Most of those who talked about Ku Hung-ming (辜鴻銘 1857-1928) like to repeat his eccentric conversations and behaviors, rarely on his learnings and convictions. Tales from the grapevine may entertain the public, yet they do not enable us to really know him. Ku Hung-ming was born in a time of traumatic change. He witnessed the invasions of the Imperial Powers, the abandonment and rejection of Classical Chinese Culture by fellow Chinese, and their embracement and advocation of Western Culture. It was not only the loss of national territory, it was also the looming demise of national culture. In opposition, he henceforth published books in Chinese, English and German to expound on Confucianism. Using the resources of a writer, he fought the world across the five continents. These were driven by his anguish and valiance. If Ku Hung-ming were to witness the Cultural Revolution and the Simplified Chinese Characters unleashed by the communists decades later that completely devastated Classical Chinese Culture, how much more would be his rage?

Curatorial and Editorial Department

Amongst the scholars of late Ch’ing, he who could master profound knowledge about the politics and culture of East and West, yet withstood against Westernization; who could publish books to expound Confucianism in Chinese, English and German; who could sway public opinions in numerous Western countries; whose cultural ambition enfolded the four seas and the five continents; was the one and only Ku Hung-ming (辜鴻銘).

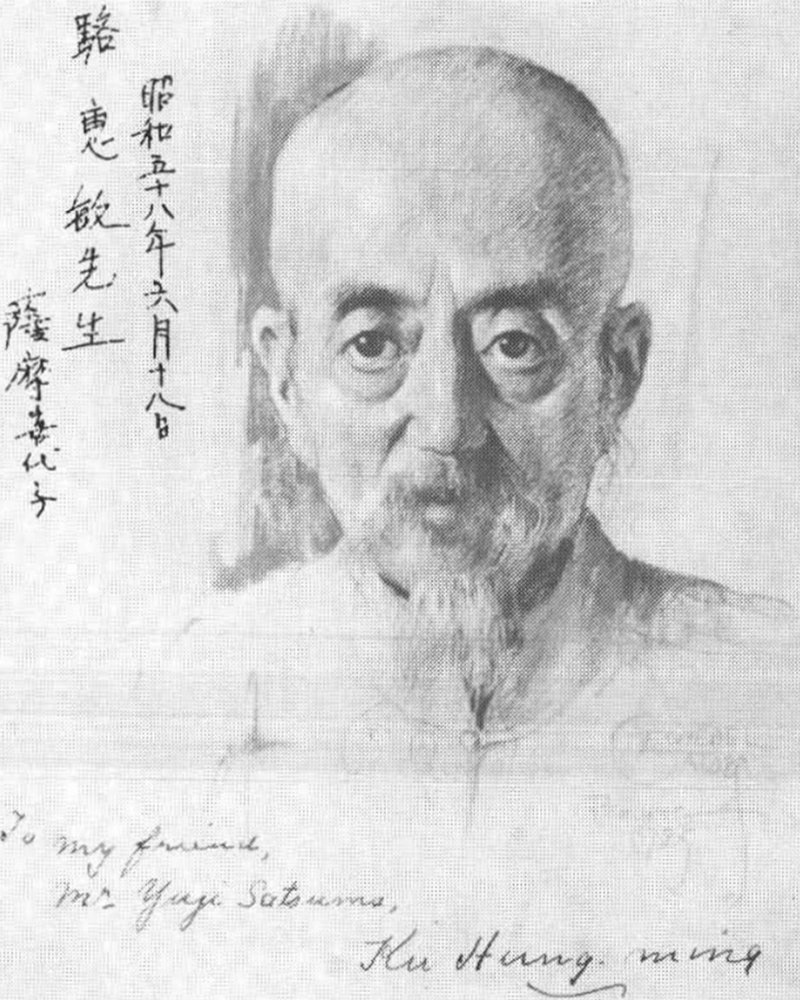

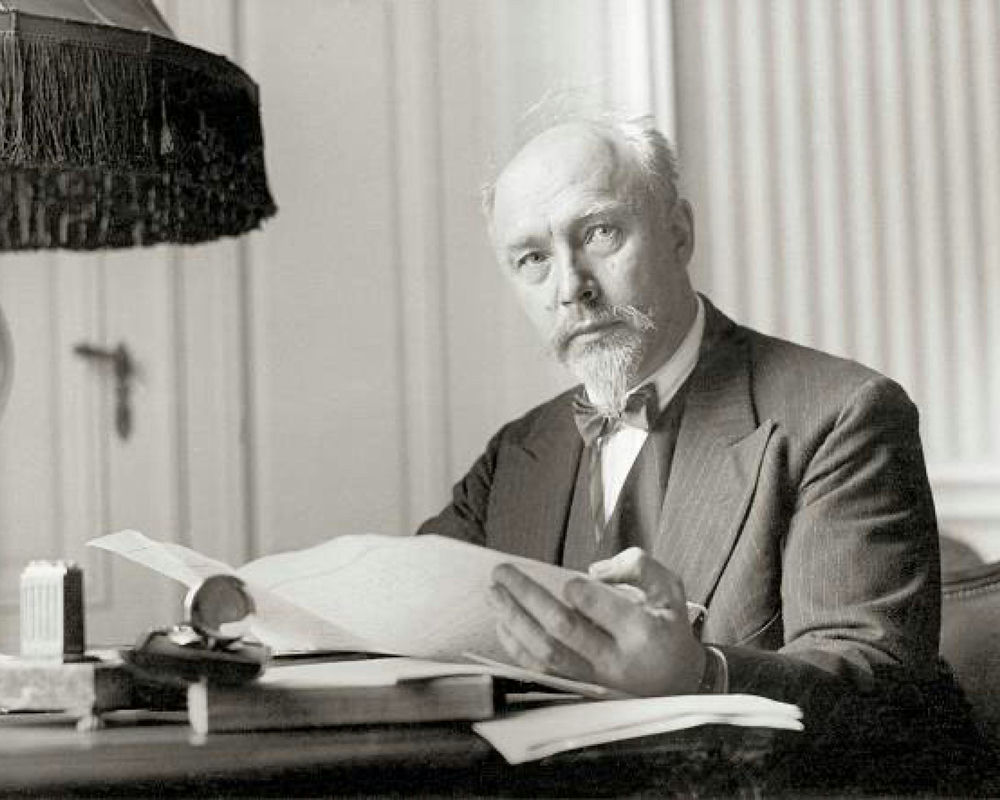

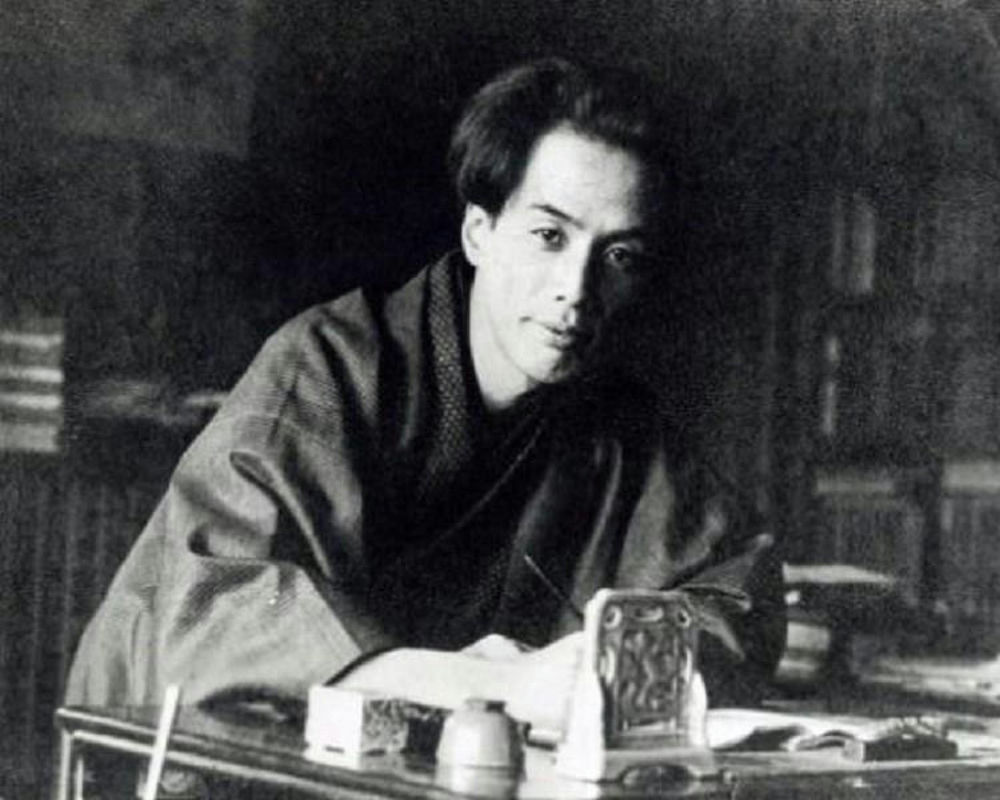

Portrait of Ku Hung-ming

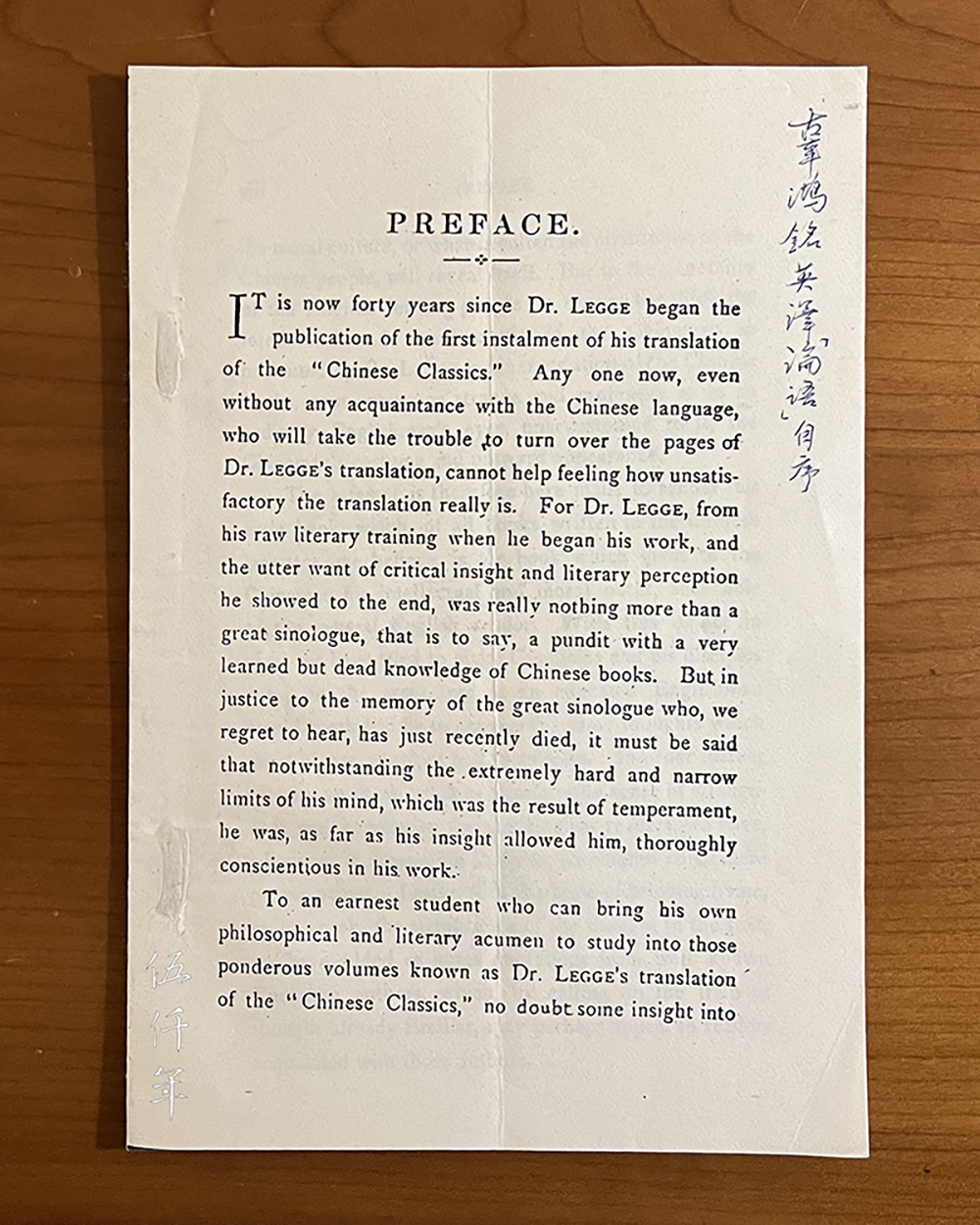

During the junior years of my secondary school education, my father Mr. Soong Hsün-leng (宋訓倫) once gave me a four page copy of the Preface of the Discourses and Sayings of Confucius by Ku Hung-ming, whereupon he inscribed a colophon on the last page. Although it was written with a pen, the Chinese characters appeared full-bodied and were attentively written. It was a piece of his handwriting when he was aged over sixty, inscribed forty and more years ago. It reads:

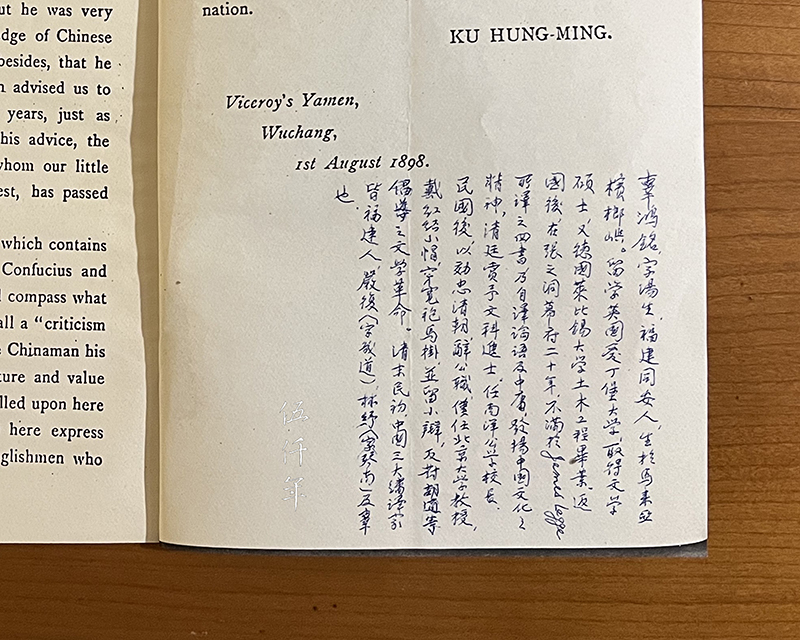

“Ku Hung-ming’s Preface of his English translation of The Analects (論語)

Ku Hung-ming, tzu T’ang-sheng (湯生), native of T’ung-an County, Fukien Province, yet born in Penang, British Malaya. He was educated at the University of Edinburgh, attaining a Master of Arts degree, and then graduated from the civil engineering faculty of the University of Leipzig, Germany. After he returned to China, he worked in the administration office of Chang Chih-tung (張之洞) for twenty years. He was not satisfied with the translations of The Four Books by James Legge, hence he proceeded to translate The Discourses and Sayings of Confucius (論語 also known as The Analects) and The Conduct of Life or the Universal Order of Confucius (中庸 also known as Doctrine of the Mean). For his spirit in expounding Chinese culture, the Ch’ing court granted him the classical liberal arts degree of chin-shih (進士). He was appointed president of Nanyang Mission College.

After the founding of the Republic, he professed his loyalty to the Ch’ing dynasty. He relinquished his position in the civil service, and only secured a professorship at the National Peking University. He wore a small Chinese cap with a red knot, he dressed in a loose Chinese robe with a ma-kua (馬掛) mandarin jacket, and kept his queue. He was against the literary revolution propagated by Hu Shih (胡適) and others. At the end of the Ch’ing dynasty and the early years of the Republic, the three great translators in China were all natives of Fukien Province, Yen Fu (嚴復 tzu Chi-tao 幾道), Lin Shu (林紓 tzu Ch’in-nan 琴南) and Ku.”

First page of Preface of the Discourses and Sayings of Confucius by Ku Hung-Ming, inscribed by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

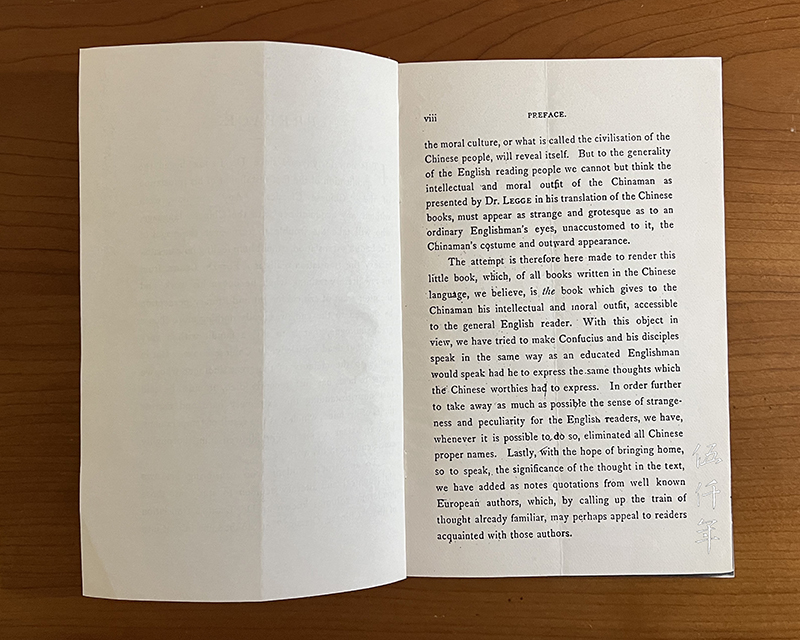

Second page of Preface of the Discourses and Sayings of Confucius by Ku Hung-ming, inscribed by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

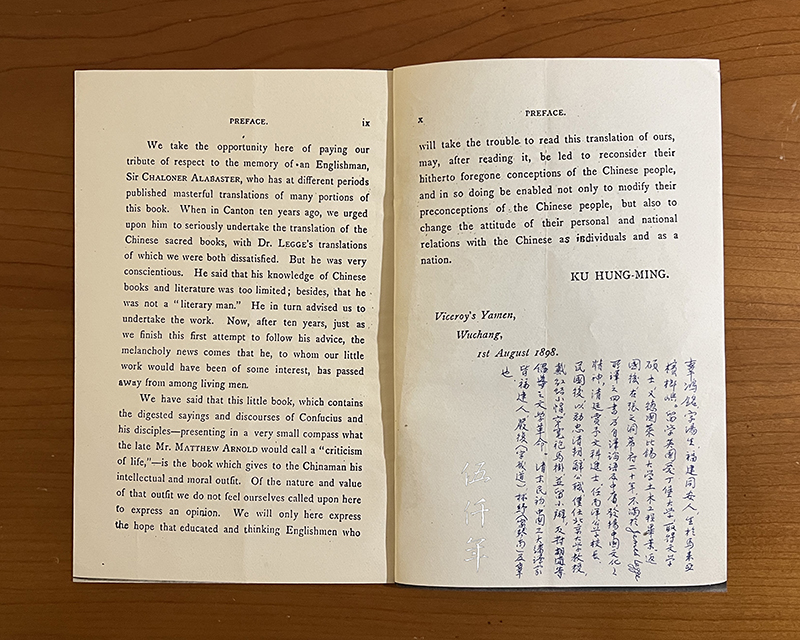

Third and fourth page of Preface of the Discourses and Sayings of Confucius by Ku Hung-ming, inscribed by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

Inscription by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

Ku Hung-ming was born in the 7th year of the Hsien-feng reign (1857), and passed away in the 17th year of the Republic (1928). His hao included Li-Ch’eng (立誠), Yung-jen (慵人), Tung-hsi Nan-pei Jen (東西南北人), Han-pin Tu-i Che (漢濱讀易者), Hai-pin Hsia-shih (海濱下士). His studio name was Tu-i Ts’ao-t’ang (讀易草堂). In his youthful years, the English name he used was Koh Hong-beng or Kaw Hong-beng, phonetic representation of the Chinese characters in Fukien dialect. Later on he used the name Ku Hung-ming. He was fluent in a number of languages, Malay, Tamil, English, German, French, Latin, while he also had some knowledge of Greek and Italian. In the Draft History of Ch’ing (清史稿), the official postings of Ku were chronicled:

“He was deputy director of the Provincial Bureau of Foreign Affairs (外務部員外郎), then raised to director (郎中), and then promoted to left assistant administrator (左承)”.

Deputy director was a sinecure official posting, it belonged to the lower fifth rank within nine ranks or p’in (品). He then rose to the position of director which belonged to the principal fifth rank. He was eventually promoted to left assistant administrator. There were two assistants, the right and the left, under a minister or vice minister. They were equivalent to the position of secretary. This was the reason Ku Hung-ming translated his official title as “Secretary-Interpreter to His Excellency Chang Chih-tung, Viceroy of Hukuang” (Hukuang means Hunan and Hupeh Provinces).

Ku Hung-ming wrote two books in Chinese: Chang Wen-hsiang mu-fu chi-wen (張文襄幕府紀聞 Recollections from the Administration Office of Chang Wen-hsiang), published in the 2nd year of the Hsüan-t’ung reign (1910); and Tu-i Ts'ao-t’ang wen-kao (讀易草堂文稿 Drafts from Tu-i Ts’ao-t’ang), published in the 4th year of the Republic (1915).

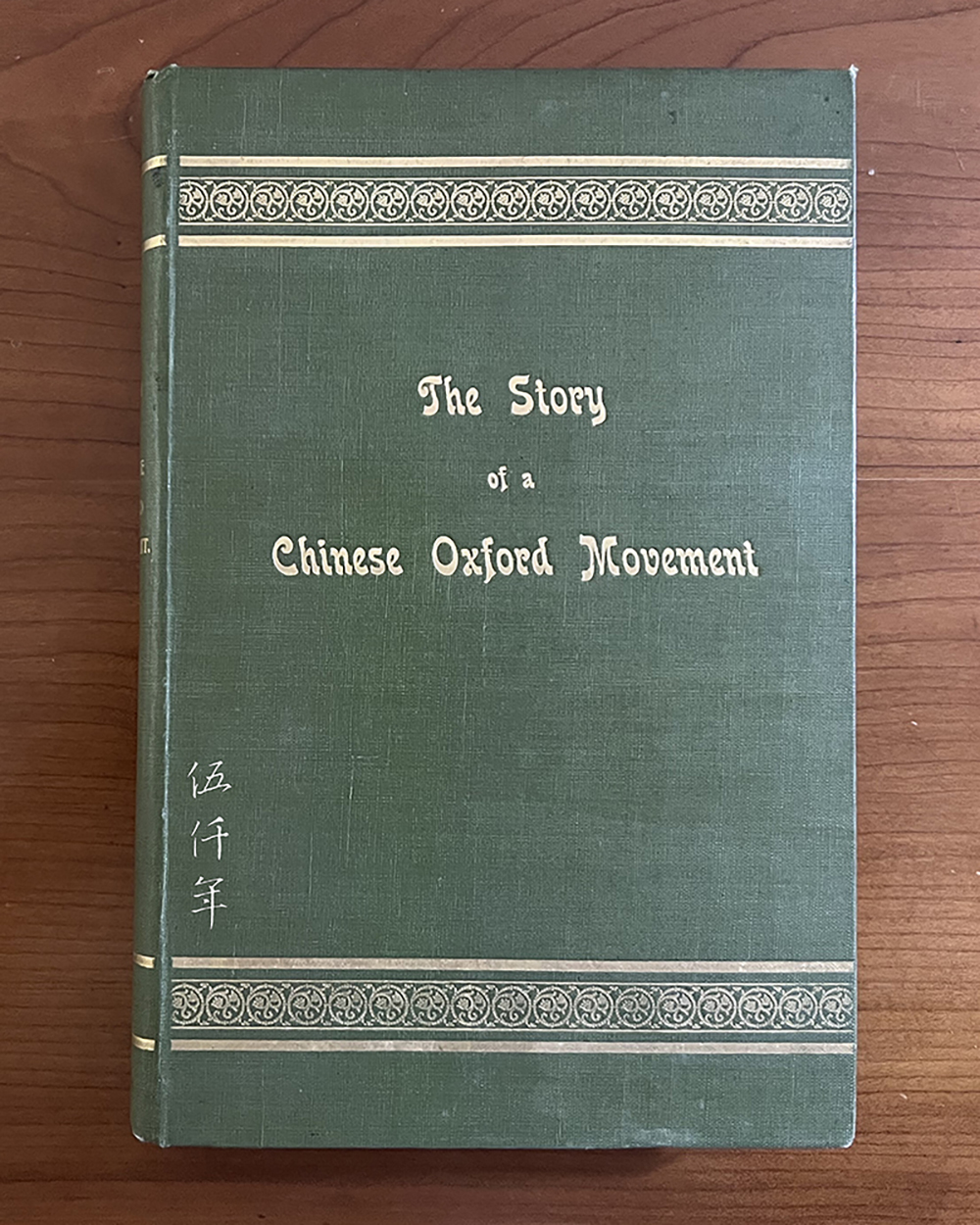

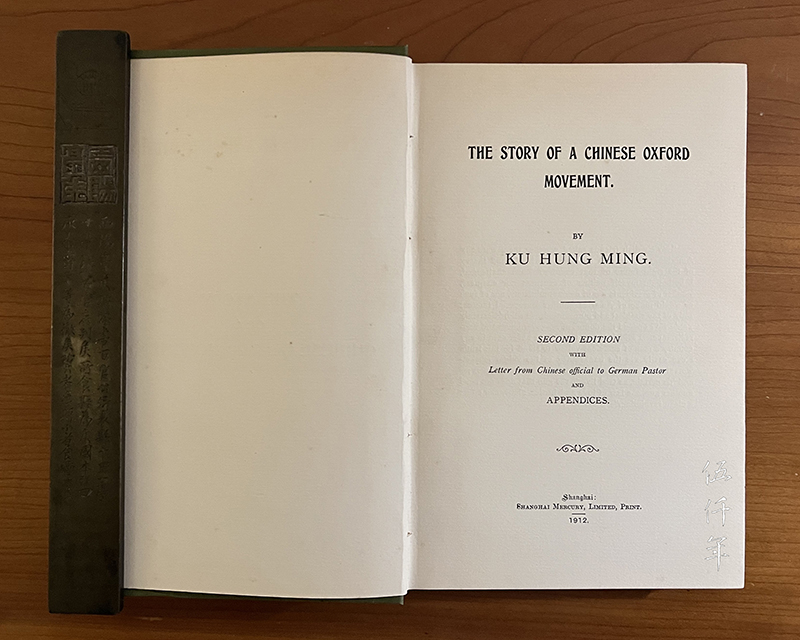

Front cover of The Story of a Chinese Oxford Movement

Title page of The Story of a Chinese Oxford Movement

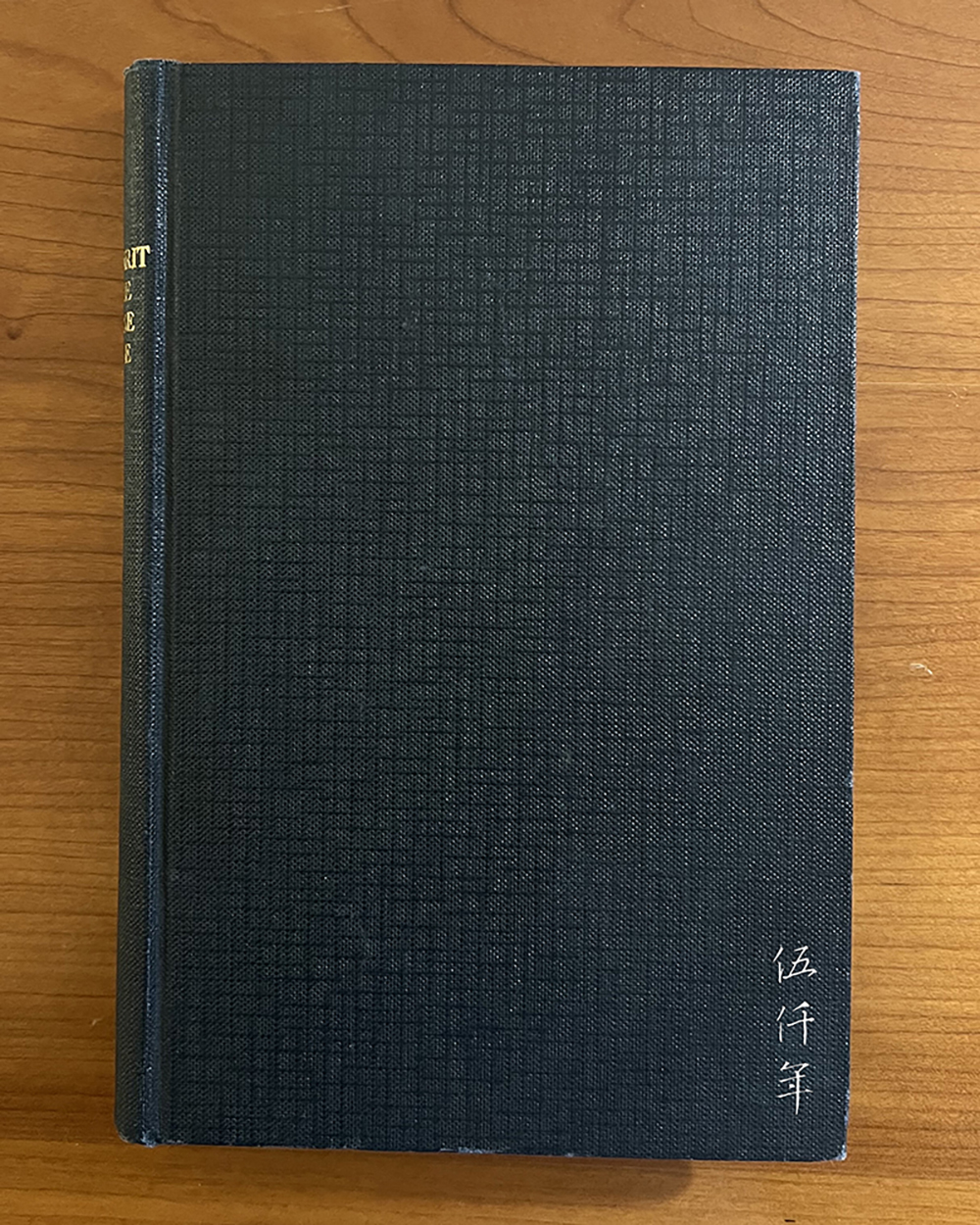

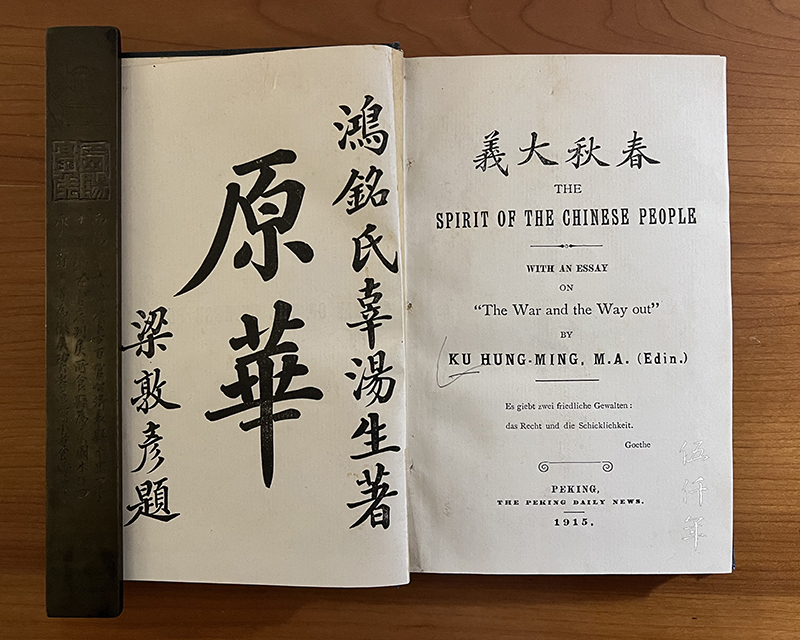

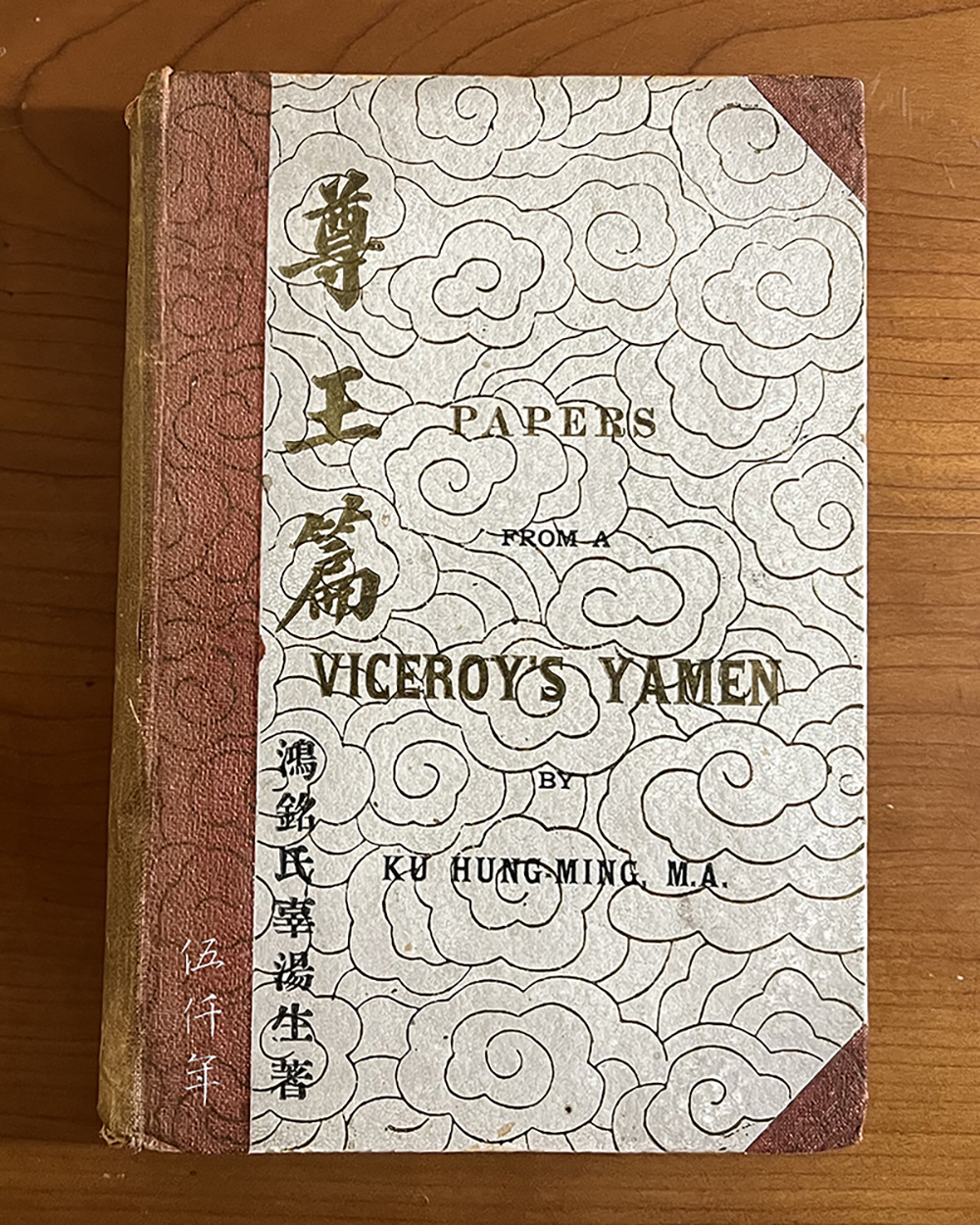

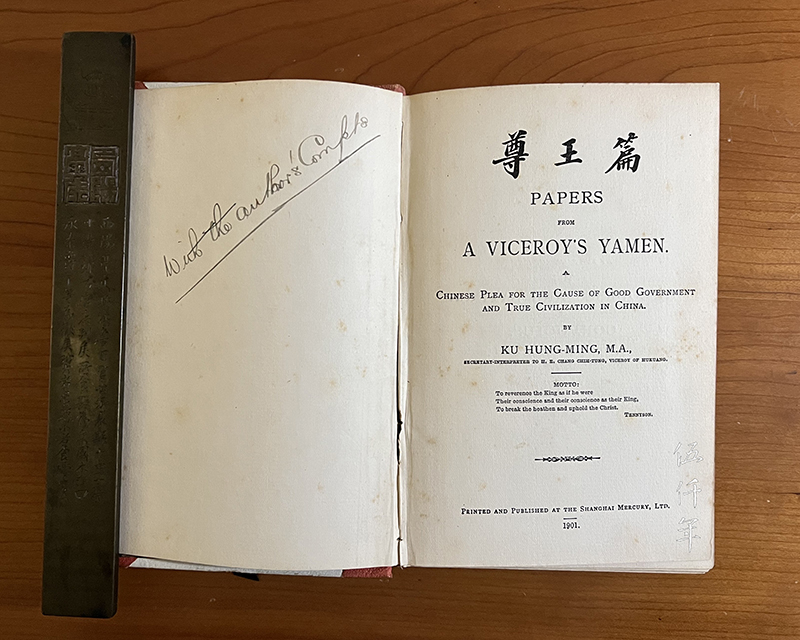

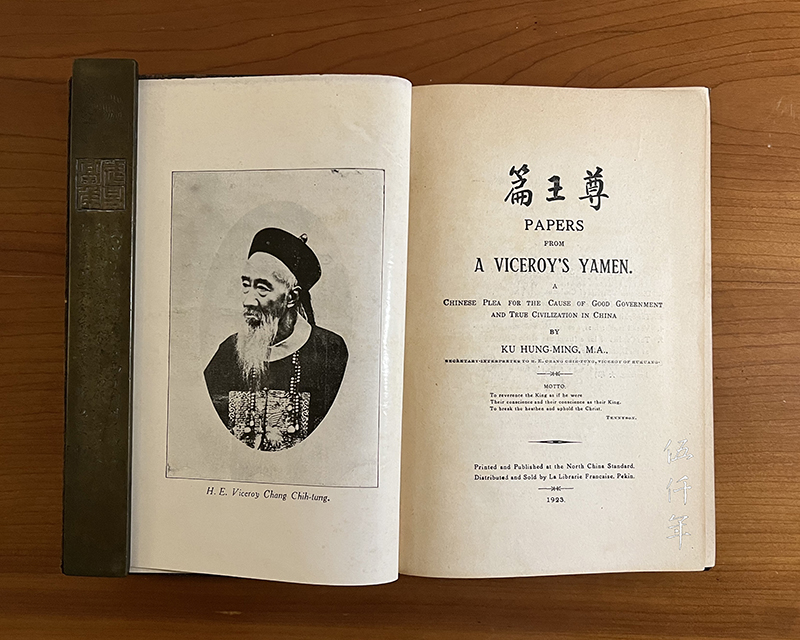

He wrote three books in English: Papers from a Viceroy’s Yamen. A Chinese Plea for the Cause of Good Government and True Civilization (尊王篇), published in the 27th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1901); The Story of a Chinese Oxford Movement (清流傳或中國牛津運動事), published in the 2nd year of the Hsüan-t’ung reign (1910); and The Spirit of the Chinese People (春秋大義), published in the 4th year of the Republic (1915).

Front cover of The Spirit of the Chinese People

Title page of The Spirit of the Chinese People

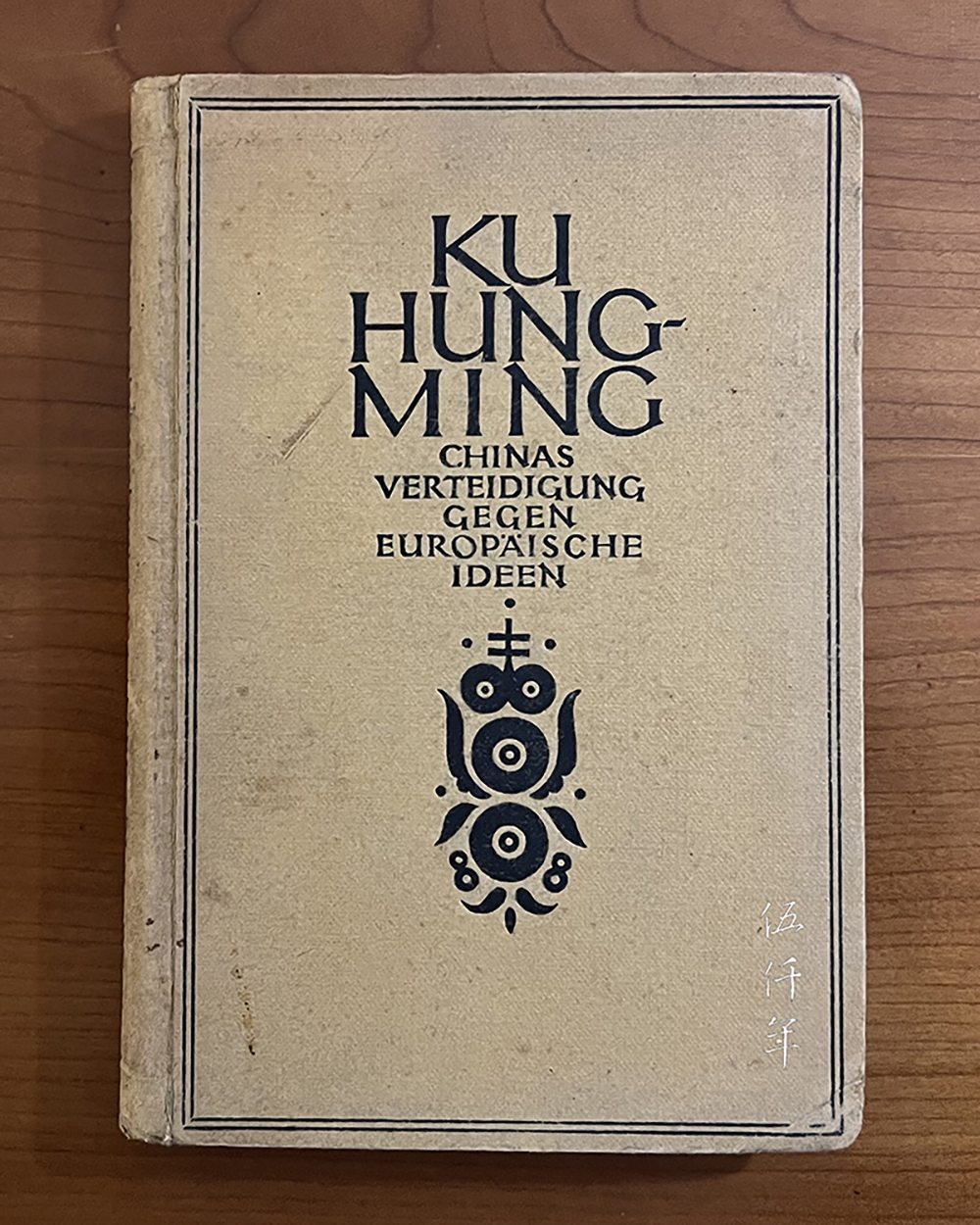

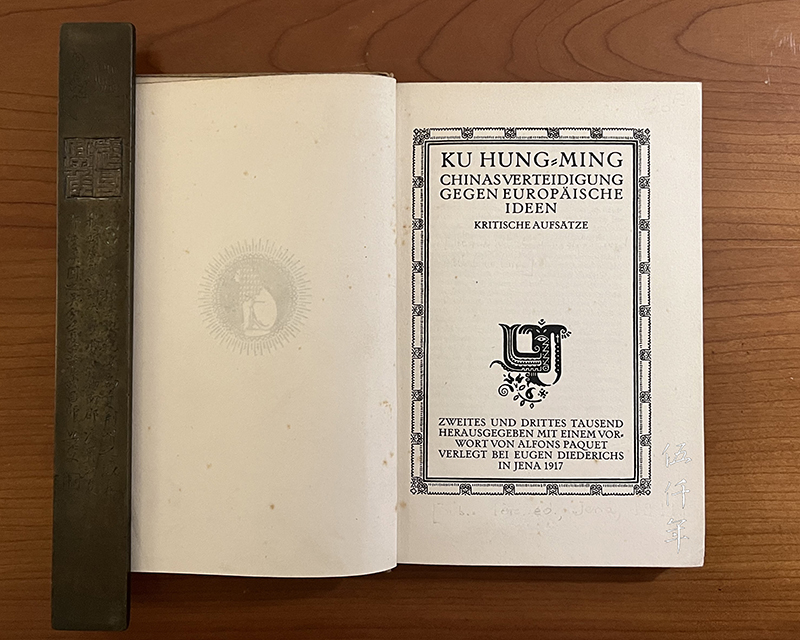

Although Ku Hung-ming was fluent in German, his works published in German were translations by distinguished scholars. The Spirit of the Chinese People was translated into Der Geist des Chinesischen Volkes und der Ausweg aus dem Krieg by Oscar A. H. Schmitz, published in the 5th year of the Republic (1916); Chinas Verteidigung Gegen Europaische Ideen, Kritische Aufsatze was translated by Richard Wilhelm and compiled by Alfons Paquet, published in the 6th year of the Republic (1917); Vox Clamantis. Betrachtungen über den Krieg und anderes was translated by Heinrich Nelson, published in the 9th year of the Republic (1920).

Front cover of Chinas Verteidigung Gegen Europaische Ideen, Kritische Aufsatze

Title page of Chinas Verteidigung Gegen Europaische Ideen, Kritische Aufsatze

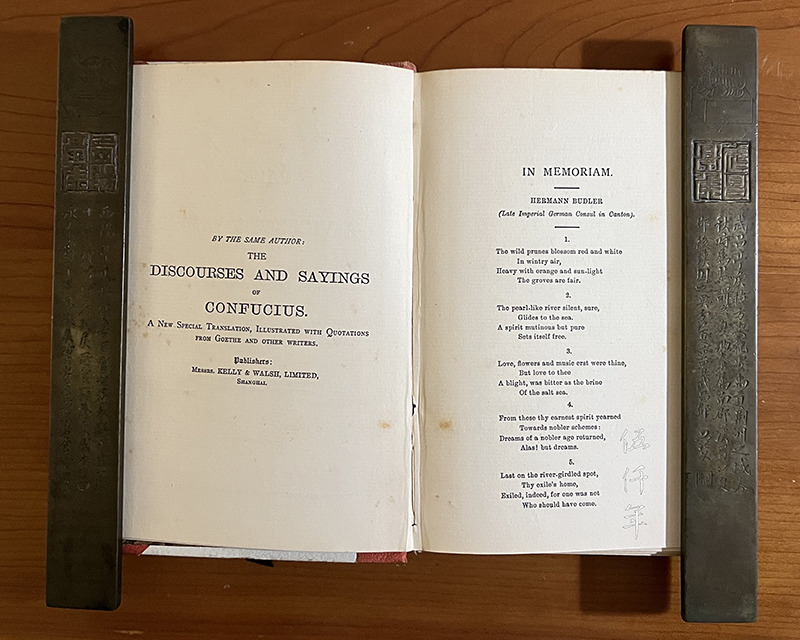

Ku Hung-ming translated the following works from Chinese to English: The Discourses and Sayings of Confucius. A New Practical Translation, Illustrated with Quotations from Goethe and Other Writers (論語), published in the 24th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1898); and The Conduct of Life or The Universal Order (中庸), published in the 32nd year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1906).

Portrait of Ku Hung-ming and friend, 1920

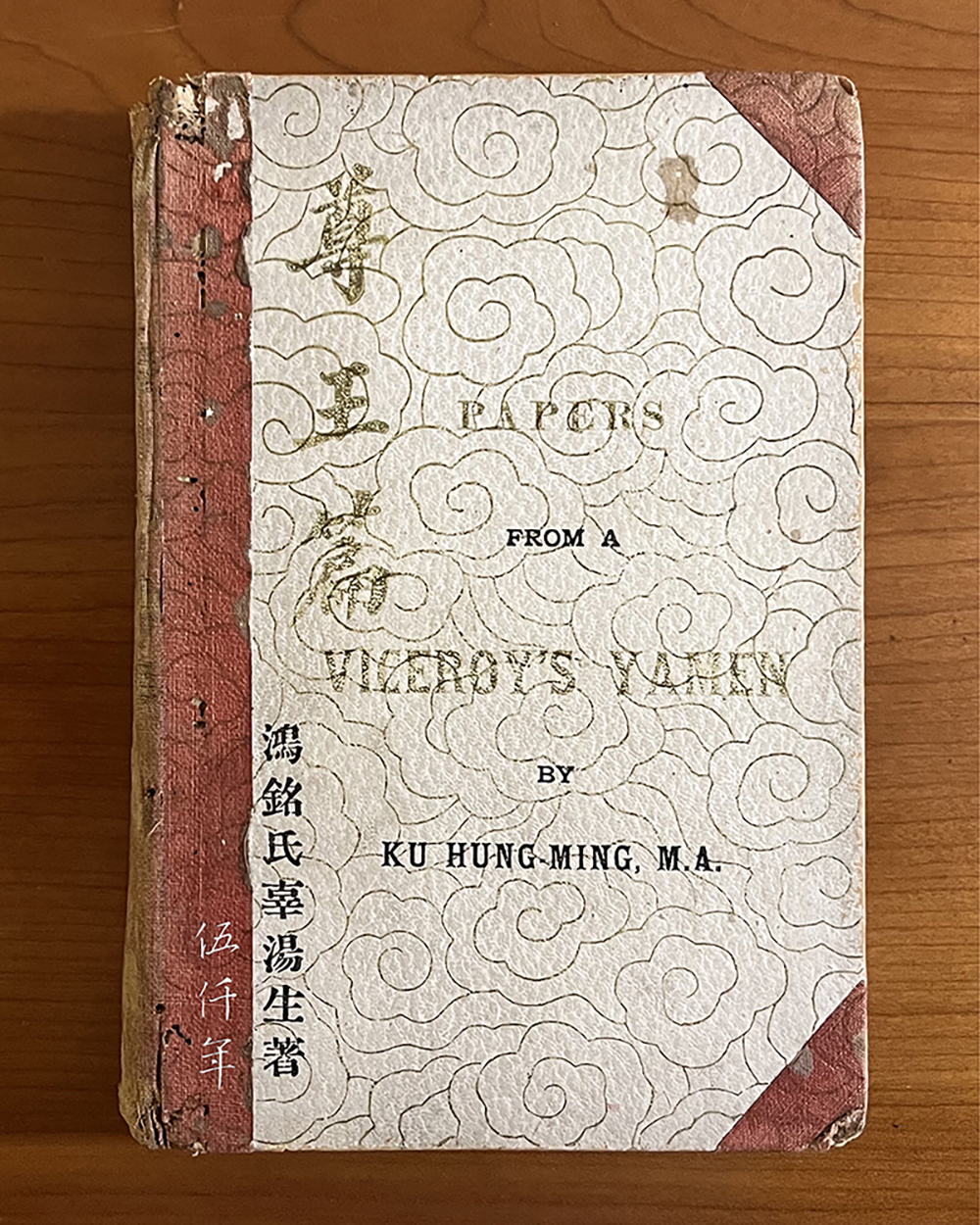

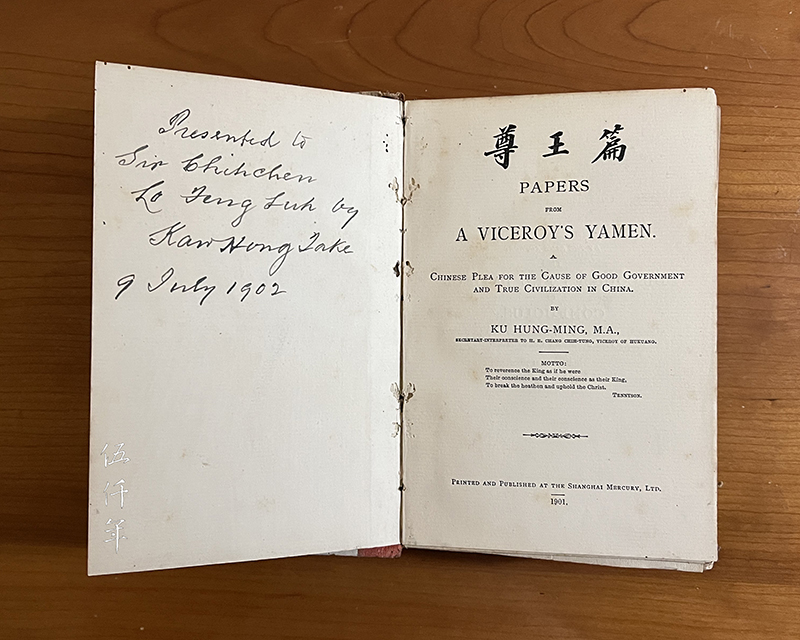

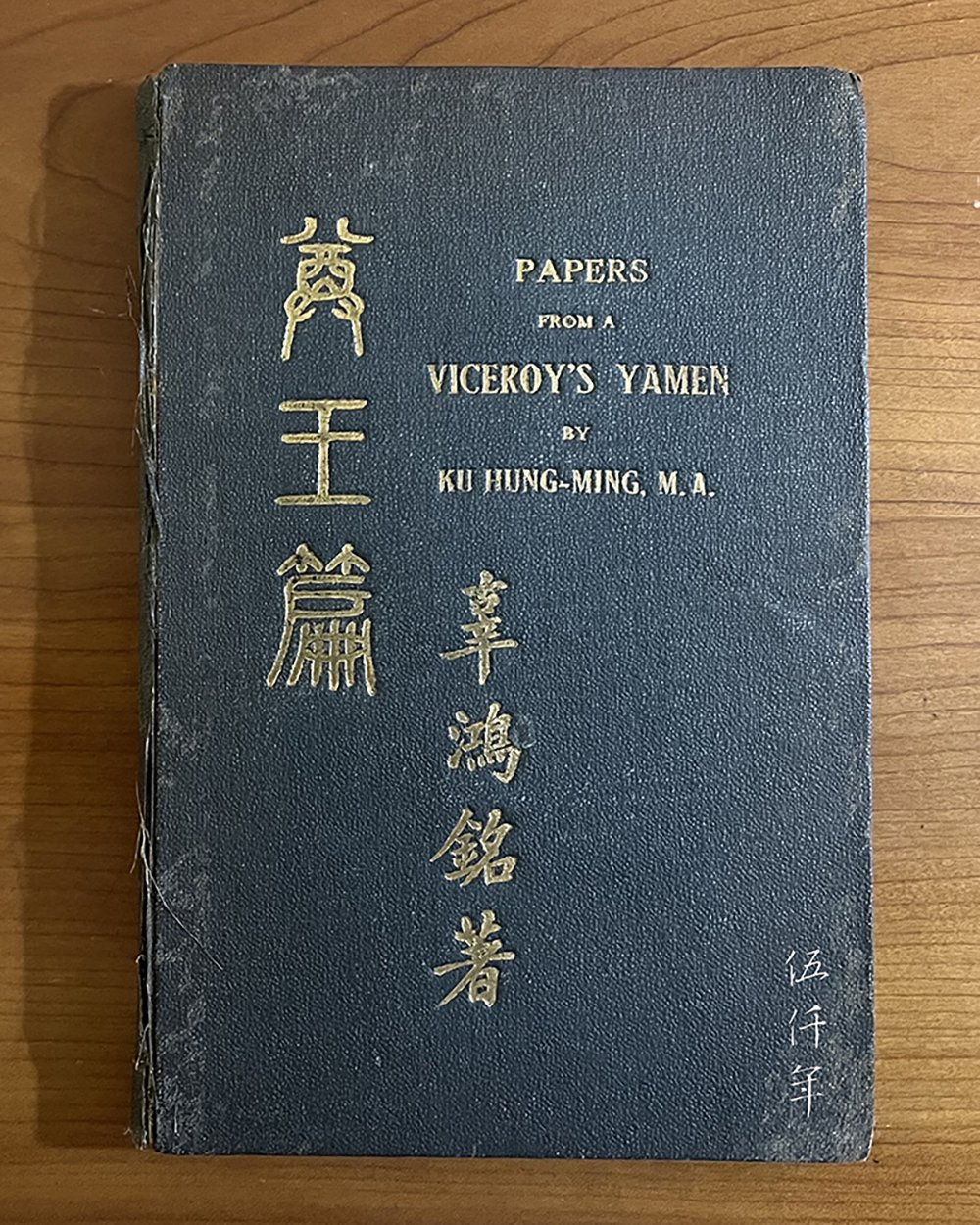

The first published work by Ku Hung-ming is The Discourses and Sayings of Confucius, printed in the 24th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1898) by Shanghai’s Kelly & Walsh, Ltd. The second published work is Papers from a Viceroy’s Yamen, printed between November and December in the 27th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1901) by Shanghai Mercury, Ltd.

In the Studio of Prunus Ode, there are two inscribed first editions of Papers from a Viceroy’s Yamen, printed in the 27th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1901), and an inscribed second edition printed in the 12th year of the Republic (1923) by North China Standard.

Front cover of the first edition of Papers from a Viceroy’s Yamen. A Chinese Plea for the Cause of Good Government and True Civilization

Title page of the first edition of Papers from a Viceroy’s Yamen. A Chinese Plea for the Cause of Good Government and True Civilization

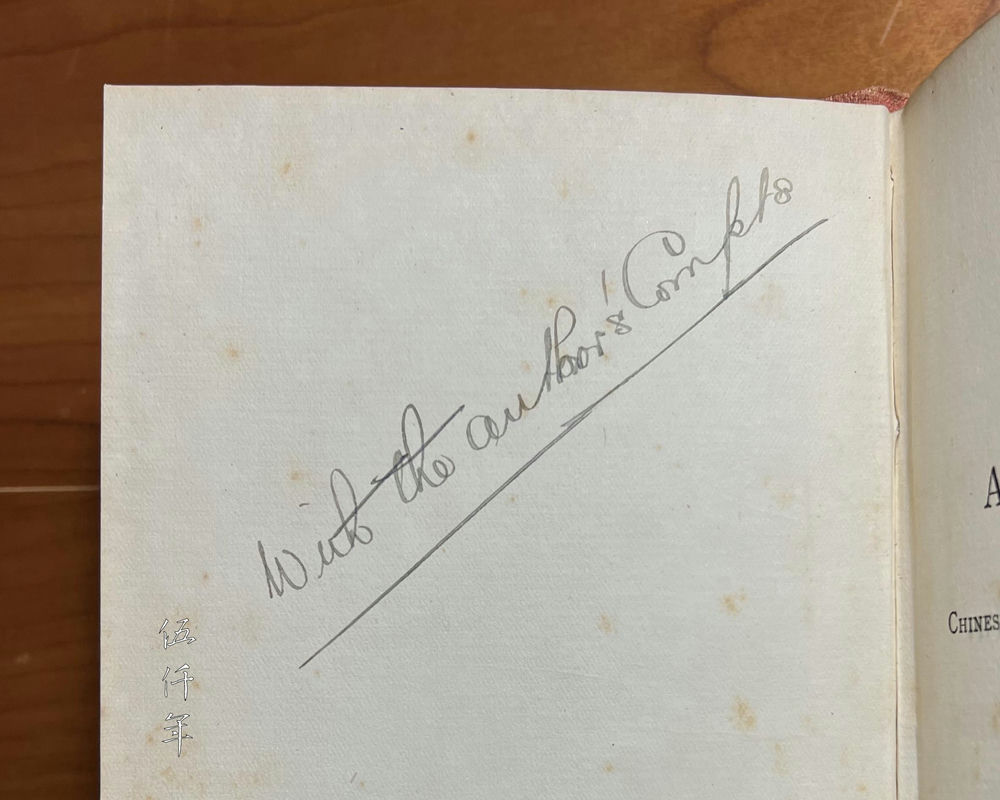

Inscription by Ku Hung-ming

One of the inscribed first editions of Papers from a Viceroy’s Yamen has an inscription in pencil: “With the author’s Compts.” One suspects this is an inscription from the 27th year of the Kuang-hsü reign.

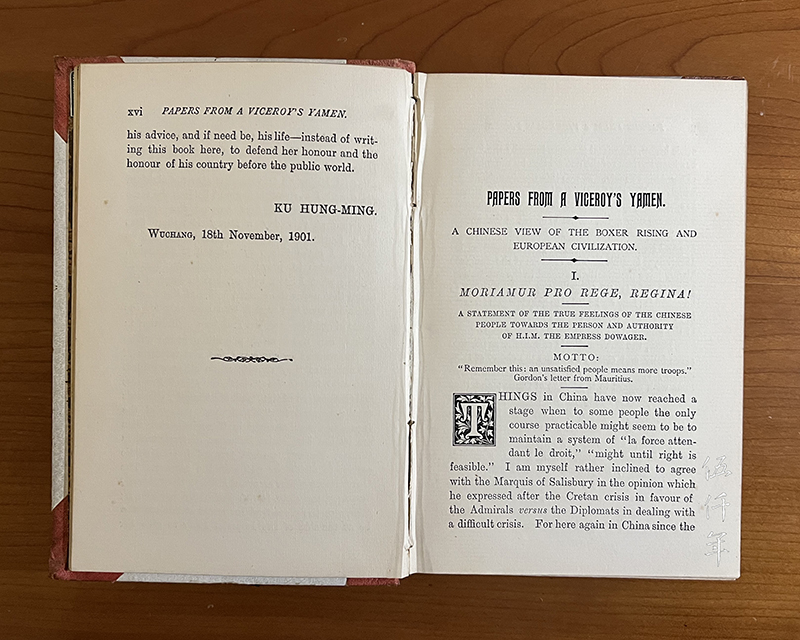

First Chapter: Moriamur Pro Rege, Regina! A Statement of the True Feelings of the Chinese People Towards the Person and Authority of H. I. M. The Empress Dowager

Second Chapter: Defensio Populi ad Populos, or the Modern Missionaries Considered in Relation to the Recent Riots

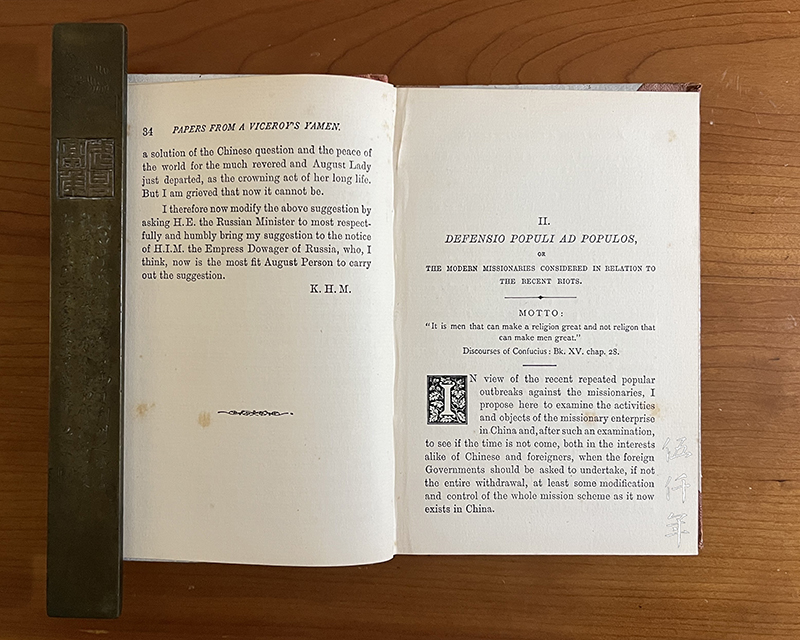

There are five chapters in Papers from a Viceroy’s Yamen, they are actually a compilation of nine separate articles published in a number of newspapers. The first chapter: Moriamur Pro Rege, Regina! A Statement of the True Feelings of the Chinese People Towards the Person and Authority of H. I. M. The Empress Dowager; was first published between January and February 1901 in Japan Mail of Yokohama. At that time the Eight-Nation Alliance had already occupied Peking. The second chapter: Defensio Populi ad Populos, or the Modern Missionaries Considered in Relation to the Recent Riots; was first published in the 17th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1891) in Shanghai. At the time the expectant circuit appointee of Shensi Province, Chou Chen-han (周振漢), had been distributing large quantities of illustrated books against Christianity, anti-western sentiment was rampant along the banks of Yang-tzu Chiang (楊子江). The third chapter: For the Cause of Good Government in China, Practical Conclusions; was first published in the 27th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1901) in Japan Mail.

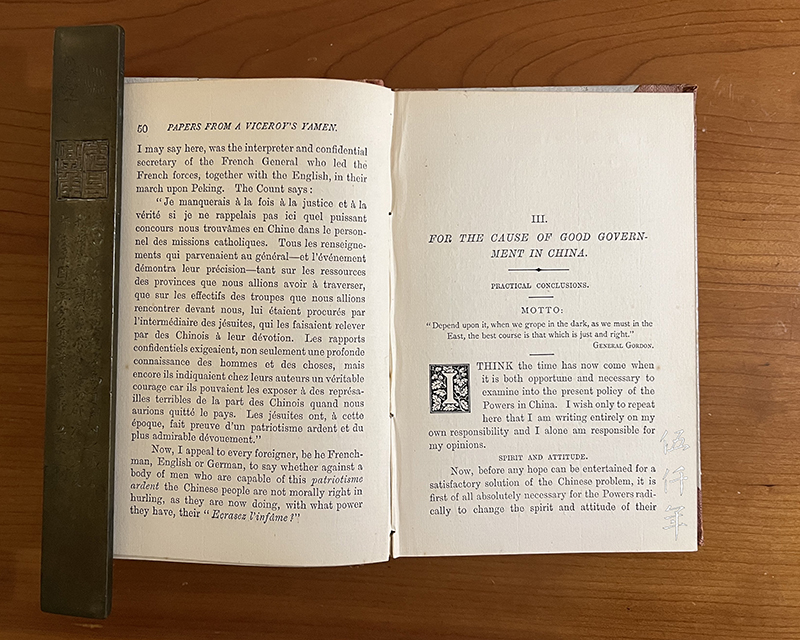

Third Chapter: For the Cause of Good Government in China, Practical Conclusions

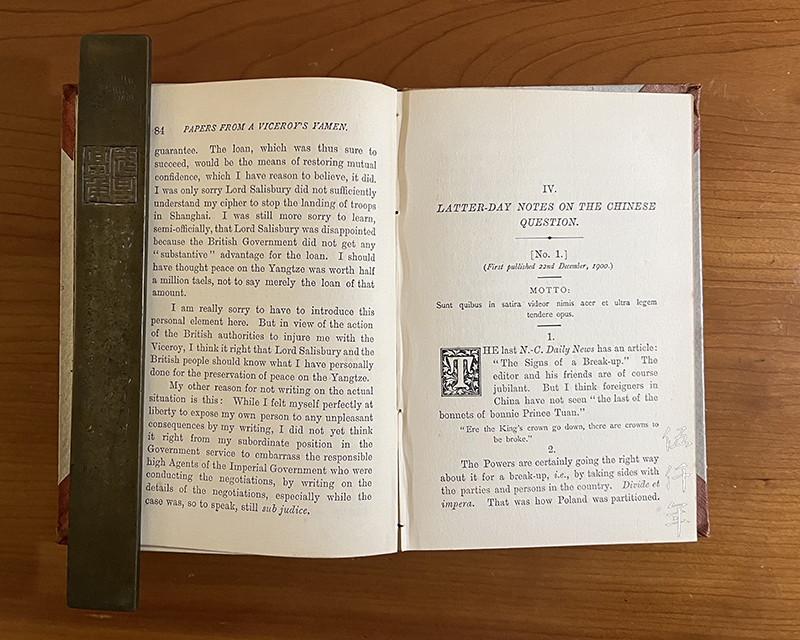

Section one of the fourth Chapter: Latter-Day Notes on the Chinese Question, No. 1

Section one of the fourth chapter: Latter-Day Notes on the Chinese Question, No. 1; was first published on 22nd December 1900 in Japan Mail. Section two of the fourth chapter: Latter-Day Notes on the Chinese Question, No. 2; was first published on 5th January 1901 in Japan Mail. Section three of the fourth chapter: Latter-Day Notes on the Chinese Question, No. 3; was first published on 12th January 1901 in Japan Mail. Section four of the fourth chapter: Latter-Day Notes on the Chinese Question, No. 4; was first published on 16th March 1901 in Japan Mail. Section five of the fourth chapter: Latter-Day Notes on the Chinese Question, No. 5; was first published on 25th May 1901 in Japan Mail. The fifth chapter: Civilization and Anarchy, or the Moral Problem of the Far Eastern Question; was first published in Papers from a Viceroy’s Yamen, and was reprinted twenty one years later, in the 1922 edition of The Spirit of the Chinese People. Ku Hung-ming was evidently deeply attached and pleased with this article.

Fifth Chapter: Civilization and Anarchy, or the Moral Problem of the Far Eastern Question

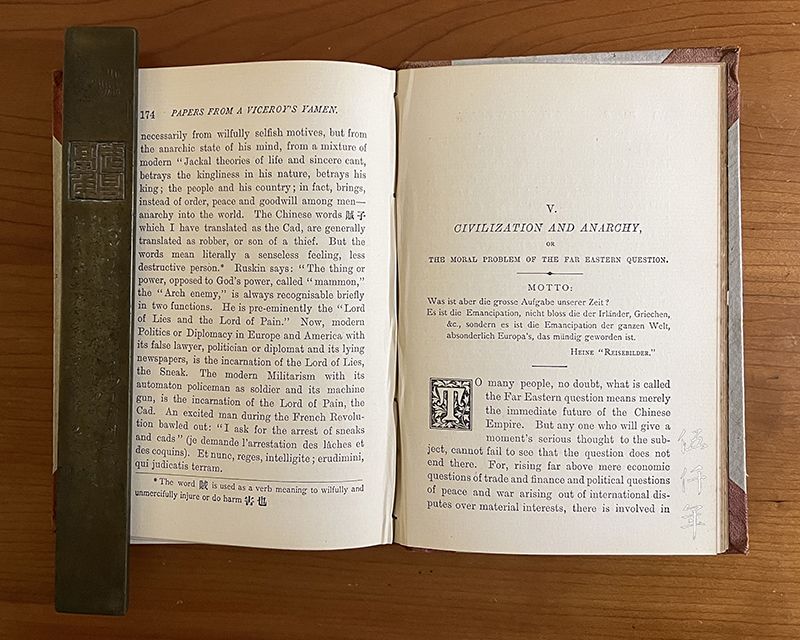

Behind the title page, there is a poem In Memoriam Hermann Budler (1846-1893), the German consul in Canton. At the end of the poem, Ku wrote in a footnote:

“This poem was written and published at the time of Mr. Budler’s death, who shot himself at Canton in 1893.”

In Memoriam Hermann Budler by Ku Hung-ming

In late Ch’ing, there was no shortage of Western sympathizers of China’s political predicament. Those who were resolute professed conspicuous stances against Western religious activities and military encroachments, such as Reginald F. Johnston, the British tutor to the last emperor; Hermann Budler, the German consul, and others. It was known that Budler detested missionaries and Christmas festivity, he was particularly enthralled by the ideal of a just and communal world. During his seventeen years in China, he was hampered by numerous diplomatic postings, in which he was stifled and demoralized. By the time he abruptly took his own life, his torment and remorse must have been unbearable. It is indeed heart rending.

Ku Hung-ming placed this poem at the front of the book, surely to mourn his close friend, but also to broach the principles of Western morality that was represented by Budler, as an admonition to the world. In the mind of Ku Hung-ming, the true principles of Western morality, the doctrines of Confucianism, were two separate paths to the same end.

Portrait of Ku Hung-ming with inscription by Ku

That the works of Ku Hung-ming were appreciated by Americans and Europeans, especially sought-after in Germany, and influential in public opinions, were because he used western cultural perspectives to explain Chinese culture. Earlier writers did not attain this level of sophistication. A number of eminent men in China and abroad admired Ku Hung-ming and wrote about him. Some of them are:

Portrait of William Somerset Maugham

W. Somerset Maugham (1874-1965), English writer, depicted Ku as The Philosopher in On a Chinese Screen, published in 1922.

Portrait of Hermann von Keyserling

Count Hermann von Keyserling (1880-1946), German philosopher, depicted Ku in The Travel Diary of a Philosopher, published in 1925.

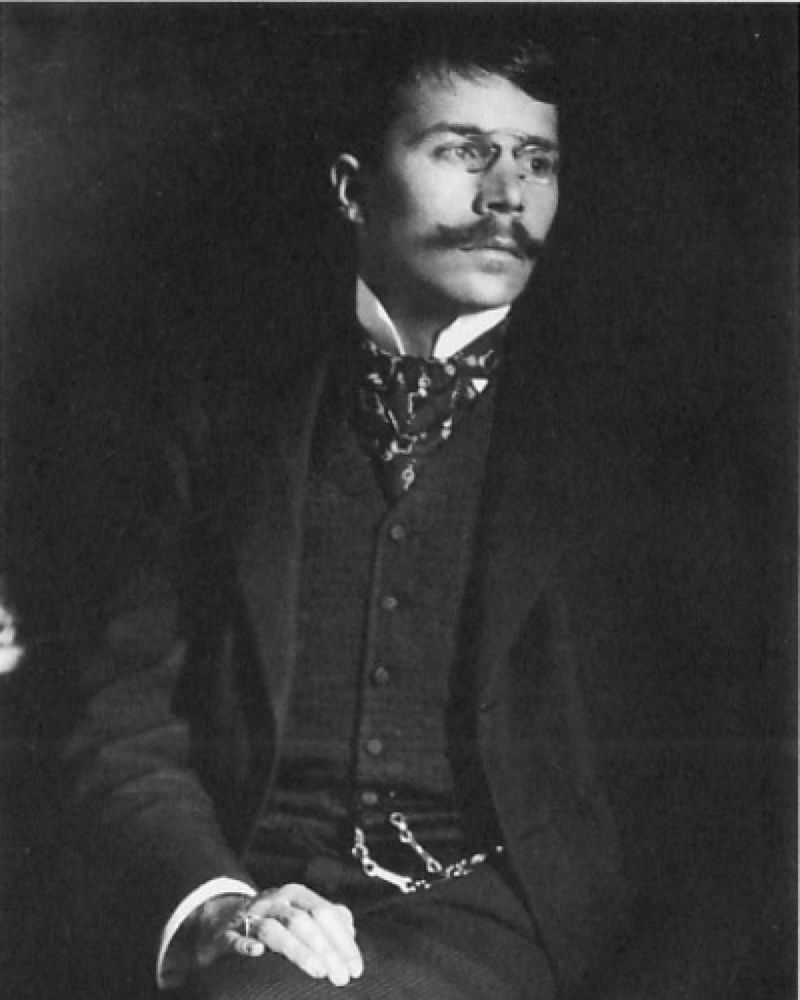

Portrait of Oscar A. H. Schmitz

Oscar A. H. Schmitz (1873-1931), German writer, translated The Spirit of the Chinese People into German and wrote the preface, published in 1916.

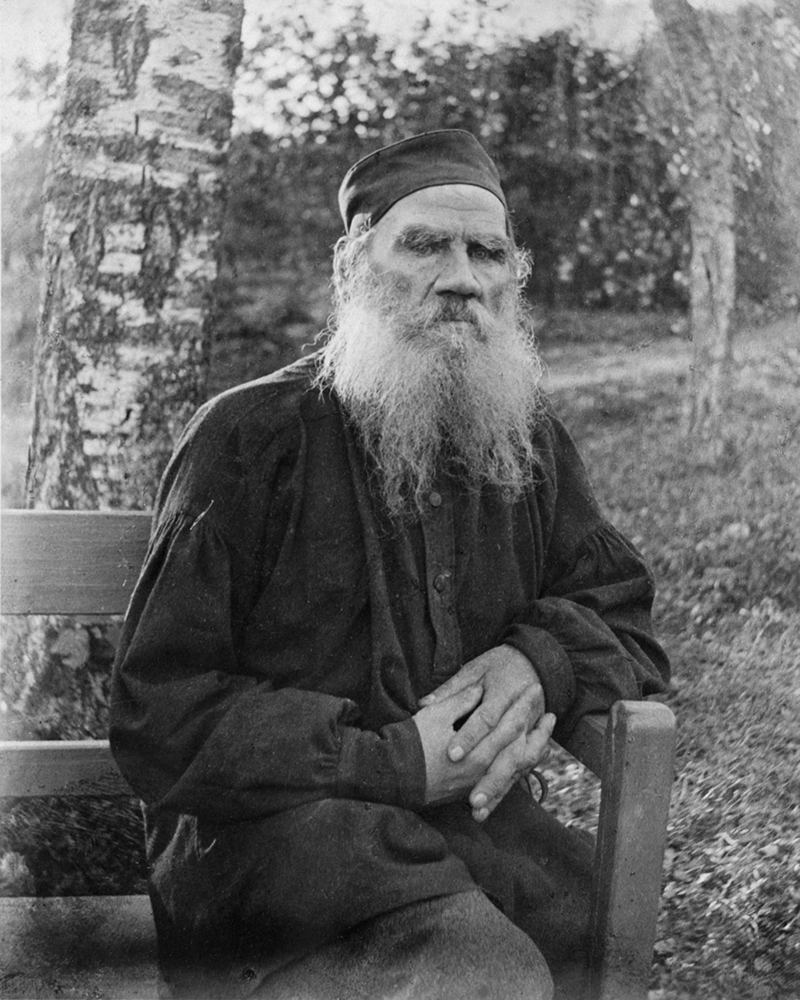

Portrait of Leo Tolstoy

Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910), Russian writer, received Papers from a Viceroy’s Yamen from Ku in 1906 and replied with Letter to a Chinese Gentleman, translated into English and published in 1907. Tolstoy regarded this as one of his most important writings.

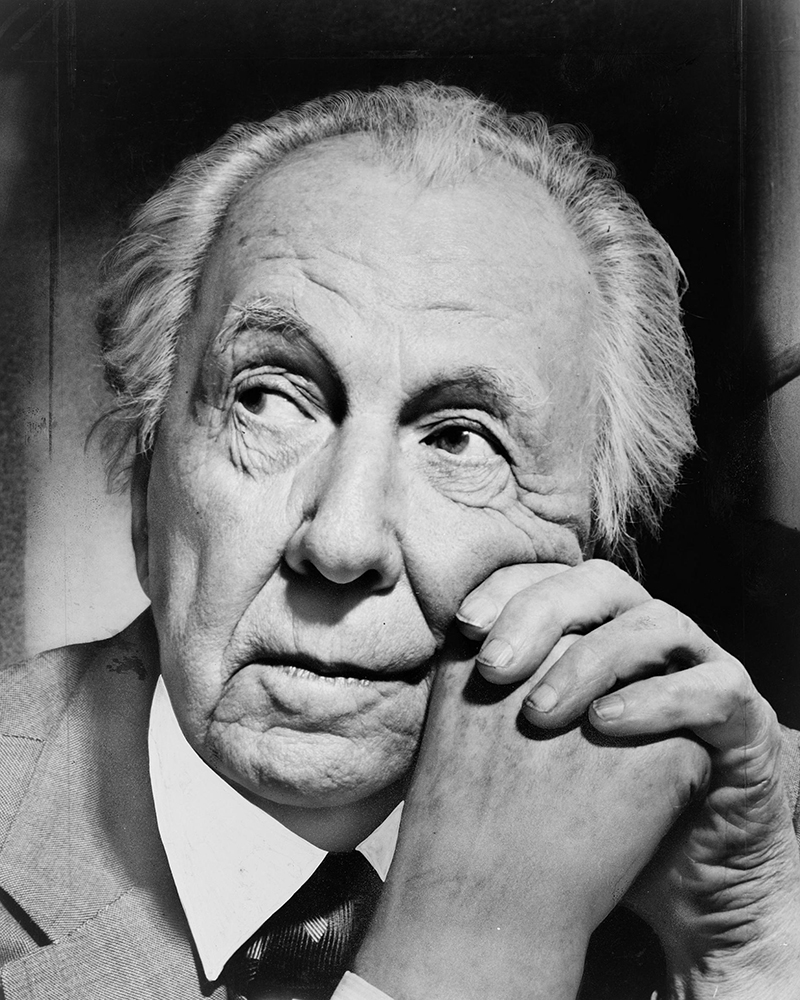

Portrait of Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959), American architect, depicted Ku in An Autobiography, published in 1932.

Portrait of Akutagawa Ryūnosuke

Akutagawa Ryūnosuke (芥川龍之介 1892-1927), Japanese writer, depicted Ku in Travels in China, published after a trip to China in 1921.

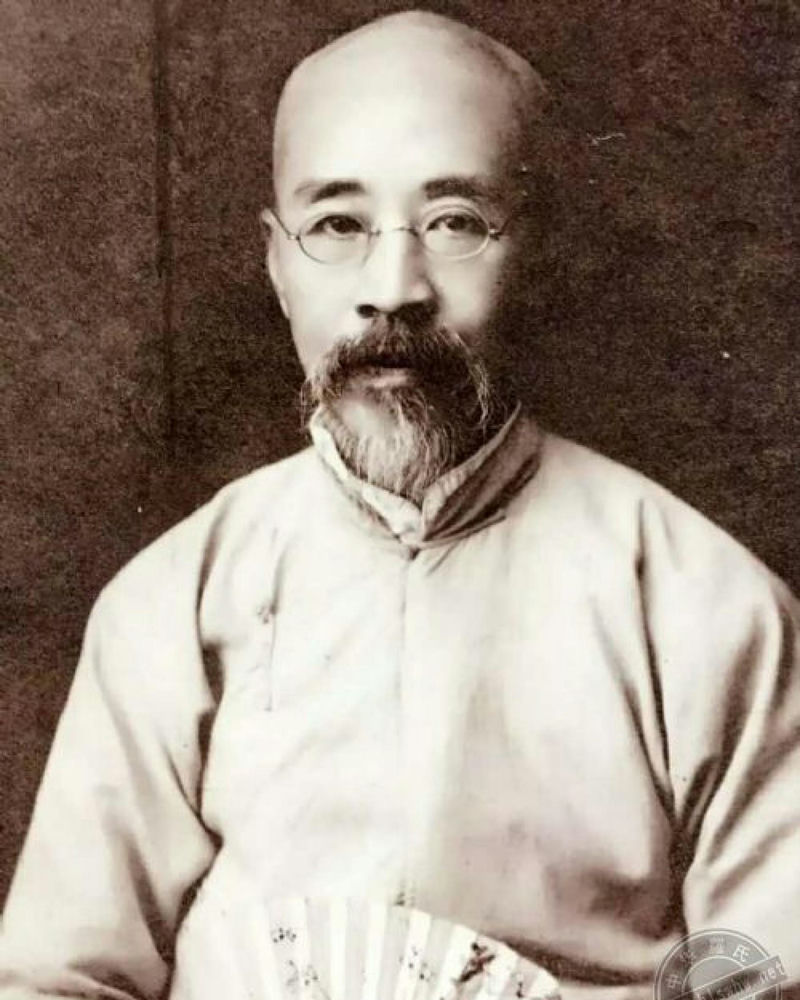

Portrait of Lo Chen-yü (羅振玉)

Lo Chen-yü (羅振玉 1866-1940), Chinese scholar, wrote Wai-wu pu zuo-ch’eng Ku-chün ch’uan (外務部左承辜君傳 Biography of Mr. Ku, Left Assistant Administrator of the Provincial Bureau of Foreign Affairs).

No other Chinese literary figure at that time could solicit the high esteem abroad enjoyed by Ku Hung-ming.

Front cover of the second copy of Papers from a Viceroy’s Yamen. A Chinese Plea for the Cause of Good Government and True Civilization

Title page of the second copy of Papers from a Viceroy’s Yamen. A Chinese Plea for the Cause of Good Government and True Civilization

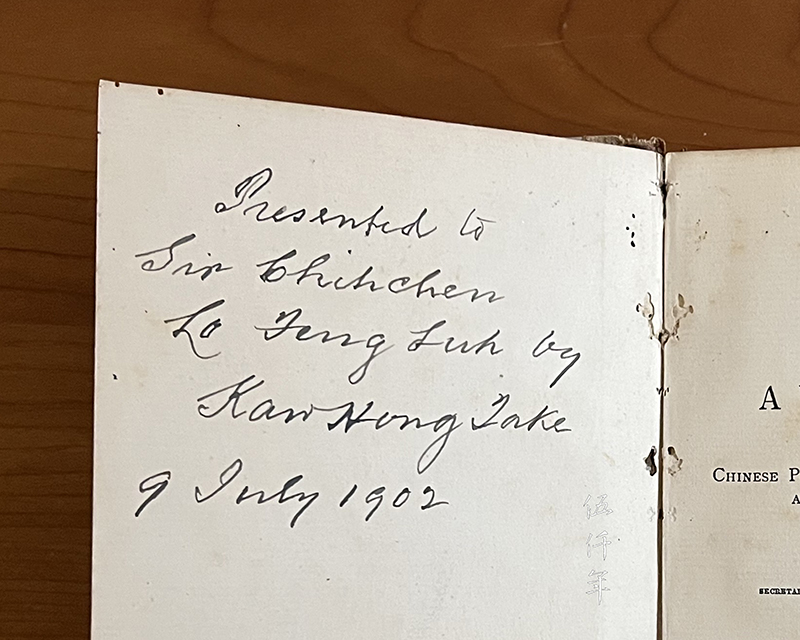

Inscription by Kaw Hong-take to Sir Chichchen Lo Feng-luh, Chinese minister to Britain

There is a another copy of the first edition of Papers from a Viceroy’s Yamen in the Studio of Prunus Ode. It was inscribed by Ku Hung-ming’s elder brother Kaw Hung-take (辜鴻德) to the Chinese minister to Britain Lo Feng-luh (羅豐祿). The inscription reads:

Presented to

Sir Chihchen

Lo Feng Luh by

Kaw Hong Take

9 July 1902

Kaw Hong-take (辜鴻德) was born in 1843, elder brother of Ku Hung-ming. Hong-take was fourteen years his senior, and Hung-ming looked up upon him like son to father. The English name Kaw Hong-take was phonetic representation of the Chinese characters in the Fukien dialect. He was proficient in English, but could only command spoken Chinese. He was born in George Town of Penang, British Malaya. Around 1864, he left for Fukien and started a trading company named Kaw Hong Take & Co. In 1886 he was appointed Justice of the Peace by the British government. Biographical material claims that Kaw Hong-take passed away in 1901. According to the inscription date of 9th July 1902 in this book, 1901 is clearly not the year of his death. Kaw Hong-take might have passed away in the later half of 1902, if not, his year of death would likely be near.

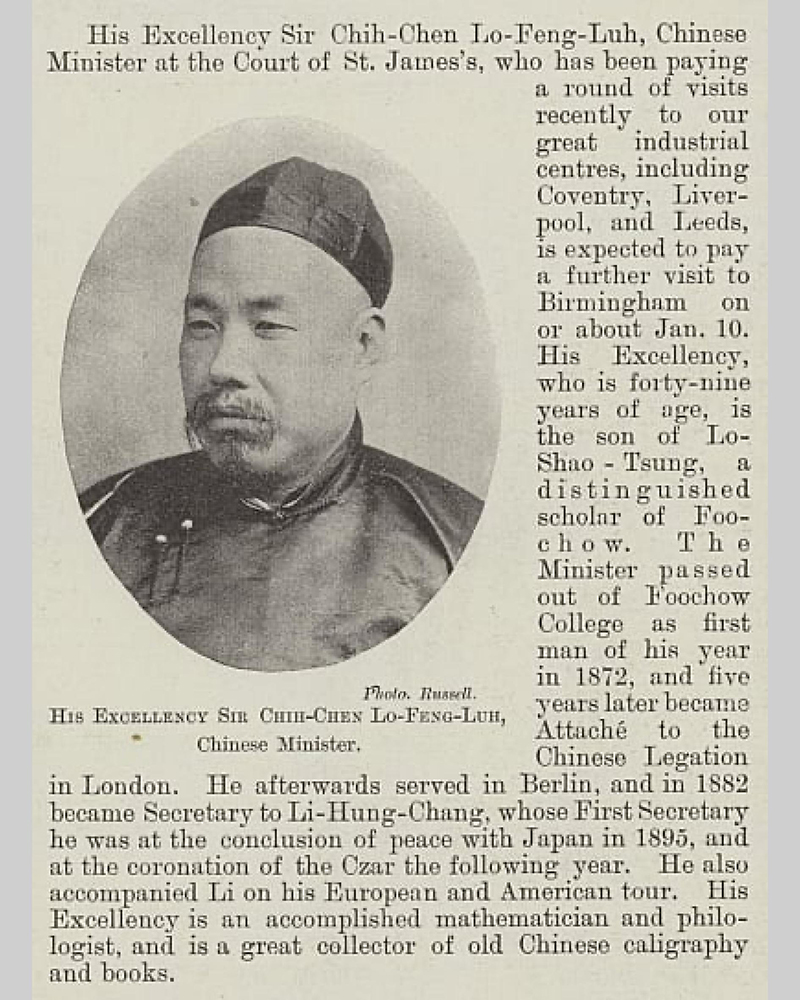

Portrait of Sir Chihchen Lo Feng-luh in newspaper

This book is a gift to the Chinese minister in Britain, Lo Feng-luh (羅豐祿 1850-1903). His tzu was Chi-ch’en (稷臣 or Chih-chen), native of Min-hsien, Fukien Province. In the 11th year of the T’ung-chih reign (1872), he graduated from Fukien Shipping and Polity School, in the 3rd year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1877), he enrolled at King’s College London. In the following year, he was appointed interpreter with the British and German Embassies. He returned to China in the 6th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1880), in the 8th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1882), he was English secretary to Li Hung-chang (李鴻章), and was appointed director of the Taku Naval Dockyard in Tientsin. In the 11th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1885), he was deputy director of Tientsin Naval College. In the 22nd year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1896), he accompanied Li Hung-chang on a European tour. On arrival in England, he received the honorific title of Sir from the British government. He was also promoted to chief minister of the Imperial Stud and minister to three countries: Britain, Italy and Belgium. In the 27th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1901), he was appointed minister to Russia. He was already ill and could not take up the posting, and died in London on 12th June 1903.

Papers from a Viceroy’s Yamen was first published at the end of 1901. Half a year later, on 9th July 1902, Kaw Hong-take sent this book by his brother from afar to the Chinese minister in Britain, Lo Feng-luh. The deep bond between the brothers is apparent. At the time, Kaw Hong-take and Lo Feng-luh were already in their twilight years, Kaw probably lived for another few months, and Lo lived for twelve more months. This inscribed book is a precious document.

Front cover of a later edition of Papers from a Viceroy’s Yamen. A Chinese Plea for the Cause of Good Government and True Civilization

Inside page with inscription by Ku Hung-ming in a later edition of Papers from a Viceroy’s Yamen. A Chinese Plea for the Cause of Good Government and True Civilization

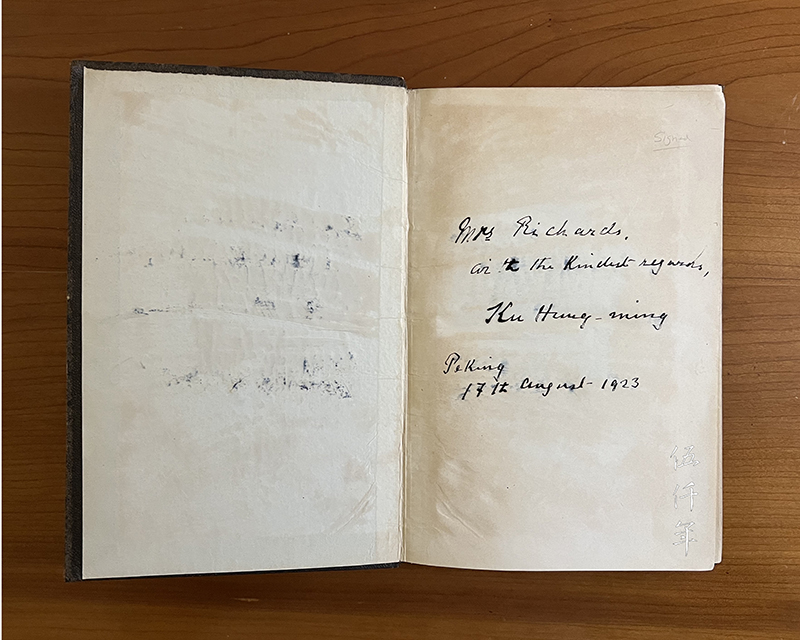

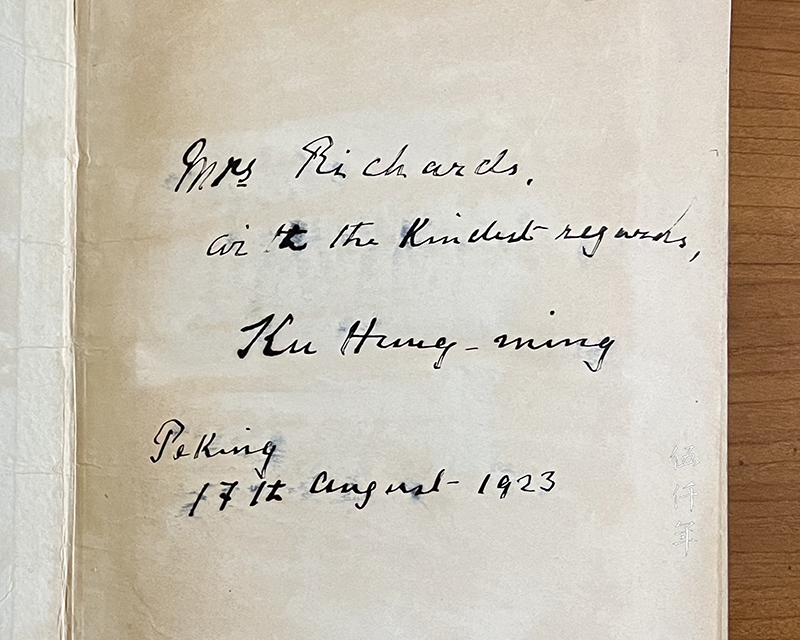

Inscription by Ku Hung-ming

Title page of a later edition of Papers from a Viceroy’s Yamen. A Chinese Plea for the Cause of Good Government and True Civilization

The third copy of Papers from Viceroy’s Yamen in the Studio of Prunus Ode, is a later edition printed in the 12th year of the Republic (1923). There is an ink inscription by Ku Hung-ming. It reads:

Mrs. Richards,

with the kindest regards,

Ku Hung-ming

Peking

17th August 1923.

By 1923, the emperor had already abdicated for twelve years. Ku himself was sixty seven years old and living in Peking. This English inscription is a testimony of Ku’s handwriting in his old age. Ku adopted the identity of i-min (遺民 loyalist) after the fall of the Ch’ing dynasty, leading to personal deprivation and poverty. Although his fame was far and wide, it could not help his livelihood. In his desperation, he voyaged eastward to Japan in the following year to make a living by giving lectures. In the 16th year of the Republic (1927), he returned to China, and passed away in the 17th year of the Republic (1928).

Although Ku Hung-ming was proficient in the knowledge of the West, he returned to China to propagate the knowledge of Confucius. During late Ch’ing when the pursuit for change was prevalent, it could only be expected that Ku Hung-ming’s career in the civil service did not go far. After the Republican Revolution, he swore his allegiance to Confucian Orthodoxy, and declined to join the civil service of the new government. When Westernization pervaded the whole country, he continued to play his lonely classical tune, and was impoverished ever more. Ku Hung-ming was not one who talked about Confucianism in mere rhetoric, he bore the aspirations of Confucianism and rigorously implemented them through his personal conduct.

People often speak about the obstinateness of Ku Hung-ming. Is it not true that Confucian teachings are by nature enduring doctrines ? So why obstinateness? Furthermore, the foresight and topical relevance of Ku Hung-ming’s thoughts are certainly even harder for the world to comprehend. Just by reading a portion of the fifth chapter: Civilization and Anarchy in Papers from a Viceroy’s Yamen, we can perhaps grasp a bigger picture of his world. Some parts say:

“In one word, we believe the true moral culture of modern Liberalism, if not so strict, perhaps, is a much broader one than the medieval culture of Europe derived from the Christian Bible. The one appeals chiefly to the passions of hope and fear in man. The new moral culture on the other hand appeals to the whole intelligent powers of man’s nature: to his reason as well as to his feelings…………

The Liberalism of the last century fought for right and justice. The false Liberalism of to-day fights only for rights and trade privileges. The Liberalism of the past battled for humanity. The false Liberalism of to-day only tries to further the vested interests of capitalists and financiers…………

Under the new civilization freedom for the educated man will not mean liberty to do what he likes, but liberty to do what is right………..

In all matters in the conduct of life, he makes the rule not of authority from without but of reason and conscience from within his one rule to follow. He can live without rulers, but he does not live without laws. Therefore, the Chinese call an educated gentleman a 君子 Koen tzu (君 Koen is the same word as German Koenig or King, a kinglet or a little king of men.)”

These words by Ku Hung-ming over a hundred and twenty years ago can still serve as our constant admonitions, like twilight drum and morning gong.

Portrait of William Somerset Maugham

Between the 8th year and 9th year of the Republic (1919-1920), the British writer Somerset Maugham visited Ku Hung-ming at his residence in Peking. There is a vivid description in his book On a Chinese Screen:

“I passed through a shabby yard and was led into a long low room sparsely furnished with an American roll-top desk, a couple of blackwood chairs and two little Chinese tables. Against the walls were shelves on which were a great number of books: most of them, of course, were Chinese, but there were many, philosophical and scientific works, in English, French and German; and there were hundreds of unbound copies of learned reviews. Where books did not take up the wall space hung scrolls on which in various calligraphies were written, I suppose, Confucian quotations. There was no carpet on the floor. It was a cold, bare, and comfortless chamber. Its somberness was relieved only by a yellow chrysanthemum which stood by itself on the desk in a long vase.”

Such vista and such empathy. One can almost sense the lingering fragrance of the yellow chrysanthemum in the air.

Somerset Maugham also recounted Ku’s words:

“You see that I wear a queue’, he said, taking it in his hands. ‘It is a symbol. I am the last representative of the old China.”

This China that Ku Hung-ming yearned for, a land where compassion and justice can flourish, a land where the virtuous and the sages can roam, is it not the same China we all wish for?

Lingering fragrance of the yellow chrysanthemum