The custom of making teapots or wine ewers by literati arose and spread in the Ch’ing dynasty. Yet it was also during the Ch’ing when this custom met its demise. The Taiping Rebellion broke out in the 1st year of the Hsien-feng reign (咸豐 1851), the enterprise of craftsmanship was thence ravaged and ruined. Those who made teapots or wine ewers afterwards barely retained the residual spirit, and pieces from past decades have little notable quality.

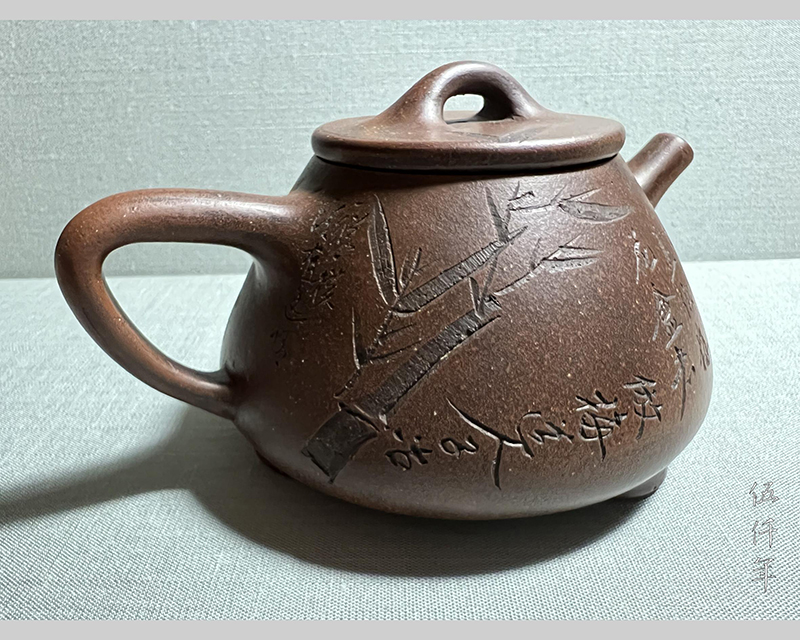

Harking back, there was Shen Ts’un-chou (沈存周) in the Shun-chih reign (順治 1643-1661), Ch’en Hung-shou (陳鴻壽 1768-1822) in the Chia-ch’ing reign (嘉慶 1796-1820), Chü Ying-shao (瞿應紹 1779-1850) and Chu Chien (朱堅 b. 1790) in the Tao-kuang reign (道光 1820-1850). Shen and Ch’en created many new forms of teapots and wine ewers, they engraved literary writings, poems and seal impressions on them. Chü and Chu further engraved pictorial works on the sides of the teapots and wine ewers. Works by these artists achieved a synthesis of imaginative power, literary finesse and artistic enchantments, sufficient to touch the hearts of generations to come. Chü Ying-shao pioneered the application of pictorial works. The purity, effortlessness and elegance of his teapots instituted a unique style. Connoisseurs have prized them as magnificent treasures. We hereby present the Incised Bamboo Clay Teapot by Chü Ying-shao for our audience, a divine pleasure for kindred souls.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

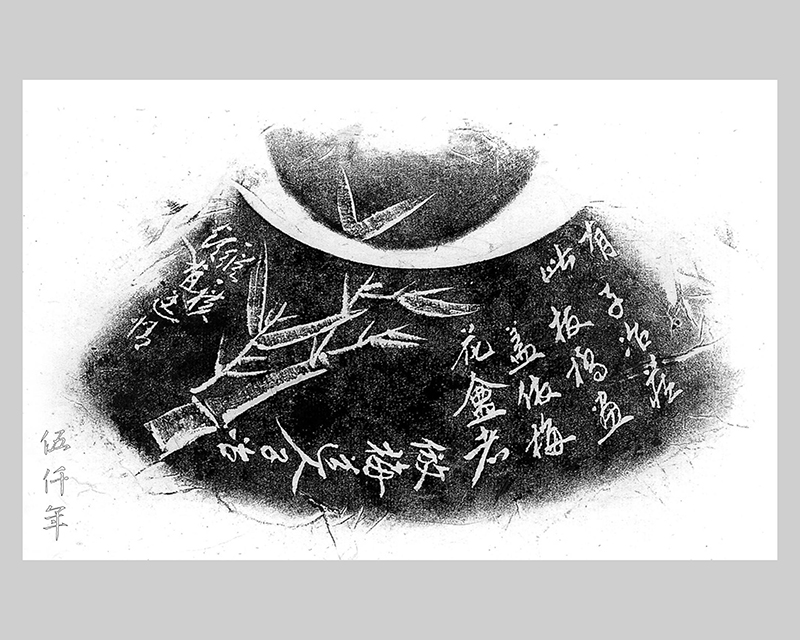

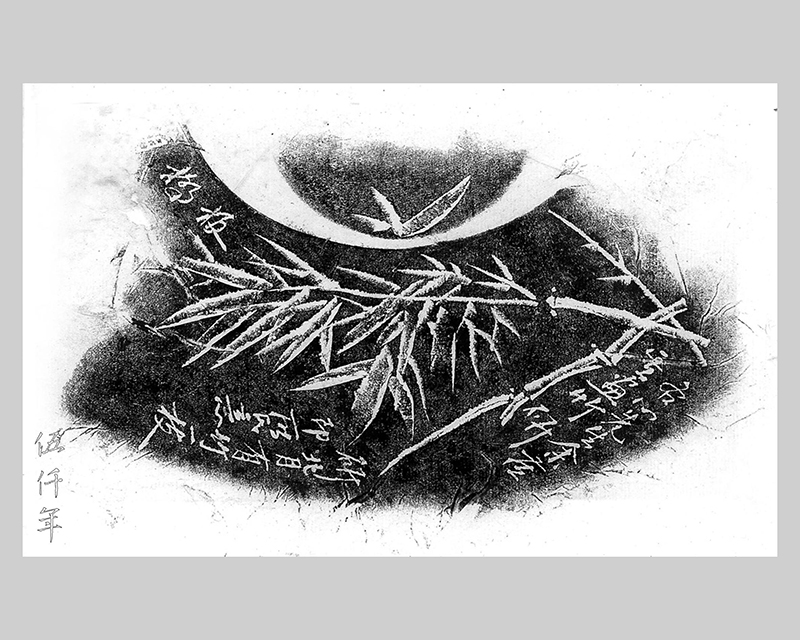

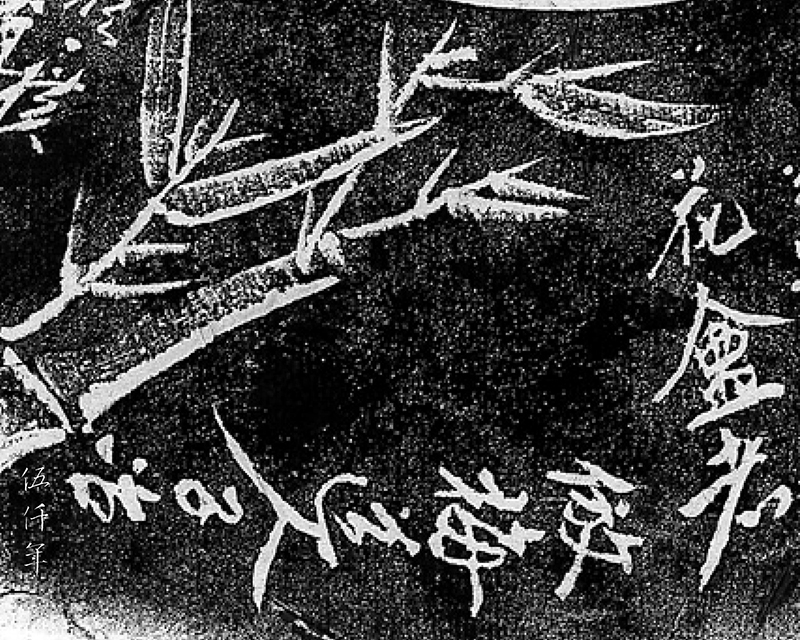

Detail of the incised bamboo clay teapot by Ch’ü Ying-shao in the Studio of Prunus Ode

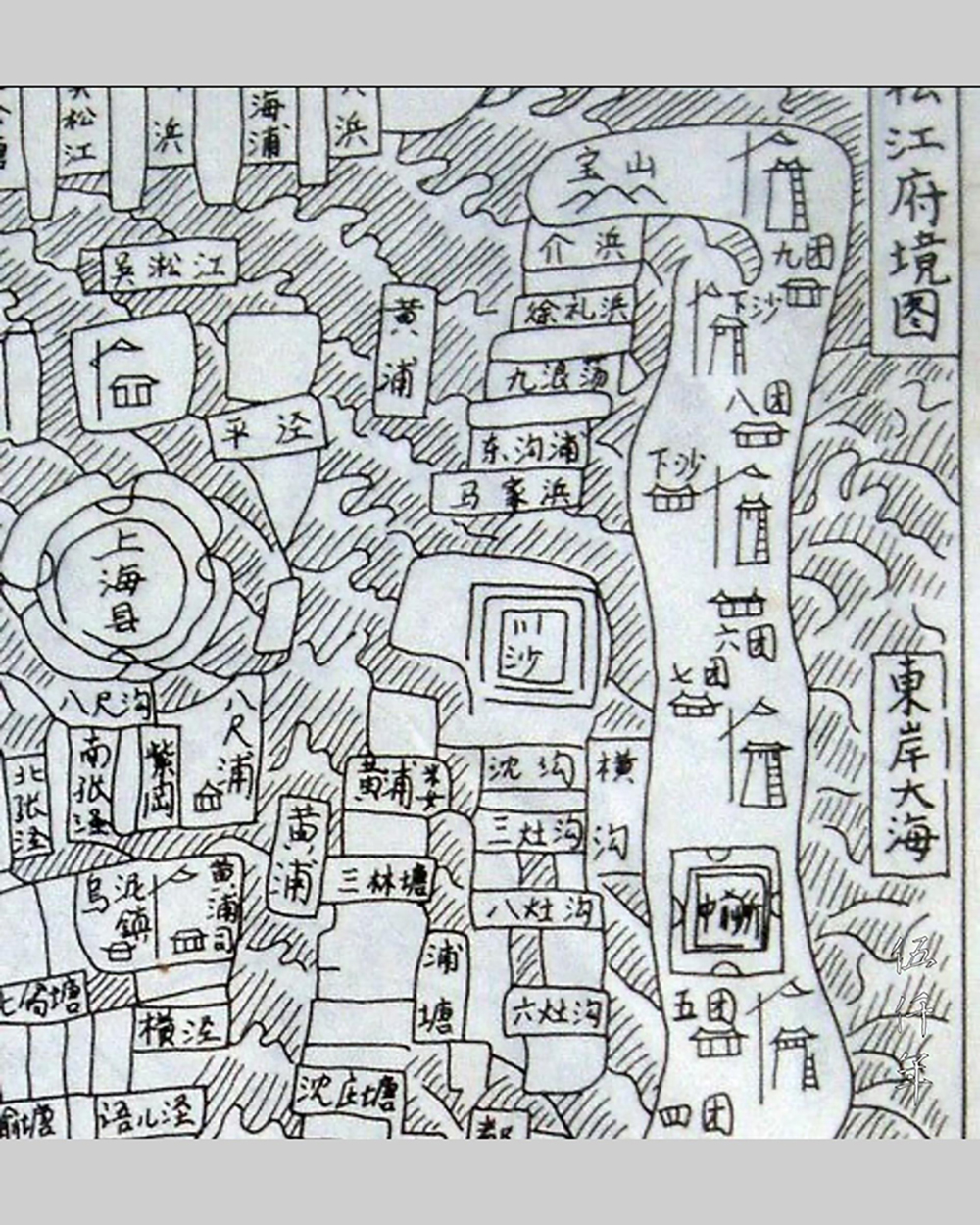

During the reigns of Chia-ch’ing (嘉慶 1796-1820) and Tao-kuang (道光 1821-1850), there lived in Shanghai a refined and unworldly scholar. He attained the rank of hsiu-ts’ai (秀才 cultivated talent) through county examination, and was particularly fond of making clay teapots. His family name was Ch’ü and his first name was Ying-shao (瞿應紹). Those with the surname Ch’ü (瞿) are acknowledged to be descendents of Ch’ü Chuang (瞿莊), adjutant to Ssu-ma Yüeh (司馬越) or Prince of Tung-hai (東海王) from the Chin dynasty (晉朝 266-420). Ch’ü Chuang was a native of Po-ling (博陵), now known as Li County (蠡縣) in Hupeh Province. By the end of the reign of Ching-k’ang (靖康 1126-1127) in the Northern Sung dynasty (北宋 960-1127), the descendent of Ch’ü Chuang, adjutant Ch’ü Kuei (瞿檜), accompanied Chao Kou (趙構) or Emperor Kao-tsung (高宗) during the southward relocation of the imperial court. The whole Ch’ü clan migrated to Shanghai, and settled in Ho-sha (鶴沙), now known as Hsia-sha County (下沙) in the P’u-tung District of Shanghai. The word ho (鶴) means crane. Ho-sha acquired this name because it was once the breeding ground of the red-crowned crane.

During the Sung and Yuan Dynasties, the Ch’ü clan administered salt flats in Ho-sha, becoming the richest family in Sung-chiang Prefecture, owning 7,300 hectares of land, and the finest private garden in Southern China. In early Ming dynasty, the wealth of the Ch’ü clan was confiscated and many members put to death by Chu Yüan-chang (朱元璋 1328-1398) or Emperor Hung-wu (洪武帝).

Chang Tan (張澹), an intimate friend of Ch’ü Ying-shao, described his nature as being disposed towards filial piety. These are certainly not insincere words. Ch’ü Ying-shao would sometimes impress the seals “Ho-sha” (鶴沙) or “Po-ling po-tzu” (博陵伯子 Descendent of the Duke of Po-ling) on his own calligraphy and paintings. They were meant to trace the origin of his family and to reminisce the legend of his ancestors. The Ch’ü clan lived together in Ho-sha for generations, it was probable that the house lived in by Ch’ü Ying-shao once stood there. Even though he might have subsequently moved out of Ho-sha, the seal impression of Ho-sha reminded us that this was the place his heart long lingered.

Map of Sung-chiang Prefecture showing location of Hsia-sha, also known as Ho-sha

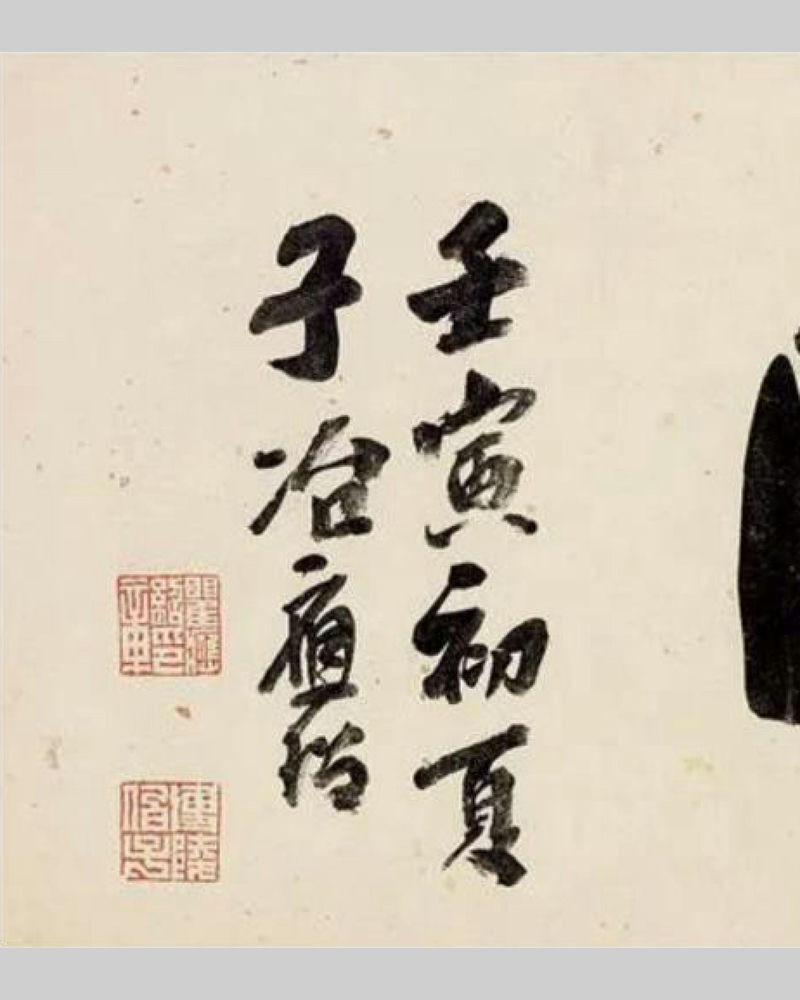

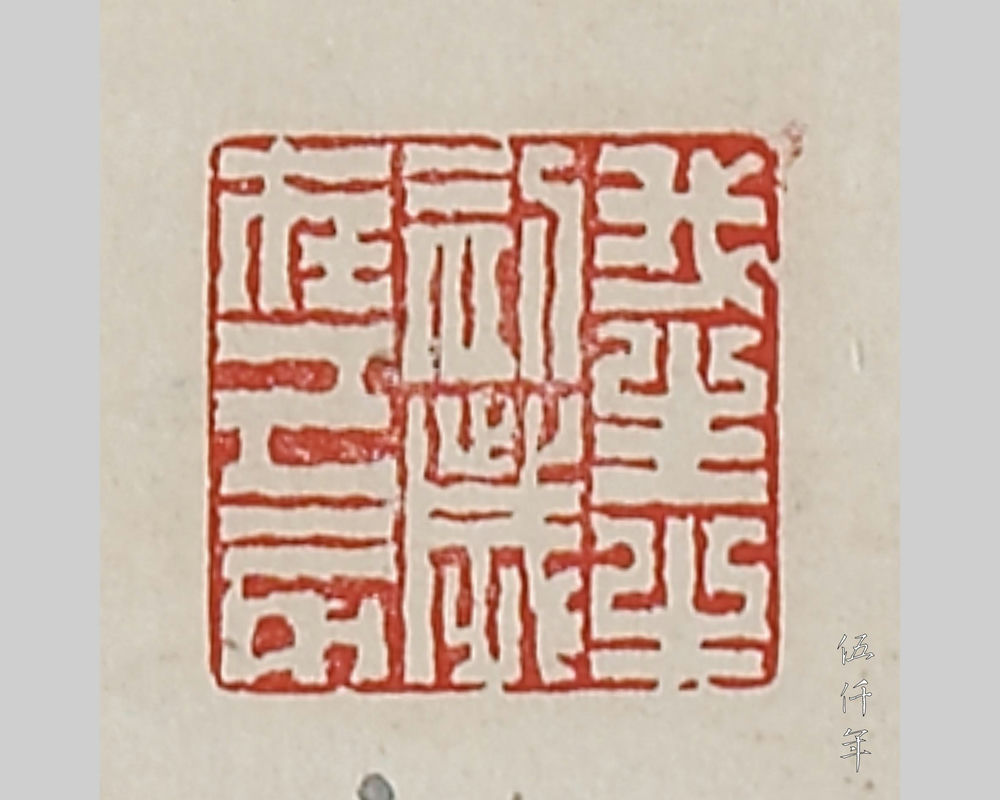

The seal “Po-ling po-tzu” (博陵伯子 Descendent of the Duke of Po-ling) was impressed on the lower left of the title page of Ch’u-ch’i Painting Album by Ch’ ü Ying-shao

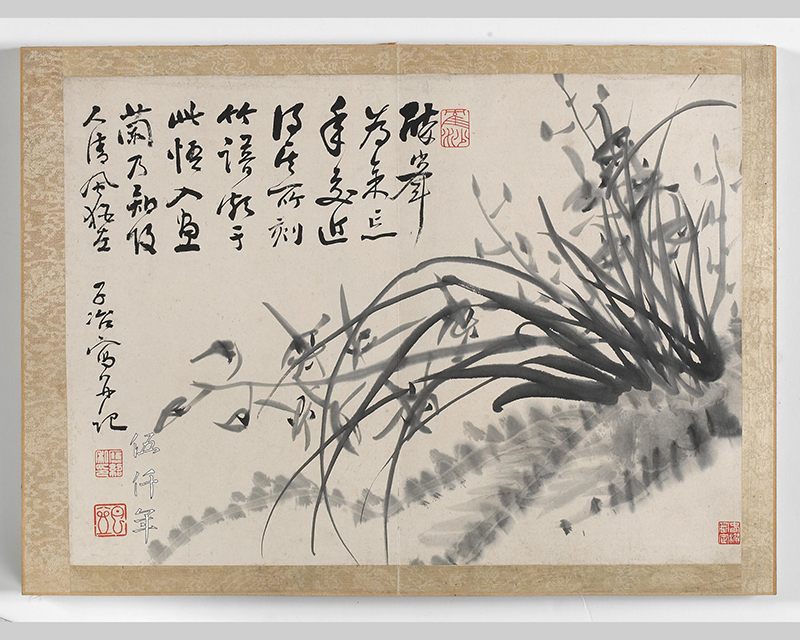

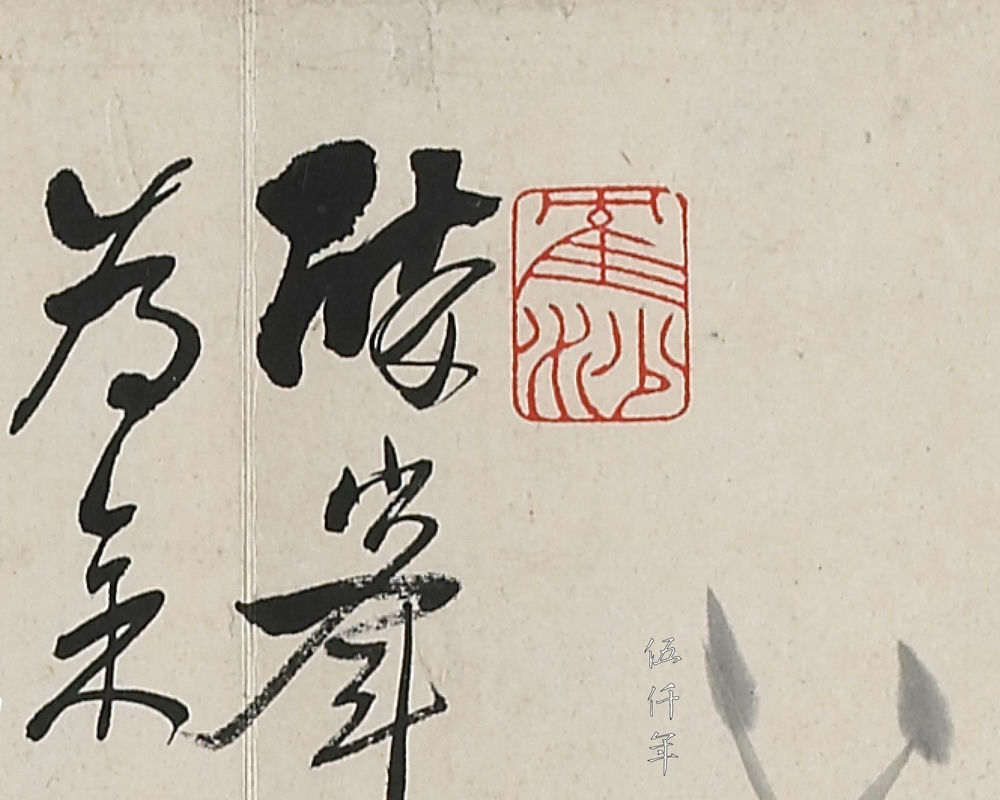

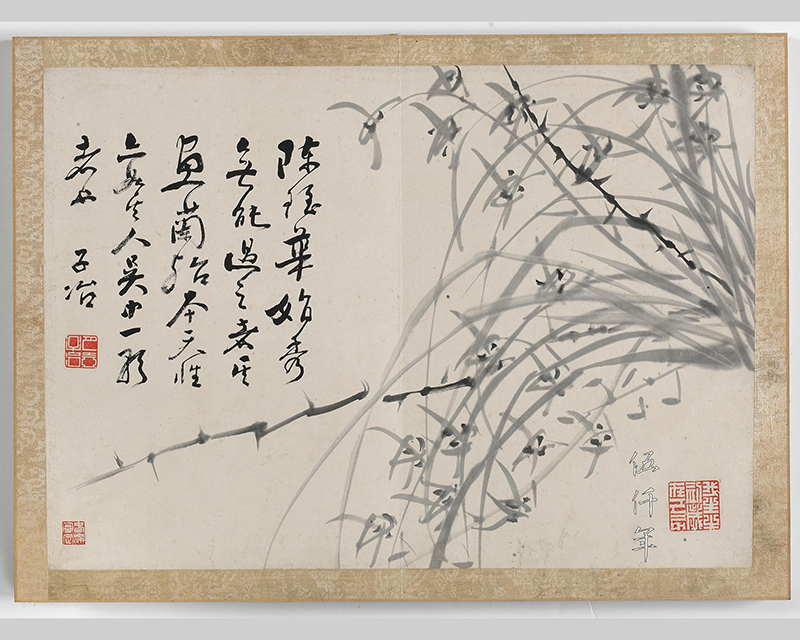

The seal “Ho-sha” (鶴沙) was impressed on the third page of Orchid and Bamboo Painting Album by Ch’ü Ying-shao

The seal “Ho-sha” (鶴沙)

For generations, the ancestors of Ch’ü Ying-shao were distinguished officials. The halls, rooms and furnishings of his house were of utmost refinement. Residences owned by other literati fell short in comparison. In Mo-lin chin-hua (墨林今話 Contemporary Conversations on the World of Ink), the author Chiang Pao-ling (蔣寶齡 1779-1840) recalled the scenes in his house, equating them to that of the fabled Ch’ing-pi Ko (清閟閣), residence of Ni Tsan (倪瓚 1301-1374), painter and art connoisseur of the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368). Reading the description by Chiang, the mind wanders adrift inside the house:

“The sub-prefect Ch’ü Ying-shao, who used the hao Yüeh-hu (月壺) earlier on, now calls himself Ch’ü -fu (瞿甫), or Lao-yeh (老冶). He is a native of Shanghai. He excels in poetry, tz’u lyrics and letter writing. Even in his youth, he has already befriended the virtuous scholars of the prefecture, and his name is celebrated in Wu-sung. His calligraphy and paintings are in the style of Yün Shou-p’ing (惲壽平 1633-1690). He is particularly fond of seal engraving, his style is precise and orderly, entering the realm of the ancients.

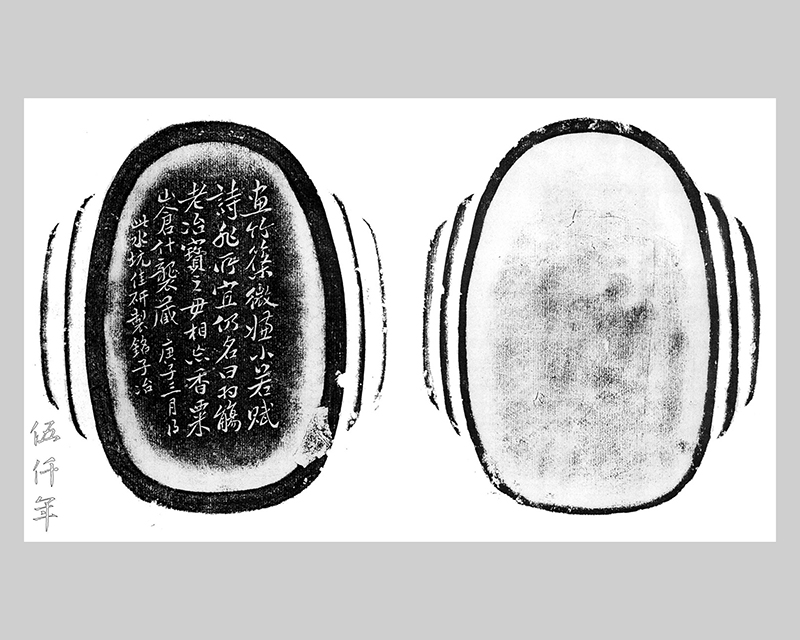

Where he lives, there are halls and rooms with such names: Hsiang-hsüeh Shan-ts’ang (香雪山倉 Mountain Barn of Fragrant Snow. According to the inkstone inscription illustrated here, the name should be Hsiang-su Shan-ts’ang, 香粟山倉 Mountain Barn of Fragrant Corn), Erh-shih-liu Hua-p’in Lu (二十六花品廬 Cottage of Twenty Six Flower Species), Yü-lu-san-chien-hsüeh-tz’u Kuan (玉鑪三澗雪詞館 Hall of Jade Burner, Three Snow Streams and Tz’u Lyrics. According to the seal impressions on his calligraphy and paintings, it should be written as 玉鑪三磵雪詞館). They are all designated to store archaic bronzes, books in general and books on history, fine calligraphy and paintings by contemporary and historic personages. He adores calamus and displays them in vases and bowls. Their placements are meticulous and implacable. Entering his house is no less than visiting Ch’ing-pi Ko, the residence of Ni Tsan.”

Ink rubbing of an inkstone used by Ch’ü Ying-shao. The inscription contained the studio name Hsiang-su Shan-ts’ang (香粟山倉 Mountain Barn of Fragrant Corn).

Part of a painting by Ch’ü Ying-shao impressed with the seal “Yü-lu-san-chien-hsueh-tz’u Kuan (玉鑪三磵雪詞館 Hall of Jade Burner, Three Snow Streams and Tz’u Lyrics)

Ch’ü Ying-shao (1779-1850) used a great number of tzu, hao and studio names. These names were sporadically documented by the inscriptions and seal impressions on his extant calligraphy and paintings. Some of his studio names are now gathered here, to rectify the neglected omissions in the past. They are:

Yü-hsiu T’ang (毓秀堂 Drawing Room of Sprouting Talent), Shih-ou-ch’in Kuan (石鷗沁館 Hall of Sentient Stone Seagull), Shih-ssu-chu Chai (石似竹齋 Studio of Stone Akin to Bamboo), Ch’ing-lien Yüeh An (青蓮月庵 Hermitage of Cyan Lotus under the Moon), Pai-shih Hsüeh-lo Fang (白石薜蘿房 Chamber of White Stone, Climbing Fig and Beard Moss), Ch’ing-lien An (青蓮盦Hermitage of Cyan Lotus), Wan-chu An (萬竹盦 Hermitage of Unending Bamboo), Ku-t’ieh An (古鐵盦 Hermitage of Ancient Iron), Shih-erh Hung-ssu-yen Shih (十二紅絲研室 Chamber of Twelve Red-Grained Inkstones), Yüeh-hu (月壺 Moon Teapot. This studio name was also used by Ch’u as a hao).

It is no longer possible to ascertain whether these names were specially created for the halls, drawing rooms and chambers inside his house, or merely prompted by the refined indulgence of seal engraving, to build imagined architectural spaces through calligraphic engravings on seal stones for personal amusements. After the many momentous turmoils in the last two hundred years, the house of Ch’ü Ying-shao had long turned to ashes. Yet if we savour with delicacy the literary vistas of these seals, it is possible to understand his consciousness, so faraway from the dusty world.

From the extant calligraphy and paintings by Ch’ü Ying-shao, many tzu and hao names are also identified. They are:

Tzu-yeh (子冶 Metalsmith), Yüeh-hu (月壺 Moon Teapot), Pi-ch’un (陛春 Spring Rises), Ch’ü -fu (瞿甫 Mister Ch’u), Lao-yeh (老冶 Old Metalsmith), Yeh-fu (冶父 Mister Metalsmith), Hu-kung (壺公 Man of Teapot), Hu-chung Tzu (壺中子 Man Inside Teapot), Tzu-yeh Fu (子冶父 Mister Metalsmith), T’ieh-yeh (鐵冶 Metalsmith of Iron), Chu-ch’i (竹契 Bamboo Friendship), Ch’ü -an (瞿盦 Hermitage of Ch’u), Chung-wu Hua-shih (中吳畫史 Painter of Chung-wu District), Chu-Ch’ü (竹瞿 Bamboo Ch’u), T’ao-weng (陶翁 Old Ceramic Potter), Yüeh-wu Shan-jen (月壺山人 Hermit of Moon Teapot), Shih-Ch’ü (石瞿 Stone Ch’u), Yün An (雲 盦 Hermitage of the Clouds) and Hu-shih (壺史 Teapot Artisan).

The meanings and connotations of these names reveal his all consuming artistic aspirations, especially his passion for making teapots.

The seal “Wo sheng chih ch’u sui tsai chi-hai” (我生之初歲在己亥 I was born in the year chi-hai) was impressed on the eleventh page of Orchid and Bamboo Painting Album by Ch’ü Ying-shao

The seal “Wo sheng chih ch’u sui tsai chi-hai” (我生之初歲在己亥 I was born in the year chi-hai)

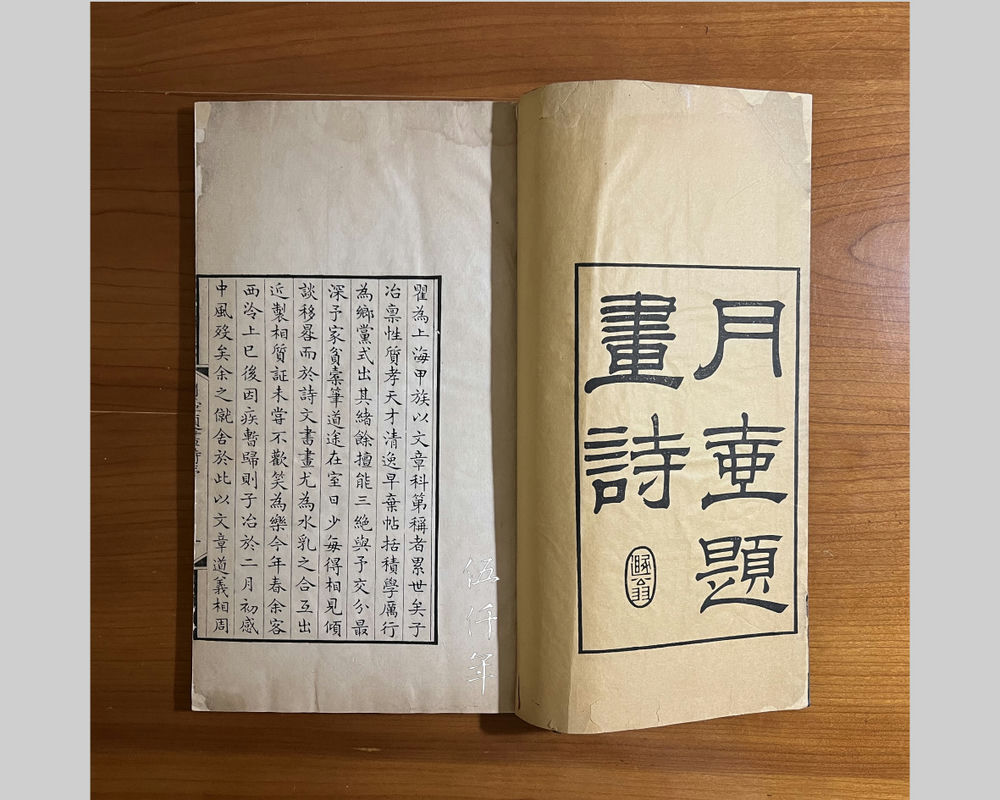

After the death of Ch’ü Ying-shao, his son Hsiao-ch’un (小春) compiled Yüeh-hu t’i-hua shih (月壺題畫詩 A Collection of Poems Inscribed on Paintings by Yüeh-wu). He asked three intimate friends of his father, Chang Tan (張澹), Liu Shu (劉樞) and Hsü Wei-jen (徐渭仁), to write the introductions. In the introduction by Chang Tan, he wrote that Ch’ü Ying-shao passed away in February the 30th year of the Tao-kuang reign (1850), keng-hsü (庚戌) year. This is the most conclusive information about the year of his death.

In Ch’ing-tai hua-shih tseng-pien (清代畫史增編 Supplement to the History of Painting in the Ch’ing dynasty), it is alleged that Ch’ü passed away at the age of seventy. In Shanghai hsien-chih (上海縣志 County Annals of Shanghai), it claims that Ch’ü passed away at the age of seventy two. On a number of his calligraphy and paintings, Ch’ü impressed the seal “Wo sheng chih ch’u sui tsai chi-hai” (我生之初歲在己亥 I was first born in the year chi-hai). The birth year of Ch’ü is thus revealed. Chi-hai (己亥) year is the 44th year of the Chien-lung reign (1779). Hence Ch’ü Ying-shao passed away at the age of seventy two, according to traditional Chinese custom of counting the year of birth as one year old.

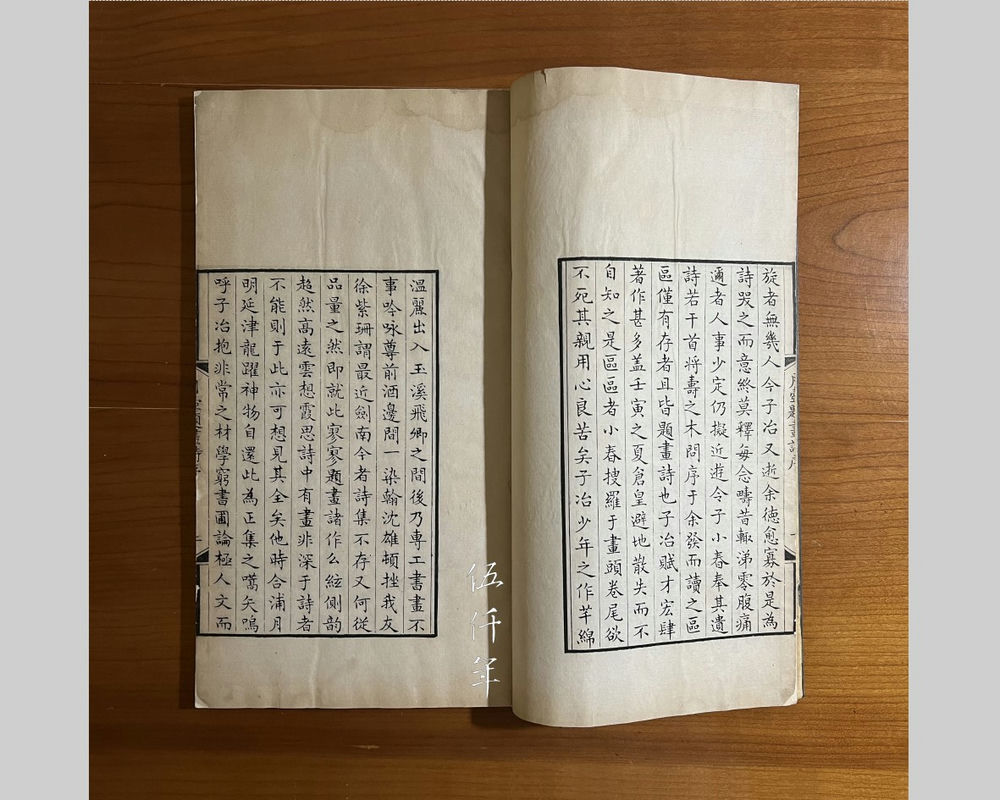

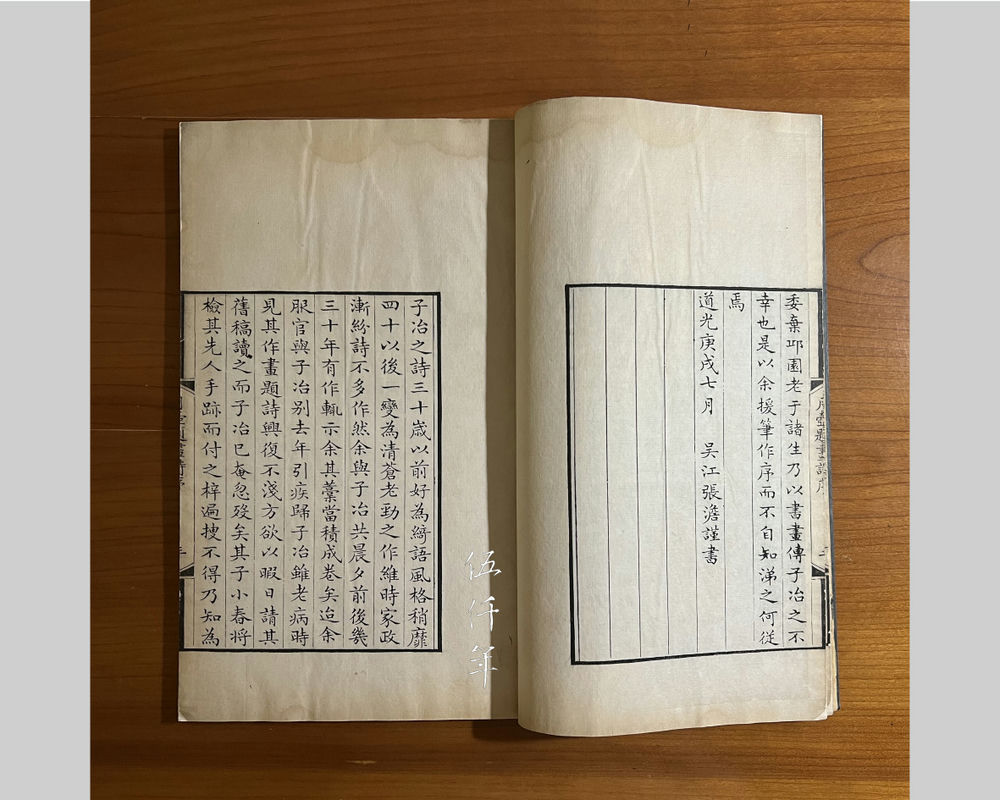

Title page of Yüeh-hu t’i-hua shih (月壺題畫詩 A Collection of Poems Inscribed on Paintings by Yüeh-hu)

Inside page of Yüeh-hu t’i-hua shih (月壺題畫詩 A Collection of Poems Inscribed on Paintings by Yüeh-hu) with introduction by Chang Tai

Inside page of Yüeh-hu t’i-hua shih (月壺題畫詩 A Collection of Poems Inscribed on Paintings by Yüeh-hu) with introduction by Chang Tai

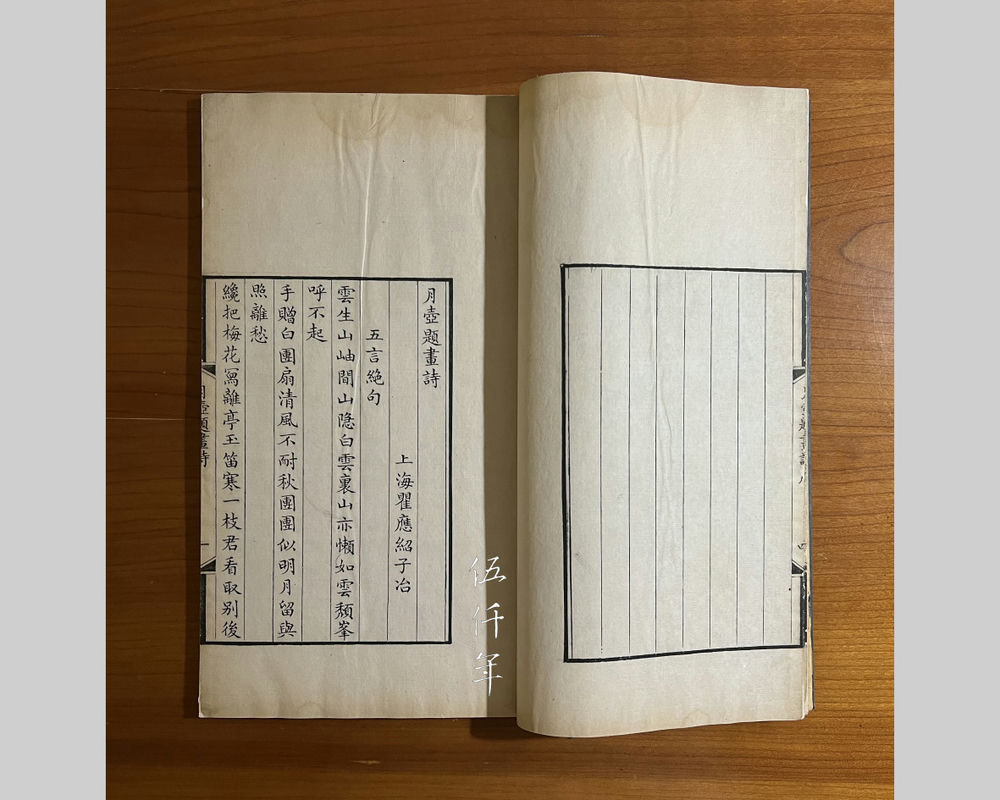

Inside page of Yüeh -hu t’i-hua shih (月壺題畫詩 A Collection of Poems Inscribed on Paintings by Yüeh-hu)

Regrettably, the poetry and writings by Ch’ü Ying-shao were lost in the 22nd year of the Tao-kuang reign (1842), jen-yin (壬寅) year, when he was sixty four. In the introduction by Chang Tai:

“He wrote many works. However in the summer of jen-yin year, he had to flee in haste. The writings were lost without him knowing.”

In the introduction by Liu Shu:

“His son Hsiao-ch’un was going to compile and publish his father’s writings. He searched for them and found nothing. He realized that they were lost during the flight from the upheaval of jen-yin year.”

In the introduction by Hsü Wei-jen:

“The poetry manuscripts were lost during the battle of jen-yin year. It is truly lamentable!”

At one time, Ch’ü Ying-shao was appointed sub-prefect (同知) of Yü-huan County in the south-eastern coast of Chekiang Province. It is now a county in Tai-chou City. His job was to assist the prefect of Yü-huan, the year of his assignment could no longer be verified. Even though Yü-huan was not a military stronghold, for the Opium War that broke out in the 20th year of the Tao-kuang reign (1840), it was still the front line of war. If the poetry and writings by Ch’ü Ying-shao had not been lost, it would be conceivable to find vehement, indignant and politically oriented writings.

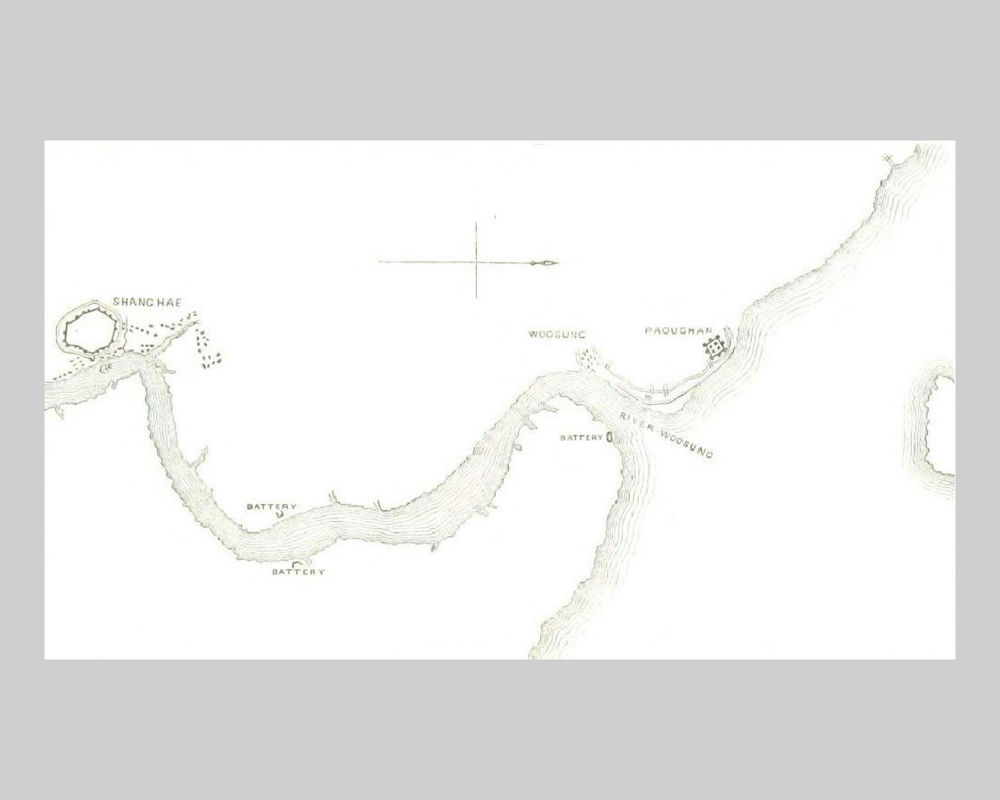

In the 21st year of the Tao-kuang reign (1841), a British fleet of twenty five warships, fourteen steamships and ten thousand soldiers gathered on the Yantze River. On 8th May (Chinese Agricultural Calender) in the following year, the British fleet invaded Wu-sung (Woosung), and on 11th May, Shanghai was captured, followed by a few days of plundering. It was likely that Ch’ü Ying-shao fled with his manuscripts of poetry and writings, some of his personal seals, a small quantity of calligraphy, paintings, books and antiques. As for his exquisite house and his whole art collection, it could only be left to the mercy of divine will. In the chaos of war, even those treasured items he kept by his side, could not avoid damage nor loss.

The Battle of Woosung on 8th May in the 21st year of the Tao-kuang reign (1841)

Map showing Woosung River linking Woosung and Shanghai published in the 2nd year of the Hsien-feng reign (1852)

Ch’ü Ying-shao commanded exalted reputation in teaware. His teapots have been prized and collected for generations, and this ardour is undiminished to this day. When Ch’ien-ch’en meng-ying lu (前塵夢影錄 A Record of Memories and Dreams) by Hsü Tz’u-chin (徐子晉) was first published in the Kuang-hsü reign, the author already referred to the teapots by Ch’ü in this manner:

“There are not many in existence. The antique trade flaunts them as rarities.”

However reading the introductions by his three friends Chang Tan, Liu Shu and Hsü Wei-jen in A Collection of Poems Inscribed on Paintings by Yüeh-hu, there are extensive discussions on the deeds, virtuosities and artistic pursuits of Ch’ü Ying-shao. They dwelled on his poetry, writings, calligraphy and paintings. As for the making of teapots, not a single word is mentioned. But why? At that time, even like-minded friends still regarded the making of teapots a minor skill of little importance, unworthy of serious conversations. It was belittled to such extent! Who could have foretold in two hundred years time, it was conversely the teapots left behind by Ch’ü that immortalized him in the world of art, whilst his poetry, writings, calligraphy and paintings subsided into the background.

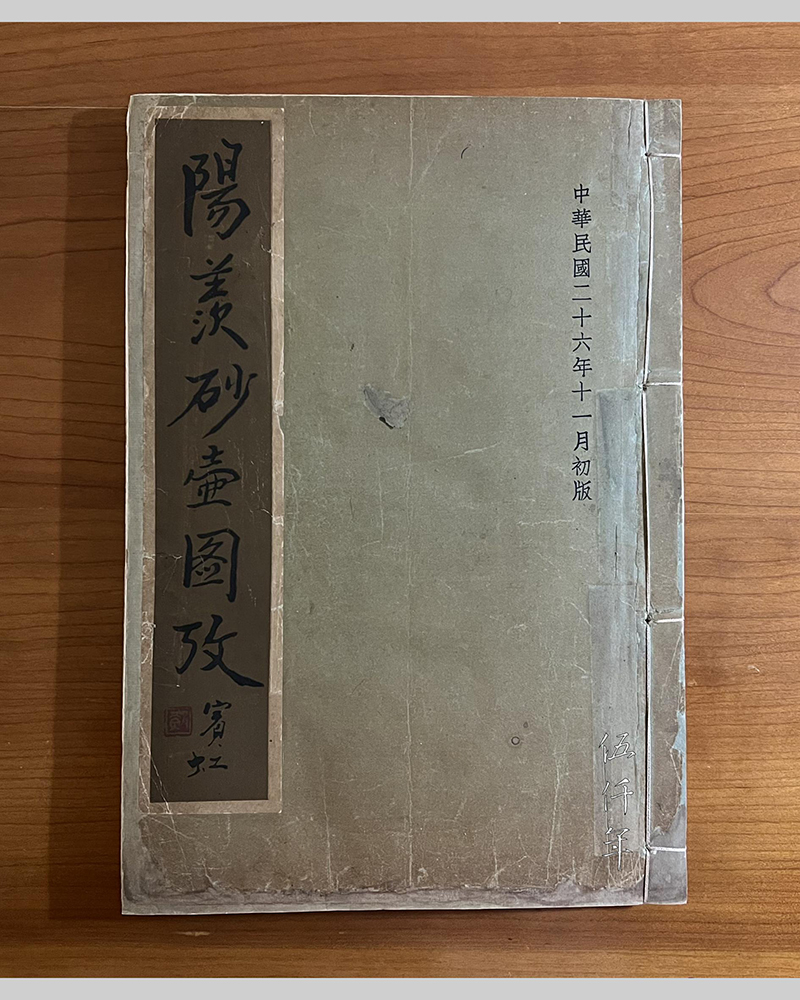

Front cover of Yang-hsien sha-hu t’u-k’ao (陽羡砂壺圖考 The Pictorial Studies of Clay Teapots from Yang-hsien)

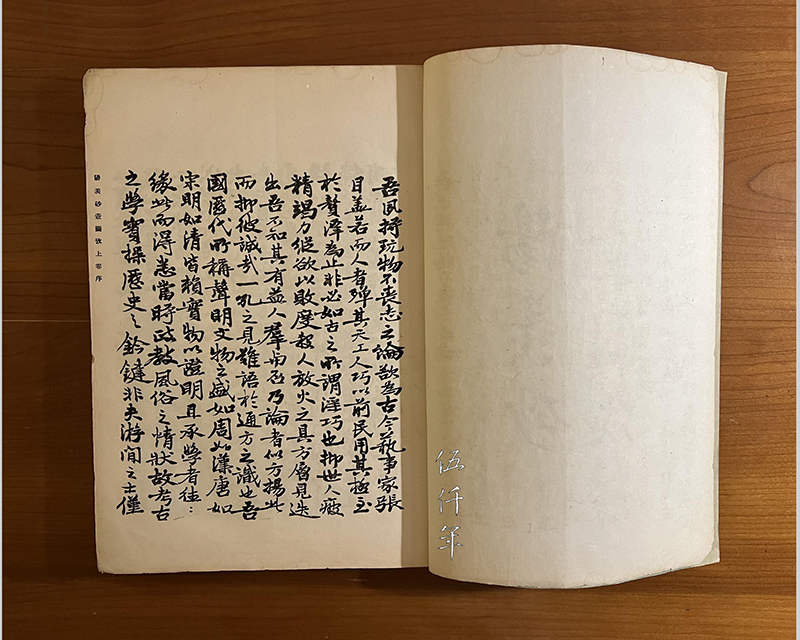

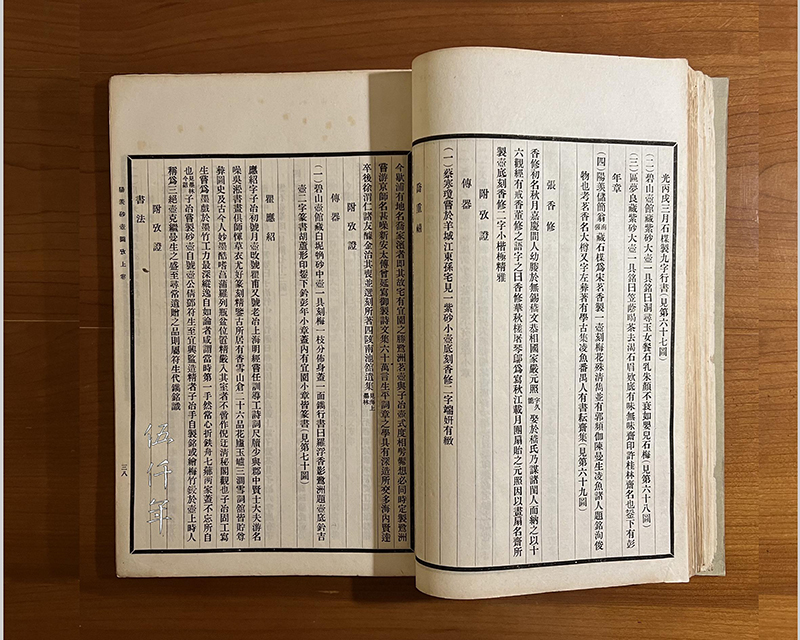

Inside page of Yang-hsien sha-hu t’u-k’ao (陽羡砂壺圖考 The Pictorial Studies of Clay Teapots from Yang-hsien) with preface by Yeh Kung-ch’o

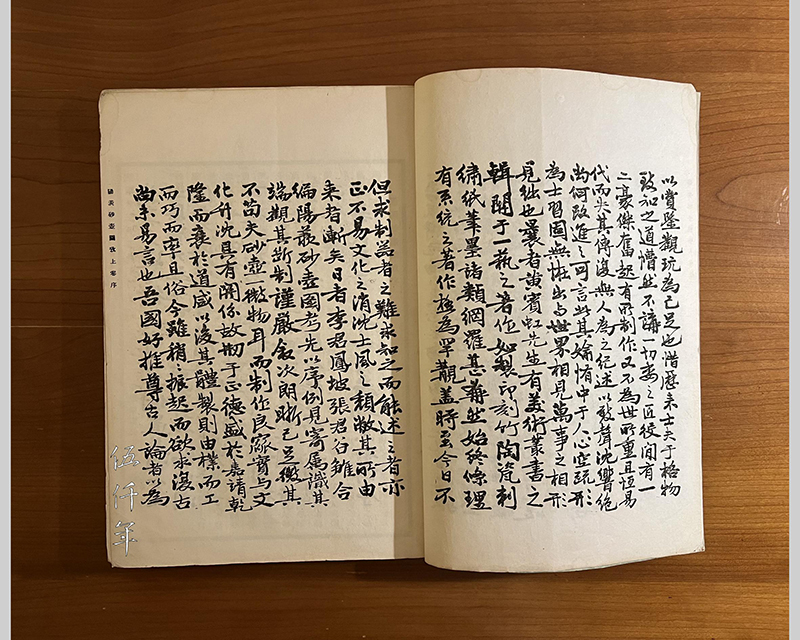

Inside page of Yang-hsien sha-hu t’u-k’ao (陽羡砂壺圖考 The Pictorial Studies of Clay Teapots from Yang-hsien) with preface by Yeh Kung-ch’o

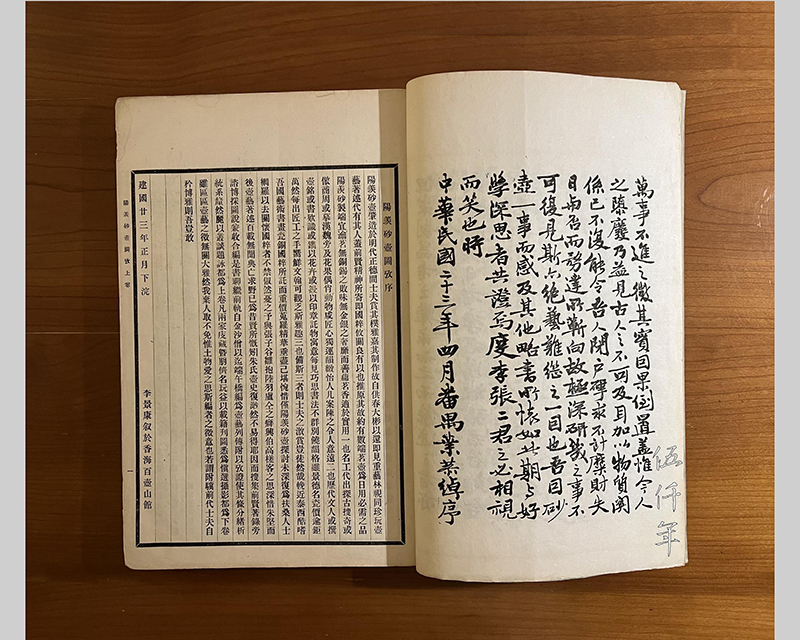

Inside page of Yang-hsien sha-hu t’u-k’ao (陽羡砂壺圖考 The Pictorial Studies of Clay Teapots from Yang-hsien) with preface by Yeh Kung-ch’o

In the 26th year of the Republic (1937), Li Ching-k’ang (李景康) and Chang Hung (張虹) compiled Yang-hsien sha-hu t’u-k’ao (陽羡砂壺圖考 The Pictorial Studies of Clay Teapots from Yang-hsien). Yeh Kung-ch’o (葉恭綽) was asked to write the preface. It says:

“I have always maintained the tenet that one will not forfeit high-minded goals as a hedonist of art objects. I wish to amplify the presence of those artists dedicated to art objects in our time and in the past………….

It is a shame that scholars ever since have been ignorant and silent on the acquisitions of knowledge through the investigations of physical phenomena and items. They delegated everything to craftsmen and retainers. Intermittently a few remarkable men rose in vigour to create some objects, yet the world did not pay attention. Furthermore they were always lost with the next generation, nor did anyone document them, until they were heard by none. How can there be talk about improvement?…………….

Our countrymen relish heaping praises on the ancients, critics believe this is an indicator that stalls everything. In reality the cause-and-effect is reversed, it is because of our decadence that the ancients are perceived more than ever to be incomparable.”

These words resonate well. More so when the intellectual and artistic desk accoutrements of traditional Chinese scholars are still languishing in gradual obsolescence in our time.

Inside page of Yang-hsien sha-hu t’u-k’ao (陽羡砂壺圖考 The Pictorial Studies of Clay Teapots from Yang-hsien) with biography of Ch’ü Ying-shao

Ch’ü Ying-shao was accomplished in engraving teapots. He invited Teng K’uei (鄧奎), hao Fu-sheng (符生) to be the supervisor, Yang P’eng-nien (楊彭年) and sometimes Shen Hsi (申錫) as the potter. Yang-hsien sha-hu t’u-k’ao (陽羨砂壺圖考 The Pictorial Studies of Clay Teapots from Yang-hsien) explains:

“At one time, Tzu-yeh (子冶 Ch’u Ying-shao) made teapots and called himself Hu-kung (壺公 Mister Teapot). He asked Teng K’uei to go to I-hsing to supervise production. Tzu-yeh hand carved poetic inscriptions on the finest teapots, or incised prunus and bamboo on them. They were called San-chüen hu (三絕壺 The Three Absolutes Teapot) by his contemporaries. Triumphantly they carried on the splendour of the teapots by Chen Man-sheng (陳曼生 1768-1822). For his ordinary teapots used as presents, he asked Teng K’uei to carve the inscriptions.”

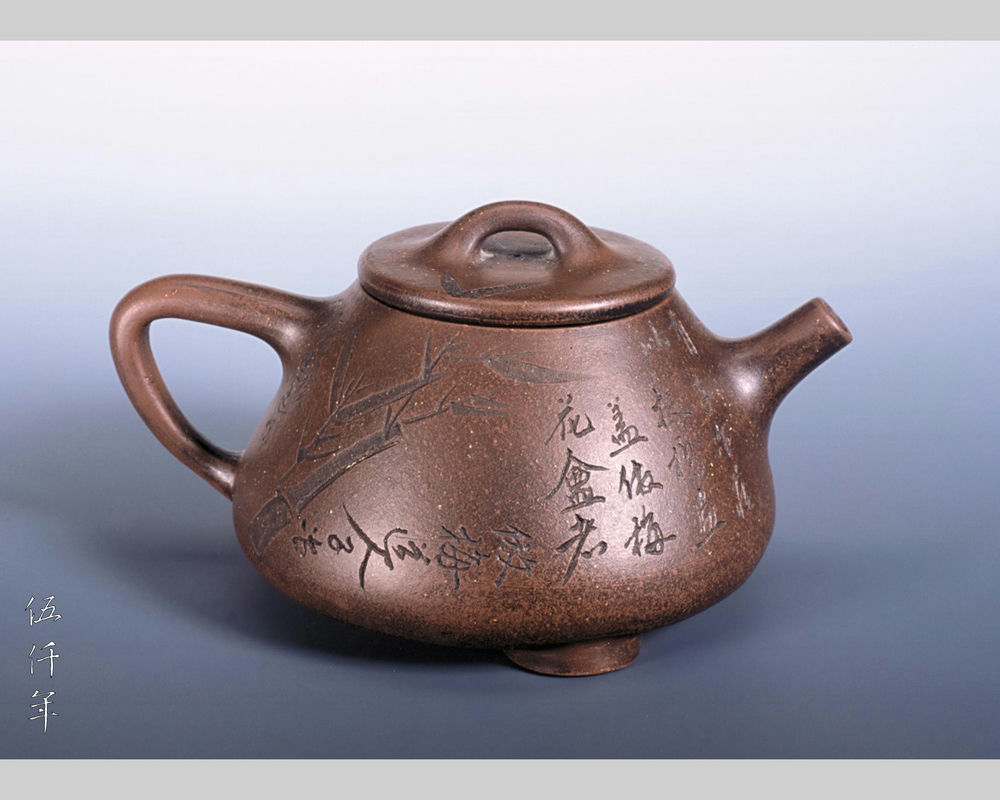

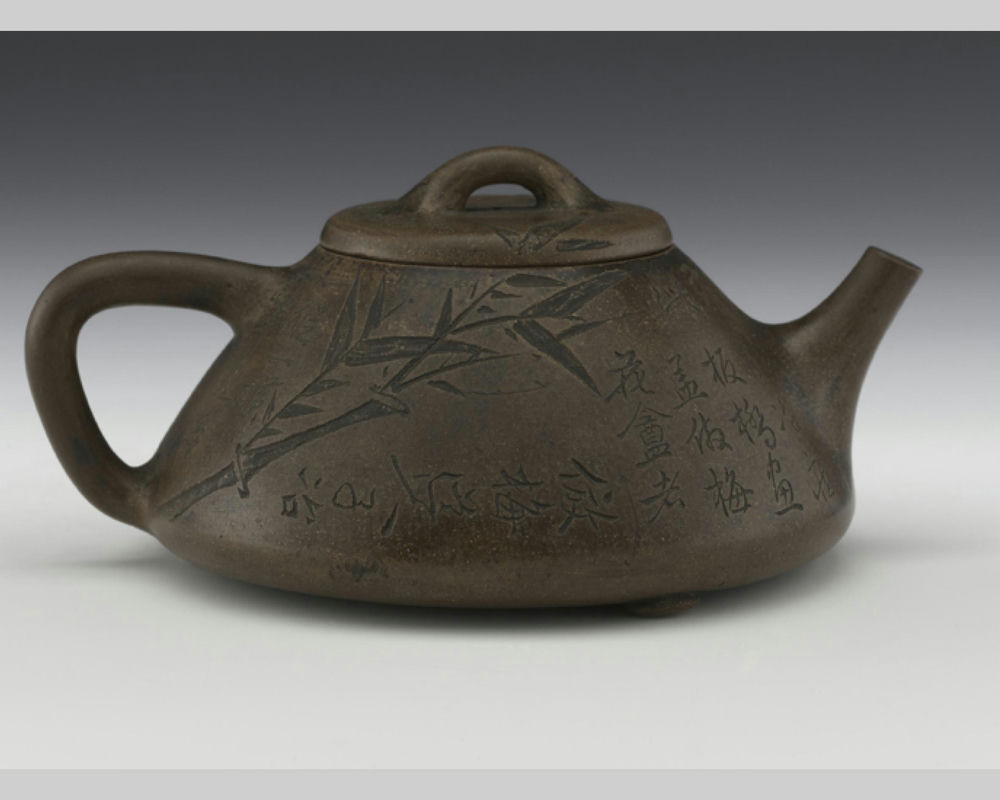

One side of the incised bamboo clay teapot by Ch’ü Ying-shao in the Studio of Prunus Ode

Ink rubbing of one side of the incised bamboo clay teapot by Ch’ü Ying-shao in the Studio of Prunus Ode

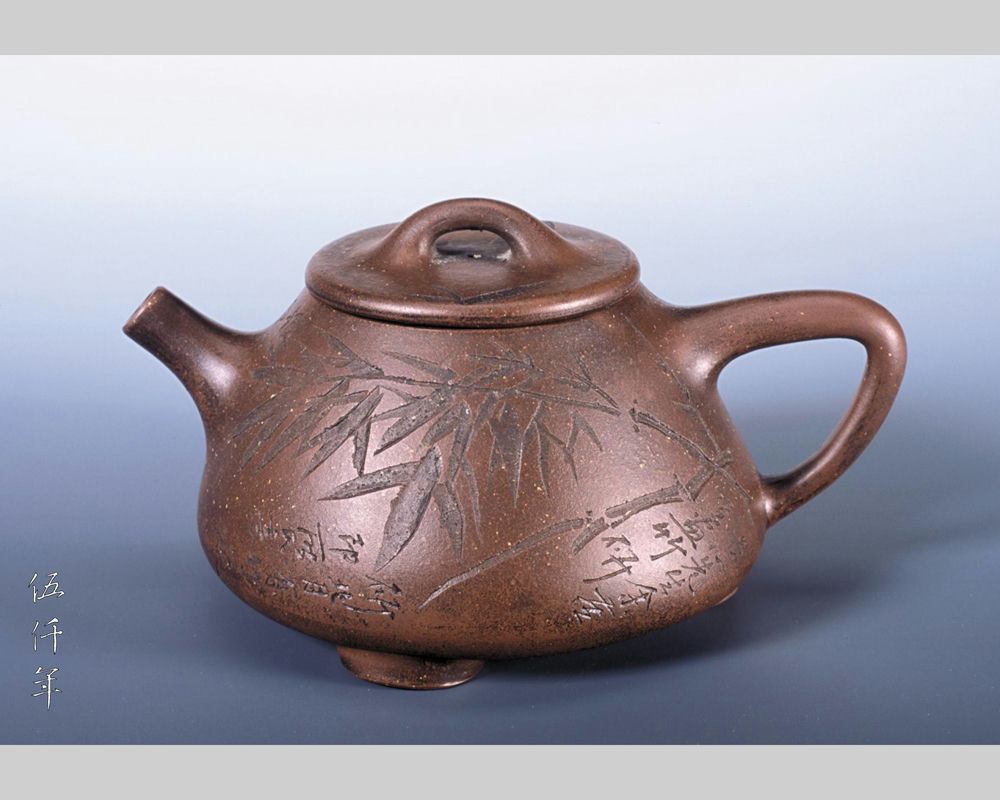

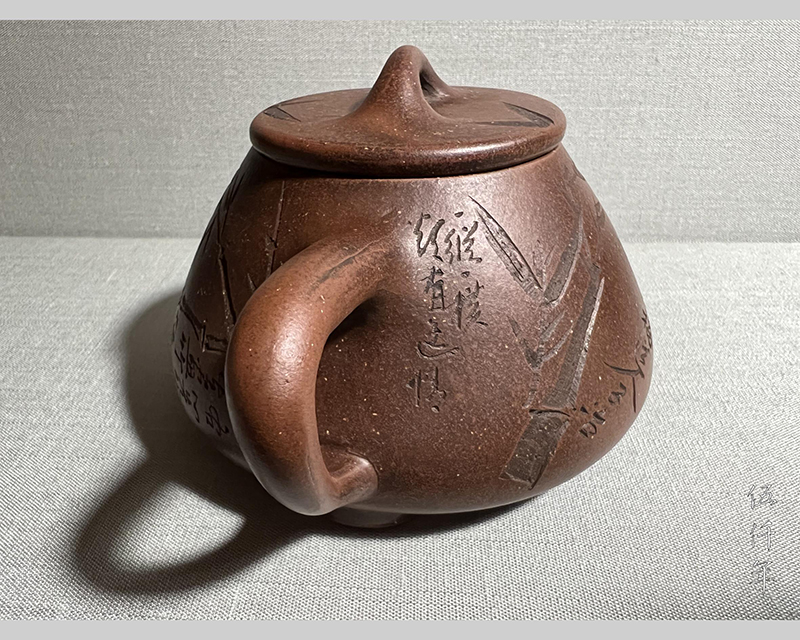

Second side of the incised bamboo clay teapot by Ch’ü Ying-shao in the Studio of Prunus Ode

Ink rubbing of second side of the incised bamboo clay teapot by Ch’ü Ying-shao in the Studio of Prunus Ode

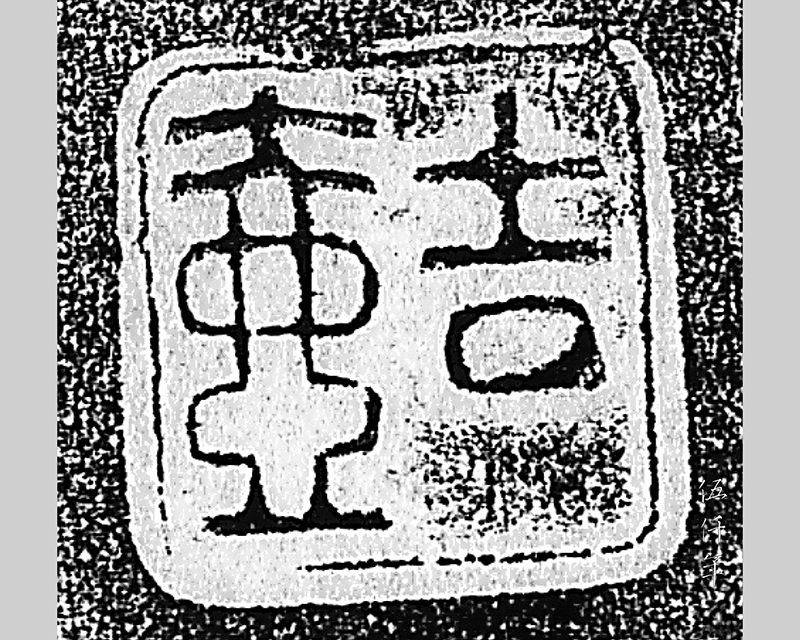

“P’eng-nien” seal legend under the handle of the teapot

Ink rubbing of the “P’eng-nien” seal legend under the handle of the teapot

The base of the incised bamboo clay teapot with the characters “Chi-hu”

“Chi-hu” seal legend at the base of the teapot

Ink rubbing of the “Chi-hu” seal legend at the base of the teapot

In the Studio of Prunus Ode, there is a shih-tiao (石銚) shaped clay teapot engraved with bamboo by Ch’ü Ying-shao. It was potted by Yang P’eng-nien. There is a seal legend of “P’eng-nien” (彭年) at the underside of the handle. In the collection of the Shanghai Museum, there is also a shih-tiao shaped clay teapot engraved with bamboo by Ch’ü Ying-shao. The form and engravings are the similar, there is likewise a seal legend of “P’eng-nien” at the underside of the handle. For the teapot in the Studio of Prunus Ode, there is a square seal legend with the characters “Chi-hu” (吉壺 Auspicious Teapot) at the base. For the teapot in the Shanghai Museum, the “Chi-hu” seal legend at the base differs in the shape of a gourd.

Different seal legends are seen at the bases of Chü’s extant teapots. There are seal legends with the characters: Yüeh-hu (月壺 Moon Teapot), Hu-fu Yeh-fu (壺父冶父 Mister Teapot Mister Metalsmith), Tz’u-yeh Chi-hu (子冶吉壺 Auspicious Teapot of Metalsmith), I-yüan (宜園 A Befitting Garden), Le-t’ao-t’ao Shih (樂陶陶室 Chamber of Happiness).

One side of the incised bamboo clay teapot by Ch’ü Ying-shao in the Shanghai Museum

Second side of the incised bamboo clay teapot by Ch’ü Ying-shao in the Shanghai Museum

Base of the incised bamboo clay teapot by Ch’ü Ying-shao in the Shanghai Museum

Ch’ü Ying-shao always employed cursive script to engrave calligraphic inscriptions on the body of the teapot. He did not appear to use regular script, clerical script nor seal script. He liked to carve the inscriptions in a horizontal manner, attaining a naturalistic, intricate and free flowing aesthetics. He created a unique style among the teapot masters of the Ming and Ch’ing Dynasties.

Moreover, Ch’ü Ying-shao pioneered the fashion of applying engraved paintings on teapots. This alone ensures that his name is enshrined in the history of teaware. Another teaware master Chen Man-sheng (1768-1822) was older than Ch’ü by thirteen years. He too excelled in painting, but did not engrave any pictorial image on teapot. The teaware master Chu Chien (朱堅 born in 1790) was also enthusiastic with engraving paintings on teapots. He was the junior of Ch’ü by eleven years, and belonged to a younger generation.

Ch’ü Ying-shao was fond of painting bamboo. There are quite a number of his extant paintings. Most of his teapots were engraved with bamboo, occasionally there were engravings of orchid, prunus and willow. An unusual custom Ch’ü practiced was to extend the engravings of calligraphy and paintings on the body of the teapot to the surface of the lid. The energy of the incisions and the spirit of the calligraphy and paintings appear to pervade the whole teapot.

Engravings of bamboo extend to the lid of the incised bamboo clay teapot

For the teapot in the Studio of Prunus Ode, a few stalks of bamboo were engraved on the two sides as well as the lid. There are five inscriptions:

1) “There is a painting by Pan-ch’iao (板橋) in Tze-yeh’s collection. It was painted in the style of Mei-hua An (梅花庵).”

2) “Imitating Mei Tao-jen (梅道人), Tze-yeh.”(This line of calligraphy was inscribed in the horizontal manner).

3) “Pan-ch’iao (板橋) painted this before.”

4) “One is vertical, one is horizontal. They somehow emanate idle pleasure.”

5) “There is an instone used by Mister Tung-hsin (冬心先生) to paint bamboo in my collection. At the back of the inkstone there is a stalk of bamboo. I emulated its spirit.”(This line of calligraphy was inscribed in the horizontal manner).

A teapot could be modest, a few strokes of bamboo could be simple, but Ch’ü Ying-shao strenuously pursued the inner resonance and spirit of bamboo, conveyed in paintings by great artists in history. The bamboo he thus accomplished, he exerted on the two sides of the teapot. He was himself delighted and gratified, inscribing: “One is vertical, one is horizontal. They somehow emanate idle pleasure.” On one side of the teapot, he engraved a stalk of vertical bamboo, on another side, he engraved a stalk of horizontal bamboo.

“One is vertical, one is horizontal. They somehow emanate idle pleasure”

The name Mei-hua An (梅花庵) mentioned in the first inscription and the name Mei Tao-jen (梅道人) mentioned in the second inscription, were the hao and studio name of Wu Chen (吳鎮 1280-1354) of the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368). His tzu was Chung-kuei (仲圭), hao Mei-hua Tao-jen (梅花道人), Mei Tao-jen (梅道人). He lived at Mei-hua An (梅花庵), a native of Chia-hsing, Chekiang Province. With Huang Kung-wang (黃公望), Wang Meng (王蒙) and Ni Tsan (倪瓚), they are known as the Four Masters of the Yuan dynasty. In his Manual for Painting Ink Bamboo (墨竹譜), Wu Chen wrote:

“To paint bamboo, one must first prepare the bamboo in the heart. Hold the brush and visualize the bamboo. The moment one sees what one wishes to paint, dash forward to follow it, motion the brush to pursue it, chase what one sees, like a rabbit leaping up, like a falcon swooping down. A moment of loosening up and it will be gone.”

He also wrote:

“As for the method of painting bamboo, one must first study its essence, then seek the essence with brushworks.”

“There is a painting by Pan-ch’iao in Tze-Yeh’s collection. It was painted in the style of Mei-hua An”

“Imitating Mei Tao-jen, Tze-yeh”

The name Pan-chiao (板橋) mentioned in the first inscription and the third inscription, was the hao of Cheng Hsieh (鄭燮 1693-1766), native of Yang-chou, Kiangsu Province. He is known as one of the Eight Eccentrics of Yang-chou, renowned for painting bamboo. At one time Cheng Hsieh wrote about the bamboo painting of Wu Chen:

“The method of painting bamboo, is not to be constrained by rules. One should attain inner resonance and spiritual depth. For this reason Mei Tao-jen could reach the highest level of excellence.”

The painting by Cheng Hsieh in the collection of Ch’ü Ying-shao was a creative imitation of the style of Wu Chen.

“Pan-ch’iao painted this before”

The name Mister Tung-hsin (冬心先生) mentioned in the fifth inscription was the hao of Chin Nung (金農 1687-1763), native of Jen-ho, Chekiang Province. He is also known as one of the Eight Eccentrics of Yang-chou. In Tung-hsin mo-chu t’i-chi (冬心墨竹題記 Commentaries on Painting Ink Bamboo by Tung-hsin) :

“I hold the same attitude towards painting bamboo. I do not hasten towards fashion, I do not care for reputation. A stalk of wild bamboo, emerges from my heart.”

“There is an inkstone used by Mister T’ung-Hsin to paint bamboo in my collection”

“At the back of the inkstone there is a stalk of bamboo. I emulated it’s spirit”

Examining the bamboo by Ch’ü Ying-shao, he had encapsulated the artistic essences of the great painters from the past.

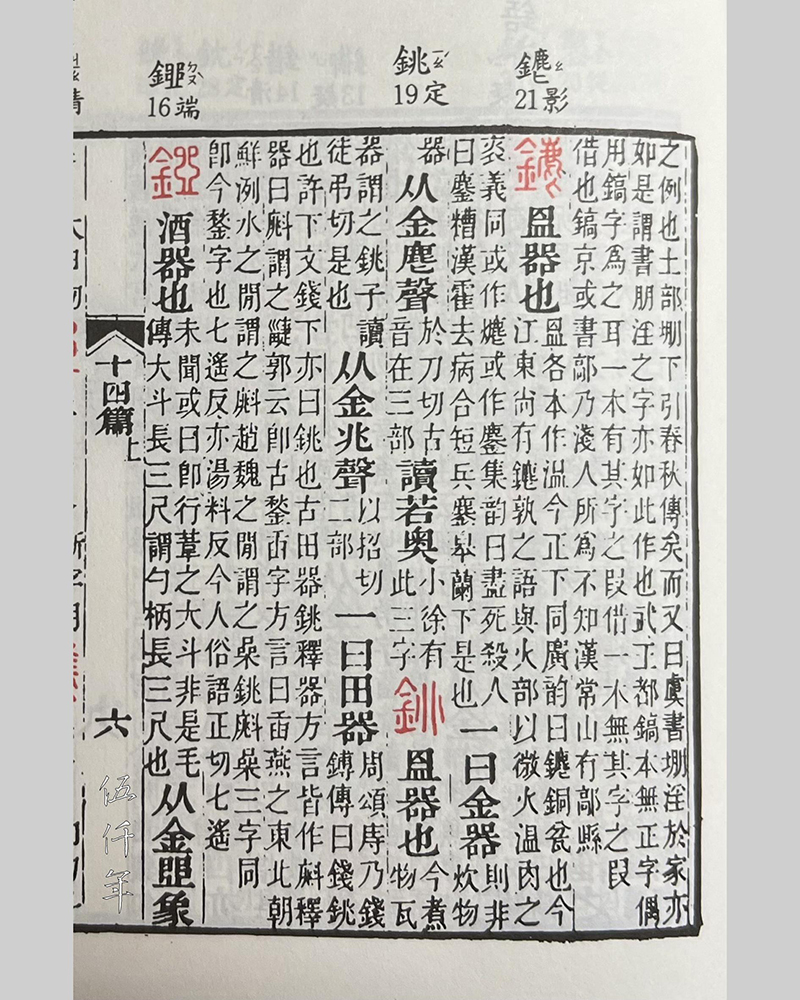

The teapots made by Ch’ü are mostly in the shape of shih-tiao (石銚). It is infrequent to see other shapes. In Cheng-tzu t’ung (正字通 Dictionary of Proper Characters) by Chang Tzu-lieh (張自烈 1597-1673) of the Ming dynasty, the meaning of the character tiao (銚) is given:

“Today a small cooking pot with handle is called tiao.”

Tuan Yü-ts’ai (段玉裁 1735-1815) of the Ch’ing dynasty further explained this character:

“Today a cooking utensil made of clay is called tiao-tzu”.

Explanation of the character tiao (銚) in Shuo-wen chieh-tzu chu (說文解字注) by Hsü-shen (許慎) and annotated by Tuan Yü -ts’ai (段玉裁)

Hence shih-tiao is a clay cooking utensil, alternatively called shih-p’iao (石瓢). Ch’ü Ying-shao did not create many shapes for his teapots, his favorite form was shih-tiao. Perhaps he was especially attracted to a rustic and simple form devoid of elaboration.

Surveying the poetry, calligraphy, paintings and teapots by Ch’ü, their style and artistic vistas are entirely consistent. The works are natural, unostentatious, aloof and unworldly. Indeed they are the quintessential creations from the intellectual and emotional wanderings of a literatus mind. His teapots synthesized the arts of poetry, writings, calligraphy, paintings and seals into one enduring unison. If we consider the personality of Ch’ü on the whole, a combination of purity, eccentricity, cultivation and refinement, no other teaware master of the Ming and Ch’ing Dynasties is similar in character. Some later savant may perhaps approve my words.

Mr. Kuo Jo-yü and Mr. Soong Shu Kong in Taipei

The incised bamboo clay teapot by Ch’ü Ying-shao in my collection, was also deeply appreciated by my late friend Mr. Kuo Jo-yü (郭若愚先生). Twenty something years ago, I saw Mr. Kuo regularly. Occasionally we went to the pre-auction exhibitions in Shanghai to examine antiques, calligraphy and paintings. One day in early June 1999, we came across this teapot in a pre-auction exhibition, and we both regarded it as a fine work by Ch’ü. Mr. Kuo frequently used a playful phrase: “No buying and no selling” to discipline himself, hence I managed to acquire this piece. Now that I respectfully offer this piece to kindred spirits for perusal, I recall the fortuitous encounter in collecting and the friendship of my late friend, so I composed this postscript.

Ink rubbing of detail of the incised bamboo clay teapot by Ch’ü Ying-shao in the Studio of Prunus Ode