Wu Jang-chih (吳讓之 1799-1870), the distinguished seal engraver of late Ch'ing dynasty, carved nearly ten thousand seals in his lifetime. However, most of them have now been lost. Although seal engraving is regarded as a primary from of art, it has not been easy to preserve the seals. Calligraphy and painting can be used for wall decorations, seal has the surface of a square inch, it can only provide a space for the mind to wander. The vulgar and insensitive are certainly not interested in seal engraving, and out of this bustling world, how many can be counted as aficionado? Furthermore, most of the seals carved by Wu Jang-chih are not signed. We can imagine his pride and satisfaction in his own seal achievement, assuming whenever a connoisseur encountered his seal, he would cup his hands in respect and fall over the floor, why should it be necessary to have a signature? Alas, most things are contrary to wishes. How could Wu Jang-chih know that over a hundred years later, classical culture has been eradicated and in ruins? Or that only one out of a hundred of his own seals has managed to survive? The contemporary seal engraver, Mr. Ku Yao-hua, is a soulmate of Wu Jang-chih from another era. A few years ago, he came across an unsigned seal, he felt certain it was the handiwork of Wu Jang-chih. Later on, it was agreed upon by other seal collectors as well. In an instant, this seal became an important artwork. It is a pleasing event in the world of seals. Mr. Ku wrote this article to recount the story from the beginning to the end. It is also a likely consolation for Wu Jang-chih in the otherworld.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

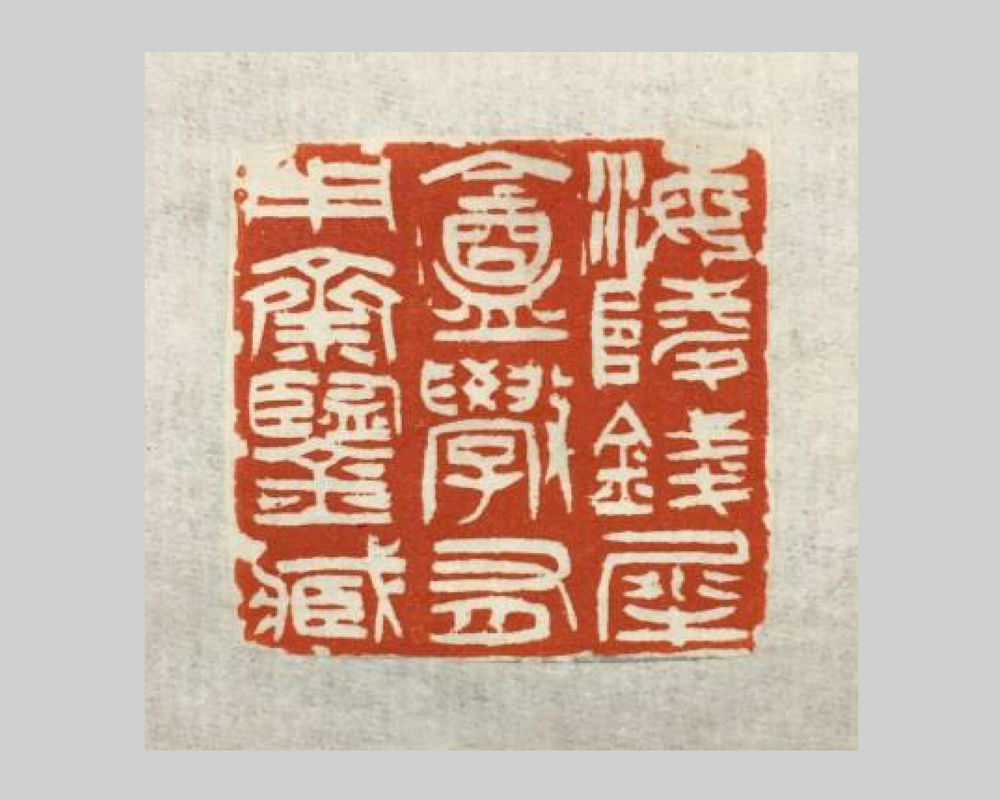

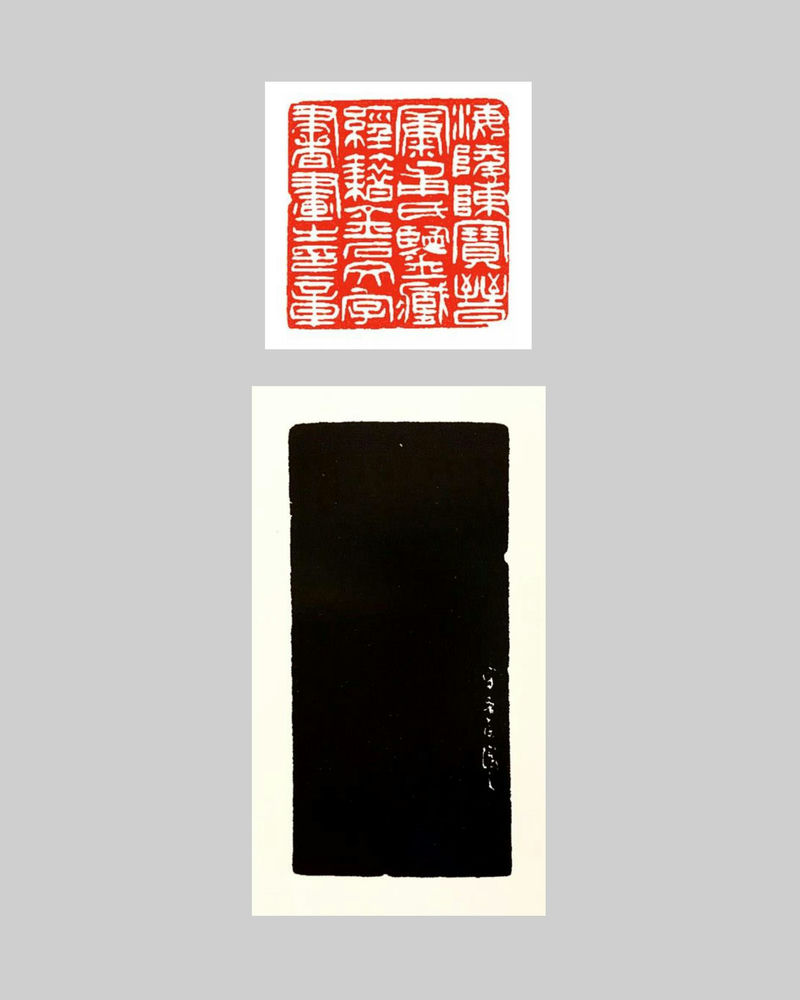

Seal engraved by Wu Jang-chih with these characters: “Inspected and collected by Ch’ien Hsi-an in the Studio of Hsüeh-yu-yung from Hai-ling.”

Wu Jang-chih (吳讓之 1799-1870) was certainly a seal engraver not to be overlooked in the art history of seal engraving in the Ch’ing dynasty. He was influenced by the seal engraving style of Wan district (皖 Anhwei province), which was founded by Teng Shih-ju (鄧石如 1743-1805), and carried on by Pao Shih-ch’en (包世臣 1775-1855). The Wan school of seal engraving also inspired Chao Chih-ch’ien (趙之謙 1829-1884), who synthesized the Wan school and the engraving style of the Che school (of Chekiang province) into his own distinct style. The Wan school conception of integrating different calligraphy scripts and brush works into seal engraving, have greatly influenced many later seal engravers as well.

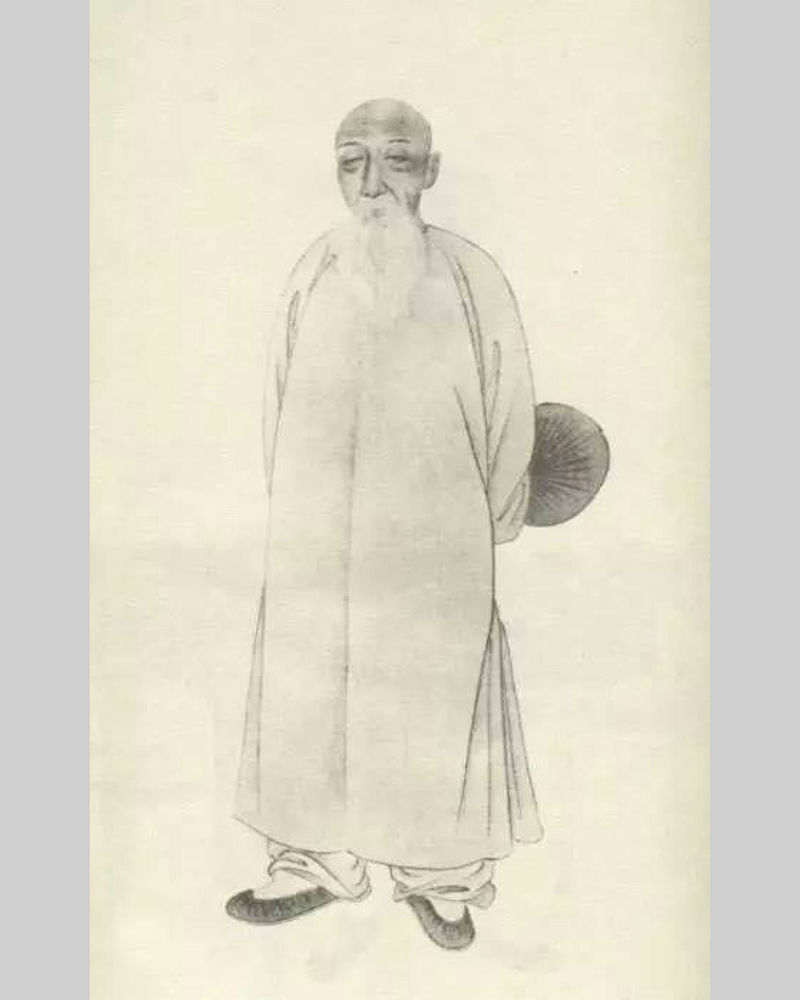

Wu Jang-chih, original name T’ing-yang (廷颺), tzu Jang-chih (讓之), Hsi-tsai (熙載), Jang-weng (讓翁), Wan-hsüeh Chü-shih (晚學居士), Fang-chu Chang-jen (方竹丈人). He mostly preferred using his tzu names (pseudonyms) and was a native of I-cheng (Yang-chou), Kiangsu province. He studied under Pao Shih-ch’en, student of the founder of Wan school Teng Shih-ju. Wu Jang-chih excelled in calligraphy and painting, and was particularly acclaimed in seal engraving. (Illustration 1 and 2).

Illustration 1: Portrait of Wu Jang-chih

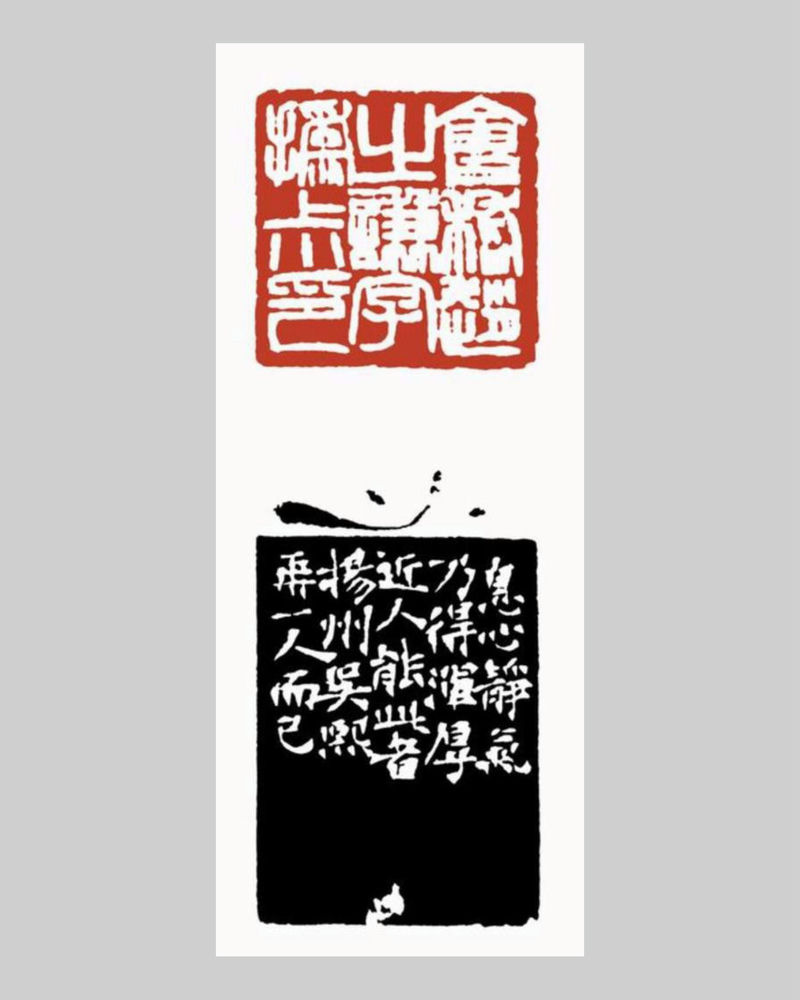

Illustration 2: Personal seal of Wu Jang-chih carved by himself. It reads: “Characters on archaic bronzes and stone tablets collected by Wu Jang-chih from I-cheng” (儀徵吳讓之收藏金石文字). Wu Jang-chih did not inscribe this seal, the inscription is a later addition by Yü Yü-shan (虞虞山). Ink rubbing of the inscription is presented for visual clarity.

In his early years, Wu Jang-chih imitated and copied the seals of Ch’in dynasty (221 BC-207 BC) and Han dynasty (202 BC-220 BC). He also emulated the style of Teng Shih-ju, accomplishing his notion of integrating different calligraphic scripts and brush works into seal engraving. Wu Jang-chih was important in the history of seal engraving as both heritor and pioneer. The eminent seal engraver Wu Ch’ang-shuo (吳昌碩 1844-1927) once observed:

“Throughout his life, Jang-weng (tzu of Wu Jang-chih) was an admirer of Wan-pai (tzu of Teng Shih-ju). He was also steeped in the studies of the seals of Ch’in dynasty and Han dynasty. Therefore his method of carving is smooth and uninhibited, it is not diminutive nor effeminate, the aura is bold and unconstrained, it is rustic but not stagnant. My suggestion is: If you wish to learn from Wan-pai (Teng Shih-ju), it is better to follow the path of Jang-weng (Wu Jang-chih).”

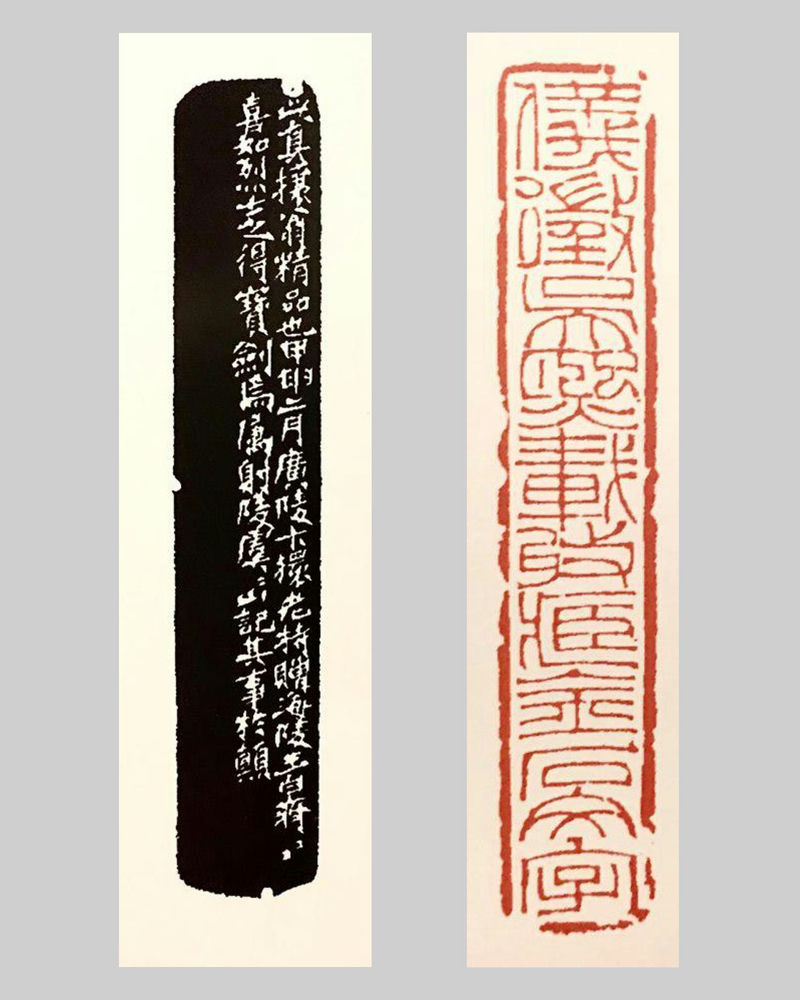

This is indeed a sound elucidation. After Teng Shih-ju pronounced his theory of integrating different calligraphic scripts and brush works into seal engraving, for two generations, both Teng himself and Pao Shih-ch’en cultivated and practiced this theory. However it was Wu Jang-chih who firmly established this trend in the world of seal engraving, with sufficiently large quantity of seal engravings to support this. The most influential seal engraver at the end of the Ch’ing dynasty to the beginning of the Republic was Chao Chih-ch’ien (趙之謙 1829-1884). He was born thirty years after Wu Jang-chih, and he regarded Wu Jang-chih as the preeminent seal engraver in his time. There is a seal carved by Chao Chih-ch’ien with these words: “The seal of Chao Chih-ch’ien, tzu Wei-shu, from Hui-chi (會稽趙之謙字撝尗印).” The side inscription reads: “To ease the heart, to calm the vital energy, this is being simple and vigorous. The only person who can achieve this in recent time, is this one person Wu Jang-chin from Yang-chou (息心靜氣,乃是渾厚。近人能此者,揚州吳讓之一人而已。).” This seal is a clear acclamation. (Illustration 3).

Illustration 3: Seal carved by Chao Chih-ch’ien with these words: “The seal of Chao Chih-ch’ien, tzu Wei-shu, from Hui-chi (會稽趙之謙字撝尗印).” Ink rubbing of the inscription is presented for visual clarity.

In the 3rd year of the T’ung-chih reign (1863), an inquisitive friend of Chao Chih-ch’ien, Wei Chia-sun (魏稼孫?-1881), who was compiling a book about the seals of Chao Chih-ch’ien with the title: A Collection of Seals from Erh-chin-tieh T’ang (二金蜨堂印譜), brought a selection of impressions and ink rubbings of seals from the book, to show Wu Jang-chih for his opinion. Wu commented on the seals of Chao in this manner:

“The correct way to carve a seal is to be simple and forthright, to embellish the characters in the beginning and the end is superfluous. Wan-pai (Teng Shih-ju) was a pioneer who deployed the characters of Han dynasty stone tablets into Han style seals, hence he was a master for posterity. The seals of Mr. Chao have entered the realm of Wan-weng (Teng Shih-ju), how can I add another word of adulation?”

It was a sincere expression through the discerning eyes of a fellow seal engraver.

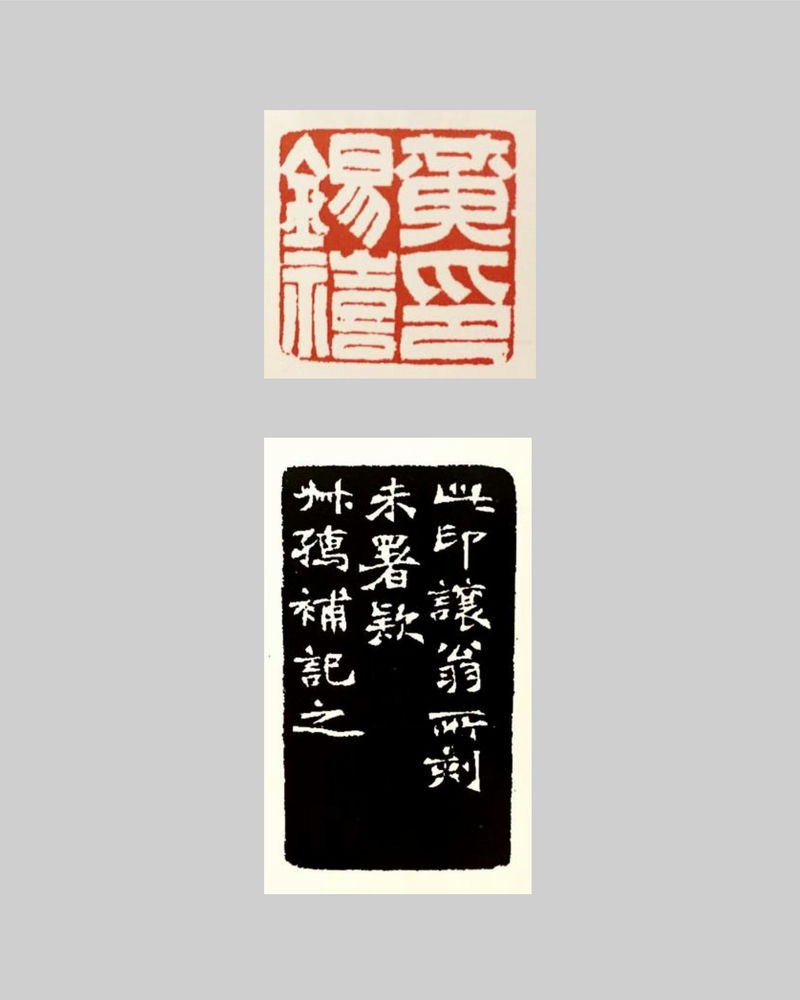

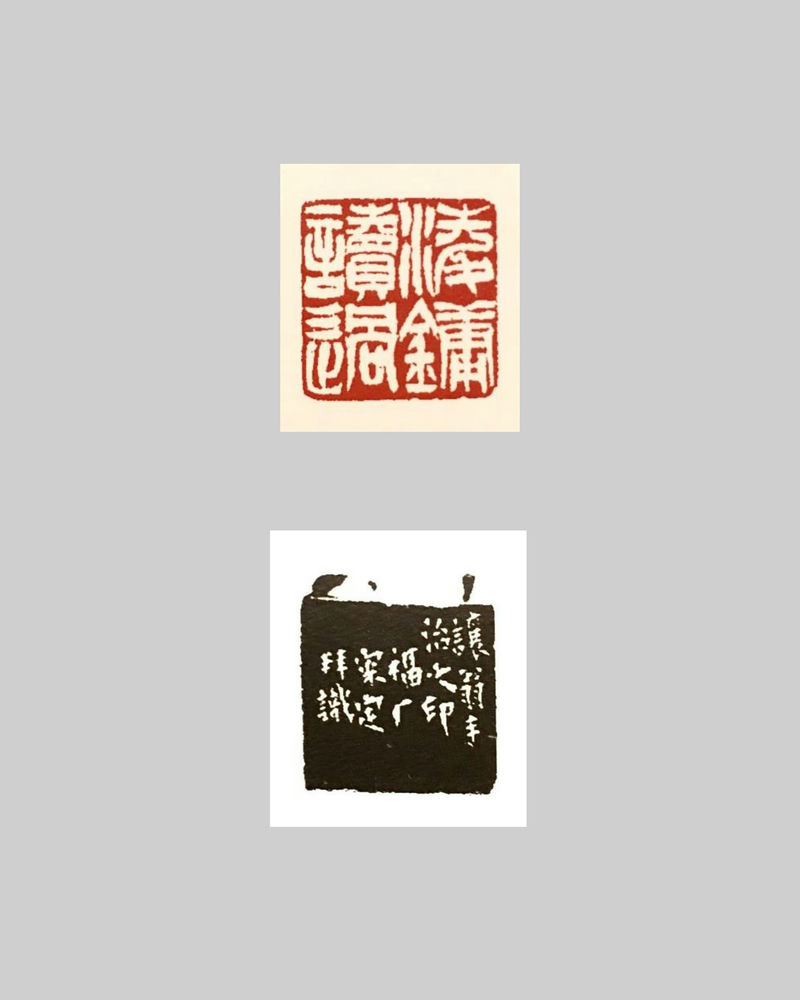

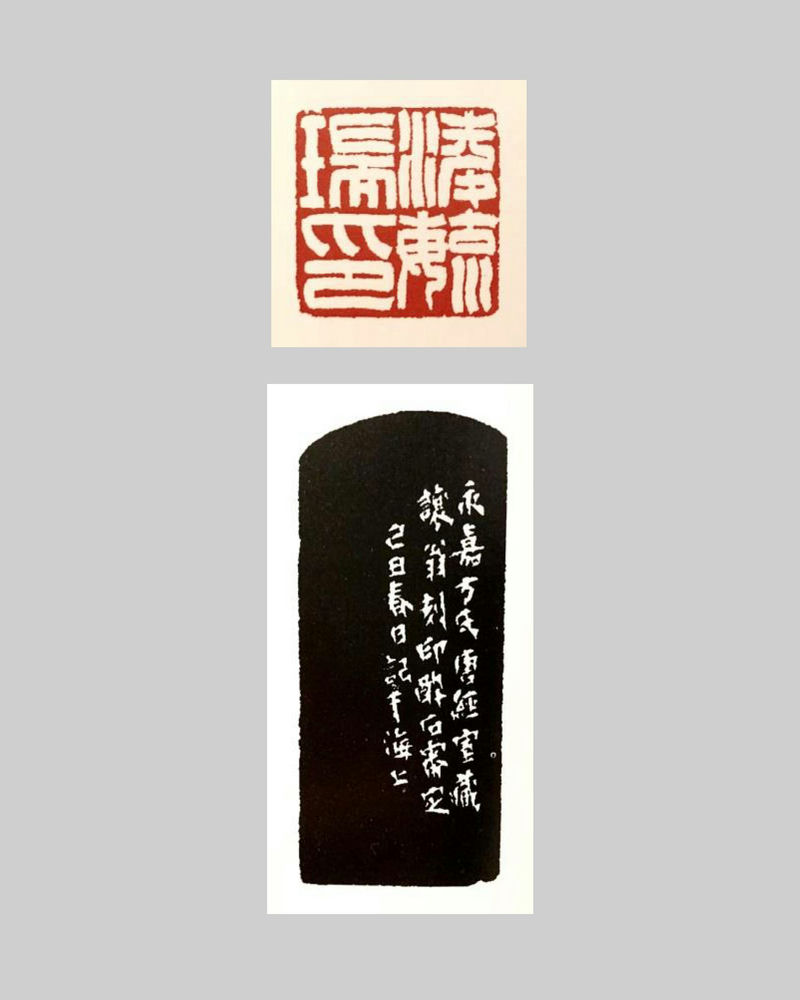

It was chronicled that over ten thousand seals were carved by Wu Jang-chih in his life time. However those seals by Wu documented in books, and those not documented in books but identifiable by inscriptions, amounted approximately to only a thousand. Eighty to ninety percent of these seals have not been inscribed with the name of the artist. This is an unorthodox habit for any seal engraver, and an isolated case from the Ming dynasty to the Ch’ing dynasty. For the seals carved by Wu Jang-chih, the strokes of the characters move and turn lightly like a dance, comparable to sash whirling and soaring. Despite the delicate motion, the strokes are not monotonous nor propitiating, instead they are rustic, guileless and refreshing. It was said that the reason most of Wu’s seals were uninscribed, was due to his belief that his carving and style were not easily copiable, consequently he maintained this habit. We can surmise his teeming self assurance. The distinguished seal engravers of the twentieth century, such as Chao Shu-ju (趙叔孺 1874-1945), Wang Fu-an (王福盦 1880-1960) and T’ang Tsui-shih (唐醉石 1885-1969) had all carved later inscriptions on the seals of Wu Jang-chih for identifications. (Illustration 4, 5, 6).

Illustration 4: Later inscription carved by Chao Shu-ju (趙叔孺) on a seal engraved by Wu Jang-chih. The seal reads: “Seal of Huang Hsi-hsi” (黃錫禧印).

Illustration 5: Later inscription carved by Wang Fu-an (王福盦) on a seal engraved by Wu Jang-chih. The seal reads: “Read by Ling-yung” (淩鏞讀過).

Illustration 6: Later inscription carved by T’ang Tsui-shih (唐醉石) on a seal engraved by Wu Jang-chih. The seal reads: “Seal of Ling Yü-jui (淩毓瑞印).

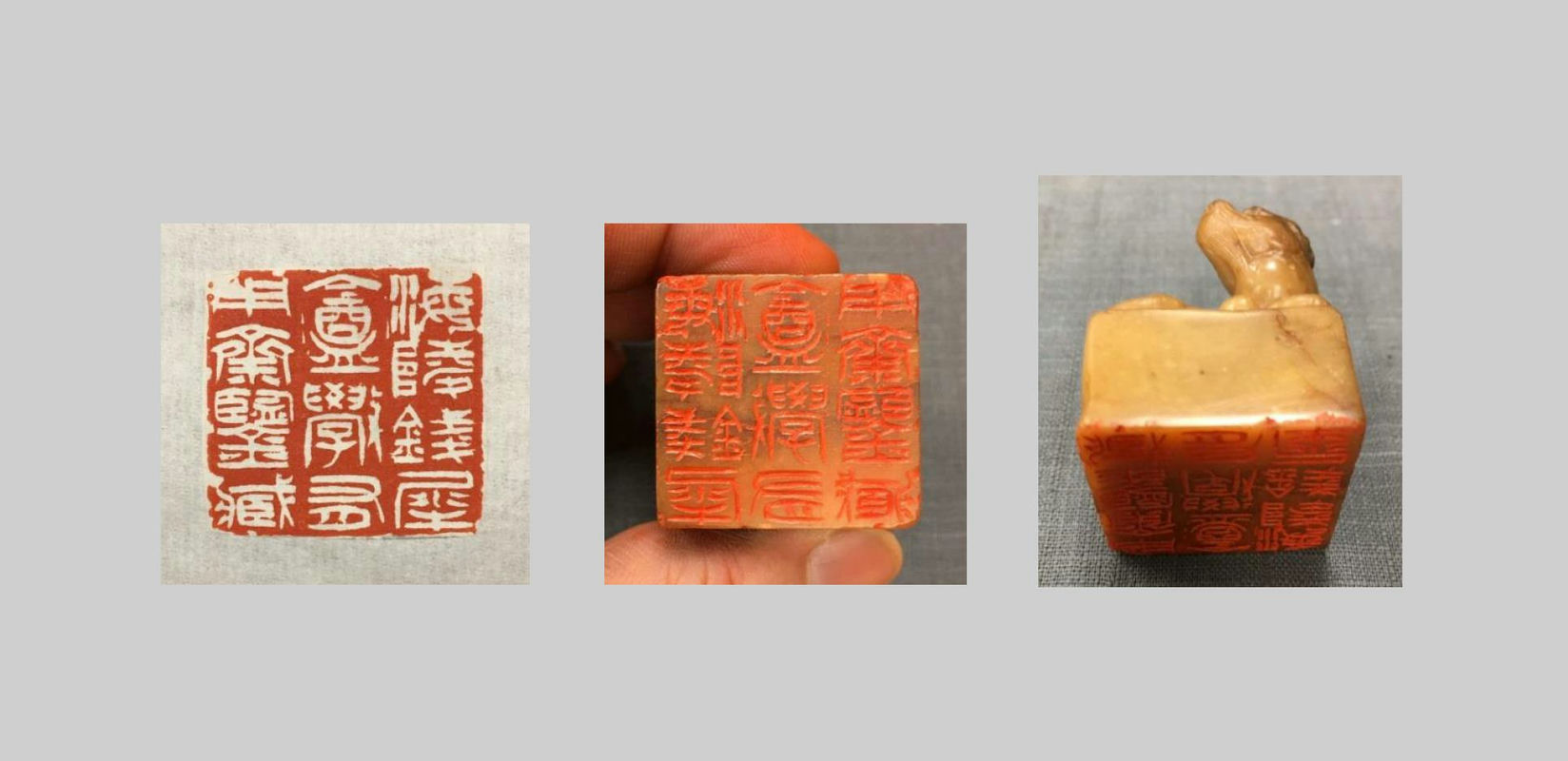

A few years ago, I saw a seal carved with these words: “Inspected and collected by Ch’ien Hsi-an in the Studio of Hsüeh-yu-yung from Hai-ling” (海陵錢犀盦斅有用齋鑒藏). The characters were arranged in three vertical rows and incised to create an intaglio seal impression. The carving is light, skin-deep and effortless, the strokes of the characters are rounded but the quadrilateral shape can still be discerned, a typical technique of Wu Jang-chih. Unfortunately it is not signed. The seal was made from Shou-shan Fu-jung stone, the original colour should be off-white. After years of cosseting, it has turned into pale red. The knob is in the form of an archaic beast, the carving is meticulous, the lines are dense but untangled, it is in the style of mid and late Ch’ing period. This seal can be compared with the seal carved by Wu for Ch’en Pao-chin (陳寶晉), also from Hai-ling, which has these characters : “The seal for the collection of manuscript, archaic bronze, writing, calligraphy and painting of Ch’en Pao-chin, also named K’ang-fu, from Hai-ling (海陵陳寶晉康甫氏鑑藏經籍金石文字書畫之印章).” It is evident both seals are works from the same artist. (Illustration 7, 8)

Illustration 7: Seal engraved by Wu Jang-chih with these characters: “Inspected and collected by Ch’ien Hsi-an in the Studio of Hsüeh-yu-yung from Hai-ling (海陵錢犀盦斅有用齋鑒藏).” (Photographs taken in 2016)

Illustration 8: Seal engraved by Wu Jang-chih with these characters: “The seal for the collection of manuscript, archaic bronze, writing, calligraphy and painting of Ch’en Pao-chin, also named K’ang-fu, from Hai-ling. (海陵陳寶晉康甫氏鑒藏經籍金石文字書畫之印章)”

When I was first shown this seal some years ago by the owner, I inspected it in my hands, and thought it had to be the work of Wu Jang-chih. However after searching the seal books of Wu, I failed to find any trace of its publication, so I left it as an assumption of mine. Later on in 2017, it was assigned to an auction house in Peking for sale. I remembered the starting bid was eight thousand Renminbi, the description was limited to only the characters and dimensions of the seal. This might be because the specialists of the auction house did not think it was important, nor that it could be genuine. As the auction proceeded, many pursued this seal, the bids counted into scores, eventually settling to nearly five hundred and thirty thousand Renminbi inclusive of commission. At that moment I reflected that this seal must be acquired by someone knowledgeable, who was bold enough to offer a price seventy fold to the starting bid. (Illustration 9)

Illustration 9: The page in the auction catalogue illustrating the seal: “Inspected and collected by Ch’ien Hsi-an in the Studio of Hsüeh-yu-yung from Hai-ling. (海陵錢犀盦斅有用齋鑒藏)”

One day in 2019, I browsed a friend’s Wechat account with news of an art collector in P’ing-hu and his seal acquisitions in the last few years. This seal turned out to be among them ! Originally the seal had no inscription on any of the four sides, now it was inscribed on one side by the seal specialist, Mr. Sun Wei-tsu (孫慰祖), from the Shanghai Museum. The characters read: “This is the handiwork of Jang-weng (Wu Jang-chih). His way of engraving, his way of words, are both here. There is no need to argue another word. Connoisseurs will understand this. Wei-tsu. (此攘翁手澤,刀法、字法俱在,固無須更辯一辭也。鑒家知之,慰祖。)” These words are concise, relevant and noteworthy (Illustration 10)

Illustration 10: Seal engraved by Wo Jang-chih with these characters: “Inspected and collected by Ch’ien Hsi-an in the Studio of Hsüeh-yu-yung from Hai-ling. (海陵錢犀盦斅有用齋鑒藏)” Inscription added by Mr. Sun Wei-tsu.

In that instance, there was a gush of relief to know that this seal was finally owned by a connoisseur, and treasured by a connoisseur. It will not encounter the fates like many fine works of seal engraving in history, the engraved characters grinded away by ignorants, or sold for the values of the stones. The reason the art of seal engraving is equated with the arts of calligraphy and painting, and cherished by scholars for generations, is not because of the natural beauty of the stones, nor the finesse of the knobs, far more important are the “engraved characters”, which are the inner expressions and accumulated wisdoms of the seal artists, conveyed through the movements of the engravers’ knives, which can be traced back millenniums away.