Inkwells and paper weights made of bronze are practical utensils. They were commonplace in stationery shops a number of decades back. However those made by distinguished artists are few from the beginning. Even in those days, they could be encountered only once in a while. Works by Yao Hua (姚華 1876-1930) occasionally turned up, while works by Ch’en Heng-k’ei (陳衡恪 1876-1923) were quite rare. Today, connoisseurs pursue their works on bronze as treasured artefacts.

Mr. T’ang En-p’u was a close friend of Yao Hua and Ch’en Heng-k’ei. They enjoyed the pleasures of life in each other’s company in Peking during the early years of the founding of the Republic of China. Hence, amongst the belongings of T’ang En-p’u after he passed away, there was a pair of engraved bronze paper weights by Ch’en Heng-k’ei, and two engraved bronze inkwells by Yao Hua. They are objects imbued with deep friendships. Time has moved on and these accoutrements are mostly disused. To recall those early years of the Republic, when literary writings and calligraphy overflowed in abundance, when scholars and literati indulged in genuine refinement, those from later generations can only be prodigiously enthralled.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

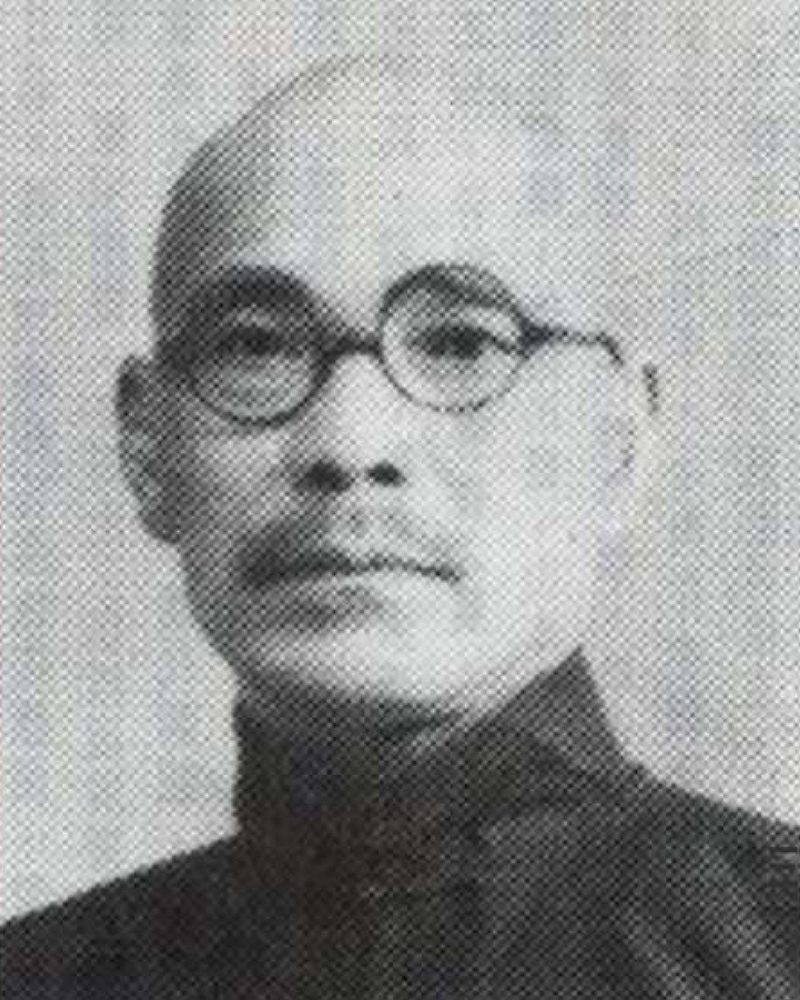

In the 50th year of the Republic (1961), the renowned chü-jen (舉人 attainer of the imperial degree of provincial graduate) from Kwangtung Province, T’ang En-p’u (唐恩溥), died of illness in Hong Kong at the age of eighty one. Amongst his belongings, there were three pieces of desk accoutrements made of bronze: a pair of engraved bronze paper weights by Ch’en Heng-k’ei (陳衡恪) and two engraved bronze inkwells by Yao Hua (姚華). Ch’en Heng-k’ei and Yao Hua were celebrities in the artistic circles of Peking. They were also intimate friends of T’ang En-p’u.

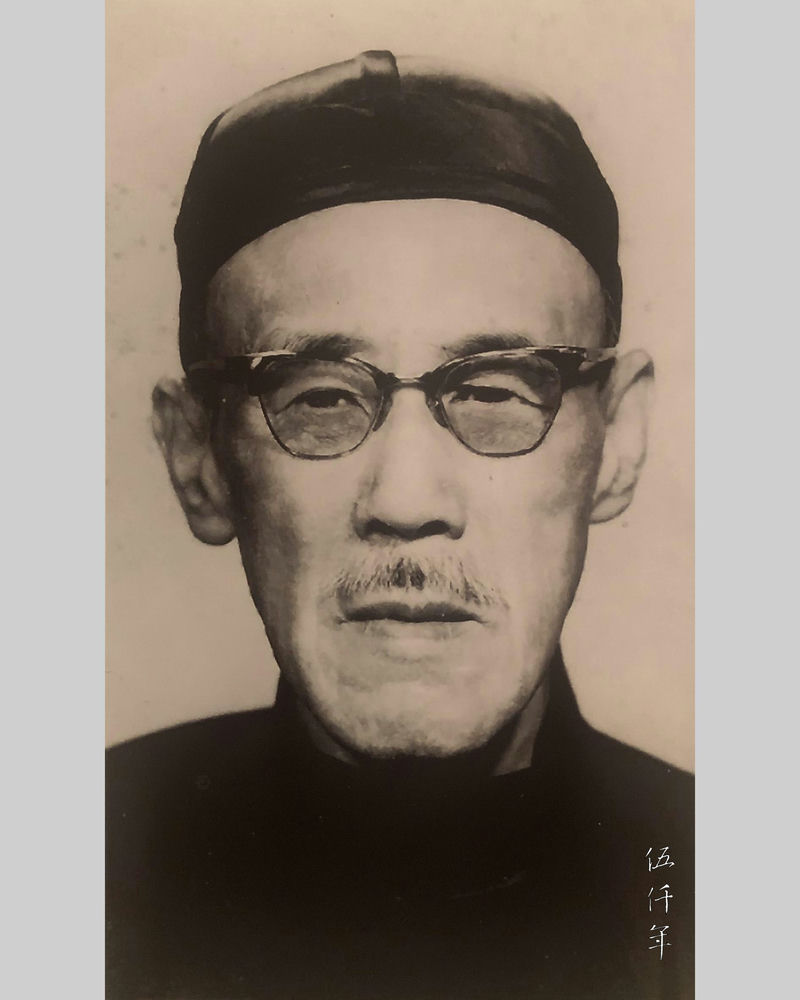

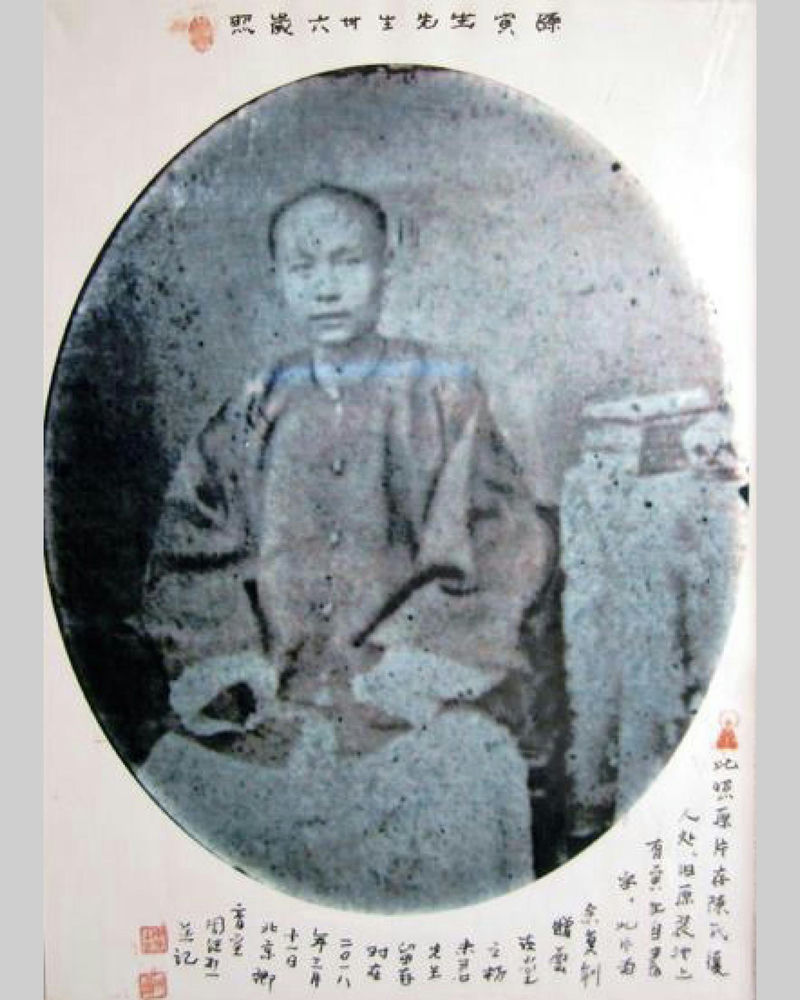

Portrait of Mr. T’ang En-p’u

Yao Hua once inscribed an album of ink rubbings of the Princess Tai-kuo-ch’ang Stele (代國長公主碑) from the T’ang dynasty (618-907 AD). His words are:

“Lately, I suffered from tophus a great deal. Lo Fu-k’an (original name Tun-huan), T’ang T’ien-ju (original name En-p’u) and Ch’en Shih-tseng (original name Heng-k’ei) visited me during my illness. I fetched this album for perusal and we admired it for a long time. This episode should not be left undocumented. I chronicled this in the middle of my illness on 15th November of the Chinese Agricultural Calendar, or 1st January of 1912.”

The text is short and simple. The friendships of Yao Hua, Lo Tun-huan, T’ang En-p’u and Ch’en Heng-k’ei are evident. On that day, the four met in Peking on account of Yao Hua’s illness. Even so, they did not neglect to partake in conversations on connoisseurship and the arts, and managed to express their refined sentiments.

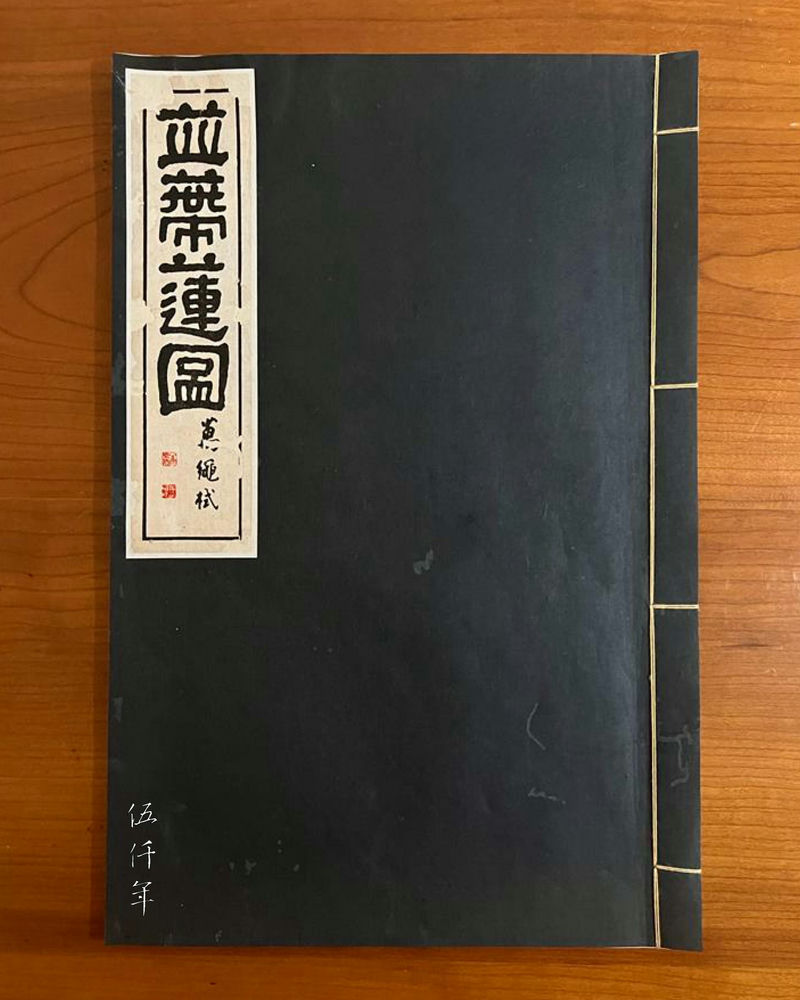

Front cover of the collotype printed book that reproduced the Double Stem Lotus Painting by Ch’en Heng-k’ei

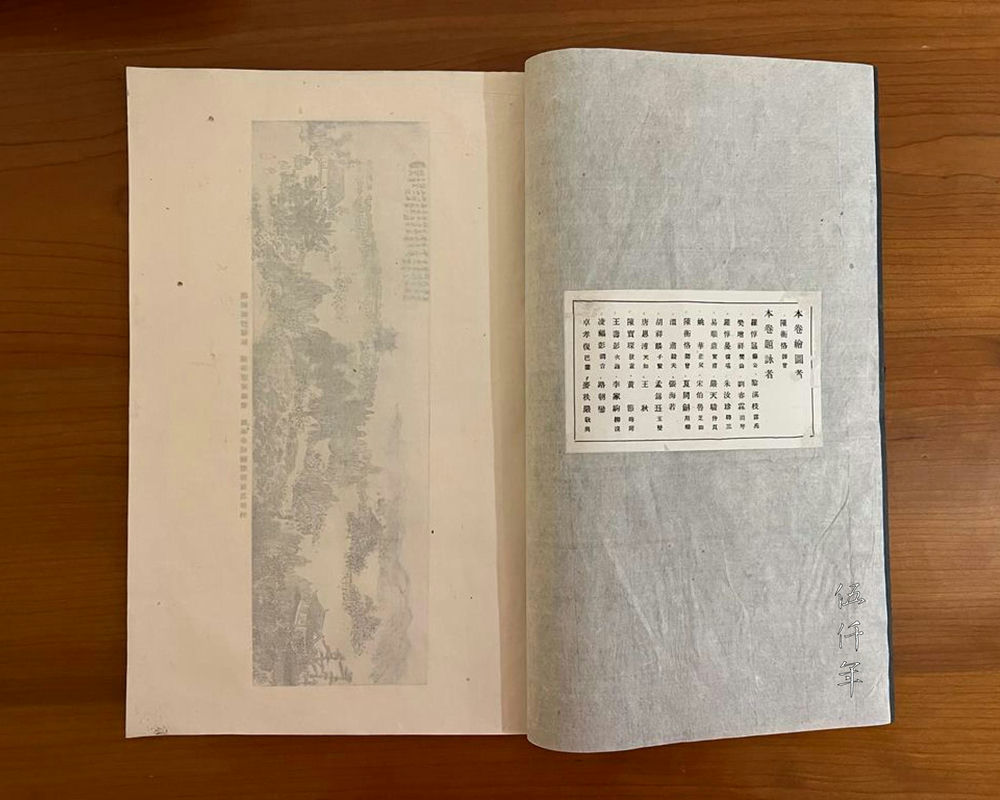

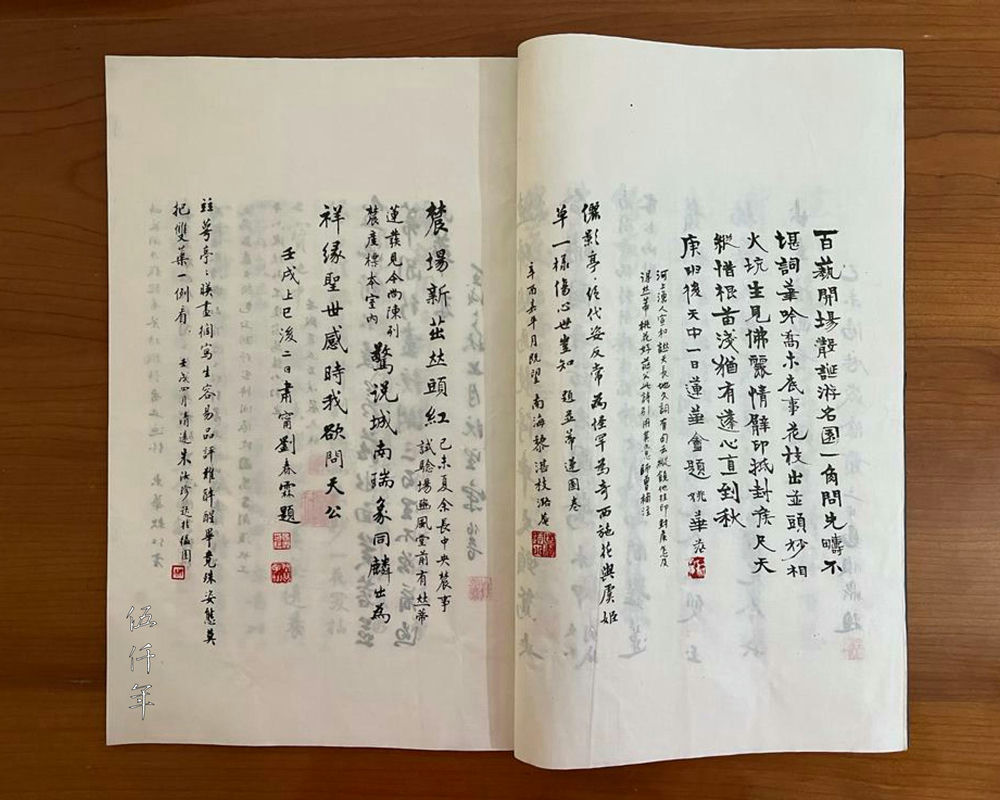

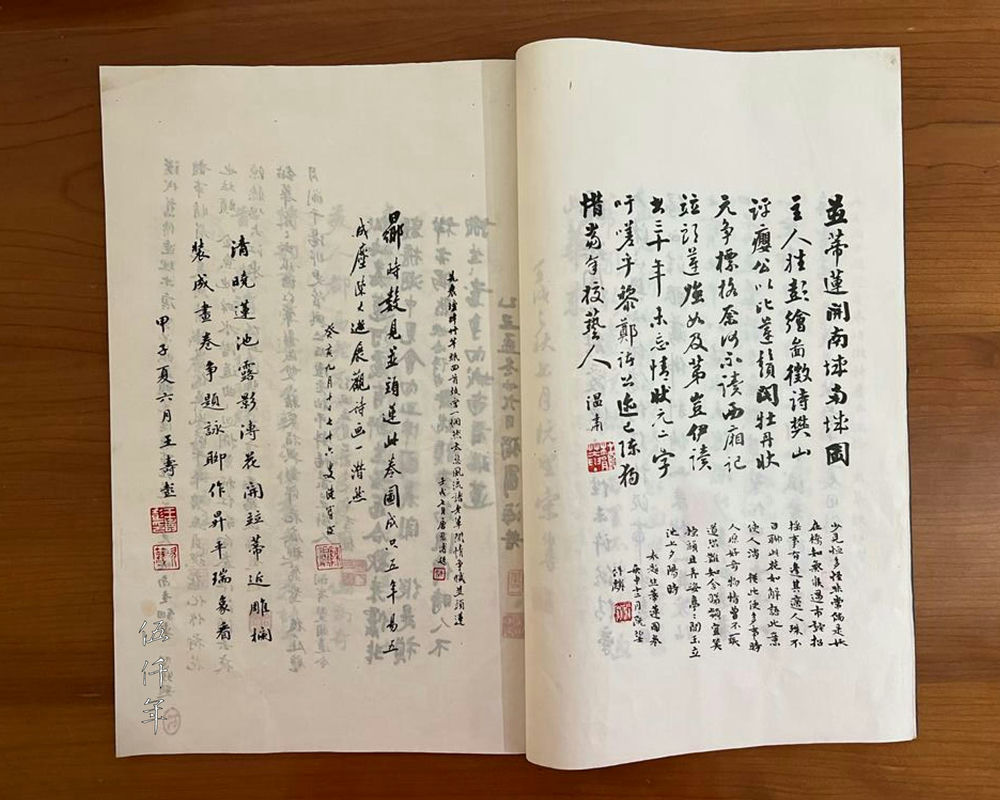

Inside page of the collotype printed book that reproduced the Double Stem Lotus Painting by Ch’en Heng-k’ei, with names of twenty six personages who inscribed after the painting

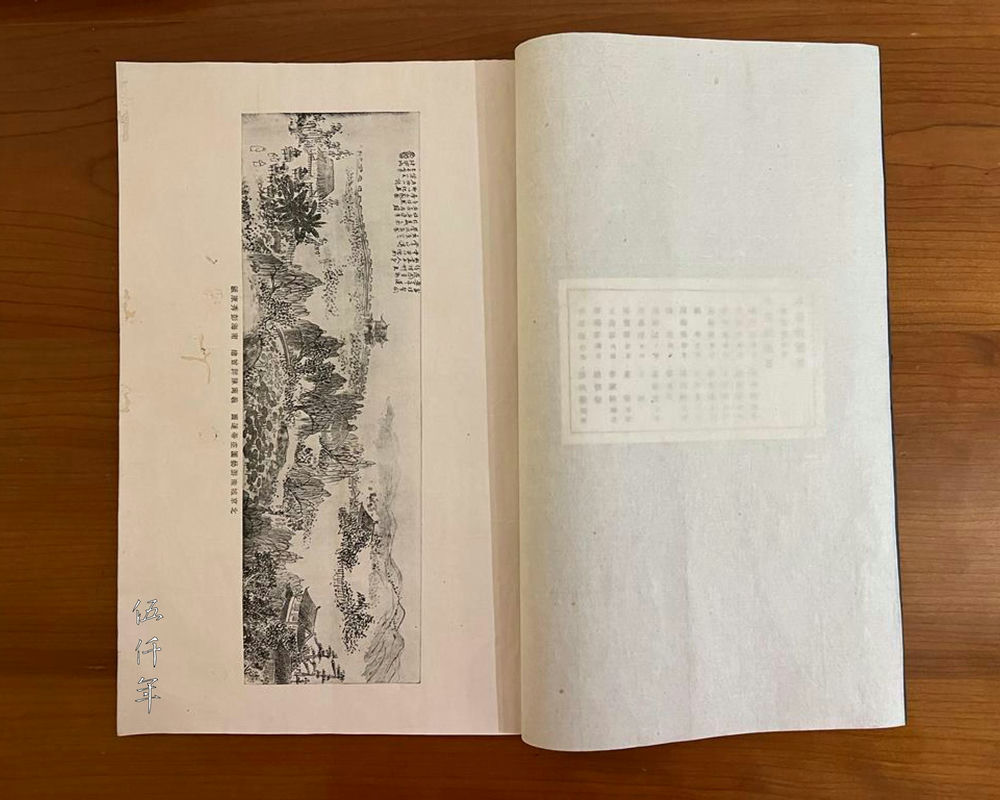

Inside page of the collotype printed book, with the reproduction of the Double Stem Lotus Painting

Amongst the belongings of T’ang En-p’u, there is also a collotype printed book, a reproduction of the Double Stem Lotus Painting by Ch’en Heng-k’ei and dedicated to P’eng Hsiu-k’ang (彭秀康) from Nan-hai, Kwangtung Province in chi-wei year (1919). Twenty six personages inscribed after the painting, including Yao Hua whose inscription was dated keng-shen year (1920), Ch’en Heng-k’ei who added an inscription next to that of Yao Hua, and T’ang En-p’u whose inscription was dated jen-hsü year (1922). T’ang En-p’u treasured this book for decades, for it was a relic that recalled long ago friendships in Peking.

Inside page of the collotype printed book that reproduced the Double Stem Lotus Painting by Ch’en Heng-k’ei, with inscriptions by Yao Hua and Ch’en Heng-k’ei (the first and second inscriptions on the right page)

Inside page of the collotype printed book that reproduced the Double Stem Lotus Painting by Ch’en Heng-k’ei, with inscription by T’ang En-p’u (the first inscription on the left page)

T’ang En-p’u (1881-1961) was also known as Chao-p’u (兆溥), tzu Ch’i-chan (啟湛), T’ien-ju (天如), native of Hsin-hui, Kwangtung Province. He attained the chü-jen degree (provincial graduate) in the 29th year of Kuang-hsü reign (1903). In the 5th year of the Republic (1917), he relocated to Peking. He was first appointed assistant editor of the Bureau of Historia Ch’ing, and then editor. Between the 8th year and the 13th year of the Republic (1919-1924), he moved to Hong Kong, yet he still made frequent visits to Peking and Tientsin. In the 14th year of the Republic (1925), he was introduced by Chang I-chiu (張一麔) and his fellow chü-jen examination candidate Chang Ch’i-huang (張其鍠) to the warlord Wu P’ei-fu (吳佩孚), and became his assistant secretary. T’ang En-p’u was accomplished in prose and excelled in medicine.

Sketch portrait of Yao Hua

Yao Hua at the Garden of Myriad Lives Gathering in 1913

Yao Hua (1876-1930), tzu Chung-kuang (重光), I-o (一鄂), hao Mang-fu (茫父), Lien-hua An-chu (蓮花盫主), Fu-t’ang (弗堂), native of Kuei-yang, Kweichow Province. He attained the chin-shih degree (metropolitan graduate) in the 30th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1904). From the first year of the Republic (1912) to the 2nd year of the Republic (1913), he was elected senator of the provisional senate. In the third year of the Republic (1914), he was appointed president of the Ladies’ Normal School of Peking. In the following year, he was appointed painting teacher at the Advanced Normal School of Peking as well as general subjects teacher at the Ladies’ Normal School of Peking. In the 7th year of the Republic (1918), he was appointed painting tutor at the Society of Painting Studies in the National Peking University and the Specialized Art School of Peking. In the 13th year of the Republic (1924), he was appointed president of the Ching-hua Specialized Art School. He was accomplished in poetry and tz’u lyrics. He was also skilled in calligraphy and painting. Occasionally he practiced the art of seal engraving. He was fond of pictorial engravings on bronze, making paper weights and inkwells.

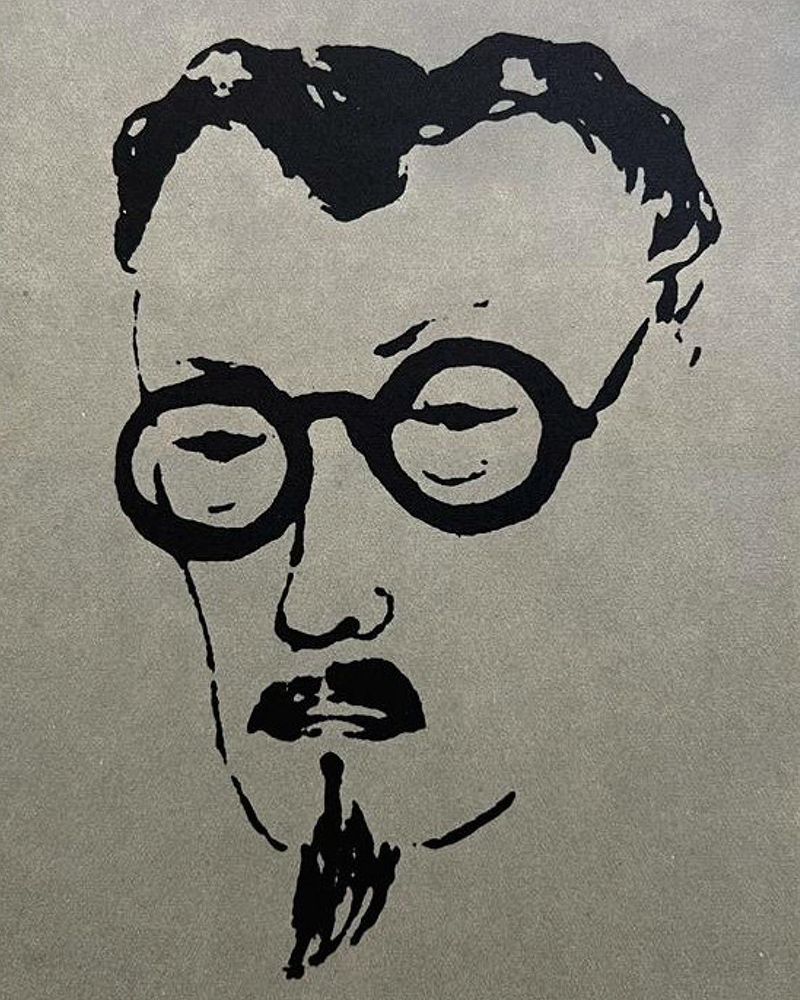

Sketch portrait of Ch’en Heng-k’ei

Portrait of Ch’en Heng-k’ei

Ch’en Heng-k’ei (1876-1923), tzu Shih-tseng (師曾), hao Hsiu Tao-jen (朽道人), Huai-t’ang (槐堂), native of Nan-ch’ang, Kiangsi Province, but born in Hunan Province. His grandfather Ch’en Pao-chen (陳寶箴 1831-1900) was governor of Hunan Province. His father Ch’en San-li (陳三立 1853-1937) was a distinguished poet. The eminent scholar of the early Republic, Ch’en Yin-k’ei (陳寅恪 1890-1969), was his fifth brother. In the 4th year of the Republic (1915), he was appointed painting teacher at the Advanced Normal School of Peking, as well as general subjects teacher at the Ladies’ Normal School of Peking. In the 7th year of the Republic (1918), he was appointed painting tutor at the Society of Painting Studies in the National Peking University. He was accomplished in poetry and skilled in the art of seal engraving. He was also fond of pictorial engravings on bronze, making paper weights and inkwells.

Ch’en Heng-k’ei and Yao Hua both lived in Peking, shared common interests, taught at the same schools, and saw each other regularly. In the 11th year of the Republic (1922), when Ch’en Heng-k’ei published The Studies of Chinese Literati Paintings (Chung-Kuo wen-jen hua chih yen-chiu 中國文人畫之研究), he asked Yao Hua to write the introduction. It had been known that a number of personal seals used by Yao Hua were carved by Ch’en Heng-k’ei. They are the six seals of : “Yao Hua (姚華)”, “Chung-kuang (重光)”, Lao-mang (老茫)”, “Mang-k’ung (茫公)”, “Fu-t’ang chin-shih (弗堂金石)”, “Kan ling-kuei i-wei hsing (感靈媯以為姓)”.

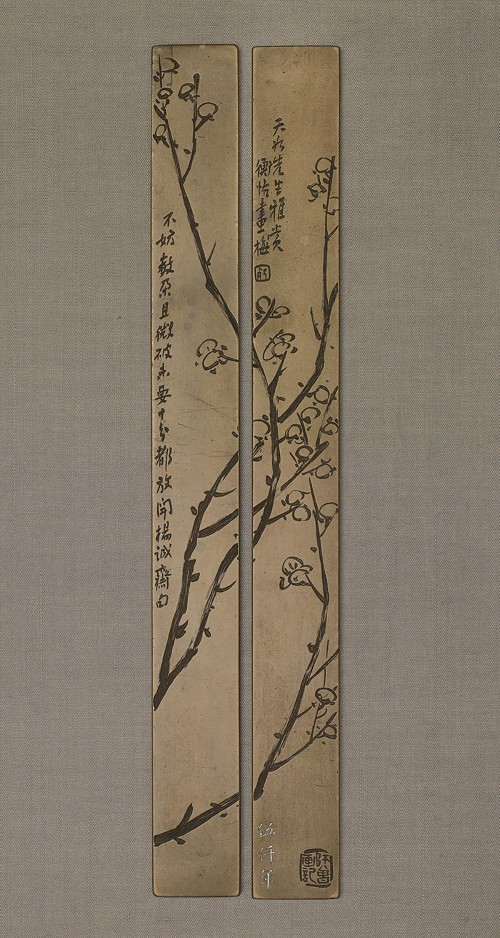

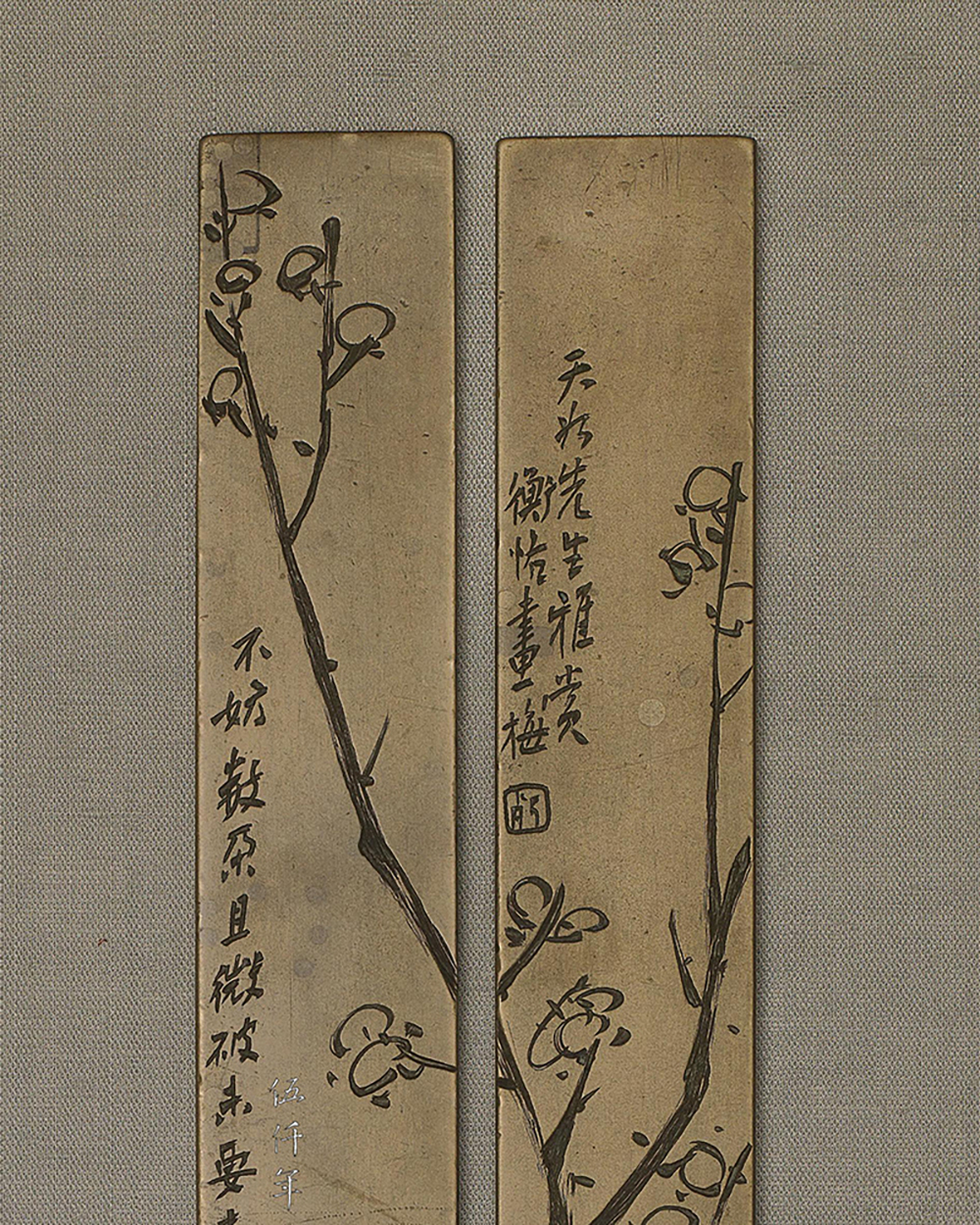

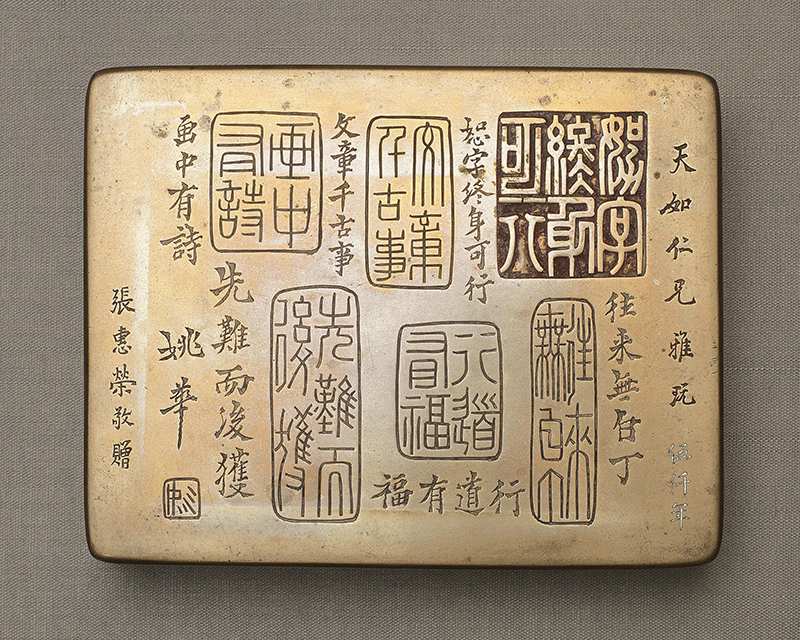

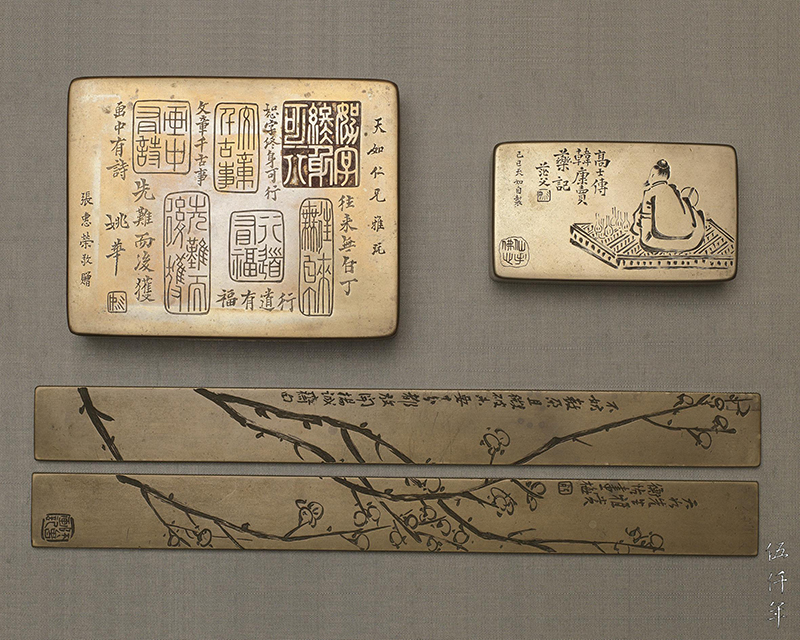

The pair of bronze paper weights by Ch’en Heng-k’ei dedicated to Mr. T’ang En-p’u

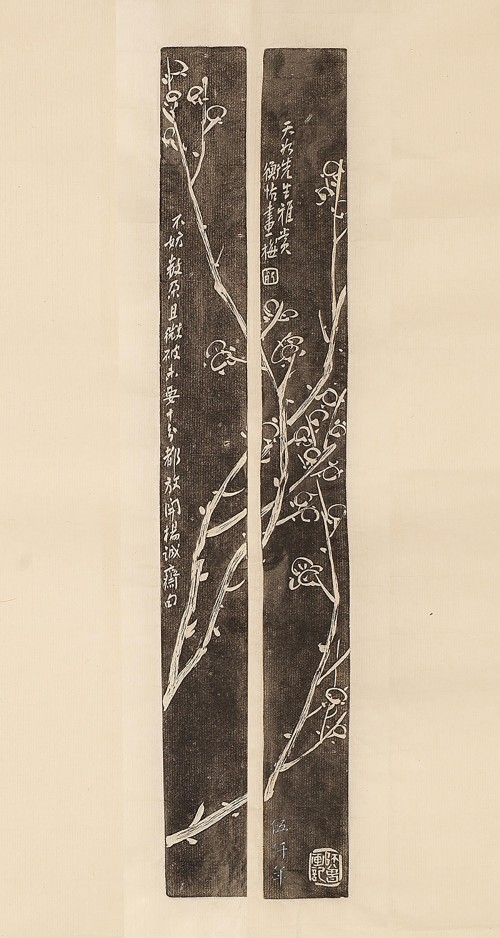

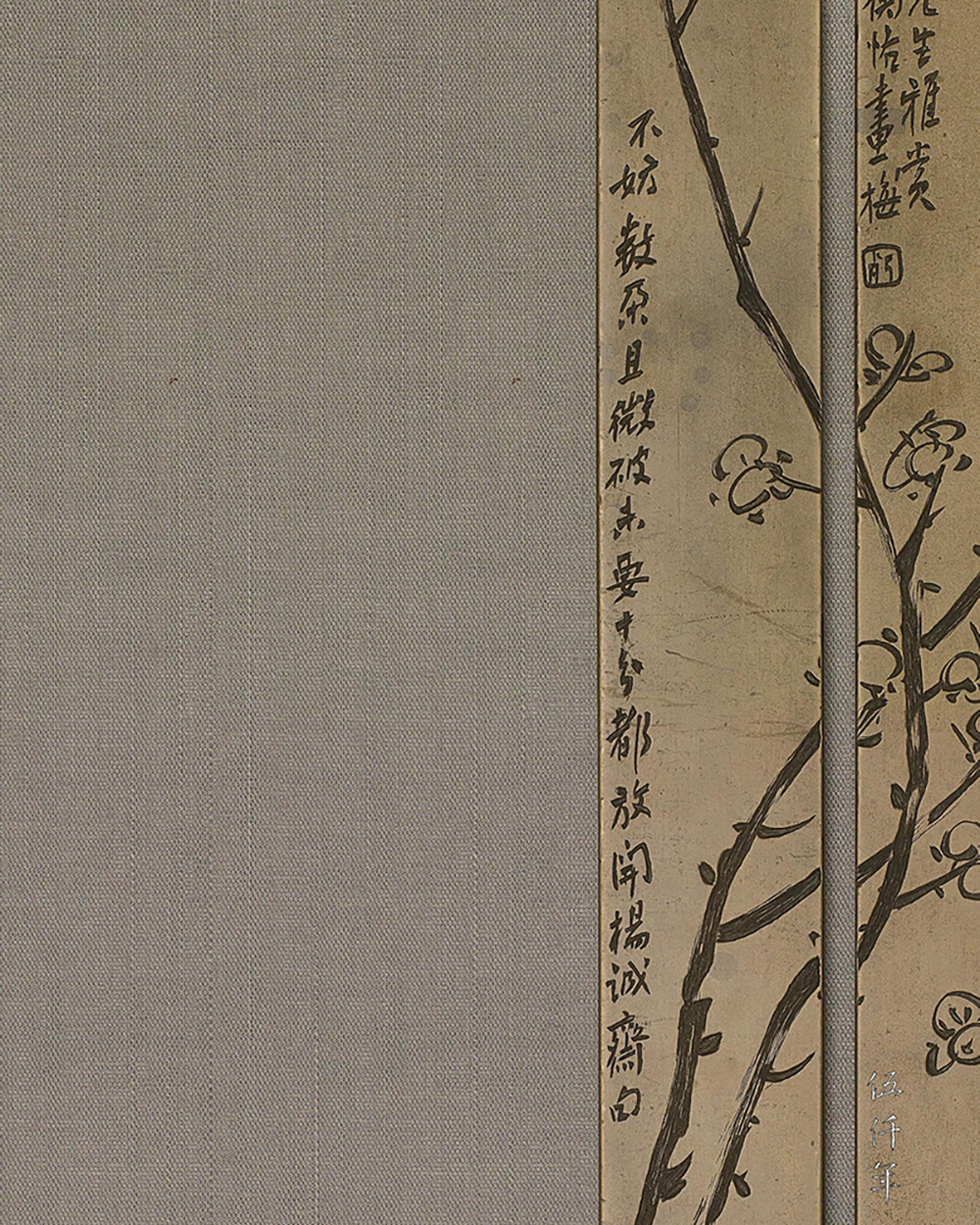

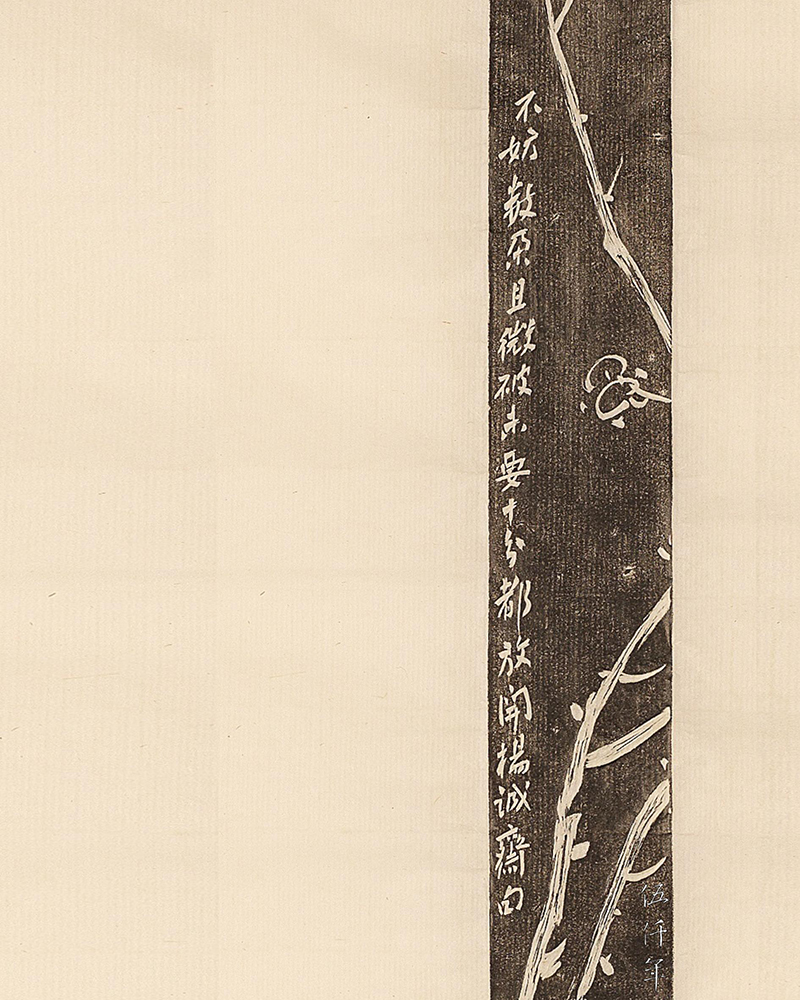

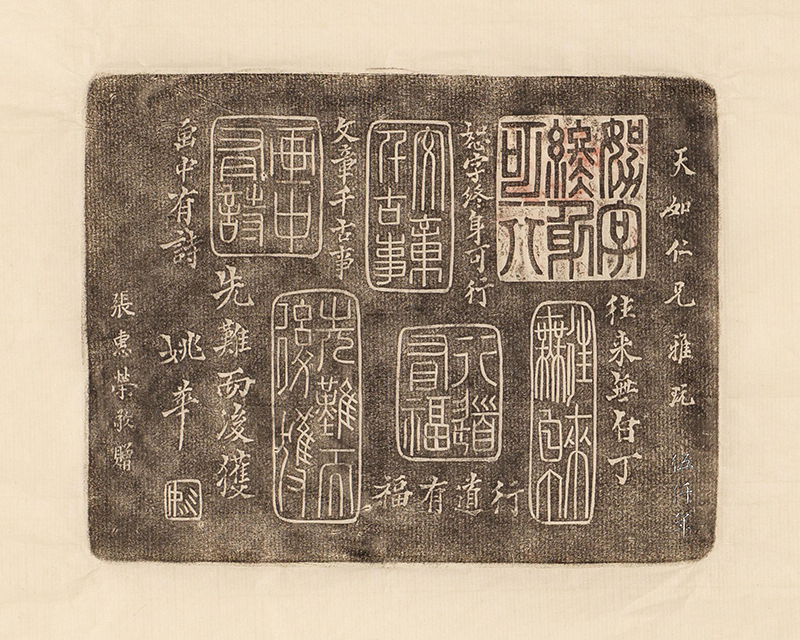

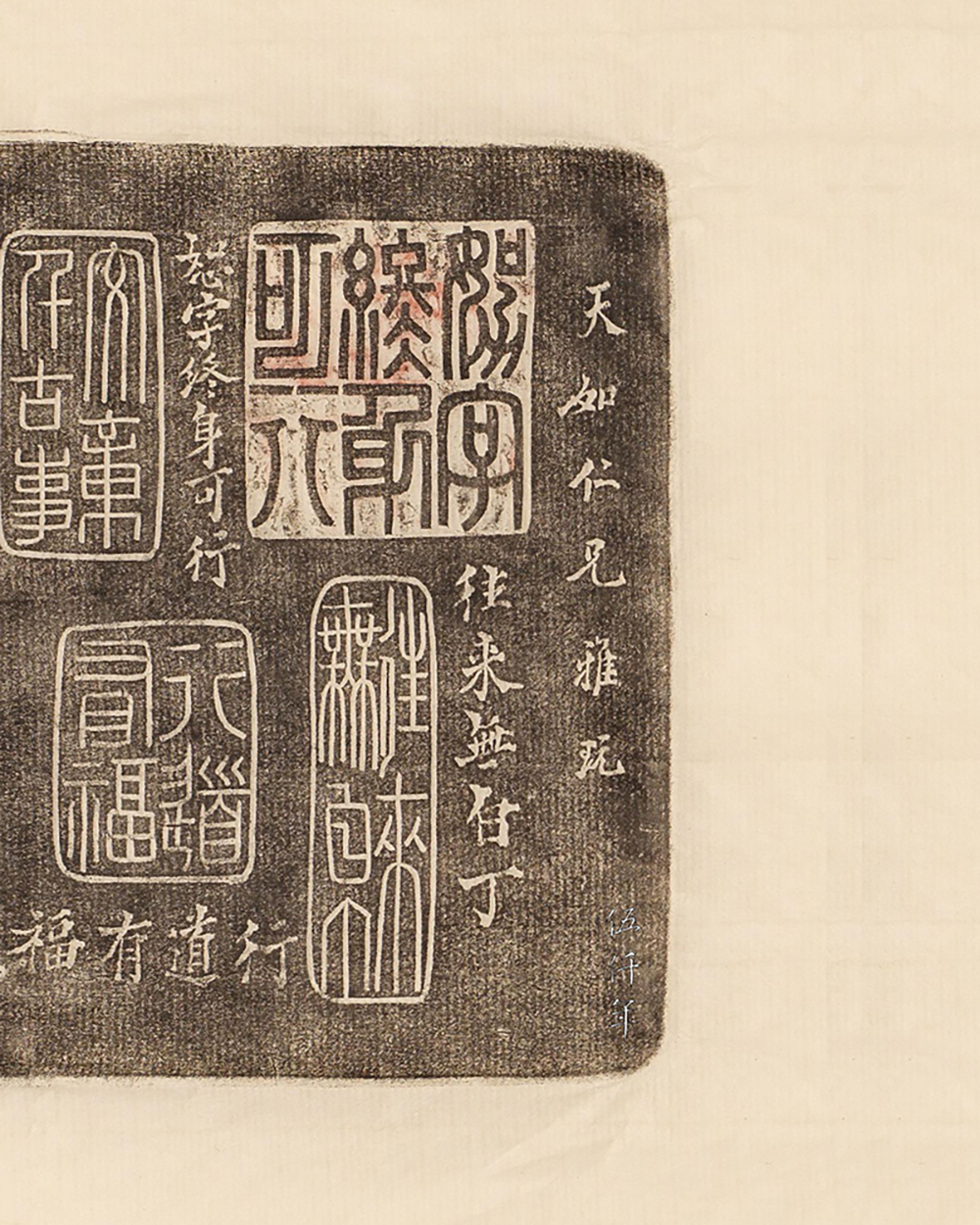

Ink rubbing of the pair of bronze paper weights by Ch’en Heng-k’ei dedicated to Mr. T’ang En-p’u

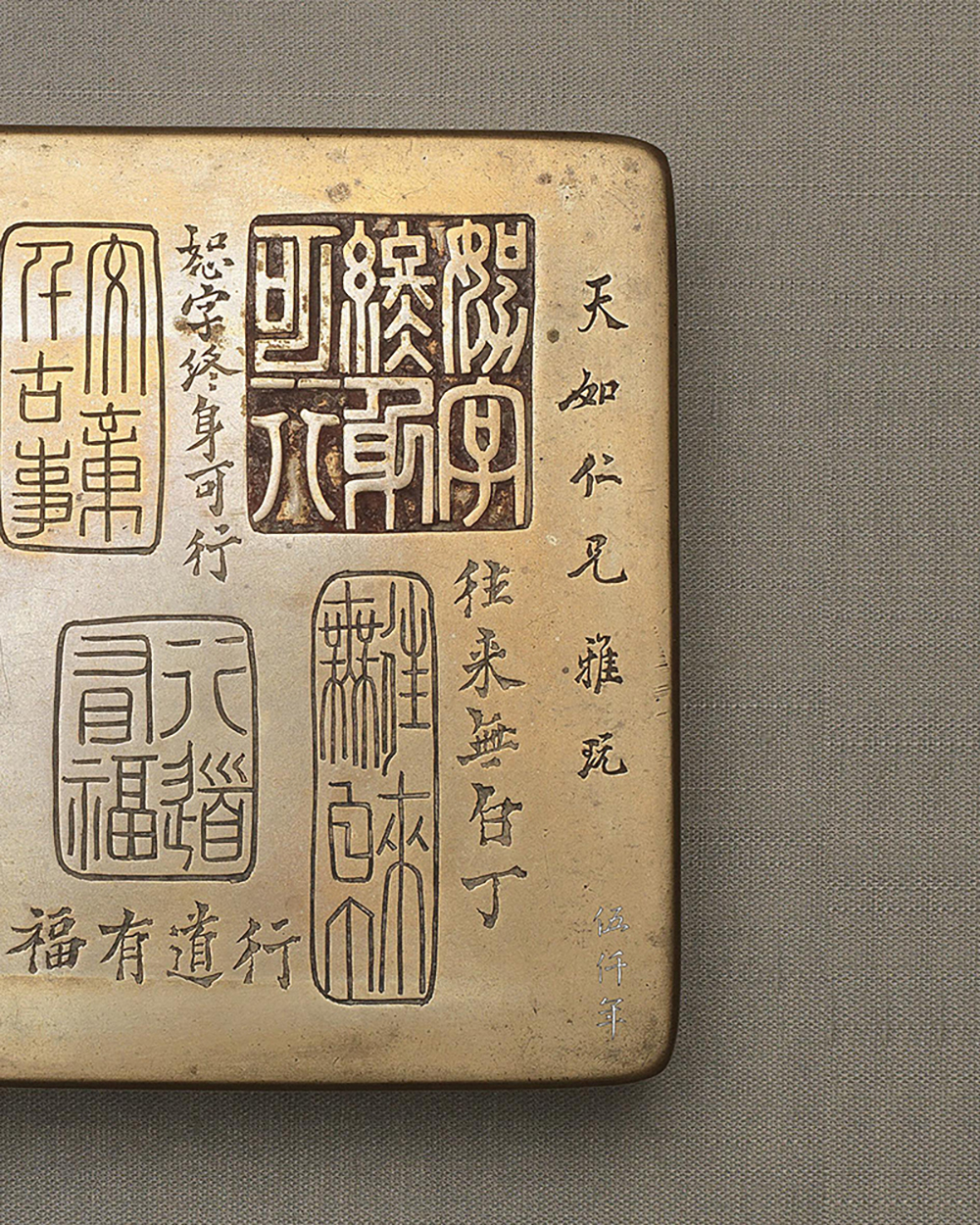

First detail of the pair of bronze paper weights by Ch’en Heng-k’ei dedicated to Mr. T’ang En-p’u

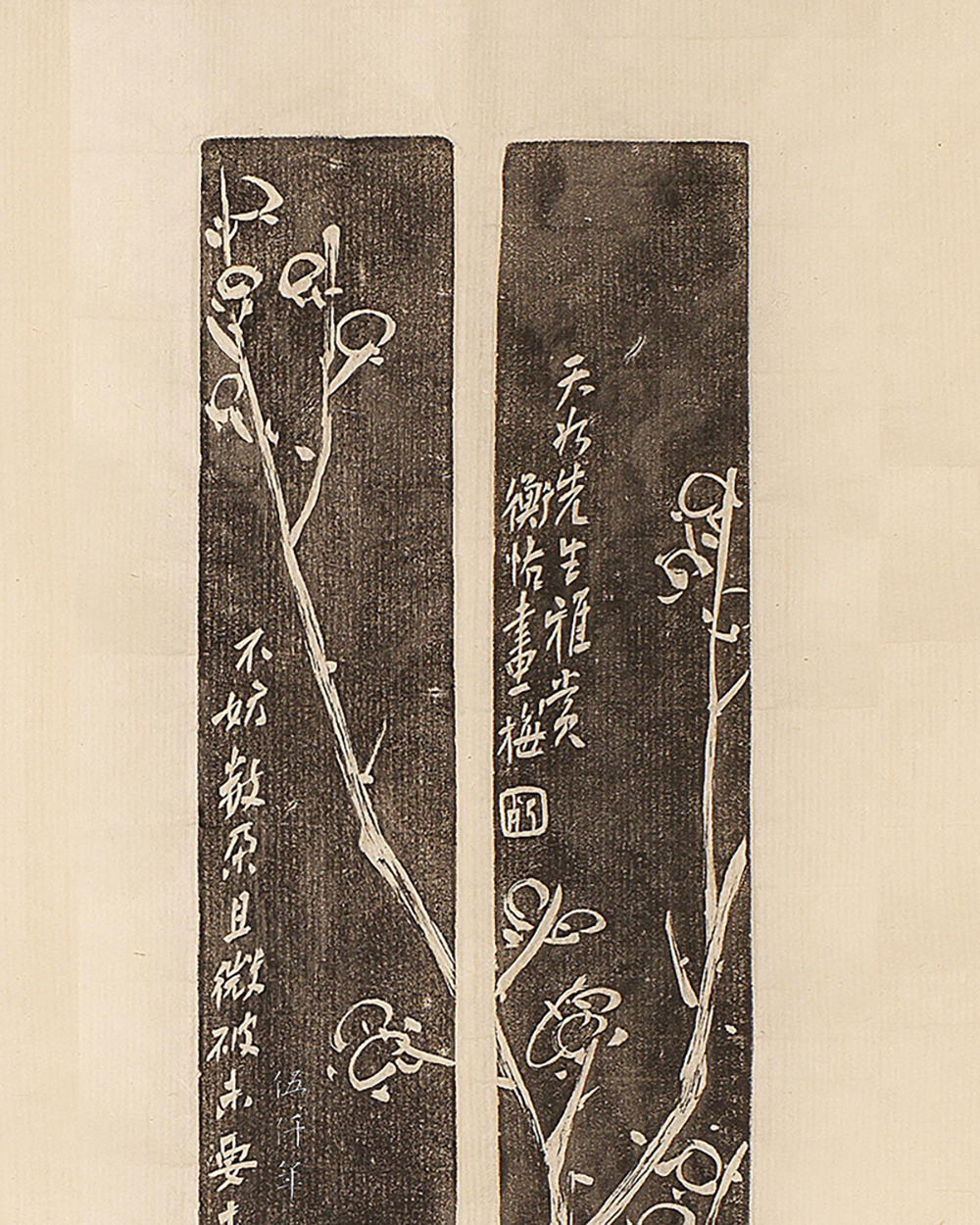

Ink rubbing of first detail of the pair of bronze paper weights by Ch’en Heng-k’ei dedicated to Mr. T’ang En-p’u

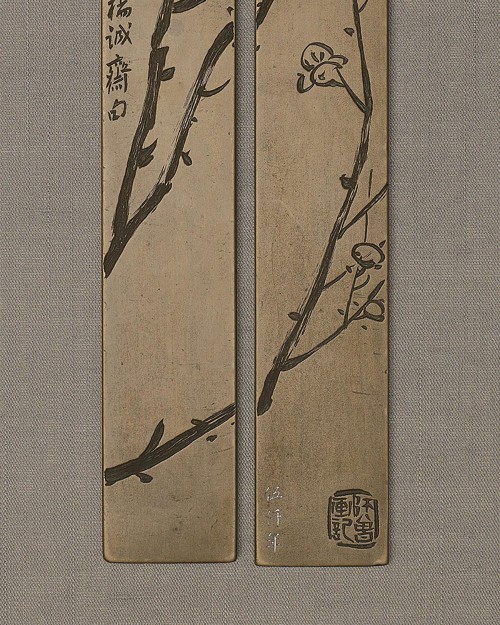

Second detail of the pair of bronze paper weights by Ch’en Heng-k’ei dedicated to Mr. T’ang En-p’u

Ink rubbing of second detail of the pair of bronze paper weights by Ch’en Heng-k’ei dedicated to Mr. T’ang En-p’u

Regarding the pair of bronze paper weights Ch’en Heng-k’ei dedicated to Mr. T’ang En-p’u, they were incised with a few stalks of prunus, the one on the right and the one on the left merge to form a complete diptych picture. The weight on the right was additionally engraved with two lines of cursive script writings:

For the refined perusal of Mr. T’ien-ju.

Heng-k’ei painted the prunus.

Two seal legends were also engraved: “Hsiu” and “To chronicle a painting by Shih-tseng”.

Third detail of the pair of bronze paper weights by Ch’en Heng-k’ei dedicated to Mr. T’ang En-p’u

Ink rubbing of third detail of the pair of bronze paper weights by Ch’en Heng-k’ei dedicated to Mr. T’ang En-p’u

The weight on the left was additionally engraved with a line of poetry in cursive script which reads:

Don’t bother with a few torn petals,

Don’t expect all to be in full bloom.

Sentence by Yang Ch’eng-chai (楊誠齋).

Yang Ch’eng-chai (1127-1206), original name Wan-li (萬里), tzu Yen-hsiu (延秀), native of Chi-shui, Kiangsi Province. He attained the chin-shih degree in the 24th year of the Shao-hsing reign in the Sung dynasty. During the Kuang-tsung reign, he was appointed director of the Palace Library and the fiscal assistant commissioner of Chiang-tung. He then declined further appointments. During the Ning-tsung reign, he was appointed academician of Pao-mo Ko. He was awarded the posthumous name Wen-chieh (文節). His collected works is titled Ch’eng-chai chi (Collected Works of Ch’eng-chai 誠齋集).

This sentence by Yang Ch’eng-chai is an extract from his poem “A composition on the prunus in front of Tao-shan T’ang on first January in wu-shen year.” It reads:

On this new year day I come not alone,

Fresh spring will be my escort on return.

Evening rain fills the stone water drain,

Eastern wind rustles the Tao-shan prunus.

Don’t bother with a few torn petals,

Don’t expect all to be in full bloom.

Wild scent by riverside road is ever more fair,

Who will fetch it to plant in eden?

Wu-shen year is the 15th year of the Ch’un-hsi reign in Southern Sung dynasty, the equivalent of 1188 of the Gregorian Calendar.

Portrait of Chang Yüeh-ch’en

It was customary for Ch’en Heng-k’ei to first paint the bronze, and then he would entust the bronze to Chang Yüeh-ch’en (張樾臣) of T’ung-ku T’ang in the west of Liu-li-ch’ang to engrave it accordingly. Chang Yüeh-chen (1883-1961), original name Fu-yin (福廕), tzu Yüeh-ch’en (悅臣), also Yüeh-ch’en (樾臣), native of Hsin-ho, Hopeh Province. He was accomplished in seal engraving and bronze engraving, his art of bronze engraving was preeminent in his time. Impressions of his seal engravings were compiled into Shih-i Chü-shih yin-ts’un (士一居士印存).

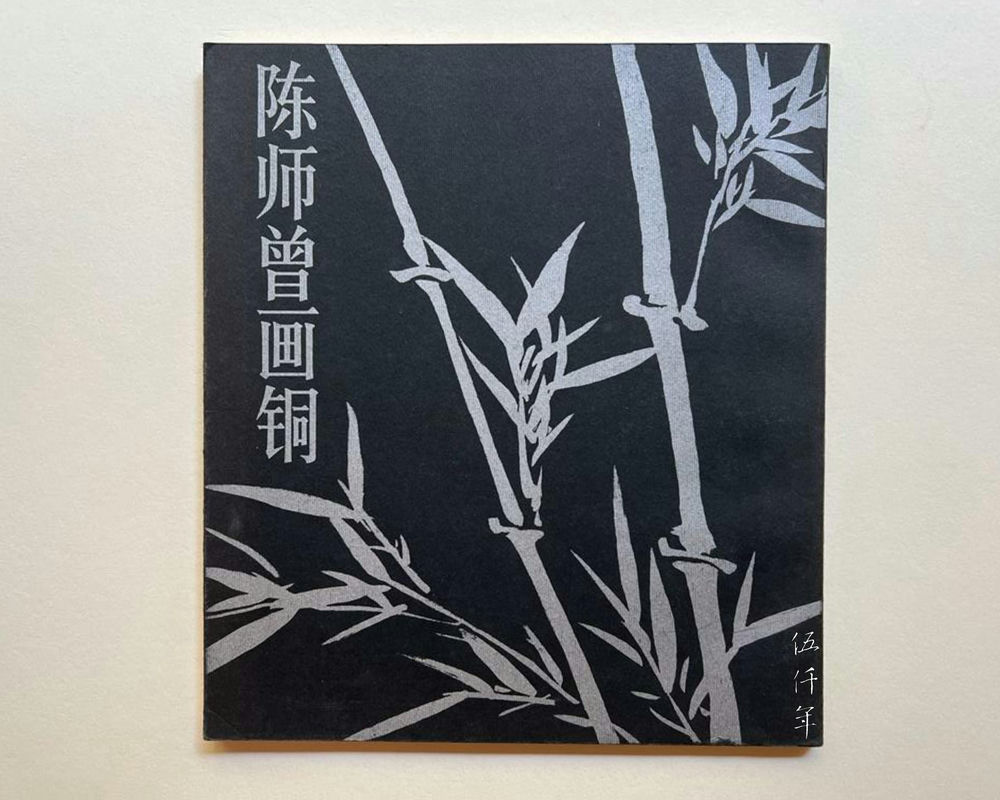

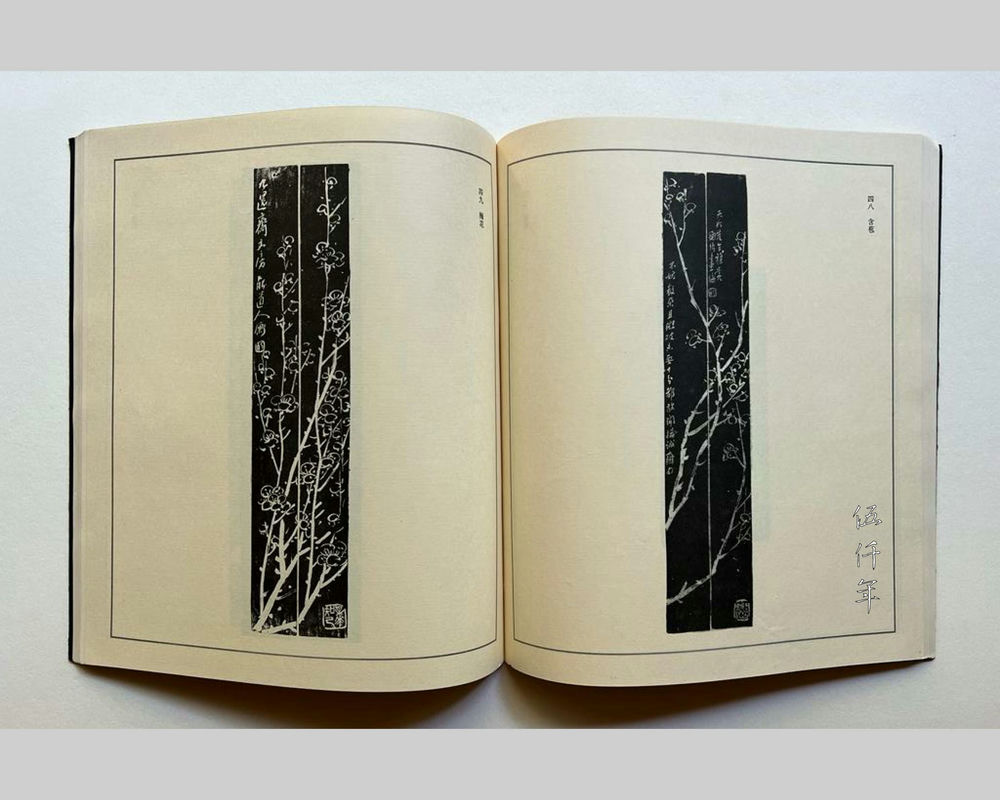

Front cover of The Works on Bronze by Ch’en Heng-k’ei

Inside page of The Works on Bronze by Ch’en Heng-k’ei, illustrating the pair of bronze paper weights dedicated to Mr. T’ang En-p’u

Ch’en Heng-k’ei had left an ink rubbing album of bronze paper weights and inkwells that he painted. There are altogether ninety three sheets of ink rubbings. It was later published as The Works on Bronze by Ch’en Heng-k’ei. Eighty one of these are ink rubbings of inkwells and twelve of these are ink rubbings of paper weights. The ink rubbing of the pair of paper weights dedicated to T’ang En-p’u is within this set. From this album we learned that bronze paper weights painted by Ch’en Heng-k’ei are few. After a century of turmoils, it is even rarer still. Of the twelve ink rubbings of paper weights, nine are pictorial engravings of prunus, one is a pictorial engraving of bamboo, and one is a pictorial engraving of trees. Of the eighty one ink rubbings of inkwells, there are pictorial engravings of landscapes, flowers and birds, some just have calligraphic engravings on them. Looking through this book, even though this may not be a complete record of the works on bronze by Ch’en Heng-k’ei, it is nonetheless sufficient to demonstrate its essence.

The pair of paper weights dedicated to T’ang En-p’u is not dated. Ch’en Heng-k’ei relocated to Peking around the 1st year of the Republic (1912), and he passed away in the 12th year of the Republic (1923). It was during this period that his bronze works flourished. It is no longer possible to ascertain the year of this work, but it is clear as day the period of this work.

Paper weights are utilitarian objects with a long history. References in books can be traced as far back as the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420-589). In the Fifteenth Chapter of General Biographies, Volume Twenty Five, History of Southern dynasty, there is a paragraph that reads:

“The following evening, Ts’ang-wu (蒼梧) came alone and knocked at the door of the command post. He planned to kill the emperor. The emperor had placed a wooden club and an iron paper weight in the shape of a ju-i of formidable bulk under the desk in the event of danger. They can be used as staffs.”

The emperor mentioned here is Hsiao Tao-ch’eng (蕭道成 427-482), Kao Emperor of the Ch’i Kingdom. The incident of his iron paper weight being used as a defensive weapon occurred over one thousand five hundred and forty years ago. Paper weights mostly come in the forms of animals and rulers. Paper weights in the forms of rulers are particularly popular in the Ming and Ch’ing dynasties, they appear either as singles or pairs. The materials used to make paper weights are diverse, such as jade, stone, ivory, porcelain, crystal, tzu-t’an wood, ebony wood, bronze, etc. However it has always been rare since ancient times to come across paper weights by renowned artists. It is only until late Ch’ing, with the works by Ch’en Yin-sheng (陳寅生), and in the early Republic, with the works by Ch’en Heng-k’ei and Yao Hua, can paper weights by renowned artists be occasionally spotted.

Bronze inkwell by Yao Hua

Ink rubbing of bronze inkwell by Yao Hua

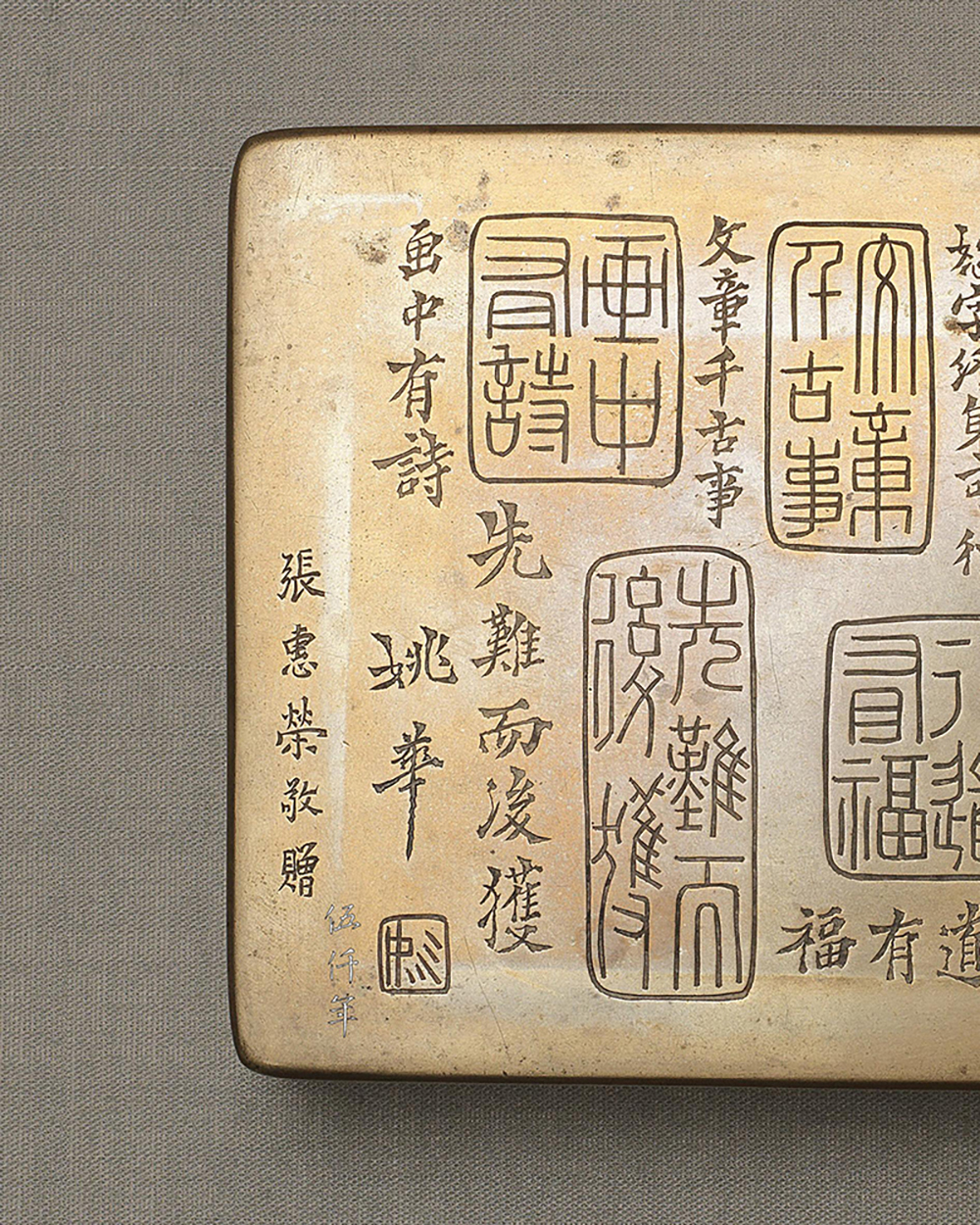

One of the bronze inkwells by Yao Hua in the collection of T’ang En-p’u is 10.9 cm in length, 13.8 cm in width, and 4.1 cm in height. On the lid of the inkwell, there are engravings of seven seal legends. The upper right seal legend in relief reads: “The word forgiveness can be enacted throughout life,” on the left is a line of small characters in regular script to annotate the characters in seal script. The remaining seal legends in intaglio are: “Fraternizing not the illiterate”, “Writings are forever”, “Good fortune along the Tao”, “Poetry in painting”, “Rewards after hardships”. They all have lines of small characters in regular script on the left to annotate the characters in seal script. On the lower left of the lid, the signature Yao Hua was incised. Underneath the signature was incised a small seal legend of the character Yao.

Inkwell is a lifelong companion to be handled day and night. Yao Hua selected those phrases that were regularly seen in seal engravings that relate to writing, painting and self-cultivation. He assembled them onto the inkwell, turning it into an object for reflection. Yao Hua was himself accomplished in seal engraving. At one time he published an anthology of seal impressions with Ch’en Heng-k’ei, titled Collection of Seal Impressions by Ch’en and Yao. After Yao Hua sketched out the seal impressions on the inkwell, he then handed it to well known bronze engravers like Chang Yüeh-ch’en, Chang Shou-ch’eng (張壽承) or Yao Hsi-chiu (姚錫久) for carving.

First detail of bronze inkwell by Yao Hua, with the engraved characters “my older friend T’ien-ju”

Ink rubbing of first detail of bronze inkwell by Yao Hua, with the engraved characters “my older friend T’ien-ju”

Second detail of bronze inkwell by Yao Hua, with the engraved characters “Respectfully presented by Chang Hui-jung”

Ink rubbing of second detail of bronze inkwell by Yao Hua, with the engraved characters “Respectfully presented by Chang Hui-jung”

On the right and left of the lid, there are two additional lines of small engraved characters in regular script:

For the refined amusement of my older friend T’ien-ju.

Respectfully presented by Chang Hui-jung (張惠榮).

Hence we know that this is a gift from Chang.

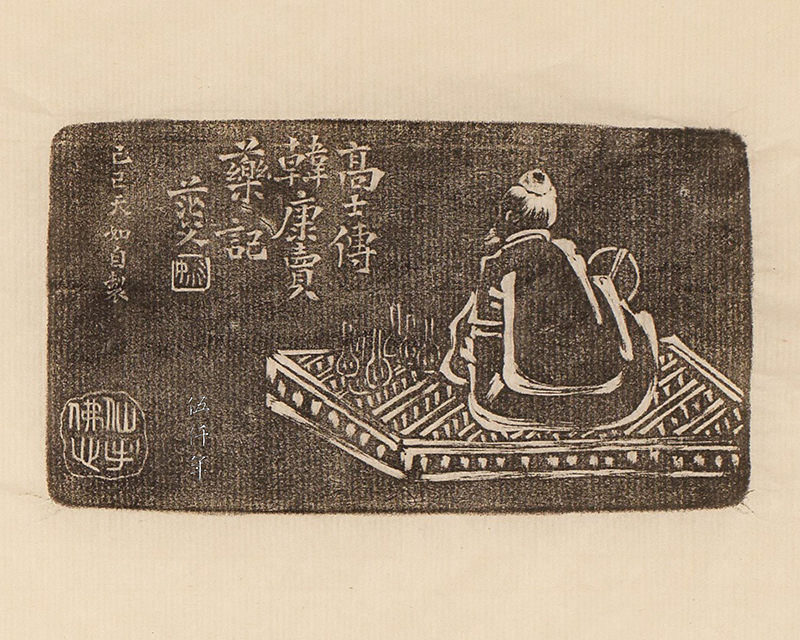

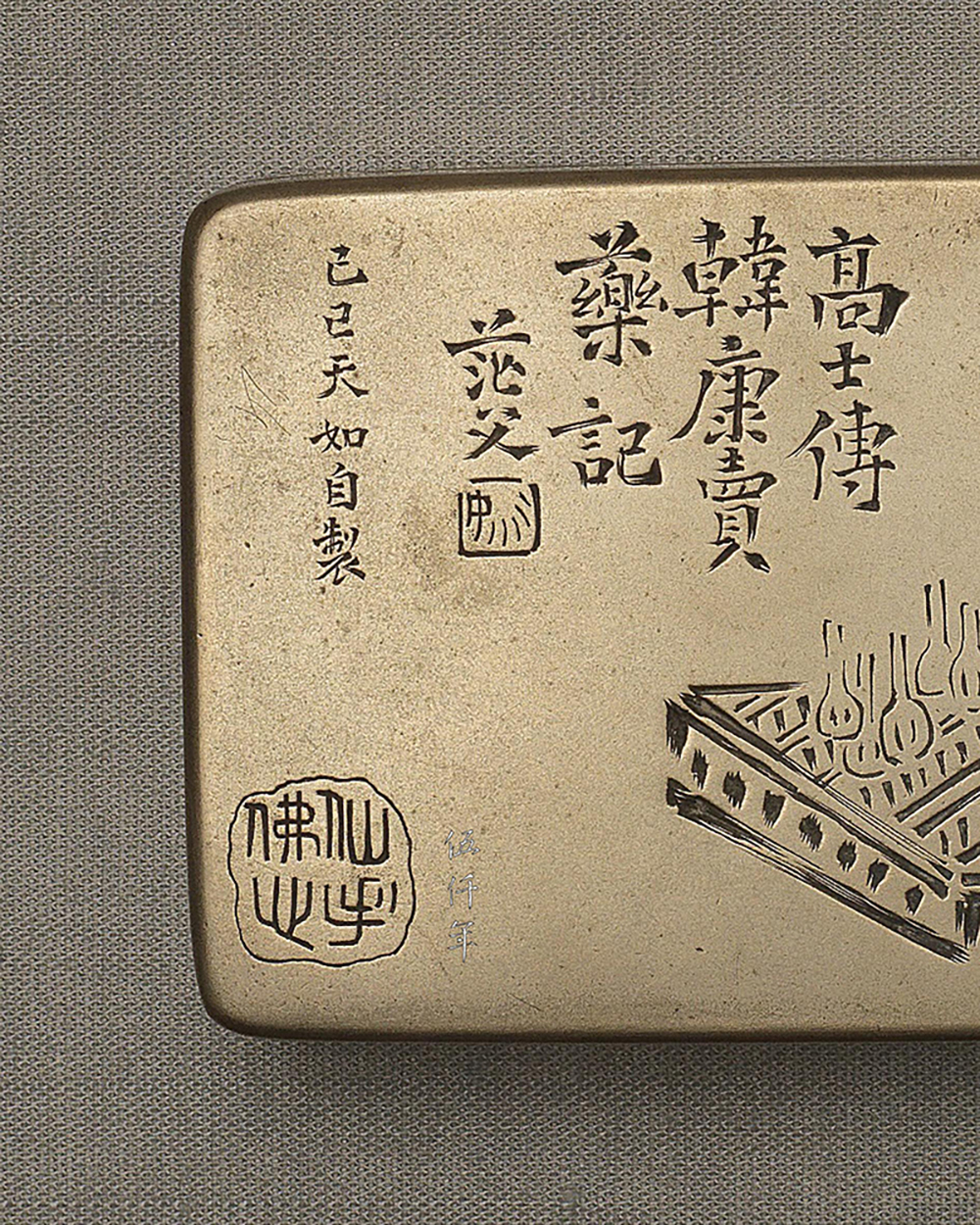

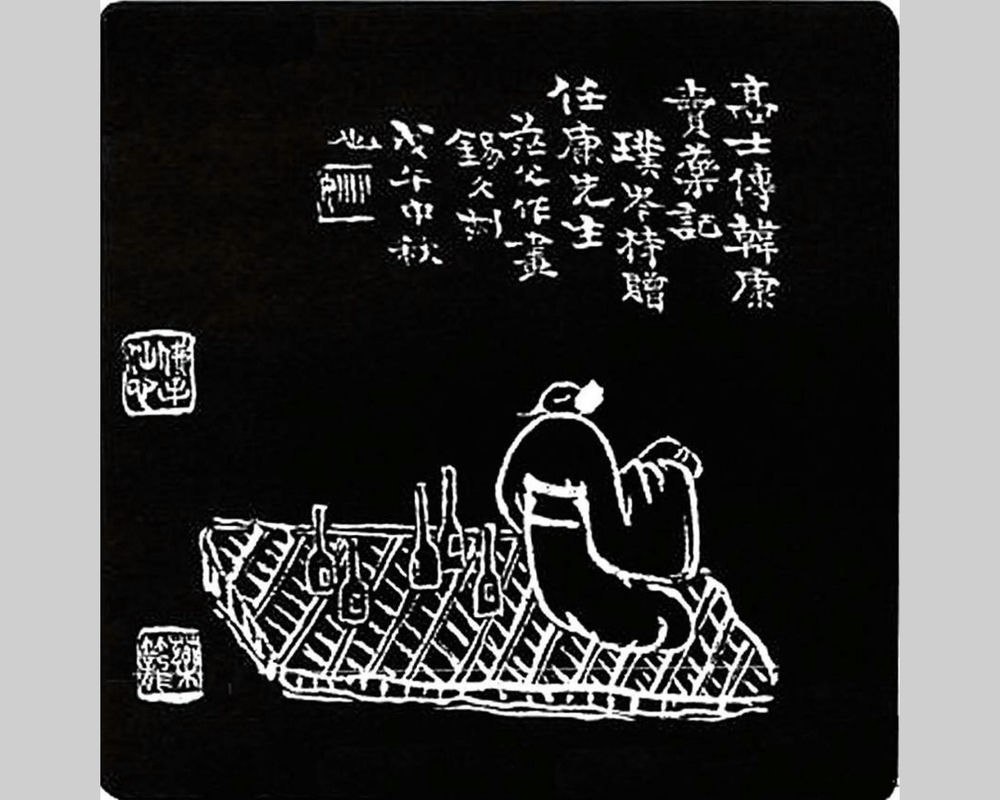

Bronze inkwell by Yao Hua

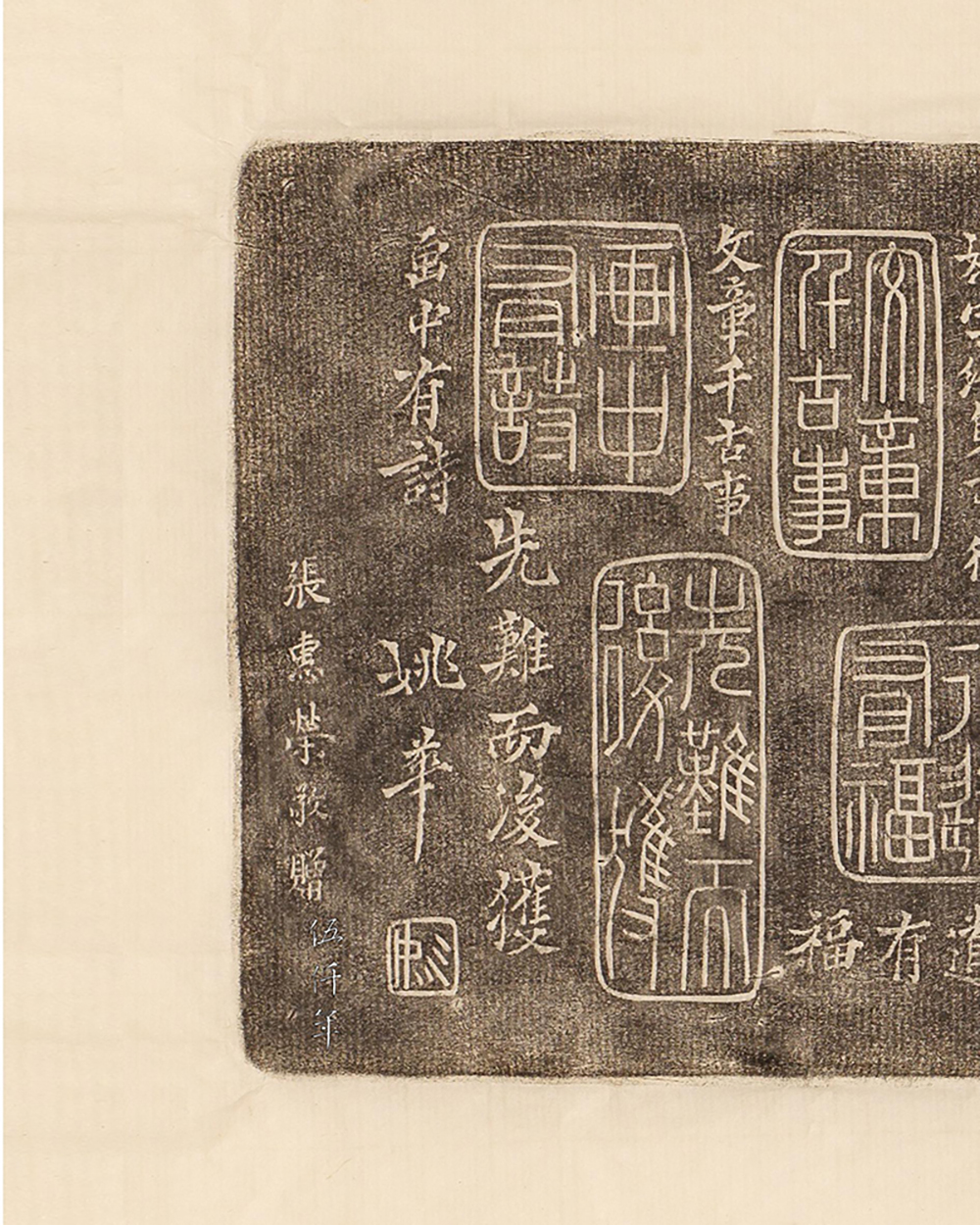

Ink rubbing of bronze inkwell by Yao Hua

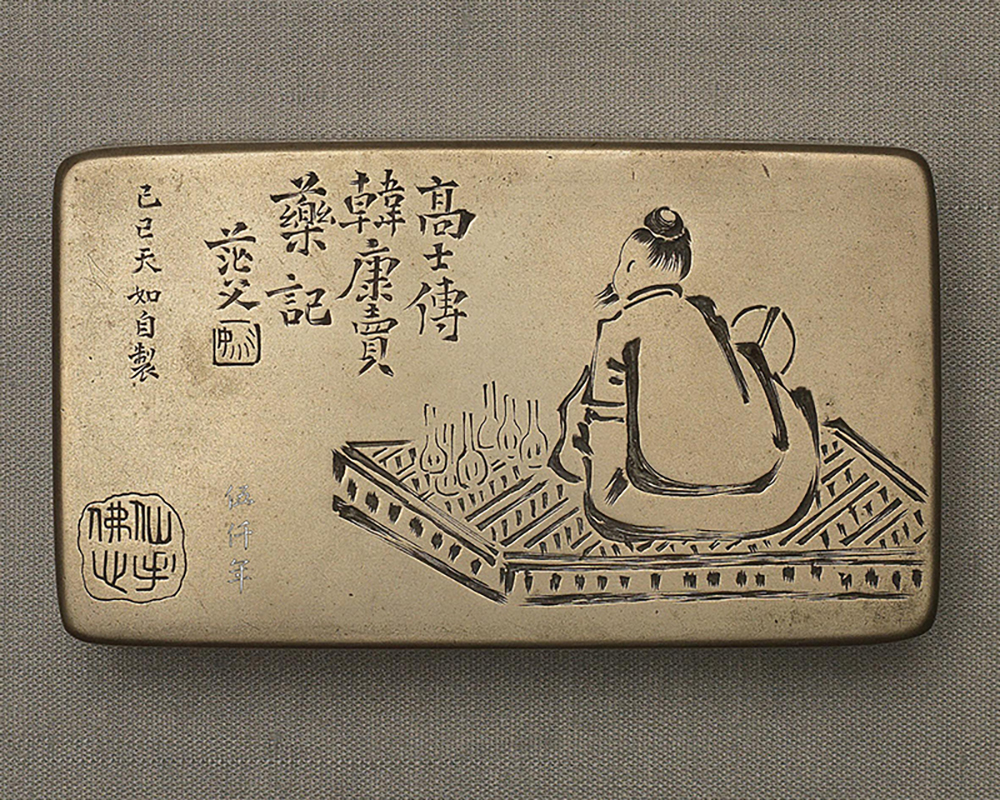

The other bronze inkwell in the collection of T’ang En-p’u is 5.9 cm in length, 10.3 cm in width, and 3.2 cm in height. On the lid is a lofty gentleman sitting on a mattress, with many bottles of medicine by his side. The calligraphy engraving in regular script says:

Biographies of Lofty Gentlemen.

The tale of Han K’ang (韓康) selling medicine.

Mang-fu.

Two seal legends were engraved: “Mang” and “Hand of an immortal, heart of a Buddha”.

There is a line of small engraved characters in regular script:

T’ien-ju made this in chi-ssu year.

Detail of bronze inkwell by Yao Hua, with the engraved characters “T’ien-ju made this in chi-ssu year”

Ink rubbing of detail of bronze inkwell by Yao Hua, with the engraved characters “T’ien-ju made this in chi-ssu year”

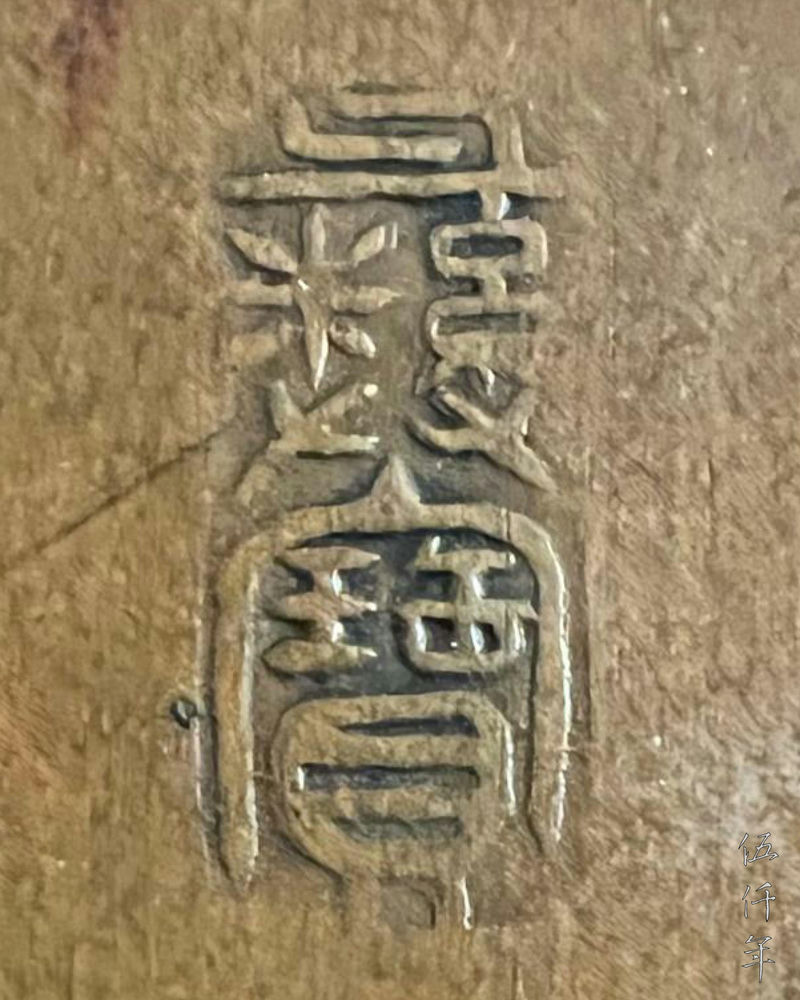

At the base of the inkwell, there is an engraved seal legend : i-pao (彝寶 To be treasured like archaic wine vessel).

The underside of the bronze inkwell by Yao Hua, with the seal legend i-pao (to be treasured like archaic wine vessel)

Ink rubbing of the underside of the bronze inkwell by Yao Hua, with the seal legend i-pao (to be treasured like archaic wine vessel)

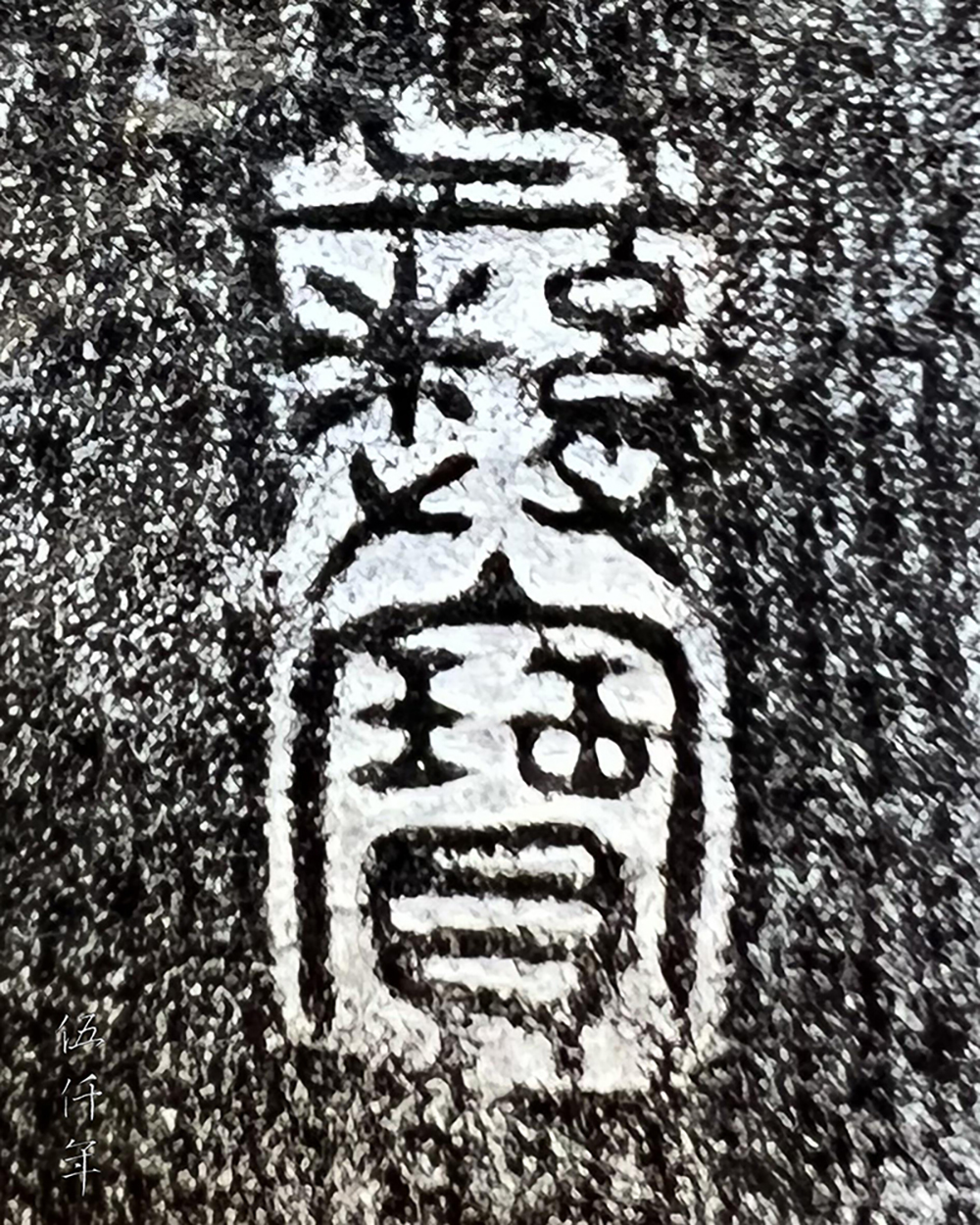

The legend i-pao (to be treasured like archaic wine vessel)

Ink rubbing of the legend i-pao (to be treasured like archaic wine vessel)

This is a desk accoutrement commissioned by T’ang En-p’u for his personal pleasure. Chi-ssu year is the 18th year of the Republic (1929), by then T’ang En-p’u had already retired from politics. It had also been a year since he relocated his family to Hong Kong. Ch’en Heng-k’ei died six years earlier, in the following year, Yao Hua passed away too. Work on bronze in the final years of Yao Hua’s life is rare. One may postulate that the bronze inkwell was sent to Hong Kong from Peking after it was made.

Biographies of Lofty Gentlemen was written by Huang Fu-mi (皇甫謐) of Western Chin dynasty (266-316). In the second volume, there is the biography of Han K’ang:

“Han K’ang, tzu Po-lin (柏林), native of Pa-ling, Ching-chao Capital. He frequently travelled to the well known mountains to procure herbal medicines, he then sold them in the city of Ch’ang-an. For thirty years, he never give any discount. Once, a woman was buying medicine from Han K’ang, she became angry that he was unwilling to budge his price, and said: ‘Are you supposed to be Han K’ang? Never offering a discount?’ Han K’ang sighed: ‘I want to evade fame, and yet an ordinary woman now knows of me, what is the use of medicine?’ Thereafter he sought refuge in the mountains of Pa-ling. Erudites of the Court and provincial graduates consecutively summoned him, but he did not show up………”

Although Han K’ang was an eminent doctor, his ambition was to be a recluse in the mountains. T’ang En-p’u was also a celebrated doctor, contemporary writers like Kao Pai-shih (高拜石) and Kao Po-yü (高伯雨) had chronicled this in great detail. When he retired to Hong Kong, living in the far corner of the sea, was he not a kindred spirit from another era? A lofty gentleman of our time? For T’ang En-p’u to request Yao Hua to paint the tale of Han K’ang selling medicine on an inkwell, we could discern that his thoughts were carried away by a far away episode in history.

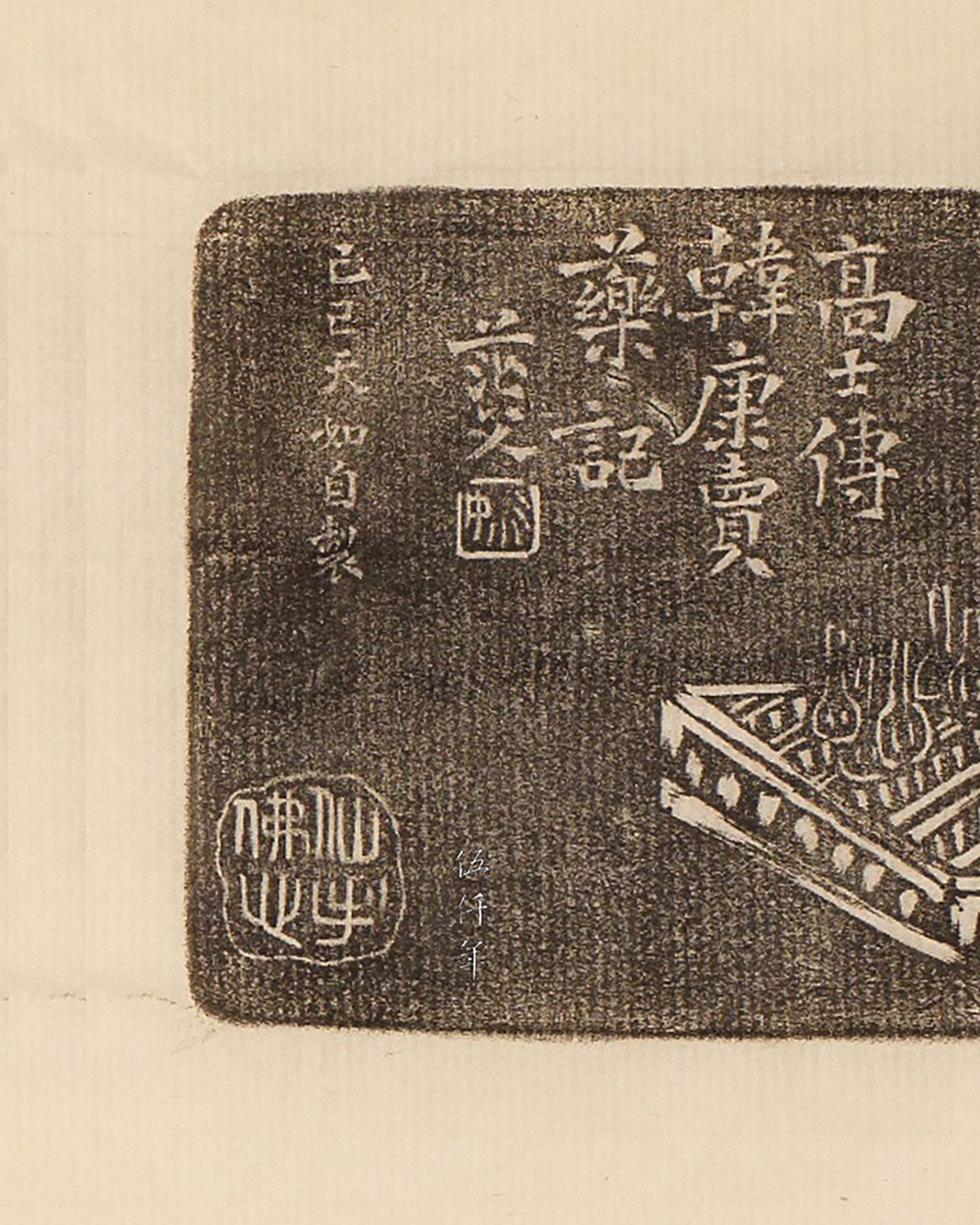

Ink rubbing of bronze inkwell by Yao Hua

There is an early precedent for Yao Hua to paint the tale of Han K’ang selling medicine on an inkwell. I have seen an ink rubbing of a square inkwell with similar image. The few lines of engraved calligraphy are:

Biographies of Lofty Gentlemen.

The tale of Han K’ang selling medicine.

P’u-ts’en (璞岑) presented this to Mr. Jen-k’ang (任康). Painted by Mang-fu and engraved by Hsi-chiu.

The Autumn Festival in wu-wu year.

Three seal legends were engraved on the lid: “Yao”, “Hand of a Buddha, heart of an immortal” and “Belonging of a medicine container”.

It is obvious that Jen-k’ang was a medical doctor. Since this inkwell was engraved by Yao Hsi-chiu, it would not be far stretched to speculate that the inkwell of T’ang En-p’u could also be engraved by Yao. Wu-wu year is the 7th year of the Republic (1918), the two inkwells were made across a span of eleven years.

The accoutrement of inkwell only appeared in the late Ch’ing and flourished in the early Republic. At that time, trains and automobiles were introduced across the country. Traveling to different cities and provinces was no longer an arduous task. Yet, preparing the ink, wielding the brush, should not be constrained by modernity. However, placing an inkstone in the luggage can be burdensome, bronze inkwell on the contrary is light and agile. Engraved inkwells with calligraphy and paintings by distinguished artists are alluring and seductive. Indeed inkwells are fine companions for travelers of the four seas. According to a paragraph in Volume Five of the Miscellaneous Records of Antiques (骨董瑣記) by Teng Chih-ch’eng (鄧之誠):

“It is not clear when inkwell was first made. As per legend, a scholar was about to take the imperial examination, his wife considered the inkstone to be quite cumbersome, so instead she used her box for rouge to hold his ink. It is an alluring tale, however there is no concrete evidence to support this. Inkwell was probably first made around the Chia-ch’ing and Tao-kuang reigns. In ping-wu year of the Tao-kuang reign, Juan Wen-ta (阮文達) celebrated his 60th anniversary of attaining the chü-jen degree by using the twenty taels of silver he was awarded by the provincial government when he first qualified as a chü-jen to make an inkwell. It was made to a perfect round shape, with a lid on top, and two columns on the side attached to a chain. In the early years of the Kuang-hsü reign, this inkwell was still kept in his house. Among the shops in the capital which specialized in inkwells, Wan-li Chai (萬禮齋) is regarded as a pioneer. Ch’en Yin-sheng (陳寅生), a hsiu-ts’ai (秀才 cultivated talent), started the fashion of engraving calligraphy on inkwells. His original name was Lin-ping (麟炳), he was accomplished in medicine, calligraphy and painting. He would write the calligraphy on bronze and then engraved it himself. This is the reason his works can advance into the realm of ingenuity. This was in the first year of the T’ung-chih reign.”

Portrait of Ch’en Yin-sheng hsiu-ts’ai

Juan Wen-ta invented the inkwell in ping-wu year of the Tao-kuang reign, the equivalent of the 26th year of the Tao-kuang reign, 1846. Juan Wen-ta (1764-1849), original name Yüan (元), tzu Po-yüan (伯元), hao Yün-t’ai (芸臺), Yen-ching Lao-jen (揅經老人). He was awarded the posthumous name of Wen-ta (文達) and was a native of I-cheng, Kiangsu Province. He attained the chin-shih degree in the 54th year of the Ch’ien-lung reign, and was appointed in succession provincial governor of Chekiang Province, governor-general of Hupeh and Hunan Provinces and governor-general of Yunnan and Kweichow Provinces. He wrote extensively and was a celebrated scholar of the Classics.

Portrait of Juan Wen-ta

After a hundred years, one may not be able to find another vista of a group of works on bronze by eminent artists dedicated to one person, such as this group which includes a pair of paper weights by Ch’en Heng-k’ei and two inkwells by Yao Hua, all dedicated to T’ang En-p’u. As T’ang En-p’u had sought refuge in Hong Kong, his treasured art works managed to circumvent the great destruction unleashed by the Cultural Revolution in mainland China. The splendour of those early Republican years can thus be passed on, to inspire those who will follow and rise.

The pair of bronze paper weights by Ch’en Heng-k’ei and the two bronze inkwells by Yao Hua