Since the beginning of history, humans have used the pretexts of race, skin colour, religion and culture to kill each other with pure hatred. Such instances are too innumerable to cite. As far as Overseas Chinese is concerned, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 in the United States is the most obvious example of discrimination by Caucasians. However many Asian countries have not been any more cordial. In May 1969, there was the Anti-Chinese Incident in Malaysia, and in May 1998, there was the Anti-Chinese Riots in Indonesia, the latter entailed the raping and killing of thousands of Chinese. Contemplating the present and harking back to the past, we hereby display an English letter by Wu Ting-fang, Minister Plenipotentiary to the United States, condemning the Chinese Exclusion Act. This can be an admonition for today.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

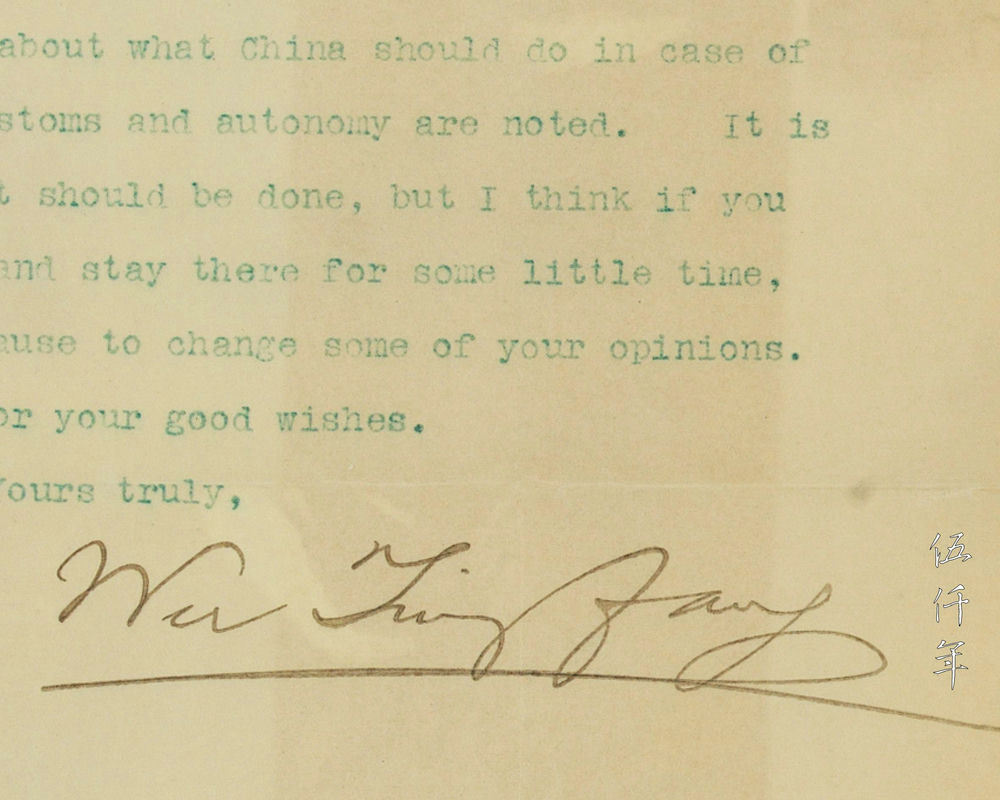

Detail of English letter by Wu Ting-fang

Most Chinese are not aware that on 6 October 2011, the United States Senate passed a resolution sponsored by Senator Scott Brown expressing the regret of the Senate for the passage of discriminatory laws against the Chinese in America, including the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (Senate Resolution 201). Subsequently on 18 June 2012, the United States House of Representatives passed the resolution expressing the regret of the House of Representatives for the passage of laws that adversely affected the Chinese in the United States, including the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (House Resolution 683). This resolution was initiated by Representative Judy Chu, the first Chinese-American woman elected to Congress. The full title is Resolution of Regret for Chinese Exclusion Act.

Congresswoman Judy Chu discusses Resolution of Regret for Chinese Exclusion Act at press conference. Photograph courtesy Larry Shinagawa

The enactment of the Chinese Exclusion Act took place one hundred and forty one years ago. It was followed by three subsequent extensions, spanning a staggering sixty one years until its eventual termination in 1943. This period corresponded to the 8th year of the Kuang-hsü reign to the 32nd year of the Republic of China. For over sixty years, Chinese people endured racial discrimination and unrelenting humiliation. The Resolutions of Regret for the Chinese Exclusion Act finally brought some redress; they are of significance not just for the overseas Chinese community but also of great importance to all Chinese.

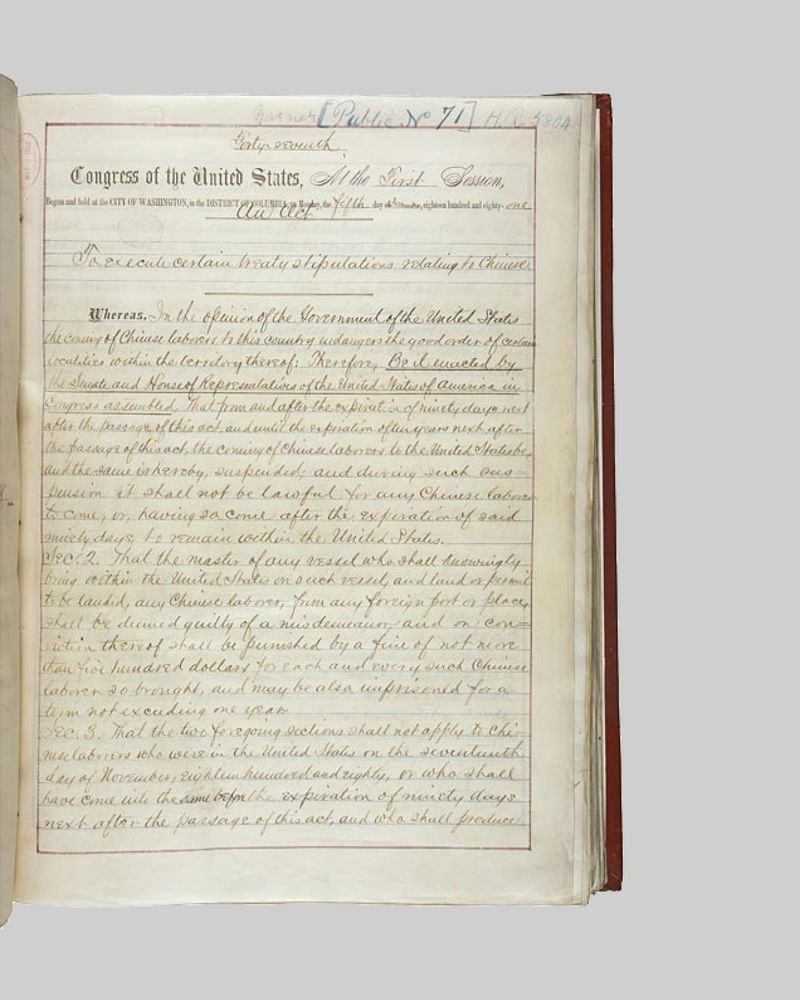

Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

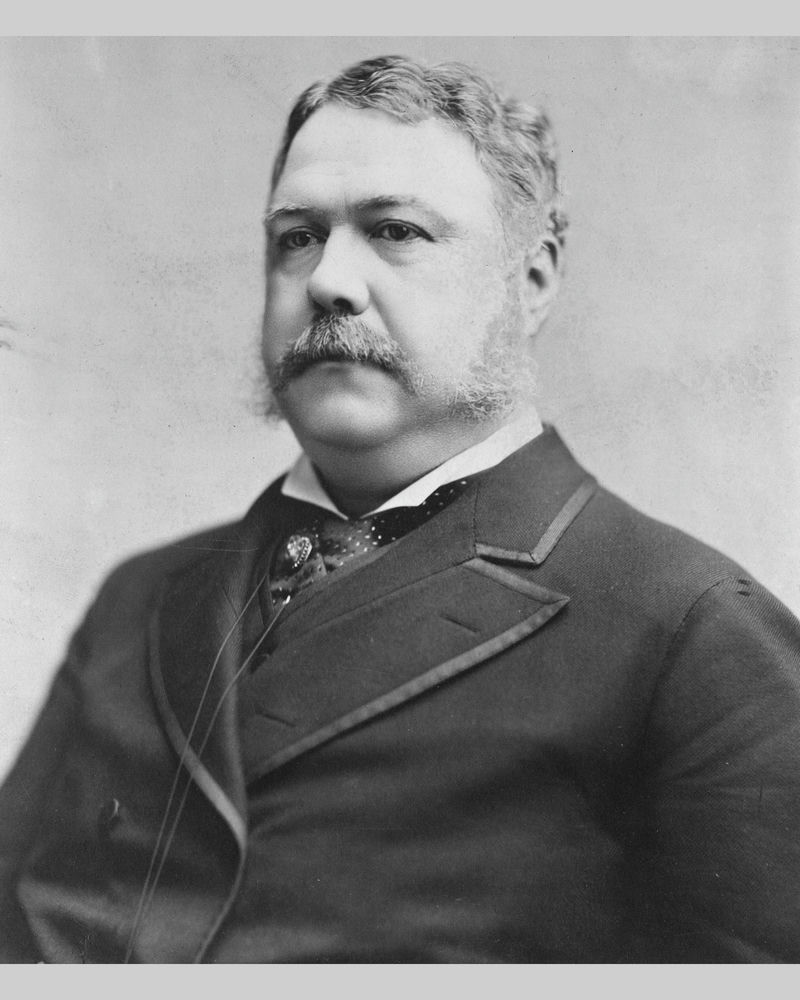

Portrait of President Chester A. Arthur

On 6 May 1882, the United States passed the Chinese Exclusion Act through Congress, which was then signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur. The legislation banned Chinese labourers from immigrating to the United States for a period of ten years. This act marked the first time in U.S. history that immigration was prohibited based on racial grounds. The definition of “labourers” included both skilled and unskilled workers, effectively preventing the vast majority of Chinese labourers from entering the country, except for a few individuals with other status. The Act also introduced new regulations for Chinese labourers already residing in the United States, requiring them to obtain additional permits if they wished to return after leaving. Naturalization as U.S. citizens was strictly prohibited, and the courts were empowered to deport Chinese labourers who were found to be staying in the country unlawfully.

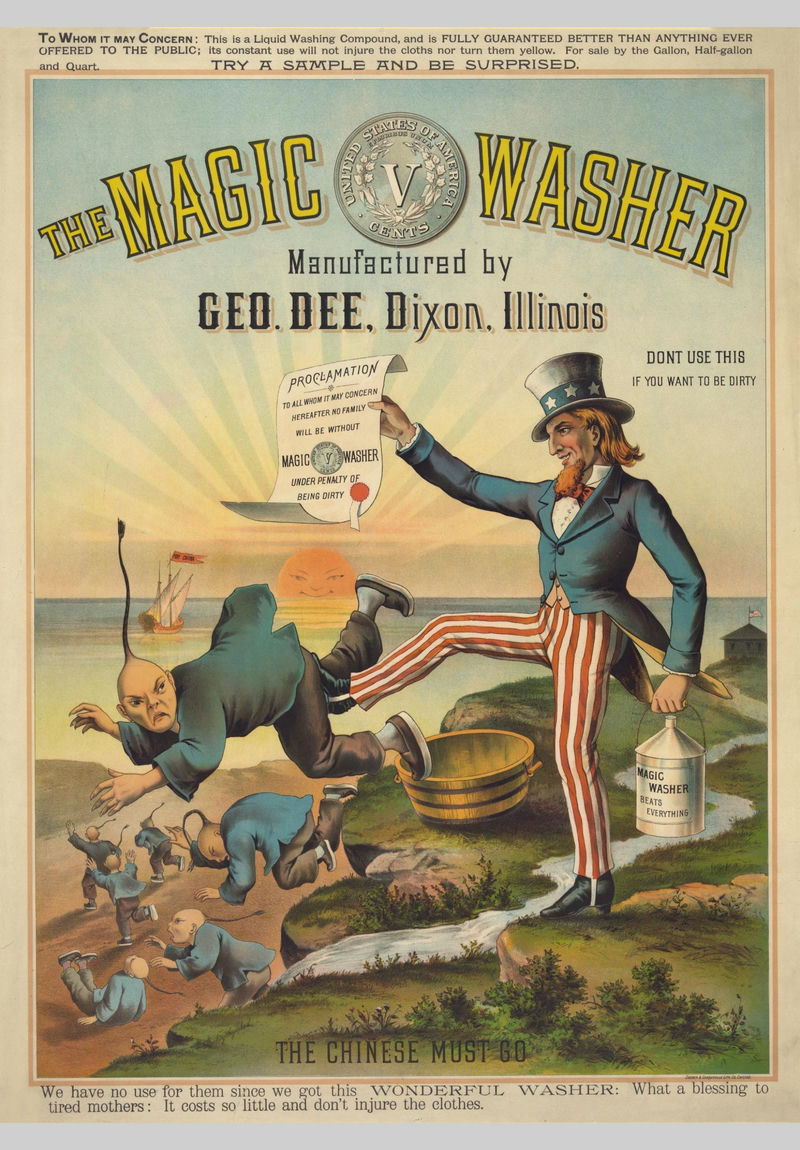

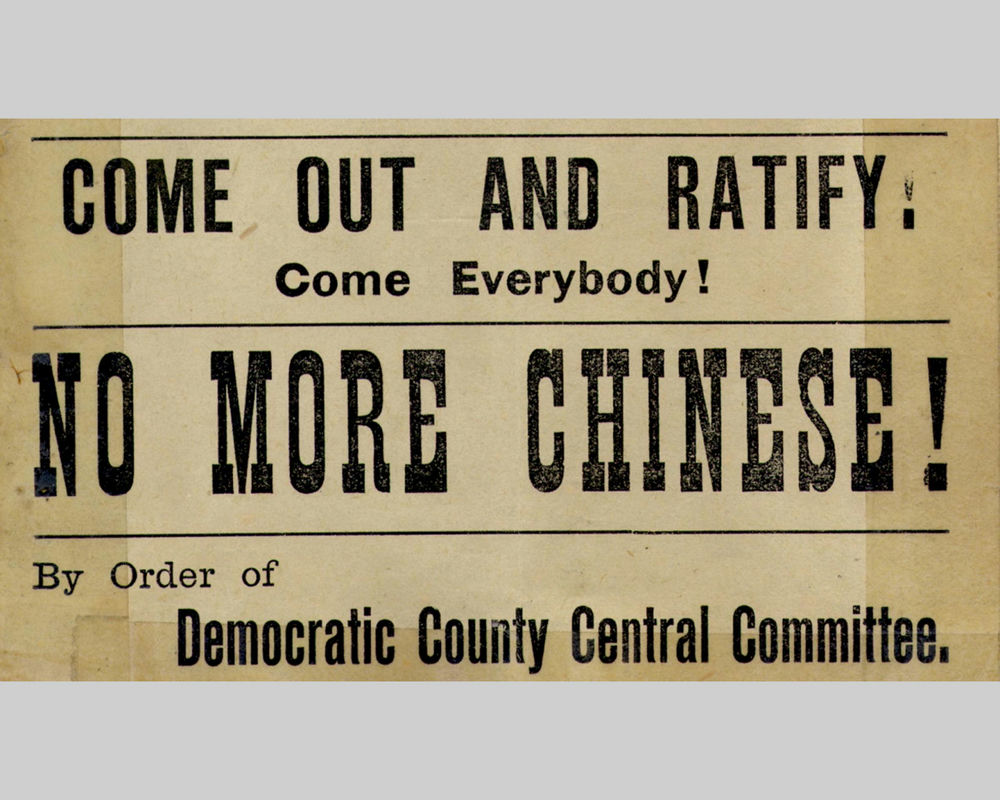

Anti-Chinese poster of 1886

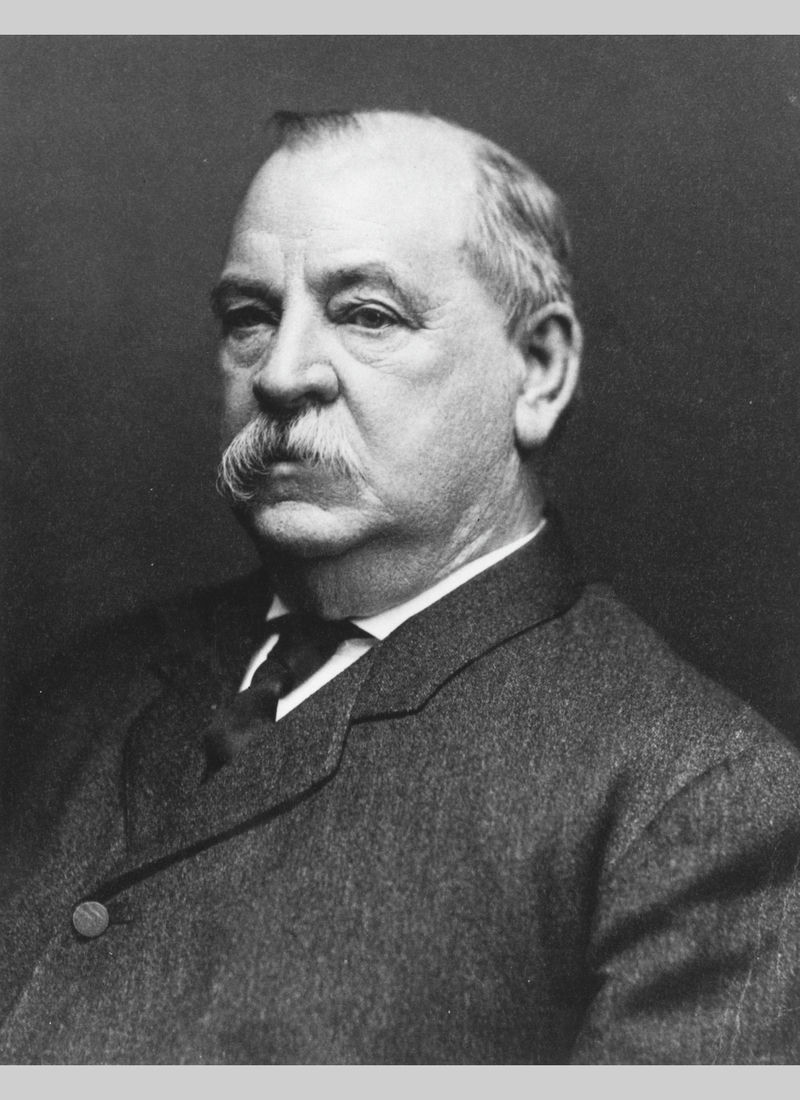

Portrait of President Stephen Grover Cleveland

Six years later, on 1 October 1888, President Stephen Grover Cleveland of the United States signed the Scott Act, which prohibited Chinese labourers who had left the United States from returning, effectively barring an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 Chinese labourers from returning to their homes in America.

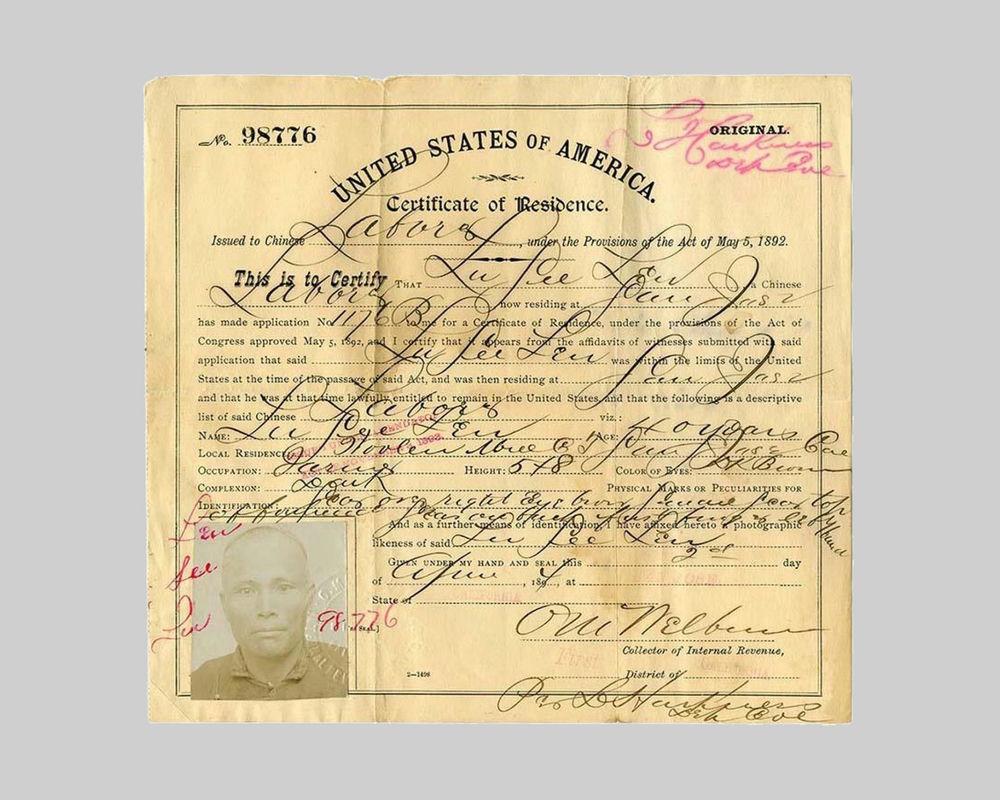

A copy of the Certificate of Residence issued in 1894

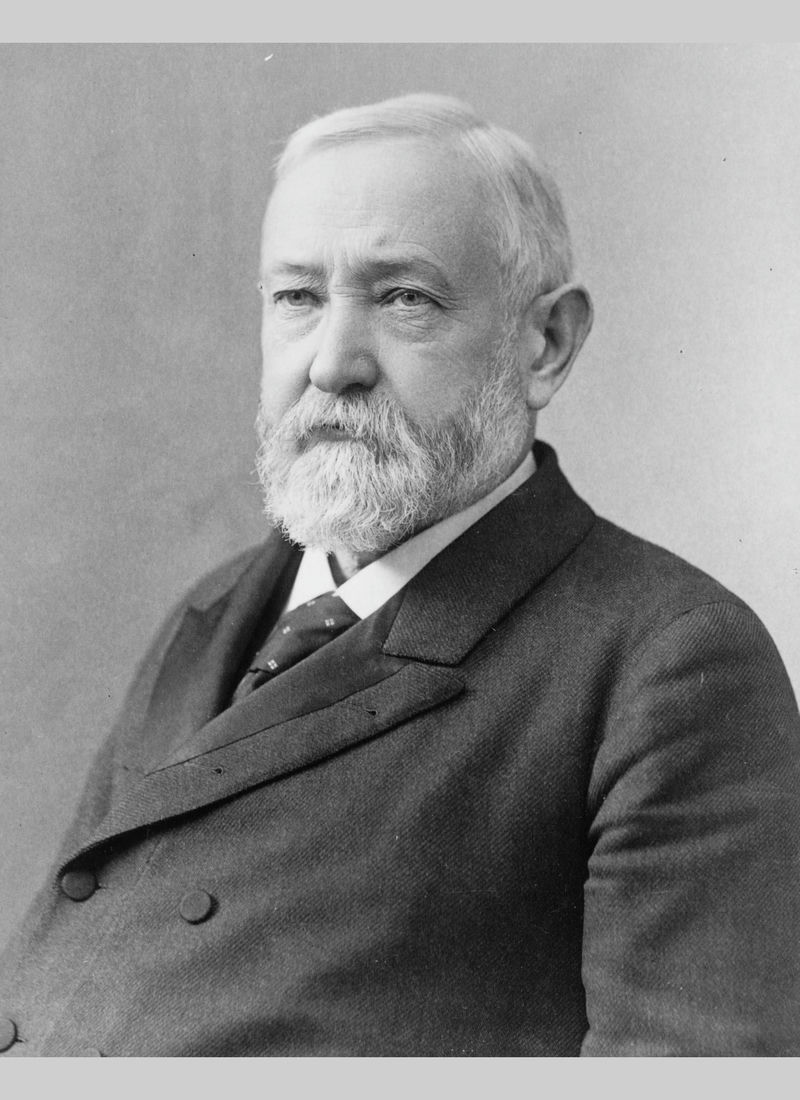

Portrait of President Benjamin Harrison

Four years later, on 5 May 1892, the day before the expiration of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, President Benjamin Harrison of the United States signed the Geary Act, extending the exclusionary measures for another ten years. The Geary Act required Chinese labourers residing in the United States to carry certificates of residence at all times. Those found without proper documentation were subject to arrest, one year of hard labour, and subsequent deportation.

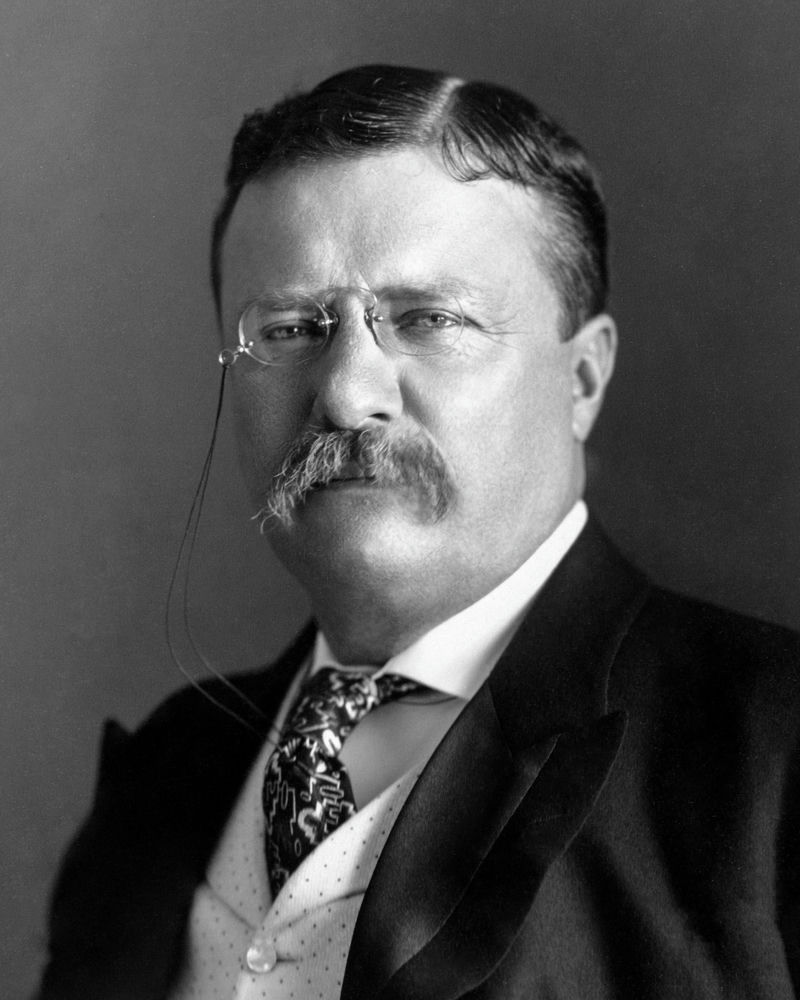

Portrait of President Theodore Roosevelt Jr.

Another ten years passed, and on 29 April 1902, seven days before the expiration of the Geary Act of 1892, President Theodore Roosevelt Jr. of the United States once again signed the extension of the Chinese Exclusion Act, covering Chinese labourers in Hawaii and the Philippines as well.

Two years later, in 1904, the United States Congress passed a resolution to indefinitely extend the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Based on the above, it is evident that the Chinese Exclusion Act would only come to an end due to a momentous change of circumstance.

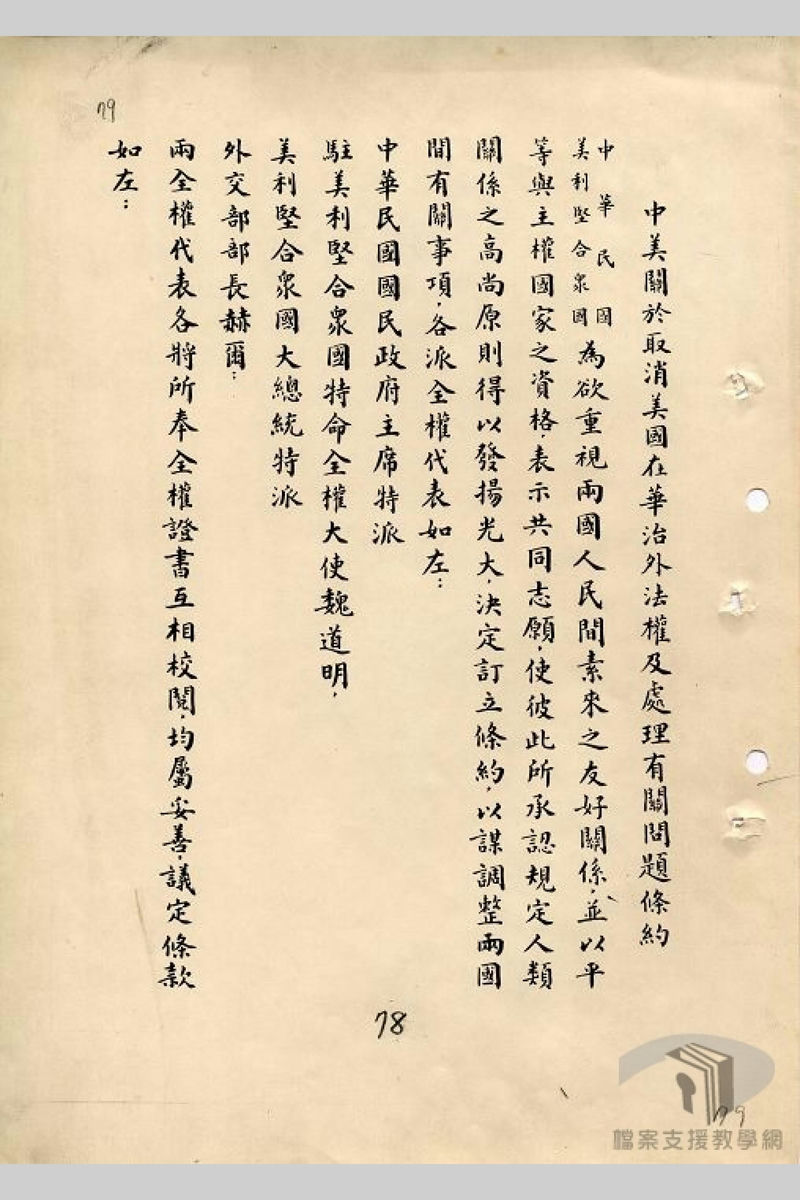

A leaf of the Treaty between the United States and China for Relinquishment of Extraterritorial Rights in China and the Regulation of Related Matters

On 7 July in the 26th year of the Republic (1937), the Marco Polo Bridge Incident occurred, marking the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. Under the leadership of President Chiang Kai-shek, the people of China rallied to resist Japanese aggression. In the fourth year of the war of resistance, on 7 December in the 30th year of the Republic (1941), Japan launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, prompting the United States to declare war on Japan the following day. The Republic of China and the United States thus became allies. Being allies, on 11 January 1943, the Republic of China and the United States signed the Treaty between the United States and China for Relinquishment of Extraterritorial Rights in China and the Regulation of Related Matters, also known as the Sino-American New Equal Treaty. China then proceeded to abolish the unequal treaties imposed by other countries during the Ch’ing dynasty. On 17 December of the same year, the United States Congress passed the Repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act, also known as the Magnuson Act. Although the United States allowed Chinese nationals to immigrate, the annual quota was limited to one hundred and five individuals. Chinese nationals born outside the United States were permitted to apply for U.S. citizenship.

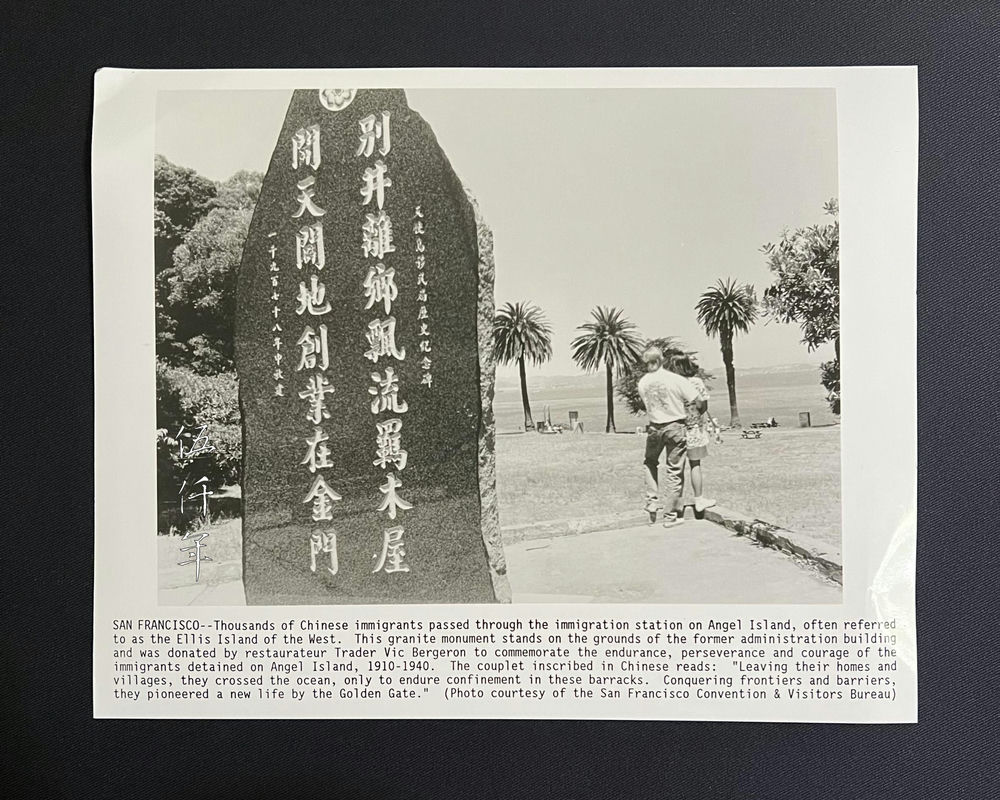

Granite monument in San Francisco commemorating the Chinese immigrants who passed through the immigration station on Angel Island

From 6 May 1882, when the United States passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, to 17 December 1943, when the United States passed the Repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act, a total of sixty one years had passed. In the past, Chinese people ventured across the ocean to seek a livelihood, facing extraordinary cruelty and hardships as they were forced by their difficult circumstances. Today the United States has long opened its doors to immigration, yet the wave of Chinese people emigrating from mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan shows no sign of abating! It gives rise to the thought that if one day mainland China should achieve a state where civil rights and livelihoods are secured for its people, would millions of our compatriots still be willing to exhaust all efforts in order to emigrate to foreign lands?

During the sixty one years of racial discrimination against the Chinese in the United States, there were some Chinese individuals along with foreigners who strongly criticized the Chinese Exclusion Act, and used their writings and voices to advocate for justice. The voice of righteousness was not completely silenced during that time.

Portrait of Minister Plenipotentiary Wu Ting-fang

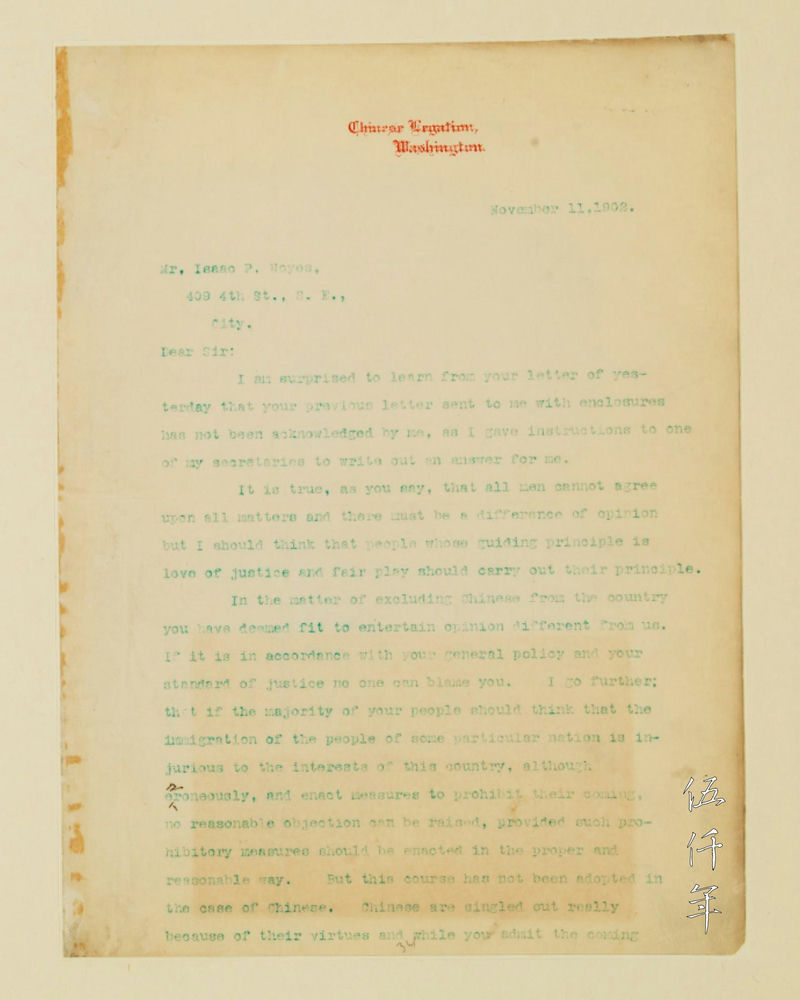

I have in my collection a precious letter from the Minister Plenipotentiary to the United States, Wu Ting-fang, addressed to the American anti-Chinese writer Isaac Pitman Noyes, expressing his strong condemnation. It is indeed a letter to be treasured. Wu Ting-fang was a renowned diplomat, his speeches and writings were greatly acclaimed in the United States during his time. This letter was written on 11 November in the 28th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1902). Seven months earlier, on 29 April, President Theodore Roosevelt had just signed the extension of the Chinese Exclusion Act for another ten years. In this letter, Wu Ting-fang's indignation regarding the Chinese exclusion issue is evident.

First page of English letter by Wu Ting-fang

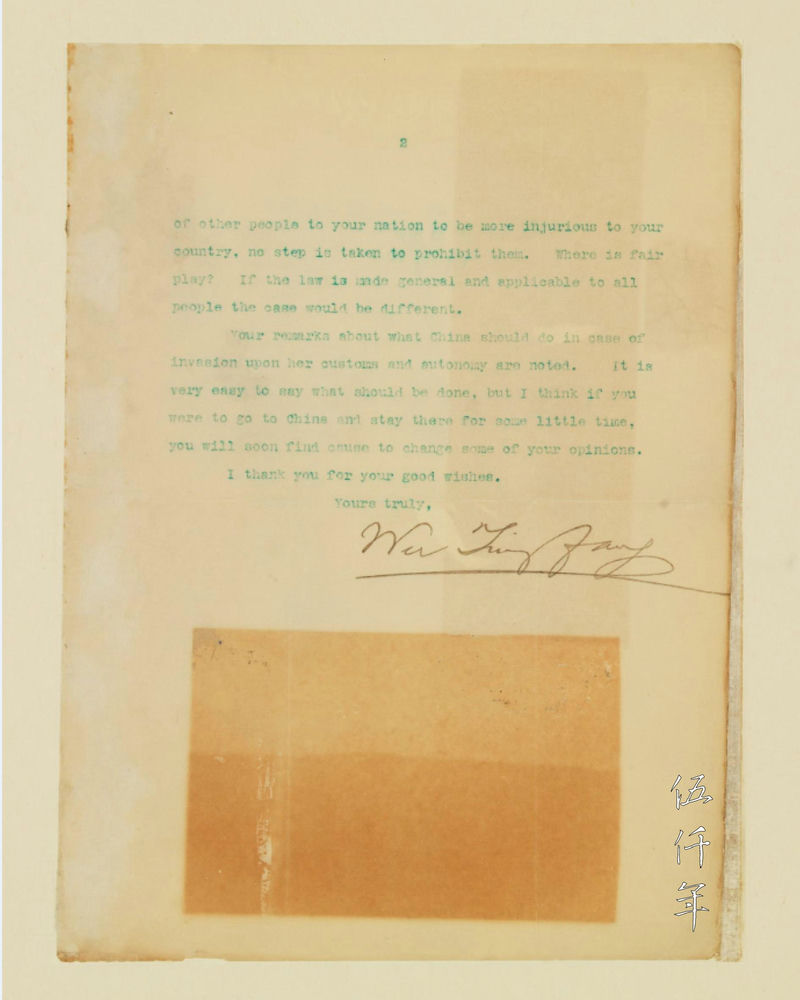

Second page of English letter by Wu Ting-fang

The letter reads as follows:

“November 11, 1902.

Mr. Isaac P. Noyes,

409 4th St., S.E.,

City.

Dear Sir:

I am surprised to learn from your letter of yesterday that your previous letter sent to me with enclosures has not been acknowledged by me, as I gave instructions to one of my secretaries to write out an answer for me.

It is true, as you say, that all men cannot agree upon all matters and there must be a difference of opinion but I should think that people whose guiding principle is love of justice and fair play should carry out their principle.

In the matter of excluding Chinese from the country you have deemed fit to entertain opinion different from us. If it is in accordance with your general policy and your standard of justice no one can blame you. I go further; that if the majority of your people should think that the immigration of the people of some particular nation is injurious to the interests of this country, although erroneously, and enact measures to prohibit their coming, no reasonable objection can be raised, provided such prohibitory measures should be enacted in the proper and reasonable way. But this course has not been adopted in the case of Chinese. Chinese are singled out really because of their virtues and while you admit the coming of other people to your nation to be more injurious to your country, no step is taken to prohibit them. Where is fair play? If the law is made general and applicable to all people the case would be different.

Your remarks about what China should do in case of invasion upon her customs and autonomy are noted. It is very easy to say what should be done, but I think if you were to go to China and stay there for some little time, you will soon find cause to change some of your opinions.

I thank you for your good wishes.

Yours truly,

Wu Ting-fang”

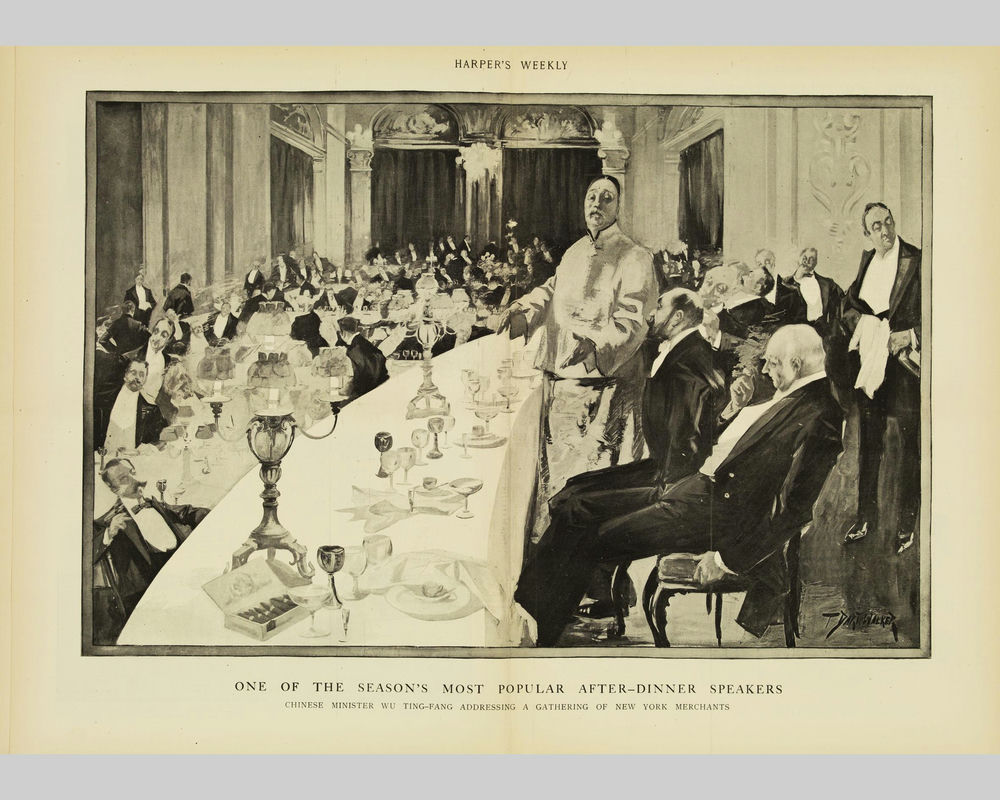

Illustration of Wu Ting-fang addressing a gathering of New York merchants in Harper’s Weekly on 9 June 1900

Wu Ting-fang (伍廷芳 1842-1922), tzu Wen Chüeh (文爵), hao Chih-yung (秩庸), was a native of Hsin-hui, Kwangtung Province. He was born in Singapore but returned to China at the age of four. In the 11th year of the Hsien-feng reign (1861), he graduated from St. Paul's College in Hong Kong. He founded with friends the newspaper Chung-wai Hsin-pao (中外新報). In the 13th year of the T'ung-chih reign (1874), he went to study in the United Kingdom and entered Lincoln's Inn to study law. After three years, he graduated and returned to Hong Kong, where he worked as a lawyer, judge, and legislator.

In the 8th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1882), Li Hung-chang (李鴻章) heard of him and invited him to join his office. In the 22nd year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1896), he served as minister plenipotentiary to the United States, Spain, and Peru. In the 28th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1902), he returned to China and served as minister of legal reform, whereby he abolished the punishment of slicing, collective punishment, and forced confessions in the Ch’ing dynasty legal code, ushering in a new era of criminal law.

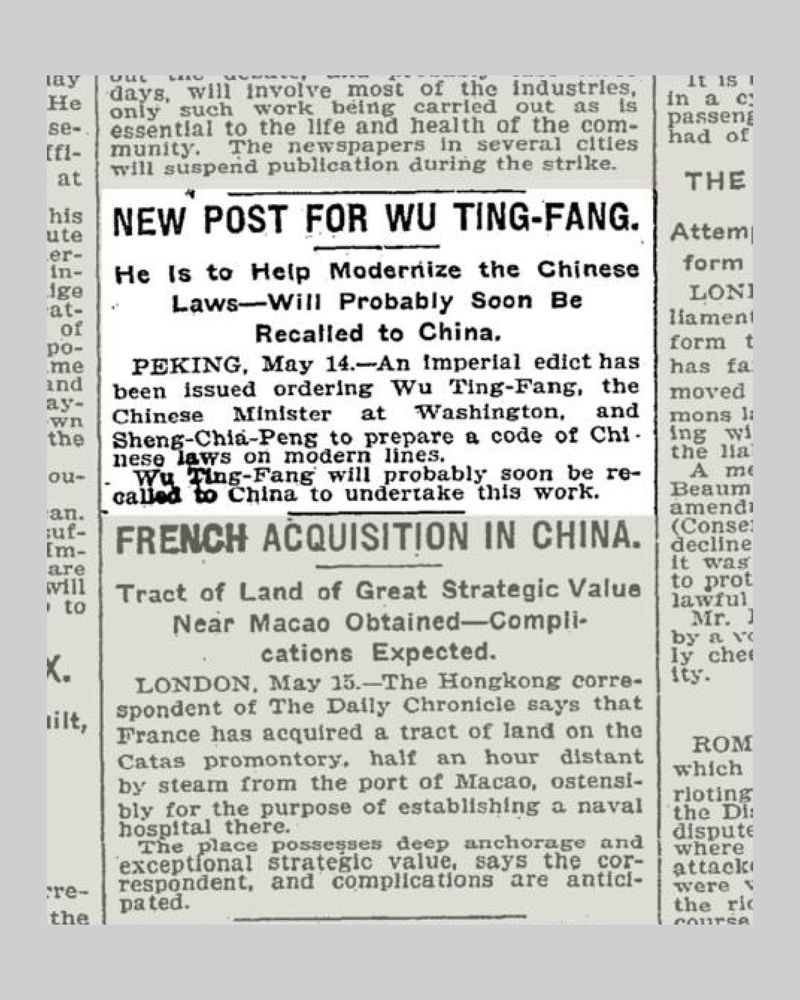

News of Wu Ting-fang to return to China in The New York Times on 15 May 1902

He also served as minister of commerce and the right vice-deputy minister of the Foreign Office. In the 33rd year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1907), he served again as minister plenipotentiary to the United States, Mexico, Peru, and Cuba. In October in the 3rd year of the Hsüan-tung reign (1911), the Wuchang Uprising took place, and he supported the republican system. In the 1st year of the Republic of China (1912), he became the minister of justice in the Provisional Government. In April of the same year, he was appointed as the chief minister to the United States, but he did not take up the position. In the 5th year of the Republic of China (1916), he served as the minister of foreign affairs in the Northern government. In the 7th year of the Republic, he became the minister of foreign affairs in the Southern government of Kwangtung. In the 11th year of the Republic (1922), he was appointed governor of Kwangtung Province by Sun Yat-sen, the founding father of the Republic. He wrote America through the Spectacles of an Oriental Diplomat and other works.

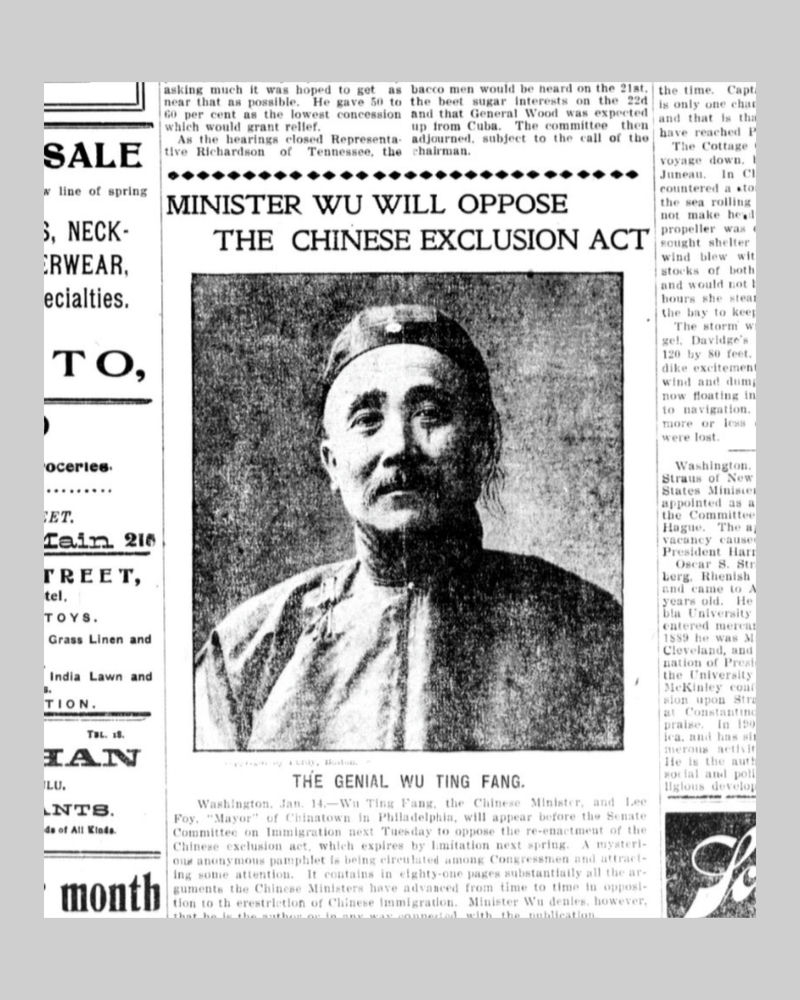

News of Wu Ting-fang opposing the Chinese Exclusion Act in the Evening Bulletin of Honolulu on 22 January 1902

The recipient, Isaac Pitman Noyes (1840-1910), was born in New York and graduated from the school of architecture of Brown University. From 1870 to 1908, he served in the office of the Surgeon General of the United States. His works include Suggestions for Constructing Fire-Proof Buildings, The Army Medical School, The Peruvian Mummy and others.

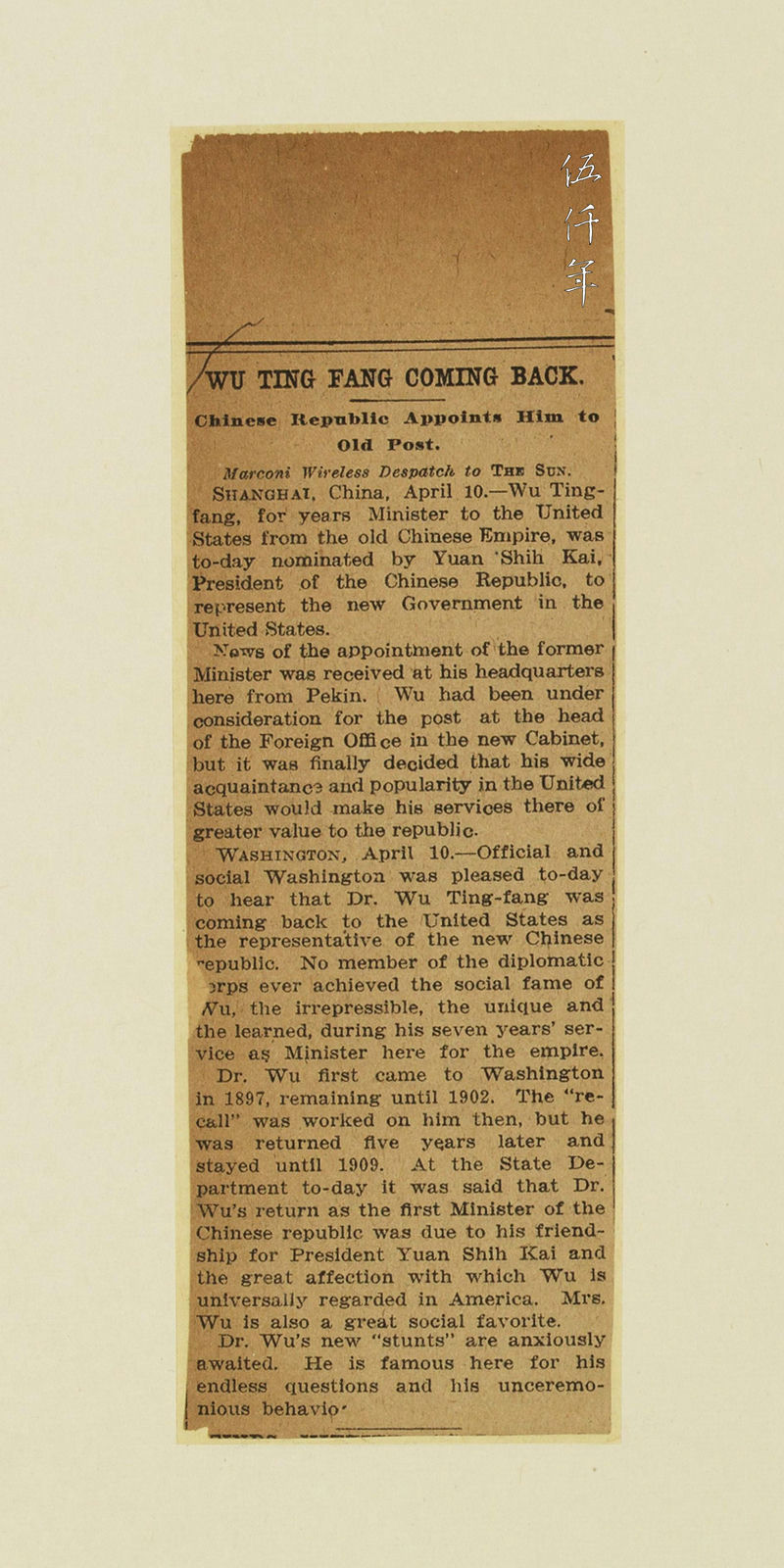

News of Wu Ting-fang to return to America as representative of the Republic of China in a newspaper on 10 April 1912

News of Wu Ting-fang to return to America as representative of the Republic of China in a newspaper on 10 April 1912

I have a newspaper clipping dated 10 April 1912 from an American newspaper, regarding the appointment of Wu Ting-fang as minister plenipotentiary to the United States by the provisional president Yuan Shi-kai (袁世凱). Wu Ting-fang, being a British barrister, was skilled in oratory and knowledgeable in both Chinese and Western cultures. He was highly regarded in Western diplomatic circles. Reading this news clipping gives an indication of his distinguished reputation. Although Wu Ting-fang was appointed to serve in the United States, he did not take up the position. The text of the newspaper article reads:

“WU TING FANG COMING BACK.

Chinese Republic Appoints Him to

Old Post.

Shanghai, China, April 10. Wu Ting-

fang, for years Minister to the United

States from the old Chinese Empire, was

to-day nominated by Yuan Shih Kai,

President of the Chinese Republic, to

represent the new government in the

United States....

News of the appointment of the former

Minister was received at his headquarters

here from Pekin. Wu had been under

consideration for the post at the head

of the Foreign Office in the New Cabinet,

but it was finally decided that his wide

acquaintance and popularity in the United

States would make his services there of

greater value to the republic.

Washington, April 10. Official and

social Washington was pleased to-day

to hear that Dr. Wu Ting-fang was

coming back to the United States as

the representative of the new Chinese

republic. No member of the diplomatic

corps ever achieved the social fame of

Wu, the irrepressible, the unique and

the learned, during his seven years’ ser-

vice as Minister here for the empire.

Dr. Wu first came to Washington

in 1897, remaining until 1902. The “re-

call” was worked on him then, but he

was returned five years later and

stayed until 1909. At the State De-

partment to-day it was said that Dr.

Wu’s return as the first Minister of the

Chinese republic was due to his friend-

ship for President Yuan Shih Kai and

the great affection with which Wu is

universally regarded in America. Mrs.

Wu is also a great social favorite.

Dr. Wu ’s new “stunts” are anxiously

awaited. He is famous here for his

endless questions and his unceremo-

nious behavior.”

Poster of Chinese Exclusion Act

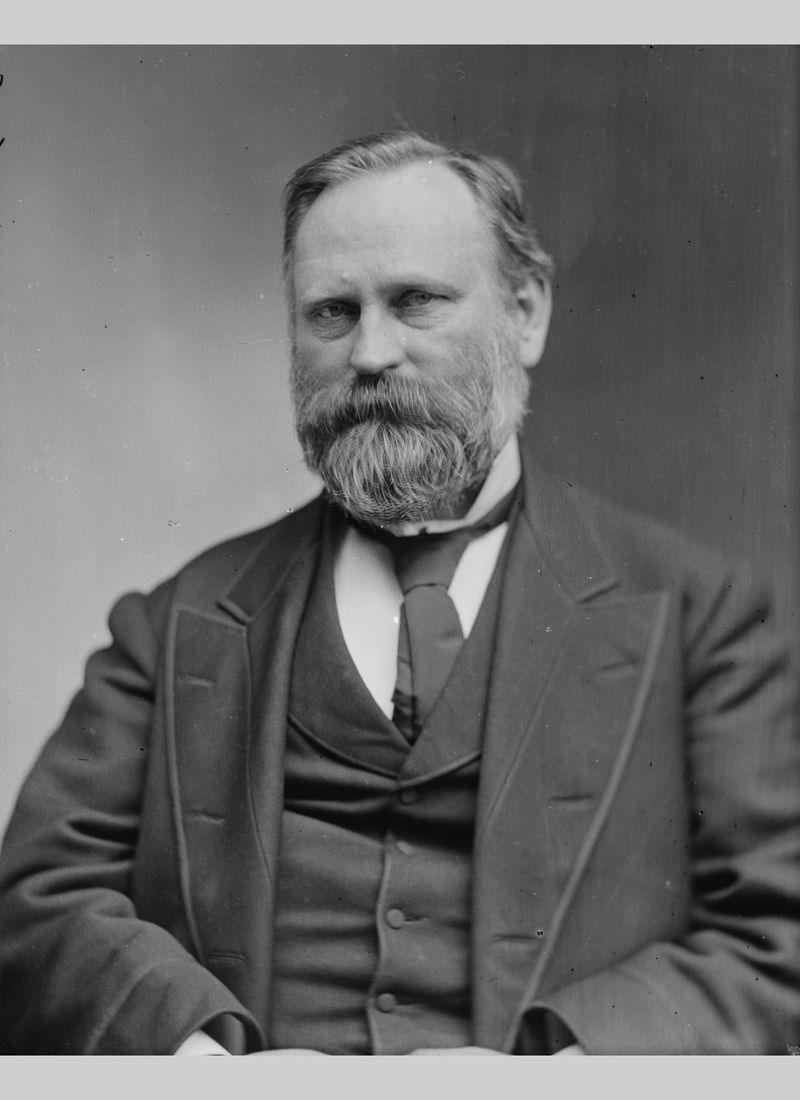

Prior to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, there was already widespread anti-Chinese sentiment throughout the United States, including even massacres targeting Chinese people. In 1880, the U.S. Congress had already passed the Treaty Regulating Immigration from China, also known as the Angell Treaty of 1880. At the time, a few American politicians stood in support of the Chinese, including Senator Thomas Stanley Matthews.

Portrait of Senator Thomas Stanley Mathews

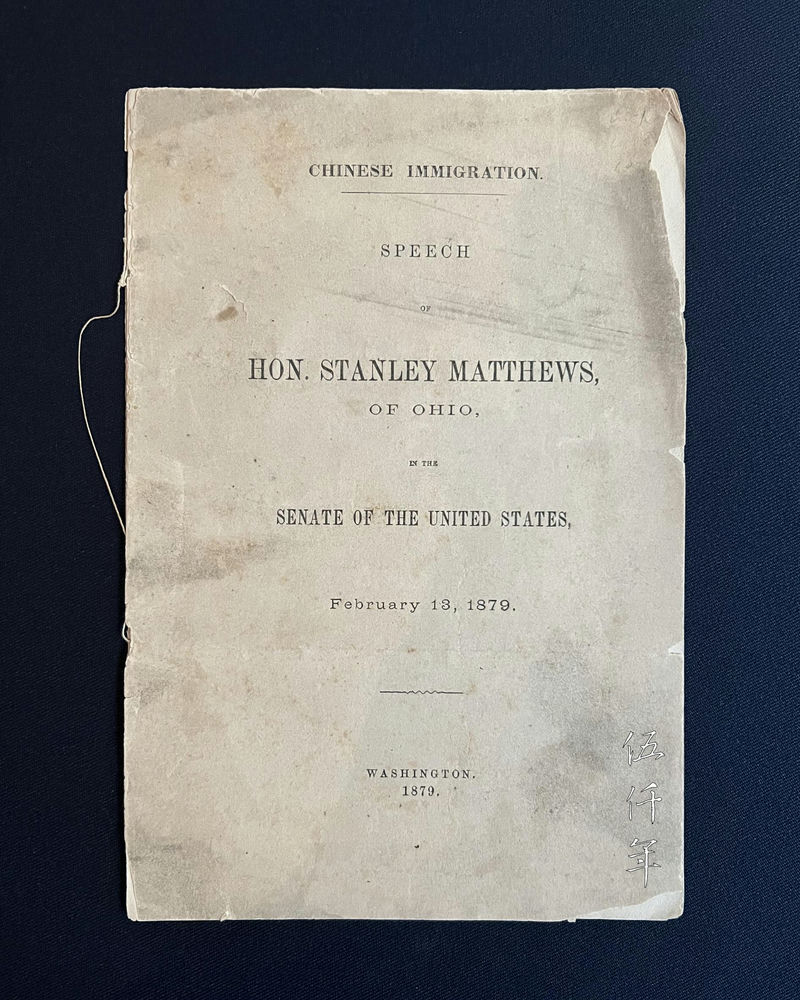

Front cover of transcript of speech by Stanley Mathews delivered on 13 February 1879

I have a pamphlet containing Senator Matthews’ speech opposing the Treaty Regulating Immigration from China delivered in the Senate on 13 February, 1879. The title of the pamphlet is Chinese Immigration and it is said that only two copies remain in the United States today. I have excerpted several passages from his speech in the hope that the eloquent words of the wise are not lost and his obscure name will be celebrated in our land. Part of the speech reads as follows:

“Mr. President: I am charged with the responsibility as a Senator on this floor of casting a vote upon the passage of this bill. I shall vote against it, and I am not willing to let the occasion pass without also putting on record some at least of the reasons which influence my vote.

The question, in my opinion, is too important, its right decision rests upon principles that are too familiar and at the same time too sacred, and its consequences as a practical measure of legislation upon our character as a nation among the family of nations and upon our material relations to the government of the Empire of China itself are too serious to be passed by, in my judgment, without proper discussion, without a proper understanding, such as I fear will not be given to it by the public at large; I fear not by a majority of the Senators on this floor.

Mr. President, if I believed that the representations which have been made in respect to the evils to be remedied by this legislation were as true, as faithful to the fact as no doubt those gentlemen sincerely do who make them, I should still be compelled to vote against this bill. If I believed that we not only had the constitutional power but the moral right to keep out from our social and political body voluntary immigrants from the Chinese Empire or elsewhere on the face of the globe; if I believed that the good to be accomplished and the evil to be averted by keeping them out were as great as the gentlemen who represent on the floor of this body the States of the Pacific coast do believe them to be, nevertheless my respect for the sanctity of the plighted faith of the nation in a solemn treaty with a sovereign power would compel me to seek some other method of securing these results than this arbitrary act of legislation.

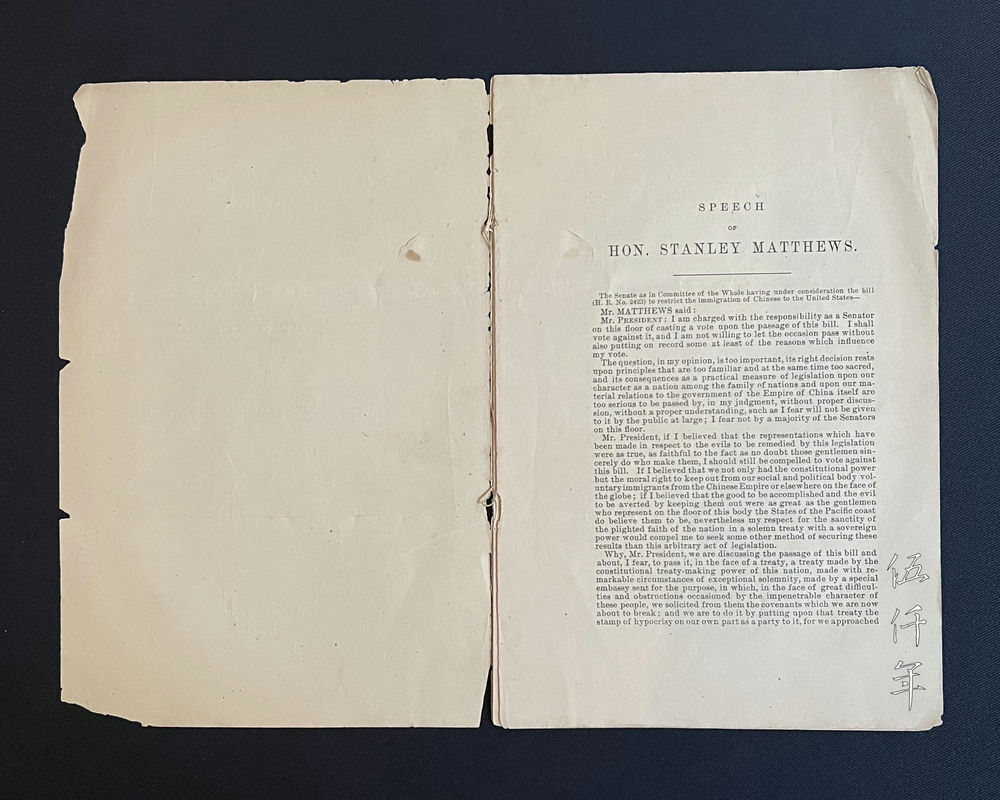

Inside page of transcript of speech by Stanley Mathews

Why, Mr. President, we are discussing the passage of this bill and about, I fear, to pass it, in the face of a treaty, a treaty made by the constitutional treaty-making power of this nation, made with remarkable circumstances of exceptional solemnity, made by a special embassy sent for the purpose, in which, in the face of great difficulties and obstructions occasioned by the impenetrable character of these people, we solicited from them the covenants which we are now about to break; and we are to do it by putting upon that treaty the stamp of hypocrisy on our own part as a party to it, for we approached the Chinese government in the Burlingame treaty with such expressions as these:

‘The United States of America and the Emperor of China cordially recognize the inherent and inalienable right of man to change his home and allegiance.’

And also:

‘The mutual advantage of the free migration and emigration of their citizens and subjects respectively from one country to the other for purposes of curiosity, of trade, or of permanent residence.’

Inside page of transcript of speech by Stanley Mathews

What has occurred since the date of that treaty to give the lie to that declaration? If none but our own convictions have changed either as to the right or the expediency, then by the same bonds with which we bound the parties let us seek to unloose them from the obligations into which we entered. Let us go to the Emperor of China and say that the experience of the nation and of the world since that time has convicted us of the error of that profession, and that not-withstanding the mistake under which we entered into the contract at that time we desire to make the correction with their consent, as with their consent we entered into it.

Suppose, Mr. President, this were a treaty with Great Britain; suppose it were a treaty with France or Germany or any other fighting nation; suppose it were a treaty with a Christian nation and not with pagans and heathens; would it be consistent with the obligations of international law, would it be consistent with the courtesy that prevails in international intercourse, would it be consistent with our own self-respect, would it be consistent with that wholesome fear which every man and people have when they are on the brink and verge of doing that which they are conscious to be wrong, that we should approach them in any other way than by the peaceful way of amicable negotiation? Would we dare, in the face of the opinion of the civilized world and in the fear of the consequences of exciting the indignation and just anger of a proud and high spirited people, be guilty of this act of Punic faith, repudiating the obligations of a treaty, without the ordinary and poor politeness of giving an antecedent notice of our intention, much less soliciting the consent which binds nations by a moral obligation as strong, as high, as great, as those which affect the consciences of private individuals?

We have the constitutional power to do this thing, Mr. President. I do not question that. We have the right by law to repeal any other law, and we have the power by law to violate all our treaties; and when it has passed into the form of an enactment and received the sanction of the whole law-making power of the body politic, it is then the binding law of the country, but it is a law nevertheless in breach of a treaty and in violation of solemn and plighted faith.”

Inside page of transcript of speech by Stanley Mathews

Inside page of transcript of speech by Stanley Mathews

Thomas Stanley Mathews (1824-1889), also known as Stanley Matthews, was born in Cincinnati County, Ohio, United States. He graduated from Kenyon College in 1840 and obtained his law license in 1845. He practiced law in Cincinnati County and was editor for an anti-slavery newspaper before becoming a county judge. From 1856 to 1858, he was a member of the Ohio State Senate, and from 1858 to 1861, he was the Ohio State Prosecutor. When the Civil War broke out, Matthews joined the Union Army and served as a Lieutenant Colonel and later as a Colonel. In 1863, he became a judge of the High Court in Cincinnati County, and in 1865, he resumed his private law practice. In 1876, he was elected as a Senator, and in 1881, he became a Justice of the Supreme Court.

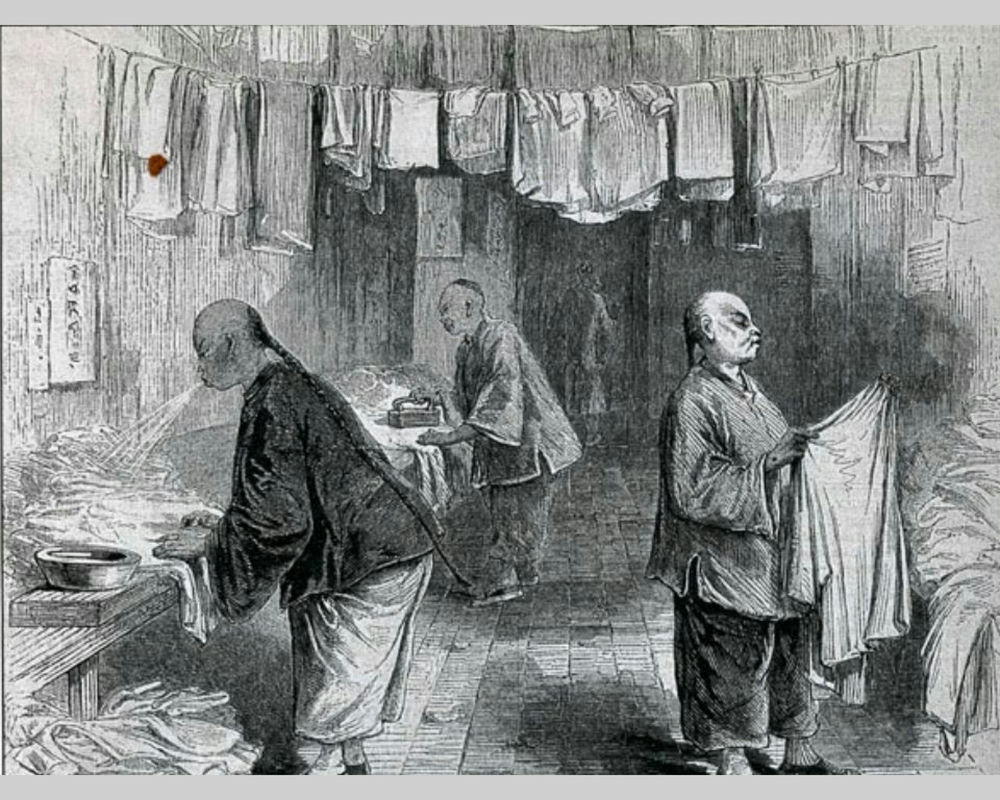

19th century illustration of Chinese laundry in San Francisco

One of his famous judgments was in the case of Yick Wo v. Hopkins. In 1880, the San Francisco city government passed an ordinance requiring laundry businesses located in wooden buildings to obtain additional permits. At the time, 95% of the laundry businesses were situated in wooden buildings, and two-thirds of them were owned by Chinese immigrants. However, the city government refused to grant the additional permits to Chinese laundry businesses while granting them to others. As the Chinese owned laundries did not have the required permits, fines were imposed. A Chinese laundry owner, Yick Wo, refused to pay the fine imposed on him and was consequently imprisoned. In his judgment, Matthews ruled that the administration of the ordinance was discriminatory and there was no need to consider whether the ordinance itself was lawful. Although the Chinese were not citizens, they were entitled to legal protection, and the government's abuse of power had to be held accountable. The ordinance was aimed at excluding Chinese immigrants from the laundry industry and the law should be struck down.

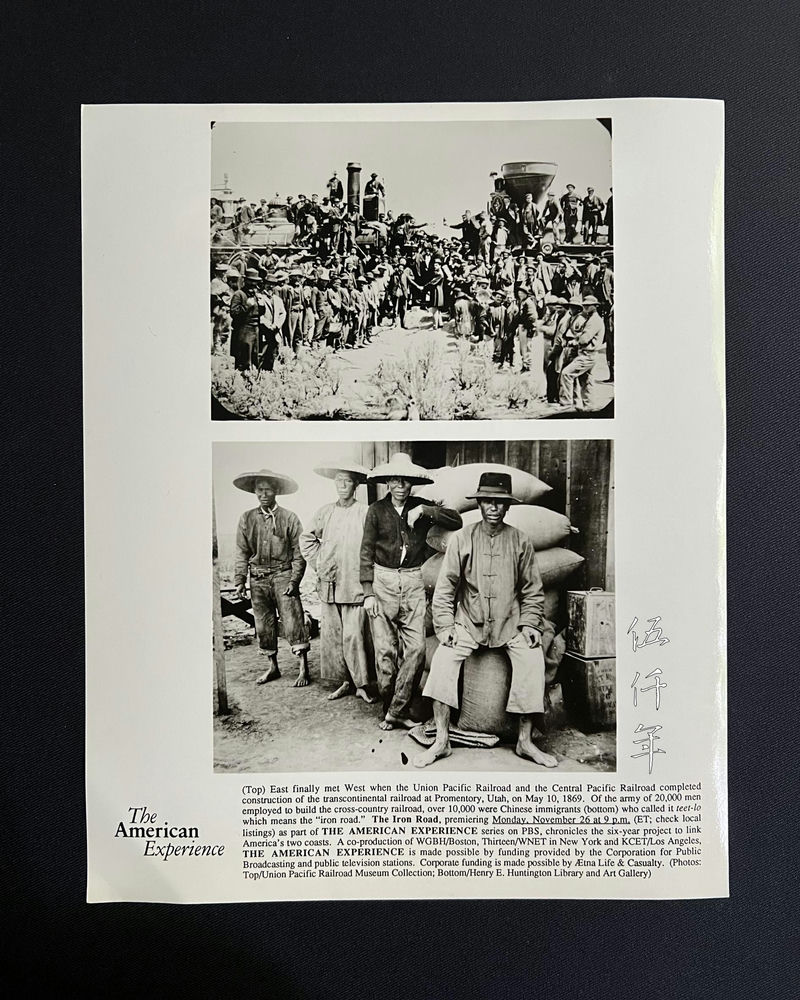

Group portrait of Chinese immigrant workers taken at the completion of the cross-country railroad on 10 May 1869

I reflect on life in this world, regardless of the period, no matter inside or outside China, there will always be instances of injustices that fill one's heart with indignations. Often, ordinary people find themselves helpless, and in extreme cases, they suffer physical and mental trauma, or even lose their lives. Occasionally a few are willing to render righteous assistances. When their efforts succeed, they are likened to parents who grant life. When their efforts fail, all is but futile. Success or failure is indeed unpredictable. Acts of righteous assistance are seldom seen. This is because people's hearts are cold and indifferent, they fear power and authority, and prioritize their own interests. As a result, our society is loaded with maladies like a sick incurable person. Regarding the Chinese Exclusion Act in the United States, condemnations made by the Chinese diplomat Wu Ting-fang and denunciations made by Senator Stanley Matthews delivered no immediate impact at the time. Yet they are glimmers of light in the darkness and consciences in a dissolute world. Submerged for decades, when change was thrusted upon the day, they rose with the winds to illuminate the world and to affect the Four Seas. Affairs in the world do follow this principle. In the long-drawn-out and stifling night, those who extend righteous assistances, implement the work of their consciences, will furnish enough aggregation to ignite the flames of change the moment daybreak arrives.

Portrait of Wu Ting-fang in Harper’s Weekly on 17 November 1900