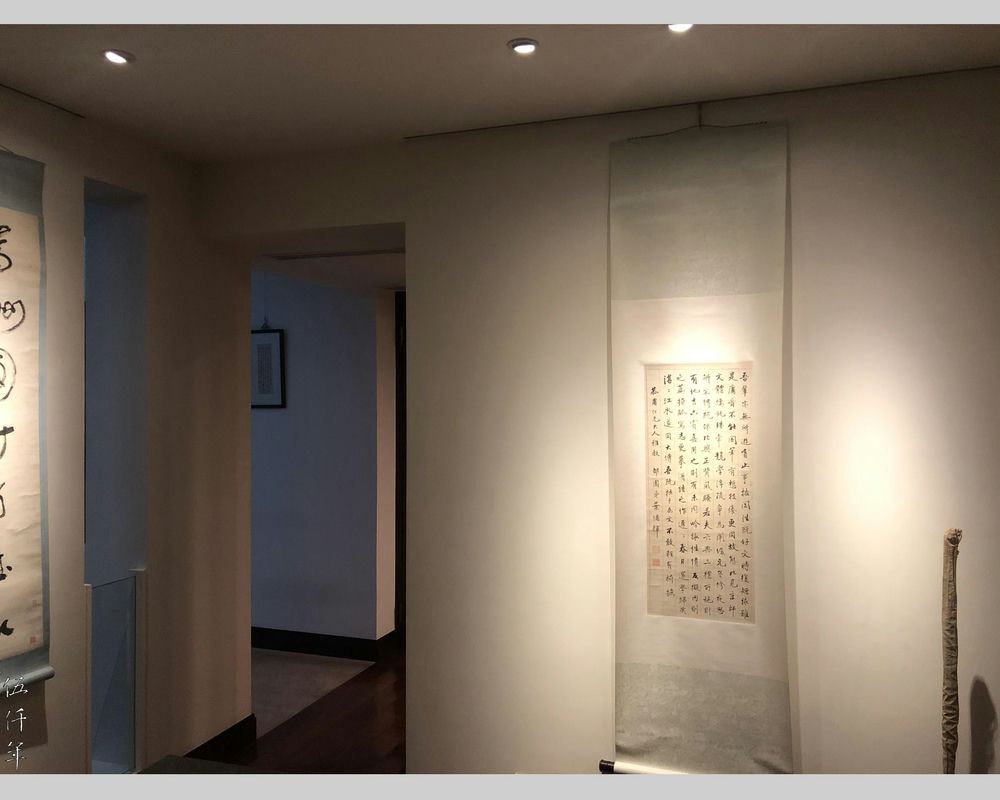

Calligraphy in the format of hanging scroll by Yeh Te-hui displayed in room

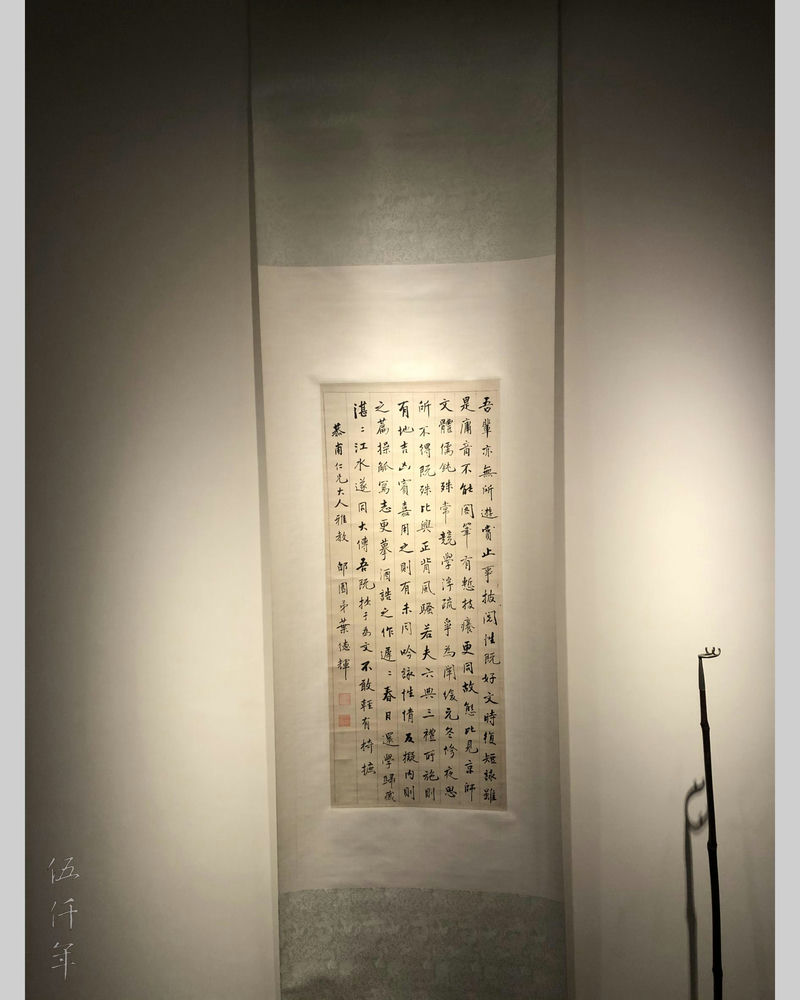

Calligraphy in the format of hanging scroll by Yeh Te-hui displayed on wall

Yeh Te-hui (葉德輝 1864-1927), tzu Huan-pin, Huan-fen,Yü-shui, hao Chih-shan, Hsi-yüan. He was a native of Soochow, Kiangsu province, however he accompanied his father to live in Ch’ang-sha, Hunan province. He attained the chin-shih degree in the eighteenth year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1892). He was a prominent scholar at the end of Ch’ing dynasty and the beginning of the Republican era. He was also one of the central figures in conservative cultural circles. His academic interest was in the studies of the Chinese Classics, and his private library Kuan-ku T’ang was celebrated in his time. His published works are extensive, but his calligraphic works are few. The text of this piece is a portion of a letter written by Chien-wen emperor (簡文帝 549-551 BC) of the Liang dynasty (502-557 BC), addressed to the Lord of Hsiang-tung (湘東王). The brush strokes were executed in the more dilettantish literati style. This is a scroll to be much cherished.

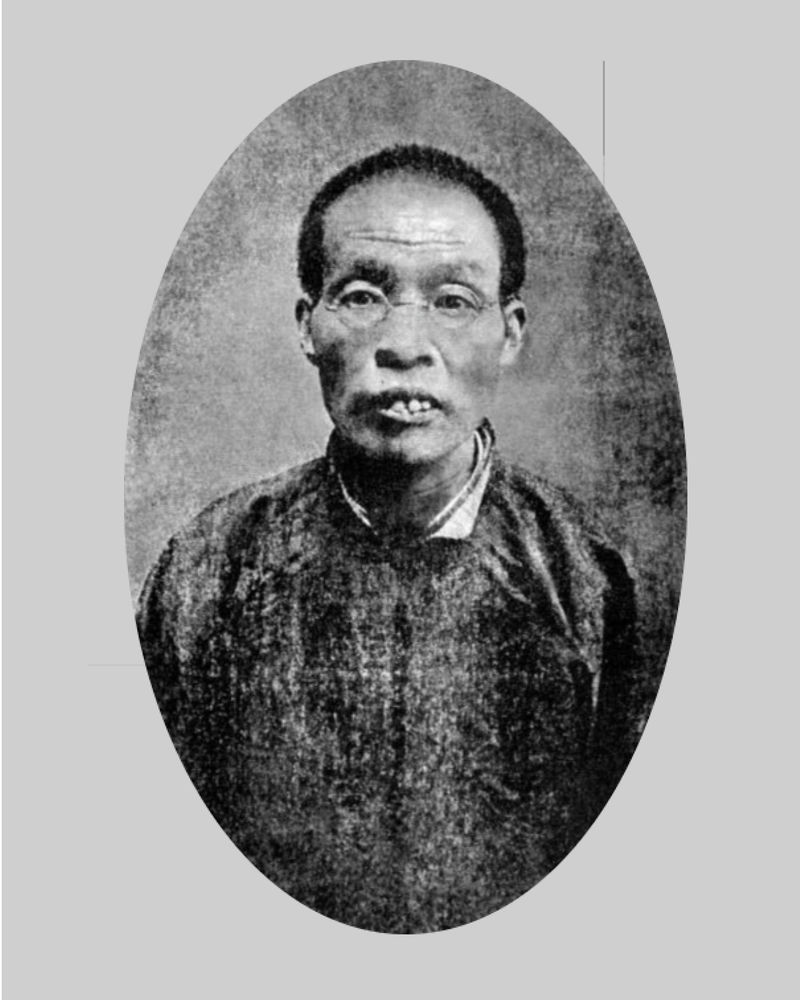

Portrait of Yeh Te-hui. Photograph courtesy Mr. Jen Ta-meng

In the sixteenth year of the Republic (1927), Yeh Te-hui was executed by the communists during an insurrection they incited in Ch’ang-sha, Hunan province. The news reverberated across the country. It also marked the beginning of arbitrary killings of the intelligentsia by the Chinese communists. The tz’u poet Wang Chao-yung (汪兆鏞 1861-1939) wrote in A Short Biography of Mr. Yeh Te-hui:

“In the year ting-mao (丁卯 1927), there was a rebellion by the communists, they killed him (Yeh Te-hui), there was not a person in the country who did not feel hurt and regret.”

The late historian Zso Shun-sheng (左舜生 1893-1969) wrote A Collection of Historiettes of Modern China (中國近代史話集), the chapter on Yeh Te-hui recorded his death in some detail:

“In the 16th year of the Republic (1927), Yeh was ultimately killed by the communist members of the Peasant Association in Ch’ang-sha. At that time I was not in the country. The details of his killing are still unclear. There was rumour that he provoked catastrophe by berating the Peasant Association with a pair of couplets. The couplets are:

Agricultural lot ascends, rice, millet, bean, wheat, glutinous millet and corn, are all ‘mixed breeds,

Assembly site opens, horse, cow, sheep, chicken, dog and pig, are all ‘savage brutes’.

‘Mixed breeds’ and ‘savage brutes’ are the most popular objurgating slangs in Ch’ang-sha. In the poetry anthology of Wu Ch’ü-an, Mei (吳瞿安, 梅 1884-1939), Shuang-ya shih-lu (霜崖詩錄), there are two eight line poems with five characters to each line that mourn Yeh Te-hui. They portray the life of Yeh rather well. The poems are:

Your eyes never acknowledged equal peer,

For me you granted approvals once in a while.

How could I foretell in our last farewell,

A star would fall in the southern sky?

Calamity became the price of humour,

Rule of law had lost its wonted way.

Is it possible to find another Ts’ai Yung (蔡邕 132-192 AD),

Who can likewise compose truthful epitaph?

Your grand name loomed over the four seas,

The districts of Three Wu (Wu-hsien, Wu-hsing and Hui-chi) were your haven.

Once you built a mansion fit for a learned scholar,

A painterly vision of overflowing antiquities.

Remarkable works were written,

Magnificent books were collected,

Indulgence in Taoist pursuits,

Remained a hindmost skill.

Murdering such specimen of a classical scholar,

Boundless Heaven,

Where can I implore justice?

This is the only writing on Yeh Te-hui I have come across after his murder.”

We can observe that the traditionalists have been in disagreements with the Chinese communists from the very beginning.

Cursive and regular script calligraphy by Yeh Te-hui. The Studio of Prunus Ode Collection

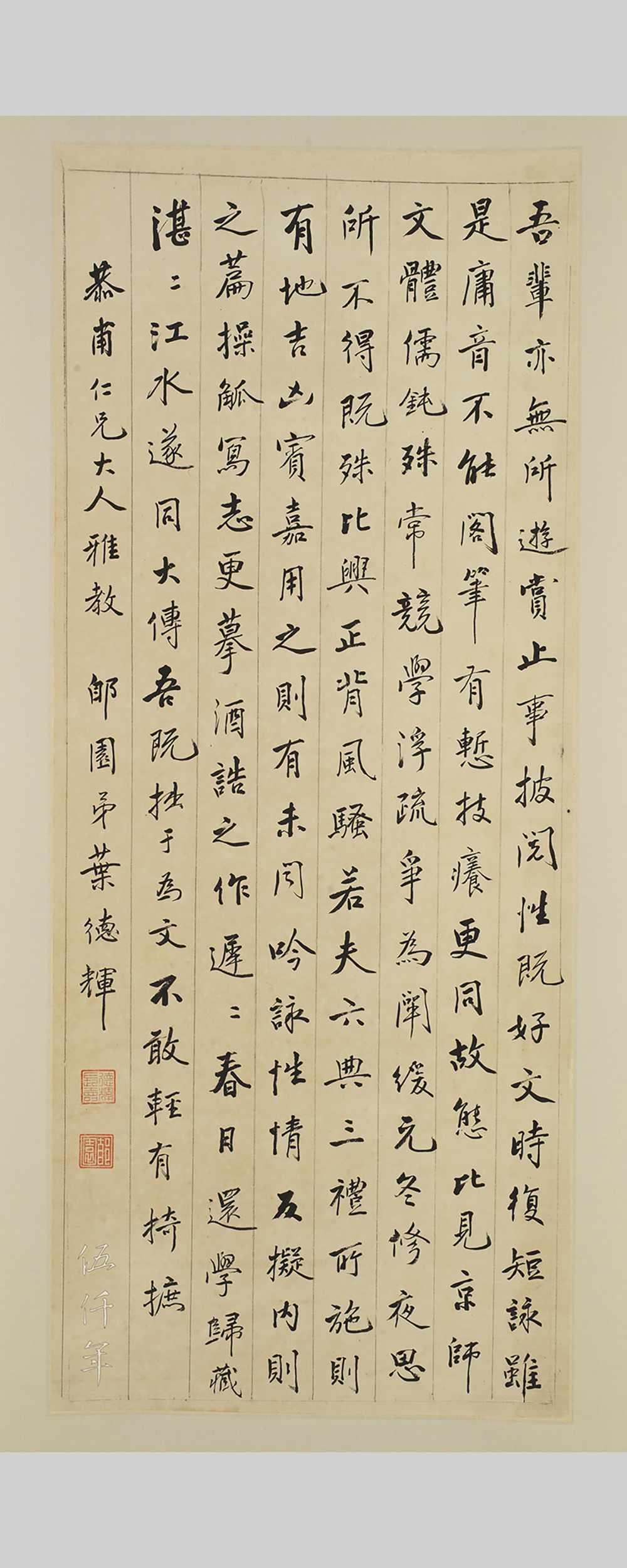

Cursive and Regular Script Calligraphy by Yeh Te-hui, Copying the Text of a Letter from Chien-wen Emperor of Liang dynasty to the Lord of Hsiang-tung.

The text reads:

“We have nothing to linger and relish, so we ended up reading. My nature is fond of literature, and occasionally I also compose short verses. Although they are ordinary words, it is difficult to rest the brush. Embarrassed, yet still itching to write, I return to the old way more than ever. Comparing my writings to the literary form of the capital, they are especially insipid and crude. I have only competed to learn vanity, and raced to become slackened. In the long nights of winter, I reflect on the literary qualities that I fail to attain. My writings diverge from the requisite skills of applying metaphors and symbols, they are the opposites of our classical literary heritage. Regarding the Six Codes of Chou dynasty and the Three Rites of Han dynasty, land is available for their implementation. Regarding the Rites of Sacrifice, Burial, Government and Propriety of Chou dynasty, they are there for enactment. It is unheard to convey temperament in poetry, one reverses to imitate Nei-tse (內則) in The Book of Rites (禮記). To communicate aspiration in composition, one emulates Chiu-kao (酒誥) in The Book of Documents (尚書). In the long spring days, I return to study Kuei-ts’ang (歸藏, a book of divination), observing the cavernous river, like reading Shang-shu ta-ch’uan (尚書大傳). Since I am ungainly in writing, I do not have the courage to lightly delve into literary criticism.

Anticipating the refined instruction of the honourable Kung-fu, from the junior Hsi-yüan, Yeh Te-hui.”

The two seal impressions are:

“Longevity of Te-hui” and “Hsi-yüan”.

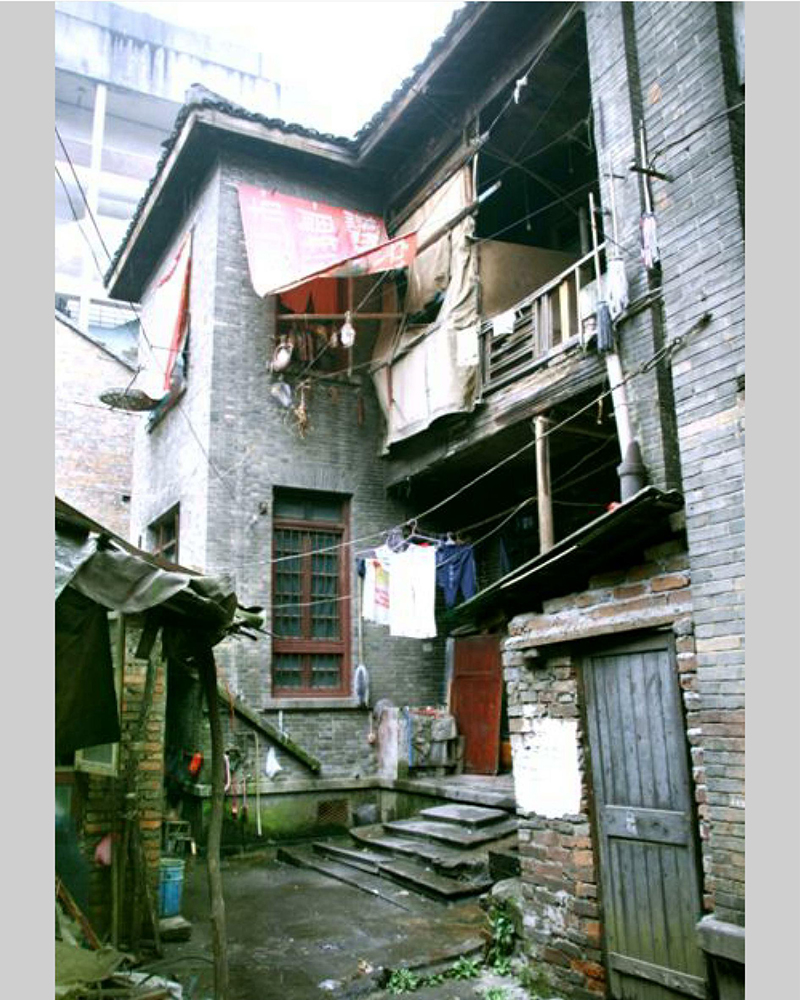

The former residence of Yeh Te-hui, photographed by Mr. T’ang Wu in 2006. The building was demolished in 2012