Wu Hu-fan was a distinguished literatus from Shanghai in the early years of the Republic. He was born in the 20th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1894), and passed away in the 57th year of the Republic (1968). His original name was I-yen, then altered to Wan, also Ch’ien, tzu Yü-chün, T’ung-chuang, Hu-fan, hao Ch’ou-i, Ch’ien-an, and resided at Mei-ching Shu-wu. He was a native of Wu-hsien, Kiangsu province. He was proficient in poetry and tz’u, accomplished in calligraphy and painting, skilled in connoisseurship, and prolific in collecting. His painting enjoyed equal esteem as those by Wu Cheng (吳徵 1878-1949), Wu Hua-yüan (吳華源 1893-1972) and Feng Ch’ao-jan (馮超然 1882-1954). His publication is titled Ning-sung tz’u-hen (Tz’u Tracings of Sung Indulgences 佞宋詞痕).

Portraits of Mr.Wu Hu-fan and his first wife Ms. P’an Ching-shu. Photograph courtesy Artron

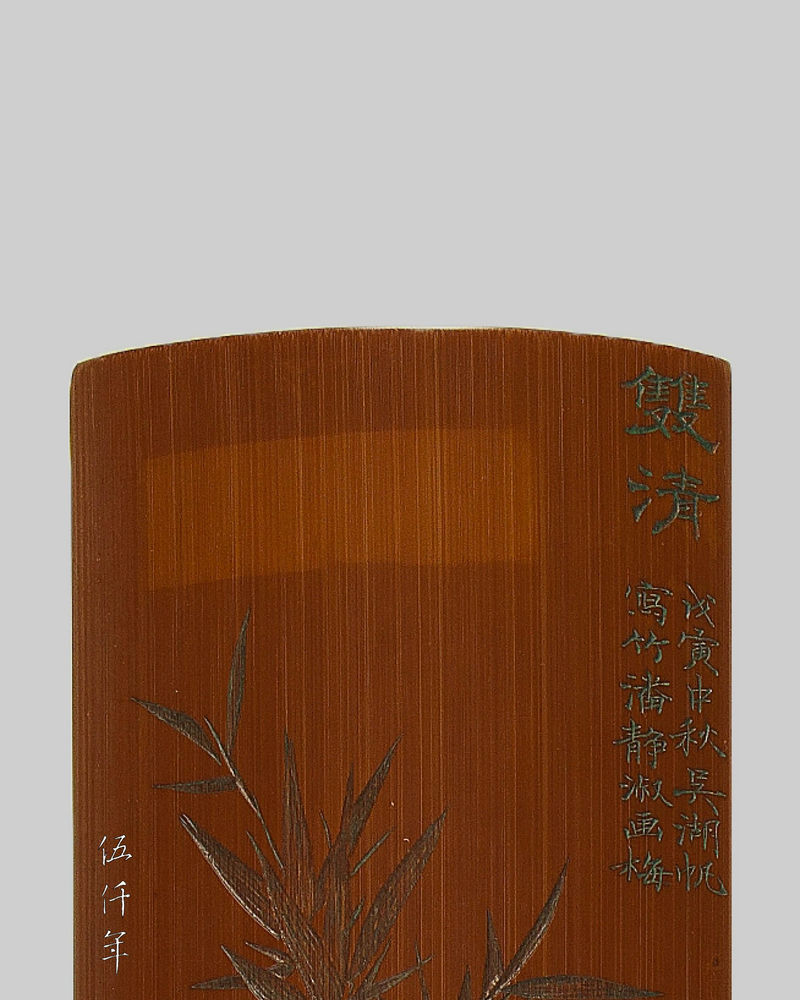

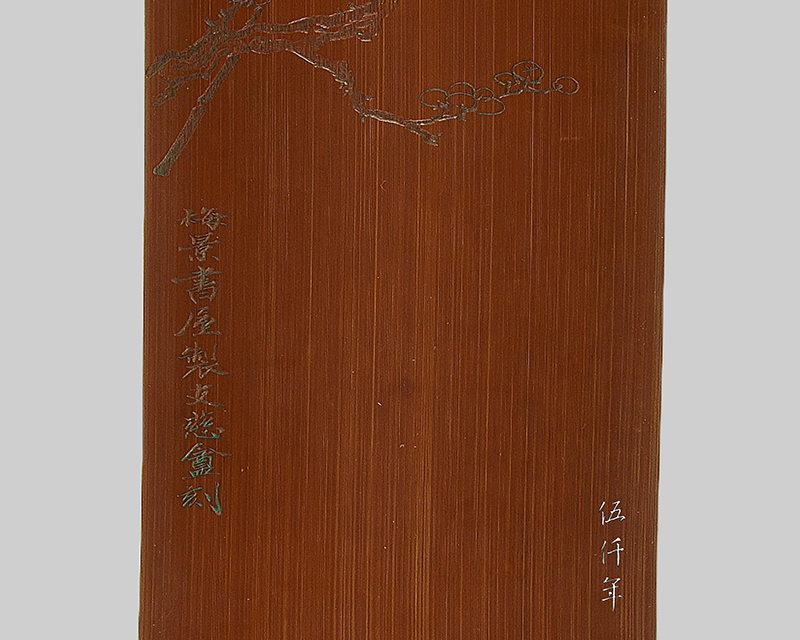

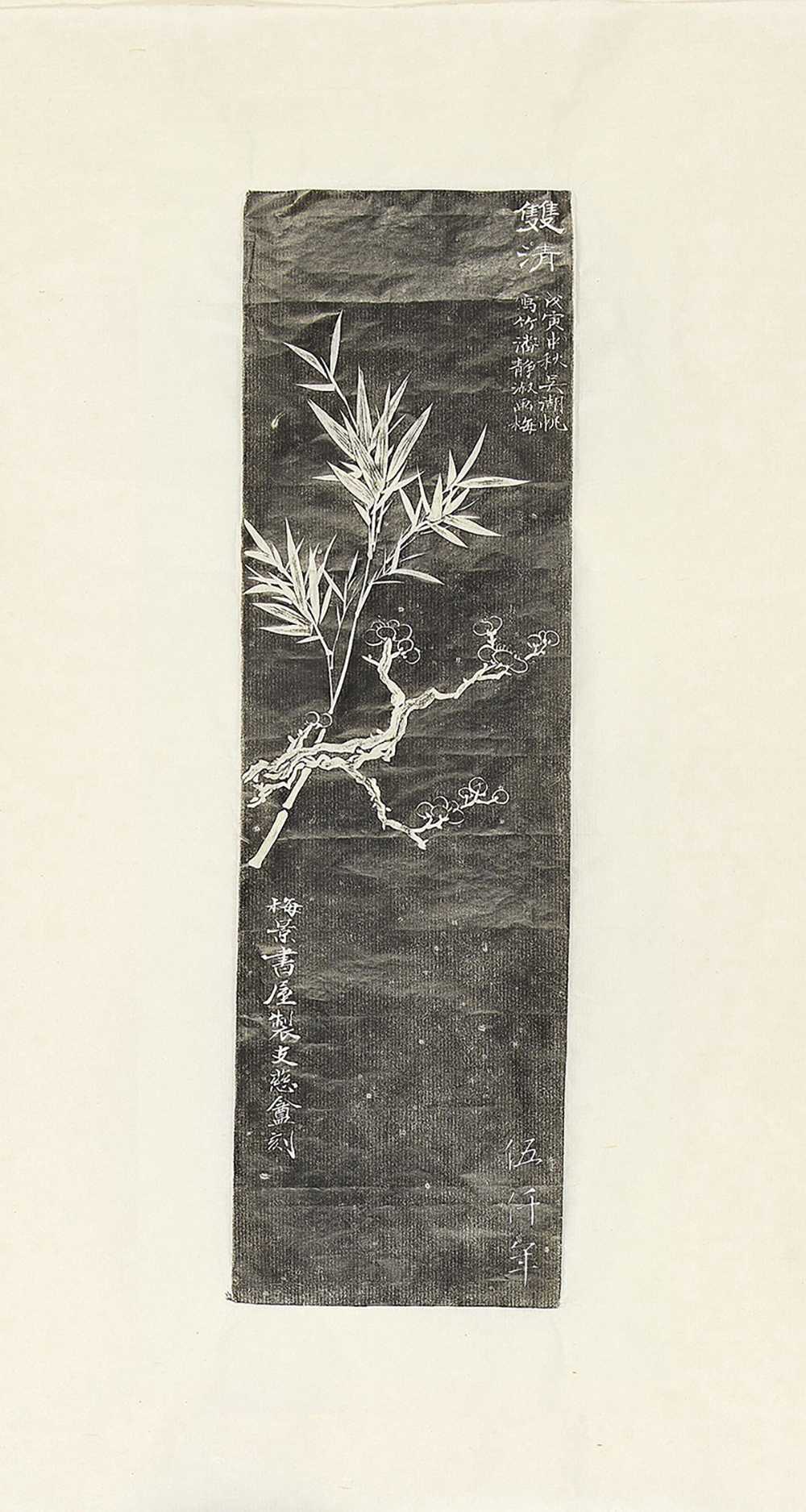

In the collection of the Studio of Prunus Ode, there is a wrist rest made of bamboo, engraved with a painting of prunus and bamboo by Wu Hu-fan and his wife P’an Ching-shu (潘靜淑), the carving was by the distinguished engraver Chih Tz’u-an (支慈盦 1903-1974). On the upper right side, two words were engraved in clerical script : “Shuang-ch’ing (Unworldly Duo 雙清)”, the others in regular script: “Wu-yin Chung-ch’iu, Wu Hu-fan hsieh ch’u, P’an Ching-shu hua mei (During the Autumn Moon Festival in the year of wu-yin, Wu Hu-fan drew the bamboo, P’an Ching-shu painted the prunus)”. On the lower left side, some words in regular script: “Mei-ching Shu-wu chih, Chih Tz’u-an k’ei (Made by Mei-ching Shu-wu, engraved by Chih Tz’u-an. 梅景書屋製,支慈盦刻)”.

Wrist rest from Mei-ching Shu-wu. Bamboo by Wu Hu-fan, prunus by P’an Ching-shu , engraved by Chih Tz’u-an.The Studio of Prunus Ode Collection

Detail of the upper part of the wrist rest from Mei-ching Shu-wu. Bamboo by Wu Hu-fan, prunus by P’an Ching-shu , engraved by Chih Tz’u-an

Detail of the lower part of the wrist rest from Mei-ching Shu-wu. Bamboo by Wu Hu-fan, prunus by P’an Ching- shu , engraved by Chih Tz’u-an

Ink rubbing of wrist rest from Mei-ching Shu-wu. Bamboo by Wu Hu-fan, prunus by P’an Ching-shu, both engraved by Chih Tz’u-an.The Studio of Prunus Ode Collection

The year wu-yin was the 27th year of the Republic (1938), Wu Hu-fan was aged forty five, P’an Ching-shu was aged forty seven. The Autumn Moon Festival of the 27th year of the Republic fell on the eighth of October of the Gregorian calendar. P’an Ching-shu passed away in the summer of the 28th year of the Republic (1939), when she worked on this wrist rest, she was only ten months away from her death.

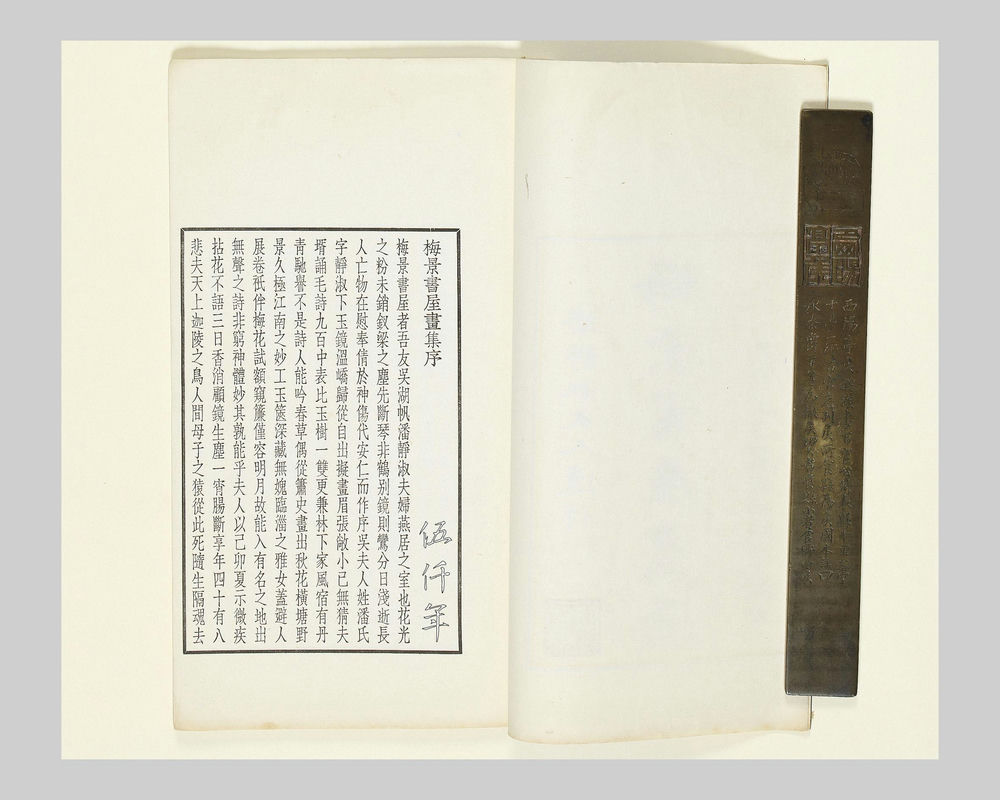

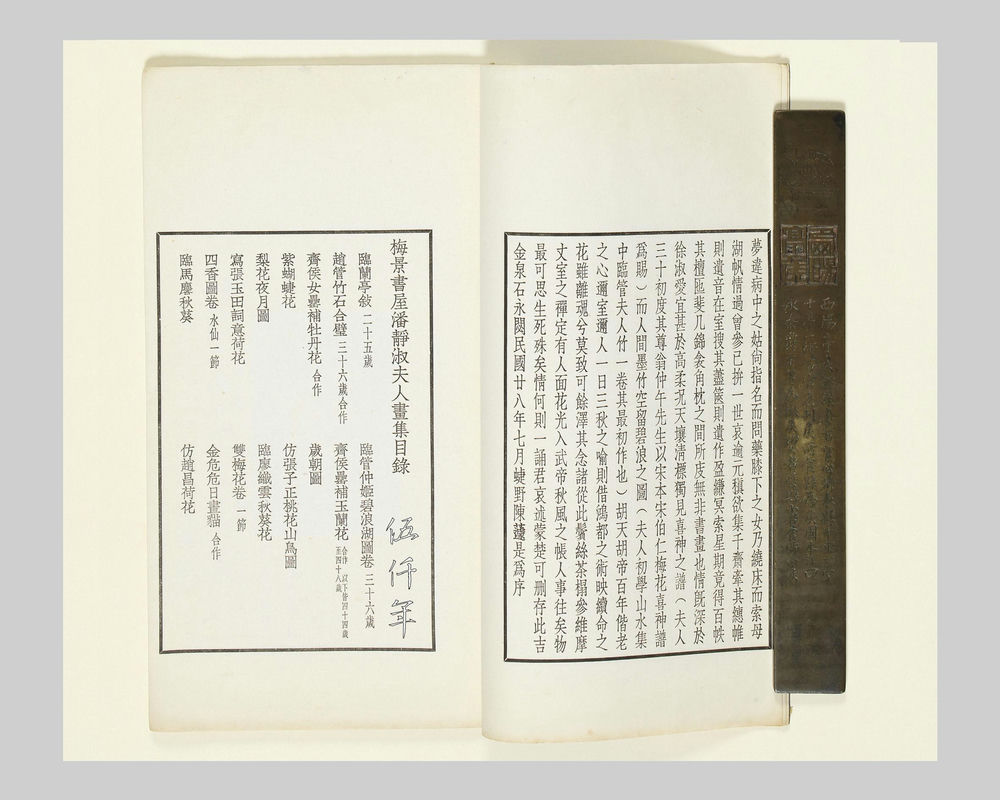

First page of the preface from The Paintings of Mei-ching Shu-wu, compiled by Wu Hu-fan. The Studio of Prunus Ode Collection

Second page of the preface from The Paintings of Mei-ching Shu-wu, compiled by Wu Hu-fan. The Studio of Prunus Ode Collection

“Mei-ching Shu-wu” in the lower left, was a name that alluded to two of the rarest art pieces in the collection of Wu Hu-fan and P’an Ching-shu. Mei referred to the sole existing copy of the book Mei-hua hsi-shen-p’u (梅花喜神譜) printed in the Southern Sung dynasty (1127-1279). Ching referred to a calligraphy album of poetry To-ching-lou shih t’ieh (多景樓詩帖) by Mi Fei (米芾 1051-1107) of the Sung dynasty (960-1279). A Chinese character was selected from each of the two pieces to incorporate this name.

Portrait of Mr. Chih Tz’u-an. Photograph courtesy Han-fen Lou

Chih Tz’u-an (1904-1974) was a master of bamboo engraving, his original name was Ch’ien, tzu Nan-ts’un, hao Nan-ts’un Chü-shih, Jan-hsiang Kuan-chu, native of Wu-hsien, Kiangsu province. The late art connoisseur in mainland China Wang Shih-hsiang (王世襄 1914-2009), in his article A Concise History of Bamboo Engraving, commented: “In late nineteenth century, the art of bamboo engraving steadily declined, not until the beginning of this century (20th) with the appearance of Mr. Chin Hsi-yai (金西厓 1890-1979) and Chih Tz’u-an, did the art of bamboo engraving manage to develop again towards new directions”. Chu Te-i (褚德彝 1871-1942) wrote in Chu-jen hsü-lu (A Supplement Record of the Artists of Bamboo Engraving 竹人續錄): “Tz’u-an in the field of bamboo engraving, is indeed today’s equivalent of Hsi-huang (希黃) and Sung-lin (松麟).” Hsi-huang was Chang Hsi-huang (張希黃 circa 17th c), Sung-lin was Chu Sung-lin (朱松麟 circa 17th c), they were both masters of bamboo engraving in the later part of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), one could recognize the unreserved tribute paid by Chu Te-I.

The names of wrist rest in Chinese characters are arm rest (臂擱), arm repose (臂閣), rest of arm (擱臂), treasured repose (秘閣), hand pillow (手枕) and wrist pillow (腕枕). The ancients wrote and painted with the brush, to guard against the staining of ink on hand and sleeve, they created this instrument. They were made of bamboo, stone, jade, porcelain, ivory and other materials, however bamboo was regarded as superior to others, because the substance was humble, while light and convenient to use.

Why did a refined desk instrument made by Mei-ching Shu-wu for the purpose of self amusement, dislodged into this crass marketplace? In the 38th year of the Republic (1949), mainland China fell to the communists, Wu Hu-fan remained there and did not flee, he subsequently went through many terrifying waves of political purges, until he was mentally and physically drained, in order to save himself, many times over he was forced to proclaim his political loyalty. In the 46th year of the Republic (1957), he composed a tz’u poem To the tune Shui lung yin, with these lines: “ Liquidate those against the party, lay siege to the rightists.” In the 49th year of the Republic (1960), he painted a picture titled: Hoist the Red Flag Atop Mount Everest. When the Cultural Revolution broke out (1966), even so he could not escape the coming calamity. Through the years, the death of Wu Hu-fan has been widely speculated overseas. I once read an article The Death of Wu Hu-fan by Mr. Wan Chün-ch’ao (萬君超先生), he recounted the tragedy in great detail. Hence despite its length, I hereby quote part of his article. It reads:

“In October 1965, Wu Hu-fan had a stroke and moved into the Shanghai Hua-tung Hospital, during this time he was looked after in turn by the two ladies Ku Pao-chen (顧抱真) and Ku Feng-hsien (顧鳳仙) . After the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution, on the twenty sixth of December 1966, Wu Hu-fan was expelled from the hospital by the red guards there, for he was identified as a ‘landlord.’ He returned to his house in Sung-shan Road to continue his recovery from illness, but his health steadily deteriorated. Ku Feng-hsien later recalled: ‘ During the time when Mr. Wu was ill, hospitalized, and before his death, not one relative or friend expressed concern, nor visited him.’ This meant that from October 1965 when he moved into the hospital, to the seventh of July 1968 when he died, in a period of two years and nine months, Wu Hu-fan was already ‘forgotten’ or ‘abandoned’ by everyone. However, from the inscriptions on the existing calligraphy and paintings by Wu Hu-fan, there were a few people who secretively maintained some kind of communications.

On the seventh of July 1968, Wu Hu-fan passed away in his house. The Shanghai Chinese Painting Academy received a telephone call in the afternoon on that day ( it was unclear who called), and was notified the news of Wu’s death. The head of the Academy Yang Cheng-shin (楊正新) asked Lu I-fei (陸一飛) to go to Wu’s house to make the necessary arrangements, since Lu was a student of Wu. Under the extraordinary political environment of the time, Lu was quite worried, fearing that some people might gossip. But all the other students of Wu Hu-fan were already locked up in ‘cowsheds’, and no one could assist Lu over these matters. So Lu applied to the Academy for assistance, hoping that it could send another person to accompany him, but none was willing to go. Eventually the Academy sent an activist in the political purges by the surname of Hsü (徐), who was a student at the East China University of Political Science and Law, and together they went to Wu’s house at Number 88 Sung-shan Road.

When the two arrived at Wu’s house, they saw Ku Pao-chen sitting by the door outside the room, and was nearly in a state of unconsciousness. Mei-ching Shu-wu had gone through multiple house raids by the red guards, it was already in utter chaos, and there was nothing on the four walls. The body of Wu Hu-fan was on a small mobile bed similar to those in a hospital, he was wearing a set of white underwear and shorts, without any socks, and a tube for liquid feeding was inserted into his esophagus. When Lu and Hsü saw this picture, the first thing they did was to find the family members of Wu Hu-fan. Wu lived on the second floor, the first floor was occupied by a household of the surname Hsü (許), the third floor resided the family of 000. (the author referred to this identity incognito, as the person was highly likely to be a close family member). Lu wrote in the testimonial material: ‘probably everyone wanted to draw a political demarcation line, nobody came out from their doors. I immediately went up to the third floor, no one answered the door. Only the nanny Feng-hsien was standing on the landing of the staircase, seemingly we were the only one left to deal with the body.’ Later on, Hsü who was sent by the Academy, felt that the situation was quite awkward, and taking advantage when Lu was making a telephone call to the crematorium, he slipped away. Lu made the call across the road from a public phone, but the crematorium refused to send a car to pick up the body, on the ground that the deceased was a problematic person (a class enemy of the people in the guise of monster and demon), and such a person was not their business. Lu I-fei repeated the request, and said that the weather was sizzling hot, to leave the body in the house would not be palatable. Eventually, about time, a three wheel transportation cart for corpses was sent. Lu I-fei and Ku Feng-hsien pulled out the feeding tube from Wu’s esophagus (for it had to be returned to Shanghai Hua-tung Hospital), then Lu I-fei buckled up two of Wu’s buttons, fastened his belt, and saw a pair of grey socks by the bed which he hoped to put them on for him. But the workers from the crematorium were visibly impatient, and asked Lu what was his relationship with the dead person, why had he not drawn the political demarcation line! Not permitting any more delay, they bundled the body with a white cloth and carried it away. Lu I-fei followed them and walked down the staircase, watched as they loaded the body onto the cart, asked clearly for its serial number, and was told that it would be sent for cremation the next day. After the cart drove away, Lu returned to the second floor, explained briefly to Ku Pao-chen the formality of the crematorium, offered a few words of comfort, and returned to the Academy to report on the affair.

The cremains of Wu Hu-fan was not preserved afterwards, its whereabouts unknown. A year later, after years of excrutiating torment, suffering and humiliation, in grievance Ku Pao-chen died of cerebral hemorrhage. She was aged fifty four, nor was her cremains preserved. Many years later, her niece Ku Pai-p’ing (顧白萍) constructed a cenotaph at the Heng-ching Public Cemetry in her native county of Wu-hsien, Kiangsu province, on the tombstone these words were engraved: The tomb of Ku Pao-chen, wife of the painter Wu Hu-fan.

The famous elder poet and scholar Mao Kuang-sheng (冒廣生) in Shanghai once inscribed a poem on the collective pictorial work Autumn Woods and Lofty Scholar by Chang Ta-ch’ien (張大千), P’u Hsin-yü (溥心畬) and Wu Hu-fan, dedicated to Lu Tan-lin (陸丹林). Two lines in the poem are: ‘Chang in the south, P’u in the north, Wu in the east, adulation for the trio, is all over.’ At that time, the high esteems enjoyed by the painters Chang Ta-ch’ien, P’u Hsin-yü and Wu Hu-fan were almost identical, but the destinies of their later years were totally different. The tragic denouement of the life of Wu Hu-fan, induces incessant lamentation for future generations. (The author compared Wu’s fate with those of Chang Ta-ch’ien and P’u Hsin-yü, both left mainland China in 1949 when the communists took over. They both spent their later years in Taiwan.)”

As my modest collection harbours a former artefact from Mei-ching Shu-wu, every time I fetch it for perusal, I am persistently reminded of the intense violence of the house raids by the red guards, and the cruel death of Wu Hu-fan. In the end it is difficult to nurture any self indulgent pleasure, and whatever exquisite feeling there can be is totally lost. I have recorded a segment of The Death of Wu Hu-fan by Mr. Wan Chun-ch’ao, in memoriam Wu Hu-fan.

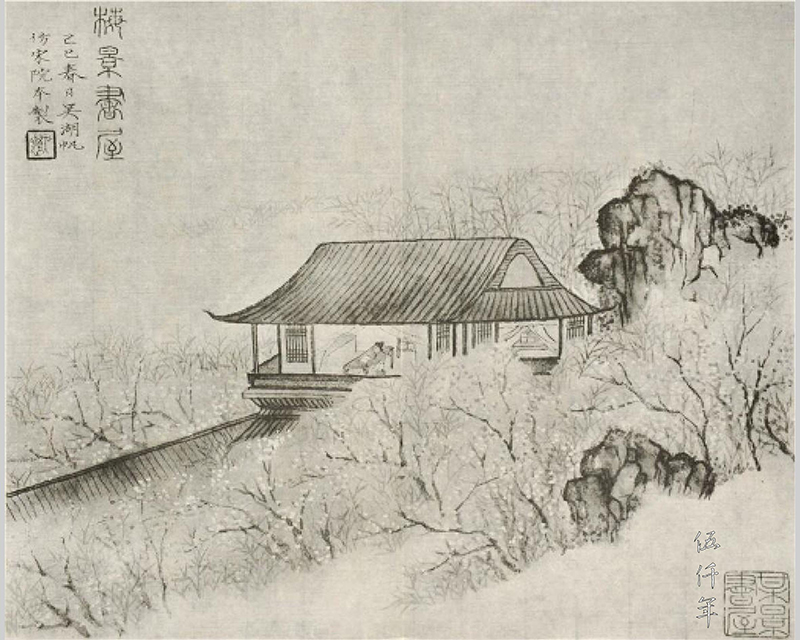

Wu Hu-fan painted a view of Mei-ching Shu-wu in 1929