Chinese literati engrave names, noms de plume, studio names, proverbs, pictograms and pictures onto seals. They are then impressed on calligraphy, paintings, books, manuscripts and letters. Apart from expressing refined sensibilities, seals can actually differentiate the authorships of works in ink and the identities of collectors. In late Ch’ing, those who were enthralled by writings and seal engravings even engraved short articles onto seals, subsequently there were seals with a hundred characters and inscriptions with a few hundred characters.

In the Collection of Lai-yen T’ang, there is an ivory seal with one hundred and forty four characters by Chang Chi-ju (張楫如). It encapsulates the finest features of microscopic engraving, each calligraphic stroke is in accordance with the rules of calligraphy, untainted by any vulgar tone. The carver would not be able to use eyesight for engraving. Nor will the beholder be able to use eyesight for inspection. It was carved through mind and heart. It has to be examined through mind and heart too. For the characters on the surface and side of the seal, they dissolve into nothingness. All that is left is but a shadow in the mind and the heart. For seal engraving to reach such realm, it is like walking into a fantastical terrain. Unfortunately microscopic engraving was too arduous and depleting for Chang Chi-ju, he was unable to attain long life.

In this article, the renowned seal engraver Ku Yao-hua describes in detail the ivory seal engraved by Chang Chi-ju. This piece is a rare treasure in the world of seals. For a hundred years it has languished in oblivion, and now finally it is to be admired by all.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

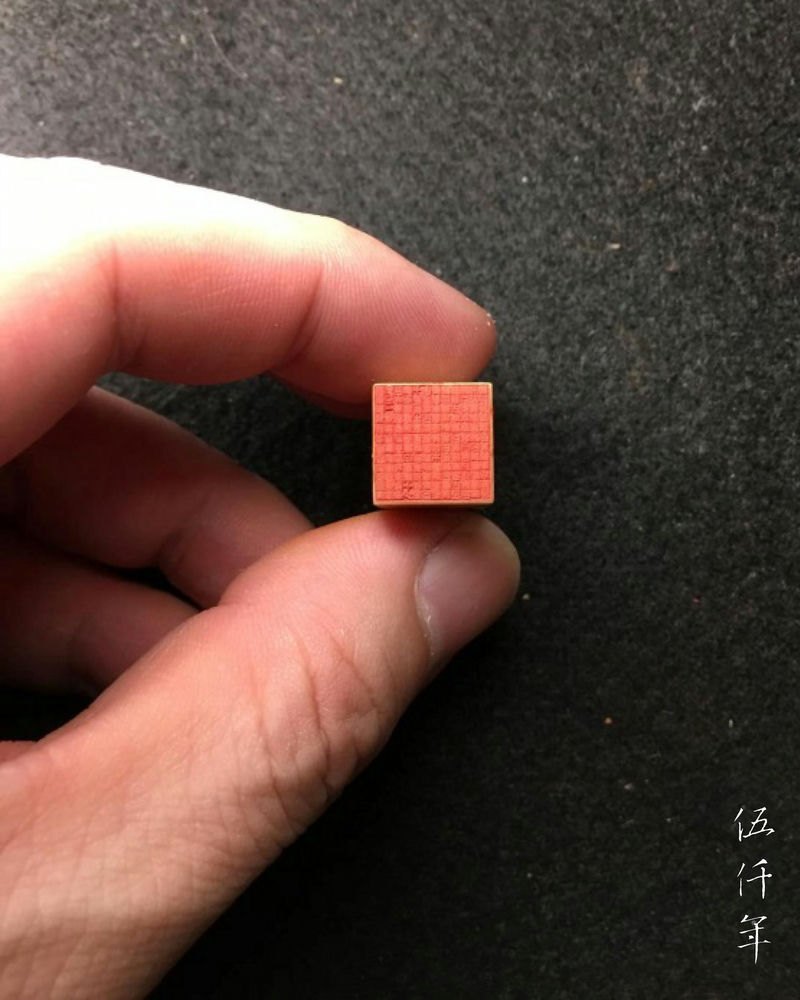

The author of this article holding the ivory seal by Chang Chi-ju. From the Collection of Lai-yen T’ang

Recently a seasoned seal collector friend showed me an old ivory seal. The engraved seal surface was filled with dirt and red ink paste. It was not possible to make a clear impression. He asked me to clean the engraved seal surface in order to read the words.

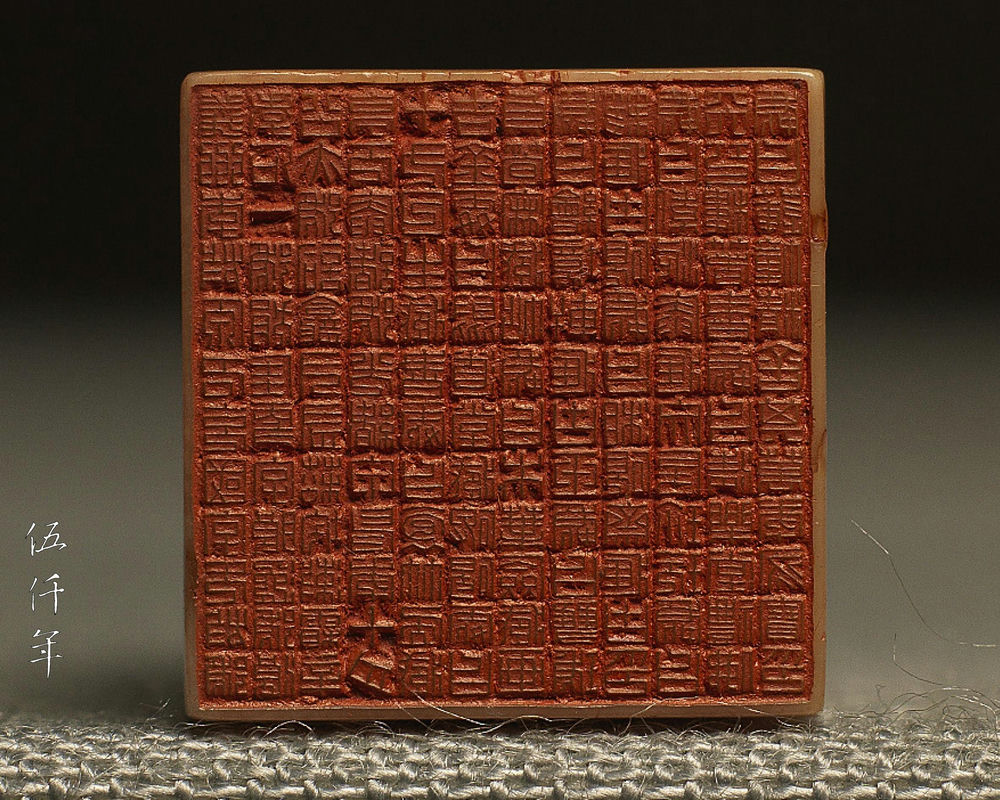

The carved surface of the ivory seal by Chang Chi-ju is 1.2 cm square. From the Collection of Lai-yen T’ang

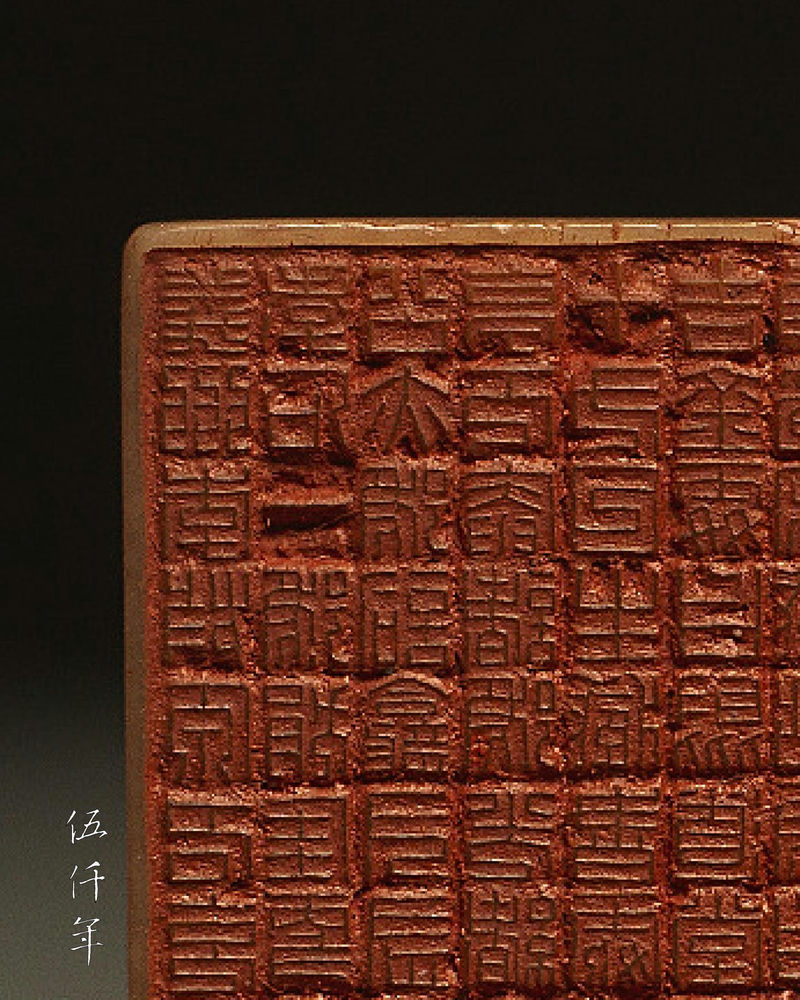

Even after cleaning the engraved seal surface, it was still not possible to make a clear impression by using the normal red ink paste. So I resorted to make my own special red ink paste. Only then was I able to study the seal properly. I was truly astounded by its finesse. The seal was engraved on a 1.2 cm square surface. A total of one hundred and forty four characters were engraved on it. Every stroke and every character are impeccable and precise. It is the most extraordinary engraving I have ever seen! After subtracting the spaces between the characters, as well as the spaces between the characters and the borders, the dimension of each character is ascertained to be just 0.09 cm square, notwithstanding the many characters that are comprised of multitudinous and complicated strokes.

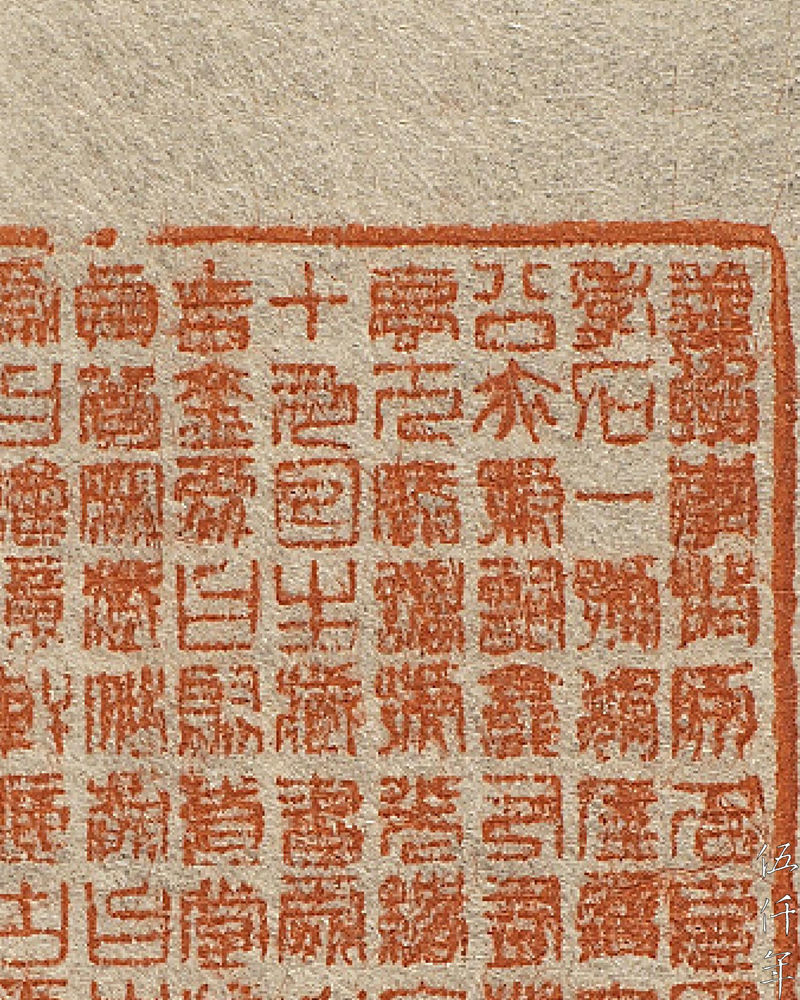

Enlargement of the carved surface of the ivory seal by Chang Chi-ju. From the Collection of Lai-yen T’ang

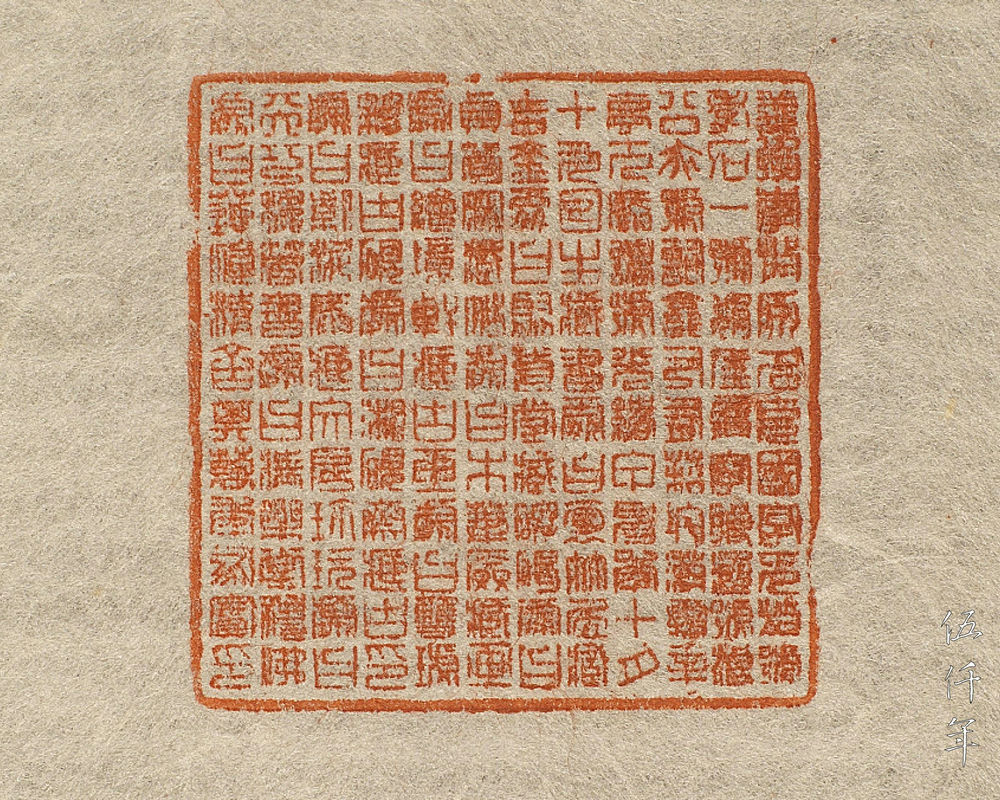

Enlarged seal impression of the ivory seal by Chang Chi-ju.

Enlarged detail of the carved surface of the ivory seal by Chang Chi-ju. From the Collection of Lai-yen T’ang

Enlarged detail of the ivory seal impression by Chang Chi-ju.

The words of the seal are:

“Li Fang (李放) from I-chou, original name K’ei-kuo (克國), tzu Chi-fang (旡放), hao Hsiao-shih (孝石), another hao Chüan-ya (狷厓). The tzu has been revised to Lang-i (朗逸), hao to Lang-kung (浪公), another hao to Tz’u-k’an (詞龕). Now there are other hao such as Sung-ch’a (菘垞), Shu-shuang (潄霜), Hsin-t’ing (辛亭) and Wu-an (兀庵). Born on 19 October of chia-shen (甲申) year in the Kuang-hsü reign. The place where books are stored is named Pao-chu Chü (抱竹居), the place where archaic bronzes are stored is named Chü-tao T’ang (聚道堂), the place where stone steles are stored is named Chih-hsüan Lin (直萱冧), the place where ink rubbings are stored is named Mu-yeh Ch’ien (木葉厱), the place where paintings are stored is named Hua-ching Hsüan (畫境軒), the place where ancient jades are stored is named Shuang-hu I (雙琥簃), the place where old inkstones are stored is named Hsiang-yen Chai (湘硯齋), the place where old seals are stored is named Tz’u-ni An (紫泥庵), the place where desk accoutrements and objets de virtu are stored is named T’ien-kung Lou (天功樓), the place where books are written is named Ch’ing-le T’ang (清樂堂), and the place where Buddha is worshipped is named Lien-ch’uang Ching-she (蓮幢精舍). This seal is to attest eternal cherishment.”

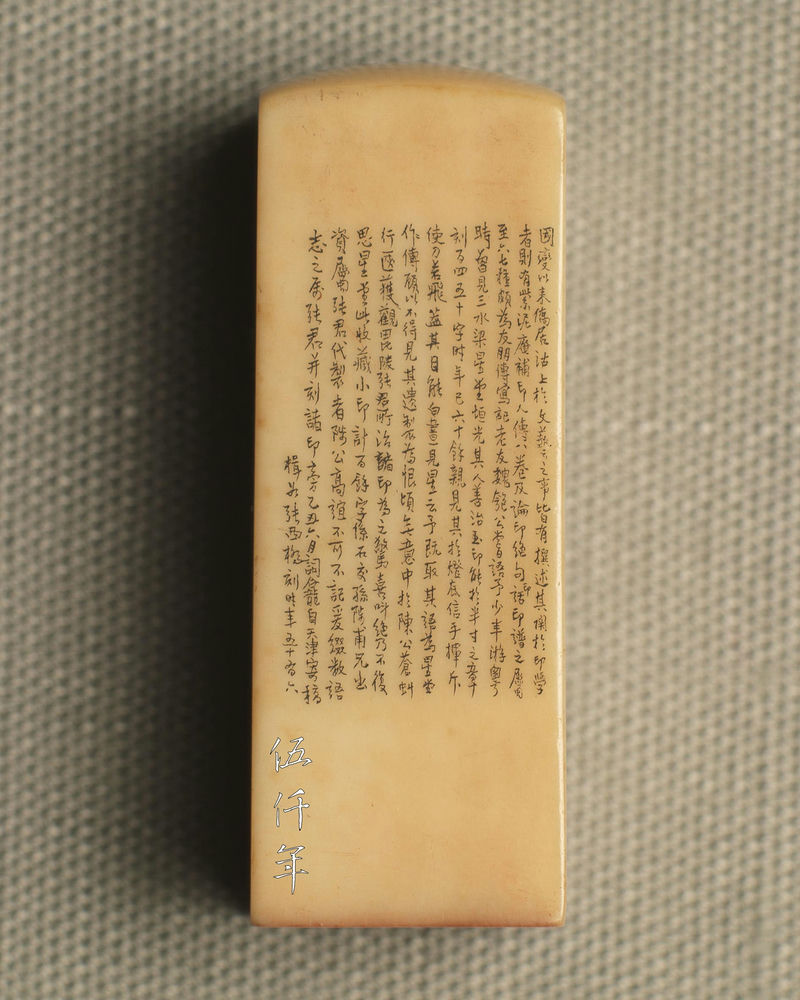

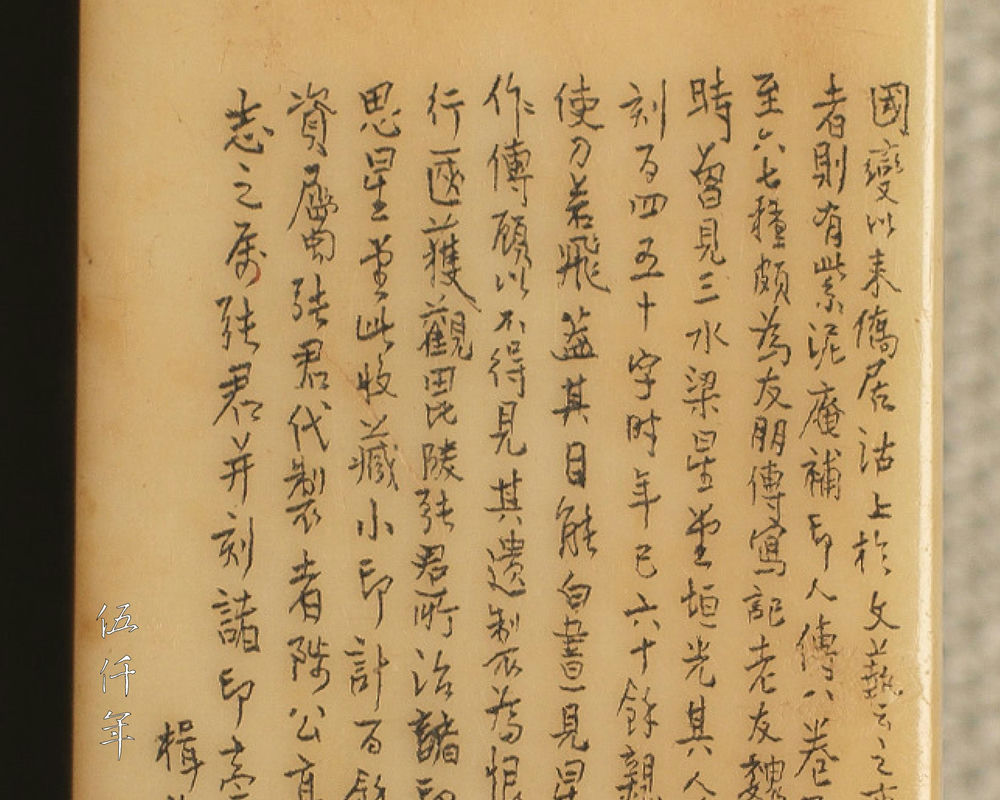

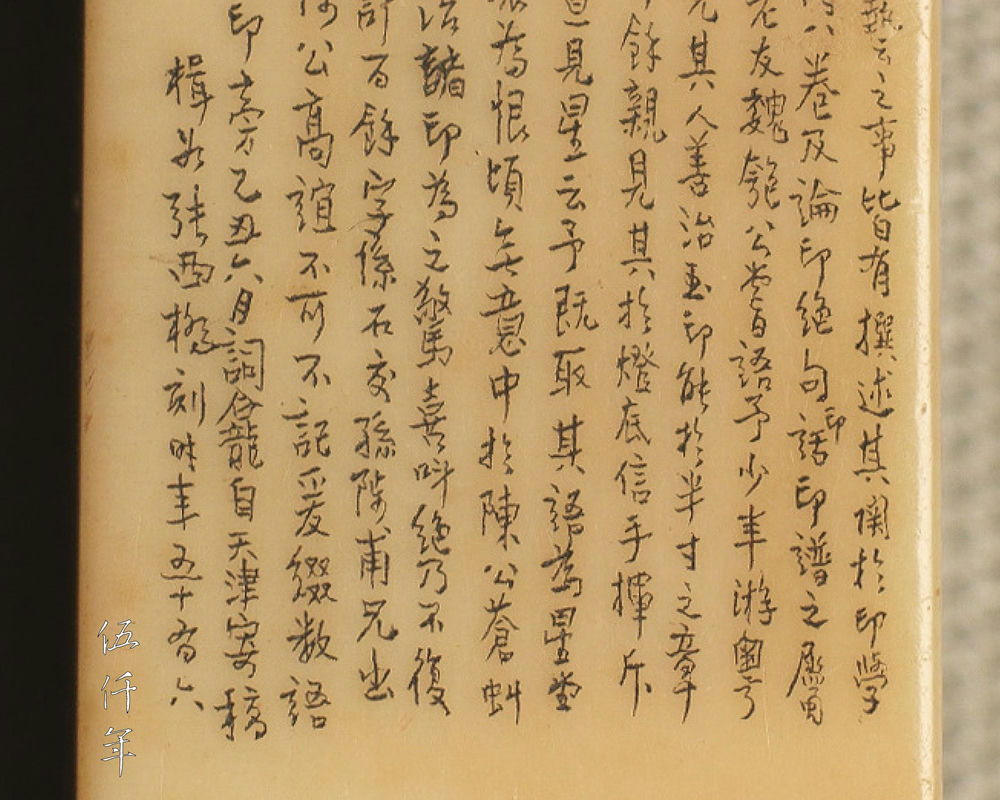

Enlarged side inscription of the ivory seal by Chang Chi-ju. From the Collection of Lai-yen T’ang

Enlarged side inscription of the ivory seal by Chang Chi-ju. From the Collection of Lai-yen T’ang

Enlarged side inscription detail of the ivory seal by Chang Chi-ju. From the Collection of Lai-yen T’ang

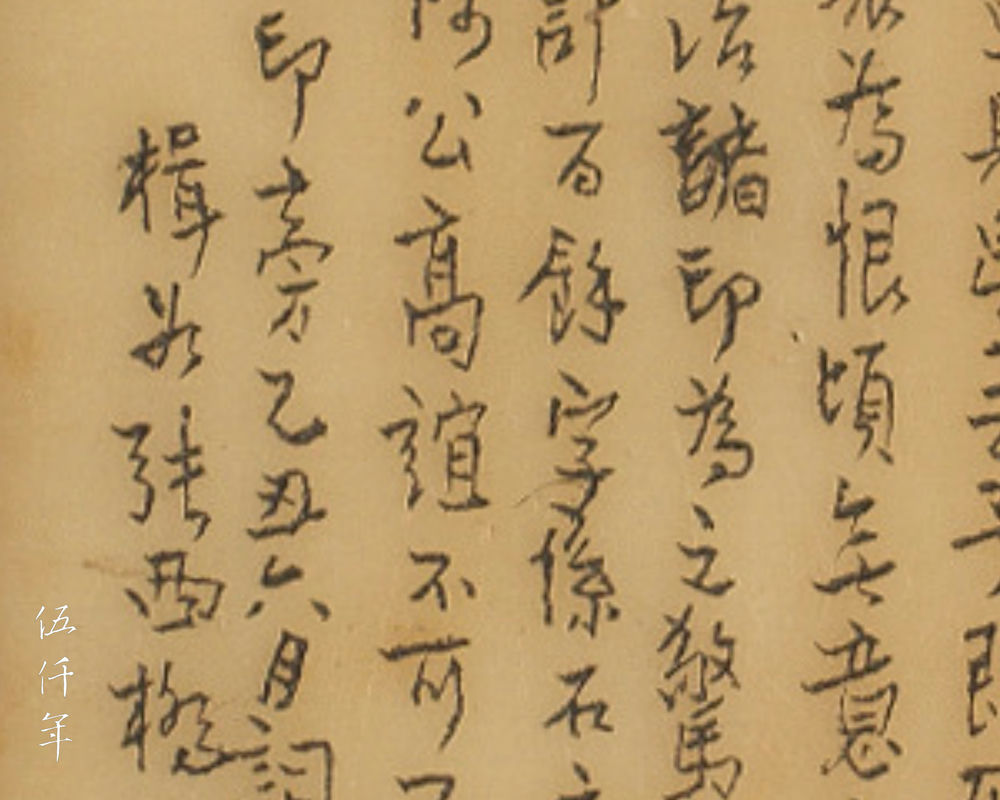

The side inscription on the seal reads:

“Since the change of dynasty, I have sought sojourn in Tientsin. For literary and artistic pursuits, I have written a number of works. On the subject of seal studies, there is A Supplement to the Biographies of Seal Engravers from Tz’u-ni An (紫泥庵補印人傳) in eight volumes, as well as six to seven other books, including a compilation of four line poems on seals, anecdotes on seals and compilations of seal impressions. Somehow, they are shared and copied by friends. My old friend Mr. Wei P’ao (魏匏) once recounted that in his youth he travelled in Kwangtung, he met Liang Hsing-t’ang (梁星堂), also known as Yüan-kuang (垣光), who excelled in carving jade seals. Liang could engrave one hundred forty to one hundred fifty characters on a seal only half an inch square. At that time he was already over sixty years old. Mr. Wei saw him at work by a lamp with his own eyes, he casually but speedily moved his hand, the carving knife as if in flight. It was said that he could see the stars in broad daylight. Since I have accepted Mr. Wei’s suggestion to write a biography for Liang Hsing-t’ang, it is a cause of deep regret that I do not see any of his works. Recently I saw Mr. Ch’en Ts’ang-ch’iu (陳蒼虯,名曾壽 1877-1949) during his travels and inadvertently saw a few seals engraved by Chang (張) from P’i-ling that belonged to him. I was amazed and thrilled, then I extolled aloud. I find myself no longer fixated on Liang Hsing-t’ang. This is a seal to denote works in my art collection. It was engraved with over a hundred words. My seal companion Sun Chih-fu (孫陟甫) commissioned Chang to carve this seal as a gift. The magnanimous friendship of Mr. Sun should not be unrecorded. Hence I wrote some words as adornment and asked Chang to engrave them on the side of the seal. Tz’u-k’an sent this draft from Tientsin in June, i-ch’ou (乙丑) year.

Engraved by Chi-ju (楫如), Chang Hsi-ch’iao (張西橋), at the age of fifty six.”

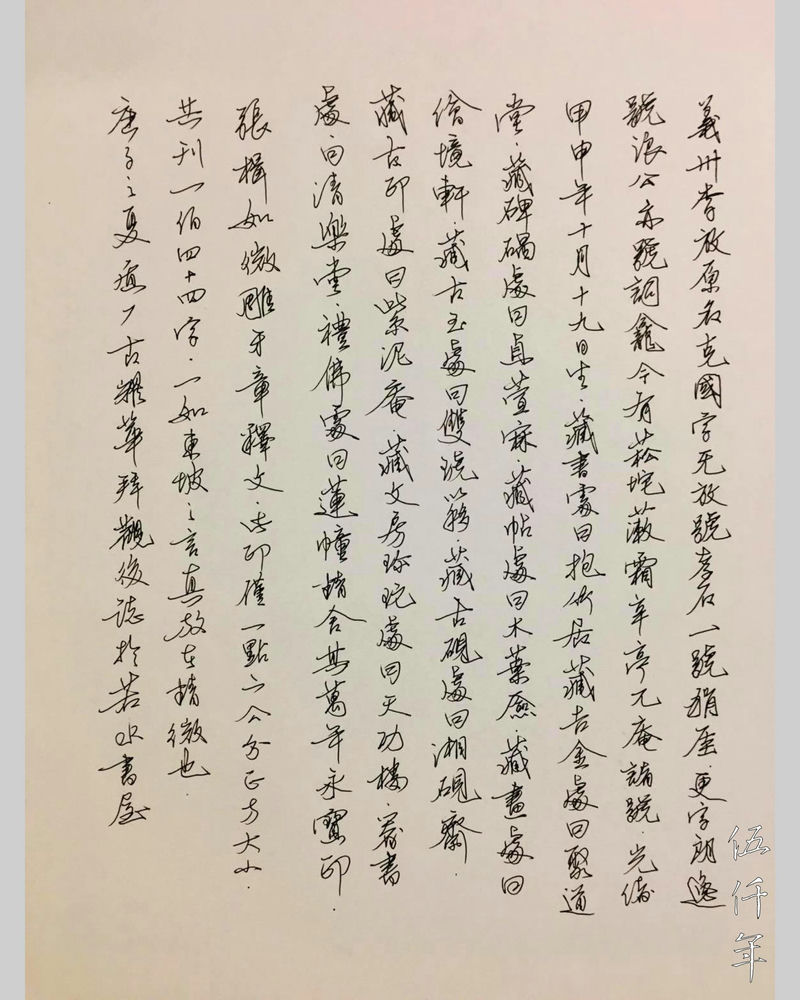

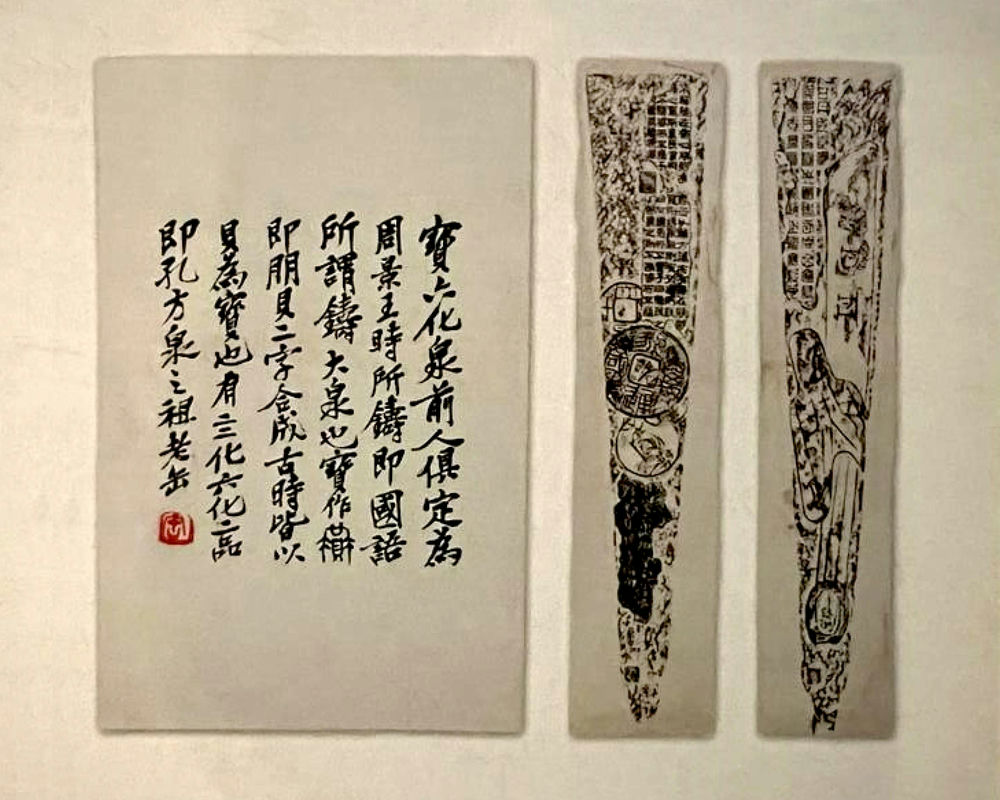

Transcript of the engraved characters on the seal written by the author of this article

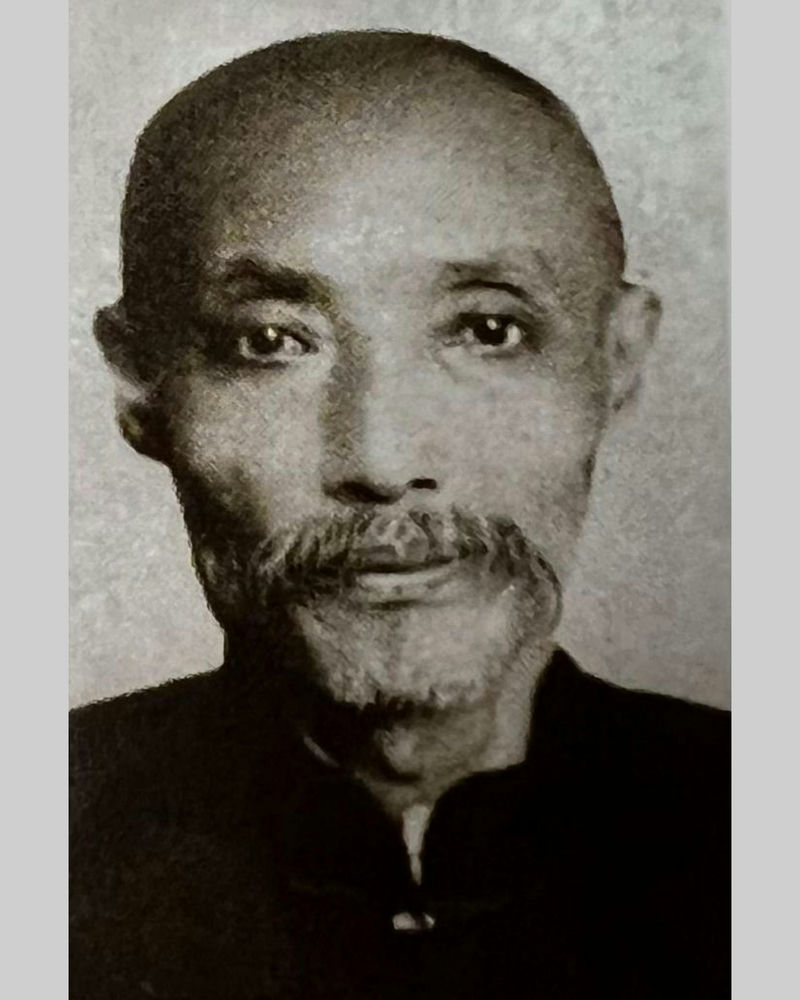

This seal was engraved by the eminent bamboo engraver Chang Chi-ju (張楫如 1870-1925) who was active in late Ch’ing and the early Republican period. His tzu was Yü (鈺), hao Hsi-ch’iao (西橋), native of P’i-ling, Kiangsu Province. The inscription he engraved was dated i-ch’ou (乙丑) year, the equivalent of 1925 according to the Gregorian calendar. It was also the year of his death. He was fifty six years old.

Portrait of Chang Chi-ju. Photograph courtesy Mr. Kuo Hai

The inscription was composed by Li Tz’u-k’an from I-chou, who was also the original owner of this seal. His friend Wei P’ao at one time met an extraordinary seal carver by the name of Liang Hsing-t’ang. Liang excelled in engraving jade seals and small seals in late Ch’ing. Another contemporary of Wei and Liang, the seal collector P’an Fei-sheng (潘飛聲 1858-1934) once wrote an essay that eulogized those seals that were engraved with many characters by Liang. Even at the age of sixty, Liang could carve one hundred forty to one hundred fifty characters on a square surface of half an inch. (One Chinese inch is equal to 3.7 cm, so half an inch is 1.85 cm.) One of the passions of Li Tz’u-k’an was seal collecting, and naturally he coveted the seals by Liang. However when he inadvertently came across the seals by Chang in the collection of Ch’en Ts’ang-ch’iu, he was so enthralled that he no longer sought the seals of Liang. Later on, his friend Sun Chih-fu commissioned Chang to carve a seal as gift.

The words of the seal not only recorded the birthday, original name, the many tzu and hao of Li Tz’u-k’an, they also chronicled the names of the places where he stored books, paintings, seals, jades, inkstones, ink rubbings, objets de virtu, etc. Li Tz’u-k’an was overjoyed with the gift, hence he composed a piece of writing and asked Chang Chi-ju to engrave it. Ch’en Ts’ang-ch’iu mentioned in the inscription was an eminent official and loyalist of the Ch’ing dynasty, one of the few admired friends of the illustrious literatus P’u Ju (溥儒 1896-1963).

Although the seal is small, it is a meticulous piece of work. The words and inscription involve a number of people and describe quite a few stories. They are fascinating to read. Apart from its literary merit, I am most awed by the engraver’s exceptional artistry, his finesse and balance. In recent years, one of my goals as a seal engraver is to develop more rigorous carving on small seals than those by my predecessors. That night after cleaning up the seal, it dawned on me that I might as well give up this effort! Some friends have praised the precision of my small seals, some fellow engravers have been self-satisfied about engraving seals less than one square centimeter. Studying this seal together that night, it was impossible to know the thoughts they derived, nor the observations they induced. In the presence of a master from the past, I only know for certain that my skill is meritless. I will not dare to describe my work as “art”, they are likely unworthy even as “craft”. I am truly humbled by his fathomless talent.

The ivory seal Chang Chi-ju engraved is 1500 mg in weight. On a surface of 1.44 square centimeters, one hundred and forty four characters were engraved. These characters constitute the personal seal of Li Tz’u-k’an. The side inscription consists of two hundred and forty seven characters. These characters record the story of his friend giving him the seal.

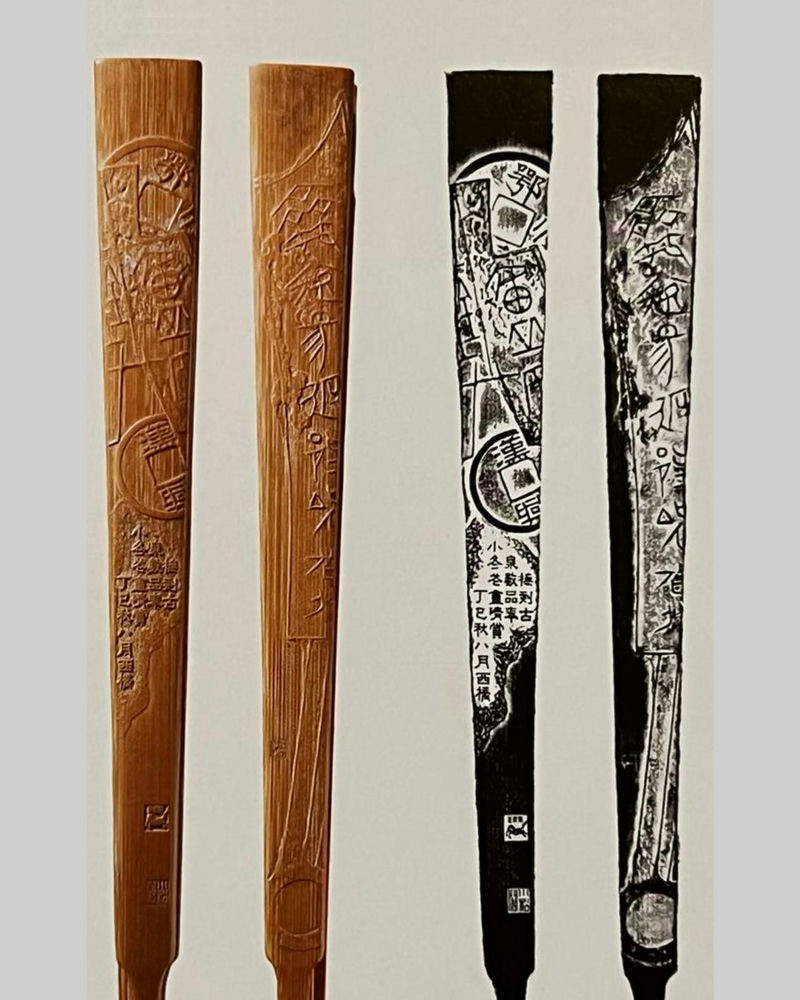

First set of bamboo guards of folding fan engraved with the designs of ancient coins by Chang Chi-ju. Photograph courtesy Shanghai Museum

Second set of bamboo guards of folding fan engraved with the designs of ancient coins by Chang Chi-ju. Photograph courtesy Shanghai Museum

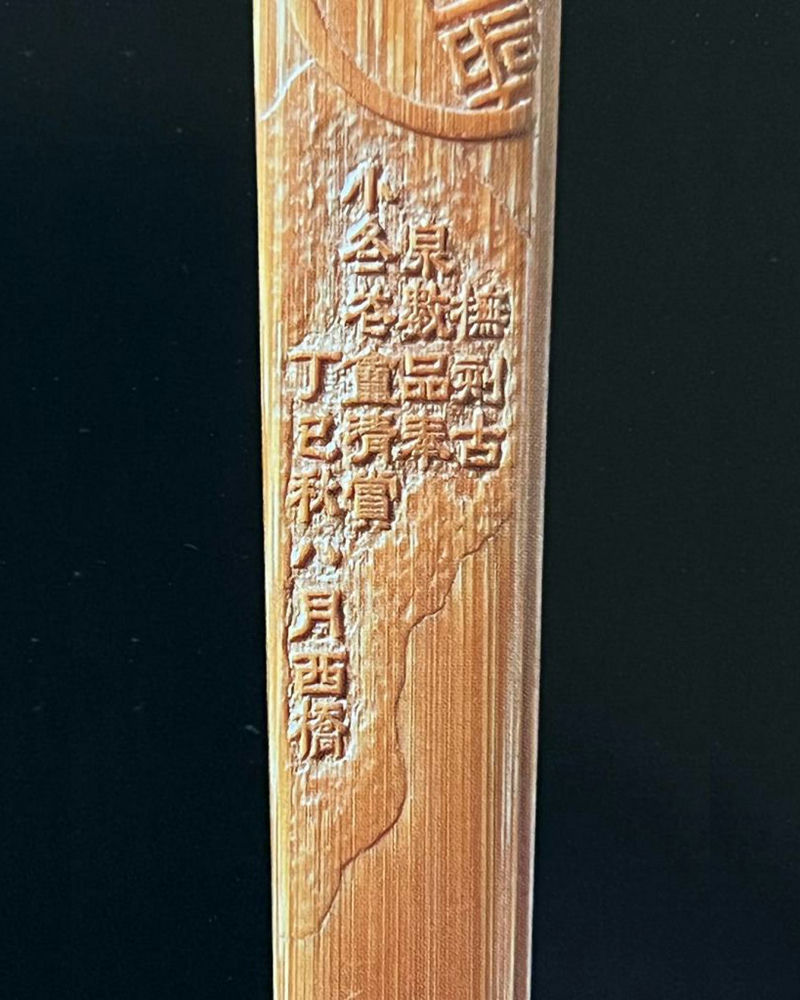

Detail of the second set of bamboo guards of folding fan engraved with the designs of ancient coins by Chang Chi-ju. Photograph courtesy Shanghai Museum

The splendour of bamboo engraving by Chang Chi-ju has long been lauded. However it is unfortunate that authentic and undisputed works by him are rarely seen. There are some in The Palace Museum in Peking. From what I know, two sets of bamboo guards from two folding fans in the Shanghai Museum have been exhibited and published. The actual number of pieces by Chang in the Shanghai Museum is unclear. Sometimes works attributed to him are available in the market, but my appraisal is inadequate, and I will not brave making decisions on authenticity.

Fortunately this seal collector friend recently provided me with some photographs of authentic bamboo engravings by Chang. There are three sets of bamboo guards from three folding fans and a bamboo wrist rest for writing calligraphy. They are all in the collection of Chang’s grandson, Chang Tsung-hsien (張宗憲).

Bamboo wrist rest and bamboo guards of folding fans engraved by Chang Chi-ju in the collection of his grandson. Photograph courtesy Mr. Chang Tsung-hsien

Chang Tsung-hsien is a well known antique dealer, trading mainly in calligraphy, painting, ceramics and works of art. His interest in art may be derived from his heritage. His father Chang Chung-ying (張仲英) had ten children. The eldest son Chang Yung-fang (張永芳) is an architect living abroad. Chang Tsung-hsien the second child, his younger sister Chang Yung-chen (張永珍), and youngest brother Chang Tsung-ju (張宗儒) all inherited the connoisseurship of the father and the grandfather.

In the 2nd year of the Hsüan-t’ung reign (1910), two years before the founding of the Republic of China, Chang Chi-ju at the age of forty, took his twelve year old son Chang Chung-ying and moved to Shanghai. In the 3rd year of the Republic (1914), when Chang Chung-ying was sixteen, Chang Chi-ju took over an antique shop by the name of Chü-chen Chai. They managed the shop together for two years, when Chang Chung-ying was eighteen, he was given full reign and became the youngest antique dealer around Shanghai. Chang Chi-ju excelled in engraving bamboo guards of folding fans with many characters. For a set of bamboo guards half an inch wide, he frequently engraved hundreds of characters with utmost precision.

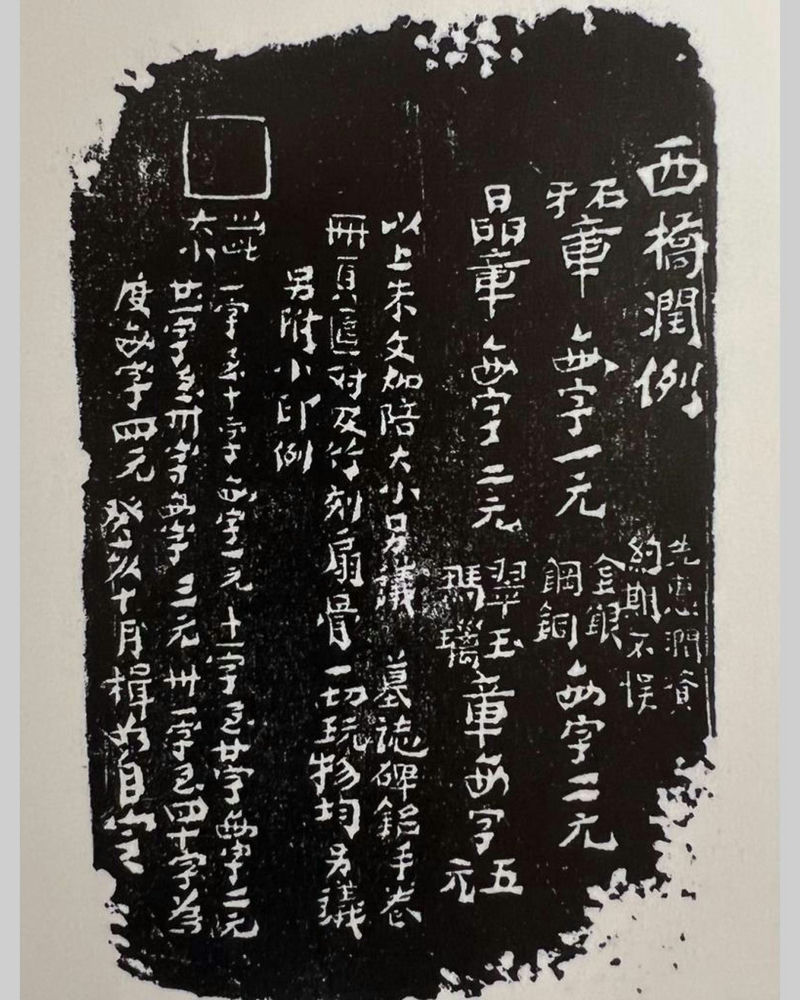

Ink rubbing of the price list for commissioned works by Chang Chi-ju. Photograph courtesy Mr. Kuo Hai

This ivory seal I examined recently was engraved in the final year of his life. Such display of virtuosity validates the substance of his stature. Now I have seen the few pieces of bamboo engraving by Chang Chi-ju in the collection of his descendant, they are indeed additional evidences of his artistry. Following the footsteps of the middle to late Ming master bamboo engraver P’u Chung-ch’ien (濮仲謙), as well as those master bamboo engravers from Chin-ling and Chia-ting districts, the artistries of the bamboo engravers in late Ch’ing reached a new pinnacle. Chang Chi-ju was one of the luminaries. He was also acclaimed by the senior artist Wu Ch’ang-shuo (吳昌碩 1844-1927) and his contemporary Chu Te-i (褚德彝 1871-1942). This is possible only with exceptional proficiency.

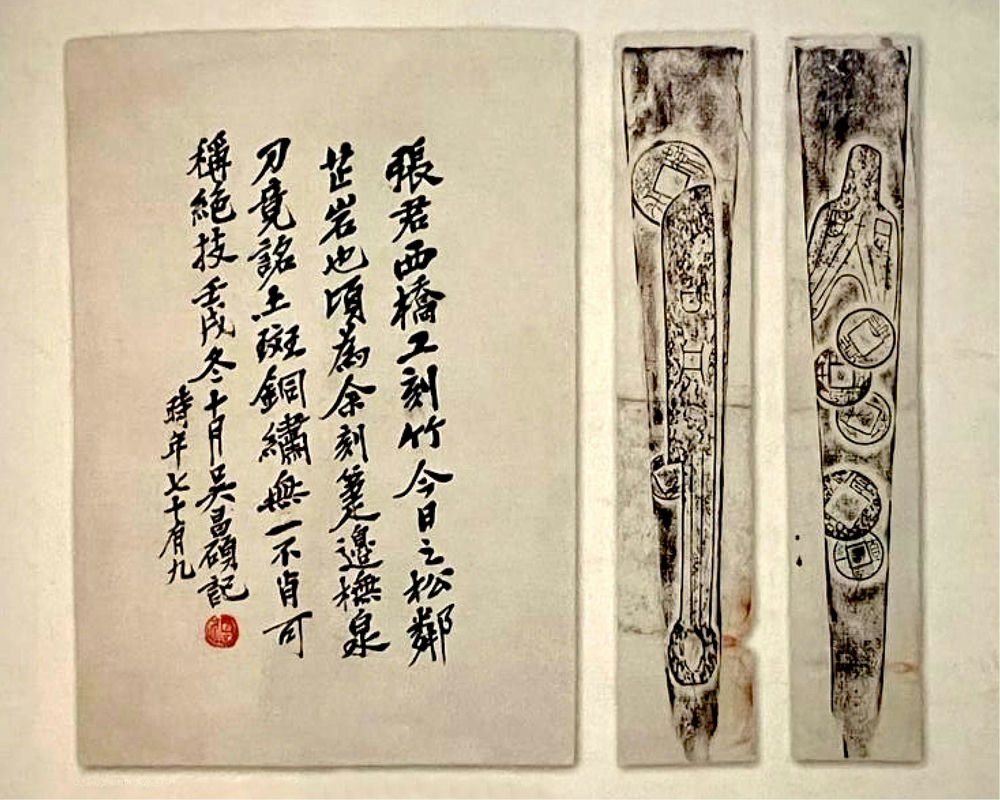

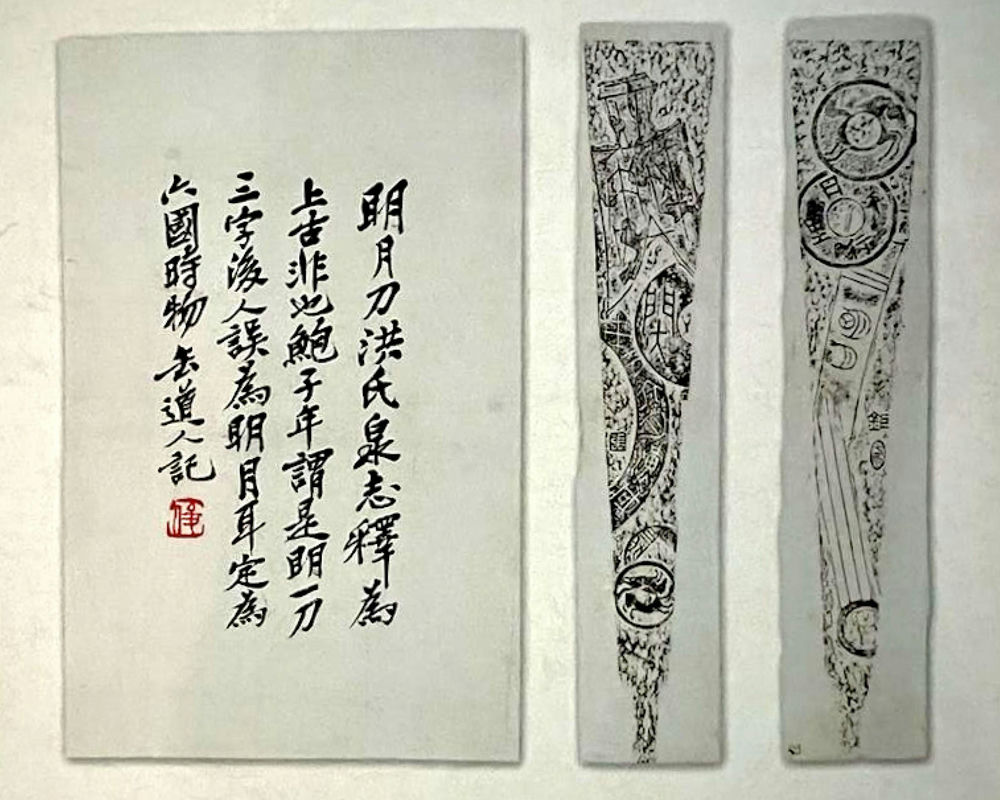

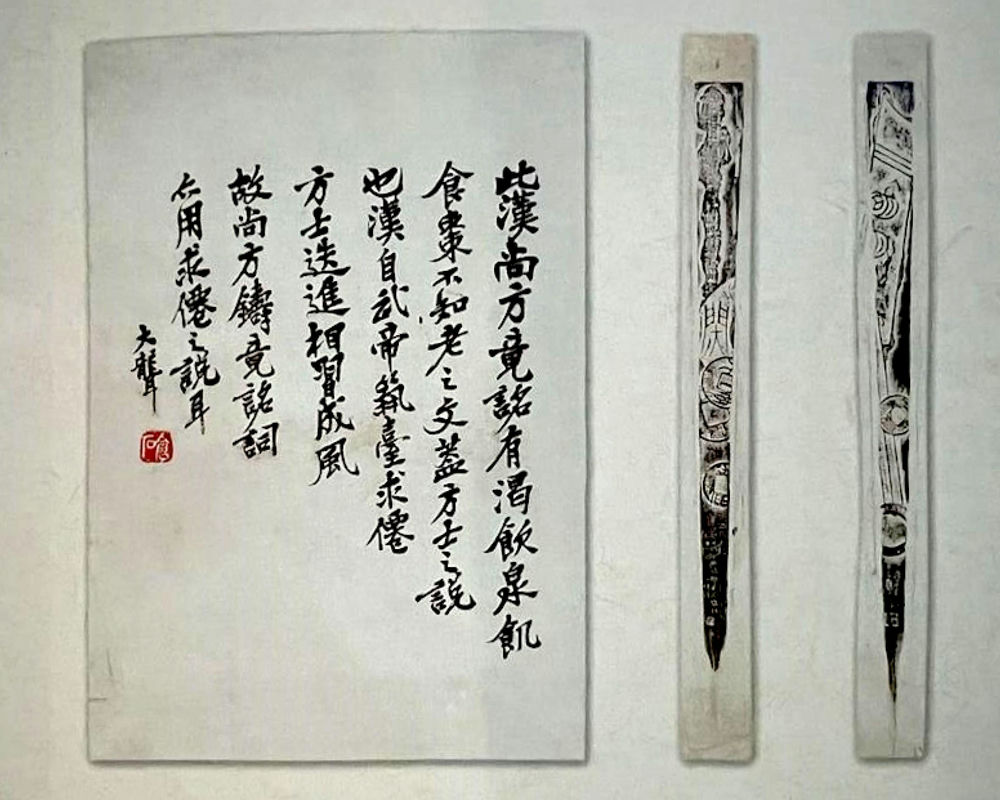

The material my seal collector friend provided also included photographs of ink rubbings, there are four sets of bamboo guards from four folding fans engraved by Chang Chi-ju. On the side of each set of ink rubbings, there is an inscription by Wu Ch’ang-shuo. This is testimony of the friendship between Chang and Wu fostered by artistic interests. Examining the ink rubbings, Chang employed the forms of ancient coins on all four pairs, one of them was supplemented with relief characters. They are exquisite.

Chang could write a style of seal script from ancient drum shaped steles. One speculates that this is due to his admiration for Wu Ch’ang-shuo.

Ink rubbing of first set of bamboo guards of folding fan engraved by Chang Chi-ju with inscription by Wu Ch’ang-shuo on the side. Photograph courtesy Mr. Chang Tsung-hsien

Ink rubbing of second set of bamboo guards of folding fan engraved by Chang Chi-ju with inscription by Wu Ch’ang-shuo on the side. Photograph courtesy Mr. Chang Tsung-hsien

Ink rubbing of third set of bamboo guards of folding fan engraved by Chang Chi-ju with inscription by Wu Ch’ang-shuo on the side. Photograph courtesy Mr. Chang Tsung-hsien

Ink rubbing of fourth set of bamboo guards of folding fan engraved by Chang Chi-ju with inscription by Wu Ch’ang-shuo on the side. Photograph courtesy Mr. Chang Tsung-hsien

There is a Chinese axiom “Different profession is like different mountain”. When this is applied to the arts, it is testimony that it is hard to master the various branches. Although there have been individuals who excelled in numerous arts since ancient times, they are nonetheless rare. Most people only manage to focus on one single art in their lifetimes, even then they achieve nothing.

A case is Chang Chi-ju, the distinguished bamboo engraver of late Ch’ing and the early Republican era. Even though he excelled in carving minuscule seal and attained superior standard, he still could not establish a reputation in seal engraving. When placed in the field of microscopic ivory engravings, he did not attain the same prominence as the other microscopic carvers like Yü Shuo (于碩) and Wu Nan-yü (吳南愚) neither. Yet his eminence in bamboo engraving is not diminished in anyway despite the rarity of his extant works. This is to do with the creative focus of an artist, later generations also apply this as a basis for assessment and evaluation.

Enlarged side inscription detail of the ivory seal by Chang Chi-ju. From the Collection of Lai-yen T’ang