The whole of China was astonished by the Republican Revolution that broke out on 10 October 1911. On 12 October, Su-chou governor Ch’eng Te-ch’üan, in the company of members of Kiangsu Provincial Council, Yang T’ing-tung and Lei Fen, invited Chang Chien from Nan-t’ung to draft together, deep into the night, a telegram petition to advice the court to announce the immediate implementation of a new constitution and a congress, with the hope that these acts could halt the engulfing revolution. On 13 October Ch’eng Te-ch’ üan decided to first forward the telegram to generals and senior officials in numerous provinces, requesting them to sign their names in support, but few responded.

The telegram petition was finally hastily sent out to Peking on 16 October. However the court did not reply. On 22 October, the Republican soldiers reached Ch’ang-sha and established the Military Government of Hunan. By December, fifteen provinces had declared independence in succession. The rage of revolution was unstoppable. Although the telegram petition could not save Ch’ing dynasty from demise, the telegram draft became a precious historic document that recorded the final effort of the monarchists to save the imperial throne.

Yang T’ing-tung kept the telegram draft for many years. In 1921 he asked the eminent painter Wu Hu-fan to create a painting titled Autumn Night Petition. He mounted the telegram draft and the painting together as part of a handscroll. After the fall of mainland China In 1949, the descendant of Yang brought the handscroll to Taiwan, and it was eventually gifted to the National History Museum. Recently the historian Ch’en Ying acquired a copy of the book Photographic Record of the Autumn Night Petition Handscroll, published in 1971. Ch’en Ying chronicled the whole story and induced much reflection. Had the imperial throne decided to implement constitutional monarchy earlier, the success and failure of the Republican revolution would be hard to fathom.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

In the last years of the Ch’ing dynasty, the political system of China had become the primary reason for her backwardness. Specifically, after the reigns of K’ang-hsi and Ch’ien-lung, the emperors of Ch’ing dynasty were no longer as tenacious as their predecessors, there were no “enlightened rulers” to take control of the country’s destiny. Any clear-headed Chinese could see that China was being increasingly marginalized in the world. At the same time, they could see that the fundamental solution to this problem lay in changing the political system. Constitutional monarchy would be the system of choice causing the least upheaval. It was the most viable path, the most realistic and idealistic form of government for China to pursue at the time.

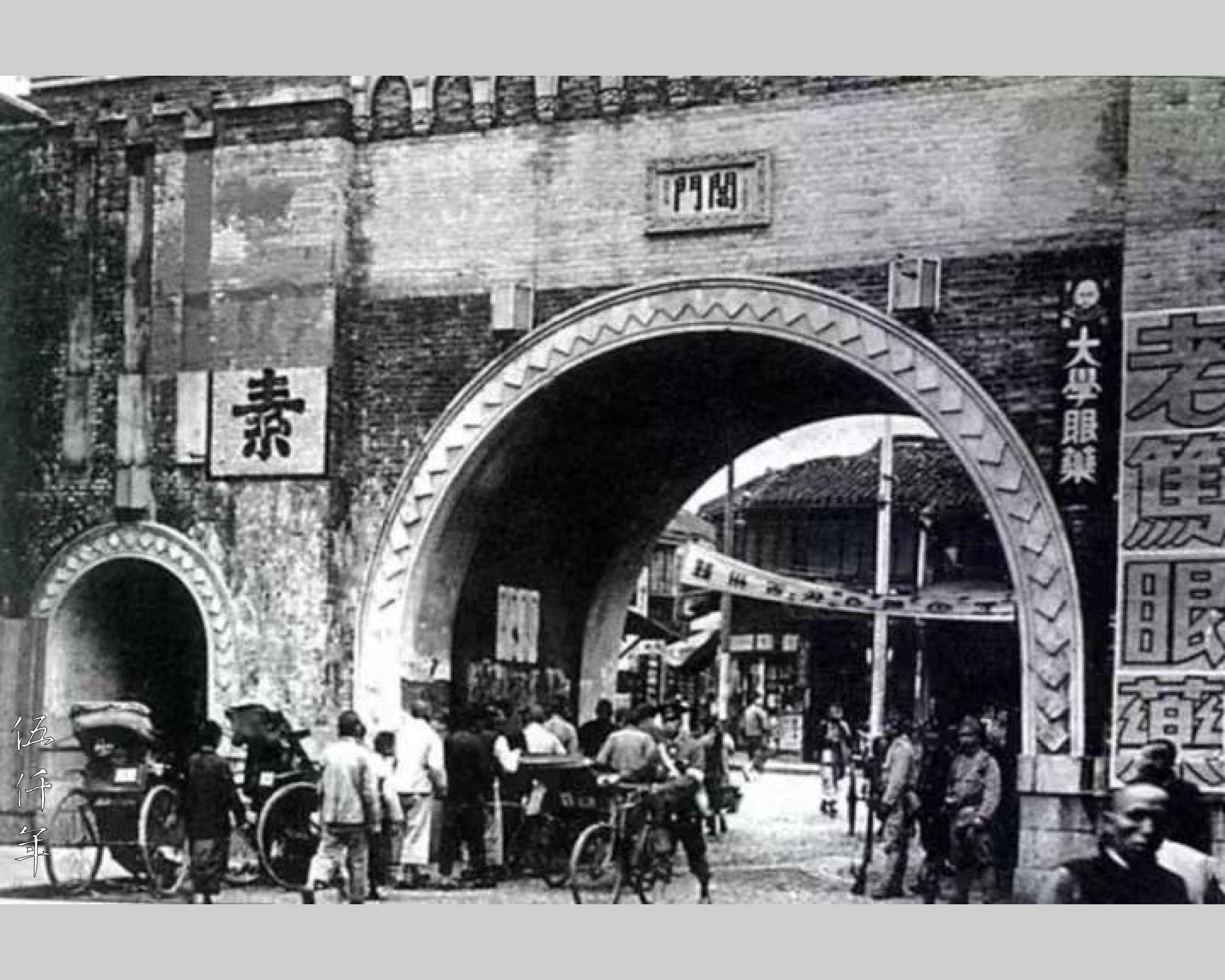

Front facade of Kiangsu Provincial Consultative Bureau

Due to the assiduous efforts of K’ang Yu-wei (康有為) and Liang Ch’i-ch’ao (梁啟超), China began to move towards constitutional monarchy. On 16 July 1905, the Ch’ing court ordered five ministers including the Defender Duke Tsai-tse (載澤) to visit various countries in the East and the West to study their constitutional systems in preparation for constitutional reform. In September 1906, the preparatory constitutional process was announced, and the Nine-Year Constitution Preparation Edict (九年預備立憲詔) was promulgated. On 20 September 1907, the court began to plan for the establishment of an Advisory Council (資政院). On 1 September 1906, the Ch’ing court announced plans for a trial constitution, with official implementation to be expected after ten to twenty years of preparation. In October 1907, preparations were made to set up local consultative bureaus (諮議局) in various regions to gather public opinion. In 1908, the Imperially Approved Constitutional Outline (欽定憲法大綱) was published, laying out the direction and framework for a constitutional monarchy. On 8 May 1911, members of the first cabinet were announced. However, among the thirteen cabinet members, nine were Manchus, and seven of them were from the imperial family or royal clans. This led to the cabinet being labeled the “Royal Cabinet”, causing a public outcry. It raised strong doubts about Ch’ing court’s sincerity in implementing constitutional reform, whether amongst those who originally supported constitutionalism, those who were biding time, or those who were against it, including Chang Chien (張謇), a leading figure of the Kiang-nan (江南) group of constitutionalists.

Group portrait of members and staff of Kiangsu Provincial Consultative Bureau taken on the opening day of the Bureau

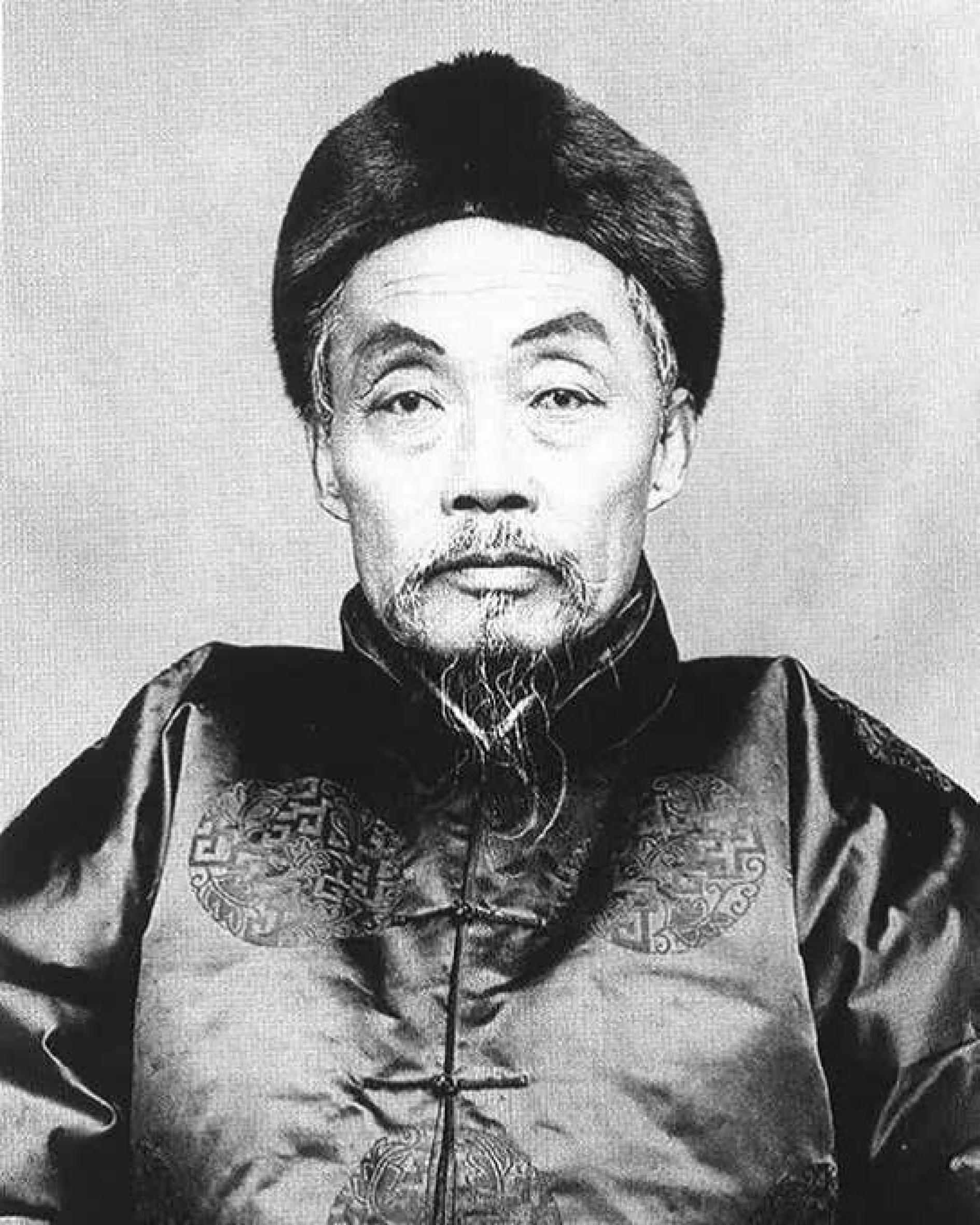

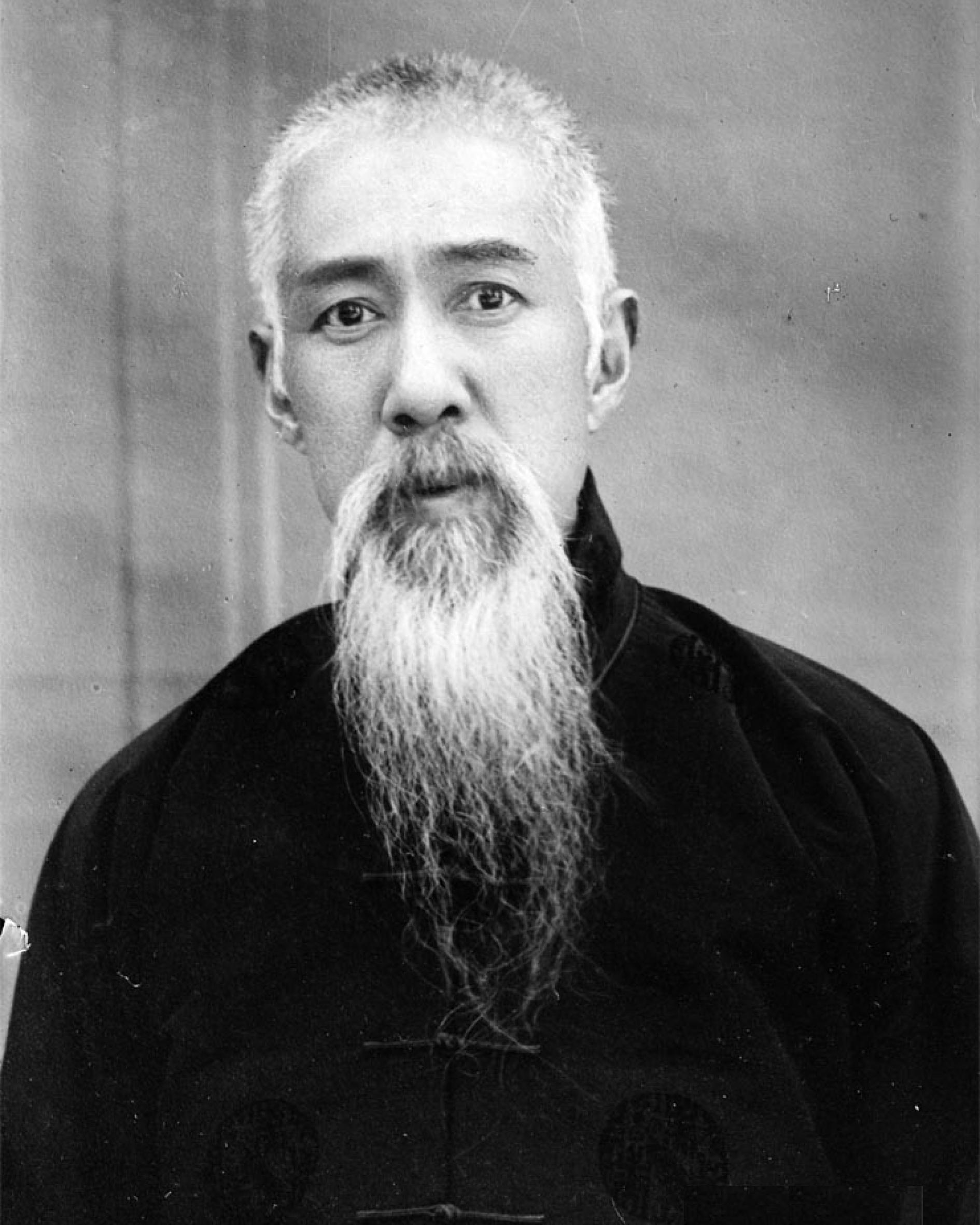

As the principal graduate (狀元) in the final years of the Ch’ing dynasty, Chang Chien enjoyed widespread prestige in Kiang-nan, therefore he became the organizer of the Kiangsu Provincial Consultative Bureau (江蘇省諮議局). The Consultative Bureau was a special institution created under the constitutional movement, it was a subordinate of the Advisory Council, which was the preparatory institution for the constitutional movement in late Ch’ing. Colloquially speaking, the Advisory Councils in the provinces were also called Consultative Bureaus. However, the Consultative Bureau in each province was respectively set up in September 1909 before the establishment of the Advisory Council. It was a local public opinion institution to deliberate on provincial administrative reform, budget, tax law, public debt and other matters. The Consultative Bureau was also responsible for electing members from each province to the Advisory Council. However, its powers were strictly limited by the provincial governor-general or governor. As members of the Consultative Bureau were elected by public opinion in each province, it was the first election by popular vote in Chinese history.

Portrait of Chang Chien

The office of the Kiangsu Provincial Consultative Bureau was set up in 1908 at Pei-t’ing Lane of Nanking (南京碑亭巷) by Chang Chien and other Kiang-nan officers and gentry such as Fan Tseng-hsiang (樊增祥), Chen Po-t’ao (陳伯陶), and Hsia Yin-kuan (夏寅官). Fan Tseng-hsiang (樊增祥) and Chen Po-t’ao (陳伯陶) served as chief administrators (總辦), managers (會辦) included Jung Heng (榮恒), Li Jui-ch’ing (李瑞清), Chao Ts’ung-chia (趙從嘉), and Hsiung Hsi-ling (熊希齡), while Chang Chien served as superintendent (總理). In August 1909, the Consultative Bureau convened its official assembly, and Chang Chien was elected chairman (議長) by fifty-one votes (out of ninety-five attendees), becoming the representative figure of the Kiangsu constitutionalists. After its establishment, the Kiangsu Provincial Consultative Bureau held all kinds of meetings multiple times, deciding on legislation, taxation, finance and education in Kiangsu Province. It played a role in monitoring and evaluating the local government, thus becoming the earliest public opinion institution in Kiangsu.

Additionally, Chang Chien was an important leader of the Constitution Preparatory Association (預備立憲公會), another significant political organization of the constitutional movement in late Ch’ing period. In December 1906, over 200 members of the business and academic communities from Kiangsu, Chekiang, Fujian and other provinces set up the Constitution Preparatory Association in Shanghai, electing Cheng Hsiao-hsü (鄭孝胥) of Fujian as president, Chang Chien of Kiangsu and T’ang Shou-ch’ien (湯壽潛) of Chekiang as vice presidents. The main purposes of the Constitution Preparatory Association were to prepare for the implementation of the constitution, promote the court’s adoption of the constitution, improve people’ s knowledge of constitutional governance, publish vast amount of publicity material as well as books and periodicals to popularize information regarding constitutional government, establish schools for legal and political studies, and encourage local self-governance.

The fundamental reason why Chang Chien opposed revolution and supported constitutionalism was that he did not want to see war and chaos. He once said:

“Since the reign of Ch’ing Emperor Kuang-hsü, revolutionary fervour intensified, and the idea of constitutionalism spread. Constitutionalism maintains a balance between private and public interests, accommodates the monarch and the people within rules, stabilizes the lives of millions of Chinese people as before, without upheaval and turmoil.”

As a literati steeped in Chinese culture from Kiang-nan, he was committed to treating the affairs of the nation as his personal duty. He believed revolution would inevitably lead to widespread armed conflict and that only a constitutional monarchy could balance the interests of all sides.

In his capacity as chairman of the Kiangsu Provincial Consultative Bureau and vice-president of the Constitution Preparatory Association, Chang Chien was naturally a leading figure among the constitutionalists in China. Up to the outbreak of the Wu-ch’ang Uprising, he still held great hope for constitutionalism. After the Wu-ch’ang Uprising, he drafted a noted memorial to the throne at the request of the Provincial Governor Cheng Te-ch’üan of Kiangsu (江蘇巡撫程德全) titled: A Memorial from the Provincial Governor Sun Pao-ch’i (孫寶琦) of Shandong and the Provincial Governor Cheng Te-ch’üan of Kiangsu to Request the Reorganization of the Cabinet and to Implement the Constitution(魯撫孫寶琦蘇撫程德全奏請改組內閣宣布立憲疏), a simplified title is Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night.

In the Self-Compiled Chronology of Old Man Se (嗇翁自訂年譜), Chang Chien recalled:

“(hsin-hai 辛亥 August) 25th day (16 October 1911 according to the Gregorian calendar). I arrived in Su-chou. Provincial Governor Cheng Te-ch’üan (程德全) agreed with me that the constitution should be swiftly promulgated and the National Assembly be convened. He asked me to compose a memorial. We had a rushed dinner. We returned to the hotel and asked Mr. Lei Fen (雷奮) and Mr. Yang Ting-tung (楊廷棟) to compose this together. Sometimes I wrote and sometimes I asked the two gentlemen to write. After midnight the draft was finished.”

This incident in the Chronology is a pivotal moment during the Hsin-hai Revolution, the memorial mentioned is of course the same Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night (秋夜草疏). It was the final attempt by the constitutional monarchists to save the Empire.

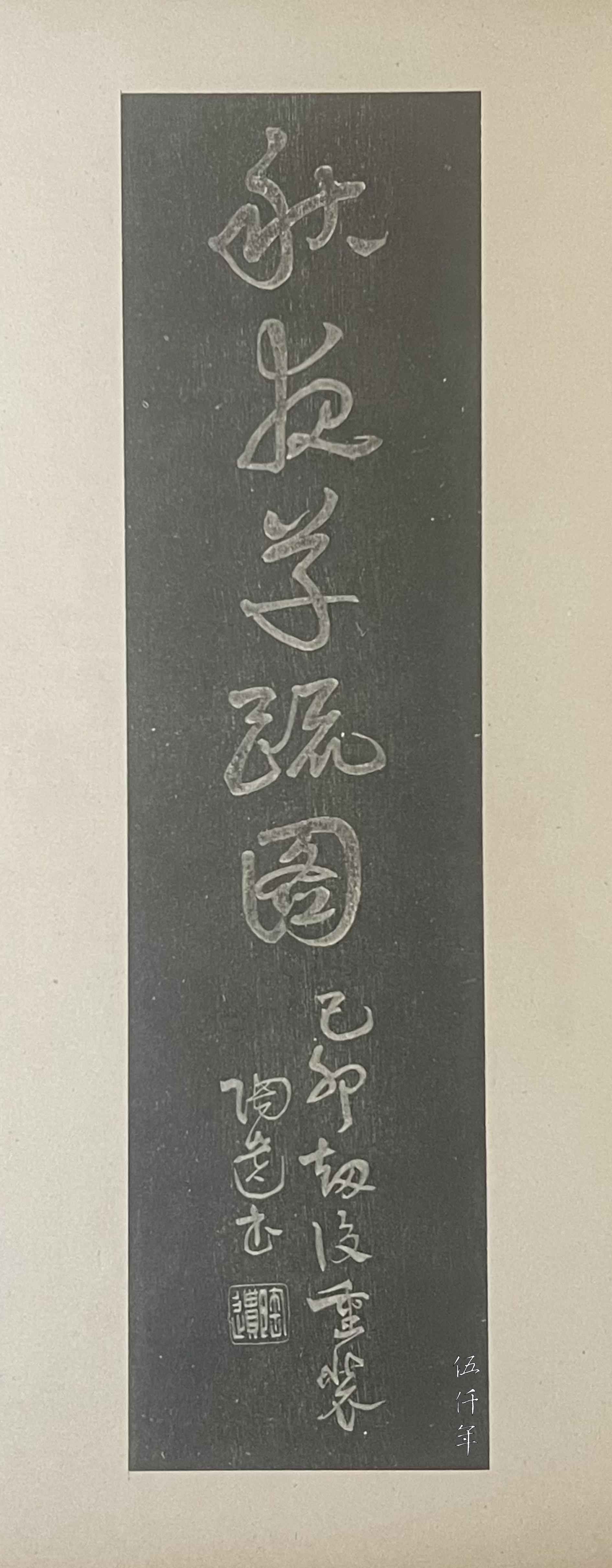

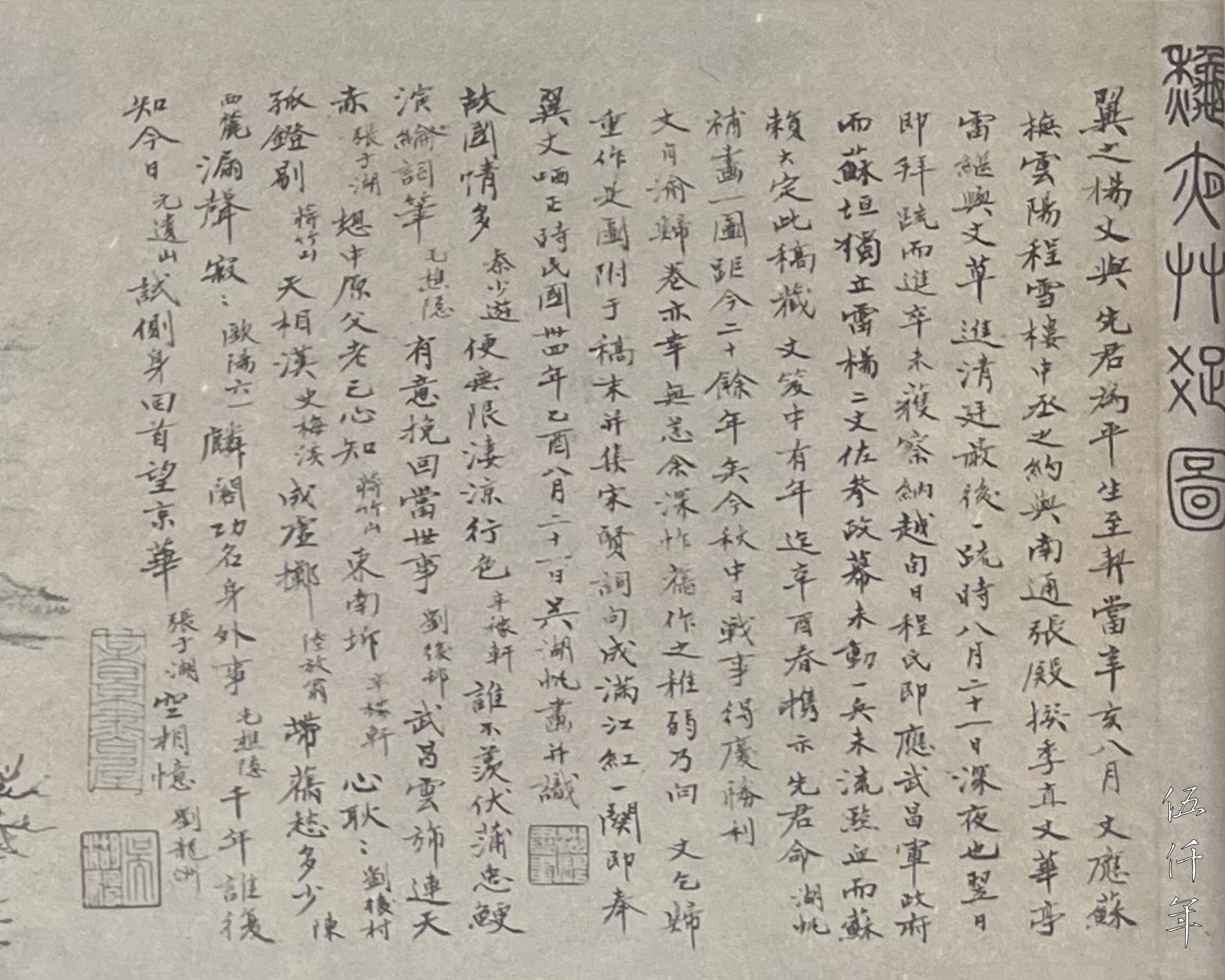

Title slip of Handscroll of Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night

The Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night had been under the custody of Yang Ting-tung, one of the three participants at the drafting of the memorial. Later he asked many eminent men to write colophons and to contribute a painting, they were then mounted into a handscroll, and became a complete record of this historic incident. This handscroll is now in the collection of the National Museum of History in the Republic of China (國立歷史博物館). Yang Ting-tung’s inscription describes the scene at the time:

Portrait of Yang Ting-tung

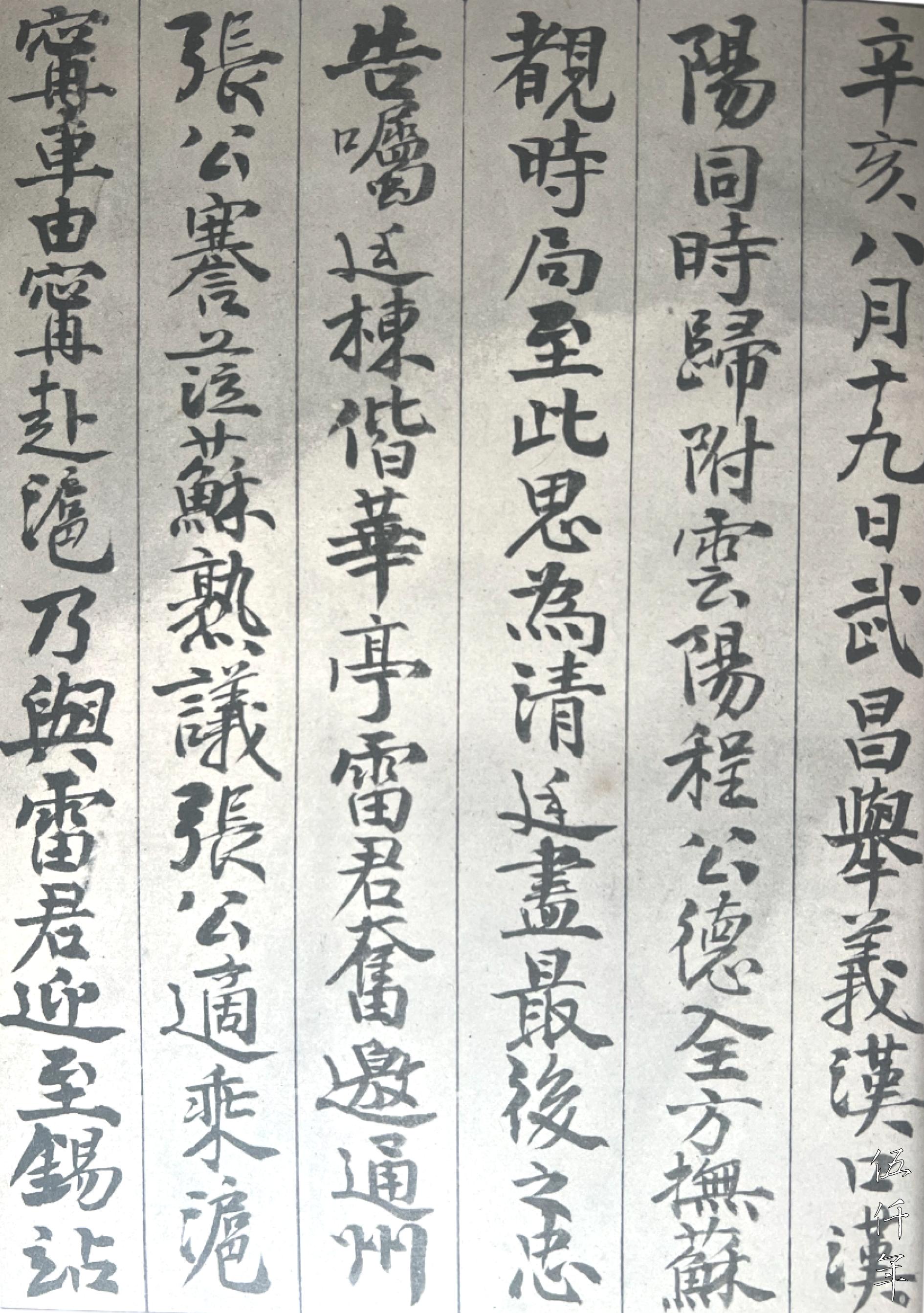

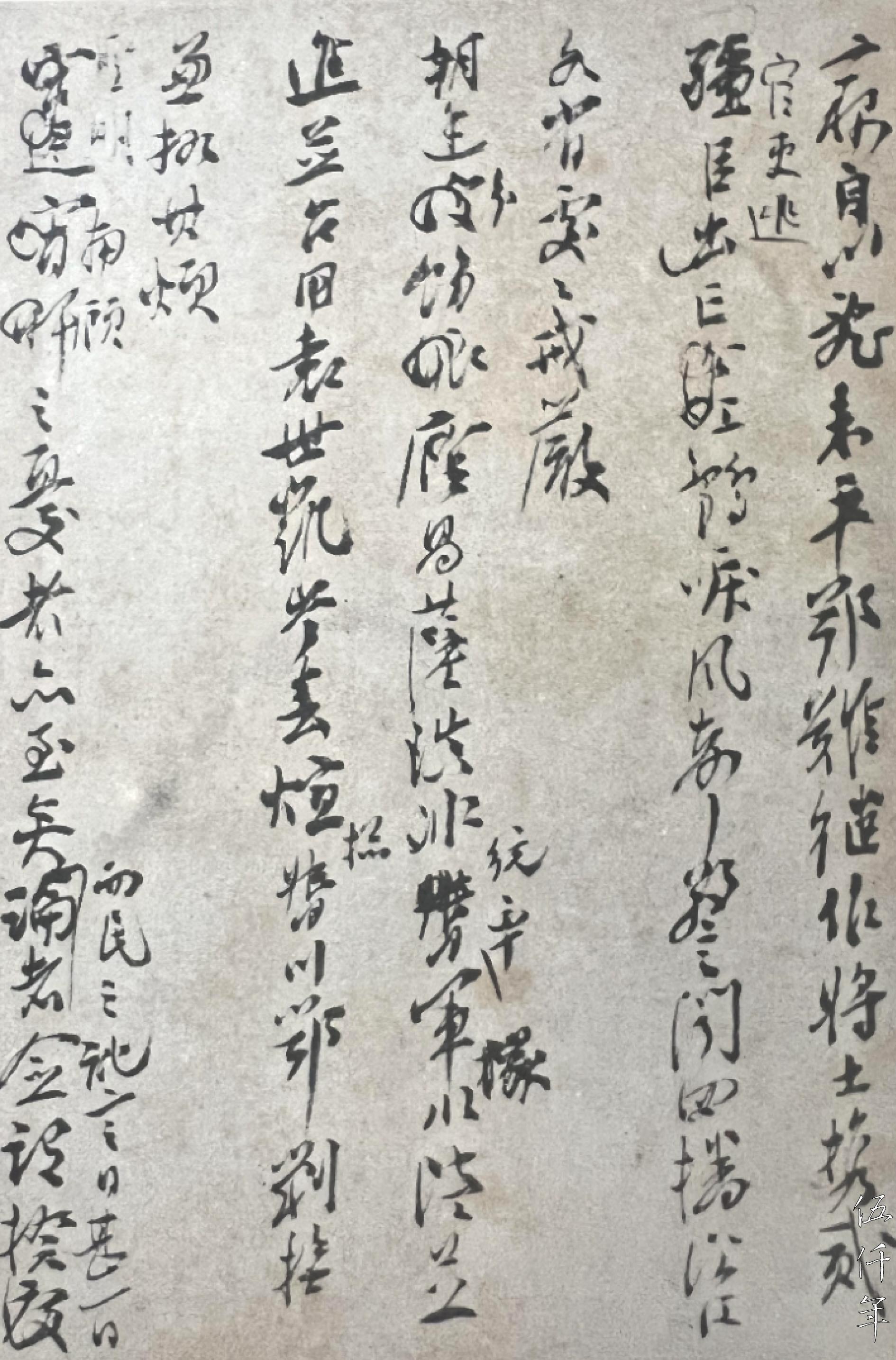

First section of inscription by Yang Ting-tung

“On 19 August of hsin-hai year, the Wu-chang Uprising broke out. Han-k’ou and Han-yang joined the uprising simultaneously. Mr. Cheng Te-ch’uan of Yün-yan was the provincial governor of Kiangsu. Pondering the ongoing situation, he considered to submit to the Ch’ing court his final act of loyal counsel. He instructed me and Mr. Lei of Hua-t’ing to do our best to invite Chang Chien of T’ung-chou to come to Su-chou for deliberations. Mr. Chang happened to be travelling on the Shanghai-Ningbo rail from Ningbo to Shanghai, so Mr. Lei and myself greeted him at Wu-hsi station and paid our respects in the train carriage. After explaining everything, we accompanied him to the governor’s office in Su-chou for discussions. That night we all stayed in the same hotel located several dozen steps west of Su-chou Station. It was known as the Wei-ying Inn (惟盈旅館). The Inn was far from the city centre, it was quiet without commotion. At night under room lighting, the memorial draft was prepared. In the beginning, Mr. Chang wrote by himself, then he dictated the text while Mr. Lei and I took turns writing it down. By the time the memorial draft was done, it was past midnight. In the morning, the memorial draft was sent to the governor’s office and Mr. Chang then left for Shanghai.

Another section of inscription by Yang Ting-tung

When Governor Cheng received the memorial draft, he telegraphed all the generals and governors in different provinces to seek their approval so that the it could be submitted to the court under joint names. I also telegraphed Mr. Chin in private for him to forward this to Mr. Chao Erh-hsün (趙爾巽), so that he could be the chief proponent. It was 22 August. Two days later, Commander-in-Chief P’u Ting (熱河都統溥頲) of Rehe, Provincial Governor Sun Pao-ch’i (山東巡撫孫寶琦) of Shandong replied by telegram that they agreed to lend their names. Both Minister of Railways Tuan Fang (鐵路大臣端方) and Governor-General Chang Ming-ch’i (兩廣總督張鳴岐) of Kwangtung and Kwangsi replied that the timing was pre-mature. Governor-General Ts’en Ch’un-hsüan (四川總督岑春煊) of Szechuan expressed his support but declined to lend his name. There was no reply from the rest. By then Kiangsi province had declared independence and Anhui was in a precarious situation. Governor Cheng believed the matter had become extremely urgent and the memorial would be in vain should there be further delay. Therefore, on the 25th, with Commander-in-Chief P’u appointed a proponent, along with Governor Sun and himself, the three of them endorsed the telegram by attaching their names and sent it to Peking. Then P’u sent a telegram to say that Mr. Chao Erh-hsün was not in favour of the move, and asked to withdraw his name from the telegram, and that he had already directly telegraphed the cabinet regarding this matter. At the time, Chao had just been appointed governor-general of the three eastern provinces of Liaoning, Kirin and Heilungkiang. Chang Ming-ch’i (張鳴岐) telegraphed again, saying this time that the memorial must be sent and that he was willing to append his name. Actually the telegram had already been sent, and both the cancellation and the approval were already too late.”

Portrait of Cheng Te-ch’uan

This inscription reveals that the matter was initiated by Cheng Te-ch’uan, the provincial governor of Kiangsu. Chang Chien, the leader of the Kiang-nan gentry, was the first person Cheng Te-ch’uan turned to as a suitable ally. The entire process of writing the memorial draft took place at Wei-ying Inn in Su-chou. The content was dictated by Chang Chien, and written in parts by Lei Fen and Yang Ting-tung.

Portrait of Lei Fen

The final telegram sent to Peking also included the endorsements from P’u Ting, commander-in-chief of Rehe, and Sun Pao-ch’i, governor-general of Shandong.

Portrait of Sun Pao-ch’i

According to the inscription by Yang Ting-tung, Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night took place in the evening of 21 August to the early morning of 22 August in hsin-hai year, which corresponds to the evening of 12 October to the early morning of 13 October 1911 of the Gregorian calendar. The Wu-chang Uprising broke out on 10 October, so Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night happened three days afterwards. This date is different to the recollection by Chang Chien in Self-Compiled Chronology of Old Man Se, which is 25 August of hsin-hai year, corresponding to 16 October 1911. This is rather the date the telegram was sent.

Portrait of Yü Keng

At that time, the situation in China had become more comprehensible, even members of the Ch’ing royal family were aware of the coming downfall. Princess Der Ling (德齡公主), daughter of Yü Keng (裕庚), the Ch’ing envoy to France, pronounced in an interview with Western newspapers:

“My father had said that within ten to fifteen years, a revolution would erupt in China that would end the rule of the Ch’ing dynasty. If the Ch’ing government could initiate immediate reform, perhaps the outcome would still be favourable. Otherwise, when the time comes, they would have to end their rule on their own.”

Although the Ch’ing court declared to the world that constitutionalism would be implemented within a certain deadline, the subsequent composition of the cabinet gave the impression of “fraudulent constitutionalism”. The revolutionaries continued with their uprisings, one by one they failed, but their efforts did not cease.

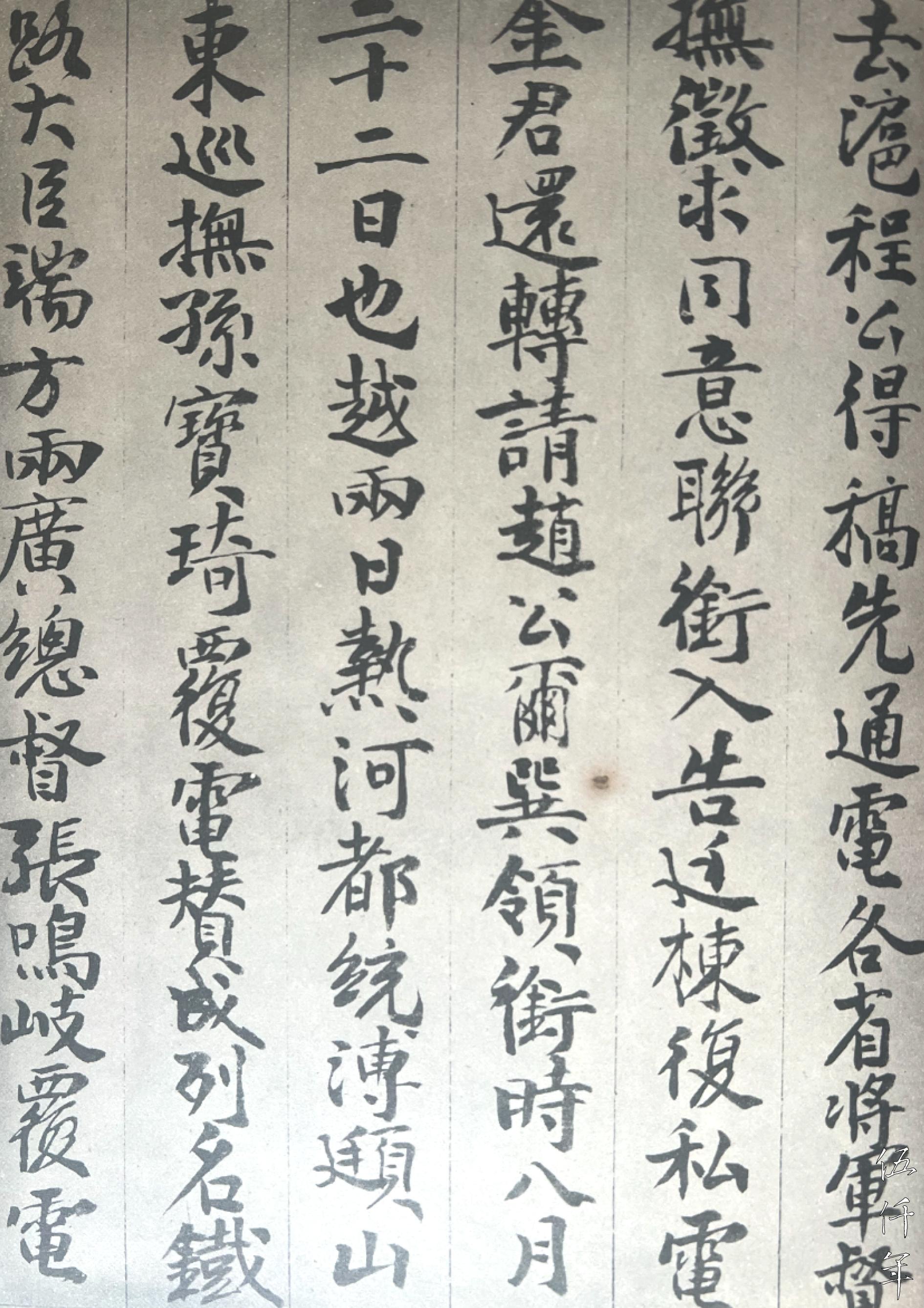

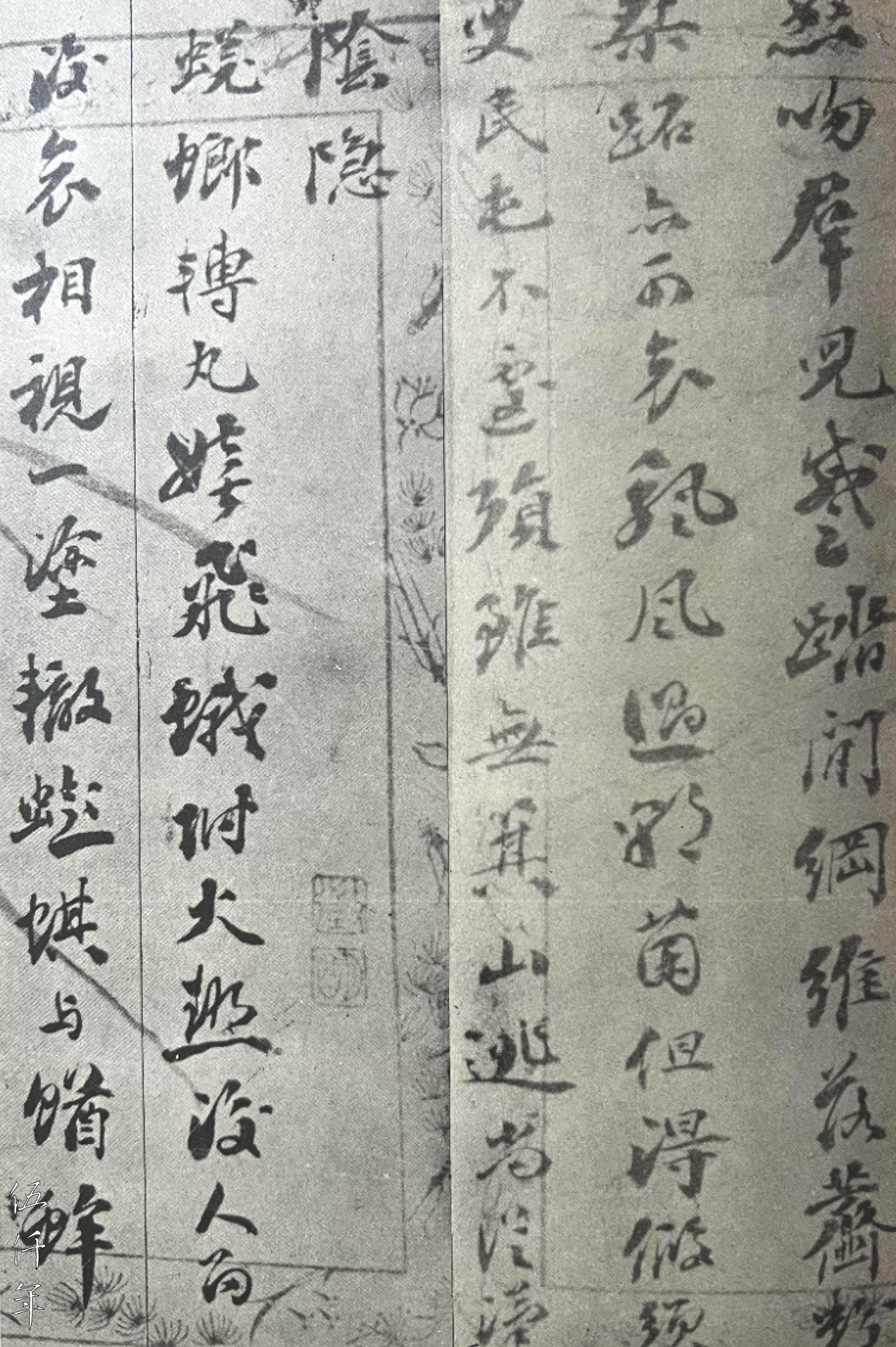

First section of Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night composed by Chang Chien

Another section of Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night composed by Chang Chien

The most important part of the Handscroll of Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night is of course the Memorial Draft to the Ch’ing Court (the full title is: A Memorial from the Provincial Governor Sun Pao-ch’I (孫寶琦) of Shandong and the Provincial Governor Cheng Te-ch’uan of Kiangsu to Request the Reorganization of the Cabinet and to Implement the Constitution (魯撫孫寶琦蘇撫程德全奏請改組內閣宣誓布立憲疏). It consists of over 2200 words. Due to the passage of time, 28 characters are illegible. The memorial analyzed the widespread instability and uncertainty of the time and the precarious situation which exhausted the Ch’ing court’s ability to cope. It went on to entreat the court in earnestness, to dissolve the previously established “Royal Cabinet”, to conduct new elections and to convene parliament as soon as possible to regain lost public trust and demonstrate the sincerity of the court’s effort at reform. The central message of the memorial is as follows:

“… Currently, public opinion is united on many issues. Such as it is inappropriate for relatives and nobles to organize the cabinet, and that ministers should bear full responsibility. Since the voice of the people is unanimous, those who have caused this disturbance have also created this outcry. It is proposed that the court should take the wise decision to follow ancestral laws and learn from the good practices of other nations. First, dismiss the current cabinet of relatives and nobles, select capable persons and reorganize the cabinet separately to ensure that it takes responsibility on behalf of the monarch. Preserve the dignity of the royal family and avoid conflicts in governance. Those primarily responsible for the unrest should be disciplined and publicly punished to appease the people. Then set up a time to inform the public, to bring forward the implementation of the constitution so that the nation can be renewed …”.

The entire memorial is earnest in its language and clear in its reasoning, reflecting the sincere concerns and thoughtful efforts of constitutionalists like Chang Chien and Cheng Te-ch’uan, who had the interests of the country and the people in their minds. As recorded in Yang Ting-tung’s inscription, the memorial was mainly dictated by Chang Chien and written by three men, Chang Chien, Lei Fen, and Yang Ting-tung. His words are:

“From the first line to the character ‘所’ in the tenth line, it was written by Mr. Chang himself. From the tenth line to the character ‘本’ in the forty-first line, it was written by Mr. Lei, and after that, it was written by Ting-tung. As for the revisions in the margins, some were made by Mr. Chang and some were made by Mr. Lei and Ting-tung.”

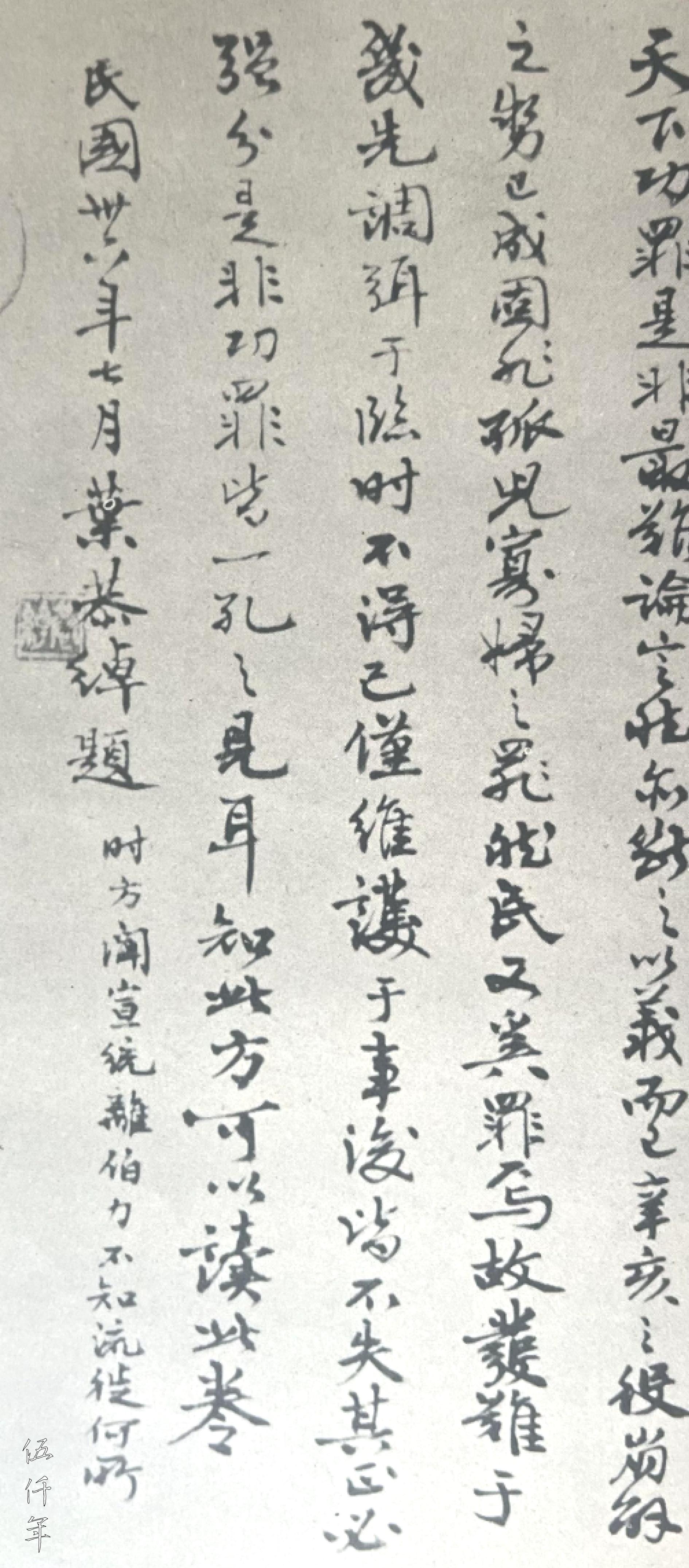

Inscription by Yeh K’ung-ch’o

As for the other parts of the Handscroll of Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night, many historical details are also revealed in Cheng Te-ch’uan’s letter to Yüan Shih-k’ai. The inscriptions by Chang Chien and others contain many poignant sentiments, in particular, the inscription by Yeh Kung-ch’o (葉公綽) stands out for its succinctness and profundity:

“The merits and demerits, rights and wrongs of the world are most difficult to judge, however they can be simply decided according to the principle of righteousness. When the battle in hsin-hai broke out, the momentum of collapse ensued. It was not the fault of the widow Empress Dowager Tz’u-hsi, nor the orphan Emperor Kuang-hsü, yet how could it be the fault of the people? Therefore, to start a confrontation, to resolve it right away, to sustain it obligatorily afterwards, none should be regarded as incorrect. Strictly insisting on right or wrong, merit or dismerit, is a narrow view like looking through a keyhole. Understanding this perspective is essential to reading this scroll.”

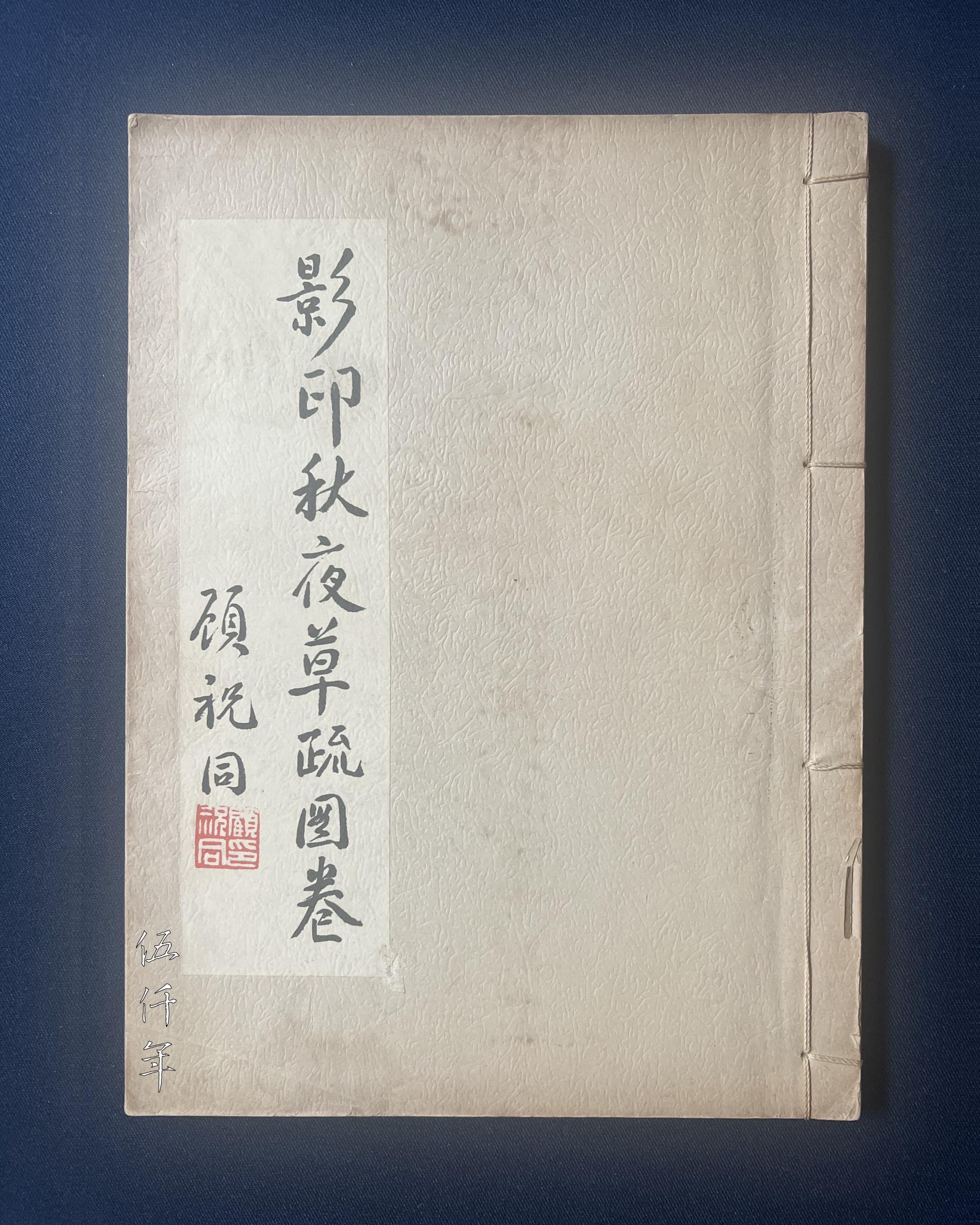

Front cover of Facsimile of Handscroll of Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night published by Yang Chih-yu, son of Yang Ting-tung

In 1971, Yang Chih-yu (楊之遊), son of Yang Ting-tung, published a book about this handscroll with the title Facsimile of Handscroll of Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night. The contents of the book consists of five parts:

- The first part is the original memorial draft penned in alternation by Chang Chien, Yang Ting-tung and Lei Fen, endorsed by Cheng Te-ch’uan, the provincial governor of Kiangsu.

- The second part comprises two unmailed letters from Cheng Te-ch’uan, Chang Chien and Chang I-lin (張一麟) to Yüan Shih-k’ai (袁世凱), a key official in the Northern Government.

- The third part features the painting of Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night, repainted by Wu Hu-fan (吳湖帆) in 1945. The original painting was commissioned by Yang Ting-tung in 1921.

- The fourth part consists of inscriptions and colophons written by nineteen important political and cultural figures associated with the revolution, such as Liang Ch’i-ch’ao (梁啓超), Sun Pao-ch’i (孫寶琦), Yeh Kung-ch’o (葉公綽), Li Ken-yüan (李根源), Chen T’ao-i (陳陶遺), Niu Yung-chien (鈕永建) and Kao Hsü (高旭).

- The fifth part is The Family Chronicle of Mr. Yang I-chih (楊君翼之家傳), who was also known as Yang Ting-tung. This was written by Liu Yüan (劉垣), the most trusted advisor to Chang Chien. It contains a wealth of information and provides a thorough analysis of the background of this event.

The Family Chronicle of Mr. Yang I-chih by Liu Yüan not only recorded the life of Yang Ting-tung in detail as indicated in the title, but weaving through it is the entire sequence of event from drafting the memorial in Autumn night to the successful revolution. How Chang Chien learned about the Wu-chang Uprising, how he notified Chang Jen-chün (張人駿) and T’ieh Liang (鐵良), advising them to make early preparations but received no response. How Liu Yüan and others “quickly went to Wu-hsi to meet him (Chang Chien) at the station, then traveled together to Su-chou ”. They “urged (Cheng) Te-ch’uan to telegraph the Ch’ing court to announce the immediate establishment of a constitutional government and the convening of parliament. Te-ch’uan followed their advice and entrusted Chang Chien to draft the document. …” Even more remarkable in this Family Chronicle are detailed elucidations of the reasons behind the submission of the memorial and the outcome of the petition. According to Liu Yüan, “The Ch’ing court received the telegram and ignored it, the revolutionary tide rapidly spread”. At this point, Chang Chien, Cheng Te-ch’uan and other constitutionalists who were still wavering lost all confidence in the Ch’ing court. Twenty days later, they proposed “Peaceful Restoration” (和平光復) which finally replaced their dream of “Constitutionalism”. With regard to the downfall of the Ch’ing dynasty, in The Family Chronicle of Mr. Yang I-chih, Liu Yüan also provided a fair assessment. Although the Hsin-hai Revolution erupted in Wuhan, the demise of the Ch’ing regime would not have been an easy feat without the successive declarations of independence from Shanghai and Su-chou.

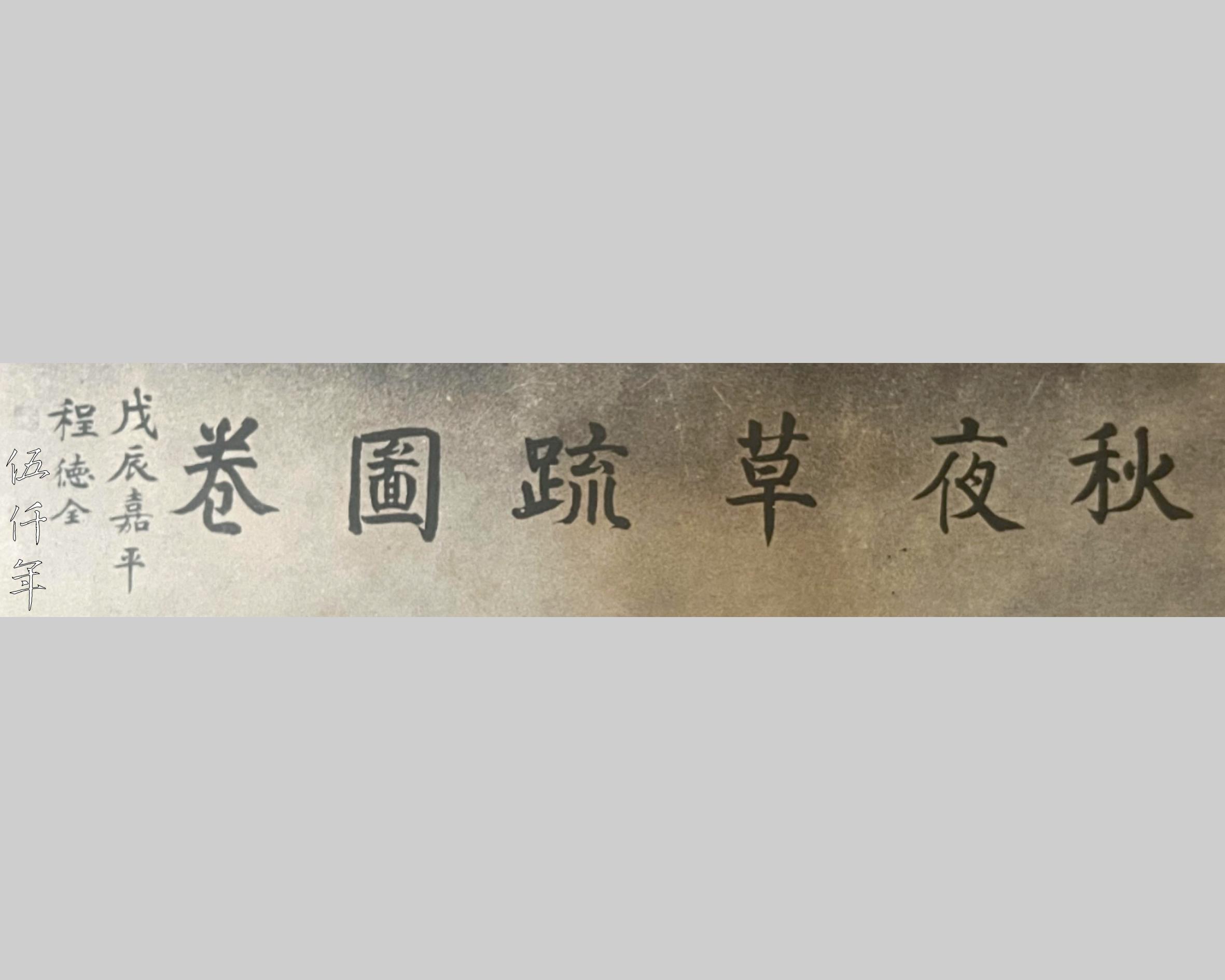

Calligraphy at front of handscroll by Cheng Te-ch’üan

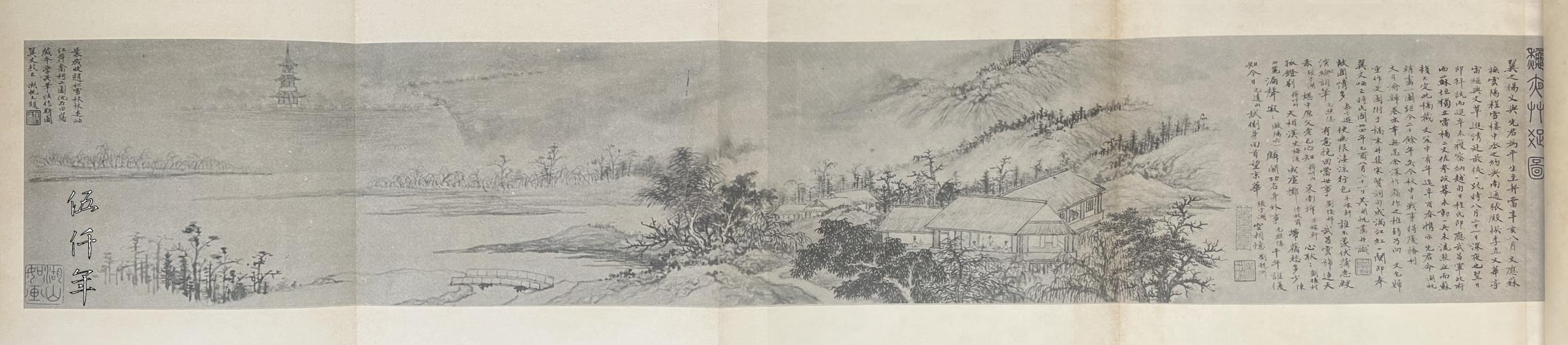

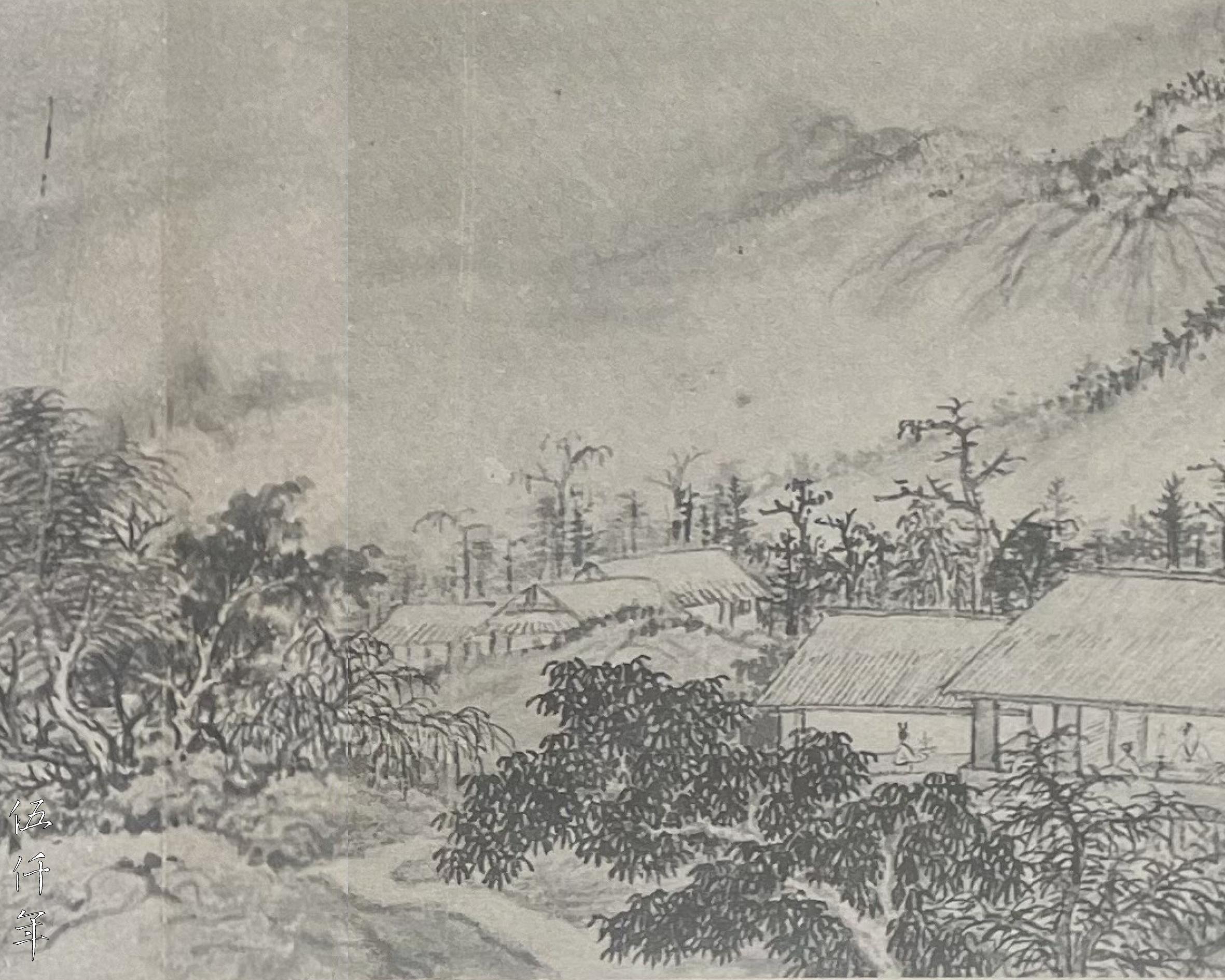

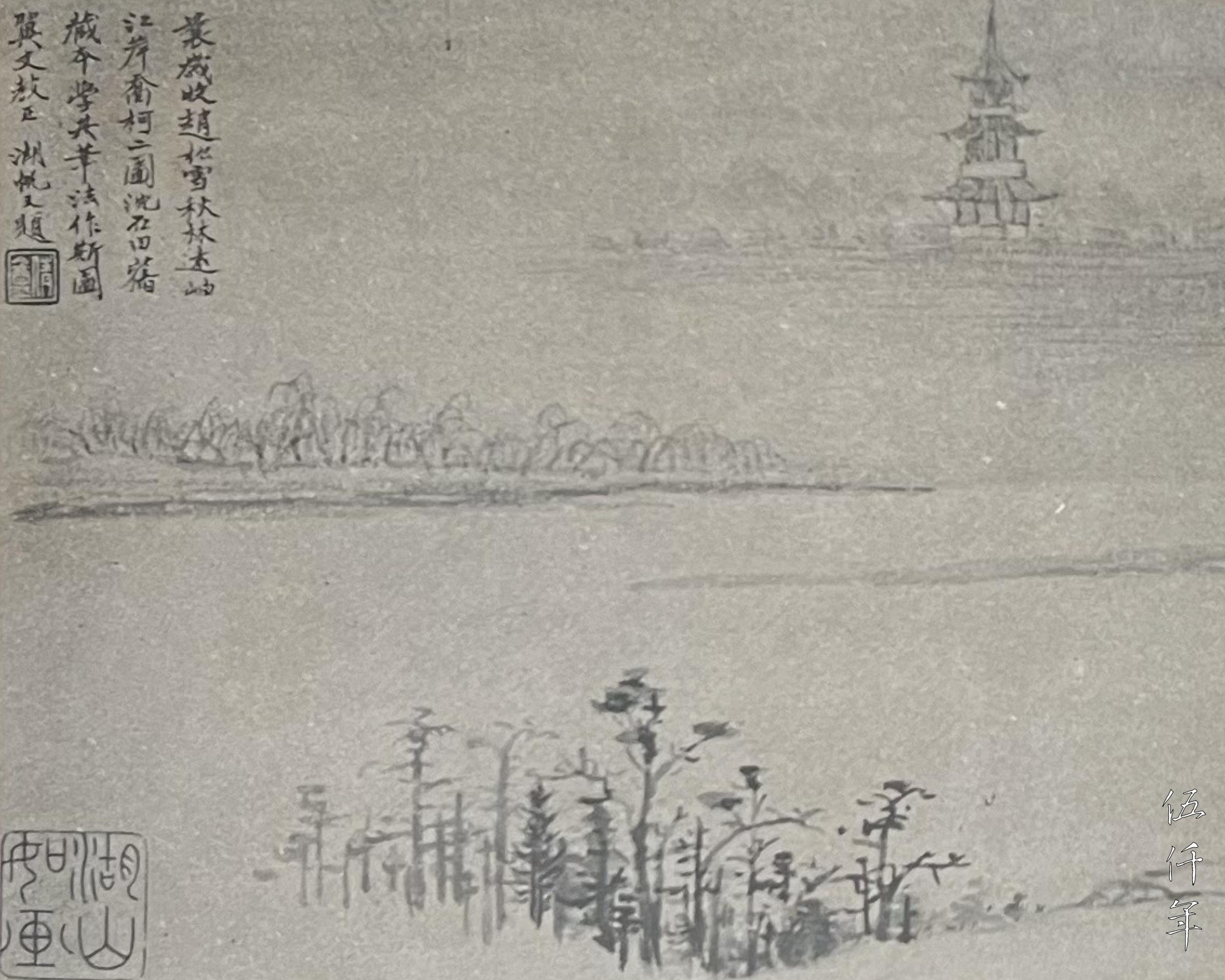

Painting titled Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night by Wu Hu-fan

First detail of painting

Second detail of painting

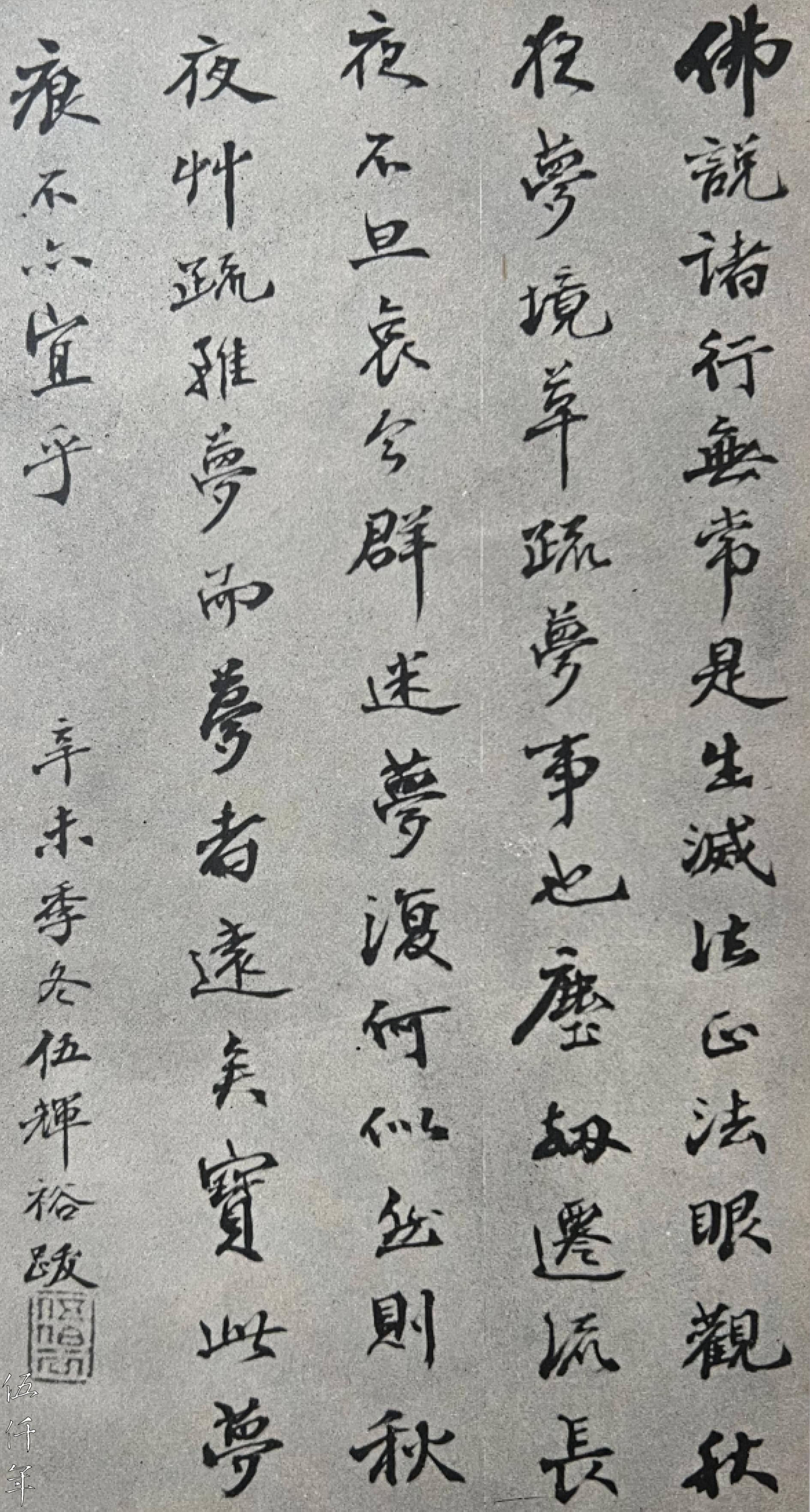

Yang Ting-tung had long been the custodian of the memorial draft. In commemoration of this historically significant event, he asked the famous painter of Su-chou, Wu Hu-fan (吳湖帆), son of his close friend Wu Pen-shan (吳本善), to create an ink painting based on the theme of Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night. Wu Hu-fan completed the painting in 1921. However, when he saw the painting again in 1945, Wu Hu-fan found his early work too immature and decided to make a new painting. This time Wu Hu-fan was very satisfied with his artwork. The painting depicts a night scene of dark shades, distant mountains faintly visible, the image of a towering pagoda, trees covering the foreground, and several houses nestling in between. In the center room, three people sit around a table, one holding a brush, another drinking tea and the third lost in thought. The composition is neat and elegant, with brushstrokes that are experienced and expressive, reflecting Wu Hu-fan’s consistent Kiang-nan style of painting. After the painting was completed, Yang Ting-tung invited notable persons related to the Revolution to contribute colophons and inscriptions, they were then mounted as a long scroll.

Inscription by Wu Hu-fan

In 1945, after Wu Hu-fan finished the new painting, he wrote the following inscription:

“Elder Yang I-chih (also known as Yang Ting-tung) and my late father were lifelong friends. In August of hsin-hai year, Elder Yang responded to the invitation of the provincial governor of Kiangsu, Cheng Hsüeh-lou (程雪樓 also known as Cheng Te-ch’uan) of Yün-yang, to draft a final memorial to the Ch’ing court together with Elder Chang Chi-chih (張季直 also known as Chang Chien) of Nantong and Elder Lei Fen of Hua-t’ing. This occurred late in the evening of 21 August. Next day they presented the memorial, but unfortunately it was not heeded. After ten days, Mr. Cheng accepted the new Wu-han Military Government while the city of Su-chou became independent. Elders Lei and Yang gave assistance and joined as advisers of political affairs, stability was achieved without mobilizing a single soldier, and without shedding a drop of blood. Kiangsu province was then settled. This draft has been kept by Elder Yang for years. In the spring of hsin-yu (辛酉) year, he brought it to show my late father who instructed me to add a painting. This was more than twenty years ago. This autumn, amidst the victory celebrations of the Sino-Japanese war, Elder Yang came back from Chungking and the scroll is fortunately unharmed. I was deeply embarrassed by my immature and weak early work, so I humbly asked Mr. Yang for permission to do a new painting to be included at the end of the scroll. I also selected different lines from the tz’u lyrics of Sung dynasty and assembled them into the tz’u lyric To the tune Man-chiang-hung (滿江紅), which I immediately presented to Elder Yang for rectification. Painted and written by Wu Hu-fan on 21 August of the 34th year of the Republic of China.”

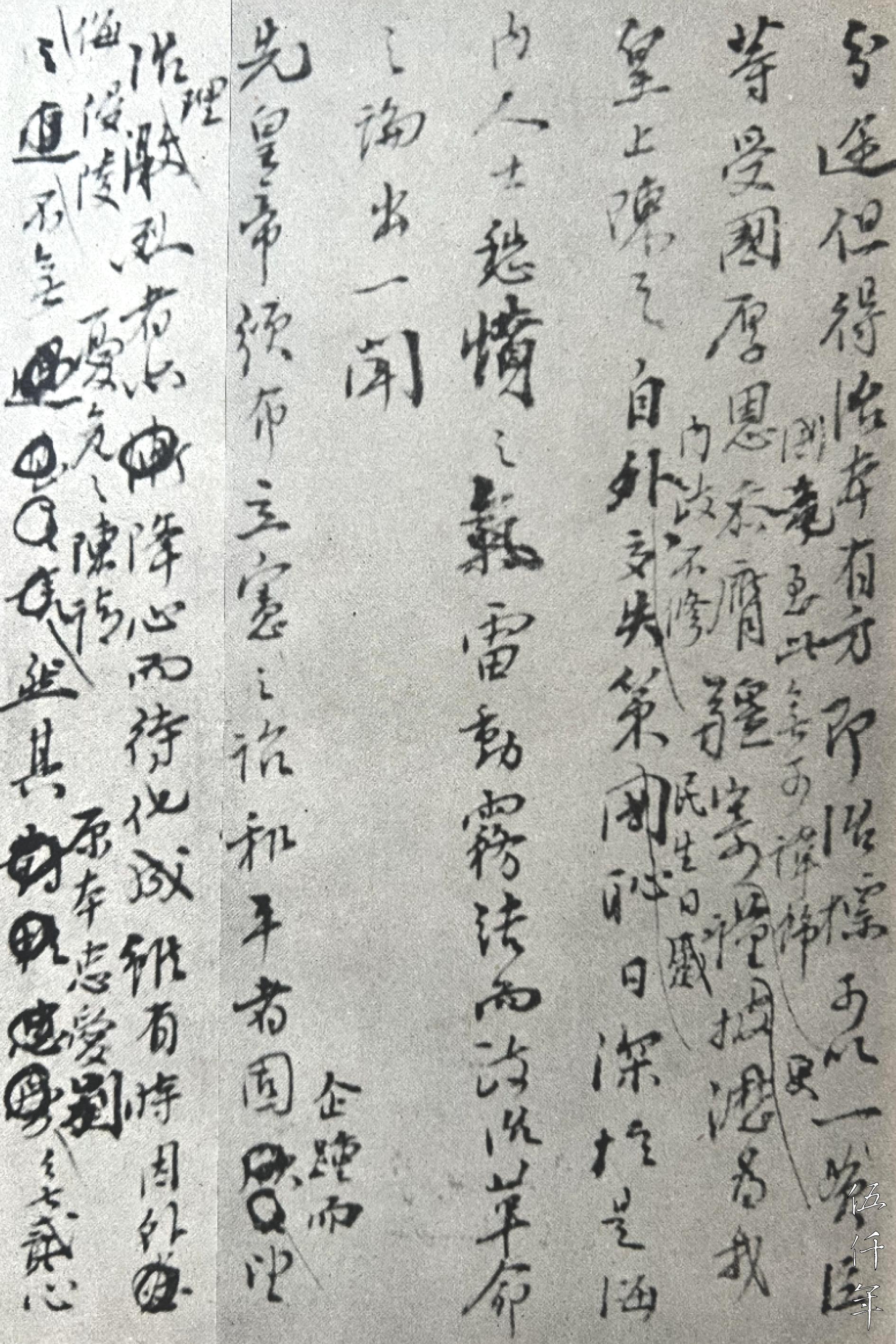

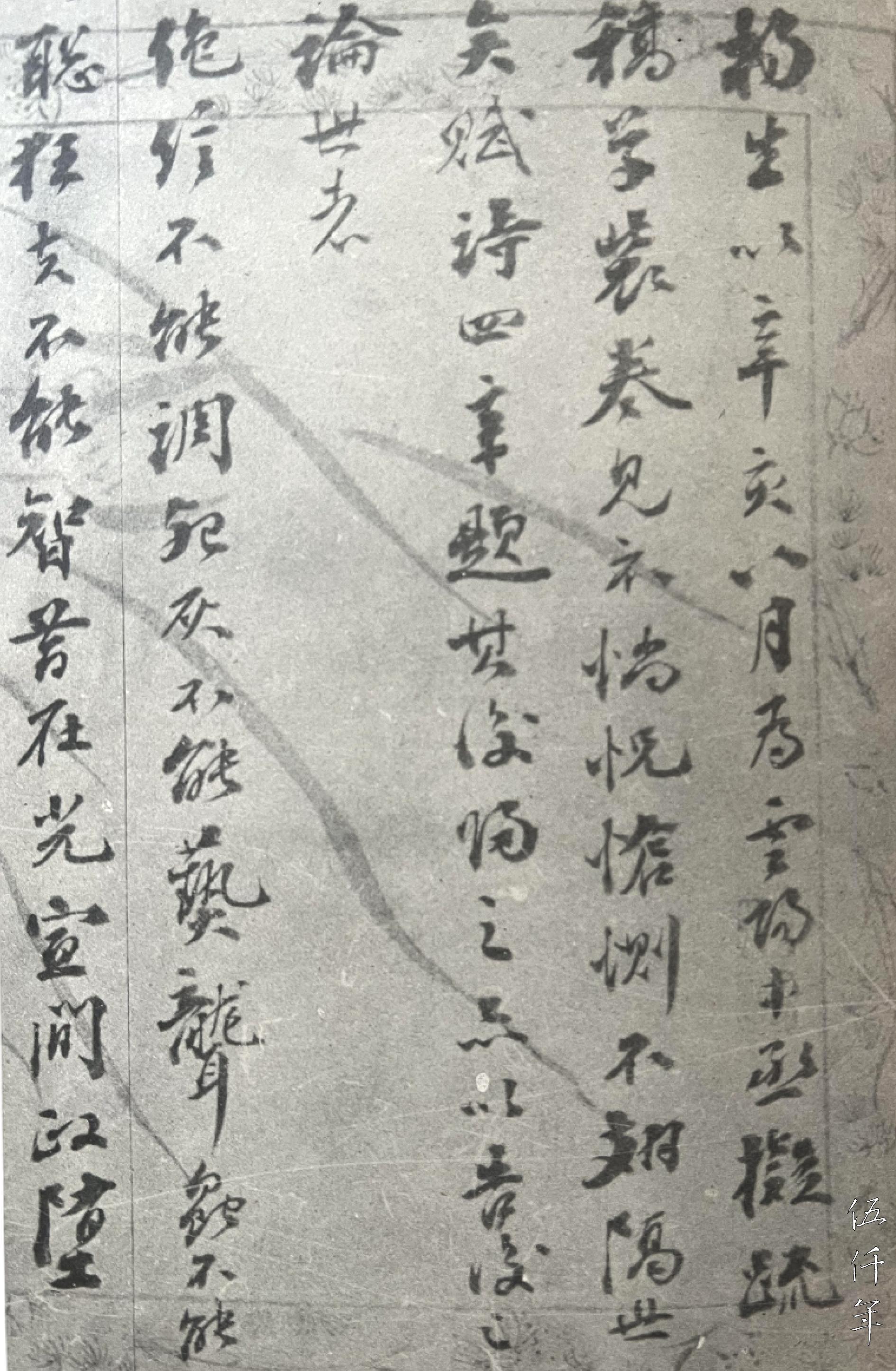

First section of inscription by Chang Chien

Chang Chien also inscribed some poems after Wu Hu-fan’s painting. The epigraph of the poems says:

“Mr. Yang showed me the handscroll of the memorial draft penned in August of hsin-hai year for the provincial governor from Yün-yang. It left me dazed and sorrowful, as if it was from another world! I wrote and appended four poems before returning it to him. They can inform future generations who wish to reflect on the world.”

Two of the poems lament his own failure after fourteen years in the constitutional movement.

Another section of inscription by Chang Chien

Snapped string cannot tune,

Dead ember cannot burn.

Deaf worm cannot hear,

Madman cannot think.

Kuang-hsü to Hsüan-t’ung,

Servile men to broken state.

Be it affair of crushing war,

Losses are just child’s play.

Shrieks call out the lofty sky,

Heaven too drunk to care.

A dopey drug for the dying,

In mayhem of upturned world.

A candle a thousand words,

Teardrops of bronze cast guard.

Rebuff Heaven and be rebuffed,

The mass did not follow through.

Long gone are enlightened kings,

Chance encounter of proper rule.

War rises from mighty rivers,

Angry words for incessant chaos.

Trampling done by hideous men,

Law and order turned to dust.

Despot can be pitiful too,

Brief gale over morning plant.

A moment of false repose,

That towns not perish in haste.

Though no haven is there to flee,

Follow the guileless ancient recluse.”

Chang Chien wrote these poems in 1915. He depicted the foolishness and folly of the Ch’ing court, and compared it to “dead ember” beyond redemption. He described the tumultuous events of the Hsin-hai Revolution, the Ch’ing court “Rebuffed Heaven and be rebuffed”. His own constitutional ideals had turned into yesterday’s withered flowers. By steadfastly adhering to his own principles and moving with the flow, could he hope to “Follow the guileless ancient recluse”. This poem was written after the failure of the Second Revolution, when Yüan Shih-k’ai attempted to revive the throne of monarchy for himself, and threw China into another major historic turning point. With an uncertain future fraught with perils, Chang Chien surveyed again the last memorial he wrote to the Ch’ing court four years ago, Memorial to Request the Reorganization of the Cabinet and to Implement the Constitution, and he was overcome by a multitude of emotions.

The Handscroll of Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night remained in the possession of the Yang family after the death of Yang Ting-tung. It was exhibited in Su-chou in 1936 at the Wu-chung Documentation Exhibition (吳中文獻展覽會) where it garnered significant attention. During the Japanese invasion of China, it was almost destroyed. Afterwards, it was tortuously taken to Boston in the United States by the Yang descendants, and nearly forgotten by the public. It was not until the 60th anniversary of the Hsin-hai Revolution in 1971 that Mr. Yang Chih-yu(楊之游), the eldest son of Yang Ting-tung, persuaded his stepmother living in the United States to bring the handscroll back to Taiwan, the Republic of China. It was then donated to the National Museum of History and exhibited in public. This drew widespread attention and brought to light an obscure and bizarre episode during the Hsin-hai Revolution. In response to public demand, Yang Chih-yu also consented to a request from the Kiangsu Documentation Society in Taipei (江蘇文獻社) and produced 500 facsimile copies of the handscroll in book form, which were shared with historians and enthusiasts.

View of Su-chou commercial centre near the north south city gate in early Republican era

The Wei-ying Inn where Chang Chien and others stayed at that time also has an interesting story. Towards the end of the Ch’ing dynasty, hotels were concentrated along Kuang-chi Road (廣濟路) in Su-chou City, with over a dozen different establishments and supported by more than 60 carriage services. Wei-ying Inn was situated next to Ch’ien-wan-li Bridge (錢萬里橋), and was categorized as one of the more upscale hotels. Despite being a Western-style hotel, it was founded by a Chinese proprietor named Sun Fu-t’ien (孫福田). He named his hotel “Village Inn” in English, which was translated into Chinese as “Wei-ying”. The architecture of Wei-ying Inn was a small two storey Western style building, boasting 28 elegant and spacious rooms, each equipped with balconies offering distant views of Shan-t’ang River (山塘河) and Tiger Hill Pagoda (虎丘塔). The hotel restaurant was well-equipped to serve both Chinese and Western food. Lawns surrounded the hotel, a small pavilion was located in the garden, numerous viewing rocks were displayed, the layout was tranquil and elegant, embodying the charm of Kiang-nan gardens.

Today, Wei-ying Inn has long vanished between the high-rise buildings and expressways of Su-chou. The only witness to that distant historic incident is the Handscroll of Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night in the National Museum of History of the Republic of China. The past has much to lament, the sorrow and helplessness of Chang Chien seem to have followed us. If the early Republican literary organization Southern Society (南社) represented the young generation of Kiang-nan intellectuals centered around Su-chou, then Chang Chien represented the middle-aged generation of intellectuals. The young generation from Southern Society believed in revolution, the middle-aged generation was inclined to be conservative, lending their support to constitutional monarchy, but ultimately threw in their lot with the revolution. It was a weighty change of direction with substantial responsibilities. These middle-aged intellectuals brought up by traditional Confucian education were loyal to the principles of social responsibility and benefit to all. However, their thoughts were also deeply rooted in the relationship between emperor and subject, which also constrained their actions. After petitioning the Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night, Chang Chien and his allies adapted to new ideas and changed their political stance. Not only did this lessen the resistance against independence in each province, but also amplified the momentum of revolution, isolating the Ch’ing government further, and helped the founding of the Republic of China.

Inscription by Wu Hui-yü on the Handscroll of Memorial Draft Penned in Autumn Night