Chou Lien-hsia (周鍊霞) excelled in poetry, tz’u, calligraphy and painting. She was celebrated in the early years of the Republic China. At the time, Chou Lien-hsia was alone amongst females in mastering all these fours literary and artistic endeavors. Whenever a female acquired eminence in literature or art, those who are inquisitive like to collect gossips through the grapevine, and fictionalize her biography. The historian Mr. Ch’en Lun (陳崙) hence publishes a long letter by Chou Lien-hsia at the Chinese-Heritage Virtual Museum. In her own words, this letter recounts her family history, family affairs and friendships. It will revise many errors by a number of contemporary biographers, and will indeed be cherished by researchers like a piece of jade ruler.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

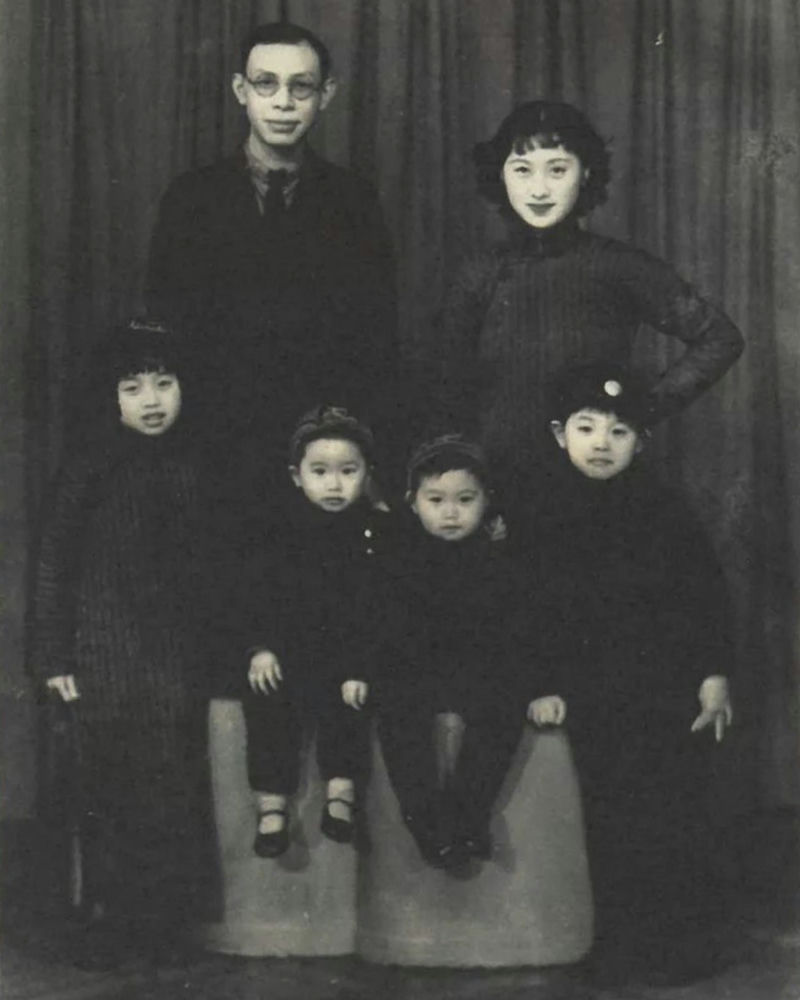

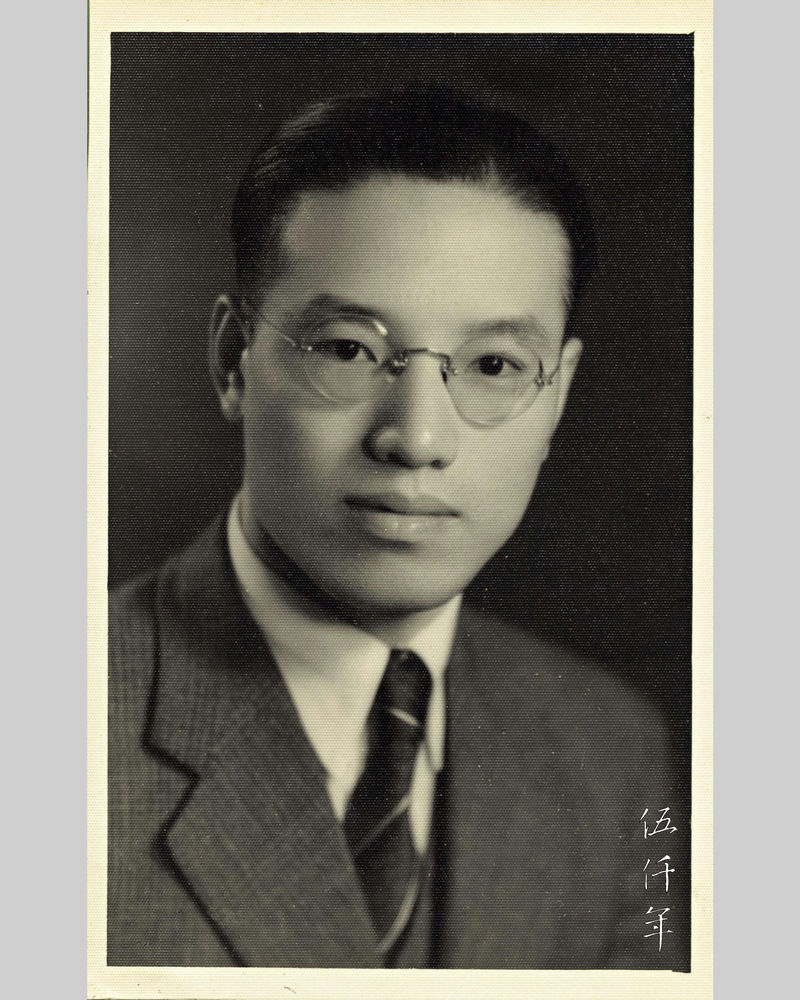

Portrait of Chou Lien-hsia

In the last century, Chou Lien-hsia (周鍊霞) was the only female universally celebrated for poetry, tz’u lyrics, calligraphy and painting.

She was born on 16 September 1909 and passed away on 13 April 2000. Her original names were Ch’en (茞), Yü (霱), Tzu-i (紫宜); her tzu were Lien-hsia (煉霞), Lien-hsia (鍊霞); her hao were Lo-ch’uan (螺川), Lo-ch’uan-tzu (螺川子); her studio names were Ch’an-hung Hsüan (懺紅軒), Lo-ch’uan Shih-wu (螺川詩屋). She was a native of Chi-an, Kiangsi Province.

Her father Chou Shou-ch’i (周壽祺), tzu Ho-nien (鶴年), attained the chü-jen degree (provincial graduate) and was appointed magistrate of Ch’ang-sha, Hunan Province. Hence when she was four, Chou Lien-hsia relocated to Hunan with her family. She began her schooling at five. Yet when she was nine, she relocated to Shanghai because of unrest in Ch’ang-sha. Her early education was moulded by her father. At fourteen, she studied painting under Cheng Te-ning (鄭德凝). At seventeen, she studied tz’u lyrics under Chu Tsu-mou (朱祖謀) and poetry under Chiang Chao-hsieh (蔣兆燮) from I-hsing, Kiangsu Province.

In the 23rd year of the Republic (1934), she joined Chung-kuo Nü-tzu Shu-hua Hui (Chinese Female Calligraphers and Painters Society 中國女子書畫會) and became a professional painter. She was also an active member of the literary salons formed by an earlier generation of poets. During the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression from 1937 to 1945, she continued to live in Shanghai.

In the 38th year of the Republic (1949), mainland China fell to the communists. She stayed in Shanghai and subsequently lived through waves of purges. During the Cultural Revolution, she was severely beaten by the Red Guards and one of her eyes went blind. In the 69th year of the Republic (1980), she left mainland China for the United States. Her works are titled The Rhythmic Words of Lo-ch’uan (螺川韻語).

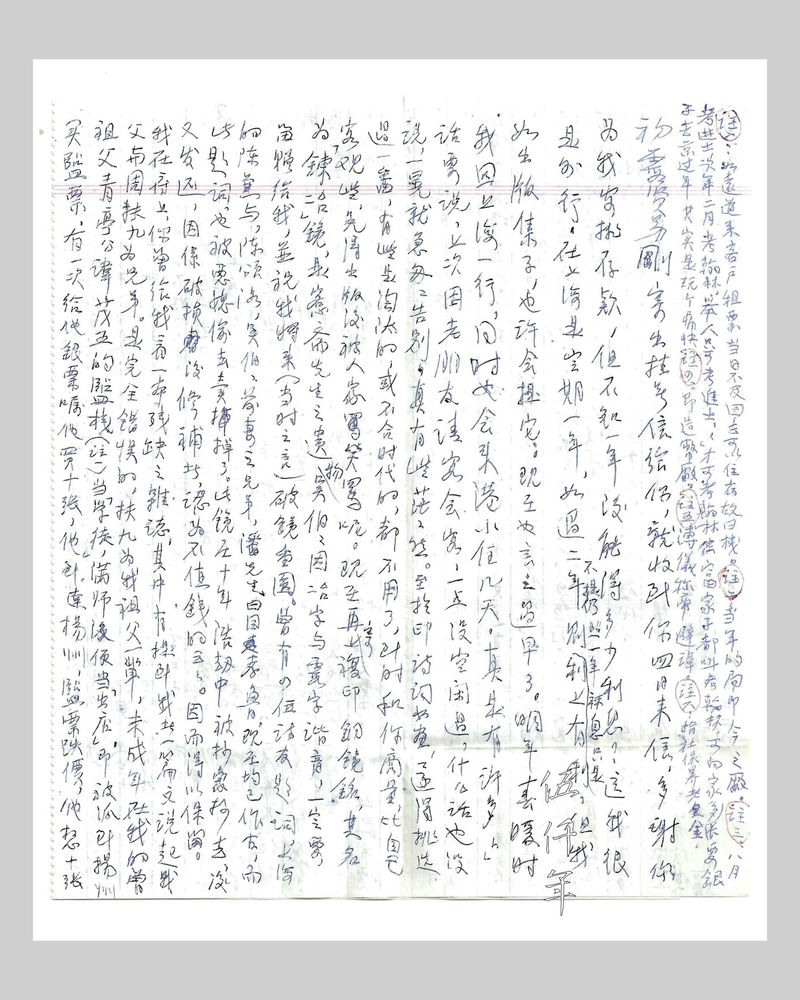

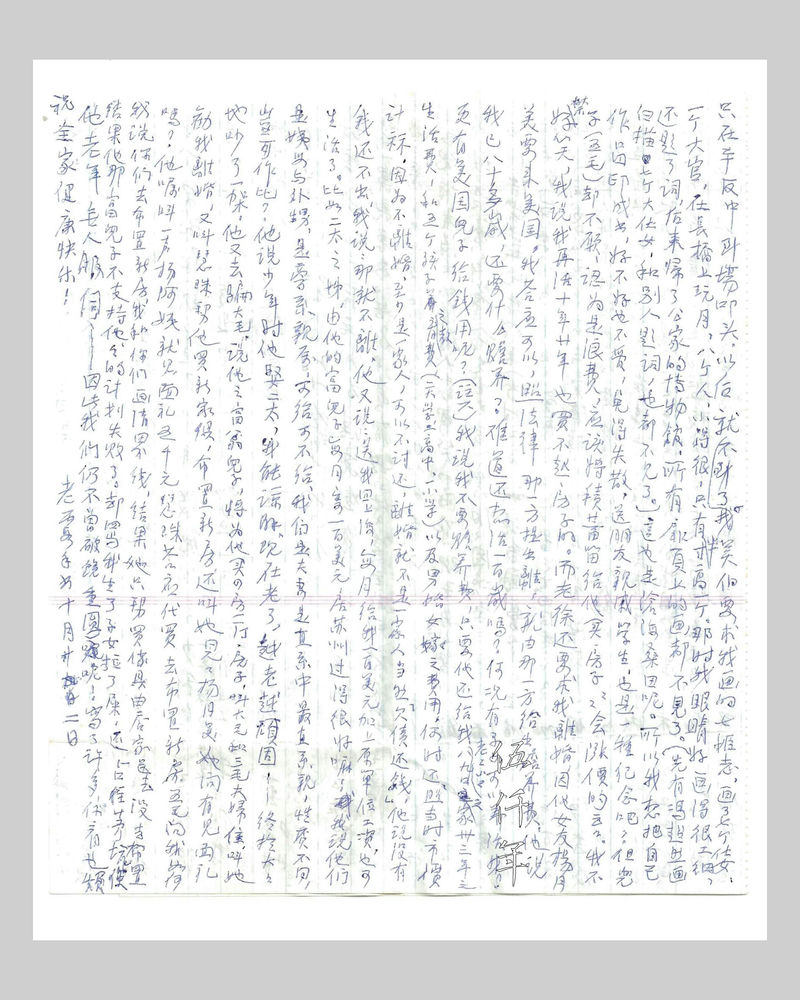

Amongst the letters by Chou Lien-hsia to her student P’ing Ch’u-hsia (平初霞), there is a four page letter which describes in detail some of her life stories. It is of great documentary value.

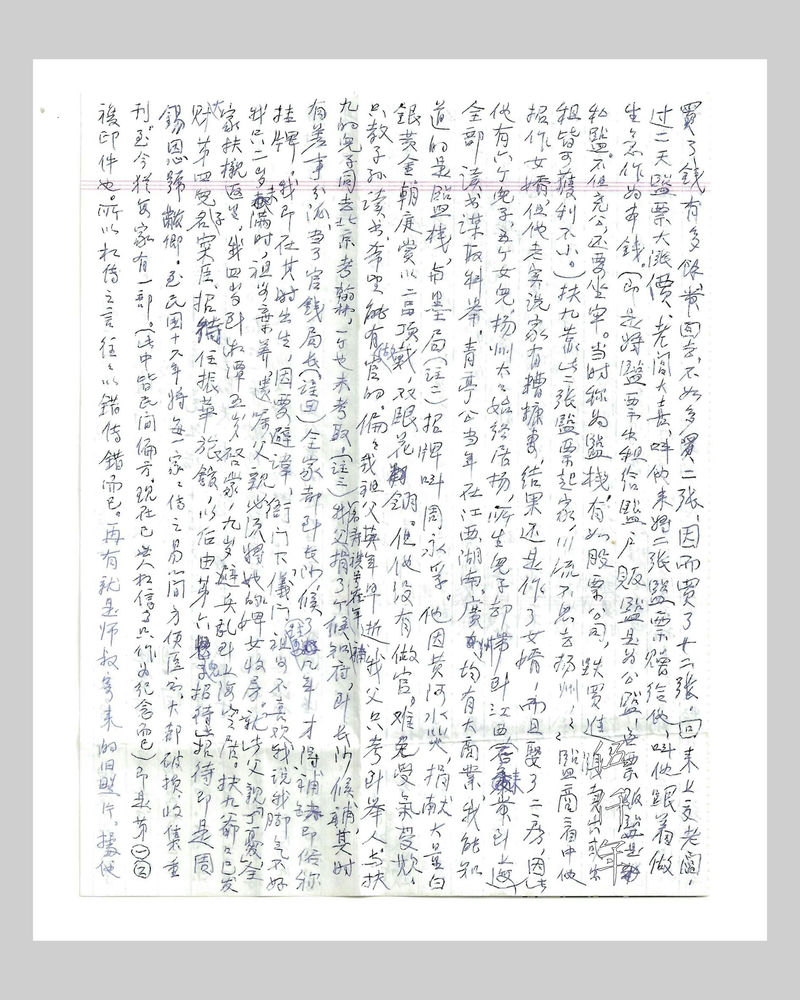

First page of letter by Chou Lien-hsia to P’ing Ch’u-hsia

The letter reads:

“Ch’u-hsia my younger friend,

After sending you a registered letter, I soon received your letter from the fourth. Thank you for arranging my bank deposit. What is the annual interest rate? I am a layman of banking. In Shanghai I had a one year fixed deposit account. If money was not withdrawn after two years, the interest rate would remain the same as the one year deposit, but it is cumulative. However when I publish the volume of my works, I may withdraw the money. It is still premature to know. In spring next year when it is warmer, I will make a trip back to Shanghai. I will also come to Hong Kong and stay for a few days. I have so much to tell you. On my last trip with invitations to meals and meetings from old friends , there was not a moment of idleness. We did not talk at all. In a flash I hurriedly said goodbye to you, there is such a sense of loss.

Note: Four years after the end of the Cultural Revolution, in 1980, Chou Lien-hsia left mainland China. She first arrived in Hong Kong, stayed there for a while, and then went to the United States. In the following years, she returned to Hong Kong a number of times to see old friends. This letter was written in the late 80s.

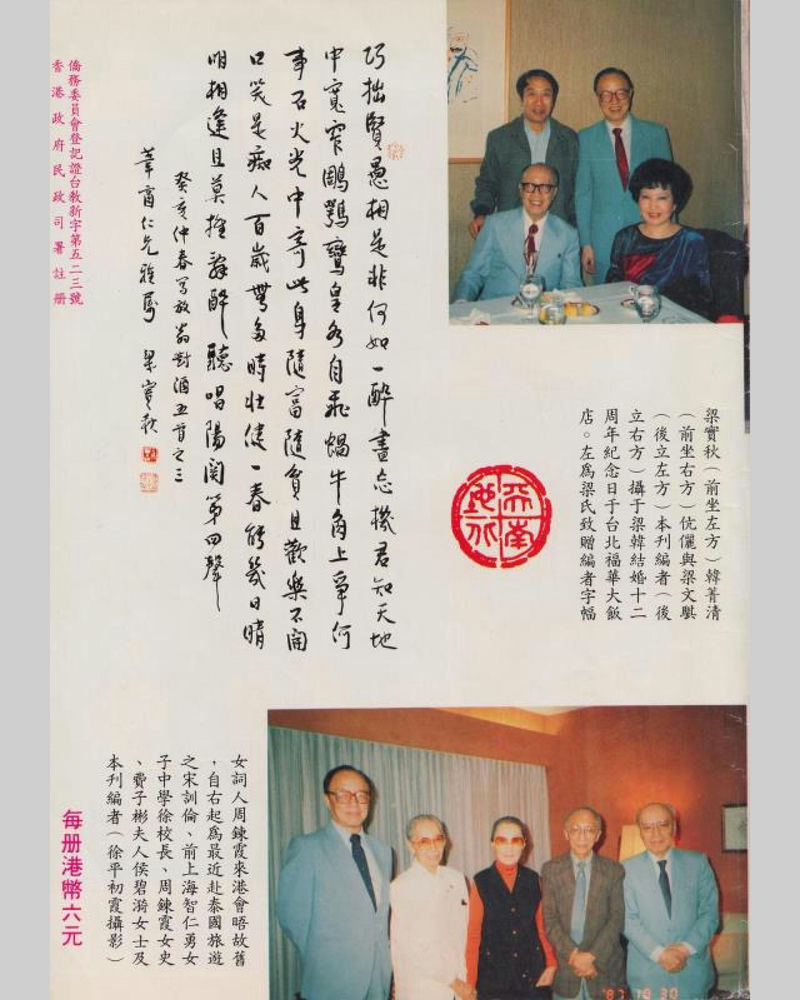

News of Chou Lien-hsia visiting Hong Kong in the 1 December 1987 issue of Ta-ch’eng Magazine

As for the volume of my works that consists of poetry, tz’u lyrics, calligraphy and painting, I still need to select those paintings for inclusion, and those to be cast aside. Those that do not resonate well with the times will also be discarded. I will discuss with you then. You are more objective than myself. I can then avoid mockeries and rebukes after its publication.

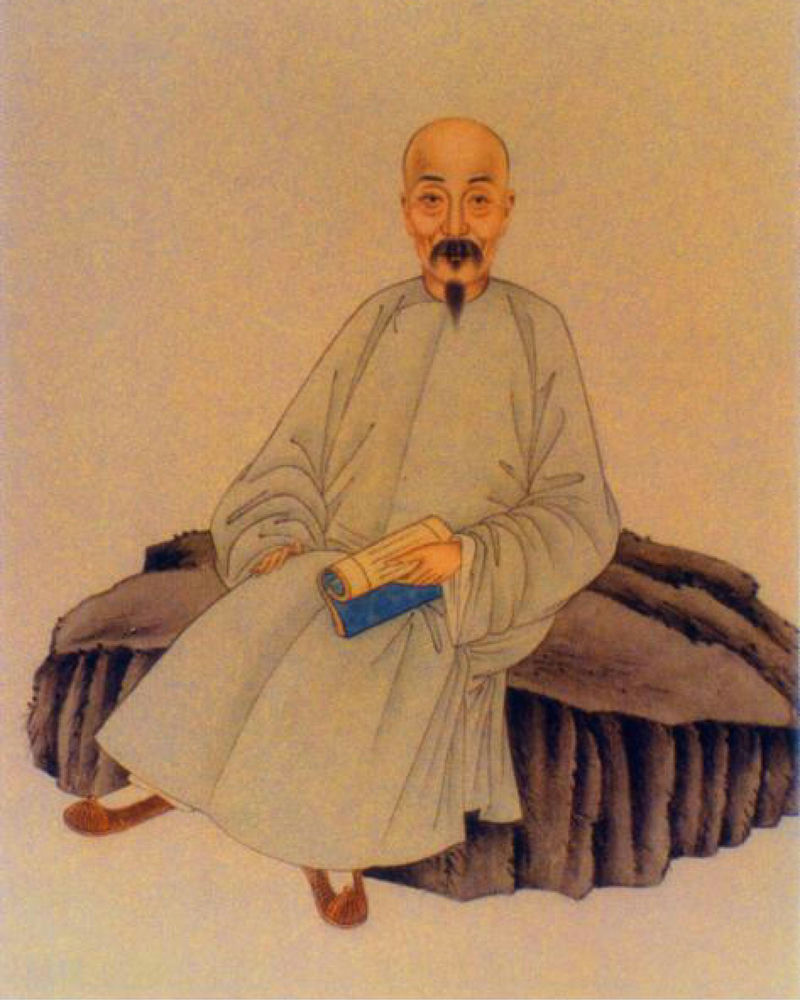

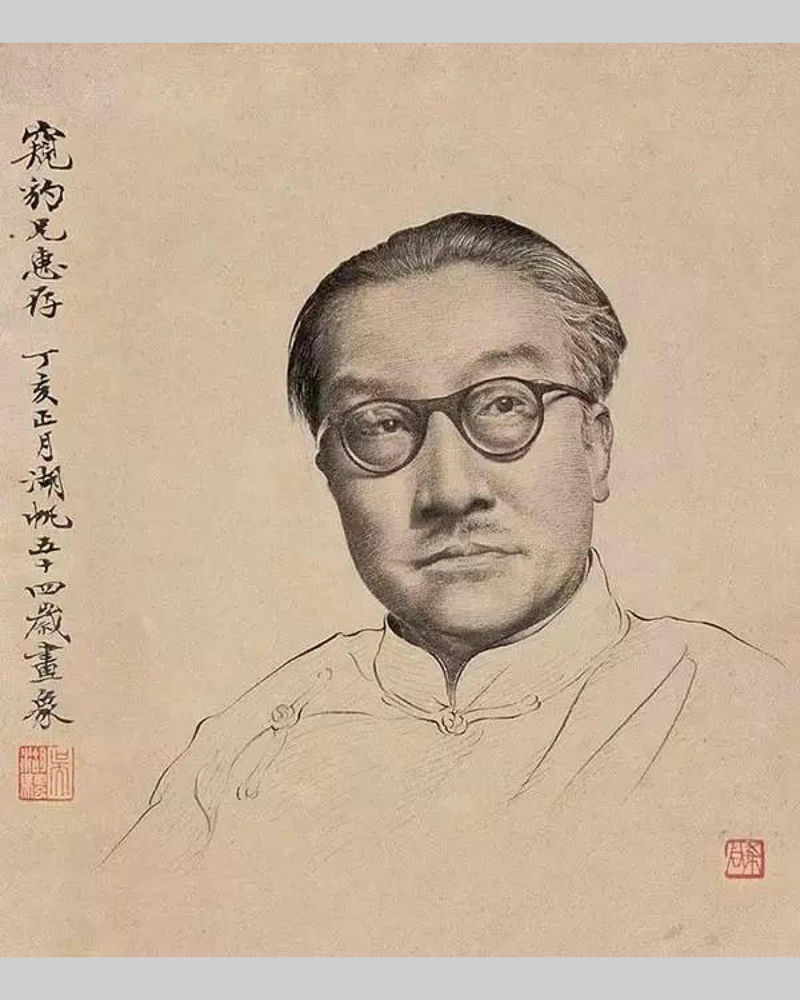

Portrait of Wu Ta-ch’eng

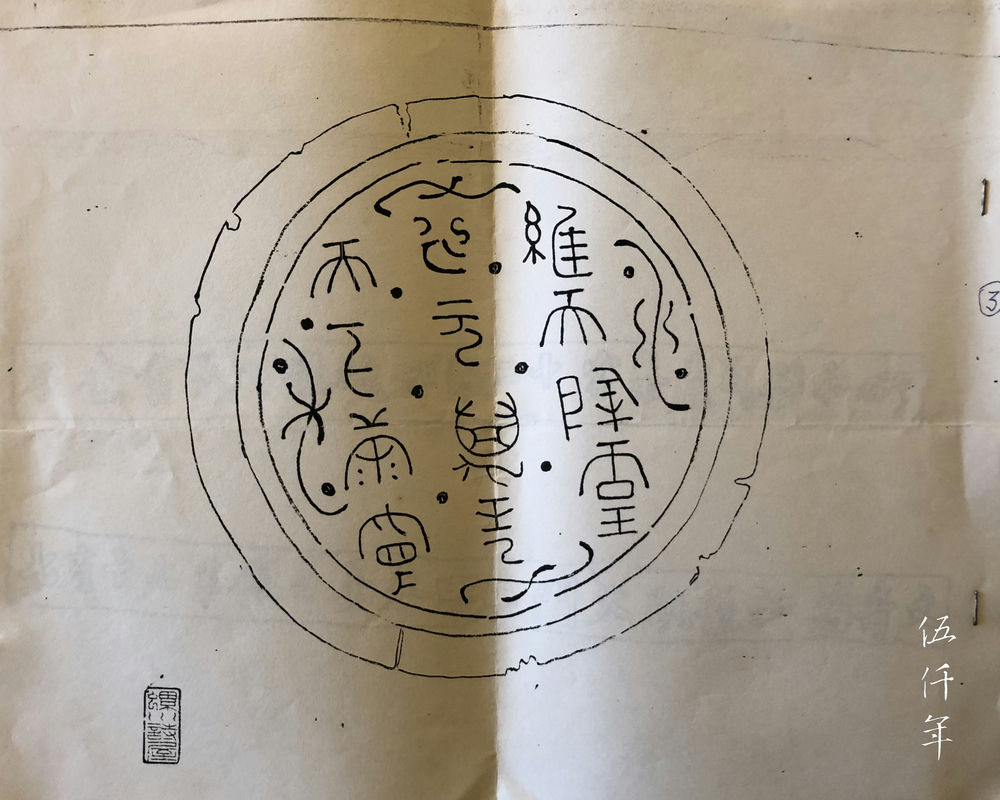

I am now enclosing a photocopy of the inscription of a bronze mirror. The bronze mirror is named “Lien-yeh (鍊冶) Mirror”, formerly in the collection of Mr. Ch’üeh-chai (愙齋). Since the pronunciations of the character yeh (冶) and the character hsia (霞) are homophonic, Uncle Wu insisted that I should accept it as a gift. He said to me at the time that one day I would "restore the full circle of a shattered mirror".

Note: Ch’üeh-chai (愙齋) was Wu Ta-ch’eng (1835-1902), tzu Ch’ing-ch’ing (清卿), hao Ch’üeh-chai, native of Su-chou, Kiangsu Province. He was consecutively appointed provincial education commissioner of Shensi Province, governor of Kwangtung Province and governor of Hunan Province. He was proficient in calligraphy and painting, and excelled in connoisseurship.

Uncle Wu was Wu Hu-fan (吳湖帆 1894-1969), original name Ch’ien (倩), hao Ch’ien-an (倩庵), pseudonyms Ch’ou-i (丑簃) and Hu-fan, studio name Mei-Ching Shu-wu (梅景書屋), native of Su-chou, Kiangsu Province. He was the grandson of Wu Ta-ch’eng. He was proficient in calligraphy and painting, and excelled in connoisseurship.

To "restore the full circle of a shattered mirror" was an auspicious phrase used by Wu Hu-fan to wish for the reunion of Chou Lien-hsia and her husband Hsü Wan-p’ing (徐晚蘋). Some recent writers have insinuated a romantic relationship between Chou Lien-hsia and Wu Hu-fan. This is evidence of refutation.

A photocopy of the inscription of a bronze mirror, with a seal of Chou Lien-hsia impressed at the lower left corner, stored with the letters to P’ing Ch’u-hsia. Perhaps it is the inscription of Lien-yeh Mirror

Four poetry companions from Shanghai wrote some literary compositions for the bronze mirror. They are Ch’en Chien-yü (陳兼與), Ch’en Sung-lo (陳頌洛), Mr. P’an (潘先生) the brother-in-law of Uncle Wu, and Mao Hsiao-lu (冒孝魯). They have all passed away. As for these literary compositions, they were stolen by my odious daughter-in-law and sold.

Note: Ch’en Chien-yü (陳兼與 1897-1987), original name Sheng-ts’ung (聲聰), tzu Chien-yü (兼與), hao Hu-yin (壺因), native of Min-hou, Fukien Province. He was proficient in painting and excelled in poetry. Some of his works are Chien-yü Ko shih (兼與閣詩), Hu-yin shih (壺因詩) and others.

Ch’en Sung-lo (陳頌洛 1897-1965), original name Chung-yüeh (中岳), tzu Sung-lo (頌洛), also Sung-lo (誦洛), native of Shao-hsing, Chekiang Province. He excelled in poetry and acquired a reputation in politics in the early Republican period. His works are Hsia-k’an shih-ts’un (俠龕詩存), Chuan-p’eng chi (轉蓬集) and others.

Mr. P’an was the brother of P’an Ch’ing-shu (潘靜淑 1892-1939), wife of Wu Hu-fan.

Mao Hsiao-lu (冒孝魯 1909-1988), original name Ch’ing-fan (景璠), native of Ju-kao, Kiangsu Province. Son of Mao Kuang-sheng (冒廣生 1873-1959). He excelled in poetry and tz’u lyrics.

Chou Lien-hsia had five children. It is not known who is this odious daughter-in-law.

Group photograph of Chou Lien-hsia with husband and four children

The bronze mirror was confiscated by the Red Guards when they ransacked my house during the ten year period of the Cultural Revolution. Afterwards it was returned. As it was previously damaged and repaired, the government regarded it to be worthless, thus I managed to keep it.

Portrait of Chou Fu-chiu

One time in your house, you showed me a defective magazine. There was an article about me, writing that my father and Chou Fu-chiu (周扶九) were brothers. This is completely erroneous.

Note: Chou Fu-chiu (周扶九 1831-1920), original name Chüan-p’eng (鵑鵬), tzu Tse-p’eng (澤鵬), hao Ling-yün (凌雲), native of Chi-an, Kiangsi Province. He was a prominent business tycoon in the early Republican period.

Second page of letter by Chou Lien-hsia to P’ing Ch’u-hsia

Chou Fu-chiu belonged to the generation of my grandfather. When he was a teenager, he apprenticed at the salt inn (鹽棧) of my great-grandfather Mr. Chou Ch’ing-t’ing (青亭公), whose original name was Mao-wu (茂五). (Salt inn also provided accommodation for salt traders who travelled from afar to rent salt permits. Sometimes they could not leave in time and stayed overnight, hence it was called salt inn.) After Chou Fu-chiu completed his apprenticeship, he left the salt inn and was assigned to purchase salt permits in Yang-chou, Kiangsi Province. At one time, he was given some money tokens to buy ten salt permits. When he arrived in Yang-chou, the price of salt permit had fallen. He then decided to purchase two extra salt permits, altogether a total of twelve salt permits, rather than bring back the extra money. After he returned, he handed them to the boss. After two days, the price of salt permit went up considerably. The boss was elated. He asked to see Chou Fu-chiu and gave him two salt permits. He suggested to Chou that he could become his business apprentice and the two salt permits could be used as his capital. (When salt permits were rented out to merchants for salt trade, such salt was called public salt. When salt was traded without salt permits, the contraband salt was called private salt, which would be confiscated when discovered and the merchants jailed. The salt inn operated like a stock trading company, it would buy when the price of salt permit fell. When the price of salt permit rose, selling or renting the permit could be highly profitable. Chou Fu-chiu built his fortune on the foundation of two salt permits. He travelled back and forth without respite to Yang-chou. One of the salt merchants there looked favourably upon him. He asked Chou to marry his daughter. Chou admitted in all honesty that he already had a wife at home. Nevertheless, he still married the daughter and she became his second wife. As a consequence he had six sons and five daughters. The wife from Yang-chou always stayed in Yang-chou, while her sons were taken to Kiangsi Province and later to Shanghai. They were all educated and sought qualifications in the Public Examinations.

Maker’s name of Chou Yung-fu on inkstick

Maker’s name of Chou Yung-fu and the year of manufacture on inkstick

Mr. Chou Ch’ing-t'ing owned sizable businesses in Kiangsi, Hunan and Canton at that time. Those I know of are salt inn and ink bureau (the word bureau is used as the equivalent of the word factory in our time). The brand was called Chou Yung-fu (周永孚). He contributed huge amounts of silver and gold to victims of the Yellow River flooding. The court awarded him the mandarin hat of the second rank, adorned with peacock feathers carrying the two eye pattern. However he did not take up any official position, so he could not avoid being pushed around and feeling indignant. He instructed his descendants to study, so that one of them would become an official. Contrary to expectation, my grandfather passed away when he was young. My father only attained the chü-jen degree (provincial graduate). He went to Peking with the son of Chou Fu-chiu to take part in the Hanlin Examination. (The chin-shih examination or Metropolitan Examination took place in August, and the Hanlin Examination took place in February in the following year. Only those with chü-jen degree were allowed to take part in the chin-shih examination, and only those with chin-shih degree were allowed to participate in the Hanlin Examination. But those from wealthy families called both examinations Hanlin Examination, in order to ask their parents for more money to spend New Year in Peking. In truth they just wanted to have a good time.) My father’s name was Shou-ch’i (壽褀), hao Ho-nien (鶴年). He made some monetary contribution and was appointed expectant magistrate of Ch’ang-sha. He moved there with the whole family to await posting, and occasionally there were some assignments. He was made director of the mint. After a few years waiting as expectant magistrate, he finally became magistrate. The vernacular expression was “he raised the plaque.”

Note: Chou Shou-ch’i (周壽褀 1872-1904), tzu Ho-nien (鶴年), hao Ho-ch’ao (鶴巢), Mei-yin (梅隱), native of Chi-an, Kiangsi Province. He was once appointed magistrate of Hunan Province. He was proficient in poetry and painting. He was the father of Chou Lien-hsia and imparted his learnings to her.

A landscape painting on album leaf by Chou Shou-ch’i, father of Chou Lien-hsia

A landscape painting on fan by Chou Shou-ch’i, father of Chou Lien-hsia

I was born at that time. In order to avoid using any of the characters in the Emperor’s name to show reverence, the magistrate’s office took down the character i (儀) from the architectural arch. (This was during the reign of Pu-i 溥儀). My grandfather did not like me, claiming that I was an unlucky girl. Before I reached two years old, my grandmother passed away. She instructed my father to accept her maid as his concubine. During the period of my father’s mourning, the whole family returned to our native province. I arrived in Hunan Province at the age of four, started my schooling at the age of five, and settled in Shanghai at the age of nine to evade civil war.

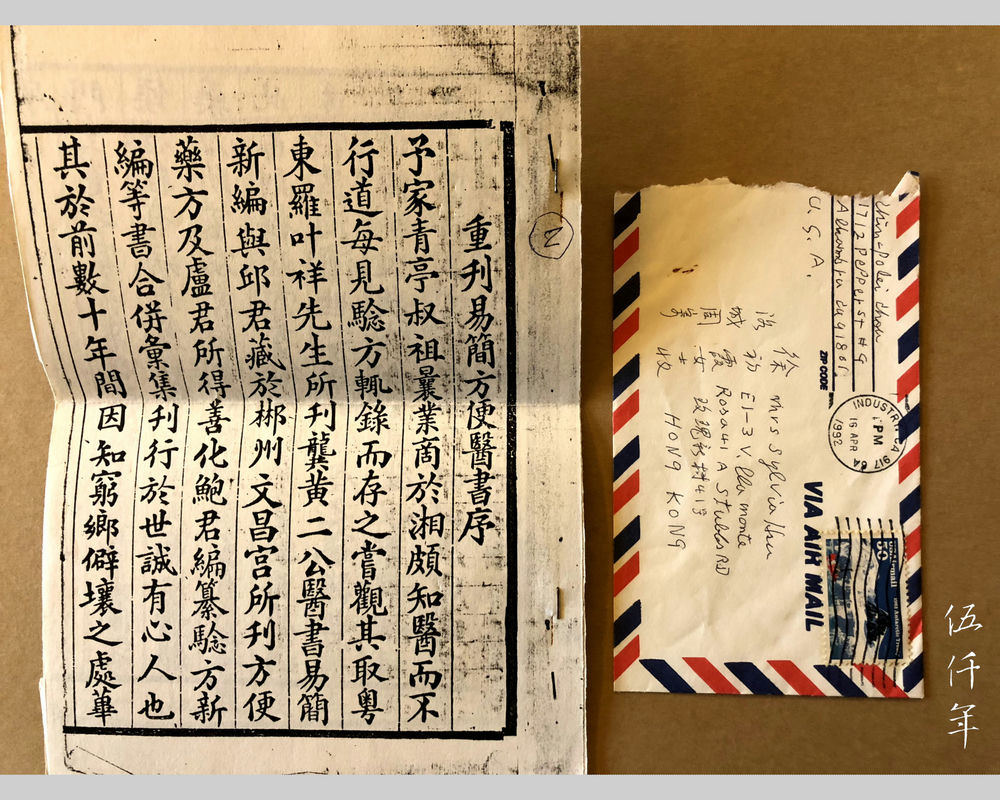

A photocopy of the Introduction to A Simple and Convenient Medical Manual by Chou Hsi-en. The book was compiled by Chou Ch’ing-t’ing, reprinted by Chou Hsi-en, son of Chou Fu-chiu in 1927

Grand-uncle Chou Fu-chiu was a tycoon by then. His fourth son Chou Ts’ai-ch’en (周寀臣) welcomed us to stay at the Ch’en-hua Hotel (振華飯店). Later his sixth son Chou Hsi-en (周錫恩), hao Fu-ch’ing (黻卿), continued the hospitality. In the 16th year of the Republic (1927) he collected the mostly damaged copies of I-chien fang-pien i-shu (A Simple and Convenient Medical Manual 易簡方便醫書) inherited by different families and reprinted it. Each family has kept a copy even now. (The Manual collected many popular medical prescriptions, but nobody believes in them anymore. It is no more than a memento.) This is illustrated by the first and second sheet of attached photocopies. So words from hearsay frequently just keep repeating the errors.

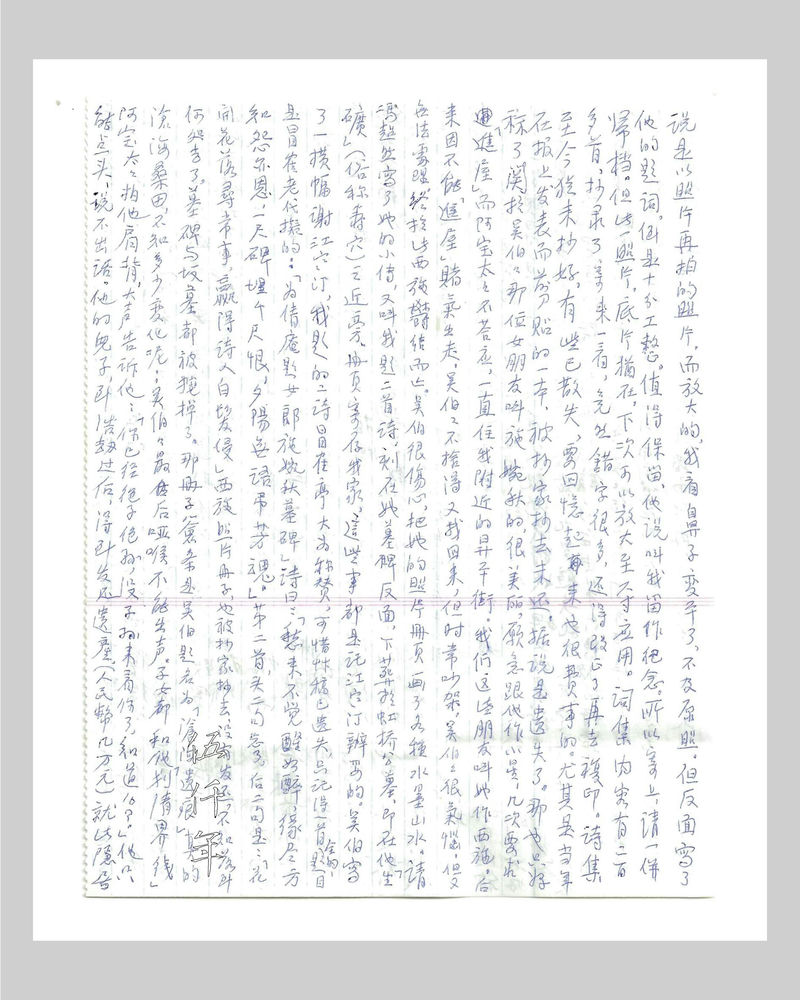

Third page of letter by Chou Lien-hsia to P’ing Ch’u-hsia

Furthermore, your teacher’s friend sent an old photograph by mail. According to him it is a photograph taken from an original photograph and then enlarged. I see my nose has become flat, it is not as good as the original photograph. But at the back, he inscribed a tz’u lyric that he composed. It was meticulously inscribed, worthy for keep. He told me to save it for remembrance, and it was for this reason he posted it. Please put it into the file. However the negative of this photograph is still extant. Next time, it can be enlarged to six inches for use.

Note: Teacher’s friend was Mr. Soong Hsün-leng (1910-2010), tzu Hsing-leng, hao Hsing-an, Yü-li, native of Wu-hsing, Chekiang Province. He excelled in tz’u lyrics. His works is titled The Fragrant Hermitage.

Portrait of Soong Hsün-leng

There are over two hundred tz’u lyrics in my tz’u anthology. I received the manuscript and found many erroneous characters. I have to revise them first and then photocopy them. I have not finished copying the poetry manuscript yet. Some poems have been lost. Trying to remember the sentences is a laborious task. Especially those published in newspapers at the time, they were cut and pasted into an album. It was taken by the Red Guards when they ransacked my home. Apparently it was lost. I can only forget about it.

Self-portrait of Wu Hu-fan

Regarding the girlfriend of Uncle Wu by the name of Shih Wan-ch’iu (施婉秋), she was beautiful. She was willing to follow him and be his starlet. A number of times, she requested that she should be accepted into the household, but the wife A-pao (阿寶) refused. Shih always lived on Sheng-p’ing Street near me. Our group of friends called her Hsi-shih (西施). As she could not be accepted into the household, she was furious and left. Uncle Wu could not bear to part with her and got her back, but they argued regularly. Uncle Wu was greatly troubled, yet he could not find a way out. Eventually Hsi-shih died of misery. Uncle Wu was heartbroken. He painted many ink landscapes in her photo album, and asked Feng Ch’ao-jan (馮超然) to write a short biography. He asked me to compose two poems to be engraved at the back of her tombstone. She was buried at Hung-ch’iao Cemetery, next to his own tomb which he had already prepared. The album was deposited in my home. All these undertakings were completed by Chiang Han-t’ing (江寒汀). Uncle Wu wrote a horizontal scroll to thank Chiang Han-t’ing. As for the two poems I composed, Mao Kuang-sheng (冒廣生) lavished much acclamations. Unfortunately the manuscripts have been lost. I only remember one complete poem. Its title The Tombstone of Shih Wan-ch’iu Written for Ch’ien-an was penned by Mao Kuang-sheng. My poem reads:

Hard to sense in sorrow,

Waken is more like drunken.

When karma ends I know,

It is enmity yet care.

A foot of stele buries all,

Infinite depth of remorse.

All quiet is the setting sun,

To mourn a fragrant soul.

I have forgotten the first two sentences of the second poem. The last two sentences are:

Blossom and then wither,

A common sight for flowers.

Something to be gained,

Poet’s hair tainting white.

The photo album of Hsi-shih was also taken by the Red Guards who ransacked my home. It has never returned. It is impossible to know where it is now. The tombstone and the tomb were also broken up by the Red Guards. Uncle Wu inscribed these words on the title slip of the album: Traces from the Torrents of Time. It is indeed the Torrents of Time! How innumerable are the changes! In his final days, Uncle Wu could not speak. His children all drew the lines and abandoned him. His wife A-pao patted him on the shoulder, at the top of her voice she said: “You have no descendants whatsoever. No descendants have visited you. Do you know?” He nodded, and could not speak. After the Cultural Revolution, his son got some returned inheritance worth tens of thousands, and lived a retired life. He only appeared at the rehabilitation event to bow, and cannot be found afterwards.

Note: Uncle Wu was Wu Hu-fan. His first wife P’an Ching-shu (潘靜淑) passed away in 1939. Her maid A-pao became the official second wife in 1942. In which year did the girlfriend Shih Wan-ch’iu appear? It is not known. However, based on the death years of Feng Ch’ao-jan, Chiang Han-t'ing and Mao Kuang-sheng, she should have appeared between 1942 and 1954. The above paragraph is even clearer evidence that the insinuation of a romantic relationship between Chou Lien-hsia and Wu Hu-fan is implausible.

Feng Ch’ao-jan (1882-1954), original name Chiung (迥), tzu Ch’ao-jan, studio name Sung-shan Ts’ao-t’ang (嵩山草堂), native of Ch’ang-chou, Kiangsu Province. He was an eminent painter.

Chiang Han-t’ing (1904-1963), original name Ti (荻), hao Han-t’ing, native of Ch’ang-chou, Kiangsu Province. He was proficient in painting.

Mao Kuang-sheng (1873-1959), tzu Ho-t’ing (鶴亭), native of Ju-kao, Kiangsu Province. He excelled in poetry and tz’u lyrics.

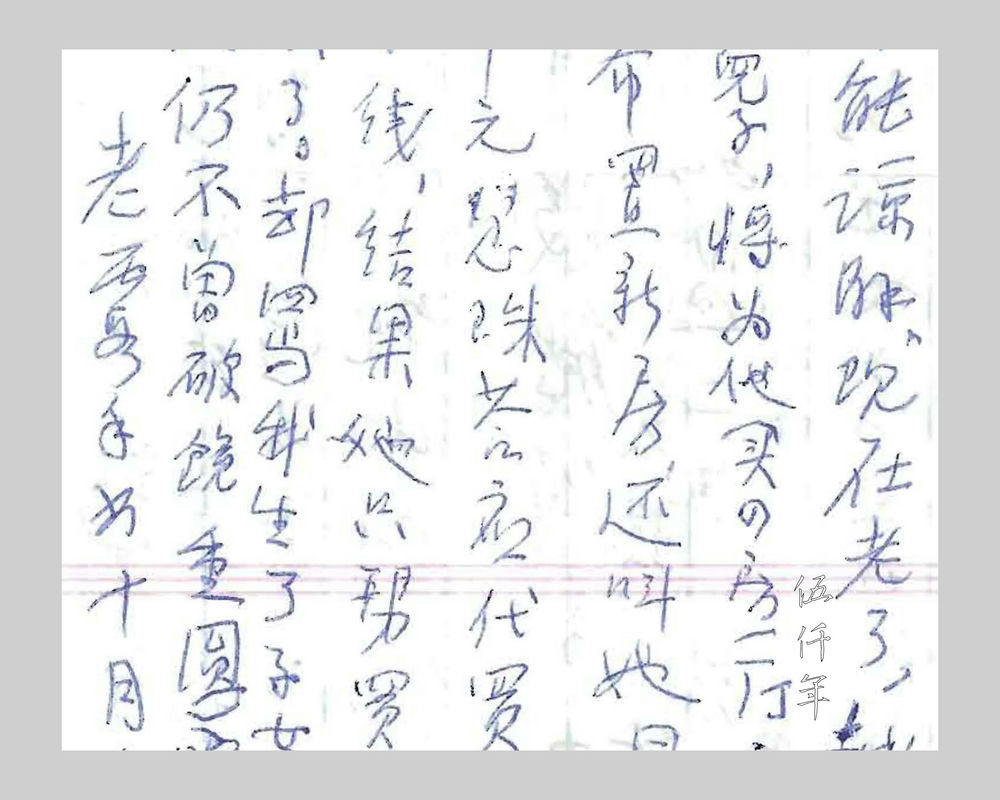

Fourth page of letter by Chou Lien-hsia to P’ing Ch’u-hsia

Uncle Wu requested me to paint A Portrait of Seven Concubines. I painted seven female figures and a male figure of a senior official. They are on a long bridge partying and watching the moon. The eight figures are very small, each half an inch tall only. At that time, my eyesight was still fine. The figures are very detailed. I also composed a tz’u lyric. Later on this piece was confiscated by a public museum. All the paintings on the title page are lost. (There was a line drawn painting of seven female figures by Feng Ch’ao-jan. There were also tz’u lyrics by others. They are all gone.) This too is the Torrents of Time!

For this reason I hope to publish my paintings in a book. It does not matter whether they are good, as longer as they are not lost. I can give the book to friends, relatives and students. Is it not a form of remembrance? But my fifth son (Wu-mao 五毛) objects, he thinks it is waste of money. He believes my savings should be allocated to him to buy a property, for property will rise in value. I can only find this laughable. I said even if I lived for another ten years or twenty years, I would not be able to afford to buy a property. Meanwhile Old Hsü has asked to divorce me, his girlfriend Yang Yüeh-mei (楊月美) wants to come to the United States. I agree to it. According to law, whoever asks for divorce, that person should pay the alimony.

Note: Old Hsü was Hsü Wan-p’ing (徐晚蘋), the husband of Chou Lien-hsia. When mainland China fell to the communists in 1949, Hsu Wan-p’ing left for Taiwan alone. Chou Lien-hsia and her five children stayed in the mainland. They were separated for decades. The marriage had already fallen apart before 1949, the relationship between the husband and wife never recovered even in old age. It is not the romantic story many recent writers made up.

Hsü said: “You are already over eighty years old. What is the need of alimony? You are not seriously thinking of living till one hundred? Furthermore, do you not have children to support you? Do you not have your American Son to give you money? (American Son implied social security payments from the American Government.)”

I told him I could waive the alimony, if he reimbursed me the money spent supporting a family of old and young, of eight or nine people over a period of thirty three years, the costs of education for the five children (two university graduates, two secondary school graduates and one primary school graduate), as well as the costs of weddings for the sons and daughters. Whenever he decided to reimburse this sum, it could be calculated in accordance with the living costs of that time. If we did not divorce, at least we were a family, I need not ask for this reimbursement. If we divorced, we were not a family, of course long debts should be returned. He said he had no money and could not pay out. I replied: “Then I will not divorce”.

He then said: “I will send you back to Shanghai. Every month I will give you one hundred U.S. Dollars. In addition to the retirement salary you get from your unit, you can still live. An example is the sister of my second wife, the second wife has a rich son, every month he sends the aunt one hundred U.S. Dollars. She has a decent life living in Su-chou.”

I said their relationship was between aunt and nephew, they were indirectly related, the nephew could agree to provide or not. We were husband and wife, it was the most direct of direct relationships, the nature was different, how could they be compared? He said when he was young, he married a second wife, I was able to understand then. Now in my old age, I became ever more stubborn. We ended up with a huge argument.

Later he proceeded to trick his eldest child (Ta-mao 大毛). He said that his rich step-son was going to buy a four room apartment for him. His eldest child and spouse, his third child and spouse could all live there. He asked her to persuade me to agree to a divorce. He also asked Hui-chu (慧珠) to help him buy furniture for the new apartment. He told her to meet Yang Yüeh-mei. She asked whether there would be reward in meeting Yang. He said that if she called her Aunt Yang, there would be a reward of five thousand dollars. So Hui-chu agreed to buy furniture for the new apartment. The fifth son asked for my opinion. I said that if the lot of you went to decorate the new apartment, I would have nothing to do with you all. At the end she only assisted in buying the furniture, and asked the shop to deliver them. She did not go to decorate the apartment. Finally, the rich step-son did not support his plan, so his scheme flopped. He scolded me that I had given births to children like expelling faeces, now I even occupied the toilet, so that he had no one to look after him at old age. That being the case, we still have not been able to "restore the full circle of a shattered mirror".

I have written so much, you must be worn out by reading it. Wishing your family health and happiness.

Old Hsia. 22 October.”

A talent of her generation, a survivor of political purges, alone and adrift at the end of the world. Perusing the works of poetry, tz’u, calligraphy and painting she left behind, still so faint a whiff of light fragrance.

Detail of letter by Chou Lien-hsia to P’ing Ch’u-hsia

Related Contents:

A Pair of Couplets by My Father Mr. Soong Hsün-leng (訓倫公) and Aunt Chou Lien-hsia (周鍊霞伯母)