Tuan Fang (端方), in his official posts as minister of the Canton-Hankow Railway and the Hankow-Szechuan Railway as well as viceroy of Szechuan Province, realized martyrdom on 27th November 1911 in allegiance to the Ch’ing dynasty. His collection of epigraphs had been long dispersed into the four corners of the world. Inkrubbings of these epigraphs are seen now and again in the market. The Dragon Growl Inkstone that belonged to Tuan Fang, now in the Collection of The Studio of Prunus Ode, is the only known inkstone left by Tuan Fang. It is attributed that the inkstone was acquired from the descendants of T’an Yen-k’ai (譚延闓 1880-1930), former president of the Republic of China.

In the 31st year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1905), Tai Hung-tz’u (戴鴻慈 1853-1910) and Tuan Fang were appointed Ministers to Survey the Constitutions of Different Nations. On their return to China, they propagated constitutional monarchy, inaugurating the concept of a democratic political system for China. A century and more afterwards, surveying mainland China, the despondency is relentless.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

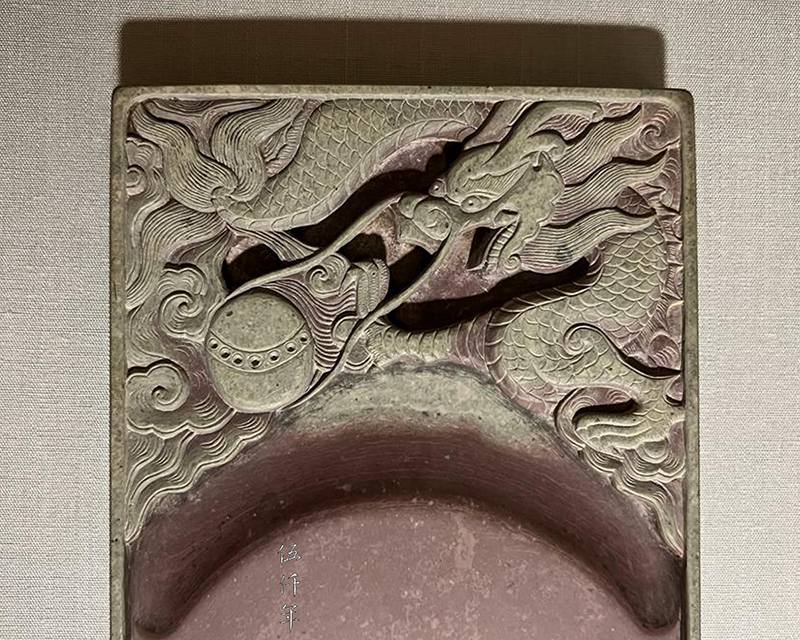

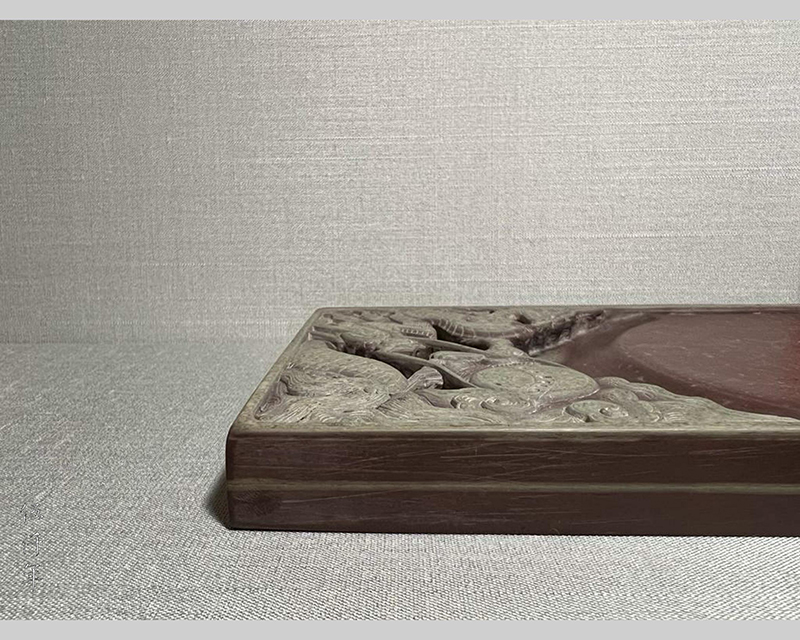

Carved dragon on the “Dragon Growl Inkstone”

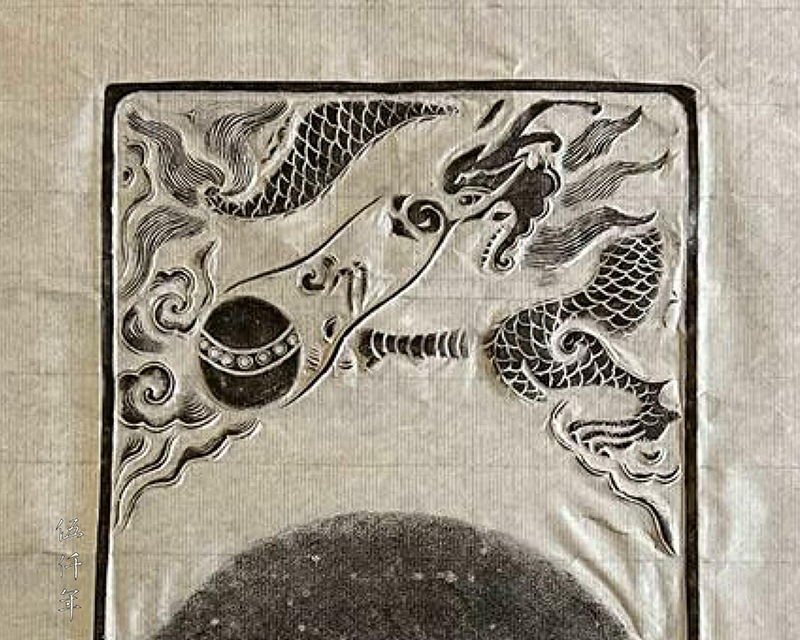

Inkrubbing of carved dragon on the “Dragon Growl Inkstone”

At the end of the Ch’ing dynasty, the one who was a prominent reformist high official, a major collector of epigraphs, a venerable viceroy who sought martyrdom, was no other than Tuan Fang.

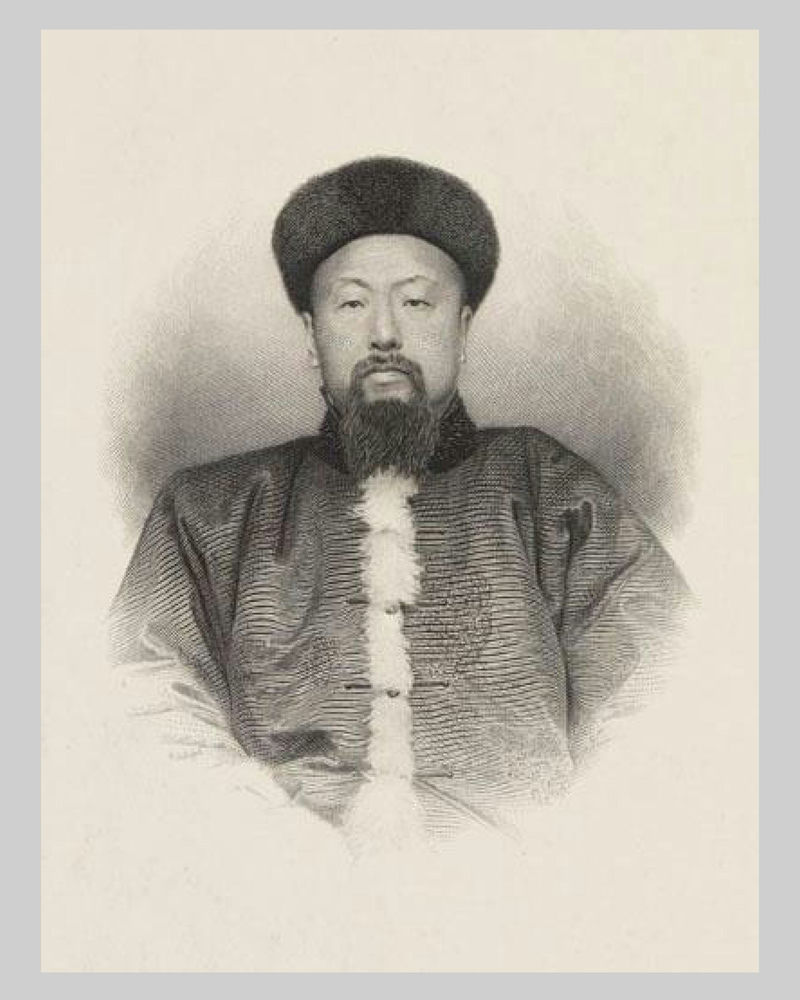

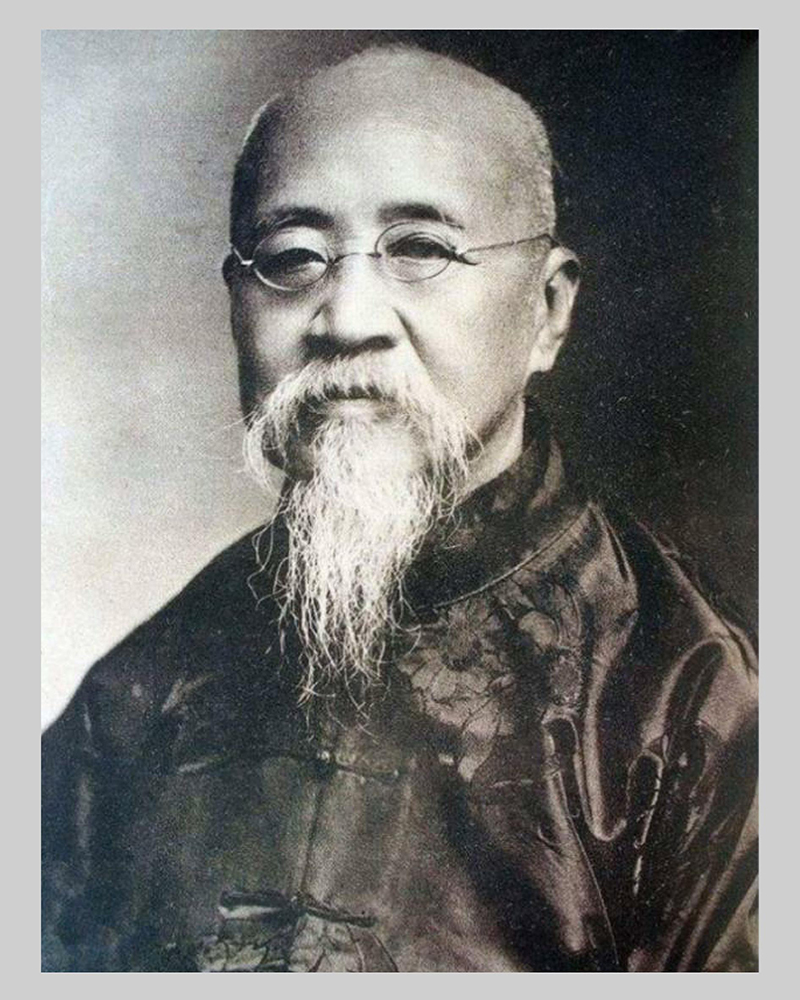

Portrait of Tuan Fang

Tuan Fang (1861-1911), tzu Wu-ch’iao (午橋), also written as Wu-ch’iao (午樵), or Wu-ch’iao (悟樵), hao T’ao-chai (陶齋), also written as T’ao-chai (匋齋), posthumous name Chung-min (忠敏), Manchu surname T’o-t’e-k’ei (托忒克). He belonged to the Manchu Plain White Banner, native of Keng-yang (浭陽), Chih-li (直隸) Region.

Around the 5th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1879), Tuan Fang attained the qualification of yin-sheng (蔭生), Imperial College student by inheritance. Yin-sheng qualification was inaccessible through imperial examination, it was a special accord from the Court to acknowledge the contributions of the person’s forefathers, entitling the person to study at Kuo-tzu-chien (國子監), the Imperial College. In the 8th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1882), Tuan Fang attained the degree of chü-jen (舉人), a provincial graduate. In the 11th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1885), his father passed away, and in the following year, his mother passed away too. He did not hold any official posting for three years in order to abide by the custom of Ting-yu (丁憂), known as the custom of filial mourning.

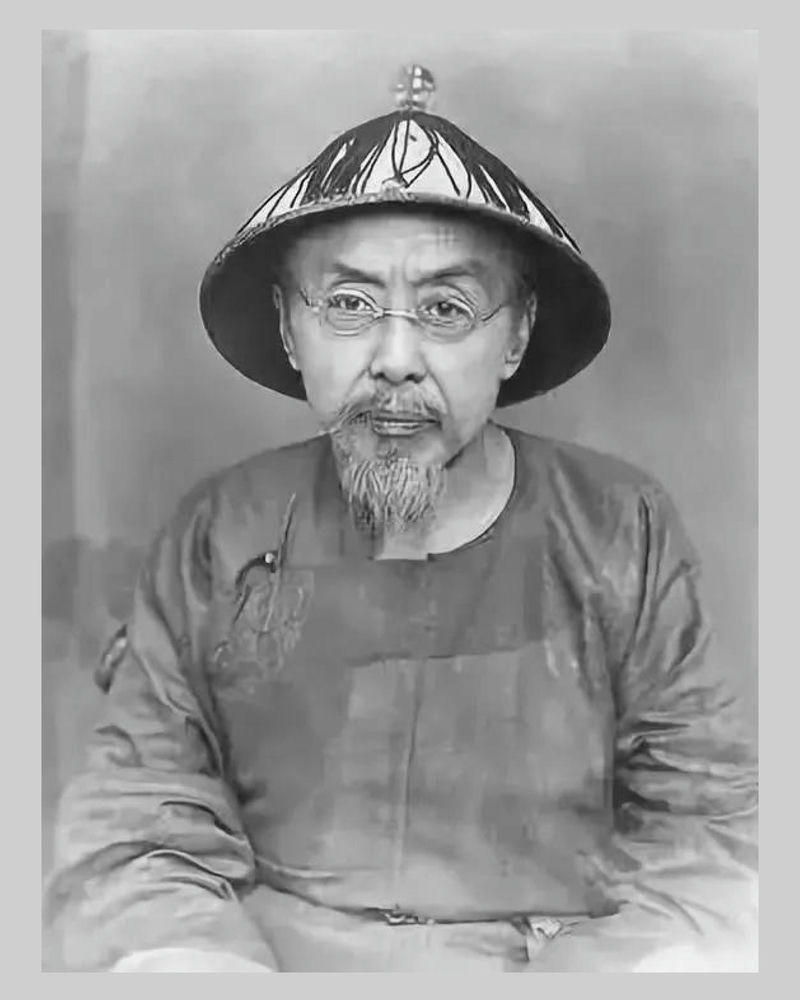

Portrait of Jui Hsün

In Jui Hsün chi chi-chien (瑞洵集輯箋 Compiled Annotations of the Collected Works of Jui Hsün), written by the assistant editor of the Bureau of Historia Ch’ing (清史館) Jui Hsün (瑞洵 1858-1936), and annotated by Tu Hung-ch’un (杜宏春) and Cheng Feng (鄭峰), there is a concise summary of the life and appointments of Tuan Fang, especially regarding his early postings. It reads:

“In the 15th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1889), Tuan Fang made some monetary contribution to attain the appointment of deputy director at the Ministry of Works. He was then consecutively appointed assistant editor, editor, assistant to chief-editor of Hui-tien Kuan (會典館 Compilation Bureau of the Encyclopedia of Jurisdiction and Administration Matters of Great Ch’ing). In the 17th year (1891), he was appointed superintendent of Chang-chia-k’ou (張家口), in the 19th year (1893), he was promoted director of the Ministry of Works. In the same year, he was appointed manager of Chieh-shen K’u (節慎庫) in charge of silver storage for imperial use under the Ministry of Works. In the 24th year (1898), he was intendant of Pa-ch’ang Circuit (霸昌道) of Chih-li, and appointed surveillance commissioner of Shensi Province.

In the 25th year (1899), he was provincial administration commissioner of Shensi Province, in the same year, acting provincial governor of Shensi Province. In the 26th year (1900), he was appointed provincial administration commissioner of Honan Province. In the 27th year (1901), he was acting provincial governor of Shensi Province, in the same year, he was provincial governor of Hupeh Province. In the 28th year (1902), he was simultaneously viceroy of Hunan and Hupeh Provinces. In the 30th year (1904), he was simultaneously provincial governor of Kiangsu Province, and in the same year, he was viceroy of Kiangsu, Anhwei and Kiangsi Provinces. In the 31st year (1905), he was appointed provincial governor of Hunan Province, he then went abroad on a diplomatic mission to survey various constitutions, and later in the same year, he was viceroy of Fukien and Chekiang Provinces. In the 32nd year (1906), he was viceroy of Kiangsu, Anhwei and Kiangsi Provinces. In the 34th year (1908), he was also made in charge of salt distribution in Kiangsu and Anhwei Provinces. In the 1st year of the Hsüan-t’ung reign (1909), he was appointed viceroy of Chih-li, and also in charge of salt distribution in Ch’ang-lu. In the third year of the Hsüan-t’ung reign (1911), he was minister to supervise the Canton-Hankow Railway and the Hankow-Szechuan Railway, and also viceroy of Szechuan Province. In the same year, he died in the line of duty. He was given the posthumous title T’ai-tzu Shao-pao (太子少保), Junior Guardian of the Heir Apparent, and the posthumous name Chung-min (忠敏).

His works are: Tuan Chung-min Kung tsou-i (端忠敏公奏議 The Memorials of Mr. Tuan Chung-min), T’ao-chai chi-chin lu (陶齋吉金錄 A Record of Epigraphs from T’ao-chai), T’ao-chai chi-chin lu-hsü (陶齋吉金錄續 A Supplement to the Record of Epigraphs from T’ao-chai), T’ao-chai ts’ang-chuan chi (陶齋藏磚記 A Chronicle of Ancient Bricks in the Collection of T’ao-chai) and Ou-mei cheng-chih yao-i (歐美政治要義 The Principles of European and American Political Systems).”

Tuan Fang began his career in the civil service at the age of twenty nine, and ended his career in martyrdom at the age of fifty one. In a hasty stretch of twenty three years, he was recognized to have reached the heights of official career. In his leisure time, he was all the same unrelenting in his pursuit of antiquities, becoming a great collector of epigraphs of that era.

Front of “Dragon Growl Inkstone”

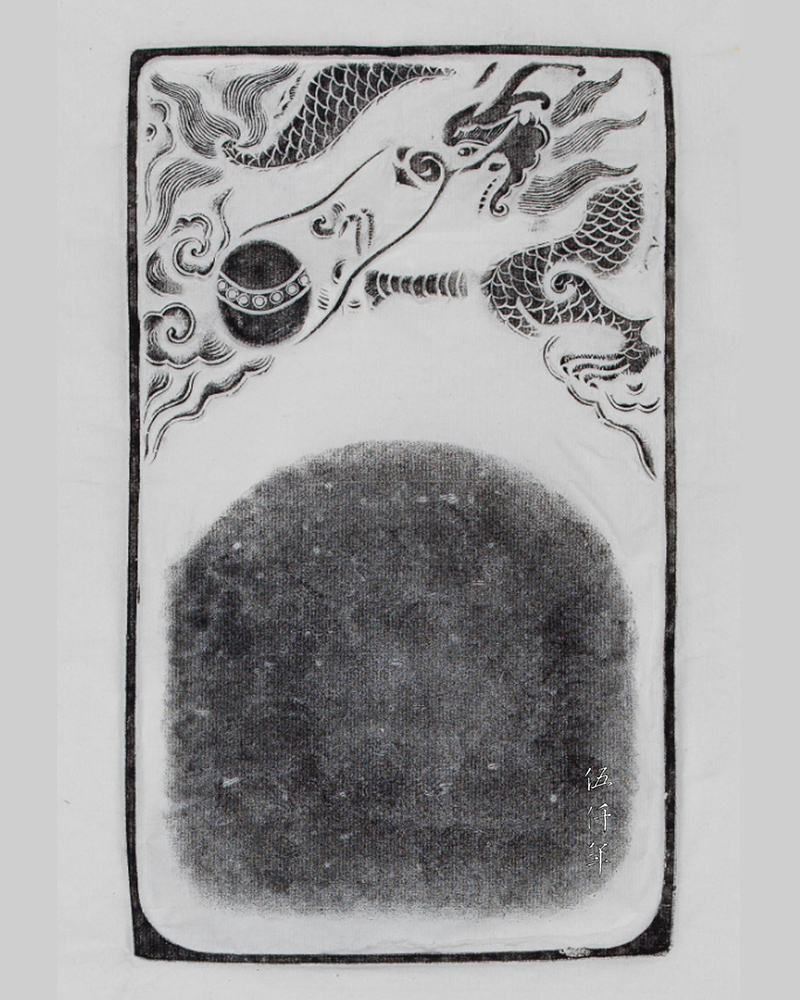

Inkrubbing of front of “Dragon Growl Inkstone”

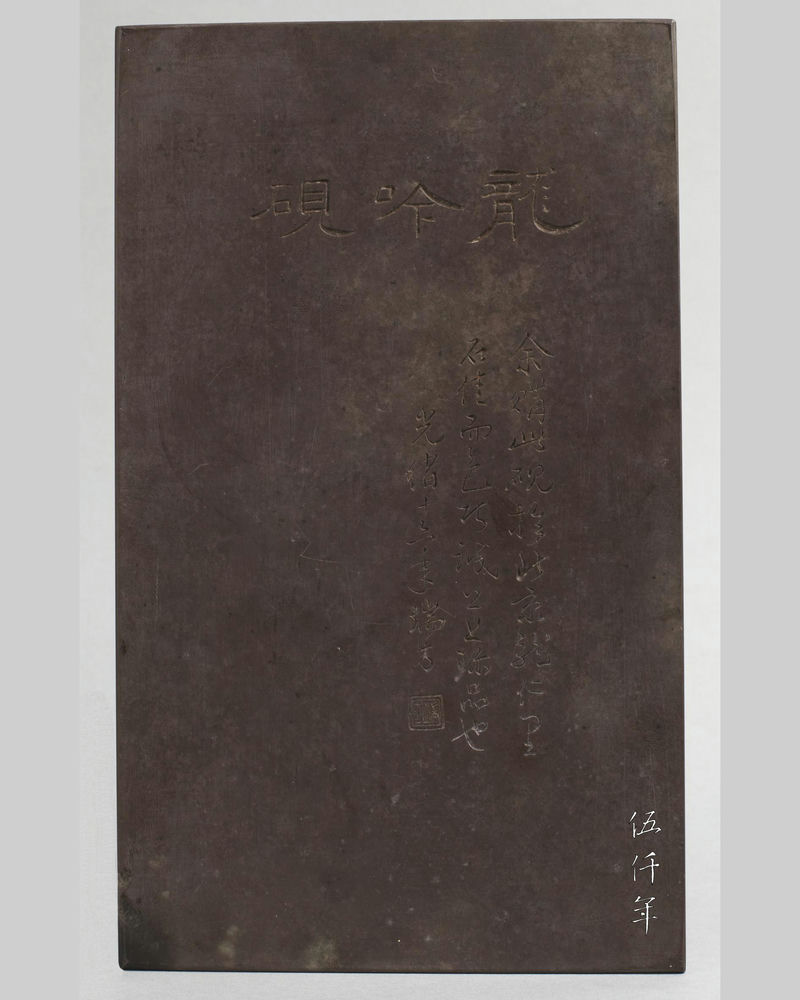

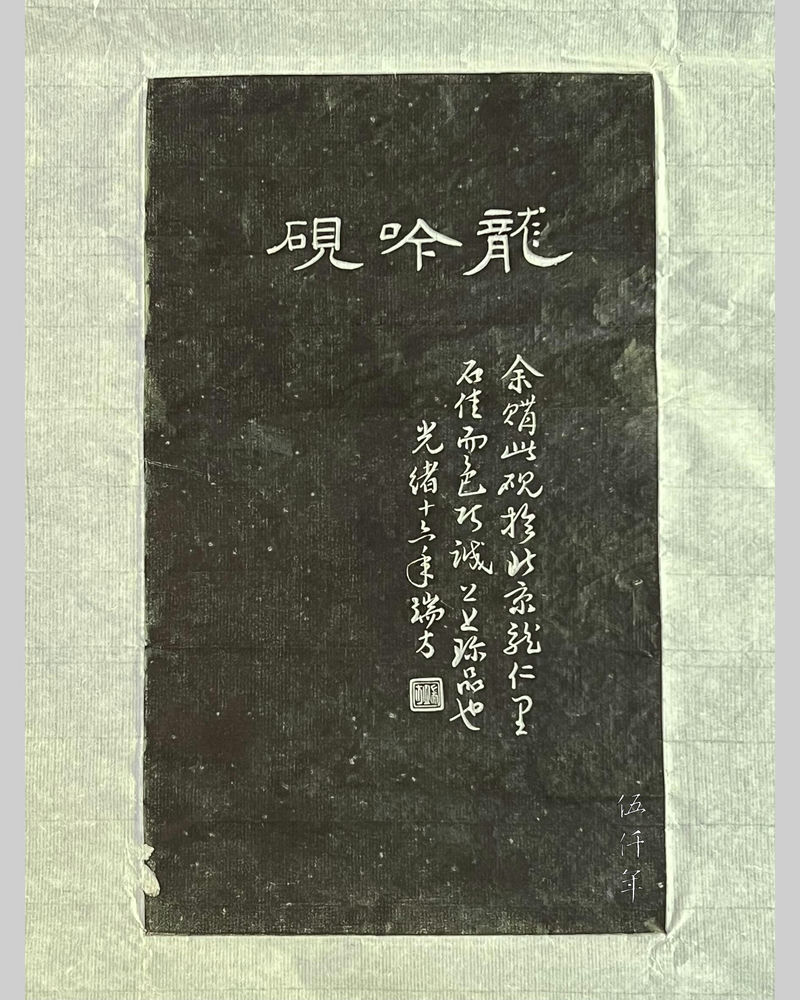

Back of “Dragon Growl Inkstone”

Inkrubbing of back of “Dragon Growl Inkstone”

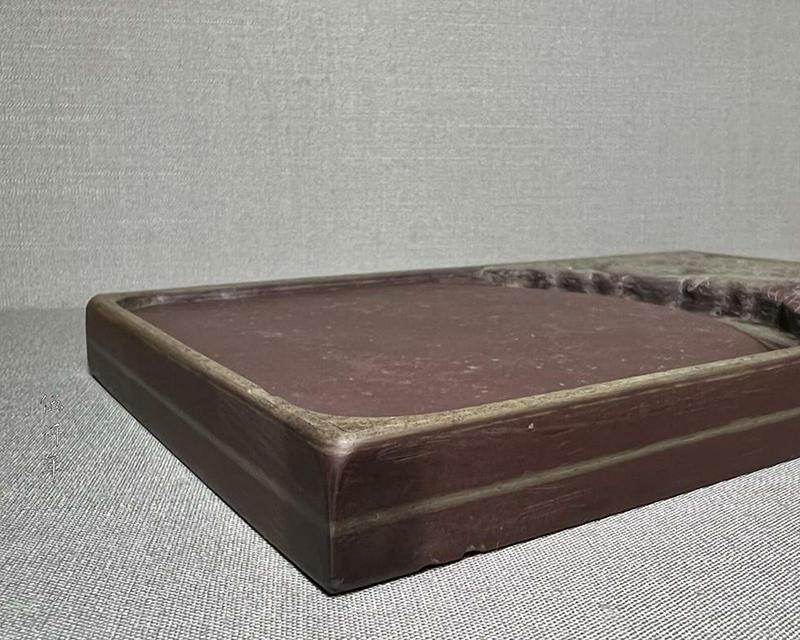

The “Dragon Growl Inkstone” in the Studio of Prunus Ode, is an artefact that once belonged to Tuan Fang. The length of the inkstone is 22.8 cm, its width is 13.6 cm, its height is 2cm. Near the middle of the inkstone, the concave water pond is in the shape of half-moon. Above the concave water pond is a dragon in cloud puffs playing with a pearl. The carving is bold and vigorous, its exuberance overpowering. The two dragon whiskers clutch the pearl, and the four claws pounce towards it. Along the four sides of the inkstone, there is a natural thin white vein on the stone that runs parallel to the rim of the inkstone, resembling a jade belt around the waist.

First view of a thin natural white vein on the four sides of the stone, resembling a jade belt.

Second view of a thin natural white vein on the four sides of the stone, resembling a jade belt.

Third view of a thin natural white vein on the four sides of the stone, resembling a jade belt.

Fourth view of a thin natural white vein on the four sides of the stone, resembling a jade belt.

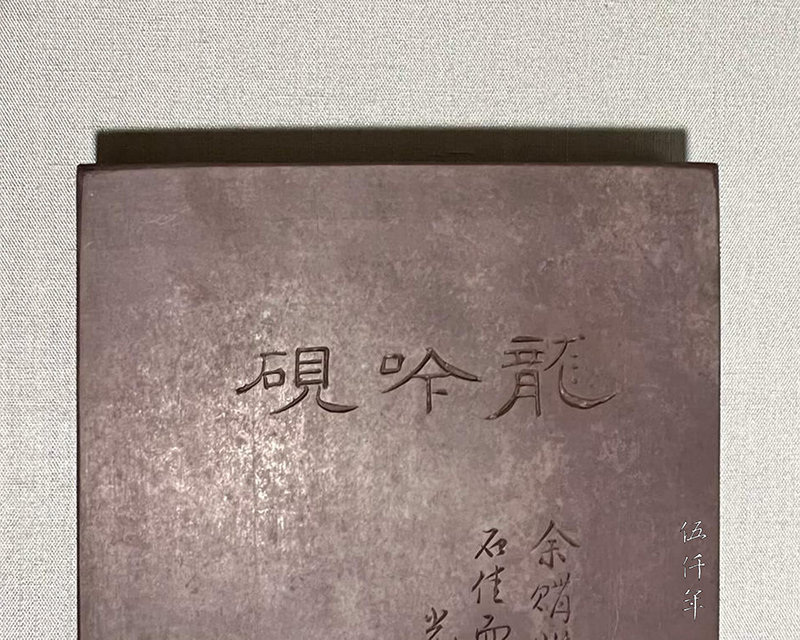

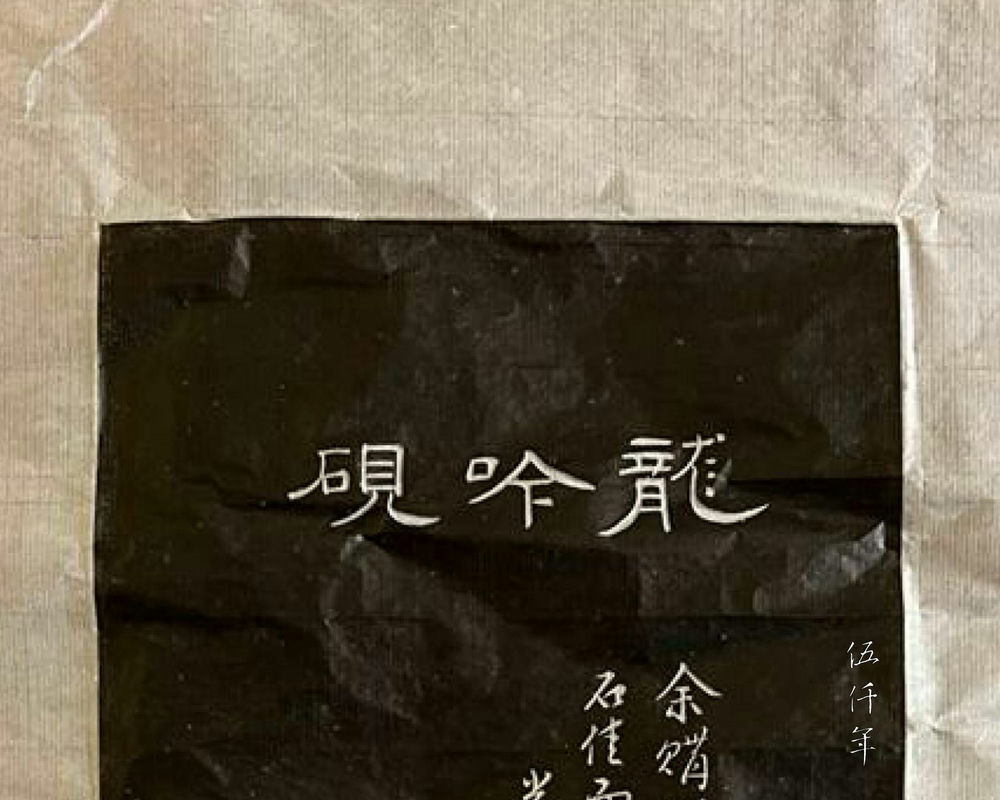

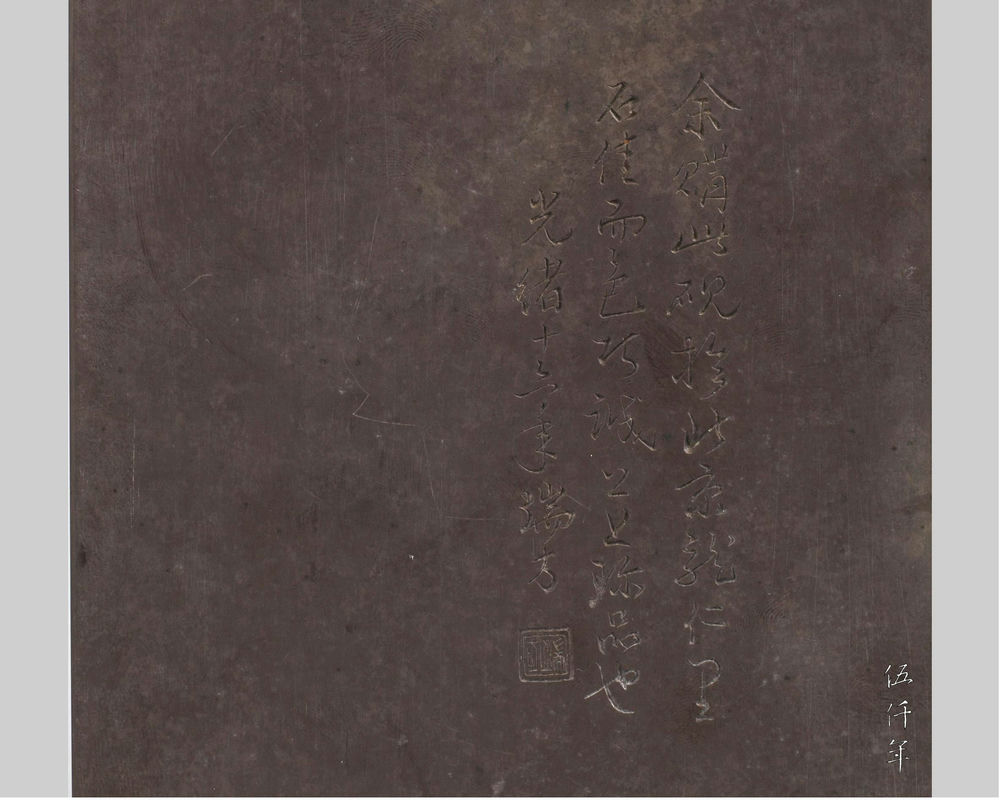

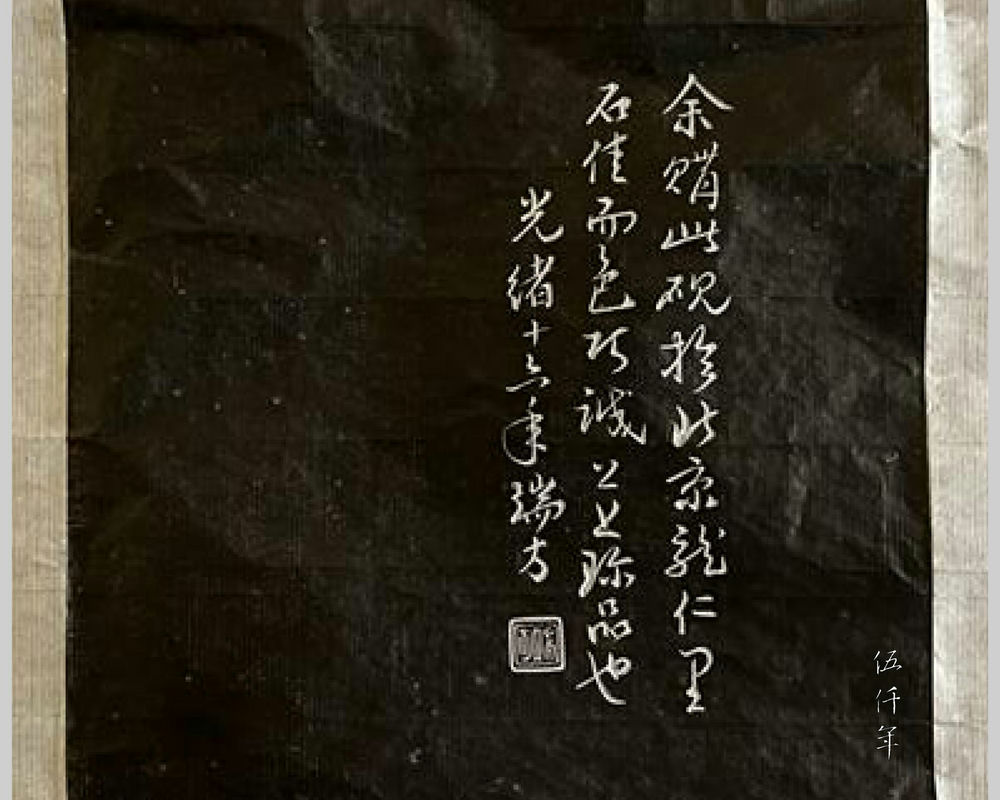

At the back of the inkstone, there are three characters carved in clerical script: “Lung-yin Yen (龍吟硯)”, meaning “Dragon Growl Inkstone”. There are three lines of small characters in cursive script, their calligraphic strokes are imbued with energy and vitality. It reads:

“I bought this inkstone at Lung-jen Li in Peking. The stone is fine and and the colour is subtle, truly an unsurpassable treasure. Tuan Fang, in the 16th year of the Kuang-hsü reign.”

Engraved seal legend: “Tuan Fang”

Characters of “Lung-yin Yen” (龍吟硯) in clerical script engraved at the back of the inkstone

Inkrubbing of the characters “Lung-yin Yen” (龍吟硯) in clerical script engraved at the back of the inkstone

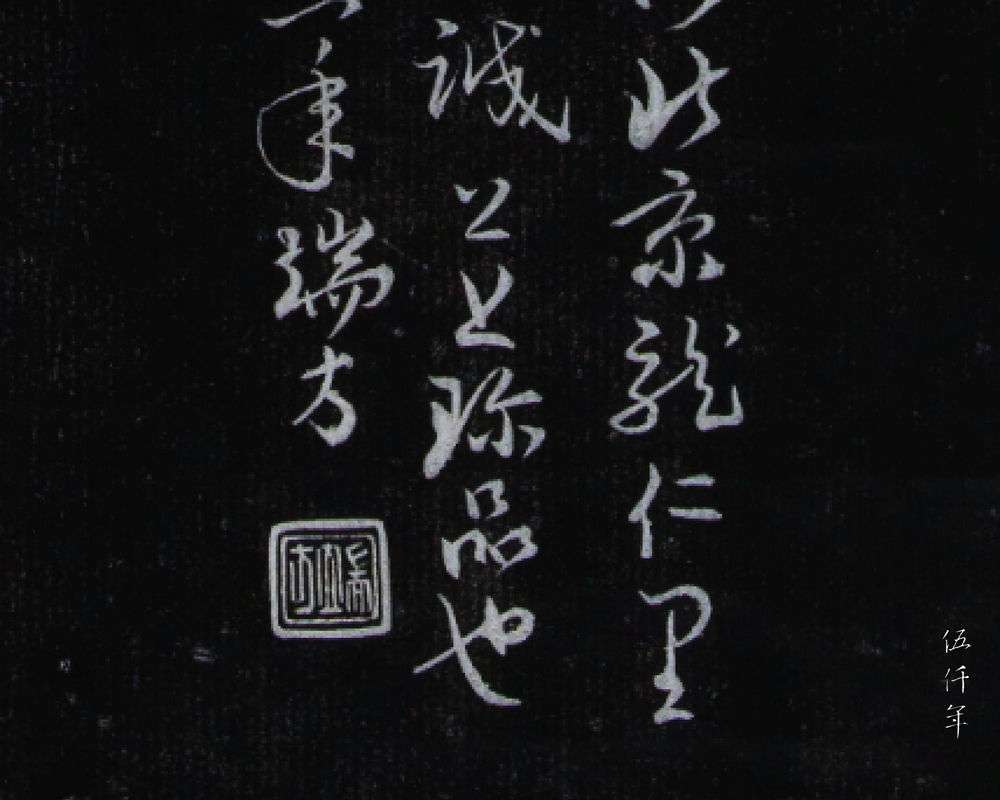

Small characters in cursive script engraved at the back of the inkstone

Inkrubbing of small characters in cursive script engraved at the back of the inkstone

The 16th year of the Kuang-hsü reign is the equivalent year of 1890 in the Gregorian calendar. Tuan Fang was thirty years old and living in Peking. According to Jui Hsün chi chi-chien (瑞洵集輯箋 Compiled Annotations of the Collected Works of Jui Hsün), in the 15th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1889), Tuan Fang acquired the position of deputy director at the Ministry of Works through a monetary contribution. There were six ministries in the Ch’ing government, Personnel (吏部), Revenue (戶部), Rites (禮部), War (兵部), Justice (刑部) and Works (工部). Ministry of Works was responsible for construction and roads, canals and flood controls, manufacturing and machinery, mining and textile, etc. Deputy director was a sinecure official posting, it belonged to the lower fifth rank within nine ranks or p’in (品) of the civil service. Merchants and gentlemen of leisure in late Ch’ing often acquired this official position through monetary contributions.

In the 16th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1890), Tuan Fang was consecutively appointed assistant editor, editor and assistant to chief-editor of Hui-tien Kuan (會典館 Compilation Bureau for the Encyclopedia of Jurisdiction and Administration Matters of Great Ch’ing). Hui-tien Kuan was in charge of the compilation of Ch’in-ting Ta-Ch’ing hui-tien (欽定大清會典 Encyclopedia of Jurisdiction and Administration Matters of Great Ch’ing by Imperial Order). In the Ch’ing dynasty, the Encyclopedia was edited and revised five time. The first edition was undertaken between the 23rd year (1684) to the 29th year (1690) of the K’ang-hsi reign. The second edition was undertaken between the 2nd year (1724) to the 10th year (1732) of the Yung-cheng reign. The third edition was undertaken between the 12th year (1747) to the 29th year (1764) of the Ch’ien-lung reign. The fourth edition was undertaken between the 6th year (1801) to the 23rd year (1818) of the Chia-ch’ing reign. The fifth edition was undertaken between the 12th year (1886) to the 25th year (1899) of the Kuang-hsü reign. Hui-tien Kuan was only a temporary bureau, it was not designated to any fixed location during these reigns. In the Kuang-hsü reign, it was located in a group of buildings north of San-zuo Men (三座門) inside the East Prosperity Gate (東華門) of the Forbidden City. Altogether the buildings composed of one hundred and eight rooms.

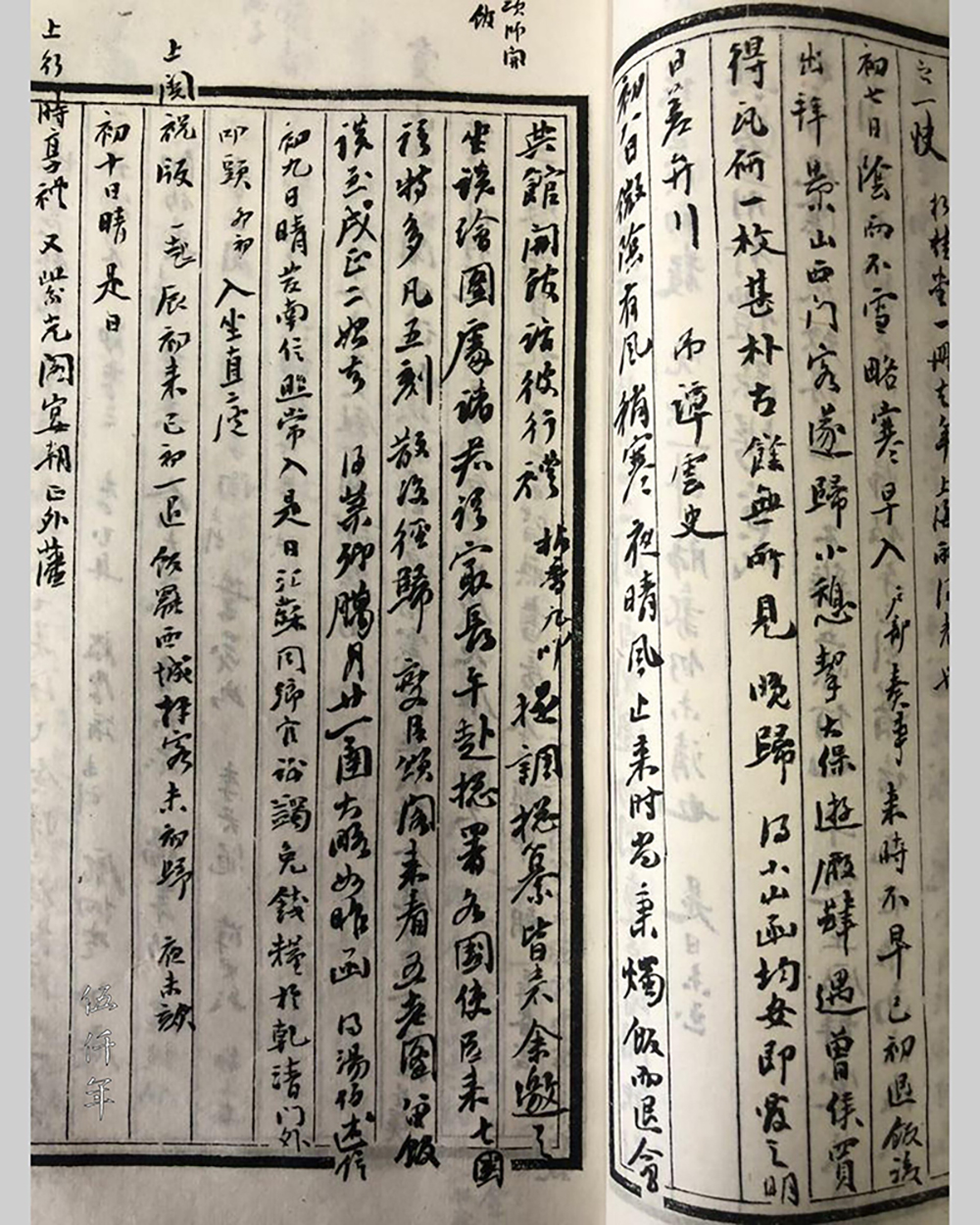

Entry on 8th January in the 16th year of the Kuang-hsü reign in Weng Wen-kung Kung jih-chi (翁文恭公日記 The Diary of Mr. Weng Wen-kung)

In Weng Wen-kung Kung jih-chi (翁文恭公日記 The Diary of Mr. Weng Wen-kung) by Weng T’ung-ho (翁同龢 1830-1904), it chronicles:

“Hui-tien Kuan opened on 8th January in the 16th year of the Kuang-hsü reign. I went there to pay my respect. Holding the incense in my hands, I kowtowed nine times. The examination supervisor (提調) and the chief-editor (總纂) all attended. I invited them to a conversation, and spent the longest time with those from the drawing department.”

Thus we learned that when Hui-tien Kuan opened in early January, senior officials all gathered to perform the formal ceremony of kneeling down thrice and kowtowing nine times. It was a most respectful and attentive event. In the course of that year, Tuan Fang was elated by the acquisition of the “Dragon Growl Inkstone”. He would have used this inkstone to painstakingly grind ink for his assiduous editing of the Encyclopedia of Jurisdiction and Administration Matters of Great Ch’ing. Accompanied by the “Dragon Growl Inkstone”, Tuan Fang thenceforth embarked on his career in the civil service.

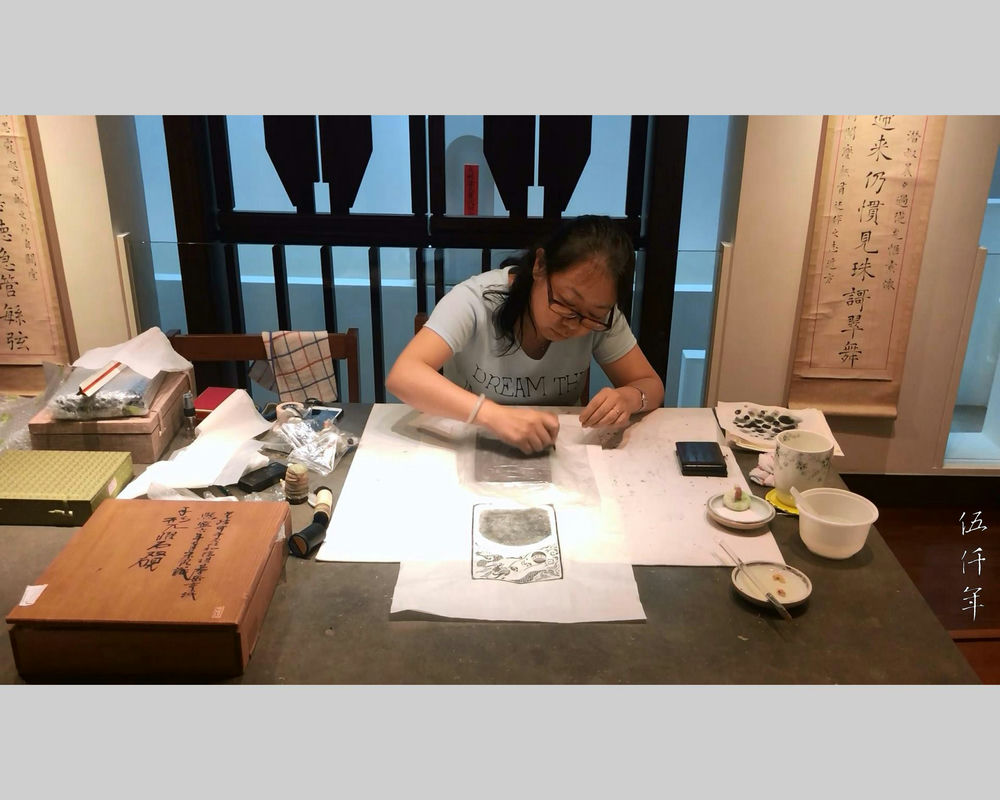

Ms. Sun K’ei-ping (孫克冰女士) making an inkrubbing of the “Dragon Growl Inkstone”

In June the 108th year of the Republic (2019), Ms. Sun K’ei-ping (孫克冰女士), master of inkrubbing, made a special trip to Taiwan from Kyoto, Japan, to help with the inkrubbing of artefacts collected in the Studio of Prunus Ode. Ms. Sun, with her artistry of inkrubbing, is renowned in China and Japan. Her husband Mr. Wada Daikyo (和田大卿先生) is also an eminent seal engraver and calligrapher in Japan. I have kept a video clip of Ms. Sun making an inkrubbing of the “Dragon Growl Inkstone”, as well as the inkrubbing of the “Dragon Growl Inkstone” itself. They are indeed traces of our own addictions to epigraphy.

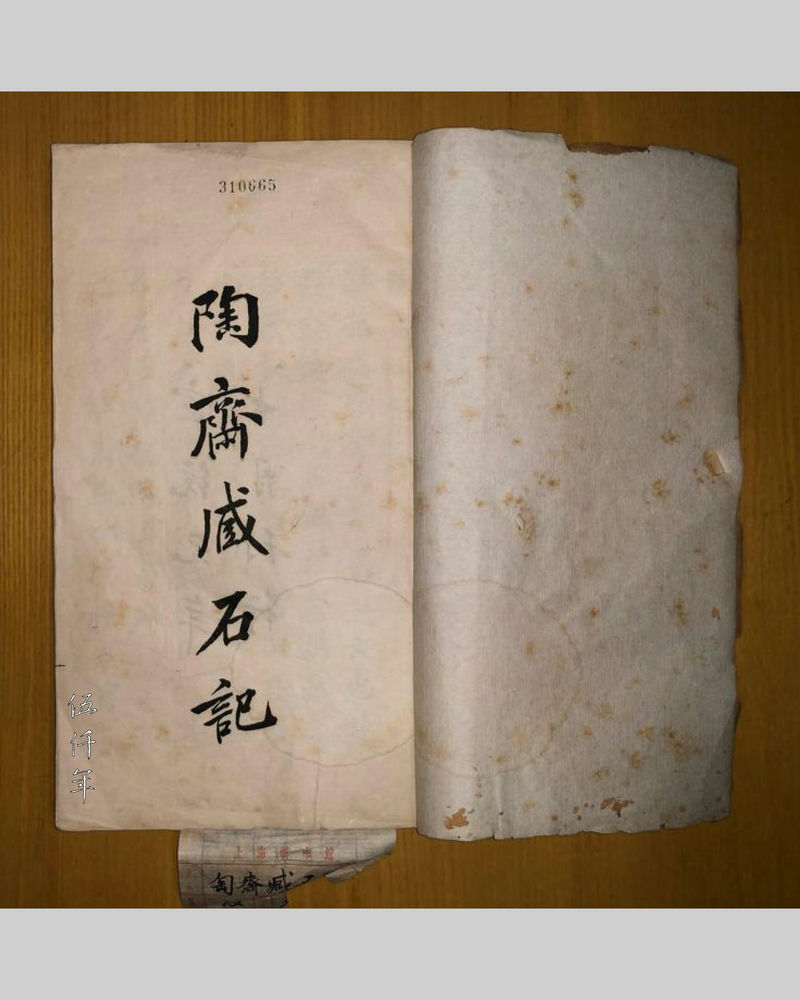

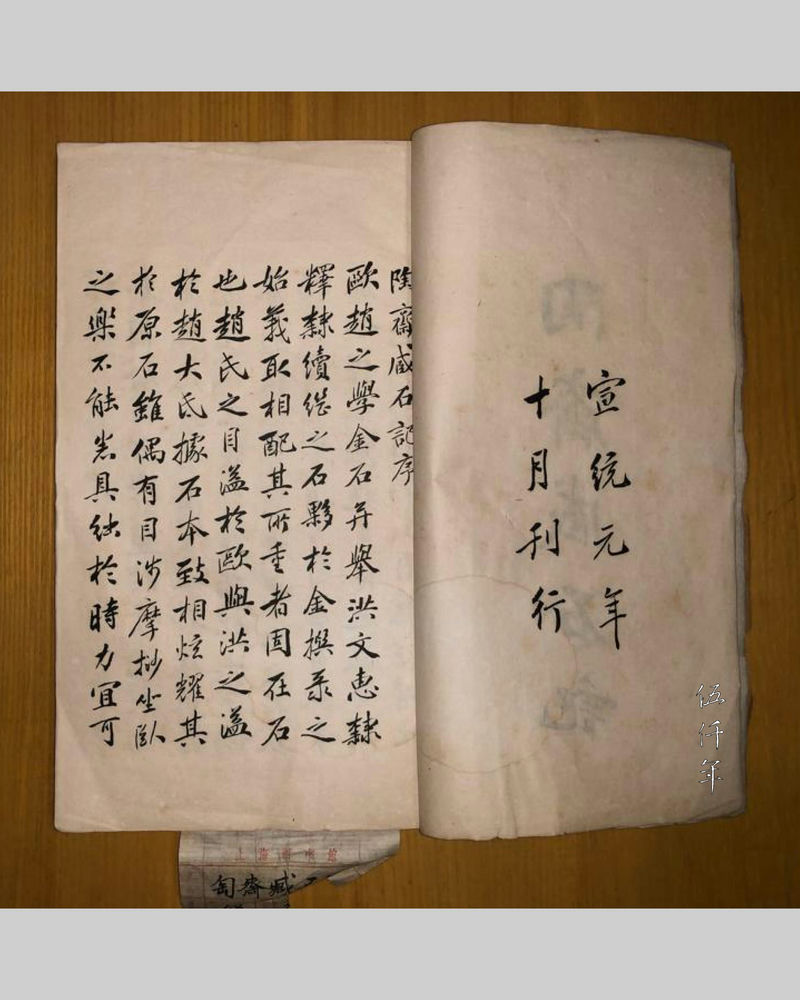

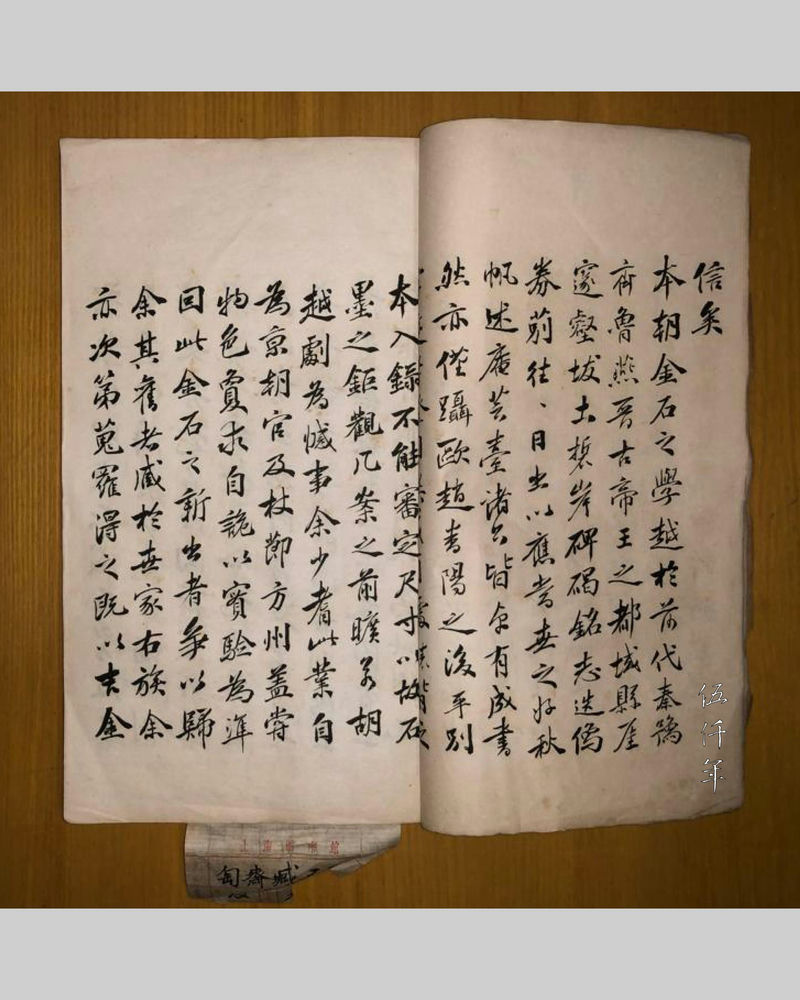

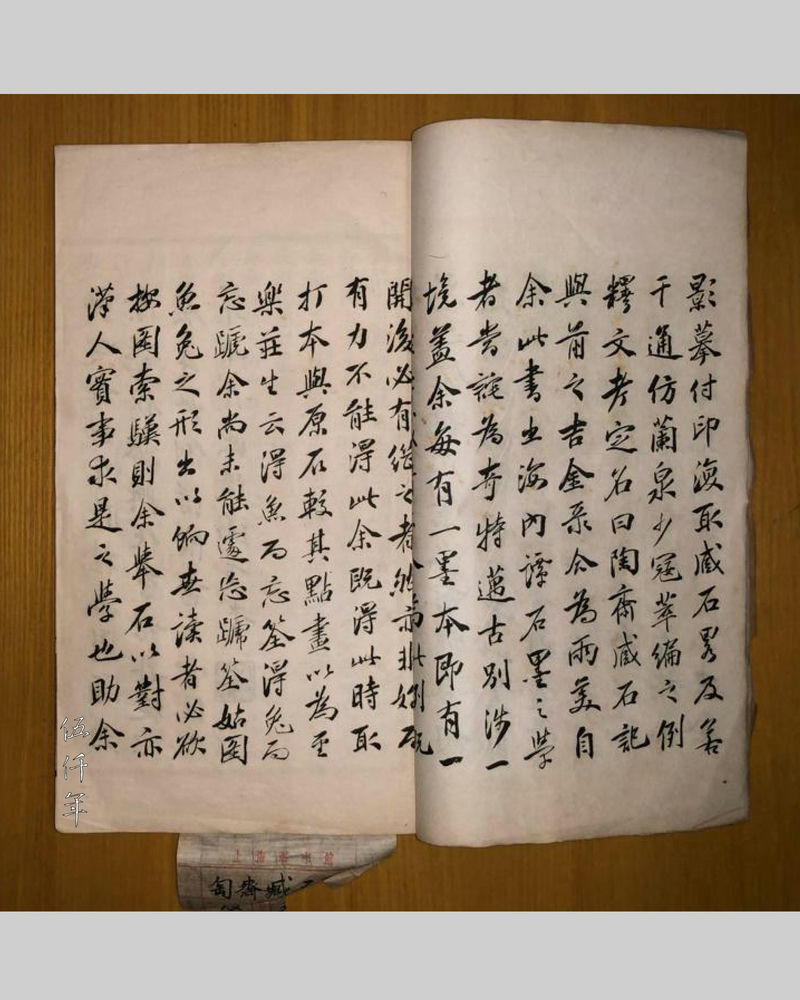

The 16th year of the Kuang-hsü reign also marked the beginning of Tuan Fang’s pursuit of epigraph collecting. In Tuan Fang’s Preface of T’ao-chai ts’ang-shih chi (陶齋藏石記 A Chronicle of Ancient Stones in the Collection of T’ao-chai), he wrote:

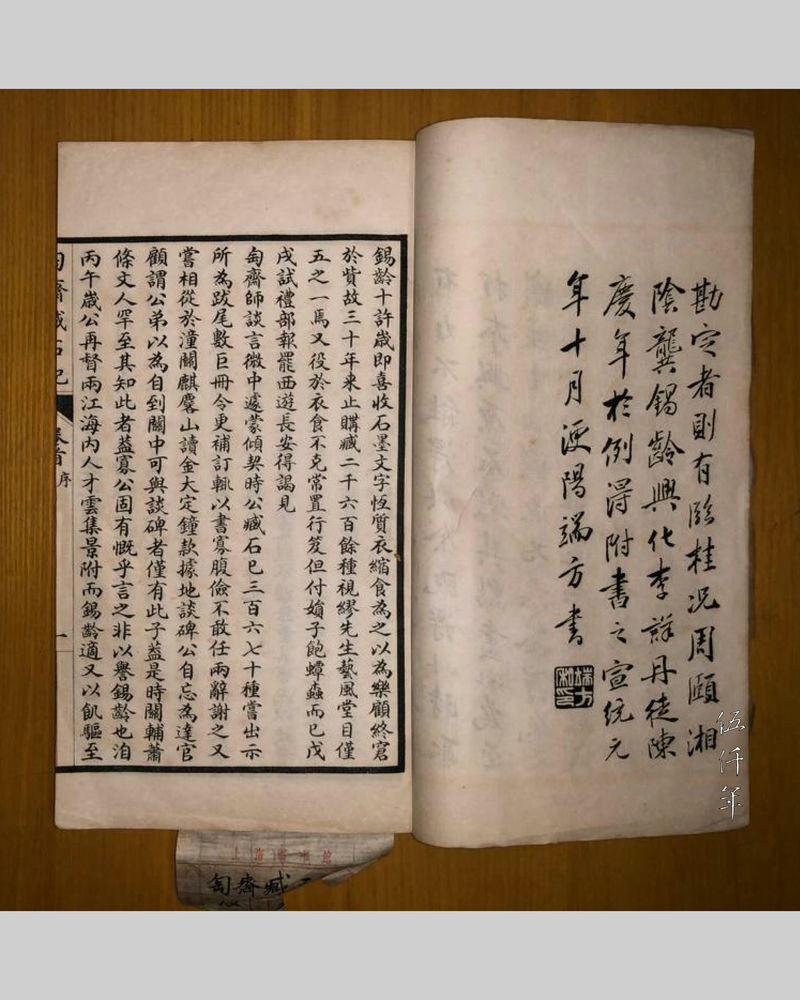

“I have been addicted to this enterprise since my youth. From the time I became an official in Peking, to the time I got appointed to provincial postings, I have tried to select and seek without restraint, and implore myself to solely abide by the evidences of the artefacts. Hence, whenever there are archaeological finds of epigraphs, they will compete to offer me the finds, those epigraphs already discovered, and kept in the collections of old families and eminent surnames, I will also acquire them one by one. As now I prepare these epigraphs for publication…………. Those in charge of inspection and authentication by my side should be mentioned: K’uang Chou-i (况周頤) of Lin-kuei (林桂), Kung Hsi-ling (龔錫齡) of Hsiang-yin (湘陰), Li Ch’ien (李謙) of Hsing-hua (興化) and Ch’en Ch’ing-nien (陳慶年) of Tan-t’u (丹徒). Tuan Fang of Keng-yang (浭陽), October the 1st year of the Hsüan-t’ung reign.”

Title page of T’ao-chai ts’ang-shih chi (陶齋藏石記 A Chronicle of Ancient Stones in the Collection of T’ao-chai)

First page of Preface by Tuan Fang in T’ao-chai ts’ang-shih chi (陶齋藏石記 A Chronicle of Ancient Stones in the Collection of T’ao-chai)

Second and third page of Preface by Tuan Fang in T’ao-chai ts’ang-shih chi (陶齋藏石記 A Chronicle of Ancient Stones in the Collection of T’ao-chai)

Fourth and fifth page of Preface by Tuan Fang in T’ao-chai ts’ang-shih chi (陶齋藏石記 A Chronicle of Ancient Stones in the Collection of T’ao-chai)

Sixth page of Preface by Tuan Fang in T’ao-chai ts’ang-shih chi (陶齋藏石記 A Chronicle of Ancient Stones in the Collection of T’ao-chai)

Thereby we knew it was around the 16th year of the Kuang-hsü reign, with a posting in Peking, Tuan Fang started his interest and ambition in collecting. Collecting is very much reliant on geographic advantages, important artworks and rare treasures have been customarily concentrated in the markets of the capital. T’ao-chai ts’ang shih chi (陶齋藏石記 A Chronicle of Ancient Stones in the Collection of T’ao-chai) was printed in the 1st year of the Hsüan-t’ung reign (1909). Harking back to the 16th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1890), it is exactly twenty years. If there were no such dedication and effort, how could it be possible to build a great collection of his generation?

Tuan Fang had a prominent and successful career in the civil service. He was appointed in succession acting surveillance commissioner of Shensi Province, provincial administration commissioner of Shensi and Honan Provinces, provincial governor of Shensi, Hupeh, Kiangsu and Hunan Provinces, viceroy of Hunan and Hupeh Provinces, viceroy of Kiangsu, Anhwei and Kiangsi Provinces, viceroy of Fukien and Chekiang Provinces, viceroy of Chih-li and viceroy of Szechuan. Although he was a man devoted to antiquities, he was not a man who uncritically held on to the past. The Draft History of Ch’ing (清史稿) chronicled some of his achievements:

“He was dedicated to the invigoration of education. He provided funds for many students to study abroad. After a year, he received an audience with the Emperor, and was promoted to viceroy of Fukien and Chekiang Provinces. Before taking office, he was assigned to visit different Eastern and Western nations to examine their political systems. After he returned, he completed Ou-mei cheng-chi yao-i (歐美政治要義 The Principles of European and American Political Systems) and presented it to the Emperor. This started the consultations to convert to a constitutional monarchy. In the 32nd year, he was appointed viceroy of Kiangsu, Anhwei and Kiangsi Provinces. He built schools, established police units, commissioned warships, trained the army, codified the patrol and search regulations on Yang-tzu Chiang (掦子江). His reputation was ever more exalted.”

Tuan Fang was consecutively appointed to important positions in different provinces. He was devoted to the development of education and the nurturing of a new generation. His deeds benefitted education across the provinces of Kiangsu, Hunan and Hupeh. In the 31st year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1905), he was appointed Minister to Survey the Constitutions of Different Nations (出使各國考察政治大臣), one of the five ministers appointed to The Chinese Constitutional Missions. The others were Tai Hung-tz’u (戴鴻慈 1853-1910), Tai Tse (戴澤 1868-1929), Shang Ch’i-heng (尚其亨 1859-1920) and Li Sheng-to (李盛鐸 1859-1937). They travelled overseas in two groups. Tai Hung-tz’u and Tuan Fang were assigned to visit Japan, America, Britain, France, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Austria-Hungary, Holland, Switzerland and Italy, a total of thirteen nations. Tai Tse, Shang Ch’i-heng and Li Sheng-to were assigned to visit Japan, America, Britain, France and Belgium, a total of five nations.

After they returned to China, they advised the court to adopt the system of constitutional monarchy. They compiled Lieh-kuo cheng-yao (列國政要 The Principles of the Political Systems of Different Nations) in one hundred and thirty three volumes, and Ou-Mei cheng-chih yao-i (歐美政治要義 The Principles of European and American Political Systems) in eighteen chapters. Tai Hung-tz’u presented a memorial to the emperor to conclude the persuasions of the ministers. A portion reads:

“We the Ministers have broadly scrutinized the great movement of the world. We have observed in depth the recent mood in China. If we do not determine the direction of the country, we cannot institute any strategy. There are close to six principles regarding the direction of the country:

1. Across the whole country, officials and citizens should stand in front of the same legal system, to break down all boundaries.

2. The adoptions and decisions regarding important policies in the country should be based on public opinions.

3. Combine the masteries of China and foreign nations, in order to seek security and prosperity for the people and the country.

4. Clarify the institutions of the Court and the Government.

5. Define the jurisdictions of the Central Government and the Local Government.

6. Make public all national policies and government affairs.

The Court can explicitly announce the above six principles as edicts, pledge them to the world and determine the direction of the country. In the region of fifteen to twenty years, constitution can be proclaimed, parliament can be convened, and constitutional monarchy can be implemented.”

This memorial was presented in the 32nd year (1906). Tai Hung-tz’u, Tuan Fang and the other ministers all strove for the future of China, not for the self-interests of one family, nor one clan, nor one party. For today’s Chinese to read this memorial, it must be shocking and frightening. The propositions:

“Across the whole country, officials and citizens should stand in front of the same legal system, to break down all boundaries.

The adoptions and decisions regarding important policies in the country should be based on public opinions.”

These and the other principles are still unattainable in mainland China today.

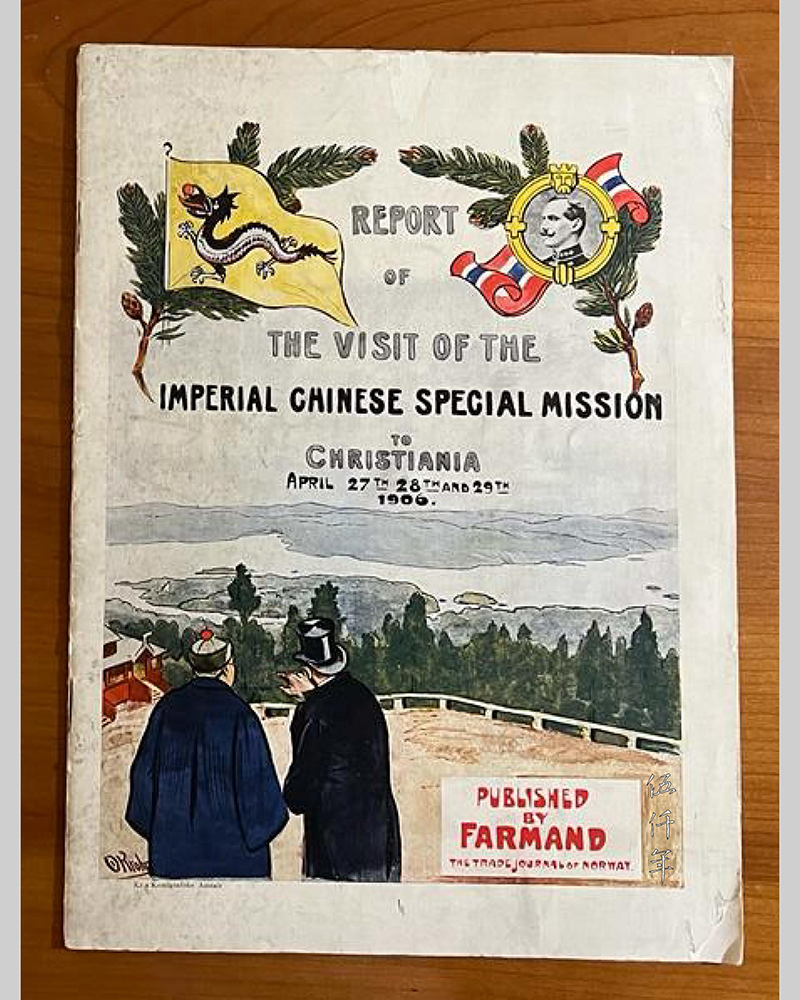

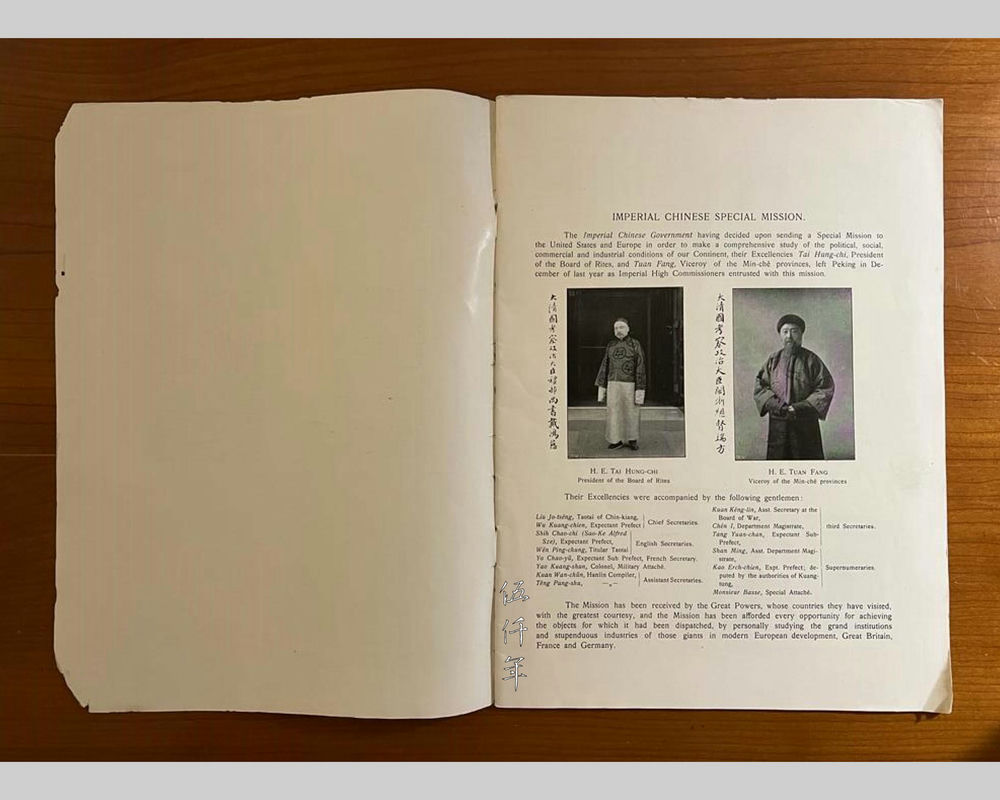

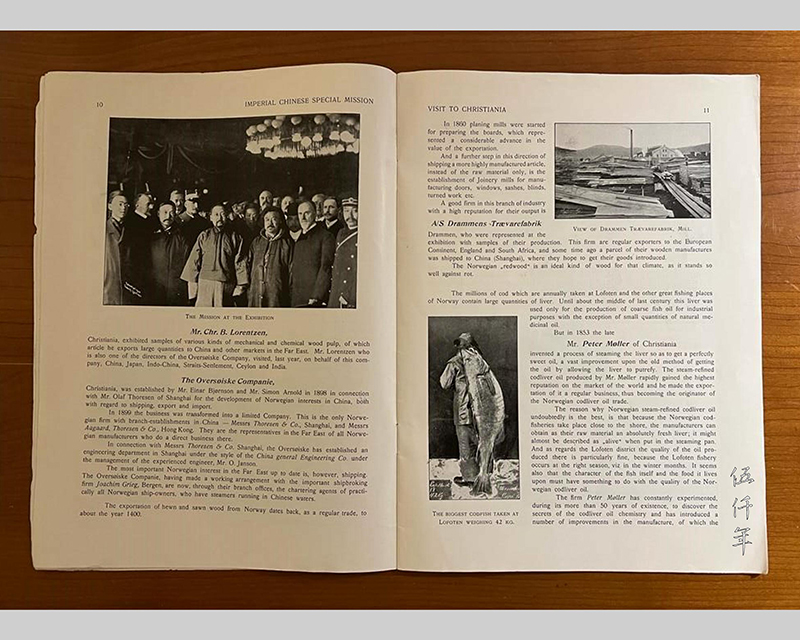

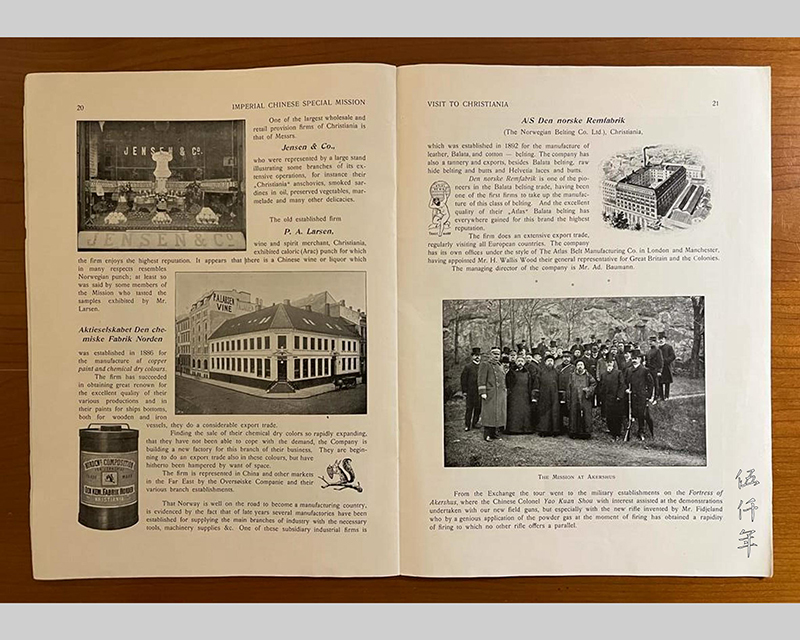

In the Studio of Prunus Ode, there is a copy of the Report of the Visit of the Imperial Chinese Special Mission to Christiania. It is a special edition in English published by Farmand, the trade journal of Norway, about the Mission to Norway on 27th, 28th and 29th April in the 32nd year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1906), headed by Tai Hung-tz’u and Tuan Fang. The capital of Norway was originally named Christiania, it was only changed to Oslo in 1925. This Report may be the only official brochure published during the thirteen nation tour of the Chinese Missions. It is of some importance.

Front cover of Report of the Visit of the Imperial Chinese Special Mission to Christiania

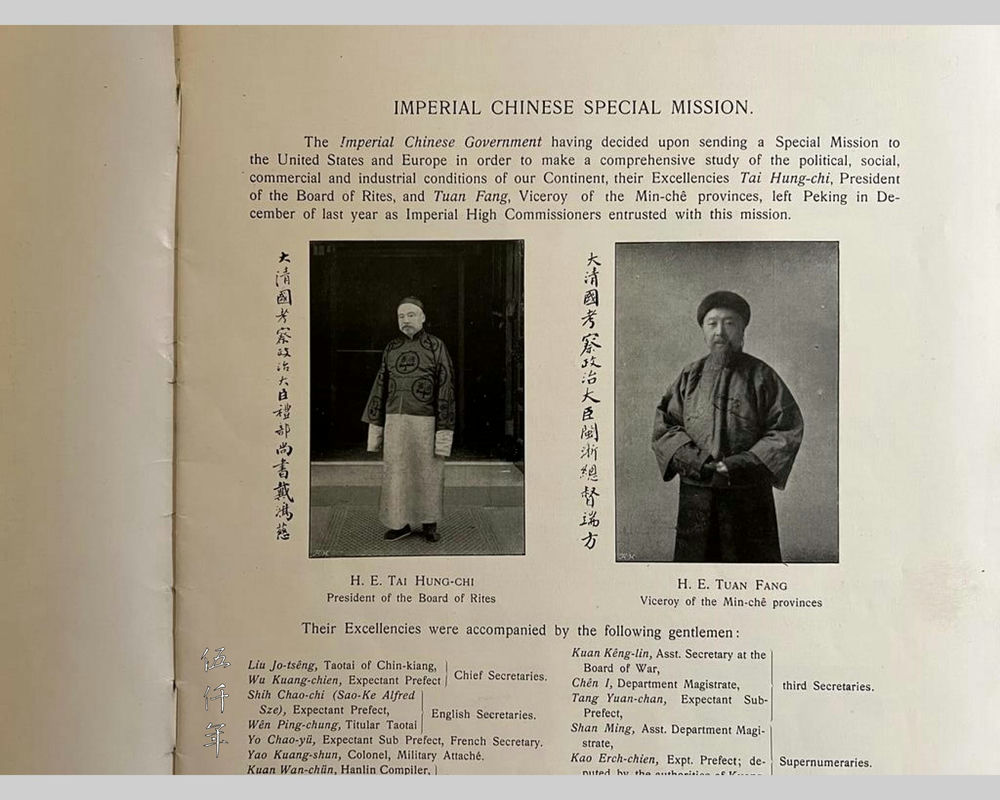

Portraits of Tai Hung-tz’u (戴鴻慈) and Tuan Fang (端方) in the Report of the Visit of the Imperial Chinese Special Mission to Christiania

Enlarged portraits of Tai Hung-tz’u (戴鴻慈) and Tuan Fang (端方) in the Report

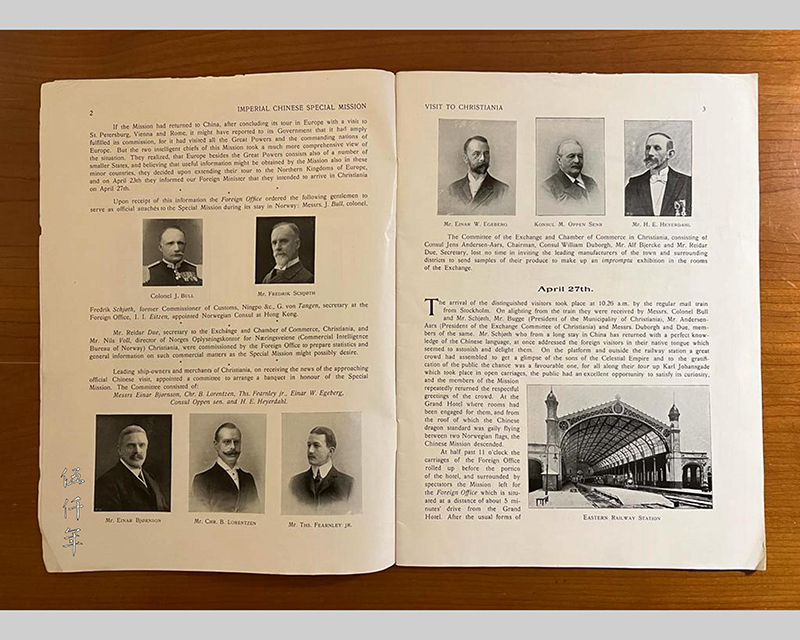

Eminent Norwegians who organized the reception of the Chinese Special Mission in the Report

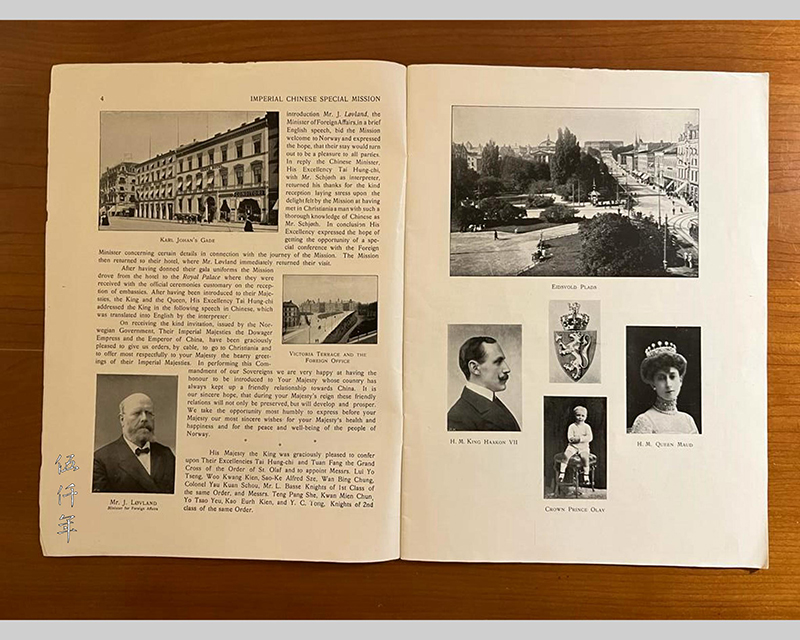

Portraits of H. M. King Haakon VII and H. M. Queen Maud in the Report

The Mission to Norway led by Tai Hung-tz’u and Tuan Fang came about from a last-minute recommendation. The trip was scheduled to take place on 27th April, and the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs was only notified on 23rd April. Although the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs hastily organized the hosting of the Mission, the elaborate hospitality afforded was unmarred. The Report of the Visit of the Imperial Chinese Special Mission to Christiania chronicles the activities of the Mission in great detail. It is possible to deduce with regard to the Missions’ visits to other countries, their schedules are mostly similar. On the first page of the Report, there are two separate portraits of Tai Hung-tz’u and Tuan Fang, below is a list of the fourteen members of the diplomatic corps. Two English secretaries are listed, one of whom is Alfred Sao-ke Sze (施肇基 1877-1958). He later became a prominent diplomat of the Republic of China, serving successively as ambassador to Britain and the United States.

In the morning of 27th Friday, the Mission left Stockholm, Sweden, by train and arrived in Christiania. They visited the Minister of Foreign Affairs Jorgen Lovland, and was received by King Haakon VII and Queen Maud. Tai Hung-tz’u, Tuan Fang and eleven members of the diplomatic corps were decorated by the King. In the afternoon, the Mission visited a sail factory and a textile mill. In the evening, the Prime Minister Christian Michelsen hosted a dinner banquet at his official residence.

Group portrait of the Chinese Special Mission and Norwegian representatives at the trade exhibition on 28th April 1906 in the Report

Enlarged group portrait of the Chinese Special Mission and Norwegian representatives at the trade exhibition on 28th April 1906 in the Report

In the morning of 28th Saturday, the Mission visited Vahlgadens Skole, the largest public primary school, a shipbuilder and a special trade exhibition that introduced twenty six important Norwegian companies. King Haakron VII and Queen Maud hosted a lunch banquet at the Royal Palace. In the afternoon, they visited three museums, and was shown Norwegian artefacts and some Chinese artefacts. Tuan Fang was a specialist of Chinese cultural artefacts, for him to come across such relics beyond the oceans, was no less an emotional affair. In the evening, a number of ship-owners and merchants jointly hosted a dinner banquet at the Grand Hotel.

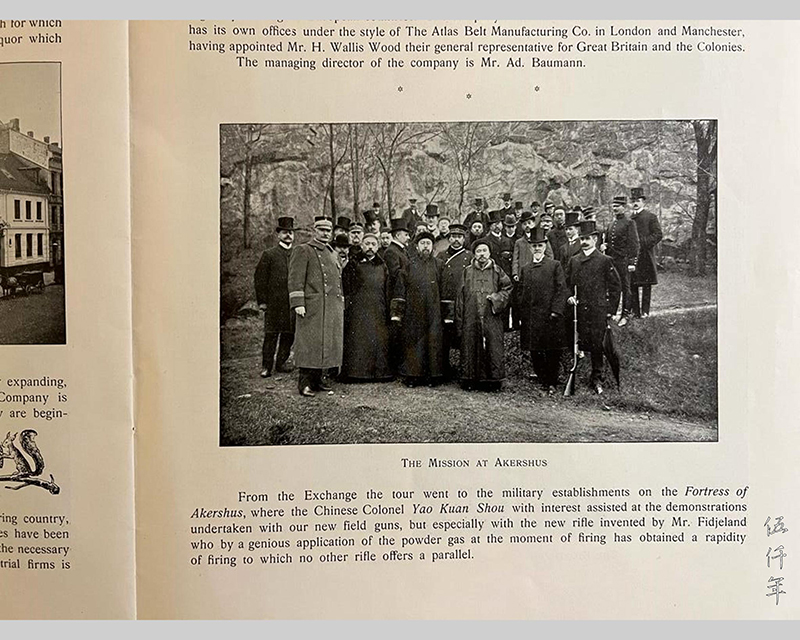

Group portrait of the Chinese Special Mission and Norwegian representatives at the Fortress of Akershus on 28th April 1906 in the Report

Enlarged group portrait of the Chinese Special Mission and Norwegian representatives at the Fortress of Akershus on 28th April 1906 in the Report

At noon on 29th Sunday, the Committee of the Exchange and Chamber of Commerce of Christiania hosted a lunch banquet at the Holmenkollen Tourist Hotel. Afterwards, the Mission proceeded to the National Theatre to attend the performance of Fossegrimen. They left Christiania that evening on a 11:10 train to Copenhagen, Denmark.

Flipping through this Report over a hundred years ago, is akin to being a member of the diplomatic corps, traveling through Christiania again.

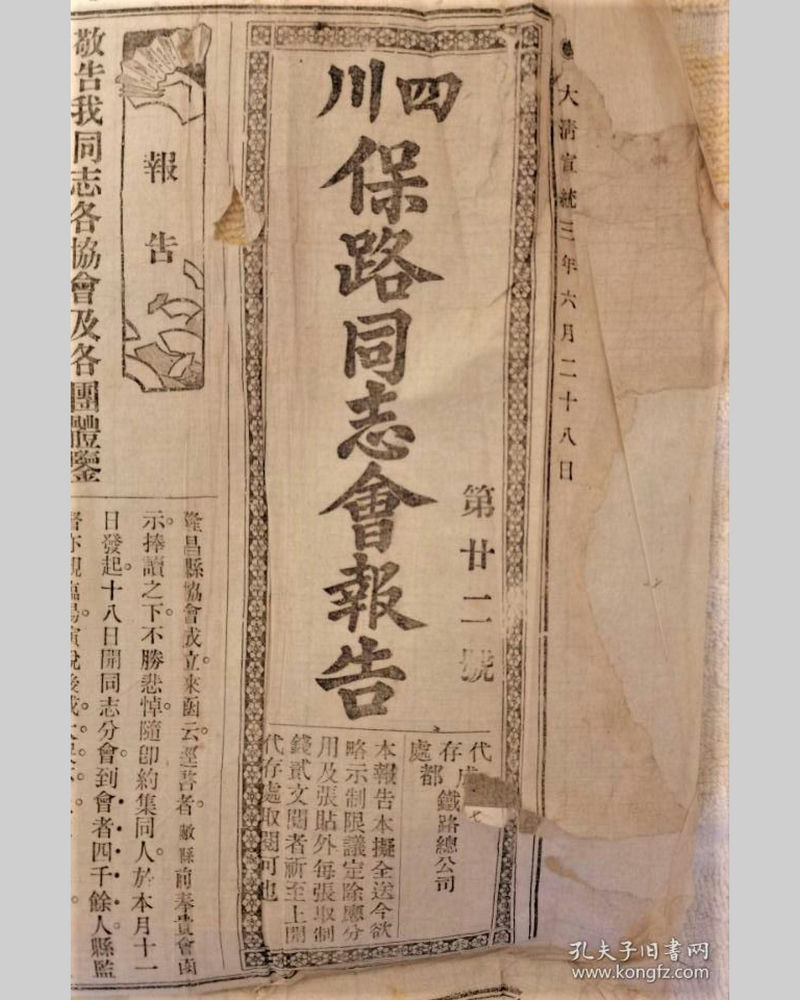

Report from the Association of Szechuan Comrades of Railway Protection (四川保路同志會報告)

In May the 3rd year of the Hsüan-t’ung reign (1911), the Hankow-Szechuan Railway (川漢鐵路) and the Canton-Hankow Railway (粵漢鐵路) were nationalized. People in Szechuan, Hunan, Hupeh and Kwangtung were indignant, especially those in Szechuan who used to own the rights of rail construction and annual dividends, but now only given Hankow-Szechuan Railway stock certificates. At the end of June, Szechuan Pao-lu T’ung-chih Hui (四川保路同志會 Association of Szechuan Comrades of Railway Protection) was established in Ch’eng-tu (成都), strikes by workers and students were organized. Suppression by the Ch’ing government eventually led to bloodshed. Revolutionaries from Chung-kuo T’ung-meng Hui (中國同盟會) also infiltrated the Association, with the intention to direct these activities towards revolution.

In September, Tuan Fang was appointed minister to supervise the Canton-Hankow Railway and the Hankow-Szechuan Railway (督辦粵漢川漢鐡路大臣), as well as viceroy of Szechuan Province. He was given the task to diffuse the situation from further mayhem. On 10th October a pivotal uprising broke out in Wu-ch’ang (武昌起義) that led to more uprisings across the country. On 22nd November, the Szechuan army in Chung-ch’ing (重慶) declared independence, and on 27th November, the Szechuan army in Ch’eng-tu (成都) declared independence. That same day, Tuan Fang led a detachment from the New Army of Hupeh Province into Szechuan Province. When they were traveling through Tzu-chung County (資中縣) at the outskirts of Ch’eng-tu, the troops mutinied and killed Tuan Fang and his brother Tuan Shu-chiung (端叔絅), prefect of Honan Province.

Portrait of Lo Tseng-yü

Portrait of Shen Tseng-chih

As a prominent reformist high official and a connoisseur of epigraphy, the death of Tuan Fang in the wrong place is indeed deeply regrettable. However the distinguished scholar of epigraphy Lo Chen-yü (羅振玉 1866-1940) wrote an article titled Tuan Chung-min Kung ssu-shih chuang (端忠敏公死事狀 An Account of the Death of Mr. Tuan Chung-min). Mr. Tuan Chung-min was the posthumous name of Tuan Fang granted by the emperor. The article clarified that Tuan Fang’s martyrdom was not accidental, it was a conscious and premeditated act, an accomplishment of the Confucian virtues of Benevolence and Righteousness, a preservation of integrity at a time of devastation. Being so, Tuan Fang was killed in the right place after all, and his conduct of martyrdom was befitting of Confucian Orthodoxy. Lo Chen-yü wrote in Tuan Chung-min Kung ssu-shih chuang (端忠敏公死事狀 An Account of the Death of Mr. Tuan Chung-min):

“Mr. Tuan Chung-min had embraced martyrdom in the winter of hsin-hai year (辛亥 1911) during the Hsüan-t’ung reign. At that time, some people in Szechuan remarked that he might not have always cultivated the determination to end his life. He was carefree by nature, and it was a sudden mutiny. I am the few who understand him, but I have nothing to explain. By chia-yin year (甲寅 1914), I returned to China and visited Shen Tseng-chih (沈曾植 1850-1922) in Shanghai. He talked about his martyrdom. The education minister was melancholic and at a loss as he recounted:

‘From what I heard, Mr. Tuan Chung-min had always retained the determination to die. When his detachment was stationed in Tzu-chung County, a Szechuan general named Yü Ta-hung (俞大鴻) came from the city with five hundred soldiers. He was a former subordinate and knew that a mutiny was about to take place. He was most earnest to see him, and said:

Today human hearts change from morning to evening. The place where you are staying is not safe. If you proceed to Ch’eng-tu, or retreat to I-ch’ang (宜昌), the mutiny can be avoided. Although there are only five hundred soldiers in my detachment, this is still adequate to protect you from danger.’

Before Mr. Tuan Chung-min could reply, Ta-hung continued:

The calamity is pressing, please decide quickly.

Mr. Tuan Chung-min was unhurried and thanked Ta-hung. He replied:

In my old age I only know of the command of the Emperor. Wherever the military is stationed there must be petitions to the Court. If I move the troops today, I must have approval from the Court. You must leave, I thank you for your kindness.

Ta-hung understood his wish, he sighed and wept, and bid him farewell. Not more than a day the mutiny took place………

Ta-hung understood that the will of Mr. Tuan Chung-min could not be contravened. He came to Shanghai to tell me this, he could not hold his tears even then. Had he not always cultivated the determination to end his life?’

I was startled when I heard this, I said: This must be revealed to the world and to future generations.”

I have placed the inkstone that belonged to Tuan Fang on my desk. Gazing at it day and night, as if I were in his presence. The years of the Kuang-hsü and Hsüan-t’ung reigns, the grand ambitions of modernization, the epigraph collecting that outshone a whole generation, the passionate sacrifice for Confucian Virtues, are vicissitudes of time the inkstone has been party to. The inkstone has been transfigured into a vessel of remembrance of China past.

Detail of signature and seal of Tuan Fang from the inkrubbing of “Dragon Growl Inkstone”