Countless Chinese are fond of watching the Olympic Games. However few are aware that the Republic of China first participated in the Los Angeles Olympic Games in the 21st year of the Republic (1932), and it was in the 25th year of the Republic (1936) at the Berlin Olympic Games, when Chinese women first competed. At that time, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung (楊秀瓊) and Li Sen (李森) represented the Republic of China in the respective women’s categories of swimming and dash. One can conceive during the period of social reforms in the early years of the Republic, sports were very much popularized and the status of women was significantly elevated.

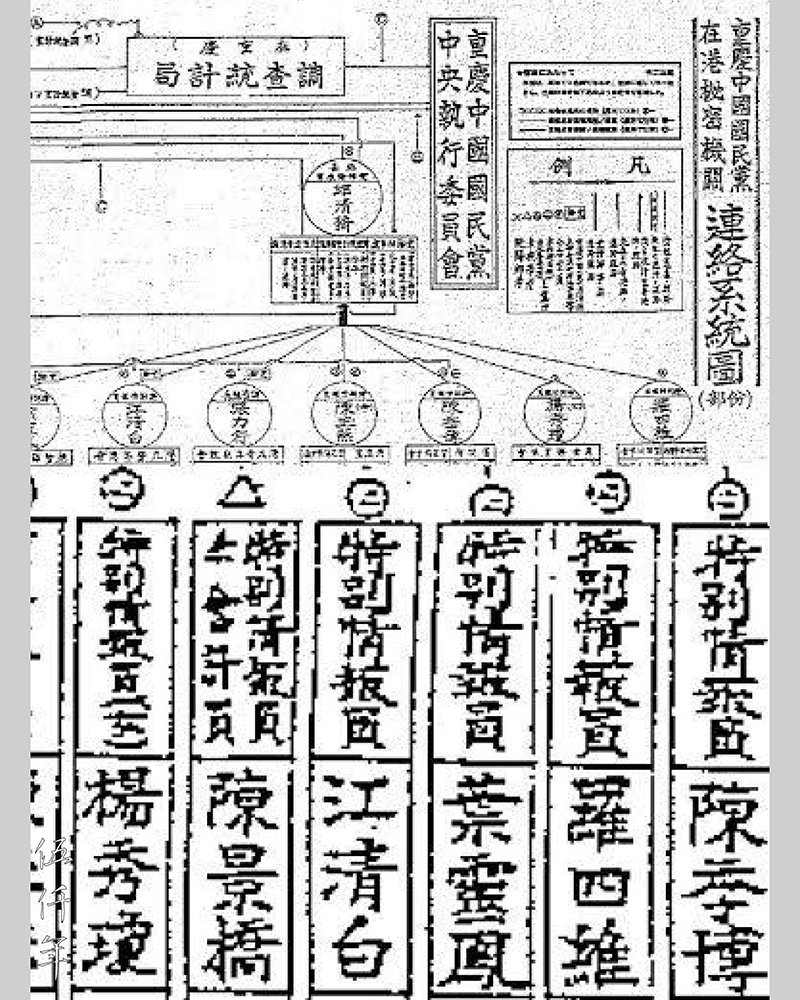

Yang Hsiu-ch’iung was not only a celebrated sportswoman and a pioneer of women’s rights, she was in particular a patriotic activist. In the 31st year of the Republic (1942), in the heat of the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung was appointed special agent at the Hong Kong Station of the Central Bureau of Investigation and Statistics (調查統計室香港站) affiliated with the Hong Kong and Macao Branch Headquarters of the Chinese Nationalist Party (中國國民黨港澳總支部), to spy on those politicians associated with the puppet government of Wang Ch’ing-Wei (汪精衛) in Hong Kong. In time of peace, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung dedicated her talent and ability to the country. In time of danger, she offered the prospect of life or death in her service. She was truly an exemplary example of civic virtues. The historian Ms. P’an Hu-lien is an authority on the life of Yang, she wrote the biography In Search of Mermaid Yang Hsiu-ch’iung (尋找美人魚楊秀瓊) to illuminate her neglected and forgotten life. Now Ms. P’an has summarized the book into a short and concise article to benefit our readership.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

Yang Hsiu-ch’iung promoting the New Life Movement in 1934 at the age of fifteen

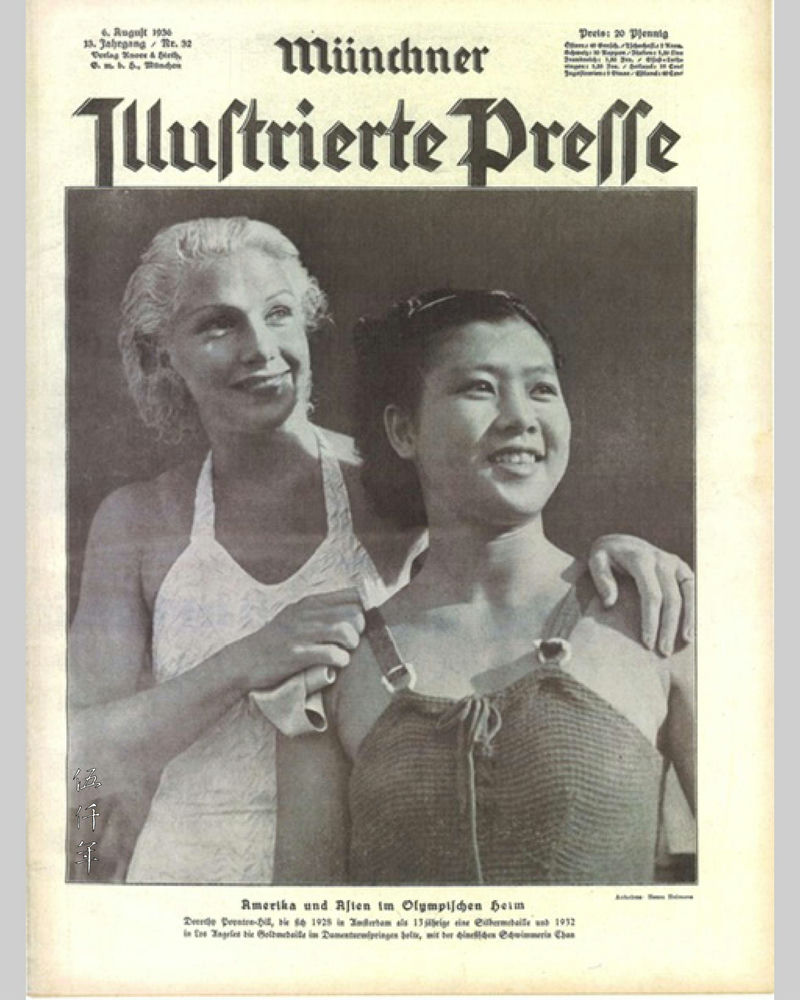

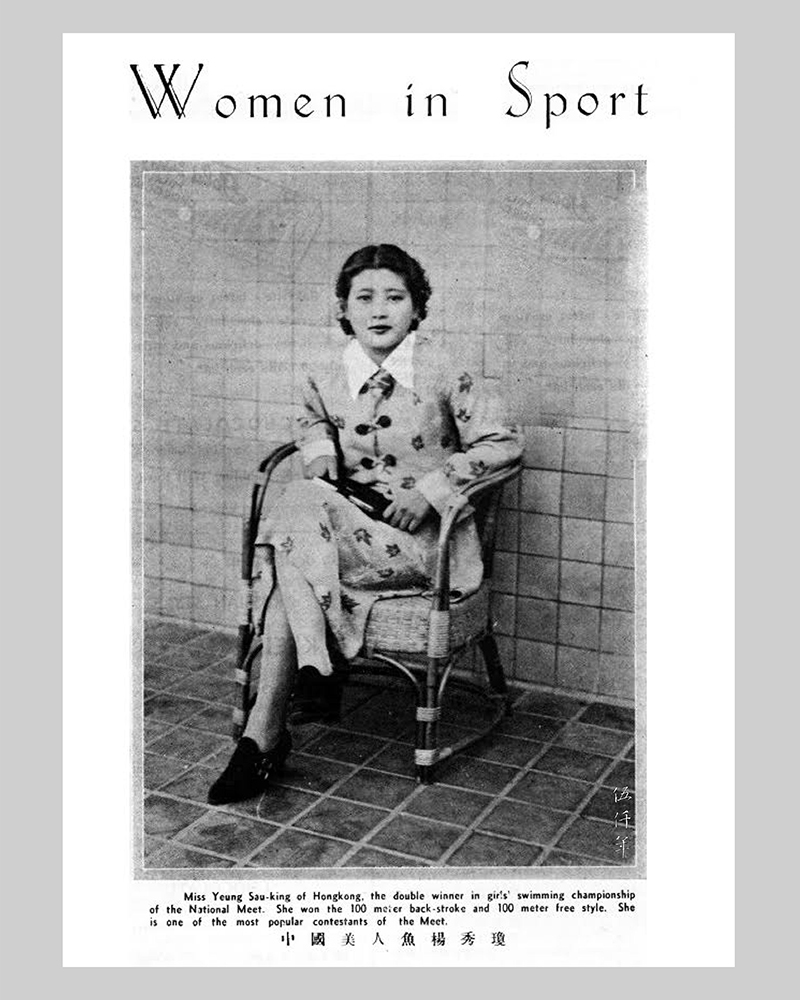

Harking back to the world eighty years ago, China for the first time delegated female athletes to compete in the Berlin Olympic Games of 1936. One of the athletes was the swimmer Yang Hsiu-ch’iung (also known as Yeung Sau King 楊秀瓊 1919-1982), also known as the “Mermaid”. She embodied the image of the new Chinese woman, vigorous, vivacious, fluent in English and sociable. She captivated the attention and good will of many people in the West. During the Olympic Games, the German magazine Münchner Illustrierte Presse and the French magazine Le Miroir du Monde both used her pictures on their front covers.

Yang Hsiu-ch’iung talking to a fellow swimmer

During the Berlin Olympics in 1936, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung was on the cover of the German magazine Münchner Illustrierte Presse

Although she was eliminated in the preliminary contests, her result in the 100 meter backstroke was a national record for China. In the 1930s and 1940s, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung was a swimming legend familiar to all Chinese. However, unknown to most people, during the Japanese invasion of China, she was a special intelligence agent of the National Government of the Republic of China in Ch’ung-ch’ing. She was stationed in Hong Kong and was responsible for collecting Japanese military intelligence. Her resistance story was only revealed eight years after her death when the Japanese national archives were declassified.

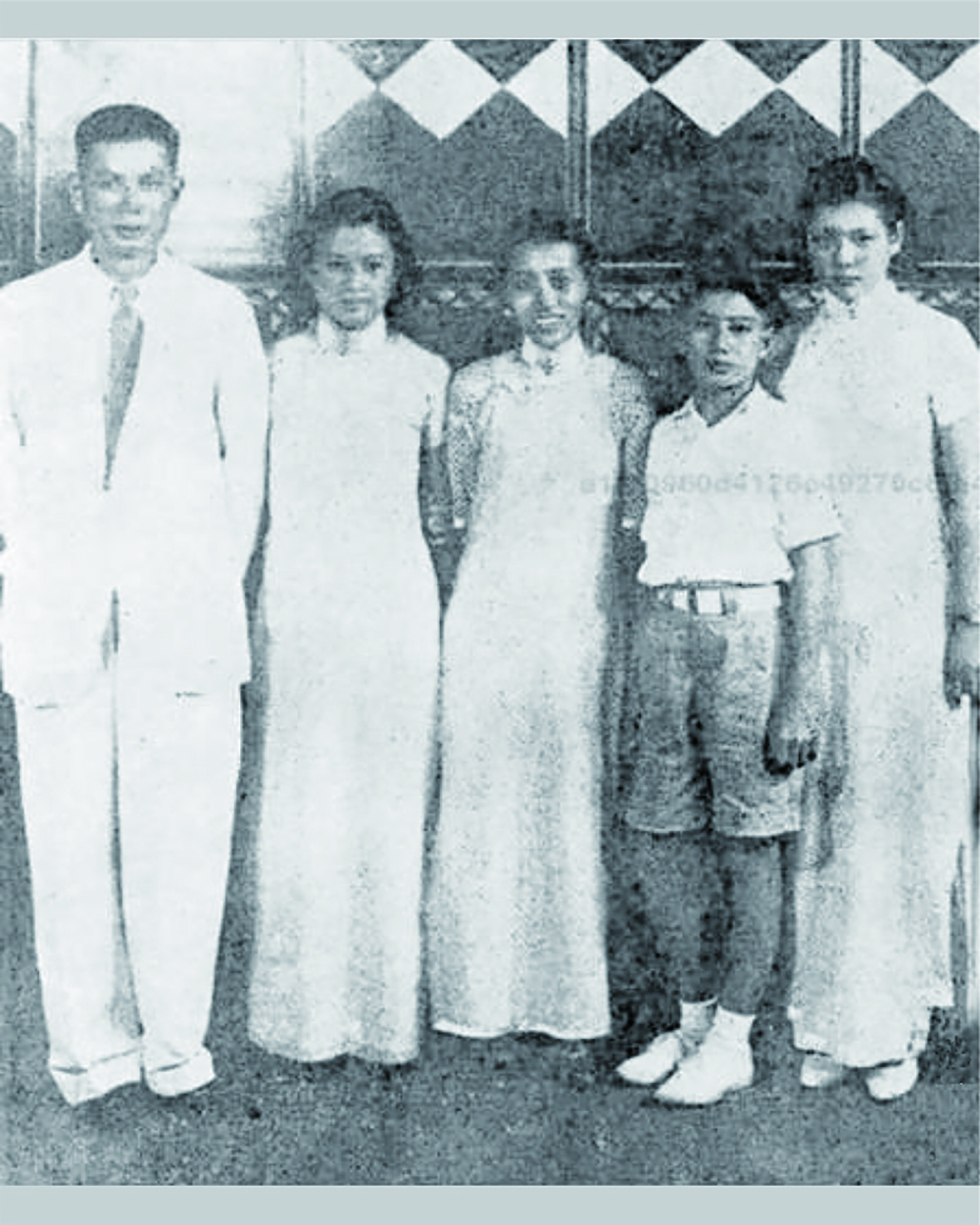

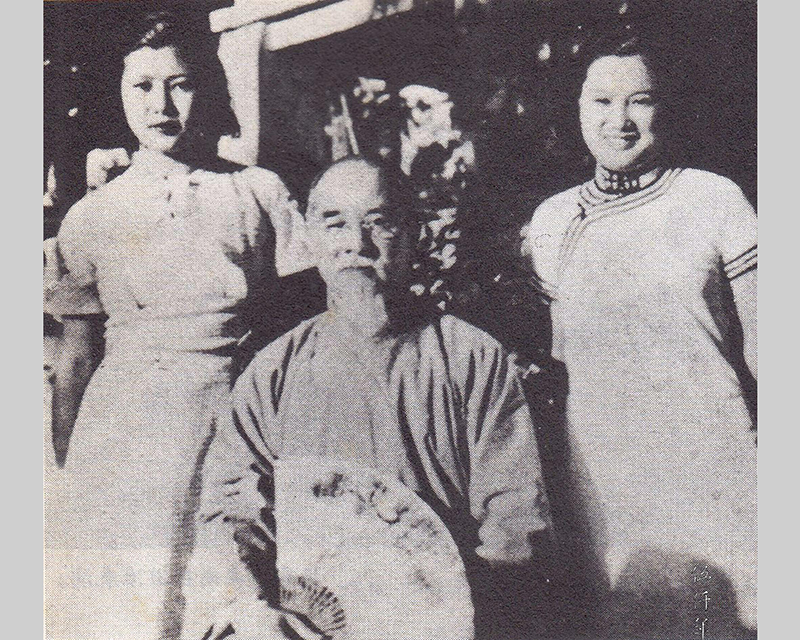

Yang Hsiu-ch’iung with her family in 1930s

Yang Hsiu-ch’iung was born in Hong Kong in 1919. Her father Yang Chu-nan (楊柱南) was a native of T’ung-kuan, Kwangtung Province. In his youth he moved to Hong Kong, where he started a family and worked as a manager in a foreign firm. Yang Chu-nan and his wife were avid swimmers, at one time he was director of the swimming department at the South China Athletic Association. Yang Hsiu-ch’iung was influenced by his father, she was attached to the water at a young age, and received her formative training in the swimming pool of the South China Athletic Association.

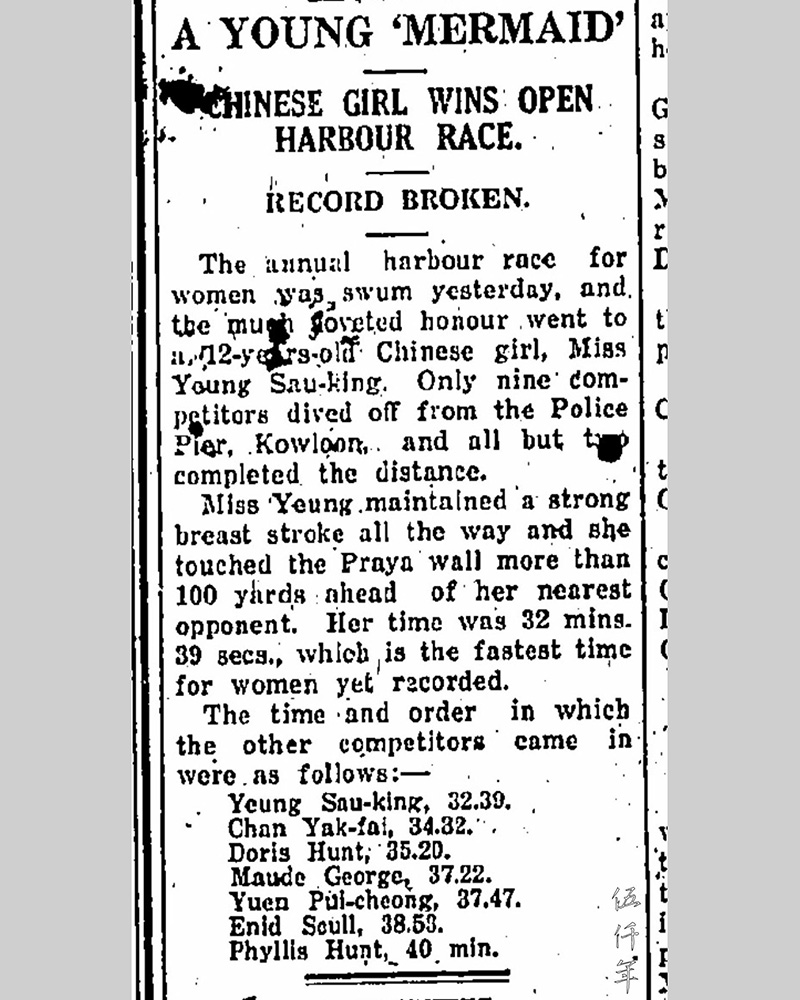

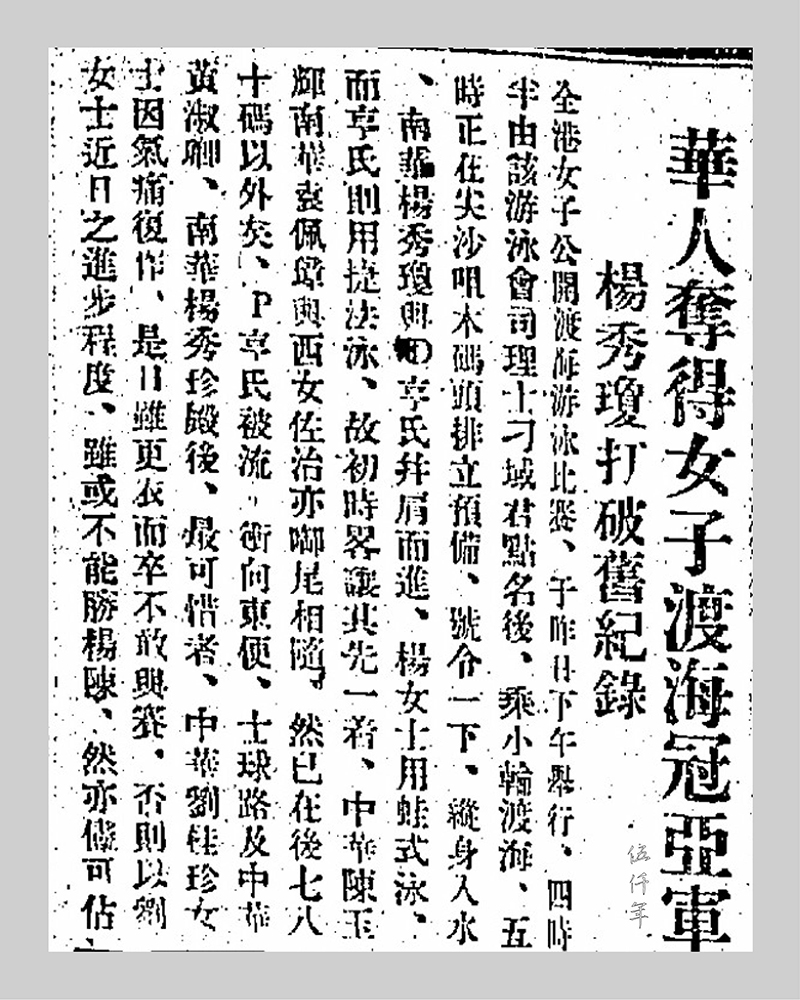

In September 1930, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung participated in the Third Swimming Gala of Kwangtung Province held in Canton. Even though she was not yet twelve, she won first prizes in three categories and broke new records. The results were remarkable. On 10th October in the same year, she participated in the Hong Kong Chinese Open Swimming Competition. She won two first prizes, two first runner-up prizes, and the women’s group championship. On 14th October, she participated in the Hong Kong Chinese and Caucasian Cross Harbour Swimming Competition for the first time and won the championship. She also broke the women’s cross harbour swimming record since 1920. In all three competitions during this year, she achieved prideworthy results and gained wide public acclaim.

China Mail, a Hong Kong newspaper, reported on the Hong Kong Cross Harbour Swimming Competition on 14th October 1930 which Yang Hsiu-ch’iung won

The Kung Sheung Daily News, a Hong Kong newspaper, reported on the Hong Kong Cross Harbour Swimming Competition on 14th October 1930 which Yang Hsiu-ch’iung won

In October 1933, the Nationalist Government organized the Fifth Chinese National Games in Nanking. For the first time, women’s swimming categories were included. Yang Hsiu-ch’iung represented Hong Kong and she won a total of five first prizes. They were for the individual races of 50 metre free style, 100 metre free style, 100 metre backstroke, 200 metre butterfly, and lastly the 200 metre relay with a group of four competitors. At that time, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung was young, elegant and ravishing. She was the new sports star for the whole country, and newspapers in Shanghai dubbed her the “Mermaid”.

Group portrait of Hong Kong swimmers at the Fifth Chinese National Games in the 22nd year of the Republic (1933). From left: Yang Hsiu-chen (楊秀珍), Yang Hsiu-ch’iung, Liu Kuei-chen (劉桂珍) and Liang Yung-hsien (梁詠嫻)

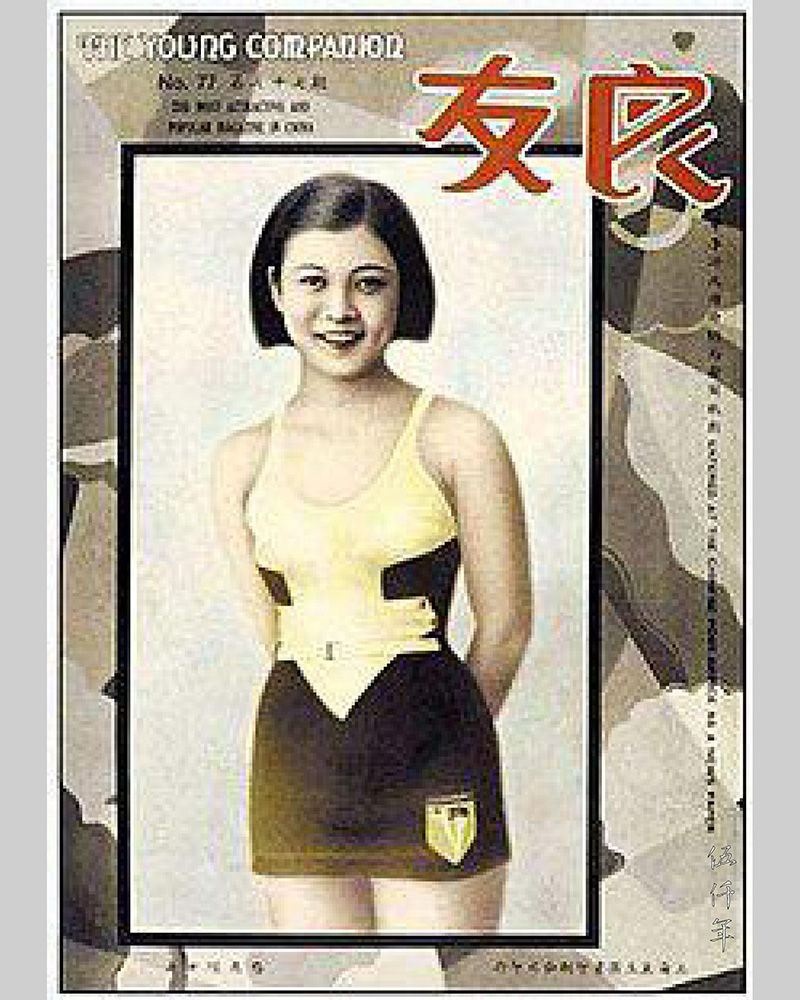

Yang Hsiu-ch’iung on the cover of The Young Companion, 1933

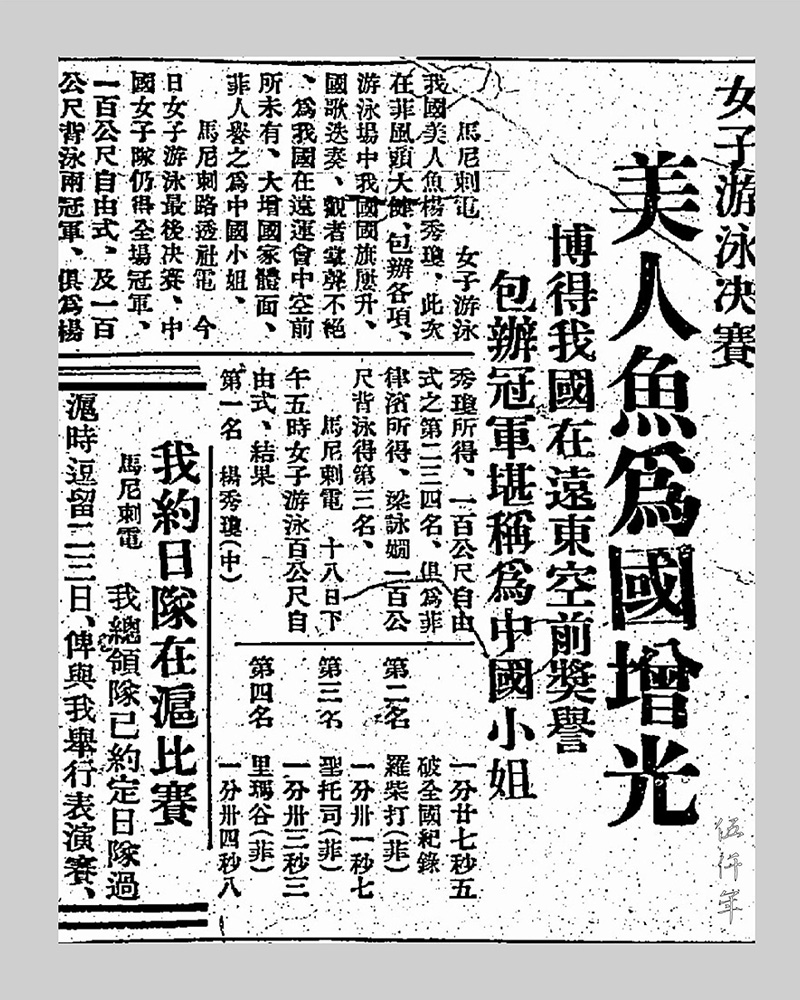

In May 1934, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung proceeded to engage international competitions. She represented the Republic of China at the Tenth Far Eastern Championship Games in Manila, the Philippine Commonwealth. For the women’s swimming categories, it was a fight between the Republic of China and the Philippine Commonwealth, Japan did not participate with her stronger women’s team. Yang Hsiu-ch’iung won four gold medals, and became the overall champion of the women’s categories. During the 200 metre relay, the Chinese team was lagging behind in the first three legs, but Yang caught up in the final leg and won. She was therefore particularly lauded, many regarded her as a national heroine.

The 19th May 1934 copy of The Kung Sheung Daily News, a Hong Kong newspaper, reported on the Tenth Far Eastern Championship Games in Manila in which Yang Hsiu-ch’iung won four gold and the title of overall champion for women’s categories

Trophy of overall champion for women’s categories at the Tenth Far Eastern Championship Games in Manila

Detail of trophy of overall champion for women’s categories at the Tenth Far Eastern Championship Games in Manila

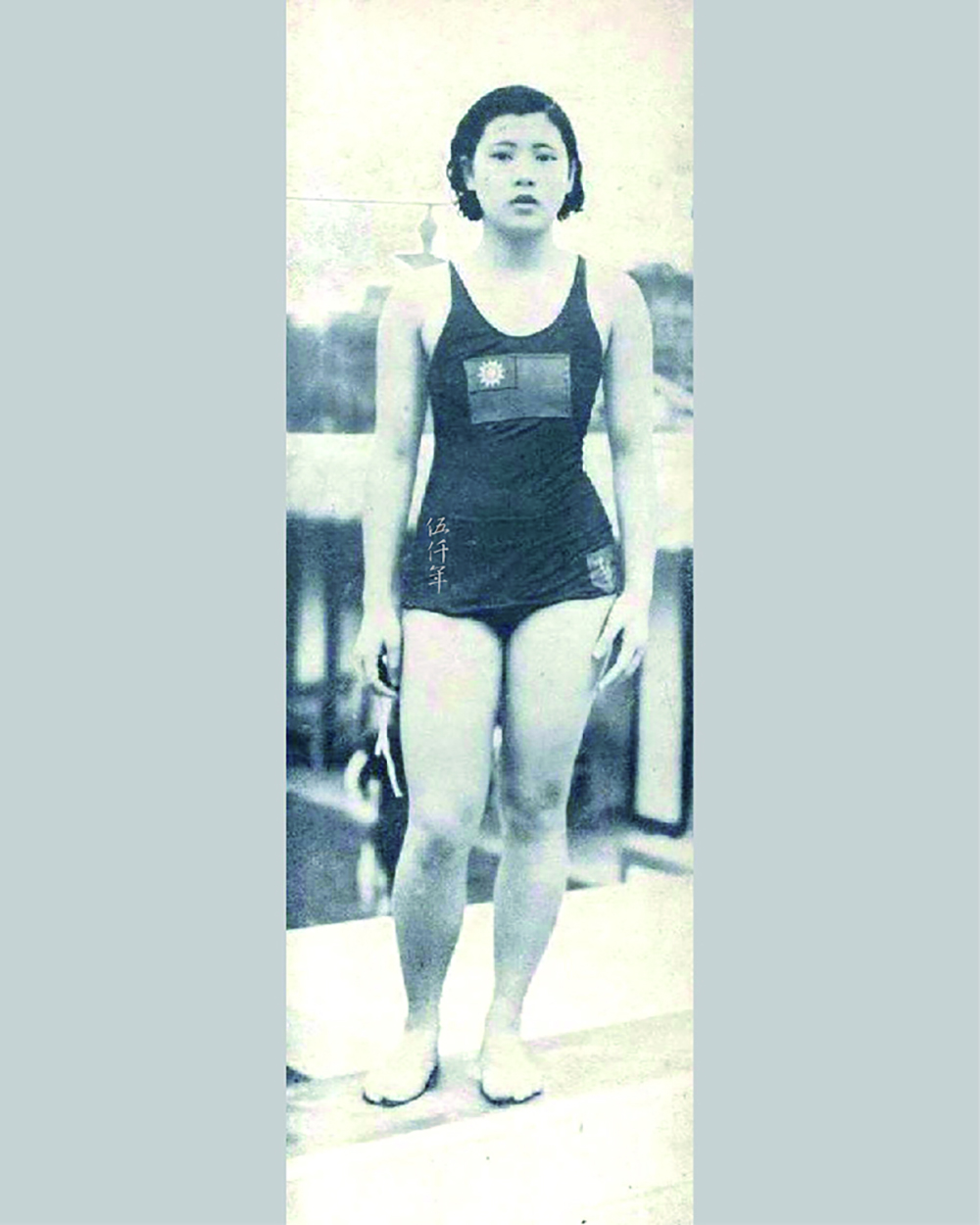

Yang Hsiu-ch’iung in swimwear showing the National Flag of the Republic of China

The sisters Yang Hsiu-chen, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung with Lin Sen (林森), chairman of the National Government of the Republic of China, on the cover of the 1934 issue of Lin-lung Magazine

At the time the Nationalist Government was promoting the New Life Movement (新生活運動) nationwide, advocating personal discipline and virtues, public order and hygiene. In July 1934, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung was invited as guest of honour to the opening of the swimming pool at the New Life Club in Nan-ch’ang, Kiangsi Province, and to demonstrate her swimming virtuosity. The Nationalist Government hoped that her reputation and vigorous image could help the promotion of a new lifestyle. On this trip, she also visited Lu-shan, Nanking, Shanghai and other places, attending numerous charity events and swimming demonstrations. She was received and decorated by Lin Sen (林森 1868-1943), Chairman of the Nationalist Government. An official photograph was taken for the occasion.

Feature Article Women in Sport on Yang Hsiu-ch’iung in Ching-le Pictorial Magazine, published in Shanghai 1935

Within a few years, she became a celebrity. Her fashionable wardrobe, personal affinities, romantic liaisons, all became stories for leisure magazines and tabloids. Yet her fame also attracted numerous unfair allegations. Here is an example. In October 1935, at the Sixth Chinese National Games in Shanghai, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung continued to represent Hong Kong in three individual races. She broke existing records in two of the races, but for the 50 metre free style, she lost to her nemesis Liu Kuei-chen (劉桂珍) by less than a second, and received the first runner-up prize. Though it is common to win and lose in sports competition, some newspapers and magazines criticized her partying and epicurean lifestyle as the reason for regression, others commented that she was overrated.

Yang Hsiu-ch’iung was not intimated by rumours nor malice. She continued her arduous training towards the goal of taking part in the Olympic Games. At last, in the team selection trials, she not only broke one Chinese record, but both Chinese records of the 100 metre free style and the 400 metre free style. She was successfully nominated.

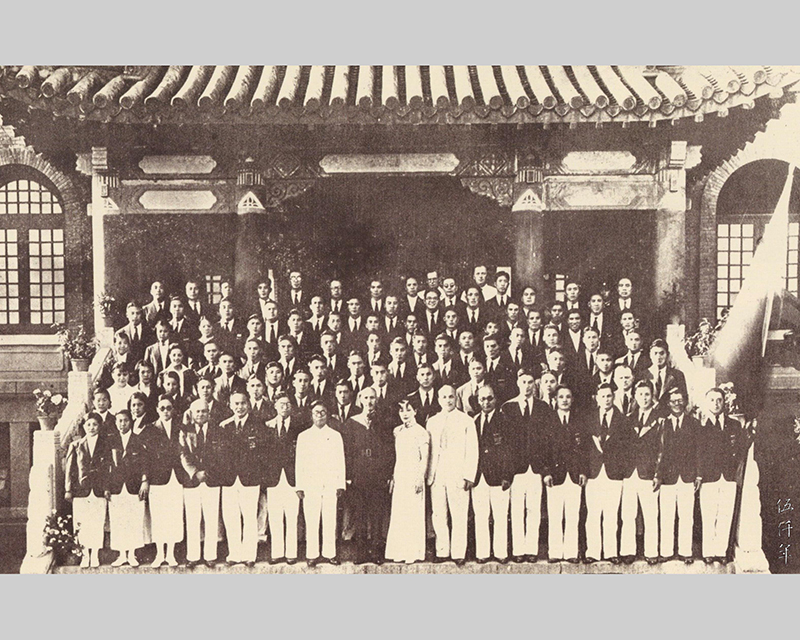

The 139 member Chinese Team arriving in Berlin for the 1936 Olympics

In August 1936, the 11th Olympic Games took place in Berlin. The Nationalist Government sent a delegation of over one hundred and forty delegates, including fifty five athletes, two of whom were women. One was Li Sen (李森 1914-1942) who was to take part in the 100 metre dash, the other was Yang Hsiu-ch’iung who was to take part in the 100 metre free style and the 100 metre backstroke. They were both eliminated in the preliminary contests. Due to erroneous reportings by the journalists from the Central News Agency in Berlin, Chinese media had long been unaware that in the 100 metre backstroke, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung broke her own record set in the Sixth Chinese National Games of 1935 by one second.

Yang Hsiu-ch’iung accepting a bouquet on behalf of the Chinese Team from well wishers in Berlin in 1936

At that time, the overall standard of sports in China was far behind developed countries. The most important objective of participating in the Olympic Games was to gain experience, and to map a road for the development of Chinese sports in the future.

The Chinese team was eliminated in the preliminary contests, except pole vault, represented by Fu Pao-lu (符保盧 1914-1943) who made it through to the intermediary contest. Those Chinese at the time who were only obsessed with “winning medals”, and those dissatisfied with the Nationalist Government of Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石 1887-1975), used the results of the Berlin Olympic Games as an opportunity to attack the government for participation, asserting that financial resources were squandered without winning any medals in return. Even though Yang Hsiu-ch’iung had been celebrated in the past, naturally she now became a figure for ridicule.

Group portrait of President Chiang Kai-shek of the Executive Yuan, Madam Chiang Kai-shek and the Berlin Olympics Chinese Team, taken before departure to Germany

In that era, a slightly weaker woman, when faced with an avalanche of criticisms, would perhaps follow the same path as the actress Juan Ling-yü (阮玲玉 1910-1935) by committing suicide. If not, she might still be devastated. But for Yang Hsiu-ch’iung, an exuberant character with the unyielding strength of an athlete, returned to Hong Kong and published an autobiography. Regarding the Olympic Games, she admitted on one hand she had her weaknesses and inadequacies, but argued on the other hand, to participate in the Games was a positive and meaningful act. She also wrote articles for newspapers about her experiences in Europe and the Berlin Olympic Games to share with the public.

In July 1937, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung entered swimming competitions once more, this time at the South China Athletic Association in Hong Kong. She broke the national record with her result of 33 seconds for the 50 metre free style. After the outbreak of the War of Resistance Against Japan, the Nationalist Government had to fight against Japanese invasion with all her resources, the Chinese National Games in October was cancelled. Yang Hsiu-ch’iung lost the opportunity to challenge herself again at the Games. On 5th November 1939, she started a new chapter in her life by marrying the renowned jockey T’ao Po-lin (陶柏林) in Hong Kong. She later bore a son and a daughter.

However, two years into the marriage, there was rumour of their separation. Yang Hsiu-ch’iung later pointed out that her husband had a furious temper, there was continual domestic violence, until they were both estranged. Not longer after, the Pacific War broke out, Hong Kong fell on Christmas Day in 1941. T’ao Po-lin moved to mainland China for business, and Yang Hsiu-ch’iung stayed in Hong Kong to look after the children. From September 1942 onwards, she became an undercover intelligence agent in the War of Resistance Against Japan.

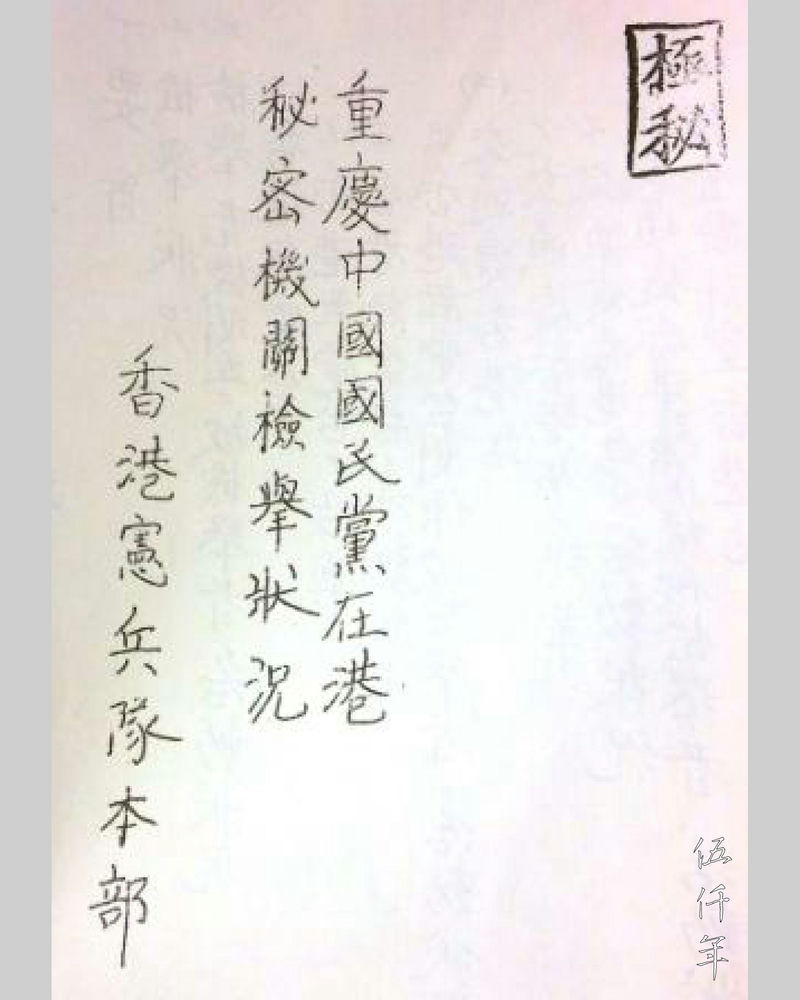

A file labelled Top Secret in the declassified Japanese national archives revealed that Yang Hsiu-ch’iung was a special intelligence agent of the Chinese Kuomintang

From the declassified Japanese national archives, there is a document with the title: Status of Informing on the Ch’ung-ch’ing Chinese Nationalist Party Secret Station in Hong Kong (重慶中國國民黨在港秘密機關檢舉狀況). Its cover has a “Top Secret” stamp (1). This report was compiled and written by the Japanese Military Police stationed in occupied Hong Kong. It documented the methods used to collect Japanese military intelligence in Hong Kong by thirty eight intelligence agents from the Ch’ung-ch’ing Chinese Nationalist Party Secret Station. Among the thirty eight intelligence agents was Yang Hsiu-ch’iung, thence her little known espionage assignments were thus revealed.

A file labelled Top Secret in the declassified Japanese national archives revealed that Yang Hsiu-ch’iung was a special intelligence agent of the Chinese Kuomintang

According to this document, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung was a special intelligence agent at the Hong Kong Station of the Central Bureau of Investigation and Statistics (調查統計室香港站) affiliated with the Hong Kong and Macao Branch Headquarters of the Chinese Nationalist Party (中國國民黨港澳總支部). Her code name was I-mei (易梅), she was recommended by Lo Ssu-Wei (羅四維), another special intelligence agent, to join the Bureau a year after the occupation of Hong Kong. Yang Hsiu-ch’iung was mainly responsible for collecting intelligence related to politicians from the puppet government of Wang Ching-wei (汪精衛) and Japanese sympathizers in Hong Kong. There is an attached document with the title: Register of Reported Agents (被檢舉者名簿), which chronicled detail information about the thirty eight captured intelligence agents. There are two pages on Yang Hsiu-ch’iung, including her resume and date of arrest on 1st May 1943.

At that time, the Japanese military raided the secret station and ferreted out the register of agents. Yang Hsiu-ch’iung and dozens of other agents were then arrested, there is no record of the lengths of their interrogations. One may conjecture that Yang Hsiu-ch’iung, being active in the social scene and a prominent sports personality, would impel rescue efforts, and released after a few months of interrogations.

Searching through old newspapers and magazines from Shanghai, there is an interview with Yang Hsiu-ch’iung published in the 15th October 1943 issue of Spring and Autumn Magazine (春秋月刊). She recounted after leaving Hong Kong, she lived in Canton for over a month, then moved to Shanghai in September, and was about to work for a local sports association. Her two children, a boy and a girl, did not accompany her. They were being looked after by her mother. In the following two years, other mainland magazines also covered her news in Shanghai. It is clear after her arrest and release by the Japanese, she left Hong Kong to live in Shanghai. The reasons and details are yet to be uncovered.

The daughter of Yang Hsiu-ch’iung, Ch’en Ai-chu (陳愛珠), recounted in our interview that the mother during her lifetime, did not ever mention her espionage work for the Chinese Nationalist Party during the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong. It was rather her uncle, the younger brother of Yang Hsiu-ch’iung, Yang Ch’ang-hua (楊昌華) who told her about it. Unfortunately Yang Ch’ang-hua passed away in 2011, it is no longer possible to learn more.

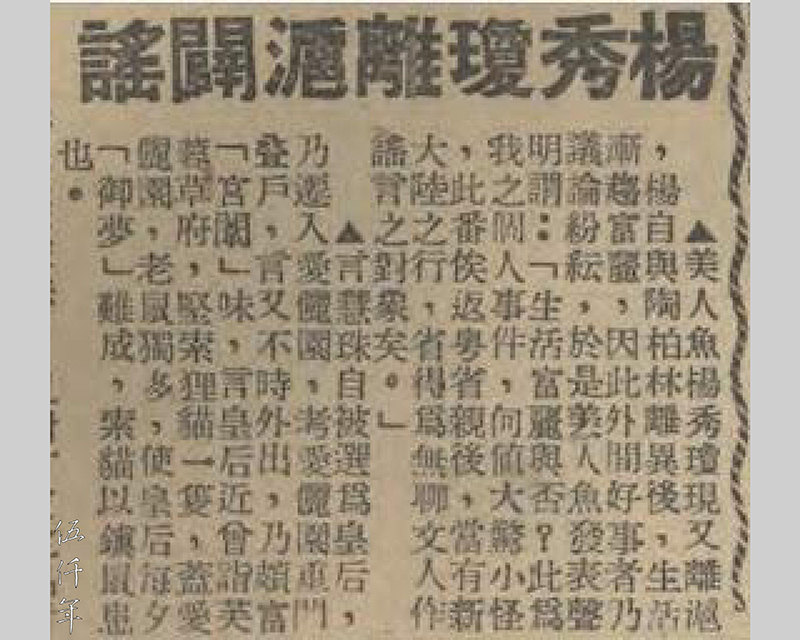

Shanghai newspaper reported on the private life of Yang Hsiu-ch’iung

After China’s victory over Japan in 1945, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung became a journalist at Ch’iao-sheng Pao Nespaper (僑聲報) in Shanghai. She was again active in social circles, and contemplating to divorce. Gossips about her marital status and romantic liaisons were hot topics for the tabloids. One of the gossips was the pursuit of marriage by the warlord Fan Shao-tseng (范紹增) from Szechwan Province who was in Shanghai on business. Yang Hsiu-ch’iung publicly repudiated this. She left Shanghai, the hotbed of controversies, for Kwangtung temporarily to visit her relatives.

At the end of 1947, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung and T’ao Po-lin were officially divorced, she was awarded the legal custodies of the children. In October the following year, she married Ch’en Chen-kuang (also known as Tan Tjin Koan 陳真廣), an Indonesian businessman of Chinese descent in Shanghai. The political situation was perilous in China, they moved to Bangkok, there she bore two daughters.

Ch’en Chen-kuang was a native of Fukien Province who grew up in Indonesia and was educated in the Netherlands. After the Second World War, he travelled for business between Shanghai and Bangkok. It was in Shanghai where he first met Yang Hsiu-ch’iung. In 1953, the whole family relocated from Bangkok to Hong Kong. Ch’en Chen-kuang established a company dealing in household electric appliances from known brands, as well as investing in properties. Apart from helping the husband in the management of his businesses, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung participated in charity works for the impoverished which were run by the Catholic Church.

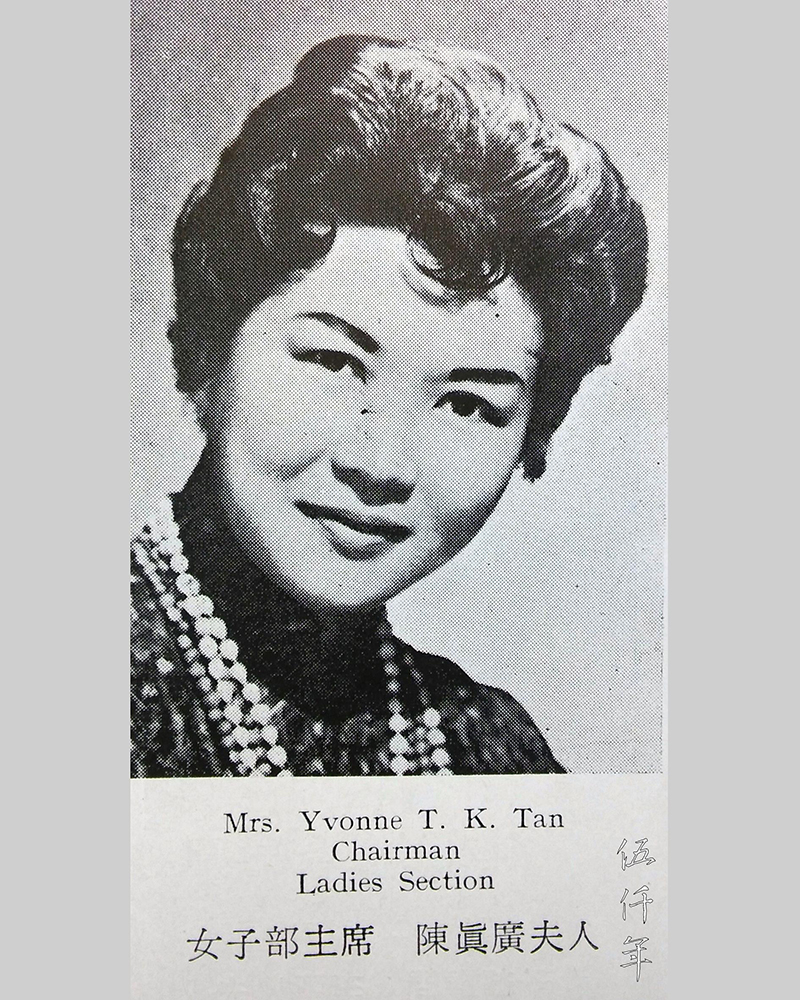

In the 51st year of the Republic (1962), Yang Hsiu-ch’iung was elected chairwoman of the women’s section of the Hong Kong Life Saving Society

In 1962, the women’s section of Hong Kong Life Saving Society was established, and Yang Hsiu-ch’iung was elected the first president. In her four years tenure, she actively expanded training classes for women lifeguards, and promoted women’s participation in life saving work. In July 1966, the second Royal Life Saving Society-Commonwealth Conference was held in London, Hong Kong Life Saving Society was represented by five delegates, and Yang Hsiu-ch’iung was the only female delegate. Two years later, she was awarded a medal from the Royal Life Saving Society-Commonwealth, accompanied by a signed certificate from Earl Mountbatten, to acknowledge her services to life saving.

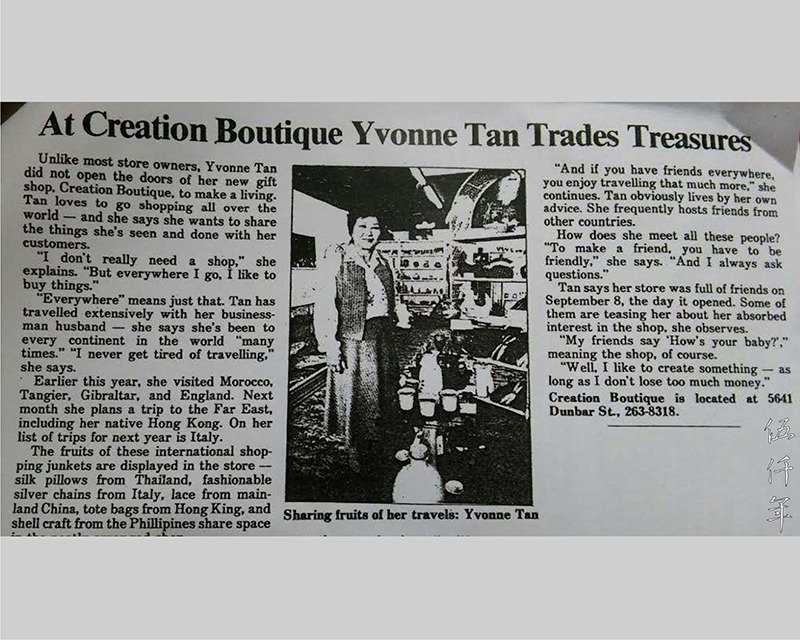

Canadian newspaper reported on the gift shop of Yang Hsiu-ch’iung

In 1970, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung with her family immigrated to Vancouver in Canada. She ran a boutique there for some time. She was much involved with charity works related to the Chinese in Vancouver, sponsoring a number of local Chinese societies, and co-founded the Chinese Culture Centre.

On 10th October 1982, it was suspected that Yang Hsiu-ch’ung climbed a ladder to retrieve some items on a high shelf and fell by accident. No one was in the house to save her, and tragically she died of this accident. She was at the age of sixty three.

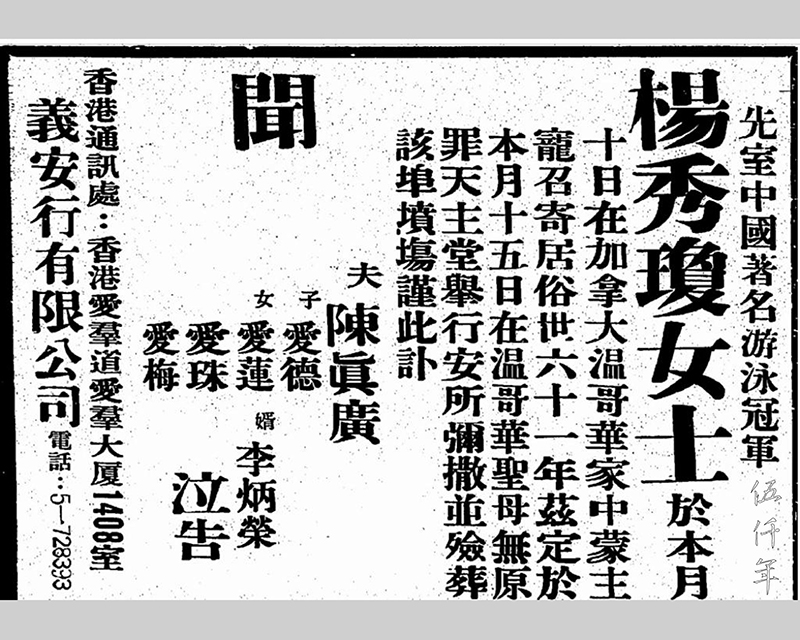

The obituary of Yang Hsiu-ch’iung in Hong Kong newspaper. She passed away at the age of sixty three

Many articles on the internet about Yang Hsiu-ch’iung only skimp the surface, or try to be sensational to win attention. Here is an example of a slanderous tale: During the Sino-Japanese War when the government of Chiang Kai-shek was in the provisional capital Chungking, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung went there to participate in the national swimming competition. The warlord Fan Shao-tseng from Szechwan Province saw her and drooled over her beauty, he secured permission from Chiang Kai-shek, forced Yang to divorce her husband and she became mistress number eighteen.

Checking the authoritative works on sports history published in mainland China and Taiwan, as well as those published in wartime Chungking (2), it is clear after the Nationalist Government moved to Chungking in November 1937, the government did not organize any national swimming competition in light of the catastrophic Japanese invasion. On top, Yang Hsiu-ch’iung had not even been to Chungking. The gossip linking Fan Shao-tseng started near the end of 1946 when she was contemplating divorce, and not during the War of Resistance Against Japan. As mentioned earlier, Yang scuttled such gossip by public repudiation. Afterwards she remarried in Shanghai, lived in Bangkok, Hong Kong and Canada successively. These are all verifiable through newspapers, magazines and evidences from relatives. In recent years, descendants of Fan Shao-tseng in mainland China, in numerous newspaper interviews, also denied the rumour about the amorous relationship between Fan Shao-tseng and Yang Hsiu-ch’iung (3). The reasons for this slander may have originated from the political struggle between the Nationalist and the communists, discrimination against women, restrictive mainland society with limited information, and the absence of dedicated research from many writers.

The life of Yang Hsiu-ch’iung, directly and indirectly, has been a positive force in inspiring Chinese to unite and strive, to seek equality between men and women, to promote swimming and to develop life saving. It is welcoming news to learn that the Hong Kong Museum of History has been in contact with the descendants of Yang Hsiu-ch’iung, with the hope of bringing back some of her trophies to Hong Kong, to display them at the Museum after the renovation reopening in 2022, so that the sports contributions made by the people of Hong Kong to the Republic of China can be more broadly known. If this does occur, then these historical artefacts can be examined in close proximity, to recall the life and deeds of a great swimmer of that era.

1. Status of Informing on the Ch’ung-ch’ing Chinese Nationalist Party Secret Station in Hong Kong (重慶中國國民黨在港秘密機關檢舉狀況), published by Fujishuppan Co., Ltd., Japan, in 1988.

2:

2.1 History of the Development of Chinese Sports (中國體育發展史) by Wu Wen-chung (吳文忠), published by San Min Book Co., Ltd., Taipei, in 1981.

2.2 Volume Four of the General History of Chinese Sports (中國體育通史) by Ts’ui Le-ch’üan (崔樂泉) and Ma Ai-min (馬愛民), published by People’s Sports Publishing House, Peking, in 2008.

2.3 History of Sports in Ch’ung-ch’ing (重慶體育志), by the Sports Committee of Chongqing City (重慶市體育運動委員會), published by Chongqing Publishing House in 1996.

2.4 Historical Sports Material of the Provisional Capital during the War of Resistance Against Japan (抗戰時期陪都體育史料) by the Sports Committee of Chongqing City, published by Chongqing Publishing House in 1989.

3. Searching for Mermaid Yang Hsiu-ch’iung, the Untold Story of a Swimming Legend from Hong Kong (尋找美人魚楊秀瓊 - 香港一代女泳將抗日柲辛) by P’an Hui-lien, published in Hong Kong in 2019.

Portrait of Ms. Yang Hsiu-ch’iung in 1948