (利) and claimed it was wrong. Instead, Benevolence (仁) and Righteousness (義) are principles to save the world forever. By the time of the Warring States period (476 BC-221 BC), the way of Benevolence and Righteousness had crumbled. Contemporary rhetoricians all pressed forward to counsel the theory that efforts should be expended for the sake of profit, and most Kings believed and relished it. Hence after Mencius arrived, King Hui of Liang asked for counsel to profit his kingdom. It is only self serving for the King to seek profit for his kingdom. When the King wishes to benefit himself, and everyone wishes to benefit oneself too. The trend to fight and compete thus begins, and words are not enough to describe the coming catastrophe. Mencius said:

Why must your Majesty use that word ‘profit’?

He asserted that the word ‘profit’ should certainly not be invoked. He then said:

What I am “likewise” provided with, are counsels to benevolence and righteousness, and these are my only topics.

Benevolence is derived from the love for others. It can embrace and safeguard the Four Seas. Righteousness is employed to deal with matters. It can manage and govern all human affairs. If profit is not mentioned, naturally nothing is deemed unprofitable. There is no other satisfactory way. At a time when human greed is overflowing in our world, most people will find the theory of Benevolence and Righteousness anachronistic, and they will discredit them. People do not understand that the placid path does not exist outside the Confucian Way, there are only thorn filled paths; effort for the sake of profit does not exist outside Benevolence and Righteousness, there are only catastrophes. During the three dynasties of Hsia (夏朝), Shang (商朝) and Chou (周朝), the mind was upright, the custom was modest, governance was invigorated at the top, education was implemented from below, this was due to Benevolence and Righteousness. In later dynasties, governance became atrocious; human minds became unkind; honesty, shamefulness and the Moral Way disappeared; thieves and bandits increased daily; this was due to profit. Without exception, this is the cause of stability and chaos since the beginning of history. Mencius discussed this back and forth in seven chapters, they are almost all on this principle. Therefore, Benevolence and Righteousness is the right way to tackle the root and settle the source, to turn back the world of chaos. Which direction should those in government follow? I hope they will think hard and be discerning.”

Mu-tsung was enthroned in the 1st year of the T’ung-chih reign (1862), he was only six years old. Wo Jen was then fifty eight. Thirteen years later in 1875, Mu-tsung died. Even if he had attained the profundity of Golden Mirror for Instruction of the Heart, and comprehended the Confucian Way in his lifetime, a death so young terminated all possible aspirations, His life was as ephemeral as a shadow

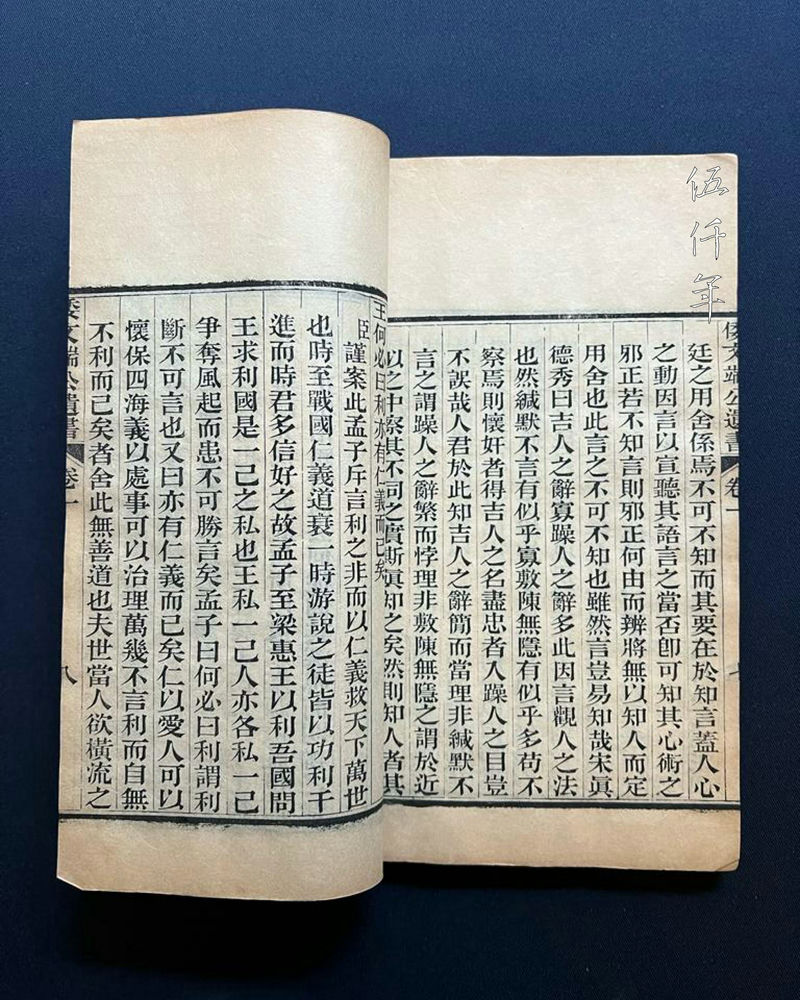

First page of A Memorial in Response to the Emperor’s Decree by Wo Jen

Second page of A Memorial in Response to the Emperor’s Decree by Wo Jen

Inside page of A Memorial in Response to the Emperor’s Decree by Wo Jen

There are many enlightening guidances in the memorials of Wo Jen. In February in the 30th year of the Tao-kuang reign (1850), Wo Jen wrote A Memorial in Response to the Emperor’s Decree. Some words are:

“In administration, nothing is more important than choosing the person for the job. In choosing the person for the job, nothing is more critical than the uncompromising differentiation between those who are virtuous (君子) and those who are mean (小人)…As for the difference between the virtuous and the mean, it is difficult to know concealed designs in the mind, but it is easy to observe revelations from their actions……… Mostly, the virtuous is plain and dull, the mean is flattering and artful. The virtuous is serene and reserved, the mean is impatient and competitive. The virtuous appreciates and values talents, the mean pushes aside those who are different. The virtuous aims for the grand and the long term, his priority is the well-being of the country. The mean calculates the immediate, making the most out of accumulation and callousness. The virtuous is upright and does not bend, he offers no flattery, the mean is flexible in agreement and disagreement, catering to the likes and dislikes of the superior by stepping forward or hiding behind. In court, the virtuous counsels and argues, bolsters and assists, remedies and supplements. The mean accommodates and ingratiates, recommendations are given to cover the faults and extend the pride of the superior. The virtuous advances discussions on worrisome and perilous issues, bringing alarm into the respectful heart of the superior. The mean frequently makes references to destiny, does not worry about great changes and fosters the relaxed outlook of the superior. The public and the private, the villainous and the upright, opposites are usually so.”

In all sectors of society today, if there can be uncompromising differentiation between the virtuous and the mean, with the virtuous promoted and the mean demoted, is it not possible to attain a world of great peace?

Wo Jen was a revered friend of Tseng Kuo-fan (曾國藩 1811-1872). In the section of jen-yin year (壬寅) in Tseng Wen-cheng Kung jih-chi (The Diary of Tseng Kuo-fan 曾文正公日記), he wrote about their friendship. His words on 23 November are:

“I visited the place of my elder friend Ken-feng (Wo Jen) to deliver my Notebook of Daily Lessons. I implored him to instruct and rectify it. His appearance was disciplined, serious and serene. I know he keeps rejuvenating his spirit daily.”

Tseng Kuo-fan wrote on 26 November:

“I came back and received my copy of the Notebook of Daily Lessons from my elder friend Ken-feng (Wo Jen). He had inscribed some commentaries in the Notebook. I was alarmed and perspired while reading it. I was taught to clear everything and to begin anew as a person. How fortunate it is for me to receive his words that are akin to medicine. Reading the Notebook of Daily Lessons by Ken-feng himself, always brings a sense of caution and alarm. It is altogether contrary to me, with my idleness, and indifference to vigilance and trepidation.”

Jen-yin year was the 22nd year of the Tao-kuang reign (1842). Tseng Kuo-fan was thirty one years old and was appointed assistant editor of the Historiography Institute. He resided in Peking and dedicated to studying the teachings of the Neo-Confucian School of Ch’eng and Chu. Each day he practiced self-denial in the pursuit of scholarship, he committed to correct his faults, and he chronicled these in what he called Notebook of Daily Lessons. He devised twelve articles for his daily lesson as rules to improve himself.

1. Be respectful

2. To meditate

3. To rise early

4. To study

5. To read history

6. To be careful with words

7. To cultivate the energy of life

8. To preserve health

9. To learn something new each day

10. To remember what is learned each month

11. To write

12. Do not go out in the evening

At the time Wo Jen was thirty eight years old. His position in Peking was supervisor of the Household Administration of the Heir Apparent. Both men were dedicated to the Neo-Confucian School of Ch’eng and Chu. They saw each other regularly, writing their respective Notebook of Daily Lessons, and exchanging their views on Neo-Confucianism.

On 26 October in jen-yin year (1842), Tseng Kuo-fan wrote a letter to his brothers. Part of it reads:

“Mr. Wo Ken-feng adheres to a strict discipline to practice sincerity. Every day he writes in a Notebook of Daily Lessons. Within each day, he records each misstep in his thinking, misstep in his work, word or silence, in a Notebook. He writes in regular script. Every three months, he produces a volume. Starting from i-wei year (乙未), there are already thirty volumes. He is unyielding in maintaining mental discipline over his private life. Whenever an inappropriate thought occasionally surfaces, he immediately overcomes it with a cure, and he writes it in the Notebook. Therefore, in these Notebooks that he has worked hard on, each sentence is a remedy for self-improvement. I have copied three pages from the Notebook of Daily Lessons by Mr. Ken-feng, I hereby attach them with this letter for your perusal.

From 1 October, I have started to emulate Ken-feng in writing down each thought and each matter in the Notebook, so that I can remedy my faults by quickly reading about them. I now write in regular script too.”

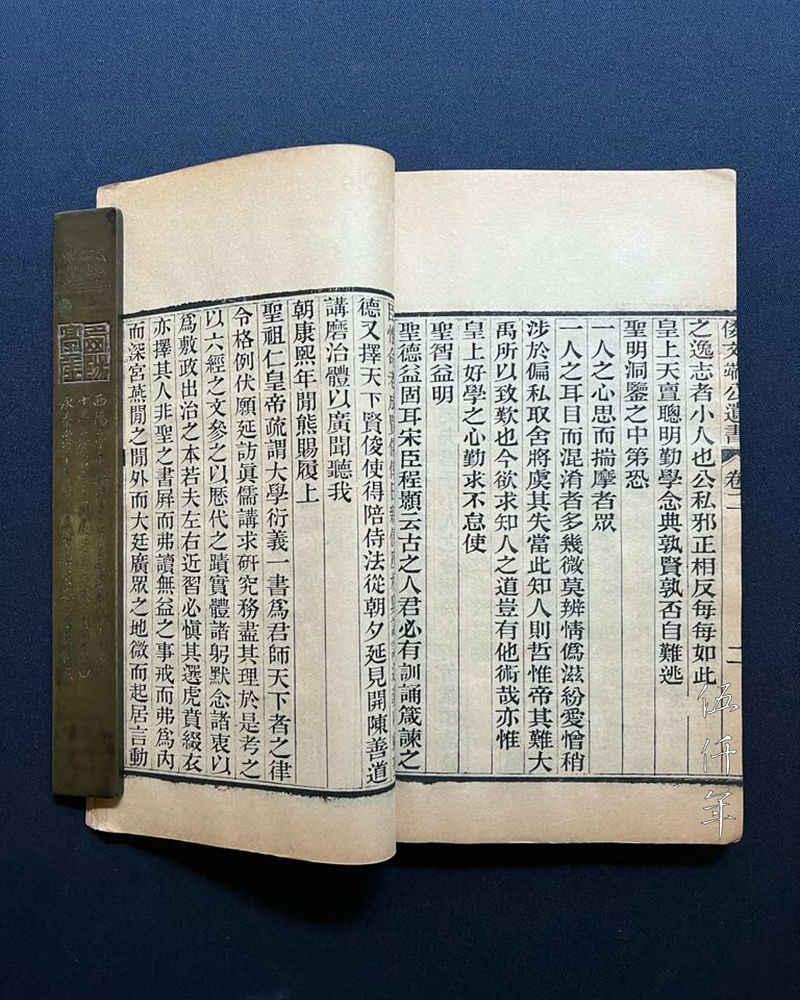

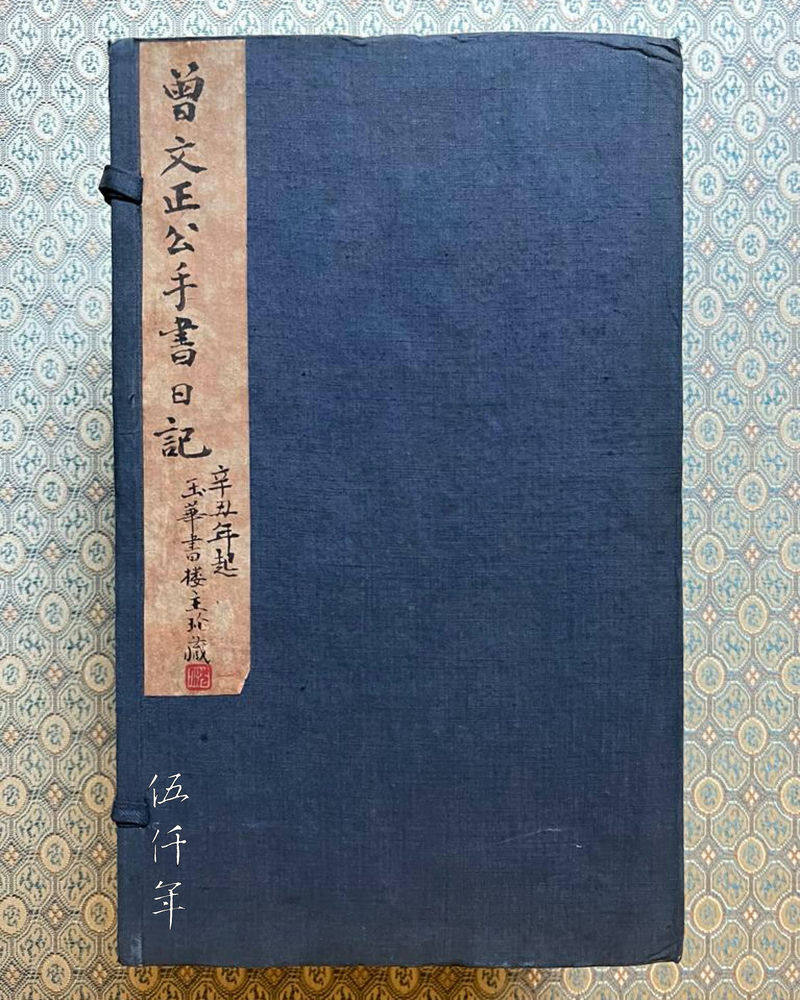

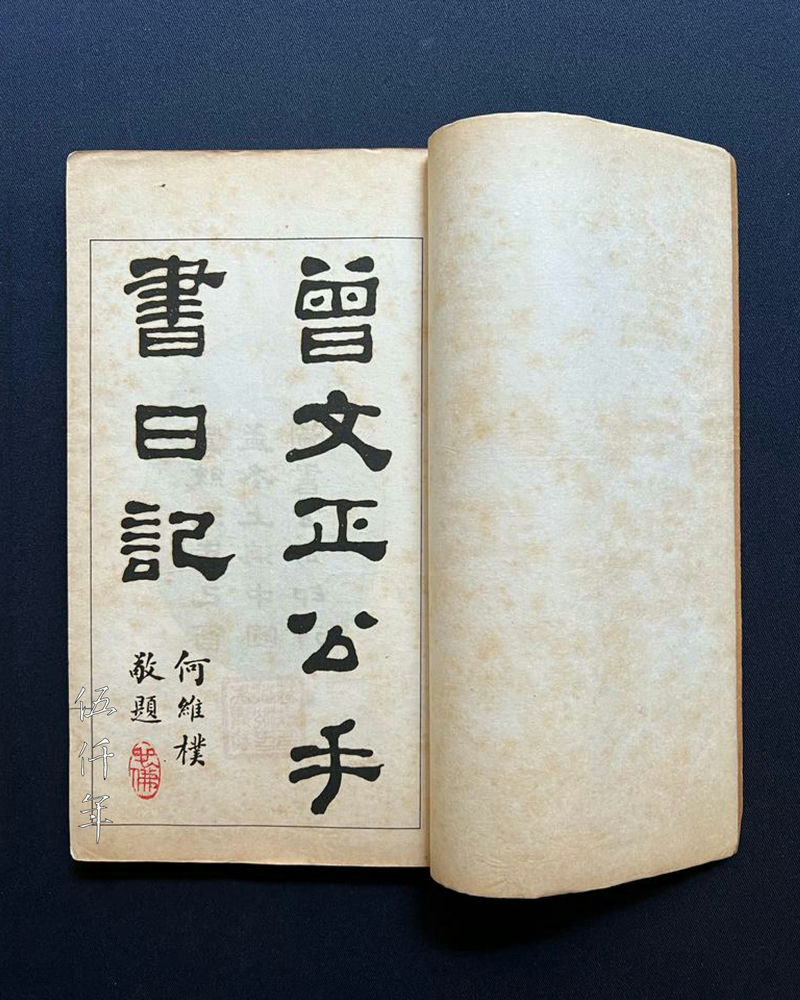

Front of cover slip of The Diary of Tseng Kuo-fan

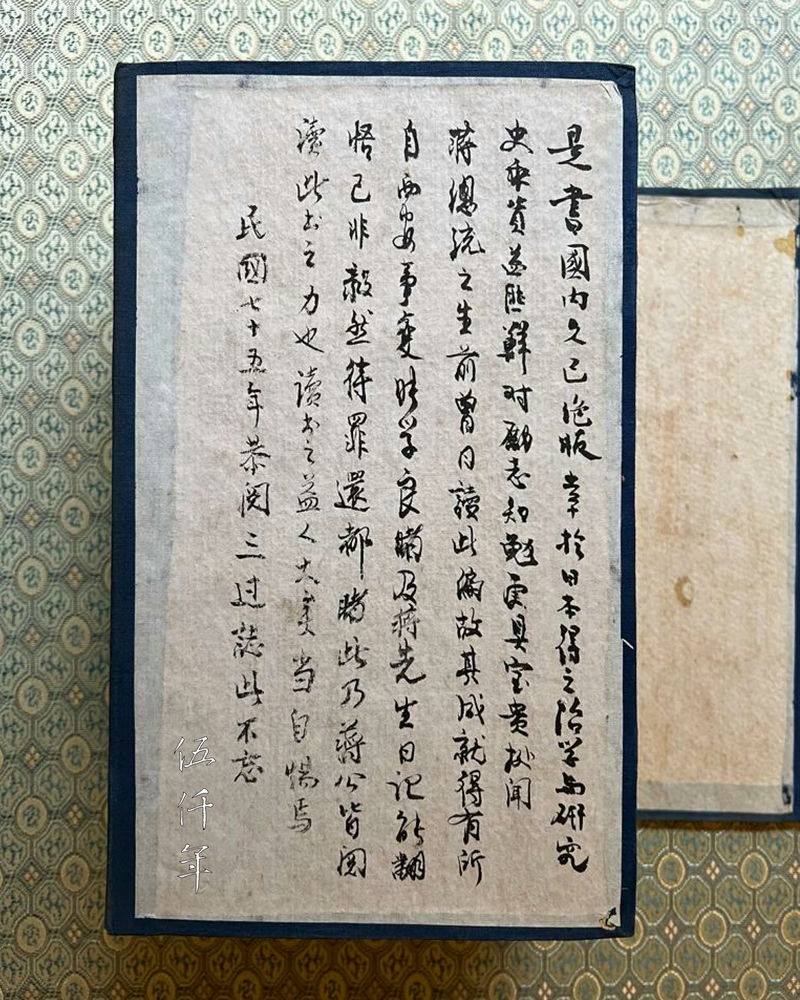

Inscription inside cover slip of The Diary of Tseng Kuo-fan

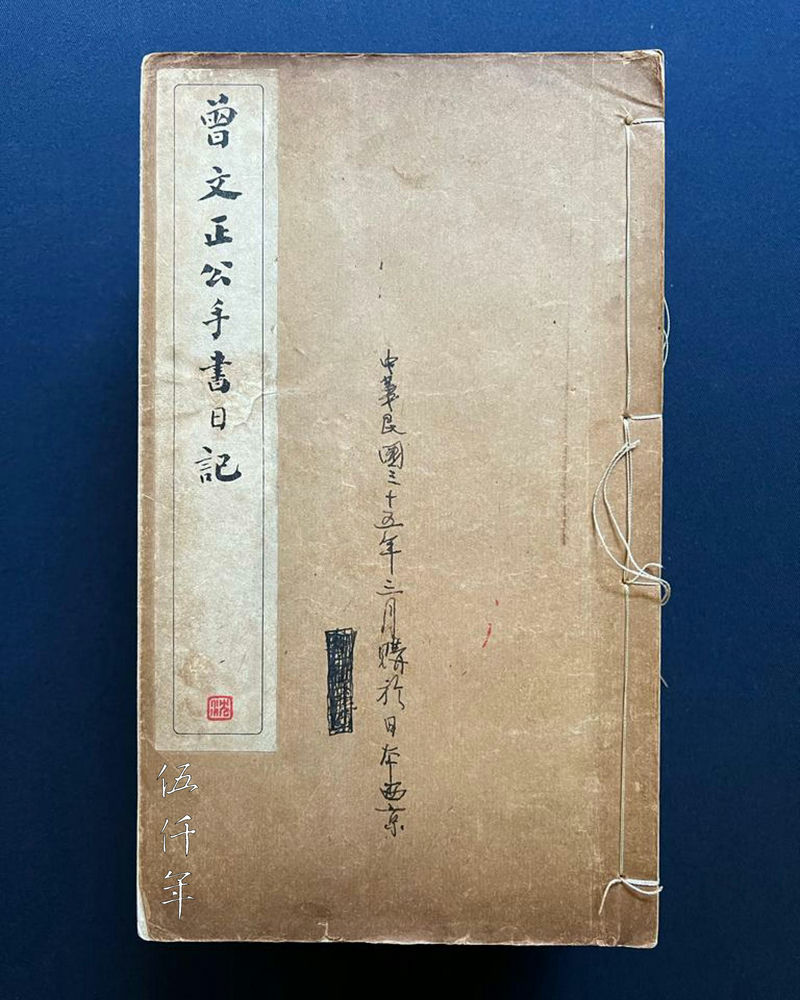

Front cover of first volume of The Diary of Tseng Kuo-fan

Title page of first volume of The Diary of Tseng Kuo-fan

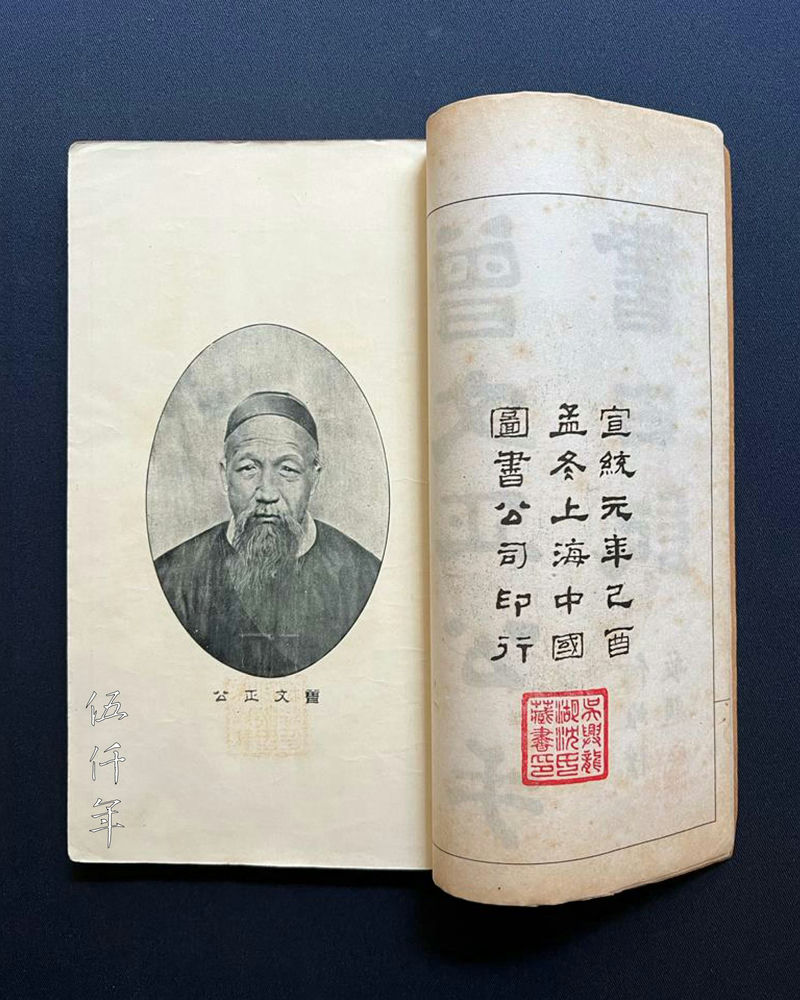

Portrait of Tseng Kuo-fan in The Diary of Tseng Kuo-fan

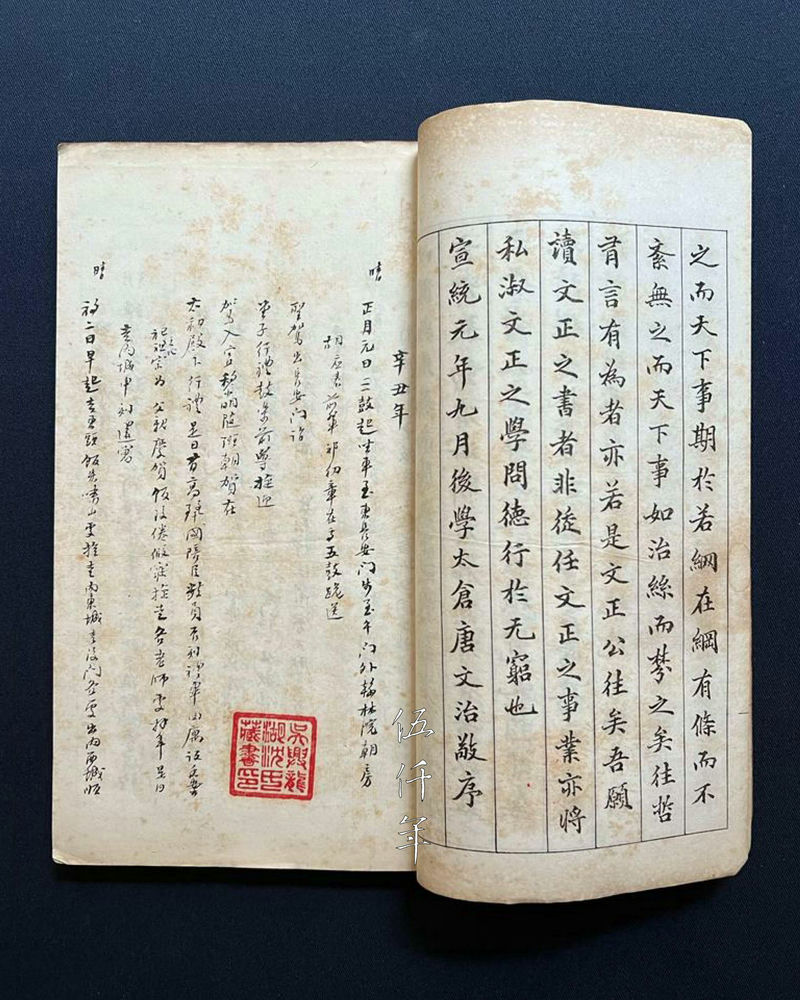

First page of hsin-ch’ou year (1841) diary in cursive and running scripts

Tseng Kuo-fan wrote the complete set of his Diary in cursive and running scripts. However, between 1 October to 29 December in jen-yin year, he wrote in regular script instead. Due to his great admiration for Wo Jen, he decided to emulate his diary by writing in regular script. Nevertheless Tseng Kuo-fan only managed to maintain this habit for eighty eight days. He eventually gave up writing in the far more laborious regular script and reverted to writing in running and cursive scripts. Even a man as virtuous as Tseng Kuo-fan, could not execute and complete each matter from beginning to end.

Second page of hsin-ch’ou year (1841) diary in cursive and running scripts

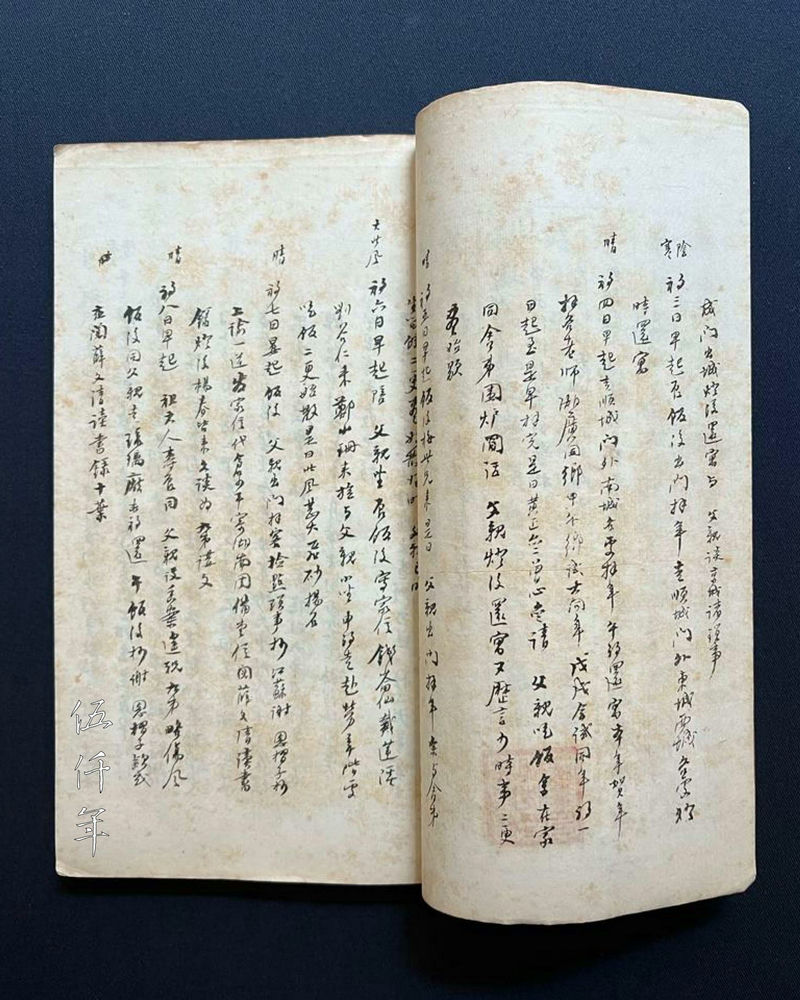

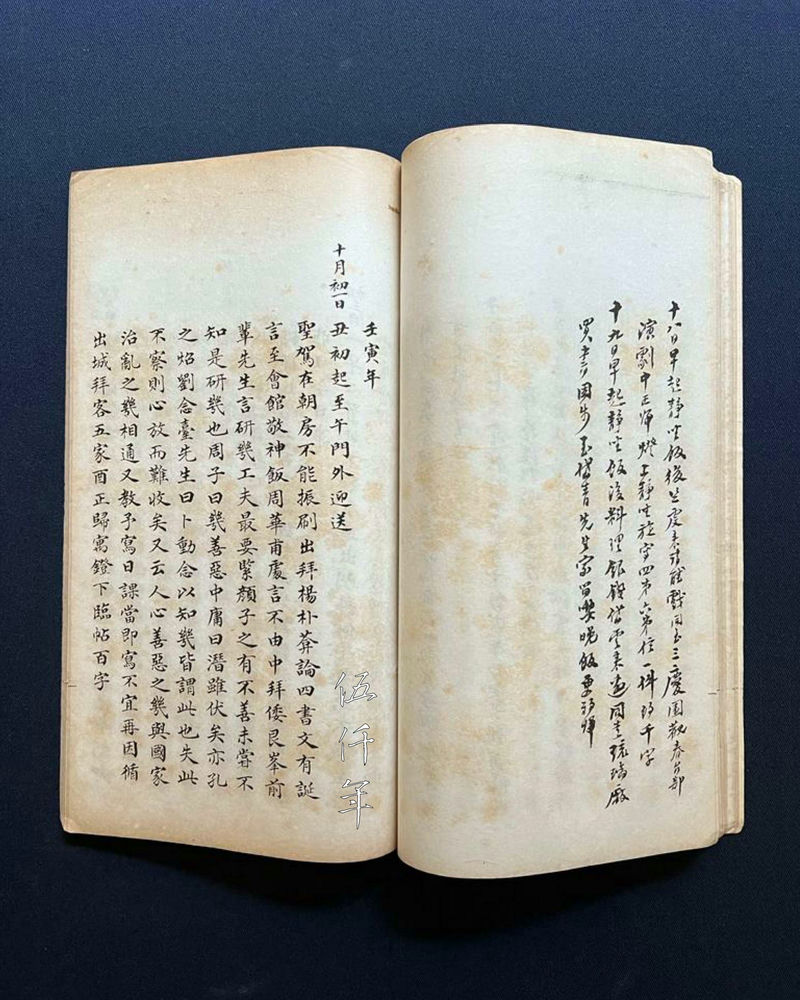

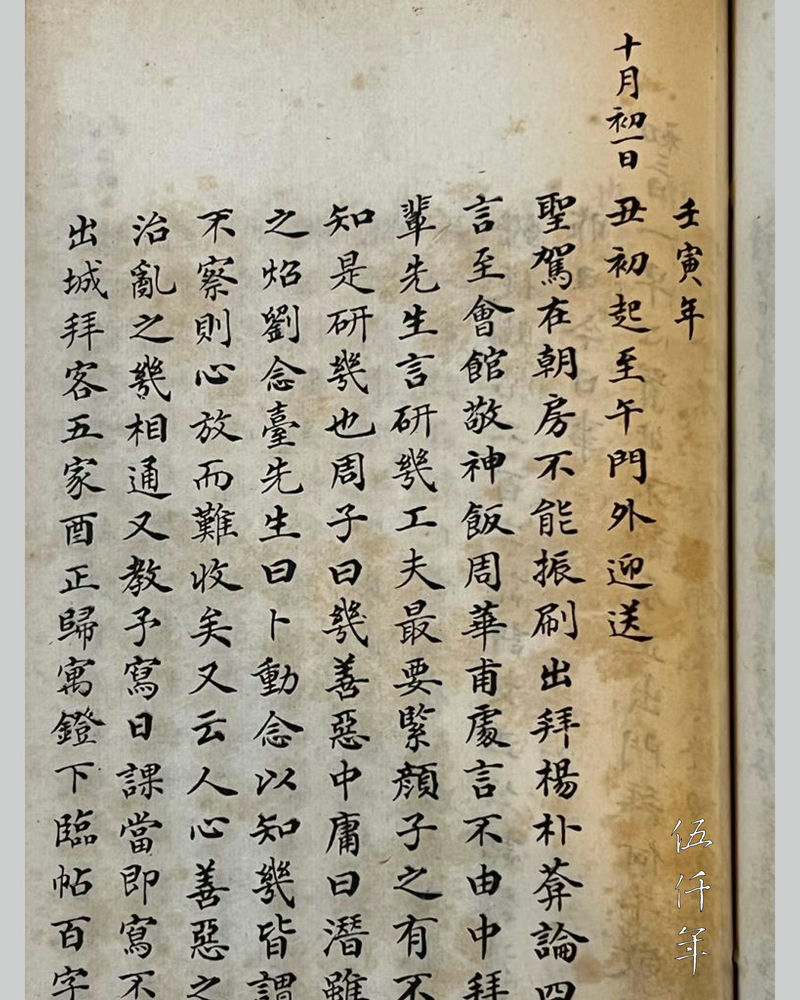

First page of October jen-yin year (1842) diary in regular script

First page detail of October jen-yin year (1842) diary in regular script

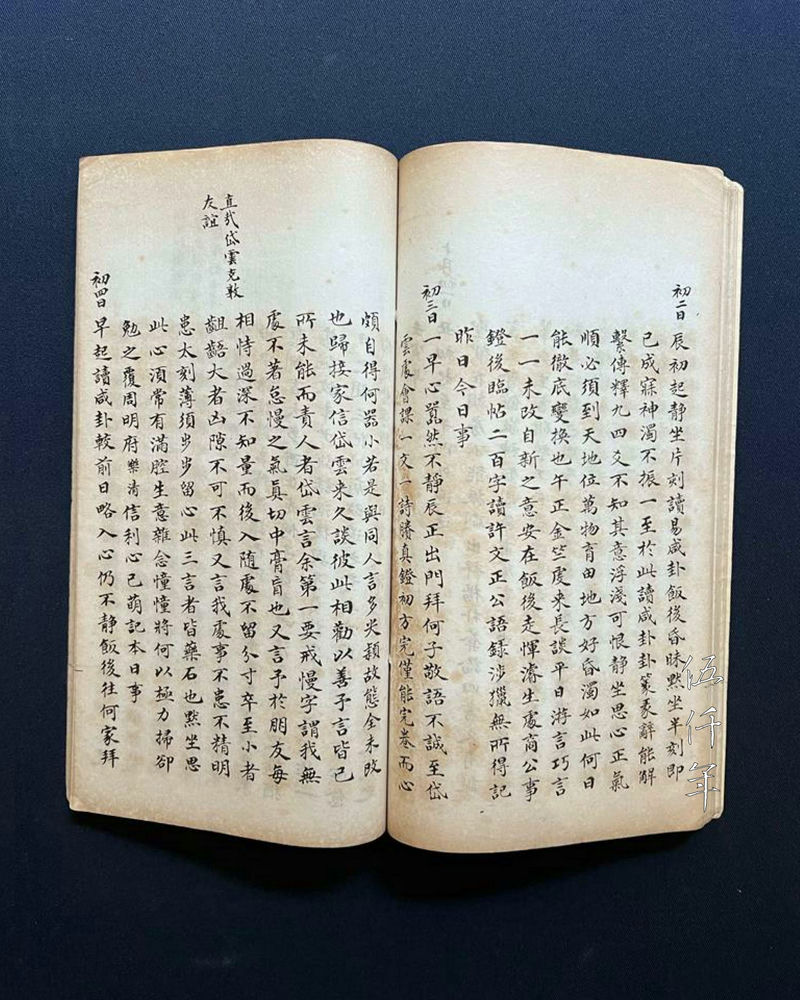

Second page of November jen-yin year (1842) diary in regular script

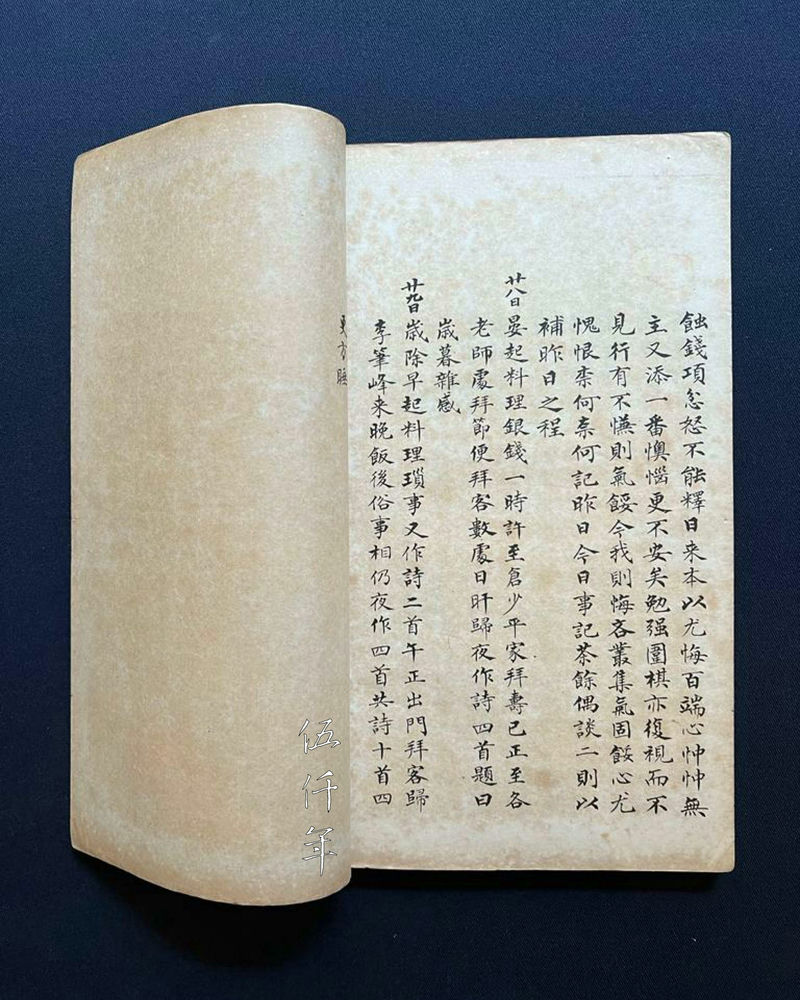

Last page of December jen-yin year (1842) diary in regular script

The Diary of Tseng Kuo-fan was written in cursive and running scripts apart from the section between October to December 1842

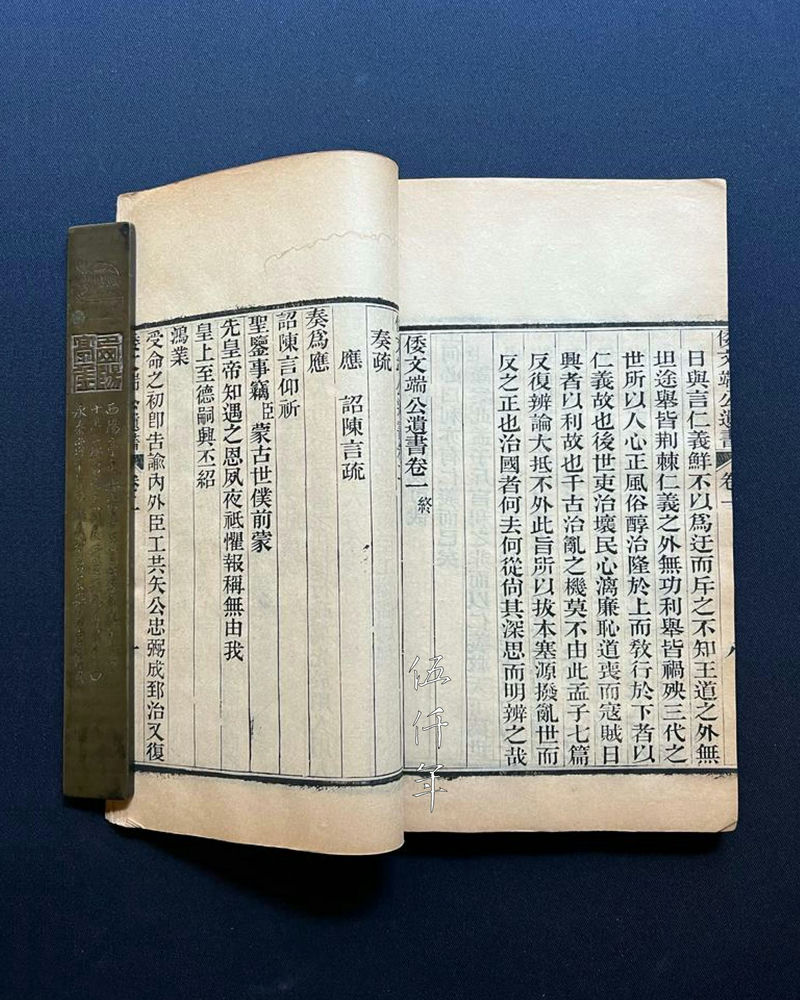

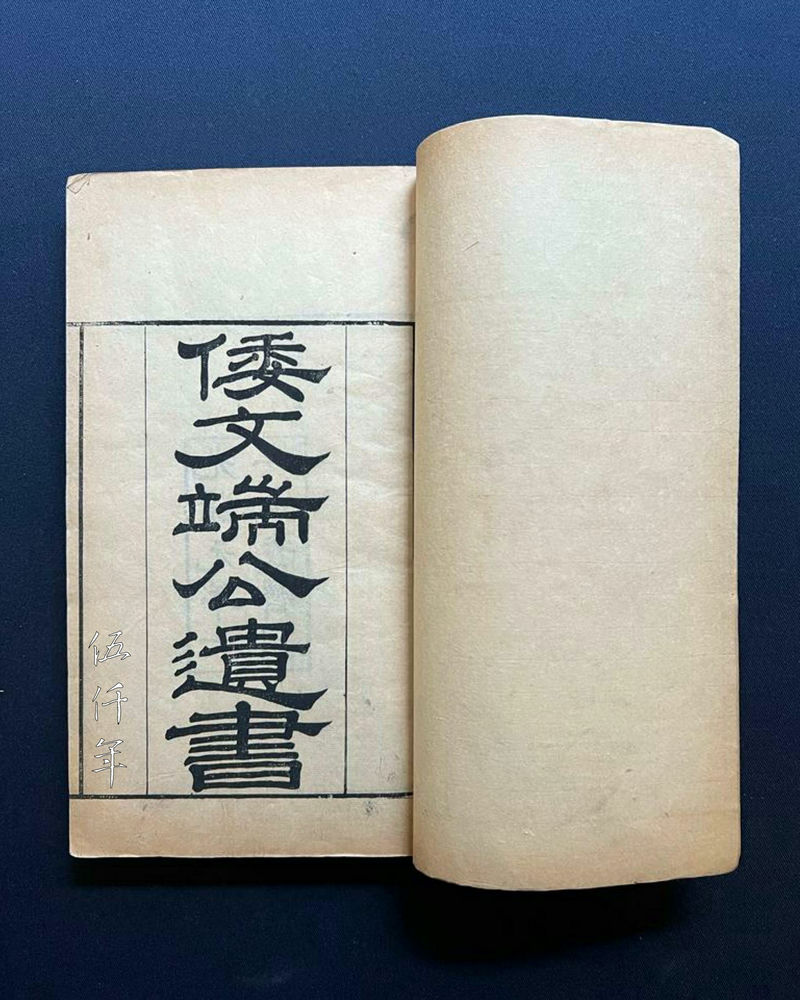

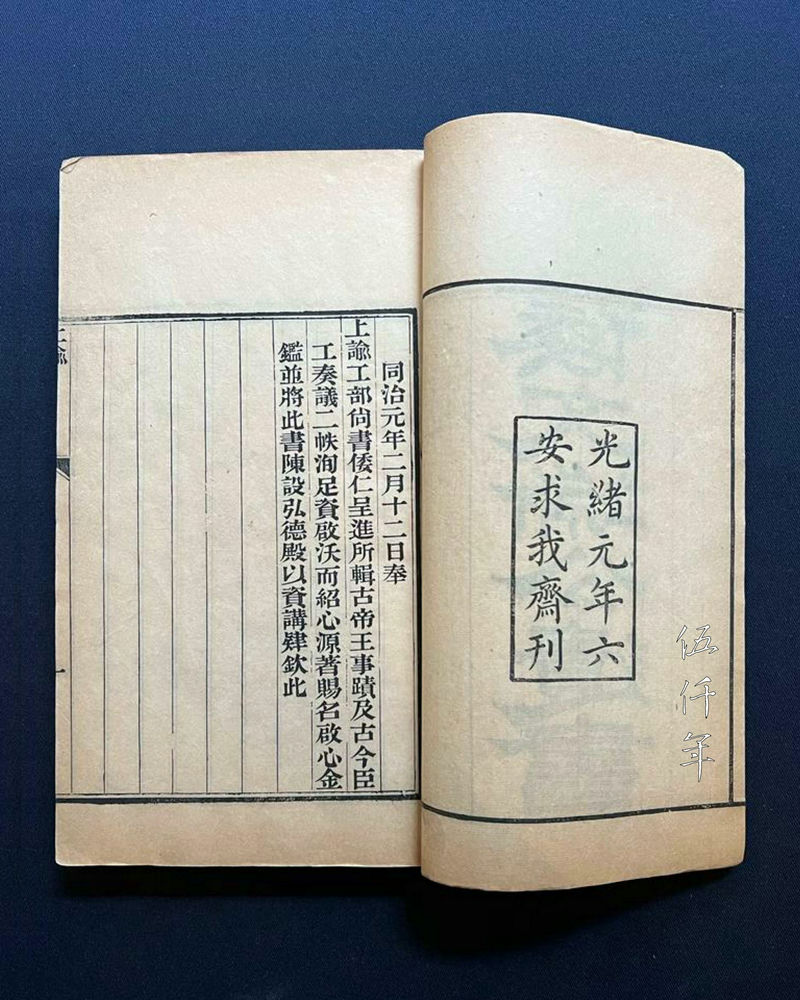

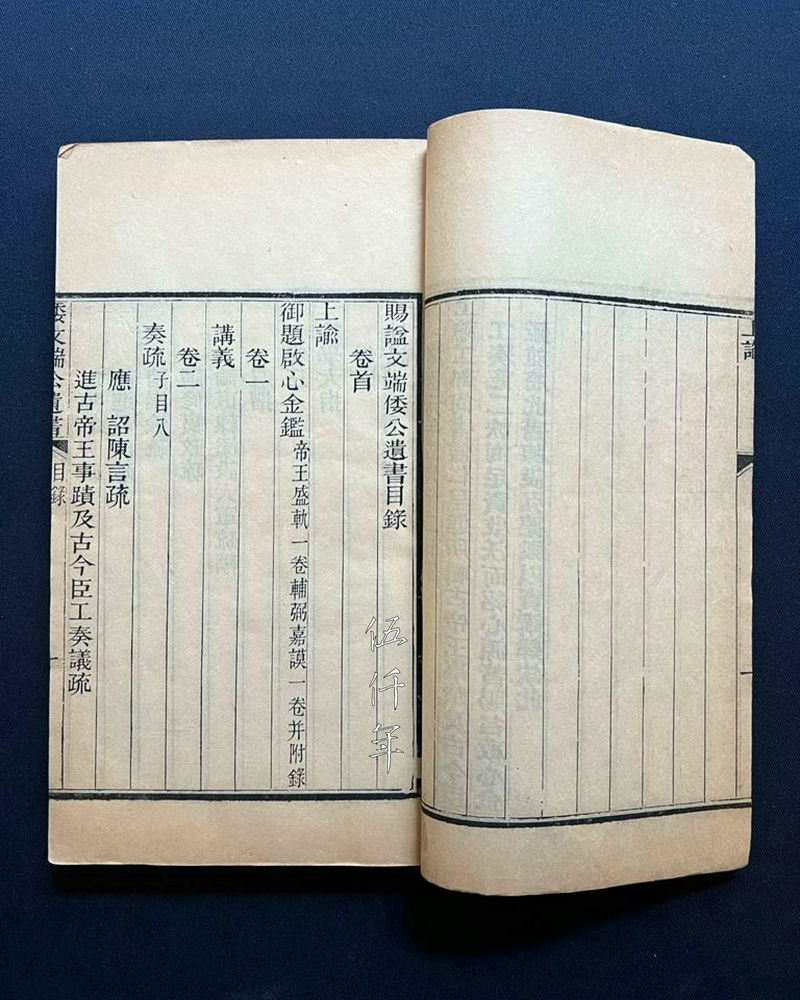

Four years after the death of Wo Jen, in the 1st year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1875), T’u Lang-hsien (涂閬仙) whose studio name was Ch’iu-wo Chai (求我齋) from Liu-an, Anhwei Province, published Wo Wen-tuan Kung i-shu (The Works of Wo Jen 倭文端公遺書). The contents are organized as follows:

Volume One: Teachings

Volume Two: Memorials

Volume Three: Principles of Scholarship

Volume Four: Diaries After Ping-wu Year (丙午) of the Tao-kuang Reign

Volume Five: Diaries After Keng-hsü Year (庚戌) of the Tao-kuang Reign

Volume Six: Diaries After Jen-tzu Year (壬子) of the Hsien-feng Reign

Volume Seven: Remnants of Diaries

Volume Eight: Miscellaneous

Last Volume: Essentials of Governance

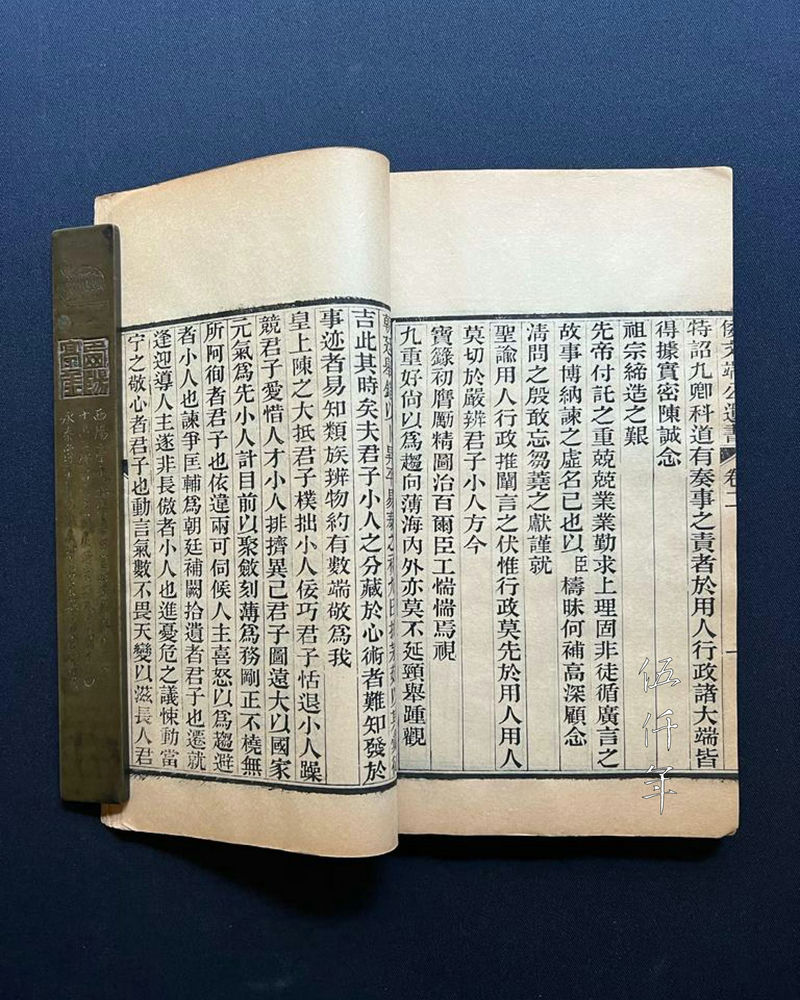

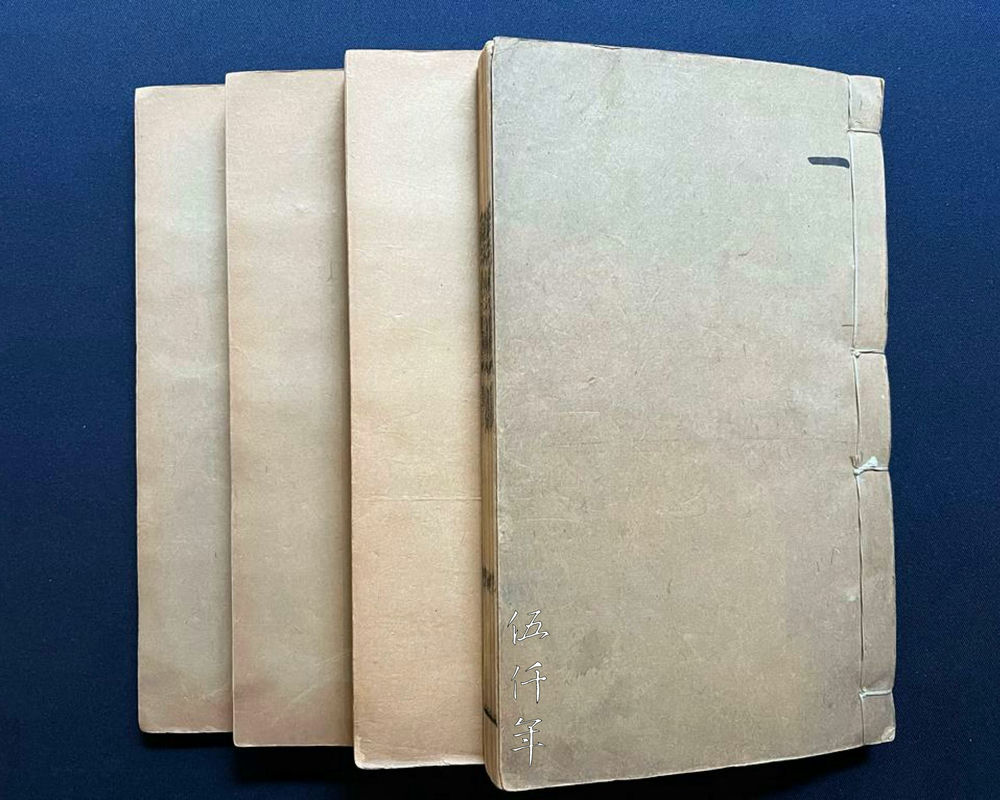

The Works of Wo Jen in four volumes

Title page of The Works of Wo Jen

Inside page of The Works of Wo Jen

Index of The Works of Wo Jen

As for Volume Four: Diaries After Ping-wu Year of the Tao-kuang Reign, ping-wu year is the 26th year of the Tao-kuang reign, these are diaries after 1846, with a total of sixty-four pages.

As for Volume Five: Diaries After Keng-hsü Year of the Tao-kuang reign, keng-hsu year is the 30th year of the Tao-kuang reign, these are diaries after 1850, with a total of forty-three pages.

As for Volume Six: Diaries After Jen-tzu Year of the Hsien-feng Reign, jen-tzu year is the 2nd year of the Hsien-feng reign, these are diaries after 1852, with a total of eighty pages.

As for Volume Seven: Remnants of Diaries, the years are uncertain, with a total of eleven pages.

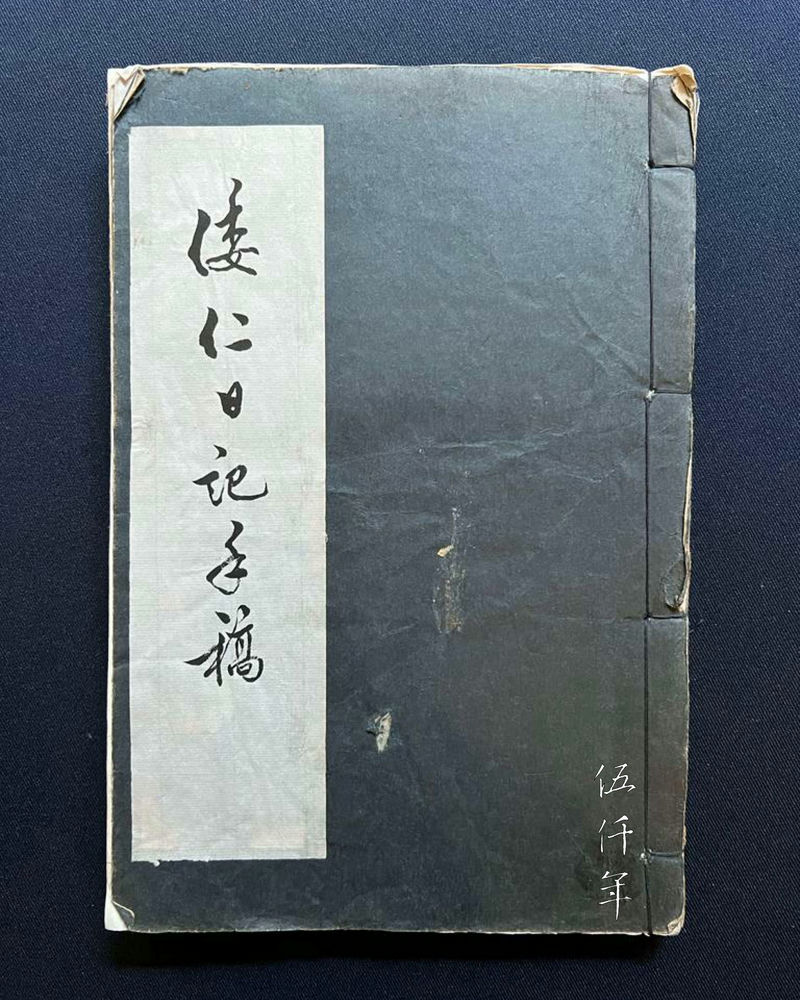

Front cover of Manuscript Diary of Wo Jen

The original front cover of Manuscript Diary of Wo Jen

Inscribed title page of Manuscript Diary of Wo Jen

Inscription by Tou Hsü in Manuscript Diary of Wo Jen

Inscription by Chu Tz’u-ch’i in Manuscript Diary of Wo Jen

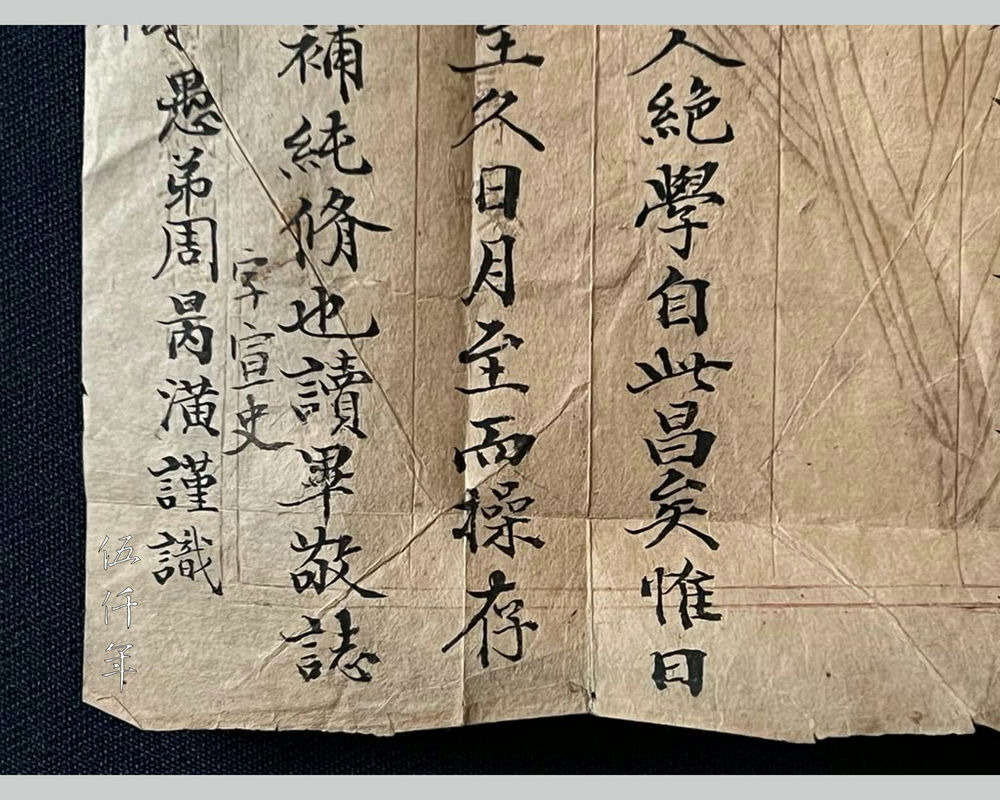

Inscription by Chou Ping-huang in Manuscript Diary of Wo Jen

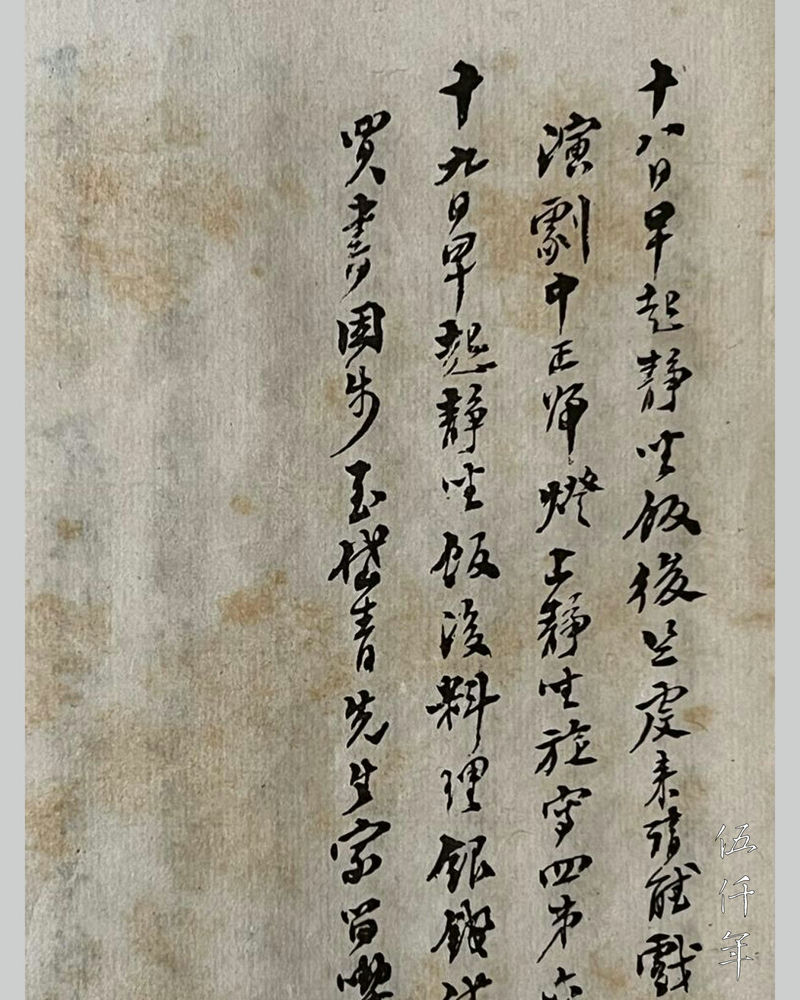

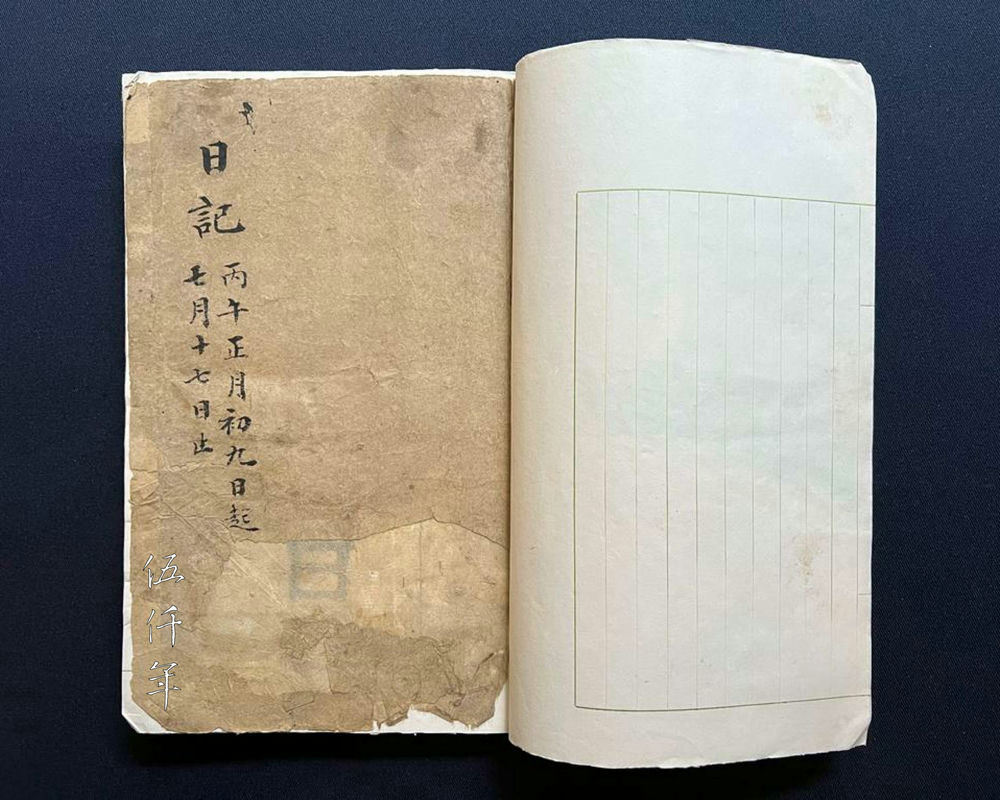

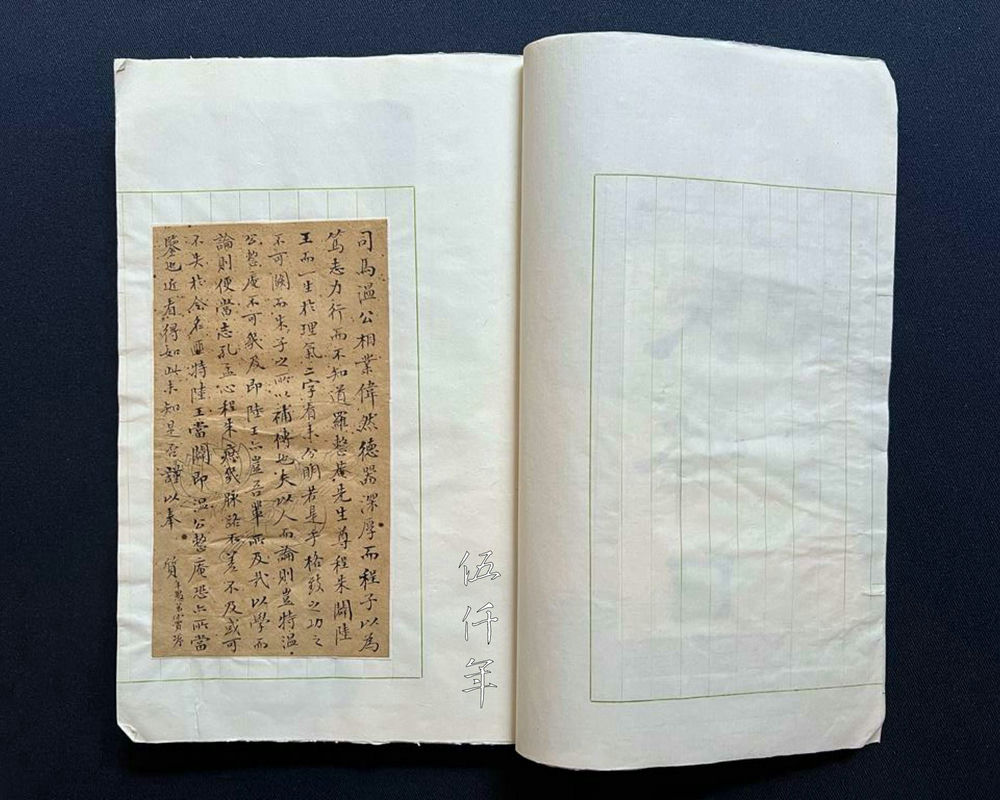

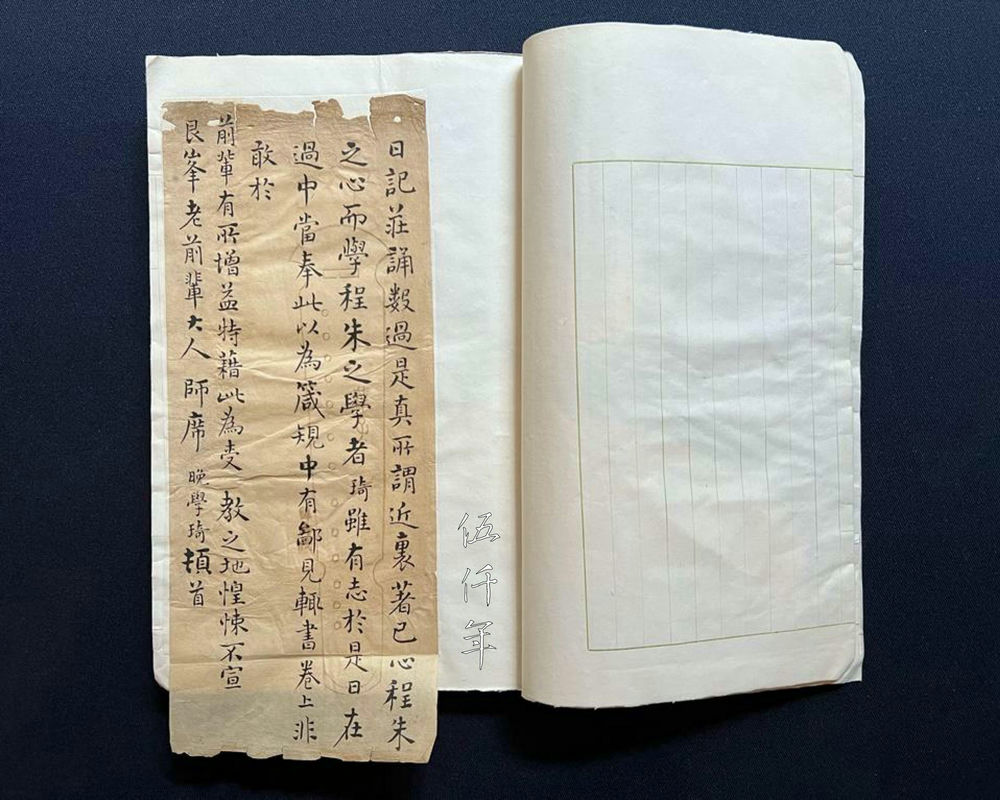

Manuscript Diary of Wo Jen beginning January ping-wu year (1846)

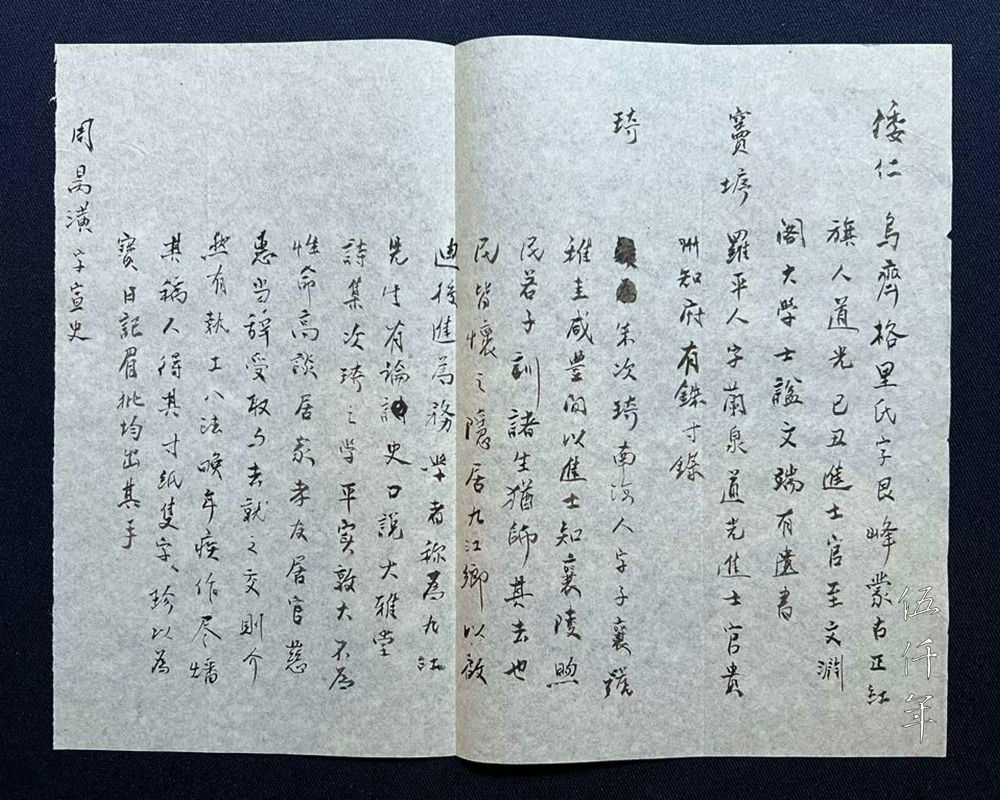

Biographies of Wo Jen, Tou Hsü, Chu Tz’u-ch’i and Chou Ping-huang written on a sheet

In the Studio of Prunus Ode, there is a treasured volume of the Manuscript Diary by Wo Jen. It covers the three months period from 9 January to 17 April in ping-wu year of the Tao-kuang reign (1846). There are inscriptions on the upper pages and paper strips are affixed throughout the Manuscript. Inscriptions after the title page were written by Tou Hsü (竇垿), Chu Tz’u-ch’i (朱次琦) and Chou Ping-huang (周昺潢). There is a sheet with their biographies, the author unknown. According to the inscription by Ch’u Tz’u-ch’i after the title page, inscriptions on the upper pages were also written by him. Inscriptions on the affixed paper strips were written by Tou Hsü and some other friends.

In the letter by Tseng Kuo-fan to his brothers on 26 October in jen-yin year (1842), he described in detail the Notebook of Daily Lessons by Wo Jen. He wrote:

“Every day he writes in a Notebook of Daily Lessons. Within each day, he records each misstep in his thinking, misstep in his work, word or silence, in a Notebook. He writes in regular script. Every three months, he produces a volume. Starting from i-wei year (乙未), there are already thirty volumes.”

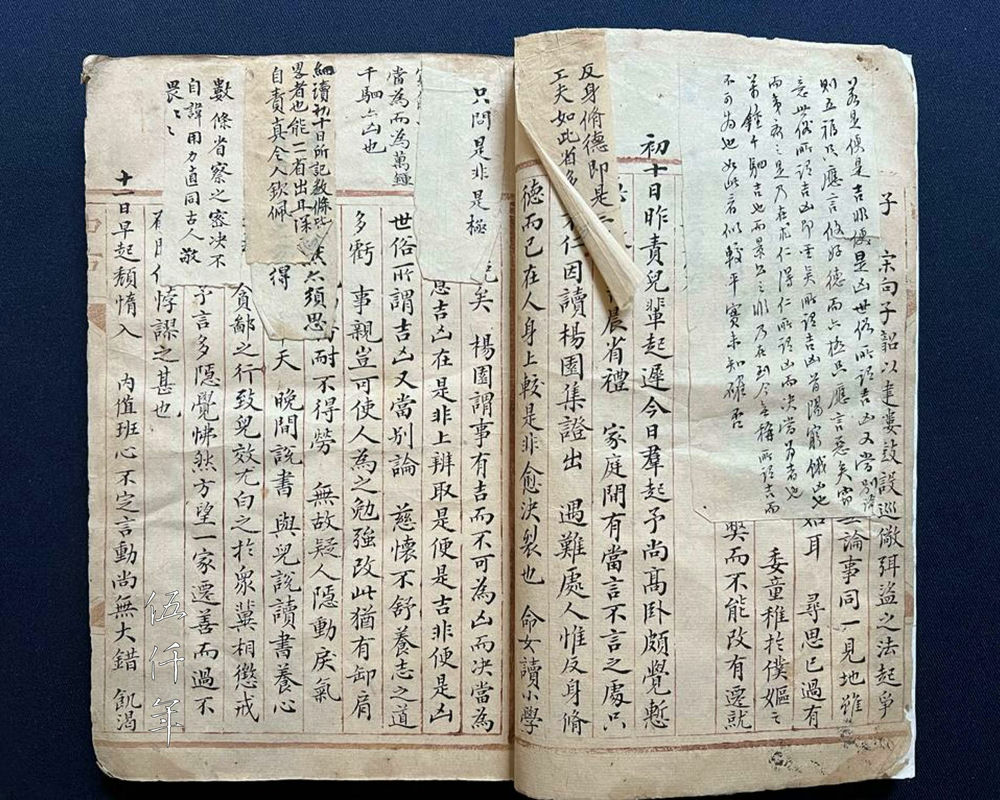

On reading the Manuscript Diary by Wo Jen, I realize that this is a volume of the Notebook of Daily Lessons that covers the period between 9 January to 17 April in ping-wu year. It is one of the many volumes produced every three months. In this volume there are altogether eighty-nine pages with daily entries on his thoughts written in regular script. In the past twenty years, there has not been another volume of the Manuscript Diary by Wo Jen offered in the antiquarian book market. It is likely to be only surviving copy.

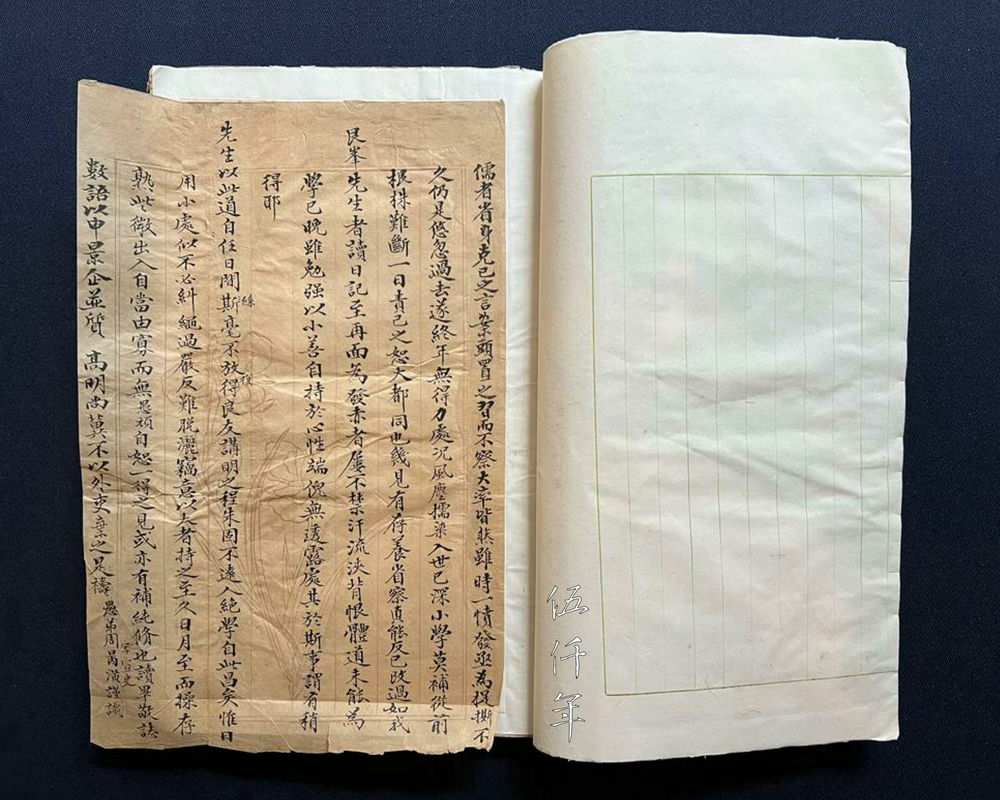

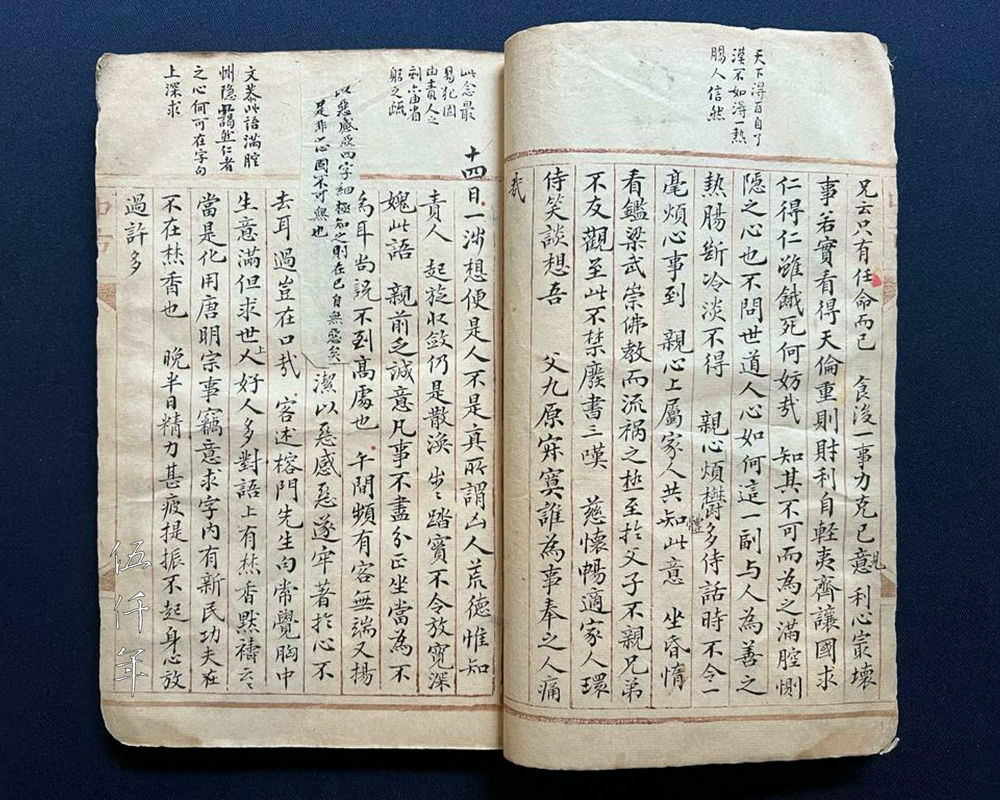

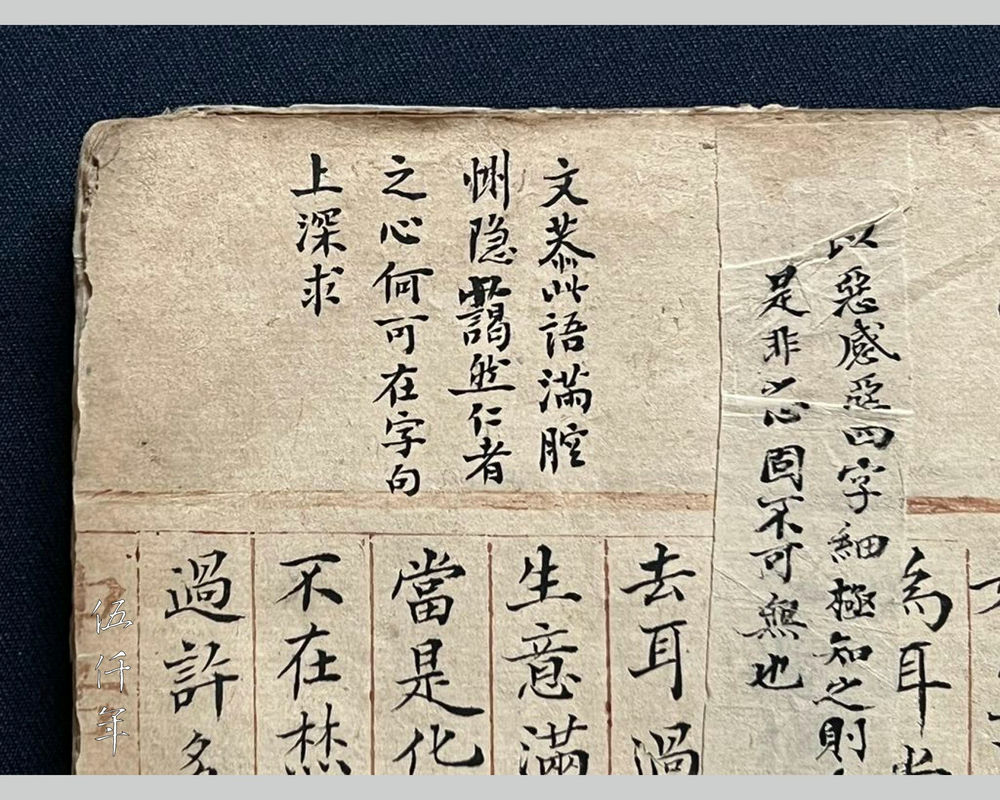

Inside page of Manuscript Diary of Wo Jen

Inside page of Manuscript Diary of Wo Jen

Inside page detail of Manuscript Diary of Wo Jen

Inside page of Manuscript Diary of Wo Jen

Inside page detail of Manuscript Diary of Wo Jen

According to Tseng Kuo-fan, Wo Jen started writing the Notebook of Daily Lessons from i-wei year, the 15th year of the Tao-kuang reign (1835). Yet in The Works of Wo Jen, the diary section begins with Diaries After Ping-wu Year of the Tao-kuang Reign, which is the 26th year of the Tao-kuang reign (1846). Why? Perhaps when T’u Lang-hsien edited and published The Works of Wo Jen under his studio name Ch’iu-wo Chai in the 1st year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1875), the notebooks written between i-wei year and ping-wu year in a span of eleven years and in forty-four volumes no longer existed. They were most likely destroyed during the Taiping Rebellion. In The Works of Wo Jen, the diary section ends with Diaries After Jen-tzu Year of the Hsien-feng Reign, which is the 2nd year of the Hsien-feng reign (1852). The word “after” does not indicate which years are included, nor is it possible to infer. Wo Jen passed away in the 11th year of the T’ung-chih reign (1872). As there are twenty years between the 2nd year of the Hsien-feng reign to the 11th year of the T’ung-chih reign, there should be eighty volumes of the Notebook of Daily Lessons. Even if Wo Jen gave up his habit of writing Notebook of Daily Lessons out of fatigue a few years before his death, the number of volumes should still be substantial. However, there are only eighty meagre pages in Volume Six: Diary from Jen-tzu Year of the Hsien-feng Reign.

When T’u Lang-hsien edited The Works of Wo Jen for publication, in the diary section between Volume Four and Volume Seven, he only extracted some selected paragraphs regarding self-cultivation and scholarship, together with a number of inscriptions on the upper pages and the affixed paper strips by Hui Shan (惠善), Tou Hsü (竇垿), Wu Chu-ju (吳竹如), Ho Tzu-yung (何子永), Yu Pai-ch’uan (游百川), Hung Ch’in-hsi (洪琴溪) and others. Entries in the Notebook of Daily Lessons are originally categorized under years, months and dates, with plenty of information on family, friends, the court, self-criticisms, personal emotions, etc. Unfortunately, most were excluded from publication. Hence it is less of a diary and more like a compilation of condensed notes from daily lessons. If Volume Four: Diary from Ping-wu Year of the Tao-kuang Reign actually includes the diaries from the four years of ping-wu (丙午 1846), ting-wei (丁未 1847), wu-shen (戊申 1848) and chi-yu (己酉 1849), there should be fourteen volumes of Notebook of Daily Lessons. If we use the eighty nine pages in the Manuscript Diary of Wo Jen as reference, there should be over one thousand four hundred pages in the fourteen volumes of Notebook of Daily Lessons. Yet there are only sixty-four pages in Volume Four of The Works of Wo Jen. It is deeply regrettable.

There are three inscriptions after the title page in the Manuscript Diary of Wo Jen. They are by Tou Hsü (竇垿), Chu Tz’u-ch’i (朱次琦) and Chou Ping-huang (周昺潢).

Tou Hsü (竇垿 1804-1865), hao Lan-ch’üan (蘭泉), tzu Yü-tine (於坫), Tzu-chou (子州), native of Lo-p’ing, Yunnan Province, but originally from Chiang-nan. In the 5th year of the Tao-kuang reign (1825), he attained the highest honours in the Provincial Examination. In chi-chou year, the 9th year of the Tao-kuang reign (1829), he attained the chin-shih degree, ranked Third Class Number Fifty Six. He took the same metropolitan examination as my third-great-grandfather Mr. Soong Ping-yüan and Wo Jen. He was consecutively appointed secretary, vice director and director of the Ministry of Rites, censor of Kiangsi Circuit, imperial commissioner of the Militia Company of Yunnan, and prefect of Kweichow Province. His works are Chu-ts’un lu (銖寸錄) and Wan-wen Chai kao (晚聞齋稿). In The Works of Wo Jen, two letters to Tou Hsü are recorded. In the letter of 26 October in jen-yin year by Ts’eng Kuo-fan to his brothers, he described Tou Hsü in this manner: “Wo Jen, a friend and mentor, is solemn and dignified. One is instantly respectful in his presence. Wu Chu-ju, Tou Hsü (Lan-ch’uan) are focussed on the essentials of Confucian studies, each of thcir word and action categorically observes what is correct.”

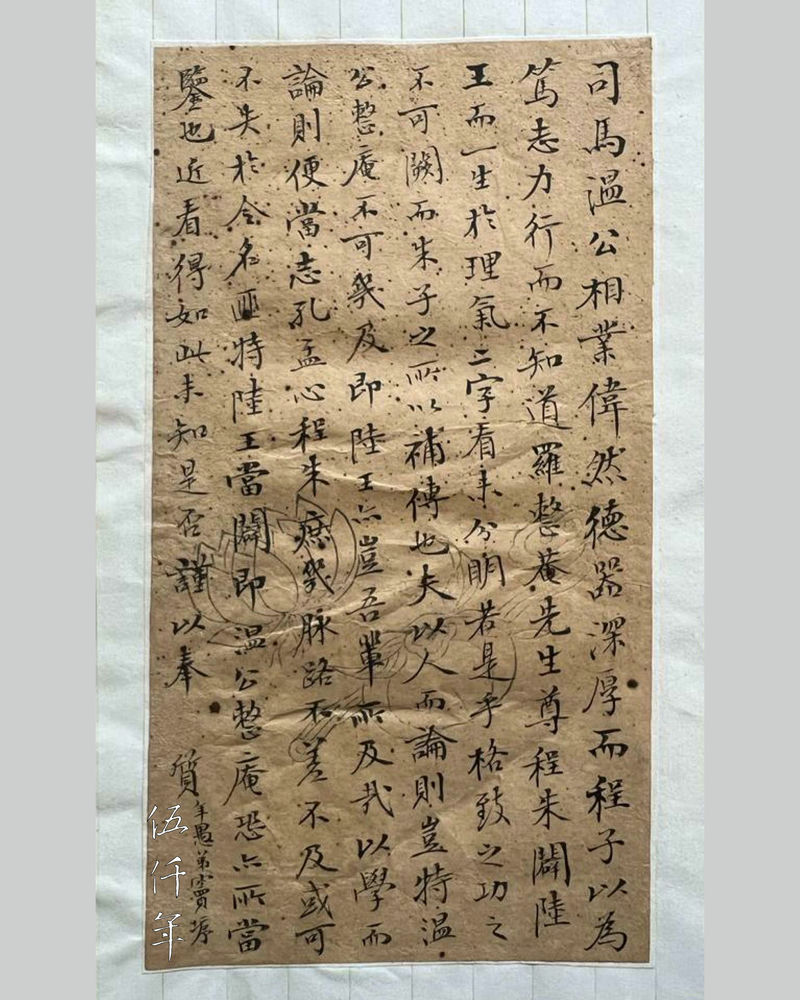

Inscription by Tou Hsü

Detail of inscription by Tou Hsü

The inscription by Tou Hsü reads:

“The achievements of Ssu-ma Kuang (司馬光 1019-1086) when he was the Grand Councilor were magnificent indeed. His virtues and talent were profound. Ch’eng Hao (程顥) believed in the resolution of implemention. They could not foretell that Lo Ch’in-shun (羅欽順 1465-1547) followed the teachings of the School of Ch’eng and Chu (Ch’eng Hao 程顥 1032-1085 and Ch’eng I 程頤 1033-1107 of the Northern Sung dynasty, Chu Hsi 朱熹 1130-1085 of the Southern Sung dynasty), he rejected the teachings of the School of Lu and Wang (Lu Chiu-yüan 陸九淵 1139-1193 of the Southern Sung dynasty and Wang Shou-jen 王守仁 1472-1529 of the Ming dynasty), while throughout his life he did not seem to have clarified the two words of Li (Principle 理) and Ch’i (Matter 氣). Since the search for the underlying principles to acquire knowledge should not be dismissed, Chu Hsi supplemented this with his teachings. Regarding the characters of these gentlemen, not only we are far from Ssu-ma Kuang and Lo Ch’in-shun, even Lu Ch’iu-yüan and Wang Shou-jen are beyond us! Regarding learning, we should aspire to Confucius and Mencius, our minds should settle for Ch’eng I and Chu Hsi. If this lineage is maintained, perhaps we will not lose our good names. Not only should we reject the teachings of Lu Chiu-yüan and Wang Shou-jen, we should be vigilant even towards the teachings of Ssu-ma Kuan and Lo Ch’in-shun. These are my recent observations, I do not know whether they are correct. I attentively offer them for your opinion.

Your younger foolish brother, Tou Hsü.”

In the short inscription, Tou Hsü discussed the School of Ch’eng and Chu, as well as the achievements and failings of eminent scholars. He touched on Ssu-Ma Kuang, Ch’eng Hao and Ch’eng I of the Northern Sung dynasty, Chu Hsi of the Southern Sung dynasty, and Lo Ch’in-shun of the Ming dynasty. He also touched on the School of Lu and Wang, Lu Ch’iu-yüan of the Southern Sung dynasty and Wang Shou-jen of the Ming dynasty.

Chu Tz’u-ch’i (1807-1881), tzu Tzu Hsiang (子襄), hao Chih-kuei (稚圭), also known as Chu Ch’iu-chiang (朱九江), native of Nan-hai, Kwangtung Province. He attained the chin-shih degree in ting-wei year, the 27th year of the Tao-kuang reign (1847), ranked Third Class Number One Hundred and Fourteen. In that year, Wo Jen was already appointed the grand minister examiner of the ting-wei year Provincial Examination, hence in his inscription, Chu Tz’u-ch’i addressed Wo Jen as his senior friend. In reality Wo Jen was only older than Chu Tz’u-ch’i by three years. Chu was once magistrate of Hsiang-ling in Shansi Province for one hundred and ninety days. During his governance, he greatly altered the customs of the county. When he left, tens of thousands of locals implored him to stay. Afterwards he led a quiet life in Ch’iu-chiang of Fo-shan in Kwangtung Province. He taught at the school of Li-shan Ts’ao-t’ang (禮山草堂) for thirty years. He was known as the Later Chu Hsi. In his final years, he burnt most of his writings. His works that remain are Shih-ju-shih Chai shih-chi (是汝師齋詩集) and Ta-ya T’ang shih-chi (大疋堂詩集).

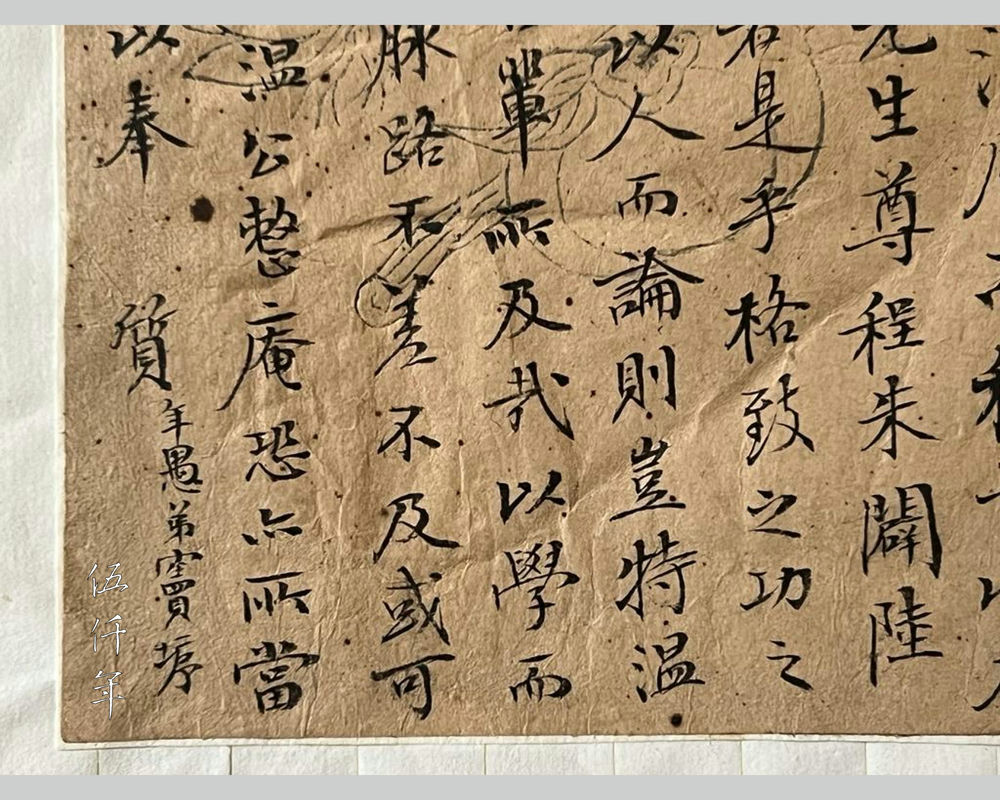

Inscription by Chu Tz’u-ch’i

Detail of inscription by Chu Tz’u-ch’i

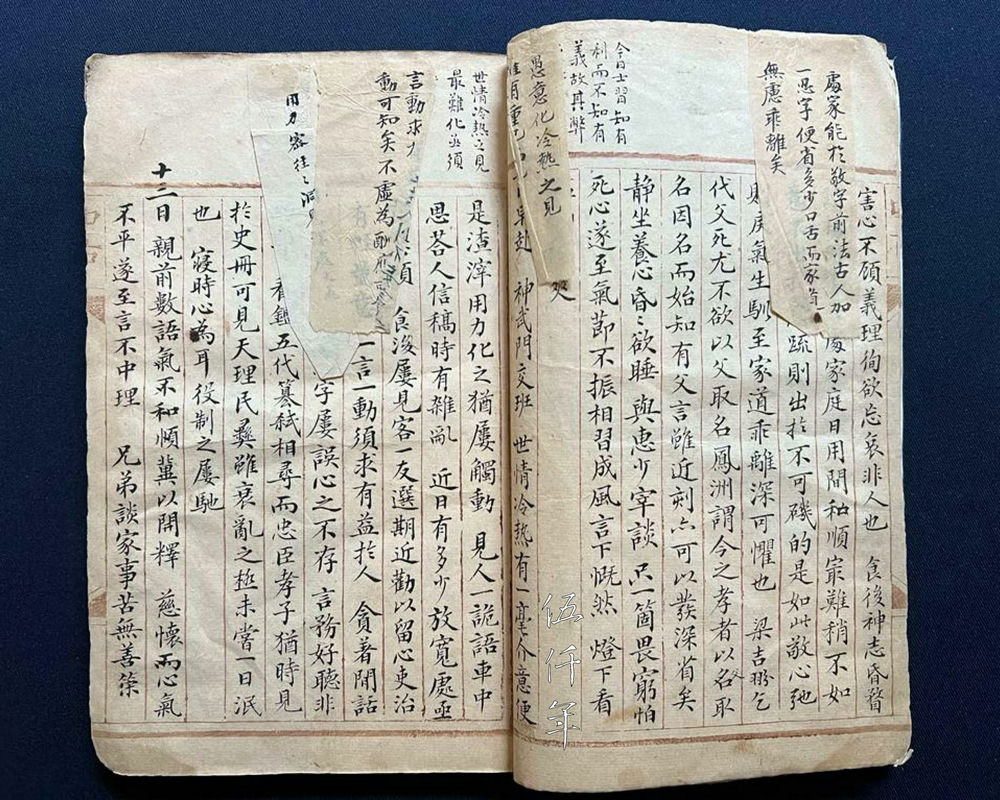

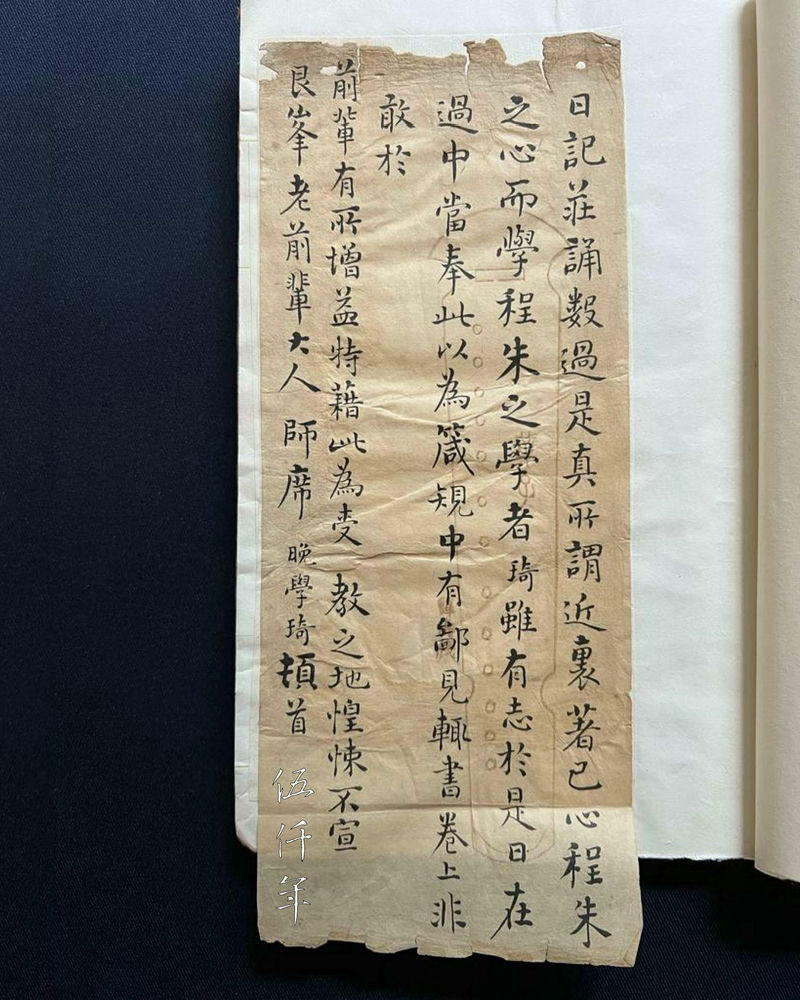

The inscription by Chu Tz’u-ch’i reads:

“I have reverently read the diary a few times. This is truly writing from the heart in proximity. This is the mind of the School of Ch’eng and Chu, learning the teachings of the School of Ch’eng and Chu. Although I have such aspiration, I spend my days in the company of my own faults. I should raise this as warning and guideline. I have some humble views, which are inscribed on the upper pages. It is not that I dare to add on to the writings of my senior friend, I use this as a place to receive your teachings. I keep silent my trepidation. To my senior friend and teacher Ken-feng. Ch’i the junior student bows.”

The first few lines of this inscription by Ch’u refer to the 29 April entry in the Manuscript Diary by Wo Jen. It reads:

“T’ang Wen-cheng (or T’ang Pin 湯斌, 諡文正 1627-1687) replied in a letter to Lu Ch’ing-hsien ( or Lu Lung-ch’i 陸隴其, 諡清獻 1630-1692):

To learn the teachings of the School of Ch’eng and Chu, one should cultivate the mind of the School of Ch’eng and Chu. When the mind is most reverential, knowledge can be pursued to great depth and exceptional detail. Pleasure, anger, sorrow, joy must be temperate. Seeing, hearing, speech, action must be in accordance with propriety. Children, officials, brothers, friends must abide by their duties. This is what a great Confucian scholar will remind himself.”

Chou Ping-huang (周昺潢), tzu Hsing-fang (星舫), Hsüan-shih (宣史), native of An-yüeh, Szechwan Province. He attained the chü-jen degree (provincial graduate). In the 25th year of the Tao-kuang reign (1845), he was appointed district magistrate of Sung-hsien in Lo-yang City, Honan Province. He took personal action in county affairs, made contributions to local drought, taught in schools, and acquired a reputation in governance. His works are: Shen-shih chin-chien (身世金緘), I-shu ch’uan-ch’ao (醫術傳抄).

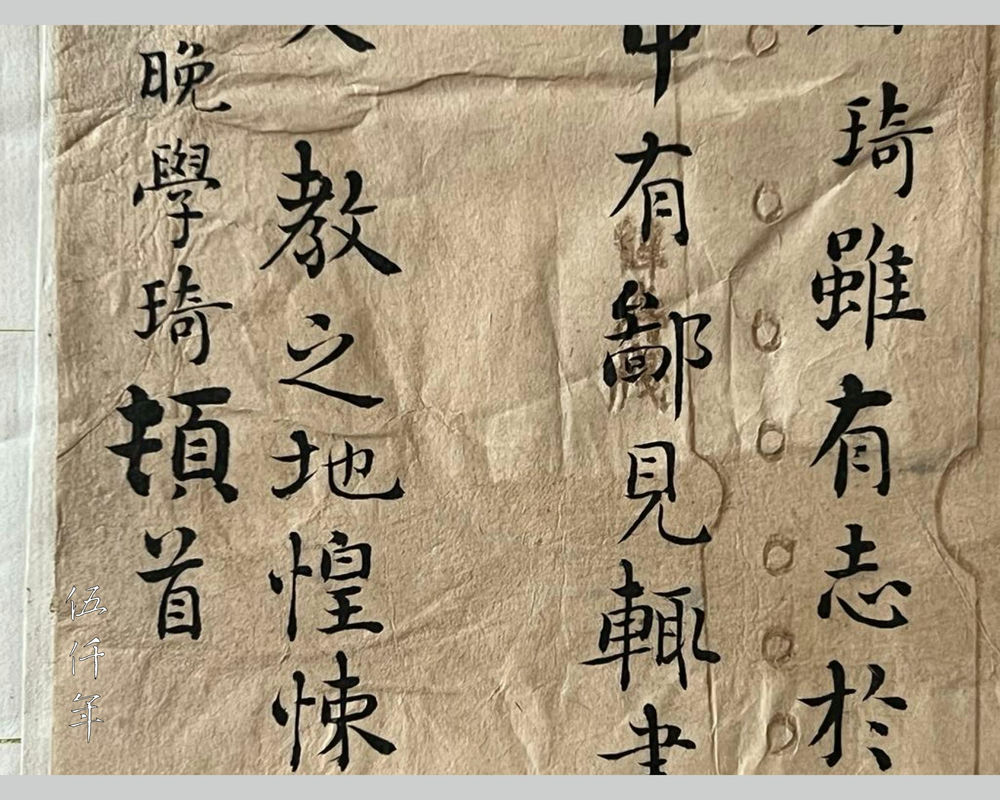

Inscription by Chou Ping-huang

Detail of inscription by Chou Ping-huang

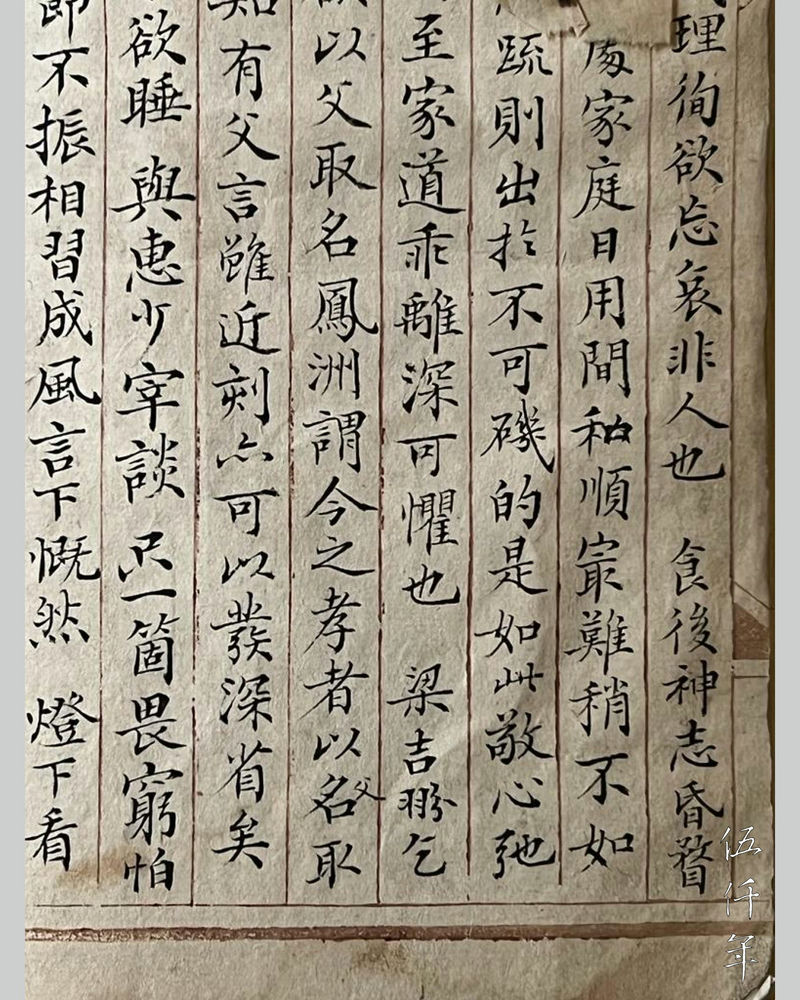

The inscription by Chou Ping-huang reads:

“The words of self-reflection and self-restraint by Confucian scholars are placed on the desk, mostly studied but not absorbed. Though occasionally one is particularly motivated and feels energetic, after a while, one reverts to sloth and neglect. By the end of the year, nothing is achieved. Furthermore, one is affected by worldly defilements, as so much time has been spent in the human world, that even The Elementary Learning of Confucianism fails to cure. The roots of past habits are hard to sever, and then comes the one day of self-admonition and forgiveness. We are all nearly the same. When do we see someone like Mr. ken-feng. who cultivates the mind, refines his nature, reflects on and reforms oneself ? I read the diary until my cheeks are red again, and perspiration ran down my back many times. I am vexed with myself for not comprehending the Confucian Way, and for learning too late. I can barely uphold myself with some minor virtue, it yields no clue about the mind nor nature, but on this matter, I managed to acquire some understanding. Sir, you have taken this on as your mission, there is not a single moment of respite in your daily life. Furthermore, you had your true friend explain to you the teachings of the School of Ch’eng and Chu in the Ming dynasty. As you are not remote from us, you have since revived the lost scholarship. However, regarding details of daily life, it seems unnecessary to examine and reform them too strictly, for the reverse is the inability to be carefree. My humble view is when you uphold the broad essentials for an extended period, your resolve will mature from the passage of time, so that if there is a little discrepancy, it will naturally turn from minuscule to nothing. I am foolish, stubborn and self-forgiving; this trivial view of mine perhaps can benefit your unadulterated cultivation. I respectfully inscribe these few words after reading, to extend my admiration, and to beseech your wisdom. I pray you will not discard a piece of writing from a faraway official.

Attentively acknowledged by your foolish younger brother Chou Ping-huang.”

The inscription describes the difficulties of self-reflection and self-restraint. It suggests ceding the inspection of small details and be less demanding. It can also be beneficial to self-improvement. A small degree of flexibility is a good formula to implement the teachings of Ch’eng and Chu.

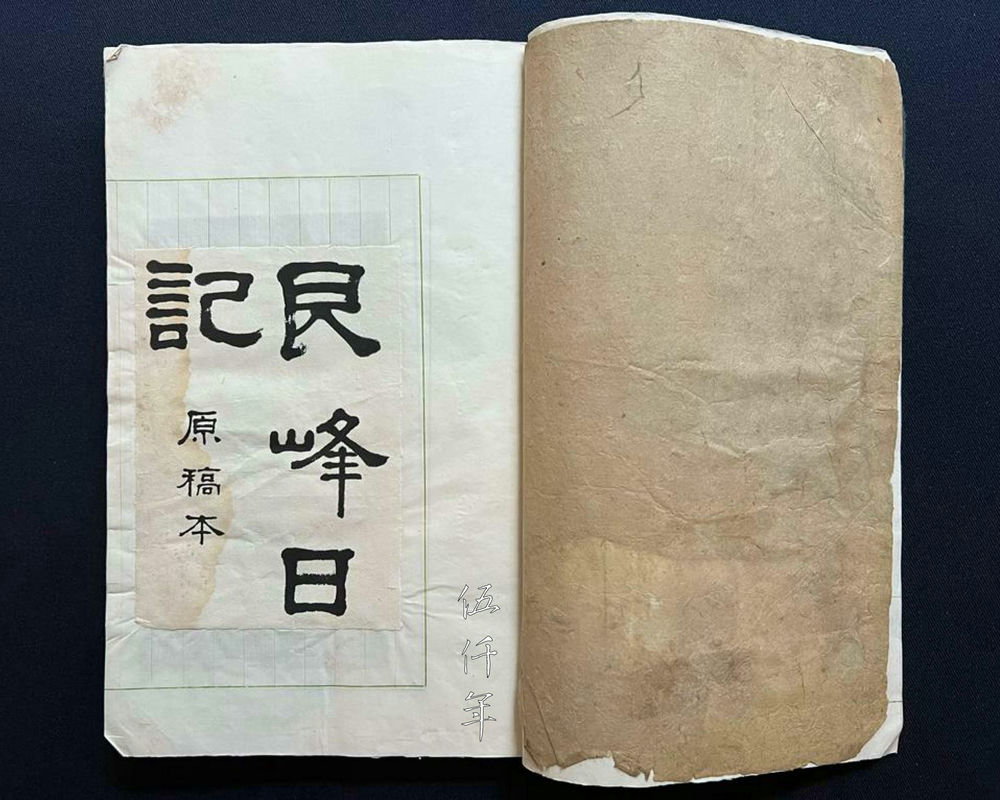

In Volume Seven of The Works of Wo Jen, Wu Ta-t’ing (吳大廷) wrote an epilogue Shu Wo Wen-tuan Kung jih-chi hou (An Epilogue of The Works of Wo Jen 書倭文端公日記後). Some lines are:

“The scholarship of Wen-tuan (Wo Jen) adheres faithfully to the teachings of Ch’eng and Chu. His diary is mostly about the initial step of self-reflection and self-observation, with emphasis on curing the faults. He does not talk about the novel nor the adventurous, but with every word he expresses his thoughts. Therefore, his writing is simple yet deeply touching.”

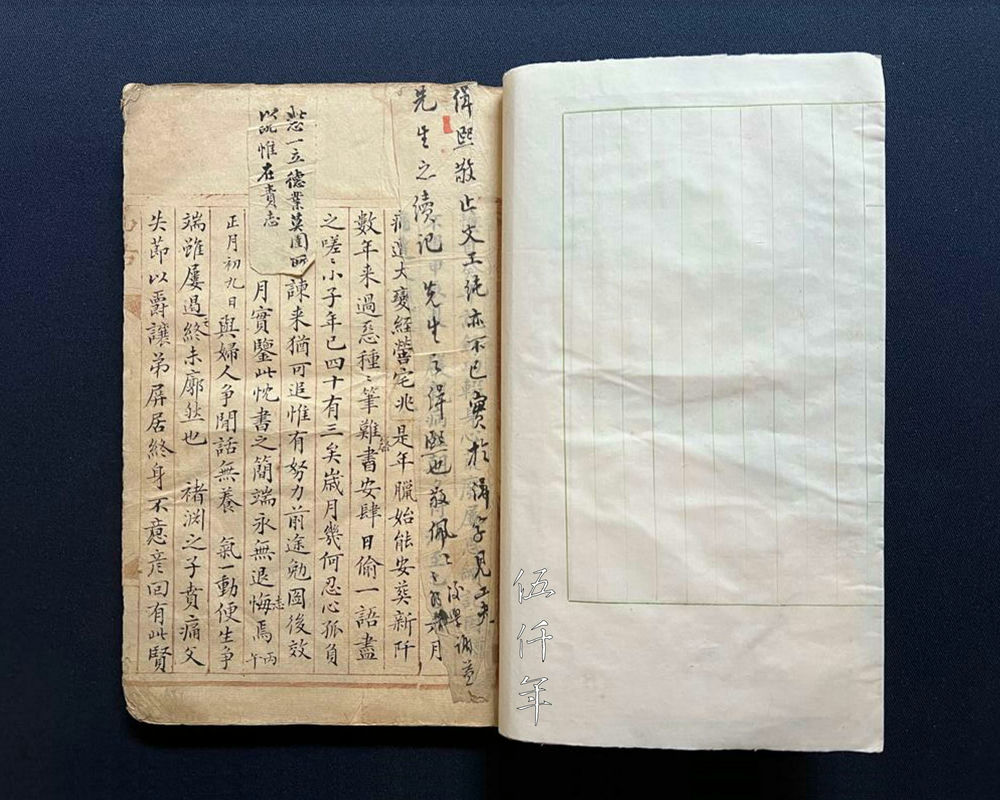

In the Manuscript Diary by Wo Jen, family intimacy and guidances to foster family harmony are frequently mentioned.

The entry on 13 January 1846 reads:

“Father is lonely in the underworld. Who will look after him there? Such sorrow!”

The entry on 15 January 1846 reads:

“Regarding the food for ancestor worship, I thought of his favorite dishes and could not help crying. On this day last year, I was still persuading him to eat something. Alas! Such sorrow!”

The entry on 10 January 1846 reads:

“Yesterday I scolded the children for getting up late. Today they all got up. Yet I was still fast asleep. I feel quite embarrassed.”

The entry on 11 January 1846 reads:

“I was tired after the meal. I read Yang-yüan-chi (楊園集). Some words are:

It is most difficult to maintain harmony in the daily life of a family. Some dissatisfaction usually comes from greater distance, or from quarrels. It is so true. The moment respectful attitude slackens, bad temper rises. Gradually the family disintegrates. This is so alarming.”

The entry on 20 February 1846 reads:

“I told my son, studying should be focussed and specialized, this is the way of the Public Examinations; it is even more so for body and mind. To teach my son, I should not complain about setting myself up as an example. I should encourage myself!”

The entry on 29 February 1846 reads:

“There should be forgiveness towards the son. I should not discipline him on my personal opinions.”

Wo Jen was meticulous with the education for his children. He also examined himself over and over again. His way of fostering family harmony was indeed fine tuned through years of Neo-Confucian training.

The children of Wo Jen were long nurtured by his teachings. In the moment of crisis at the time of life and death and great danger to the country, they did not compromise their moral rectitude.

His son Fu-hsien (福咸) was consecutively appointed officer of the salt control circuit of Kiangsu Province (江蘇鹽法道) and officer of the circuit of Hui-ning-ch’ih-t’ai-kuang-tao (徽寧池太廣道) in Anhwei Province. In the 10th year of the Hsien-feng reign (1860), he was martyred after the Taiping army sacked Ning-kuo City in Anhwei Province. He was posthumously awarded chief minister of the Court of the Imperial Stud, and commandant of cavalry.

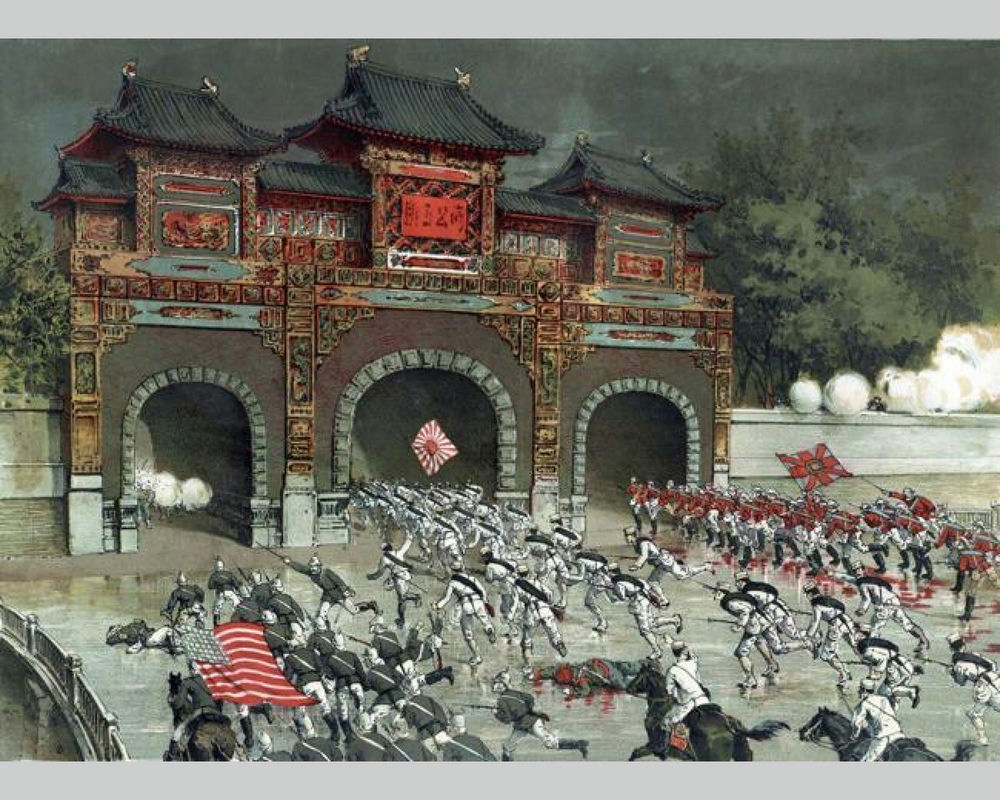

When allied forces occupied Peking in 1900, Fu-yü and Fu-jun, son and nephew of Wo Jen, committed martyrdom with their families

His son Fu-yü (福裕) was consecutively appointed salt distribution commissioner of Liang-huai, provincial administration commissioner of Kiangsu Province, and provincial administration commissioner of Kiangsi Province. In the 26th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1900), when Allied forces occupied Peking. Fu-yü committed suicide in martyrdom by taking poison. Female members in his family also died in martyrdom.

His nephew Fu-jun (福潤) was consecutively appointed governor of Shantung Province and Anhwei Province. In the 26th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1900), when Allied forces occupied Peking. Fu-jun committed suicide in martyrdom with his entire family.

One assumes that Fu-hsien, Fu-yü and Fu-jun consistently motivated themselves in their daily lives as followers of Confucianism.

There are three other paragraphs in the Manuscript Diary by Wo Jen that can be cautionary reminders in troubled times.

The entry on 11 January 1846 reads:

“This was the conversation I had with Hui the junior steward: All you need is just one person who is fearful of poverty and death, and moral rectitude will succumb. That person will influence others and make the trend prevalent. We sighed.”

The entry on 13 January reads:

“To act while knowing it is an impossible feat, comes from a heart that is full of compassion. Do not ask the way of the world nor the way of others’ hearts, do not let this passion for goodness subside.”

The entry on 16 April 1846 reads:

“Let us see what Mr. Lü said about governance: The priority of government is to nurture Righteousness (正氣), the foundation of the whole country is to nurture Vitality (元氣). This is a profound and truthful expression of the rationale of benevolence towards the people and love for all beings. They are all derived from complete sincerity and compassion.”

These are words from a Confucian scholar trying to save the world that I unexpectedly encounter on some tenuous and frail pieces of paper. In this world of turmoil, how can one be unmoved?

Inside page detail of Manuscript Diary of Wo Jen