In the 4th year of the Republic (1915), Yüan Shih-k’ai (袁世凱) declared himself emperor. The teacher and student duo Liang Ch’i-chao (梁啓超) and Ts’ai O (蔡鍔, also known as Ts’ai Sung-p’o 蔡松坡), rose to assail him. Liang Ch’i-chao wielded words to alert and bestir the people across the country. Ts’ai O commanded an army to hasten and lead the forces from many provinces. Eventually Yüan was defeated and died. Ts’ai O soon followed with his death. Liang Ch’i-chao then composed Eulogium of Ts’ai Sung-p’o at the Public Memorial Ceremony and Eulogium of Ts’ai Sung-p’o at the Private Memorial Ceremony. By the time of the State Funeral, Liang Ch’i-chao might have exhausted his words to write another Eulogium after the previous two, or he might be tied up by other matters. Subsequently he asked his close friend the provincial graduate T’ang En-p’u (唐恩溥) to ghostwrite for him. It became Eulogium of General Ts’ai Sung-p’o at the State Funeral. This piece of writing was lost for a hundred years, but fortunately it was discovered a few years ago.

Liang Ch’i-chao was born on 26 January in the 12th year of the T’ung-chih reign, the equivalent of 23 February 1873 of the Gregorian calendar. This year, the 112th year of the Republic or 2023 of the Gregorian calendar, is the 150th Birth Anniversary of Liang Ch’i-chao as well as the 141st Birth Anniversary of Ts’ai O. We hereby present Eulogium of General Ts’ai Sung-p’o at the State Funeral in their memories.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

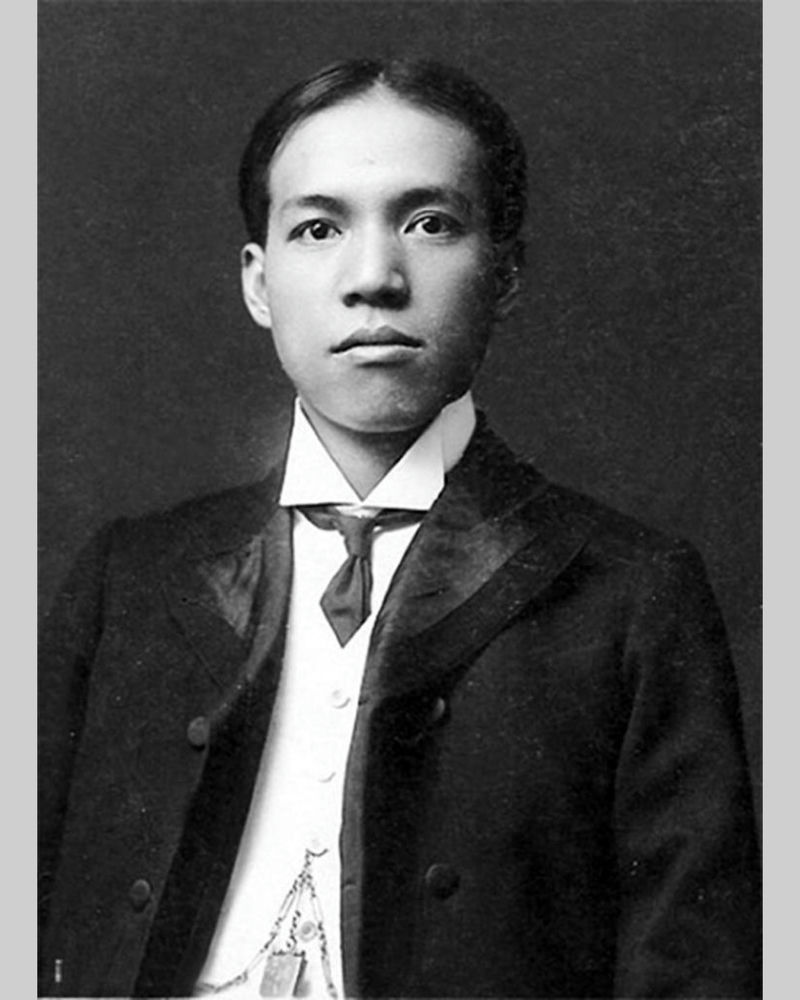

Portrait of Liang Ch’i-chao

Liang Ch’i-chao (梁啟超 1873-1929), hao Jen-kung, intertwined the worlds of politics and literature for over thirty years. His high reputation was extolled throughout the country. Those who admired him came from all walks of life. They sought his writings and solicited his calligraphy. So how burdensome was such obligatory writings? It is difficult to conjecture. However it must be plentiful enough to be unbearable. This is indeed the miserable drudgeries of celebrated literati throughout history. I recall the late years of my deceased friend Mr. Wang P’ei-yüeh (王北岳), who often complained about obligatory writings which were tiring and draining for body and soul. Yet this could hardly match the burden of Liang Ch’i-chao! As a consequence Liang Ch’i-chao engaged the ghostwriter.

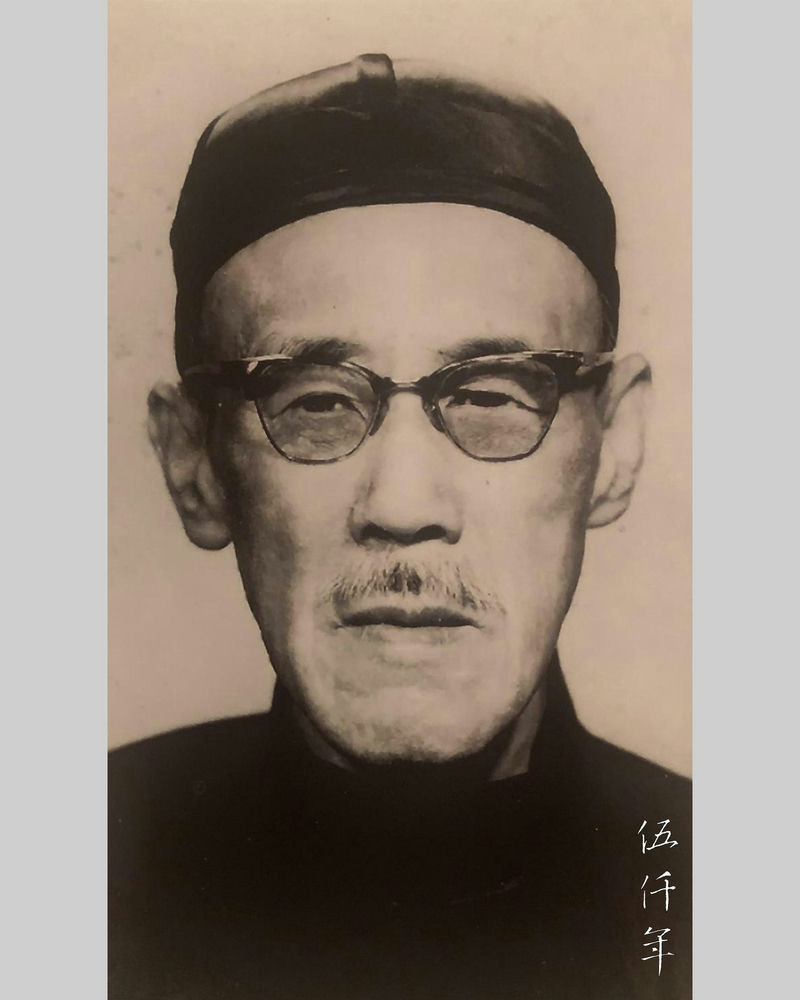

Portrait of T’ang En-p’u

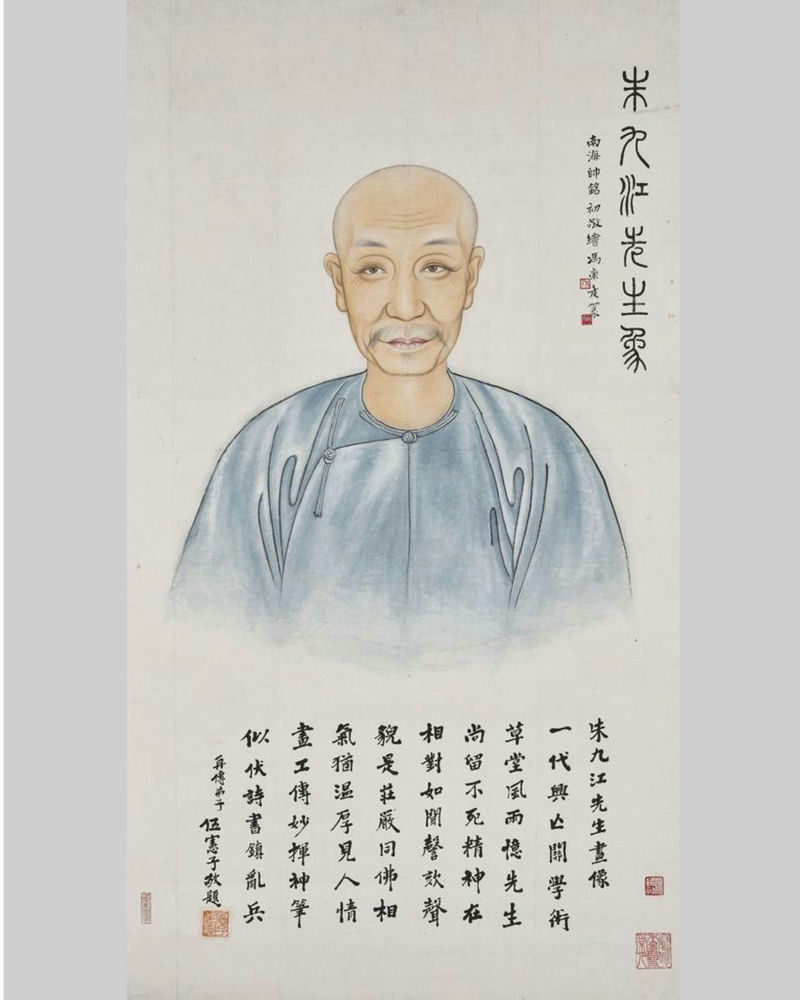

Liang Ch’i-chao asked his close friend the chü-jen (provincial graduate) T’ang En-p’u (唐恩溥 1881-1961), hao Tien-ju, to be his ghostwriter. Admittedly they were both natives of Hsin-hui of Kwangtung Province, moreover their scholarships were derived from the lineage of Chu Tz’u-ch’i (朱次琦 1807-1881), tzu Tz’u-hsiang, hao Chih-kuei, Chiu-chiang, native of Nan-hai, Kwangtung Province. Chu attained the chin-shih degree (metropolitan graduate) in the 27th year of the Tao-kuang reign (1847). He was magistrate of Hsiang-ling in Shansi Province for one hundred and ninety days. During this time he greatly altered the customs of the county. Afterwards he led a quiet life in Chiu-chiang of Fo-shan in Kwangtung Province. He taught at the school of Li-shan Ts’ao-ta’ng (禮山草堂) for thirty years.

Portrait of Chu Tz’u-ch’i

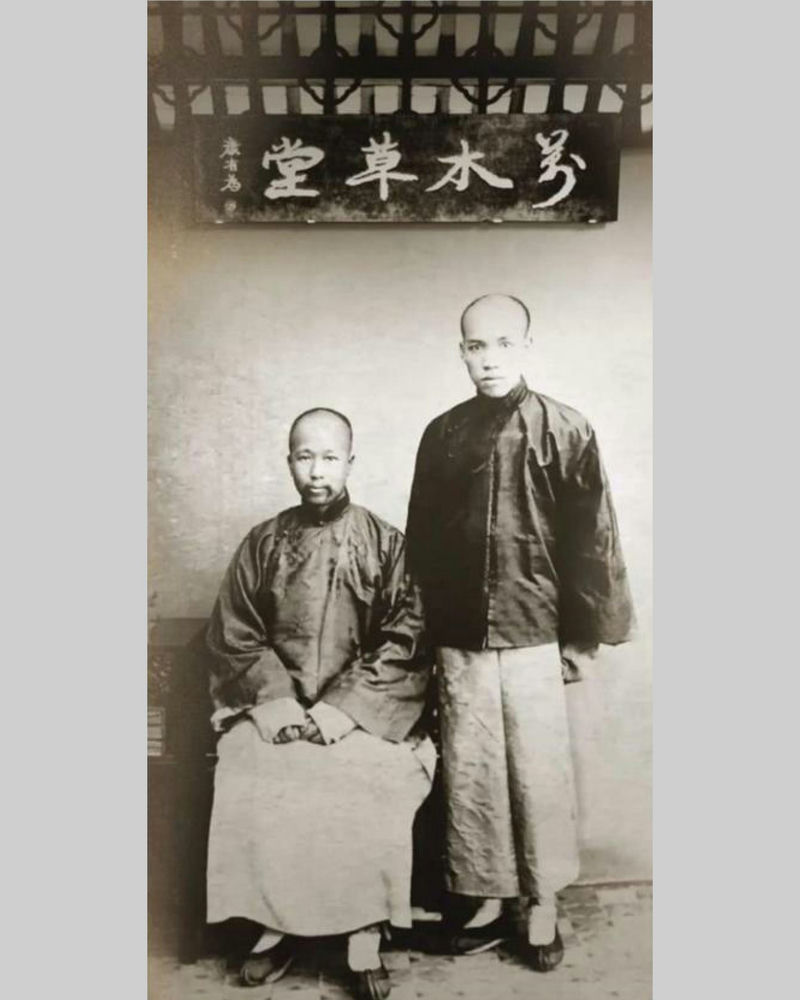

Portrait of K’ang Yu-wei and Liang Ch’i-chao

Liang Ch’i-chao studied under K’ang Yu-wei (康有為 1858-1927), hao Nan-hai, a distinguished student of Chu Tz’u-ch’i. K’ang Yu-wei once wrote an introduction for the collected works of his teacher, a part of it reads:

“For principle he (Master Chu) respectfully practiced his beliefs, for ideal he held no material desire. His moral rectitude towered to the blue sky, his learning explored extreme depths. He relinquished the scholarship of Han dynasty, he forswore the scholarship of Sung dynasty, in order to reinstall the original teachings of Confucius. The purpose was to seek practical applications to save the people. The person who possessed ancient scholarship in our time, was my teacher Master Chu Chiu-chiang………

His teachings consisted of The Four Implementations and The Five Learnings.

The First Implementation is Excercise Filial Piety with Sincerity. The Second Implementation is Venerate Moral Rectitude. The Third Implementation is Refine Individual Disposition. The Fourth Implementation is Scrutinize and Sustain Individual Dignity.

The First Learning is The Classics. The Second Learning is History. The Third Learning is Anecdotes. The Fourth Learning is Argumentation. The Fifth Learning is Literature.

Every day whenever Master Chu entered the classroom to teach, all the students waited there respectfully with solemn manners. Master Chu was erudite with exceptional memory. He did not carry any book, yet he quoted from many works. He recited and crisscrossed the contents without missing a single word. When students transcripted these teachings, it became a book. The book Li-shan chiang-i (The Lectures Given at Li-shan 禮山講義) came into being in this manner. Yet it is only a fraction of his teachings! As for teaching the issues of Righteousness, the concerns of Moral Rectitude, his spirit would be intense, his cheeks reddened, his voice boomed and shook the walls, the listeners fearful. Although my ability is pitiful, when I first heard his elementary transmission of the Great Way, I decided it was possible to emulate the Sage. I then abandoned all vulgar learnings. It was my beginning!”

This passage is ample illustration of K’ang Yu-wei’s heartfelt reverence towards his teacher. In the Draft History of Ch’ing, Chu Tz’u-ch’i is so described: “At that time, everyone regarded him as the model teacher of humanity.” The vitality of Confucianism in Kwangtung Province at the end of Ch’ing dynasty still instills people of today with ceaseless nostalgia.

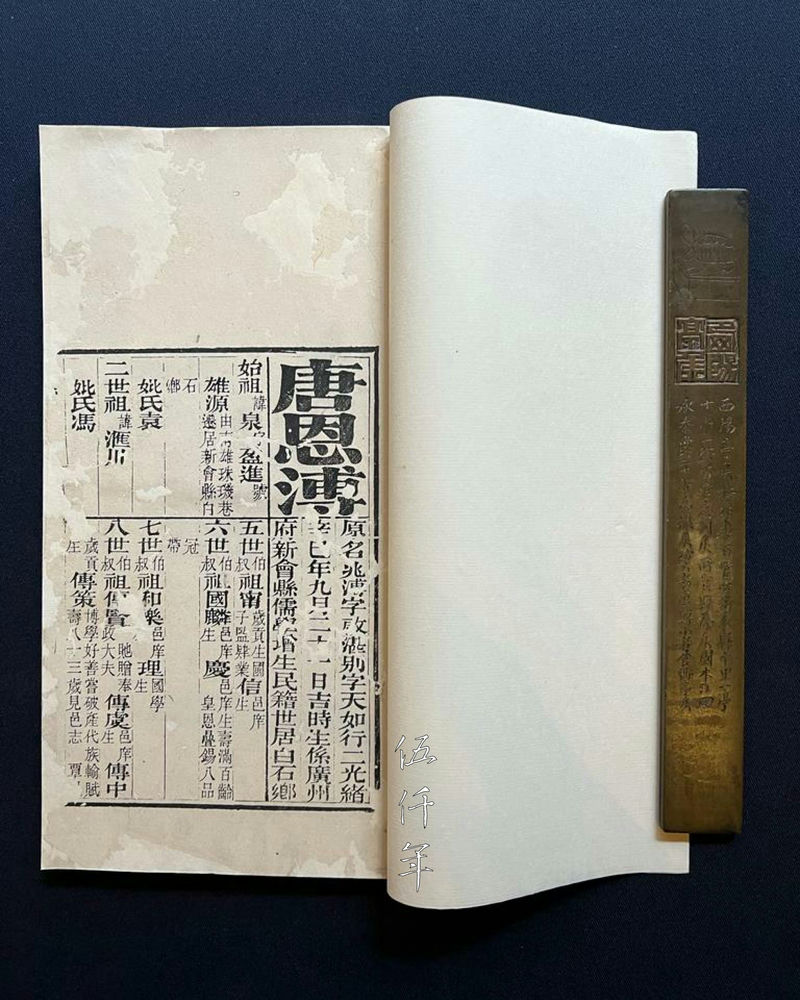

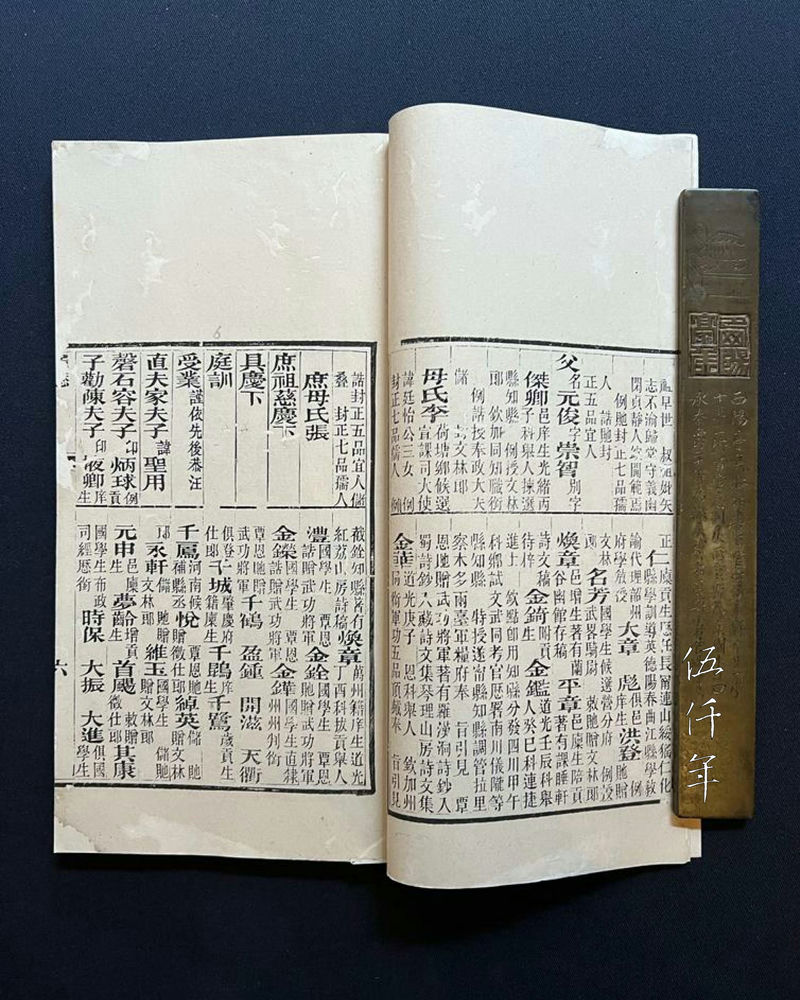

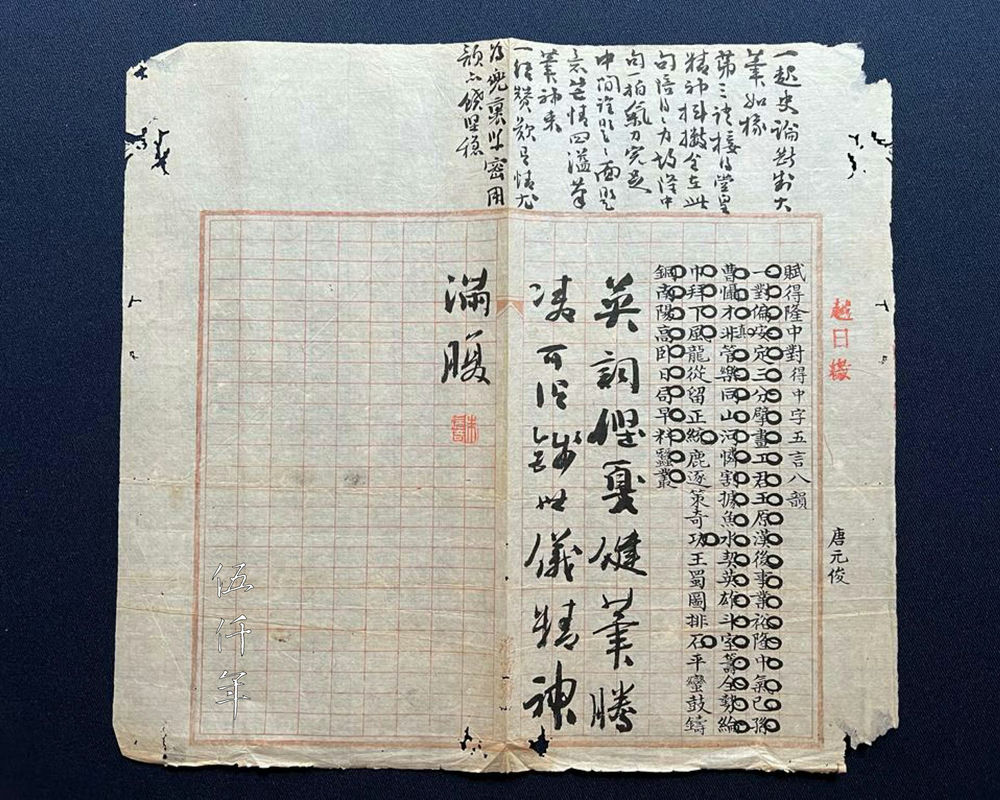

Imperial Examination Papers by T’ang En-p’u, containing information on his lineage including his father T’ang Yüan-chün

Imperial Examination Papers by T’ang En-p’u, containing information on his lineage including his father T’ang Yüan-chün

The father of T’ang En-p’u, T’ang Yüan-ch’ün (唐元俊), tzu Ch’ung-chih, attained his chü-jen degree in the 2nd year of the Kwang-hsü reign (1876). He was a student of Chu Tz’u-ch’i. In the house of the T’ang family, there were more than ten manuscripts written by T’ang Yüan-ch’ün in the classroom, all with commentaries handwritten by Chu Tz’u-ch’i, as well as impressions of a small seal with the characters “Chu Tz’u-ch’i”.

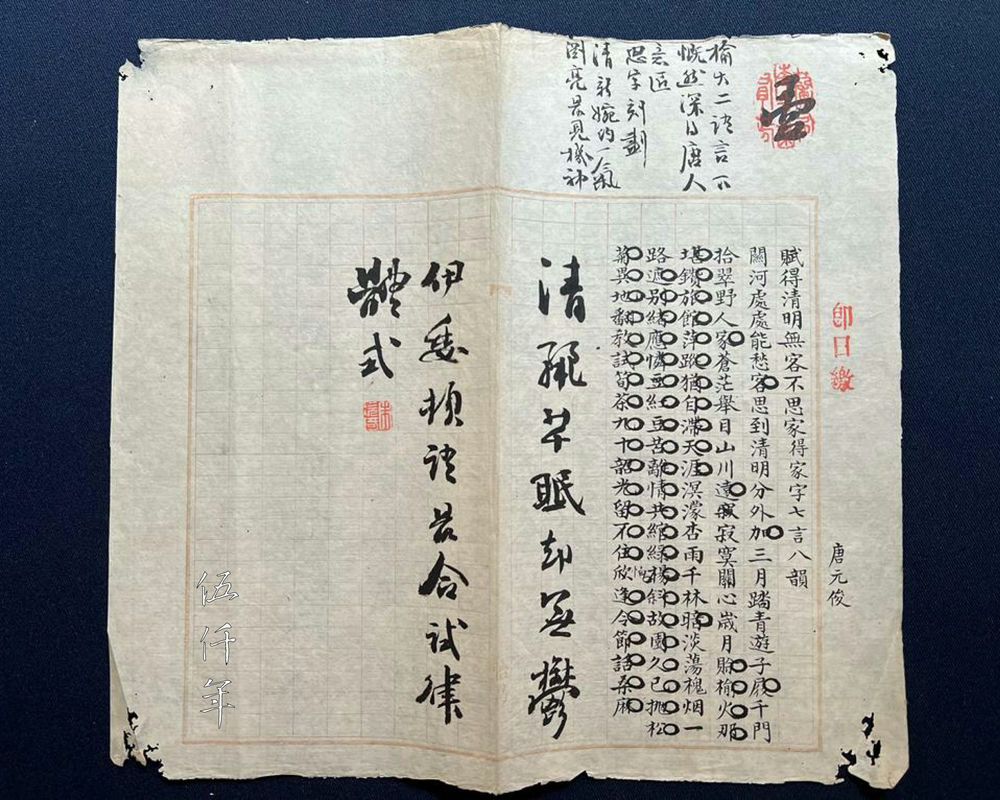

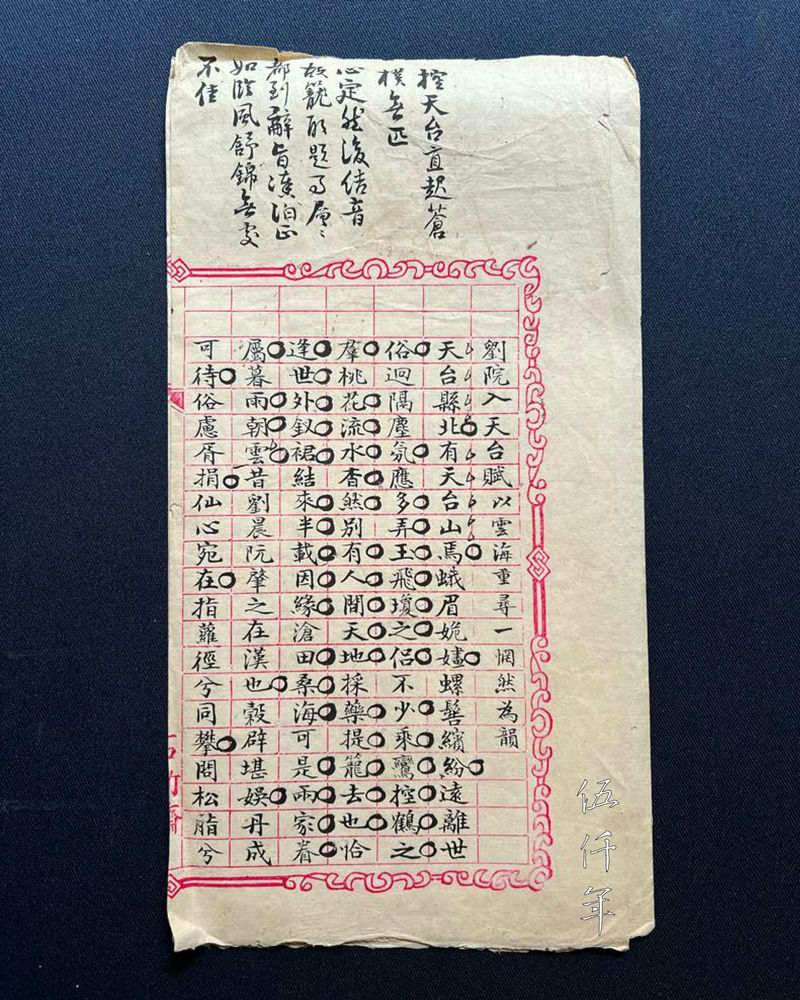

First classwork by T’ang Yüan-chün, with inscriptions on upper page and side page by Chu Tz’u-ch’i

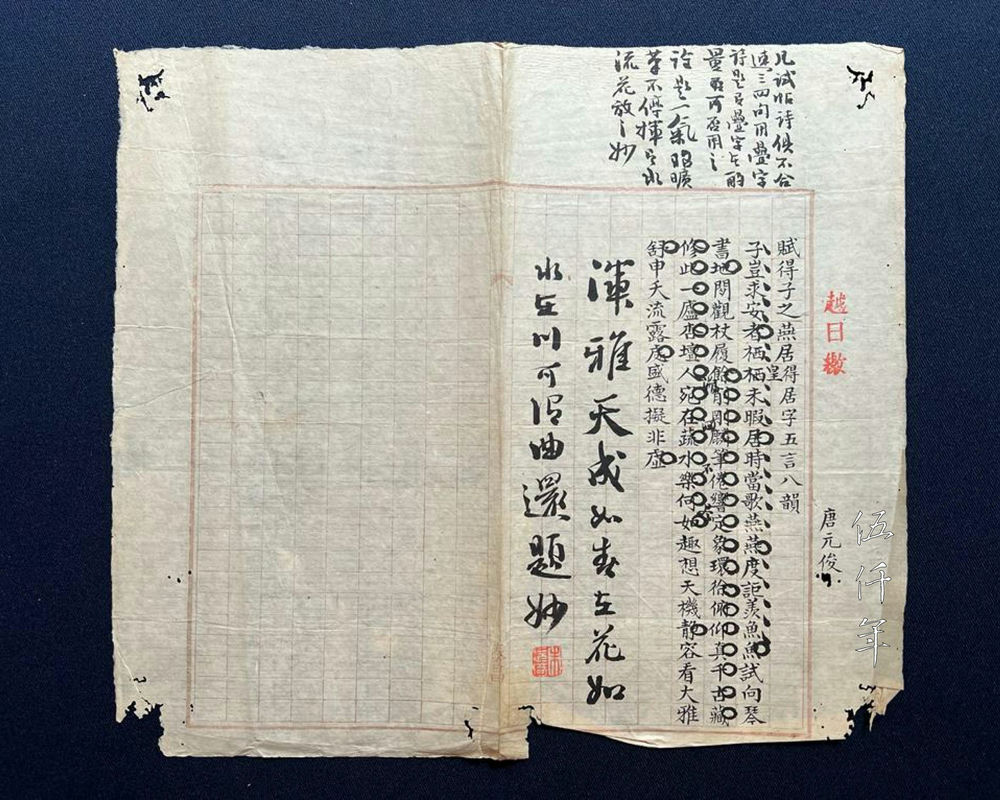

Second classwork by T’ang Yüan-chün, with inscriptions on upper page and side page by Chu Tz’u-ch’i

Third classwork by T’ang Yüan-chün, with inscriptions on upper page and side page by Chu Tz’u-ch’i

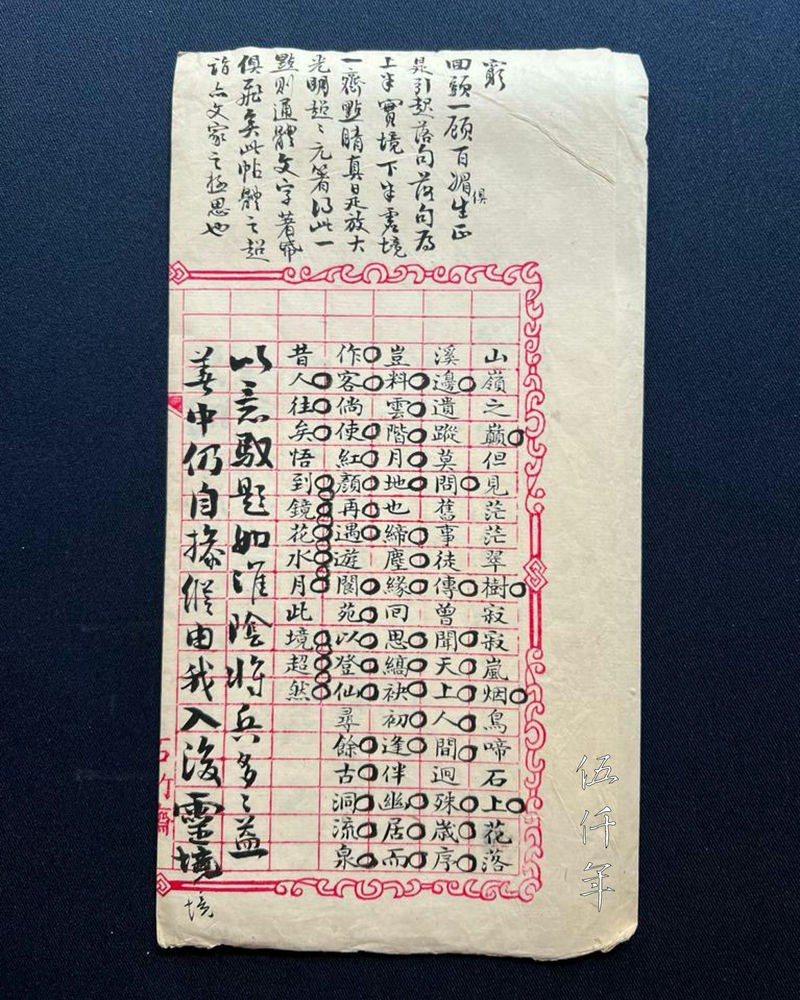

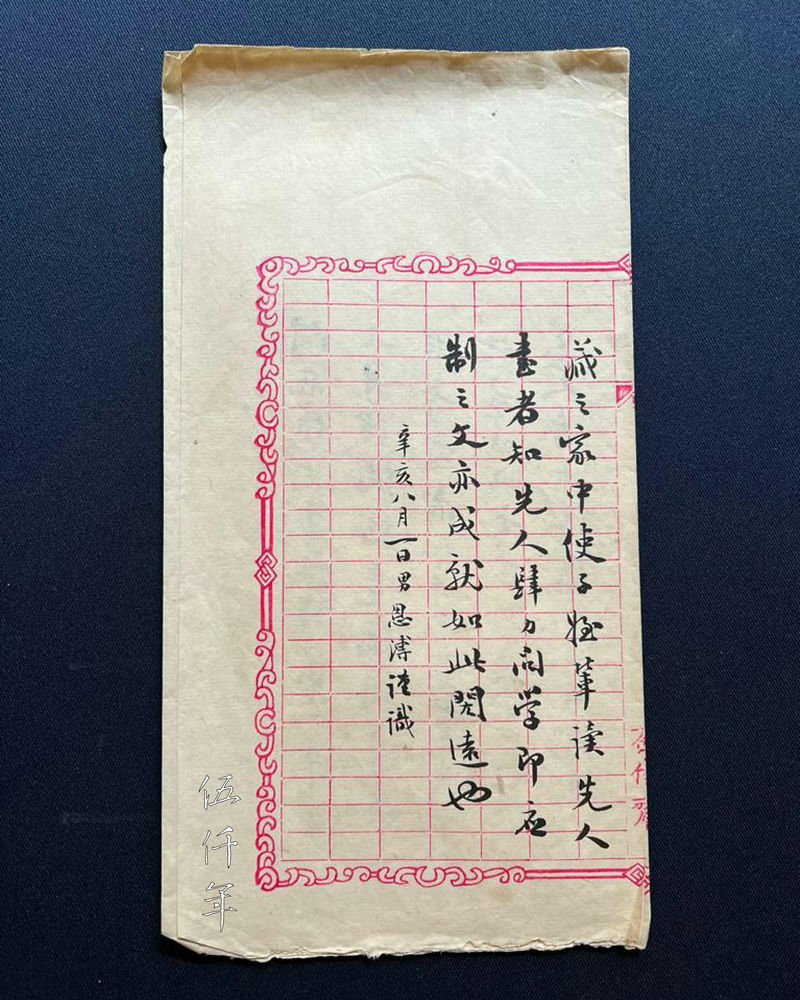

In hsin-hai year (1911), T’ang En-p’u gifted one of his father’s manuscripts with commentary by Chu Tz’u-ch’i to his fellow chü-jen examination candidate Huang Hsiao-chüeh (黃孝覺). He made a copy to keep and inscribed these words on it:

“This piece of writing was composed by my father when he was a student of Master Chu Tz’u-ch’i. It was selected by Master Chu as the best in his class. In July of hsin-hai year, as I was chronicling the writings of my late father, my fellow chü-jen examination candidate Huang Hsiao-chüeh was fervently seeking the ink works of Master Chu. So I gave him the original manuscript. I copied this piece of writing by my ancestor, and respectfully stashed it in the house for my sons and nephews to read. They will know that our ancestor exerted himself in learning, even a piece of writing intended for the imperial examination could realize such grand and lofty accomplishment.

Attentively chronicled by son En-p’u on 1 August in hsin-hai year.”

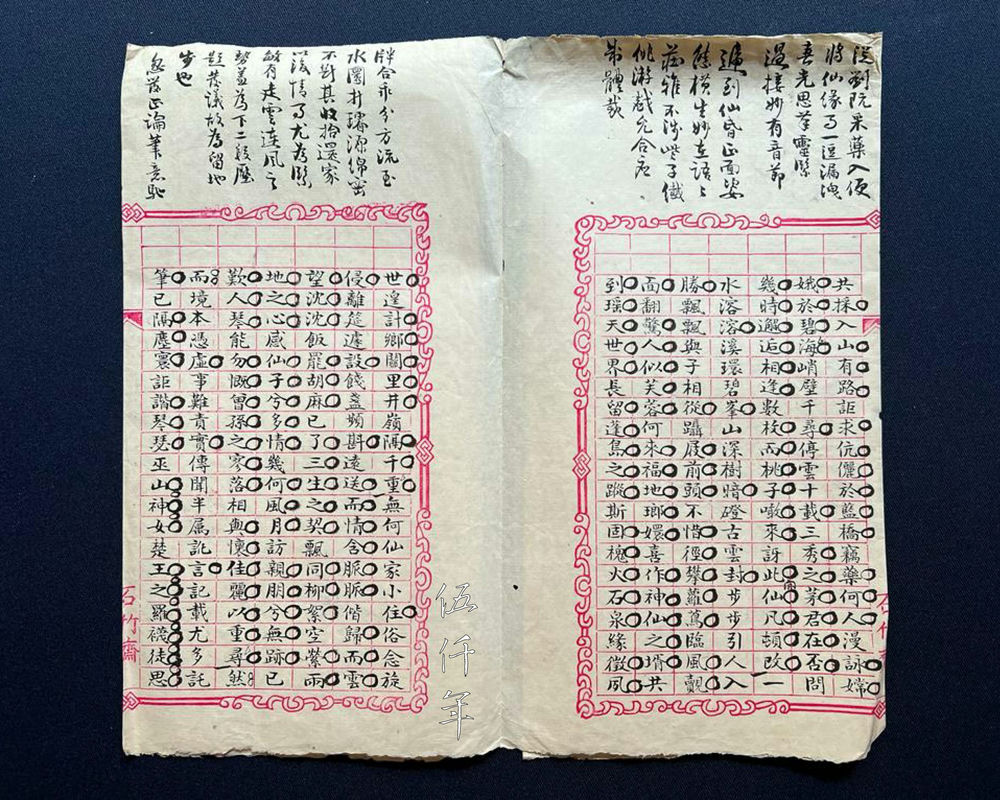

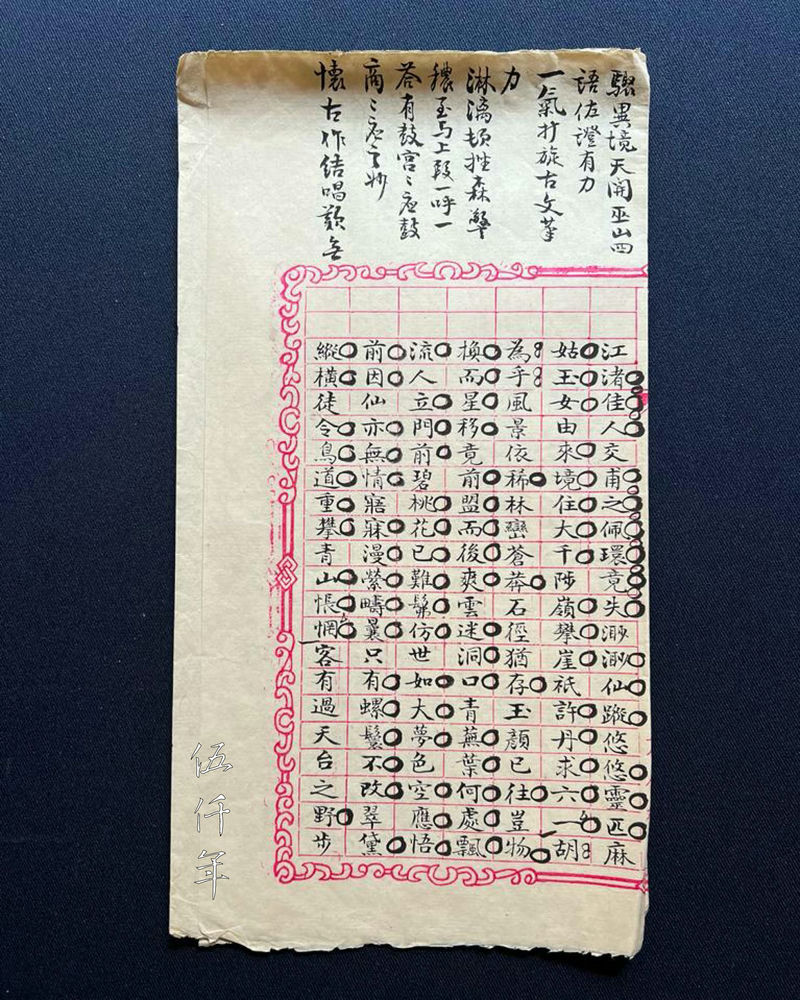

T’ang En-p’u made a copy of his father’s classwork and inscribed it, the original was gifted to Huang Hsiang-chüeh

T’ang En-p’u made a copy of his father’s classwork and inscribed it, the original was gifted to Huang Hsiang-chüeh

T’ang En-p’u made a copy of his father’s classwork and inscribed it, the original was gifted to Huang Hsiang-chüeh

T’ang En-p’u made a copy of his father’s classwork and inscribed it, the original was gifted to Huang Hsiang-chüeh

T’ang En-p’u made a copy of his father’s classwork and inscribed it, the original was gifted to Huang Hsiang-chüeh

T’ang En-p’u made a copy of his father’s classwork and inscribed it, the original was gifted to Huang Hsiang-chüeh

In his early years, T’ang En-p’u also studied under Lo Hsi-lin (羅樨林), another student of Chu Tz’u-ch’i. Liang Ch’i-chao attained the chü-jen degree in the 15th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1889). T’ang En-p’u attained the chü-jen degree in the 29th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1903). They were both successive provincial graduates with distinguished reputations who came from Hsin-hui. One may surmise that their friendship originated from Hsin-hui.

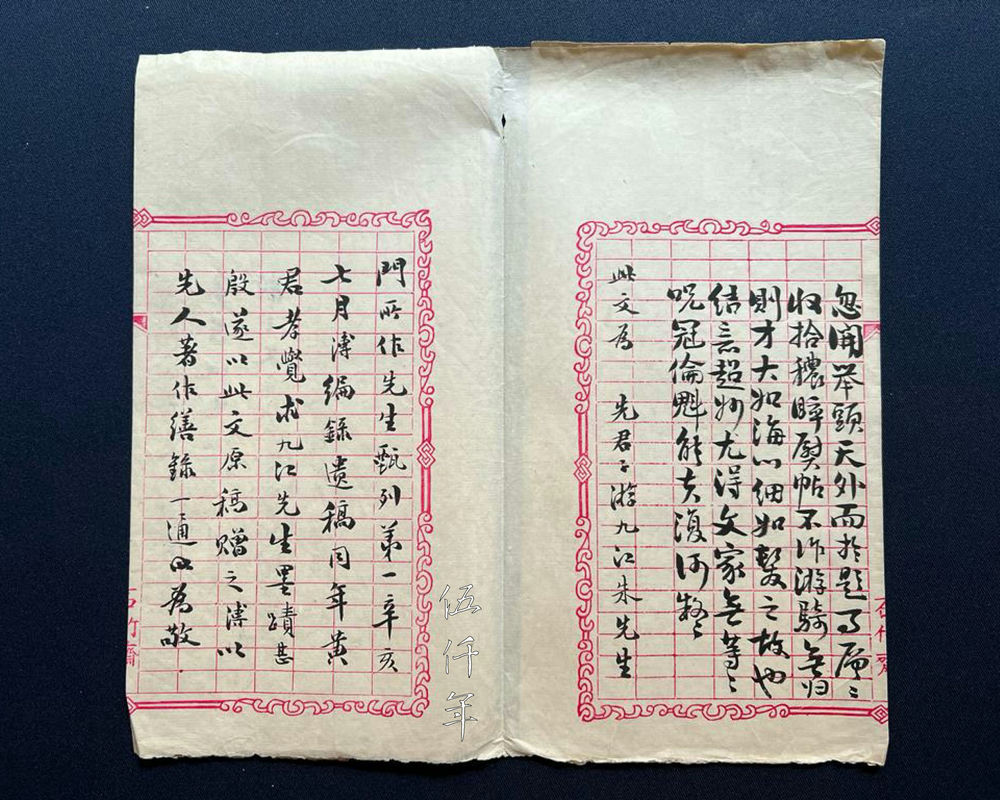

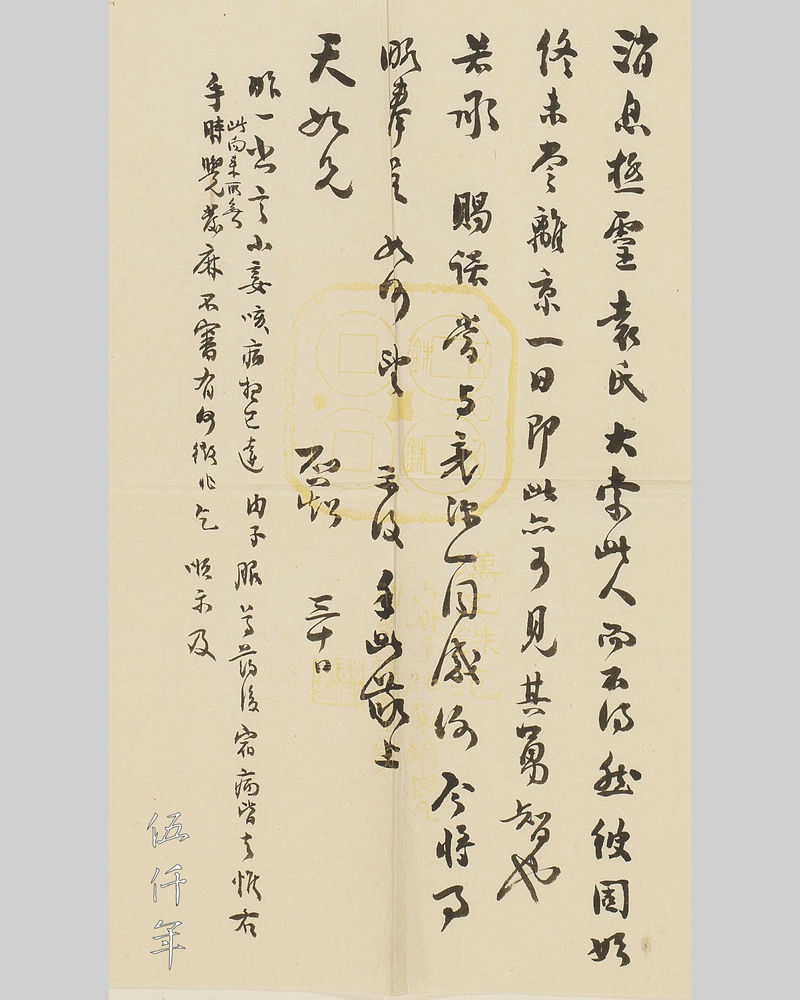

First page of letter by Liang Ch’i-chao to T’ang En-p’u

Second page of letter by Liang Ch’i-chao to T’ang En-p’u

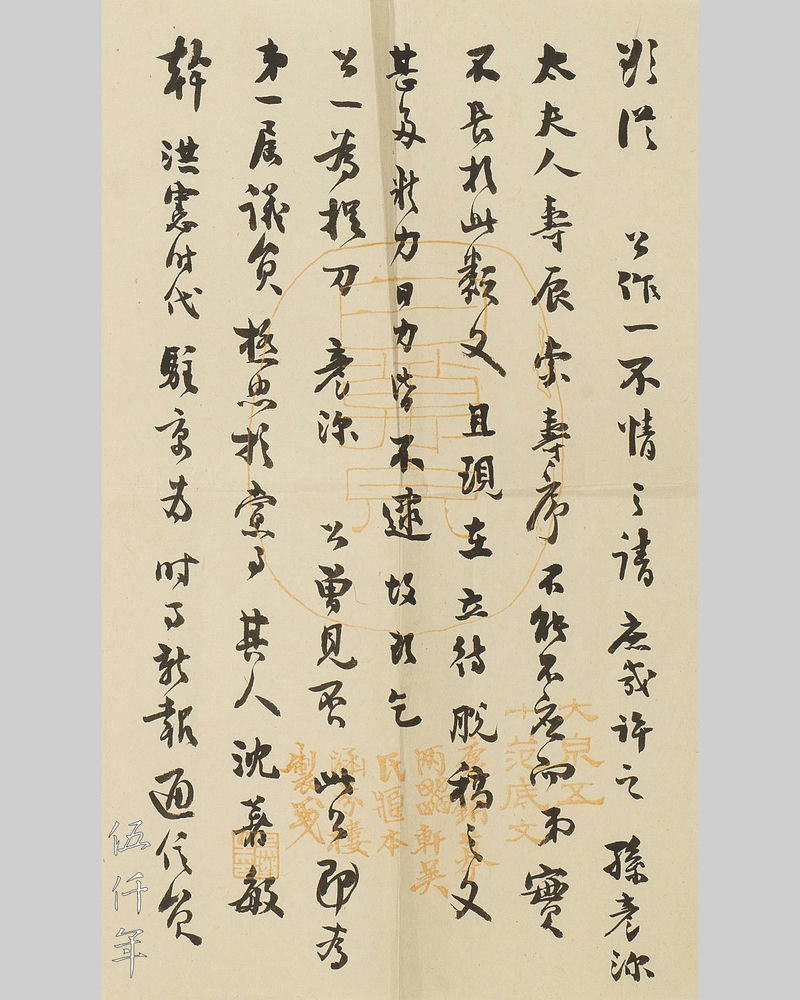

Around the 7th year of the Republic (1918), Liang Ch’i-chao wrote a letter from Tientsin to T’ang En-p’u in Peking. It reads:

“Sir, I wish to ask a preposterous favour from you. Perhaps you are willing to grant it. It is the mother’s birthday of Sun Yen-shen (孫彥深), and he asked for a birthday essay. I cannot but oblige. Yet I am really not adept at this kind of writing. Furthermore, there are already many articles I need to deliver promptly. My vigour and eyesight are inadequate for this. Therefore I beg you to ghostwrite instead. Did you ever meet Yen-shen? He is the one of the first representatives elected to the National Assembly, and is very loyal to the affairs of the Party. He is composed, alert and competent. During the reign of Hung-hsien (1916), he was a journalist from Shih-shih Hsin-pao Newspaper (時事新報) stationed in Peking and was exceedingly well informed. Yüan Shih-k’ai (袁世凱 1859-1916) searched everywhere for him but could not find him, yet he did not once leave Peking even for a day throughout this time. From this it is possible to picture his courage and wisdom. If you are kind enough to agree, I thank you together with Yen-shen. What about presenting you with his concise biography? I look forward to your reply. Drafted by hand. Respectfully presented to elder brother En-p’u.

Ch’i-chao. 30th.

Yesterday I sent you a letter about the coughing of my second wife. I presume it has arrived. After taking your medicine, my wife’s old illness is gone. But her right hand regularly feels numb (this has never occurred before). I do not know whether these are signs of ailment. I implore you to let me know as well.”

This letter is proof that Liang Ch’i-chao asked T’ang En-p’u to ghostwrite. Liang did not refrain from talking about this with his friends either. He wrote in the letter: “If you are kind enough to agree, I thank you together with Yen-shen.” It was clear that Sun Yen-shen was fully aware that Liang Ch’i-chao had asked his friend T’ang En-p’u to ghostwrite the birthday essay.

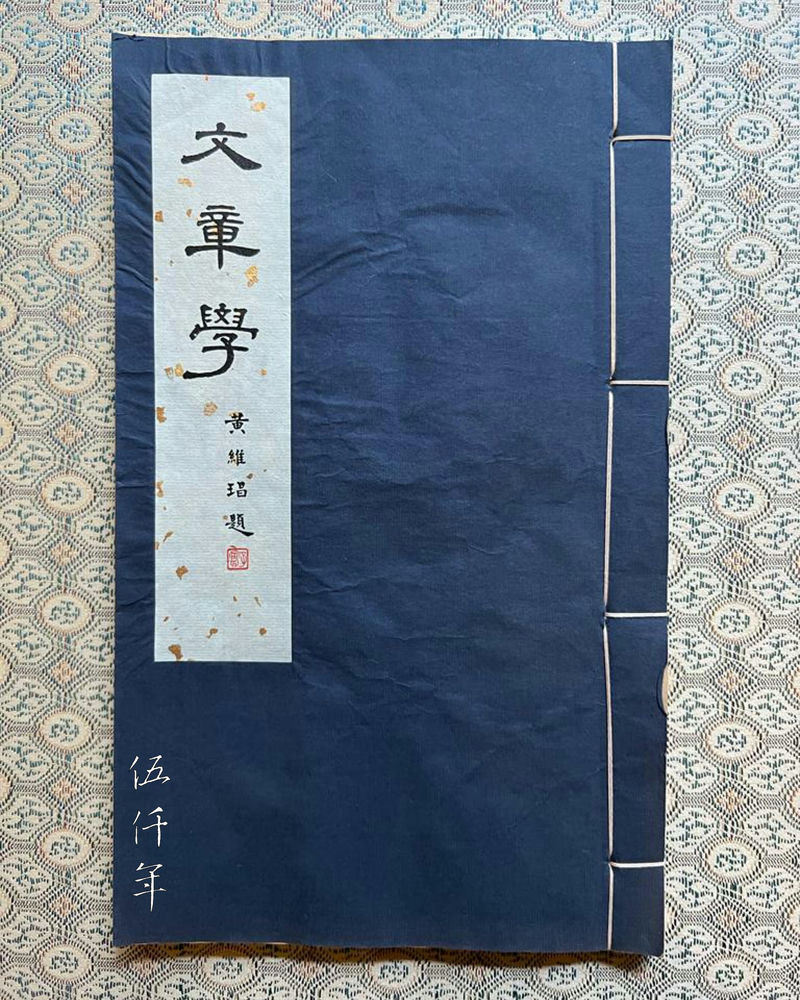

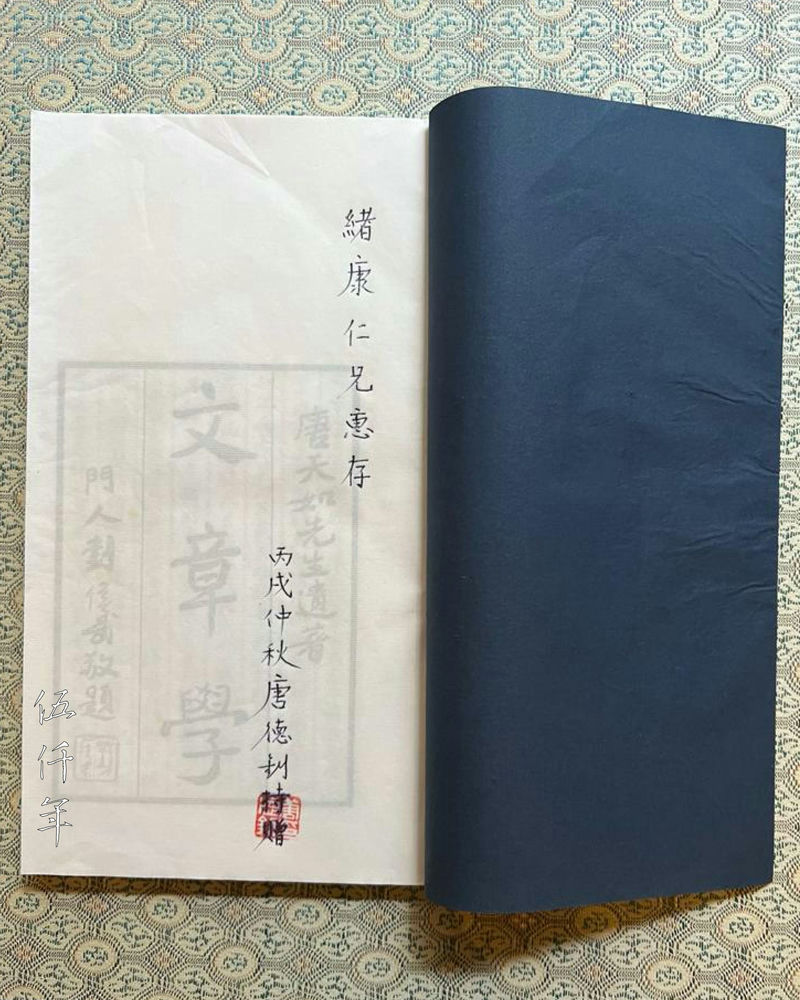

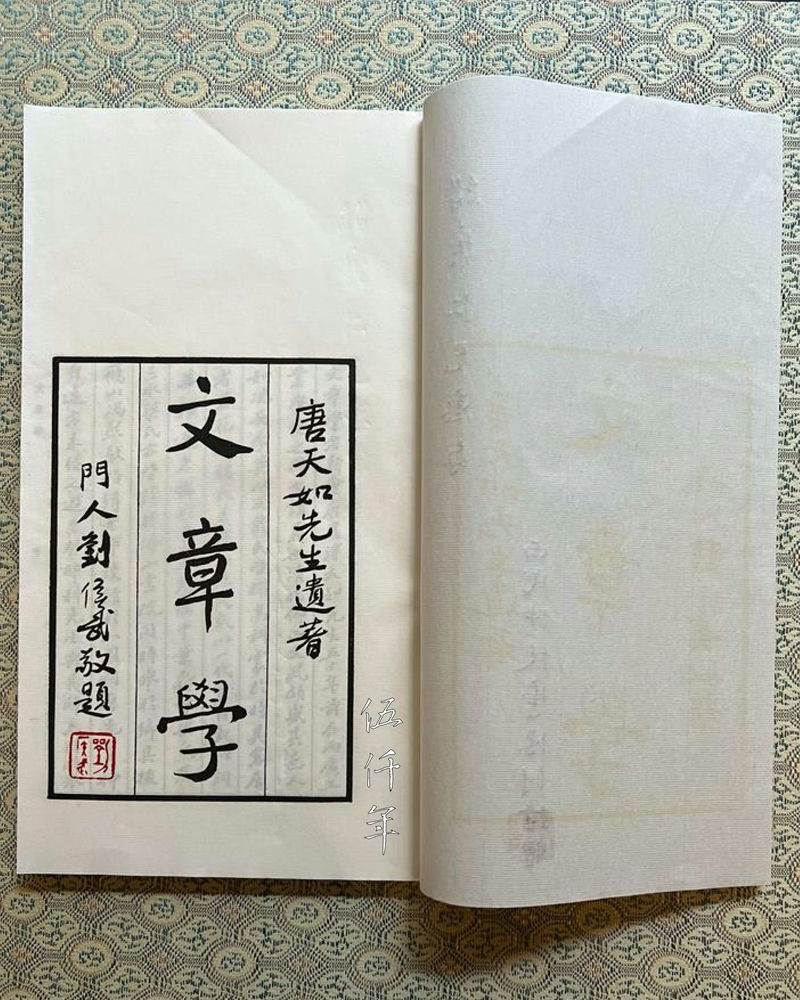

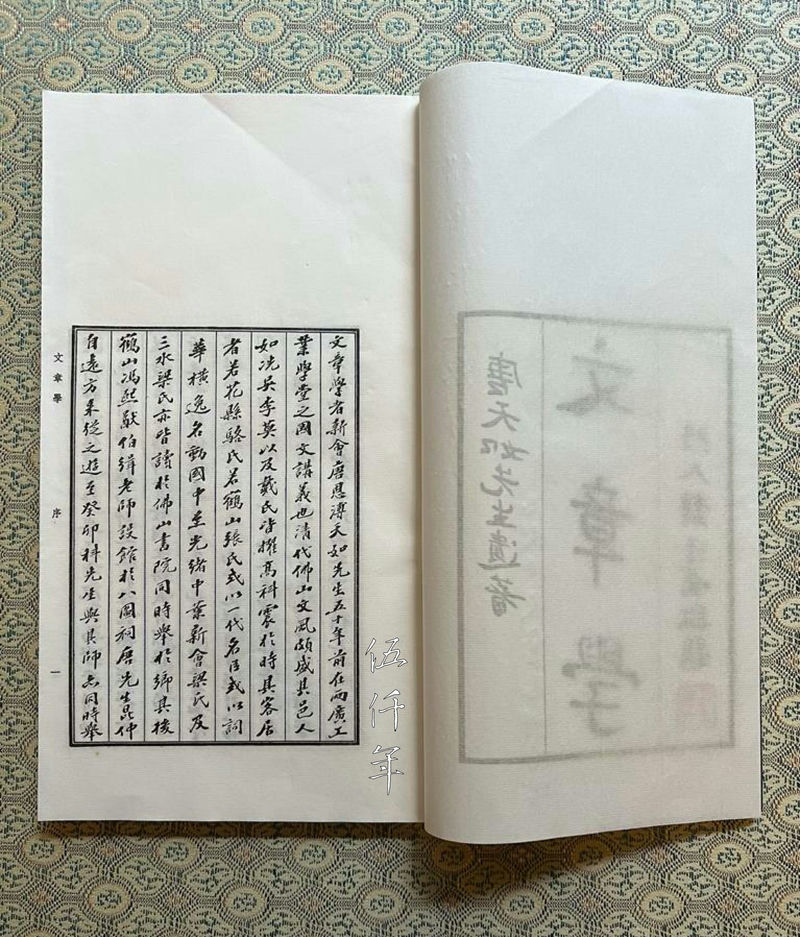

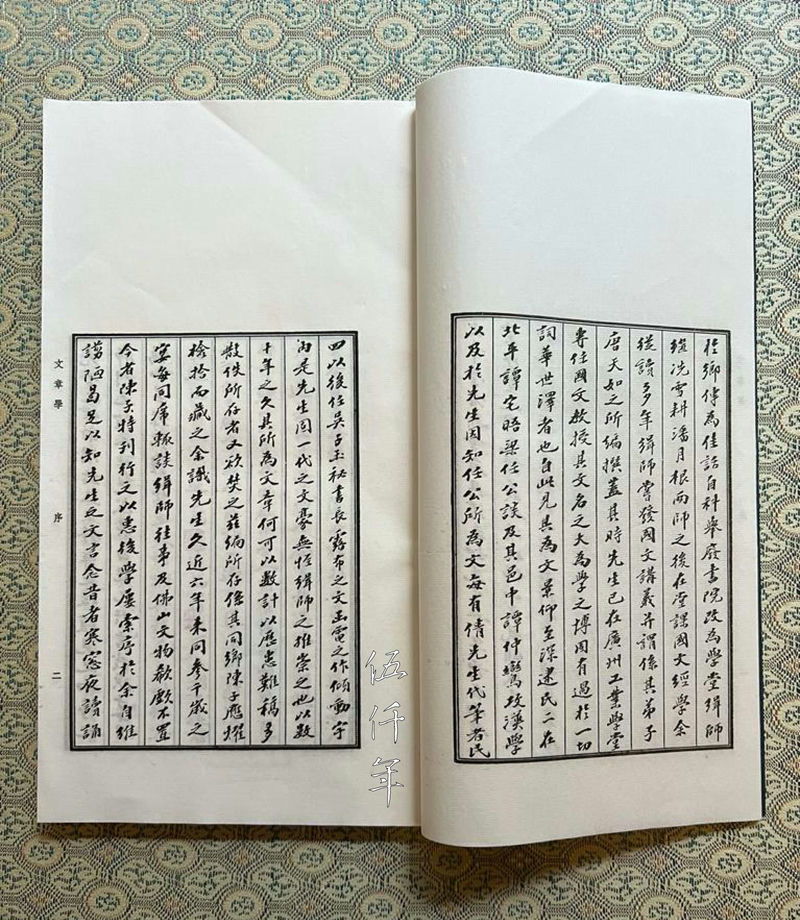

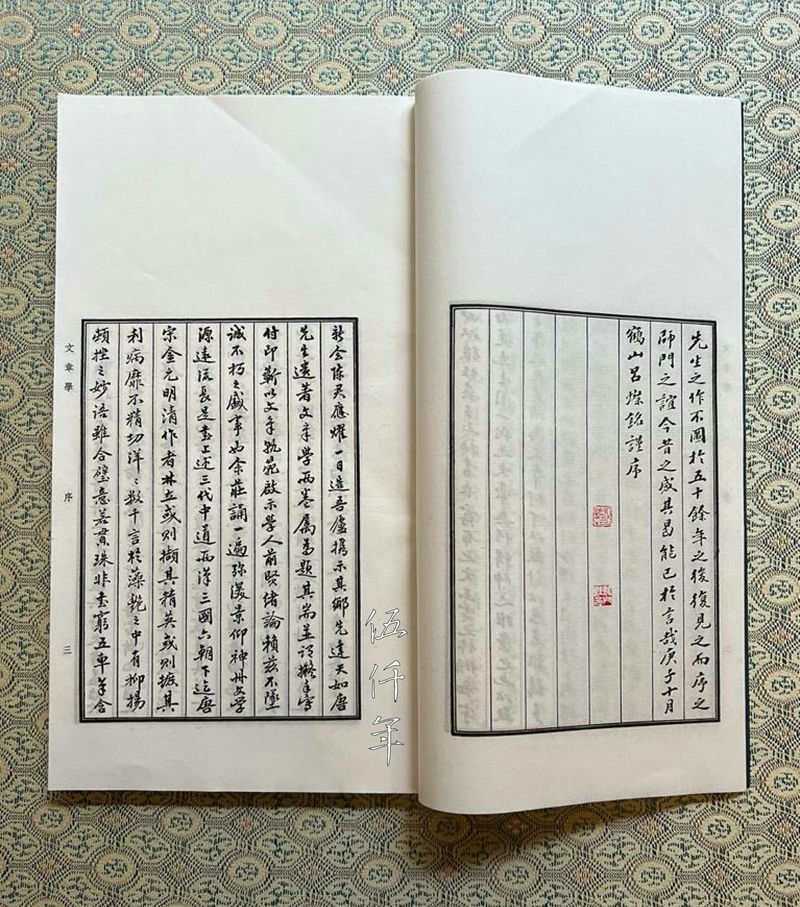

Front cover of Wen-chang hsüeh (Studies of Writing 文章學) by T’ang En-p’u

Inside page of Wen-chang hsüeh with inscription by T’ang Te-chao, son of T’ang En-p’u

Title page of Wen-chang hsüeh by T’ang En-p’u

Introduction by Lü Ts’ai-ming for Wen-chang hsüeh

Introduction by Lü Ts’ai-ming for Wen-chang hsüeh

Introduction by Lü Ts’ai-ming for Wen-chang hsüeh

Lü Ts’ai-ming (呂燦銘) from Fo-shan, Kwangtung Province, wrote an introduction to the book Wen-chang hsüeh (Studies of Writing 文章學) by T’ang En-p’u. He also recounted the story of Liang Ch’i-chao and his ghostwriter. He wrote in the Introduction:

“In the 2nd year of the Republic (1913), I met Liang Ch’i-chao in Peking at the house of T’an. We talked about T’an Chung-luan (譚仲鸞) who specialized in Han studies in his native city, as well as Mr. T’ang En-p’u. Hence I realized that the writings of Liang Ch’i-chao were often ghostwritten by Mr. T’ang. After the 4th year of the Republic (1915), Mr. T’ang became the secretary general of Wu P’ei-fu (吳佩孚). Those official announcements, letters and telegrams he wrote affected and aroused the country. Mr. T’ang was a literary giant of his generation. No wonder he was highly praised by my teacher Master Chi (緝師).”

According to the Introduction, quite a bit of writings by Liang Ch’i-chao was ghostwritten by T’ang En-p’u. Master Chi mentioned in the letter was Feng Hsi-yu (馮熙猷), tzu Po-chi, native of Fo-shan. He set up a school at Ho-shan and T’ang En-p’u was a student of his. Both Feng and T’ang attained the chü-jen degree in the same year, which was the 29th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1903). It was a much celebrated story at the time.

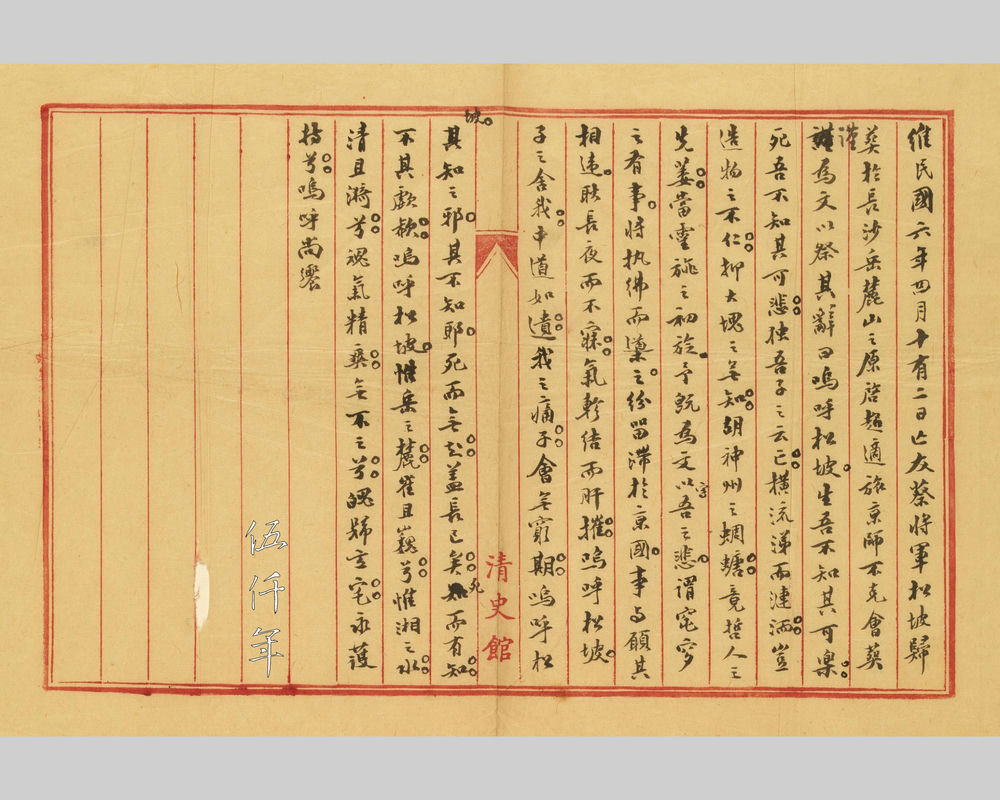

Eulogium of Ts’ai Sung-p’o at the State Funeral, ghostwritten by T’ang En-p’u for Liang Ch’i-chao

Amongst the manuscripts left behind by T’ang En-p’u, there appeared Eulogium of General Ts’ai Sung-p’o (蔡松坡) at the State Funeral, a piece ghostwritten by him at the request of Liang Ch’i-chao. It reads:

“On 12 April in the 6th year of the Republic (1917), my late friend General Ts’ai Sung-p’o returned for burial in the open field of Yüeh-lu Mountain of Ch’ang-sha. I, Ch’i-chao, happens to be travelling in Peking and am unable to attend the burial ceremony. I attentively composed the Eulogium. The words are:

Alas! Sung-p’o!

I know not there can be joy in life,

I know not there can be woe in death.

Only when I heard your passing my friend,

Tears flowed all over without restraint.

Can it be that the Creator is heartless?

Can it be that the Cosmos is absurd?

Our Divine Land has been simmering,

Without notice the virtuous withered early.

As the spirit banners flutter in procession

Bear my sorrow on a piece of writing.

I was told of the ceremony at the grave,

To head the path pulling the casket rope.

Hindered by my stay in the capital of old,

Actuality and want are both at odds.

Through the long nights waken to brood,

Painful breathe and wounded liver.

Alas! Sung-p’o!

Are you in the know?

Or are you otherwise?

The dead never rises,

It is eternally so.

For the dead to know,

Then try to sob no more.

Alas! Sung-p’o!

Only the mountain of Lu,

Lofty and grand.

Only the river of Hsiang,

Clear and calm.

Vital energy of the Soul

Here and there.

Homeward Spirit to the tomb

Safe and ever.

Alas!

I proffer these offerings for your enjoyment.”

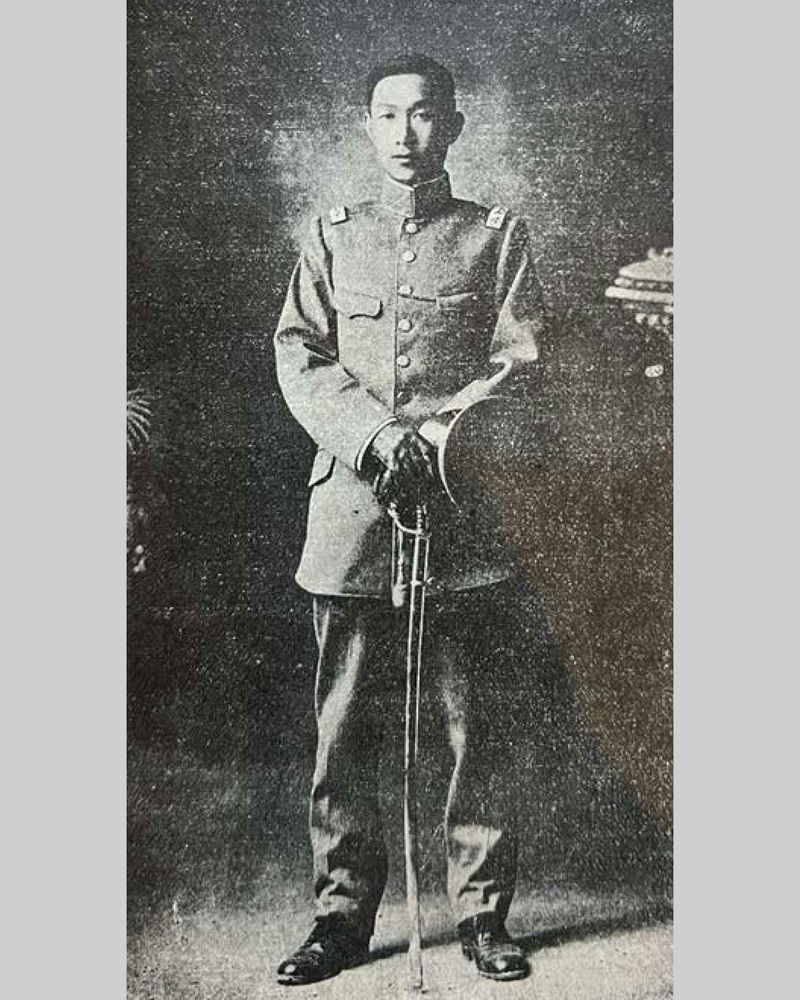

Portrait of Ts’ai Sung-p’o

Ts’ai Sung-p’o (1882-1916), original name Ken-yin, tzu Sung-p’o, his name later changed to O, native of Pao-ch’ing, Hunan Province. In the 23rd year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1897), at the age of sixteen, he entered Shih-wu Hsüeh-t’ang School (時務學堂) which was founded in the same year in Ch’ang-sha of Hunan Province. Liang Ch’i-chao was appointed head teacher of Chinese at the School. He thought highly of Ts’ai Sung-p’o, the friendship between teacher and student started there. In the following year, Empress Dowager Tz’u-hsi (慈禧) organized a coup d’etat, she executed the Six Gentlemen of the Hundred Days’ Reform and brought an end to the Reform. Liang Ch’i-Chao went into exile in Japan, Shih-wu Hsüeh-t’ang School was also banned. In the 25th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1899), Liang Ch’i-Chao assisted Ts’ai Sung-p’o to travel to Japan, and enrolled in the Ta-t’ung High School in Tokyo. In the following year, Ts’ai Sung-p’o returned to China and joined the Tzu-li Army Rebellion organized by T’ang Ts’ai-ch’ang (唐才常 1867-1900). The Rebellion failed, he returned to Japan and changed his name to Ts’ai O (蔡鍔). The meaning of the character O (鍔) is “tip of a sword”. He was ever more determined to assist the cause of revolution.

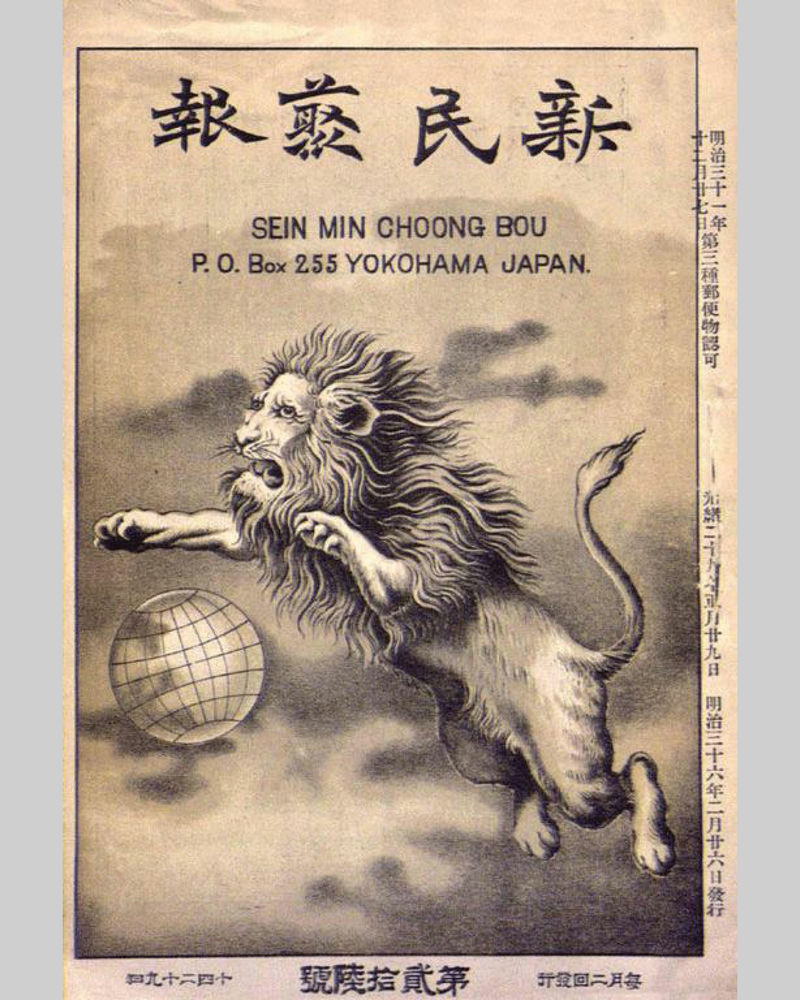

Hsin-min ts’ung-pao Newspaper, issued on 29 January in the 29th year of the Kuang-hsü reign

In the 28th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1902), Liang Chi-ch’ao launched the Hsin-min ts’ung-pao Newspaper (新民叢報) in Yokohama. Ts’ai Sung-p’o was appointed editor. The year after, he graduated from the Imperial Japanese Army Academy. In the 30th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1904), he returned to China. The year after, he was appointed chief training officer of the Kwangtung New Reserve Army, as well as chief staff officer of the Governor’s Office. In the 33rd year of the Kwang-hsü reign (1907), he was appointed administrator of Kwangsi Army Primary School. The later Pai Ch’ung-hsi (白崇禧 1893-1966), Li P’in-hsien (李品仙 1890-1987) and others were all alumni. In the following year, he was appointed commander of the 1st Piao (Command 標) of the New Reserve Army, and was stationed in Nan-ning, Kwangsi Province. In the 1st year of the Hsüan-t’ung reign (1909), he was appointed superintendent of Kwangsi Chiang-wu T’ang (講武堂). The year after, he was appointed battalion commander of Kwangsi Mixed Hsieh (協), and ordered to be stationed in Yunnan Province. In the 3rd year of the Hsüan-t’ung reign (1911), he was appointed assistant commander of the 37th Hsieh stationed in K’un-ming. In late Ch’ing, there were approximately sixteen chen (鎮) in the New Army, each chen consisted of two hsieh (協), each chün (軍) consisted of two chen. Each hsieh was composed of over four thousand officers and soldiers. In the same year, Ts’ai Sung-p’o compiled Quotes by Tseng and Hu on Military Affairs (曾胡治兵語錄). Tseng is Tseng Kuo-fan (曾國藩 1811-1872) and Hu is Hu Lin-i (胡林翼 1812-1861).

On 10 October in the same year, news of the Wu-ch’ang Uprising arrived. Ts’ai Sung-p’o plotted to reciprocate. Li Ken-yüan (李根源 1879-1965) led the students from Chiang-wu T’ang to attack the north-west of K’un-ming City, Yunnan Province. Ts’ai Sung-p’o led the attack of the south-east, the city fell, and Yunnan declared independent. Ts’ai Sung-p’o was elected military governor of the Great Han Military Government of Yunnan Province.

When the Republic of China was founded in 1912 (known as the 1st year of the Republic), tremendous amount of work needed to be done. Ts’ai Sung-p’o focused on the administration of Yunnan Province. The year after, he was assigned to Peking. T’ang Chi-yao (唐繼堯 1883-1927) succeeded him as military governor of Yunnan Province. In the same year, Ts’ai Sung-p’o wrote Military Scheme, and formed the Military Studies Society with Yen Hsi-shan (閻錫山 1883-1960), Chiang Fang-chen (蔣方震 1882-1938) and nine others to unite like-minded people.

In the 3rd year of the Republic (1914), he was awarded the title Chao-wei General. In August the following year, Yüan Shih-k’ai formed the Ch’ou-an Society (籌安會), scheming to revive the political system of Imperial China. Liang Ch’i-chao published the article “How Bizarre is This Question of Political System” and became the first to publicly denounce the attempt to revive the Imperial political system. Ts’ai Sung-p’o then visited Liang Ch’i-chao in Tientsin to discuss possible actions. On 13 December, Yüan Shih-k’ai declared himself emperor. On 17 December, Ts’ai Sung-p’o left Peking under disguise and arrived in Tientsin, he bid farewell to Liang and used an alias to board a ship to Japan. There he boarded another ship to Hong Kong, and on 22 December he arrived in the capital city of Yunnan Province. He sent a telegram to Yüan Shih-k’ai and asked him to annul the Imperial system.

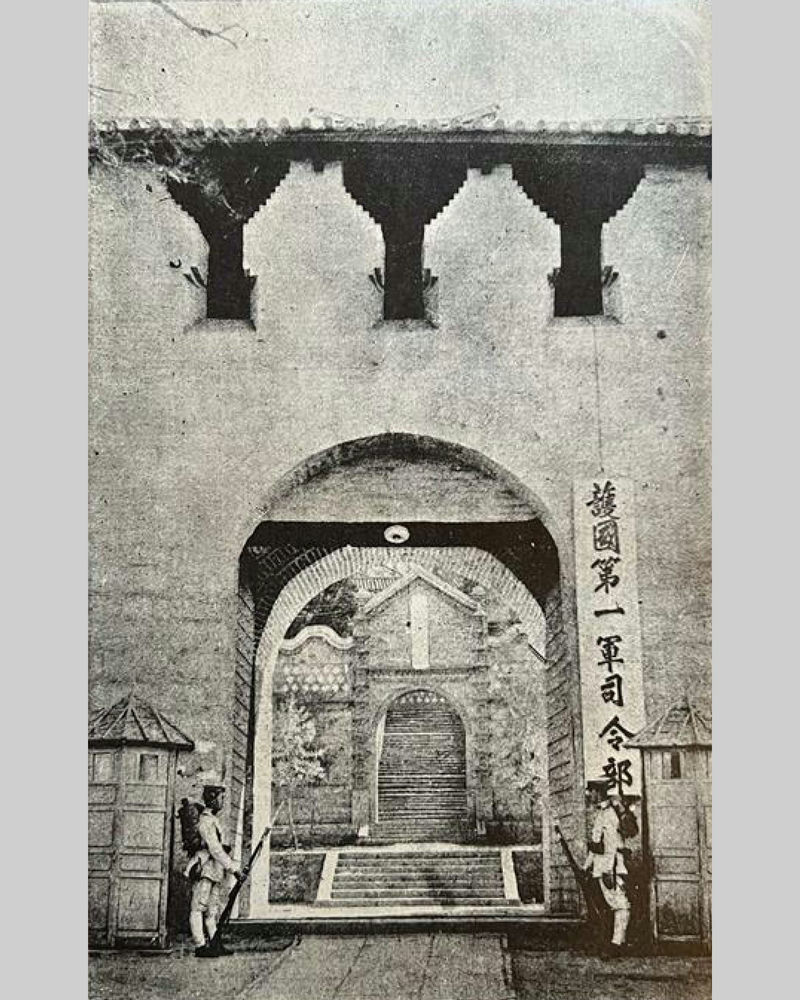

Headquarters of the 1st Army to Protect the Nation in Yunnan, Ts’ai Sung-p’o was the commander-in-chief

At the time, most of the supporters of Dr. Sun Yat-sen and the Kuomintang were in exile after the failure of The Second Revolution against Yüan in 1913, they were unable to do anything effective. On 25 December Yunnan declared independence. The next day, the Military Headquarters of the Army to Protect the Nation was formed, Ts’ai Sung-p’o became commander-in-chief of the 1st Army, Li Lieh-chün (李烈鈞 1882-1946) became commander-in-chief of the 2nd Army, and T’ang Chi-yao became commander-in-chief of the 3rd Army. They then attacked Szechwan Province. On 1 January in the 5th year of the Republic (1916), a proclamation of The Nineteen Misdeeds of Yüan Shih-k’ai was announced, and on 5 January telegrams were sent out across the country to form a crusade against Yüan and to safeguard the Republic of China. Liang Ch’i-chao was in Shanghai instigating the revolt of the south-west provinces.

On 15 March, Kwangsi Province declared independence. On 22 March Yüan called off the Imperial system and dropped the reign year of Hung-hsien. On 24 March, Yüan asked K’ang Yu-wei, Wu Ting-fang (伍廷芳 1842-1922) and T’ang Shao-i (唐紹儀 1862-1938) to help negotiate an end to the civil war. Ts’ai Sung-p’o advocated the resignation of Yüan Shih-k’ai. On 3 April, Kwangtung Province declared independence, on 11 April, Chekiang Province declared independence, on 26 April, Ling-ling District of Hunan Province declared independence. In May, Hei-lung-chiang, Shensi Province, Hunan Province declared independence. On 6 June, Yüan Shih-k’ai died of illness. The vice-president Li Yüan-hung (黎元洪 1864-1928) succeeded him. The campaign against Yüan Shih-k’ai finally came to an end.

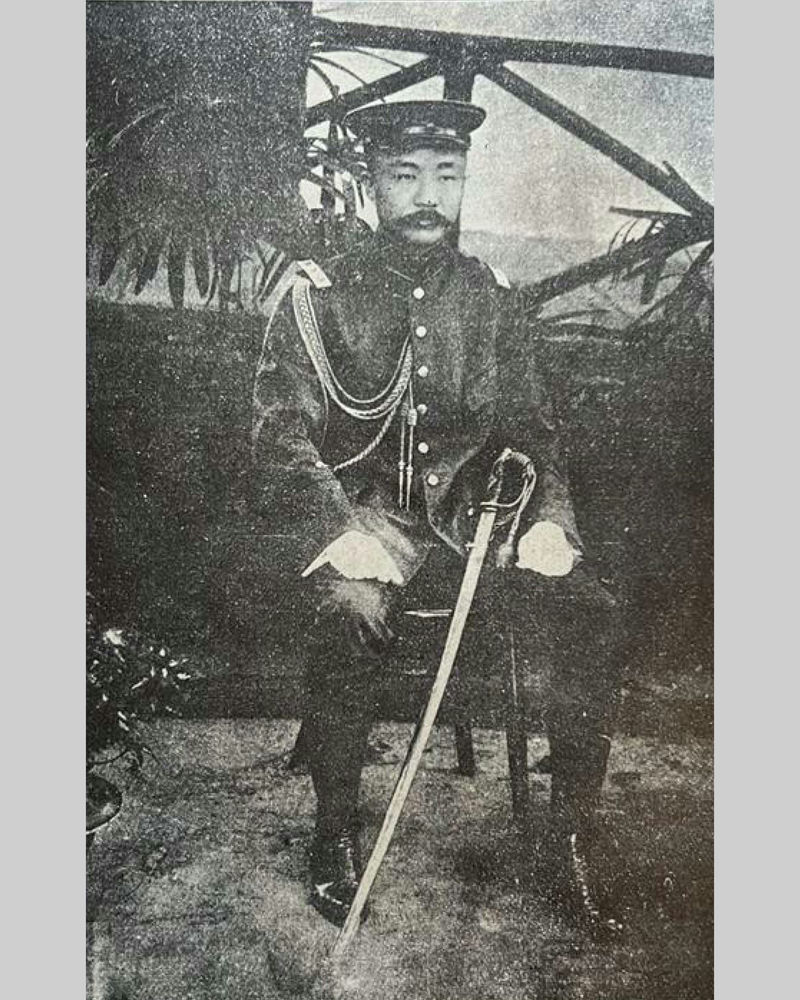

Portrait of Li Lieh-chün

Portrait of T’ang Chi-yao

Ts’ai Sung-p’o was preoccupied in the battlefield and did not have time to attend his illness. When victory arrived, his throat illness or some claimed it to be tuberculosis, was no longer healable. He arrived at the Kyushu Imperial University Hospital in Fukuoka in September of the 5th year of the Republic (1916), and passed away on 8 November, aged thirty five. On 12 April in the 6th year of the Republic (1917), a state funeral was held behind Wan-shou Temple on Yüeh-lu Mountain, Ch’ang-sha City. Afterwards the central government promulgated that the date 25 December in the 4th year of the Republic (1915), when Yunnan Province declared independence during the campaign against Yüan, be designated as “Remembrance Day of Yunnan’s Revolt to Protect the Republic.”

Body of Ts’ai Sung-p’o on his deathbed in Kyushu Imperial University Hospital

Coffin of Ts’ai Sung-p’o was loaded down from a ship at the port in Shanghai

Coffin procession of Ts’ai Sung-p’o through the waiting crowds

Coffin procession of Ts’ai Sung-p’o through the waiting crowds

Coffin procession of Ts’ai Sung-p’o through the waiting crowds

Ts’ai Sung-p’o studied under Liang Ch’i-chao, while Liang Ch’i-chao fostered Ts’ai Sung-p’o. After the death of Ts’ai Sung-p’o, on 5 December in the 5th year of the Republic (1916), Liang Ch’i-chao and others in Shanghai held a public memorial ceremony. He also wrote Eulogium of Ts’ai Sung-p’o at the Public Memorial Ceremony. Meanwhile he also paid tribute with his relatives at a private ceremony, and wrote a separate Eulogium of Ts’ai Sung-p’o at the Private Memorial Ceremony. It is chronicled as Article Two in the Fifteenth Volume of the Collected Works of Yin-ping Shih (飲冰室文集). Eulogium of Ts’ai Sung-p’o at the Private Memorial Ceremony reads:

“The corpse of Ts’ai Sung-p’o came home from Japan and stopped in Shanghai. It will return to Hunan Province for burial. I, Liang Ch’i-chao his teacher, am participating in the memorial ceremony on my travel. I am also accompanied by my brother Liang Ch’i-hsün (梁啟勳 1876-1965), daughter Liang Ssu-shun (梁思順 1893-1966) and son Liang Ssu-ch’eng (梁思成 1901-1972). We respectfully raise clear wine and various food to pay respect to your spirit. We mourn in private with these words:

Alas! Since the death of my friend Sung-p’o, wherever there is water well in the country, there are people crying. Why should there be need for my futile words. My friend Sung-p’o, you should be the one to mourn me, yet now I am mourning you. How can my grief be curbed? You have followed me since the beginning of youth. In haste, it has been twenty years. You were sitting in the corner of the classroom in Ch’ang-sha asking difficult questions, you were sitting on a mattress laughing and talking in the Ch’iu-chien-t’ing District of Tokyo. I see these dim shadows whenever I close my eyes. There were not that many days we spent together afterwards. But through letters and spiritual affinity, we shared daily our support and reliance on each other. Between autumn and winter last year, we extinguished the candle across our beds to plot in secret, we brought our separate code words at the parting, each word and each sentence, have been forever engraved in my heart. Three months ago we had our last intimate conversation in Shanghai. Your weak voice and frail appearance, your rigorous mind and grand spirit, this image is still faintly here. Is it you Sung-p’o? Is it you Sung-p’o? You have unexpectedly abandoned me in the middle of the road. Why have you departed? Alas! During the Boxer Rebellion, your ancestors and your dear friends were exterminated, and you were only a split second away from death. You thus worked diligently to train an army, but you already decided to die for our country that day. You did not die in Kwangsi in i-ssu year (1905), you did not die in Yunnan in hsin-hai year (1911), last winter you did not die in Hu-kuo Temple Street, this spring you did not die in Ch’ing-lung-tsui. It was natural for you to view life as just some spare change of existence. Today you have died for a momentous cause for our nation, of course it is an appropriate duty. However, my friend Sung-p’o, for you to honour our country, this is your way! As long as you do not come back as a corpse wrapped in fur on a horseback from some forsaken land, I know you cannot close your eyes even in the underworld. Alas! If there is deep regret in your life, I dare not tell others of it. In short, today’s society is filled with infinite evil, all quarters want to shove you to your death. What words do I muster to question Heaven? Oh, Sung-p’o! You were born in a time of decline, indeed one might as well die in order to return to true nature. Your father has waited in the underworld for fifteen years to tell you his hardships. Half of your teachers and friends are already there. They have cast aside their grievances, and they will greet you and be close to you. Oh, Sung-p’o! People of this world, they are not your companions. Have you not also escaped from this emptiness and loneliness to preserve your spirit? We will not burden you with our tribulations, otherwise in the underworld, there will still be long sighs and frowns. Alas! I am an inauspicious person in this world. Why have you been so close to me? I count the number of true-friends in my life, they have left me one after the other like fallen leaves of bamboo, there are hardly any left. Not to dwell on the distant past, what about those nearer? Ju-po (孺博, 麥孟華 1875-1915), Yüan-yung (遠庸), Chüeh-tun (覺頓, 湯覺頓 1878-1916), Tien-yü (典虞), they were all distinguished men among millions, all wasted midway before reaching forty. Oh! Heaven does not wish me to attain any other achievements. Why dispense punishment not on my body but on that of my student? Not to mention the infinitude of parental kindness and the kinship of brotherly attachment. Blood flows when tears desiccate, souls rejoin in bygone time. My friend Sung-p’o! How can you bear preserving your own purity without me? Alas! I have a brother whom you know well. I have a group of children whose company you enjoy. I lead them here to pay our respect, to requite your spirit, and to remember you forevermore. To hold the incense in my heart, to clasp the wine vessel melded in tears, the mild sunshine, the pretty scenery, the banners imbued with your spirit, fluttering in the wind. In grief I watch your soul come home. Alas! Such woe! I proffer these offerings for your enjoyment.”

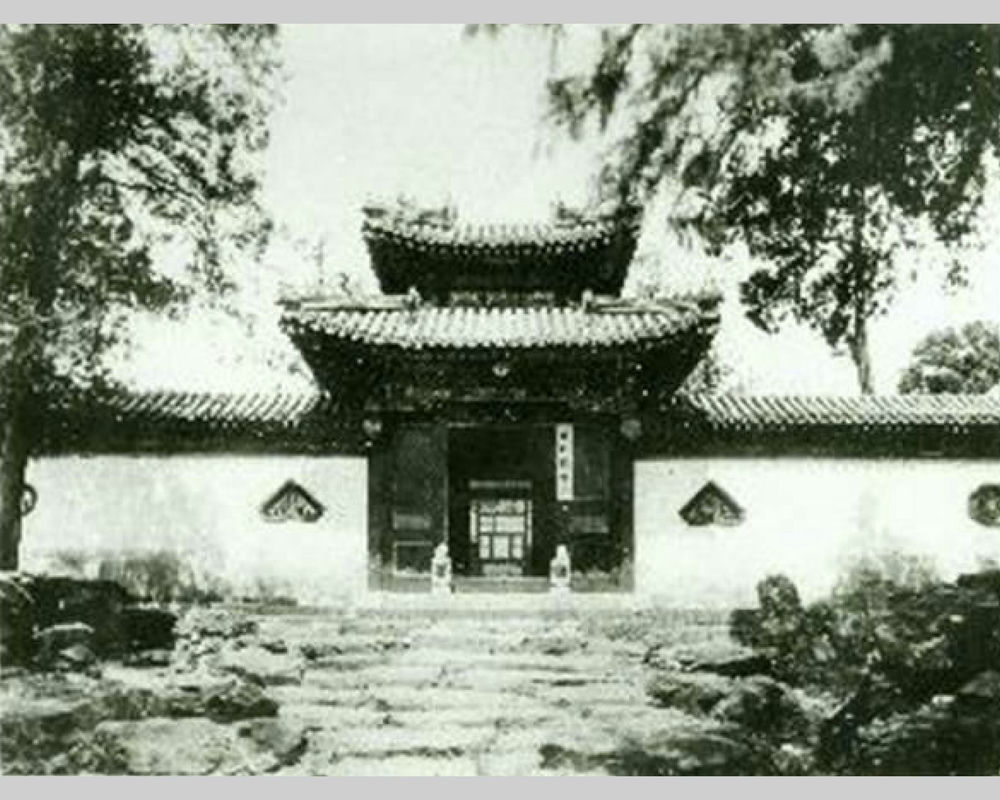

Sung-p’o Memorial Library at K’uai-hsüeh T’ang in P’ei-Hai, Peking

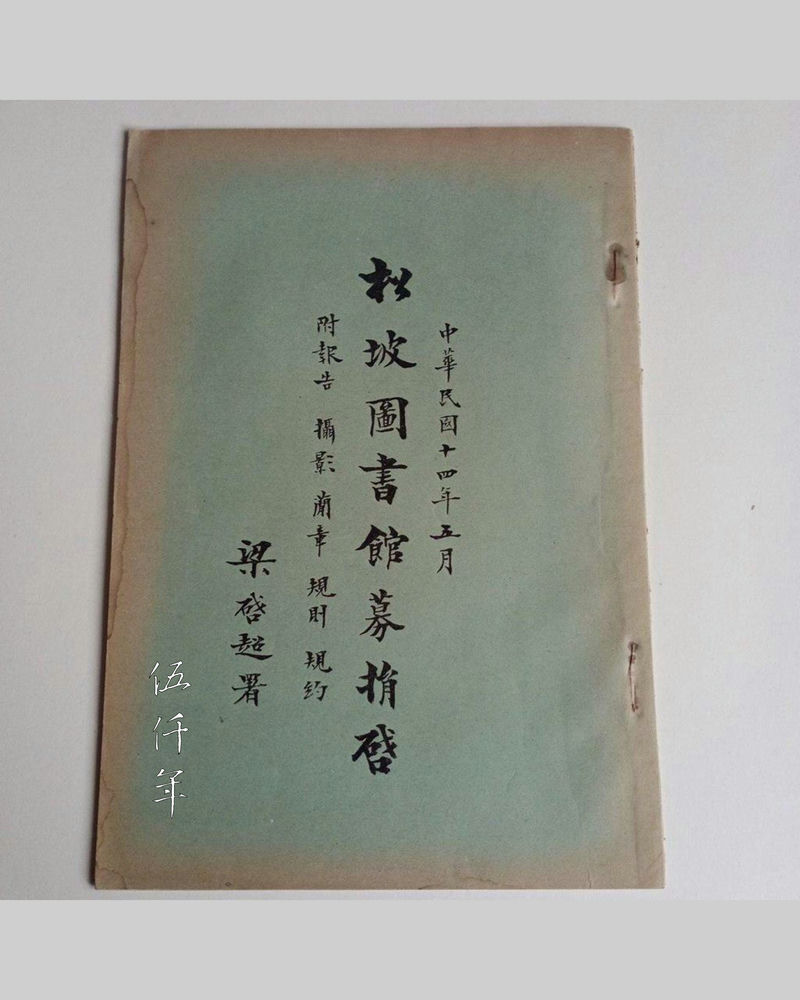

Fundraising Brochure for Sung-p’o Memorial Library, title calligraphed by Liang Ch’i-chao

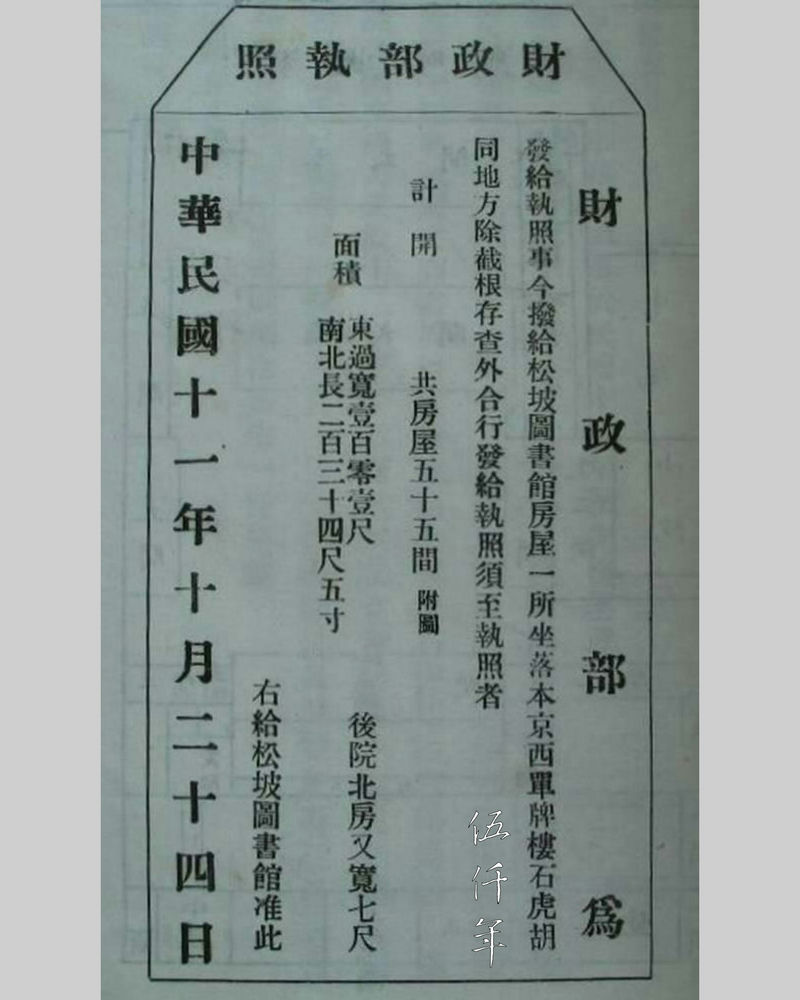

Permit issued by Department of Finance for Sung-p’o Memorial Library

Ts’ai Sung-p’o passed away in November in the 5th year of the Republic (1916). Liang Ch’i-Chao was grief-stricken by the news. On 5 December, a memorial ceremony was held in Shanghai. In the same month, Liang Ch’i-chao initiated the preparatory work to establish the Sung-p’o Memorial Library. In November in the 7th year of the Republic (1918), the Sung-p’o Memorial Library opened on Bishop’s Road in Hsü-hui District in Shanghai. In the 12th year of the Republic (1923), the Memorial Library relocated to K'uai-hsüeh T’ang in Pei-hai in Peking. Liang Ch’i-chao became the director. On 12 April in the 6th year of the Republic (1917), Ts’ai Sung-p’o was buried at Yüeh-lu Mountain in Ch’ang-sha. At that time, Liang Ch’i-chao was in Peking and could not travel to Hunan Province. He asked his close friend T’ang En-p’u to ghostwrite Eulogium of General Ts’ai Sung-p’o at the State Funeral. This piece of writing has not been previously publicized. It is a lost artefact of modern history to be treasured.

If there were no Liang Ch’i-ch’ao and Ts’ai Sung-p’o, the teacher and student duo who condemned and fought against the enthronement of Yüan Shih-k’ai, Yunnan Province might not have declared independence, and the political inclinations of all the other provinces would be difficult to predict. For the deliverance of the democratic system of the Republic of China, contributions made by Liang Ch’i-Chao and Ts’ai Sung-p’o were immense. However, calamities are to continuously assault the democratic system of the Republic of China. Twenty one years later, Japan invaded China, in another twelve years, mainland China fell to the communists. Today an Imperial system in disguise has occupied mainland China for over seventy years. If the spirits of Liang Ch’i-chao and Ts’ai Sung-p’o have not dispersed in the wind, surveying the vast landscape of rivers and mountains, overseeing the billion toiling humans, how can they still savour free and easy wanderings in another world?

Tomb of Ts’ai Sung-p’o at Yüeh-lu Mountain in Ch’ang-sha

Related Contents:

Liang Ch'i-chao (梁啟超) and the Garden of Myriad Lives Gathering