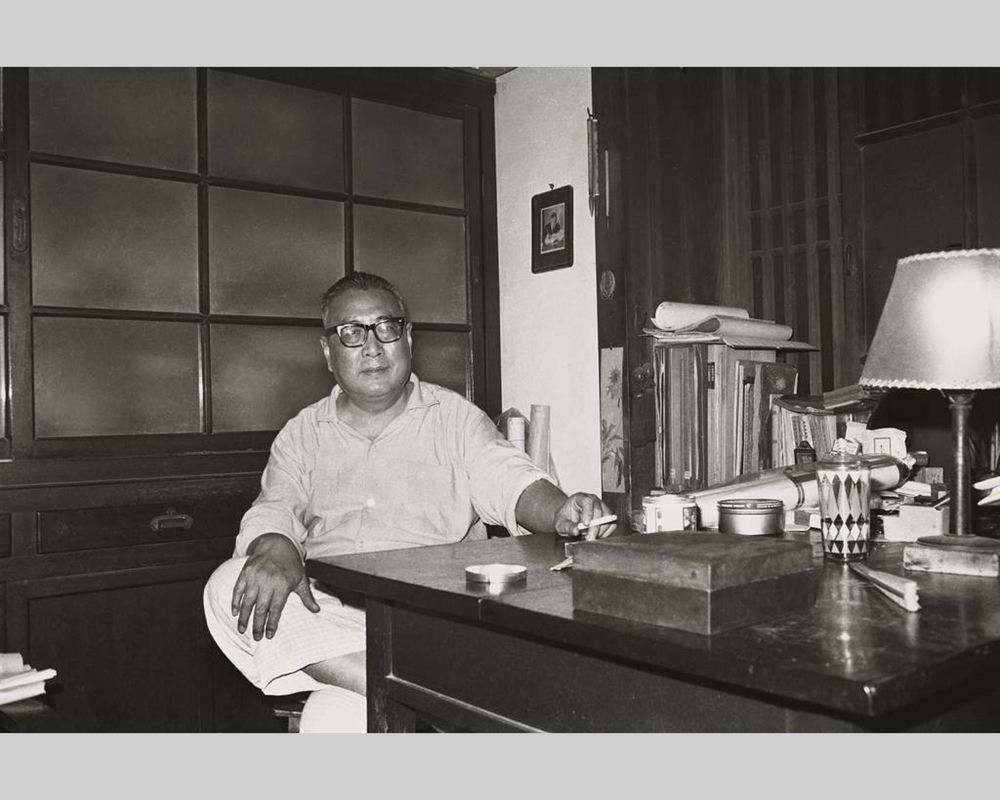

In the last few decades, the preeminent fan collector in Taiwan and overseas was Mr. Huang T’ien-ts’ai (黃天才). Most of his life’s work was news reportings. If we consider his experience in fan collecting and his world of connoisseurship, the only article he wrote on this subject is The Pleasure of Fan Collecting compiled in The Art of Fan, published by the National Museum of History in the 85th year of the Republic (1996). The transmission of cultural heritage has routinely depended on the instructions of connoisseurs, however it is certainly not easy to find one in our age. Hence this article by Mr. Huang T’ien-ts’ai is reissued here, just as though he is conversing in person. One thus hopes the refinement of fan collecting will not be lost with future generations.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

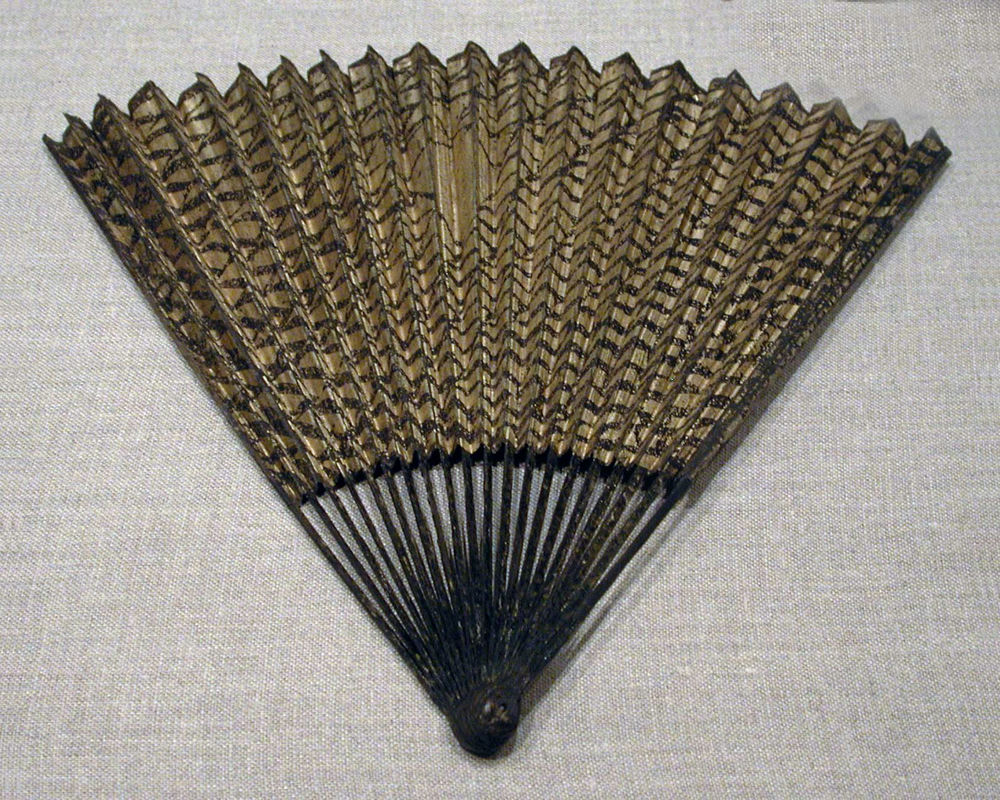

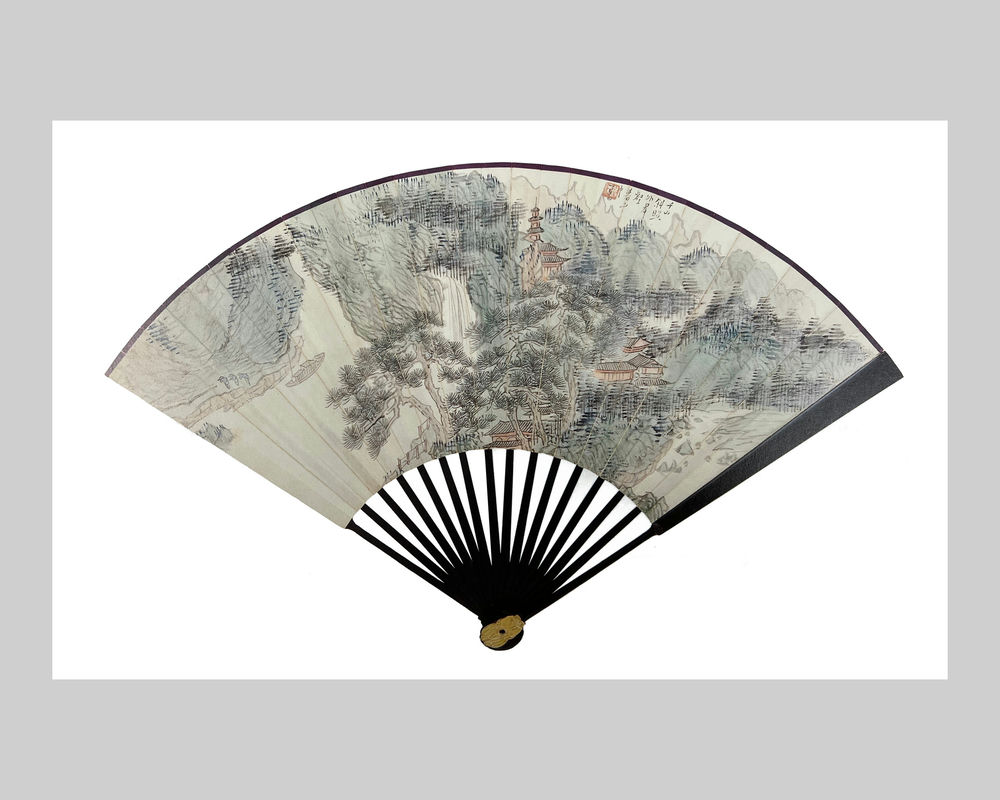

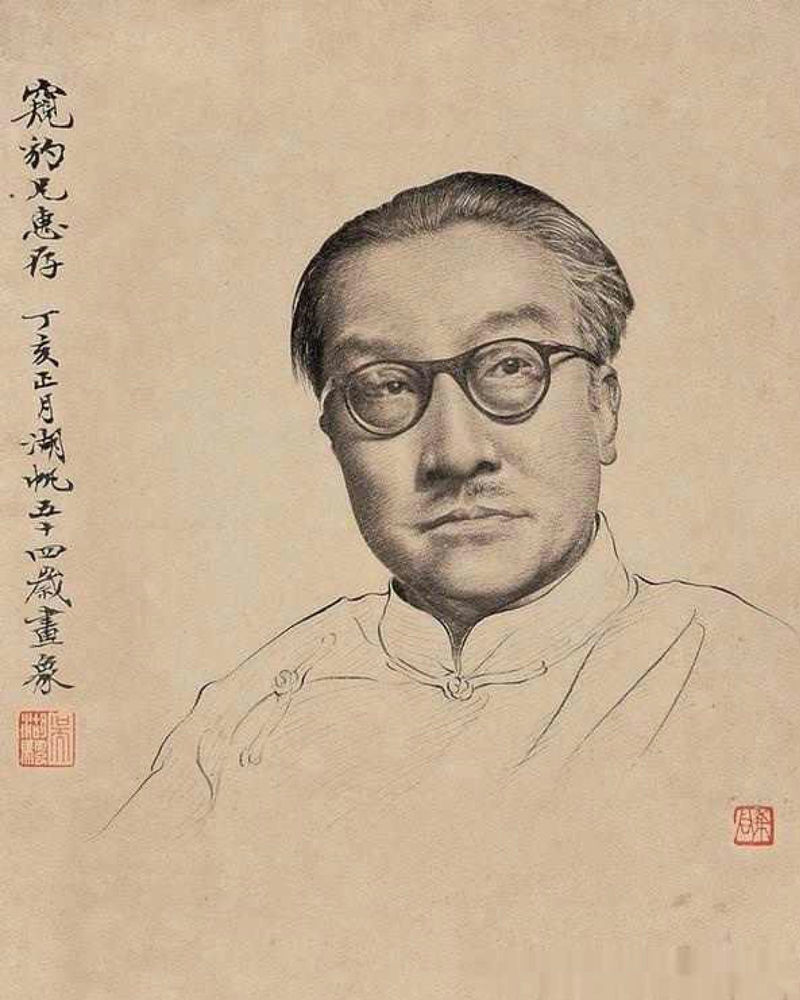

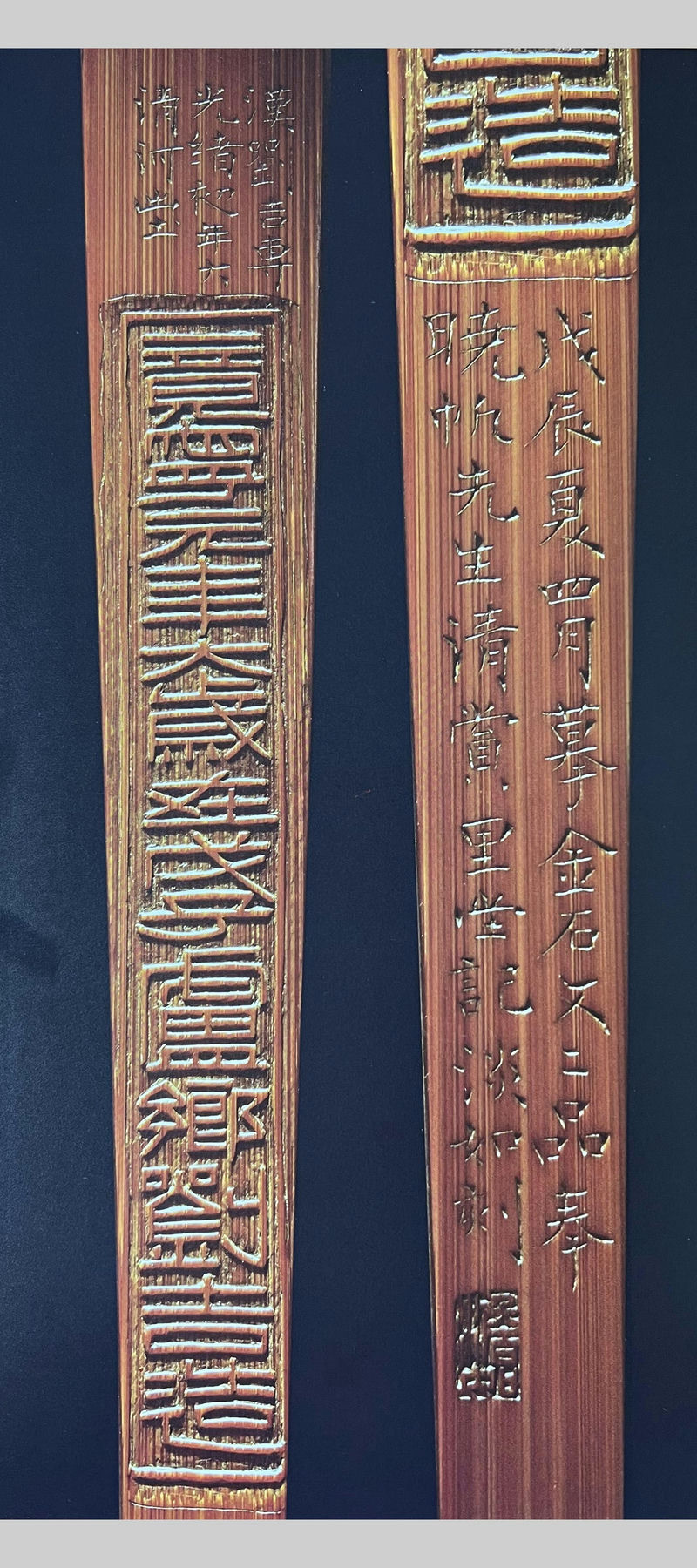

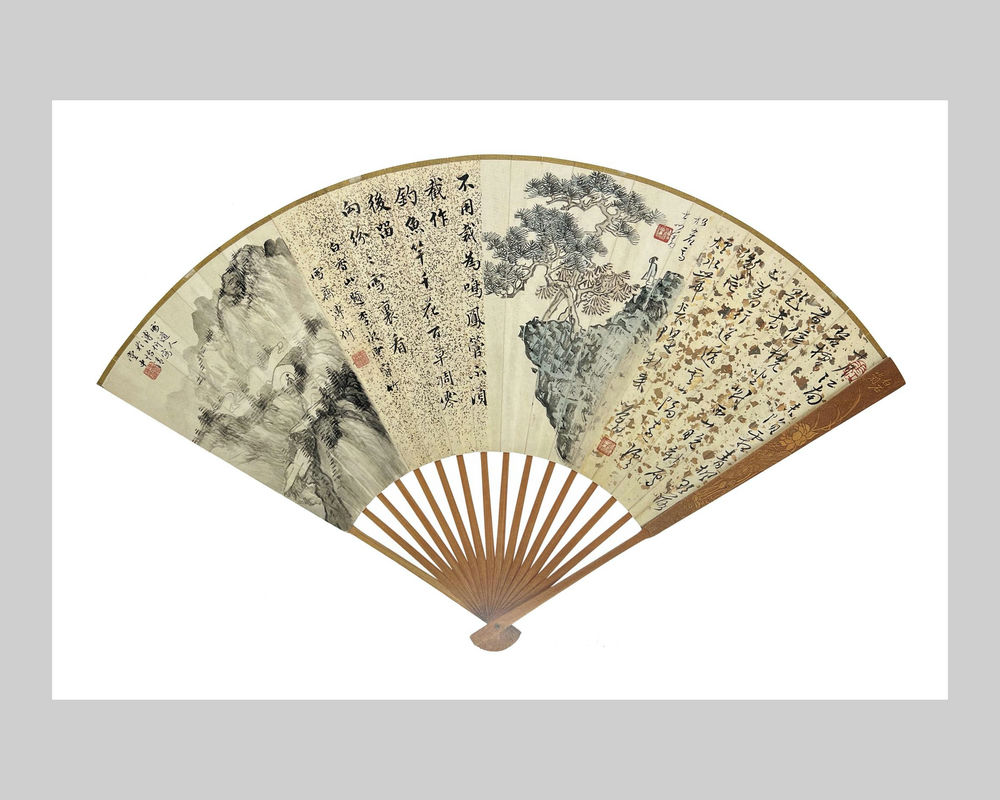

Folding fan impressed with seals by Chao Chih-ch’ien (趙之謙 1829-1884) in the collection of Ko Chang-ying (葛昌楹 1892-1963)

Fans have a long history in China, dating back at least three to four thousand years. However, the so-called “calligraphy and painting fans” commonly collected today are not the traditional ancient Chinese fans, but folding fans that were brought over from Japan and Korea. They became popular in China only in the last three to four hundred years.

Chinese culture is broad and profound, with far-reaching influence. Many cultural arts that originated in China, such as wei-ch’i (go), tea ceremony, and even the compass, declined gradually in China but became widely popular in foreign countries, undergoing further developments and improvements. Only two items that were introduced from foreign countries, the snuff bottle and the folding fan, became popular in China, where they flourished and even surpassed the original foreign products. These Chinese-made products were considered more superior and refined compared to those from their countries of origin.

A Ming dynasty fan. Photograph courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art

The folding fan was created by the Japanese based on the principle of bat wings’ opening and closing. According to historical records, it was introduced to China from Japan and Korea during the Northern Sung dynasty in late 11th century. Initially, only a very small number of folding fans were imported as gifts for enjoyment or as tribute items. They did not receive much attention. During the middle of the Ming dynasty, it is said that the emperor saw the tribute items, became interested and ordered the palace craftsmen to study and reproduce them. Through continuous improvement and refinement by Chinese artisans, folding fans became more practical, aesthetically pleasing, and lightweight. They gained widespread popularity among the upper-class and the literati in China. From the middle of the Ch’ing dynasty onwards, the art of making folding fans reached its pinnacle. The materials and techniques used for making fans underwent continuous innovation and development. The end-products were diverse and extraordinarily beautiful. Most remarkable was the involvement of literati and painters in their production. They transferred the traditional arts of literati painting, calligraphy, and inscribed poems on round fan onto the delicate surface of the folding fan. Hence the folding fan, originally designed for practical convenience, evolved into a refined work of art that embraced multiple artistic creations. From the middle of the Ch’ing dynasty to the early years of the Republic of China during the 1930s, almost every well-known painter and calligrapher had painted and inscribed a folding fan. Even though electric fans and air conditioners became more common, the habit of carrying a folding fan persisted amongst the upper-class. By then, the folding fan has so developed that its artistic value surpassed its practical value.

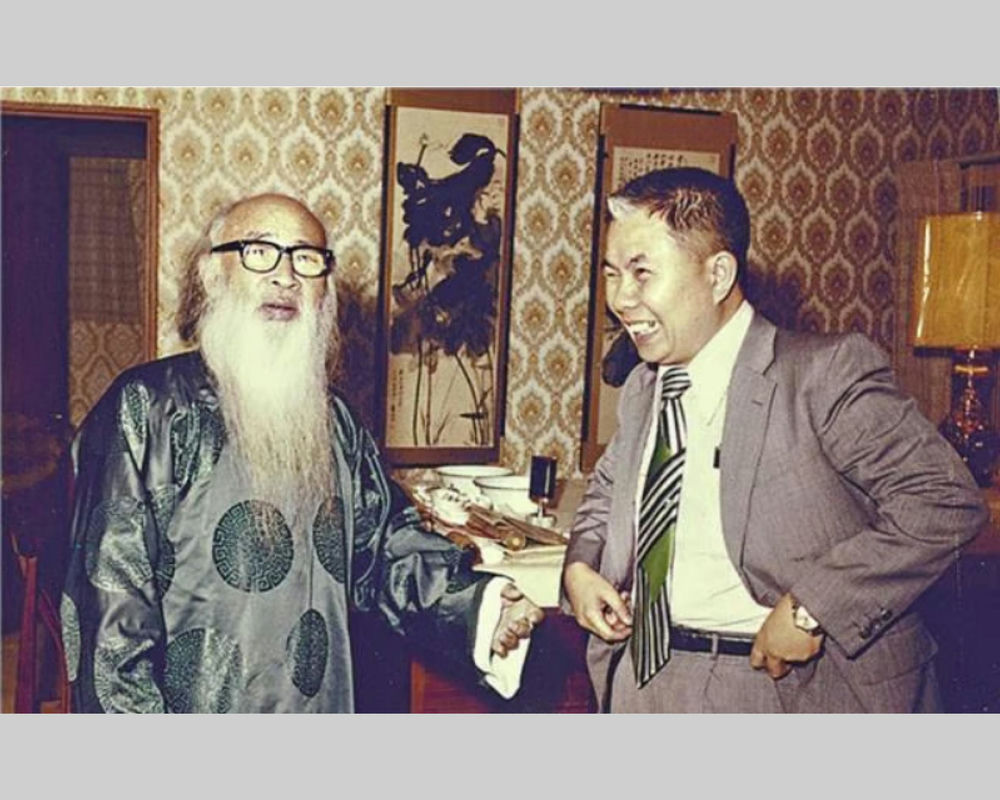

Mr. Huang T’ien-ts’ai (黃天才先生) with his collection of Chung K’uei (鍾馗 Taoist Deity) fans

Regarding my special fondness for collecting folding fans rather than other cultural artefacts, the reason is actually rather coincidental. Basically, my primary interest in Chinese cultural artefacts is calligraphy and painting. Therefore, during the early years when I ventured into collecting cultural artefacts, I collected hanging scrolls, hand scrolls, albums and separate leaves. Folding fans with calligraphy and paintings naturally became part of my collection as well. About thirty years ago, during the tumultuous period of the Cultural Revolution in mainland China in the late 1960s to early 1970s, I happened to be stationed in Japan as a special correspondent for the Central Daily News (中央日報) in Taipei. In that period, I had the opportunity to come across a huge number of Chinese calligraphy and paintings sold in Japan by the Chinese communists. Among them, the folding fans left a particularly deep impression on me, as the sheer quantity was truly beyond imagination. I remember in the spring of 1968, I accompanied Mr. Chang Dai-chien (張大千) to Fukuoka, Kyushu, to visit the president of a Japanese calligraphy association. The president led us to a large warehouse filled with Chinese calligraphy, where there were two large bamboo baskets each as tall as a person filled chaotically with old folding fans. Apparently there were more than 2,000 fans. On another occasion, a Tokyo gallery specializing in Chinese calligraphy and paintings informed me that they had received a shipping container full of old Chinese folding fans. Several boxes were in the warehouse of their retail store. I hurried over to take a look. Indeed, I saw a number of large wooden crates, each as tall as a person, and each containing at least 500 to 600 fans.

Under such unique circumstance, to the best of my personal financial ability, I gradually acquired over 700 calligraphy and painting fans that I liked.

At one point, I even considered setting a goal of acquiring 1,000 fans. Once I reach that number, I would gradually replace and exchange them as necessary. With this goal in mind, I believed that one day I would become one of the collectors with the largest number of highest-quality folding fans. During that period, I focused exclusively on collecting folding fans with calligraphy and painting, leaving aside all other cultural artefacts.

In early November in the 72nd year of the Republic (1983), during a visit to Tokyo by Mr. Ho Hao-t’ien (何浩天), the former director of the National Museum of History in Taipei, and Mr. Yao Meng-ku (姚夢谷), the renowned calligraphy and painting master, I mentioned my Thousand Fans Collection project during a discussion. Mr. Ho enthusiastically encouraged me and said that when I achieve this goal of acquiring a thousand fans, the National Museum of History would organize a Thousand Fans Exhibition for me. I was thrilled by the prospect.

Unexpectedly, in spring the following year (the 73rd year of the Republic of China), Mr. Ho suddenly called me by long distance international phone to inform me that the National Museum of History had decided to hold an unprecedented Thousand Fans Exhibition on 20 May. All the fans were to be “folding fans” mounted on fan sticks. If my personal collection was not enough, I could invite other fan collectors to participate and contribute to the event. Some domestic collectors were also willing to offer their collections. Mr. Ho considered me to be the premium collector of folding fans and entrusted me with the task of assembling the exhibition. He urged me to invite more fan collectors to participate with their collections, as to select the best pieces, and to achieve the ideal of both quantity and quality.

I immediately started to work after accepting the assignment. By contacting several other fellow collectors that I knew, the results greatly exceeded my expectations. In the Tokyo-Yokohama area alone, there were four or five friends who each had 300 to 400 folding fans; with Mr. Wang Hsiang-lung (王翔龍) of Yokohama owning over 700 folding fans, a quantity which was comparable to mine. All the collector friends were willing to offer their collections for the exhibition.

I invited those friends who had the greatest number of fans in their collections to a meeting. To achieve the goal of collaboration and to select the best pieces for the exhibition, the five of us living in the Tokyo-Yokohama area would each select 200 of his finest folding fans to participate. I informed Director Ho in Taipei about the progress of assembling the exhibits and he was pleasantly surprised by how smooth it went. He immediately arranged for the transportation of the exhibits to Taipei.

During the organization process, Dr. Chang Hsin-pai (張心白), a fellow fan collector in Taipei and a dentist by profession, actively expressed his wish to provide 200 folding fans for the exhibition. Coincidentally, Mr. Lu from Tokyo stored his collection in the United States, making it difficult to transport. Accordingly it was decided that Dr. Chang Hsin-pai’s collection would be in the exhibition instead.

On 20 May, the grand opening of the Thousand Fans Exhibition took place. The National Gallery in the National Museum of History in Taipei was adorned from wall-to-wall by glass display cases showcasing a sea of fans. The event was unprecedented and sensational.

The exhibition was a great success, and the National Museum of History awarded me a certificate of recognition. However, the insights I gained from assisting the organization of this exhibition led me to completely revise the original plan for my fan collection.

First of all, I decided to abandon the original plan for the Thousand Fans Collection. At that time, the quantity of fans in a collection held little meaning. Anyone with sufficient financial resources could easily become the owner of a “thousand fans” without much effort. As for the “quality” of the fans collected, this is subjective, and there is no standard to gauge what is good or bad. This was evident in the Thousand Fans Exhibition itself, where five well-known fan collectors each selected 200 “masterpieces” to exhibit. The fans were haphazardly displayed together, creating a lively atmosphere but lacking any order or system. The visitors had no idea of the significance of the exhibition and remained oblivious to the so-called “fan culture” that held an important place in our cultural life in the last four centuries.

As a result, I made another important decision: henceforth, the selection of fans should not be aimless and random. At the very least, the criteria of selection should adhere to several important characteristics of “fan culture” or “fan art”:

First, the “folding fan” is an integrated piece of artwork that is distinct from a piece of calligraphy or painting. It is also different from a fan that has been detached from the fan sticks and mounted as a leaf. The term “folding fan” refers to a fan that remains attached to the fan sticks. A perfect specimen of a folding fan needs to have fan guards that are noteworthy, whether they are made of special materials, or exhibit fine workmanship, or feature exquisite engravings on the guards. Collecting folding fans but neglecting to appreciate the art on the fan guards would be a major oversight.

Folding fan with painting of pheasants by Chou Chih-mien (周之冕) of the Ming dynasty. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

Second, the popularity of folding fans emerged in China only after the middle of the Ming dynasty, which was just about four hundred years ago. (In fact, with material progress of our society and improvement of people's living standards, electric fans and air conditioners became increasingly common, fewer people use folding fans in the last fifty years. The vogue for folding fans lasted for a period of just over three hundred years.) Still, the large quantity of fans that have survived is testament to how deeply the fan penetrated daily life, to the point where “one fan per person” would be an inadequate description of their prevalence. Therefore, the calligraphy and paintings on fans did not necessarily have to be the works of renowned artists. Some people, due to their special status or special circumstances, may have written or painted on fans as gifts. The significance of the calligraphy and paintings on these fans does not lie in purely artistic appreciation. For this type of fans, we should not ignore them simply because they may lack high artistic value.

Third, I plan to categorize and preserve folding fans according to their diverse contents, backgrounds and functions, thus establishing a collection system for “fan culture”. This led to the concept of “thematic fan collection”.

I started to organize the fans in my own collection based on the several aforementioned artistic features.

Using my collection of over 700 fans as basis, I divided them into more than ten categories. Then, I eliminated nearly half of them that were repetitive in nature or lacked outstanding features.

My classification is primarily based on the “content” of the calligraphy or paintings on the fan face, such as landscape, flower and bird, human figure, calligraphy and so on. However, I encountered several almost insurmountable “exceptions” that caused me great difficulty, and in the end, I had to find alternative ways to handle them.

Portrait of Shen Yin-mo (沈尹默)

Folding fan with running and cursive script calligraphy by Shen Yin-mo (沈尹默)

The first “exception” is that almost all folding fans of calligraphy and painting are uniform in presentation, with one side featuring calligraphy and the other side featuring painting. Therefore, each fan encounters a dilemma with categorization: should it be classified according to the painting or the calligraphy? In response, I can only find a compromise. I prioritize fans that have exceptionally outstanding calligraphy (such as a copy of the text on the bronze vessel Mao-kung-ting 毛公鼎 by the renowned calligrapher Shen Tseng-chih 沈曾植 1850-1922, who was famous for his calligraphy in early cursive script), or fans that are exceptionally rare (such as by Kang You-wei 康有為 1858-1927, who disliked writing on fans; his price list for calligraphy in Shanghai specifically stated “No calligraphy on fan”). For calligraphers of outstanding reputation (such as Tan Yen-kai 譚延闓 1880-1930, Yü Yu-ren 于右任 1879-1964, Shen Yin-mo 沈尹默 1883-1971, et cetera), it is obvious that their calligraphy is the priority and their fans are included in the “calligraphy” category. Generally, fans are classified according to the subject of the painting. However, when encountering fans combining calligraphers and painters who were evenly matched in reputation and content (which mostly happens as usually the calligraphers and painters would be of equal status and indeed this was an essential criteria for making calligraphy and painting fans), such as “Southerner Chang (Dai-chien) 1899-1983, Northerner P'u Ju 1896-1963” (南張,大千,北溥,儒). Then it becomes challenging to classify them. It is inevitable that trade-offs will have to be made in such cases.

The second “exception” is that there are a number of fans that stand out due to their historic epochs, such as folding fans from the Ming dynasty or the early Ch’ing dynasty (the reign of Ch’ien-lung, 乾隆 and the reign of Chia-ch’ing 嘉慶). Or fans created by individuals of special status, such as fans by members of Li-yüan (梨園 Opera Community) like the Peking Opera singer Mei Lan-fang 梅蘭芳 and others. These fans are picked out from the general calligraphy and painting categories and classified separately as Ming dynasty Fans, Ch’ing dynasty Fans, or Li-yüan Opera Community Fans.

Portrait of Chin Hsi-ya (金西厓)

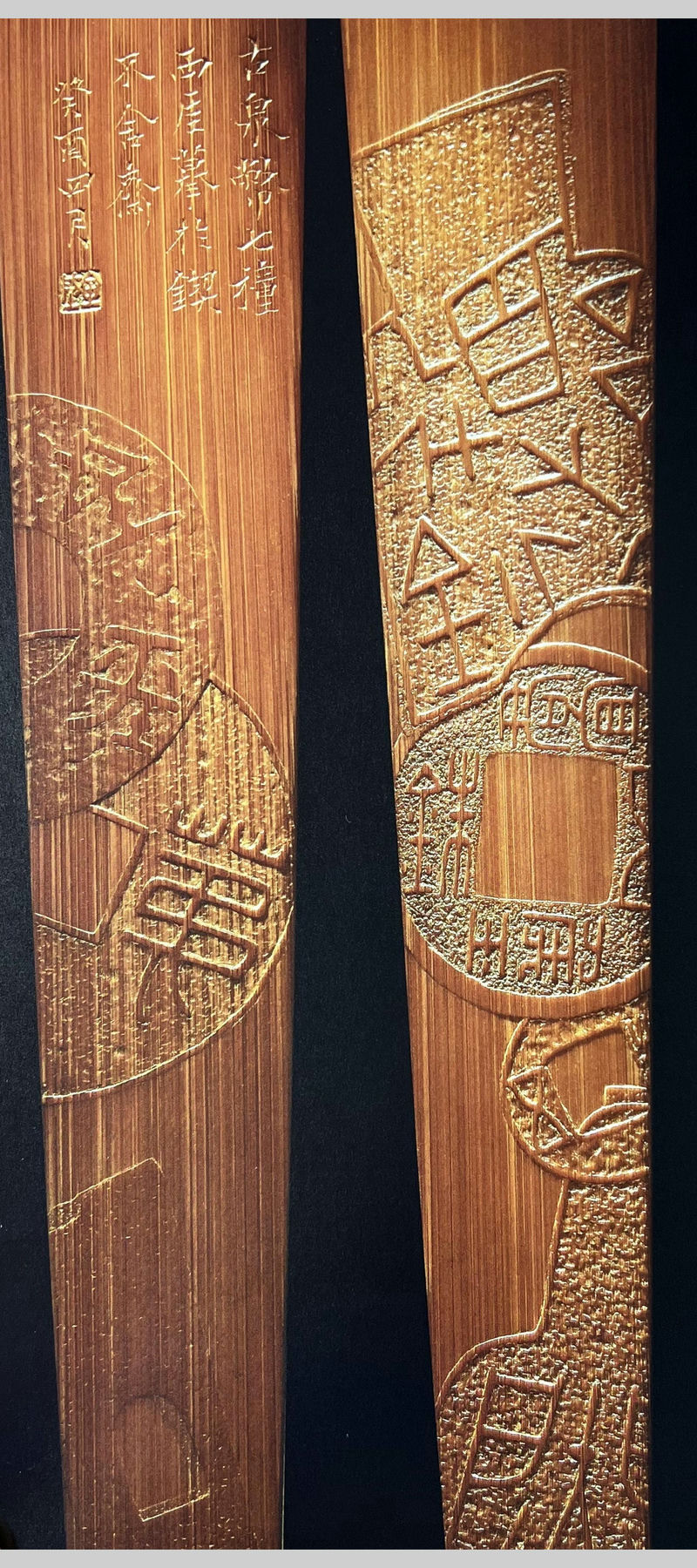

Bamboo fan guards carved by Chin Hsi-ya (金西厓). Photograph courtesy Mr. Kuo Hai

The third “exception” is that in order to highlight the uniqueness of folding fan, I place special importance to the fan guards. The fans in my collection all have good fan guards. However, I have nearly 20 fans where the calligraphy and paintings are ordinary, but their fan guards are very beautiful or special. Therefore, in my classification, there is a category for Exquisite Fan Guards. These 20 fans are selected on the basis of their fan guards, some because of special materials, some for exquisite engravings, and others for exceptional craftsmanship. When people see these fan guards, they will realize that the fan guards of folding fans can be artworks themselves, and the artistic values of the fans do not need to rely on the calligraphy and paintings on the fan faces.

Apart from the three aforementioned “exceptions”, there are several other minor exceptions that I will discuss later when I give examples of the thematic fan collection projects.

Of course, collecting folding fans by category is a troublesome task. However, if past practice or the common practice of current collectors is followed, which is to only collect fans created by famous artists or fans that appeal personally to us, the result is that inevitably many remarkable aspects of fan art would be overlooked. I don't “unrealistically expect” every fan collector to engage in “comprehensive collecting”, but I believe that in each generation, there should be at least one or two collectors who preserve the complete cultural landscape of the folding fan. Hopefully, the folding fan which once had significant cultural importance in Chinese lives in the past can be preserved and passed down.

Below I will give a brief overview of my specialized fan collection:

Ming Dynasty Fans

Ming dynasty folding fans are not commonly seen, after all Ming dynasty ended three to four hundred years ago. I have only one fan from the Ming dynasty. It was painted by the famous calligrapher and painter Wang Chien-chang (王建章) in the 5th year of the Ch’ung-chen reign (1632). It features a golden fan face with ink landscape painting on both sides. This fan was originally owned by Mr. Hsü Chi-ch’uan (許姬傳), the secretary of the famous Peking Opera singer Mei Lan-fang (梅蘭芳). Around seventeen or eighteen years ago, shortly after the Cultural Revolution subsided in mainland China, an overseas Chinese friend in Tokyo happened to visit relatives in Peking and he was entrusted by Mr. Hsü to bring this fan to Tokyo for sale. That was how I purchased it. When I first acquired it, the fan face was fractured into three pieces. I had it carefully repaired by the Japanese expert repairer, Meguro Sanji (目黑三次 owner of Kōkakudo Meguro 黃鶴堂), before it could be restored to its original appearance.

Portrait of Emperor Hsüan-te (宣宗 1399-1435) of the Ming dynasty

Folding fan with painting of flora and fauna by Emperor Hsüan-te (宣宗) of the Ming dynasty. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

The fan guards of this fan are of high-quality water-milled bamboo. The surface is plain without engraving, the craftsmanship refined and naturally pleasing. Especially noteworthy is its age of over three hundred and sixty years. After being well worn by time, the bamboo surface is incredibly smooth, reflecting light and enhancing its antique charm.

Folding fan with painting by Tung Ch’i-ch’ang (1555-1636) of the Ming dynasty. photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

Ch’ing Dynasty Fans

Folding fans became most popular from the middle of the Ch’ing dynasty, with many surviving examples. Especially as there were numerous renowned calligraphers and painters during the late Ch’ing period, and the era is relatively close to the present time, many exquisite and well-preserved late Ch’ing folding fans have been passed down.

When I refer to Ch’ing Dynasty Fans, I mean folding fans with calligraphy and painting created by artists who passed away before the founding of the Republic of China (1912 AD). The term “Respected Elders of the Ch’ing dynasty” (refer to Ch’ing dynasty officials and artists who were still alive after the establishment of the Republic of China) such as Shen Tseng-chih (沈曾植 1850-1922), Li Jui-ch’ing (李瑞清 1867-1920), Tseng Hsi (曾熙 1861-1930), and others; their works are not included in the category of Ch’ing dynasty Fans.

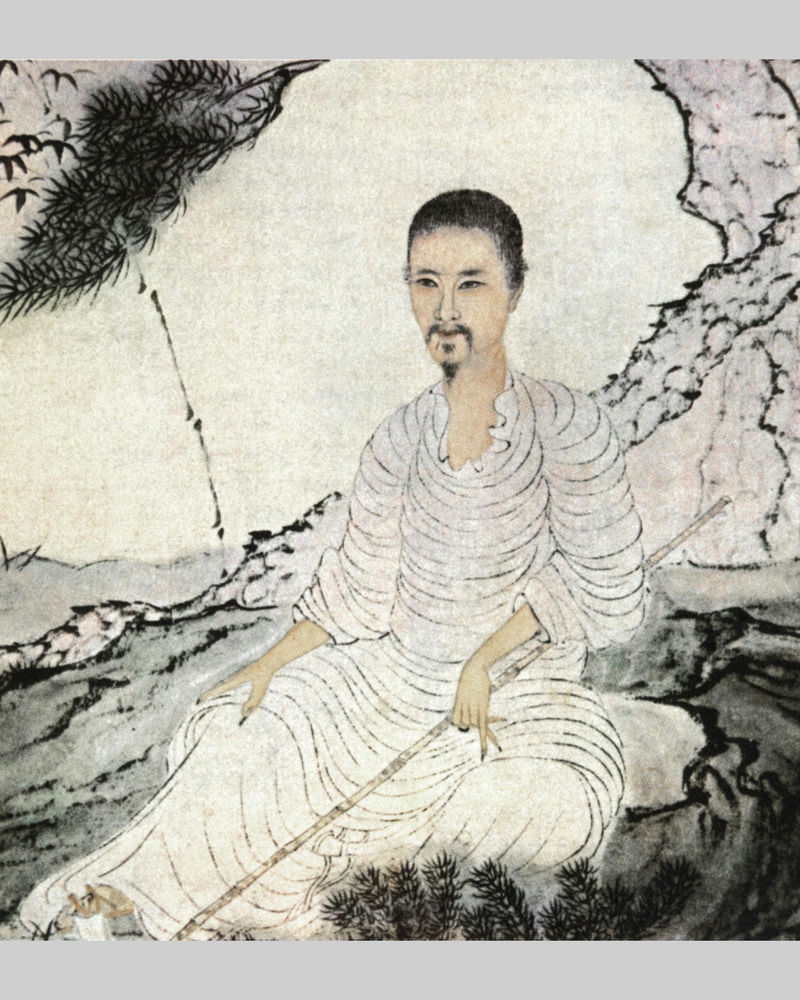

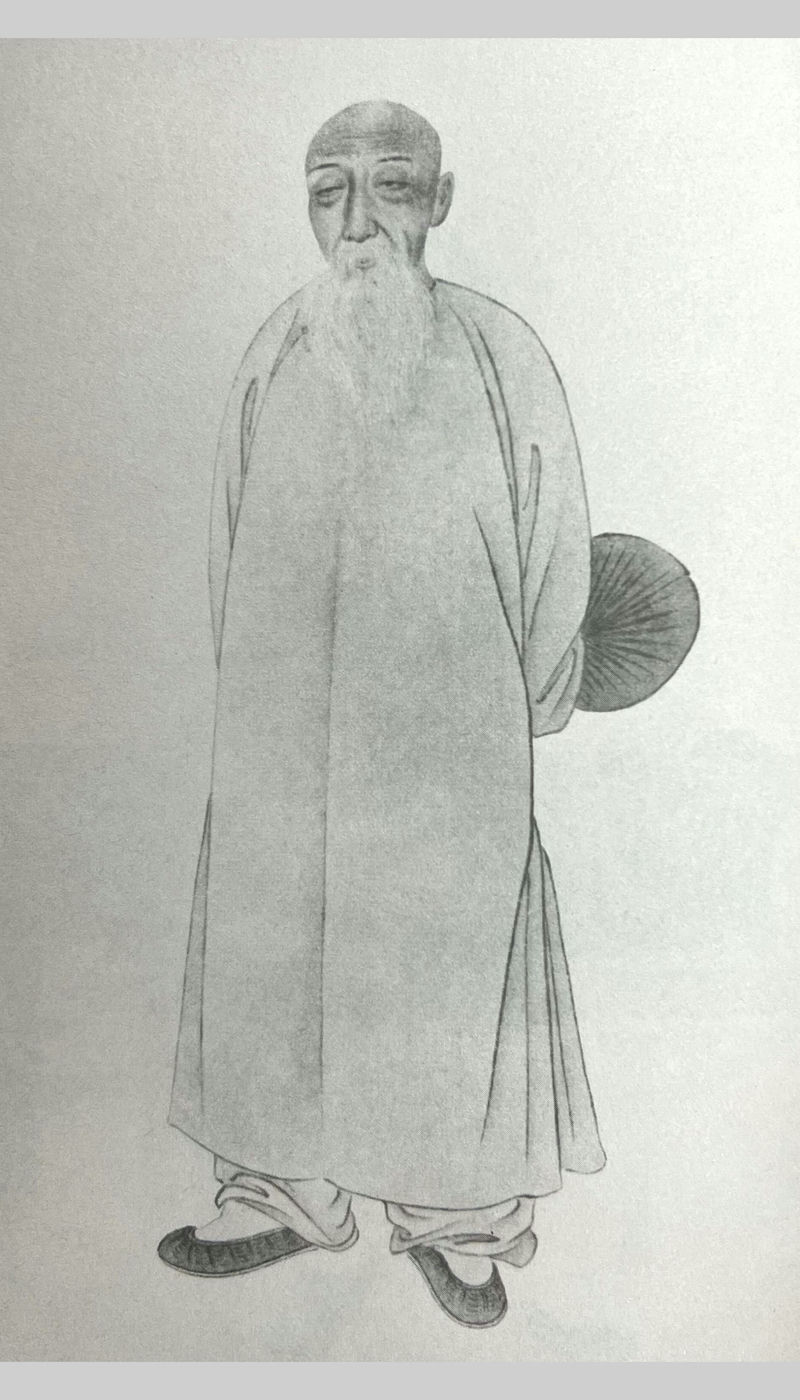

Portrait of Shih T’ao (石濤 1642-1707) of the Ch’ing dynasty

Folding fan with painting of narcissus by Shih T’ao (石濤) of the Ch’ing dynasty

Among the over twenty Ch’ing dynasty fans in my collection, the rarest ones are two fans from the Ch’ien-lung reign. One is a calligraphy and painting fan which is a collaboration between P’an Kung-shou (潘恭壽 1741-1794) and Wang Wen-chih (王文治 1730-1802). “P’an Inscription Wang Painting” has always been highly valued in the collecting community, and their joint work on a folding fan is exceptionally hard to come by. (I acquired this fan the year before last in 1994 at the auction of cultural artefacts from Ting-yüan Studio 定遠齋 belonging to Marshal Chang Hsüeh-liang 張學良) The other fan is a work by Hsi Kang (奚岡 1746-1803), with both calligraphy and painting done by him in the 54th year of Ch’ien- lung (1789).

Folding fan with calligraphy by Wang Wen-chih (王文治) and painting by P’an K’ung-shou (潘恭壽) of the Ch’ing dynasty. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

One characteristic of calligraphy and painting fans of the Ch’ing dynasty is that the creators were not necessarily acknowledged artists. Members of the imperial family (including the emperor himself) and high-ranking officials often presented their own calligraphy and painting fans as rewards or gifts to subordinates and friendly colleagues. Such works, which are valued because of the importance of the persons behind the fans, carry historical importance and significance. I have an elegant fan by Empress Dowager Tz’u-hsi (慈禧太后) done in the 19th year of Kuang-hsü reign (1893), featuring subtle purple wisteria flowers with the inscription Ts’ai-chui-tiao-yen (綵綴雕檐), signed “Mid-April of kuei-ssu year in the reign of Kuang-hsü, by Imperial brush (光緒癸已孟夏中浣御筆) , with the seal impression “Treasure of Empress Dowager Tz’u-hsi (慈禧皇太后之寶)” . On the other side is regular script calligraphy by the renowned Hanlin Academician Chang Pai-hsi (張百熙 1847-1907). This fan was created in kuei-ssu year of the Kuang-hsü reign, just a year before the First Sino-Japanese War. At the age of fifty-nine, Empress Dowager Tz’u-hsi was in good spirit, preparing for the grand celebration of her sixtieth birthday in the following year.

In addition, among these “valued because of the person” fans, there are some rare treasures, such as calligraphy by Tseng Kuo-chuan (曾國荃 1824-1890, the ninth brother of Tseng Kuo-fan 曾國藩 1811-1872) and coloured peonies by P’eng Yü-lin (彭玉麟 1817-1890). As for the fan with calligraphy and painting by Weng Tung-ho (翁同龢 1830-1904, who held the honour of being chuang-yüan or principal graduate 狀元 and Grand Councilor 宰相), as well as being the Emperor’s tutor, it is highly regarded not just because of his high-ranking position, Weng's calligraphy itself is recognized to possess high artistic acclaim.

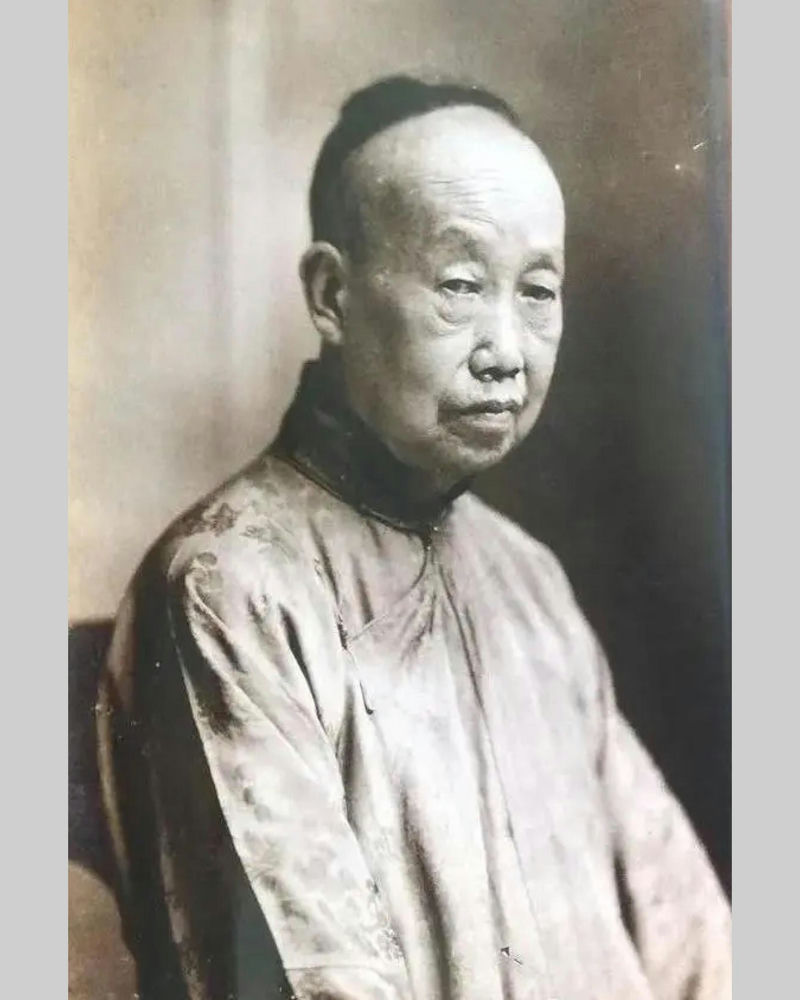

Portrait of Weng T’ung-ho (翁同龢) of the Ch’ing dynasty

Folding fan with running script calligraphy by Weng T’ung-ho (翁同龢) of the Ch’ing dynasty

Amongst Ch’ing dynasty fans, the Principal Graduate Fans (狀元扇) is often a notable item. Ch’ing dynasty lasted 267 years (1644-1911) and produced 114 chuang-yüan or principal graduates. In the time of imperial examinations, being a principal graduate was the highest honour, indicating a profound knowledge in literature and classics, with a certain level of calligraphic skill. Hence I once tried to collect fans by principal graduates. However, despite more than a decade of effort, the results are not satisfactory. Firstly, there are not that many fans by principal graduates in existence (it is said that six or seven decades ago, the renowned Shanghai collector Wu Hu-fan 吳湖帆 also endeavored to collect fans by principal graduate. After decades of effort, he only collected seventy-odd folding fans.) Secondly, among the over one hundred principal graduates of the Ch’ing dynasty, apart from a dozen well-known individuals from the late Ch’ing period, such as Weng Tung-ho (翁同龢), Chang Chih-wan (張之萬 1811-1897), Lu Jun-hsiang (陸潤祥 1841-1915), Chang Chien (張謇 1853-1926), and Liu Ch’un-lin (劉春霖 1872-1944), most of them are not well known and their calligraphy and paintings are not outstanding enough to warrant extensive collecting efforts. I have one fan with calligraphy by Hung Chün (洪鈞 1839-1893) who was also one of the well-known principal graduates of late Ch’ing. However, today almost no one knows who Hung Chün is. A few years ago a Taiwanese television station aired the drama series Sai-chin-hua (賽金花). When I introduced Hung Chün's calligraphy fan to people, I had to explain: “This is the fan of the husband of Sai-chin-hua (賽金花), principal graduate Hung (洪狀元)!” Only then were people interested to see Hung Chün’s calligraphy. It is astonishing that the name of principal graduate Hung has to rely on his association with Sai-chin-hua to gain recognition. This is far from what the noble and high-ranking officials of that era could have imagined!

Since folding fans were popular in the Ch’ing dynasty, detailed attention was paid to both the material and the craftsmanship of the fan frames. Diverse materials were used, such as bamboo, wood, ivory, lacquer and tortoiseshell, resulting in a wide variety of choices. Engravings on fan guards became ever more breathtaking, many renowned masters who specialized in this art form appeared. It is particularly remarkable that due to prevailing fashion, many master seal engravers also frequently engraved fan guards. I have collected many fan guards engraved by famous seal engravers such as Yang Hsieh (楊澥 1781-1850), Chen Hung-shou (陳鴻壽 1768-1822), Chao Tz’u-hsien (趙次閑 1781-1860), Hsü San-keng (徐三庚 1826-1890), Wu Ta-ch’eng (吳大澂 1835-1902), and others. There is a set of fan guards engraved with calligraphy and painting by Cheng Hsieh (鄭燮 1693-1766). One guard depicts two bamboo stems with three to five scattered bamboo leaves, while the other guard has an engraved poem:

“One, two, three bamboo stems,

four, five, six bamboo leaves,

naturally sparse and light,

no need for excessive layers.”

It was signed: “Pan-ch’iao Tao-jen Cheng Hsieh (板橋道人鄭燮)”. There is an intaglio seal: “Pan-ch’iao (板橋)”. The calligraphy and painting are both excellent, and the engraving is also exceptional. Although it is evident that it was created by skilled hands, there is no seal of the bamboo engraver. According to historical records, Cheng Hsieh and the bamboo engraver P'an Hsi-feng (潘西鳳 1736-1795) often collaborated on fan guards. It is possible that this is a collaborative work between Cheng and P’an. If this can be authenticated by experts, it would truly be a rare artistic treasure.

Calligraphy Fans

In my collection of fans, calligraphy is an important category. This is because calligraphy is a form of art unique to China and deserves special attention. Another reason is that typically for folding fans with calligraphy and painting, there would be a painting on one side and calligraphy on the other. I have nearly 300 fans in my collection, which means I have nearly 300 calligraphy fan faces. Such a large number of calligraphy works naturally includes many masterpieces.

Portrait of Wu Jang-chih (吳讓之) of the Ch’ing dynasty

Folding fan with running script calligraphy by Wu Jang-chih (吳讓之) of the Ch’ing dynasty

Due to the importance placed on calligraphy, I adhere to the principle of “calligraphy first” when categorizing my fan collection. For a folding fan, if the calligraphy side is by a renowned master or possesses certain representative qualities, then regardless of the subject matter on the other side, be it landscape, flowers, or figures, I classify it under the “calligraphy category”. Hence, the calligraphy in my fan collection spans from late Ch’ing, to early Republic, and to the present. There are all kinds of calligraphic scripts, such as seal script (篆), clerical script (隸), regular script (楷), running script (行), cursive script (草), as well as different styles of calligraphy such as oracle bone (甲骨), stone drum (石鼓), bronze inscription (鐘鼎), early cursive (章草), and slender gold (瘦金). Overall, it is quite comprehensive.

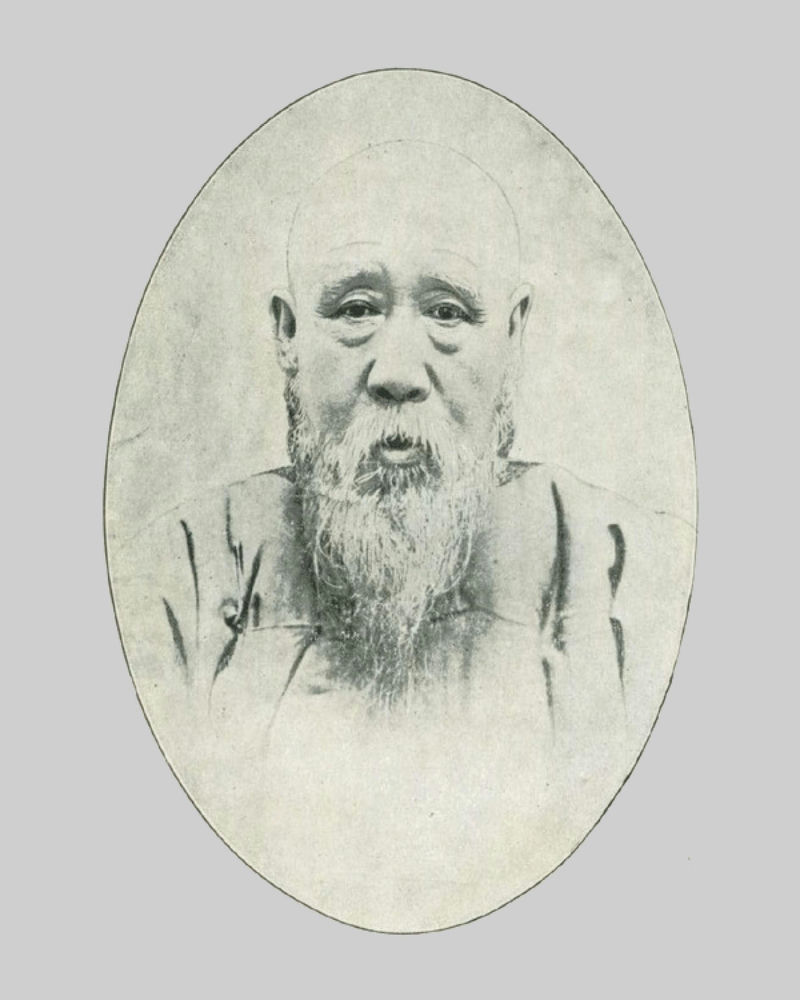

Portrait of Wu Chang-shou (吳昌碩)

Folding fan with seal script calligraphy by Wu Chang-shou (吳昌碩)

At the same time, amongst the various styles of calligraphy, I try as much as possible to collect works by representative calligraphers: for example, the large seal script and small seal script of Wu Jang-chih (吳讓之 1799-1870) and Wu Ta-ch’eng (吳大澂 1835-1902), the clerical script of Yu Yüeh (俞樾 1821-1907), the regular script of Chen Pao-ch’en (陳寶琛 1848-1935) and Lin Chang-min (林長民 1876-1925), the running script of Ho Shao-chi (何紹基 1799-1873) and Cheng Hsiao-hsü (鄭孝胥 1860-1938), the standard cursive script of Yü Yu-jen (于右任 1879-1964), the wild cursive script of P'u Ju (溥儒 1896-1963) in the style of Huai Su (懷素 737-799 AD) and so on. There are also works by Tung Tso-pin (董作賓 1895-1963) in oracle bone style, Wu Chang-shuo (吳昌碩 1844-1927) in stone drum style, Lo Chen-yü (羅振玉 1866-1940) in bronze inscription style, Shen Tseng-chih (沈曾植 1850-1922) in early cursive script, Yü Fei-an (于非闇 1889-1959) and Chuang Yen (莊嚴 1899-1980) in slender gold style, each showcasing his unique expertise. In addition, contemporary calligraphers from both sides of the Taiwan Strait, such as Shen Yin-mo (沈尹默 1883-1971), Pai Chiao (白蕉 1907-1969), Teng San-mu (鄧散木 1898-1963), Ch’i Kung (啟功 1912-2005), Wang Chuang-wei (王壯為 1909-1998), Li Yu (李猷 1915-1997) as well as Chiang Chao-shen (江兆申 1925-1996) who passed away last month, all have works in my fan collection.

Portrait of Yü Yu-jen (于右任)

Folding fan with running script calligraphy by Yü Yu-jen (于右任)

Landscape, Flora and Fauna, Human Figure Fans

The subjects of folding fans with calligraphy and paintings fall mostly within these three categories. Among them, landscape paintings are the most common. Fan collectors also generally prefer to classify their collections according to these three main categories. However, since I have adopted different classification groups, such as Ming dynasty Fans, Ch’ing dynasty Fans, Calligraphy Fans, etc., these categories significantly reduced the number of available fans for my Landscape, Flora and Fauna Fans categories. Fans featuring Chung K’uei (鍾馗 a Taoist deity) occupy almost the whole Human Figure Fans category. As a result, it becomes challenging to form a substantive collection in Landscape, Flora and Fauna, and Human Figure Fans categories with the remaining fans. Furthermore, for several major artists such as Chang Dai-chien (張大千), P'u Ju (溥儒), Huang Pin-hung (黃賓虹 1865-1955), Wu Hu-fan (吳湖帆 1894-1968), and Ch'i Pai-shih (齊白石 1864-1957), I have more than three folding fans by each of them in my collection. Their works encompass landscape, flora and fauna, human figure, and calligraphy. If the fans are classified by subjects, then works by the same artist would have to be separated into two or three categories, which would not be appropriate. Therefore, for those artists with multiple fan paintings, I have created separate “accounts” for each of them. In this way, according to my fan classification, the Landscape, Flora and Fauna Fans categories still manage to be retained, but the category of Human Figure Fans has to be discarded.

Portrait of P'u Ju (溥儒)

Folding fan with painting of landscape by P'u Ju (溥儒)

Portrait of Wu Hu-fan (吳湖帆)

Folding fan with painting of lotuses by Wu Hu-fan (吳湖帆)

Portrait of Chang Dai-chien (張大千)

Folding fan with human figure by Chang Dai-chien (張大千)

Chung K’uei (鍾馗 Taoist Deity) Fans

This is an important feature in my “thematic fan category”, but it is also a category that has brought me considerable frustration in the process. Currently, I have over thirty Chung K’uei (鍾馗) fans, and among them, are splendid works by renowned artists such as Jen Hsün (任薰 1835-1893) and Jen Po-nien (任伯年 1840-1895) from the Ch’ing dynasty, contemporary artists like Tang Yün (唐雲 1910-1993), Wu Ch’ing-hsia (吳青霞 1910-2009), Huang Chün-pi (黃君璧 1898-1991), and modern artists like Lin Yü-shan (林玉山 1907-2004) and Cheng Shan-hsi (鄭善禧). However, the Chung K’uei fans by those master painters famous for depicting Chung K’uei, such as Hsü Pei-hung (徐悲鴻 1895-1953), Chang Dai-chien (張大千 1899-1983), Wu Chang-shuo (吳昌碩 1844-1927), Ch’i Pai-shih (齊白石 1864-1957), and Fu Pao-shih (傅抱石 1904-1965) are missing from my collection. This has caused me a great sense of frustration. I have been collecting Chung K’uei fans for over a decade, and oddly enough, the Chung K’uei fans by the aforementioned masters have never come my way for collecting. It seems the saying collecting cultural artefacts depends on fate and serendipity holds some truth.

Portrait of Hsü P’ei-hung (徐悲鴻)

Folding fan with painting of Chung K’uei (鍾馗) by Hsü P’ei- hung (徐悲鴻)

Li-yüan (梨園 Opera Community) Fans

This is also one of the highlights of my “thematic fan category”, and it is a category that I am quite satisfied with in terms of my collection.

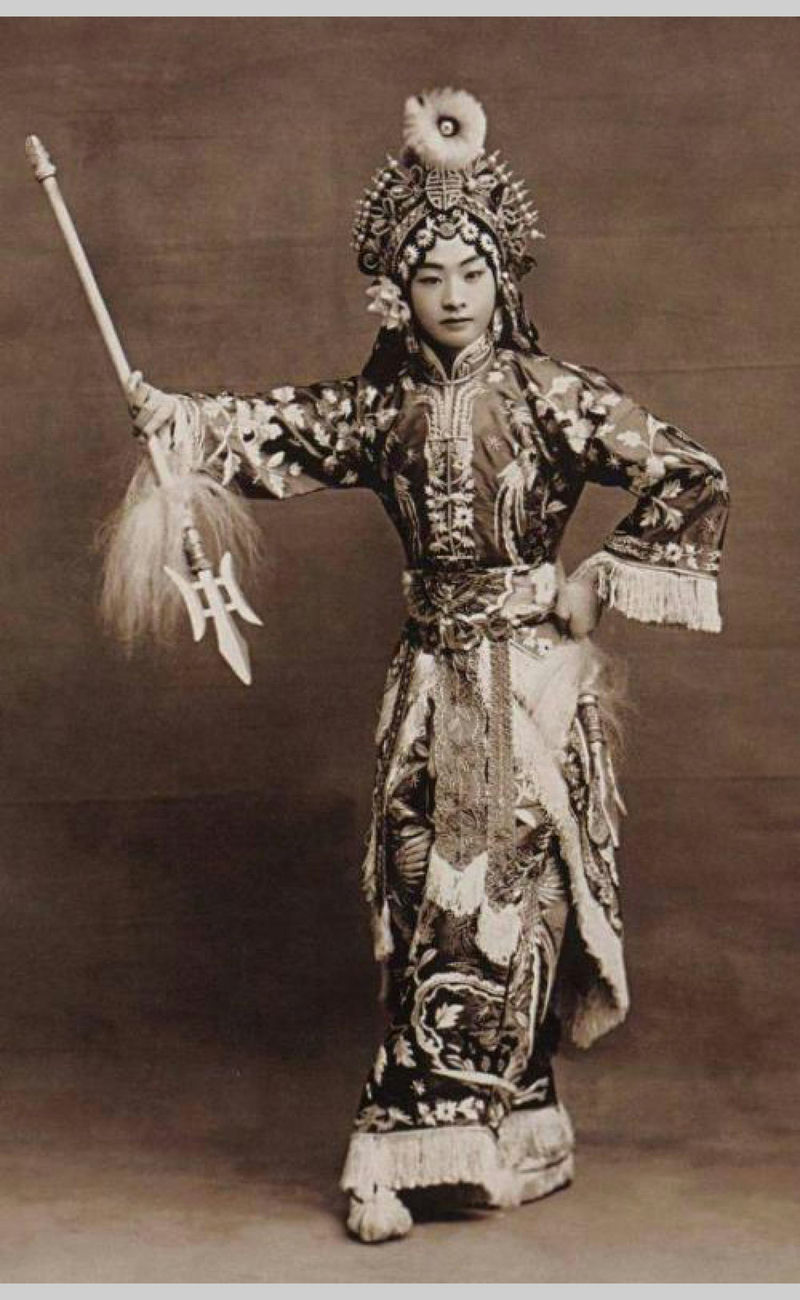

The term Li-yüan refers to the community of Peking Opera (京劇) or P’ing-chüo (平劇). Therefore, Li-yüan Fans are also known as Famous Singers Fans.

Young Peking Opera singers in their early days may not have had much education, but after becoming famous, many of them studied intensively under the guidances of well-known literati in reading, calligraphy, and painting. The prevailing social trend was that a “famous singer” without literary skills could not remain popular for long. Therefore, during the period of the Pei-yang Government (from the early years of the Republic of China until unification after the Northern Expedition in the 16th or 17th year of the Republic), Li-yüan Fans were very popular.

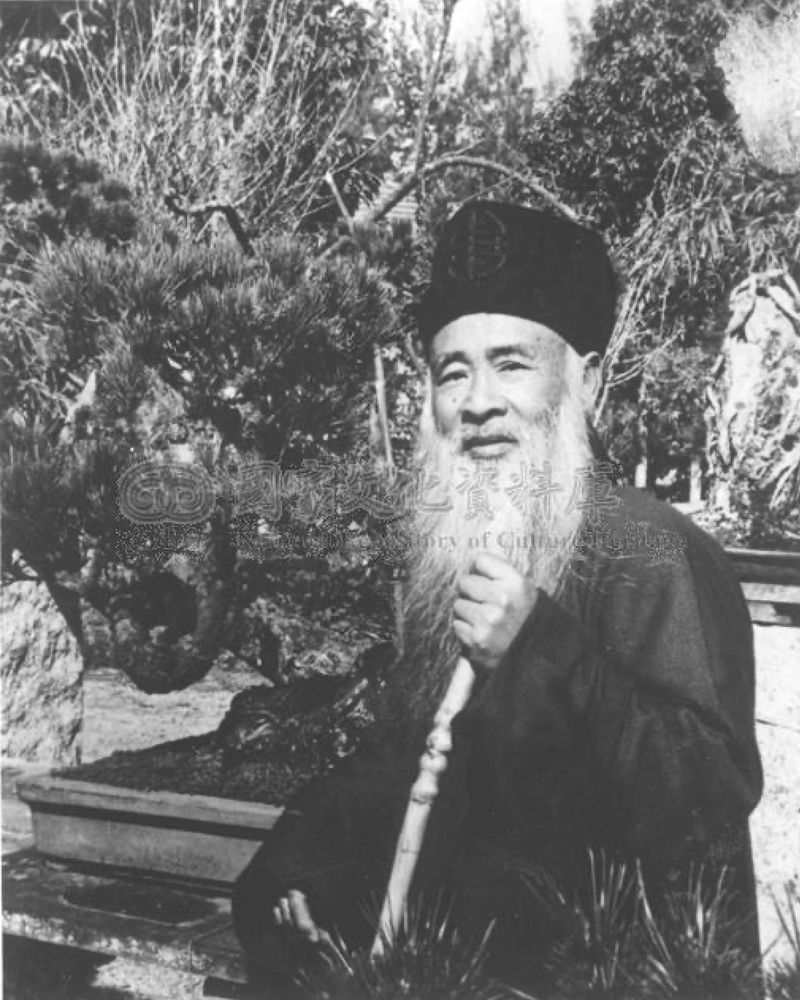

Portrait of Wang Yao-ch’ing (王瑤卿)

Folding fan with painting of prunus by Wang Yao-ch’ing (王瑤卿)

I started collecting Li-yüan fans very early. Nearly thirty years ago, during the peak of the Cultural Revolution in mainland China, vast quantities of Chinese cultural artefacts obtained from the raiding of homes and confiscation of items by the Red Guards of the Chinese Communist Party were sold in Japan. At that time, I was working in Tokyo and came across old fans with inscriptions and paintings by Mei Lan-fang (梅蘭芳 1894-1961), Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu (程硯秋 1904-1958) and others in the Japanese antique markets. I was greatly intrigued and started to collect them. Over time, I acquired quite a few fans, peaking at around fifty or sixty fans. However, after repeated selection and elimination to keep only the best of the best, I now have over twenty such fans.

Portrait of Ma Lien-liang (馬連良 1901-1966)

Folding fan with painting of prunus by Ma Lien-liang (馬連良)

In this category, I am most proud of a set of calligraphy and painting fans featuring the Four Great Male Travesti Singers (Dan singers 四大名旦), Mei Lan-fang (梅蘭芳), Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu (程硯秋), Shang Hsiao-yün (尚小雲 1900-1976) and Hsün Hui-sheng (荀慧生 1900-1968). Actually, calligraphy and paintings by the Four Great Male Travesti Singers (Dan singers 四大名旦) are not particularly rare, and at one point I had their collaborative works of calligraphy and paintings on a single fan, but I later exchanged it with someone.

The final set of folding fans by the Four Great Male Travesti Singers (Dan singers) that I kept consists of individual fans by each one of them, featuring either their calligraphy or painting. However, the reverse side of the fans were also by renowned performers equally famous as the Four Great Male Travesti Singers. Furthermore, the performers on the reverse side must not be duplicates and must be four different individuals. Therefore, the correct title for this series of four folding fans is the Fan Ensemble of Four Great Male Travesti Singers and Eight Great Role Singers.

The lineup of the four folding fans is as follows:

Chrysanthemum by Mei Lan-fang (梅蘭芳), and calligraphy by Shih Hui-pao (時慧寶 1881-1943).

Calligraphy by Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu (程硯秋), and loquat by Yü Chen-fei (俞振飛 1902-1993).

Flora and fauna by Shang Hsiao-yün (尚小雲), and calligraphy by Yü Shu-yen (余叔岩 1890-1943).

Landscape by Hsün Hui-sheng (荀慧生), and calligraphy by Yen Chü-p’eng (言菊朋 1890-1942).

Portrait of Mei Lan-fang (梅蘭芳)

Folding fan with painting of chrysanthemum by Mei Lan-fang (梅蘭芳)

Portrait of Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu (程硯秋)

Folding fan with regular script calligraphy by Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu (程硯秋)

Portrait of Shang Hsiao-yün (尚小雲)

Folding fan with painting of flora and fauna by Shang Hsiao-yün (尚小雲)

It took me nearly a decade of effort to complete this set of four folding fans. The folding fan featuring the work of Hsün Hui-sheng (荀慧生) is the last one I acquired, and it happened to be in the possession of a fellow collector of Li-yüan calligraphy and paintings. He was adamant that he would not part with it. In the end, I had to “sacrifice” my cherished Four Male Travesti Singers on One Fan in exchange before I succeeded in acquiring it.

Portrait of Hsün Hui-sheng (荀慧生)

Folding fan with painting of landscape by Hsün Hui-sheng (荀慧生)

In fact, with respect to the twenty or so Li-yüan fans that I currently own, each folding fan features calligraphy and painting on the two sides by famous performers who were closely associated with each other. For example, the folding fan by the brothers Wang Yao-ch’ing (王瑤卿 1881-1954) and Wang Feng-ch’ing (王鳳卿 1883-1956); the folding fan by Chiang Miao-hsian (姜妙香 1890-1972) and T’an Fu-ying (譚富英 1906-1977) who were father-in-law and son-in-law. The rarest fan is a collaboration between the two beautiful singers Yen Hui-chu (言慧珠 1919-1966) and Wu Su-ch’iu (吳素秋 1922-2016). Over forty years ago, the two singers simultaneously gained great popularity throughout the entire north and south with their exceptional beauty and talents. Later during the Cultural Revolution, Yen Hui-chu (言慧珠) was forced to commit suicide while Wu Su-ch’iu (吳素秋) barely survived the catastrophe. Two years ago, she remarried in Peking. There are works from nearly fifty famous singers on the twenty or so Li-yüan folding fans that I have. Most have passed away. It seems that Wu Su-ch’iu (吳素秋) is the only one remaining.

Portrait of Yen Hui-chu (言慧珠)

Art and Culture Fans

The name of this particular theme is not very fitting, but it is a category that I am fond of. The creators of the works featured in this category are not professional calligraphers nor painters; the technical skill in these works may not be at the level of professionals. However, the works have an elegant and refined quality that exudes a literary aura, which maybe lacking sometimes in the work of professional artists. Among the notable pieces in this collection are a calligraphy fan by Chou Tso-jen (周作人 1885-1967), a calligraphy and painting fan by Lu Hsiao-man (陸小曼 1903-1965, wife of Hsü Chih-mo 徐志摩 1897-1931), a calligraphy fan by Wu Mei (吳梅 1884-1939, a master of lyrics), a calligraphy and painting fan by T’ai Ching-nung (臺靜農 1902-1990), and a calligraphy fan by Ch’en Tieh-i (陳蝶衣 1907-2007, a song composer for films). A few years ago, someone living in Canada brought me a calligraphy fan by Mr. Hu Shih (胡適 1891-1962) to sell. I was delighted to see it and was very keen to buy it. However, the price was very high, he claimed that he was previously unwilling to sell even with an offer of USD 20,000. I recognized the difficulty and withdrew my interest.

Portrait of T’ai Ching-nung (臺靜農)

Folding fan with painting of prunus by T’ai Ching-nung (臺靜農)

Original Seal Impression Fans

This is a new theme that I added only three years ago. To my surprise, after searching on multiple fronts, I have obtained the fruitful result of thirteen or fourteen fans.

About three years ago, I came across two folding fans in an antique shop in Taipei. Both fans had seal impressions on the fan face, and one seal caught my attention. This seal was believed to be an ancient seal attributed to Chao Fei-yen (趙飛燕), a famous beauty who became empress in the Han dynasty. This seal had a distinguished pedigree, having been previously owned by the prominent Ming dynasty collector Hsiang Mo-lin (項墨林 1525-1590) and the Ch’ing dynasty calligrapher Ho Shao-chi (何紹基 1799-1873). Later, it came into the possession of Chen Chieh-ch’i (陳介祺 1813-1884), a great collector in late Ch’ing. Generations of collectors had treasured and guarded this seal closely and it was not easily shown to others. It is said that during the time when it was owned by Chen Chieh-ch’i (陳介祺), borrowing this seal to make an impression required a payment of ten taels of silver, indicating its exceptional value. (The words engraved on the seal was long assumed to be Chieh-shu Ch’ieh Chao 緁紓妾趙, hence associated with Chao Fei-yen 趙飛燕, Chieh-shu being the original name of Chao Fei-yen. But in the early years of the Republic, after studying it carefully, the renowned seal engraver Fang Chieh-k’an 方介堪 discovered the previous misinterpretation and correctly identified the words as Chieh-shu Ch’ieh-shao 婕紓妾娋 which had no connection to Chao Fei-yen 趙飛燕.) That day, as I examined the seal impressions on the fan in detail, it was evident that they were original impressions (directly impressed and not replicated copies as commonly seen in seal catalogs). Then I looked again at the seal impression at the corner of the fan face, and it turned out to be the words Wan-yin-lou Chu (萬印樓主), which was the studio name of Chen Chieh-ch’i (陳介祺), the last owner of this ancient seal! In that case all the seal impressions on the fan must be made by seals that belonged to the precious collection of Chen Chieh-ch’i.

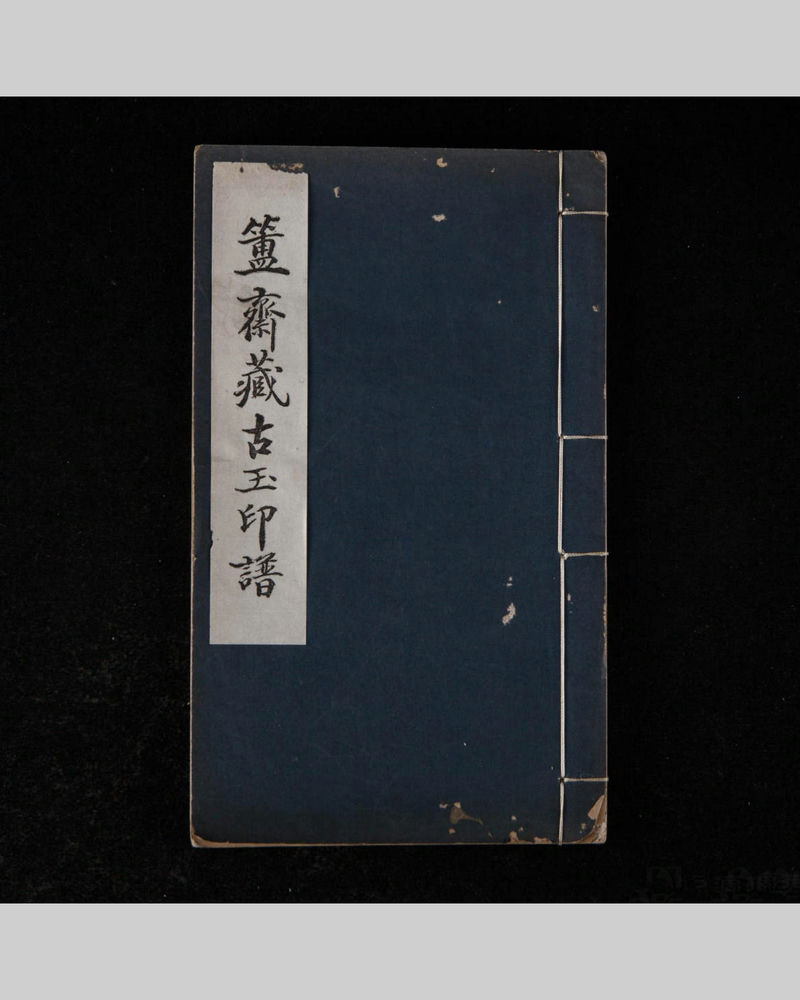

Front cover of Album of Ancient Jade Seal Impressions in the Fu Chai Collection compiled by Chen Chieh-ch’i (陳介祺) in the Ch’ing dynasty

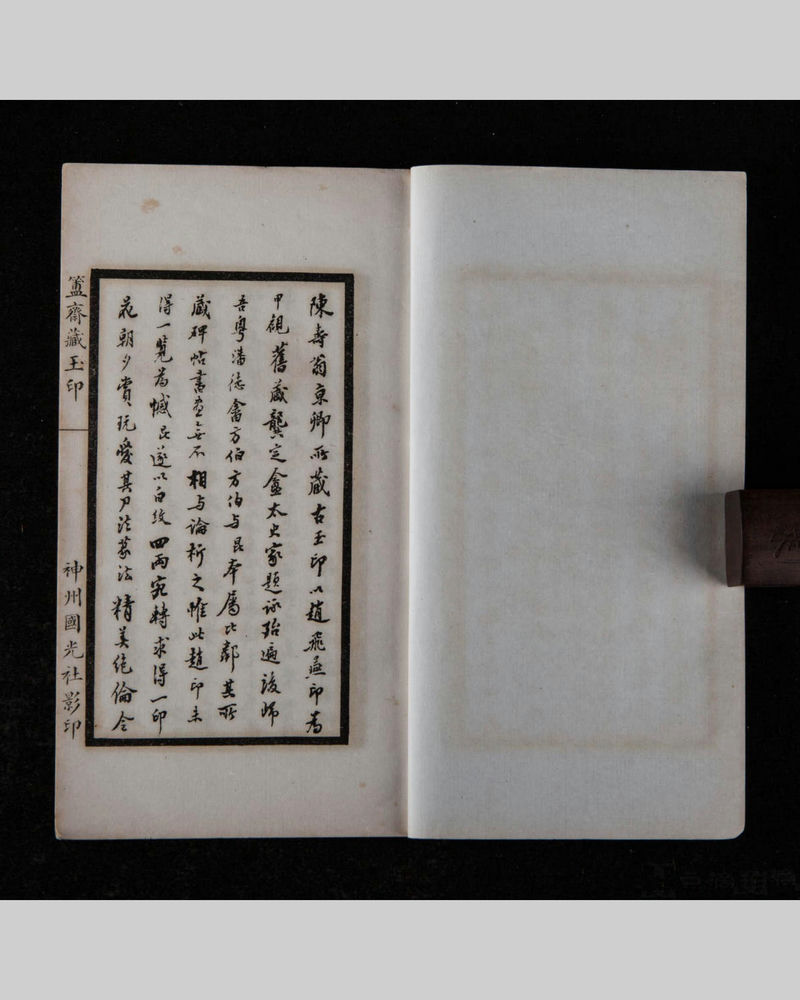

Introduction of Album of Ancient Jade Seal Impressions in the Fu Chai Collection compiled by Chen Chieh-ch’i (陳介祺) in the Ch’ing dynasty

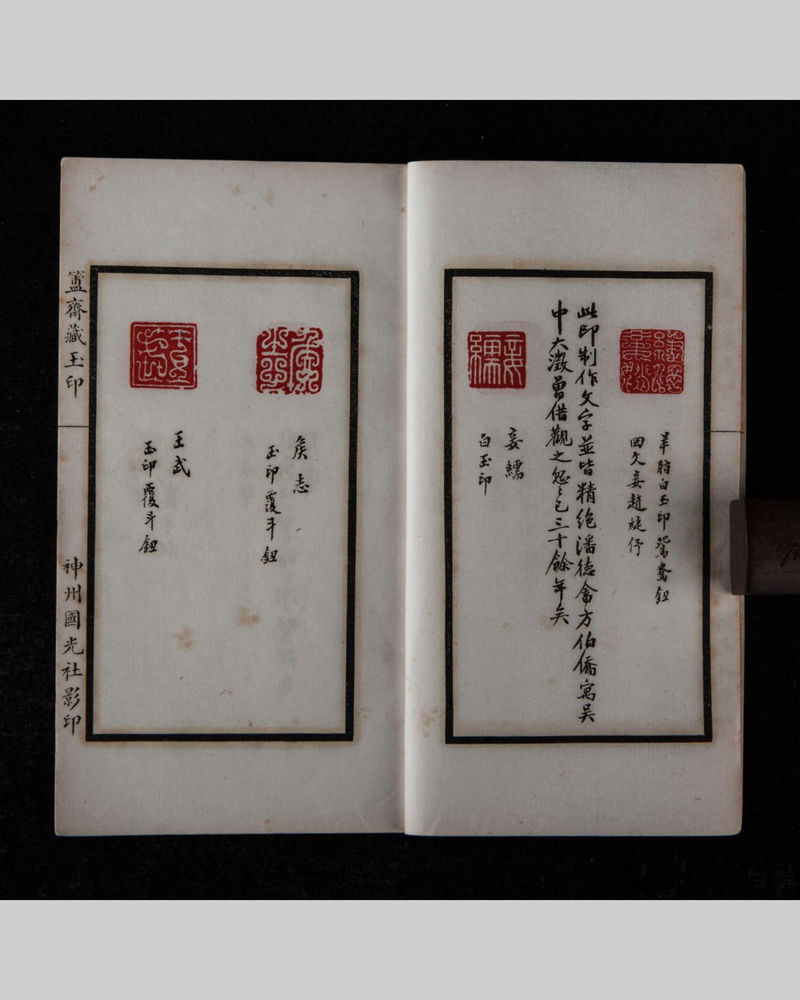

Inside page of Album of Ancient Jade Seal Impressions in the Fu Chai Collection compiled by Chen Chieh-ch’i (陳介祺) in the Ch’ing dynasty

Folding fan impressed with ancient seals in the Fu Chai Collection owned by Chen Chieh-ch’i (陳介祺) in the Ch’ing dynasty

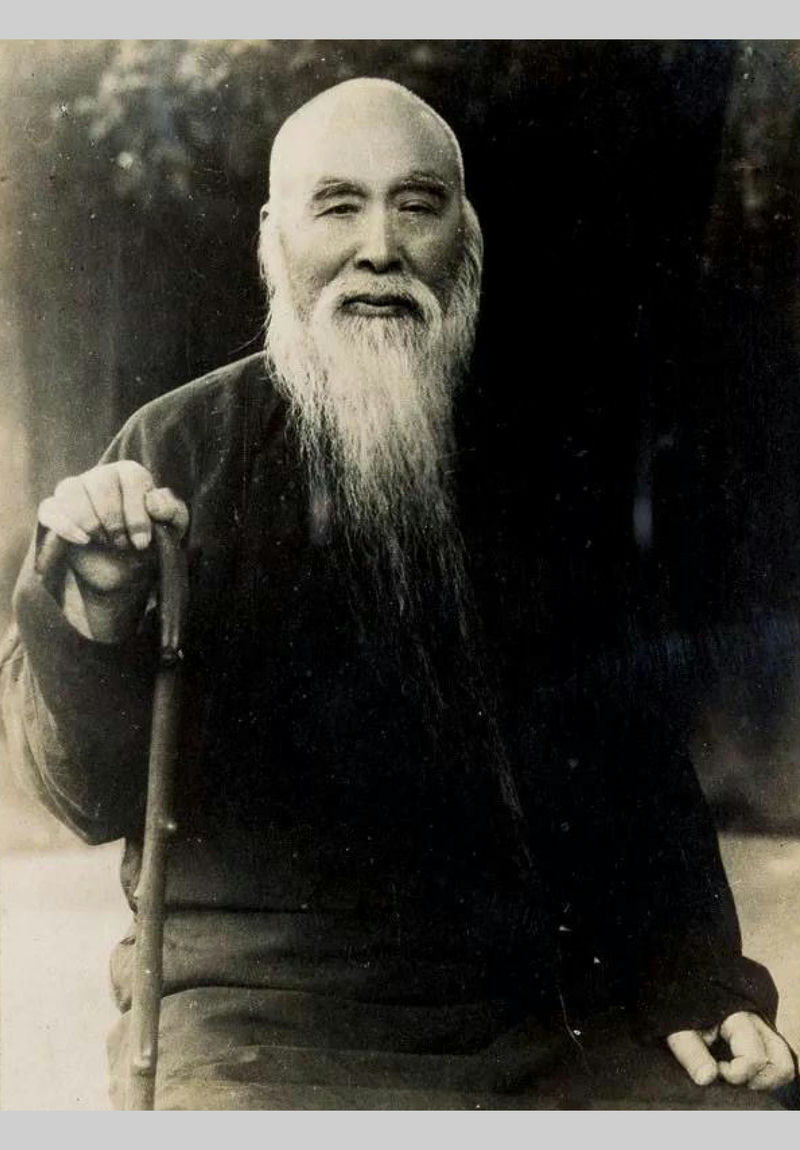

I then carefully examined the other fan and realized that it was no ordinary item either. The seal impressions on the fan face were made from seals carved by the Eight Masters of Hsi-ling (西泠八家), with a seal from each master. Ink rubbings of their side inscriptions were made and then pasted onto the fan face. As I scrutinized the name of the person who made the impressions, I found that it was Ko Chang-ying (葛昌楹 1892-1963), famous for his seal collection in P'ing-hu, Chekiang Province. I was ecstatic and bought both fans immediately.

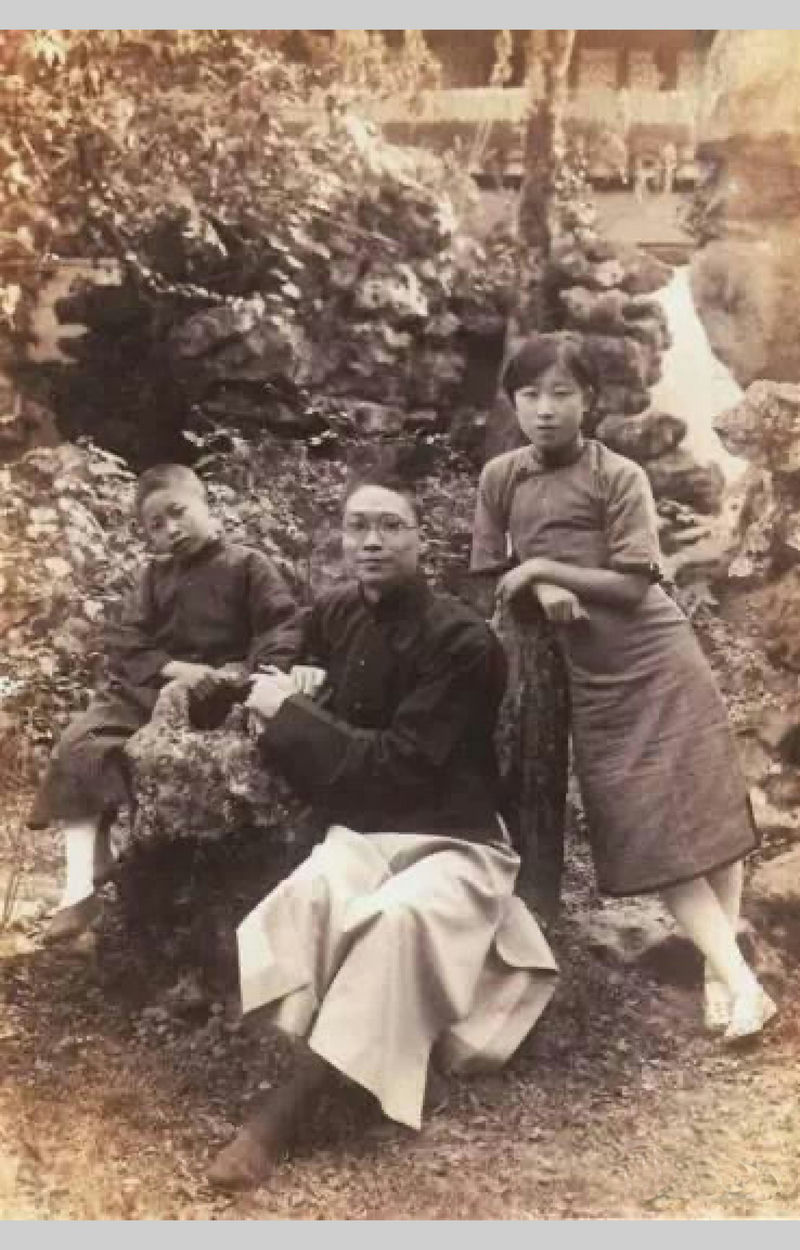

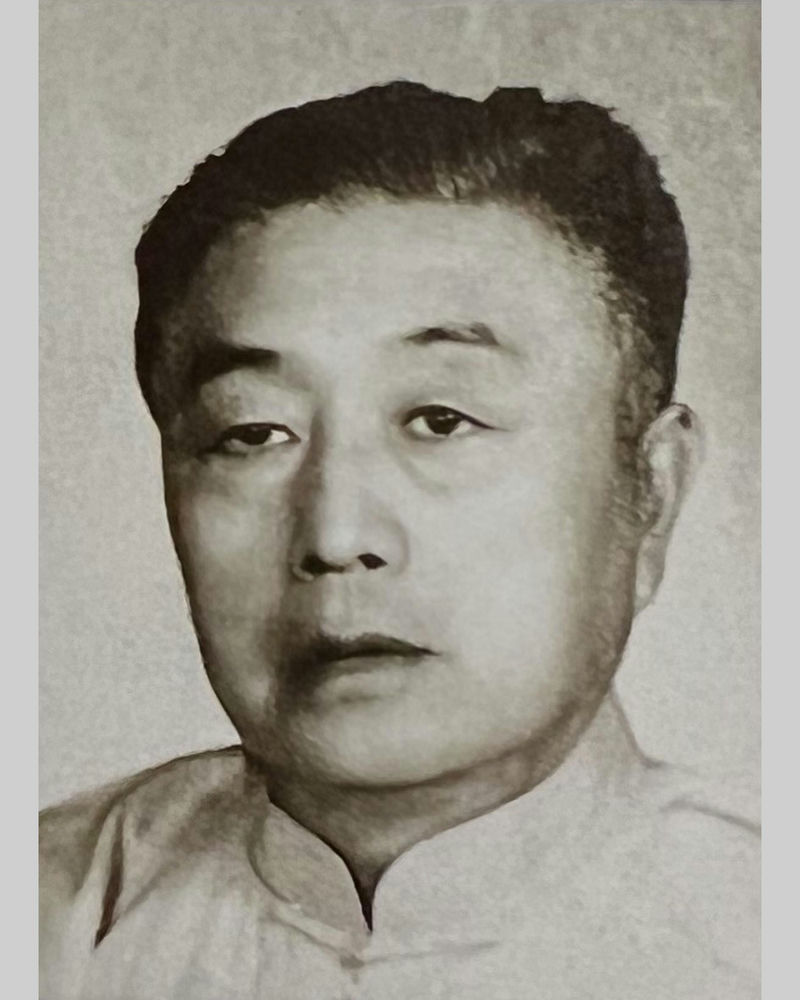

Portrait of Ko Chang-ying (葛昌楹)

Folding fan impressed with seals by Ch’ing dynasty masters in the collection of Ko Chang-ying (葛昌楹)

Shortly after acquiring these two fans with original seal impressions, I had the opportunity to acquire another fan impressed with seals in the collection of Ch’en Han-ti (陳漢第 1874-1949), a Hanlin Academician in late-Ch’ing known for his collection of Han dynasty seals. Using these three fans as the foundation, I established Original Seal Impression Fans as a new category.

Folding fan impressed with ancient jade seals in the collection of Ch’en Han-ti (陳漢弟)

Unbelievably, within a little over two years after I decided to set up this category, I had the good fortune to gradually acquire nearly ten folding fans with seal impressions. Among them were original seal impressions of seals by Chao Tz’u-hsien (趙次閑 1781-1860), Wu Jan-chih (吳讓之 1799-1870), Teng San-mu (鄧散木 1898-1963), Pai Chiao (白蕉 1907-1969) and others. Particularly rare was the discovery last year that a collector possessed a set of ten seals engraved by Chang Dai-chien (張大千) in his early years. After my sincere entreaty to borrow the seals, he generously consented, and I requested the seal engraver Chen Hung-mien (陳宏勉) to make impressions of the seals and ink rubbings of the side inscriptions. A fan was then created, enriching my collection of fans with original seal impressions.

Exquisite Fan Guards

The purpose of this theme is to showcase the beauty of the fan guards. As mentioned earlier, the artistries of folding fans can be appreciated from three perspectives: the beauty of painting on the fan face, the beauty of calligraphy on the fan face, and the beauty of the fan guards. The previous themes in this article focus on the calligraphy and paintings of the fan face, while the fan guards play a secondary role. In other words, although the folding fans in each of the previously mentioned categories had beautiful fan guards, when compared with calligraphy and paintings, the beauty of calligraphy and paintings took precedence, and the fan guards served only to complement. However, the fans in this category are different to the folding fans in the previous themes. In this category, the primary focus is on the beauty of the fan guards, while calligraphy and paintings on the fan faces play a secondary role.

Portrait of Chen Tan-ju (陳澹如). Photograph courtesy Mr. Kuo Hai

Bamboo fan guards carved by Chen Tan-ju (陳澹如). Photograph courtesy Mr. Kuo Hai

The most representative piece in this theme is a folding fan with fan guards engraved by the renowned Shanghai bamboo carver Li Tsu-han (李祖韓 1891-1964).

Li Tsu-han engraved in miniature the entire text of the Hu-ting (曶) archaic bronze tripod from the reign of Emperor Kung (共王) of the Western Chou dynasty on two bamboo fan guards employing the relief technique. The difficulty of this work lies in three aspects: first, the use of the relief technique, which is many times more challenging than the intaglio technique; second, the engraving consists of approximately 500 words, each of which is only the size of a rice grain; third, the “miniaturized engraving” faithfully reproduced the original script of the archaic bronze tripod, and not the carver’s own calligraphic style.

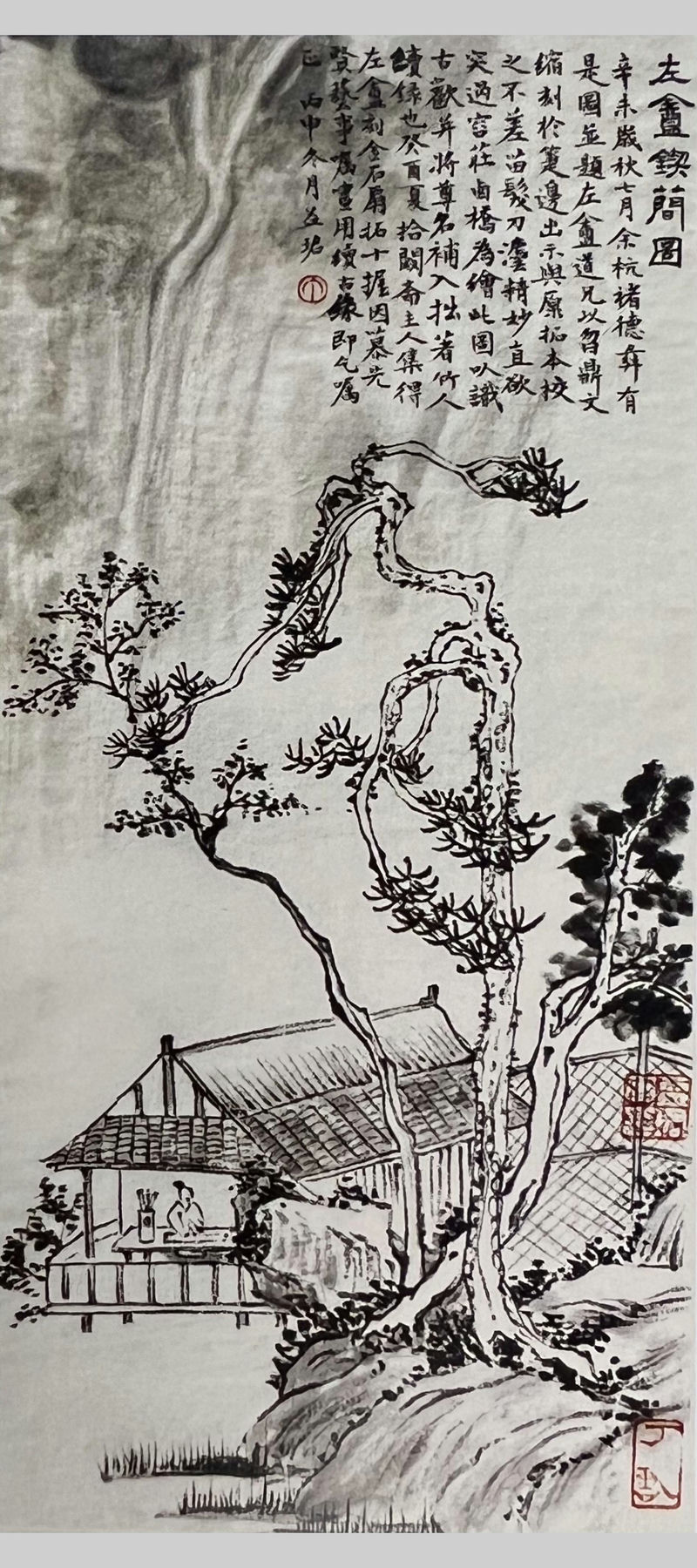

The fan guards were engraved in the 20th year of the Republic (1931), and when it was completed, it caused a great sensation in the Shanghai art scene. After the fan face was mounted onto the fan sticks by the Shanghai fan workshop Ku-hsiang Shih (古香室), the famous epigraphy scholar and calligrapher Lo Chen-yu (羅振玉 1866-1940) copied a section of the Hu-ting text on the fan face with an inscription: “Tso-an (左庵 was the hao of Li Tsu-Han 李祖韓) is a contemporary giant in the art of bamboo carving. Recently, I had the opportunity to see the ink rubbing of his carving of the complete text of the Hu-ting archaic bronze tripod on fan guards. The carving is as delicate as hair strands, faithfully matching the original script. It is truly divine craftsmanship. In the summer of hsin-wei year, I copied a section of the text on the Hu-ting archaic bronze tripod to record my admiration.”

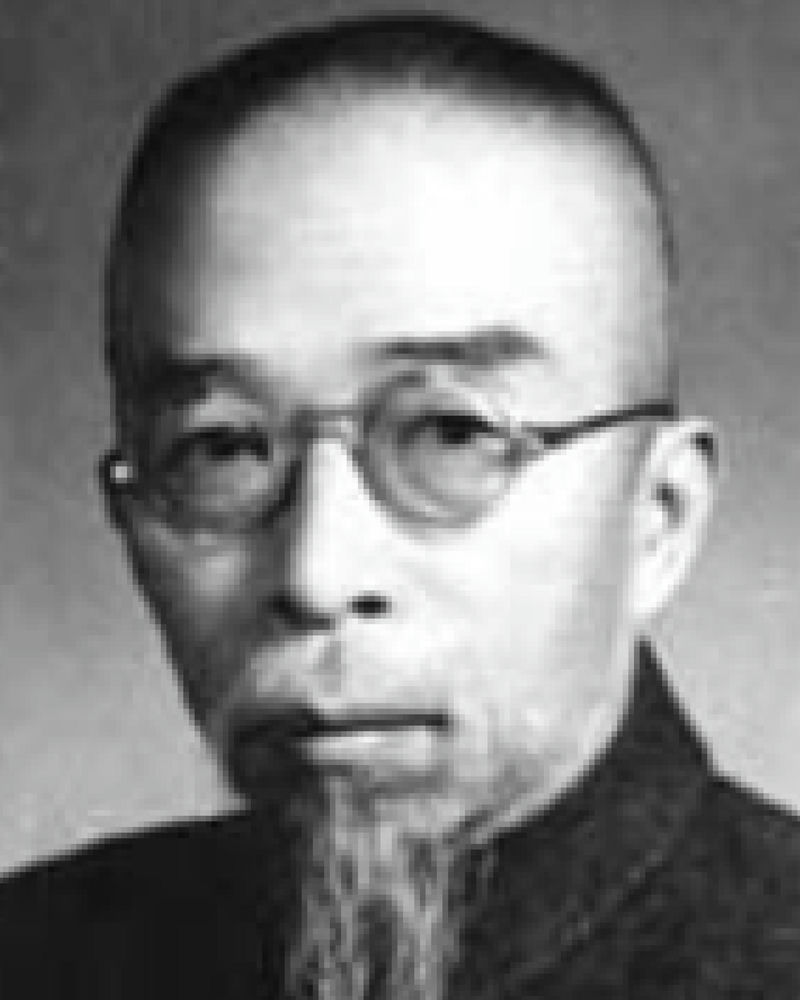

Portrait of Li Tz’u-han (李祖韓). Photograph courtesy Mr. Kuo Hai

Ting I-chün (丁益珺) copied the painting titled Picture of Tso-an Engraving Bamboo by Ch’u Teh-i (禇德彝). Photograph courtesy Mr. Kuo Hai

On the other side of the fan is a painting titled Picture of Tso-an Engraving Bamboo (左盦鍥簡圖) by Chu Teh-i (褚德彞 1871-1942), who was also a seal carver, calligrapher, and an expert in bamboo carving. He inscribed the painting with the following words:

“Brother Tso-an engraved in miniature the text of the Hu-ting archaic bronze tripod on bamboo fan guards. When compared to the original ink rubbing, it is as accurate as can be, with exquisite knife work... I painted this picture to express the pleasure of antiquity, and wish to incorporate your honourable name into my humble work Chu-jen-hsü-lu (竹人續錄, by Chu Teh-i 褚德彞, A Supplementary Record of Bamboo Engravers)

Although this fan incorporates calligraphy and painting, they were both created to celebrate the exquisite craftsmanship of the fan guards. This folding fan is a rare example whereby the focus of appreciation is the fan guards, and it is a representative piece in my collection for this category. There are also other notable pieces, such as the exceedingly fine fan guards carved by the master ivory carver Shen Hsiao-chuang (沈筱莊) and the intricately engraved mottled bamboo fan guards by the master bamboo carver Chin Hsi-ya (金西厓 1890-1979). Although they are all folding fans with calligraphy and paintings, in these cases, the fan guards are more important than the artworks on the fan faces.

Portrait of Pu Ch’in (溥伒)

Folding fan with calligraphy and paintings by P'u Ju (溥儒) and P'u Ch’in (溥伒 1893-1966) on the same fan face

There are also other fans such as those by multiple creators, large and small size fans, and others. However, they have not been classified under any special theme since there are just a few of them.

The classification by “special theme” as mentioned above is unsophisticated and far from ideal. I am using it for the time being in order to organize and preserve my collection. I will gradually improve upon this, and perhaps one day I can come up with a better management system. It is not impossible to completely overturn the current approach.

The purpose of this article is to introduce some of my ideas on the art of folding fans and to share my personal experience and insight in collecting folding fans. I advocate “thematic fan collections” with the intention of preserving and passing down the complete scope of fan culture. In today's world where electric fans and air conditioning units are ubiquitous, folding fans have gradually become “rare animals”. If no deliberate effort is made to preserve them, within eight to ten years, they will disappear from the world like the ancient dinosaurs.

Mr. Huang T’ien-ts’ai (黃天才) and Mr. Chang Dai-chien (張大千) in Taipei